Abstract

Introduction

It is 23 years since carbon allotrope known as carbon nanotubes (CNT) was discovered by Iijima, who described them as “rolled graphite sheets inserted into each other”. Since then, CNTs have been studied in nanoelectronic devices. However, CNTs also possess the versatility to act as drug- and gene-delivery vehicles.

Areas covered

This review covers the synthesis, purification and functionalization of CNTs. Arc discharge, laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition are the principle synthesis methods. Non-covalent functionalization relies on attachment of biomolecules by coating the CNT with surfactants, synthetic polymers and biopolymers. Covalent functionalization often involves the initial introduction of carboxylic acids or amine groups, diazonium addition, 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition or reductive alkylation. The aim is to produce functional groups to attach the active cargo.

Expert opinion

In this review, the feasibility of CNT being used as a drug-delivery vehicle is explored. The molecular composition of CNT is extremely hydrophobic and highly aggregation-prone. Therefore, most of the efforts towards drug delivery has centered on chemical functionalization, which is usually divided in two categories; non-covalent and covalent. The biomedical applications of CNT are growing apace, and new drug-delivery technologies play a major role in these efforts.

Keywords: addition reaction, carbon nanotubes, functional group, functionalization, purification, synthesis

1. Introduction

New breakthroughs in nanotechnology have had critical effect on many different industrial fields especially those of the materials science, biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. Different nanocarriers such as liposomes, polymersomes, micelles and carbon-based nanomaterials have been tested for different purposes [1–4]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have attracted much attention since their discovery in 1991 on account of their outstanding structural, electronic and mechanical properties, high surface area, thermal stability and metallic-to-semiconducting current carrying capacity. CNTs can be obtained by various synthetic techniques, and are classified either as single-walled CNTs (SWCNTs), or as multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) depending on the number of concentric rolled graphene layers. Owing to their large surface area, CNTs may be readily conjugated with various biological molecules, such as proteins, enzymes, nucleic acids and drugs. These rolled graphene sheets are held together by van der Waals interactions. These strong interactions direct CNT to bundle together and lead to the formation of large aggregates resembling bunches of asparagus. The limited solubility of CNTs (not only in water but also in most organic solvents), which is the result of these bundles, has severely impacted their use in chemical, biochemical and biomedical applications [5–7].

Two main approaches have currently been proposed for the modification of the CNT surface to achieve the dissolution and the complete exfoliation of the pristine CNTs. One is the covalent attachment of functional groups to the sidewalls or to the defect sites. The other is the non-covalent functionalization of the sidewall. In contrast to the covalent method, the non-covalent approach can attach different functional molecules on the surface of CNTs while maintaining their pristine structure and graphene-type surface. Thus, functionalization of CNTs improves their ability to be processed and modifies their physical and chemical properties [5–7].

2. Carbon nanotubes

The discovery of microtubules and graphitic sheets eventually led to the appreciation of a new allotropic form of carbon that has become a fascinating subject for physicists and chemists in the last two decades. Roger Bacon in 1960 reported concentric helical graphitic microtubes and Iijima in 1991 discovered carbon cylinders consist of graphitic sheets while experimenting with fullerene synthesis [8]. These first needle-like carbon filaments were grown during the arc-discharge evaporation of carbon in argon gas at 100 Torr pressure. Iijima described these filaments, which were grown on the negative end of the graphite electrode, as ‘rolled graphite sheets inserted into each other’. The number of these concentric sheets varied from 2 to 50 [8,9].

In 1992, Ebbesen and Ajayan optimized the conditions for the growth of hollow graphitic tubes to obtain a larger quantity (~ 1 g of graphitic tubes) by the arc-discharge evaporation method [10]. An inert gas atmosphere (flow of Ar or He) of ~ 100 Torr pressure was created in the reaction vessel. Two graphite rods bearing DC current (~ 100 A) with applied potential of ~ 18 V were brought together at ~ 1 mm distance. As a result, a discharge occurred and plasma formed. CNTs along with some carbon nanoparticles were deposited on the larger rod. The reported yield of CNT was 75%. These nanotubes had the same structure as those described by Iijima and consisted of 2–50 concentric graphitic sheets. The minimum diameter of the tubes was 2 nm and maximum was 20 nm [8,9].

2.1 Structure and properties

As mentioned above, CNT can be classified into two main types: SWCNTs, which consist of one single layer of graphene sheet seamlessly rolled into a cylindrical tube, and MWCNTs, which are made up of several concentric graphene layers (Figure 1). The distance between two graphite sheets in MWCNT is typically 0.340 nm, slightly greater than the distance between two consecutive sheets in single crystal graphite, 0.335 nm, which may be explained by specific cylindrical geometry. In single graphite sheets, the carbon atoms are bonded with together by covalent C–C bonds, while for MWCNT structures, due to the weak van der Waals interaction between sheets, the distance between cylindrical layers is increased. They have nanoscale dimensions, with single-walled nanotubes (SWNTs) having diameters in the range of 0.4–3 nm and lengths between 20 and 1000 nm, whereas MWCNT have diameters between 2 and 100 nm and lengths of 1–50 μm. CNTs generally have an aspect ratio (L/D) of around 1:1000 [11].

Figure 1.

Schematic of (A) single-walled carbon nanotube (B) multi-walled carbon nanotube.

The walls of these CNTs are made up of a hexagonal lattice of carbon atoms analogous to the atomic planes of graphite. The ends of their atomic structures are covered with one half of a fullerene-like molecule [12]. In the most general case, a CNT is composed of a concentric arrangement of many cylinders (Figure 1B). Such MWCNTs can reach diameters of up to 100 nm. A special case of these multi-walled tubes is the double-walled CNT composed of just two concentric cylinders. SWCNTs possess the simplest geometry and have been observed with diameters ranging from 0.4 to 3 nm [11,13].

In reality, however, CNT are not ideal or perfect structures, but rather contain defects formed during synthesis. Typically around 1–3% of the carbon atoms of a nanotube are located at a defect site [14]. A frequently encountered type of defect is the so-called Stone–Wales defect, which can be seen in Figure 2. This type of defect is known as a 7-5-5-7 defect because of two pairs of five- and seven-membered rings. A Stone–Wales defect leads to a local deformation of this curvature, addition reactions are most favored at the carbon–carbon double bonds in these defects [15].

Figure 2.

Stone-Wales (or 7-5-5-7) defect on sidewall of nanotube.

The formation of a CNT can be visualized through the rolling of a graphene sheet. Based on the orientation of the tube axis with respect to the hexagonal lattice, the structure of a nanotube can be completely specified through its chiral vector (Figure 3), which is denoted by the chiral indices (n, m). CNTs are classified into two categories based on the geometric structure of carbon in cylinder’s seam. Both of armchair (n = m) or zigzag (m = 0) possess mirror symmetry, nanotubes with m =6 n are chiral [16].

Figure 3.

(A – C) classification of SWCNTs, armchair, zigzag and chiral respectively. Armchair and zigzag refer to the shape of cross sectional ring. (D) Unrolled honeycomb lattice of a SWCNT.

SWCNT: Single-walled carbon nanotube.

According to the zone-folding approach, which derives the electronic structure of nanotubes directly from graphite, a nanotube behaves either as a metal or as a semiconductor, depending on its chiral vector [17].

CNTs have the tendency to aggregate into bundles with large numbers of both metallic and semiconducting SWCNTs in a mixture of one third and two thirds, respectively, because of a high surface energy and excellent flexibility. Bundle properties are generally inferior to those of isolated SWCNTs and effective separation of aggregates must be achieved prior to functionalization and construction of nanodevices.

CNTs possess high tensile strength, are ultra-light weight and have excellent transport conductivity, as well as thermal and chemical stability. The mechanical properties of CNTs are also outstanding. The density-normalized Young’s modulus and ultimate tensile strength of typical SWCNT are 19 and 56 times that of a steel wire and 2.4 and 1.7 times that of silicon carbide nanorods, respectively, in addition to their high elasticity. Nanotubes are chemically inert by nature and the presence of empty space inside them in addition to their high mechanical strength, described earlier and electrical conductivity make them attractive for use in structural applications, nanomedicine and nano-optoelectronics devices [18,19].

2.2 Synthesis and purification techniques

The high prices of CNTs (e.g., around 50–100 Euros/g of SWCNTs) is a main concern for those contemplating large-scale production. In this part, arc-discharge, laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) as main methods for the production of both types of CNTs and the modulation of their dimensions are reviewed.

2.2.1 Arc discharge

As mentioned above S. Iijima [9] used a DC arc discharge in argon consisting of a set of carbon electrodes. The discharge temperature was in the range of 2000–3000°C at nominal conditions of 100 A and 20 V. This apparatus produced multi-walled nanotubes in the soot. Later, SWCNTs were grown with the same set-up by adding to the electrodes suitable catalyst particles, for example, of Fe, Co, Ni or rare-earth metals [20].

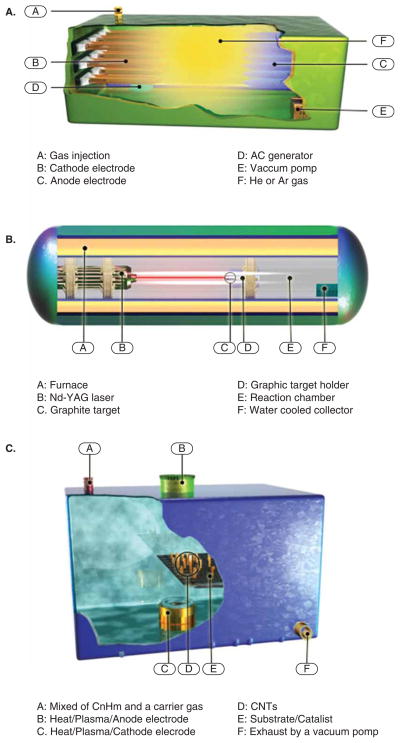

This method is a slightly modied version of the method used for fullerene production. An arc discharge is generated between two graphite electrodes placed face to face in the machine’s principal airtight chamber (Figure 4A) under a partial pressure of helium or argon (typically 600 mbar). The electrical discharge that results brings the temperature up to 6000°C. This is hot enough for the carbon contained in the graphite to sublime–that is, transform from a solid state to gaseous one without turning into a liquid first. During sublimation, the high energies involved can eject single carbon atoms from the solid forming plasma. These atoms move towards colder zones within the chamber, allowing a nanotube deposit to accumulate on the cathode. In fact, in the chamber, the gas ionizes to electrons and positively charged ions and produces a very hot plasma. The electrons impact the anode with high velocity, and the carbon material is raised to such a high temperature that carbon vapor is produced, and then the carbon is ionized to give carbon ions. Next, the carbon ions and vapor migrate to the cathode, which is cooler than the anode electrode, where they form clusters, due to the decreased temperature, by a phase transition to liquid carbon and then to solid carbon where it has been found that CNTs are synthesized [21]. It has been reported that different kind of substances such as large quantities of rubbery soot, web-like structures between the cathode and the chamber walls, grey hard deposits, and a spongy soft coating like a belt called ‘collaret’ can be formed in different parts of reactor besides CNT [22]. The type of nanotube that is formed depends crucially upon the presence of metal catalysts. If small amounts of transition metals such as Fe, Co, Ni or Y are introduced in the target graphite, then SWCNTs are the dominant product [23,24].

Figure 4.

Schematic of (A) arc discharge (B) laser ablation and (C) chemical vapor deposition methods.

There are many physical and chemical parameters such as the dispersion and concentration of the carbon vapor in the inert gas, the temperature inside the reactor, the addition of promoters, the exact composition of the catalyst, and the presence of hydrogen which affect the arc-discharge process. The nucleation and the growth of the nanotubes, their inner and outer diameters and the type of nanotubes (SWCNTs, MWCNTs) are the main characteristics that can be influenced by the above-mentioned variables [25].

Liquid N2, deionized water and aqueous solutions of NiSO4, CoSO4,FeSO4 and NaCl have been added to the reaction environment in the arc-discharge method. The precise composition of the reaction environment has a huge impact on the characteristics of the products [26,27]. For instance, in liquid nitrogen in the range of 22 – 27 V, a high density of MWCNTs with distorted morphology, degraded structure and irregularly shaped multishelled carbon ‘onions’ were obtained [24,28,29]. This method has recently been modified to improve the efficiency and properties of CNTs. The use of an electric field-assisted arc-discharge technique resulted in direct synthesis of de-bundled SWCNTs. In this report, > 50% of SWCTNs obtained were < 3 nm in diameter. Since diameter of individual SWCNT is 1.3 – 2.7 nm, this meant that > 50% of them were isolated or at most bundles of two SWCNTs [24]. Table 1 shows some of the parameters in the arc-discharge method.

Table 1.

Arc-discharge parameters in recent publications.

| Type of CNTs | Diameter (nm) | Arc Current (A) | Synthesis time (min) | Catalyst type | Environment | Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWCNTs | > 10 | 120 | – | Fe, Co, Ni, FeS | Hydrogen, 240 Torr | 2014 | [24] |

| MWCNTs | 10 –20 | 90 | – | – | Methane, 100, 300 and 500 Torr | 2014 | [131] |

| SWCNTs | 1.3 – 1.6 | 90 | – | Ni-Y | Helium, 375 Torr | 2014 | [132] |

| DWCNTs | – | 80 | 20 | Air, 50 Torr | 2013 | [133] | |

| CNTs | – | 75 – 95 | 5 | Ni – Y2O3 | Hydrogen –argon, 150 Torr | 2013 | [134] |

| SWCNTs | 10 – 30 | 80 | 10 | Fe – W | Hydrogen –argon, 200 Torr | 2013 | [135] |

| Few-walled CNTs | 1.6 –6 | 90 | – | Fe – S | Air, 0.75 –135 Torr | 2013 | [136] |

| MWCNTs | – | 75 | – | – | Deionised water | 2013 | [137] |

| MWCNTs | 50 – 100 | 50 | 5 – 10 | – | Argon, 525 Torr | 2013 | [26] |

| CNTs | – | 105 | 5 – 8 | – | – | 2012 | [138] |

| MWCNTs | 10.4 | 100 | – | – | Argon | 2012 | [139] |

| MWCNTs | 15 | 80 | – | – | Air, 60 Torr | 2012 | [139,140] |

| SWCNTs | – | 120 | – | Ni-Y2O3 | Hydrogen –helium, 530 Torr | 2012 | [141] |

| SWCNTs | – | 90 | – | Ni-Y | Helium, 375 Torr | 2012 | [142] |

| MWCNTs | – | 80, 100, 150 | 8 | – | Helium, 760 Torr | 2012 | [143] |

| Few-walled CNTs | 1 – 10 | 150 | – | Fe-Rh | Hydrogen –argon, 200 Torr | 2012 | [144] |

| MWCNTs | – | 80 | 20 | – | Air, 40 – 300 Torr | 2012 | [145] |

| CNTs | 40 – 60 | 210 | 4 | – | Hydrogen, 50 Torr | 2012 | [146] |

| CNTs | – | 2.5 | – | – | Air | 2012 | [147] |

| MWCNTs | – | 10 | 15 | – | Argon, 525 Torr | 2012 | [148] |

| CNTs | 5 | 20 | 60 | Metal catalysts | De-ionized water | 2012 | [149] |

CNT: Carbon nanotube; MWCNT: Multi-walled carbon nanotube; SWCNT: Single-walled carbon nanotube.

2.2.2 Laser ablation

The secondearly method of SWCNT synthesis was laser ablation – laser vaporization of a graphite rod in an oven with Co and Ni as catalysts [30]. This mechanism of the CNT production is similar to the arc-discharge method. As shown in Figure 4, in this method, a carbon-metal composition is placed in a heated chamber with a flow of argon at 500 Torr with a flow rate of 50 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute). The laser beam is focused on the target, and the soot produced by the laser was deposited onto a cooled copper collector (Figure 4B) [31].

SWCNTs with about 90% purity and with a better-graphitized structure than those produced in the arc process can be achieved by the laser ablation method. Laser ablation can produce a low amount of CNTs but with high purity, and vice versa, the arc-discharge method can produce a large amount of CNTs but with significant impurities. Parameters such as: gas flow rate, carrier gas type, catalyst, substrate for nucleation and time are the most important parameters that affect the CNTs structure and growth [32]. One of the crucial factors in CNT synthesis is the composition of the target material, and in fact using pure graphite targets in laser ablation yields fullerenes and nano-onions rather than nanotubes [8,33,34]. Isolated SWCNTs have been reported when a graphite target containing monometallic Co or Ni dopants has been used. On the other hand, it is found that applying bimetallic graphite containing a Ni/Y catalyst (with the concentration of Ni always higher than that of Y, or Ni/Co in equal concentration) resulted in a high yield of SWCNT bundles [35]. Additionally, the CNT yield and quality depended on the reaction temperature with the best result at 1200°C. The quality of the CNTs diminished and lots of defects appeared at lower temperatures [31,32].

Although laser ablation and arc discharge yield nanotubes with high quality, these techniques suffer from the following shortcomings:

Obtaining large quantities of graphite is problematic, which limits large-scale production.

The purification process of the tangled form of nanotubes mixed with unwanted materials is problematic and expensive.

Energy consumption can be very high in these methods.

In comparison with other methods, these two methods have a higher reaction temperature, which causes difficulties in designing an industrial process [32,36].

2.2.3 Chemical vapor deposition

The third popular synthesis method is the catalytic growth of carbon tubules by decomposition of hydrocarbons, which was introduced in 1992 [35]. By this method, later named as catalytic CVD, MWCNTs and SWCNTs were produced. As a carbon source one can use acetylene, propylene, ethylene or methane [36,37]. Decomposition temperature was between 650 and 900°C. The diameter of the multi-walled nanotubes depends on the diameter of catalyst particles, and the length on the reaction time. The yield of nanotubes was generally higher than that observed in the arc-discharge method [38]. More CVD methods are presented in the following.

2.2.3.1 Hot filament

The hot filament CVD (HFCVD) is an economical technique for the synthesis of CNTs and other carbon nanostructures such as carbon nanoflakes [39] and carbon nanowalls [40]. In HFCVD, a relatively inexpensive substrate can be used to produce CNT. Bouanis et al. [41] fabricated SWCNTs by the HFCVD method. They used Ru nanoparticle as a catalyst and methane gas as a carbon source heated by a 2 W filament. A substrate consisting of clay minerals containing kaolinite, sepiolite and nontronite was used to prepare MWCNTs by Pastorková et al. [42] CH4 was the carbon source and H2 was the carrier gas fed at a pressure ~ 3 KPa into the reactor, containing the clay mineral substrate coated with iron to act as a catalyst and heated to 600°C. They concluded three-dimensional grids, nonaligned CNT and aligned MWCNTs were formed by kaolinite, nontronite and sepiolite substrates, respectively. Sanchez-Valencia et al. [43] synthesized chiral CNTs using a bottom-up technique using cyclodehydrogenation on a platinum catalyst. C96H54 was the precursor that was decomposed at 497°C under vacuum condition in order to produce (6,6) ‘armchair’ nanotube seeds. Finally, by epitaxial elongation chiral CNTs grew free of defects. In 2009, Swierczewska et al. [44] first used gadolinium and europium as inner transition metal catalysts to grow SWCNTs by the CVD method, yielding nanotubes with 1.9 nm diameter and a narrow distribution of lengths.

2.2.3.2 Plasma enhanced CVD

Plasma enhanced CVD (PECVD) is another promising method to fabricate vertically aligned CNT (VACNTs) [45]. In this method, a gas containing a carbon source mixed with a carrier gas was injected into a vacuum chamber containing a heated substrate, which was coated with catalyst. The main role of plasma is the dissociation of hydrocarbon molecules in order to produce C atoms and reactive radicals such as CH, CH2, CH3 and H+ ions at a lower temperature compared to arc discharge or laser ablation. VACNTs were produced from acetylene gas with a silicon substrate and nickel catalyst as reported by Saghafi et al. [46]. The vacuum chamber was maintained 10−2 Torr, 65°C and 1.5 – 2 W/cm2DC power to heat the plasma in order to fabricate the VACNTs that had 78 nm diameter and 1 – 8 μm length.

The variation in plasma power, pressure at which the precursors are injected, temperature of the substrate, and the chamber growth time, catalyst content and catalyst thickness are the most important parameters in the PECVD technique as has been comprehensively investigated by Loffler et al. [47] and Jeong et al. [48]. Some researchers have applied plasma-enhanced HFCVD (PEHFCVD) as a complementary technique [49]. Wang et al. [50] fabricated CNTs from an amorphous carbon film without a metallic catalyst on a Si substrate using PEHFCVD. They generated CNTs with about 5 nm diameter and 300 – 800 nm length.

2.2.3.3 Radio frequency plasma-enhanced CVD

Radio frequency plasma-enhanced CVD (RF-PECVD) can produce a higher concentration of reactive radicals from the carbon source at a lower temperature in comparison to PECVD [51]. Wang et al. [51] synthesized MWCNTs with a Ni catalyst on Si, TiN/Si and a glass substrate by a RF-PECVD with RF power 600 W and 13.56 MHz at relatively low temperatures (140°C and 180°C) and injected CH4, H2 and Ar into the chamber. They evaluated parameters such as substrate temperature and type, plasma intensity, gas flow rate and gas compositions. Dervishi et al. [52] devised an inexpensive method for the preparation of CNTs using a radio frequency generator and an electrical furnace in a hydrogen/ argon atmosphere. They used an iron oxide-graphene substrate without using any hydrocarbon gas at a relatively low temperature between 150 and 500°C. They reported that if they used iron oxide nanoparticles with a diameter of 5 nm then CNT were formed at 150°C, whereas if 15 nm nanoparticles were used, the temperature needed to be 400°C or higher.

2.2.3.4 Microwave plasma-enhanced CVD

The microwave plasma-enhanced CVD (MPECVD) method is often used for the synthesis of CNTs at low temperature and high yield. For example, flat panel displays were fabricated by growing CNT on the surface of a soda-lime glass substrate using acetylene at 550°C without deformation [53]. Park et al. [54] fabricated MWCNTs by the MPECVD method from methane and hydrogen gases at a pressure of 2.13 KPa and microwave generator power of 800 W. Corning 1737 glass containing precipitated TiN and Ni was the substrate with a bias voltage about – 200 V. They could isolate MWCNTs with 20 nm diameter and 5 μm length at temperatures below 500°C and reported that increasing substrate temperature, improved the crystallinity of the MWCNTs. Another study [55] with the same conditions, focused on changes of the DC bias voltage between −250 and −50 V and its effect on the length, structure, crystallinity and electrical properties of the MWCNTs.

2.2.3.5 Water-assisted CVD

In 2004, water-assisted CVD (WA-CVD) was presented by Hata et al. [56]. By adding an amount of water into the CVD reactor, the catalyst activity, rate of formation and length increased, and the CNT diameter changed [57]. WA-CVD was called ‘super-growth CVD’ due to the improved CNTs synthesis [58,59]. Ren et al. [60] synthesized SWCNTs by using Co-MCM-41 as a catalyst in water/ethanol-assisted CVD. They found that by increasing the H2O/C2H5OH ratio, the SWCNTs’ diameter increased. A study that examined the effect of water in the CVD process was published by Cui et al. [61].

2.2.3.6 Oxygen-/carbon dioxide-assisted CVD

Oxygen or carbon dioxide can also enhance CVD technique for CNTs synthesis. Kim et al. [62] reported that oxygen-assisted MPECVD using a mixture of CH4/H2 gases with a Fe/Al2O3/Si substrate and a temperature of 700°C could give MWCNTs with 4.08 μm length and 5 – 10 nm diameter. They found that upon adding O2 to the chamber, the CNTs growth rate increased three-fold in comparison with MECVD and two-fold in comparison with WA-MECVD. Recently, Qi et al. [63] investigated the effect of oxygen on the length and purity of CNTs using the PECVD technique with a Co catalyst on a Si substrate and a methane/hydrogen mixture at a flow rate of 0 – 6 sccm. They showed that by increasing the O2 flow rate, the nanoparticle adhesion on the CNTs surface decreased, and with a 3 sccm flow rate the CNTs length increased to 7 μm and at a 6 sccm flow rate the CNTs growth decreased. They concluded that by adding O2 to system, OH radicals were formed.

Wen et al. [64] showed by using 0.1 – 1.5% CO2 in the feed gas (methane) on a Fe/Mo/MgO catalyst, the amorphous carbon could be removed, the holes in the MgO support decreased, its specific surface area increased and the CNTs purity was improved. Techniques such as alcohol-assisted CVD [65], camphor-assisted CVD [66], thermal pyrolysis and flame synthesis [67] and low-pressure CVD [68] are some other methods, which have been used by researchers in order to improve CNTs synthesis. A schematic diagram of the reactor is shown in Figure 4C.

2.2.3.7 CVD with organometallic precursors

An interesting idea was to combine a carbon source and the catalyst in a single compound by using organometallic precursors like ferrocene or nickelocene for CNT synthesis [69]. The pyrolysis of these compounds was carried out using a mixture of methane or acetylene at 1100°C and produced SWCNTs or MWCNTs depending on the process conditions [69]. A few rather unusual sources of carbon for CNT synthesis have also been tried with some success. For example, a ferrocene/benzene mixture enriched with thiophene as a growth promoter was injected into a hydrogen flow. If about 0.5 – 5 wt% of thiophene was added into the stream, SWCNT could be produced. If the thiophene was increased to > 5% then MWCNT could be formed [70]. The use of a ferrocenexylene mixture can also produce MWCNT. The reported yield was ~ 25% of the total carbon stock [71,72].

3. Preparing CNTs for drug delivery

CNTs are materials that are practically insoluble and hardly able to be dispersed, in any kind of solvent. To integrate the nanotube technology into the biological environment, the solubility of the nanotubes, especially in aqueous solutions must be drastically improved. Functionalization is a technique used to overcome this issue. The most popular route to administer CNTs is intravenous (i.v.) injection. However, when given by i.v. route, the, CNTs are found to accumulate in the reticuloendothelial system especially in the liver and lungs. CNTs are also exerted in urine; therefore, the i.v. route is suitable for delivery of the drug to the kidney and urethra. Moreover, subcutaneous administration of CNTs has been proposed by researchers, but due to possible stimulation of dendritic cells in the skin it may lead to immune response [73–75].

Generally, the functionalization process involves the attachment of materials to the sides or end of the CNTs, hence improving their biocompatibility. Functionalized CNTs have been intensively studied in the last few years. The attachment may be achieved via covalent or non-covalent bonding. There are advantages and disadvantages related to the two strategies of functionalization, which will be tackled in the following paragraphs [76,77].

3.1 Non-covalent

Attaching different molecules to the basic structure of CNTs via physical interaction is the fundamental mechanism of non-covalent functionalization. Adsorption mediated by different forces, such as van der Waals force, electrostatic force, π-stacking interactions and hydrogen bonds are the basic foundation of non-covalent functionalization which is mainly based on formation of supramolecular complexes [78]. Owing to the drawbacks of covalent modification such as distortion of pristine CNT, the difficulty and expense, and drawbacks of γ-conjugation, many studies have emphasized the advantages of easy, nondestructive, cheap and ‘one-step’ non-covalent methods for surface functionalization of CNTs. The dispersion procedures usually involve ultrasonication, centrifugation and filtration and are quick and easy to perform. Hydrophobic or π–π interactions are often evoked as likely being responsible for non-covalent stabilization. Three main classes of important molecules that can be used for dispersion of CNTs are classified as, surfactants, polymers and biopolymers (nucleic acids and peptides). These materials have been selected because of their low cost and easy availability [79].

3.1.1 Surfactants

A variety of anionic, cationic and nonionic surfactants have been applied to disperse nanotubes. In order to obtain CNTs suspensions up to 0.1 and 0.5 mg/ml, SDS and Triton X-100 were used, respectively [80]. However, the stability of this suspension was no longer than 1 week. Using sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate resulted in over 1 month stable 10 mg/ml concentration of the suspension. Studying of SDS/CNTs dispersions via atomic force microscopy and electronic transmission microscopy (TEM) revealed that CNTs are mainly present as individual tubes uniformly covered by the surfactant [81]. Triton-X mainly interacts by π-stacking. Another approach for the adsorption/dispersion of CNTs via π-interaction achieved by use of 1-pyrenebutanoic acid activated as succinimidyl ester, which promptly reacts with the amino groups present in the proteins like ferritin or streptavidin [82]. The solubility of CNTs was in the range of 0.1 and 0.7 mg/ml, which is rather low but acceptable for biological use. Surfactants are efficient in the solubilization of CNTs. However, they are known to permeabilize plasma membranes and have a toxicity profile of their own.

Recent developments in surfactant synthesis have extended the variety of biocompatible surfactants available. The surfactants known as Pluronics, are a group of nonionic triblock copolymers. Among the various types of Pluronicavailable, PF127 and PF108 have shown excellent CNT dispersion properties because of their amphiphilic nature and steric hindrance effect [83]. The ability of these surfactants to entirely disperse CNTs depends on length of the polymer chain [84]. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was compared to PF108 as dispersants for MWCNTs in terms of tube stability as well as profibrogenic effects in vitro and in vivo. While BSA-dispersed tubes were a potent inducer of pulmonary fibrosis, the PF108 coating protected the CNT from damaging the lysosomal membrane and causing pulmonary fibrosis [85]. The surfactant 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000) was used as a bridge to join CNTs to peptides like NGR (Asn-Gly-Arg) in order to enhance tumor targeting efficacy of the system [86]. DSPE-PEG2000 increased the blood circulation time of the system [87]. Investigation of the zeta potential of CNT conjugated to DSPE-mPEG showed that the best ratio of CNT:mPEG was 1:8 [88].

3.1.2 Biomolecules

Because of large surface area of CNTs, they can easily interact with different biomolecules including biopolymers via van der Waals interactions, with nucleic acids although π–π stacking interactions, and with proteins by hydrophobic interaction [89].

3.1.2.1 DNA

Owing to properties such as simple chemical structure, ease of synthesis, variable size with small pieces possible, reversible denaturation, a high sequence specificity, and its flexibility, nucleic acids (and DNA in particular) are excellent building blocks to construct macromolecular networks. Functionalization of CNTs with DNA molecules can be used in applications such as nanodevices or nanosystems, electronic sequencing and gene transporters [90]. The π–π interactions typical of double-stranded DNA are used for CNT dispersion [91]. In order to form supramolecular complexes based on π-stacking between the aromatic bases and the CNTs surface, nucleic acids are ideal candidates [73]. The interaction between DNA and CNT is between anionic groups of DNA, with cationic groups on CNTs, resulting in superior biostability. The combination of CNT with DNA can enhance the expression of modified DNA and provide a mechanism for cellular uptake.

Enyashin et al. [92] reported systematic quantum mechanical modeling of the stability and the electronic properties of complexes based on SWCNT, which were helically wrapped by DNA molecules. They studied the effect of the CNT diameter and the kind of nucleotides in the homopolymeric DNAs. CNT wrapped by homopolymeric single-stranded DNA molecules showed a density-functional tight-binding conformation. A phenomenological model of the CNT-DNA formation energy as a function of the nanotube radii led to the decoration of a CNT by only a few DNA chains, but which resulted in a high water solubility of CNT-DNA. In order to wrap the CNTs, pyrimidine-based DNAs were more effective. In a few specific cases, charge transfer from the DNA to the CNT occurred and an additional gain in the CNT-DNA formation energy was observed. Das et al. [93] constructed SWNT-based chemiresistoraptasensors for highly sensitive and selective detection of weakly or uncharged molecules using the displacement format. ATP, a small weakly charged molecule, was detected by displacement of the ssDNA anti-ATP aptamer hybridized to a small capture oligonucleotide covalently attached on SWNTs, with picomolar sensitivity and selectivity over GTP. Taghdisi et al. used π–π interaction for functionalization of CNTs with the sgc8captamer that targets leukemia biomarker, protein tyrosine kinase-7 to form a complex between daunorubicin and SWNT to enhance targeted delivery of Dau to acute lymphoblastic leukemia T-cells (Molt-4) [73].

3.1.2.2 Carbohydrates

In 2002, Stoddart et al. [94] first reported the preparation of a ‘starched SWCNT’. Preformed amylose/iodine complexes could disperse CNT, but the aqueous solution of amylose alone could not dissolve SWCNTs. According to these observations, they suggested a ‘pea-shooting’ mechanism where the CNTs can enter the helical amylose/iodine complex by sequentially displacing the iodine inside the complex. They also proposed that pure SWCNTs could be precipitated and obtained after adding amyloglucosidase into the aqueous solution of the starch-wrapped SWNTs. Thus, starch complexes could be a practical method to purify SWCNTs. Kim’s group [95], studied the interaction between amylose and SWCNTs in aqueous Dimethyl sulfoxide solution in the absence of iodine. In this reaction medium, amylose is only loosely coiled, compared to the case when iodine is present. Results showed that weakly twisted A/S-C structures with a diameter of about 30 nm were formed by amylose acting as a host-guest molecule allowing occupation by a guest CNT with a diameter of > 1 nm.

A theoretical basis for the preparation of carbohydrate/ CNT complexes has been proposed. Soh et al. [96] studied the mode of interaction between the initially separated amylose and SWCNT fragments by molecular dynamics simulations. It was found that the van der Waals force was dominant, which promotes non-covalent association. As a result, amylose molecules could be used to bind with nanotubes, and the size of nanotubes affected the non-covalent functionalization of CNTs.

Single-chain schizophyllan and curdlan (s-SPG and s-curdlan, respectively) were also used by Numata et al. [97] to dissolve SWCNTs in aqueous solution. Interestingly, s-SPG or s-curdlan could wrap around SWCNTs resulting in a twined helical structure. It was observed from the high-resolution TEM images that the two s-SPG chains twined around one SWCNT and the helical motif was right-handed.

The hydroxyl groups present on polysaccharides make it possible to further functionalize CNTs by attaching yet more groups. Moreover, because of the recurring periodic structure of linked carbohydrate monomers on the composite surface, it can be inferred that one could design carbohydrate-CNTs using the concept of supramolecular or self-assembly chemistry.

Gum Arabic and cyclodextrins have also been used to functionalize CNTs [98–100]. There are three main types of cyclodextrins; however, only β-cyclodextrin has an inner cavity diameter of 0.75 – 0.83 nm and therefore has the ability to accommodate a guest molecule as large as a nanotube, into its inner cavity and form an inclusion complex [101].

3.1.3 Polymers

It has been shown than the structure, chemical properties and electrical charge of polymers can influence the dispersion and properties of CNTs. Properties such as facile electrochemical polymerization, ion exchange with the medium, good capacity to enhance adhesive coatings, make polypyrrole (PPy) a good candidate polymer to be used for improving the electronic conductivity of CNTs [102]. Polyvinylpyrrolidone is anamphiphilic stable polymer that is nontoxic and biocompatible and has been used for modification of SWCNTs under physiological conditions in aqueous media [103].

Kayatin et al. discovered during a study of polymer functionalization of CNTs, that having excess styrene in the reaction compared to Li/NH3 led to facile polymerization and conjugation to the side walls of SWCNTs. They applied polystyrene (PS) to stabilize CNTs and found that small PS bound to SWNT outer walls to increase its dispersibility. They then used reductive alkylation of SWNT with dodecyl surface groups to calculate the PS MW [104]. In another study, Soylak et al. used PPy to increase the solubility and time-life of the MWCNTs [105]. Separately, Karadas et al. found that oxidation of PPy could produce a negative charge density on the surface of MWCNTs, and increase the porosity and drug loading efficiency via an ion exchange process [102]. Wu et al. synthesized a pentablock-polymer-SWCNT conjugate to increase thermoresponsiveness, stability and dispersibility of the CNTs. This design stabilized the drug-CNT hybrid without any sedimentation over 2 months of storage as well as reversible switching between the aggregated state and exfoliation according to the temperature cycling [106].

Moradian et al. investigated polyethyleneimine (PEI) polymer to functionalize CNT. The presence of PEI on the surface of CNTs increased the hydrophobic chain size from 70.89 to 110.1 nm and the surface potential of acid treated MWCNTs was raised from 40.7 to 39.3. PEI could enhance the binding efficiency of pDNA and DNA condensation, and produce a homogeneous dispersion in aqueous solution [107]. In a separate study, PEI was conjugated with DSPE-PEG then bound to the CNTs to reduce the toxicity and increase the efficiency of siRNA loading [74]. Bagheri et al. applied polyphenylamine to disperse CNTs [108]. Polyaminothiophenal also was used as a conductive polymer to functionalize the CNTs to increase thermal stability, porosity and nanotube diameter [109]. Yan et al. decorated CNTs with poly(3-hexylthiophene) by addition of phenylbutyrate-methyl ester to obtain polyethylenedioxythiophenpolystyrenesulfonate-SWNCTs [110]. MWCNT-polyvinyl alcohol was found to have good adsorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in aqueous solutions [111].

3.1.4 Peptides

Proteins and polypeptides are often used to functionalize CNTs. Protein is an outstanding natural nanomaterial for construction of molecular machines. Amphiphilic peptides are an efficient dispersion agent for CNTs. The presence of amino acids (e.g., tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan) is mainly responsible for this interaction. These peptides could either be selected from phage-display peptide libraries or synthesized by design. The sequence of highly specific peptides able to wrap around the CNT make it possible to assure solubility and may even provide a useful tool for size separation [112].

Poly-L-lysine (PLL) is one of the natural peptides that have been used for modification of CNTs. Properties such as multiple amino groups, good water solubility and flexible backbone make it a suitable candidate for this purpose. After cross-linking of the amino group of the PLL with CNT, the modified CNT is able to better bind biological compounds and drugs [113]. Ling et al. used N-carboxyanhydride polymerization to synthesized PLL-modified MWCNTs. The non-covalent MWCNTs-PLL composite increased the dispersion of CNT compared to MWCNTs-SDS and provided a pH-responsive element [114]. Hashida et al. designed seven different peptides to form a β-sheet structure to wrap the SWCNTs to enhance dispersibility and stability. Among the peptides H-(Lys-Phe-Lys-Ala)7-OH showed satisfactory properties of stability and could be applied in photothermal cancer therapy [115].

RGD is a tripeptide (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid) that binds to αvβ3 integrins that are overexpressed on cancer cells. RGD peptide was conjugated to SWCNTs bound to phospholipid and PEG and was specfically targeted to its receptor on cancer cells. The NGR peptide has the ability to bind to CD13 which is also over-expressed on cancer cells. NGR was conjugated to SWCNTs and bound docetaxel to target tumor cells. The NGR-SWCNTs were also bound to 2-methoxyestradiol for neovascular targeting of the drug [89].

Iancu et al. [116] proposed a method for non-covalent functionalization of MWCNTs with human serum albumin (HSA) protein for targeting laser-induced necrosis to liver cancer cells. Briefly, oxidized MWCNTs and human serum albumin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (HSA-FITC) were mixed in water at concentrations of 0.25 and 1.25 mg/ml, respectively. Then, the mixture was sonicated for 1 h with a tip sonicator in an ice bath and centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 r.p.m The HSA-MWCNT conjugate was purified using gel chromatography.

3.2 Covalent functionalization

Covalent functionalization is based on the covalent linkage of functional moieties onto the CNT carbon scaffold. The covalent bonding of a functional group to the SWCNTs will produce stable functioned SWCNTs making the material suitable for a variety of applications such as drug delivery. However, using covalent functionalization, the electronic properties of SWCNTs are disturbed, and double bonds are irreversibly lost. There are two categories of covalent functionalization, direct covalent functionalization and indirect covalent functionalization with carboxylic groups on the surface of CNTs [75].

A common type covalent functionalization is achieved through addition reactions to CNTs. The chemistry of fullerenes plays the main role in this method. Association of changes in hybridization from sp2 to sp3 with a loss of conjugation after direct covalent functionalization have been widely studied [117]. Favvas et al. conjugated a phenol group on the outer surface of MWCNTs and found excellent dispersion behavior of phenol-functioned MWCNTs in N-Methylpyrrolidone solvent [118].

Carboxylation of SWCNTs is another common method for the covalent functionalization of SWCNTs since the preparation is relatively simple and quick. The oxidation process does not require complex apparatus and can be achieved in a short period of time. Madani et al. [5] investigated the treatment of SWCNTs with a combination of acids. The system, which was used to coat the surface of the SWCNT, resulted in the attachment of carboxylic acid groups (COOH), producing dispersible, hydrophilic SWCNTs. They also pointed out that the ability of COOH groups to bind to other functional groups such as amines or thiols is another benefit of carboxylation. Finally, they suggested that treating pure SWCNTs with HNO3/H2SO4 (1:3) at 120°C for 120 min was an effective method. Mubarak et al. used acid oxidative methods; first they mixed MWCNT with a concentrated mixture of HNO3 and H2SO4 (ratio of 1:3 (v/v) heated at 40°C for 4.5 h, followed by filtration via hydrophilized PTFE membrane and alcohol treatment [119]. Functionalization of CNTs was found to occur during the purification process in nitric acid solution and in the presence of HNO3 and H2SO4 [120]. Sahoo et al. used PNA for functionalization of MWCNTs after oxidation with HNO3 and H2SO4 (ratio of 3:1). Then carbodiimide-activated esterification reaction is applied for conjugation of PVA to the COOH [121].

Amines can be added in a relatively simple procedure compared to other functional groups attached to CNTs. The nitrogen atom of the amino group (–NH2) has a lone pair of electron, which makes it bond to other molecules easily. The amine-functionalized CNTs are frequently used in fabrication of electrodes [122] due to the mentioned reactivity. Among amine molecules, diamines can function as a cross-linker to attach other compounds to CNTs [123]. Some conventional methods such as sonication and mixing have already employed to introduce adiamine functionality. However, these methods are often time-consuming, involving multiple steps [124].

Rahimpour et al. [125] prepared amine-functioned MWCNTs attached to polyethersulfone (PES) membranes using phase inversion induced by immersion precipitation. Crude MWCNTs were chemically treated using strong acids (H2SO4/HNO3) and 1,3-phenylenediamine (mPDA) to produce the functional amine groups on their surfaces (Table 2). In this study, they fabricated novel NH2-functionalized MWCNTs and blended them with PES casting solution in order to improve the surface properties and performance of ultrafiltration membranes. Maghrebi et al. [126] attached three different diamines (Ethylenediamine, Hexamethylenediamine and 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine) to the surface of MWCNTs in a microwave-assisted method. The procedure was fast, one-pot, simple and resulted in a high degree of functionalization as well as solubility in ethanol.

Table 2.

Examples of CNT functionalization.

| Investigation | Method | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment of SWCNT with a combination of acids | Coating the surface of SWCNTs with HNO3/H2SO4 (1:3) at 1203C for 120 min | Produces dispersible, hydrophilic SWCNTs | [5] |

| Attaching carbonyl (C=O) groups on the SWCNT surface | Oxidation reaction of HiPCO SWCNTs at a 3:1 H2SO4/HNO3 | Produces an amine/amide link between the SWCNTs and biological systems | [150] |

| Different solubility properties of modified SWCNTs depending on the amines and solvents used | Reacting the amines octadecylamine,2-aminoanthracene, 1-H pentadecafluorooctylamine, 4-perfluorooctylamine and 2,4-bis aniline with CNTs | Intermediate behavior of SWCNTs modified with amines | [151] |

| Attaching biomolecules onto CNTs with covalent bonding | Acid-oxidizingthe CNx MWCNTs to form carboxylic acid groups and activating by EDAC (forming reactive O-acylisourea) | Forming amide bonds between the CNTx MWCNTs and proteins | [152] |

| Preparing amine F-WCNTs/PES | Using strong acids (H2SO4/HNO3) and 1,3-phenylendiamines | Removing toxic coupling reagent (SOCl2), improving the hydrophilicity of PES membranes | [125] |

| Using microwaves radiation for conjugation | Adding 3 diamines(EDA, HMDA and DBA) to the surface of MWCNT in a microwave-assisted method | Less defects in CNTs sidewalls, Fast, one-pot and simple functionalizing | [126] |

| Functionalization of CNTs with Ionic liquids | Replacing volatile organic solvents by Ionic liquids | Environment-friendly method, achieving multifunctionalizedcompound | [130] |

| Functionalization and dispersion of MXCNTs modified with Poly-Lysine | Non-covalent Functionalization of MWCNT using Poly-Lysine | Can be used in bio-nano material because of pH responsivity | [114] |

| Functionalization of CNT by nitric acid vapors | Functionalization at zeotropic concentration by adding Mg(NO3)2 salt to the HNO3 + H2O solution | Increasing the nanotube functionalization with HNO3 vapor | [153] |

| Functionalization of MWCNTs with natural amino acids under microwave irradiation | Mixing amino acid with DMAC and then sonicating MWCNT-COOH, adding NaNO2 and finally heating | Dispersing MWCNTs in polar organic solvents | [154] |

CNT: Carbon nanotube; DBA: Dibutylamine; DMAC: Dimethylacetamide; EDA: Ethylenediamine; HMDA: Hexamethylenediamine; MWCNT: Multi-walled carbon nanotube; PES: Polyethersulfone; SWCNT: Single-walled carbon nanotube.

Vázquez et al. [127] developed a strategy for the functionalization and solubilization of CNTs based on the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azomethineylides. The main advantage of this reaction was the attachment to the sidewalls of CNTs of pyrrolidine rings substituted with different functionalities. Azomethineylides were prepared by the decarboxylation of immonium salts derived from condensation of α-amino acids with aldehydes. Functioned aldehydes led to 2-substituted pyrrolidine moieties located on the sidewalls of CNTs, while N-modified α-amino acids led to N-substituted pyrrolidines. Mulvay et al. synthesized covalent amine-functionalized SWCNTs 1,3-cycloaddition using tert-butyloxycarbonyl (H-Lys-(Boc)-OH). Then, this conjugated CNT was bound to radiometalated chelator and exhibited good wrapping of siRNA [128].

Zardini et al. [129] functionalized MWCNTs with two amino acids (lysine and arginine) using microwave radiation. The NH groups indicated the occurrence of amidation reactions between the amino groups of arginine/lysine and the carboxyl groups on the surfaces of the MWCNTs. Polo-Luque et al. [130] suggested that ionic liquids could be used for functionalization reactions avoiding the use of strong acids or organic solvents. The resulting compounds obtained with the latter strategy retained the original properties of each component. The most important strategies for non-covalent and covalent functionaliztion are illustrated in (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Different methods for functionalization of CNTs.

CNT: Carbon nanotube.

4. Conclusion

There are three major methods to synthesize CNT, which differ in yield, type of CNT produced and the type and amount of impurities. New techniques have been developed in order to increase the yield of the synthetic procedure and lessen the amount of contaminants. It is almost impossible to use CNT in drug delivery without employing one of several different kinds of functionalization procedures. The functionalization strategies can be divided into two major groups: covalent and noncovalent functionalization. The first one is based on formation of chemical bonds between functional groups and CNTs, whereas in the latter case, π-π interactions are considered to be the fundamental mechanism. The negative aspect of covalent functionalization is that damage is introduced to the pristine surface which can adversely affect the electrical and optical properties of CNT. On the other hand, covalent functionalization does provide a strong linkage between the cargo and the CNT, which can be designed to be released according to the properties of the biological media in which CNT is going to be used. Research is expected to continue into different chemical strategies to functionalize CNT (both covalently and non-covalently) as interest in their use as drug-delivery vehicles continues to grow.

5. Expert opinion

In the past two decades, CNTs have attracted a tremendous amount of attention both amongst scientists and even amongst the general public. The idea of a spontaneously formed pure carbon molecule with an inherently attractive and recognizable shape has certainly struck a chord. The unique mechanical strength of CNT combined with excellent thermal and electrical conductivity properties have led to a host of applications in nanoelectronics, materials science, nano-optics, energy generation and storage technologies and so on. The question addressed in the present reviews is: do CNT have promise as a drug-delivery vehicle? Here it is fair to conclude that the jury is still out. As we have shown in Part 1, chemists have developed methods of preparing, purifying and characterizing CNT, both the multi-walled and single-walled varieties. The molecular composition of entirely sp2 hybridized carbon atoms means that CNT are extremely hydrophobic and highly prone to aggregation. These tendencies taken together mean that pristine CNT are highly incompatible with biological systems. Therefore most of the efforts to use CNT in drug delivery has centered on chemical functionalization. The functionalization strategy chosen has two side-by-side objectives: i) to provide solubility in water and reduce aggregation and ii) to provide functional groups to allow the biological cargo to be attached.

Non-covalent functionalization relies on the tendency of a wide variety of different molecules to attach themselves to, or to wrap themselves around CNT. These molecules include surfactants or detergents, synthetic polymers, nucleic acids, peptides and proteins, and carbohydrates. These molecules may be the active cargo themselves or may act as an intermediate linker to allow another active cargo to be attached. Since biological macromolecules by definition have high compatibility with water, the covering or wrapping of biomolecules around the hydrophobic CNT structure, both increases solubility and at the same time reduces aggregation. In the case of covalent functionalization, two types of functional groups commonly satisfy the requirements, namely amines and carboxylic acids. Both these groups can be ionized in water, and this dramatically increases hydrophilicity. Furthermore, established conjugation chemistry routes are available to attach biomolecules to these groups, frequently by formation of an amide bond. The fact that CNT are entirely composed of carbon atoms means that carboxylic groups can be relatively easily introduced into the molecules by treatment with strong oxidizing acids, and this has become a commonly used strategy.

One of the most discussed possible disadvantages of the use of CNT as drug-delivery vehicles is the widespread concern over nanotoxicology. This aspect has been intensively investigated in recent years, with somewhat divergent findings. A summary of these reports is given in Part 2. It is also necessary to critically analyze what are the unique properties of CNT that make them particularly suitable for use as drug-delivery vehicles, that cannot be provided by any of a large and growing range of nanoscale constructs that are also being applied in drug delivery. To our knowledge, this comparison has not yet been attempted in a convincing manner.

Nevertheless, interest in the use of CNT in biomedical applications is expected to grow strongly in the coming years, and new drug-delivery technologies are expected to play a major role in these efforts.

Article highlights.

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are receiving growing attention as drug- and gene-delivery vehicles.

Synthesis methods include arc discharge, laser ablation and chemical vapor deposition (CVD).

Several new methods for enhancing CVD using plasma, water or oxygen/carbon dioxide have been developed.

Non-covalent functionalization relies on attachment of biomolecules by coating the CNT with surfactants, synthetic polymers and biopolymers.

Covalent functionalization involves the introduction of carboxylic acids or amine groups, diazonium addition, 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition or reductive alkylation.

This box summarizes key points contained in the article.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

This work was supported by NIH grant R01A1050875. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest

• or of considerable interest

•• to readers.

- 1.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Impact of nanotechnology on drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2009;3(1):16–20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karimi M, Avci P, Mobasseri R, et al. The novel albumin–chitosan core–shell nanoparticles for gene delivery: preparation, optimization and cell uptake investigation. J Nanopart Res. 2013;15(5):1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1651-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahromi MAM, Karimi M, Azadmanesh K, et al. The effect of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles on maturation and function of dendritic cells. Comp Clin Pathol. 2014;23:1421–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karimi M, Avci P, Ahi M, et al. Evaluation of chitosan-tripolyphosphate nanoparticles as a p-shRNA delivery vector: formulation, optimization and cellular uptake study. J Nanopharm Drug Deliv. 2013;1(3):266–78. doi: 10.1166/jnd.2013.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madani SY, Tan A, Dwek M, et al. Functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes and their binding to cancer cells. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:905. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S25035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peretz S, Regev O. Carbon nanotubes as nanocarriers in medicine. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;17(6):360–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ali-Boucetta H, Al-Jamal KT, McCarthy D, et al. Multiwalled carbon nanotube–doxorubicin supramolecular complexes for cancer therapeutics. Chem Commun. 2008;(4):459–61. doi: 10.1039/b712350g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8••.Ebbesen T, Ajayan P. Large-scale synthesis of carbon nanotubes. Nature. 1992;358(6383):220–2. Reports first synthesis of carbon nanotube (CNT) in gram quantities by arc discharge under helium. [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;354(6348):56–8. First report of the preparation of nanometer-scale, needle-like tubes of carbon. Cited over 33,000 times. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernadi K, Fonseca A, Nagy J, et al. Catalytic synthesis and purification of carbon nanotubes. Synth Met. 1996;77(1):31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popov VN. Carbon nanotubes: properties and application. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2004;43(3):61–102. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gogotsi Y, Presser V. Carbon nanomaterials. 2. Taylor & Francis; New York; NY: 2013. p. 529. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu H, Bhowmik P, Zhao B, et al. Determination of the acidic sites of purified single-walled carbon nanotubes by acid–base titration. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;345(1):25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14•.Dresselhaus M, Jorio A, Souza Filho A, et al. Defect characterization in graphene and carbon nanotubes using Raman spectroscopy. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2010;368(1932):5355–77. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0213. Shows how to quantify and analyze defects in CNT side-walls. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Lu W, Zu M, Byun JH, et al. State of the art of carbon nanotube fibers: opportunities and challenges. Adv Mater. 2012;24(14):1805–33. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104672. Review of CNT fibers for industrial and materials science applications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinnott SB, Andrews R. Carbon nanotubes: synthesis, properties, and applications. Crit Rev Solid State Mater Sci. 2001;26(3):145–249. [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Baughman RH, Zakhidov AA, de Heer WA. Carbon nanotubes – the route toward applications. Science. 2002;297(5582):787–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1060928. Early forward-looking review on future applications of CNT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong EW, Sheehan PE, Lieber CM. Nanobeam mechanics: elasticity, strength, and toughness of nanorods and nanotubes. Science. 1997;277(5334):1971–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chhowalla M, Unalan HE. Plasma processing of nanomaterials. Taylor & Francis; New York; NY: 2011. Cathodic arc discharge for synthesis of carbon nanoparticles; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishigami M, Cumings J, Zettl A, et al. A simple method for the continuous production of carbon nanotubes. Chem Phys Lett. 2000;319(5):457–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousef S, Khattab A, Osman T, et al. Fully automatic system for producing carbon nanotubes (CNTs) by using arc-discharge technique multi electrodes. Innovative Engineering Systems (ICIES), 2012 First International Conference on; 2012; IEEE; 2012. pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y-L, Hou P-X, Liu C, et al. De-bundling of single-wall carbon nanotubes induced by an electric field during arc discharge synthesis. Carbon. 2014;74:370–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sano N, Nakano J, Kanki T. Synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotubes with nanohorns by arc in liquid nitrogen. Carbon. 2004;42(3):686–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24•.Vittori Antisari M, Marazzi R, Krsmanovic R. Synthesis of multiwall carbon nanotubes by electric arc discharge in liquid environments. Carbon. 2003;41(12):2393–401. Points out the importance of liquid environments in CNT synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imasaka K, Kanatake Y, Ohshiro Y, et al. Production of carbon nanoonions and nanotubes using an intermittent arc discharge in water. Thin Solid Films. 2006;506:250–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Li X, Jiang B, et al. Formation of carbon nanotubes in water by the electric-arc technique. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;366(5):664–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang S-D, Chang M-H, Lan KM-D, et al. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes by arc discharge in sodium chloride solution. Carbon. 2005;43(8):1792–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaudhary K, Ali J, Yupapin P. Growth of small diameter multi-walled carbon nanotubes by arc discharge process. Chinese Phys B. 2014;23(3):035203. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su Y, Wei H, Li T, et al. Low-cost synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotubes by low-pressure air arc discharge. Mater Res Bull. 2014;50:23–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bota P, Dorobantu D, Boerasu I, et al. Synthesis of single-wall carbon nanotubes by excimer laser ablation. Surf Eng Appl Electrochem. 2014;50(4):294–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iijima S. Direct observation of the tetrahedral bonding in graphitized carbon black by high resolution electron microscopy. J Cryst Growth. 1980;50(3):675–83. doi: 10.1155/2013/785160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maser WK, Benito AM, Munoz E, et al. Production of carbon nanotubes by CO2-laser evaporation of various carbonaceous feedstock materials. Nanotechnology. 2001;12(2):147. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/12/2/315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mubarak N, Abdullah E, Jayakumar N, et al. An overview on methods for the production of carbon nanotubes. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(4):1186–97. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rastogi V, Yadav P, Bhattacharya SS, et al. Carbon nanotubes: an emerging drug carrier for targeting cancer cells. J Drug Deliv. 2014;2014:670815. doi: 10.1155/2014/670815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jose-Yacaman M, Miki-Yoshida M, Rendon L, et al. Catalytic growth of carbon microtubules with fullerene structure. Appl Phys Lett. 1993;62(2):202–4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin L, Zhou D, Krauss A, et al. Growing carbon nanotubes by microwave plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Appl Phys Lett. 1998;72(26):3437–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong J, Soh HT, Cassell AM, et al. Synthesis of individual single-walled carbon nanotubes on patterned silicon wafers. Nature. 1998;395(6705):878–81. doi: 10.1038/27632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fonseca A, Hernadi K, Nagy J, et al. Optimization of catalytic production and purification of buckytubes. J Mol Cat A Chem. 1996;107(1):159–68. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahoo SC, Mohapatra DR, Lee H-J, et al. Carbon nanoflake growth from carbon nanotubes by hot filament chemical vapor deposition. Carbon. 2014;67:704–11. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.10.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lisi N, Giorgi R, Re M, et al. Carbon nanowall growth on carbon paper by hot filament chemical vapour deposition and its microstructure. Carbon. 2011;49(6):2134–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouanis FZ, Baraton L, Huc V, et al. High-quality single-walled carbon nanotubes synthesis by hot filament CVD on Ru nanoparticle catalyst. Thin Solid Films. 2011;519(14):4594–7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pastorková K, Jesenák K, Kadlečíková M, et al. The growth of multi-walled carbon nanotubes on natural clay minerals (kaolinite, nontronite and sepiolite) Appl Surf Sci. 2012;258(7):2661–6. [Google Scholar]

- 43••.Sanchez-Valencia JR, Dienel T, Gröning O, et al. Controlled synthesis of single-chirality carbon nanotubes. Nature. 2014;512(7512):61–4. doi: 10.1038/nature13607. Description of synthetic method for single chirality CNT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swierczewska M, Rusakova I, Sitharaman B. Gadolinium and europium catalyzed growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon. 2009;47(13):3139–42. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Melechko AV, Merkulov VI, McKnight TE, et al. Vertically aligned carbon nanofibers and related structures: controlled synthesis and directed assembly. J Appl Phys. 2005;97(4):041301. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saghafi M, Mahboubi F, Mohajerzadeh S, et al. Preparation of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes and their electrochemical performance in supercapacitors. Synth Met. 2014;195:252–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Löffler R, Häffner M, Visanescu G, et al. Optimization of plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition parameters for the growth of individual vertical carbon nanotubes as field emitters. Carbon. 2011;49(13):4197–203. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeong KY, Jung HK, Lee HW. Effective parameters on diameter of carbon nanotubes by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Trans Nonferrous Metals Soc China. 2012;22:s712–s16. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fleaca CT, Le Normand F. Ni-catalysed carbon nanotubes and nanofibers assemblies grown on TiN/Si (100) substrates using hot-filaments combined with dc plasma CVD. Physica E Low Dimensional Syst Nanostruct. 2014;56:435–40. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang B, Tang X, Xu X. Growth of carbon nanotubes and nanowires from amorphous carbon films by plasma-enhanced hot filament chemical vapor deposition. J Phys Chem Solids. 2013;74(3):441–5. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Moore JJ. Low temperature growth mechanisms of vertically aligned carbon nanofibers and nanotubes by radio frequency-plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Carbon. 2012;50(3):1235–42. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dervishi E, Biris AR, Driver JA, et al. Low-temperature (150° C) carbon nanotube growth on a catalytically active iron oxide–graphene nano-structural system. J Catal. 2013;299:307–15. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee CJ, Park J, Han S, et al. Growth and field emission of carbon nanotubes on sodalime glass at 550 C using thermal chemical vapor deposition. Chem Phys Lett. 2001;337(4):398–402. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park YS, Yi J, Lee J. The characteristics of carbon nanotubes grown at low temperature for electronic device application. Thin Solid Films. 2013;546:81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee J-H, Hong B, Park YS. The electrical and structural properties of carbon nanotubes grown by microwave plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition method for organic thin film transistor. Thin Solid Films. 2013;546:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 56•.Hata K, Futaba DN, Mizuno K, et al. Water-assisted highly efficient synthesis of impurity-free single-walled carbon nanotubes. Science. 2004;306(5700):1362–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1104962. First description of water-assisted CNT synthesis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang G, Chen J, Tian Y, et al. Water assisted synthesis of double-walled carbon nanotubes with a narrow diameter distribution from methane over a Co–Mo/MgO catalyst. Catal Today. 2012;183(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smajda R, Andresen J, Duchamp M, et al. Synthesis and mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes produced by the water assisted CVD process. Physica Status Solidi (B) 2009;246(11–12):2457–60. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada T, Maigne A, Yudasaka M, et al. Revealing the secret of water-assisted carbon nanotube synthesis by microscopic observation of the interaction of water on the catalysts. Nano Lett. 2008;8(12):4288–92. doi: 10.1021/nl801981m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ren F, Kanaan SA, Majewska MM, et al. Increase in the yield of (and selective synthesis of large-diameter) single-walled carbon nanotubes through water-assisted ethanol pyrolysis. J Catal. 2014;309:419–27. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cui X, Wei W, Chen W. Lengthening and thickening of multi-walled carbon nanotube arrays grown by chemical vapor deposition in the presence and absence of water. Carbon. 2010;48(10):2782–91. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim Y, Song W, Lee SY, et al. Growth of millimeter-scale vertically aligned carbon nanotubes by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition. Jpn J Appl Phys. 2010;49(8R):085101. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qi J, Zhang L, Cao J, et al. Effects of oxygen on growth of carbon nanotubes prospered by PECVD. Mater Res Bull. 2014;49:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wen Q, Qian W, Wei F, et al. CO2-assisted SWNT growth on porous catalysts. Chem Mater. 2007;19(6):1226–30. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murakami Y, Chiashi S, Miyauchi Y, et al. Growth of vertically aligned single-walled carbon nanotube films on quartz substrates and their optical anisotropy. Chem Phys Lett. 2004;385(3):298–303. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar M, Ando Y. A simple method of producing aligned carbon nanotubes from an unconventional precursor–Camphor. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;374(5):521–6. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huczko A. Synthesis of aligned carbon nanotubes. Appl Phys A. 2002;74(5):617–38. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reit R, Nguyen J, Ready WJ. Growth time performance dependence of vertically aligned carbon nanotube supercapacitors grown on aluminum substrates. Electrochim Acta. 2013;91:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rao CN, Govindaraj A. Carbon nanotubes from organometallic precursors. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35(12):998–1007. doi: 10.1021/ar0101584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng H, Li F, Su G, et al. Large-scale and low-cost synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotubes by the catalytic pyrolysis of hydrocarbons. Appl Phys Lett. 1998;72(25):3282–4. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jasti R, Bertozzi CR. Progress and challenges for the bottom-up synthesis of carbon nanotubes with discrete chirality. Chem Phys Lett. 2010;494(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.04.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Magrez A, Seo JW, Smajda R, et al. Catalytic CVD synthesis of carbon nanotubes: towards high yield and low temperature growth. Materials. 2010;3(11):4871–91. doi: 10.3390/ma3114871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Taghdisi SM, Lavaee P, Ramezani M, et al. Reversible targeting and controlled release delivery of daunorubicin to cancer cells by aptamer-wrapped carbon nanotubes. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;77(2):200–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.12.005. Interesting use of RNA aptamer to specific all deliver anticancer drugs to tumor cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74•.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, et al. In vivo biodistribution and highly efficient tumour targeting of carbon nanotubes in mice. Nat Nanotechnol. 2006;2(1):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. Report that CNT can be used to target tumors in mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75•.Marchesan S, Kostarelos K, Bianco A, et al. The winding road for carbon nanotubes in nanomedicine. Mater Today. 2014 Discussion of possible medical applications of CNT. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sitko R, Zawisza B, Malicka E. Modification of carbon nanotubes for preconcentration, separation and determination of trace-metal ions. TrAC Trends Anal Chem. 2012;37:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- 77.He H, Pham-Huy LA, Dramou P, et al. Carbon nanotubes: applications in pharmacy and medicine. BioMed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/578290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wong BS, Yoong SL, Jagusiak A, et al. Carbon nanotubes for delivery of small molecule drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(15):1964–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Plisko TV, Bildyukevich AV. Debundling of multiwalled carbon nanotubes in N, N-dimethylacetamide by polymers. Colloid Polym Sci. 2014;292(10):2571–80. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Islam M, Rojas E, Bergey D, et al. High weight fraction surfactant solubilization of single-wall carbon nanotubes in water. Nano Lett. 2003;3(2):269–73. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moore VC, Strano MS, Haroz EH, et al. Individually suspended single-walled carbon nanotubes in various surfactants. Nano Lett. 2003;3(10):1379–82. [Google Scholar]

- 82•.Chen RJ, Zhang Y, Wang D, et al. Noncovalent sidewall functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes for protein immobilization. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123(16):3838–9. doi: 10.1021/ja010172b. Describes non-covalent functionalization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Granite M, Radulescu A, Pyckhout-Hintzen W, et al. Interactions between block copolymers and single-walled carbon nanotubes in aqueous solutions: a small-angle neutron scattering study. Langmuir. 2010;27(2):751–9. doi: 10.1021/la103096n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duch MC, Budinger GS, Liang YT, et al. Minimizing oxidation and stable nanoscale dispersion improves the biocompatibility of graphene in the lung. Nano Lett. 2011;11(12):5201–7. doi: 10.1021/nl202515a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang X, Xia T, Duch MC, et al. Pluronic F108 coating decreases the lung fibrosis potential of multiwall carbon nanotubes by reducing lysosomal injury. Nano Lett. 2012;12(6):3050–61. doi: 10.1021/nl300895y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Choudhary U, Northrop BH. Rotaxanes and biofunctionalized pseudorotaxanes via thiol-maleimide click chemistry. Org Lett. 2012;14(8):2082–5. doi: 10.1021/ol300614z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87•.Wang L, Shi J, Zhang H, et al. Synergistic anticancer effect of RNAi and photothermal therapy mediated by functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(1):262–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.037. Use of CNT as a dual function anticancer therapeutic combining RNAi and laser-mediated photothermal targeting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Modi CD, Patel SJ, Desai AB, et al. Functionalization and evaluation of PEGylated carbon nanotubes as novel drug delivery for methotrexate. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2011;1:103–8. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mehra NK, Mishra V, Jain N. A review of ligand tethered surface engineered carbon nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2014;35(4):1267–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu Z, Tang L-J, Zhang X-B, et al. Aptamer-modified nanodrug delivery systems. ACS Nano. 2011;5(10):7696–9. doi: 10.1021/nn2037384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chou SG, Plentz F, Jiang J, et al. Phonon-assisted excitonic recombination channels observed in DNA-wrapped carbon nanotubes using photoluminescence spectroscopy. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94(12):127402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.127402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Enyashin AN, Gemming S, Seifert G. DNA-wrapped carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(24):245702. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Das BK, Tlili C, Badhulika S, et al. Single-walled carbon nanotubes chemiresistor aptasensors for small molecules: picomolar level detection of adenosine triphosphate. Chem Commun. 2011;47(13):3793–5. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04733c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94••.Star A, Steuerman DW, Heath JR, et al. Starched carbon nanotubes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41(14):2508–12. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2508::AID-ANIE2508>3.0.CO;2-A. First report that carbohydrates can be used to disperse CNT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim O-K, Je J, Baldwin JW, et al. Solubilization of single-wall carbon nanotubes by supramolecular encapsulation of helical amylose. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(15):4426–7. doi: 10.1021/ja029233b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Xie Y, Soh A. Investigation of non-covalent association of single-walled carbon nanotube with amylose by molecular dynamics simulation. Mater Lett. 2005;59(8):971–5. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Numata M, Asai M, Kaneko K, et al. Inclusion of cut and as-grown single-walled carbon nanotubes in the helical superstructure of schizophyllan and curdlan (beta-1, 3-glucans) J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(16):5875–84. doi: 10.1021/ja044168m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chambers G, Carroll C, Farrell GF, et al. Characterization of the interaction of gamma cyclodextrin with single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2003;3(6):843–6. [Google Scholar]

- 99.He J-L, Yang Y, Yang X, et al. Beta-cyclodextrin incorporated carbon nanotube-modified electrode as an electrochemical sensor for rutin. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2006;114(1):94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bandyopadhyaya R, Nativ-Roth E, Regev O, et al. Stabilization of individual carbon nanotubes in aqueous solutions. Nano Lett. 2002;2(1):25–8. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bhoi VI, Imae T, Ujihara M, et al. Surface immobilization of carbon nanotubes by beta-cyclodextrins and their inclusion ability. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13(4):2604–12. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2013.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Karadas N, Ozkan SA. Electrochemical preparation of sodium dodecylsulfate doped over-oxidized polypyrrole/multi-walled carbon nanotube composite on glassy carbon electrode and its application on sensitive and selective determination of anticancer drug: pemetrexed. Talanta. 2014;119:248–54. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Popp BV, Miles DH, Smith JA, et al. Stabilization and functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes with polyvinylpyrrolidone copolymers for applications in aqueous media. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem. 2015;53:337–43. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kayatin MJ, Davis VA. In situ polymerization functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes with polystyrene. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem. 2013;51(17):3716–25. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sahmetlioglu E, Yilmaz E, Aktas E, et al. Polypyrrole/multi-walled carbon nanotube composite for the solid phase extraction of lead (II) in water samples. Talanta. 2014;119:447–51. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]