Abstract

The TSH receptor (TSHR) extracellular domain (ECD) comprises a N-terminal leucine-rich repeat domain and an hinge region (HR), the latter contributing to ligand binding and critical for receptor activation. The crystal structure of the leucine-rich repeat domain component has been solved, but previous attempts to generate conformationally intact complete ECD or the isolated HR component for structural analysis have failed. The TSHR HR contains a C-peptide segment that is removed during spontaneous TSHR intramolecular cleavage into disulfide linked A- and B-subunits. We hypothesized that deletion of the redundant C-peptide would overcome the obstacle to generating conformationally intact TSHR ECD protein. Indeed, lacking the C-peptide region, the TSHR ECD (termed ECD-D1) and the isolated HR (termed HR-D1) were secreted into medium of insect cells infected with baculoviruses coding for these modified proteins. The identities of TSHR ECD-D1 and HR-D1 were confirmed by ELISA and immunoblotting using TSHR-specific monoclonal antibodies. The TSHR-ECD-D1 in conditioned medium was folded correctly, as demonstrated by its ability to inhibit radiolabeled TSH binding to the TSH holoreceptor. The TSHR ECD-D1 purification was accomplished in a single step using a TSHR monoclonal antibody affinity column, whereas the HR-D1 required a multistep protocol with a low yield. In conclusion, we report a novel approach to generate the TSHR ECD, as well as the isolated HR in insect cells, the former in sufficient amounts for structural studies. However, such studies will require previous complexing of the ECD with a ligand such as TSH or a thyroid-stimulating antibody.

The glycoprotein hormone receptors (GPHRs) contain 3 structural components: an extracellular domain (ECD) comprising a N-terminal leucine-rich repeat domain (LRD) linked by a hinge region (HR) to the heptahelical transmembrane domain (1, 2). Since the molecular cloning of the TSH receptor (TSHR) in 1989 (3–5), there have been periodic attempts to generate the TSHR ECD in a conformational form suitable for crystallization in order to determine its atomic structure. Early efforts in a variety of expression systems, including Chinese hamster ovary and insect cells were unsuccessful (reviewed in Ref. 6). A more recent attempt using a yeast expression system also failed (7). Attaching a glycosylphosphatidyl inositol anchor to the TSHR ECD in lieu of the transmembrane domain does lead to efficient expression of conformationally intact protein on the surface of mammalian cells (8–10). However, no structural information on this material has been emerged.

Given the difficulties experienced in expressing the full TSHR ECD, and because the TSHR (uniquely among the GPHR) undergoes intramolecular cleavage within the HR into disulfide-linked A- and B-subunits (11, 12), nearly 20 years ago we hypothesized that A-subunits truncated at potential cleavage sites would be secreted at high levels by eukaryotic mammalian cells. However, despite generating milligram quantities of purified A-subunits (LRD and N-terminal portion of the HR; amino acids 22–289) (13), crystals were not generated by experienced structural laboratories with whom we collaborated. A TSHR A-subunit protein truncated at its C terminus (LRD alone; amino acid residues 22–260) was successfully generated in insect cells and its crystal structure determined in complex with Fab from a thyroid stimulating (14) and a TSH blocking autoantibody (15). The crystal structure of the FSH receptor (FSHR) LRD in complex with FSH was also reported (16). Nevertheless, the structure of the isolated LRD alone sheds little light on the mechanism of receptor activation.

Very recently, the crystal structure of the entire FSHR ECD in complex with FSH revealed ligand traction on the HR, particularly involving residue Y335, as a likely mechanism for FSHR activation (17). However, there is poor homology between the TSHR and FSHR HRs, including an “insertion” of 50 additional amino acid residues in the former. The thyroid stimulating antibody (TSAb) and TSH mechanisms of action are also clearly different. Mutation of critical TSHR residue Y385 (homologous to FSHR Y335) abrogates TSH but not TSAb binding and function (18, 19). Therefore, determining the crystal structure of the entire TSHR ECD (LRD plus HR) remains an important unfulfilled goal.

The present report describes a novel approach to generate the TSHR ECD as well as the isolated HR in sufficient amounts for structural studies. The underlying principle was to exclude the redundant C-peptide region that is not involved in ligand binding and adenylyl cyclase activation (20, 21) and removed during spontaneous intramolecular cleavage into A- and B-subunits (22, 23). We recognize that this structure will not provide information on “neutral” antibodies that interact with the C-peptide region (24).

Materials and Methods

Baculovirus constructs and expression

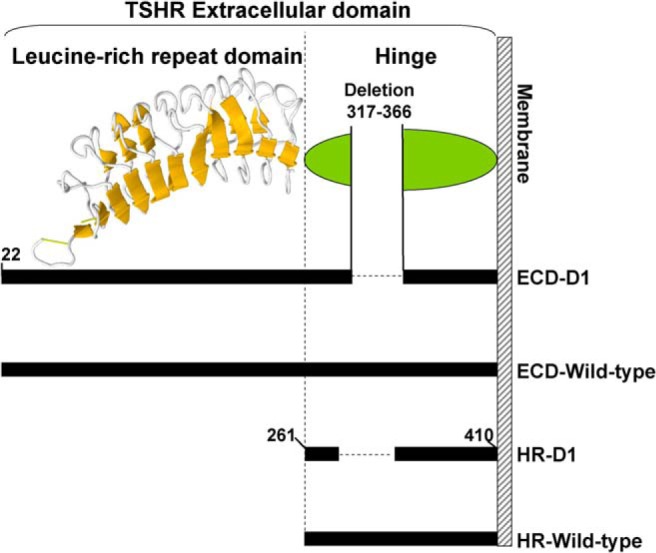

Two TSHR ECD cDNAs (Figure 1) were generated by PCR using the indicated templates: 1) wild-type TSHR-ECD (amino acid residues 22–410; template pcDNA-TSHR-wild-type) (4); and 2) TSHR-ECD-D1 (amino acids 22–410 with residues 317–366 deleted; template pSV2-neo-ECE-TSHR-D1) (25). Two TSHR HR cDNAs (Figure 1) were generated using the same templates but with a 5′-end primer encoding amino acid residue 261 rather than amino acid residue 22, namely: 1) wild-type TSHR HR (amino acid residues 261–410); and 2) TSHR HR-D1 with residues 317–366 deleted. The 4 TSHR cDNAs were used to generate recombinant protein in the Bac-to-Bac baculovirus expression system using the virus signal peptide in place of the TSHR signal peptide (amino acid residues 1–21) according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Life Technologies). In brief, the cDNA were ligated into the vector pFastBac/HBM-TOPO coding for 6H residues at the C terminus of the translated protein plasmids amplified in One Shot Mach1 T1 cells were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing and used to transform DH10Bac cells. Recombinant Bacmid cDNAs were transfected into Sf9 cells and after 3 amplifications to attain a high titer, viruses were used to infect High Five cells. Approximate viral titers were estimated by PCR using TSHR-specific oligonucleotides and serially diluted viral stocks. We observed optimal protein expression at 3 days with a multiplicity of infection of 100, indicating that the PCR titering method overestimated the true viral titer approximately 10-fold.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of the amino acid residues deleted in the TSHR ECD and HR. The TSHR LRD shown (residues 22–260) is the major portion of the LRD for which the atomic structure is known (Structure data bank ID, 2XWT). Relative to the other GPHRs, the TSHR HR contains an additional 50-amino acid residues, approximating (because of poor homology in the region) TSHR residues 317–366. The C-peptide region that is removed from the HR during intramolecular cleavage of the holoreceptor includes these residues. ECD-D1, ECD with amino acid residues 317–366 deleted; HR-D1, HR with amino acid residues 317–366 deleted.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Wells were coated with 200 μL of conditioned culture medium from infected High Five cells (1 h at 37°C). After rinsing with buffer containing 10mM Tris and 50mM NaCl (pH 7.4), the wells were blocked (1 h at room temperature) with 250 μL of the same buffer supplemented with 5% BSA, followed by extensive rinsing with albumin-free buffer. Bound TSHR antigen was detected using the next mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): 1) 4C1 (Morphosys); 0.1 mL at 10 μg/mL, epitope, including TSHR-ECD C-terminal residues 381–384 (26); and 2) 3BD10; 0.1 mL at 3 μg/mL; N-terminal epitope with residues within the region of 22–56 (27). Where indicated, control wells were incubated with medium from High Five cells infected with virus expressing β-glucuronidase (pFastBac-Gus; Life Technologies). As a positive control, wells were coated with purified TSHR-289 (0.1 mL at 5 μg/mL) (28). This material secreted by CHO cells comprises TSHR amino acid residues 22–289, namely the LRD and an N-terminal portion of the HR (Figure 1). After 4 rinses with TBST buffer (20mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20 [pH 7.4]), mAb binding was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-IgG (Sigma-Aldrich). The signal was developed with o-phenylenediamine and H2O2 and the optical density read at 490 nm.

Immunoblotting

Media harvested from insect cell cultures 3 days after infection with baculoviruses encoding TSHR ECD-D1 and HR-D1. Medium from stably transfected CHO cells secreting TSHR-289 (13) was included as a control. Medium aliquots (20 μL) were applied to 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with mAb 4C1 0.5 μg/mL using Pierce Fast Western Blot kit (Thermo Scientific).

TSH binding inhibition assay

Medium harvested from High Five insect cells infected with either b-glucuronidase (as a control), the wild-type TSHR ECD or the ECD with amino acids 317–366 deleted (ECD-D1) was diluted 1:1 with “binding buffer” (Hanks' buffer without NaCl and supplemented with 250mM sucrose and 0.25% BSA). TSH radiolabeled with 125I-TSH, prepared as described previously (29), was added to this mixture (∼104 cpm/mL). After 15 minutes at room temperature, 0.25-mL aliquots of the mixtures were applied to CHO cells stably expressing the TSH holoreceptor for 4 hours at room temperature. The medium was then aspirated, the cells were rinsed rapidly 3 times with binding buffer (4°C), solubilized with 0.2-mL 1N NaOH, and radioactivity measured in a γ-counter.

Protein purification

Despite the 6 C-terminal His residues on the TSHR ECD and HR proteins, affinity purification from conditioned insect cell medium by a monoclonal anti-5His antibody column (28) required an initial capture procedure (for antibodies, see Table 1). As detected by ELISA, diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) chromatography accomplished sufficient separation for the HR from the bulk of medium proteins (primarily albumin) to permit subsequent anti-5His affinity purification followed by Superdex-75 gel filtration. However, because of total overlap between the TSHR ECD and medium proteins, we turned to affinity chromatography with CS-17, a murine mAb primarily to the LRD (30, 31), linked to CNBrSepharose 4B (Sigma-Aldrich).

Table 1.

Antibody Table

| Peptide/Protein Target | Antigen Sequence (if known) | Name of Antibody | Manufacturer, Catalog Number, and/or Name of Individual Providing the Antibody | Species Raised in; Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSHR | AA includes 381–384 | 4C1 | Morphosys | Mouse; monoclonal | 0.5–10 μg/mL |

| SC32262 | |||||

| TSHR | AA within 22–56 | 3BD10 | Rapoport lab | Mouse; monoclonal | 3 μg/mL |

| TSHR | AA at C terminus of LRD and N terminus of HR | CS-17 | Rapoport lab | Mouse; monoclonal | Beads with ∼1 mg/mL |

Results

Deletion of the C-peptide region facilitates TSHR ECD protein expression

Although the precise boundaries of the excised TSHR C-peptide region are not defined, this region includes amino acid residues 317–366 within the HR (reviewed in Refs. 6, 21). We tested the hypothesis that deletion of these 50 amino acids would permit expression and secretion of correctly folded ECD protein by insect cells (Figure 1). As a control, we generated a virus encoding the wild-type TSHR-ECD (amino acid residues 22–410).

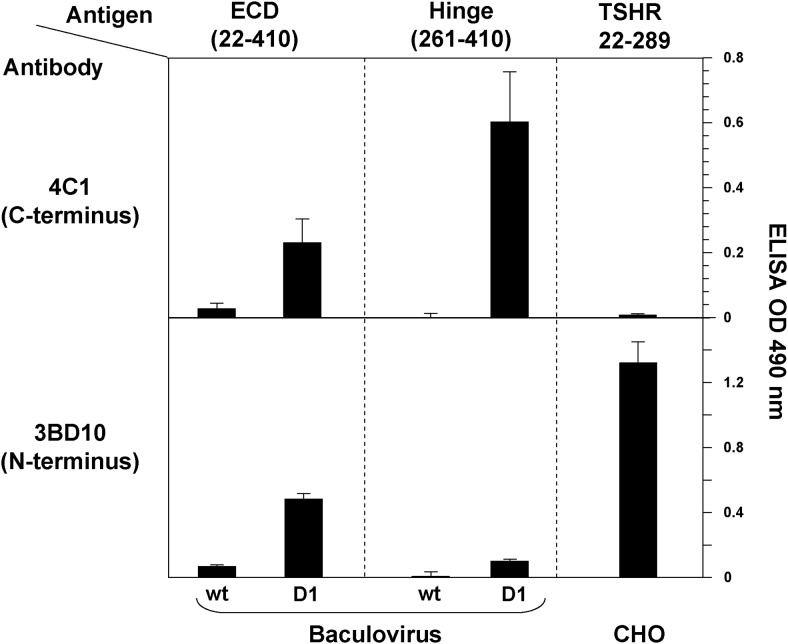

To determine whether TSHR protein was secreted by infected insect cells, ELISA wells were coated with conditioned culture medium harvested 3 days after baculovirus infection. Adherent TSHR forms were probed with mAb to the TSHR ECD C terminus (4C1) and N terminus (3BD10) (Figure 2). Consistent with previous attempts (Introduction), significant quantities of the wild-type TSHR-ECD could not be detected in the culture medium with either TSHR mAb. Remarkably, however, TSHR-ECD-D1 (amino acid residues 22–410 with residues 317–366 deleted) was clearly detected in the conditioned medium (Figure 2, upper and lower left panels).

Figure 2.

TSHR ECD and HR protein secretion by insect cells detected by ELISA. Conditioned media 3 days after baculovirus infection were plated and probed with 2 mAb; 4C1 to the C terminus (epitope, including amino acid residues 381–384) (26) and 3BD10 to the N terminus (epitope, including residues within the region of 22–56) (27). Wt, wild-type ECD or HR; D1, ECD or HR with amino acid residues 317–366 deleted. Also plated as a positive control was recombinant TSHR-289 generated in CHO cells. Data shown are the mean optical density (OD) ± SD from 2 separate experiments.

Similarly, when the same deletion was applied to the isolated HR (amino acid residues 261–410) (Figure 1), only conditioned medium from TSHR-HR-D1-infected cells contained a product detected by mAb 4C1 (Figure 1B, top middle panel). As expected because of the absence of the ECD N-terminus, mAb 3BD10 provided a minimal signal (Figure 1B, bottom middle panel). The specificity of these observations was supported by the ability of mAb 3BD10 and the inability of mAb 4C1 to detect a control antigen, recombinant TSHR-289 (amino acid residues 22–289) generated in CHO cells (Figure 2, right upper and lower panels).

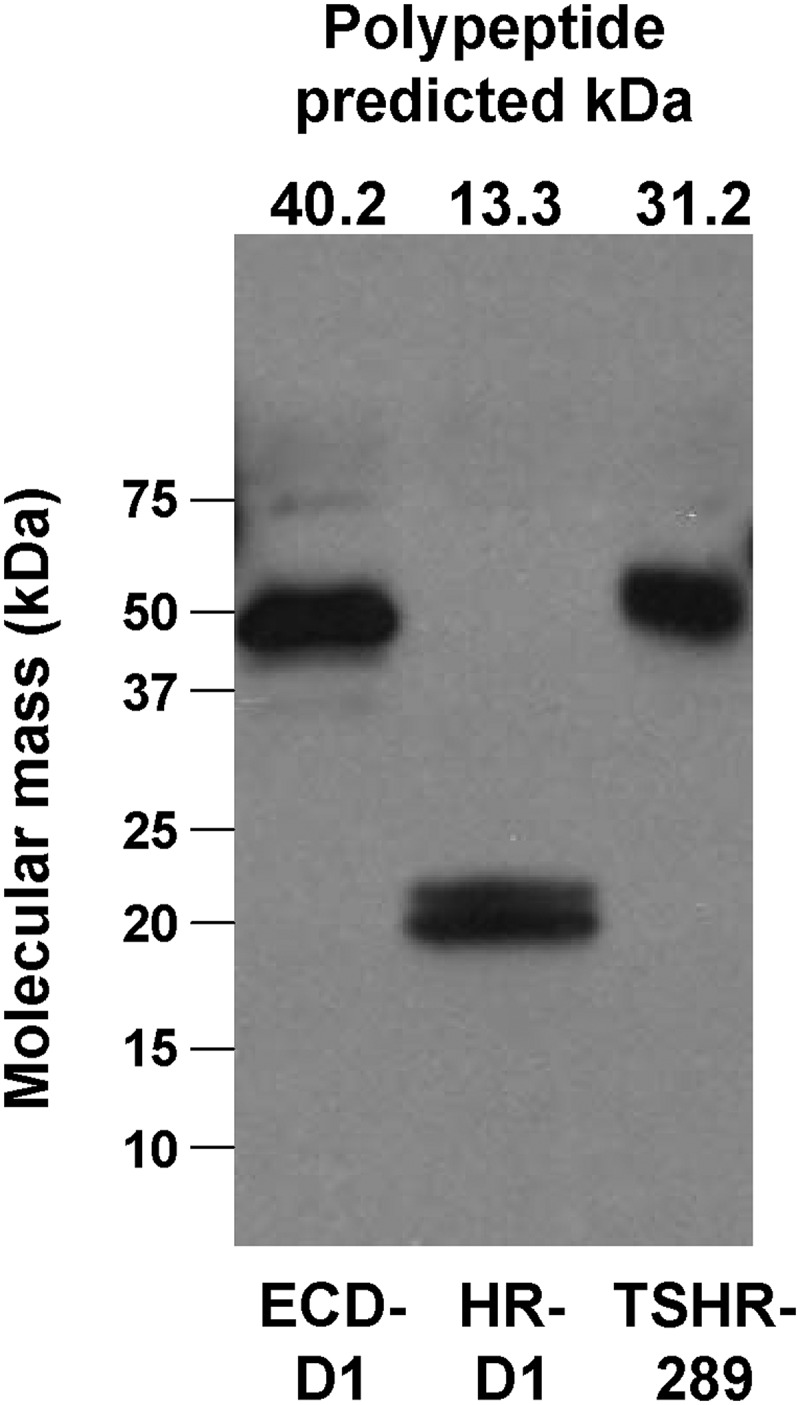

Characterization of the secreted TSHR proteins

Confirmation of the identity of the TSHR ECD-D1 and HR-D1 proteins was obtained by immunoblotting with mAb 4C1. Of note, the molecular masses of both the TSHR ECD-D1 (∼48 kDa) and the HR-D1 (∼20 kDa) were larger than their predicted polypeptide backbones of 40.2 and 13.3 kDa (Figure 3). Although the ECD-D1 has 6 N-linked glycosylation sites (all occupied in the CHO cell-derived TSHR holoreceptor) (32) compared with the single N-linked glycan motif in the HR-D1, the degree of glycosylation was relatively smaller with the ECD-D1 (∼8 kDa; 17%) than with the HR-D1 (∼7 kDa; 35%). The relatively low glycan content of the insect cell generated ECD-D1 is also evident when compared with the CHO-cell generated TSHR-289. The polypeptide backbone of TSHR-289 is 31.2 kDa, smaller than the ECD-D1 backbone of 40.2 kDa, yet on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) migrates at approximately 55 kDa (Figure 3). Of note, the HR-D1 was sometimes visible as a doublet, with components too close to represent a dimer and is, therefore, possibly the result of a variable N-linked glycan chain length.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot of TSHR ECD-D1 and HR-D1 proteins. Media harvested from insect cell cultures 3 days after baculovirus infection were probed with mAb 4C1 (see Materials and Methods). Medium from stably transfected CHO cells secreting TSHR-289 (13) was included as a control. The predicted molecular masses (kDa) of the amino acid backbones of the proteins are indicated above each lane.

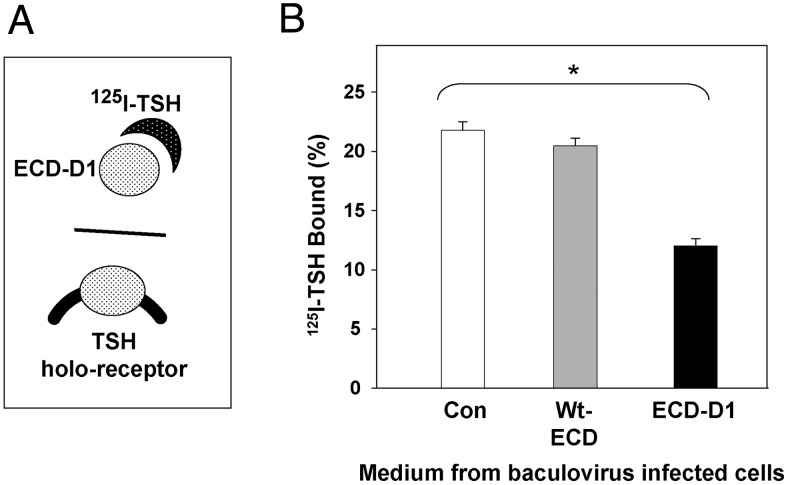

Most important, before purification the TSHR-ECD-D1 present in conditioned medium was folded correctly, as evident by its ability to diminish radiolabeled TSH binding to CHO cells expressing the wild-type TSH holoreceptor (Figure 4, A and B). No inhibition of TSH binding occurred with medium from cells infected with the intact, wild-type ECD, consistent with the very low levels of expression detected by ELISA (Figure 2). Despite expression of the HR-D1 as detected by ELISA (Figure 2), this medium had no effect on TSH binding (data not shown), as anticipated, because the major portion of the TSH binding site lies within the LRD upstream of the HR.

Figure 4.

TSH binding inhibition by TSHR ECD secreted by insect cells. A, Schematic representation of TSH binding inhibition assay. If radiolabeled TSH can bind to the TSHR ECD in conditioned medium, its binding to CHO cells stably expressing the TSH holoreceptor is inhibited. B, Medium harvested from insect cells infected with either control virus (Con) or virus expressing the wild-type TSHR ECD or the ECD with amino acids 317–366 deleted (ECD-D1) and supplemented with 125I-TSH (see Materials and Methods). After 4 hours at room temperature, the medium was removed, the cells were rinsed, solubilized with NaOH, radioactivity measured, and expressed as a percent of 125I-TSH added to each well. Bars indicate the mean ± SD of values obtained in duplicate wells. *, 125I-TSH binding with medium from ECD-D1 vs control virus infected insect cells; P < .005 (Student's t test). The data shown are representative of 3 separate experiments.

Purification of the TSHR ECD and HRs

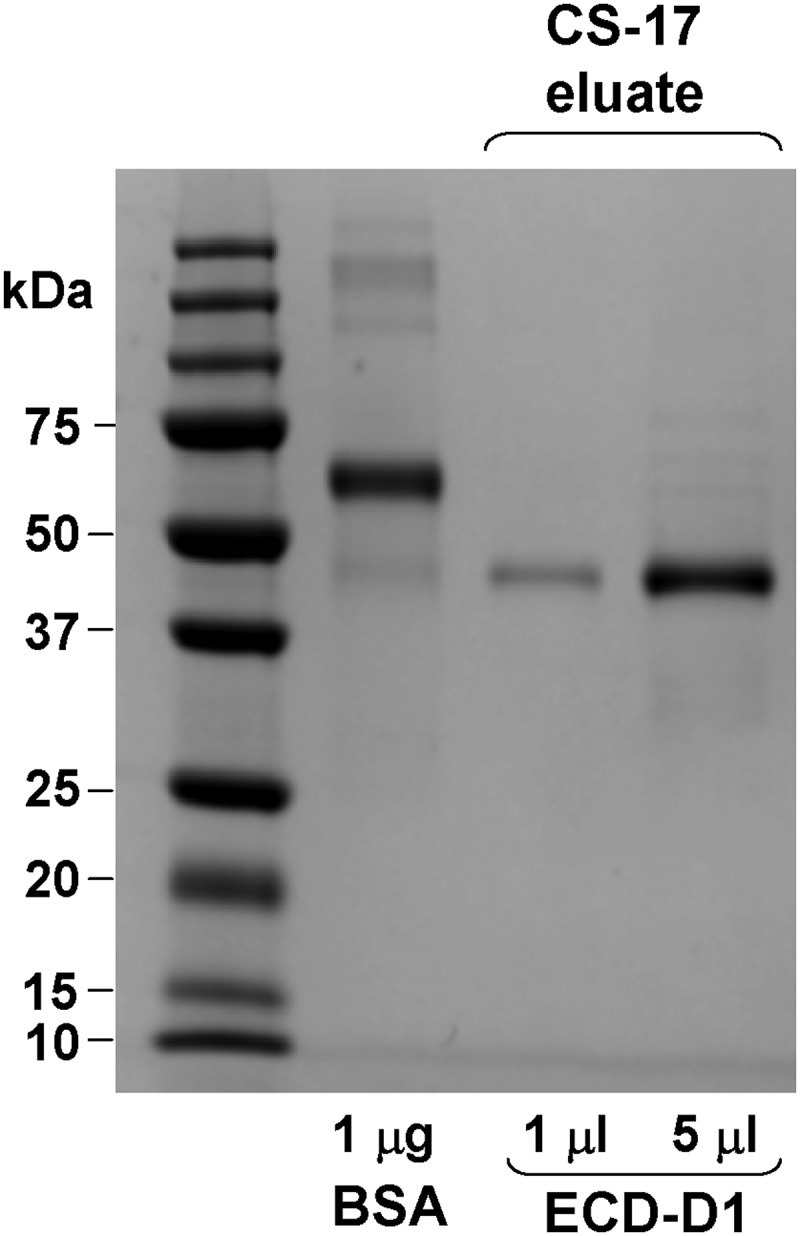

Purification of the TSHR ECD was not straightforward. Despite the presence of 6-His residues at the C terminus, no specific protein was extracted from conditioned medium using a monoclonal anti-5H antibody affinity column or nickel-chelating resin, even after numerous modifications, including variation in imidazole concentration and initial removal of albumin with Affi-Gel blue. Anion exchange chromatography at various pH levels failed to provide an initial, relatively selective capture of the ECD, with complete overlap in elution of the ECD as detected by ELISA and the bulk of serum proteins in the culture medium (data not shown). Finally, we generated an affinity column with TSHR mAb CS-17 whose epitope is primarily to the LRD (31). Fortunately, as determined by PAGE, this mAb captured the TSHR ECD from conditioned culture medium in a single step to more than 90% purity with a yield of 0.1–0.3 mg/L in different preparations, typically approximately 0.2 mg/L (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

One step affinity purification of TSHR ECD-D1. Medium harvested from High Five cells infected for 3 days with baculovirus expressing TSHR ECD-D1 (Figure 1) was applied to a CS-17 mAb affinity column (500 mL of medium in the experiment shown). After washing, material eluted from the column with 0.2M glycine (pH 2.5) was neutralized with 2M Tris-HCl (pH 8) and aliquots (1 and 5 μL) aliquots analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. The data indicate a TSHR ECD-D1 yield of approximately 0.2 mg/L of conditioned medium.

As for the TSHR ECD, initial capture of 6His-tagged HR-D1 protein yielded no product (data not shown) despite detection by ELISA of significant quantities in conditioned medium (Figure 2). However, anion exchange chromatography was more successful for HR-D1 region than for the ECD. Using DEAE-Sepharose, the HR at pH 8 (calculated isoelectric point 6.3) could be captured from a large volume of medium with a peak elution on a NaCl gradient not entirely coincident with the large nonspecific protein peak (data not shown). Subsequent HR-D1 affinity purification with an anti-5H-Sepharose column (but not with Nickel-chelating resin) for the first time permitted visualization of HR protein on PAGE (Figure 6, left panel). After dialysis and concentration, a final Superdex-75 polishing step yielded HR protein of high purity but with very low yield (recovery of ∼50 μg/L conditioned medium) (Figure 6, right panel).

Figure 6.

Multistep purification of TSHR HR. Partial purification and capture of HR-D1 was accomplished by DEAE ion-exchange chromatography with a NaCl gradient. Fractions containing HR-D1 protein as detected by ELISA revealed no specific band of the expected size on SDS-PAGE (data not shown). A, The HR-D1 containing fractions were pooled and applied to an anti-5H mAb affinity column. Reducing SDS-PAGE of proteins eluted from the column revealed partial purification of HR-D1 with an estimated yield of approximately 0.25 mg/L in a typical preparation. B, After dialysis, concentration and application to a Superdex-75 gel filtration column, HR-D1 protein was relatively pure, but with only approximately 20% recovery from the previous step. Variations in dialysis, concentration and gel filtration buffer conditions did not increase the yield.

Discussion

For nearly 20 years, investigators, including ourselves, have attempted to generate recombinant TSHR ECD protein suitable for structural studies. This goal was met, in part, for the LRD component of the TSHR ECD, whose crystal structure was solved 8 years ago (14), shortly after that for the FSHR LRD (16). However, the structure of the enigmatic ECD HR component, critical for receptor function, remained elusive. Three years ago, another major attempt to generate conformationally intact TSHR ECD and (presumably as a “back up”) the isolated HR protein in yeast cells was unsuccessful (7). At the same time, our laboratory had begun a new effort (approximately our fourth) to generate these TSHR proteins in insect cells with a strategy based on the hypothesis that the redundant TSHR C-peptide portion of the HR was hindering correct folding of the proteins. Indeed, as described in the present report, this approach did, finally, succeed. Our data clearly show that significant secretion of TSHR ECD and HR protein by insect cells only occurs when residues 317–366 are deleted. The rationale for generating the isolated HR protein was as a backup in the event that generation of the full ECD failed.

Three years ago, the crystal structure of the full FSHR ECD protein generated in insect cells was reported (17), revealing for the first time the structure of a GPHR HR. Why, in contrast to many attempts to generate conformationally intact TSHR ECD, was FSHR generation successful? We suggest that an important factor is that the HR of the FSHR (and the LH receptor) lacks the equivalent of the TSHR C-peptide region. Nevertheless, success for the FSHR ECD does not diminish the need to crystallize the TSHR ECD with its HR, for a number of reasons. First, there is relatively poor homology between the HRs of the TSHR and FSHR, including a 49-amino acid residue insertion (50 residues relative to the LH receptor). Second, as mentioned above, the TSHR is unique among the GPHR in undergoing intramolecular cleavage within the HR into A- and B-subunits, a phenomenon likely to contribute to the development of Graves' disease (33, 34). Third, the mechanism by which TSAb activate the TSHR is different to that of the glycoprotein hormones (17–19). Finally, besides its role in intramolecular cleavage, the TSHR HR contributes to a greater extent in TSH binding than that of the FSHR hinge in FSH binding. Thus, although FSH binds with high affinity to the isolated FSHR LRD lacking the HR (for example Ref. 16), the TSH binding affinity for the isolated TSHR LRD is too low to permit experimental detection (13).

Regarding purification of our TSHR material secreted by insect cells, we focused initially on the isolated HR because we thought the likelihood of success was greater than for the full ECD. However, purification of this material proved to be problematic. Successive ion-exchange capture, C-terminal His-tag affinity purification and a final gel filtration polishing step did lead to excellent HR purity (Figure 6), but with a very low yield, for which reason we subsequently turned to the full TSHR ECD. To our surprise, purification of the TSHR ECD was more straightforward, with approximately 90% purity obtained by a single pass over a TSHR mAb CS-17 affinity column (Figure 5). However, in contrast to the TSHR ECD in conditioned medium, TSH binding to the purified ECD was greatly diminished, possibly consequent to the formation of multimers that obscure the ligand binding site (35). Because of this unexpected difficulty and because the crystal structures of the TSHR LRD (14, 15), FSHR LRD (16), and FSHR ECD (17) have only been reported in complex with ligands and not as isolated proteins, it is likely that the TSHR ECD will require complexing with a ligand before purification.

In summary, we report that deletion of the redundant C-peptide region overcomes the long-standing obstacle to generating conformationally intact TSHR ECD in insect cells. Future structural studies on this material will require formation of a complex with a high affinity ligand such as a monoclonal TSHR antibody.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant DK-19289.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- DEAE

- diethylaminoethyl

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- FSHR

- FSH receptor

- GPHR

- glycoprotein hormone receptor

- HR

- hinge region

- LRD

- leucine-rich repeat domain

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- PAGE

- polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TSAb

- thyroid stimulating antibody

- TSHR

- TSH receptor.

References

- 1. Van Durme J, Horn F, Costagliola S, Vriend G, Vassart G. GRIS: glycoprotein-hormone receptor information system. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2247–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kreuchwig A, Kleinau G, Kreuchwig F, Worth CL, Krause G. Research resource: update and extension of a glycoprotein hormone receptors web application. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:707–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parmentier M, Libert F, Maenhaut C, et al. Molecular cloning of the thyrotropin receptor. Science. 1989;246:1620–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nagayama Y, Kaufman KD, Seto P, Rapoport B. Molecular cloning, sequence and functional expression of the cDNA for the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1989;165:1184–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Misrahi M, Loosfelt H, Atger M, Sar S, Guiochon-Mantel A, Milgrom E. Cloning, sequencing and expression of human TSH receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1990;166:394–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rapoport B, Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC, McLachlan SM. The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: interaction with TSH and autoantibodies. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:673–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kleinau G, Mueller S, Jaeschke H, et al. Defining structural and functional dimensions of the extracellular thyrotropin receptor region. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22622–22631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Da Costa CR, Johnstone AP. Production of the thyrotropin receptor extracellular domain as a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein and its interaction with thyrotropin and autoantibodies. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11874–11880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costagliola S, Khoo D, Vassart G. Production of bioactive amino-terminal domain of the thyrotropin receptor via insertion in the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornelis S, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Panneels V, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Purification and characterization of a soluble bioactive amino-terminal extracellular domain of the human thyrotropin receptor. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9860–9869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Furmaniak J, Hashim FA, Buckland PR, et al. Photoaffinity labelling of the TSH receptor on FRTL5 cells. FEBS Lett. 1987;215:316–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Loosfelt H, Pichon C, Jolivet A, et al. Two-subunit structure of the human thyrotropin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3765–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Engineering the human thyrotropin receptor ectodomain from a non-secreted form to a secreted, highly immunoreactive glycoprotein that neutralizes autoantibodies in Graves' patients' sera. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18959–18965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sanders J, Chirgadze DY, Sanders P, et al. Crystal structure of the TSH receptor in complex with a thyroid-stimulating autoantibody. Thyroid. 2007;17:395–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanders P, Young S, Sanders J, et al. Crystal structure of the TSH receptor (TSHR) bound to a blocking-type TSHR autoantibody. J Mol Endocrinol. 2011;46:81–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang X, Liu H, Chen X, et al. Structure of follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with the entire ectodomain of its receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12491–12496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosugi S, Ban T, Akamizu T, Kohn LD. Site-directed mutagenesis of a portion of the extracellular domain of the rat thyrotropin receptor important in autoimmune thyroid disease and nonhomologous with gonadotropin receptors. Relationship of functional and immunogenic domains. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19413–19418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costagliola S, Panneels V, Bonomi M, et al. Tyrosine sulfation is required for agonist recognition by glycoprotein hormone receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:504–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chazenbalk GD, Tanaka K, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. On the functional importance of thyrotropin receptor intramolecular cleavage. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4516–4520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamidi S, Chen CR, Mizutori-Sasai Y, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Relationship between thyrotropin receptor hinge region proteolytic posttranslational modification and receptor physiological function. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chazenbalk GD, Tanaka K, Nagayama Y, et al. Evidence that the thyrotropin receptor ectodomain contains not one, but two, cleavage sites. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2893–2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Bernard S, Misrahi M, Huet JC, et al. Sequential cleavage and excision of a segment of the thyrotropin receptor ectodomain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morshed SA, Ando T, Latif R, Davies TF. Neutral antibodies to the TSH receptor are present in Graves' disease and regulate selective signaling cascades. Endocrinology. 2010;151:5537–5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wadsworth HL, Chazenbalk GD, Nagayama Y, Russo D, Rapoport B. An insertion in the human thyrotropin receptor critical for high affinity hormone binding. Science. 1990;249:1423–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnstone AP, Cridland JC, Da Costa CR, Nussey SS, Shepherd PS. A functional site on the human TSH receptor: a potential therapeutic target in Graves' disease. Clin Endocrinol. 2003;59:437–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chazenbalk GD, Wang Y, Guo J, et al. A mouse monoclonal antibody to a thyrotropin receptor ectodomain variant provides insight into the exquisite antigenic conformational requirement, epitopes and in vivo concentration of human autoantibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:702–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chazenbalk GD, McLachlan SM, Pichurin P, Yan XM, Rapoport B. A prion-like shift between two conformational forms of a recombinant thyrotropin receptor A-subunit module: purification and stabilization using chemical chaperones of the form reactive with Graves' autoantibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1287–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen CR, Salazar LM, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. The thyrotropin receptor hinge region as a surrogate ligand: identification of loci contributing to the coupling of thyrotropin binding and receptor activation. Endocrinology. 2012;153:5058–5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen CR, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Suppression of thyrotropin receptor constitutive activity by a monoclonal antibody with inverse agonist activity. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2375–2382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen CR, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Identification of key amino acid residues in a thyrotropin receptor monoclonal antibody epitope provides insight into its inverse agonist and antagonist properties. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3427–3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nagayama Y, Nishihara E, Namba H, Yamashita S, Niwa M. Identification of the sites of asparagine-linked glycosylation on the human thyrotropin receptor and studies on their role in receptor function and expression. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:404–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen CR, Pichurin P, Nagayama Y, Latrofa F, Rapoport B, McLachlan SM. The thyrotropin receptor autoantigen in Graves disease is the culprit as well as the victim. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1897–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mizutori Y, Chen CR, Latrofa F, McLachlan SM, Rapoport B. Evidence that shed thyrotropin receptor A subunits drive affinity maturation of autoantibodies causing Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:927–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen CR, Hubbard PA, Salazar LM, McLachlan SM, Murali R, Rapoport B. Crystal structure of a TSH receptor monoclonal antibody: insight into Graves' disease pathogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29:99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]