Abstract

Background

Many adolescents are at risk of dental caries and periodontal disease, which may be controlled through health education and clinical preventive interventions provided by oral health and dental therapists (therapists). Senior clinicians (SCs) can influence the focus of dental care in the New South Wales (NSW) Public Oral Health Services as their role is to provide clinical support and advice to therapists, advocate for their communities, and inform Local Health District (LHD) managers of areas for clinical quality improvement. The objective of this study was to record facilitating factors and strategies that are used by SCs to encourage therapists to provide preventive care and advice to adolescent patients.

Methods

In-depth, semistructured interviews were undertaken with 16 SCs from all of the 15 NSW LHDs (nine rural and six metropolitan). A framework matrix was used to systematically code data and enable key themes to be identified for analysis.

Results

All SCs from the 15 NSW Health LHDs participated in the study. Factors influencing SCs’ ability to integrate preventive care into clinical practice were: 1) clinical leadership and administrative support, 2) professional support network, 3) clinical and educational resources, 4) the clinician’s patient management aptitude, and 5) clinical governance processes. Clinical quality improvement and continuing professional development strategies equipped clinicians to manage and enhance adolescents’ confidence toward self-care.

Conclusion

This study shows that SCs have a clear understanding of strategies to enhance the therapist’s offer of scientific-based preventive care to adolescents. The problem they face is that currently, success is measured in terms of relief of pain activities, restorations placed, and extraction of teeth, which is an outdated concept. However, to improve clinical models of care will require the overarching administrative authority, NSW Health, to accept that the scientific evidence relating to dental care has changed and that management monitoring information should be incorporated into NSW Health reforms.

Keywords: preventive oral health care, scientific evidence, dental therapists and oral health therapists’ clinical practice

Background

Oral health is integral to general health. Good oral health enables people to communicate effectively, have optimal quality of life, and maintain positive self-esteem and social self-confidence.1 However, adolescents are at risk of developing dental caries and periodontal disease because many tend to have high-sugar diets, poor oral hygiene practices, and limited use of fluoride toothpaste; use tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs; and have unique social and psychological needs.2–5

Australian epidemiological studies have reported that approximately 50% of adolescents suffer from dental caries, with increased prevalence among disadvantaged groups and those residing in rural and remote regions.6,7 These problems highlight the importance of ensuring that adolescents accessing public oral health services are offered clinical preventive care such as protective sealants for indicated permanent teeth and fluoride applications.2,8–11 Modifications in adolescents’ health behaviors can assist in preventing oral diseases by reducing the frequency of sugary foods and drinks intake, brushing teeth and gums twice a day with fluoride toothpaste, drinking fluoridated tap water, reducing alcohol intake, ceasing tobacco use, and participating in regular professional oral health checkups.2 However, researchers have reported an existing gap between scientific advances and their clinical application.12,13

Researchers14–22 recommend the following preventive care strategies for patients at risk of developing dental disease:

Dietary advice (including drinks)

Oral hygiene education

Clinical fluoride treatments

Protective sealants for indicated permanent teeth

Personalized oral health review time frame for high-risk individuals

Smoking cessation brief intervention

Use of motivational interviewing (MI) techniques.

Common obstacles about the knowledge translation of evidence-based preventive care into clinical practice included time factors, remuneration for the implementation of preventive evidence-based practice by health practitioners, and psychosocial factors of dental professionals and patients.23–25 The primary focus of any oral health care system should be prevention, considering the important links between oral disease and obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, oral cancer, and low birth weight aligned with the common risk factor principles.1,26,27

In the State of New South Wales (NSW), the Ministry of Health is the system administrator and purchaser, funding the Local Health Districts (LHDs) responsible for delivering health services required to address local community needs.28,29 The NSW Public Oral Health Services provide a range of services. Clinical preventive care and oral health promotion (OHP) focused on addressing the social determinants of disease, offering free oral health care to eligible patients (on government health care benefits) according to criteria that prioritize emergency situations, those in pain, and those living in deprived areas of the State.28,29

All adolescents in NSW are eligible for free public oral health care provided by dental therapists and oral health therapists through primary community health, hospital, and school settings.28 Dental therapists and oral health therapists registered with the Dental Board of Australia provide clinical dental treatment and preventive oral health care for all children and adolescents under the age of 18.30 Oral health therapists have advanced hygienist skills that enable them to provide hygiene services for eligible patients above 18 years of age as prescribed by a registered dentist.30 The term “therapists” will be used from here onward to describe both groups unless indicated otherwise. Therapists in public health settings are well placed to offer preventive advice and care to control dental caries and periodontal disease for adolescents, as clinical prevention is a key performance indicator.26,31 Therapists have an established consultative and collaborative clinical working relationship with dentists and pediatric dental specialists.32

Professional clinical leadership support for therapists is provided by senior clinicians (SCs) in each LHD in accordance with the NSW Health oral health therapist award30 and NSW Health-specific oral health policies.33–35 These SCs, in addition to undertaking clinical care, also provide advice to health service managers regarding the development and provision of evidence-based clinical services and patient-centered models of care.30

Leadership within organizations is important in influencing workers’ perceptions, response to organizational change, acceptance of health innovations and scientific informed practice.36 There is currently little information on how SCs support and empower therapists to integrate published scientific-based preventive care into their daily clinical practice.16 For example, placement of fissure sealants, offer of topical fluorides, oral hygiene instruction, dietary counseling, smoking cessation advice, and utilization of MI techniques are means to improve compliance with preventive care advice.10,17,19–21,37 Therefore, this study was undertaken to record the strategies and facilitating factors that SCs use to enhance the type and scope of preventive care offered by therapists in their day-to-day dental care of adolescents.

Methods

Ethics approval was obtained from lead NSW Health and Research Ethics Committee, Hunter New England LHD: HNEHREC 12/02//15/5.04 and all 15 LHDs.

The study was conducted across the 15 NSW LHDs from September 2012 to April 2013. This study is part of a larger research project investigating the provision of preventive care provided to adolescents accessing NSW Public Oral Health Services. Qualitative in-depth semistructured face-to-face interviews were used to collect the data. All SCs working in each of the 15 LHDS in NSW were invited to participate in the study. One LHD had two SCs (coastal and hinterland). The interview sessions were conducted in the LHDs where they were most convenient for the participants, and lasted between 45 minutes and 1 hour. The researcher (AVM) who conducted all the interviews had previous oral health qualitative research experience, and was familiar with public oral health organizations. An advisory group of two pediatric dental specialists, an academic oral health advisor and an experienced therapist guiding the study, developed key questions that were tested and further validated in a focus group with therapists. These open questions were used to gain insight into SC participants’ understanding of real workplace situations and processes.38 The researcher requested each SC to reflect and respond to key open questions on their perceptions of influencing factors and strategies that could support and enhance therapists’ clinical preventive practices (Figure S1). Consent was obtained to record the interviews in order to assist the note taking and support the data collection and analysis.

Coding and categorizing of each participant’s responses to the interview questions occurred immediately after the interviews. Saturation point was reached when responses to the same question plateaued or became repetitive and no new concepts were revealed by later participants.

During the interviews, the majority of the SCs freely offered to showcase dental surgery clinical setups for OHP and preventive care, further providing documentation as evidence to illustrate LHD processes. Although not a grounded theory research study, this technique is aligned with Glaser and Holton’s dictum that all data collected from the setting is relevant to inform the research inquiry.39

The qualitative data analysis continued after the face-to-face interview sessions using the thematic analysis inductive approach.40 Systematic steps pertaining to thematic analysis40 were followed: 1) familiarization with data by synthesizing all data into a framework matrix using Microsoft Excel, 2) creating codes that identified unique features of the data relevant to the research questions, 3) review and further development of themes as dictated by the collected data, 4) comprehensive, inclusive, and thorough examination of the codes to identify patterns of meaning (generating themes), 5) data were analyzed (by the first author AVM, further critiqued and recategorized by ASB and FAB), interpreted, and a narrative was composed of key themes, and 6) verification of processes by academic principal investigators.

Additionally, techniques adopted to ensure the rigor of this research included: 1) research conducted and supervised by an academic organization advisory group external from the NSW Ministry of Health, 2) audit trails for administration purposes, 3) a note-taking journal used during the interviews and for advisory group reflective narrations throughout the study, 4) summarization and confirmation of key points with participants to conclude the interview session, and 5) consent to recontact the participants for further clarification of any pertinent points during the data analysis stages.

Results

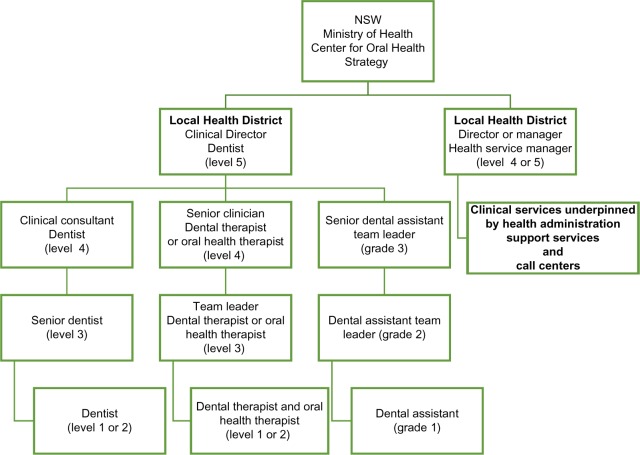

All SCs from the 15 NSW Health LHDs (six metropolitan and nine rural) consented to participate in the study. One LHD had two SCs (coastal and hinterland). Preventive care was personally valued by all respondents, as a professional clinical ethos that underpinned their clinical leadership approach at multiple levels. The overarching theme that emerged from participants’ commonly identified responses that were coded and categorized for this study was: “Enhancing therapists’ scientific-based clinical preventive care practice to support adolescents,” with five subthemes described in the following sections as illustrated in Figure 1. However, the subthemes overlapped and were interconnected; consequently, a topic can appear in a number of themes.

Figure 1.

Influencing factors to enhance the provision of clinical preventive care to adolescents accessing NSW Public Oral Health Services.

Abbreviation: NSW, New South Wales.

Clinical leadership and health service administration network support

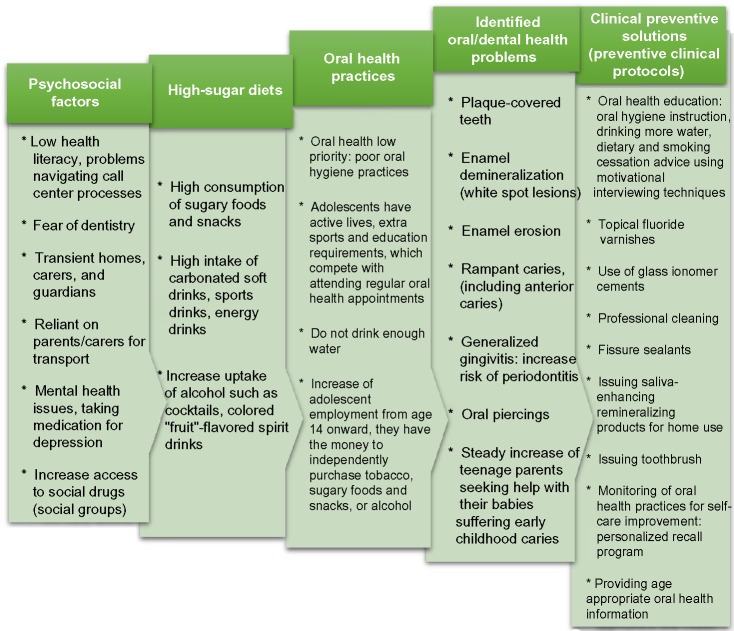

A clear hierarchical clinical leadership structure (Figure 2) within each LHD was reported essential for communication and implementation of NSW Health policies to inform and enhance therapists’ preventive clinical practice by all participants. Conferring and collaborating as a professional oral health team at multiple levels (Figure 2) was stated as conducive to the therapist’s ability and compliance to provide preventive care to adolescents.

Figure 2.

Clinical professional support structure for dental therapists and oral health therapists commonly reported for LHDs.

Abbreviations: LHD, Local Health District; NSW, New South Wales.

The majority of SCs reported that they were accountable to clinical directors and health service managers, and reliant on their approval, direction, and support for the implementation of NSW Health preventive policies, scientific evidence clinical care, and OHP activities for therapists (Figure 2).

Although we have a specific oral health promotion (OHP) coordinator who liaises directly with clinical staff regarding clinical preventive programs, my role links clinical care, OHP, management of staffing resources, and education in consultation with our clinical director and health service management team. [SC05]

Fundamental efficient and effective health management and clinical administration processes were important to assist therapists in prioritizing oral health prevention as long-term quality care for adolescents. Challenges with waiting times to access oral health care were reported by 50% of SCs. Triaging systems according to NSW Health Policy, prioritizing “relief of pain” access, often led to motivated adolescents and parents needing much preventive care being placed on low-prioritized waiting lists, and they were often lost to follow-up.41

Nevertheless, 75% of participants reported that the Australian Government Benefit Scheme “Teen Dental Program” (TDP), which provided a preventive voucher for disadvantaged adolescents whose families are eligible for Family Tax A, impacted on some LHDs and shifted the focus to offering the majority of adolescents access to preventive care, irrespective of TDP eligibility.42 All participants reported that many adolescents had difficulties navigating the call center processes to access care; however, dental staff would generally assist adolescents attending to register for dental care if they expressed an interest:

… they come in with their friends for peer support or to check it out, therapists tend to chat to them, bit of apprehension there, often they are interested asking about their teeth so, if they are aged 14 and above, we are flexible, we try and triage them, give them a check-up, preventive chat, why not …. [SC09]

Two participants reported that specific prevention clinics established in consultation with pediatric dental specialists enhanced the integration of preventive care into clinic treatment plans for patients with high levels of dental disease. One rural SC reported that recently appointed oral health therapists and rural clinical student placements enabled the LHD to set up a “prevention clinic” that focused on adolescents. This was also a useful revenue-raising activity allowing TDP vouchers to be utilized for adolescent care. In addition, this enabled the establishment of referral pathways to prioritized dental care for high-risk adolescents identified by community and allied health professionals such as Aboriginal health educators, diabetes educators, and drug and alcohol agencies.

In rural settings, the rostering of mobile clinics, and better utilization of community clinics to be aligned with school holidays and clinical staff leave were critical to providing efficient oral health care services to adolescents and their communities. In two rural settings, staff endeavored to provide much needed preventive care to adolescents in centrally placed schools, typically for the initial visit, as patient travel and access needed to be coordinated with mobile van schedules.

Professional oral health workforce

Approximately 50% of the participants believed that the efficient integration of preventive care into clinical practice hinged upon an adequate therapist to dental assistant ratio working in the clinics. The efficient utilization of dental assistants at the chairside for oral health education and the full utilization of available clinical dental surgery chairs supported preventive care activities. However, the clinician’s operative clinical activities to meet health service funding accountability were a priority. For example, emergency and relief of pain-type activities such as teeth extractions and restorative treatment carried more funding weight compared with preventive clinical care such as placement of protective fissure sealants on identified permanent teeth and simple therapeutic fluoride application treatments. Additionally, oral hygiene instruction and dietary and smoking cessation advice had lower funding values. Common narratives were:

Training of dental assistants in oral health promotion has been approved by management to support clinicians. However, chairside assistant duties [assisting dentist or therapist for operative treatment] take precedence over education and oral health promotion activities. Clinical treatment activities have more funding weight and accountability compared to prevention. [SC015]

Three participants stated that specific preventive clinical protocols that had been developed in consultation with pediatric dental specialists and a periodontist enhanced the therapists’ clinical practice. Two participants commented that their preventive clinical protocols were aligned with that of a major dental teaching hospital’s pediatric unit; with one respondent reporting that therapists in their LHD participated in a fissure sealant randomized clinical trial led by the Head of Oral Health Research for the LHD. This local research study enhanced the therapists’ preventive knowledge and clinical practice, and gave them further encouragement to learn more about preventive care.

Therapists were part of a fissure sealant-randomized clinical trial research study. It provided therapists with knowledge and skills on how to gather clinical evidence, reflect on individual clinical techniques, use of different preventive dental materials and sharing of research findings at a State clinical conference presentation, it was an interesting clinical learning experience [SC011]

Approximately 25% of respondents commented on the therapists’ levels of interest in working with adolescents, particularly in relation to their confidence and competence. There was concern that therapy training schools focused on primary school-aged children and that adolescent care was given little time in the curriculum. However, in multiple-staff clinics, open communication between therapists and dentist team leaders enabled effective sharing of clinical information, and referral pathways to ensure optimal treatment and preventive care for adolescents. The increased recruitment of oral health therapists was seen as advantageous to the health service because the hygienist clinical skill set added value to the dental team, especially in terms of specialized type of oral health self-care.

Clinical resources and oral health products

Approximately 50% of respondents stated that the LHD and NSW Health-funded scientific conferences were the most cost-effective continuing professional development (CPD) strategy for therapists. Several participants mentioned that the increase in numbers of oral health therapists in conjunction with CPD was slowly shifting the emphasis of dental care from a prioritized pain relief, operative dentistry restorative approach to minimal intervention dentistry (less “drill and fill”) and stabilization of a patient’s oral environment and provision of holistic care. This was due to oral health therapists’ academic training being more focused on preventive oral health therapy philosophies in contrast to “surgical cutting/drilling of the tooth” concepts.

A key role for the majority of SCs was advocating for dental chairside preventive resources to support therapists’ clinical preventive care activities. The lack of age-appropriate literature and teaching aids for adolescents was an overall common concern. All SCs suggested that the Center for Oral Health Strategy (governing State public oral health agency, Figure 1) needed to develop adolescent age-specific oral health education resources for consistency of State health messages. Nevertheless, 75% of respondents stated that State health capital funds enabled the installation of digital imaging for their LHDs, with five respondents also stating that intraoral cameras were installed in their LHD clinics. The updated equipment enabled therapists to incorporate visual clinical digital images of “presenting oral health problems in adolescents’ mouths” [SC015] as starting points to their health education sessions.

Approximately 75% of respondents reported that their LHDs had OHP coordinators (OHPCs) who represented the therapist’s prevention requirements at State level. Approximately 75% of participants referred to OHPCs as pivotal in supporting chairside clinical preventive activities. Four respondents referred to NSW Health OHP initiatives for identified high-risk groups such as Aboriginal groups, youth, and opioid treatment programs that prioritized referral pathways for clinical care, supported with oral health resources as key enablers toward prevention of dental diseases. One rural LHD participant reported that a research-funded project enabling therapists to access free fluoride toothpaste and toothbrushes for disadvantaged families in a nonfluoridated area was a key preventive care strategy for their area. Access to oral health products was reported as being dependent on the approval of purchase orders by health service managers, with cost often a factor in their nonavailability. High-fluoride toothpaste, enamel remineralizing products, and mouthrinses were usually not available to clinicians because of their cost. Although fluoride and antibacterial mouthrinses were therapeutic agents commonly used for prevention of dental diseases, 75% of respondents stated that from their perspective, it would be more practical to persuade the therapists to concentrate on providing oral hygiene instruction promoting family fluoride toothpaste for adolescents, rather than confusing the adolescent further with the mouth rinsing concept:

I like to focus on getting adolescents to brush their teeth twice a day with fluoride toothpaste. Mouthrinses, special cases … we tell them where they can get it. [SC011]

Approximately 25% of participants stated that the numerous oral health products on the market from competing oral health companies created challenges for clinicians as well as patient use. SCs suggested that regular clinical team discussions on scientific evidence for prescribing these products to their patients were therefore necessary. Two SCs provided evidence of oral and dental product charts to guide oral health therapist’s clinical decision making, with one rural SC providing guidelines issued by two separate dental companies.

Two respondents argued that dietary advice given by therapists should be reevaluated by clinical directors, with a view to suggesting that LHDs should fund referrals to dietitians’ sessions. Dietary issues, they explained were a complex area requiring specialist attention, as adolescents at risk of dental caries should be managed by dietitians for long-term health benefits.

… look, I agree with our 131 [dietary advice], but, with examples of ToothSmart [oral health prevention program to reduce early childhood dental decay] and [dietician], are we really effective? Hard to say, seeing as sugar is a key factor in causing decay, maybe we should be much clearer and say its “brief dietary intervention”. [SC05]

Facilitating adolescent’s oral health needs

Advocating for adequate clinical appointment times for therapists to engage with, and form good working relationships with, adolescents was seen as an important part of a SC’s role:

Being strong and stating why therapists need the allocated time. Graduates are coming in as well, if they feel that there’s a kind of unwritten perception that the faster you go, the better you are. So, allowing them the time, and letting them see us do it that longer time. Getting to know their patient and getting to care for their patient is what has to be highest priority [SC013]

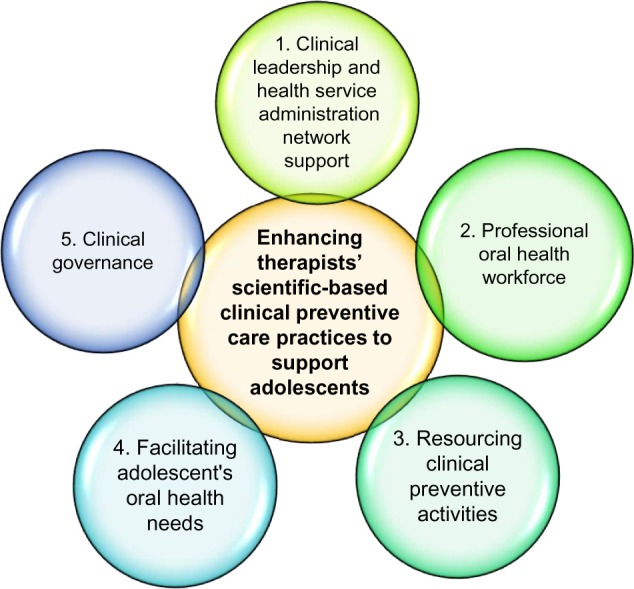

Figure 3 illustrates the majority of participants’ views on adolescents’ common oral health concerns, practices, clinical presentations, and their reported preventive solutions. The majority of the respondents referred to disadvantaged adolescents’ psychosocial determinants of oral health being: 1) fear of dentistry, 2) dependence on parents/carers for transport, 3) transient homes and disruption in their young lives, 4) lack of home support, 5) uptake of alcohol, 6) tobacco and drug use, 7) teenage pregnancy, 8) teenage parents seeking assistance for their children developing early childhood dental decay, and 9) other adolescent risk behaviors (resulting in trauma of teeth).

… adolescent age group, surrounded with all this adult external stuff, going through so much change that they can be hard to reach sometimes. Taking up smoking, drinking, drugs … having an impact on their mouth, rampant caries [dental decay]. Attitudes of adolescents can be very challenging. Teenage pregnancy and the father of the child, their children developing early childhood dental caries [SC013]

Figure 3.

Senior clinicians’ perceptions of factors affecting adolescents’ oral health issues and potential solutions.

The majority of respondents also reported adolescents’ mental status and on depression medication as noted in their self-reporting social and medical histories.

Seventy-five percent of respondents stated that adolescent patients tended to lack knowledge of what dental plaque is and how to clean their teeth adequately. The majority of respondents quantified therapists’ need for adequate clinical appointment time to engage with adolescents to understand their needs, provide coaching sessions using MI techniques to teach effective oral hygiene, and link this with dietary and smoking cessation advice.

It is knowing how to best deal with these interesting cases, like a web, different dynamics. It just becomes more complicated but fun, trying to figure them out because when you really do have somebody’s attention at that age, it has lasting ramifications and that’s a joyful thing at work from a preventive perspective [SC013]

Approximately 25% of respondents argued that trying to change managers’ frame of references on the value of prevention took time, which was disappointing and frustrating. Dental decay and chronic gingivitis were the most common dental problems reported for adolescents, both of which are caused by behavioral issues that require advice and counseling to rectify (Figure 3).

Working with adolescents with low self-esteem is motivating, bringing the change around. Adolescents are compliant when things are clearly explained to them, knowing they are supported until they are confidently making those lifelong changes. We have some real success stories. [SC03]

In six LHDs, saliva testing kits were available to assist with the education processes with just under 75% of participants unable to purchase such kits due to cost restraints.

Adolescents are challenging, we start pitching messages to address the acidity levels of their sports drinks, fizzy drinks, alcohol beverages and link it to what we see in their mouths; plaque [dental] and saliva pH tests, all learning activities for them [SC014]

Although NSW Health has policies mandating the use of protective sealants for permanent teeth, respondents suggested other effective and efficient options for adolescents, as parents often agree to further appointments during relief of pain appointments, but tend not to return. The SCs believed topical fluoride varnish should be applied immediately at that initial appointment and that fissure sealants could be applied if the patient returned. This practical option was seen as a way of assisting therapists get through their patient schedules as fluoride varnish can be applied more easily than protective sealants.

Parent commitment to appointment, easier to provide fluoride varnish, more practical than sealants, just not 100% sure they would attend next, for whatever reasons. [SC03]

Many adolescents, seeking an orthodontic assessment, attended the dental service because of concerns about their personal image. However, most did not require an orthodontic referral, but there was scope for therapists to provide preventive advice. This was seen as a positive opportunity to include prevention in the clinical system.

Although the majority of respondents stated that recall systems were critical to monitor a patient’s progress, it was unachievable in most LHDs, because it was dependent on public dental demands and waiting lists. Information of where to access dental care was provided to adolescents and parents at the completion of treatment, and guidance was offered when their eligibility to free public dental care changed.

Clinical governance

Clinical governance processes such as professional credentialing for registration and evidence of CPD enabled the majority of respondents to communicate effectively with the therapists working in their LHD to enhance their preventive clinical practice. Clinical audits utilizing patient electronic record data were used by six participants to enhance the integration of preventive care into clinical practice. The NSW Health restructure was described as advantageous for several participants as new LHDs were smaller than previous Area Health Services, enabling better communication with clinical staff and bringing managers closer to clinical operational sites.

Just over 25% of participants stated that LHDs were forming new clinical leadership partnerships. The key actions were to evaluate current OHP efforts and link in with clinical preventive care. Examples provided included referrals to therapists arising from community health promotion programs, for example, Aboriginal youth and young mothers’ groups to raise awareness for accessing the public dental services. It was important to ensure current effective community efforts to the participants, but with the caveat that clinical staff should have the capacity to cater for any increased volume of patients.

Peer reviews and clinical auditing identified areas of development for therapists, providing participants with evidence for quality improvement projects, and to ascertain areas for clinical professional development were reported by less than 50% of SCs. Clinical activity was identified by dental treatment item numbers based on The Australian National Dental Schedule System.28

I’m doing clinical audits of 011s [comprehensive oral examination] against preventive items, the usual 131 [dietary advice], 141 [oral hygiene instruction], fissure sealants 161 and their smoking cessation [191]; so, we are also doing training around the interpretation and use of prevention, like what justifies recording a “131 or 141”. [SC014]

All participants’ stated that professional education would assist therapists’ 1) clinical behavior management of adolescents and their parents, and 2) clinical management of high caries-risk patients.

Approximately 25% of participants argued that NSW Health preventive policies were ineffective as they were document statements far removed from chairside clinical situations, whereas clinical protocols were systematic in nature, providing practical clinical options to manage adolescents presenting with oral health problems. Two participants provided clinical guidelines for adolescents under 18 years of age, using step-by-step treatment care options for clinical care that assisted therapists to plan appropriate clinical and preventive care.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to record SCs’ views on the facilitating factors and strategies that would assist therapists to offer preventive care to adolescents. This study found that clinical directors’ and health service management support at multiple levels was essential to ensure efficient health administration and clinical processes to enable therapists to provide quality clinical care to patients. Moreover, a clear consultative hierarchical clinical professional structure was perceived pivotal for enhancing communication for the implementation of NSW Health preventive policies, including efforts for the translation of scientific evidence into therapist’s clinical practice.

Campbell and Tickle, in their paper on how to improve quality in primary dental care, suggested that a focus on quality across the entire health care system needs to occur if quality improvement is to transpire.43 They also explained that this is because primary care operates within a health care system delivered by teams within organizations, although care is provided by individual clinicians to individual patients. The authors suggested the need for understanding multilevel approaches for change at the: 1) individual clinician level (eg, therapist), 2) team level (eg, LHD dentist, therapist, dental assistant, and administration), and 3) the organization (LHDs), 4) the larger system (NSW Ministry of Health).

The participants in this study described the impact of the Australian Government TDP on their LHDs’ clinical processes and practices to enhance the levels of dental care for adolescents, activated by the preventive prescriptive nature of the voucher. This suggests that positive changes toward a prioritized preventive care approach should be adopted by NSW Public Oral Health Services governing agency, and supported with clear directives from LHD clinical directors and managers to clinicians. Aarons stated that leadership in organizations can importantly influence practitioners’ understandings, reactions, and acceptance to improvements in evidence-based practices.36 Transformational leadership in dentistry, according to Brocklehurst, is a fundamental process to improve service delivery and quality of care reach to patients, and future improvement for the translation of scientific-based preventive research findings into the therapist’s clinical practice.44

This study found that efficient utilization of the oral health workforce (administration and dental assistant team members) enabled therapists to support vulnerable adolescents’ access to dental care more effectively. Additionally, the establishment of working partnerships with prioritized referral pathway processes for allied health professionals, such as Aboriginal health and youth workers in support of disadvantaged adolescents groups in some LHDs, suggests that opportunities exist in local communities for therapists to enhance OHP activities to address adolescents’ social determinants of health aligned and consistent with researchers’ recommendations.1,28,29,45

Freeman highlighted the importance of dental health professionals being acquainted with the psychosocial determinants of a patient’s health behaviors, as it provides clinicians with an insight of the struggles patients are experiencing when complying with the dental health care advice.25 Participants in this study made reference to adolescent’s struggles and levels of skills and knowledge toward self-care. Freeman further alludes to dental health professionals’ psychosocial influences such as their own health beliefs, attitudes which may influence the patients’ capacity to adhere to the dental health messages.

Wallerstein’s report on the evidence of the effectiveness of empowerment to improve health discussed youth and family empowerment strategies that have enhanced disadvantaged youths’ self-care management of their health problems, modifying risk behaviors, and building caregivers’ skills and efficacy.46 Respondents in this study refer to clinical processes and areas for quality improvement to enhance the therapist’s capacity to cater for the unique psychosocial needs of vulnerable adolescents and teenage parents, with adequate time as a key-enhancing factor, to engage and encourage adolescents toward oral health self-care. The importance of multilevel professional communication and working partnerships across health professional agencies described in this study, to support therapists address adolescents psychosocial needs, is aligned with Wallerstein’s statements that alliances and “interorganizational partnerships” that engage and promote empowerment by better participation and policy changes have yielded diverse health outcomes.46 Thus, there is scope for future public oral health research into community empowerment strategies for young teenage parents and their children for long-term health outcomes.

The majority of participants advocated and argued for specific preventive clinical protocols to support and guide therapists to address adolescents’ oral health issues. Stillman-Lowe, in her paper, stated that oral health teams have a pivotal role to provide evidence-based health education information to patients, and that much more support should be provided to oral health professionals to update their clinical practice.47 The respondents highlighted the lack of adolescent-specific oral health education resources and suggested for the NSW Center for Oral Health Strategy (governing agency) to address this problem. Conversely, participants reported engaging and forming positive working relationships with patients by using digital X-ray images and intraoral photographs, saliva testing activities as effective strategies to communicate and encourage adolescent’s oral health self-care. These strategies are aligned with Blinkhorn’s recommendations to undertake practical demonstrations, as engaging the patient will make advice sessions more interesting and effective; however, further research is necessary to evaluate the efficacy of these interventions in NSW LHDs.47,48 It would be advantageous for local oral health teams to allow time during staff meetings to review short scientific articles such as the paper by Stillman-Lowe to generate discussion on the most effective methods of providing health education advice.47

Ismail et al13 reported on the findings from a number of expert workshops on various caries management pathways currently available to preserve dental tissues and promote oral health. The authors acknowledged that scientific evidence had been available for decades on how to manage dental caries, but that little change to clinical practice had occurred.13 Participants in our study stated that oral disease management system philosophies should be supported in public health settings, and advocated strongly for specific clinical protocols to help the implementation of new clinical knowledge, rather than relying on broad health policy statements that were of little practical value to clinicians working on a day-to-day basis with patients.

For example, Evans and Dennison’s caries management system (CMS) provides a clinical protocol that presents an evidence-based preventive strategy for children and adolescents. 15 A specific odontogram, using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) coding, illustrates ten clear steps for clinical actions.13 Considering CMSs are scientific-based concepts that graduates bring with them into public oral health settings, it is a matter of some concern that NSW Health LHDs have not tested the CMS protocol in the public oral health arena. Jenson et al’s17 Clinical Protocols for Caries Management by Risk Assessment also uses ICDAS coding and provides case scenarios and clinical photographs to guide clinical decision making. Merijohn et al’s49 clinical decision support chairside tools for evidence-based dental practice illustrates how to consolidate scientific evidence to facilitate clinical decision making at the chairside. It also enables efficient and effective translation of knowledge to the patient “at the point of care”.49 Jenson et al’s17 and Merijohn et al’s49 protocols have not been assessed for their potential value in the NSW Public Oral Health Services. Clinical protocols are valid tools for therapists to enhance preventive clinical practice, suggesting that LHDs’ dental clinical directors and managers should seek advice from the NSW Health Clinical Excellence Commission (CEC), Health Education and Training Institute (HETI), and the Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI) to assist clinical professional teams develop scientific clinical preventive oral health care models of care for adolescents.

This study has provided evidence that SCs want to change the focus of clinical care to cater for adolescents’ unique oral health needs. The disappointing finding is that despite the importance of preventive care, our respondents felt that their applicability in public oral health community settings had not been given high priority. The value of the public service is still being measured in terms of access for relief of pain, restorations placed, and extraction of teeth rather than improvements in oral health. Although one LHD reported participation in preventive research activities as creating a learning environment for therapists, the translation of research findings into treatment planning has not been embedded within the NSW Public Oral Health Services, highlighting the concerns raised by Ismail et al,13 Walsh and Brostek50 that implementation of a more holistic approach to dental care has been delayed by managerial inertia and a focus on relief of pain and restorative procedures.

It would be prudent for LHDs’ clinical directors to capitalize on visiting pediatric dental specialists and periodontists and tap into their expertise to develop preventive care strategies for adolescents, utilizing the latest available scientific evidence. The LHDs should obtain assistance by linking into sponsored programs available through the NSW Health networks, namely the CEC, ACI, and HETI and build on existing clinical pediatric specialist services. The NSW Health Plan outlines the importance of supporting and harnessing research and innovation, so there is official support for health service redesign.28,29

Clinical governance is an integral part of quality improvement.51,52 This study found that clinical auditing of diagnostic and preventive item numbers is one strategy which could communicate and support therapists to enhance their preventive care and advice to patients. Findings from this study illustrates the need for LHDs across NSW to develop auditing tools underpinned by evidence-based clinical protocols to ensure their applicability and usefulness for measuring therapists key performance indicators. Therefore, it is suggested that LHD health care managers and leaders seek the assistance of dental teaching hospitals and academic institutions to develop clinical protocols and evaluate their impact in terms of health outcomes over time.

All NSW LHDs were represented in the study, providing valuable information to inform future policy and clinical guidelines for therapist’s preventive clinical practice. However, studies for comparison with the findings of this research were not available as there is a dearth of research into the professional leadership practice of therapists. Clearly, more confirmatory studies are required.

All SCs from all LHDs consented to participate in the study; however, interviews were conducted during NSW Health restructuring, with four experienced participant SCs reporting that they were in acting roles, and, therefore, generalization of the findings from this study should be used with caution.

Conclusion

This research shows that SCs have a clear understanding of the issues involved in realigning a dental service to provide preventive as well as clinical care. The problem they face is that currently, success is measured in terms of relief of pain activities, restorations placed, and extraction of teeth, which is an outdated concept. However, to change clinical protocols will require the overarching administrative authority, NSW Health, to accept that the scientific evidence relating to dental care has changed, and management monitoring information will have to be redesigned.

Supplementary materials

Interview questions to be explored with senior therapists.

Abbreviation: LHD, Local Health District.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: NSW Ministry of Health Rural and Remote Allied Health Professionals Postgraduate Scholarship Scheme and Center for Oral Health Strategy.

We thank all NSW Local Health District senior dental therapists and oral health therapist clinicians who consented to participate in this study. We are grateful to clinical directors and health service managers for their approval of and support for the study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The findings from this study are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the funding body or NSW Ministry of Health. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study and the preparation and critical revision of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

References

- 1.Watt RG. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):711–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry . Guideline On Oral Health Adolescent Care. Clinical Guidelines. Chicago, IL: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2010. pp. 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Poulton R. Oral health beliefs in adolescence and oral health in young adulthood. J Dent Res. 2006;85(4):339–343. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clerehugh V. Periodontal diseases in children and adolescents. Br Dent J. 2008;204(8):469–471. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dugmore CR, Rock WP. The progression of tooth erosion in a cohort of adolescents of mixed ethnicity. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13(5):295–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armfield JM, Spencer AJ, Brennan DS. Dental Health of Australia’s Teenagers and pre-Teen Children: The Child Dental Survey, Australia 2003-04, (Dental Statistics and Research Series no 52.Cat.No.DEN 199) Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW, MoH . The New South Wales Teen Dental Survey 2010. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tickle M, Milsom KM, King D, Blinkhorn AS. The influences on preventive care provided to children who frequently attend the UK general dental service. Br Dent J. 2003;194(6):329–332. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JY, Divaris K. The ethical imperative of addressing oral health disparities: a unifying framework. J Dent Res. 2014;93(3):224–230. doi: 10.1177/0022034513511821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moynihan PJ, Kelly SA. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res. 2014;93(1):8–18. doi: 10.1177/0022034513508954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waterhouse PJ, Auad SM, Nunn JH, Steen IN, Moynihan PJ. Diet and dental erosion in young people in south-east Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(5):353–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation . Knowledge Management Strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2005. [Accessed May 27, 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/kms/about/strategy/kms_strategy.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ismail AI, Tellez M, Pitts NB, et al. Caries management pathways preserve dental tissues and promote oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:e12–e40. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arrow P. Incidence and progression of approximal carious lesions among school children in Western Australia. Aust Dent J. 2007;52(3):216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans RW, Dennison PJ. The caries management system: an evidence-based preventive strategy for dental practitioners. Application for children and adolescents. Aust Dent J. 2009;54(4):381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davies RM, Blinkhorn AS. Preventing dental caries: part 1. the scientific rationale for preventive advice. Dental Update. 2013;40(9):719–720. 722, 724–726. doi: 10.12968/denu.2013.40.9.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos-Gomez FJ, Spolsky VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35(10):714–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine AB, Stillman-Lowe C. The Scientific Basis of Oral Health Education. 6th ed. London, England: British Dental Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yevlahova D, Satur J. Models for individual oral health promotion and their effectiveness: a systematic review. Aust Dent J. 2009;54(3):190–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarkson JE, Young L, Ramsay CR, Bonner BC, Bonetti D. How to influence patient oral hygiene behavior effectively. J Dent Res. 2009;88(10):933–937. doi: 10.1177/0022034509345627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Hiiri A, Nordblad A, Makela M, Worthington HV. Pit and fissure sealants for preventing dental decay in the permanent teeth of children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD001830. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001830.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg-Smith SM, Stevens KM, Brown KM, et al. A brief motivational intervention to improve dietary adherence in adolescents. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(3):399–410. doi: 10.1093/her/14.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarkson JE. Getting research into clinical practice – barriers and solutions. Caries Res. 2004;38(3):321–324. doi: 10.1159/000077772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watt RG, McGlone P, Dykes J, Smith M. Barriers limiting dentists’ active involvement in smoking cessation. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2004;2(2):95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman R. Barriers to accessing dental care: dental health professional factors. Br Dent J. 1999;187(4):197–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nash DA. Envsioning an oral healthcare workforce for the future. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(Suppl 2):141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostberg A, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, Hakeberg M. Oral health and obesity indicators. Biomed Central Oral Health. 2012;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NSW Ministry of Health . Oral Health 2020: A Strategic Framework for Dental Health in NSW. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013. [Accessed May 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/oralhealth/Documents/oral-health-2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.NSW Ministry of Health . NSW State Health Plan Towards 2021. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2014. [Accessed August 26, 2014]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/statehealthplan/Publications/NSW-State-Health-Plan-Towards-2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.NSW Ministry of Health . Health Employees Oral Health Therapists (State) Award-New Classification Structure and Salaries. Sydney, Australia: Department of Health, NSW Ministry of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satur J, Gussy M, Marino R, Martini T. Patterns of dental therapists’ scope of practice and employment in Victoria, Australia. J Dent Educ. 2009;73(3):416–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Masoe AV, Blinkhom AS, Taylor J, Blinkhom FA. Preventive and clinical care provided to adolescents attending public oral health services New South Wales, Australia: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(142):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW . Pit and Fissure Sealants: Use of in Oral Health Services, NSW. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2013. [Accessed May 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2013/pdf/PD2013_025.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW . Smoking Cessation Brief Intervention at the Chairside: Role of Public Oral Health/Dental Service. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2009. [Accessed May 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www0.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/pd/2009/pdf/PD2009_046.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW . Fluorides – Use of in NSW. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2006. [Accessed May 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/water/Documents/PD2006-076-Use-of-Fluorides-in-NSW.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aarons GA. Transformational and transactional leadership: association with attitudes towards evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.8.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayo-Yusuf OA, Reddy PS, van den Borne BW. Adolescents’ sense of coherence and smoking as longitudinal predictors of self-reported gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(11):931–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Leary Z. The Essential Guide to Doing Research. London, England: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glaser B, Holton J. Remodelling grounded theory. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2004;5(2):47–68. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centre for Oral Health Strategy NSW . Priority Oral Health Program and List Management Protocols. Sydney, Australia: NSW Ministry of Health; 2008. [Accessed May 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/oralhealth. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Australian Government Department of Human Services . Medicare Teen Dental Plan. Canberra BC, ACT, Australia: Australian Government Department of Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell S, Tickle M. How do we improve quality in primary dental care? Br Denl J. 2013;215(5):239–243. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brocklehurst P, Ferguson J, Taylor N, Tickle M. What is clinical leadership and why might it be important in dentistry? Br Dent J. 2013;214(5):243–246. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petersen PE. Priorities for research for oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Health. 2005;22(2):71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallerstein N. What Is the Evidence on Effectiveness of Empowerment to Improve Health? Copenhangen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Evidence Network report); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stillman-Lowe C. Oral Health Education: What Lessons Have We Learnt. 2009. [Accessed March 23, 2013]. Available from: https:www.adelaide.edu.au/oral-health-promotion/publications/journal/Oral%20Health%20Education.pdf.

- 48.Blinkhom AS. Dental health education: what lessons have we ignored? Br Dent J. 1998;184(2):58–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merijohn GK, Bader JD, Frantsve-Hawley J, Aravamudhan K. Clinical decision support chairside tools for evidence-based dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8(3):119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walsh LJ, Brostek AM. Minimim intervention dentistry principles and objectives. Aust Dent J. 2013;58(Suppl 1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/adj.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varkey P, Reller MK, Resar RK. Basics of quality improvement in health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(6):735–739. doi: 10.4065/82.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gillam S, Siriwardena AN. Frameworks for improvement: clinical audit, the plan-do-study-cycle and significant event audit. Qual Prim Care. 2013;21:123–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Interview questions to be explored with senior therapists.

Abbreviation: LHD, Local Health District.