Abstract

Background:

As the first experience of substance abuse often starts in adolescence, and studies have shown that drug use is mainly related to cigarette and alcohol consumption, an initial exploration of substance abuse prevalence, including cigarette and alcohol, seems to be the first step in preventing and controlling drug consumption. This study aimed to explore studies on drug use among high school students by investigating articles published in the past decade in Iran.

Methods:

In this study, the databases inside the country were used to access articles related to substance abuse by students during 2001–2011, among which 7 articles on 14–19 years old high school students were studied.

Results:

The seven studied articles showed that the highest drug use prevalence pertained to cigarette and hookah, followed by alcohol, opium, ecstasy, hashish and heroin. Opium and heroin use in Kerman city were, respectively, about 4 and 5 times of their use in other studied cities.

Conclusions:

Drug use is relatively high in the adolescent and effective group of the society, which requires particular attention and prompt and immediate intervention.

Keywords: Addiction, Iranian student, prevalence, substance abuse

INTRODUCTION

Substance abuse is a common phenomenon in the world and has invaded the human society as the most important social damage.[1,2] Substance abuse is a nonadaptive model of drug use, which results in adverse problems and consequences, and includes a set of cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms.[3]

Iran also, due to its specific human and geographic features, has a relatively high degree of contamination.[4] The World Health Organization's report in 2005 shows that there are about 200 million opiate addicts in the world, reporting the highest prevalence in Iran and the most frequency in the 25–35 year-age group.[5] The onset of drug use is often rooted in adolescence, and studies show that substance abuse is often related to cigarette and alcohol consumption in adolescence.[6] Results of studies indicate that age, being male, high-risk behavirs, and the existence of a cigarette smoker in the family or among friends, the experience of substance abuse, inclination and positive thoughts about smoking have relationship with adolescent cigarette smoking.[7] Studies also confirm that the chance of becoming a cigarette smoker among males and females is almost equal (11.2%); however, the prevalence of regular alcohol consumption in males (22.4%) is slightly higher than in females (19.3%).[8]

Few studies have been conducted in Iran on adolescents’ patterns of substance abuse, producing various data on the prevalence and the type of consumed drugs, but there is currently no known specific pattern of substance abuse in this age group; therefore, this review study has studied drug consumption prevalence in the student population of the country by collecting various data.

METHODS

This article is a narrative review focusing on studies conducted in Iran. In this research, all articles related to substance abuse and its patterns among high school students, which were conducted in Iran and published in domestic and international journals, were investigated. The articles were acquired from academic medical journals, research periodicals and the Scholar Google, Magiran, Irandoc, and Medlib. The search keywords included prevalence, substance abuse, Iranian student, and addiction.

This study explored articles in the past 10 years (2001–2011) about Iranian high school students. The full texts of the articles were often accessible in the scientific information database and magiran websites, but the full text of the article about Gilan Province was obtained after contacting the journal's office. Correspondence was made with the author of the article about Mahriz city to obtain the article as it was not published in the Toloee Behdasht journal.

These articles provide information about the consumed drug type, its prevalence in terms of the sex and age, and the experience of at-least-once consumption in the adolescent's life. Some articles had only pointed to drug consumption, which was also included in this research. Some had attended to substance abuse in general terms without distinguishing different kinds of drugs, and in some articles only psychoactive drug use, was mentioned.

The cases, in which the sample volume was not sufficient, or were not in the studied age groups, were excluded from the study. Due to different categorizations in these articles regarding the long-term prevalence of substance abuse or the experience of at-least-once consumption, in this study the shared aspect of these articles, that is, the experience of at-least-once use was adopted. Some articles had addressed the students’ predisposing factors for drug abuse, in addition to drug use prevalence, which were not included in this study for being scattered.

An initial search into the data bases yielded 11 articles, two of which were related to years before the study time frame (1997 and 1998). Furthermore, two articles were ignored, one because of its different age group (a lower age) and the other because it had addressed a particular district in Tehran with a small sample size. These results are based on 7 articles. All studies were about the 14–19 years old group, and only three studies had distinguished between the sexes. All 7 studies considered in this article were cross-sectional.

RESULTS

The prevalence of drug consumption in the studied cities

A study was conducted in 2003 on 500 students, from 142 high schools and vocational schools in Zahedan City, using a multi-stage cluster sampling method. In total, from the total of 259 females and 216 males who completed the questionnaire, the following results were obtained. 0.4% of the females and 2.3% of the males would usually smoke cigarette. The first experience of smoking was most often seen at the age of 14 (26.2%). The prevalence of other drugs was not studied in this research.[9] A study was conducted in 2009 on 610 students of Kerman's Male Pre-university Centers, in which the prevalence of each drug was reported, but the total consumption prevalence was not mentioned.[10]

A study in Gilan Province in 2004–2009 on 1927 high school students, including 46% females and 54% males, showed that the percentage of at-least-once use, including and excluding cigarette, was 23.7 and 12.8, respectively.[11]

A study in Karaj city in 2009–2010 on 447 high school students, including 239 females and 208 males, showed that 57% had at-least-once experience of drug use, including cigarette, of this number 56.1% were male and 43.9% were female.[12]

A study in Nazarabad city in 2007 on 400 3rd year high school students, including 204 females and 196 males with the mean age of 17.3, showed that drug use prevalence, including and excluding cigarette, was 24.5% and 11.1%, respectively.[13] A study was performed in Lahijan city in 2004 on 2328 high school students, including 42.2% females and 57.8% males.[14] A descriptive study was conducted in 2008 on a 285-member sample of male high school students.[15]

The consumption prevalence for each drug type in different cities

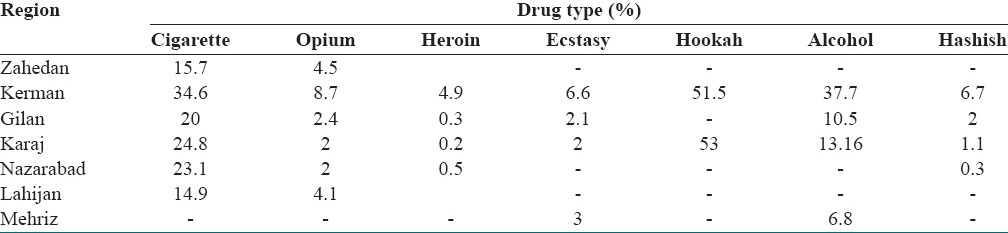

A research on Kerman's Male Pre-university students yielded the following results. The consumption prevalence of hookah was 15.5%, sedatives (without medical prescription) 40.7%, alcohol 37.7%, cigarette 34.6%, strong analgesics 10.2%, nas 9.7%, opium 8.7%, hashish 6.7%, ecstasy 6.6%, and heroin 4.9%.

Consumption prevalence for each drug type in Gilan: The prevalence was 20% for cigarette, 10.5% for alcohol, 2.4% for opium, 1.2% for ecstasy, 2% for hashish, and 0.3% for heroin. In Karaj city, the consumption prevalence was 53% for hookah, 24.8% for cigarette, 13.6% for alcohol, 2% for ecstasy, 2% for opium, 1.1% for hashish, 0.4% for crystal, and 0.2% for heroin.

In Nazarabad City, the consumption prevalence was found to be 23.1% for cigarette, 2% for opium, 1% for amphetamines and ecstasy, 0.5% for heroin, 0.3% for hashish and cocaine. The male and female drug consumption was 69.7% and 36.2%, respectively, representing a significant statistical difference (P < 0.05).

A study in Lahijan City showed that the consumption prevalence was 14.9% for cigarette, 2.4% for ecstasy, 4.1% for other drug types (with the highest rate of consumption for opium and hashish). In the Mahriz city of Yazd, the consumption prevalence among the male 3rd year high school students in 2008 was reported 6.8% for alcohol and 3% for psychoactive substances [Table 1].

Table 1.

The comparison of the prevalence of at-least-once drug use for each drug type in each studied region[9,10,11,12,13,14,15]

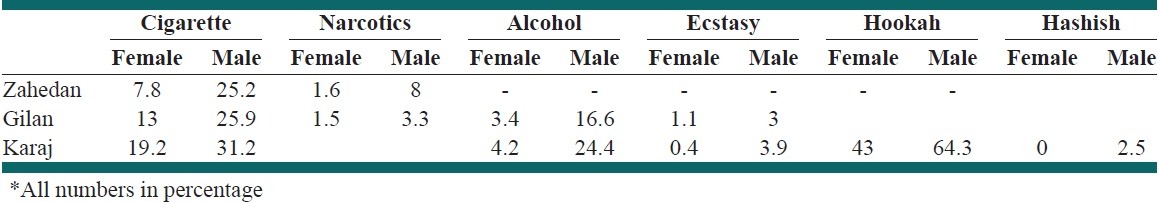

Drug consumption prevalence for each sex

A study in Zahedan also reported that at-least-once drug use prevalence was 1.6% and 8%, respectively, among females and males; and at-least-once cigarette smoking prevalence was 7.8% and 25.2%, respectively, for females with the mean age of 15.8 and males with the mean age of 16.

In Gilan, drug use, excluding cigarette, was reported 19.1% and 5.3%, respectively, for males and females, representing a significant statistical difference (P < 0.05). Furthermore, cigarette and drug use prevalence was 31.3% and 14.8% in males and females, respectively, showing that this rate was significantly higher in males (P < 0.05). Cigarette use prevalence was 25.9% and 3%, respectively, for male and female students. Alcohol consumption was 16.6% and 3.4% for males and females, respectively. Opium consumption was 3.3% and 1.5% among males and females, respectively, which was a significant statistical difference (…). Drug consumption, excluding cigarette, was 19.1% and 5.3%, respectively, for males and females, pointing to a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). Ecstasy use prevalence was reported 3% and 1.1%, respectively, for males and females, pointing to a statistically significant difference (P < 0.00081); 0.5% of males and 0.1% of females were heroin consumers, lacking any significant statistical difference (P > 0.05). In Karaj city, drug consumption prevalence was studied for each sex and drug type [Table 2].

Table 2.

The comparison of the prevalence of at-least-once drug consumption for each sex in each studied region

Drug consumption prevalence based on the age distribution in the studied populations

As the study conducted on students with the mean age of 16 in Zahedan showed that the highest incidence of the first experience of cigarette smoking belonged to the age of 14. A study in Kerman on students with the mean age of 17.9 about the age at the first experience yielded the following results for each drug type: 14 for cigarette, 14.6 for alcohol, 13.9 for hookah, 13.1 for sedatives, 15.3 for analgesics, 17 for ecstasy, 16.7 for hashish, 16.7 for heroin, 16.7 for opium, and 15.3 for naswar.

A study in Gilan indicated that drug and cigarette consumption had significantly increased in males aged 19 and above (88.9% of males aged 19 and above) (P < 0.05). According to a study in Nazarabad, the highest drug use onset was at the age of 15–16. The students’ mean age in the Karaj study was 16.9.

DISCUSSION

Exploring the MFT performed in the USA on the 10th graders showed that drug use had increased from 11% to 34% during 1992–1996. In 1998, 12.10% of the 8th year and 12.5% of the 10th graders and 25.611th % had experienced illegal drug use in the previous month.[16] It was shown that hashish, followed by opium and alcohol, is the most commonly used illicit drug.[17] The immediate necessity of planning for reducing the consumption of these drugs among students, and consequently among university students, has become increasingly important.

Investigating addictive drugs prevalence among university students showed the prevalence in the following order: Hookah (74.5%), cigarette (67.5%), opium (6.1%), alcohol (13.5%), psychoactive pills (5.26%), hashish and heroin. Entertainment constitutes the tendency for drug consumption in most cases (47.4%).[18] Results of a meta-analysis showed that 7% of Iranian adolescents regularly smoke, and 27% had experienced smoking. The increased cigarette use prevalence among Iranian adolescents is a major public health concern.[19] Paying attention to healthy recreations for adolescents and the youth has become increasingly important and needs planning for discouraging drug use. The cross-sectional prevalence of drug use in 1997 among American 12–17 years old adolescents was reported 11.4%, which was close to drug use prevalence, excluding cigarette.[16]

Another study showed that 56% of male and 42% of female university students were drug users, which accords with the present research with regard to the higher number of the males.[20] Since, the addiction problem is an old problem in other countries, it might be better to use the solutions practiced by them to speed up our reaction in cases which adhere to our culture and customs.

At-least-once alcohol use prevalence among the 8th year American students in 2005 and 2006 was 27% and 20%, respectively, increasing to 88% among the 12th year students.[20] The history of hashish consumption among the 8th, the 10th, and the 12th year students was 10%, 23%, and 36%, respectively, representing a remarkable difference with our country's students.[20] About 0.5% of the 8th year and 10% of the 12th year students consumed cocaine, and the consumption of amphetamines by the 12th year students was 1.5%,[20] being almost close to the consumption rate of Iranian students. The open consumption of hashish is common in France by almost one-third of the population (nearly 30%), compared with the average rate of 19% in European countries; also the consumption of ecstasy and cocaine has increased over 2000–2005, although it is 4% but yet remarkable.[21]

A study on students’ knowledge of narcotics in Rafsanjan and Yazd cities showed that 5.6% of Yazdian and 10% of Rafsanjanian students had at least one addicted person in their families. Also, 2.23% of the Yazdian and 7% of the Rafsanjanian students held that narcotics could also be useful.[22] The important issue here is the existence of an addicted relative and his or her leadership role in this regard; therefore, this point suggests the further importance of the sensitivity of this age group with regard to their dependence on narcotics.

It is noteworthy that Kerman City, compared to other studied cities, has received higher rates of drug use, such that opium and heroin consumption in this city has been, respectively, almost 4 and 5 times that of other cities. These statistics also hold true clearly with regard to ecstasy and alcohol consumption, each being almost 3 times that of Karaj and Gilan. Hashish consumption in the pre-university stage in this city is also higher than in other cities, which might be related to easier drug access in Kerman.

In the cities, in which sex-distinct studies were conducted, drug consumption by males had been, with no exception, far higher than by the females, which is, almost 4 times except for hookah and then cigarette. Of course, it is not possible to judge firmly about drug use general prevalence as a result of the few studies in this field; however, the important point is the relatively high drug use among the adolescent and effective group of the society, which deserves particular attention for education and intervention in this group. It has been observed that adolescent and young crystal users, compared to nonusers, show clinical symptoms, have less control and affection in their families, with excitable, aggressive and anxious personalities, and low accountability;[23] on the other hand, behavioral problems and friend influence are among the strongest risk factors of drug consumption among adolescent consumers.

Nevertheless, it is not clear to what extent the adolescent can manage the effect of behavioral problems and peer group interaction for refusing invitations for drug consumption.[24] It has been stated that using software programs would assist in the prevention and increasing the youth's skills for reducing drug use.[25] It has been shown that adolescent inclination to and consumption of drugs decrease significantly in the 1st year of educational intervention.[26] On the other hand, studies indicate that there is a relationship between the borderline personality disorder and the extent of drug abuse.[27]

Therefore, prevention programs for harm reduction, treatment and consultation as the main objective of the intervention structure should apply to consumers.[28] Also, emphasis should be laid upon the relationship between schools and parental care as important protective factors for adolescents’ health.[29] Adolescence is a growth period which is associated with a relatively high rate of drug use and its related disorders. Accordingly, recent progress in evaluating drug abuse among adolescents would continue for information sharing in the field of clinical and research services.[30] Therefore, attention to this group through coherent planning for damage prevention would still remain in priority.

CONCLUSIONS

Drug use is relatively high in the adolescent and effective group of the society, which requires particular attention and prompt and immediate intervention.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Poor RA. Tehran: Salaman; 2004. A guide for prevention and treatment of substance abuse; p. 13. 23-4, 32, 17, 53, 143, 51-4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siam SH. Drug abuse prevalence in male students of different universities in Rashtin 2005. Tabibe Shargh. 2006;8:279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madadi A, Nogani F. Tehran: Jameanegar; 2004. The Text Book of Addiction and Substance Abuse; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahangiri B. Tehran: Arjmand; 2002. A guide for cognition and treatment of addiction in Iran; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abasi A, Taziki S, Moradi A. Drug abuse pattern based on demographic factors in self-introducing addicts in Gorgan province, the scientific. J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2005;8:22–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farhadinasab A, Allahverdipour H, Bashirian S, Mahjoub H. Lifetime pattern of substance abuse, parental support, religiosity, and locus of control in adolescent and young male users. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2008;37:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammadpoorasl A, Nedjat S, Fakhari A, Yazdani K, Rahimi Foroushani A, Fotouhi A. Smoking stages in an Iranian adolescent population. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50:746–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simantov E, Schoen C, Klein JD. Health-compromising behaviors: Why do adolescents smoke or drink? identifying underlying risk and protective factors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1025–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.10.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Najafi K, Fekeri F, Mohseni R, Zarabo H, Nazefei F, Fagheirpour M, Shirazi M. Cigarette and drug consumption prevalence among high school students in Zahedan. Tabibe Sharq 6th Year. 2003:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziaaaldini H, Sharifi A, Nakhaee N, Ziaaaldini A. A. Theat-least-once narcotics consumption prevalence among male pre-university students in Kerman city. J Addict Health Summer Autumn 2nd Year. 2009:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Najafi K, Fekeri F, Mohseni R, Zarabi H, Nazefei F, Fagheirpour M, Sirazi M. Investigating drug consumption prevalence in high school students in Gilan province in the 2004-5 academic year. Gilans J Med Sci. 2006;16:67–79. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alaee Kharaiam R, Kadivar P, Mohammad Khani SH, Sarami GH, Alaee Kharaiam S. The extent of cigarette, hookah, alcoholic breavegaes, narcotics and stimulants among high school students. J Subst Abuse Addict Stud 5th Year. 2010:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghavidel N, Samadi M, Khoram Beiz AH, Asasi A, Feizi AR, Ahmadi R, et al. Investigating drugs consumption prevalence (Cigarette, Narcotics, Alcohol, Psychoactive Drugs) and its related factors among the Third year high school students in Nazarabad city between February 2008 until July 2009. Razi J Med Sci. 2012;19:28–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amiri M, Rezazadeh Z, Sadeghi S, Baneh FK. Ecstasy consumption prevalence among high school students in Lahijan city in 2004. Iran's Epidemiology, winter. 2004;1:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zohreh K, Poran H, Meitham K, Bagher MM. Investigating alcoholic and psychoactive substances among male high school students in the Mahriz city of Yazd in 2008. J Toloee Behdasht Paeez and Zemestan. 2008;8:33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drug Abuse: Origins & Interventions. In: Glantz MD, Hartel CR, editors; Mohammadi M, Nejat MR, Parsa N, Ghorbani M, Mirzaei A, Namati F, Najarian F, Naziri G, translators. Tehran: Research Center of Iran Drug Control Headquarters; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahimi Movaqar A, Elaheh SY, Masuood Y. A review of drug consumption status among the country's university students. Pazhohesh Q 5th Year. 2005;5:104–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jurgaitiene D, Zaborskis A, Sumskas L. Prevalence of drug use among students of vocational schools in Klaipeda city, Lithuania, in 2004-2006. Medicina (Kaunas) 2009;45:291–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazarzadeh M, Bidel Z, Ayubi E, Bahrami A, Jafari F, Mohammadpoorasl A, et al. Smoking status in Iranian male adolescents: A cross-sectional study and a meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. 10th ed. Vol. 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. Kaplan and Sadock's synapsisi of psychiatry: behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry; pp. 1294–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beck F, Legleye S. Sociology and epidemiology of consumption of psychoactive substances in adolescents. Encephale. 2009;35(Suppl 6):S190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(09)73470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yasini Ardekani SM, Zahra PM, Ahmadieyh MH. Investigating the extent of male high school students awareness of narcotics in Yazd and Rafsanjan cities. Yazds Third Public Congr Hazard Behav. 2012;8:27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zadeh SH. The comparison of clinical, family, personality, and training factors in ice consumers/non-consumers. J Subst Abuse Addict Stud 7th Year. 2012:53–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser B, Shelton KH, van den Bree MB. The moderating role of close friends in the relationship between conduct problems and adolescent substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schinke SP, Schwinn TM, Fang L. Longitudinal outcomes of an alcohol abuse prevention program for urban adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:451–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tebes JK, Feinn R, Vanderploeg JJ, Chinman MJ, Shepard J, Brabham T, et al. Impact of a positive youth development program in urban after-school settings on the prevention of adolescent substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:239–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sansone RA, Watts DA, Wiederman MW. Borderline personality symptomatology and legal charges related to drugs. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2014;18:150–2. doi: 10.3109/13651501.2013.847107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eskandarieh S, Nikfarjam A, Tarjoman T, Nasehi A, Jafari F, Saberi-Zafarghandi MB. Descriptive Aspects of Injection Drug Users in Iran's National Harm Reduction Program by Methadone Maintenance treatment. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42:588–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phuong TB, Huong NT, Tien TQ, Chi HK, Dunne MP. Factors associated with health risk behavior among school children in urban Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1–9. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.18876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winters KC. Advances in the science of adolescent drug involvement: Implications for assessment and diagnosis - Experience from the United States. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26:318–24. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361e814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]