Abstract

Objectives: Research is essential to the advancement of pharmacy practice and healthcare. Pharmacists have a pivotal role to play in this strategy. However, there is a paucity of data about hospital pharmacists’ competence and ability in conducting health-related research. This study primarily aims to determine the research demographics of hospital pharmacists in Qatar and to assess the pharmacists’ perceptions of their competence and confidence to conduct research.

Methods: A multi-centered survey using a 70-item piloted questionnaire was conducted among a randomly selected sample of pharmacists practicing at seven Hamad Medical Corporation-managed hospitals. Both descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were applied using IBM-SPSS® version 20.

Key findings: A total of 120 participants responded to the survey (67% response rate). About 70% of the participants did not have any previous research experience. At least 20% of the respondents self-reported inadequate competence and/or confidence in developing research protocols, critically appraising the literature, undertaking and applying appropriate statistical techniques, and interpreting research findings. The level of education along with the current hospital of practice had significant effects on pharmacists’ self-assessed competence (p < 0.05). Overall, 85% of the participants were interested in pursuing postgraduate studies or research-related training.

Conclusions: A large proportion of hospital pharmacists in Qatar self-assessed themselves as having deficiencies in several domains of research process or competencies, although they recognized the value of research in advancing pharmacy practice. These findings have important implications for developing informal research training programs and promoting the pursuit of formal postgraduate programs to bridge the knowledge gaps found among hospital-practicing pharmacists.

Keywords: Competence, Hospital pharmacists, Pharmacy practice research, Research capacity

1. Introduction

Pharmacy practice, as an important component of healthcare, is rapidly evolving, and research is becoming essential to generate new knowledge for improving the therapeutic use of medicines and overall healthcare outcomes (Bond, 2006; Peterson et al., 2009; Kritikos et al., 2013). Research also serves as the bedrock for evidence-based pharmacy practice (Bond, 2006; Peterson et al., 2009). Therefore, having pharmacists who are competent in the delivery of pharmaceutical care and who possess the skills to conduct research is critical because their roles in direct patient care and research is rapidly advancing (Schwartz, 1986; Hepler and Strand, 1990; Holland and Nimmo, 1999; Schumock et al., 2003; Bond, 2006; Dowling et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Poloyac et al., 2011). Likewise, pharmacy practice in Qatar and other Middle Eastern countries is rapidly evolving (Kheir et al., 2009; Kheir and Fahey, 2011; Zaidan et al., 2011). However, there is a lack of empirical evidence to demonstrate the parallel advancement of pharmacists in terms of capacity and involvement in health-related research activities. In spite of a societal need for pharmacist–researchers to advance pharmacy practice, establish new roles and services, and improve healthcare outcomes, some challenges exist that may hamper the attainment of these goals (Davies et al., 1993; Fagan et al., 2006; Saini et al., 2006; Armour et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Smith, 2010). These challenges include ensuring an adequately trained pharmacy workforce, obtaining research funds, and having protected time for research (Saini et al., 2006; Dowling et al., 2009; Peterson et al., 2009; Poloyac et al., 2011).

As part of the mission and goals of pharmacy education, academic degree programs should provide sufficient exposure and prepare pharmacy graduates to conduct practice-based research and scholarly activities. Historically, a minority of undergraduate pharmacy degree programs included formal research education and training as requirements for graduation (Nahata, 2002; American College of Clinical Pharmacy Research Affairs Committee, 2007; Knapp et al., 2011). Furthermore, studies have shown that the number of individuals in the pharmacy workforce with demonstrated capacity for independent research is too small, the number of programs to train such individuals is too few, and the research output from pharmacists is generally too little (Schwartz, 1986; Davies et al., 1993; Ellerby et al., 1993; Rosenbloom et al., 2000; Nahata, 2002; Saini et al., 2006; Armour et al., 2007). In contrast, pharmacy schools and colleges have developed numerous postgraduate programs over the years to provide alternative training opportunities to help meet the needs of pharmacy graduates.

Despite the increased awareness among pharmacists and other health care professionals about the preparations required to seek and succeed in a research career (Blouin et al., 2007; Dowling et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Poloyac et al., 2011), few pharmacists, especially among those practicing in a busy hospital environment, have the opportunity to join formal graduate programs that boost research capacity. Moreover, previous studies have documented that community pharmacists are ill-equipped in terms of pharmacy practice-related research skills and knowledge (Ellerby et al., 1993; Liddell, 1996; Rosenbloom et al., 2000; Saini et al., 2006; Armour et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2009). However, data about the ability and competence of hospital-based pharmacists on practice-related research have not been widely documented. It is also hard to quantify the research productivity of hospital pharmacists in an environment where data are generally limited. Is the Qatar hospital pharmacy workforce adequately trained and prepared to face the current challenges of and quest for cutting-edge health-related research? In an effort to determine where the pharmacy workforce lies in this equation, a nationwide multi-centered study was conducted.

This study aims to (1) explore the research backgrounds and productivity of hospital-practicing pharmacists in Qatar, (2) determine their self-reported competence and confidence towards conducting pharmacy practice and health-related research, and (3) examine their preferences for training programs to build their research capacities and meet the future needs of the profession.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A cross-sectional descriptive study using a 70-item piloted questionnaire was conducted among hospital-practicing pharmacists in Qatar between February and May of 2012. Ethical approval was obtained from the Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) Medical Research Committee and the Qatar University Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Study setting and participants

This was a multi-centered survey involving pharmacists practicing in seven public hospitals under the auspices of HMC, the predominant public healthcare organization in Qatar. The hospitals were: Hamad General Hospital, National Center for Cancer Care and Research, the National Heart Hospital, the Women’s Hospital, Al-Wakra Hospital, Al-Khor Hospital, and Al-Rumailah Hospital. Inclusion criteria for potential respondents included: (1) being a registered pharmacist in Qatar; (2) currently working as a hospital pharmacist; and (3) working in a public hospital for at least 12 months.

2.3. Sample identification and recruitment

The minimum sample size for the study was approximately 140, but we targeted 180 pharmacists to account for non-response. The technique of stratified random sampling proportionate to size was applied to ensure that a representative sample of the target population was obtained. The number of questionnaires to be distributed within each hospital was proportionally determined based on the number of pharmacists practicing at each site. We acquired a sampling frame for this study (n = 312) from an updated electronic database of all pharmacists practicing in different sectors in Qatar, which was verified by an updated list of pharmacists obtained from each hospital. The list of pharmacists from each hospital was alphabetically and serially ordered. Thereafter, a proportionate sample was determined for each hospital using an online computer-generated random number program.

2.4. The survey instrument development

The questionnaire used in this study was developed with reference to published literature pertaining to pharmacy practice research activities and core competencies (Davies et al., 1993; Ellerby et al., 1993; Liddell, 1996; Rosenbloom et al., 2000; Saini et al., 2006; Armour et al., 2007; Blouin et al., 2007; Draugalis et al., 2008; Dowling et al., 2009; Peterson et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Smith, 2010; Poloyac et al., 2011), as well as consultation with experienced pharmacy practice researchers and a sample of the target population (licensed hospital pharmacists). The tool was not previously used in other studies, but the pool of core competencies and elements for pharmacy practice research were largely drawn from our previous experiences of conducting workshops on research methodology and biostatistics. The questionnaire was comprised of three major sections of items assessing: (1) the respondents’ demographics and backgrounds in research activities; (2) their competence and confidence in planning and conducting research; and (3) their preferences for capacity building and formal postgraduate training. The developed questionnaire was tested for face and content validity by two faculty members with extensive experience and expertise in conducting research and developing survey instruments. The readability, clarity and completion time of the modified survey were determined among 20 randomly selected hospital pharmacists (approximately three pharmacists from each of the seven participating hospitals) who were eventually excluded from data analysis. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the competence and confidence domains were determined to be 0.98 and 0.97, respectively.

2.5. Data collection and questionnaire administration

The questionnaires were distributed during different working shifts to the randomly selected pharmacists whose names were initially identified. The survey was anonymous and voluntary. Upon fulfillment of the eligibility criteria, each identified participant was handed out a hardcopy of the questionnaire by the researchers after having signed a written informed consent. Participants were given the choice to fill-in the questionnaires at the time they were distributed to them or to return them later by hand. Reminders were sent to non-respondents after 2 and 4 weeks from the initial mass distribution using a general mailing list.

2.6. Data analyses

The data collected were analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS® Software), version 20. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were applied for data analyses. All categorical variables including respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, items assessing competence and confidence on research activities and processes, and other attitudinal items are expressed as frequencies and percentages. The influence of the respondents’ demographic and professional characteristics on competence and confidence was tested using Chi Square or Fishers Exact tests as appropriate. The level of significance was set a priori at p ⩽ 0.05.

3. Results

Overall, a total of 120 pharmacists from seven major public hospitals in Qatar responded to the survey (67% response rate), with the majority (74%) holding a baccalaureate degree in pharmacy as the highest achieved level of pharmacy education. A large proportion of the respondents (40%) obtained their first professional degree in pharmacy from Egypt, while only 5% of them graduated from Qatar. Approximately 76% of the pharmacists surveyed have spent 10 years or less in hospital pharmacy practice. Table 1 provides detailed information on the demographic characteristics of the studied group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of hospital pharmacists in Qatar (n = 120).

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 60 (50) |

| Female | 60 (50) |

| Age in years | |

| 21–30 | 42 (35) |

| 31–40 | 59 (49.2) |

| 41–50 | 16 (13.3) |

| More than 50 | 3 (2.5) |

| Country of getting first professional pharmacy degree | |

| Egypt | 48 (40) |

| India | 7 (5.8) |

| Jordan | 20 (16.7) |

| Palestine | 2 (1.7) |

| Qatar | 6 (5) |

| Sudan | 15 (12.5) |

| Others | 22 (18.3) |

| Highest degree achieved⁎ | |

| Bachelors degree (e.g. B. Pharm, B.Sc. Pharm) | 88 (73.9) |

| Doctor of pharmacy (e.g. PharmD) | 5 (4.2) |

| Masters degree (e.g. MS, M.Sc., MPharm, MBA) | 16 (13.4) |

| Other | 10 (8.4) |

| Number of years spent in pharmacy practice | |

| 5 years or less | 36 (30) |

| 6–10 years | 29 (24.2) |

| 11–15 years | 32 (26.7) |

| More than 15 years | 23 (19.2) |

| Number of years spent as hospital pharmacist | |

| 5 years or less | 61 (50.8) |

| 6–10 years | 30 (25) |

| 11–15 years | 23 (19.2) |

| More than 15 years | 6 (5) |

| Hospital currently working at | |

| National Center for Cancer Care and Research | 16 (13.3) |

| Heart Hospital | 9 (7.5) |

| Women’s Hospital | 22 (18.3) |

| Hamad General Hospital | 47 (39.2) |

| Al-Wakra Hospital | 10 (8.3) |

| Al-Khor Hospital | 10 (8.3) |

| Al-Rumailah Hospital | 6 (5) |

One missing data.

Information on the general research background, research experience and interests of the studied hospital pharmacists is displayed in Table 2. Approximately 70% of them admitted to not having any previous experience in conducting research. However, 73% have had research-related training in the form of seminars or workshops. When further investigated, more than 75% of the hospital pharmacists were very interested or extremely interested in conducting and learning about conducting pharmacy practice-related research. When asked about their overall ability to design and conduct pharmacy practice or health-related research, 44% agreed that they had either very good or excellent abilities in undertaking research endeavors. Notably, approximately 70% of the hospital pharmacists surveyed had not published any peer-reviewed articles in a scientific journal within the last 5 years and that more than 75% of the participants had no record of any poster presentations or published abstracts in an international conference during the same timeframe.

Table 2.

Research background and interests of hospital pharmacists in Qatar (n = 120).

| Parameter | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Previous research experience | |

| Yes | 37 (30.8) |

| No | 83 (69.2) |

| Previous research related training during undergraduate, postgraduate or during job§ | |

| No training obtained | 45 (37.5) |

| Workshop | 54 (45) |

| Seminar | 33 (27.5) |

| Specialized short course (1–6 months) | 26 (21.7) |

| Others | 8 (6.4) |

| Interest in conducting health-related research | |

| Not interested at all | 3 (2.5) |

| Not very interested | 2 (1.7) |

| Somewhat interested | 24 (20) |

| Very interested | 49 (40.8) |

| Extremely interested | 42 (35) |

| Interest in learning about conducting health-related research⁎ | |

| Not interested at all | 3 (2.5) |

| Not very interested | 4 (3.3) |

| Somewhat interested | 19 (15.8) |

| Very interested | 51 (42.5) |

| Extremely interested | 42 (35) |

| Overall ability to design and conduct health-related research | |

| Poor | 6 (5) |

| Fair | 20 (16.7) |

| Good | 41 (34.2) |

| Very good | 41 (34.2) |

| Excellent | 12 (10) |

| Involvement in research as a subject or a respondent | |

| Never | 37 (30.8) |

| Sometimes | 41 (34.2) |

| Often | 22 (18.3) |

| Usually | 10 (8.3) |

| Always | 10 (8.3) |

| Involvement in research as a principal investigator or co-investigator | |

| Never | 69 (57.5) |

| Sometimes | 28 (23.3) |

| Often | 12 (10) |

| Usually | 7 (5.8) |

| Always | 4 (3.3) |

| Number of peer-reviewed journal articles published within the last 5 years | |

| 0 | 83 (69.2) |

| 1–3 | 29 (24.1) |

| ⩾4 | 8 (6.6) |

| Number of peer-reviewed posters and/or abstracts in local/regional conference since last 5 years | |

| 0 | 75 (62.6) |

| 1–3 | 38 (31.7) |

| ⩾4 | 7 (5.8) |

| Number of peer-reviewed posters and/or abstracts in international conference since last 5 years | |

| 0 | 92 (76.7) |

| 1–3 | 25 (20.8) |

| ⩾4 | 3 (2.4) |

Respondents were allowed to choose more than one option.

One missing data.

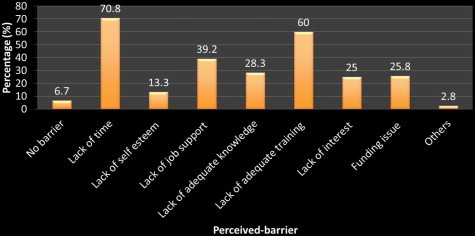

Consistent with the findings above, approximately one-third of the informants indicated that the job-related or continuing professional development-related research trainings they received had inadequately prepared them for research. In addition, respondents were asked to indicate what they perceived as barriers to conducting research (Fig. 1). Lack of time (71%), lack of adequate training (60%), lack of job support (39%), and inadequate knowledge (28%) were the barriers to conducting research most commonly reported by the hospital pharmacists.

Figure 1.

Pharmacists identified barriers to research (n = 120). Note: Respondents were allowed to choose more than one option.

We subjectively assessed the research capabilities of the studied cohort by asking respondents to rate how competent and confident they perceived themselves in performing different aspects of designing, conducting, and analyzing research using a five-point semantic-differential scale. The relevant data are presented in Tables 3a and 3b. An overwhelming majority of the hospital pharmacists (at least 85%) rated themselves as moderately to extremely competent and confident in conceiving research ideas, including needs-driven ideas such as work-related needs and opportunity-driven ideas such as industry-sponsored study. Similarly, a large proportion (more than 80%) of the participants believed that they were competent and confident in searching the literature efficiently, collecting relevant data using pre-planned data collection forms, summarizing the data in tables and/or charts, and preparing an oral or a poster presentation (Tables 3a and 3b).

Table 3a.

Self-perceived competence of hospital pharmacists in planning and conducting research (n = 120).

| Research competence domain | Frequency (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely competent | Very competent | Moderately competent | Not very competent | Not competent at all | |

| Conception of research idea# | 16 (13.3) | 33 (27.5) | 53 (44.2) | 11 (9.2) | 5 (4.2) |

| Searching the literature efficiently | 17 (14.2) | 35 (29.2) | 47 (39.2) | 15 (12.5) | 6 (5) |

| Critically reviewing research literature | 7 (5.8) | 35 (29.2) | 54 (45) | 18 (15) | 6 (5) |

| Formulating research hypotheses and research questions | 7 (5.8) | 33 (27.5) | 52 (43.3) | 19 (15.8) | 9 (7.5) |

| Proposing appropriate study designs or methods# | 7 (5.8) | 28 (23.3) | 57 (47.5) | 18 (15) | 8 (6.7) |

| Writing research proposal or developing a protocol | 7 (5.8) | 34 (28.3) | 42 (35) | 26 (21.7) | 11 (9.2) |

| Defining target population, sample and eligibility criteria€ | 13 (10.8) | 34 (28.3) | 42 (35) | 24 (20) | 6 (5) |

| Determine appropriate sample size | 4 (3.3) | 31 (25.8) | 48 (40) | 29 (24.2) | 8 (6.7) |

| Choosing an appropriate sampling technique (e.g. random sampling) | 6 (5) | 26 (21.7) | 60 (50) | 20 (16.7) | 8 (6.7) |

| Determining outcome measures (variables to measure) | 7 (5.8) | 26 (21.7) | 48 (40) | 32 (26.7) | 7 (5.8) |

| Ethical considerations€ | 7 (5.8) | 26 (21.7) | 45 (37.5) | 28 (23.3) | 13 (10.8) |

| Outlining detailed statistical plans to be used in data analyses€ | 13 (10.8) | 28 (23.3) | 48 (40) | 26 (21.7) | 4 (3.3) |

| Designing a data collection form | 11 (9.2) | 31 (25.8) | 44 (36.7) | 23 (19.2) | 11 (9.2) |

| Developing and validating a study instrument (e.g. questionnaire) | 7 (5.8) | 27 (22.5) | 53 (44.2) | 25 (20.8) | 8 (6.7) |

| Collecting relevant data using preplanned data collection forms | 16 (13.3) | 36 (30) | 46 (38.3) | 15 (12.5) | 7 (5.8) |

| Managing and storing data including data entry into a database | 15 (12.5) | 32 (26.7) | 49 (40.8) | 14 (11.7) | 10 (8.3) |

| Statistical analyses using software (e.g. STATA, SPSS, EpiInfo) | 8 (6.7) | 21 (17.5) | 47 (39.2) | 24 (20) | 20 (16.7) |

| Choosing and applying appropriate “INFERENTIAL” statistical tests and methods€ | 4 (3.3) | 20 (16.7) | 57 (47.5) | 24 (20) | 14 (11.7) |

| Summarizing data in tables or charts | 14 (11.7) | 39 (32.5) | 44 (36.7) | 17 (14.2) | 6 (5) |

| Interpretation of the findings and determining the significance of obtained results | 16 (13.3) | 30 (25) | 48 (40) | 18 (15) | 8 (6.7) |

| Preparing a presentation (oral or poster) | 20 (16.7) | 32 (26.7) | 47 (39.2) | 12 (10) | 9 (7.5) |

| Writing a manuscript for publication in a scientific journal | 13 (10.8) | 27 (22.5) | 42 (35) | 24 (20 | 14 (11.7) |

One missing data.

Two missing data.

Table 3b.

Self-perceived confidence of hospital pharmacists in planning and conducting research (n = 120).

| Research confidence domain | Frequency (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely confident | Very confident | Moderately confident | Not very confident | Not confident at all | |

| Conception of research idea⁎ | 17 (14.4) | 42 (35.6) | 45 (38.1) | 9 (6.7) | 5 (4.2) |

| Searching the literature efficiently | 16 (13.3) | 44 (36.7) | 46 (38.3) | 10 (8.3) | 4 (3.3) |

| Critically reviewing research literature | 7 (5.8) | 38 (31.7) | 59 (49.2) | 11 (9.2) | 5 (4.2) |

| Formulating research hypotheses and research questions | 13 (10.8) | 36 (30) | 47 (39.2) | 17 (14.2) | 7 (5.8) |

| Proposing appropriate study designs or methods | 8 (6.7) | 38 (31.7) | 48 (40) | 19 (15.8) | 7 (5.8) |

| Writing research proposal or developing a protocol¥ | 11 (9.2) | 33 (27.7) | 44 (37) | 24 (20.2) | 7 (5.9) |

| Defining target population, sample and eligibility criteria | 9 (7.5) | 42 (35) | 46 (38.3) | 19 (15.8) | 4 (3.3) |

| Determine appropriate sample size | 8 (6.7) | 40 (33.3) | 44 (36.7) | 20 (16.7) | 8 (6.7) |

| Choosing an appropriate sampling technique (e.g. random sampling) | 10 (8.3) | 35 (29.2) | 51 (42.5) | 16 (13.3) | 8 (6.7) |

| Determining outcome measures (variables to measure) | 10 (8.3) | 37 (30.8) | 46 (38.3) | 22 (18.3) | 5 (4.2) |

| Ethical considerations | 14 (11.7) | 32 (26.7) | 44 (36.7) | 25 (20.8) | 5 (4.2) |

| Outlining detailed statistical plans to be used in data analyses | 5 (4.2) | 38 (31.7) | 46 (38.3) | 21 (17.5) | 10 (8.3) |

| Designing a data collection form | 12 (10) | 43 (35.8) | 40 (33.3) | 19 (15.8) | 6 (5) |

| Developing and validating a study instrument (e.g. questionnaire) | 10 (8.3) | 35 (29.2) | 47 (39.2) | 23 (19.2) | 5 (4.2) |

| Collecting relevant data using preplanned data collection forms | 15 (12.5) | 44 (36.7) | 44 (36.7) | 11 (9.2) | 6 (5) |

| Managing and storing data including data entry into a database | 11 (9.2) | 42 (35) | 43 (35.8) | 16 (13.3) | 8 (6.7) |

| Statistical analyses using software (e.g. STATA, SPSS, EpiInfo) | 6 (5) | 29 (24.2) | 51 (42.5) | 20 (16.7) | 14 (11.7) |

| Choosing and applying appropriate “INFERENTIAL” statistical tests and methods¥ | 8 (6.7) | 29 (24.2) | 49 (40.8) | 24 (20) | 9 (6.7) |

| Summarizing data in tables or charts¥ | 20 (16.8) | 34 (28.6) | 42 (35.3) | 17 (14.3) | 6 (5) |

| Interpretation of the findings and determining the significance of obtained results | 17 (14.2) | 34 (28.3) | 43 (35.8) | 19 (15.8) | 7 (5.8) |

| Preparing a presentation (oral or poster) | 19 (15.8) | 43 (35.8) | 37 (30.8) | 12 (10) | 9 (7.5) |

| Writing a manuscript for publication in a scientific journal | 11 (9.2) | 35 (29.2) | 41 (34.2) | 21 (17.5) | 12 (10) |

One missing data.

Two missing data.

However, a considerable proportion of the participants rated themselves as not at all or not very competent and confident in several aspects of the research process. For instance, 20–30% of the respondents self-reported inadequate competence and confidence in formulating a research question or hypothesis (inadequate competence, 23%; inadequate confidence, 20%), determining an appropriate study design and methods (inadequate competence, 22%; inadequate confidence, 22%), determining sample size (inadequate competence, 31%; inadequate confidence, 23%), selecting an appropriate sampling technique (inadequate competence, 23%; inadequate confidence, 20%), and developing a research proposal or protocol (inadequate competence, 31%; inadequate confidence, 26%). The pharmacists also admitted having deficiencies in conducting statistical analyses using software packages such as STATA, SPSS, and EpiInfo (37% were incompetent), as well as in applying appropriate inferential statistical tests (32% were incompetent). The same was the case for abilities in writing scientific manuscripts, for which the respondents rated themselves as not being competent (32%) and confident (28%).

Further analyses were conducted to investigate the influence of the pharmacists’ characteristics on their self-assessed competence and confidence. The highest level of education along with current hospital of practice had a significant influence (p < 0.05) on the hospital pharmacists’ self-assessed competence in several domains. Overall, 85% of the participants were interested in pursuing post-graduate studies (Table 4). Nearly one-third (n = 39; 33%) of the participants were interested in pursuing a PharmD degree, whereas 43% (n = 52) were interested in M.Sc. or Ph.D. degrees (Table 4). Participants indicated interest in various research domain areas of pharmacy practice and pharmaceutical sciences, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pharmacists’ interest in postgraduate studies (n = 120).

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Interest in postgraduate studies⁎ | |

| Not interested | 18 (15%) |

| PharmD | 39 (32.5%) |

| Residency and/or fellowship | 5 (4.2%) |

| Master | 42 (35%) |

| Ph.D. | 10 (8.3) |

| Others | 3 (2.5%) |

| Area of interest in clinical pharmacy and practice | |

| Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety | 11 (9.2%) |

| Pharmacoeconomics | 8 (6.7%) |

| Pharmacotherapeutics research | 41 (34.2%) |

| Social and behavioral aspects of life | 10 (8.3%) |

| Clinical outcome research | 17 (14.2%) |

| Direct patient care | 33 (27.5%) |

| Others | 1 (0.8%) |

| Area of interest in pharmaceutical sciences | |

| Pharmaceutics | 5 (4.2%) |

| Pharmacokinetics | 2 (1.7%) |

| Pharmacogenomics | 0 (0%) |

| Medicinal chemistry | 0 (0%) |

| Pharmacology | 6 (5%) |

| Pharmacognosy | 1 (0.8%) |

| Others | 1 (0.8%) |

Three missing data.

4. Discussion

Although a large proportion (greater than three-quarters) of the hospital practicing pharmacists in Qatar have expressed interest in conducting and learning about conducting health-related research, they admitted to lacking previous experience in planning and conducting research. The majority of the pharmacists surveyed also reported no evidence of recent involvement in research activities. Research is needed in order to advance education, practice and decision-making. Often what is needed is local evidence that illustrates the need for a new service or different method of service delivery (Bond, 2006; Peterson et al., 2009). In general, several studies from around the globe have demonstrated reluctance among pharmacists for participating in practice and health-related research activities (Ellerby et al., 1993; Liddell, 1996; Rosenbloom et al., 2000; Bond, 2006; Saini et al., 2006; Armour et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2009). This could partly be explained by the fact that research is not a mandate for hospital pharmacists or a requirement for preregistration training in Qatar and many countries globally. Furthermore, informal postgraduate training programs such as pharmacy residency and fellowship programs are currently not available in Qatar or other Middle Eastern countries. This raises questions about whether the current pharmacy curricula in the countries where the hospital pharmacists graduated adequately prepare graduates to be competent in research and scholarly activities. We were unable to determine the extent of research training in the pharmacy curricula of the Middle East region from a study that extensively reported about pharmacy education and practice in 13 Middle Eastern countries (Kheir et al., 2009). The American College of Clinical Pharmacy and other scholars have highlighted the need for the involvement of pharmacists in clinical and practice-related research and have proposed core competencies and training requirements for pharmacist–researchers (Bond, 2006; Blouin et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2009; Poloyac et al., 2011).

A recent study aimed at describing the views and attitudes of pharmacists towards pharmacy practice research in Qatar revealed that the pharmacists had positive attitudes towards research, they generally agreed that it was a professional responsibility to be involved in research and that it is important to establish an evidence-base to support practice (Elkassem et al., 2013). In recent years, the professional scope of pharmacy practice has undergone a major transformation globally and research plays an important role in underpinning evidence-based practice. Among other things, the mission of pharmacy degree programs is to prepare graduates to provide optimal pharmaceutical care, advance health care outcomes, and promote research and scholarly activities (College of Pharmacy; Knapp et al., 2011). Therefore, pharmacists in hospitals and other settings should strive to improve the quality of existing cognitive services and to develop new ones through research evidence (Davies et al., 1993; Bond, 2006; Armour et al., 2007; Blouin et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Knapp et al., 2011; Poloyac et al., 2011). They should also contribute to other health services research in collaboration with other health care professionals. In some parts of the world, hospital pharmacists, especially those with clinical training and affiliations, are increasingly becoming more involved in collaborative research as part of their career development (Fagan et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2009; Knapp et al., 2011). This facilitates keeping up to date with, and contributing to, research and developments within the profession.

Despite the fact that the surveyed hospital pharmacists have reported possession of previous research-related training in the form of seminars or workshops, many of them have reported that they have inadequate (fair to poor) abilities in designing and conducting practice-related research. While the current study was unable to determine the content and depth of the training courses undertaken by the pharmacists, the content and intensive nature of such training programs would determine if the pharmacists have gained sufficient exposure to the core competencies required to be successful in research. The methods to train individuals for skills to conduct pharmacy practice as well as clinical and translational research have been extensively discussed in the literature (Blouin et al., 2007; Dowling et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009; Knapp et al., 2011; Poloyac et al., 2011). Therefore, this delineates the needs for informal in-service training programs to strengthen research competencies and capacities of hospital-bound pharmacists. Furthermore, the curricula of undergraduate pharmacy schools have an important influence on hospital pharmacists’ capabilities and attitudes towards practice research. Such curricula should provide opportunities for stimulating research interests and cultivating positive attitudes towards research through comprehensive research training modules and the completion of pharmacy practice-based research projects (Kritikos et al., 2013).

In general, the pharmacists admitted to lacking competence and confidence in several aspects of research including developing research protocols, critically appraising literature, undertaking and applying appropriate statistical techniques, and interpreting research findings. Consistent with the current findings, a previous study among pharmacists has documented a lack of confidence in their abilities to conduct research in general and an underestimation of what their profession is capable of achieving (Armour et al., 2007). This calls for short- and long-term interventions targeted at practicing pharmacists and pharmacy students to change their mind-set and advocate for the importance of evidence-based practice and the role played by research in achieving this (Armour et al., 2007). There is a clear need for concerted efforts to educate hospital pharmacists and pharmacy students that existing hospital services are products of research and if new services are to be developed, then more research involvement is needed. It is imperative to establish pharmacy practice research networks between academia and other pharmacy practice settings. This would promote research culture and facilitate mentoring, which are essential elements in the training and development of novice researchers (Peterson et al., 2009).

As a reflection of low research and scholarly productivity, the vast majority of the respondents did not publish any peer-reviewed journal articles or present research findings in local or international meetings within the last 5 years. In general, there is very little published data regarding the scientific publishing productivity of pharmacists (Lelièvre et al., 2011). However, our findings are similar to what have been reported by other studies (Schwartz, 1986; Davies et al., 1993; Lelièvre et al., 2011). A study investigating the predictors of publication productivity among hospital pharmacists in Canada and France reported that gender, having academic duties or a Ph.D. degree, having participated in a clinical trial, having secured research funding, and allocating protected time for research were significant predictive factors of the number of publications written by the hospital pharmacists (Lelièvre et al., 2011).

The current findings are consistent with previous studies that have documented a lack of skills and knowledge, financial support or funding, and dedicated time to conduct research as significant potential barriers to participation in research (Davies et al., 1993; Ellerby et al., 1993; Liddell, 1996; Armour et al., 2007; Peterson et al., 2009; Elkassem et al., 2013). Research should be viewed as a mandate for pharmacy practitioners because it is a means of documenting and sharing evidence in the interest of improved healthcare outcomes and the evolving roles of pharmacists (Bond, 2006; Peterson et al., 2009; Elkassem et al., 2013). Pharmacy leaders should strive to support other pharmacists in overcoming these barriers and pharmacists in all care settings should actively engage in research to improve patient outcomes and further develop the profession.

Although this study is among the few that extensively report an inventory of hospital pharmacists’ research activities in the Middle East, the findings are subject to some important limitations. The major limitation is that the assessment of research competence and confidence is highly prone to self-report bias; the pharmacists subjectively self-assessed themselves in terms of research capabilities. Therefore, the findings might be overestimated as a result of potential social desirability bias. Furthermore, there were items that required the pharmacists to recall some historical data, thereby predisposing the findings to recall bias. The sample size was lower than estimated, which has an implication on the external validity of the findings. Therefore, one has to be cautious in generalizing the findings of the current study to all pharmacists.

5. Conclusion

A large proportion of hospital pharmacists in Qatar self-assessed themselves as having deficiencies in several areas of research competencies, particularly in developing research protocols, critically appraising the literature, and applying the appropriate statistical techniques. The findings have important implications for developing informal research training and strong academic mentorship programs to bridge the gaps found among hospital-practicing pharmacists in Qatar. The results suggest that pharmacy educators and curriculum planners should include more extensive course content and experience related to pharmacy practice research in undergraduate curricula. This will increase exposure to research and a research career.

Authors’ contribution

All four authors (AA, DB, RE, and MZ) have contributed significantly to the intellectual content of this study and have adhered to the ICMJE definition of authorship. AA, DB, RE, and MZ have substantially contributed to the conception of the research idea; design of the study; collection, analyses, and interpretation of data; and writing and/or revising the submitted manuscript. All of the authors have complete access to the study data and have read and approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded under the Qatar University Undergraduate Student Research Grant (Number: QUST-CPH-SPR-12-9).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by both the Hamad Medical Corporation Medical Research Committee and the Qatar University Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge the support provided by the following pharmacists for study instrument validation and data collection: Ahmed Satti Al-Zubair, Aisha Al-Sulaiti, Hafeez Olalekan, Imran Khudair, Muna Al-Saadi, Mahmoud Gassim, Mohammad Sidiqi, Rasha Kaddoura, and Yassin Abdulla. The authors also wish to thank all of the hospital pharmacists who voluntarily participated in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- American College of Clinical Pharmacy Research Affairs Committee The research agenda of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(2):312–324. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armour C., Brillant M. Pharmacists’ views on involvement in pharmacy practice research: strategies for facilitating participation. Pharm. Pract. 2007;5(2):59–66. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552007000200002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blouin R.A., Bergstrom R.F. Report of the AACP educating Clinical Scientists Task Force. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007;71(4) (article S05) [Google Scholar]

- Bond C. The need for pharmacy practice research. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2006;14(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- College of Pharmacy, Q.U., 2014. Mission, Vision and Goals. Available from: http://www.qu.edu.qa/pharmacy/mission_vision.php (retrieved 25.01.14.).

- Davies G., Dodds L. Pharmacy practice research in the hospitals of South East Thames regional health authority, England. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 1993;2(3):184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling T.C., Murphy J.E. Recommended education for pharmacists as competitive clinical scientists. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(2):236–244. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draugalis J.R., Coons S.J. Best practices for survey research reports: a synopsis for authors and reviewers. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008;72(1) doi: 10.5688/aj720111. (article 11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkassem W., Pallivalapila A. Advancing the pharmacy practice research agenda: views and experiences of pharmacists in Qatar. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013;35(5):692–696. doi: 10.1007/s11096-013-9802-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerby D.A., Williams A. The level of interest in pharmacy practice research among community pharmacists. Pharm. J. 1993;251:321–322. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan S.C., Touchette D. The state of science and research in clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(7):1027–1040. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.7.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler C.D., Strand L.M. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1990;47(3):533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R.W., Nimmo C.M. Transitions, part 1: beyond pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 1999;56(17):1758–1764. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.17.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp K.K., Manolakis M. Projected growth in pharmacy education and research, 2010 to 2015. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011;75(6) doi: 10.5688/ajpe756108. (article 108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheir N., Fahey M. Pharmacy practice in Qatar: challenges and opportunities. South. Med Rev. 2011;4(2):92–96. doi: 10.5655/smr.v4i2.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheir N., Zaidan M. Pharmacy education and practice in 13 Middle Eastern countries. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2009;72(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7206133. (article 133) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritikos V.S., Carter S. Undergraduate pharmacy students’ perceptions of research in general and attitudes towards pharmacy practice research. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013;21(3):192–201. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7174.2012.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre J., Bussières J.F. Predictors of publication productivity among hospital pharmacists in France and Quebec. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011;75(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe75117. (article 17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddell H. Attitudes of community pharmacists regarding involvement in practice research. Pharm. J. 1996;256:905–907. [Google Scholar]

- Nahata M.C. Clinical research in the pharmacy academy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2002;66(1):84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson G.M., Jackson S.L. Attitudes of Australian pharmacists towards practice-based research. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009;34(4):397–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poloyac S.M., Empey K.M. Core competencies for research training in the clinical pharmaceutical sciences. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2011;75(2) doi: 10.5688/ajpe75227. (article 27) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom K., Taylor K. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards research. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2000;8(2):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Saini B., Brillant M. Factors influencing Australian community pharmacists’ willingness to participate in research projects – an exploratory study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2006;14(3):179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Schumock G.T., Butler M.G. Evidence of the economic benefit of clinical pharmacy services: 1996–2000. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(1):113–132. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.1.113.31910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M.A. Academic pharmacy 1986: are clinical pharmacists meeting the clinical scientist role? Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 1986;50:462–464. [Google Scholar]

- Smith F.J. Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2010. Conducting Your Pharmacy Practice Research Project: A Step-by-step Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.A., Olson K.L. Pharmacy practice research careers. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):1007–1011. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.8.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidan M., Singh R. Physicians’ perceptions, expectations, and experience with pharmacists at Hamad Medical Corporation in Qatar. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2011;4:85–90. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S14326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]