Significance

Mammalian chromatin is compartmentalized in topologically associating domains (TADs), genomic regions within which sequences preferentially contact each other. This organization has been proposed to be essential to organize the regulatory information contained in mammalian genomes. We show that Six homeobox genes, essential developmental regulators organized in gene clusters across different animal phyla, share a deeply conserved chromatin organization formed by two abutting TADs that predates the Cambrian explosion. This organization is required to generate separate regulatory landscapes for neighboring genes within the cluster, resulting in very different gene expression patterns. Finally, we show that this extremely conserved 3D architecture is associated with a characteristic arrangement of CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) binding sites in diverging orientations, revealing a genome-wide conserved signature for TAD borders.

Keywords: CTCF, TAD, Six cluster, regulatory landscapes, evolution

Abstract

Increasing evidence in the last years indicates that the vast amount of regulatory information contained in mammalian genomes is organized in precise 3D chromatin structures. However, the impact of this spatial chromatin organization on gene expression and its degree of evolutionary conservation is still poorly understood. The Six homeobox genes are essential developmental regulators organized in gene clusters conserved during evolution. Here, we reveal that the Six clusters share a deeply evolutionarily conserved 3D chromatin organization that predates the Cambrian explosion. This chromatin architecture generates two largely independent regulatory landscapes (RLs) contained in two adjacent topological associating domains (TADs). By disrupting the conserved TAD border in one of the zebrafish Six clusters, we demonstrate that this border is critical for preventing competition between promoters and enhancers located in separated RLs, thereby generating different expression patterns in genes located in close genomic proximity. Moreover, evolutionary comparison of Six-associated TAD borders reveals the presence of CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) sites with diverging orientations in all studied deuterostomes. Genome-wide examination of mammalian HiC data reveals that this conserved CTCF configuration is a general signature of TAD borders, underscoring that common organizational principles underlie TAD compartmentalization in deuterostome evolution.

Noncoding DNA in animal genomes harbors regulatory information that controls the levels and the spatiotemporal activation of gene expression (1, 2). Information is precisely organized in the 3D chromatin favoring contacts between regulatory elements and target genes (3). Subdivision into topologically associating domains (TADs), megabase-scale domains in which sequences preferentially contact one another, represents a hierarchical level in chromatin 3D organization (4–9). The limited number of studies conducted to date show that a large fraction of TADs are invariant among cell types and largely conserved in mammals (4–6, 10), but the extent of their evolutionary conservation and functional organizer properties are largely unexplored.

Results and Discussion

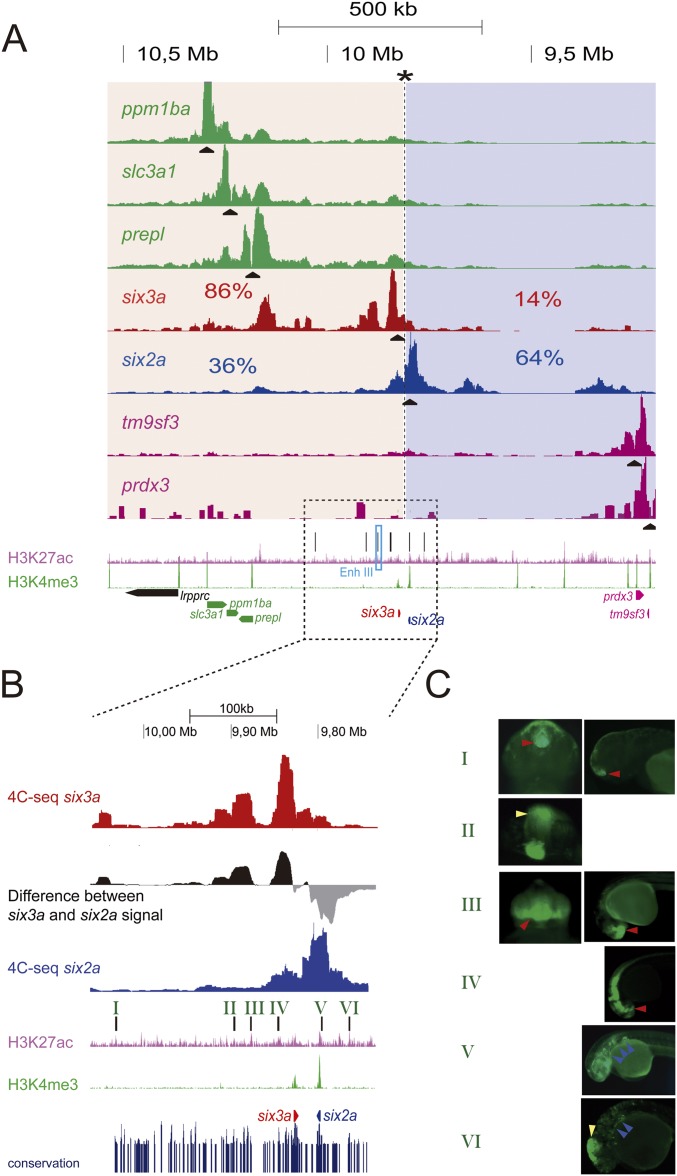

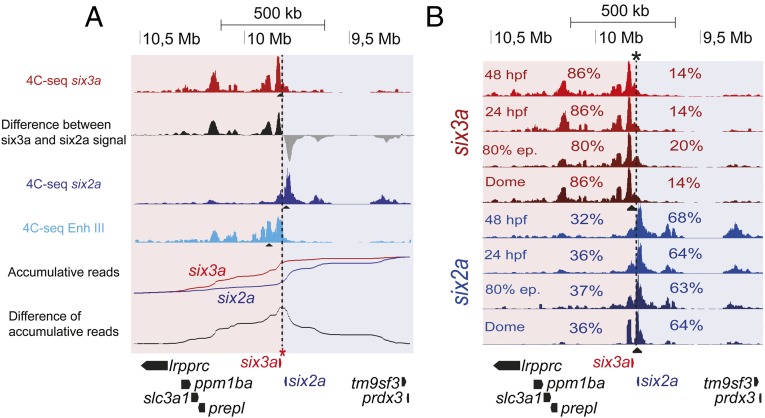

We analyzed the 3D regulatory architecture of Six homeobox gene clusters, applying a bottom-up approach, from genomic organization to gene regulation and developmental patterning. Six homeobox genes, essential for the development of many embryonic structures, comprise three subfamilies—Six1/2, Six3/6, and Six4/5—tandemly arrayed in tight genomic clusters strongly conserved in several animal phyla (11). As a consequence of ancestral whole genome duplications, most vertebrate genomes contain two paralogous copies of the Six cluster: one containing Six2 and Six3 and the other Six1, Six4 and Six6. Teleost genomes contain four clusters (12) given the extra genome duplication at the base of their lineage. Thus, Six genes’ genomic organization remained strongly conserved, likely reflecting the presence of strong cis-regulatory constraints (11). Using high-resolution circular chromosome conformation capture (4C-seq) on zebrafish embryos, we identified genomic contacts of different genes located along the chromatin region encompasing the six3a-six2a cluster (Fig. S1A). The six3a-six2a cluster is split into two separate compartments defined by the genomic contacts of the two genes (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1A). The intergenic border constitutes a sharp border in which genomic contacts shift from one regulatory landscape to the other, as revealed by the distribution of the differential 3D interactions for the two promoters, obtained as the difference between the two Six 4C-seq signals (Fig. 1A). The precise location where this shift occurs corresponds to the genomic position with a maximal difference of accumulated contact reads for each gene along the entire locus (Fig. 1A, asterisk). Taking this position as a reference point (Fig. 1B, asterisk and dashed line), the preborder gene desert 5′ to six3a accounts for more than 80% of its 3D interactions; similarly six2a contacts are preferentially located at the opposite gene desert (>60%), upstream of its promoter (Fig. 1B). This border is therefore an inflection point at which contacts from one gene decline abruptly, whereas interactions from the other drastically increase despite the proximity of both promoters to regions abutting this border. This physical partition may facilitate directing enhancer elements to their right target gene, preventing promiscuous contacts. Indeed, multiple H3K27ac-marked cis-regulatory elements (Fig. S1 A and B), corresponding to tissue-specific enhancers as determined by transgenic assays (Fig. S1C), are present in these regions. six3a, but not six2a, is expressed in the developing eye. Accordingly, a strong eye enhancer used as a 4C viewpoint (Enh III; Fig. S1) preferentially contacts the six3a but not the six2a promoter (Fig. 1A), with only minor contacts beyond the border region and with other contacts in common with the six3a promoter, revealing many enhancer–enhancer interactions within the six3a regulatory domain, as found for other loci (13–16). The six3a and six2a 3D chromatin architecture is already present at blastula stage, before transcription initiation (Fig. 1B). Similar results have been found in mammals and Drosophila, indicating that some genes have a preassembled 3D chromatin architecture that likely facilitates precise gene regulation (6, 13, 14, 16, 17). The overall 3D interaction map remains constant throughout development, with some local contact variations, likely linked to particular cis-regulatory element activation (Fig. 1B).

Fig. S1.

The six3a/six2a locus is partitioned in two regulatory landscapes harboring several tissue specific enhancers. (A) High-resolution circular chromosome conformation capture (4C-seq) in whole zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf from different viewpoints (black triangles) along the six3a/six2a genomic region. The genomic position region in which there is a maximum difference between the accumulative contacts from the six3a and six2a viewpoints is shown with an asterisk, and the two 3D compartments are shaded in red and blue, respectively. The bottom tracks show the distribution of the H3K27ac (pink) and H3K4me3 (green) histone marks and the genes along this genomic region. Above the H3K27ac track, the black lines show the different regions tested for enhancer activity. The Enhancer III region used as a 4C-seq viewpoint in the fourth track is highlighted with a light blue rectangle. (B) Close up of the region around the six3a and six2a genes marked by a dotted rectangle in A. The different identified enhancers are numbered from I to VI. The last blue track shows evolutionary conserved regions. (C) Transgenic embryos from anterior (Left) or lateral (Right) views showing GFP expression driven by the different H3K27ac positive regions tested. The vector used in the transgenic assays to test the activity of regions II and VI contains a midbrain enhancer used as a positive control of transgenesis. This expression domain (red arrow) is therefore independent of the region under evaluation. Regions I to IV drive the reporter in six3a-expressing territories, whereas regions V and VI activate GFP in six2a domains.

Fig. 1.

The six3a/six2a cluster in divided in two developmentally stable 3D compartments. (A) The first, third, and fourth tracks show 4C-seq data on whole zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf from six3a (red), six2a (dark blue), and Enhancer III (Enh III, light blue) viewpoints, respectively. The second track shows the difference between the number of reads in the 4C-seqs from the six3a and six2a viewpoints. Black and gray signals indicate positive or negative differences, respectively. The fifth track shows accumulative reads along the region for six3a (red) and six2a (blue). Differences of these accumulative reads are shown in the track below. The asterisk marks the border region. (B) 4C-seq on whole zebrafish embryos at dome, 80% epiboly, 24 and 48 hpf from the six3a and six2a viewpoints (black triangles). Contact percentages for each gene on the two 3D compartments are indicated.

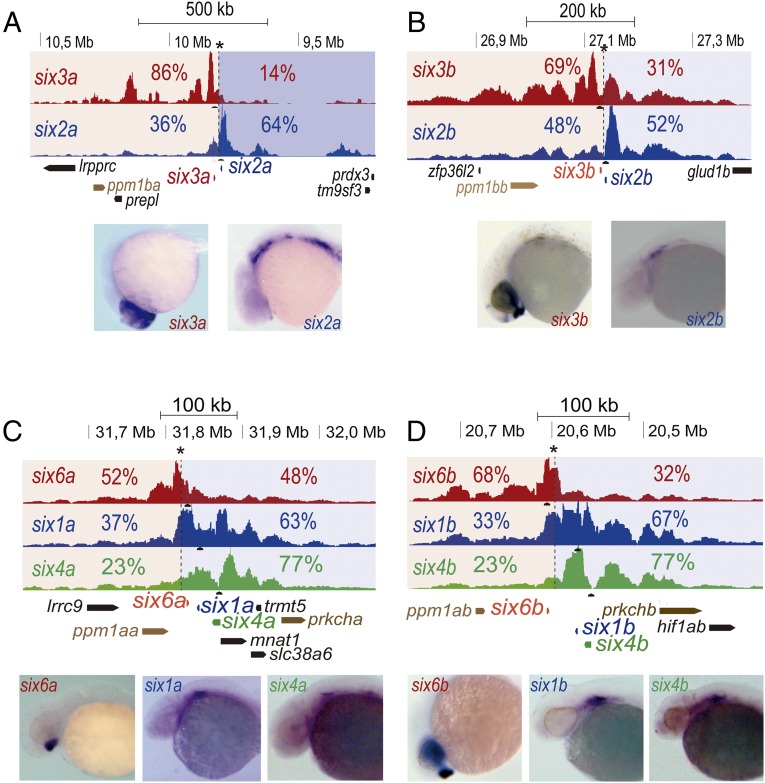

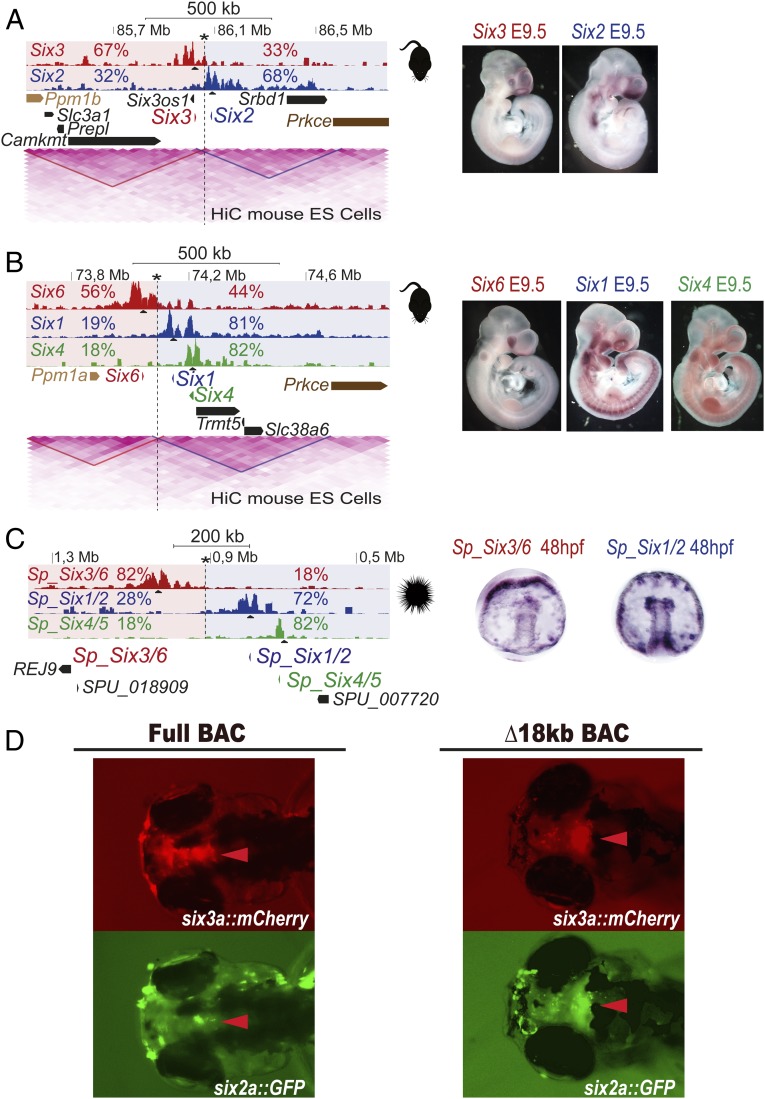

The 3D chromatin structures of the remaining zebrafish six clusters (Fig. 2 and Figs. S2 and S3) were always developmentally conserved with two largely different regulatory landscapes for each cluster: one detected from the six3/6 promoters’ side (six3a, six3b, six6a, and six6b) and the other from the promoters at the opposite side of the cluster (six1/2 and six4) (Fig. 2). Indeed, a border isolated six3a, six3b, six6a, and six6b from the other genes of the corresponding clusters (Fig. 2, asterisks and dashed lines). In all cases, six genes’ contacts preferentially take place within the regulatory domains generated by the border (Fig. 2). Supporting the presence of these two regulatory landscapes in each cluster, the expression patterns of six3a, six3b, six6a, and six6b are dramatically different from those of six1/2 and six4, which instead largely share expression domains.

Fig. 2.

All four zebrafish six clusters are divided in two different 3D compartments. (A–D) 4C-seq on whole zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf from the different six genes at each cluster (black triangles). Border regions are indicated by an asterisk, and the two 3D compartments are shaded in red and blue. Contact percentages for each gene on the two 3D compartments are shown. Expression patterns of each gene at 24 hpf are shown for each gene below the 4C-seq tracks. (A) six3a/six2a cluster. (B) six3b/six2b cluster. (C) six6a/six1a/six4a cluster. (D) sixba/six1b/six4b cluster.

Fig. S2.

Developmental dynamics of chromatin contacts, H3K27ac and H3K4me3 histone marks, and RNA-seq at the different zebrafish six clusters. (A–C) six3b/six2b (A), six6a/six1a/six4a (B), and six6b/six1b/six4b (C) clusters. In all clusters, the frequency of contacts at each side of the boundary (dashed lines and asterisks) is indicated for each promoter viewpoint.

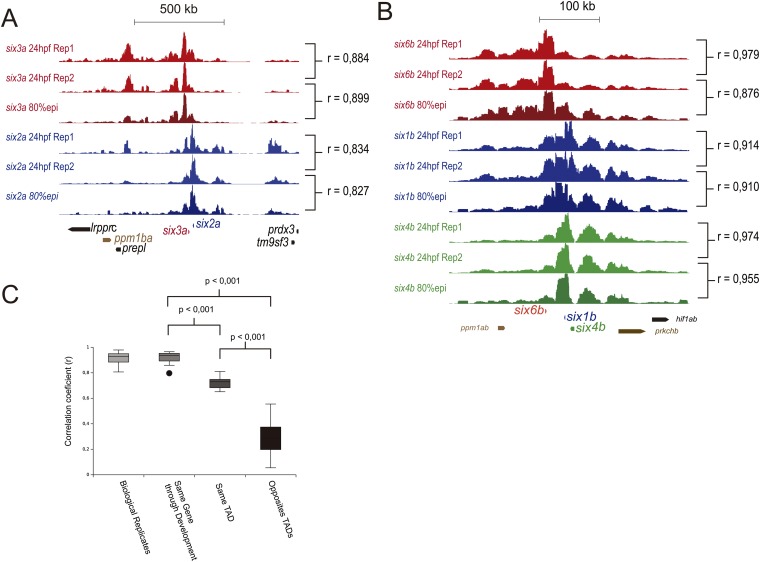

Fig. S3.

4C-seq replicas at the same stage are similar to 4C-seq at different developmental stages. (A and B) Comparison between 4C-seq replicas at a single stage and 4C-seq at different developmental stages in the six3a/six2a (A) and six6b/six1b/six4b (B) clusters. (Right) The correlation coefficients between 4C-seq datasets. (C) Correlation coefficient between 4C-seq dataset from replicas of the same gene at the same stage, same gene at different stages, genes within the same TAD, or genes at different TADs.

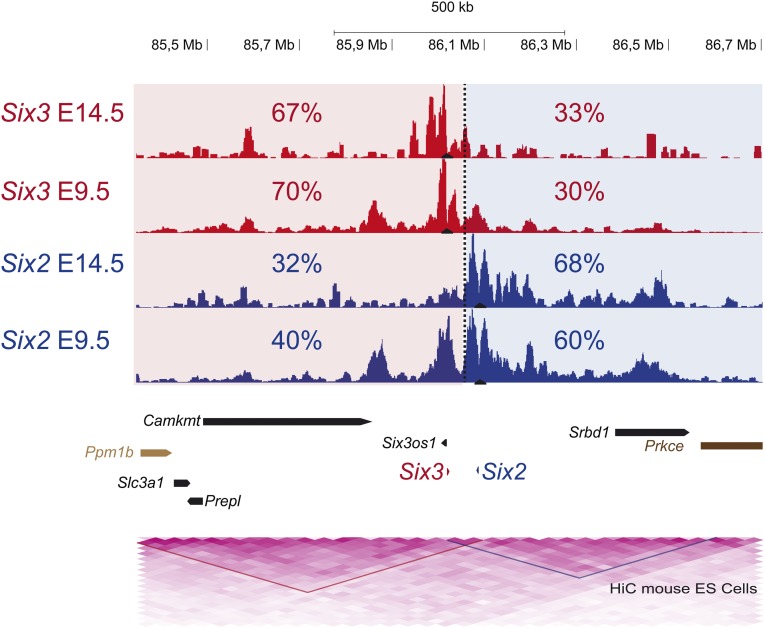

To determine whether a similar two-chromatin 3D territories organization is present in other vertebrates, we performed 4C-seq from the mouse Six gene promoters (Fig. 3 A and B), which again revealed a clear partition of both clusters, with developmentally invariant 4C-seq contacts (Fig. S4): the regulatory landscapes of Six3 and Six6 genes define one chromatin 3D territory opposite to those of Six1/2 and Six4. Similarly, the bipartite topology of the clusters correlates with the divergent expression patterns of the genes located at each side of the border regions. Furthermore, HiC data from mouse cells shows that the two different regulatory 3D domains defined by 4C-seq precisely match two separated TADs (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4), with the border region identified by 4C-seq located at the border of these TADs.

Fig. 3.

Conserved subdivision of Six clusters in two 3D compartments along deuterostome evolution. (A–C) 4C-seq in whole mouse (A and B) or sea urchin (C) embryos from the different Six genes as viewpoints. Border regions are indicated by an asterisk, and the two 3D compartments are shaded in red and blue. Contact percentages for each gene on the two 3D compartments is shown. In murine clusters, HiC data from mouse ES cells is shown below. HiC data show that clusters are divided into the two TADs also defined by 4C-seq. Border regions identified by 4C-seq coincide in both clusters with TADs borders. (Right) Expression patterns of the different genes. (D) Transient transgenic fish embryos injected with the full six2a-GFP/six3a-mCherry BAC (Left) or a TAD-deleted version (Δ18kb) of the same BAC (Right) at 72 h hpf. Arrowheads point to the brain expression domain characteristic of the six3a gene.

Fig. S4.

3D chromatin configuration of the mouse Six3/Six2 cluster at two different developmental stages. 4C-seq from Six3 and Six2 viewpoints (black triangles) in whole embryos at stages E14.5 and E9.5. The genomic region in which there is maximal difference between the accumulative contacts from the Six3 and Six2 viewpoints is shown with a dashed line, and the two 3D compartments are shaded in red and blue, respectively. The percentage of contacts for each gene on the two 3D compartments is indicated. Below are shown the two TADs detected by HiC data from mouse ES cells (red and blue triangles).

These results indicate that vertebrate Six clusters share an evolutionary conserved 3D chromatin architecture, possibly predating whole genome duplications present in the vertebrate ancestor cluster. This possibility was verified by the analysis of the genome from gastrulating sea urchin embryos, a distant invertebrate deuterostome with an intact ancestral Six-tandem configuration, in which the Six3/6 gene is expressed in apical neurogenic territories with a pattern largely different from that of the Six1/2, as in vertebrates and other bilaterians (18–20). Consistently, the sea urchin Six cluster is divided into two regulatory landscapes: one defined by the Six3/6 promoter contacts and the other by Six1/2 and Six4/5 promoter contacts (Fig. 3C). Thus, a deeply conserved 3D chromatin architecture of the Six cluster composed of two different TADs has been preserved from deuterostome ancestors.

As these results suggest that strong long-lasting regulatory pressures constrained the evolution of this genomic organization, we attempted to determine the functional contribution of this evolutionary conserved TAD border to Six gene expression using BAC recombineering and zebrafish transgenesis. We selected a 194-kb six3a/six2a-containing BAC spanning from +47 kb upstream of six2a to +120 kb upstream of six3a, including the intergenic region harboring the TAD border. In this BAC, we replaced the six2a and the six3a coding regions by GFP and mCherry, respectively. Transient transgenic zebrafish embryos generated with this BAC showed strong mCherry but weak GFP expression in the brain (Fig. 3D, Left). These results are consistent with this BAC containing mainly six3a-associated regulatory regions. We then generated a deleted version of the BAC by removing an 18-kb fragment spanning the intergenic region containing the TAD border. This region is devoid of strong H3K27ac peaks, suggesting that no enhancers are present within the deletion. This deletion dramatically changed the reporters’ expression, and six2a-GFP was now strongly activated in the six3a brain-associated domain. We conclude that the deeply evolutionary conserved TAD border is critical in preventing competition between promoters for enhancers located in opposite regulatory landscapes. This border, in turn, helps generating largely different expression patterns of genes located in the same genomic cluster.

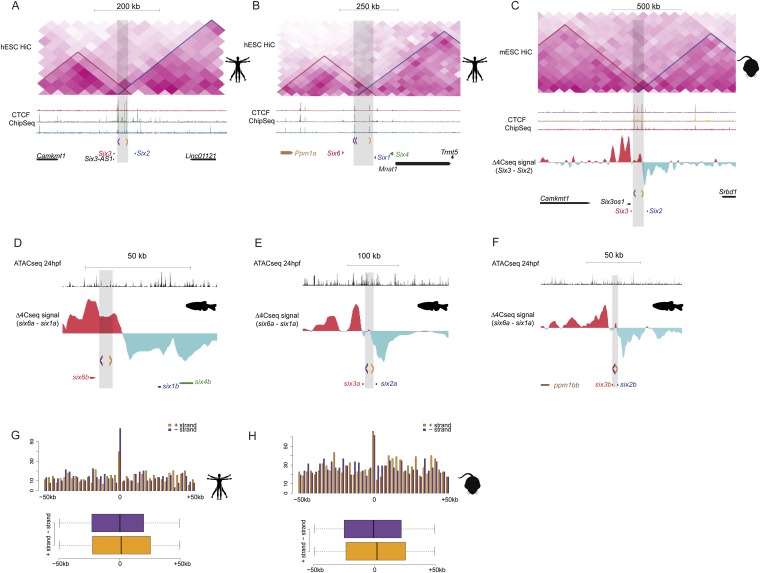

To explore the possible determinants of the highly conserved 3D architecture of the Six clusters, we searched for conserved signatures associated with the TAD borders that bisect them in all deuterostomes examined. The DNA binding protein CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is instrumental for the 3D organization of the chromatin. CTCF, which is highly enriched at TAD borders (21), facilitates the formation of DNA loops that form between CTCF binding sites because of their attracting and interacting converging (head-to-head) orientations (10). Consistently, CTCF ChIP-seq data from human and mouse cells revealed several mammalian conserved CTCF sites at the deeply conserved Six TAD borders (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5 A–C), which notably are disposed in a diverging (tail-to-tail) orientation. We checked whether this diverging orientation was also present in zebrafish and scanned Six clusters to detect CTCF sites. As CTCF ChIP-seq data are not available in this species, we used our recently generated ATAC-seq data from zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf (22), because this technique allows the identification of open chromatin regions at high resolution, including CTCF sites (23). This technique revealed several ATAC-seq footprints at Six border regions containing high score CTCF motifs that, as in the case of mammals, were also disposed in the same tail-to-tail diverging orientation and located in equivalent conserved syntenic positions (Fig. 4B, Figs. S5 D–F and S6, and Table S1). A divergent CTCF arrangement was found also in the intergenic region in which the Six border of the sea urchin cluster is located (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Diverging CTCF sites are signature of TAD borders. (A–C) Mouse (A), zebrafish (B), and sea urchin (C) Six6/Six1/Six6 cluster. From bottom to top, all panels show the genes at their corresponding genomic regions, the difference between Six6 and Six1 4C-seq signals, and the orientation of CTCF sites represented by arrowheads (purple and yellow correspond to sites in minus or plus strands, respectively). Note that the difference between Six6 and Six1 4C-seq signals clearly reveals the TAD border determined by HiC from mouse ES cells (upper track in A). A also shows the genomic distribution of CTCF in three different mouse cell types (second track). B shows ATAC-seq data from 24-hpf zebrafish embryos (first track). (D and E) Upper graph in each panel shows the number (y axis) and orientation of CTCF motifs along 50 kb (x axis) at each side of the human (D) and mouse (E) TAD borders. Below each graph, a boxplot show the enrichment of CTCF in diverging orientations at each side of the borders.

Fig. S5.

Diverging CTCF sites are signature of TAD borders and are not associated with promoters. (A and B) These panels show, from top to bottom, HiC data from human ES cells, the genomic distribution of CTCF in three different cell types, the orientation of CTCF sites represented by arrowheads (purple and yellow correspond to sites in minus or plus strands, respectively) at the boundary regions, and the genes at the Six2/Six3 (A) and Six6/Six1/Six4 (B) clusters. (C) Mouse Six3/Six2 cluster showing HiC data from mouse ES cells, the genomic distribution of CTCF in three different cell types, the difference between Six3 and Six2 4C-seq signals, the orientation of CTCF sites, and the genes around this genomic region. (D–F) From top to bottom, ATAC-seq peaks from 24-hpf zebrafish embryos, difference between Six genes 4C-seq signals, orientation of CTCF sites represented by arrowheads, and genes at the six6b/six1b/six4b (D), six3a/six2a (E), and six3b/six2b (F) clusters. (G and H) (Upper) Number (y axis) and orientation (purple and yellow bars correspond to CTCF sites at the plus or minus strands, respectively) of CTCF sites along 50 kb (x axis) at each side of human (D) and mouse (E) randomly selected promoters (1,000). (Lower) Boxplot shows the enrichment of CTCF in diverging orientations at each side of the boundaries. The differences observed between the mean relative position of the motifs in both strands were statistically significant in the boundary-centered windows (P = 3.27E−113 in human, P = 1.75E−118 in mouse; Fig. 4), but not in the promoter-centered windows (P = 0.107 in human, P = 0.066 in mouse).

Fig. S6.

ATAC-seq signal at CTCF sites in zebrafish. The different panels show the ATAC-seq peaks at each CTCF sites in the different zebrafish Six cluster, as indicated.

Table S1.

Genomic coordinates of CTCF sites at Six boundaries

| CTCF matrix coordinates | |||||||

| CTCF name | Specie | Pointed gene | Chromosome | Start | End | Matrix | Value |

| hCTCFsix6 (1) | Human | Six6 | chr14 | 61026278 | 61026302 | TGGACAGCAGGGGGCTCTC | 16 |

| hCTCFsix6 (2) | Human | Six6 | chr14 | 61029012 | 61029036 | CCGCCACTTGGAGGCAGTG | 13 |

| hCTCFsix1 | Human | Six1 | chr14 | 61092245 | 61092270 | TGGCCAGCAGGTGGCACTC | 23 |

| hCTCFsix2 | Human | Six2 | chr2 | 45182932 | 45182961 | TCGCCGCGAGGTGGCAGCA | 16 |

| hCTCFix3 | Human | Six3 | chr2 | 45208915 | 45208940 | TCTCCAGCAGGTGGCGCCA | 21 |

| mCTCFsix6 (1) | Mouse | Six6 | chr12 | 74074290 | 74074314 | ATGCCACCAGGGGGCTCTC | 17 |

| mCTCFsix6 (2) | Mouse | Six6 | chr12 | 74077887 | 74077911 | TGTACGCCAGGTGGTGCTG | 12 |

| mCTCFsix1 | Mouse | Six1 | chr12 | 74122104 | 74122128 | TATCCAGCAGGGGGCACTC | 20 |

| mCTCFsix2 | Mouse | Six2 | chr17 | 86033160 | 86033184 | CGGCCGCGAGGTGGCAGCA | 16 |

| mCTCFsix3 | Mouse | Six3 | chr17 | 86064479 | 86064503 | TCTCCAGCAGGTGGAGCCA | 18 |

| zCTCFsix6a | Zebrafish | six6a | chr13 | 31832136 | 31832159 | TGACCACCAGAGGTCGCAA | 19 |

| zCTCFsix1a | Zebrafish | six1a | chr13 | 31835564 | 31835588 | TTGCCACCAGAGGGCAGAA | 11 |

| zCTCFsix6b | Zebrafish | six6b | chr20 | 20600656 | 20600680 | CTAACTGAAGAGGGCGCTC | 12 |

| zCTCFsix1b | Zebrafish | six1b | chr20 | 20596398 | 20596422 | TGTCCACTAGAGGGAACCA | 19 |

| zCTCFsix2a | Zebrafish | six2a | chr13 | 9819167 | 9819191 | TTCCCACAAGATGGCGTAA | 13 |

| zCTCFsix3a | Zebrafish | six3a | chr13 | 9804005 | 9804029 | CGTTCAGGAGAGGGCGCCA | 14 |

| zCTCFsix2b | Zebrafish | six2b | chr12 | 27133491 | 27133515 | TCACCACATGATGGCGACA | 12 |

| zCTCFsix3b | Zebrafish | six3b | chr12 | 27134370 | 27134394 | TGGCCAGCAGAGGGTGCTT | 18 |

| SpCTCFsix3/6 (1) | Sea Urchin | Sp_six3/6 | Scaffold143 | 896688 | 896712 | TGACCAACAGACAGCGGCC | 8 |

| SpCTCFsix3/6 (2) | Sea Urchin | Sp_six3/6 | Scaffold143 | 892778 | 892812 | CGGCCAGGAGATGGAGAAG | 13 |

| SpCTCFsix1/2 (1) | Sea Urchin | Sp_six1/2 | Scaffold143 | 888274 | 888298 | CGGCCAGGAGATGAAGCAG | 11 |

| SpCTCFsix1/2 (2) | Sea Urchin | Sp_six1/2 | Scaffold143 | 883271 | 883297 | ATGACGACAGAGGGCGGCA | 10 |

These results suggest that this configuration of CTCF sites could be a conserved and genome-wide used signature of TAD borders. We thus scanned available CTCF ChIP-seq data for the orientation of all CTCFs binding sites within 50 kb of mouse and human TAD borders (5). We found a very pronounced shift in the orientation of the CTCF sites from to the other side of mammalian borders, with a clear diverging configuration (Fig. 4 D and E). Moreover, 72% and 48% of the mouse and human borders, respectively, contained at least one pair of CTCF sites with this tail-to-tail configuration. This shift in the orientation of the CTCF sites was not observed in regions around promoters, which are also enriched in CTCF sites (Fig. S5 G and H).

In summary, Six genes have maintained their general 3D chromatin organization throughout deuterostome evolution to generate different regulatory landscapes in the same gene cluster. This chromatin configuration may be even more ancient than that reported here, dating back to the ancestor of all bilaterians or even eumetazoans, because the Six cluster is present in some lophotrochozoans and cnidarian genomes. Our results demonstrate that specific 3D chromatin architectures can be evolutionary preserved across different animal phyla and divergent body plans. Our data also show the power of evolutionary comparison to identify sequence signatures associated with deeply conserved borders. This strategy reveals that CTCF binding sites positioned in diverging orientation, likely by promoting loops toward opposite directions, may be essential for TAD border formation/maintenance along deuterostome evolution.

Materials and Methods

4C-seq.

Mouse and zebrafish experiments were approved by the Ethic Committee of the University Pablo de Olavide and the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas in accordance with national and European regulations.

4C-seq assays were performed as previously reported (24–27). Whole zebrafish (at 48 hpf, 24 hpf, 80% epiboly, and dome stages) and mouse (at 9.5 and 14.5 d of development) embryos were processed as previously described (28) to get ∼10 million isolated cells. For sea urchin samples, 10 million 48-hpf embryos were dissociated into ice-cold dissociation buffer (1 M glycine, pH 8, 2 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors). After several washes in Ca2+ free artificial sea water and one in PBS, cells were cross-linked for 10 min in 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM for 5 min at room temperature, and the cells were then collected and treated equally as mouse and zebrafish cross-linked cells. Briefly, cells were treated with lysis buffer [10 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8, 10 mM NaCl, 0.3% IGEPAL (octylphenoxypolyethoxyethanol) CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich; I8896), and 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Complete; Roche; 11697498001)]. Nuclei were digested with DpnII endonuclease (New England Biolabs; R0543M) and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Promega; M1804). Subsequently, Csp6I endonuclease (Fermentas, Thermo Scientific; FD0214) was used in a second round of digestion, and the DNA was ligated again. Specific primers (Table S2) were designed close to gene promoters or regulatory elements with primer3 (bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/primer3/). Illumina adaptors were included in the primer sequences (29). Eight 25-μL PCRs were performed with the Expand Long Template PCR System (Roche; 11759060001) for each viewpoint, pooled together, and purified using the High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche; 11732668001). The Quanti-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen; P11496) was used to measure sample concentration and then deep sequenced. 4C-seq data were analyzed, with some changes, as described in ref. 26. In brief, raw sequencing data were de-multiplexed and aligned using the Mouse July 2007 (NCBI37/mm9), Zebrafish December 2009 (Zv9/danRer7), or Sea Urchin June 2011 (BCM-HGSC Spur_v3.1/strPur4) assemblies as the reference genomes. Reads located in fragments flanked by two restriction sites of the same enzyme or in fragments smaller than 40 bp were filtered out. Mapped reads were then converted to reads-per-first-enzyme-fragment-end units and smoothed using a 30 DpnII fragments mean running window algorithm.

Table S2.

Primers used for 4C-seq experiments

| Organism | Primer | Sequence | Read primer (DpnII) position |

| Zebrafish | six2a_DpnII | GAAGAGAGGCACAAAACTTTAGATC | chr13:9797970 |

| six2a_Csp6I | GTCATCGCTTAGATAGACATACAAGTAC | ||

| six3a_DpnII | AGTGGGTGGAATATTATTGTGATC | chr13:9826837 | |

| six3a_Csp6I | AAGTGGTGAAAGCCTCTACGTAC | ||

| six2b_DpnII | GCTTACTACTAAGTAAAGTTTTTGA | chr12:27140158 | |

| six2b_Csp6I | TCATCAAATGCGGTTAAAGC | ||

| six3b_DpnII | CCAGAAGCAGAGGGCGA | chr12:27128597 | |

| six3b_Csp6I | TCCAAGTACCATTGCCGAATA | ||

| six4a_DpnII | GCGCTGCAGAGTGCATTGATC | chr13:31871941 | |

| six4a_Csp6I | TGTTGTCAGATTGGGAATAGGGACC | ||

| six1a_DpnII | ACTTCCGTGAGCTCTACAAGATC | chr13:31845355 | |

| six1a_Csp6I | GGCTCCCCTATGCAATCCAC | ||

| six6a_DpnII | CAATGTTGCCAAACACACGAAGATC | chr13:31826506 | |

| six6a_Csp6I | GCCCTATACGCCAACTTCAAGTC | ||

| six4b_DpnII | CCCACGACTCTCCCTCTTGATC | chr20:20557180 | |

| six4b_Csp6I | TCGTCTCTGCAGGATATGTGGTAC | ||

| six1b_DpnII | GTCTCTCCCGGCTTGCGATC | chr20:20572332 | |

| six1b_Csp6I | ACTGTCGACTCATGTCGCGC | ||

| six6b_DpnII | TGAGCTGTCAGATGTCTACGAGATC | chr20:20606589 | |

| six6b_Csp6I | GCCCTATACGCCAACTTCAAGTC | ||

| ppm1ba_DpnII | GCTGATATGCATGCAAGA | chr13:10292253 | |

| ppm1ba_Csp6I | CAATATTCAGAAATGAGCGAGT | ||

| slc3a1_DpnII | CCGAATTCAACCGAAAGA | chr13:10186394 | |

| slc3a1_Csp6I | TGCGTTTGAAGGAATCTAGCGT | ||

| prepl_DpnII | GAGAGTGAATACACGCAGA | chr13:10237450 | |

| prepl_Csp6I | CACAAGTGGAGGTGGTGT | ||

| tm9sf3_DpnII | CGTAAAATTGTTCAGCGAGTGATC | chr13:9240919 | |

| tm9sf3_Csp6I | CCTCTCGATGTGTTGGTGTAC | ||

| prdx3_DpnII | GAAGGTGAAGTCTGTTCAAAGATC | chr13:9208662 | |

| prdx3_Csp6I | CATAAAGGTGCTGCTGACGTAC | ||

| EnhIII(R5)_DpnII | TACTCTCAGAGCTGTTAAAGGATC | chr13:9877427 | |

| EnhIII(R5)_Csp6I | GTTGCTGCATCTTCTGGAC | ||

| EnhVI(2.2)_DpnII | GGAGCCACGCGGATTAAGAGATC | chr13:9763732 | |

| EnhVI(2.2)_Csp6I | GATAGCCCACAGGAATTCGGCTG | ||

| Mouse | Six2_DpnII | CGACTCCTGAGTCACAACGATC | chr17:86087424 |

| Six2_Csp6I | CACTACATCGAGGCGGAGAAGC | ||

| Six3_DpnII | GCGCCCTCTGCGTAGAGATC | chr17:86022535 | |

| Six3_Csp6I | CCAGCAACTGTCAGCAGCCG | ||

| Six4_DpnII | GTCCCTGCCCCAGAGCgatc | chr12:74213772 | |

| Six4_Csp6I | TGCCTGCCCAGAAGTTCCGAG | ||

| Six1_DpnII | GGAATCCCTTCTCTCACTTGGATC | chr12:74149274 | |

| Six1_Csp6I | GGGGACTTATACGGGCTCTC | ||

| Six6_DpnII | ACAGGGAGGGGAAGTGGATC | chr12:74040426 | |

| Six6_Csp6I | CCAGGAGGCAGAGAAGCTGC | ||

| Sea urchin | Sp_six4/5_DpnII | CGCCACTTGAAACGGTGGGATC | Scaffold143:692728 |

| Sp_six4/5_Csp6I | AAAGTTCGCAGGGCTTTACATC | ||

| Sp_six1/2_DpnII | CAAAAATAGGCGACAGCGAGATC | Scaffold143:780065 | |

| Sp_six1/2_Csp6I | AGGATAGGGGTTGTGGGAGTAC | ||

| Sp_six3/6_DpnII | GCAATGGCAACTCCTCTCTTGAtc | Scaffold143:1022703 | |

| Sp_six3/6_Csp6I | TTGGCCCCGTCGACAAGTAC |

For comparative analysis, we took the genomic region containing the major part of the regulatory landscape of every gene present in a particular cluster and normalized all datasets by total weight. To predict the position of putative topological borders, the accumulated contacts of each viewpoint along the studied region were calculated, and then the position of maximum difference between accumulative contacts of different viewpoints located in the same cluster was determined. Furthermore, by calculating signal lineal ratio between genes supposed to be allocated in different TADs, we estimate whether this predicted region corresponds to the transition point in which contact from one gene start to decline considerably at the same time that contacts from the other begin to drastically increase. Once border position was calculated, we determined the percentage of reads aligned in both sides of the putative border for each gene of the cluster.

Zebrafish Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization.

Antisense RNA probes labeled with digoxigenin were prepared from cDNAs, and specimens were fixed, hybridized, and stained as previously described (30, 31). In situ probes were developed with nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP).

Mouse Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization.

Six2 and Six3 probes were kindly provided by Pascal Maire (Institute of Biomedical Research, Paris) and Tristán Rodríguez (Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London), respectively. The Six6 probe has been descried previously (32). Six1 and Six4 probes were generated by reverse amplification of whole mouse embryo RNA (stage 9.5 dpc) using the following primer pairs: Six1-F: CTCGGTCCTTCTGCTCCA, Six1-R: TCGCTGCTACCCTAACCG, Six4-F: CCTTTATGCTGTTAGTCCAGGG, Six4-R: CCGCCTTATAGAACGTTTTGAC, as described by the Allen Brain Atlas (www.brain-map.org). Amplified fragments were isolated and cloned into the pSpark vector (Canvax Biotech). Riboprobes were prepared using T7 RNA polymerase following manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics) on linearized cDNA clones. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was carried out on Cba X C57(B6) mouse embryos using digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes as described previously (33) using an InsituPro robot (Intavis).

Sea Urchin Whole-Mount in Situ Hybridization.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization in Strongylocentrotus purpuratus embryos has been described previously (34). Briefly, sea urchin embryos were fixed in glutaraldehyde solution. The fixed embryos were incubated in the hybridization buffer [50% (vol/vol) formamide, 5× SSC, 1× Denhardt’s, 1 mg/mL yeast tRNA, 50 ng/mL heparin, and 0.1% Tween-20] with 0.5 ng/μL digoxygenin- and fluorescein-labeled RNA probe(s) at 60 °C for 18 h. Posthybridization washes were hybridization buffer, 2× SSCT (2× SSC and 0.1% Tween-20), 0.2× SSCT, and 0.1× SSCT, each for 20 min at 60 °C. Subsequently, the antibody incubations were performed at room temperature with 1:1,000 diluted anti-DIG Fab (Roche). The embryos were extensively washed before staining reaction, including six times with MABT buffer (0.1 M maleic acid, 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20) and twice with AP buffer [100 mM Tris·Cl (pH 9.5), 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM levamisole]. BCIP and NBT were used for staining. Probes for six1/2 and six3/6 genes were obtained previously in refs. 19 and 35.

Generation of Recombinant BACs.

BAC clone (number 74B2) from the DanioKey zebrafish BAC library containing the six2a and six3a genes was purchased from Source BioScience. Recombiant BACs were generated as previously described (36, 37). For further details, see SI Materials and Methods.

CTCF Motif Distribution Along TAD Borders.

For calculating the average position of the CTCF motifs in each strand within the TAD borders, we searched the motifs located in CTCF ChIP-seqs peaks (38) common in at least five different tissues in mice or in constitutive CTCF peaks (39) in humans, which overlap with windows of 100 kb around each border. We used Clover software (40) with a score threshold of 10 for this search. We then plotted the motif distribution for each strand within these 100-kb windows around TAD borders using horizontal boxplots. For the direct comparison of the motif density at each position in these windows, we divided them in 20 bins of 5 kb each and plotted the distribution of motifs in both strands. As a random control for this analysis, we used 1,000 genomic windows of 100 kb centered in promoters that are known to be enriched in CTCF binding sites but are not involved in chromatin loop formation.

SI Materials and Methods

Generation of BAC DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2.

BAC clone (number 74B2) from DanioKey zebrafish BAC library containing the six2a and six3a genes was purchased from Source BioScience. BAC DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2 was generated as previously described (36, 37). Briefly, we used recombineering in the Escherichia coli SW105 strain to introduce the iTol2-A cassette from the piTol2-A plasmid (37) in the BAC plasmid backbone, which contains the inverted minimal cis-sequences required for Tol2 transposition. The insertion of the reporter gene GFP into the six2a locus of DK74B2-iTol2 BAC clone was carried out using homologous recombination. To that end, the GFP-pA-FRT-kan-FRT reporter gene cassette from the pBSK-GFP-pA-FRT-kan-FRT (37) plasmid was amplified by PCR, together with 50-bp homologies to the six2a translation start site (Fwd_six2aHA1-Gfp: TTAGATAGACATACAAGTACAAAGAGGGACGTTTATTTTTGAGACAAACCgccaccatgGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCTGTTC, ReV_six2aHA2-frt-kan-frt: CAGACGCACGCCACTTGCTCTTGCGTAAAGCCGAATGTTGGAAGCATAGACCGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC). Cells harboring the DK74B2-iTol2 BAC were transformed with the PCR product and clones in which homologous recombination have occurred were identified by PCR (Checksix2aHA1-Fwd: TGTGCCTCTCTTCACCCGGTG, Checksix2aHA1-ReV: CAGCTCCTCGCCCTTGCTCAC, Checksix2aHA2-Fwd: GAAGCAGCTCCAGCCTACACG, Checksix2aHA2-ReV: GGGAGAACTGGTGGCTTTCGAG). To excise Kan resistance, a step of flp induction using l-arabinose cultures was then included followed by the identification of Kan-sensitive clones using plate replicas with Amp + Cam + LB (Luria-Bertani medium) and Amp + Cam + Kan + LB plates. Sensitive clones were subjected to PCR confirmation using specific primers (flp_induction_Fwd: ACGAGCTGTACAAGTAAAGCGGC and flp_induction_ReV: CCGCGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGC). The mCherry_KanR cassette from pCS2+_mCherry_KanR (36) was amplified by PCR including 50-bp homologies to the six3a translation start site (Fwd_six3aHA-mCherry: TCGTCGTTCTTTTTTCCTTCGCAAATTTCACTCTCTCTCAGGTCATTTCCACCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAG, ReV_six3aHA_KanR: TTTGGCAGGAAGAAATGAGAGGGATAAAGCTCTAAAGGCGATCTGAAAACTCAGAAGAACTCGTCAAGAAGGCG). This PCR product was used to introduce by homologous recombination the mCherry reporter gene under control of the six3a promoter in the previous BAC and to generate the DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2 construct. Insertion was confirmed by PCR (Checksix3aHA1-Fwd: GATTGGCAGGGCTGCCATGAC, Checksix3aHA1-ReV: CCTCGCCCTTGCTCACCATGG, Checksix3aHA2-Fwd: GCCTTCTTGACGAGTTCTTCTG, Checksix3aHA2-Rev: GAAGCGACCATAGGAAGCG).

Generation of Δ18kb DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2 BAC.

Δ18kb DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2 was generated as follows. Two fragments of 250 bp flanking the target region were amplified using the following primers: Del_EcoRI_HA1-Fwd: TTGAATTCGCGTTCTTAGCAAGCAGGAT and Del_PstI_HA1-ReV: TTCTGCAGCGTTTAGCATCCACTCGTAGC (HA1 fragment) for one side; and Del_PstI_HA2-Fwd: TTCTGCAGATGCGTCTGAACTCGGGACT and Del_XhoI_HA2-ReV: TTCTCGAGCCCCAGCCAACCCTTATTTCG (HA2) and subsequently cloned into pCR8-GW-TOPO vectors. Spectinomycine (Spe) resistance was amplified using the following primers: PstI_SpeR_Fwd: TTCTGCAGCTGAAGCCAGTTA and PstI_ SpeR_ReV: TTCTGCAGTAGCTGTTTCCTG and also cloned into the pCR8-GW-TOPO vector. The HA1 fragment, HA2 fragment, and speR were excluded from their vectors by using EcoRI + PstI, PstI + XhoI, and PstI digestions, respectively. All excised fragments were purified and ligated together including a pCS2+ plasmid previously digested with EcoRI and XhoI restriction enzymes. pCS2+_HA1_speR_HA2 clones were selected by EcoRI + XhoI digestion. This clone was used as a PCR template of the Del_EcoRI_HA1-Fwd and Del_XhoI_HA2-ReV primers. This PCR product (deletion cassette) was used to recombine with DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry BAC. Clones carrying the deletion cassette (Δ18kb DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2) were selected by growing bacteria in LB + Cam + Spe plates and subsequently confirmed by PCRs targeting both flanks of the insertion using internal and external primers [DelCheck_six2a_Fwd(Genom): CCAACCCTTATTTCAGGTCATGC, DelCheck_six2a_ReV(Spectin): GTCCACTGGGTTCGTGCCTTC; DelCheck_six3a_Fwd(Spectin)]. In addition, two independent digestions with XhoI and NotI were performed in parallel in full and Δ18kb (DK74B2-six2a::GFP-six3a::mCherry-iTol2) BAC versions to verify the presence of the deletion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eric Davidson for support with the sea urchin experiments; Dr. W. De Laat for providing the 4C-seq method before publication; Fernando Casares for fruitful discussions; and Drs. Pascal Maire (Institute of Biomedical Research) and Tristán Rodríguez (Imperial College London) for providing reagents. This study was supported by the Spanish and Andalusian Governments (BFU2013-41322-P and Proyecto de Excelencia BIO-396 to J.L.G.-S., BFU2013-43213-P to P.B., BFU2014-55738-REDT to J.L.G.-S. and P.B., and BFU2011-22928 to J.C. and M.L.-M.). EU-FP7-PEOPLE-2011-CIG Grant 303904 “EPAXIALMYF5KO” also supported J.C.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE66900).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1505463112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Calo E, Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: What, how, and why? Mol Cell. 2013;49(5):825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Laat W, Duboule D. Topology of mammalian developmental enhancers and their regulatory landscapes. Nature. 2013;502(7472):499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips-Cremins JE. Unraveling architecture of the pluripotent genome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;28:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieberman-Aiden E, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326(5950):289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon JR, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485(7398):376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin F, et al. A high-resolution map of the three-dimensional chromatin interactome in human cells. Nature. 2013;503(7475):290–294. doi: 10.1038/nature12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagano T, et al. Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature. 2013;502(7469):59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sexton T, et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell. 2012;148(3):458–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nora EP, et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature. 2012;485(7398):381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature11049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao SS, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159(7):1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irimia M, et al. Extensive conservation of ancient microsynteny across metazoans due to cis-regulatory constraints. Genome Res. 2012;22(12):2356–2367. doi: 10.1101/gr.139725.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor JS, Van de Peer Y, Braasch I, Meyer A. Comparative genomics provides evidence for an ancient genome duplication event in fish. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2001;356(1414):1661–1679. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2001.0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrey G, et al. A switch between topological domains underlies HoxD genes collinearity in mouse limbs. Science. 2013;340(6137):1234167. doi: 10.1126/science.1234167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montavon T, Duboule D. Landscapes and archipelagos: Spatial organization of gene regulation in vertebrates. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(7):347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JR, et al. Analysis of hundreds of cis-regulatory landscapes at high resolution in a single, high-throughput experiment. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):205–212. doi: 10.1038/ng.2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghavi-Helm Y, et al. Enhancer loops appear stable during development and are associated with paused polymerase. Nature. 2014;512(7512):96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature13417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noordermeer D, et al. Temporal dynamics and developmental memory of 3D chromatin architecture at Hox gene loci. eLife. 2014;3:e02557. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinmetz PR, et al. Six3 demarcates the anterior-most developing brain region in bilaterian animals. Evodevo. 2010;1(1):14. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Z, Yaguchi J, Yaguchi S, Angerer RC, Angerer LM. The sea urchin animal pole domain is a Six3-dependent neurogenic patterning center. Development. 2009;136(7):1179–1189. doi: 10.1242/dev.032300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angerer LM, Yaguchi S, Angerer RC, Burke RD. The evolution of nervous system patterning: Insights from sea urchin development. Development. 2011;138(17):3613–3623. doi: 10.1242/dev.058172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong CT, Corces VG. CTCF: An architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(4):234–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg3663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gehrke AR, et al. Deep conservation of wrist and digit enhancers in fish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(3):803–808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420208112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buenrostro JD, et al. Quantitative analysis of RNA-protein interactions on a massively parallel array reveals biophysical and evolutionary landscapes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(6):562–568. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagège H, et al. Quantitative analysis of chromosome conformation capture assays (3C-qPCR) Nat Protoc. 2007;2(7):1722–1733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295(5558):1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noordermeer D, et al. The dynamic architecture of Hox gene clusters. Science. 2011;334(6053):222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1207194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Splinter E, de Wit E, van de Werken HJ, Klous P, de Laat W. Determining long-range chromatin interactions for selected genomic sites using 4C-seq technology: From fixation to computation. Methods. 2012;58(3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smemo S, et al. Obesity-associated variants within FTO form long-range functional connections with IRX3. Nature. 2014;507(7492):371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature13138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadhouders R, et al. Multiplexed chromosome conformation capture sequencing for rapid genome-scale high-resolution detection of long-range chromatin interactions. Nat Protoc. 2013;8(3):509–524. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tena JJ, et al. Odd-skipped genes encode repressors that control kidney development. Dev Biol. 2007;301(2):518–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jowett T, Lettice L. Whole-mount in situ hybridizations on zebrafish embryos using a mixture of digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labelled probes. Trends Genet. 1994;10(3):73–74. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallardo ME, et al. Genomic cloning and characterization of the human homeobox gene SIX6 reveals a cluster of SIX genes in chromosome 14 and associates SIX6 hemizygosity with bilateral anophthalmia and pituitary anomalies. Genomics. 1999;61(1):82–91. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Summerbell D, et al. The expression of Myf5 in the developing mouse embryo is controlled by discrete and dispersed enhancers specific for particular populations of skeletal muscle precursors. Development. 2000;127(17):3745–3757. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ransick A, Ernst S, Britten RJ, Davidson EH. Whole mount in situ hybridization shows Endo 16 to be a marker for the vegetal plate territory in sea urchin embryos. Mech Dev. 1993;42(3):117–124. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(93)90001-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Materna SC, Ransick A, Li E, Davidson EH. Diversification of oral and aboral mesodermal regulatory states in pregastrular sea urchin embryos. Dev Biol. 2013;375(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bussmann J, Schulte-Merker S. Rapid BAC selection for tol2-mediated transgenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2011;138(19):4327–4332. doi: 10.1242/dev.068080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suster ML, Abe G, Schouw A, Kawakami K. Transposon-mediated BAC transgenesis in zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(12):1998–2021. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunham I, et al. ENCODE Project Consortium An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, et al. Characterization of constitutive CTCF/cohesin loci: A possible role in establishing topological domains in mammalian genomes. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:553. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frith MC, et al. Detection of functional DNA motifs via statistical over-representation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(4):1372–1381. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]