Abstract

The molecular bases of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are not fully understood. Trimethylated histone 4 lysine 3 (H3K4me3) is present in promoters of actively transcribed genes and has been shown to be involved in hematopoietic differentiation. We performed a genome-wide H3K4me3 CHIP-Seq analysis of primary MDS bone marrow (BM) CD34+ cells. This resulted in the identification of 36 genes marked by distinct higher levels of promoter H3K4me3 in MDS. A majority of these genes are involved in NF-kB activation and innate immunity signaling. We then analyzed expression of histone demethylases and observed significant overexpression of the JmjC-domain histone demethylase JMJD3 (KDM6b) in MDS CD34+ cells. Furthermore, we demonstrated that JMJD3 has a positive effect on transcription of multiple CHIP-Seq identified genes involved in NF-kB activation. Inhibition of JMJD3 using shRNA in primary BM MDS CD34+ cells resulted in an increased number of erythroid colonies in samples isolated from patients with lower-risk MDS. Taken together, these data indicate the deregulation of H3K4me3 and associated abnormal activation of innate immunity signals play a role in the pathogenesis of MDS and that targeting these signals may have potential therapeutic value in MDS.

Keywords: myelodysplastic syndromes, H3K4me3, CHIP-Seq, JMJD3, innate immunity

Introduction

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a complex group of myeloid disorders characterized by peripheral blood cytopenias and an increased risk of transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). (1) Although we have witnessed significant improvements in our ability to diagnose and treat patients with MDS, (2) the prognosis of a large majority of patients with MDS is still poor. (3) Molecular research in MDS is complicated by absence of cell lines, few available animal models, (4) and the heterogeneous nature of the disease.(5) The pathogenesis of MDS is the consequence of both genetic and epigenetic lesions, including alterations of DNA methylation and histone modifications. (6) For instance, a large proportion of genetic mutations identified so far in MDS occur in DNA methylation regulators such as TET2, IDH1/2, and DNMT3A, as well as histone modifiers such as EZH2 and ASXL1. (7, 8) Histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) is one of the best characterized histone marks and is known to be associated with an active gene transcription state. (9) H3K4 methylation has been shown to be crucial for lineage determination of hematopoietic stem/ early progenitor cells (HSPCs).(10) JMJD3 is a JmjC domain protein involved in the control of histone methylation and gene expression regulation. (11) Since MDS is the result of severely compromised hematopoiesis, (1) we hypothesized that H3K4me3 genomic distribution could be abnormal in the HSPCs of MDS, and that its mapping will allow us to gain insight into the pathophysiology of the disease. To study this, we performed CHIP-Seq (chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with whole genome sequencing) to compare genome-wide H3K4me3 distribution at gene promoter regions between MDS and normal genomes. Three major findings are reported here. First, we identified 36 genes differentially marked by higher H3K4me3 levels at their promoters in MDS BM CD34+ cells. Second, a majority of these gene products are involved in innate immunity regulation and NF-KB activation, suggesting a role for the deregulation of innate immunity signaling in MDS. Third, we identified that JMJD3 is involved in the transcription regulation of the genes identified by CHIP-Seq. Inhibition of JMJD3 in cultured primary MDS CD34+ cells isolated from patients with lower-risk MDS resulted in an increased formation of erythroid colonies. These data suggest that MDS CD34+ cells are characterized by deregulation of innate immunity signals and that this information could have prognostic and therapeutic value.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

293T cells were cultured in DMEM, 10% fetal calf serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. OCI-AML3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640, 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. All cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA).

Isolation and culture of bone marrow CD34+ cells

Human samples were obtained following institutional guidelines. MDS bone marrow specimens were obtained freshly from patients referred to the Department of Leukemia at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC). Diagnosis was confirmed by a dedicated hematopathologist (CB-R) as soon as the sample was obtained. Bone marrows from healthy individuals were obtained from AllCells (Emeryville, CA). Isolation of CD34+ cells was performed using MicroBead Kit (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) following manufacturer's instructions. For colony forming assays, MDS bone marrow CD34+ cells were seeded at 104 cells/ml respectively in 3.5 cm round culture dishes with methocult GF H4434 (Stem Cell Technology, Vancouver, Canada). Colonies were evaluated after two weeks of culture.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

OCI-AML3 and fresh human bone marrow CD34+ cells were cross linked before adding 0.125 M glycine and were processed following published CHIP protocol. (9) Detailed protocol is described in supplemental materials and methods.

CHIP-PCR

Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (Q-PCR) using the Quanti-Tect SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia,CA). The amount of DNA fragment co-precipitated with antibody was calculated and compared to the amount of the same genomic fragment in total input DNA, resulting in percent input. A list of primers is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Illumina sequencing of CHIP DNA and data analysis

Concentration of CHIP DNA was calculated using Picogreen DNA quantization kit following manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). CHIP DNA libraries were prepared and then sequenced following manufacturer protocols (Illumina San Diego, CA). Sequence reads (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/collaborations/ruichen/MDS/) were mapped to the human reference genome (hg18) using BWA.(12) To maximize the sensitivity of enriched region detection, data obtained from MDS patient and normal controls were pooled as patient and control respectively. Enriched regions in MDS patients and normal controls were identified using MACS with default parameters by comparing the pooled ChIP-Seq data to its matching input control.(13) To ensure specificity, a p-value of 10-6 was used as cutoff to identify enriched regions across the genome. In house perl scripts were developed to identify putative promoter peaks that were differently enriched in MDS samples versus normal controls.

Capture deep sequencing of genomic DNA

Illumina paired-end libraries were generated according to the manufacturer's protocol (Illumina San Diego, CA). 3 μg of pre-capture library DNA was used for each capture reaction. NimbleGen SeqCap EZ Hybridization and Wash Kits (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) were used following the manufacturer's protocol. 14-17 cycles of PCR amplification were applied to the samples after hybridization, based on yield. After that, captured libraries were quantified by picogreen and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 as 100-bp paired-end reads, following the manufacturer's protocols. Sequencing data was stored as fastq format which contained reads and quality information. Fastq files were then mapped and aligned to human reference hg18 using BWA (12). To refine the alignment and adjust the quality score provided by sequencer, GATK was used to realign reads and recalibrate the quality score (14). SNPs were called using AtlasSNP2 (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/cascade-tech-software_atlas_snp-ti.hgsc). The posterior probability was set as 0.9 and the minimum number of variants reads as 3. To identify rare SNPs, candidate SNPs were filtered against dbSNP130, 1000 genome database, and the Human Genome Sequencing Center (Baylor College of Medicine) internal database. Indels were called using AtlasIndel (http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/cascade-tech-software_atlas2_snp_indel_calling_pipeline-ti.hgsc).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's protocol. 200 nanograms of total RNA were used for reverse transcription (RT) reactions using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer's protocol. For real-time PCR, primers and probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems and analyzed using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System. PCR reactions were performed using 20 × Assays-On-Demand Gene Expression Assay Mix and TaqMan Universal PCR Master mix according to the manufacturer's protocol. GAPDH was used as internal control.

siRNA transfection

Control siRNA and siRNAs targeting C5AR1, PTAFR, FPR2 and TYROBP genes were purchased from ABI Silencer® Select Pre-Designed & Validated siRNA collection (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Transfection of OCI-AML3 cells was performed using Lonza nucleofector T kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) with the siRNA pool containing 1μmol of each siRNA or 4 μmol control siRNA. Cells were collected 24-48 hr after transfection.

Recombinant retrovirus mediated shRNA transduction

pGFP-V-RS plasmids expressing the 29mer shRNA against human JMJD3 or control shRNA were purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). Recombinant retrovirus expressing shRNA were packaged in 293FT (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and concentrated using the PEG-IT virus precipitation solution (System Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). Transduction of OCI-AML3 and bone marrow CD34+ cells with virus was performed by mixing virus with cell suspension followed by centrifugation at 30°C for 90 min with 4mg/ml polybrene in medium. After viral transduction, OCI-AML3 cells with stable expression of the shRNA against JMJD3 or a control scrambled shRNA were established in the presence of puromycine (10 mg /ml) in medium.

Immunocytochemical analysis

Immunocytochemical analysis was performed using a cytospin preparation of CD34+ enriched mononuclear cells according to standard procedures (15). The following antibodies were used: serine 276 phosphorylated p65 (p-p65, active form) (Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, Danvers, MA), and JMJD3 raised in rabbit against affinity-purified GST-JMJD3 (amino acids 798–1095) following previously published method.(16) The antisera were affinity-purified on GST-JMJD3. Photomicrographs were captured using an Olympus BX41 dual head light microscope equipped with an Olympus Q-Color 5 digital camera (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA), with a 20× plan-apochromat objective. Digital images were obtained and adjusted using Adobe Photoshop CS3.

Statistical Methods

Overall survival was defined from date of sample to date of death or date last known alive; patients last known alive were censored for this analysis. To investigate associations between gene expression and overall survival, we considered splitting expression level at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles, generating three possible binary variables. Associations with clinical and demographic features at time of sample were assessed only at the median expression level. For ordered clinical features such as IPSS, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used; for binary features, such as gender, the Fisher exact test was used. For continuous variables such as percentage bone marrow blasts or hemoglobin, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used.

Results

Mapping of H3K4me3 with CHIP-Seq in primary MDS bone marrow CD34+ cells

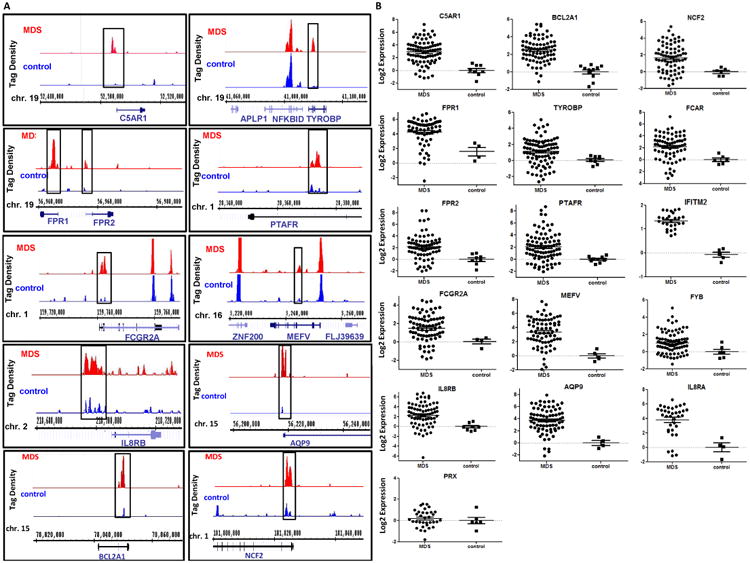

To study potential differences in the distribution of H3K4me3 between MDS and normal cells, we compared genome-wide H3K4me3 locations at gene promoter regions of 4 MDS bone BM CD34+ cell and 4 normal BM CD34+ cell genomes. Patient characteristics are shown in supplemental Table 2. H3K4me3 signals obtained in each of these 8 genomes can be viewed at http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/collaborations/ruichen/MDS. Overall CHIP-Seq data quality was confirmed by peak specificity analysis using saturation of recovery rate (supplemental Figure 1A). Genome-wide H3K4me3 peak distribution in these samples were preferentially located at the 5′ end of known genes (supplemental Figure 1B), which is consistent with previously reported H3K4me3 CHIP-Seq analysis. (9) To maximize the sensitivity to call MDS specific high H3K4me3 peaks, reads obtained from the four MDS patients and the four normal controls were pooled respectively. Using MACS approach, (13) 36 gene promoter regions (within 2Kb to TSS) with differentially higher levels (>4 fold) of H3K4me3 in MDS samples were identified (Table 1). Examples of the CHIP-Seq identified H3K4me3 signals in MDS and control CD34+ cells for 11 of these 36 genes are shown in Figure 1A. To confirm the CHIP-Seq results, we randomly selected 11 of these 36 promoters and performed H3K4me3 CHIP-PCR, which confirmed the increased levels of H3K4me3 in MDS samples for all promoters analyzed (supplemental Figure 1C). Next, we measured RNA expression for 16 of these 36 genes in MDS CD34+ cells. Number of samples used for the analysis of each gene is listed in supplemental Table 3. A summary of patient characteristics is shown in supplemental Table 4. As shown in Figure 1B and in supplemental Table 3, Q-RTPCR analysis indicated that all of the 16 genes examined, except for PRX, were significantly overexpressed in MDS CD34+ cells. As expected, these results confirmed the positive correlation between transcription activity and the level of promoter H3K4me3.

Table 1. Genes identified by CHIP-Seq to associate with high H3K4me3 at promoters in MDS CD34+ cells.

| GENE | GENE BANK # | CHR | START END (HG18) | TO TSS | FUNCTION & ASSOCIATION WITH INNATE IMMUNE OR TLR SIGNALING |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCER1G | NM_004106 | 1 | 159452113 159453525 | 403 | γ chain receptor of IgE Fc fragment. Synergize with TLR to augment production of inflammatory cytokines(39) |

| GBP5 | NM_052942 | 1 | 89510023 89510813 | -1096 | |

| PTAFR | NM_000952 | 1 | 28374310 28375848 | -1468 | Platelet activating factor receptor. Mediates recognition and intake of bacterial components (40) |

| S100A8 | NM_002964 | 1 | 151629315 151630287 | -858 | S100 calcium binding protein A 8. A chemoattractant and endogenous ligand of TLR4 (41) |

| FCGR2A | NM_021642 | 1 | 159743029 159743795 | 1186 | γ chain of receptor of IgG Fc fragment adaptor (42) |

| S100A9 | NM_002965 | 1 | 151596426 151598773 | -527 | S100 calcium binding protein A 9. A chemoattractant and endogenous ligand of TLR4 (41) |

| FGR | NM_001042747 | 1 | 27823620 27824853 | -1718 | Src tyrosin kinase (43) |

| RGS18 | NM_130782 | 1 | 190394360 190395631 | 146 | |

| NCF2 | NM_000433 | 1 | 181824396 181826329 | -1966 | Neutrophil cytosolic factor 2. Component of NADPH oxidase essential for innate immune response (44) |

| CD244 | NM_016382 | 1 | 159098292 159099253 | -977 | Natural killer cell receptor 2B4. Enhances proliferation of NK cell (45) |

| IL8RA | NM_000634 | 2 | 218738864 218739249 | -1097 | CXCR1, IL-8 receptor 1 (46) |

| SLC11A1 | NM_000578 | 2 | 218955150 218956435 | 155 | Solute carrier family 11 ion transporter (47) |

| IL8RB | NM_001557 | 2 | 218700385 218701692 | 1395 | CXCR2, IL-8 receptor 2 (46) |

| LMCD1 | NM_014583 | 3 | 8517975 8518710 | -535 | |

| FYB | NM_199335 | 5 | 39254434 39255528 | -990 | Adaptor protein for tyrosin kinase FYN. Promotes activation NF-kB (48) |

| GIMAP4 | NM_018326 | 7 | 149895232 149896350 | -158 | |

| CLDN15 | NM_014343 | 7 | 100665881 100667890 | -1955 | |

| FCN1 | NM_002003 | 9 | 136948675 136949763 | -955 | Ficolin. Activates innate immunity via complement system (49) |

| TMEM203 | NM_053045 | 9 | 139219681 139219933 | -230 | |

| IFITM2 | NM_006435 | 11 | 298793 299540 | 687 | IFN-γ induced transmembrane protein 2. Mediates antiviral signal (50) |

| CLEC7A | NM_022570 | 12 | 10172300 10172678 | -1835 | Dectin, C-type lectin receptor. Activates downstream signaling through Sky/ CARD9 (51) |

| AQP9 | NM_020980 | 15 | 56219153 56219627 | 1454 | |

| BCL2A1 | NM_004049 | 15 | 78049295 78050693 | -1403 | BCL2-related protein A (52) |

| ELMO3 | NM_024712 | 16 | 65791023 65791506 | 495 | Engulfment and cell motility protein 3 (53) |

| MEFV | NM_000243 | 16 | 3245967 3246996 | -661 | Pyrin. Modulator of innate immunity (54) |

| C5AR1 | NM_001736 | 19 | 52504812 52505462 | -131 | C5A receptor. Complement system signaling activator (55) |

| FPR1 | NM_002029 | 19 | 56945476 56946459 | -1486 | N-formylpeptide chemoattractant receptor 1. G protein-coupled receptor (56) |

| FPR2 | NM_001005738 | 19 | 56956243 56956574 | -21 | N-formylpeptide chemoattractant receptor 2. G protein-coupled receptor (56) |

| PRX | NM_181882 | 19 | 45610885 45611447 | -226 | |

| C19orf33 | NM_033520 | 19 | 43486092 43486480 | -551 | |

| FCAR | NM_133277 | 19 | 60078907 60079291 | 1547 | Receptor for IgA Fc fragment (57) |

| LRG1 | NM_052972 | 19 | 4490259 4491216 | -777 | |

| TYROBP | NM_003332 | 19 | 41090039 41091378 | -987 | ITAM containing innate immunity signal mediator (58) |

| CFD | NM_001928 | 19 | 811439 812250 | 775 | Complement factor D, C3 convertase activator (59) |

| C20orf54 | NM_033409 | 20 | 697002 697468 | -226 | |

| CD93 | NM_012072 | 20 | 23013407 23015099 | -1570 | Cell-surface glycoprotein and type I membrane protein. A receptor for C1q, can also be shedded and becoming a TLR ligand (60) |

Figure 1. H3K4me3 CHIP-Seq in primary MDS bone marrow CD34+ cells.

(a) Representative examples of H3K4me3 identified by CHIP-Seq in 11 genes in MDS (top) and control (bottom) BM CD34+ cells. Comparison between MDS and control samples indicate increased levels of H3K4me3 in the promoters of these genes in MDS CD34+ cells. (b) Logarithmic representation of Q-RTPCR results of 16 genes identified by CHIP-Seq in MDS and control CD34+ cells. These results confirm increased RNA expression in genes marked by higher levels of promoter H3K4me3 in MDS.

Genes associated with distinct high levels of H3K4me3 at their promoters in MDS BM CD34+ cells are involved in innate immunity signaling and NF-kB activation

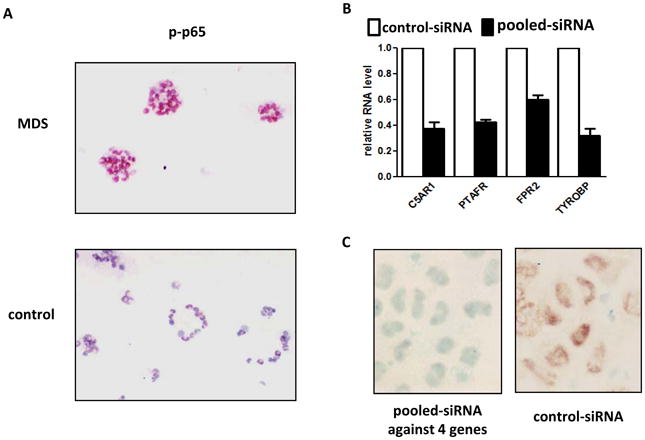

Twenty-five of the 36 genes identified by CHIP-Seq have previously been reported to be associated with innate immunity regulation (Table 1). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) indicated that 7 of these 36 genes (C5AR1, FPR2, FCGR2A, MEFV, IL8-RB, TYROBP, and PTAFR) encode upstream activators of NF-kB (supplemental Figure 2). We confirmed increased levels of promoter H3K4me3 and increased RNA expression in MDS BM CD34+ cells for all these genes (Figure 1B and 1C). Prior studies have reported NF-kB activation in MDS in MDS BM CD34+ cells. (17) We performed immunostaining of phosphorylated p65 (p-p65), a component of activated NF-kB complex, (18) in primary MDS and control BM CD34+ cell cytospins. This staining confirmed increase levels of p-p65 in MDS cells suggestive of NF-kB activation (Figure 2A). To further study the effect of the CHIP-Seq identified genes on NF-kB activity, we transfected OCI-AML3 cells with a pool of four siRNAs each individually against C5AR1, FPR2, TYROBP, and PTAFR. This led to reduced RNA expression of the four targeted genes by 40-70% respectively (Figure 2B). In the siRNA transfected OCI-AML3 cells, reduced intensity of nuclear p-p65 was observed (Figure 2C). These data indicate that these genes are involved in NF-kB activation.

Figure 2. Genes identified by CHIP-Seq are involved in NF-kB activation in MDS CD34+ cells.

(a) Immuno-histochemical analysis of phospho-p65 in MDS (Top panel) and controls (Bottom panel) bone marrow CD34+ cells. (b) Knock-down of C5AR1, FPR2, TYROBP and PTAFR in OCI-AML3 cells. (c) Immuno-histochemical analysis of phospho-p65 in the OCI-AML3 cells after knock-down of the 4 genes described above (Left panel) in comparison to control siRNA transfected cells (Right panel).

JMJD3 (KDM6b) is overexpressed in MDS BM CD34+ cells

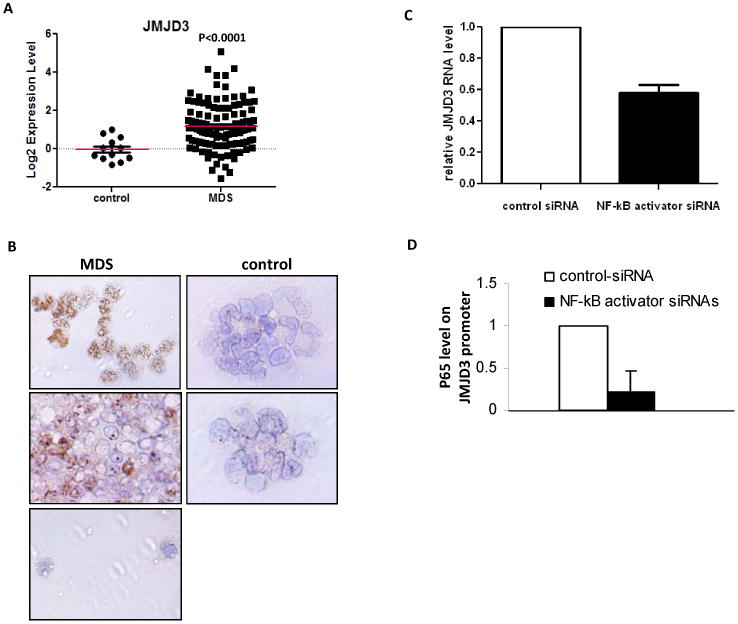

JMJD3 encodes a JmjC-domain protein with H3K27 demethylase activity and has also been demonstrated to be positively associated with H3K4me3 regulation. (19, 20) (11) JMJD3 is a known transcriptional target of NF-kB after innate immunity stimulation. 15 Because multiple of the genes identified by CHIP-Seq are involved in NF-kB activation, we studied JMJD3 expression in MDS BM CD34+ cells. RNA levels of JMJD3 were examined in a cohort with 121 samples and was found to be overexpressed in 54% of the cases (> 2 fold increase) (Figure 3A). The average JMJD3 RNA level in the whole cohort was 8 fold of control normal CD34+ cell samples (p<0.0001) (Figure 3C and supplemental Table 3). To investigate whether overexpression of JMJD3 in MDS CD34+ cells is specific among multiple histone demethylases, we analyzed the RNA expression of 19 other histone demethylases (supplemental Figure 3A). The only other histone demethylase significantly overexpressed in MDS CD34+ cells was JMJD1A, but its overall levels of upregulation and statistical significance were both lower than JMJD3 (supplemental Figure 3B). To further characterize JMJD3 expression in MDS BM CD34+ cells, we performed immune-histochemical staining of JMJD3 protein in primary BM CD34+ cytospins of patients with MDS (N=7) and healthy controls (N=2). Five of the seven MDS samples examined had strong JMJD3 signals in the cell nucleus, whereas both control CD34+ specimens had very weak nuclear JMJD3 signals (Figure 3B). These results are consistent with the RNA expression data described above. Since JMJD3 has been shown to be expressed in macrophages, 18 and to exclude macrophage contamination in the MDS CD34+ specimens analyzed, we stained cytospins from CD34 enriched MDS BM cells with CD68, a marker of human macrophage lineage.(21) No CD68 signal was detected (supplemental Figure 3C).

Figure 3. JMJD3 expression in MDS BM CD34+ cells.

(a) Logarithmic representation of JMJD3 Q-RTPCR results in MDS and control CD34+ cells in 121 MDS CD34+ samples. (b) Immuno-histochemical analysis of JMJD3 in cytospins of MDS (Left 3 panels: Top 2 with strong JMJD3 staining and Bottom 1 with weak JMJD3 staining) and controls (Right 2 panels: both with weak JMJD3 staining) bone marrow CD34+ cells. (c) Q-RTPCR analysis of JMJD3 RNA expression in OCI-AML3 cells transfected with siRNAs targeting C5AR1, FPR2, TYROBP and PTAFR or controls. (d) p65 CHIP-PCR analysis of JMJD3 promoter in the OCI-AML3 cells transfected with the siRNAs targeting C5AR1, FPR2, TYROBP and PTAFR or controls.

JMJD3 contributes to form a positive feedback loop between NF-kB activation and genes identified by CHIP-Seq

To study the relation between JMJD3, NF-kB activation and genes identified by CHIP-Seq, we transfected OCI-AML3 with siRNAs against C5AR1, FPR2, PTAFR and TYROBP. Together with the reduction in NF-kB activation shown above (Figure 2B), we also observed a decrease in JMJD3 RNA expression (Figure 3C). This was accompanied by dissociation of the NF-kB p65 subunit from the consensus NF-kB binding site of JMJD3 promoter (Figure 3D). These results indicated that multiple genes identified by CHIP-Seq in MDS could positively regulate the transcription of JMJD3 via NF-kB.

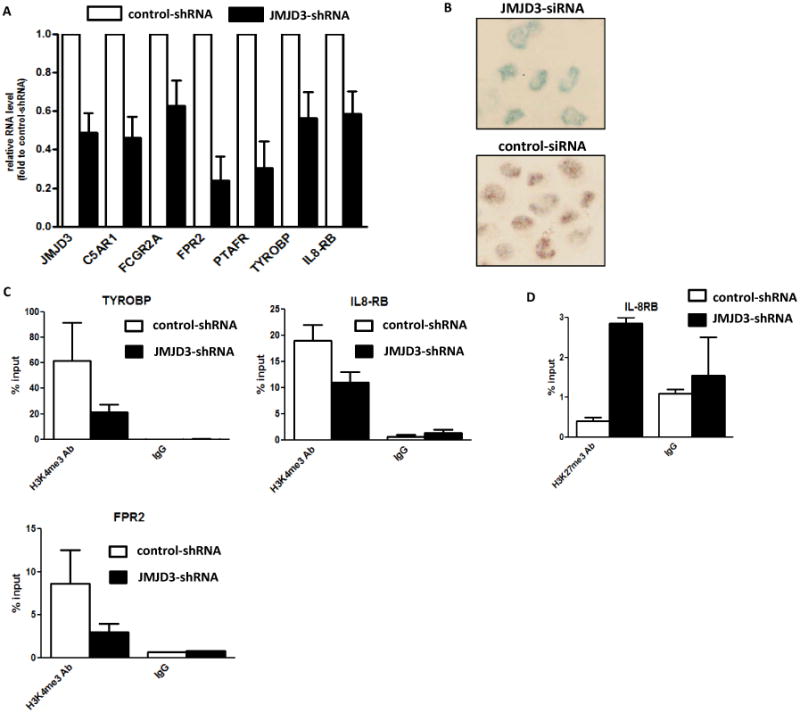

In activated murine macrophages, genomic distribution of JMJD3 strongly correlates with positive regulation of the H3K4me3 levels at promoter regions, rather than with the changes of H3K27me3.(22) Therefore, we studied the relationship between JMJD3 and genes identified by CHIP-Seq. We established an OCI-AML3 cell line that constitutively expresses a shRNA against JMJD3. These cells had a 50% decrease of JMJD3 RNA (Figure 4A). RNA expression for 6 of the 7 genes identified by CHIP-Seq involved in NF-kB activation (except for MEFV) was reduced (ranging between 35-65%) compared to control cells (Figure 4A). Knock-down of JMJD3 in also led to decrease of NF-kB p-p65 signal in nucleus OCI-AML3 cells (supplemental Figure 4 and Figure 4B). To further characterize the impact of JMJD3 on histone methylation at the promoters of these genes, we measured the levels of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3. In JMJD3 knock-down cells, reduced H3K4me3 levels were observed in the promoters of IL8RB, TYROBP and FPR2 (Figure 4C), whereas increased H3K27me3 was detected only in the promoter of IL8RB (Figure 4D). We also observed that overall promoter H3K27me3 signals were weaker than H3K4me3. Finally, in primary MDS BM CD34+ cells, the expression levels of JMJD3 were associated in a positive fashion with the expression levels of the following CHIP-Seq identified genes: IL8RB (N=71, R=0.5, p<0.0001), TYROBP (N=80, R=0.42, p=0.0001), PTAFR (N=78, R=0.6, p<0.0001), and FCGR2A (N=58, R=0.5, p<0.0001). Taken together, these results suggest that JMJD3 is involved in the transcription upregulation of the genes identified by CHIP-Seq involved in NF-kB activation.

Figure 4. JMJD3 is involved in transcriptional regulation of genes identified by CHIP-Seq.

(a) Q-RTPCR analysis of RNA expression of 6 genes involved in NF-kB activation in OCI-AML3 cells after JMJD3 knock-down. (b) Immuno-histochemical analysis of phospho-p65 in the OCI-AML3 cells with JMJD3 knock-down (Top panel) and in control cells (Bottom panel). (c) H3K4me3 CHIP-PCR analysis of IL8RB, TYROBP, and FPR2 in the OCI-AML3 cells after JMJD3 knock-down. (d) H3K27me3 CHIP-PCR analysis of IL8RB in the OCI-AML3 cells after JMJD3 knock-down.

Deep sequencing of JMJD3 in MDS

To further explore potential alteration of JMJD3 in MDS, we performed capture deep sequencing of the JMJD3 gene and JMJD1A gene in 40 MDS whole bone marrow mononuclear cell (WBM-MNC) specimens (Supplemental Table 3). Two rare single nucleotides (SNPs) of JMJD3 (CCT-TCT: Pro1313-Ser; CCG-TG: Pro642-Leu) and one SNP of JMJD1A (TCT-GCT: Ser423-Ala) were identified (Supplemental Figure 5). However, all three SNPs were also present in bone marrow CD3+ T cells from the same patients and therefore unlikely to be somatic.

Inhibition of JMJD3 positively regulates CFU-E formation in MDS BM CD34+ cells

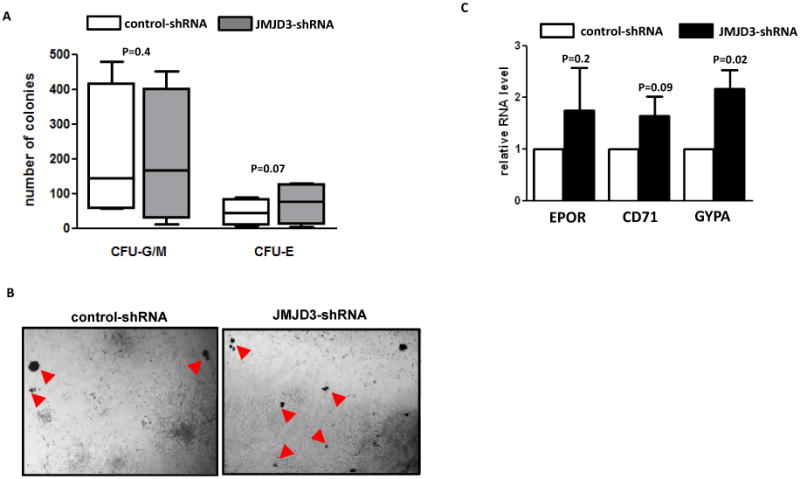

Anemia is one of the most common clinical manifestations of MDS. Erythroid colony formation is known to be decreased in cultured MDS BM CD34+ cells. (23, 24) We observed that BM CD34+ cells isolated from lower-risk (IPSS low-risk and intermediate-1) and higher-risk (IPSS intermediate-2 and high-risk) MDS both had significantly lower numbers of erythroid colony forming units (CFU-E) in methylcellulose medium (methocult) supported clonogenic assays (supplemental Figure 6A). We also used methocult assays to examine the impact of JMJD3 inhibition on the hematopoietic potential of MDS CD34+ cells. We transduced primary BM CD34+ cells isolated from patients with newly diagnosed lower-risk MDS (N=4) and higher-risk MDS (N=4) with a recombinant retroviral mediated shRNA against JMJD3. Patient characteristics are described in Supplemental Table 4. JMJD3 shRNA resulted in reduced levels of JMJD3 RNA expression in primary MDS BM CD34+ cells examined (supplemental Figure 6C). After 2 weeks of culture in methocult medium, discrepant effects on colony formation were observed between lower-risk and higher-risk samples. Three out of 4 lower-risk samples had an increased number of CFU-E after JMJD3 shRNA transduction (Figure 5A). On average, after JMJD3-shRNA transduction, seventy-three CFU-E were formed per 104 MDS BM CD34+ cells plated, which was a 52% increase compared to the number of CFU-E formed after control-shRNA transduction (Figure 5A). No significant effect on the formation of myeloid colonies (CFU-G/M) was observed after JMJD3 inhibition (Figure 5A). Representative images of the methocult colonies formed from one low-risk sample are shown in Figure 5B. In contrast to the observations in lower-risk MDS, we did not observe positive effect on the formation of erythroid or myeloid colonies in any of the four BM CD34+ cells isolated from patients with higher-risk MDS (supplemental Figure 6D). To further verify the effect of JMJD3 inhibition in lower-risk samples, we measured transcripts of several genes known to be positively associated with erythroid differentiation, including Glycophorin-A (GYPA), CD71and EPOR. In the cells collected from methocult colonies, expression of all three genes was increased after JMJD3 inhibition (Figure 5C). The most significant increase was observed in GYPA. The effect on gene expression further confirmed the positive impact of JMJD3 inhibition on the differentiation of erythroid lineage in MDS BM CD34+ cells of lower-risk type of MDS.

Figure 5. Effect of JMJD3 shRNA transduction in cultured MDS bone marrow CD34+ cells.

(a) Numbers of myeloid colonies (CFU-G/M) and erythroid colonies (CFU-E) formed in methocult culture two weeks after transduction of JMJD3-shRNA and control shRNA in BM CD34+ cells isolated from patients with lower-risk MDS (low-risk and intermediate-1). (b) Representative microphotographs of colonies formed in methocult plates after transduction of control shRNA (Left panel) and JMJD3-shRNA (Right panel). Red arrows point to CFU-E. (c) Q-RTPCR analysis of the RNA levels of CD71, EPOR and GYPA in cells collected from total colonies after shRNA transduction and methocult assays.

Potential clinical implications of CHIP-Seq identified genes in MDS

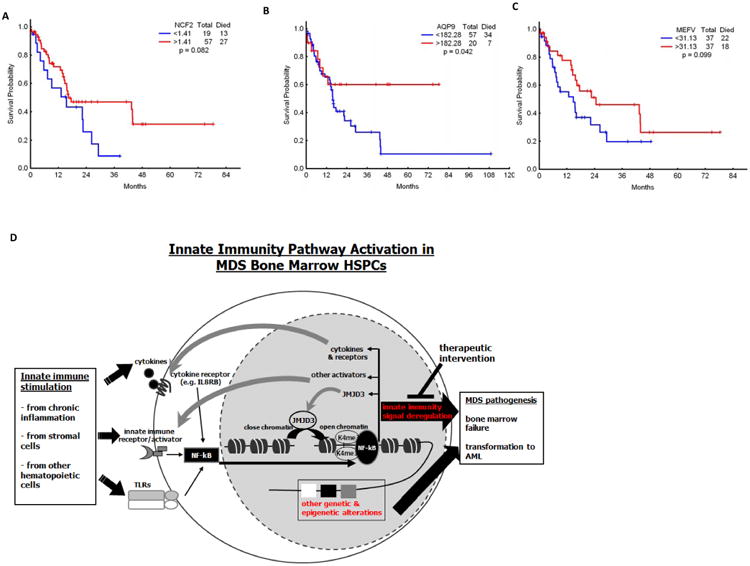

We performed an exploratory analysis of clinical implications of expression of genes identified by CHIP-Seq in MDS BM CD34+ cells. A number of the genes analyzed showed potential correlation with overall survival. This included NCF2, AQP9, and MEFV (Figure 6A-C). We also explored the association between these genes and IPSS. PTAFR (p=0.05), NCF2 (p=0.058), AQP9 (p=0.017), MEFV (p=0.012) and FCAR (p=0.019), dichotomized at their median expression levels, were associated with risk by IPSS score (25). These results are exploratory and need to be studied in larger cohorts.

Figure 6. Survival impact of gene expression in MDS and proposed model of implications of innate immunity signaling in MDS.

(a-c) Effect of mRNA expression of NCF2, AQP9 and MEFV on survival of patients with MDS. (d) Innate immunity stimulation derived from stroma, chronic inflammation or hematopoietic cells either in a para or autocrine fashion result in NF-kB activation in MDS CD34+ cells. NF-kB activation then triggers expression of multiple other effectors such as cytokines and importantly JMJD3. JMJD3 is a histone demethylase that contributes to the perpetuation of innate immunity signal and NF-kB activation. Signaling via this pathway probably cooperates with other known genetic and epigenetic lesions known to occur in MDS cells and contribute to bone marrow failure and transformation to AML that characterized MDS. Further analysis of this pathway could result in the development of inhibitors with therapeutic potential.

Discussion

It has been demonstrated that the regulation of histone methylation/ demethylation affects a wide range of essential biological processes, such as early development of embryonic stem (ES) cell.(26) H3K4 methylation has been shown to impact lineage determination during normal hematopoietic differentiation.(10) Based on this and because MDS is the result of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell dysfunction, we hypothesized that the abnormalities of H3K4 methylation could contribute to MDS pathogenesis. In this study we used genome-wide CHIP-Seq to map H3K4me3 distribution in MDS BM CD34+ cells. To our knowledge, this is the first reported use of this technology in primary samples of MDS. This analysis resulted in the identification of 36 genes characterized by increased levels of H3K4me3 in their promoters. As expected, there was a strong correlation between the CHIP-Seq identified H3K4me3 increase and gene overexpression in MDS CD34+ cells.

The large majority of genes identified by CHIP-Seq are involved in the activation of innate immunity signaling. Of note, overexpression of several innate immunity regulatory genes in CD34+ cells of MDS has been previously reported. (27) The innate immune system is the first line of defense against pathogens.(28) Recently, emerging evidence has suggested a direct regulation of HSPCs by innate immunity signaling. (29) For instance, prior studies have indicated that the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are expressed in primitive hematopoietic cells, and that acute TLR stimulation alters myeloid/lymphoid ratios, whereas chronic stimulation results in stem cell exhaustion and bone marrow failure.(30, 31) A small number of studies have also indicated a role for innate immunity deregulation in MDS. For instance, mir-145 and mir-146a have been demonstrated to regulate expression of TRAF-6, a key innate immunity regulator, in a model of del5q MDS.(29) The identification of deregulation for H3K4me3 and activation of innate immunity signal suggests that they have a potential interaction in HSPCs of MDS that should be further investigated. In this study we provide evidence that JMJD3 may potentially regulate this interaction. JMJD3 is an epigenetic regulator and is also a known transcription target of NF-kB after innate immune stimulation. (22) The identification of JMJD3 overexpression further supports that in MDS CD34+ cells innate immunity and NF-kB signaling are activated. Furthermore, its involvement in the positive regulation of multiple genes involved in NF-kB activation suggests that JMJD3 forms a feedback loop between innate immunity effectors and the activation of NF-kB. Mechanistically, we provide evidence that this feedback loop mediated by JMJD3 is associated with epigenetic regulation. After JMJD3 knock-down, decreased levels of H3K4me3 were observed at the promoters of three of the involved genes, and one gene promoter (IL-8RB) presented detectable alterations of H3K27me3. These results are consistent with prior reports that although JMJD3 is an H3K27 demethylase, it is also a component of complexes harboring H3K4me3 methyltransferase activity. (19) Furthermore, genomic distribution of JMJD3 coincides with H3K4me3 in TSS of macrophages.(22) JMJD3 has also been shown to positively regulate gene transcription through histone methylation independent mechanisms. (32, 33) Therefore, mechanisms by which JMJD3 regulates NF-kB in MDS need to be further investigated.

JMJD3 has been described as essential for cell lineage determination during cell differentiation, including macrophage, skin cells, and neurons. (19, 20) (11) In this study, we have shown that knock-down of JMJD3 in BM CD34+ cells of lower-risk type of MDS resulted in increased erythroid differentiation, potentially the formation of erythroid blasts as suggested by increased GYPA expression.(23) This result suggests that JMJD3 can affect hematopoietic lineage determination. Furthermore, this result also has therapeutic implications since anemia is one of the most common clinical presentations of patients with MDS. In contrast to the observations in lower-risk samples, JMJD3 inhibition did not affect erythroid differentiation of BM CD34+ cells of patients with higher-risk MDS. This discrepancy suggests that other molecular lesions cooperate with the deregulation of JMJD3 and innate immunity signals to contribute in the progression of MDS (Figure 6). Although results of JMJD3 inhibition in MDS BM CD34+ cells in this study should be considered exploratory and need to be validated in a larger cohort of primary MDS patient samples, they open new possibilities for the testing of potential new JMJD3 and/ or innate immunity signal inhibitors in MDS. For instance, a new JMJD3 inhibitor has recently been described. (34)

Finally, the observation that several of the genes described here may have potential prognostic value reinforces the importance of these results for the identification of patients with MDS at different risk. These results should be considered exploratory and need to be validated in a larger cohort of patients. Larger studies are needed to correlate potential associations between innate immunity deregulation and specific clinical and molecular alterations in MDS.

We realize that there are several limitations to this study. First, we have only analyzed one histone mark using genome wide CHIP-Seq in MDS BM CD34+ cells. It is known that gene expression is regulated by a complex set of chromatin modifications.(35) For instance, it is well established that poised promoters in embryonic stem cells contain both H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 (36) and that H3K4me2 is also critical for hematopoietic cell differentiation.(10) Technically it is still not possible to perform an analysis of multiple histone modifications in MDS CD34+ cells due to the very limited amount of cells available from an individual patient. Second, it has been shown that genetic manipulation of bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells can result in an MDS phenotype in mice (37) and that MDS mesenchymal cells are abnormal.(38) Therefore, other cell populations that contribute to the pathogenesis of MDS, besides CD34+ cells, should also be comprehensively analyzed. Regarding the role of JMJD3 in the regulation of multiple genes identified by CHIP-Seq, the presence of JMJD3 in the promoters of these genes still needs to be analyzed. Unfortunately, despite prior reports, there are no optimal antibodies for the CHIP of JMJD3 in human samples, particularly in primary bone marrow samples. Finally, we need to characterize the effect of enforced overexpression of JMJD3 in this setting. This is complicated due to the large size of JMJD3 gene and also to the lower transgene efficiency in MDS/ AML cells compared to other cell types.

In summary, these results suggest that a deregulation of innate immunity signals is common in the bone marrow stem/ progenitor cells of MDS and may contribute to the pathogenesis of the disease. We propose a model in Figure 6. We also provide initial evidence that further characterization of JMJD3 and associated innate immunity activating signals may have prognostic and therapeutic benefits in MDS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant RP100202 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), the Ruth and Ken Arnold Fund (GGM), the MD Anderson Cancer Center Leukemia SPORE grant CA100632, and the MD Anderson Cancer Center CCSG CA016672. IG-G was funded by the Regional Ministry of Education of Castilla-la Mancha, Spain, supported by the European Social Fund (ESF). We are thankful for the efforts from Drs. Hui Yao, Lixia Diao and Jing Wang (Department of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, MDACC) for initial analysis for CHIP-Seq data. We are thankful also to Drs. Sean Post and Zeev Estrov for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflict of interest with the data presented here.

References

- 1.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1872–85. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Manero G, Fenaux P. Hypomethylating Agents and Other Novel Strategies in Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(10):516–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cutler CS, Lee SJ, Greenberg P, Deeg HJ, Perez WS, Anasetti C, et al. A decision analysis of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes: delayed transplantation for low-risk myelodysplasia is associated with improved outcome. Blood. 2004;104(2):579–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slape C, Lin YW, Hartung H, Zhang Z, Wolff L, Aplan PD. NUP98-HOX translocations lead to myelodysplastic syndrome in mice and men. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008;(39):64–8. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn014. Epub 2008/07/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schanz J, Steidl C, Fonatsch C, Pfeilstocker M, Nosslinger T, Tuechler H, et al. Coalesced multicentric analysis of 2,351 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes indicates an underestimation of poor-risk cytogenetics of myelodysplastic syndromes in the international prognostic scoring system. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):1963–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bejar R, Levine R, Ebert BL. Unraveling the molecular pathophysiology of myelodysplastic syndromes. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(5):504–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.1175. Epub 2011/01/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, et al. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(26):2496–506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. Epub 2011/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Cazzola M, Boultwood J, Malcovati L, Vyas P, Bowen D, et al. Somatic SF3B1 mutation in myelodysplasia with ring sideroblasts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(15):1384–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103283. Epub 2011/10/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell. 2007;129(4):823–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.009. Epub 2007/05/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orford K, Kharchenko P, Lai W, Dao MC, Worhunsky DJ, Ferro A, et al. Differential H3K4 methylation identifies developmentally poised hematopoietic genes. Developmental cell. 2008;14(5):798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.002. Epub 2008/05/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jepsen K, Solum D, Zhou T, McEvilly RJ, Kim HJ, Glass CK, et al. SMRT-mediated repression of an H3K27 demethylase in progression from neural stem cell to neuron. Nature. 2007;450(7168):415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06270. Epub 2007/10/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. Epub 2009/05/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9(9):R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. Epub 2008/09/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20(9):1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. Epub 2010/07/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bueso-Ramos CE, Rocha FC, Shishodia S, Medeiros LJ, Kantarjian HM, Vadhan-Raj S, et al. Expression of constitutively active nuclear-kappa B RelA transcription factor in blasts of acute myeloid leukemia. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(2):246–53. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.08.020. Epub 2004/03/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agger K, Cloos PA, Rudkjaer L, Williams K, Andersen G, Christensen J, et al. The H3K27me3 demethylase JMJD3 contributes to the activation of the INK4A-ARF locus in response to oncogene- and stress-induced senescence. Genes & development. 2009;23(10):1171–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.510809. Epub 2009/05/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun T, Carvalho G, Coquelle A, Vozenin MC, Lepelley P, Hirsch F, et al. NF-kappaB constitutes a potential therapeutic target in high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2006;107(3):1156–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1989. Epub 2005/10/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakurai H, Chiba H, Miyoshi H, Sugita T, Toriumi W. IkappaB kinases phosphorylate NF-kappaB p65 subunit on serine 536 in the transactivation domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274(43):30353–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30353. Epub 1999/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Santa F, Totaro MG, Prosperini E, Notarbartolo S, Testa G, Natoli G. The histone H3 lysine-27 demethylase Jmjd3 links inflammation to inhibition of polycomb-mediated gene silencing. Cell. 2007;130(6):1083–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen GL, Webster DE, Barragan DI, Chang HY, Khavari PA. Control of differentiation in a self-renewing mammalian tissue by the histone demethylase JMJD3. Genes Dev. 2008;22(14):1865–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.1673508. Epub 2008/07/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cibull TL, Thomas AB, O'Malley DP, Billings SD. Myeloid leukemia cutis: a histologic and immunohistochemical review. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2008;35(2):180–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00784.x. Epub 2008/01/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Santa F, Narang V, Yap ZH, Tusi BK, Burgold T, Austenaa L, et al. Jmjd3 contributes to the control of gene expression in LPS-activated macrophages. The EMBO journal. 2009;28(21):3341–52. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.271. Epub 2009/09/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frisan E, Vandekerckhove J, de Thonel A, Pierre-Eugene C, Sternberg A, Arlet JB, et al. Defective nuclear localization of Hsp70 is associated with dyserythropoiesis and GATA-1 cleavage in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;119(6):1532–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343475. Epub 2011/12/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawada K, Sato N, Notoya A, Tarumi T, Hirayama S, Takano H, et al. Proliferation and differentiation of myelodysplastic CD34+ cells: phenotypic subpopulations of marrow CD34+ cells. Blood. 1995;85(1):194–202. Epub 1995/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89(6):2079–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vastenhouw NL, Schier AF. Bivalent histone modifications in early embryogenesis. Current opinion in cell biology. 2012;24(3):374–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.03.009. Epub 2012/04/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pellagatti A, Cazzola M, Giagounidis A, Perry J, Malcovati L, Della Porta MG, et al. Deregulated gene expression pathways in myelodysplastic syndrome hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2010;24(4):756–64. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.31. Epub 2010/03/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140(6):805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. Epub 2010/03/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Starczynowski DT, Kuchenbauer F, Argiropoulos B, Sung S, Morin R, Muranyi A, et al. Identification of miR-145 and miR-146a as mediators of the 5q- syndrome phenotype. Nat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nm.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esplin BL, Shimazu T, Welner RS, Garrett KP, Nie L, Zhang Q, et al. Chronic exposure to a TLR ligand injures hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(9):5367–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003438. Epub 2011/03/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, Bahrun U, Kouro T, Akira S, et al. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24(6):801–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. Epub 2006/06/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen S, Ma J, Wu F, Xiong LJ, Ma H, Xu W, et al. The histone H3 Lys 27 demethylase JMJD3 regulates gene expression by impacting transcriptional elongation. Genes & development. 2012;26(12):1364–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.186056.111. Epub 2012/06/21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller SA, Mohn SE, Weinmann AS. Jmjd3 and UTX play a demethylase-independent role in chromatin remodeling to regulate T-box family member-dependent gene expression. Molecular cell. 2010;40(4):594–605. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.028. Epub 2010/11/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruidenier L, Chung CW, Cheng Z, Liddle J, Che K, Joberty G, et al. A selective jumonji H3K27 demethylase inhibitor modulates the proinflammatory macrophage response. Nature. 2012;488(7411):404–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11262. Epub 2012/07/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice JC, Allis CD. Code of silence. Nature. 2001;414(6861):258–61. doi: 10.1038/35104721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125(2):315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. Epub 2006/04/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raaijmakers MH, Mukherjee S, Guo S, Zhang S, Kobayashi T, Schoonmaker JA, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464(7290):852–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Villar O, Garcia JL, Sanchez-Guijo FM, Robledo C, Villaron EM, Hernandez-Campo P, et al. Both expanded and uncultured mesenchymal stem cells from MDS patients are genomically abnormal, showing a specific genetic profile for the 5q- syndrome. Leukemia. 2009;23(4):664–72. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.361. Epub 2009/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annual review of immunology. 1999;17:931–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. Epub 1999/06/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fillon S, Soulis K, Rajasekaran S, Benedict-Hamilton H, Radin JN, Orihuela CJ, et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor and innate immunity: uptake of gram-positive bacterial cell wall into host cells and cell-specific pathophysiology. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6182–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6182. Epub 2006/10/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogl T, Tenbrock K, Ludwig S, Leukert N, Ehrhardt C, van Zoelen MA, et al. Mrp8 and Mrp14 are endogenous activators of Toll-like receptor 4, promoting lethal, endotoxin-induced shock. Nature medicine. 2007;13(9):1042–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1638. Epub 2007/09/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bave U, Magnusson M, Eloranta ML, Perers A, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Fc gamma RIIa is expressed on natural IFN-alpha-producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and is required for the IFN-alpha production induced by apoptotic cells combined with lupus IgG. J Immunol. 2003;171(6):3296–302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3296. Epub 2003/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowell CA, Soriano P, Varmus HE. Functional overlap in the src gene family: inactivation of hck and fgr impairs natural immunity. Genes & development. 1994;8(4):387–98. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.387. Epub 1994/02/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eklund EA, Kakar R. Recruitment of CREB-binding protein by PU.1, IFN-regulatory factor-1, and the IFN consensus sequence-binding protein is necessary for IFN-gamma-induced p67phox and gp91phox expression. J Immunol. 1999;163(11):6095–105. Epub 1999/11/26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown MH, Boles K, van der Merwe PA, Kumar V, Mathew PA, Barclay AN. 2B4, the natural killer and T cell immunoglobulin superfamily surface protein, is a ligand for CD48. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188(11):2083–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2083. Epub 1998/12/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Godaly G, Hang L, Frendeus B, Svanborg C. Transepithelial neutrophil migration is CXCR1 dependent in vitro and is defective in IL-8 receptor knockout mice. J Immunol. 2000;165(9):5287–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5287. Epub 2000/10/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez MA, Li S, Tremblay ML, Olivier M. NRAMP-1 expression modulates protein-tyrosine phosphatase activity in macrophages: impact on host cell signaling and functions. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282(50):36190–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703140200. Epub 2007/10/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coppolino MG, Krause M, Hagendorff P, Monner DA, Trimble W, Grinstein S, et al. Evidence for a molecular complex consisting of Fyb/SLAP, SLP-76, Nck, VASP and WASP that links the actin cytoskeleton to Fcgamma receptor signalling during phagocytosis. Journal of cell science. 2001;114(Pt 23):4307–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4307. Epub 2001/12/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsushita M, Endo Y, Fujita T. Cutting edge: complement-activating complex of ficolin and mannose-binding lectin-associated serine protease. J Immunol. 2000;164(5):2281–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2281. Epub 2000/02/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brass AL, Huang IC, Benita Y, John SP, Krishnan MN, Feeley EM, et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139(7):1243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. Epub 2010/01/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, Akira S, Underhill DM. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;197(9):1107–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. Epub 2003/04/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sukumaran B, Carlyon JA, Cai JL, Berliner N, Fikrig E. Early transcriptional response of human neutrophils to Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. Infection and immunity. 2005;73(12):8089–99. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8089-8099.2005. Epub 2005/11/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gumienny TL, Brugnera E, Tosello-Trampont AC, Kinchen JM, Haney LB, Nishiwaki K, et al. CED-12/ELMO, a novel member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac pathway, is required for phagocytosis and cell migration. Cell. 2001;107(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00520-7. Epub 2001/10/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Centola M, Wood G, Frucht DM, Galon J, Aringer M, Farrell C, et al. The gene for familial Mediterranean fever, MEFV, is expressed in early leukocyte development and is regulated in response to inflammatory mediators. Blood. 2000;95(10):3223–31. Epub 2000/05/16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerard NP, Hodges MK, Drazen JM, Weller PF, Gerard C. Characterization of a receptor for C5a anaphylatoxin on human eosinophils. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1989;264(3):1760–6. Epub 1989/01/25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Y, Gong W, Li B, Dunlop NM, Shen W, Su SB, et al. Utilization of two seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptors, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 and formyl peptide receptor, by the synthetic hexapeptide WKYMVm for human phagocyte activation. J Immunol. 1999;163(12):6777–84. Epub 1999/12/10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen L, Collins JE, Schoenborn MA, Maliszewski CR. Lipopolysaccharide and cytokine augmentation of human monocyte IgA receptor expression and function. J Immunol. 1994;152(8):4080–6. Epub 1994/04/15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomasello E, Desmoulins PO, Chemin K, Guia S, Cremer H, Ortaldo J, et al. Combined natural killer cell and dendritic cell functional deficiency in KARAP/DAP12 loss-of-function mutant mice. Immunity. 2000;13(3):355–64. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00035-2. Epub 2000/10/06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu Y, Ma M, Ippolito GC, Schroeder HW, Carroll MC, Volanakis JE. Complement activation in factor D-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(25):14577–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261428398. Epub 2001/11/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeon JW, Jung JG, Shin EC, Choi HI, Kim HY, Cho ML, et al. Soluble CD93 induces differentiation of monocytes and enhances TLR responses. J Immunol. 2010;185(8):4921–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904011. Epub 2010/09/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.