Abstract

The study was designed to identify any trends of injury type as it relates to the age and trade of construction workers. The participants for this study included any individual who, while working on a heavy and highway construction project in the Midwestern United States, sustained an injury during the specified time frame of when the data were collected. During this period, 143 injury reports were collected. The four trade/occupation groups with the highest injury rates were laborers, carpenters, iron workers, and operators. Data pertaining to injuries sustained by body part in each age group showed that younger workers generally suffered from finger/hand/wrist injuries due to cuts/lacerations and contusion, whereas older workers had increased sprains/strains injuries to the ankle/foot/toes, knees/lower legs, and multiple body parts caused by falls from a higher level or overexertion. Understanding these trade-related tasks can help present a more accurate depiction of the incident and identify trends and intervention methods to meet the needs of the aging workforce in the industry.

Keywords: aging workforce, construction, injury, occupation, work safety

Construction is one of the largest industries in the United States and employs about 9.1 million workers [1]. Construction employment is expected to grow by approximately 2 million wage-and-salary jobs between 2010 and 2020, more than double the growth rate projected for the overall US economy [1]. The construction industry is consistently ranked among the most dangerous occupations and accounts for a disproportionately large percentage of all occupationally related illnesses, injuries, and deaths. Moreover, the number and proportion of older workers in the United States is increasing [2]. Between 1985 and 2010, the average age of construction workers jumped from 36.0 years to 41.5 years [1]. As workers age, many of the tasks they used to complete easily may become increasingly difficult. According to the United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [3], physically demanding jobs present the danger of more severe injuries and longer recovery times incurred by older workers. Physical activities associated with individual trades may also increase the cases of worker injury and may lead to worker carelessness or shortcuts. Factors that increase the aging worker's potential for injury include muscle weakness, balance problems, vision problems, and side effects from medicines. Older worker groups had lower injury rates, but when older workers were injured, recovery times were longer compared with those of younger workers [4,5]. Also, the population of older workers that forgo retirement because of various factors (e.g., better health, changes in social or retirement policy, lack of younger replacement workers, economic need, or desire to change careers) is growing [5]. In many ways, the trend of older workers remaining in the workforce can be beneficial for the nation’s economy. Their expertise is valuable, and many companies prefer to keep their older employees as long as possible [6]. Despite the challenges of the aging workforce, there are only a few studies about injury-related absences in construction and even fewer as the injuries relate to the age and trade of heavy/highway contractors. The purpose of this study was to identify any trends of injury type as it relates to the age and trade of the heavy construction workers.

A heavy highway project in the Midwestern United States was used to gather the injury information. A total of 196 construction contractors had been enrolled in the project at the time, and > 2,000 individual workers had completed the mandatory job site orientation. The types of contractors involved in the project included the following: general contractors, structural steel, rebar installation, earthmoving, concrete and steel demolition, electrical, painting/staining, engineering, bridge builders, underground boring, caisson drillers, trucking, and concrete flat work, which account for the highest numbers of employees with many small tier subcontractors involved thereafter. In order to document the injury cases, a spreadsheet was developed as one research method in this study. The spreadsheet was designed to gather as much information as possible about the injury and individual at the time of the incident. The primary focus was to present specific information about the injury and the individual, the type of work being completed, and the occupation to identify possible trends in relation to injuries, age, and occupation. It begins by collecting background information about the individual: age, sex, wage rate, trade, and forms of training completed. It is followed by medical information such as date of the injury, injury time, medical only or compensation, event date to hire, event to close, associated costs, and lost time days. Specific information about the injury follows in the form of injury cause, type of hazard, injury area, and type of damage. The collection of data from the injuries, specific to the project was from October 2004 to November 2006. During this period, a total of 143 injury reports were collected.

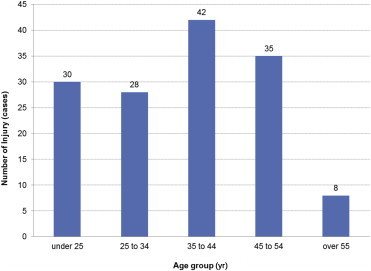

The first section of the information presented identifies the age groups of the injured workers and the frequency of injuries within the age groups (average age = 38.3 years; standard deviation = 11.3 years). Fig. 1 depicts the following age groups: < 25 years with 30 injuries (21%), 25–34 years with 28 injuries (20%), 35–44 years with 42 injuries (29%), 45–54 years with 35 injuries (25%), and > 55 years with eight injuries (6%). The two age groups with the highest number of injuries were 35–44 years and 45–54 years. These injuries make up 54% of all reported incidents (77 injuries of 143 total cases; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Injuries by age group.

Data were also collected at the time of the injury regarding the type of work being performed as it relates to the individual trade of the injured worker. The four trade groups with the highest injury rates were laborers, carpenters, iron workers, and operators. The laborers accounted for 45% (65 injuries), followed by carpenters with 23% (33 injuries), iron workers with 11% (16 injuries), and operators with 10% (15 injuries) of the total injuries. The remaining trade groups accounted for the remaining 11% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of age group and trade-related injured body part, injury type, and cause

| Age group (y) | Trade | Body part (freq.) | Injury type | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | Laborers | Fingers/hand/wrist (6) Eye (4) Knee (3) Shoulder (2) Foot/toes (2) Multiple body parts (1) |

Cut/laceration, contusion Foreign body/matter Sprains/strains Sprains/strains, cut/laceration Contusion/crushing bruise Dermatitis/rash/inflammation |

Struck against an object, caught in between object Rubbed or abraded Fall from higher level, sudden muscular movements Overexertion, struck against an object Struck by an object Contact with temperature extremes |

| Carpenters | Fingers/hand/wrist (7) Back (1) Foot/toes (1) Forearm/upper arm (1) |

Cut/laceration, Contusion Sprains/strains Contusion/crushing bruise Cut/laceration |

Struck against an object, struck by an object Overexertion (lifting objects) Struck by an object Stuck against an object |

|

| Iron workers | Back (1) Mouth (1) |

Sprains/strains Fracture |

Overexertion Struck by an object |

|

| 25–34 | Laborers | Fingers/hand/wrist (5) Back (1) Eye (1) Lower leg (1) Elbow (1) Chest (1) Knee (1) Multiple body parts (1) |

Cut/laceration, sprains/strains Sprains/strains Foreign body/matter Burn (serious) Contusion/crushing bruise Inflammation/irritation Contusion/crushing bruise Multiple injuries |

Caught in between object, rubbed/abraded Overexertion (lifting objects) Rubbed/abraded Rubbed/abraded Fall from higher level (into shaft/floor opening) Bodily reaction Struck by an object Fall on same level (fall to the walkway) |

| Carpenters | Fingers/hand/wrist (2) Forearm/upper arm (1) Chest (1) Knee (1) |

CTS, puncture Contusion/crushing bruise Sprains/strains Contusion/crushing bruise |

Repetition/pressure, cut/puncture by hand tool Struck by an object Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) Struck against an object |

|

| Iron workers | Back (1) Forearm/upper arm (1) Eye (1) Knee (1) |

Sprains/strains Sprains/strains Foreign body Sprains/strains |

Overexertion (lifting objects) Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) Struck by an object (flying object) Fall from higher level (into shaft/floor opening) |

|

| Operators | Ankle/foot/toes (2) Back (1) Eye (1) |

Contusion/crushing bruise Sprains/strains Foreign body |

Struck by an object (falling object) Overexertion (using tools/machines) Struck by an object (flying object) |

|

| Engineers Masons |

Back (2) Mouth (1) |

Contusion, sprains/strains Puncture |

Fall on same level, sudden muscular movements Contact with animals/insects |

|

| 35–44 | Laborers | Fingers/hand/wrist (9) Back (3) Lower leg (3) Knee (2) Multiple body parts (2) Mouth (1) Eye (1) |

Contusion/cut/puncture Sprains/strains, contusion Burn, cut/laceration Contusion, sprains/strains Sprains/strains Fracture Foreign body/matter |

Caught in between, struck by or against an object Overexertion (lifting objects), struck by an object Contact with temperature extremes, struck by an object Fall on same level, bodily reaction/motion Overexertion (in lifting objects) Fall on same level (fall to the walkway) Rubbed or abraded |

| Carpenters | Fingers/hand/wrist (2) Neck (2) Forearm/upper arm (1) Back (1) Knee (1) |

Cut/laceration, contusion Sprains/strains, Puncture Sprains/strains Sprains/strains Sprains/strains |

Puncture/scrape, caught in between object Fall from higher level, contact with animal or insects Overexertion (in pulling or pushing objects) Overexertion (in pulling or pushing objects) Overexertion (in pulling or pushing objects) |

|

| Iron workers | Fingers/hand/wrist (2) Foot/toes (2) Elbow (1) Hip (1) Chest (1) |

Cut/laceration, contusion Sprains/strains, contusion Sprains/strains Sprains/strains Sprains/strains |

Struck against/by an object Fall from higher level, bodily reaction/movements Cumulative trauma/repetition Fall from higher level (from scaffolds/walkways) Overexertion (in lifting objects) |

|

| Machine operators | Multiple body parts (2) Shoulder (1) Eye (1) |

Sprains/strains Dislocation Burn |

Fall from higher level, bodily reaction/movements Overexertion (while bending or twisting) Contact with temperature extremes |

|

| Traffic control, Engineers, masons | Fingers/hand/wrist (2) Knee (2) |

Contusion, cut/laceration Sprains/strains |

Caught in between object, rubbed/abraded Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) |

|

| 45–54 | Laborers | Ankle foot/toes (2) Forearm/upper arm (2) Neck (1) Chest/ribs (1) Multiple body parts (1) Eye (1) Head (1) Back (1) |

Contusion, sprains/strains Contusion/crushing bruise Sprains/strains Fracture Multiple injury Foreign body Foreign body Sprains/strains |

Struck by an object, sudden muscular movements Caught in between object, struck against an object Struck again an (stationary) object Fall on same level (fall from liquid/grease spills) Struck by an (moving) object Rubbed/abraded Contact with acid chemical (caustic concrete) Overexertion (lifting objects) |

| Carpenters | Ankle/foot/toes (2) Fingers/hand/wrist (2) Shoulder (1) Lower leg (1) Elbow (1) Shoulder (1) Multiple body parts (1) |

Cut/laceration, puncture Cut/laceration Sprains/strains Puncture Sprains/strains Sprains/strains Contusion/crushing bruise |

Struck against an object, puncture/scrape Cut/puncture/scrape (hand tools/machine in use) Fall on same level (fall to the walkway) Puncture/scrape Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) Fall on same level (fall from liquid/grease spills) Fall from higher level (from scaffolds/walkways) |

|

| Iron workers | Mouth (1) Chest (1) Multiple body parts (1) |

Fracture Sprains/strains Sprains/strains |

Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) Overexertion (in lifting objects) |

|

| Operators | Multiple body parts (3) Chest/ribs (1) Eye (1) Forearm/upper arm (1) Ankle/foot/toes (1) Knee (1) Head (1) |

Sprains/strains, contusion Sprains/strains Foreign body Sprains/strains Contusion/crushing bruise Contusion/crushing bruise Foreign body |

Fall from higher level, overexertion, collision Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movement) Contact with caustic/toxics (acid chemical) Caught in between (moving) objects Fall on same level (fall onto/against objects) Struck against an object (stationary object) Contact with animals or insects |

|

| Engineers, painters | Ankle/foot/toes (2) Eye (1) |

Sprains/strains Foreign body |

Fall on same level, bodily reaction/movements Rubbed/abraded |

|

| Over 55 | Laborers | Multiple body parts (1) Back (1) Lower leg (1) Eye (1) Forearm/upper arm (1) |

Heat stroke/exhaustion Sprains/strains Sprains/strains Foreign body Cut/laceration |

Bodily reaction Struck against an (stationary) object Overexertion (lifting objects) Rubbed/abraded Struck again an (sharp) object |

| Carpenters | Hip (1) | Contusion/bruise | Struck against an object | |

| Operator s | Back (1) | Sprains/strains | Bodily reaction (sudden muscular movements) | |

| Other (surveyors) | Fingers/hand/wrist (1) | Cut/laceration | Fall from higher level (into excavations/opening) |

CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome.

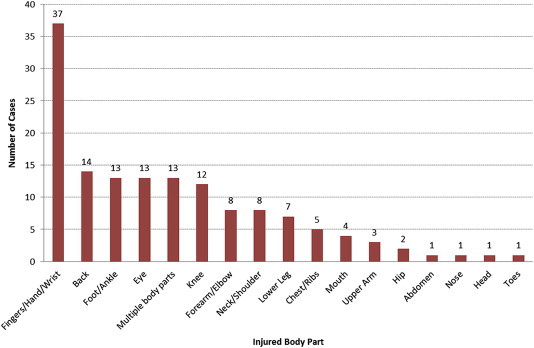

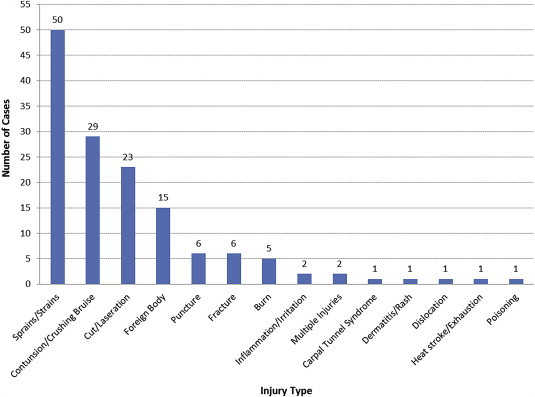

The body part of injury in each trade and age group was also identified. The fingers/hand/wrist were the most frequent body part injured (26%; i.e., 37 of 143 total cases), followed by back (10%), foot/ankle (9%), eye (9%), multiple body parts (9%), and knee (8%; Fig. 2). Sprains/strains were the most common type of injuries that occurred (35%; i.e., 50 of 143 total cases), followed by contusion/crushing bruise (20%), and cut/laceration (16%; Fig. 3). The age groups of under 25 and 25–34 years sustained 20 injuries to their fingers/hand/wrist because of cut/laceration, contusion, and sprains/strains. The age group of 35–44 years had 15 injuries in their fingers/hand/wrist due to contusion, cut/laceration, or puncture caused by being caught between objects, or struck by or against an object. The 45–54 years and > 55 years age groups suffered from sprains/strains and contusion/crushing bruise injuries due to falls from a higher level and overexertion while lifting objects. Of these injuries, the older worker groups had increased injuries to their ankle/foot/toes, knee, lower leg, forearm/upper arm, neck, back, and multiple body parts (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Injured body parts.

Fig. 3.

Injury type.

With older workers becoming more prevalent within the construction industry, there is a growing need for a sustained focus on aging worker health and safety [6]. Businesses that change their perceptions of older workers, including their value and contribution to the workplace, will be in front of the curve to take advantage of the changing demographics. Older workers bring the benefit of desirable construction experience to the workplace. They often have specific knowledge of construction methods—usable tools such as process management and material handling—that can help improve productivity and bring safety to the workplace. Understanding the older worker, changing the work environment to accommodate them, and changing the way we train adults will create a healthier, safer, and more productive workforce for the largest working population in the United States [7]. However, older workers are at a disadvantage when it comes to overall task performance. Older workers have decreased capacity in areas such as vision, hearing, strength, balance, and response time. Although much of the literature does not explicitly state that older workers suffer increased error rates, it does show this factor to be a concern. To accommodate seniors in the workplace, employers must acknowledge that these workers are a valuable resource and establish policies, procedures, and practices conducive to their retention [8]. Education may be an effective tool to accommodate the challenges of the aging construction workforce. Older workers need to understand what types of changes to expect in their bodies. The older worker needs to be aware of the types of ergonomic hazards that are potentially more threatening to their health and safety on the job and at home, and learn new ways to avoid them or work around them. Education for the aging worker that helps them understand their physiological changes could be a proactive approach to avoiding injuries. If the worker knows what to expect in the way of approaching physiological changes a few years further into their career, they may begin to think about the task they are performing today and look for new ways to complete the task in the future that minimizes exposure to ergonomic hazards. Educating the workforce may begin to produce new ways to reduce the hazards they are exposed to now through cooperative efforts between management, engineering, and first-line supervision. The informed older worker can begin to look for new tools, interventions, processes, and approaches to completing the necessary tasks of the construction project. Additionally, training strategies for the aging workforce will need to adapt to the cognitive capabilities of individual workers. Learning and retention abilities will vary between computer-based training and hands-on training; therefore, a test could be utilized in order to rate or grade an individual’s abilities after training. Incident investigation plays an important role with identifying an underlying root cause of the incident. More in-depth information should be collected pertaining to the physical activity taking place, such as lifting a piece of plywood, pounding in a ground pin, stripping of decking, or hanging a drywall on a ceiling. Each trade utilizes different skills and completes different tasks within the organization. A breakdown or list of activities to add to an investigation report should identify any trend that exists with certain activities and ages of the worker. With this added information, management should be able to collect and maintain a more accurate outline of injury analysis as it relates to the aging workforce.

Based on the data collected in this study, the median age of injured workers was 40 years. Injuries sustained by body part in each age group showed that younger workers generally suffered from finger/hand/wrist injuries because of cut/lacerations, contusion, and puncture, whereas older workers had increased sprains/strains injuries to their ankle/foot/toes, knees/lower legs, and multiple body parts due to falls from a higher level, being struck against an object, and overexertion while lifting. It should be mentioned here that older workers make a substantial contribution to construction in terms of skills and experience. Construction is a physically demanding process that has ergonomics and health implications for both young and older workers. Where necessary, older workers should be retrained and redeployed in terms of work activities. Proactive preventative ergonomic interventions should be undertaken to sustain such older workers. For example, lifting hazards can vary from job site to job site; therefore, lifting training programs should be trade site-specific. Prior to attempting to develop a training program, safety, health, and ergonomic professionals should evaluate the job site materials that will be used throughout the construction project. Safety, health, and ergonomic professionals should review and amend work processes to accommodate the growing presence of elderly workers in construction. Older workers can do the work, but the composition of teams needs to realize a balance between youth and experience. More research is needed to identify the underlying root cause of the incident. Along with the root cause of the incident, it would be beneficial for future studies to know the ages of all of the workers enrolled on the job site. Understanding the individual occupational tasks may help present a more accurate depiction of the incident and will also identify trends and intervention methods. More trade-related training may be able to assist the aging workforce, if the training is individualized to the needs of this aging workforce. The effort of improving ergonomics and safety/health of the aging construction worker may also increase the morale and longevity of parties involved within the construction industry.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.The construction chart book: the US construction industry and its workers. 5th ed. CPWR—The Center for Construction Research and Training; Silver Spring (MD): 2013. 15 p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox R.R., Brogmus G.E., Maynard W.S. Aging workers and ergonomics: a fresh perspective. Prof Saf. 2015;60:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Worker health chart book. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (US), DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2004–146, US NIOSH Publications Dissemination, Cincinnati, OH.

- 4.Bureau of Labor Statistics . 2013. Occupational Injuries and Illnesses by Selected Characteristics for State and Local Government News Release (US) [Internet]http://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/osh2_11262013.htm [cited 2015 Jan 7]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2011. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among older workers (US) [Internet]http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6016a3.htm Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. [cited 2015 Jan 5]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi S.D., Rosenthal D., Hauser S. Health and safety issues of older workers surveyed in the construction industry. Ind Syst Eng Rev. 2013;1:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson A. Effective safety training for an aging workforce. American Society of Safety Engineers Professional Development Conference 2005; Session No. 550, American Society of Safety Engineers, Park Ridge (IL).

- 8.Stalnaker K. The graying of the workforce: safety of older workers in the 21st century. Prof Saf. 1998;43:28–31. [Google Scholar]