Abstract

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has long been regarded a general contraindication in patients with cardiovascular implanted electronic devices such as cardiac pacemakers or cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) due to the risk of severe complications and even deaths caused by interactions of the magnetic resonance (MR) surrounding and the electric devices. Over the last decade, a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms responsible for such potentially life-threatening complications as well as technical advances have allowed an increasing number of pacemaker and ICD patients to safely undergo MRI. This review lists the key findings from basic research and clinical trials over the last 20 years, and discusses the impact on current day clinical practice. With ‘MR-conditional’ devices being the new standard of care, MRI in pacemaker and ICD patients has been adopted to clinical routine today. However, specific precautions and specifications of these devices should be carefully followed if possible, to avoid patient risks which might appear with new MR technology and further increasing indications and patient numbers.

Keywords: Cardiac pacemaker, Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging, ICD, Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, MRI conditional devices, MRI safety

“A person with a new idea is a crank until the idea succeeds”.

Mark Twain

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging technique of choice in a wide range of diagnostic tasks regarding neurological disorders, muscular and skeletal diseases. Most important, MRI offers better soft tissue contrast than other imaging modalities without the use of ionizing radiation. In the cardiovascular field, MRI is now considered the gold standard in the assessment of global and regional myocardial function, the detection of myocardial damage and viability after myocardial infarction, in congenital heart disease, and for detection of cardiac inflammation or infiltration in rare diseases like e.g. Fabry disease or certain haematological disorders.1 At the same time, the number of patients with a cardiovascular implanted electronic device (CIED) is rapidly and constantly growing, now comprising several million patients worldwide. As early as in 2005, it was already estimated that ∼75% of all patients with pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) systems will have the future need for an MRI investigation due to the high probability of comorbidities such as stroke, lumbar disease, arthritis, or cancer in this patient group.2 However, one decade ago, MRI in patients with implanted cardiac devices was still denied due to serious safety concerns. It was not before 2011 that the FDA approved the first magnetic resonance (MR) conditional pacemaker system. In the following, we review the development of the devices and clinical trials over the last 10 years that led to the current EMA approval which now allows examining not only pacemaker, but even ICD patients in 1.5 and 3 T MR scanners, given certain prerequisites.

Adverse events

The safety of MRI examinations in patients with implanted rhythm devices was always high on the agenda in both the imaging and rhythmology community. Nevertheless, several fatal events occurred worldwide in the 20th century. However, these incidents were generally only poorly documented, because the MRI staff was not aware of the devices, and, therefore, MRI examinations were not well supervised particularly by a specifically trained cardiologist.3–8

Following in vitro and in vivo studies mainly focusing on radio frequency (RF) heating at the tip of cardiac pacemaker leads due to MRI raised safety concerns even further.9,10 In a similar well-documented clinical setting, severe and permanent injuries because of RF burns related to implanted electrodes for deep brain stimulation were recorded during MRI.11 Reports on increased pacing thresholds in some pacemaker patients after MRI also showed that RF heating around the lead tip may jeopardize the patient.12,13 Other raised safety issues included higher-grade battery impairment and electronic dysfunction.13,14 Experimental studies in a pig model proved the actual potential for induction of ventricular tachycardia during MR imaging of cardiac pacemakers.10 Therefore, earlier guidelines declared cardiac pacemakers and ICDs as a contraindication for routine MRI.15

Technical considerations

When using MRI technique for imaging, different kinds of electromagnetic fields are utilized, which have the potential to interfere with the leads of cardiac pacemakers or ICDs: the static magnetic field, the pulsed gradient fields, and the RF fields. From the large variety of potential risks patients with CIED are exposed in the MRI environment originating from these different electromagnetic fields, three basic effects can be differentiated: mechanical effects, electromagnetic effects, and thermal effects.

Mechanical effects

While mechanical movement–eventually leading to device or lead dislocation–originally was one of the most feared threats, even older pacemaker leads do not contain strong ferromagnetic materials.16 Therefore, the static magnetic field currently used in routine clinical MRI settings—that is, up to 3 T—shows no or only negligible interference with the leads. This does not hold true for the electronic devices, which contain several ferromagnetic components. Even though these ferromagnetic device components in cardiac rhythm devices continue to decrease, some essential parts such as the battery and transformers for charging capacitors in ICDs remain unexceptionally necessary. The threat of mechanical pacemakers or ICDs device movement increases with the magnetic field strength, the amount of ferromagnetic materials within the device, the distance from the bore of the MR scanner, and the stability of the device in the pocket (i.e. older implants have a fibrotic envelope).17 Further experimental research proved mechanical force and torque effects under current day clinical practice in 1.5 T scanners to be in the order of physiological gravity and acceleration effects.18

Electromagnetic effects

In addition to mechanical device dislodgment, the static magnetic field may also have an impact on device function by affecting the reed switch behaviour. In theory, activation of the reed switch by a magnet sets a pacemaker to asynchronous mode, disables tachycardia detection, and/or therapy with subsequent fatal results in case a ventricular tachycardia is induced or occurs spontaneously and is not immediately terminated externally by the attending staff.

The pulsed gradient as well as RF fields of the scanner can induce electric currents in pacemaker leads, which can lead to over- or undersensing in CIED which might prevent necessary cardiac pacing by the device, or trigger anti-tachycardia pacing or shock by the device (Figure 1). However, actual ICD shock delivery in the scanner bore will in most cases not be possible due to the effects of the external magnetic field on the ICD capacitor.19 This not only might lead to battery depletion but also has to be considered in case an actual tachycardia occurs in the scanner bore. In addition, pulsed gradient fields might be strong enough to electrically stimulate the heart and eventually cause ventricular arrhythmias.20,21 In well-monitored patients, this effect seems to be rare in clinical practice.22 However, theoretical hazards have been experimentally replicated, proving that in the swine model these effects can indeed cause clinically relevant tachycardia.10,23 Therefore, arrhythmia induction might be the most probable explanation for the few reported fatal casualties of pacemaker patients in the MRI.4,8

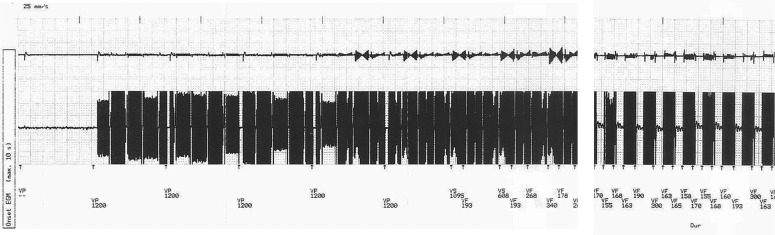

Figure 1.

Two representative intracardiac electrogram readouts from conventional implantable cardioverter defibrillators during magnetic resonance imaging. Note pacing inhibition and VT detection due to radio frequency noise after starting magnetic resonance imaging. Potential incidence of accordant effects is dependent on many factors such as device, device programming, scanner, and pulse sequence characteristics.

Heating effects

In contrast to the pulsed gradient fields used for local encoding in MRI, which basically show electric interference with CIED, the repeated RF pulses used for signal induction in MRI induce strong electric fields in the body, leading to RF energy deposition into the tissue.24 This can result in heating of the body tissue up to several degrees Celsius even in patients without CIED. The amount of actual energy deposition in the surrounding tissue is basically given by the specific absorption rate and also depends on the size and shape of the body and the imaging protocol. The leads of CIED can show strong electromagnetic coupling effects with these RF fields induced in the body.25–27 This so-called ‘antenna effect’ is accompanied by the possibility of particularly intense local heating (Figure 2) and subsequent tissue damage due to oedema or necrosis at small device-to-tissue interfaces such as the tip of the lead.28 These thermal effects might eventually lead to an increase in pacing threshold, capture loss, or arrhythmia induction. Specific absorption rate, lead design, and configuration of the leads in the body are key determinants of local RF energy deposition.21,28 Fractured or abandoned leads, or epicardial leads that are not cooled by blood flow may carry an increased risk of severe heating.29 Also adequate selection of magnetic resonance imaging landmark can significantly reduce potential heating hazards in CIED patients.30

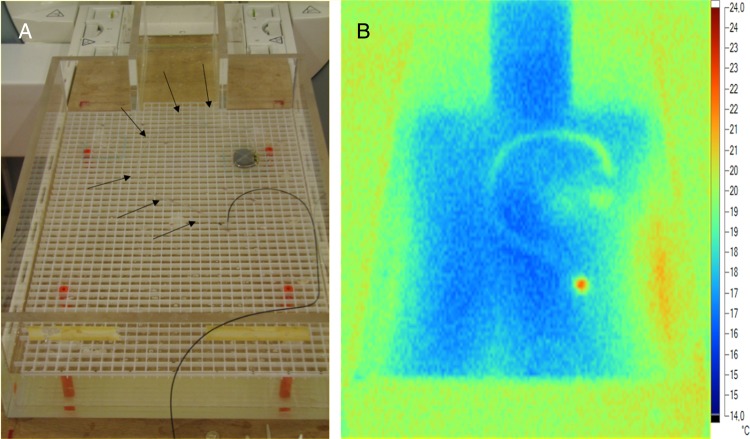

Figure 2.

Visualization of pacemaker heating due to radio frequency pulses in magnetic resonance imaging. (A) Experimental setup emulating left thoracic implantation of a conventional one-chamber pacemaker system in a gel-filled torso phantom. Arrows indicate pacemaker lead. The (black) temperature probe is attached to the tip of the pacemaker lead. (B) Heat map assessed by an infrared camera after 2 min of magnetic resonance imaging using a turbo spin echo sequence indicates the temperature increase at the lead tip.

Magnetic resonance imaging and cardiovascular implanted electronic device in the early 20th century

One decade ago, the rapid development and use of MRI and CIED in clinical practice, the technical considerations and several clinical reports on the occurrence or absence of adverse events led to a rapidly increasing interest in the topic not only in cardiologists and radiologists but also the cardiovascular device industry. In an editorial to a focused issue on this topic in 2005, it was stressed out that in order to make MR scanning as safe as possible, there would have to be an industry-wide effort from concept to market to design and construct implantable cardiac devices and leads for the MRI environment.31 In this regard, all components of an implantable system need to be developed, tested, and proven safe for current and evolving MRI technologies. This viewpoint was also shared by the device companies, who accepted the challenge to address this unmet medical need by designing future device systems to be safe by design not by chance.32–34

Clinical trials on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with conventional PMs and implantable cardioverter defibrillators

In 2007, data and observations listed above were summarized in the focused guidelines on safety of MRI in patients with cardiovascular devices endorsed by several key organizations in Cardiology and Radiology, designating MRI scanning of patients with PM and ICD as contraindicated.15 However, over the last 20 years, an array of mostly smaller clinical studies investigated safety aspects of clinical MRI scans in pacemaker patients. The studies differed in terms of field strength (0.2–3 T), type and body region of MR scan, imaging protocol, limitations of specific absorption rate, and of course the pacemaker type (single or dual chamber) and device manufacturer.

Pacemaker patients

Most early studies focused on examinations in 0.5 T scanners.35–38 In a total of 99 patients, no major adverse events were reported. Problems reported were activation of the Reed switch and diminished battery voltage in selected patients.38 One recent study investigating the effects in a current day low-field MRI scanner was performed at 0.2 T.39 In 114 patients, no adverse events were detected.

Until then, 14 studies assessed the outcome in 1.5 T MR scanners in a total of 806 patients.12,13,40–51 There were no major difficulties or adverse events reported. Similar to the trials in the 0.5 T MR tomographs, an impact on the functioning of the devices was seen in several cases, including a decrease in battery voltage, an increase in pacing thresholds, or power-on-resets. The detected changes in lead parameters did not require surgical revision or reprogramming. The largest study also addressed long-term effects. One hundred and fifteen examinations were performed on 82 patients. An increase in pacing thresholds of >1.0 V was noted in 3% of the leads. In seven patients, an electrical reset of their pacemakers requiring new device programming was detected.13 A Spanish study focusing on 2.0 T MRI reported uneventful scanning of 13 patients.52

Recently, the first studies were performed at 3.0 T to evaluate the safety of cardiac electronic implants at higher magnetic field strengths. In a total of 44 patients, all receiving cranial MR scans using a transmit-receive head coil, there were no clinically relevant alterations in device configuration and parameters, no arrhythmias, and no electrical resets.53 One trial on 14 patients with no scan restriction showed also no adverse events.54

The major clinical studies on MRI in patients with cardiac pacemakers are summarized in Table 1. Of note, 15 trials (of 24) did not include pacemaker-dependent patients. This might temper the results with regard to safety of MR scans in these patients.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of magnetic resonance imaging in pacemaker patients

| Field strength | Trial | No. of patients | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | Strach et al.39 | 114 | – |

| 0.5 | Sommer et al.36 Sommer et al.37 |

18 44 |

Reed switch activation, continuous pacing in the static field – |

| Valhaus et al.38 | 32 | Decrease in battery voltage, reed switch activation | |

| Gimbel et al.35 | 5 | One power-on-reset | |

| 1.5 | Martin et al.12 | 54 | Significant threshold changes in 9% of leads |

| Gimbel et al.40 | 10 | Seven patients had alterations in pacing thresholds | |

| Sommer et al.13 | 82 | Increased capture threshold. In 4/115 patients troponin increased | |

| Nazarian et al.41 | 31 (55 total) | – | |

| Mollerus et al.42 Mollerus et al.44 |

32 (37 total) 46 (52 total) |

– Ectopy |

|

| Naehle et al.43 | 47 | Repetitive scans (171 examinations in 47 patients) caused decreased pacing capture, battery voltage | |

| Mollerus et al.45 | 105 (127 total) | Decreased sensing amplitudes and impedances | |

| Halshtok et al.46 | 9 (18 total) | Five power-on-resets | |

| Burke et al.47 | 24 (38 total) | – | |

| Buendia et al.48 | 28 (33 total) | Two temporary communication failures, one sensing error, one safety signal | |

| Nazarian et al.49 | 237 (438 total) | Two power-on-resets, significant changes in lead parameters | |

| Cohen et al.50 | 69 (109 total) | Decreases in battery voltage in 4%, pacing threshold increases in 3%, impedance changes in 6% | |

| Boilson et al.51 | 32 | 5× power-on-reset, 3× asynchronous pacing | |

| 2.0 | Del Ojo et al.52 | 13 | – |

| 3.0 | Naehle et al.53 | 44 | – |

| Gimbel54 | 14 | – |

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients

The impact of 1.5 T MR scanning on device function in ICD patients was investigated in 13 studies.41–50,55–58 Overall, 365 patients were included. The best powered trial with regard to patient numbers to evaluate the safety of MRI in ICD patients was performed in 201 patients.49 To assess long-term adverse effects, device interrogation was between 3 and 6 months after the MRI procedure. Even though smaller events were reported, there were no clinically significant changes that necessitated device reprogramming or revision of generator or leads. Of note, three of the patients experienced power-on resets during either cardiac or cranial MR scans. This study subsumed that MRI might be an option in ICD patients with no imaging alternative, provided MRI is carried out in centres with specific expertise and equipment.

The major clinical studies of MRI scans performed in patients with ICDs are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical trials of magnetic resonance imaging in implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients

| Field strength | Trial | No. of patients | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5 | Coman et al.55 | 11 | One short asymptomatic pause in pacing during scanning, One power-on-reset |

| Gimbel et al.58 | 7 | One power-on-reset | |

| Nazarian et al.41 | 24 (55 total) | – | |

| Mollerus et al.42 | 5 (37 total) | – | |

| Pulver et al.57 | 8 | – | |

| Mollerus et al.44 | 22 (127 total) | Decreased sensing amplitudes and impedances | |

| Halshtok et al.46 | 9 (18 total) | – | |

| Burke et al.47 | 14 (38 total) | – | |

| Buendia et al.48 | 5 (33 total) | One sensing error | |

| Nazarian et al.49 | 201 (438 total) | One power-on-reset, changes in pacing threshold | |

| Cohen et al.50 | 40 (109 total) | Decreases in battery voltage, pacing threshold increases, and impedance changes |

Many trials on MRI in CIED patients also included patients with a need for chest scans. Even though theoretical considerations as well as experimental findings suggest additional risks30 in these patients, there is no clear evidence yet in these clinical trials that chest scanning is more prone to adverse events than scanning with a thoracic exclusion zone.

Imaging artefacts in patients with cardiovascular implanted electronic device

Metallic and other electrically conductive medical devices might not only cause direct harm to the patient in the MRI environment but also bear the risk to disturb MR images. This can significantly hamper diagnostic value of MRI, particularly if the cardiovascular devices are implanted close to the area of interest, like in cardiac or breast imaging (Figure 3). While accordant investigations found most modern pacemaker systems to show only little effect on cardiac MR images—at least when implanted in the right pectoral region—especially ICD systems will often cause larger imaging artefacts or even total signal void in cardiac images mainly due to the larger battery.59,60 This effect can even be experienced in MR conditional devices and should already be taken into account before the patient is admitted to the MRI rather than referred for an alternative diagnostic technique.

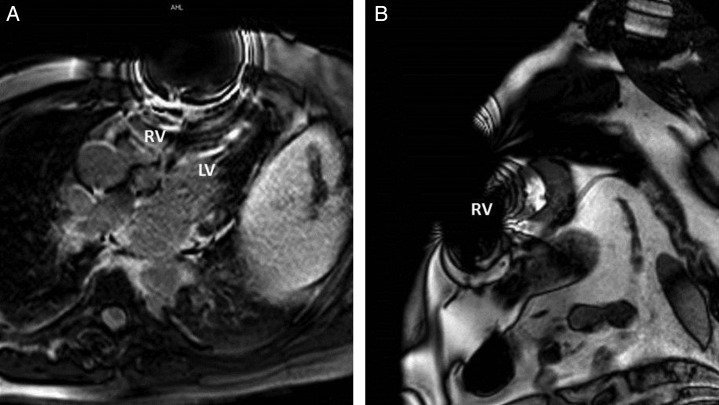

Figure 3.

Representative magnetic resonance imaging artefacts in patients with a left thoracic cardiovascular implanted electronic device. (A) Four-chamber view. (B) Short-axis view. Image distortion/void hampering diagnostic image quality particularly regarding the right ventricle and anterior wall of the left ventricle is apparent. RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

Magnetic resonance-conditional cardiovascular electronic devices

As a superordinate system to classify MRI safety, the following terminology has been established in medical products15:

MRI Safe: The item is safe for use in MRI under all conditions.

MRI Unsafe: The item is not safe for use in MRI under any conditions.

MRI Conditional: The item is safe for use in MRI only under certain conditions.

Comprehensive research over the last decade has led to the development of MR-conditional CIED. These systems contain specific hardware and software components, which have been tested and officially approved for the MRI environment under certain predefined conditions. Such hardware alterations regarding the devices include the minimization of ferromagnetic materials to reduce mechanical forces and vibrations, the use of specific filters to prevent over- and undersensing, and replacement of the Reed switch by a Hall sensor to exclude unpredictable activation in the magnetic field. Magnetic resonance imaging conditional pacemakers and ICDs were also provided with a special MRI software mode, which has to be activated by the physician before the patient enters the MRI. This software mode typically includes features like bipolar stimulation with high-voltage output in VOO mode for pacemaker-dependent patients, or temporarily turns off therapy.

The risk for unintended coupling of the leads with the gradient and RF fields has been lowered by specific alterations in lead design, namely to reduce the risk of uncontrolled pacing and excessive heating of the lead tip.21,28,61,62 During the past years, several additional model lines have received the FDA or EMA approval for clinical use. The first device officially labelled MR conditional in the EU was released in 2008, and the first FDA-approval for the U.S. market followed in 2011. A randomized clinical trial investigating the effects of MRI in these devices showed no major complications and only mild changes in capture and sensing values, confirming a convenient safety profile in clinical practice.63 As a main advantage over the earlier MR conditional devices, the follow-up product of this first MR conditional system is approved for full body MRI scans without an exclusion zone. This system has been evaluated in an unblinded clinical study,62 showing no major complications. Other device companies followed this example launching their MR conditional pacemakers between 2010 and 2012.

Currently, an increasing number of cardiovascular devices is approved for MRI by the regulatory authorities and there is continuous energetic development in the field. Main device-specific considerations particularly refer to the field strength of the scanner (mostly 1.5 T), the permitted scan zone (no thoracic exclusion zone), and sequence specific SAR (<2.0 W/kg). In November 2011, for the first time an ICD system was labelled MR conditional for 1.5. Today, even 3.0 T MRI in several of these devices is possible, and also the first CRT-D systems gained approval for the MRI. Current manufacturer-specific recommendations are listed in Supplementary material online, Table S1. An overview of CIED currently labelled MR conditional is given in Supplementary material online, Tables S2 and S3. Additional information can also be obtained from noncommercial websites on this subject (www.MRIsafety.com, Accessed 13 march 2015).

‘Off-label magnetic resonance imaging’ in patients with cardiovascular implanted electronic device

As a result of the comprehensive research and several clinical trials performed over the last years, as well as the generally accepted clinical need, the majority of new devices entering the market in the future is very likely to be labelled ‘MR conditional’. In these devices, manufacturer recommendations should be followed as strictly as possible by the treating physicians if patients are referred to the MRI, in order to avoid unnecessary acute or long-term risks for the patient. Despite this fact there might still be indications for MRI overextending current manufacturer recommendations and/or approval. Moreover, many patients with older CIED not labelled MR conditional will have the need for an MRI in the near future, particularly in the light of new improved MRI techniques and diagnostic indications appearing constantly. Recently, several authors have claimed that MRI should still be considered a diagnostic option in these patients,19,59 because based on the findings from several recent clinical studies published, a low complication rate can be expected. However, the approach to perform MRI in patients with non-MR conditional CIED requires specific extended background knowledge and expertise, and also additional resources such as the ability for device programming and patient surveillance.64 Therefore, such an approach is expected to most likely remain in the hands of a few specialized centres in the near future. With the broad number of already existing implanted CIED components, and the advancing MR technique with more advanced imaging techniques and probably higher field strengths, MRI in patients with unsafe pacemaker and ICD systems will remain a problem over the next years.

General recommendations for magnetic resonance unsafe cardiovascular implanted electronic device

Open issues regarding MR safety remain in patients

– without MR conditional devices

– with MR conditional devices and abandoned leads

– with MR conditional devices (impulse generators) but non-conditional leads

– with devices separately labelled MR conditional, but not as a system

If MRI is considered in such patients, a comprehensive patient-specific risk-to-benefit analysis should be performed, with a particular focus on available potential alternative imaging methods. Some aspects to be considered in this regard are listed in the following. Despite the fact that some of the measures are also mentioned in the 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing,64 these recommendations are not based on officially delivered guidelines, but rely on the findings from the large set of basic research, clinical studies, and/or expert opinions. The following suggestions therefore represent the authors' vision on the subject on the basis of these external findings and personal experience:

– Sensing, pacing threshold, and lead impedances should be in a normal range.13

– No other implants should be present in the patient's body.21

– No abandoned or epicardial leads should be present.29

– All devices should be implanted for longer than 4–6 weeks.17

– Devices should be implanted in the chest area/pectoral region.21

– The patient should be of normal weight and aspect (no children), specific acute or chronic diseases such as fever or diabetes might increase patient risk.

In case a careful risk-to-benefit analysis favours MRI, the following general recommendations regarding device programming and MR imaging should be considered49

– Devices should be programmed to special MRI mode if available.

– In non-MR conditional pacemakers: D00/V00 with maximized output for pacemaker-dependent patients, otherwise pacing off (e.g. 0D0).

– Tachycardia detection and therapy (ICDs): off.

– 1.5 T MRI should be preferred.18

– Gradient slew rate should not exceed 200 T/m/s.20

– Emergency equipment/external defibrillator as well as a device programmer should be present during the MRI.

– Continuous patient monitoring (electrocardiography/pulse oximetry) during the MRI.

– Dorsal patient position.28

– Imaging landmark near the device (thorax) should be avoided.30

– Local transmit coils should be avoided.

– SAR and scan time should be limited.45

If applicable, these general safety issues should be followed in both conventional pacemakers/ICDs and in MRI conditional devices.

Conclusions

Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiovascular implanted electronic devices has historically been regarded a general contraindication. However, research over the last decade led to the recommendations in the 2013 ESC guidelines, where MRI might be possible if following certain prerequisites.64 Today, a broad selection of device systems is available which are approved for the MRI environment under certain defined conditions, typically also including a dedicated device-specific ‘MRI mode’. Both cardiologists and radiologists should generally aim to strictly follow these manufacturer recommendations, in order to avoid unnecessary risks for the patient. In cases where these recommendations cannot be met, or if a device not labelled MR conditional has been implanted, a careful case-by-case analysis should be performed by the responsible physicians, specifically including alternatively available imaging techniques, thoroughly balancing the patient-specific risks vs. the anticipated diagnostic benefits. If this analysis brings about a decision in favour of MRI, specific general precautions should be taken on the basis of the available preclinical and clinical studies, particularly including attentive patient surveillance during the procedure and carefully implicating convenient options for device reprogramming directly before and after the MRI.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by The University of Würzburg, Germany and the Comprehensive Heart Failure Center, Würzburg, Germany.

Conflict of interest: P.N. and O.R. received speaker honoraria and/or research support from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. O.R. also received speaker honoraria from St. Jude Medical.

References

- 1.Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Finn JP, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG, Ho VB, Jerosch-Herold M, Kramer CM, Manning WJ, Patel M, Pohost GM, Stillman AE, White RD, Woodard PK. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 expert consensus document on cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation task force on expert consensus documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2614–2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalin R, Stanton MS. Current clinical issues for MRI scanning of pacemaker and defibrillator patients. PACE 2005;28:326–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch C, Irnich W, Risse M, Weiler G. Unexpected sudden death of pacemaker patients during or shortly after magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]. XIX Congress of International Academy of Legal Medicine 2003.

- 4.Irnich W, Irnich B, Bartsch C, Stertmann WA, Gufler H, Weiler G. Do we need pacemakers resistant to magnetic resonance imaging? Europace 2005;7:353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alagona P, Jr, Toole JC, Maniscalco BS, Glover MU, Abernathy GT, Prida XE. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with a DDD pacemaker. PACE 1989;12:619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inbar S, Larson J, Burt T, Mafee M, Ezri MD. Case report: nuclear magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with a pacemaker. Am J Med Sci 1993;305:174–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Bolao I, Albaladejo V, Benito A, Alegria E, Zubieta JL. Magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with a dual-chamber pacemaker. Acta Cardiologica. 1998;53:33–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontaine JM, Mohamed FB, Gottlieb C, Callans DJ, Marchlinski FE. Rapid ventricular pacing in a pacemaker patient undergoing magnetic resonance imaging. PACE 1998;21:1336–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achenbach S, Moshage W, Diem B, Bieberle T, Schibgilla V, Bachmann K. Effects of magnetic resonance imaging on cardiac pacemakers and electrodes. Am Heart J 1997;134:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luechinger R, Zeijlemaker VA, Pedersen EM, Mortensen P, Falk E, Duru F, Candinas R, Boesiger P. In vivo heating of pacemaker leads during magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson JM, Tkach J, Phillips M, Baker K, Shellock FG, Rezai AR. Permanent neurological deficit related to magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes for Parkinson's disease: case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:E1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin ET, Coman JA, Shellock FG, Pulling CC, Fair R, Jenkins K. Magnetic resonance imaging and cardiac pacemaker safety at 1.5-tesla. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1315–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommer T, Naehle CP, Yang A, Zeijlemaker V, Hackenbroch M, Schmiedel A, Meyer C, Strach K, Skowatsch D, Vahlhaus C, Litt H, Schild H. Strategy for safe performance of extrathoracic magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 tesla in the presence of cardiac pacemakers in non-pacemaker-dependent patients: a prospective study with 115 examinations. Circulation 2006;114:1285–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiek M, Remp T, Reithmann C, Steinbeck G. Complete loss of ICD programmability after magnetic resonance imaging. PACE 2004;27:1002–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levine GN, Gomes AS, Arai AE, Bluemke DA, Flamm SD, Kanal E, Manning WJ, Martin ET, Smith JM, Wilke N, Shellock FS. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiovascular devices: an American heart association scientific statement from the Committee on Diagnostic and Interventional Cardiac Catheterization, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. Circulation 2007;116:2878–2891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irnich W. Risks to pacemaker patients undergoing magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Europace 2010;12:918–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shellock FG, Tkach JA, Ruggieri PM, Masaryk TJ. Cardiac pacemakers, ICDs, and loop recorder: evaluation of translational attraction using conventional (‘long-bore’) and ‘short-bore’ 1.5- and 3.0-tesla MR systems. J Cardiovasc MR 2003;5:387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luechinger R, Duru F, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P, Candinas R. Force and torque effects of a 1.5-tesla MRI scanner on cardiac pacemakers and ICDs. PACE 2001;24:199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roguin A, Schwitter J, Vahlhaus C, Lombardi M, Brugada J, Vardas P, Auricchio A, Priori S, Sommer T. Magnetic resonance imaging in individuals with cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Europace 2008;10:336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babouri A, Hedjeidj A. In vitro investigation of eddy current effect on pacemaker operation generated by low frequency magnetic field. IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc Annu Conf 2007;2007:5684–5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordbeck P, Weiss I, Ehses P, Ritter O, Warmuth M, Fidler F, Herold V, Jakob PM, Ladd ME, Quick HH, Bauer WR. Measuring RF-induced currents inside implants: impact of device configuration on MRI safety of cardiac pacemaker leads. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61:570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyenhuis J, Park SM, Kamondetdacha R, Amjad A, Shellock F, Rezai A. MRI and implanted medical devices: basic interactions with an emphasis on heating. IEEE Trans Device Mater Reliab. 2005;5:467–480. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tandri H, Zviman MM, Wedan SR, Lloyd T, Berger RD, Halperin H. Determinants of gradient field-induced current in a pacemaker lead system in a magnetic resonance imaging environment. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nordbeck P, Fidler F, Weiss I, Warmuth M, Friedrich MT, Ehses P, Geistert W, Ritter O, Jakob PM, Ladd ME, Quick HH, Bauer WR. Spatial distribution of RF-induced e-fields and implant heating in MRI. Magn Reson Med 2008;60:312–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calcagnini G, Triventi M, Censi F, Mattei E, Bartolini P, Kainz W, Bassen HI. In vitro investigation of pacemaker lead heating induced by magnetic resonance imaging: role of implant geometry. JMRI 2008;28:879–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattei E, Triventi M, Calcagnini G, Censi F, Kainz W, Mendoza G, Bassen HI, Bartolini P. Complexity of MRI induced heating on metallic leads: experimental measurements of 374 configurations. Biomed Eng Online. 2008;7:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SM, Kamondetdacha R, Nyenhuis JA. Calculation of MRI-induced heating of an implanted medical lead wire with an electric field transfer function. JMRI 2007;26:1278–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nordbeck P, Fidler F, Friedrich MT, Weiss I, Warmuth M, Gensler D, Herold V, Geistert W, Jakob PM, Ertl G, Ritter O, Ladd ME, Bauer WR, Quick HH. Reducing RF-related heating of cardiac pacemaker leads in MRI: implementation and experimental verification of practical design changes. Magn Reson Med 2012;68:1963–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langman DA, Goldberg IB, Finn JP, Ennis DB. Pacemaker lead tip heating in abandoned and pacemaker-attached leads at 1.5 tesla MRI. JMRI 2011;33:426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordbeck P, Ritter O, Weiss I, Warmuth M, Gensler D, Burkard N, Herold V, Jakob PM, Ertl G, Ladd ME, Quick HH, Bauer WR. Impact of imaging landmark on the risk of MRI-related heating near implanted medical devices like cardiac pacemaker leads. Magn Reson Med 2011;65:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher JD. MRI: safety in patients with pacemakers or defibrillators: is it prime time yet? PACE 2005;28:263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine PA. Industry viewpoint: St. Jude medical: pacemakers, ICDs and MRI. PACE 2005;28:266–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton MS. Industry viewpoint: Medtronic: pacemakers, ICDs, and MRI. PACE 2005;28:265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith JM. Industry viewpoint: Guidant: pacemakers, ICDs, and MRI. PACE 2005;28:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gimbel JR, Johnson D, Levine PA, Wilkoff BL. Safe performance of magnetic resonance imaging on five patients with permanent cardiac pacemakers. PACE 1996;19:913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sommer T, Lauck G, Schimpf R, von Smekal A, Wolke S, Block W, Gieseke J, Schneider C, Funke HD, Schild H. MRI in patients with cardiac pacemakers: in vitro and in vivo evaluation at 0.5 tesla. RoFo 1998;168:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommer T, Vahlhaus C, Lauck G, von Smekal A, Reinke M, Hofer U, Block W, Traber F, Schneider C, Gieseke J, Jung W, Schild H. MR imaging and cardiac pacemakers: in-vitro evaluation and in-vivo studies in 51 patients at 0.5 t. Radiology. 2000;215:869–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vahlhaus C, Sommer T, Lewalter T, Schimpf R, Schumacher B, Jung W, Luderitz B. Interference with cardiac pacemakers by magnetic resonance imaging: are there irreversible changes at 0.5 tesla? PACE 2001;24:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strach K, Naehle CP, Muhlsteffen A, Hinz M, Bernstein A, Thomas D, Linhart M, Meyer C, Bitaraf S, Schild H, Sommer T. Low-field magnetic resonance imaging: increased safety for pacemaker patients? Europace. 2010;12:952–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gimbel JR, Bailey SM, Tchou PJ, Ruggieri PM, Wilkoff BL. Strategies for the safe magnetic resonance imaging of pacemaker-dependent patients. PACE 2005;28:1041–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nazarian S, Roguin A, Zviman MM, Lardo AC, Dickfeld TL, Calkins H, Weiss RG, Berger RD, Bluemke DA, Halperin HR. Clinical utility and safety of a protocol for noncardiac and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of patients with permanent pacemakers and implantable-cardioverter defibrillators at 1.5 tesla. Circulation 2006;114:1277–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mollerus M, Albin G, Lipinski M, Lucca J. Cardiac biomarkers in patients with permanent pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators undergoing a MRI scan. PACE 2008;31:1241–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Naehle CP, Zeijlemaker V, Thomas D, Meyer C, Strach K, Fimmers R, Schild H, Sommer T. Evaluation of cumulative effects of MR imaging on pacemaker systems at 1.5 tesla. PACE 2009;32:1526–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mollerus M, Albin G, Lipinski M, Lucca J. Ectopy in patients with permanent pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators undergoing a MRI scan. PACE 2009;32:772–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mollerus ME, Albin G, Lipinski M, Lucca J. Magnetic resonance imaging of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators without specific absorption rate restrictions. Europace 2010;12:947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halshtok O, Goitein O, Abu Sham'a R, Granit H, Glikson M, Konen E. Pacemakers and magnetic resonance imaging: no longer an absolute contraindication when scanned correctly. IMAJ 2010;12:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burke PT, Ghanbari H, Alexander PB, Shaw MK, Daccarett M, Machado C. A protocol for patients with cardiovascular implantable devices undergoing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): should defibrillation threshold testing be performed post-(MRI). J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2010;28:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buendia F, Sanchez-Gomez JM, Sancho-Tello MJ, Olague J, Osca J, Cano O, Arnau MA, Igual B. Nuclear magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac pacing devices. Revista Espanola de Cardiologia 2010;63:735–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nazarian S, Hansford R, Roguin A, Goldsher D, Zviman MM, Lardo AC, Caffo BS, Frick KD, Kraut MA, Kamel IR, Calkins H, Berger RD, Bluemke DA, Halperin HR. A prospective evaluation of a protocol for magnetic resonance imaging of patients with implanted cardiac devices. An Int Med 2011;155:415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen JD, Costa HS, Russo RJ. Determining the risks of magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5 tesla for patients with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Am J Cardiol 2012;110:1631–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boilson BA, Wokhlu A, Acker NG, Felmlee JP, Watson RE, Jr, Julsrud PR, Friedman PA, Cha YM, Rea RF, Hayes DL, Shen WK. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging in patients with permanent pacemakers: a collaborative clinical approach. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol 2012;33:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Del Ojo JL, Moya F, Villalba J, Sanz O, Pavon R, Garcia D, Pastor L. Is magnetic resonance imaging safe in cardiac pacemaker recipients? PACE 2005;28:274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naehle CP, Meyer C, Thomas D, Remerie S, Krautmacher C, Litt H, Luechinger R, Fimmers R, Schild H, Sommer T. Safety of brain 3-t MR imaging with transmit-receive head coil in patients with cardiac pacemakers: pilot prospective study with 51 examinations. Radiology 2008;249:991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gimbel JR. Magnetic resonance imaging of implantable cardiac rhythm devices at 3.0 tesla. PACE 2008;31:795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coman JA, Sandler DA, Thomas JR. Implantable cardiac defibrillator interactions with magnetic resonance imaging at 1,5 tesla. Am Heart Assoc 2004;43:138A. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naehle CP, Strach K, Thomas D, Meyer C, Linhart M, Bitaraf S, Litt H, Schwab JO, Schild H, Sommer T. Magnetic resonance imaging at 1.5-t in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pulver AF, Puchalski MD, Bradley DJ, Minich LL, Su JT, Saarel EV, Whitaker P, Etheridge SP. Safety and imaging quality of MRI in pediatric and adult congenital heart disease patients with pacemakers. PACE 2009;32:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gimbel JR, Kanal E, Schwartz KM, Wilkoff BL. Outcome of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in selected patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs). PACE 2005;28:270–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naehle CP, Kreuz J, Strach K, Schwab JO, Pingel S, Luechinger R, Fimmers R, Schild H, Thomas D. Safety, feasibility, and diagnostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with cardiac pacemakers and implantable cardioverters/defibrillators at 1.5 t. Am Heart J 2011;161:1096–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mesubi O, Ahmad G, Jeudy J, Jimenez A, Kuk R, Saliaris A, See V, Shorofsky S, Dickfeld T. Impact of icd artifact burden on late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MR imaging in patients undergoing ventricular tachycardia ablation. PACE 2014;37:1274–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Graaf AW, Bhagirath P, Gotte MJ. MRI and cardiac implantable electronic devices: current status and required safety conditions. Netherlands Heart J 2014;22:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gray RW, Bibens WT, Shellock FG. Simple design changes to wires to substantially reduce MRI-induced heating at 1.5 t: implications for implanted leads. Magn Reson Imaging 2005;23:887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilkoff BL, Bello D, Taborsky M, Vymazal J, Kanal E, Heuer H, Hecking K, Johnson WB, Young W, Ramza B, Akhtar N, Kuepper B, Hunold P, Luechinger R, Puererfellner H, Duru F, Gotte MJ, Sutton R, Sommer T. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with a pacemaker system designed for the magnetic resonance environment. Heart Rhythm 2011;8:65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, Bordachar P, Boriani G, Breithardt OA, Cleland J, Deharo JC, Delgado V, Elliott PM, Gorenek B, Israel CW, Leclercq C, Linde C, Mont L, Padeletti L, Sutton R, Vardas PE, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Badano LP, Aliyev F, Bansch D, Bsata W, Buser P, Charron P, Daubert JC, Dobreanu D, Faerestrand S, Le Heuzey JY, Mavrakis H, McDonagh T, Merino JL, Nawar MM, Nielsen JC, Pieske B, Poposka L, Ruschitzka F, Van Gelder IC, Wilson CM. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Eur Heart J 2013;34:2281–2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]