Abstract

Skilled motor behavior emerges from interactions between efferent neural pathways that induce muscle contraction and feedback systems that report and refine movement. Two broad classes of feedback projections modify motor output, one from the periphery and a second that originates within the central nervous system. The mechanisms through which these pathways influence movement remain poorly understood, however. Here we discuss recent studies that delineate spinal circuitry that binds external and internal feedback pathways to forelimb motor behavior. A spinal presynaptic inhibitory circuit regulates the strength of external feedback, promoting limb stability during goal-directed reaching. A distinct excitatory propriospinal circuit conveys copies of motor commands to the cerebellum, establishing an internal feedback loop that rapidly modulates forelimb motor output. The behavioral consequences of manipulating these two circuits reveal distinct controls on motor performance, and provide an initial insight into feedback strategies that underlie skilled forelimb movement.

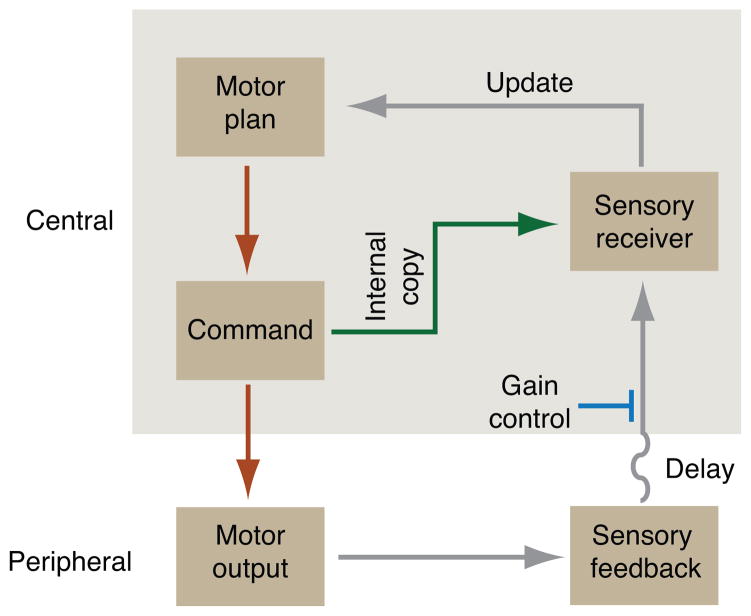

Goal-directed movements have their basis in neural circuits that channel central commands towards the periphery, translating motor plan into action. The fidelity of motor output requires more than just neural commands, however. Feedback pathways play a critical role in shaping movement, reducing discrepancies between intent and outcome. Defining the organization of such feedback pathways, and how they engage motor circuits, represent central challenges to understanding the neural basis of movement. In this review we focus on two classes of feedback pathway that impact motor output: one that originates in the periphery and conveys external sensory information, and another that originates within the central nervous system and mediates internal feedback for rapid motor updating (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Internal and external feedback motor pathways. During limb movement, motor plans are translated into commands by supraspinal and spinal pathways, eliciting motor output in the form of muscle contraction. Movement generates sensory feedback, including proprioceptive feedback from muscles, which conveys information about motor outcome to central sensory recipient centers. Temporal delays in sensory feedback imply a need for: a constraint on sensory feedback gain (blue) to maintain stability; and a more rapid mechanism of internal copy feedback (green) for online updating and correction of movement. Adapted from (Azim 2014).

The immediacy of the link between spinal circuitry and muscle contraction has provided an accessible and interpretable experimental system for probing the influence of external and internal feedback pathways on motor output (Baldissera et al. 1981; Jankowska 2001; Pierrot-Deseilligny and Burke 2012; Miri et al. 2013). Among the wide range of mammalian motor behaviors, the control of skilled forelimb movement has come to occupy a central role in studies to define the logic of motor control (Iwaniuk and Whishaw 2000; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008; Alstermark and Isa 2012; Azim and Alstermark 2015). As such, spinal circuits that govern forelimb movement offer an informative substrate for exploring feedback systems and their influence on skilled motor performance.

Problems created by delays in sensory feedback

Goal-directed reaching movements are characterized by a remarkable regularity. When reaching to a target, limb trajectory and velocity profiles are consistent from trial-to-trial, despite considerable variation in the patterns of joint movement (Morasso 1981). One potential means of achieving such reproducibility in behavior involves the generation of feed-forward motor commands that take into account the limb’s biomechanical response characteristics in driving muscle contraction (Haith and Krakauer 2013). Yet motor command pathways are beset by noise and variability (Harris and Wolpert 1998; Jones et al. 2002; Xu-Wilson et al. 2009; Haith and Krakauer 2013), implying that feedback information is also used to signal error and correct motor output. Proprioception provides one critical source of feedback for motor updating, conveying information both about the state of muscle contraction and the position of the limb in space (Rothwell et al. 1982; Ghez et al. 1995; Gordon et al. 1995). Nevertheless, proprioceptive pathways, and peripheral feedback circuits more generally, take some time to convey signals to relevant sensory recipient centers. These temporal delays arise in part from the mechanics of muscle contraction and spindle activation and the lag incurred in axonal conduction (Wolpert and Miall 1996), and they raise two challenges for motor control (Fig. 1).

The first challenge, documented extensively in the realm of engineering control theory, is that feedback delays destabilize output and result in oscillations and a degradation in performance (Kawato and Gomi 1992; Wolpert and Miall 1996; Ali et al. 1998). One effective means of avoiding motor instability is to limit the impact of sensory feedback on motor output through reduced feedback gain (Stein and Oğuztöreli 1976). At the neuronal level, an inhibitory gain control system could effectively ensure that delays in the provision of peripheral feedback signals do not destabilize the limb during movement (Fig. 1). The question that emerges then is whether the spinal cord contains a neural mechanism dedicated to the adjustment of proprioceptive sensory gain during the execution of movement, and if so, what is the functional consequence of its removal?

The second challenge is that delays in feedback limit the rapidity with which motor commands can be refined. During reaching, motor output is continually and rapidly modified as the limb extends to its target (Prablanc and Martin 1992; Messier and Kalaska 1999; Scott 2004), implying the existence of fast feedback pathways that enable online correction of limb movement. One theoretical basis for a rapid source of feedback is the copying of motor commands as they descend to spinal motor centers, and the routing of these copies to the cerebellum for prediction of the sensory outcome of movement. In essence, the cerebellum has been argued to use internal copy signals to implement a forward model of the limb (Wolpert and Miall 1996; Desmurget and Grafton 2000; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008) (Fig. 1). In principle, forward model-based predictions offer advantages for motor control. If an incorrect motor command is generated, motor output can be corrected without waiting for sensory information (Shadmehr et al. 2010). Moreover, estimates of the current state of limb position can be made more precise, helping to modify movements in ways beyond the capacity of simple sensory-motor reflex arcs (Todorov and Jordan 2002; Scott 2004; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008; Azim and Alstermark 2015).

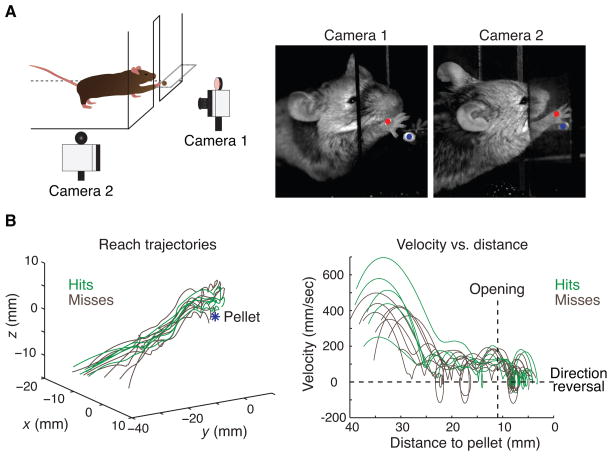

Nevertheless, the neural implementation and behavioral contributions of sensory gain control and internal copy mechanisms have remained a matter of conjecture, in the absence of effective ways of defining their circuitry and evaluating motor performance after manipulating the output of relevant neurons. Traditional experimental methods such as pharmacological silencing and electrical stimulation do not permit selectivity in manipulating spinal circuits for gain control and internal feedback, making it difficult to resolve how their organization confers function. Combining the availability of genetically modified mice with the molecular delineation of neuronal subtype provides a potential strategy for overcoming these limitations, in that they permit the isolation and perturbation of discrete spinal circuits implicated in feedback regulation. Encouragingly, implementation of a detailed three-dimensional quantification of reaching kinematics has revealed the highly stereotyped nature of forelimb movements, even in mice (Whishaw 1996; Azim et al. 2014), providing a sensitive method with which to evaluate the functional consequences of spinal circuit manipulation (Fig. 2). Below, we describe how the use of high-resolution behavioral assays, combined with molecular-genetic manipulations and electrophysiological and modeling approaches, has permitted the functional dissection of some of the spinal circuits implicated in external and internal feedback control (Azim et al. 2014; Fink et al. 2014).

Figure 2.

Reaching kinematics in mice. (A) Mice were trained to reach for a food pellet through an opening in a transparent box. High-speed, high-resolution video capture and automated tracking of an infrared-reflective marker attached to the right paw were used to reconstruct three-dimensional reaching kinematics. (B) Successful (defined as retrieval of the food pellet) and unsuccessful reaches are highly stereotyped in wildtype mice. Trajectories of successful (hits, green traces) and unsuccessful (misses, brown traces) trials from a representative mouse are shown on the left. Paw velocity as a function of distance to the pellet is shown on the right. The transition from the reach phase to the late grab phase of movement is delineated by the box opening (vertical dashes). Velocity crossings of zero (horizontal dashes) indicate paw direction reversals. Adapted from (Azim et al. 2014).

Achieving smooth movement through sensory gain control

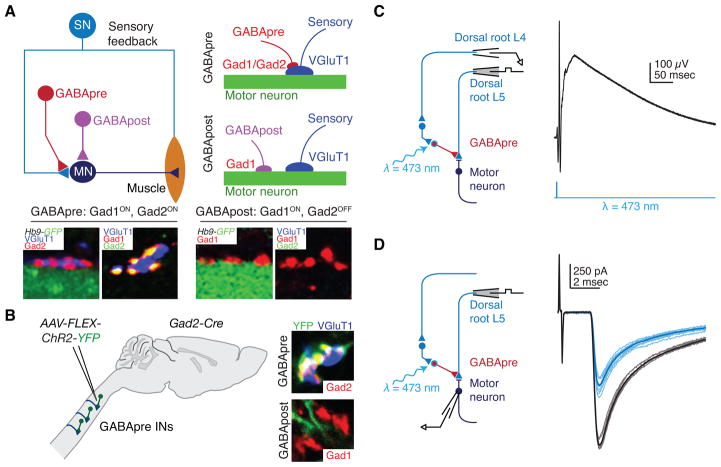

From first principles, a simple sensory–motor reflex arc subject to high feedback gain has a tendency to oscillate (Stein and Oğuztöreli 1976). Modeling of this sort points to the existence of microcircuits that control the gain of proprioceptive feedback (Fig. 1). The central terminals of primary somatosensory neurons are studded with GABAergic axo-axonic synapses that represent presynaptic inhibitory contacts (Gray 1962; Conradi 1969; Watson and Bazzaz 2001; Betley et al. 2009), and this unusual arrangement has been studied most extensively at synapses between proprioceptive sensory axons and spinal motor neurons (Schmidt 1971; Rudomin and Schmidt 1999; Rudomin 2009) (Fig. 3A). A long-recognized feature of presynaptic inhibition is its ability to reduce the excitability of motor neurons without postsynaptic inhibition of the motor neuron itself (Frank and Fuortes 1957; Eccles et al. 1961). The neurons that mediate presynaptic inhibition (which we term GABApre neurons) exert their influence at sensory terminals by reducing the probability of synaptic vesicle release (Kuno 1964; Fink et al. 2014). Moreover, theoretical studies lend support to the idea that presynaptic inhibition reduces gain at sensory-motor synapses (Capaday and Stein 1987; Capaday and Stein 1989).

Figure 3.

Gad2-expressing neurons mediate presynaptic inhibition. (A) Proprioceptive sensory neurons (SN) convey sensory feedback signals from muscle to motor neurons (MN). Presynaptic inhibitory (GABApre) neurons contact sensory afferent terminals, while postsynaptic inhibitory (GABApost) neurons contact motor neurons directly. GABApre neurons express Gad2 (top schematic and left two images; far left: red Gad2ON contacts on blue VGluT1+ sensory afferent terminal, adjacent green GFP+ motor neuron labeled in Hb9-GFP mice). GABApost neurons express Gad1 (bottom schematic and right two images; second from right: red Gad1ON contacts adjacent green GFP+ motor neuron). While GABApre neurons express both Gad1 and Gad2 (second image from left: yellow Gad1ON/Gad2ON puncta adjacent VGluT1+ sensory terminal), GABApost neurons express Gad1 alone (far right image: red Gad1ON/Gad2OFF puncta). (B) Injection of Cre-dependent virus (AAV-FLEX-ChR2-YFP) into cervical cord of adult Gad2-Cre mice labels GABApre neurons (top, YFP+, Gad2+ contact adjacent VGluT1+ sensory terminal) and not GABApost neurons (bottom, YFP-negative red puncta). Viral injection marks ~80% of GABApre and ~1% of GABApost boutons. (C) After AAV-FLEX-ChR2-YFP injection in lumbar spinal cord of neonatal Gad2-Cre mice, recordings in isolated spinal cord from sensory afferents (dorsal root L4, extracellular) reveal primary afferent depolarization and, (D) recordings from motor neurons (whole cell patch clamp) reveal suppression of monosynaptic sensory-evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents after photostimulation (black, control; blue, 473 nm wavelength (λ) photostimulation). At early ages Gad2 is also expressed in GABApost boutons; therefore, all behavioral experiments were performed after viral injection in adult mice, when Gad2 expression is specific for GABApre neurons (B) (see (Fink et al. 2014) for details). Adapted from (Betley et al. 2009; Fink et al. 2014).

How can the behavioral relevance of GABApre neurons best be discerned? Both pre- and post-synaptic inhibitory neurons use GABA as neurotransmitter (Betley et al. 2009), so disentangling the impact of these forms of inhibition through receptor pharmacology has not been possible. Nevertheless, these two inhibitory systems can be distinguished by their molecular provenance and postmitotic identity. GABApre neurons are derived from dorsal dI4 interneurons and express the transcription factor Ptf1a, whereas postsynaptic inhibitory (GABApost) neurons, which are derived from V1 and V2b domains, can be defined respectively, by the transcription factors En1 and Gata2/3 (Betley et al. 2009). Both GABApre and GABApost interneurons express the major GABA synthetic enzyme Gad1, whereas only GABApre neurons express a second, more specialized, synthetic enzyme Gad2 (Hughes et al. 2005; Betley et al. 2009) (Fig. 3A). The use of Gad2 as a marker has shown that as they develop, GABApre axons exhibit a stringent specificity for sensory afferent terminals, and withdraw from the ventral spinal cord when sensory axons are absent (Betley et al. 2009; Ashrafi et al. 2014). Thus GABApre neurons represent a molecularly defined inhibitory interneuron population whose anatomical organization suggests a potential role in constraining sensory feedback.

Appreciation of the selectivity of Gad2 expression by GABApre neurons has permitted genetic manipulations that aim to evaluate the contribution of presynaptic inhibition to forelimb movement (Fink et al. 2014). To resolve whether Gad2-expressing neurons are functional mediators of presynaptic inhibition, transgenic mice bearing Cre recombinase expression under Gad2 control (Gad2-Cre mice) (Taniguchi et al. 2011) were injected with a virus expressing Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin (ChR2) (Fig. 3B). Photoactivation of ChR2+, Gad2+ neurons elicited the two canonical features of presynaptic inhibition: a depolarization of primary afferent fibers (primary afferent depolarization, ‘PAD’) (Fig. 3C), and a reduction in the probability of sensory transmitter release that reduces the amplitude of postsynaptic sensory-evoked currents (Fig. 3D). These physiological findings implicate Gad2+ neurons as mediators of presynaptic inhibition at spinal sensory-motor synapses.

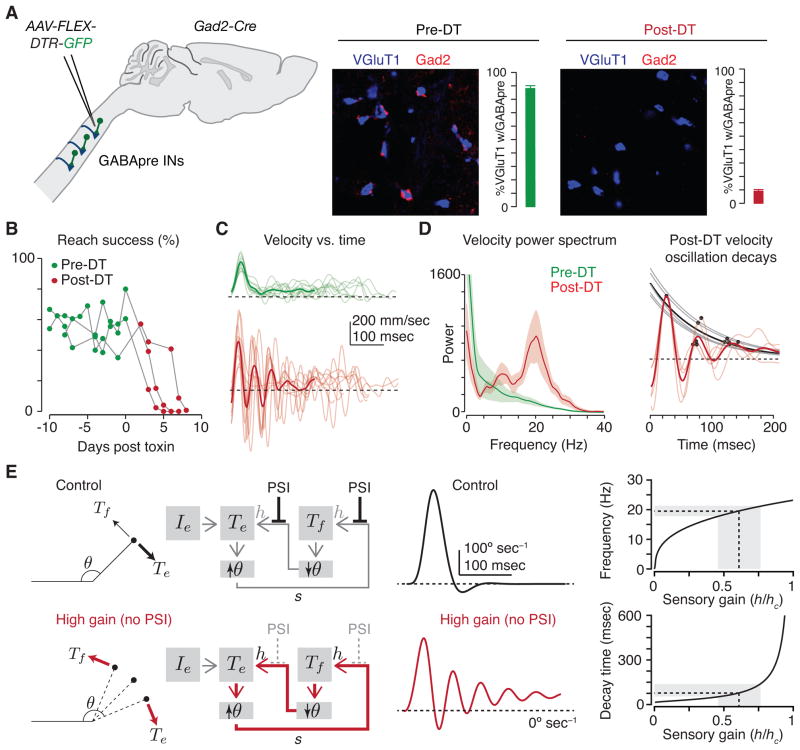

The behavioral contribution of GABApre neurons to forelimb movement has been explored through the use of a conditional virus that expresses a diphtheria toxin receptor construct under Gad2 control, and thus selectively in GABApre neurons in adult cervical spinal cord. Administration of diphtheria toxin led to the near-complete absence of GABApre boutons in contact with sensory terminals, without reducing the number of postsynaptic inhibitory boutons (Fig. 4A). Strikingly, analysis of goal-directed reaching behavior revealed that GABApre neuronal ablation produces pronounced limb oscillations as the forepaw approaches the target, as well as a severe degradation in overall reach success (Fig. 4B,C). Moreover, the frequency and decay times of these oscillatory movements were remarkably consistent across reaches and amongst GABApre deficient mice (Fig. 4D). A model of the limb as a damped harmonic oscillator driven by feedback at high gain captures many of the core features of this stereotyped motor instability (Fig. 4E), supporting the view that a major role of presynaptic inhibition is to regulate the gain of proprioceptive feedback. Thus, for this set of inhibitory interneurons, a convergence of physiology, behavior and theory reveal that, during goal-directed reach tasks, GABApre neurons serve as a sensory gain control system for limb stability.

Figure 4.

GABApre neuron ablation results in forelimb oscillation during reaching. (A) Cervical GABApre interneurons (INs) were targeted for acute ablation via injection of a conditional virus expressing a diphtheria toxin receptor-GFP fusion (AAV-FLEX-DTR-GFP) in cervical cord of adult Gad2-Cre mice. Before diphtheria toxin (DT) administration (left), ~90% of VGluT1+ sensory afferent terminals (blue) are contacted by Gad2+ GABApre boutons (red). Following DT administration (right), Gad2+ GABApre boutons contact <10% of sensory afferent terminals. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (B) GABApre ablation severely affects reach success; before (green) and after (red) DT administration for three Gad2-Cre mice. (C) Paw velocity as a function of time for a representative mouse (thin lines, individual reaches; bold lines, mean) before (green) and after (red) DT administration reveals severe oscillations after GABApre ablation. (D) Average power spectra (left, bold lines, mean across mice; shading, s.e.m.) of pre-DT (green) and post-DT (red) reaches indicate a narrow peak in oscillation frequency focused at ~20 Hz after ablation. Alignment of individual reaches to the point of maximal reach velocity (right) reveals consistent oscillatory decay in individual mice (faint red lines) and averaged across mice (bold red line). Fitting single exponential functions to the first three oscillatory peaks (gray dots and faint gray lines, individual mice; black line, mean) reveals a decay time of ~77 msec across mice. (E) A simplified model of a joint with sensory feedback controlled by a flexor (Tf) and extensor (Te) torque and defined by joint angle θ (left panels). Sensory feedback (s) depends on joint angle and normally permits smooth joint extension (gray arrows, black control trace) in the presence of external extensor drive (Ie). In the absence of presynaptic inhibition (PSI), simulated by imposing high sensory gain (h), sensory feedback triggers oscillation (red arrows and red high gain trace). Oscillation frequency and decay time change little across a wide range of gain values in the model (right plots), providing a possible explanation for why frequency and decay time are so consistent across mice (D). Gray shading indicates the range of experimentally observed peak oscillation frequency and decay times in post-DT Gad2-Cre mice, as well as the corresponding range of normalized gain values. Adapted from (Fink et al. 2014).

These findings suggest cogent reasons for constructing a specialized presynaptic inhibitory circuit, in addition to the more prevalent postsynaptic inhibitory constraints on motor output. One obvious attribute of presynaptic inhibition is its target specificity – this axo-axonic organization provides an anatomical substrate for selective regulation of a single excitatory input to motor neurons, whereas postsynaptic inhibition inevitably exerts a more general impact on the excitability of motor neurons triggered by diverse inputs. In addition, presynaptic inhibition provides a means of scaling the gain of sensory feedback to match the intensity of sensory input. Proprioceptive afferents are known to fire at frequencies spanning three orders of magnitude in the course of a normal motor task (Prochazka 1999), suggesting the need to achieve a compressed dynamic range that can be read out more effectively by central motor circuits (Laughlin 1994; Brenner et al. 2000). One crucial basis for this gain scaling strategy is the fact that proprioceptive afferents also provide excitatory drive to GABApre neurons (Eccles et al. 1961; Eccles et al. 1962). Thus enhanced sensory activity will concomitantly increase GABApre-mediated inhibition, providing an effective circuit-based scheme for sensory gain scaling.

The need for presynaptic inhibition to limit the dynamic range of sensory afferent firing also provides a plausible explanation for the selectivity of Gad2 expression in presynaptic inhibitory neurons, in that Gad2 enzymatic activity within inhibitory boutons has been shown to sustain GABA release at high firing rates (Tian et al. 1999). Together, these anatomical and molecular features would seem to equip GABApre neurons with the ability to rescale sensory input in a dynamic and adaptive manner, an essential constraint given the wide range of sensory firing rates observed in vivo.

Despite these advances, many features of the physiology of spinal presynaptic inhibition still lack molecular or circuit explanations. Work in primates and cats has begun to define the descending circuitry responsible for recruitment of GABApre neurons, but relatively little is known about the physiological triggers for this form of inhibition during limb movement. Studies in monkey have shown that supraspinal systems elicit presynaptic inhibition of cutaneous feedback during voluntary movement of the wrist (Seki et al. 2003), and human studies suggest that descending pathways recruit presynaptic inhibition of proprioceptive afferents on a muscle-by-muscle basis during voluntary contraction (Hultborn et al. 1987). Thus supraspinal systems are likely to engage presynaptic inhibition dynamically, even at the level of an individual motor neuron pool, functional features that imply a highly organized pattern of descending control (Rudomin et al. 1986).

At a local level, presynaptic inhibition exhibits a finely-grained precision in targeting. Anatomical evidence suggests that group Ib but not group Ia sensory boutons in the region of Clarke’s column receive axo-axonic contacts (Walmsley et al. 1987). And even at the level of an individual sensory fiber, presynaptic inhibition is likely to act differentially on single axon collaterals (Lomelí et al. 1998). Together, these findings imply a richly endowed organization of presynaptic inhibitory interneurons themselves and of the pathways that recruit them. They also suggest a diversity of GABApre neuronal subtypes and their connections, mirroring the functional heterogeneity of the afferent fibers they control.

Internal feedback for rapid motor updating

Animals can refine forelimb movements with rapidity, despite incumbent delays in sensory feedback. Internally-directed copies of motor commands might provide a faster source of feedback information for motor updating (Wolpert and Miall 1996; Desmurget and Grafton 2000; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008; Azim and Alstermark 2015) (Fig. 1). Yet obtaining experimental evidence that internal feedback does actually influence forelimb movement has been frustratingly hard, in part because of the difficulty of perturbing putative internal copy circuits without simultaneously affecting motor output. Genetic interventions in mice could permit more incisive access to internal copy circuits and their encoded function.

One class of spinal interneurons, cervical propriospinal neurons (PNs), has been implicated in the control of forelimb movement (Alstermark and Isa 2012). Lesion studies in cat suggest a role for PNs in goal-directed reaching and in the rapid updating of limb motor output after sudden changes in target location (Alstermark et al. 1981b; Alstermark and Lundberg 1992). Moreover, recent viral silencing experiments have provided evidence that PNs contribute to both reaching and grasping movements in primates (Kinoshita et al. 2012).

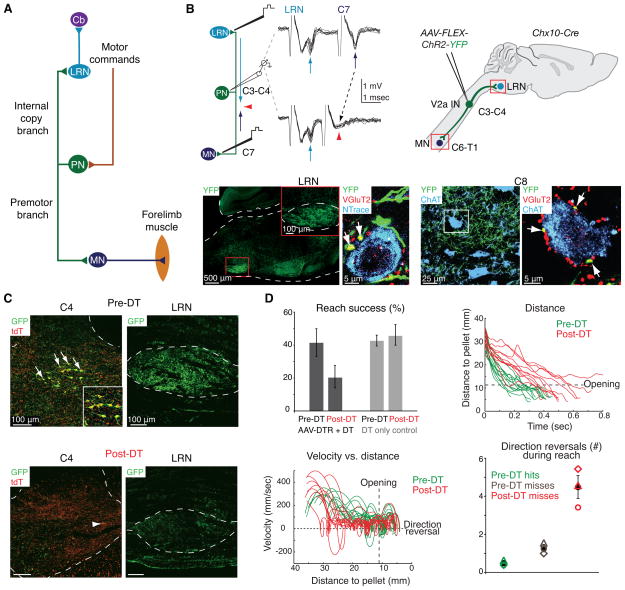

Two anatomical features implicate PNs as mediators of internal copies of forelimb motor commands. They receive input from supraspinal descending pathways (Illert et al. 1978; Illert et al. 1981), and thus serve as potential effectors of motor commands devoted to forelimb movement. In addition, PNs are characterized by a bifurcated output: one axonal branch projects to the cervical motor neurons that control forelimb muscles (Alstermark et al. 1990), while the other projects rostrally to the lateral reticular nucleus (LRN) (Alstermark et al. 1981a), a major pre-cerebellar input (Brodal 1949; Arshavsky et al. 1978a; Alstermark and Ekerot 2013) (Fig. 5A). The duality in axonal projection and output constitutes an anatomically direct means of conveying internal copies of pre-motor signals, and raises the question of whether PN internal feedback has any relevance to the control of forelimb movement.

Figure 5.

V2a PN ablation disrupts reaching movements. (A) PNs receive input from descending motor command pathways. PN axons bifurcate to innervate forelimb motor neurons (MN, premotor branch) and the lateral reticular nucleus (LRN, internal copy branch), which projects to the cerebellum (Cb). (B) In vivo extracellular recording in mouse cervical spinal cord while electrically stimulating LRN and C7 ventral horn reveals neurons fired antidromically from both stimulation sites (top left, arrows). Spike collision (red arrowheads) shows that the identified neuron projects to both targets, confirming the existence of PNs in mice. Injection of Cre-dependent virus (AAV-FLEX-ChR2-YFP) into cervical cord of adult Chx10-Cre mice labels V2a interneurons (IN) selectively (top right). YFP+ V2a INs project to the LRN (bottom left), where they form VGluT2+ excitatory synaptic contacts (red, arrows) onto LRN neurons (blue). Similarly, forelimb motor neurons in C8 (bottom right, blue) receive VGluT2+ (red), YFP+ contacts (arrows). (C) Cervical V2a INs were targeted for acute ablation via injection of a conditional virus expressing a diphtheria toxin receptor-GFP fusion (AAV-FLEX-DTR-GFP) in cervical cord of adult Chx10-Cre mice (top left, arrows, V2a INs genetically labeled by tdT in red; top right, GFP+ projections to the LRN). Diphtheria toxin (DT) administration ablates ~85% of V2a INs (bottom left, arrowhead indicates spared neuron), and eliminates GFP+ PN projections to the LRN (bottom right). (D) V2a IN elimination reduces reaching success (top left), and increases movement duration (top right) and the number of forelimb direction reversals (bottom left and right) during the reaching phase of movement (before the box opening). Shapes in bottom right plot represent individual mice. Error bars indicate s.e.m. Locomotion and digit abduction were not affected by V2a IN elimination (not shown). Adapted from (Azim et al. 2014).

PNs are present in mice, as revealed by in vivo electrophysiology and viral tracing studies, and one prominent set of excitatory PNs expresses the transcription factor Chx10, marking them as V2a neurons, one of the cardinal interneuron classes implicated in spinal motor control (Azim et al. 2014) (Fig. 5B). The use of a Cre-dependent virus to express diphtheria toxin receptor in Chx10-Cre mice has shown that toxin-mediated ablation of cervical V2a interneurons (Fig. 5C) elicits a severe reach-specific dysmetria (Fig. 5D), without major impact on digit abduction or locomotor control. The similarity in behavioral deficit observed after PN disruption in mouse, cat and monkey (Alstermark and Isa 2012; Kinoshita et al. 2012; Azim et al. 2014) supports the view that PNs have evolved to regulate mammalian reaching behavior.

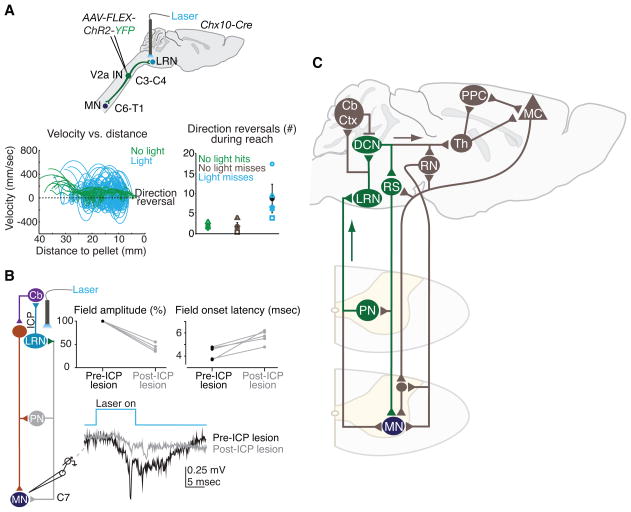

Nevertheless, elimination of PNs abolishes both motor command and internal copy, and thus does not resolve whether the internal copy pathway alone has any impact on forelimb movement. This issue has been addressed by expressing ChR2 in cervical V2a neurons in Chx10-Cre mice, with the aim of gaining selective access to the ascending PN branch (Fig. 6A). Under these conditions, focal photostimulation of PN terminals within the LRN activated the internally-directed PN-LRN pathway without affecting PN pre-motor output. Strikingly, selective PN terminal photostimulation produced a severe disruption in reaching kinematics, eliciting a large increase in the incidence of paw direction reversals (Fig. 6A) without affecting digit movements. The selectivity of these behavioral effects suggests that the PN internal copy pathway is dedicated to the modulation of reaching.

Figure 6.

PN internal copy activation modulates forelimb movement through a rapid cerebellar-motor loop. (A) ChR2 was expressed in cervical V2a INs via injection of conditional virus (AAV-FLEX-ChR2-YFP) in cervical cord of adult Chx10-Cre mice. Photostimulation of ChR2+ PN terminals in the LRN activates the PN-LRN pathway selectively, without eliciting antidromic action potentials (not shown). Photostimulation disrupts reaching movements (blue traces), producing a large increase in the incidence of paw direction reversals and variability in velocity and acceleration during reaching, without affecting digit abduction (not shown). Shapes in right plot represent individual mice. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (B) Motor field potential recordings in cervical spinal segments, as well as intracellular motor neuron recordings (not shown), reveal rapid activation of forelimb motor neurons (earliest activation ~4–5 msec from light onset). Severing the inferior cerebellar peduncles (ICP), which contain the projections from the LRN to the cerebellum, reduces the amplitude of motor field potentials by up to 65% and eliminates the fastest motor field onsets, implicating a rapid cerebellar-motor feedback pathway. (C) A putative subcortical PN-LRN feedback loop (green) recruits deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN), which excite reticulospinal (RS) projections to motor neurons (MN). Longer loops (brown) might engage cerebellar cortex (Cb Ctx), rubrospinal neurons (RN) and cortical pathways in posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and motor cortex (MC) via thalamus (Th) (see text). (A,B) adapted from (Azim et al. 2014).

These findings have provided functional evidence that imposed activation of a spinal internal copy pathway perturbs the fidelity of forelimb motor output. Moreover, in vivo recordings revealed that activation of the PN-LRN pathway excites forelimb motor neurons in as little as ~4–5 msec (Fig. 6B). These short latency motor responses are substantially diminished by severing LRN projections to the cerebellum (Fig. 6B), implicating a fast cerebellar-motor loop in modulating forelimb motor neuron activity (Fig. 6C). Viewed in the context of reaching movements that typically last hundreds of milliseconds, the rapidity of these regulatory actions suggests that the PN-LRN circuit can adjust motor output continuously during an individual reach.

To date, PN circuit manipulations have provided functional support for the idea that internal copy pathways directed to the cerebellum contribute to forelimb motor refinement (Alstermark and Lundberg 1992; Alstermark and Isa 2012; Azim et al. 2014). There are, nevertheless, many unresolved issues that impede the understanding of internal copy pathways of use in motor control. One concerns the organization of spinal circuits dedicated to discrete elements of limb movement. LRN-projecting V2a interneurons are restricted to the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord and absent from more caudal segments (Azim et al. 2014), despite the presence of other classes of neurons in lumbar cord that project to the LRN (Arshavsky et al. 1978a; Ekerot 1990). These observations indicate that the molecular rules of neural circuit organization applicable to the fore- and hind-limb may differ. The concept of stereotypic motor circuits with repeated architecture across spinal segments may therefore be an oversimplification.

From a behavioral perspective, the disruption in reaching upon elimination of cervical V2a interneurons is selective, in that locomotor and digit extension appear unaffected. This selectivity in behavioral perturbation supports the view that forelimb movement is modular in design and that this modularity emerges at least in part from the differential recruitment of discrete spinal interneuron circuits during distinct behaviors (Bizzi et al. 2008; Alstermark and Isa 2012). Consistent with this notion, genetic inactivation of another set of excitatory pre-motor interneurons, dI3 interneurons, in mice impacts distal grasp performance (Bui et al. 2013). And as discussed above, the loss of cervical GABApre neurons produces limb oscillations and degrades forelimb movement in a manner quite distinct from the consequences of V2a or dI3 interneuron disruption (Azim et al. 2014; Fink et al. 2014) (Fig. 4C,D and Fig. 5D). Moreover, the modularity of PN circuit organization appears to be malleable since silencing PNs in primates affects both reaching and grasping movements (Kinoshita et al. 2012). Evolutionary modifications in internal copy circuit connectivity and function may therefore underlie aspects of enhanced manual dexterity (Isa et al. 2007).

How does activation of the PN-LRN pathway elicit a rapid modulation of motor neuron activity? Anatomically, the most credible cerebellar feedback loop involves collateral projections from LRN neurons to deep cerebellar nuclei, which in turn excite reticulospinal projections to motor neurons (Carpenter and Nova 1960; Matsushita and Ikeda 1976; Schultz et al. 1979; Wu et al. 1999; Alstermark and Ogawa 2004; Soteropoulos and Baker 2008) – in effect a feedback loop that excites motor neurons three synapses downstream of LRN activation (Fig. 6C). The fact that reticulospinal neurons can activate forelimb motor neurons within about one millisecond supports the plausibility of such a feedback pathway (Azim et al. 2014). One potential advantage of a subcortical positive feedback loop is that short latency effects could contribute to motor stability, as has been suggested for oculomotor control (Lisberger 2009). This does not exclude the possibility that longer-latency or parallel cerebellar-motor loops supplement the most rapid responses and contribute to a more refined modulation of movement (Fig. 6C). The red nucleus receives direct input from the interposed deep cerebellar nucleus and contains rubrospinal projection neurons that have been implicated in the control of distal forelimb motor neuron pools (Fujito and Aoki 1995). Additionally, a polysynaptic pathway from the dentate deep cerebellar nucleus to the ventral anterior and ventral lateral thalamic nuclei provides inputs to posterior parietal and motor cortical regions thought to integrate feedback, prediction and reward signals for the flexible updating of movements (Andersen et al. 1997; Scott 2004; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008; Pruszynski et al. 2011) (Fig. 6C). The potential diversity of PN feedback pathways emphasizes the need for selective circuit manipulations when resolving the grain of internal feedback control.

Little is known about the precise structure of copy information conveyed by the PN-LRN pathway, or whether cerebellar circuits use these signals to implement a forward model and predict movement outcome. The LRN-cerebellar system has been speculated to have diverse roles, ranging from relay of spinal pattern generator activity during rhythmic movement (Arshavsky et al. 1978a), to clock-like representation of time (Xu et al. 2013), and the integration of postural and limb motor signals (Alstermark and Ekerot 2013). Resolving the nature of copy signals conveyed by the PN-LRN circuit and how they reflect motor commands should help to pinpoint aspects of feedback relevant for updating forelimb motor acts. Such insight could provide new inroads into cerebellar cortical circuits and their putative contributions to forward model implementation (Desmurget and Grafton 2000; Shadmehr and Krakauer 2008; Bastian 2011).

Finally, a clearer understanding of internal copy pathways in motor control may help to clarify potential non-motor contributions to cognition and neuropsychiatric disorders (Ito 2008; Strick et al. 2009; Bastian 2011). Internal feedback circuits enabling predictive sensory cancellation during self-initiated behaviors could conceivably be disrupted in patients with schizophrenia (Ford and Mathalon 2012; Shergill et al. 2014). The recent identification in mice of an internal copy pathway involved in inhibiting auditory cortical neurons during self-generated movement (Schneider et al. 2014) provides an experimentally tractable circuit of potential relevance to models of schizophrenia. Thus PNs likely represent an exemplar of other internal copy pathways, the study of which may reveal anatomical and computational features relevant to circuits in motor and sensory systems (Poulet and Hedwig 2007; Azim and Alstermark 2015).

Merging internal and external feedback

How might presynaptic gain control and internal copy feedback be combined into a more coherent understanding of forelimb motor control? Admittedly, our findings have merely scratched the surface of the ways in which these pathways contribute to forelimb movement. A more complete view of the interaction between external and internal feedback pathways may derive from theoretical considerations of motor circuitry, viewed through the lens of optimal feedback control theory. This scheme describes a formal relationship between motor command, feedback, and cost, and provides an explanation of how movement is continually updated and optimized for the task at hand (Todorov and Jordan 2002; Scott 2004). Two salient features of this theory are of particular relevance to PN internal copy and presynaptic inhibitory circuits.

A central proposition of optimal feedback control is that the motor system generates online estimates of the current state of the limb, so as to implement appropriate corrections in command and trajectory (Scott 2004). In this framework, estimates of limb state benefit from a diversity of feedback signals – the more feedback information, the more precise the estimate. Indeed, the accuracy of subjects’ proprioceptive assessment of limb location is improved when movements are self-initiated, in contrast to conditions when the limb is moved passively and no commands or copies are conveyed (Fuentes and Bastian 2010; Bhanpuri et al. 2013). These findings are consistent with the idea that internal copy feedback is continuously integrated with delayed sensory information to generate more accurate estimates of the current state of the limb. An extension of this notion is that these estimates will benefit from diverse internal copy pathways.

In the spinal cord, the proposition that internal copies of limb motor signals exist in a variety of anatomical arrangements has received some experimental support. The ventral spinocerebellar tract has long been thought to convey pre-motor copy information directly to cerebellar circuits (Lundberg 1971; Arshavsky et al. 1978b; Jankowska and Hammar 2013). Moreover, recent studies in mice have revealed several genetically-defined excitatory and inhibitory spinal pathways that convey copies of forelimb motor signals to the LRN (Pivetta et al. 2014), providing further evidence that many spinal input systems converge on LRN neurons (Kunzle 1973; Clendenin et al. 1974; Ekerot 1990; Alstermark and Lundberg 1992; Alstermark and Ekerot 2013). The repertoire of mammalian forelimb movements is vast, and thus it is not altogether surprising that the diversity of internal copy circuits and the motor behaviors they regulate might be comparably complex.

A second principle of optimal feedback control is that the motor system updates movement by modulating the level of sensory feedback gain. After perturbation of the limb, forelimb movement corrections occur well before the onset of voluntary reaction. Yet in humans, corrective adjustments that occur within ~50 to 100 msec account for the complexities of limb dynamics and exhibit a biomechanical sophistication beyond the capabilities of simple reflex arcs (Todorov and Jordan 2002; Scott 2004; Pruszynski et al. 2011). Optimal feedback control posits that motor updating is achieved by adjusting dynamically the level of sensory feedback gain; and that adjustment occurs throughout the course of movement, permitting high gain at moments beneficial to behavior (Scott 2004; Franklin and Wolpert 2011). In this way movement can be optimized for task performance by accounting for the changing state of the limb and its environmental context. Indeed, there is substantial experimental evidence that the gain of sensory feedback changes over the course of movement to account for altered conditions – such as a displacement of hand or target location (Franklin and Wolpert 2008; Dimitriou et al. 2012; Crevecoeur and Scott 2013). Neurons in primary motor cortex that integrate feedback to drive movement corrections provide one potential instance of a circuit in which dynamic gain regulation can be translated into appropriate motor commands (Pruszynski et al. 2011).

Presynaptic inhibitory neurons, by virtue of their axo-axonic connections with sensory neurons, have the capacity to modulate specific afferent channels and thus seem well suited for selective and flexible control of feedback gain. Targeted elimination of all presynaptic inhibition in the cervical spinal cord has a profound impact on limb stability (Fink et al. 2014), but discrete subtypes dedicated to modulating distinct afferent pathways with more specialized functions surely exist within this broad population. The selectivity of sensory afferent targeting could permit behaviorally-relevant feedback gains in supraspinal centers to remain high, while reducing gains in the spinal cord in order to maintain local stability (Scott and Crevecoeur 2014). Thus, defining the subtype diversity inherent in presynaptic inhibitory gain control could help to clarify the neural implementation of feedback control theory.

Conclusions

Decades of research in primates and cats have identified plausible neural substrates for external and internal feedback pathways, and have proposed their influence on movement. Recent advances in the genetic manipulation of circuits in mice hope to build on this foundation, with the goal of linking neuron and circuit to behavior with ever greater precision. The two circuits discussed here illustrate some of the initial insights that can be obtained about the contributions of gain control and internal copy pathways to skilled forelimb movement. The grain of organization of these neural mechanisms, however, is surely far finer than the current state of experimental manipulation. One major challenge for the future will therefore be to obtain greater neuronal subtype resolution in the dissection of motor circuitry. Yet as the number of isolated neural elements and their identified behavioral functions multiply, it remains equally important to design experiments that test and refine theoretical descriptions of motor control and its encoded behaviors.

These thoughts are not entirely new. The French Enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot wrote, “We are all instruments endowed with feeling and memory. Our senses are so many strings that are struck by surrounding objects and that also frequently strike themselves.” Some 250 years later these words still hold relevance in attempts to understand the neural basis of motor behavior. Sensory information is intertwined with behavioral output and thus the comprehension of one is futile without an appreciation of the other. Diderot’s words also emphasize a more subtle point – feedback can be triggered both by the environment and by the individual. Defining how the brain orchestrates behavior inevitably requires an understanding of the influence of both external and internal sources of feedback information.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues and collaborators B. Alstermark, J. Jiang, L.F. Abbott, K. Croce and Z.J. Huang. We are also grateful to J.W. Krakauer, A. Karpova, M. Churchland and C.E. Schoonover for helpful discussions and feedback. E.A. was supported by a National Institutes of Health K99 award (NS088193) and a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation/Howard Hughes Medical Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship. T.M.J. was supported by NIH grant NS033245, the Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Foundation and Project A.L.S., and is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Ali MS, Hou ZK, Noori MN. Stability and performance of feedback control systems with time delays. Computers & Structures. 1998;66:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Ekerot CF. The Lateral Reticular Nucleus: a precerebellar center providing the Cerebellum with overview and integration of motor functions at systems level. A new hypothesis. The Journal of physiology. 2013;591:5453–5458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.256669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Isa T. Circuits for skilled reaching and grasping. Annual review of neuroscience. 2012;35:559–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Kummel H, Pinter MJ, Tantisira B. Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 17. Axonal projection and termination of C3-C4 propriospinal neurones in the C6-Th1 segments. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1990;81:447–461. doi: 10.1007/BF02423494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Lindstrom S, Lundberg A, Sybirska E. Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 8. Ascending projection to the lateral reticular nucleus from C3-C4 propriospinal also projecting to forelimb motoneurones. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1981a;42:282–298. doi: 10.1007/BF00237495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Lundberg A. The C3-C4 propriospinal system: target-reaching and food-taking. In: Jami L, Pierrot-Deseilligny EZD, editors. Muscle afferents and spinal control of movement. Pergamon; Oxford, UK: 1992. pp. 327–354. [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Lundberg A, Norrsell U, Sybirska E. Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 9. Differential behavioural defects after spinal cord lesions interrupting defined pathways from higher centres to motoneurones. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1981b;42:299–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00237496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alstermark B, Ogawa J. In vivo recordings of bulbospinal excitation in adult mouse forelimb motoneurons. Journal of neurophysiology. 2004;92:1958–1962. doi: 10.1152/jn.00092.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Snyder LH, Bradley DC, Xing J. Multimodal representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex and its use in planning movements. Annual review of neuroscience. 1997;20:303–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshavsky YI, Gelfand IM, Orlovsky GN, Pavlova GA. Messages conveyed by spinocerebellar pathways during scratching in the cat. I. Activity of neurons of the lateral reticular nucleus. Brain research. 1978a;151:479–491. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arshavsky YI, Gelfand IM, Orlovsky GN, Pavlova GA. Messages conveyed by spinocerebellar pathways during scratching in the cat. II. Activity of neurons of the ventral spinocerebellar tract. Brain research. 1978b;151:493–506. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi S, Betley JN, Comer JD, Brenner-Morton S, Bar V, Shimoda Y, Watanabe K, Peles E, Jessell TM, Kaltschmidt JA. Neuronal ig/caspr recognition promotes the formation of axoaxonic synapses in mouse spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;81:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim E. Neuroscience. Shortcuts and checkpoints on the road to skilled movement. Science. 2014;346:554–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1260778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim E, Alstermark B. Skilled forelimb movements and internal copy motor circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;33:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim E, Jiang J, Alstermark B, Jessell TM. Skilled reaching relies on a V2a propriospinal internal copy circuit. Nature. 2014;508:357–363. doi: 10.1038/nature13021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldissera F, Hultborn H, Illert M. Integration in spinal neuronal systems. In: Brookhart JM, Mountcastle VB, Brooks VB, editors. Handbook of Physiology, Sect. I: The Nervous System, Vol. II: Motor Control, Part I. American Physiological Society; Bethesda, MD: 1981. pp. 509–595. [Google Scholar]

- Bastian AJ. Moving, sensing and learning with cerebellar damage. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2011;21:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betley JN, Wright CVE, Kawaguchi Y, ErdElyi F, SzabO G, Jessell TM, Kaltschmidt JA. Stringent specificity in the construction of a GABAergic presynaptic inhibitory circuit. Cell. 2009;139:161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanpuri NH, Okamura AM, Bastian AJ. Predictive modeling by the cerebellum improves proprioception. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:14301–14306. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0784-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bizzi E, Cheung VC, d’Avella A, Saltiel P, Tresch M. Combining modules for movement. Brain research reviews. 2008;57:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner N, Bialek W, de Ruyter van Steveninck R. Adaptive rescaling maximizes information transmission. Neuron. 2000;26:695–702. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81205-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodal A. Spinal afferents to the lateral reticular nucleus of the medulla oblongata in the cat; an experimental study. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1949;91:259–295. doi: 10.1002/cne.900910206. incl 252 pl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui TV, Akay T, Loubani O, Hnasko TS, Jessell TM, Brownstone RM. Circuits for Grasping: Spinal dI3 Interneurons Mediate Cutaneous Control of Motor Behavior. Neuron. 2013;78:191–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Stein RB. A method for simulating the reflex output of a motoneuron pool. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1987;21:91–104. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaday C, Stein RB. The effects of postsynaptic inhibition on the monosynaptic reflex of the cat at different levels of motoneuron pool activity. Experimental Brain Research. 1989:77. doi: 10.1007/BF00249610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MB, Nova HR. Descending division of the brachium conjunctivum in the cat a cerebello-reticular system. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1960;114:295–305. doi: 10.1002/cne.901140307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clendenin M, Ekerot CF, Oscarsson O, Rosen I. Functional organization of two spinocerebellar paths relayed through the lateral reticular nucleus in the cat. Brain research. 1974;69:140–143. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conradi S. Ultrastructure of dorsal root boutons on lumbosacral motoneurons of the adult cat, as revealed by dorsal root section. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1969;332(Supplementum):85–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crevecoeur F, Scott SH. Priors engaged in long-latency responses to mechanical perturbations suggest a rapid update in state estimation. PLoS computational biology. 2013;9:e1003177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget M, Grafton S. Forward modeling allows feedback control for fast reaching movements. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2000;4:423–431. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01537-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriou M, Franklin DW, Wolpert DM. Task-dependent coordination of rapid bimanual motor responses. Journal of neurophysiology. 2012;107:890–901. doi: 10.1152/jn.00787.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Eccles RM, Magni F. Central inhibitory action attributable to presynaptic depolarization produced by muscle afferent volleys. Journal of Physiology. 1961;159:147–166. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Kostyuk PG, Schmidt RF. Central pathways responsible for depolarization of primary afferent fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1962;161:237–257. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp006884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerot CF. The lateral reticular nucleus in the cat. VIII. Excitatory and inhibitory projection from the bilateral ventral flexor reflex tract (bVFRT) Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1990;79:129–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00228881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink AJ, Croce KR, Huang ZJ, Abbott LF, Jessell TM, Azim E. Presynaptic inhibition of spinal sensory feedback ensures smooth movement. Nature. 2014;509:43–48. doi: 10.1038/nature13276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Mathalon DH. Anticipating the future: automatic prediction failures in schizophrenia. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology. 2012;83:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank K, Fuortes M. Presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition of monosynaptic reflexes. Federation Proceedings. 1957;16:49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, Wolpert DM. Specificity of reflex adaptation for task-relevant variability. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:14165–14175. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4406-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin DW, Wolpert DM. Computational mechanisms of sensorimotor control. Neuron. 2011;72:425–442. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes CT, Bastian AJ. Where is your arm? Variations in proprioception across space and tasks. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:164–171. doi: 10.1152/jn.00494.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujito Y, Aoki M. Monosynaptic rubrospinal projections to distal forelimb motoneurons in the cat. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1995;105:181–190. doi: 10.1007/BF00240954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghez C, Gordon J, Ghilardi MF. Impairments of reaching movements in patients without proprioception. II. Effects of visual information on accuracy. Journal of neurophysiology. 1995;73:361–372. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Ghilardi MF, Ghez C. Impairments of reaching movements in patients without proprioception. I. Spatial errors. Journal of neurophysiology. 1995;73:347–360. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. A morphological basis for pre-synaptic inhibition? Nature. 1962;193:82–83. doi: 10.1038/193082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haith AM, Krakauer JW. Theoretical models of motor control and motor learning. In: GA, TW, BNJ, editors. The Routledge Handbook of Motor Control and Motor Learning. Routledge; London, UK: 2013. pp. 7–28. [Google Scholar]

- Harris CM, Wolpert DM. Signal-dependent noise determines motor planning. Nature. 1998;394:780–784. doi: 10.1038/29528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DI, Mackie M, Nagy GG, Riddell JS, Maxwell DJ, Szabó G, Erdélyi F, Veress G, Szücs P, Antal M, et al. P boutons in lamina IX of the rodent spinal cord express high levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase-65 and originate from cells in deep medial dorsal horn. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:9038–9043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503646102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultborn H, Meunier S, Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Shindo M. Changes in presynaptic inhibition of Ia fibres at the onset of voluntary contraction in man. Journal of Physiology. 1987;389:757–772. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illert M, Jankowska E, Lundberg A, Odutola A. Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 7. Effects from the reticular formation on C3-C4 propriospinal neurones. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1981;42:269–281. doi: 10.1007/BF00237494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illert M, Lundberg A, Padel Y, Tanaka R. Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 5. Properties of and monosynaptic excitatory convergence on C3--C4 propriospinal neurones. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1978;33:101–130. doi: 10.1007/BF00238798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isa T, Ohki Y, Alstermark B, Pettersson LG, Sasaki S. Direct and indirect cortico-motoneuronal pathways and control of hand/arm movements. Physiology. 2007;22:145–152. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. Control of mental activities by internal models in the cerebellum. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2008;9:304–313. doi: 10.1038/nrn2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniuk AN, Whishaw IQ. On the origin of skilled forelimb movements. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:372–376. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E. Spinal interneuronal systems: identification, multifunctional character and reconfigurations in mammals. Journal of Physiology. 2001;533:31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0031b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowska E, Hammar I. Interactions between spinal interneurons and ventral spinocerebellar tract neurons. The Journal of physiology. 2013;591:5445–5451. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.248740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KE, Hamilton AF, Wolpert DM. Sources of signal-dependent noise during isometric force production. Journal of neurophysiology. 2002;88:1533–1544. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.3.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawato M, Gomi H. The cerebellum and VOR/OKR learning models. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90008-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita M, Matsui R, Kato S, Hasegawa T, Kasahara H, Isa K, Watakabe A, Yamamori T, Nishimura Y, Alstermark B, et al. Genetic dissection of the circuit for hand dexterity in primates. Nature. 2012;487:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature11206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno M. Mechansim of Facilitation and Depression of the Excitatory Synaptic Potential in Spinal Motoneurones. The Journal of physiology. 1964;175:100–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1964.sp007505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzle H. The topographic organization of spinal afferents to the lateral reticular nucleus of the cat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1973;149:103–115. doi: 10.1002/cne.901490107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin SB. Matching coding, circuits, cells, and molecules to signals: general principles of retinal design in the fly’s eye. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 1994;13:165–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger SG. Internal models of eye movement in the floccular complex of the monkey cerebellum. Neuroscience. 2009;162:763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.03.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomelí J, Quevedo J, Linares P, Rudomin P. Local control of information flow in segmental and ascending collaterals of single afferents. Nature. 1998;395:600–604. doi: 10.1038/26975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg A. Function of the ventral spinocerebellar tract. A new hypothesis. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1971;12:317–330. doi: 10.1007/BF00237923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita M, Ikeda M. Projections from the lateral reticular nucleus to the cerebellar cortex and nuclei in the cat. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1976;24:403–421. doi: 10.1007/BF00235006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier J, Kalaska JF. Comparison of variability of initial kinematics and endpoints of reaching movements. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1999;125:139–152. doi: 10.1007/s002210050669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miri A, Azim E, Jessell TM. Edging toward entelechy in motor control. Neuron. 2013;80:827–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morasso P. Spatial control of arm movements. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 1981;42:223–227. doi: 10.1007/BF00236911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrot-Deseilligny E, Burke DJ. The circuitry of the human spinal cord : neuroplasticity and corticospinal mechanisms. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pivetta C, Esposito MS, Sigrist M, Arber S. Motor-circuit communication matrix from spinal cord to brainstem neurons revealed by developmental origin. Cell. 2014;156:537–548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulet JF, Hedwig B. New insights into corollary discharges mediated by identified neural pathways. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prablanc C, Martin O. Automatic control during hand reaching at undetected two-dimensional target displacements. Journal of neurophysiology. 1992;67:455–469. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochazka A. Quantifying Proprioception. Progress in Brain Research. 1999;123:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruszynski JA, Kurtzer I, Nashed JY, Omrani M, Brouwer B, Scott SH. Primary motor cortex underlies multi-joint integration for fast feedback control. Nature. 2011;478:387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature10436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell JC, Traub MM, Day BL, Obeso JA, Thomas PK, Marsden CD. Manual motor performance in a deafferented man. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1982;105 (Pt 3):515–542. doi: 10.1093/brain/105.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudomin P. In search of lost presynaptic inhibition. Experimental Brain Research. 2009;196:139–151. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1758-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudomin P, Schmidt RF. Presynaptic inhibition in the vertebrate spinal cord revisited. Experimental Brain Research. 1999;129:1–37. doi: 10.1007/s002210050933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudomin P, Solodkin M, Jimenez I. PAD and PAH response patterns of group Ia- and Ib-fibers to cutaneous and descending inputs in the cat spinal cord. Journal of neurophysiology. 1986:987–1006. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RF. Presynaptic inhibition in the vertebrate central nervous system. Ergebnisse der Physiologie. 1971;63:20–101. doi: 10.1007/BFb0047741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider DM, Nelson A, Mooney R. A synaptic and circuit basis for corollary discharge in the auditory cortex. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W, Montgomery EB, Jr, Marini R. Proximal limb movements in response to microstimulation of primate dentate and interpositus nuclei mediated by brain-stem structures. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1979;102:127–146. doi: 10.1093/brain/102.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SH. Optimal feedback control and the neural basis of volitional motor control. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2004;5:532–546. doi: 10.1038/nrn1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SH, Crevecoeur F. Neuroscience: Feedback throttled down for smooth moves. Nature. 2014;509:38–39. doi: 10.1038/509038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki K, Perlmutter SI, Fetz EE. Sensory input to primate spinal cord is presynaptically inhibited during voluntary movement. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6:1309–1316. doi: 10.1038/nn1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Krakauer JW. A computational neuroanatomy for motor control. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 2008;185:359–381. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1280-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadmehr R, Smith MA, Krakauer JW. Error correction, sensory prediction, and adaptation in motor control. Annual review of neuroscience. 2010;33:89–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shergill SS, White TP, Joyce DW, Bays PM, Wolpert DM, Frith CD. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of impaired sensory prediction in schizophrenia. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71:28–35. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soteropoulos DS, Baker SN. Bilateral representation in the deep cerebellar nuclei. The Journal of physiology. 2008;586:1117–1136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RB, Oğuztöreli MN. Tremor and other oscillations in neuromuscular systems. Biological Cybernetics. 1976;22:147–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00365525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strick PL, Dum RP, Fiez JA. Cerebellum and nonmotor function. Annual review of neuroscience. 2009;32:413–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, He M, Wu P, Kim S, Paik R, Sugino K, Kvitsiani D, Kvitsani D, Fu Y, Lu J, et al. A resource of Cre driver lines for genetic targeting of GABAergic neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian N, Petersen C, Kash S, Baekkeskov S, Copenhagen D, Nicoll R. The role of the synthetic enzyme GAD65 in the control of neuronal gamma-aminobutyric acid release. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999;96:12911–12916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorov E, Jordan MI. Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nature neuroscience. 2002;5:1226–1235. doi: 10.1038/nn963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley B, Wieniawa-Narkiewicz E, Nicol MJ. Ultrastructural evidence related to presynaptic inhibition of primary muscle afferents in Clarke’s column of the cat. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1987;7:236–243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-01-00236.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AHD, Bazzaz AA. GABA and glycine-like immunoreactivity at axoaxonic synapses on 1a muscle afferent terminals in the spinal cord of the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;433:335–348. doi: 10.1002/cne.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whishaw IQ. An endpoint, descriptive, and kinematic comparison of skilled reaching in mice (Mus musculus) with rats (Rattus norvegicus) Behav Brain Res. 1996;78:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM, Miall RC. Forward Models for Physiological Motor Control. Neural networks : the official journal of the International Neural Network Society. 1996;9:1265–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(96)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HS, Sugihara I, Shinoda Y. Projection patterns of single mossy fibers originating from the lateral reticular nucleus in the rat cerebellar cortex and nuclei. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1999;411:97–118. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990816)411:1<97::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Jones S, Edgley SA. Event time representation in cerebellar mossy fibres arising from the lateral reticular nucleus. The Journal of physiology. 2013;591:1045–1062. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.244723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Wilson M, Zee DS, Shadmehr R. The intrinsic value of visual information affects saccade velocities. Experimental brain research Experimentelle Hirnforschung Experimentation cerebrale. 2009;196:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1879-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]