Abstract

Vibrio anguillarum is an important pathogen in marine aquaculture, responsible for vibriosis. Bacteriophages can potentially be used to control bacterial pathogens; however, successful application of phages requires a detailed understanding of phage-host interactions under both free-living and surface-associated growth conditions. In this study, we explored in vitro phage-host interactions in two different strains of V. anguillarum (BA35 and PF430-3) during growth in microcolonies, biofilms, and free-living cells. Two vibriophages, ΦH20 (Siphoviridae) and KVP40 (Myoviridae), had completely different effects on the biofilm development. Addition of phage ΦH20 to strain BA35 showed efficient control of biofilm formation and density of free-living cells. The interactions between BA35 and ΦH20 were thus characterized by a strong phage control of the phage-sensitive population and subsequent selection for phage-resistant mutants. Addition of phage KVP40 to strain PF430-3 resulted in increased biofilm development, especially during the early stage. Subsequent experiments in liquid cultures showed that addition of phage KVP40 stimulated the aggregation of host cells, which protected the cells against phage infection. By the formation of biofilms, strain PF430-3 created spatial refuges that protected the host from phage infection and allowed coexistence between phage-sensitive cells and lytic phage KVP40. Together, the results demonstrate highly variable phage protection mechanisms in two closely related V. anguillarum strains, thus emphasizing the challenges of using phages to control vibriosis in aquaculture and adding to the complex roles of phages as drivers of prokaryotic diversity and population dynamics.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio anguillarum is a marine pathogenic bacterium causing vibriosis, a fatal hemorrhagic septicemia, which contributes to significant mortalities in fish and shellfish aquaculture worldwide (1–3). The persistence of Vibrio pathogens in aquaculture has been attributed to their ability to form biofilms with increased tolerance of disinfectants and antibiotics (4, 5). Moreover, the first stage of infection involves biofilm-like microcolonies in the skin tissue, causing chronic infection (5).

Recently, bacteriophages have been suggested as potential agents of pathogen control in aquaculture, and the controlling effects of phages have been explored for a number of fish pathogens (6–8). Successful application of phages to reduce vibriosis-related mortality has been demonstrated (9, 10). The capabilities of some phages to produce depolymerases, which hydrolyze extracellular polymers in bacterial biofilms, have made the use of bacteriophages particularly relevant in the treatment of biofilm-forming pathogens, as demonstrated in biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11), Escherichia coli (12), and Staphylococcus aureus (13).

Apart from the potential physical and chemical barrier provided by biofilms, the use of bacteriophages to control pathogens is challenged by the development of and selection for phage-resistant or phage-tolerant subpopulations. A broad range of resistance mechanisms have evolved in bacteria (14), and lytic infection of phage-susceptible bacteria has been shown to drive functional and genetic diversification of the host population on the basis of the rapid emergence of phage-resistant mutants (15, 16). A deeper understanding of the temporal and spatial dynamics of phage-biofilm interactions and of the development of phage resistance in these systems is therefore essential for assessing the potential of using phages in disease control.

In this study, we quantified the influence of phages on biofilm formation in two strains of V. anguillarum, both during the initial stages of attachment and microcolony formation and in more-developed biofilms. The results showed large intraspecific differences in the phage-biofilm interactions of two V. anguillarum phage-host systems and revealed the presence of highly different protective mechanisms against phage infection, adding further complexity to the use of phages to control vibriosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and bacteriophages.

Bacteriophages and hosts used in this study are listed in Table 1. Two V. anguillarum strains were used in this study: strain PF430-3, originally isolated from a salmonid aquaculture in Chile (17), and strain BA35, originally isolated from sockeye salmon in the United States (20). Phage KVP40, which infects strain PF430-3, is a broad-host-range phage originally isolated in Japan (18, 19, 45), and phage ΦH20, infecting BA35, was isolated from Danish aquaculture (21).

TABLE 1.

Bacteriophages and hosts

Effects of phages on initial bacterial attachment and microcolony formation.

To quantify the effect of phages on microcolony formation of the two strains, 10 μl of diluted mid-log-phase cultures (106 CFU ml−1) was filtered onto 20+ replicate 25-mm-diameter, 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate filters and incubated on LB agar in 6-well plates (22). Phage stock (2 ml; ca. 108 PFU ml−1) was added to half the filters, the other half serving as controls with addition of 2 ml SM buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 0.01% gelatin). Duplicate filters of the phage-amended reaction mixture and controls were collected every hour for 8 h, transferred to a 25-mm-diameter filtration manifold (Millipore), and stained with 0.5% SYBR gold (Invitrogen) for 10 min, followed by 3 rinses with Milli-Q water. The filters were then mounted on a microscope slide and stored frozen until quantification by epifluorescence microscopy using Cell M image analysis software (Olympus) for determination of colony area.

Phage-biofilm interactions.

Effects of phage ΦH20 and KVP40 on the formation and disruption of V. anguillarum biofilms were monitored for the two strains, BA35 and PF430-3, in two different experimental approaches: In the pretreatment experiment, duplicate sets of polypropylene plastic tubes (Sarstedt) with 5 ml marine broth (MB; Difco) were simultaneously inoculated with 100 μl overnight bacterial culture and 100 μl phage stock (final concentrations, 107 CFU ml−1 and 106 PFU ml−1; multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 0.1). In the posttreatment experiments, the bacteria were allowed to grow in 5 ml MB for 10 days after inoculation to establish a biofilm. After 10 days of incubation, the liquid was removed and the tubes were rinsed with MB. Then, 5 ml MB was added along with 100 μl phage stock (final concentration, 106 PFU ml−1), and the tubes were incubated for another 7 to 8 days.

In both experiments, the tubes were incubated at 30°C and duplicate tubes were removed daily for measurement of biofilm formation and of the density of free-living bacteria and phages. Measurements of optical density at 600 nm (OD600) were used to estimate free-living bacterial abundance, and determination of the phage concentration in the free-living phase was done by plaque assay (23). Biofilms were quantified according to the method described by O'Toole et al. (24) with some modifications. Briefly, the liquid was removed, and tubes were rinsed twice with artificial seawater (ASW; Sigma). Then, 6 ml 0.4% crystal violet (Sigma) was added to each tube and, after 15 min, stain was removed. Tubes were washed with tap water in order to remove excess stain and left to dry for 5 min. A 6-ml volume of 33% acetic acid (Sigma) was added and left for 5 min to allow the stain to dissolve. The absorbance was measured at OD595.

In addition to the measurements described above, we also quantified the biofilm-associated infective phages in the posttreatment experiment after disruption of the biofilm by sonication. First, the liquid was removed and the tube rinsed 3 times with ASW. Then, 6 ml ASW was added to completely cover the biofilm, and the tube was sonicated for 10 s at an amplitude of 80 (Misonix sonication bath) (pulse on for 1 s and pulse off for 1 s) to dislodge bacteria and phages from the biofilm matrix. Serial dilutions were performed, and phage concentrations were quantified by plaque assay (23).

Phage-host interactions in the free-living phase: detection of aggregate formation.

The effects of phages ΦH20 and KVP40 on the growth and aggregate formation of their respective host strains, BA35 and PF430-3, during free-living growth in liquid cultures were examined. Overnight cultures were inoculated in 50 ml MB with the respective phages at an MOI of 0.1. The flasks were incubated at room temperature with agitation; samples were collected for determination of the presence of cell aggregates by epifluorescence microscopy. For epifluorescence microscopic analysis of cell aggregation, subsamples were filtered onto 0.45-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane filters (Whatman) and stained with SYBR gold (Invitrogen) (0.5%) for 10 min. Bacteria and phages on the filters were distinguished based on their dimensions and/or their relative levels of brightness.

Phage susceptibility and physiological fingerprint of bacterial isolates.

In order to determine changes in phage susceptibility, a total of ∼180 cells were isolated from phage-treated microcolony experiments, pretreated-biofilm experiments, and free-living samples and analyzed for phage susceptibility patterns. For colony isolation, samples were in all cases plated onto thiosulfate citrate bile salt sucrose agar (TCBS; Difco) and incubated for 24 h. From these plates, single colonies were isolated and purified by 3 rounds of reisolation and then transferred to 4 ml MB for subsequent phage susceptibility analysis. Phage susceptibility of the isolated strains was determined by spot tests (21).

Biolog GN2 Microplates (Biolog) containing 95 different carbon sources were used to test the ability of selected phage-amended isolates to use different substrates, following the manufacturer's instructions (21). For strain PF430-3, the procedure was slightly modified, as the bacterial lysate (bacterial culture subjected to phage-induced lysis) and aggregates were collected by centrifugation at a lower speed (3,000 × g, 5 min) and washed twice with 0.9% saline buffer.

Adsorption experiments with fluorescently labeled phages.

Phage adsorption to selected isolates was tested by adding SYBR gold-labeled phages to cultures followed by visual inspection of phage binding to the cells using epifluorescence microscopy, following the protocol of Kunisaki and Tanji (25) with some modifications. Aliquots of 600 μl phage lysate were digested by addition of DNase I (Qiagen) (1 μl DNase I, 3 μl RDD buffer [Qiagen]) at 37°C for 2 h and then stained with SYBR gold (Invitrogen) (final concentration, 5×) overnight at 4°C. A 10-μl volume of chloroform was then added to inactivate the DNase I. The phage stock was then further filtered through a 30-kDa ultrafiltration spin device (Millipore) at 1,000 × g for 90 min to remove the free SYBR gold. The SYBR gold-labeled phages were added to the mid-log-phase wild-type cells and phage lysate, respectively, at an MOI of approximately 10 and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Samples were pelleted at 12,000 × g for 3 min, and the pellet was resuspended in a small volume of SM buffer, mixed with 0.5% (wt/vol) agarose (Bio-Rad) preheated to around 45°C, and transferred to gel-coated slide glass.

Statistical analysis.

All statistics were performed using the Student's paired t test (two-tailed) (OriginPro 8.6) to determine the significance of the differences between the phage-amended and control cultures. Differences were considered to be significant at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Initial biofilm formation and short-term effects of phages.

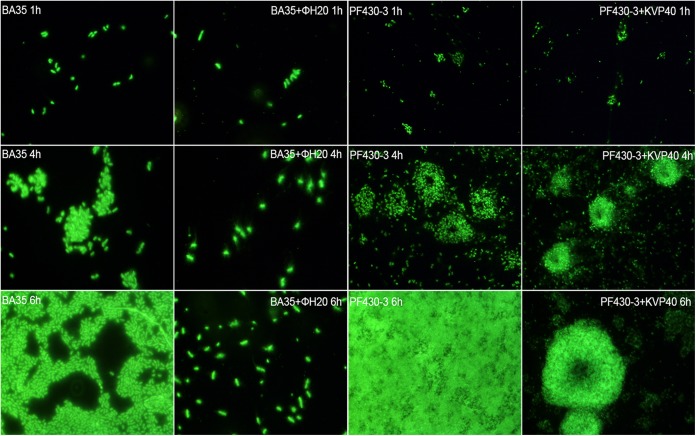

The two V. anguillarum strains formed microcolonies with highly different morphologies in the absence of their corresponding phages. Strain BA35 formed simple single-layered microcolonies, where individual cells could easily be identified, whereas strain PF430-3 formed complex 3-dimensional volcano-shaped structures (Fig. 1). Phage ΦH20 showed efficient control of BA35 microcolonies according to the microscope observations, reducing the total colony area from 41,000 μm2 per mm2 filter on the control filters to 5,000 μm2 per mm2 filter after 6 h of incubation and leaving mainly single cells on the filters following phage exposure (data not shown). For strain PF430-3, the individual colonies were unaffected by phage exposure, whereas single cells were lysed by phage KVP40, leaving mainly colonies on the filters at 6 h postaddition (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Fluorescence microscopic images of microcolony formation of strain BA35 (left two columns) and strain PF430-3 (right two columns) at different time points in the absence and presence of phage ΦH20 and phage KVP40, respectively. Samples were stained with 0.5% SYBR gold for 10 min.

Effects of phages on biofilm formation.

Establishment and growth of biofilm produced by the two V. anguillarum strains, BA35 and PF430-3, in cultures pretreated with phages ΦH20 and KVP40, respectively, were examined over a long-term experiment in parallel to an experiment performed with control cultures without phages. The OD600 of free-living bacteria in the control cultures reached maximum values of 0.72 ± 0.01 and 0.98 ± 0.01 for BA35 and PF430-3, respectively, after 2 days (Fig. 2A and C). A gradual minor decrease was then observed for BA35, whereas the density of PF430-3 decreased to ∼50% of the maximum value at day 9 (Fig. 2A and C).

FIG 2.

Culture density and biofilm formation of V. anguillarum strains BA35 and PF430-3 in cultures pretreated with phages ΦH20 and KVP40, respectively, and control cultures. (A) Optical density (OD600, left y axis) of free-living cells (strain BA35) in the presence and absence of phage ΦH20 and the corresponding free-living phage ΦH20 concentration (PFU ml−1, right y axis). (B) Strain BA35 biofilm formation in the presence and absence of phage ΦH20, quantified by crystal violet (OD595, left y axis). (C) Optical density (OD600, left y axis) of free-living cells (strain PF430-3) in the presence and absence of phage KVP40 and the corresponding free-living phage KVP40 concentration of (PFU ml−1, right y axis). (D) Strain PF430-3 biofilm formation in the presence and absence of phage KVP40, quantified by crystal violet (OD595, left y axis). Error bars represent the actual ranges of data from all experiments carried out in duplicate.

The presence of the phages had different effects on the free-living cell densities of the two strains. For strain BA35, the density reached a level of 70% of the density of the control cultures after 2 days and remained at this level (and was significantly lower only at days 3 [P = 0.025] and 6 [P = 0.009]) throughout the experiment (Fig. 2A). In the cultures with strain PF430-3, addition of phage KVP40 significantly reduced the optical density of the culture (0.008 ≤ P ≤ 0.027, comparing the OD values at individual time points from day 2 onward) to approximately 25% of the corresponding values in the control cultures (Fig. 2C). Phage concentrations reached peaks of around 1.3 × 1010 ± 3.5 × 108 and 3.4 × 108 ± 7.1 × 106 PFU ml−1 for ΦH20 and KVP40, respectively, at day 1 (Fig. 2A and C). Interestingly, in the PF430-3-plus-KPV40 cultures, phage concentrations decreased significantly (P = 0.007) from day 1 to day 2 and then stabilized at around 106 PFU ml−1 (Fig. 2C). Likewise, the concentrations of phage ΦH20 decreased significantly (P = 0.0055) from day 1 to day 5 and then remained at a titer above 2.2 × 109 ± 2.8 × 108 PFU ml−1 (Fig. 2A).

The biofilm development in response to phage addition also showed completely different patterns in the two strains, with either inhibition (BA35) or stimulation (PF430-3) of biofilm formation relative to control cultures. In the BA35-plus-ΦH20 pretreatment cultures, phage ΦH20 effectively prevented biofilm formation, causing a 2-fold decrease in the biofilm biomass relative to the control level (Fig. 2B). In the PF430-3-plus-KVP40 pretreatment cultures, phage KVP40 addition resulted in an almost 3-fold increase relative to the control level (Fig. 2D). In the control cultures, there was a steady increase in biofilm density for strain PF430-3, whereas a fast initial establishment of biofilm of strain BA35 was followed by a gradual reduction in the level of biofilm during the 7-day period (Fig. 2B and D).

To assess the effect of phages on fully matured biofilms, 10-day biofilms were challenged with their corresponding phages, measuring the same parameters as those described above. As in the pretreatment experiments, phage addition significantly reduced the BA35 biofilm level (3-to-4-fold reduction) within 2 days (P = 0.046, comparing OD values from days 1 and 2) and slightly stimulated the production of biofilm in PF430-3 relative to the control levels (Fig. 3B and D).

FIG 3.

Culture density and biofilm formation of V. anguillarum strains BA35 and PF430-3 in cultures posttreated with phages ΦH20 and KVP40, respectively, and control cultures. (A) Optical density of free-living cells (strain BA35) (OD600, left y axis) in the presence and absence of phage ΦH20 and the corresponding phage free-living ΦH20 concentration (PFU ml−1, right y axis). (B) Strain BA35 biofilm formation in the presence and absence of phage ΦH20, quantified by crystal violet (OD595, left y axis), and corresponding biofilm-associated phage concentration (PFU ml−1, right y axis). (C) Optical density (OD600, left y axis) of free-living cells (strain PF430-3) in the presence and absence of phage KVP40 and the corresponding free-living phage KVP40 concentration of (PFU ml−1, right y axis). (D) Strain PF430-3 biofilm formation in the presence and absence of phage KVP40, quantified by crystal violet (OD595, left y axis), and the corresponding biofilm-associated phage concentration of (PFU ml−1, right y axis). Error bars represent the actual ranges of the results from all experiments carried out in duplicate.

For the free-living populations, the input of nutrients associated with the addition of phages (and corresponding addition of medium in the controls) caused an increase in bacterial concentrations in the control cultures (Fig. 3A and C). Similarly to the pretreated cultures, the OD600 decreased over time in the control cultures, with the strongest decrease observed in the PF430-3 cultures. The presence of phages, however, imposed a significant 4-to-5-fold decrease in the concentrations of free-living cells in both experiments (0.003 ≤ P ≤ 0.046, comparing the OD values at individual time points from day 2 onward), except for day 5 (Fig. 3A and C).

The concentration of free-living phages reached peaks of around 3 × 109 ± 2.8 × 107 and 5.8 × 108 ± 2.8 × 107 PFU ml−1 for ΦH20 and KVP40, respectively, after 24 h (Fig. 3A and C) followed by a gradual decrease in the concentration of phage KVP40 (Fig. 3C). The biofilm-associated concentration of phage KVP40 constituted less than 10% of the free-living population concentration and decreased dramatically after the peak (Fig. 3D).

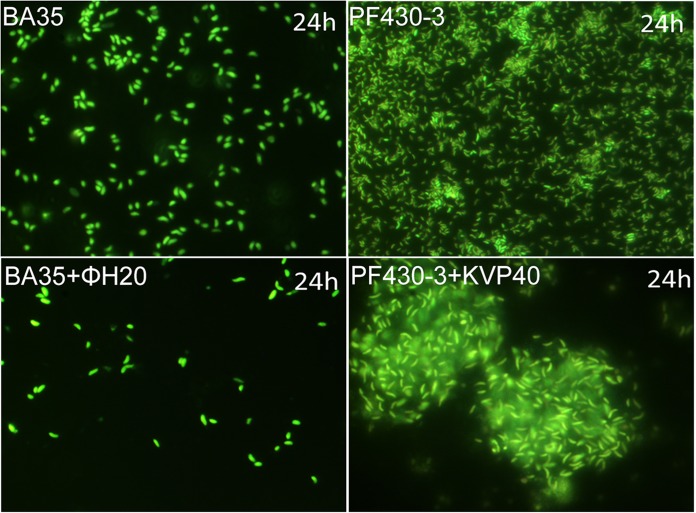

Effects of phage KVP40 on bacterial aggregation in liquid cultures.

In the BA35 and BA35-plus-ΦH20 cultures, no aggregate formation was observed and phage addition reduced the density of free-living cells relative to the control level as a result of cell lysis (Fig. 4). The motility of BA35 seemed to be affected by phage addition, as cells in the phage-added cultures had reduced motility or no motility after 24 h (see Movie S1 and Movie S2 in the supplemental material). In the PF430-plus-KVP40 cultures, on the other hand, aggregates of multilayered cell clusters embedded in a matrix were observed after 24 h (Fig. 4; see also Movie S3 and Movie S4).

FIG 4.

Fluorescence microscopic examination of aggregate formation in V. anguillarum strains BA35 and PF430-3 in the presence and absence of phages. No aggregate formation was observed in BA35 and BA35-plus-ΦH20 cultures, and phage addition reduced the concentration of free-living cells relative to the level seen with the control. In the PF430-plus-KVP40 cultures, phage-induced aggregates were observed.

Bacteriophage resistance and physiological fingerprint.

For strain BA35, all the isolates obtained from the microcolony experiment were resistant to phage infection and approximately 30% of the free-living and biofilm-associated isolates were sensitive to ΦH20 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The resistant colonies were small-colony variants on TCBS plates. In contrast, all the isolates from KVP40-exposed PF430-3 cultures were fully or partially susceptible to phage KVP40 and no completely KVP40-resistant mutants were isolated (see Table S1). Colony morphologies of PF430-3 isolates were similar to those of the wild-type PF430-3 strain. Spot assays showed that all partially resistant isolates regained full sensitivity to phage KVP40 after purification by restreaking of single colonies on agar plates.

The phenotypic diversity and implications of resistance for the metabolic properties of the isolates following phage exposure were explored by obtaining a metabolic fingerprint of selected isolates using Biolog GN2 assay (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). For strain BA35, the phage-resistant isolate had lost the ability to use 10 of the 54 substrates that could be metabolized by wild-type BA35 cells, corresponding to a 19% reduction of the capacity of substrate utilization. In contrast, none of the PF430-3 isolates obtained after phage exposure showed any changes in their physiological fingerprint according to the Biolog profile (see Fig. S1).

To further examine the mechanisms of resistance or tolerance of phages in the two strains, SYBR gold-labeled phages ΦH20 and KPV40 were incubated with wild-type cells and phage lysate. Fluorescently labeled phage ΦH20 attached to the sensitive cells of the BA35 strain (Fig. 5A), whereas no phage attachment was observed in phage-resistant mutants (Fig. 5B). In the parallel experiment performed with fluorescently labeled KVP40 phages, the phages were immobilized in the aggregates and did not attach to the cell surface (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG 5.

Visualization of phage adsorption by SYBR gold-labeled phages under a phase-contrast epifluorescence microscope. (A) Wild-type BA35 cells with SYBR gold-labeled phage ΦH20 (phase contrast plus fluorescence). (B) BA35 phage lysate with SYBR gold-labeled phage ΦH20 (phase contrast plus fluorescence). (C) PF430-3 phage lysate with SYBR gold-labeled phage KVP40 (phase constrast). (D) PF430-3 phage lysate with SYBR gold-labeled phage KVP40 (phase contrast plus fluorescence).

DISCUSSION

Phage effects on microcolony formation and initial biofilm development.

The microscopic observations of microcolony formation of cells attached to a polycarbonate filter surface revealed that the two strains formed highly different types of microcolonies, with large implications for the phage-host interactions. The phage-resistant isolates obtained from BA35 cultures exposed to ΦH20 maintained resistance upon reculturing, suggesting that resistance was a result of genetic mutations which prevented phage infection. In contrast to the strong lytic effect of ΦH20 and corresponding reduction in microcolony formation of strain BA35, phage KVP40 did not significantly affect the size of individual PF430-3 microcolonies. A possible explanation could be that the complex 3-dimensional structure of PF430-3 microcolonies, once formed, provided protection from phage infection by creating physical barriers.

Long-term effects of phages on biofilm formation from liquid cultures of different V. anguillarum strains.

The strong controlling effects of phage ΦH20 on the strain BA35 biofilm observed under both the pretreatment and posttreatment conditions supported the microscopic observations indicating that the BA35 biofilm is a relatively simple structure which is easily accessible for phage adsorption. Also, in the free-living phase, phage ΦH20 was able to control the phage-susceptible BA35 population, but under those conditions, phage-resistant mutants replaced the sensitive population within the first 24 h. The interactions between ΦH20 and strain BA35 thus seemed very similar for attached and free-living cells, suggesting that the flat and smooth biofilm structure did not offer protection against phage infection.

In contrast, addition of phage KVP40 to strain PF430-3 resulted in enhanced biofilm formation in both experiments, and particularly during the early stage of biofilm development. At the same time, the free-living bacterial population was efficiently controlled and maintained at an OD level of <25% of the maximum density in the control cultures, in both the pretreatment and posttreatment PF430-3 experiments. This suggested a coupling between the phage-mediated decrease in the density of free-living cells and the corresponding cell aggregate formation and the subsequent increase in biofilm formation.

Potential mechanisms of phage protection in V. anguillarum strains.

While the dominance of phage-resistant strains following phage exposure suggested mutational changes as the mechanism of phage protection in strain BA35, the interaction between strain PF430-3 and phage KVP40 pointed toward aggregation and biofilm formation as a protection against phage infection. This mechanism of protection was supported by a number of observations: (i) addition of fluorescently labeled KVP40 phage to aggregates and free-living cells of PF430-3 showed that KVP40 was trapped in the aggregate matrix and did not adsorb to the host cells embedded in the aggregates; (ii) the complex 3-dimensional structure of the microcolonies observed for PF430-3 was also consistent with the hypothesis that the aggregation provided a refuge for phage-sensitive bacteria (26–28); and (iii) the presence of a fraction of free-living phage-sensitive cells outside the aggregates may in part be explained by the entrapment of phages in the aggregates which reduced the phage encounter rate, possibly allowing coexistence of small populations of free-living phages and free-living sensitive cells.

In combination with the reduced phage sensitivity found in a number of the isolates, the immobilization of free-living cells in aggregates and subsequent attachment to surfaces provide an efficient refuge for cells exposed to phage attack, thus adding to the multiple and complex protection mechanisms found in bacteria (14, 29, 30). Whether the aggregation is a direct response to phage exposure, e.g., through quorum-sensing (QS)-mediated gene regulation, which is well known from studies of V. anguillarum (31–33), or is an indirect effect of phage-lysis of free-living cells, thus adding a strong positive selection pressure for aggregate-forming phenotypes, needs to be elucidated (30).

It should be noted that successful phage amplification depends not only on the host cell lysis but also on the phages able to bind to the susceptible bacterium. Polysaccharide depolymerases, which allow phages to access phage receptors in biofilm-associated cells, have been reported in various phages (34). Consequently, the generality of protection mechanisms observed in the present study is unknown, as other phages may be able to infect the biofilm-forming PF430-3 strain. It is often assumed that bacteriophage resistance is associated with a cost (35, 36) due to reduced abilities to take up specific nutrients (37) and reduced competitive abilities in general (38, 39). The Biolog fingerprint of resistant isolates of strain BA35 supported the notion of such a link between phage resistance and reduced physiological performance, as the resistant mutants had a reduced ability to utilize a number of substrates. The absence of observed physiological changes in the phage-exposed isolates of strain PF430-3 relative to the wild-type strain, on the other hand, supported the suggestion that phage tolerance in strain PF430-3 was not caused by mutational changes but rather was due to protection by aggregation. It should be emphasized, however, that fitness costs other than those resolved by the Biolog assay may have been present in strain PF430-3.

Interestingly, the free-living isolates obtained from the KVP40-amended PF430-3 cultures, which had reduced phage susceptibility, all recovered full sensitivity after regrowth in the absence of phage KVP40. This indicated that the phage tolerance was a transient phenotype, as has also been observed in other phage infection studies, including hosts such as V. cholerae (40), Salmonella enterica (41), Salmonella enterica serovar Oranienburg (42), and E. coli O157:H7 (41, 43), and suggests that downregulation of phage receptor gene expression may also play a role in phage susceptibility in strain PF430-3 (44).

In conclusion, our data demonstrated completely different mechanisms of protection against phages in two strains of V. anguillarum and showed that these intraspecific differences strongly influenced the outcome of the phage-host interactions with respect to (i) the ability of phages to control free-living host populations, (ii) the ability of phages to control the development and stability of biofilm, (iii) the phage-driven diversification of bacterial populations, and (iv) the coexistence and coevolution of phages and hosts. However, additional studies are needed to explore whether the different responses to phage exposure are general properties of the strains or are linked to the specific phages.

Implications for phage control of the pathogen.

In a phage therapy context, the interaction between strain BA35 and phage ΦH20 suggests that phage control of strain BA35 potentially would prove useful, since the phage efficiently inhibited biofilm formation on both short and longer time scales as well as proving efficient at disrupting already established biofilms. The phage-derived stimulation of biofilm formation in strain PF430-3 may, on the other hand, suggest that phage KVP40 would be inefficient in controlling this strain in aquaculture and might instead stimulate its pathogenic impact by inducing biofilm formation.

Our study data thus confirm that successful application of phage therapy in the treatment of biofilm requires detailed understanding of phage-host interactions and emphasize that the complexity and diversity of phage-host interactions even within the same species of pathogen are challenges for future use of phages in disease control.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Danish Strategic Research Council (ProAqua project 12-132390), the Danish Council for Independent Research (FNU 09-072829), and EU-IRSES-funded project AQUAPHAGE (269175).

We thank Pantelis Katharios, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research, for kindly providing V. anguillarum PF430-3 and vibriophage KVP40 and Lone Gram, Technical University of Denmark, for kindly providing V. anguillarum BA35. Jeanett Hansen is acknowledged for technical support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00518-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frans I, Michiels CW, Bossier P, Willems KA, Lievens B, Rediers H. 2011. Vibrio anguillarum as a fish pathogen: virulence factors, diagnosis and prevention. J Fish Dis 34:643–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evelyn TPT. 1971. First records of vibriosis in Pacific salmon cultured in Canada, and taxonomic status of the responsible bacterium, Vibrio anguillarum. J Fish Res Board Can 28:517–525. doi: 10.1139/f71-073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen JL, Pedersen K, Dalsgaard I. 1994. Vibrio anguillarum serovars associated with vibriosis in fish. J Fish Dis 17:259–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1994.tb00221.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW, Stoodley P. 2004. Bacterial biofilms: from the natural environment to infectious diseases. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindell K, Fahlgren A, Hjerde E, Willassen NP, Fallman M, Milton DL. 2012. Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen prevents phagocytosis of Vibrio anguillarum by rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) skin epithelial cells. PLoS One 7:e37678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakai T, Sugimoto R, Park K, Matsuoka S, Mori K, Nishioka T, Maruyama K. 1999. Protective effects of bacteriophage on experimental Lactococcus garvieae infection in yellowtail. Dis Aquat Org 37:33–41. doi: 10.3354/dao037033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imbeault S, Parent S, Lagacé M, Uhland CF, Blais J-F. 2006. Using bacteriophages to prevent furunculosis caused by Aeromonas salmonicida in farmed brook trout. J Aquat Anim Health 18:203–214. doi: 10.1577/H06-019.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenholm AR, Dalsgaard I, Middelboe M. 2008. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages infecting the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:4070–4078. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00428-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karunasagar I, Shivu MM, Girisha SK, Krohne G, Karunasagar I. 2007. Biocontrol of pathogens in shrimp hatcheries using bacteriophages. Aquaculture 268:288–292. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.04.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinod MG, Shivu M, Umesha K, Rajeeva B, Krohn G, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. 2006. Isolation of Vibrio harveyi bacteriophage with a potential for biocontrol of luminous vibriosis in hatchery environments. Aquaculture 255:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu W, Forster T, Mayer O, Curtin JJ, Lehman SM, Donlan RM. 2010. Bacteriophage cocktail for the prevention of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa on catheters in an in vitro model system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:397–404. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00669-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doolittle MM, Cooney JJ, Caldwell DE. 1995. Lytic infection of Escherichia coli biofilms by bacteriophage T4. Can J Microbiol 41:12–18. doi: 10.1139/m95-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sass P, Bierbaum G. 2007. Lytic activity of recombinant bacteriophage phi11 and phi12 endolysins on whole cells and biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:347–352. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01616-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S. 2010. Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:317–327. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martiny JB, Riemann L, Marston MF, Middelboe M. 2014. Antagonistic coevolution of marine planktonic viruses and their hosts. Annu Rev Mar Sci 6:393–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freese E. 1959. The specific mutagenic effect of base analogues on phage T4. J Mol Biol 1:87–105. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(59)80038-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva-Rubio A, Avendano-Herrera R, Jaureguiberry B, Toranzo AE, Magarinos B. 2008. First description of serotype O3 in Vibrio anguillarum strains isolated from salmonids in Chile. J Fish Dis 31:235–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inoue T, Matsuzaki S, Tanaka S. 1995. A 26-kDa outer membrane protein, OmpK, common to Vibrio species is the receptor for a broad-host-range vibriophage, KVP40. FEMS Microbiol Lett 125:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller ES, Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Durkin AS, Ciecko A, Feldblyum TV, White O, Paulsen IT, Nierman WC, Lee J, Szczypinski B, Fraser CM. 2003. Complete genome sequence of the broad-host-range vibriophage KVP40: comparative genomics of a T4-related bacteriophage. J Bacteriol 185:5220–5233. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.17.5220-5233.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen K, Gram L, Austin DA, Austin B. 1997. Pathogenicity of Vibrio anguillarum serogroup O1 strains compared to plasmids, outer membrane protein profiles and siderophore production. J Appl Microbiol 82:365–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan D, Gram L, Middelboe M. 2014. Vibriophages and their interactions with the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3128–3140. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03544-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Højberg O, Binnerup SJ, Sørensen J. 1997. Growth of silicone-immobilized bacteria on polycarbonate membrane filters, a technique to study microcolony formation under anaerobic conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:2920–2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams MH. 1959. Bacteriophages. Interscience Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R. 1999. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol 310:91–109. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)10008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunisaki H, Tanji Y. 2010. Intercrossing of phage genomes in a phage cocktail and stable coexistence with Escherichia coli O157:H7 in anaerobic continuous culture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:1533–1540. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heilmann S, Sneppen K, Krishna S. 2012. Coexistence of phage and bacteria on the boundary of self-organized refuges. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:12828–12833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200771109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schrag SJ, Mittler JE. 1996. Host-parasite coexistence: the role of spatial refuges in stabilizing bacteria-phage interactions. Am Nat 148:348–377. doi: 10.1086/285929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brockhurst MA, Buckling A, Rainey PB. 2006. Spatial heterogeneity and the stability of host-parasite coexistence. J Evol Biol 19:374–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2005.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samson JE, Magadan AH, Sabri M, Moineau S. 2013. Revenge of the phages: defeating bacterial defences. Nat Rev Microbiol 11:675–687. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koskella B, Brockhurst MA. 2014. Bacteria-phage coevolution as a driver of ecological and evolutionary processes in microbial communities. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:916–931. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croxatto A, Chalker VJ, Lauritz J, Jass J, Hardman A, Williams P, Camara M, Milton DL. 2002. VanT, a homologue of Vibrio harveyi LuxR, regulates serine, metalloprotease, pigment, and biofilm production in Vibrio anguillarum. J Bacteriol 184:1617–1629. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.6.1617-1629.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Croxatto A, Pride J, Hardman A, Williams P, Camara M, Milton DL. 2004. A distinctive dual-channel quorum-sensing system operates in Vibrio anguillarum. Mol Microbiol 52:1677–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milton DL. 2006. Quorum sensing in vibrios: complexity for diversification. Int J Med Microbiol 296:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes KA, Sutherland IW, Jones MV. 1998. Biofilm susceptibility to bacteriophage attack: the role of phage-borne polysaccharide depolymerase. Microbiology 144(Pt 11):3039–3047. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lenski RE. 1988. Experimental studies of pleiotropy and epistasis in Escherichia coli. II. Compensation for maldaptive effects associated with resistance to virus T4. Evolution 42:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenski RE. 1988. Experimental studies of pleiotropy and epistasis in Escherichia coli. I. Variation in competitive fitness among mutants resistant to virus T4. Evolution 42:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luckey M, Nikaido H. 1980. Specificity of diffusion channels produced by lambda phage receptor protein of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:167–171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.1.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harcombe WR, Bull JJ. 2005. Impact of phages on two-species bacterial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5254–5259. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5254-5259.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kay MK, Erwin TC, McLean RJ, Aron GM. 2011. Bacteriophage ecology in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa mixed-biofilm communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:821–829. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01797-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seed KD, Faruque SM, Mekalanos JJ, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Camilli A. 2012. Phase variable O antigen biosynthetic genes control expression of the major protective antigen and bacteriophage receptor in Vibrio cholerae O1. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002917. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim M, Ryu S. 2011. Characterization of a T5-like coliphage, SPC35, and differential development of resistance to SPC35 in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2042–2050. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02504-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kocharunchitt C, Ross T, McNeil D. 2009. Use of bacteriophages as biocontrol agents to control Salmonella associated with seed sprouts. Int J Food Microbiol 128:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng H, Knecht HJ, Kudva IT, Hovde CJ. 2006. Application of bacteriophages to control intestinal Escherichia coli O157:H7 levels in ruminants. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5359–5366. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00099-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Mærkedahl RB, Svenningsen SL. 2013. A quorum-sensing-induced bacteriophage defense mechanism. mBio 4:e00362-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00362-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuzaki S, Tanaka S, Koga T, Kawata T. 1992. A broad-host-range vibriophage, KVP40, isolated from sea water. Microbiol Immunol 36:93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.