Abstract

Malnutrition contributes to almost half of all deaths in children under the age of 5 years, particularly those who live in resource-constrained areas. Those who survive frequently suffer from long-term sequelae including growth failure and neurodevelopmental impairment. Malnutrition is part of a vicious cycle of impaired immunity, recurrent infections and worsening malnutrition. Recently, alterations in the gut microbiome have also been strongly implicated in childhood malnutrition. It has been suggested that malnutrition may delay the normal development of the gut microbiota in early childhood or force it towards an altered composition that lacks the required functions for healthy growth and/or increases the risk for intestinal inflammation. This review addresses our current understanding of the beneficial contributions of gut microbiota to human nutrition (and conversely the potential role of changes in that community to malnutrition), the process of acquiring an intestinal microbiome, potential influences of malnutrition on the developing microbiota and the evidence directly linking alterations in the intestinal microbiome to childhood malnutrition. We review recent studies on the association between alterations in the intestinal microbiome and early childhood malnutrition and discuss them in the context of implications for intervention or prevention of the devastation caused by malnutrition.

What is malnutrition?

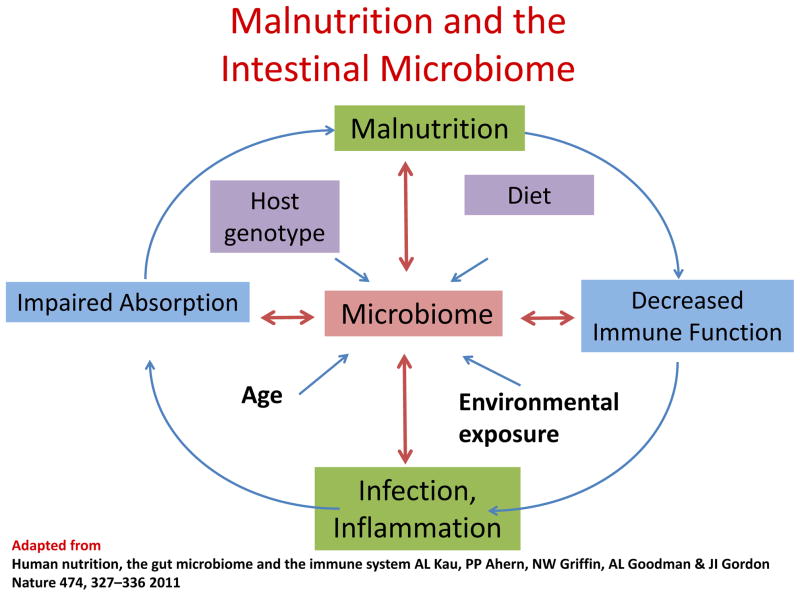

Malnutrition is a significant pediatric health problem worldwide, resulting in nearly half (45%) of all deaths (~3.1 million) in children <5 years (1). Those who survive frequently suffer from long-term sequelae including growth failure and neurodevelopmental impairment (2). Although poverty, with its associated food insecurity, is a major risk factor for malnutrition, the etiology of this condition is far more complex than a simple lack of food. Persistent childhood malnutrition is considered part of a vicious cycle of recurrent infections, impaired immunity and worsening malnutrition, compounded by food insecurity and, likely, host genetic factors as well (3). Recently, alterations in the intestinal microbiome (which may either impact or be impacted by immune responses, infection and nutritional status) have been recognized as part of this cycle (reviewed in (3, 4)) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The impact of the gut microbiome on the vicious cycle of malnutrition, decreased immune function, enteric infection and impaired absorption and mucosal barrier function.

Adapted from Kau et al (3).

Adapted from

Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system AL Kau, PP Ahern, NW Griffin, AL Goodman & JI Gordon Nature 474, 327–336 2011

In children, nutritional status is measured by z scores, which incorporate anthropometric measurements of height/length and/or weight, according to the World Health Organization Child Growth Standards http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/. Childhood malnutrition is categorized as either acute or chronic. Acute malnutrition, also termed wasting, is defined by low weight-for-height z (WHZ) scores, and is divided into moderate (MAM), with WHZ scores between 2 and 3 standard deviations (SD) below the median (>−2 to 3SD), and severe (SAM), with WHZ scores >− 3 SD. SAM can manifest as either marasmus, kwashiorkor or marasmic kwashiorkor(5). Marasmus is characterized by severe wasting, with loss of both fat and muscle. Kwashiorkor is characterized by generalized edema, steatorrhea and other changes; marasmic kwashiorkor is the most extreme condition(5). Stunting is a result of chronic malnutrition and is defined by low height-for-age z (HAZ) scores >−2 SD. This condition is widespread, affecting 165 million children under five years of age globally (1). Curiously, there is a marked variation country to country in the relative rates of stunting and wasting. India and Guatemala both have high rates of stunting in children, yet while prevalence of wasting in India is 30%, it is rare in Guatemala (6). Understanding the etiology of this difference in the manifestation of malnutrition would inform intervention strategies.

Contributions of the intestinal microbiota to host nutrition

A healthy intestinal microbiota is essential to human health, performing a wide range of protective, structural and metabolic functions (7, 8) and affecting host nutrition both directly and indirectly. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) produced by bacterial fermentation of complex dietary polysaccharides are the primary nutrient source for the colonic epithelium. Gut bacteria also produce vitamins (B3, B5, B6, B12, biotin, tetrahydrofolate and Vitamin K) and promote the absorption of minerals (reviewed in (3)). The microbiota contribute to intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and maturation, the induction of host genes for nutrient uptake and the development of the mucosal immune system, all of which are critical to optimal nutrient absorption. The microbiota also participate in extensive molecular cross-talk with the host, generating and responding to a broad range of neurotransmitters and endocrine molecules, which influence systemic lipid and glucose metabolic rates, appetite and intestinal transit time (9).

“Dysbiosis,” or an altered microbiota composition, has been linked to a number of disease states and was recently quantified by a “Microbial Dysbiosis Index” (10). A decrease in abundance or absence of the species that efficiently process foods or produce vitamins could lead to malnutrition even in the face of adequate food intake. Certain hydrogen–scavenging bacteria produce hydrogen sulfide, which can be toxic to the epithelium (11). Microbiota lacking the organisms linked to decreased mucosal inflammation or induction of antimicrobial peptides (12, 13) could result in reduced nutrient absorption secondary to chronic inflammation. In turn, inflammation can promote the growth of Enterobacteriaceae (14). The presence of pathogenic bacteria can cause epithelial damage and/or diarrhea, with a deleterious effect on absorption.

A causal link between malnutrition, microbiota changes and diarrhea

Conversely, malnutrition has been shown to result in dysbiosis (15). Through an elegant series of experiments in a mouse model, the authors of this study demonstrated that tryptophan deficiency from a protein-free diet can lead to vitamin B3 deficiency, which in turn results in decreased production of ileal epithelial antimicrobial peptides. Loss of this activity effects changes in the colonic microbiota which, in the context of mild epithelial damage in that organ, results in a destructive inflammatory response and diarrhea. Fecal transplant to germ-free mice of the microbiota resulting from the protein-free diet confirmed that the exaggerated epithelial colitis was due to this altered community. The model suggested by these experiments is that protein malnutrition can result in changes in the colonic microbiota that are not manifest until the epithelium incurs some form of damage. In the developing world where protein deficiency is common, that inciting damage could be from any number of causes, including viral, bacterial or parasitic infection or environmental toxins. Studies of the pro- and anti-inflammatory balance of members in the diarrhea-susceptible microbiota may shed insight into how a protective community might be constituted.

Assembly of the microbiota

One of the most important tasks of postnatal development is the acquisition from the environment of an intestinal microbiota capable of performing beneficial functions, while at the same time developing a mucosal immune system capable of tolerating desirable community members and also discouraging pathogens. Initially, this colonization was thought to begin in the birth process, but a recent study which describes the identification of bacterial DNA in the placenta of healthy full-term babies (Kjersti Aagaard et al. 2014), as well as studies identifying bacteria in the amniotic fluid and meconium of pre-term babies (DeGuilio 2008, 2010, Ardisonne 2014) raise the possibility of prenatal exposure. However, the question of whether these bacteria are alive remains open. A pattern of succession (16–18) has been described for the acquisition of the neonatal intestinal microbiota, which occurs primarily over the first 2–3 years of life. Very early colonization by Enterobacteria and Streptococcus generates a low redox environment that allows anaerobic bacterial species to flourish. The breast-fed infant gut microbiome is dominated by Bifidobacterium species, which have enzymes suited to extracting energy from milk oligosaccharides. The production of SCFA by the Bifidobacteria lowers the pH in the colon, favoring colonization by anaerobes. The addition of solid food to the infant diet is accompanied by the appearance of a more diverse community of bacteria, capable of digesting starch, fiber, complex plant polysaccharides, sulfated glycoproteins and mucins. A complex diet encourages the establishment of a mature microbiota capable of performing a diverse set of metabolic tasks.

The importance of diet in shaping the developing gut microbiota was demonstrated by a study comparing healthy children, from age 1–6, in Burkina Fasso (BF) and Italy (19). The BF diet is low-fat, low in animal protein and high in starch, fiber and plant polysaccharides; the Italian diet is high in fat, animal protein, starch and simple sugars but low in fiber. The microbiota of children being breast-fed resembled each other more than older children from either country, but the microbiota of the older children were clearly differentiated by country of origin. The genera found exclusively in the BF children (Xylanibacter, Prevotella, Butyrivibrio and Treponema) have genomes rich in enzymes for fermenting the indigestible plant polysaccharides xylan, xylose and carboxymethylcellulose; thus, the BF children seem to have acquired a gut microbiota equipped to process the available nutrients.

Exploring geographic variations in the composition of a healthy microbiota

Given the critical role of the microbiota in nutrition, interventions designed to establish and maintain a healthy gut community might well be a beneficial addition to the standard dietary treatment of malnutrition. However, different cultures with different diets and different environmental exposures may have different microbial communities, which could require different types of encouragement. This would require a broader understanding of what constitutes a healthy microbiota in regions around the world. Likewise, the age of the child and the state of the existing microbiota might also have major effects on the efficacy of this approach.

The most comprehensive study to date of gut bacterial communities in multiple geographic locations (20) examined 531 participants ranging in age from infants to adults and compared Amerindians from Venezuela, rural Malawians and urban Americans. The phylogenetic composition of all fecal samples was determined by sequencing 16S rRNA gene amplicons; a subset of 110 samples was subjected to shotgun sequencing to characterize genomic functional capability. The variety of bioinformatic tools used to analyze the enormous dataset generated in this study (Unifrac, unsupervised clustering with principal co-ordinates analysis, Spearman rank correlation analysis, Random Forests and ShotgunFunctionalizerR) serves as a primer on the use of complementary approaches.

Significant differences in microbiota were found between the three countries, with the US population being most distinct. At the same time, in all countries, children had more interpersonal variation in composition than adults and the phylogenetic composition coalesced towards an adult-like configuration over the first three years from birth. The early loss of Enterobacteriaceae, the gain in infants of oligosaccharide-degrading anaerobes and acetogenic and methanogenic bacteria (16) and the decline in relative abundance of Bifidobacterium longum with age (21) appeared to be universal. In the analysis of metabolic capability, several findings related to nutrition were described. While the adults had microbial genes for metabolizing dietary folate, the gut microbes of babies were enriched in genes for de novo folate synthesis, reflecting the dependence of children on bacterial vitamin production prior to dietary intake of plant material. Microbial genes for B12 biosynthesis increased with age; because certain bacteria are the primary source of B12, the acquisition of those species in childhood is essential to avoid B12 deficiency.

In terms of differences between geographic locations, in the non-US cohorts, microbial vitamin B2 biosynthetic pathways, the enzymes involved in metabolizing host-derived glycans and urease genes were enriched, perhaps reflecting a bacterial selection pressure in response to dietary deficiency of B2 and carbohydrates in these populations. Ammonia released by urease can be used for microbial synthesis of amino acids and plays an important role in nitrogen recycling, an important function under conditions of low dietary protein. While the authors acknowledged dietary differences between the US and non-US populations, a more rigorous characterization of the nutritional value of the diets in the three populations would have added further discriminatory classes to their analyses. Correlation of the microbiota of children with suboptimal nutrition with enhanced bacterial metabolic function in the areas of deficiency would have confirmed the importance of the microbiota in maintaining nutritional balance. Likewise, the microbiota differences attributed to geographic location may have reflected the effects of undocumented malnutrition in those populations instead.

Understanding the microbiota in the malnourished child

To date only a handful of studies have characterized the microbiota of healthy children, even fewer have addressed the malnourished child (Table). Monira et al (22) found marked differences in phylogenetic composition of the microbiota from seven healthy and seven acutely malnourished (but otherwise healthy) children in Bangladesh, aged 2–3 years. Healthy children came from families of moderate-high socioeconomic status; malnourished children were from poor families. The diet of malnourished children consisted exclusively of rice, fruit and vegetables, while the diet of healthy children included several sources of protein. Among other differences, Proteobacteria were 9.2 times higher in the malnourished children, representing a relative abundance of 32% of all species detected. The alpha diversity (complexity within a sample) of the microbiota was significantly lower in the malnourished children.

Table 1.

Studies of the gut microbiome in malnourished children

| Location of study | Age of subjects | Number and nutritional status of subjects | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| India (Slum in Kolkota) | 16 months | 2: one “malnourished” one “healthy” |

No z scores provided Both from same slum Malnourished child had higher relative abundance of Campylobacter |

Gupta et al 2011 |

| Bangladesh | 24–36 months | 14: 7 with z scores <70% of WHO median 7 at 100% |

Single sample per subject Malnourished children were from slum Healthy children were of moderate to high economic status with better diet |

Monira et al 2011 |

| Malawi | 7–24 months | 44: 9 well-nourished twin pairs 13 twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor (SAM) |

Metagenomic analysis on fecal samples pre-diagnosis of kwashiorkor, at time of diagnosis, while on RUTF and after resumption of Malawi diet | Smith et al 2013 |

| India (Kolkota) | 5–60 months | 20: 6 “apparently healthy” 8 “borderline malnourished” 6 “severely malnourished” |

Metagenomic analysis on fecal samples Identified “core” set of 23 genera whose abundance could distinguish between the three nutritional status groups |

Ghosh et al 2014 |

| Bangladesh (Slum in Mirpur) | Healthy 0–24 months SAM 0–20 months |

114: 50 healthy children monthly from 1–24 months 64 children with SAM |

Metagenomic analysis on fecal samples of healthy children and hospitalized children with SAM before during and after RUTF | Subramaniam et al 2014 |

| India (Slum in Vellore) | every 3 months from 3–24 months | 20: 10 low birth weight, persistent stunting 10 normal birth weight, no stunting |

Subjects all from same slum z scores and microbiota monitored over study period |

Dinh et al unpublished |

Species-rich intestinal communities are more resistant to invasion by pathogens because the efficient use of limiting resources by distinct species specializing in each resource results in competitive exclusion. At the same time, overlapping capabilities provided by a diverse community ensures that essential functions can continue in the face of a degree of flux in membership. These concepts are explicated in a review by Lozupone et al (23); of particular relevance to the microbiota in childhood malnutrition is their discussion of the transitions between the species-poor but healthy infant state, healthy stable mature states and stable low diversity degraded states. The latter can be induced by acute disturbances from which there is incomplete recovery or alternatively by the incremental erosion of persistent stressors. For example, studies of the effect of antibiotic treatment (24) have demonstrated persistent suboptimal microbial community structure following antibiotic administration. A child suffering from chronic nutritional deficits or repeated enteric infections could be at risk of developing a stable degraded microbiota as a result of persistent stressors. The two non-US populations in the study by Yatsunenko et al (20) had microbiomes with lower diversity than US subjects, indicating an increased susceptibility of those populations to compositional change.

A direct link between the microbiota and malnutrition

One of the difficulties in comparative studies of the microbiota is the number of variables potentially influencing community composition. The use of twin studies is an effective way to reduce confounders. Smith et al (25) analyzed the stool microbiota of twin pairs in Malawi (which has exceedingly high rates of infant mortality from malnutrition (http://www.unicef.org/malawi/children.html)) over the first three years of their lives, identifying twin pairs who became discordant for kwashiorkor. Since twins at this age share not only genetics but also diet and exposure to environmental microbial reservoirs, the healthy co-twin was an excellent control. Of the 315 twin pairs enrolled, 9 well-nourished twin pairs and 13 pairs discordant for kwashiorkor were selected for in-depth functional metagenomic analysis of their fecal microbiomes. While the microbiomes of the healthy twins followed a developmental trajectory of progression towards older children’s microbiota, those of the kwashiorkor twins failed to mature, despite the fact that they were receiving ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), the standard treatment for severe malnutrition.

Fecal transplants into gnotobiotic mice showed that the malnutrition phenotype could be transferred with the microbiota from the kwashiorkor twin. Dramatic differences were seen in weight loss between recipients of the healthy vs. the kwashiorkor twin’s feces. These differences were seen only when the mice were fed a diet based on Malawian staple foods, which are protein deficient; when the mice were switched to RUTF both groups gained weight. Resumption of the Malawian diet resulted in return to a persistent weight loss, although at a rate less profound than initially in the kwashiorkor group. Phylogenetic analysis of the microbiota of mice receiving the kwashiorkor twin fecal transplant revealed a deficiency of anti-inflammatory taxa; also, among the species whose relative abundance was significantly higher in these mice was Bilophila wadworthia, a sulfite-reducing inflammogenic bacterium. The dramatically increased abundance of Lactobacilli and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the kwashiorkor twin transplant recipients following RUTF treatment was sustained after the resumption of the Malawian diet. These bacteria have been associated with anti-inflammatory effects, which may explain their somewhat improved ability ice to sustain weight when shifted back to the protein deficient diet.

Metabolic studies on both groups of mice indicated that while they showed increases in fecal metabolites representing carbohydrate, amino acid and fatty acid metabolism during RUTF feedings, the mice with healthy microbiota sustained this higher level after return to the Malawian diet, while the diet effect was transient in the kwashiorkor microbiota recipients. Other metabolite differences between the two groups suggested that on the low-protein diet, the kwashiorkor microbiome results in abnormal sulfur metabolism and in inhibition of one or more TCA cycle enzymes. These results clearly demonstrate a causative link between the microbiota and malnutrition. An additional conclusion is that to result in a meaningful outcome therapeutic interventions must effect a lasting change in the microbiota to a more anti-inflammatory, higher efficiency nutrient extraction community.

A novel tool for quantifying microbiota defects

Building on their observation of an apparent maturation failure of the microbiota of the Malawian twins with kwashiorkor, Subramanian et al. developed a novel analytic approach to quantify microbiota immaturity (26). In a recent study performed in Bangladesh, they determined the phylogenetic composition of fecal samples collected monthly, from birth up to 24 months, from a cohort of children with consistently healthy growth. By using a machine-learning approach to regress the relative abundances of the identified bacteria against the age of the child at the time of sample collection, they identified a set of the 24 most “age-discriminatory” (most significantly age-correlated) taxa, which became the basis for a model, which defines “microbiota age”. This parameter was used to derive two novel metrics, “relative microbiota maturity” (the difference between the microbiota age of a child and the microbiota age of healthy children of the same chronological age) and a “microbiota-for-age Z score” (MAZ). The model was verified by applying it to a second cohort of Bangladeshi children and then to a previous study of healthy children in Malawi, suggesting that it may have a universal utility.

To measure the effect of SAM on microbiota maturity, the model was used in the evaluation of a cohort of hospitalized malnourished children enrolled in a study to investigate fecal microbiota before, during and after nutritional rehabilitation with two different formulations of RUTF. WHZ scores in children with SAM improved significantly during treatment with either therapeutic, but consistently lagged behind healthy children through the 4 month follow-up. These children were found to have significant microbiota immaturity at the time of initiation of treatment, which transiently improved but regressed to significant immaturity during follow-up. When the microbiota from children with MAM were examined, the relationship between relative microbiota maturity, MAZ and WHZ was again shown to be significant. Resolution of the nutritional deficits in these children would thus seem to require restoration of an age-appropriate microbiota.

While these studies were primarily focused on acute malnutrition, chronic malnutrition or stunting is much more prevalent worldwide (1). Frequent infections are recognized as an important risk factor for stunting; in developing countries, children under 2 experience 3–5 episodes of diarrhea per year (27). In the healthy Bangladeshi cohort, the microbiota maturity indices were shown to be significantly lower both during and one month after an episode of diarrhea. Further studies to examine the effect of multiple diarrhea episodes might determine whether the transient microbiota immaturity would become persistent and whether such a maturity deficit precedes the onset of measurable growth defects.

The maturity indices could also be used to gain a clearer understanding of the nature of the intestinal dysbioses in the various manifestations of malnutrition. Prentice et al (5) characterized marasmus and kwashiorkor as “adaptive” and “maladaptive” metabolic responses to starvation, respectively. In marasmus, insufficient nutrition is compensated for by expending fat and muscle as energy sources, with protection of serum proteins. Stunting might also be viewed as an adaptive response in which, under conditions of starvation, height gain is sacrificed in order to sustain weight and energy. In kwashiorkor, the systemic metabolic response is clearly pathologic, with aberrant storage of fat in the liver, loss of potential energy resources through steatorrhea, and edema resulting from loss of serum proteins. Comparisons of the microbiota maturity and phylogenetic composition in these three conditions could inform whether distinct therapeutic approaches are needed.

The gut microbiota in chronic malnutrition

Despite the fact that chronic malnutrition or stunting is more widely prevalent than acute malnutrition globally, most published studies on the role of the microbiome in malnutrition have focused on the latter. India has one of the highest rates of stunting in the world with 48% (61 million) children under the age of five being stunted (http://www.unicef.org/india/nutrition.html.) Ghosh et al reported alterations in the micobiomes of malnourished children in India, some of whom were stunted (28). One of the major risk factors for stunting in India is low birth weight (29). We recently conducted a longitudinal study in South India of the gut microbiota of 10 children with low birth weight and persistent stunting and 10 children with normal birth weight and no evidence of stunting. Fecal samples were analyzed at 3-monthly intervals from 3 to 24 months of age. Analysis of differentially abundant taxa using the LEfSe (Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size) algorithm (30) revealed that overall the microbiota of stunted children were enriched in inflammogenic bacteria belonging to the Proteobacteria phylum, whereas those of children who were not stunted were enriched in probiotic species such as Bifidobacteria longum (Dinh et al, unpublished).

In low and middle income countries most of the stunting occurs in the first two years of life. However, very few studies have been done in children in this age group. More research that focuses on this period of life when the microbiota is maturing are needed. A recent study in mice demonstrated that early (pre-weaning) perturbation of microbiota composition with low-dose penicillin could result in future predisposition for weight gain which manifests well after the changes appeared to have been resolved. This work confirms the importance of investigating how differences in colonization patterns at this critical time might lead to long-term differences in metabolic capabilities. In addition, since maternal malnutrition contributes to fetal growth restriction and low birth weight leading to an increased risk of stunting in early life, possible associations between the maternal microbiome during pregnancy and the perinatal period and stunting in the infant need to be considered.

Microbiota-based therapeutic interventions

Three approaches to microbiota manipulation are currently available: probiotics (and the related pre- and synbiotics), (32) antibiotics and fecal transplantation. Although fecal transplantation has been highly effective in treatment of C. difficile infection (33), this approach has not yet been applied to the treatment of malnutrition in humans. Prebiotics are indigestible food supplements that provide nutrition to desirable gut commensals, encouraging their growth. Probiotics are live organisms known to have beneficial properties, which may or may not colonize the gut after ingestion. Synbiotics are the simultaneous administration of both.

The only published trial of synbiotics in malnutrition is the PRONUT study (34), a randomized control trial of synbiotic supplementation of the standard RUTF treatment performed in Malawi, in a cohort of 795 children aged 5–168 months of whom 40% were seropositive for HIV. The synbiotic (four Lactobacillus strains and four prebiotic fermentable bioactive fibers) appeared to have no effect on outcomes. However, conclusions about both safety and efficacy based on this trial are tempered by the fact that on admission, all children received a 7-day course of co-trimoxazole, with 50% also receiving additional parenteral antibiotics. Two of the four probiotic organisms were demonstrated to be sensitive to co-trimoxazole. The wide age span of the children, presenting at potentially different microbiota ages, is also confounding.

Since recurrent diarrhea and/or infection are closely associated with malnutrition, antibiotic use has been used in the treatment of SAM. A recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial looked at the addition of a 7-day course of amoxicillin, cefdinir or placebo to RUTF therapy for 2767 Malawian children aged 6–59 months with SAM (35). Children were recruited from feeding clinics and exhibited all three forms of SAM; ~70% met the criteria for kwashiorkor, ~9% had marasmic kwashiorkor and ~21% had marasmus. In addition, >80% were stunted. Although the study group was characterized as “uncomplicated” SAM, over 80% had exhibited an infectious symptom (fever, cough, and/or diarrhea) in the previous 2 weeks. Of the 30% for whom HIV testing had been performed, 20% were seropositive. The above characteristics were fairly evenly distributed among treatment groups. Recovery rates were higher and mortality rates were lower in the antibiotic-treated groups, prompting the authors to conclude that antibiotic use in SAM is warranted. While the short-term benefits of this approach may have been demonstrated, considerable controversy exists regarding its long-term consequences. No microbiota analysis was included in the study, so there is no way to evaluate what the effects the antibiotic had, if any, with regard to correcting dysbiosis. Follow-up in this cohort was only 12 weeks, so there is no indication of whether the antibiotic benefits included reduction in relapses. More importantly, the potential for promoting antibiotic resistance by its widespread use is a serious concern.

Future research priorities

Our current understanding of the intestinal microbiome is based on the characterization of its composition either by phylogenetic makeup (16S rRNA sequencing) or functional capability (shotgun sequencing and identification of genes involved in metabolic pathways.) Neither of these can adequately capture the tenor of the molecular crosstalk occurring between host and bacteria (triggered by metabolites, antigens, signaling molecules, immune modulators and hormones) that results in systemic effects on both metabolism and the immune system. The addition of transcriptomics and metabolomics to studies of the microbiome in malnutrition would result in a broader picture of how imbalances may develop. In terms of development of interventions, additional studies need to be done on exploring the practical aspects of therapeutic manipulation of the microbiome (How lasting an effect can we have on an already established community?), development of targeted antimicrobials that will spare the beneficial microbiome, development of age-appropriate (as identified by the microbial maturity study) probiotics based on deficits in microbiota profiles or taxa having metabolic or anti-inflammatory capabilities that have been identified as beneficial, and development of culture-centric nutritional supplements based on locally available food products which will be optimal for the microbiota already acquired.

Since most of the gut microbiota are unculturable, the role of these organisms and the potential for exploiting them for development of interventions remains to be determined. Although metagenomic approaches to understanding their contribution to beneficial or detrimental metabolic functions have contributed to knowledge of their possible roles, new technologies for cultivating them or finding ways to substitute them with culturable bacteria with similar metabolic function are needed.

Most epidemiologic studies reported in the current literature on malnutrition and the gut microbiota are based on associations or correlations that preclude a determination of the temporal sequence of these relationships, raising the classic chicken and egg question: which comes first-dysbiosis or malnutrition? To some extent these issues can be addressed by longitudinal birth cohort studies in children or animal studies. However, new and innovative approaches to resolving these issues are needed.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors laboratory is supported by the US National Institutes of Health grants 5R01 AI072222, R21 AI094678 and R21 AI102813 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Duy Dinh was supported by NIH T32AI007439.

References

- 1.Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R, Uauy R Maternal Child Nutrition Study G. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2013;382:427–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, Haider BA, Kirkwood B, Morris SS, Sachdev HP, Shekar M Maternal, Child Undernutrition Study G. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371:417–440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 2011;474:327–336. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon JI, Dewey KG, Mills DA, Medzhitov RM. The human gut microbiota and undernutrition. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:137ps112. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prentice AM, Nabwera H, Kwambana B, Antonio M, Moore SE. Microbes and the malnourished child. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:180fs111. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martorell R, Young MF. Patterns of stunting and wasting: potential explanatory factors. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:227–233. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307:1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Hara AM, Shanahan F. The gut flora as a forgotten organ. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:688–693. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans JM, Morris LS, Marchesi JR. The gut microbiome: the role of a virtual organ in the endocrinology of the host. J Endocrinol. 2013;218:R37–47. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vazquez-Baeza Y, Van Treuren W, Ren B, Schwager E, Knights D, Song SJ, Yassour M, Morgan XC, Kostic AD, Luo C, Gonzalez A, McDonald D, Haberman Y, Walters T, Baker S, Rosh J, Stephens M, Heyman M, Markowitz J, Baldassano R, Griffiths A, Sylvester F, Mack D, Kim S, Crandall W, Hyams J, Huttenhower C, Knight R, Xavier RJ. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Sulphate reducing bacteria and hydrogen metabolism in the human large intestine. Gut. 1993;34:437–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan R, Koebnick C, Schildt J, Schmidt S, Mueller M, Possner M, Radke M, Blaut M. Effects of Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 supplementation on intestinal microbiota of preterm infants: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:4025–4031. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00767-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, Finlay BB. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:204. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto T, Perlot T, Rehman A, Trichereau J, Ishiguro H, Paolino M, Sigl V, Hanada T, Hanada R, Lipinski S, Wild B, Camargo SM, Singer D, Richter A, Kuba K, Fukamizu A, Schreiber S, Clevers H, Verrey F, Rosenstiel P, Penninger JM. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackie RI, Sghir A, Gaskins HR. Developmental microbial ecology of the neonatal gastrointestinal tract. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:1035S–1045S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.5.1035s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Favier CF, Vaughan EE, De Vos WM, Akkermans AD. Molecular monitoring of succession of bacterial communities in human neonates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:219–226. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.1.219-226.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koenig JE, Spor A, Scalfone N, Fricker AD, Stombaugh J, Knight R, Angenent LT, Ley RE. Succession of microbial consortia in the developing infant gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4578–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Filippo C, Cavalieri D, Di Paola M, Ramazzotti M, Poullet JB, Massart S, Collini S, Pieraccini G, Lionetti P. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14691–14696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005963107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balamurugan R, Janardhan HP, George S, Chittaranjan SP, Ramakrishna BS. Bacterial succession in the colon during childhood and adolescence: molecular studies in a southern Indian village. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1643–1647. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monira S, Nakamura S, Gotoh K, Izutsu K, Watanabe H, Alam NH, Endtz HP, Cravioto A, Ali SI, Nakaya T, Horii T, Iida T, Alam M. Gut microbiota of healthy and malnourished children in bangladesh. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:228. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, Jansson JK, Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Mkakosya R, Cheng J, Kau AL, Rich SS, Concannon P, Mychaleckyj JC, Liu J, Houpt E, Li JV, Holmes E, Nicholson J, Knights D, Ursell LK, Knight R, Gordon JI. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339:548–554. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, Benezra A, DeStefano J, Meier MF, Muegge BD, Barratt MJ, VanArendonk LG, Zhang Q, Province MA, Petri WA, Jr, Ahmed T, Gordon JI. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;509:417–421. doi: 10.1038/nature13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh TS, Sen Gupta S, Bhattacharya T, Yadav D, Barik A, Chowdhury A, Das B, Mande SS, Nair GB. Gut microbiomes of Indian children of varying nutritional status. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehman AM, Gladstone BP, Verghese VP, Muliyil J, Jaffar S, Kang G. Chronic growth faltering amongst a birth cohort of Indian children begins prior to weaning and is highly prevalent at three years of age. Nutr J. 2009;8:44. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, Gevers D, Miropolsky L, Garrett WS, Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta SS, Mohammed MH, Ghosh TS, Kanungo S, Nair GB, Mande SS. Metagenome of the gut of a malnourished child. Gut Pathog. 2011;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Vrese M, Schrezenmeir J. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2008;111:1–66. doi: 10.1007/10_2008_097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin M, Mellow M, Tierney WM. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in the Treatment of Clostridium difficile Infections. Am J Med. 2014;127:479–483. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerac M, Bunn J, Seal A, Thindwa M, Tomkins A, Sadler K, Bahwere P, Collins S. Probiotics and prebiotics for severe acute malnutrition (PRONUT study): a double-blind efficacy randomised controlled trial in Malawi. Lancet. 2009;374:136–144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trehan I, Goldbach HS, LaGrone LN, Meuli GJ, Wang RJ, Maleta KM, Manary MJ. Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:425–435. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]