Abstract

Objective To determine whether patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is better than routine care in providing effective analgesia for patients presenting to emergency departments with moderate to severe non-traumatic abdominal pain.

Design Pragmatic, multicentre, parallel group, randomised controlled trial

Setting Five English hospitals.

Participants 200 adults (66% (n=130) female), aged 18 to 75 years, who presented to the emergency department requiring intravenous opioid analgesia for the treatment of moderate to severe non-traumatic abdominal pain and were expected to be admitted to hospital for at least 12 hours.

Interventions Patient controlled analgesia or nurse titrated analgesia (treatment as usual).

Main outcome measures The primary outcome was total pain experienced over the 12 hour study period, derived by standardised area under the curve (scaled from 0 to 100) of each participant’s hourly pain scores, captured using a visual analogue scale. Pre-specified secondary outcomes included total morphine use, percentage of study period in moderate or severe pain, percentage of study period asleep, length of hospital stay, and satisfaction with pain management.

Results 196 participants were included in the primary analyses (99 allocated to PCA and 97 to treatment as usual). Mean total pain experienced was 35.3 (SD 25.8) in the PCA group compared with 47.3 (24.7) in the treatment as usual group. The adjusted between group difference was 6.3 (95% confidence interval 0.7 to 11.9). Participants in the PCA group received significantly more morphine (mean 36.1 (SD 22.4) v 23.6 (13.1) mg; mean difference 12.3 (95% confidence interval 7.2 to 17.4) mg), spent less of the study period in moderate or severe pain (32.6% v 46.9%; mean difference 14.5% (5.6% to 23.5%)), and were more likely to be perfectly or very satisfied with the management of their pain (83% (73/88) v 66% (57/87); adjusted odds ratio 2.56 (1.25 to 5.23)) in comparison with participants in the treatment as usual group.

Conclusions Significant reductions in pain can be achieved by PCA compared with treatment as usual in patients presenting to the emergency department with non-traumatic abdominal pain.

Trial registration European Clinical Trials Database EudraCT2011-000194-31; Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN25343280.

Introduction

Pain is defined as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.”1 Pain is the most common reason for patients presenting to the emergency department, but it is often not treated effectively.2 In a national survey of emergency department patients, 64% reported they were in pain.3 The Royal College of Emergency Medicine recommends that patients in severe pain should receive analgesia within 20 minutes of arrival in the emergency department, with regular reassessment and further action as required.4 However, effective analgesia is often not achieved, and almost half of patients surveyed thought that more could be done to treat their pain in the emergency department.3

Routine care for patients in moderate or severe pain often involves the administration of intravenous morphine, which is the standard opioid used in most hospitals and has been shown to be as effective as other opioids.5 In UK emergency departments, analgesia for patients in severe pain is provided by nurse delivered intravenous morphine administered over several minutes to achieve pain relief. This technique is safe and effective in the short term but places considerable demands on nursing time, particularly when repeated doses are needed.6

Once a patient is admitted to a hospital ward, severe pain may be managed using strong oral opioid analgesia or advanced pain management techniques. Best practice includes multimodal analgesia using regular paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in addition to opioids. The decision to admit a patient to the ward has been shown to delay the delivery of effective analgesia in the emergency department, suggesting that this group of patients is at particular risk of poor pain management.7

One solution may be to allow patients to deliver opioid analgesia themselves via a patient controlled analgesia (PCA) device. This device consists of a volumetric pump, which delivers a set intravenous dose of drug when a control button is pressed. The PCA system includes anti-siphon and anti-reflux valves to minimise the risk of inadvertent drug delivery. The pump has a safety “lockout” period when it will not deliver a further dose of opioid. A protocol commonly used throughout many UK hospitals, in settings other than the emergency department, uses a bolus dose of 1 mg morphine and a lockout period of five minutes and is derived from a broad evidence base.8 9 10 11 PCA has been shown to be more effective in providing pain relief compared with standard methods of analgesia delivery in areas such as postoperative care, burns, and terminal care.12 13 14 15 PCA is most effective in maintaining analgesia once baseline pain relief has been established.16

Despite the high prevalence of pain in emergency department patients, evidence relating to the use of PCA in this setting is very limited. Previous studies in this area have provided limited evidence of the short term utility of PCA in emergency patients but have not considered the management of pain over the subsequent hours after hospital admission.17 18 19 20 We identified no previous or current studies that combine emergency department care with ongoing ward care to assess quality of pain relief beyond four hours, and no detailed analysis of the cost effectiveness of PCA in this setting has been reported.

Most painful conditions leading to ED attendance may be subdivided into abdominal (visceral) and musculoskeletal (somatic) pain. Any effect of PCA, compared with usual care, may differ between visceral and somatic pain. Pain from skeletal injury tends to be well localised and proportionate to the degree of trauma in most patients. In contrast, visceral pain is poorly localised, often does not reflect the severity of pathology, and is associated with referred sensations. Strong autonomic and emotional responses to visceral pain often occur. These differences reflect the differing neurobiology of the two broad types of pain.21 We therefore considered patients with abdominal pain and patients with pain from musculoskeletal trauma as two separate populations and conceived two separately powered trials.

The aim of the study reported here was to compare morphine delivered by PCA with routine care (nurse titrated intravenous morphine in the emergency department and oral or parenteral morphine on the wards) in adult emergency patients who present in moderate or severe pain due to non-traumatic abdominal pain and are then admitted to an inpatient ward.

Methods

The detailed methodology and study protocol are described in a separate protocol paper.22

Study design

The study comprised two contemporaneous multicentre, open label, randomised trials of PCA versus routine care. Patients presenting to the emergency department requiring intravenous analgesia and admission to hospital, with either traumatic musculoskeletal injury or non-traumatic abdominal pain, were potentially eligible for inclusion. Key outcome measures were collected at baseline and then hourly for 12 hours. Although two separate trials were completed (one of patients presenting with traumatic musculoskeletal injuries, the other of patients with non-traumatic abdominal pain), both were based on the same protocol, which is outlined briefly below. Nevertheless, we have considered them as two separate trials because they were powered separately. This paper reports the trial of patients with non-traumatic abdominal pain.

Participants

Eligible patients were adults presenting to the emergency department with non-traumatic abdominal pain requiring intravenous opioid analgesia and hospital admission for at least 12 hours from the time of enrolment. We excluded patients with chronic pain and those with opiate tolerance; a full list of exclusion criteria is available in table 1 of the protocol paper.22 Study participants were patients who met the eligibility criteria and were willing and able to give informed consent.

Study recruitment

Patients underwent initial assessment and management, including initial pain relief, according to local policy. A research nurse screened patients on their arrival at the emergency department. After initial assessment and pain management, a research nurse approached them and gave them an information sheet detailing the study. If patients were happy to discuss the study further, any questions were answered at this stage. Patients were then fully assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria before written informed consent was obtained from those who were willing and able to participate. Patients who declined to take part were not obliged to give a reason, but the research nurse recorded any reasons given.

Study procedures and data collection

After informed consent was obtained, the first study pain score was recorded using a visual analogue scale, and the participant was randomised (using a secure web based randomisation system) to receive either PCA or routine care.

Participants in both groups then received instructions on how to complete subsequent visual analogue scale scores, which were entered into a mini flipchart (the participant was instructed to turn the page of the flipchart after an entry was made, so the previous score was not visible for comparison). Participants were asked to record their pain scores on deep breathing. Electronic timers (Casio F-91W digital watches) issued a bleep every hour as a reminder to the participant to complete the hourly score, but this bleep was not typically loud enough to wake the participant from sleep. The visual analogue scale was presented as a 10 cm horizontal line with verbal anchors at each end of “no pain” and “worst pain possible.” Participants were instructed to select the point along the line (and mark this point with a pen with a single vertical line) that reflected their current pain perception. Participants recorded visual analogue scale pain scores at 60 minute intervals over a 12 hour period. Participants were also instructed on how to record periods asleep, retrospectively, on the booklet by using a tick box on each page.

Most other outcome data were collected for 12 hours from the point at which the first study pain score was completed. Opioid use was recorded from the prescribed drugs administered as recorded on the patient’s drug chart during the study period (including that prescribed pre-admission). We used study observation charts, based on standard hospital charts, for all study participants; these were completed as part of routine care by emergency department nurses in the emergency department and then by ward nurses after inpatient ward admission. Observations followed the standard of care in each centre. Typically, this involved observations hourly for four hours, two hourly for eight hours, and four hourly thereafter. In practice, this meant hourly vital signs in the emergency department and two hourly vital signs for the rest of the study period. Observations included heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygen saturations, oxygen flow rate, sedation score, and nausea score (0-2). A research nurse reviewed the observation charts after the 12 hour study period and transcribed out of range results into the study case report form.

Where possible, at the end of the 12 hour study period (or the following morning as appropriate), a research nurse visited participants in both groups to facilitate collection of study data. The final page of the data collection booklet included a five point pain management satisfaction score ranging from “perfectly satisfied” to “not satisfied at all.” Following the participant’s discharge, the research nurse obtained the length of stay in hospital and final diagnosis at discharge from the patient administration system (or equivalent) and recorded them in the case report form.

Interventions

Participants allocated to receive routine care were prescribed intravenous morphine while in the emergency department and oral morphine (or subcutaneous/intramuscular for those nil by mouth) when transferred to the hospital ward. Participants randomised to the PCA group received instruction from the research nurse in how to operate the PCA device, which was set up by the emergency department nurses and started with a 1 mg morphine bolus and a five minute lockout. PCA was continued for a minimum period of 12 hours; in practice, the clinical team reviewed ongoing requirement for PCA the following morning. Participants in both groups were prescribed multi-modal analgesia in addition, including paracetamol and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (unless contraindicated), and were also prescribed antiemetics as required.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the total pain experienced over the 12 hour study period, as captured by the hourly completion of a visual analogue pain rating scale. We derived this by plotting data as a graph of visual analogue scale pain against time and calculating the area under the curve for each participant. This is a measure of overall pain experienced during the study period.23

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures included total opioid dose, out of range vital signs, patients satisfaction with pain management, proportion of study period in moderate/severe pain (that is with visual analogue scale >4.4 cm), proportion of study period spent sleeping, and length of hospital stay.

Randomisation, allocation concealment, and blinding

Randomisation (one to one) to either PCA or routine care was done via a secure web based randomisation system. Research team members accessing the randomisation website did not know the allocation for an individual patient until the relevant details were entered and recruitment confirmed.

As pain experience over subsequent hours may be affected by the time of day of recruitment (those starting the trial later in the day would be scoring their pain during night hours when they may spend a greater proportion of time asleep), randomisation was stratified by time of the first recorded pain score (morning or afternoon/evening), as well as by recruitment centre. Blinding was not possible for this study owing to the nature of the intervention.

Sample size

We derived the primary outcome by plotting data as a graph of visual analogue scale pain against time and calculating an area under the curve for each participant. This is a measure of overall pain experienced during the study period.23

Very few studies have considered the question of what reduction in area under the curve might be a clinically significant analgesic effect. One study by Camu et al showed that a 20% reduction in the area under the curve for pain on movement was associated with a 26% absolute increase in the proportion of patients reporting their global rating of pain relief as very good or excellent (P=0.01).24 Conservatively, therefore, we chose a difference in area under the curve of 15% between PCA and routine care groups as being of clinical significance. On a standardised area under the curve (scoring between 0 and 100), we expected the routine care group to have an average score of about 40 units, so 15% equates to a six point reduction. A standard deviation can be estimated from the research by Camu et al as about 15 units. On the basis of these assumptions, and using a two tailed, two sample t test, with a type 1 error rate of 0.05, a sample size of 100 patients per group provides sufficient power (80%) to detect a between group difference of 15%.

Statistical analyses

We report and present data according to the relevant CONSORT statement.25 The primary analyses were all pre-specified in a detailed statistical analysis plan approved by the Data Monitoring Committee before the analyses started. They followed an intention to treat approach, with the intent to treat population defined as all participants who completed the baseline and at least one subsequent pain visual analogue scale. Primary analyses were adjusted for the stratification factors (centre and time of baseline pain score (morning or afternoon/evening)) as fixed effects; we also present unadjusted analyses. We present 95% confidence intervals for between group differences, with the significance level for hypothesis testing set at 5%.

We used the area under the curve approach to capture the primary outcome measure of total pain experienced and compared it between PCA and routine care groups by using analysis of covariance, including the two stratification variables and the baseline pain score as covariates. We did this analysis blinded to the allocated group. We calculated the area under the curve by using the “trapezoidal” rule, using straight lines to join visual analogue scale scores and calculating the area under them for the 12 hour period. In general, where one or more hourly pain scores were not recorded, we imputed values by linear interpolation if scores were recorded either side and by last observation carried forward if scores were missing at the end of the 12 hour period, except that such final scores were recorded as zero if the participant was discharged (or self discharged). These conventions were agreed with the Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee in a detailed strategy; a member of the Trial Management Group, blinded to participants’ allocated group wherever possible, categorised reasons for missing data.

We similarly compared continuous secondary outcomes between the two groups by using analysis of covariance, with adjustment for the two stratification variables. Given that some visual suggestion of potential violations of the linear model assumptions existed, we also produced bootstrapped confidence intervals for the between group differences for each outcome measure. In each instance, little difference existed between the normal based and bootstrapped confidence intervals; for simplicity, we present only the normal based confidence intervals.

For the analysis of participants’ satisfaction with pain management, we recoded the five point scale (ranging from “perfectly satisfied” to “not at all satisfied”) into two categories, combining “perfectly satisfied” and “very satisfied” into one category and the others into a second category. We used binary logistic regression to determine the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for the group effect, with adjustment for the stratification variables.

Sensitivity analyses

We did two pre-specified sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome measure: the first scored pain as zero for periods of sleep (sensitivity 1); the second imputed missing pain scores due to transfers to theatre by using linear interpolation from the last recorded pain score to zero at the 12 hour time point (sensitivity 2).

At the request of the Data Monitoring Committee, we also did two further sensitivity analyses. The first of these included the data from the four participants in the hospital that was excluded in the primary analyses (see below; sensitivity 3). The second excluded 35 participants whose baseline pain score seemed to be recorded after randomisation. Data validation checks showed this possibility for some patients, although verification was not straightforward as different sources were used to record the times of baseline pain score and randomisation. We considered that if the baseline pain score had a recorded time of more than five minutes after the recorded time of randomisation, this probably indicated that the score was recorded after randomisation; these are the 35 cases that were excluded in sensitivity 4.

Patient involvement

During the design of this study, a patient representative contributed to the development of the grant application and, later, to the study protocol and participant facing documentation after funding had been awarded. We also had a patient representative on the Trial Steering Committee, who helped to oversee progress of the trial and provided a patient’s perspective on aspects of trial conduct. A lay summary of the study findings will be made available to participants at www.medicalresearchplymouth.org.uk.

Results

Recruitment

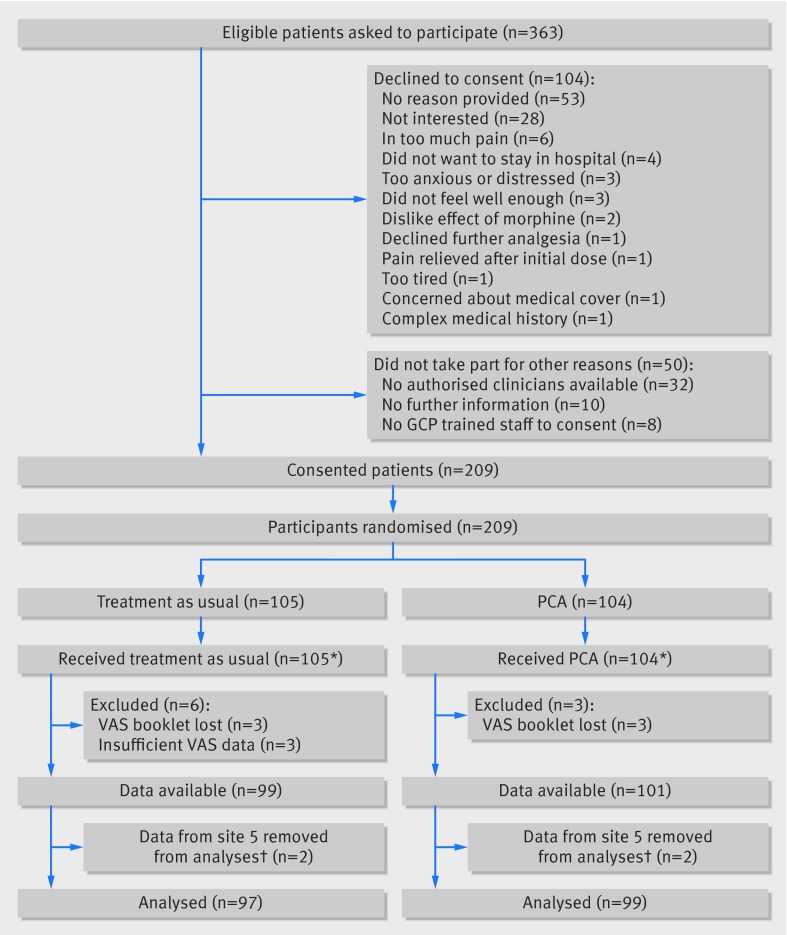

The figure outlines the flow of participants in the trial. Recruitment took place from July 2011 to May 2013. Of 363 eligible patients who were approached to participate, 104 (28%) declined and a further 50 (14%) did not participate for other reasons. The remaining 209 patients consented and were randomised: 104 to PCA and 105 to treatment as usual. Three participants in the PCA group and six participants in the TAU group were not included in the statistical analyses, owing either to the booklets with the pain scores going missing or to the participant completing the pain score only once. One participating hospital experienced some local difficulties in implementing the protocol as intended, and only four patients were recruited at this site, making the pre-specified adjustment for centre impossible. On the advice of the Data Monitoring Committee, we excluded data from this site from the primary analyses. This left a total of 196 participants, 99 randomised to PCA and 97 randomised to treatment as usual, for the primary statistical analyses.

Flow of participants through study. GCP=good clinical practice; PCA=patient controlled analgesia; VAS=visual analogue scale. *4 participants transferred between treatment groups during 12 hour study period: all 4 patients discontinued PCA and went into treatment as usual. †Following advice from the Data Monitoring Committee’s independent statistician, participants recruited at site 5 were excluded

Baseline characteristics

Participants were aged 18 to 75 years, and two thirds were women (table 1). At the time of emergency department admission, participants’ mean verbal rated pain score was 8.0 (range 0-10). The median time from arrival in the ED to randomisation was 152 (29-768) minutes. By the time participants completed their first study pain score, the median overall visual analogue pain score was 5.2 (0-10). The two randomised groups were similar in terms of most characteristics, with a slight difference in median baseline visual analogue scale pain scores: 4.8 (0-9.8) in the PCA group and 6.1 (0-10) in the treatment as usual group.

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic data. Values are percentages (numbers) unless stated otherwise

| Treatment as usual (n=97) | Patient controlled analgesia (n=99) | All (n=196) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Female sex | 66 (64) | 67 (66) | 66 (130) |

| Mean (SD; range) age, years | 41.3 (15.3; 18-75) | 41.5 (15.4; 18-72) | 41.4 (15.3; 18-75) |

| Median (IQR; range) verbal rated pain score (0-10, as recorded on hospital administration system) | 8 (6-9; 0-10) (n=93) | 8 (6-9; 0-10) (n=95) | 8 (6-9; 0-10) (n=188) |

| Median (IQR; range) visual analogue pain score (at time of consent), cm | 6.1 (3.2-7.7; 0-10) | 4.8 (2.2-6.8; 0-9.8) | 5.2 (2.5-7.3; 0-10) |

| Time of recruitment | |||

| Morning (0600-1159) | 36 (35) | 38 (38) | 37 (73) |

| Afternoon (1200-2200) | 64 (62) | 62 (61) | 63 (123) |

| Mean (SD; range) time from arrival in emergency department to randomisation, minutes | 162.4 (83.9; 29-586) | 164.7 (83.4; 54-768) | 163.6 (83.5; 29-768) |

| Recruitment centre | |||

| Centre 1 | 63 (61) | 67 (66) | 65 (127) |

| Centre 2 | 16 (16) | 15 (15) | 16 (31) |

| Centre 3 | 11 (11) | 11 (11) | 11 (22) |

| Centre 4 | 9 (9) | 7 (7) | 8 (16) |

| Clinical diagnosis | |||

| Bowel pathology (including obstruction, diverticular disease, hernia with obstruction) | 14 (14) | 16 (16) | 15 (30) |

| Gall bladder pathology (including biliary system) | 15 (15) | 13 (13) | 14 (28) |

| Renal or ureteric pathology (stone passed) | 14.4 (14) | 14 (14) | 14 (28) |

| Pancreatic pathology | 8 (8) | 9 (9) | 9 (17) |

| Appendix pathology | 7 (7) | 6 (6) | 7 (13) |

| Renal or ureteric pathology | 8 (8) | 4 (4) | 6 (12) |

| Gynaecological pathology (including ovarian) | 7 (7) | 4 (4) | 6 (11) |

| Oesophagitis or gastritis | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (8) |

| Abdominal pain (not further specified) | 14 (14) | 20 (20) | 17 (34) |

| Other (including postoperative pain, hepatic neoplasm) | 6 (6) | 9 (9) | 8 (15) |

| Preadmission analgesia | |||

| Mean (SD; range) morphine (mg): | |||

| Participants with pre-admission morphine | 9.1 (6.1; 1.7-30.0) (n=35) | 8.9 (4.2; 2.5-20.0) (n=33) | 9.0 (5.2; 1.7-30.0) (n=68) |

| All participants | 3.3 (5.7; 0-30) | 3.0 (4.8; 0-20) | 3.1 (5.3; (0-30) |

| At least one dose in 24 hours before emergency department arrival: | |||

| Analgesic gas | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | 5 (10) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 15 (15) | 9 (9) | 12 (24) |

| Paracetamol | 34 (33) | 32 (32) | 33 (65) |

| Weak opioid | 14 (14) | 9 (9) | 12 (23) |

Primary outcome (including sensitivity analyses)

Mean total pain experienced in the PCA group was 35.3 (SD 25.8) compared with 47.3 (24.7) in the treatment as usual group (table 2). The primary analysis, with adjustment for centre, time of baseline pain score, and baseline pain score, showed a statistically significant between group difference of 6.3 (95% confidence interval 0.7 to 11.9) units. In both pre-specified sensitivity analyses, the between group difference remained statistically significant. Including the data from the fifth hospital slightly increased the magnitude of the adjusted between group difference, whereas excluding the data from the 35 participants with more than five minutes between time of baseline pain score and time of randomisation did not change the magnitude of the between group difference, although the difference was no longer statistically significant at the 5% level.

Table 2.

Primary outcome of total pain experienced (standardised area under curve, maximum score 100): primary and sensitivity analyses

| Analysis | Mean (SD; range) | Adjusted analysis* | Unadjusted analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment as usual (n=97) | Patient controlled analgesia (n=99) | Mean difference† (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference† (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Primary | 47.3 (24.7; 1.0-99.5) | 35.3 (25.8; 1.5-94.8) | 6.3 (0.7 to 11.9) | 0.027 | 11.9 (4.8 to 19.0) | 0.001 | ||

| Sensitivity 1‡ | 37.7 (21.5; 0.7-96.3) | 28.2 (22.3; 1.5-83.6) | 5.2 (0.1 to 10.2) | 0.047 | 9.6 (3.4 to 15.7) | 0.003 | ||

| Sensitivity 2§ | 46.7 (24.7; 0.9-99.5) | 34.7 (25.5; 1.5-94.8) | 6.5 (0.9 to 12.0) | 0.022 | 12.0 (4.9 to 19.1) | 0.001 | ||

| Sensitivity3¶ | 47.7 (24.6; 1.0-99.5) (n=99) | 35.2 (25.6; 1.5-94.8) (n=101) | 7.2 (1.6 to 12.8) | 0.012 | 12.5 (5.5 to 19.5) | 0.001 | ||

| Sensitivity 4** | 49.2 (23.3; 1.0-99.5) (n=79) | 36.7 (25.7; 1.5-94.8) (n=82) | 6.3 (−0.2 to 12.7) | 0.056 | 12.5 (4.8 to 20.1) | 0.002 | ||

*Adjusted for stratification variables (time of first pain score and recruitment centre) and baseline pain score.

†Treatment as usual minus patient controlled analgesia.

‡Pain scored as zero for periods of sleep.

§Missing pain scores for theatre withdrawals imputed using linear interpolation from last recorded pain score to zero at 12 hour time point.

¶Includes data from four participants in centre 5.

**Excludes data from 35 participants with >5 minutes between time of first pain score and time of randomisation.

Secondary outcomes

Participants in the PCA group used significantly more morphine on average compared with the treatment as usual group, in terms of total morphine (morphine given pre-admission, from time of admission to time of recruitment, and during the study period) (adjusted mean increase of 12.3 (95% confidence interval 7.2 to 17.4) mg) and morphine used during the 12 hour study period (adjusted mean increase of 12.8 (8.3 to 17.2) mg) (table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes

| Outcome | Mean (SD; range) | Adjusted analysis* | Unadjusted analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (n=97) | PCA (n=99) | Mean difference† (95% CI) | P value | Mean difference† (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Total morphine (mg)‡ | 23.6 (13.1; (3.0-60.0) | 36.1 (22.4; 8.0-106.3) | −12.3 (−17.4 to −7.2) | <0.001 | −12.6 (−17.8 to −7.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Total morphine during 12 hour study period (mg) | 10.7 (9.6; (0-40.0) | 23.6 (20.3; 0 to 96.3) | −12.8 (−17.2 to −8.3) | <0.001 | −12.9 (−17.4 to −8.4) | <0.001 | ||

| Percentage of study period with pain VAS >4.4 cm | 46.9 (30.5; 0-100) | 32.6 (32.5; 0-100) | 14.5 (5.6 to 23.5) | 0.002 | 14.3 (5.4 to 23.1) | 0.002 | ||

| Percentage of study period asleep | 18.6 (19.2; 0-84.6) | 19.7 (18.7; 0-76.9) | −1.5 (−6.6 to 3.5) | 0.550 | −1.1 (−6.4 to 4.3) | 0.693 | ||

| Length of hospital stay (days)§ | 3.6 (3.0; 0.2-13.5) | 3.3 (3.0; 0.1-13.0) | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.1) | 0.572 | 0.2 (−0.6 to 1.1) | 0.589 | ||

PCA=patient controlled analgesia; TAU=treatment as usual; VAS=visual analogue scale.

*Adjusted for stratification variables (time of first pain score and recruitment centre).

†TAU minus PCA.

‡Sum of pre-admission morphine, morphine from time of admission to time of recruitment, and morphine delivered during 12 hour study period.

§One outlier excluded from TAU group (length of hospital stay of 88 days).

A higher proportion of the PCA group than the treatment as usual group had at least one out of range vital sign (64/99 (65%) v 38/97 (39%)). In particular, a significantly greater proportion of participants in the PCA group had one or more episodes of nausea compared with the treatment as usual group (adjusted odds ratio 4.99, 95% confidence interval 2.45 to 10.15). One participant in the treatment as usual group also had one instance of hypoxia.

On average, participants in the PCA group spent less of the study period in moderate or severe pain compared with participants in the treatment as usual group (mean difference of 14.5%, 5.6% to 23.5%). Adjusting for the baseline pain score reduced the mean difference to 7.3% (0.3% to 14.4%), but the difference remained statistically significant. We found no evidence of differences between the groups in terms of percentage of the study period spent asleep or the length of hospital stay.

Participants allocated to the PCA group were significantly more likely to report being perfectly or very satisfied with the management of their pain compared with participants in the treatment as usual group (73/88 (83%) v 57/87 (66%); adjusted odds ratio 2.56, 1.25 to 5.23).

Adverse events

Six non-serious adverse effects were reported. All were mild; all were related to morphine and were expected: four were itching, one was a rash, and one was urticaria at the cannulation site.

Discussion

This study found that PCA provided more effective analgesia than routine care in emergency patients admitted to hospital with abdominal pain. We found a modest reduction in overall pain scores, as well as a significant reduction in the amount of time that participants spent in moderate and severe pain. Participants in the PCA group used significantly more morphine, which may reflect under-treatment in the routine care group. Satisfaction with pain management showed a marked difference, with a significantly higher satisfaction in the PCA group. Patients in the PCA group were more than twice as likely to be very or perfectly satisfied with their pain management, suggesting that patients may value a degree of autonomy in the ability to control their pain.

Strengths and limitations of study

The main strength of this study was that it combined care in the emergency department with ongoing care once the patient was admitted to a hospital ward. It investigated the effects of PCA started in the emergency department but also subsequently beyond the patient’s emergency department stay. This is the first study to look at this vulnerable period between emergency care and inpatient management.

The lack of blinding in this study could be viewed as a limitation, but blinding patients or clinicians to the treatment allocation was not practical. Despite the strict randomisation with concealed allocation, the two groups were not perfectly balanced on baseline pain scores. However, baseline pain score was included as a covariate in the primary analysis and adjusting for baseline pain score did not alter the findings for the secondary outcomes. During data validation, it became apparent that the baseline pain score may have been recorded after the time of randomisation in several cases, despite the study protocol clearly indicating that the first study pain score was to be recorded at the time of consent and before randomisation. However, further analyses showed no evidence to suggest that the presumed timing of the baseline pain score (that is, before or after the time of randomisation) accounted for the difference in mean baseline pain scores between allocated groups.

Comparisons with other studies and implications of this study

Few previous studies have attempted to investigate PCA in emergency patients, and none has looked beyond the emergency department phase of care. Only one study has previously investigated patients with abdominal pain. This North American study randomised 211 emergency patients with abdominal pain to one of three groups; standard care, PCA standard dose (1 mg) bolus, or PCA higher dose (1.5 mg) bolus.18 It found a significant reduction in pain in both PCA groups compared with standard care, but the trial collected data during the patients’ emergency department stay only and did not continue to follow them after admission to a hospital ward.

Although this study has shown clear benefits in the use of PCA in this group of patients, we emphasise that the routine care arm of this study may not represent real world emergency care. All patients who were allocated to the routine care group were treated with multimodal analgesia according to the hospital’s guideline, but in many cases and for a variety of reasons this may not always occur in normal practice. There may also have been a Hawthorne effect on the nurses who were looking after the patients in the routine care group, and their behaviour may have been influenced by this.

Conclusions

This study has shown that PCA is more effective than routine care in managing pain in the emergency department and during the following hours of hospital admission in patients with non-traumatic abdominal pain. This is the first study to follow-up participants from emergency admission to the hospital ward; it has therefore given a pragmatic answer to the question of whether PCA should be used in these patients.

What is already known on this topic

Pain is common in patients presenting to emergency departments, but it is often not treated effectively

Patient controlled analgesia (PCA) has been shown to be more effective than standard methods of analgesia delivery in other clinical areas, but very limited evidence exists relating to its use in the emergency setting

No previous trials have reported the use of PCA from emergency admission to the hospital ward

What this study adds

PCA was more effective than routine care in managing pain in patients presenting to the emergency department with non-traumatic abdominal pain

This is the first study to follow up participants from emergency admission to the hospital ward; it has therefore given a pragmatic answer to the question of whether PCA should be used in these patients

We acknowledge the support of the National Institute for Health Research, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network. We are grateful for the help and support of the PASTIES research team, who include the following. Principal investigators: Andrew Appelboam, Jason Kendall, Tim Harris, and Tim Coats; Trial Steering Committee: Clifford Mann, Jason Kendall, Chris Rollinson, Hamish McPhie (patient representative), and Karen Higginson (patient representative); Data Monitoring Committee: Suzanne Mason, Lesley Colvin, and Chris Metcalfe; Plymouth team: Katy Pereira, Nicola Scholes, Fiona Haddon, Stuart Quarterman, Rae Morgan, Anthony Kehoe, and Simon Horne. Exeter team: Steve Harvey, Jennie Small, and Caroline Renton; Bristol team: Vanessa Lawlor, Emmy Oldenbourg, Hannah Skuse, Anna Gilbertson, David Rea, Sarah Hierons, Ruth Worner, Vicki Williams, and Stephanie Lambert; London team: Jason Pott, Nicola Harvey, Geoffrey Bellhouse, Imogen Skene, Ben Bloom, and Mihai Chiriac; Leicester team: Rachel Lock and Catriona Bryceland.

Contributors: JES conceived the study, was the chief investigator, and co-wrote the initial manuscript. MR and RS co-wrote the initial protocol and were involved with the conduct of the study. CH was the initial trial manager and helped to develop the study protocol to its final version. PE, AB, and CP gave methodological advice, edited the final protocol, and edited versions of this manuscript. SC was the trial statistician, was involved in conduct of the study from its inception, and contributed to the manuscript. VE took over as trial manager during the study. LC was the data manager and helped to draft the results. JB contributed to the initial and final drafts of the protocol and provided advice on patient recruitment and the effective conduct of the study. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. JES is the guarantor.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s research for patient benefit (RfPB) programme, grant reference number PB-PG-0909-20048. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work other than that described above; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the South Central-Southampton A Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 11/SC/0151).

Transparency statement: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: Patient level data are stored within the PASTIES database, developed by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit on a secure server maintained by Plymouth University. Presented data are fully anonymised. No consent for data sharing with other parties was obtained, but the corresponding author may be contacted to forward requests for data sharing.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h3147

References

- 1.Merskey H. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain 1979;6:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd KH, Ducharme J, Choiniere M, et al. Pain in the emergency department: results of the pain and emergency medicine initiative (PEMI) multicenter study. J Pain 2007;8:460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Care Quality Commission. Accident and emergency 2012. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121213135835/http://www.cqc.org.uk/public/reports-surveys-and-reviews/surveys/accident-and-emergency-2012.

- 4.College of Emergency Medicine. Clinical standards for emergency departments. 2014. www.rcem.ac.uk/Shop-Floor/Clinical%20Standards.

- 5.Plummer JL, Owen H, Ilsley AH, et al. Morphine patient-controlled analgesia is superior to meperidine patient-controlled analgesia for postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 1997;84:794-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lvovschi V, Aubrun F, Bonnet P, et al. Intravenous morphine titration to treat severe pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:676-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arendts G, Fry M. Factors associated with delay to opiate analgesia in emergency departments. J Pain 2006;7:682-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen H, Plummer JL, Armstrong I, et al. Variables of patient-controlled analgesia: 1. Bolus size. Anaesthesia 1989;44:7-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen H, Szekely SM, Plummer JL, et al. Variables of patient-controlled analgesia: 2. Concurrent infusion. Anaesthesia 1989;44:11-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macintyre PE. Safety and efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:36-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, et al. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain: a quantitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2001;45:795-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choiniere M, Grenier R, Paquette C. Patient-controlled analgesia: a double-blind study in burn patients. Anaesthesia 1992;47:467-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudcova J, McNicol E, Quah C, et al. Patient controlled opioid analgesia versus conventional opioid analgesia for postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;4:CD003348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White PF. Use of patient-controlled analgesia for management of acute pain. JAMA 1988;259:243-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolin SJ, Cashman JN, Bland JM. Effectiveness of acute postoperative pain management: I. Evidence from published data. Br J Anaesth 2002;89:409-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, et al. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2003;120:744-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans E, Turley N, Robinson N, et al. Randomised controlled trial of patient controlled analgesia compared with nurse delivered analgesia in an emergency department. Emerg Med J 2005;22:25-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birnbaum A, Schechter C, Tufaro V, et al. Efficacy of patient-controlled analgesia for patients with acute abdominal pain in the emergency department: a randomized trial. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman NH, DeSilva T. A randomized controlled trial of patient-controlled analgesia compared with boluses of analgesia for the control of acute traumatic pain in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2012;43:951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahman NH, DeSilva T. The effectiveness of patient control analgesia in the treatment of acute traumatic pain in the emergency department: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Emerg Med 2012;19:241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikandar S, Dickenson AH. Visceral pain: the ins and outs, the ups and downs. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:17-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JE, Rockett M, Squire R, et al. PAin SoluTions In the Emergency Setting (PASTIES); a protocol for two open-label randomised trials of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) versus routine care in the emergency department. BMJ Open 2013;3:pii:e002577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews JN, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, et al. Analysis of serial measurements in medical research. BMJ 1990;300:230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camu F, Van Aken H, Bovill JG. Postoperative analgesic effects of three demand-dose sizes of fentanyl administered by patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth Analg 1998;87:890-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]