Abstract

Background

Monoclonal antibodies may be used more effectively in combination. A previous study of intravenous (iv) bolus alemtuzumab plus rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) recurrence produced a response rate of 54% after a 4-week treatment period.

Methods

To optimize dose, schedule, and route of alemtuzumab, a study was designed exploring continuous intravenous infusion (civ) followed by subcutaneous (sc) alemtuzumab together with weekly iv rituximab in patients with previously treated CLL.

Results

Data from 40 patients with a median age of 59 years, and a median of 3 prior regimens (range, 1-8 regimens) were evaluable. Approximately 64% of patients were fludarabine-refractory. Seven patients (18%) achieved a complete response (CR), 4 (10%) a nodular partial response (nPR), and 10 (25%) a partial response for an overall response rate of 53%. Of 11 major responses (CR, nPR), 8 occurred after cycle 1. Response rates were highest in blood (94%), followed by liver/spleen (82%), bone marrow (68%), and lymph nodes (51%). The combination did not generate unexpected toxicities. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivations occurred in 6 patients (15%) and responded well to anti-CMV therapy. High titers of anti-idiotype antibodies after sc alemtuzumab were demonstrated in 1 patient, but remained without clinical sequelae.

Conclusions

The combination of civ/sc alemtuzumab plus rituximab has activity in some patients with recurrent/ refractory CLL and maximum response is achieved after 1 cycle (4 weeks) in 73% of patients. Further exploration in other settings of CLL together with accompanying pharmacokinetic studies is recommended.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, monoclonal antibodies, alemtuzumab, rituximab

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is the most prevalent adult leukemia in the Western hemisphere. Although traditionally considered of an indolent nature, recent clinical research highlighted a remarkable heterogeneity of its clinical course ranging from long-term survival without therapeutic intervention to fast-paced progression and early death.1 Therapy of CLL is nowadays frequently based on purine nucleoside-based combinations. However, none of the combinations cure CLL and prognosis remains poor in patients with recurrent and refractory disease. Ongoing efforts to identify effective therapies therefore remain important.2

We and others have previously demonstrated the feasibility and safety of the monoclonal antibody combination of alemtuzumab when given as an intravenous (iv) bolus infusion together with standard doses of iv rituximab for patients with recurrent and refractory CLL.3 The rationale was based on combining the therapeutic strengths of each of the components (eg, better activity of alemtuzumab in blood or bone marrow and of rituximab in lymph node sites) and thus benefit from the additive activity. Although response rates were encouraging and generated interest in using alemtuzumab plus rituximab combinations in other clinical settings such as frontline CLL and minimal residual disease (MRD), questions remained concerning the optimal dose, schedule, and route of alemtuzumab.4 We have combined iv rituximab with alemtuzumab starting as a 6-day continuous iv infusion (civ) and followed by subcutaneous (sc) injections thereafter. The goal was to 1) build up and maintain high levels of alemtuzumab in the plasma, 2) saturate soluble CD52 (sCD52) binding sites, and 3) improve patient tolerability.

Materials and Methods

Study Group

Patients aged ≥ 15 years with chronic lymphoid malignancies who were either refractory to frontline therapy or had developed disease recurrence after prior treatment, and whose malignant cell population expressed both CD20 and CD52 in ≥20% of the cells by either flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry were eligible. Expression of CD20 or CD52 in <20% of analyzed cells was permissible if patients received rituximab or alemtuzumab, respectively, not longer than 3 months before start of the study. Prior therapy with the combination of rituximab plus alemtuzumab was not allowed. Additional eligibility criteria included 1) performance status ≤2 (Eastern Oncology Cooperative Group [ECOG]), 2) adequate renal (serum creatinine ≤2 mg/dL) and hepatic function (total serum bilirubin ≤2 mg/dL), and 3) exclusion of patients with active hepatitis B and at high-risk of hepatitis B infection. All patients provided informed consent according to institutional guidelines. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and was conducted in accordance with the basic principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment Plan

Patients received rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m2 iv on Day 1, which was followed by a dose of 500 mg/m2 weekly on the first day of each treatment week (ie, Days 8, 15, and 22). Alemtuzumab was initiated as a civ over 24 hours at a dose of 30 mg/day for a total of 6 days (Days 2 to 7) followed by 30 mg sc twice a week on Days 3 and 5 of Weeks 2 to 4. Up to 3 courses could be administered. For patients receiving a second or third course, rituximab was continued at a dose of 500 mg/m2 weekly and alemtuzumab at a dose of 30 mg sc twice weekly on Days 3 and 5 without a repeat of the preceding 6-day civ phase. Treatment was administered in an outpatient setting. All patients received prophylactic trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and valacyclovir (or equivalent) for the duration of therapy and at least up to 3 months beyond the completion of the treatment. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia testing was performed within 14 days before therapy and after the completion of each cycle while the patient received treatment. Use of hematopoietic growth factors was permitted throughout therapy and was at the discretion of the treating physician.

All patients were assessed for toxicity and response. Definition of response followed criteria as defined according to the National Cancer Institute Working Group (NCI-WG) guidelines for CLL.5

Antiglobulin responses to alemtuzumab (anti-alemtuzumab antibodies) were measured in serum samples by sandwich enzyme-linked immunoadsorbent assay as previously described.6 Samples were collected within 60 days of the beginning of the study in patients with prior exposure to alemtuzumab and thereafter in all patients at the end of the first cycle and 4 to 6 weeks after the last cycle. All samples were processed and stored as specified by Bio-AnaLab Ltd. (Oxford, UK) and sent out in batches.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of the current study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of combining alemtuzumab when given as a civ followed by sc injections with rituximab. The primary measure of efficacy is the achievement of response, classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and nodular partial response (nPR) and determined according to established criteria.5

The trial was conducted in 2 stages and an interim analysis was conducted after the first 20 patients. The method of Bryant and Day was used to simultaneously consider efficacy and toxicity outcomes. Based on historical data, an unacceptable response probability was defined as 0.2, and an acceptable response probability as 0.4. Severe toxicities were defined as severe prolonged myelosuppression, severe infectious complications, or grade 4 infusion-related toxicities. A probability of severe toxicity of 0.4 was regarded as unacceptable, whereas a rate of 0.2 was acceptable for the regimen. Stopping boundaries for efficacy and toxicity were established accordingly. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize patient characteristics and response data. Time to treatment failure (time interval between the first treatment day to the first sign of disease progression) and survival (time interval between the first treatment until death from any cause) was estimated according to the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

Study Group

Forty-eight patients were enrolled, 40 of whom were evaluable for response and toxicity (Table 1). Of the 8 patients who were not evaluable, 1 patient withdrew consent after registration and before any therapy, 3 patients had to be taken off study after registration because they were found to be ineligible (because of prior treatment with the combination of alemtuzumab plus rituximab, lack of expression of CD20, and positive serum markers for hepatitis B virus, respectively), and 3 patients withdrew shortly after the initiation of treatment to continue therapy off protocol and outside The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. One patient had a diagnosis of marginal zone lymphoma/leukemia and has been excluded from this analysis.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics (N=40).

| Characteristic | Frequency No. (%) | Numerical Value |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 59 (42-78) | |

| Male | 30 (75) | |

| Median no. of prior therapies (range) | 3 (1-8) | |

| Prior fludarabine-based therapy | 36 (90) | |

| Fludarabine-refractory disease | 23 (64) | |

| Prior rituximab-based therapy | 40 (100) | |

| Prior alemtuzumab-based therapy | 4 (10) | |

| Median WBC count, ×109/L (range) | 15.9 (2-265) | |

| Median platelet count, ×109/L (range) | 111 (23-345) | |

| Median hemoglobin levels, g/dL (range) | 12 (8.5-16.3) | |

| Rai stage III and IV | 18 (45) | |

| β-2-microglobulin, mg/dL (range) | 3.9 (1.7-13.6) | |

| ZAP-70-positive | 5/7 (71) | |

| IgVH unmutated | 13/15 (87) | |

| Karyotype | ||

| 17p del | 1/23 (4) | |

| 11q del | 4/23 (17) | |

| + 12 | 2/23 (9) | |

| diploid | 12/23 (52) | |

| 13q del | 1/23 (4) |

WBC indicates white blood cell; IgVH, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable.

Response

Applying NCI-WG criteria for response assessment in CLL, 7 patients (18%) achieved a CR, 4 (10%) an nPR, and 10 patients (25%) achieved a PR, for an overall response (OR) rate of 53%. The 1 patient with deletion of chromosome 17p achieved a PR, but developed disease progression soon thereafter so that he had to be taken off study at the end of 2 cycles. Among the major responders (CR, nPR), 8 responses occurred after 1 cycle, whereas in 3 patients 2 cycles were necessary. Comparing characteristics of the 11 major responders with the 19 nonresponders demonstrated a higher number of male patients, a lower number of previous regimens, fewer patients who have previously received alemtuzumab, fewer patients with advanced Rai stage, and lower levels of β-2 microglobulin among the responders (Table 2). Thirteen patients were taken off study because of disease progression, including 1 patient with Richter transformation. No patient died while on study. Response by disease site is shown in Table 3. Response rates were highest in blood (94%), followed by liver/spleen (82%), bone marrow (68%), and lymph nodes (51%).

Table 2. Characteristics of Major Responders (CR/nPR).

| Characteristic | CR + nPR (N=11) | NR (N=19) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), y | 59 (47-78) | 59 (42-74) |

| Male, no. (%) | 10 (91) | 15 (79) |

| Median no. of prior regimens (range) | 1 (1-4) | 3 (1-8) |

| Fludarabine-refractory disease, no. (%) | 3 (30) | 14 (78) |

| Prior therapy with rituximab, no. (%) | 11 (100) | 19 (100) |

| Prior therapy with alemtuzumab, no. (%) | 1 (9) | 3 (16) |

| Rai stage III and IV, no. (%) | 3 (27) | 13 (68) |

| Median β-2-microglobulin, mg/dL (range) | 2.5 (1.7-5.4) | 5.3 (2.4-9.5) |

CR indicates complete response; nPR, nodular partial response; NR, no response.

Table 3. Response by Disease Site.

| Disease Site | No. | CR No. (%) | nPR No. (%) | PR No. (%) | OR No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 32 | 30 (94) | NA | 0 | 30 (94) |

| Bone marrow | 40 | 13 (33) | 11 (27) | 3 (7) | 27 (68) |

| Lymph nodes | 33 | 13 (39) | NA | 4 (12) | 17 (51) |

| Liver/spleen | 11 | 8 (73) | NA | 1 (9) | 9 (82) |

No. indicates the number of evaluable patients in a particular disease site; CR, complete response; nPR, nodular partial response; PR, partial response; OR, overall response; NA, not applicable.

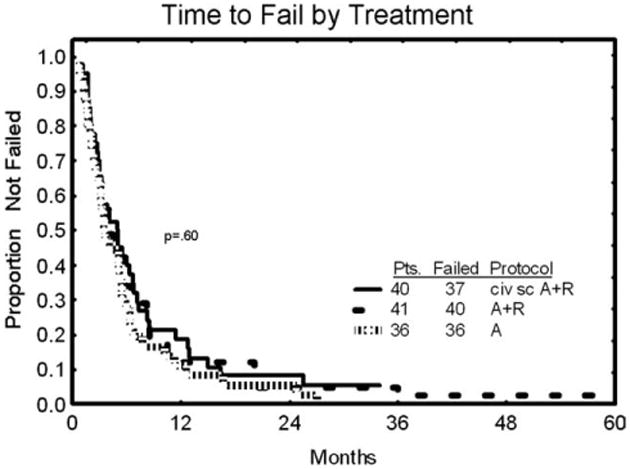

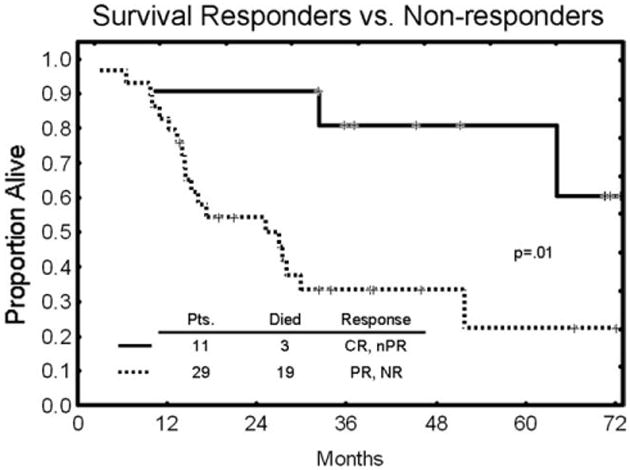

Time to treatment failure is shown in Figure 1. The results are compared with a historical control of 36 patients with similar characteristics who received single-agent alemtuzumab on another treatment protocol and 41 patients from the previous combination study of alemtuzumab (iv) plus rituximab. The median time to treatment failure was 6 months (range, 1-34 months) for civ followed by sc alemtuzumab plus rituximab and was virtually identical with both historical control groups (P = .60). Overall survival of the major responders (patients with CR and nPR) compared with the remainder of the patients is shown in Figure 2. The median overall survival was longer in the major responder group (62 months [range, 1-73 months]) than for patients with a PR or no responses (28 months [range, 1-72 months]; (P = .01).

Figure 1.

Time to treatment failure is shown comparing continuous intravenous infusion (civ) alemtuzumab/subcutaneous (sc) alemtuzumab with 2 historical control groups: 1) patients (Pts) treated with single-agent alemtuzumab and 2) those treated with intravenous alemtuzumab plus rituximab (A/R).

Figure 2.

Overall survival comparing patients (Pts) with major responses (complete response [CR] and nodular partial response [nPR]) and patients with a partial response [PR] or no response (NR).

Toxicities and Infectious Complications

Adverse events were generally less than grade 3 and manageable with supportive care. Most frequent were fever (28 patients; 68%), chills (25 patients; 61%), fatigue (21 patients; 51%), skin rashes (11 patients; 27%), nausea (10 patients; 24%), myalgias (10 patients; 24%), and diarrhea (4 patients; 10%). They occurred mostly at the beginning of the infusion part of the alemtuzumab administration, but quickly subsided within a few days and did not recur once patients moved on to the sc injections. One patient developed autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). This patient was heavily pretreated, had Rai stage 4 disease at the time of treatment initiation, failed to respond to therapy, and was taken off after 1 cycle.

Documented infectious episodes occurred in 11 patients (28%). Included among these are bronchitis (Staphylococcus aureus) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in 1 patient each, upper respiratory tract infections without cultured organisms in 2 patients, a Pseudomonas skin infection in 1 patient, and 6 patients (15%) with CMV infections. All CMV infections were detected by antigenemia testing in blood samples of symptomatic patients, and none had organ manifestations such as pneumonia or hepatitis. All patients recovered with appropriate anti-CMV therapy.

Measurement of Antiglobulin Responses

Samples from 40 evaluable patients were analyzed for antiglobulin response (in 1 case a tube without sample was sent). One patient (UPN 34) had a very high titer response reaching 13,100 U/mL (level of detection ≥444 U/mL) 1 day before therapy with alemtuzumab, which was maintained at 12,500 U/mL at the end of therapy (1 cycle). In 2 additional patients (UPN 39 and 42), low-positive titers (572 U/mL and 454 U/mL, respectively) were recorded in pretreatment samples, which turned negative during therapy (ie, < 444 U/mL). None of the 3 patients had previously received alemtuzumab, and no unusual adverse events occurred in any of these patients while on study. At the time of last follow-up, Patients UPN 34 and 39 had achieved a PR, whereas patient UPN 42 had no response to therapy.

Discussion

Monoclonal antibodies play a dominant role in the therapy of most patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, including CLL. Combinations of nucleoside analog-based chemotherapy with monoclonal antibodies (chemoimmunotherapy) have been highly active in CLL. Two recent, large randomized trials have demonstrated that chemoimmunotherapy results in superior response rates and progression-free survival over chemotherapy alone.7,8 Alemtuzumab, a humanized immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 monoclonal antibody targeting the human CD52 antigen, has been approved for use in patients with CLL based on 2 clinical studies in patients with refractory disease and frontline patients, respectively.9,10 Monoclonal antibodies directed against other target antigens have also demonstrated activity, most notably the anti-CD20–specific monoclonal antibody rituximab.11 In a previous study, we combined alemtuzumab with rituximab with the following rationale3: 1) responses after single-agent monoclonal antibody therapy are not durable and 2) the activities of alemtuzumab and rituximab may complement each other. Alemtuzumab can effectively clear blood and bone marrow lymphocytosis, whereas rituximab is effective at reducing lymphadenopathy. Furthermore, alemtuzumab demonstrated activity in patients with 17p deletions and/or p53 mutations, both of which have been associated with resistance to most other available CLL treatment agents.12 The combination achieved an OR rate of 54% in patients with recurrent and refractory disease, but questions remained regarding the optimal dose and schedule of the combination.

Administering alemtuzumab as a continuous infusion at the initiation of the treatment was aimed at rapidly achieving high circulating antibody levels to saturate soluble CD52 binding sites.13 Subsequent dosing should then allow maximum binding of alemtuzumab to cell-bound (malignant lymphocytes, lymph nodes) CD52 and so enhance its antitumor effect. We have recently published results of a pilot study in which alemtuzumab was given identically to the current study, but without rituximab.4 Two of 10 patients with fludarabine-refractory disease achieved PR. Alemtuzumab plasma levels were measured in 4 patients, 3 of whom demonstrated peak levels within 24 hours, which were sustained for at least 3 weeks. The sc alemtuzumab is today more widely used in clinical practice than the iv formulation. In addition to the ease of administration, its main advantage is the noticeably lower incidence and severity of adverse events compared with iv administration. Equally important is the question of whether sc and iv routes achieve the same alemtuzumab plasma levels, as blood concentrations have been correlated with response. This is indeed the case as demonstrated in a study from 2004.6 Highest measured blood concentrations in 50 patients with CLL were similar after iv or sc alemtuzumab, although the cumulative dose to reach a defined level in the blood was higher with sc administration.

In the current study, we reported an OR rate of 53%, including 18% complete responders. In a comparison with the previous combination study, the OR rate and time to treatment failure were similar, although there appears to be a trend toward a higher CR rate (Table 4).3 However, subtle differences in the patient populations between this and the previous alemtuzumab/rituximab study may have influenced this comparison (eg, median β-2 microglobulin levels were slightly higher in the previous study). The toxicity profile even during the civ phase of alemtuzumab was more favorable without any new or unexpected toxicities. We only reported 1 patient with significant levels of alemtuzumab anti-idiotype antibodies, but no clinically apparent consequences. The levels were detected before treatment and then persisted at least for the duration of follow-up. In the study by Hale et al, 2 of 32 patients who were treated with sc alemtuzumab developed clinically significant anti-idiotype responses. None of the patients responded to therapy, and in both cases, an exaggerated skin reaction was observed at the alemtuzumab injection site. In their study, anti-idiotype responses were detected up to 50 months after the treatment, whereas our measurements only extended to a few weeks after therapy.

Table 4. Comparison of Responses.

| civ → sc A + R | iv A + R | iv Aa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 40 | 48 | 48 |

| CR (%) | 7 (18) | 4 (8) | 2 (5) |

| nPR (%) | 4 (10) | 2 (4) | – |

| PR (%) | 10 (25) | 19 (40) | 12 (29) |

| OR (%) | 21 (53) | 25 (52) | 14 (34) |

| Early death (%) | – | – | 5 (12) |

civ indicates continuous intravenous infusion; sc, subcutaneous; A, alemtuzumab; R, rituximab; iv, intravenous; CR, complete response; nPR, nodular partial response; PR, partial response; OR, overall response.

Data regarding iv A are from a historical control group of patients with similar characteristics as current study group.

Although it has been a few years since we first published results of the combination of alemtuzumab plus rituximab in patients with CLL recurrence, interest in the combination persists and extends into other groups of patients. Frankfurt et al reported on 20 previously untreated and symptomatic patients with CLL who received alemtuzumab with rituximab administered sc.14 The median age of the group was 54 years. Approximately 75% achieved a CR, including all 5 patients with an 11q-abnormality. Furthermore, at the completion of therapy, 14 patients (70%) had no evidence of MRD by flow cytometry. Zent et al used the combination in untreated, but asymptomatic, patients with CLL who had at least 1 marker of high-risk disease (17p13-, 11q22-, or combination of unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable and CD38+/ZAP70+).15 Twenty-seven (90%) patients responded, with CRs occurring in 11 patients (37%) and 5 of the CR patients without MRD. Further development of the combination includes induction therapy for elderly patients and for the treatment of MRD. Validation of our hypothesis of neutralizing soluble CD52 antigen and optimization of binding to the tumor target would help to substantiate the clinical experience that the current study achieved higher complete remission rates in patients with disease recurrence than the previous dose and schedule.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest Disclosures: The authors made no disclosures.

References

- 1.Dighiero G, Hamblin TJ. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60456-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien S. New agents in the treatment of CLL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:457–464. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faderl S, Thomas DA, O'Brien S, et al. Experience with alemtuzumab plus rituximab in patients with relapsed and refractory lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2003;101:3413–3415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrajoli A, Wierda W, LaPushin R, et al. Pilot experience with continuous infusion alemtuzumab in patients with fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:296–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, et al. National Cancer Institute-Sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood. 1996;87:4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hale G, Rebello P, Brettman LR, et al. Blood concentrations of alemtuzumab and antiglobulin responses in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia following intravenous or subcutaneous routes of administration. Blood. 2004;104:948–955. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallek M, Fingerle-Rowson G, Fink AM, et al. Immunochemotherapy with fludarabine (F), cyclophosphamide (C), and rituximab (R) (FCR) versus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) improves response rates and progression-free survival (PFS) of previously untreated patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemoa (CLL) Blood. 2008;112:125. abstract. Abstract 325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robak T, Moiseev SI, Dmoszynska A, et al. Rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (R-FC) prolongs progression free survival in relapsed or refractory chronic lymphoyctic leukemia (CLL) compared with FC alone: final results from the International Randomized Phase III REACH Trial. Blood. 2008;112:LBA-1. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keating MJ, Flinn I, Jain V, et al. Therapeutic role of alemtuzuamb (Campath-1H) in patients who have failed fludarabine: results of a large international study. Blood. 2002;99:3554–3561. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillmen P, Skotnicki AB, Robak T, et al. Alemtuzumab compared with chlorambucil as first-line therapy for chronic lymphoyctic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5616–5623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien SM, Kantarjian H, Thomas DA, et al. Rituximab dose-escalation trial in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2165–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lozanski G, Heerema NA, Flinn IW, et al. Alemtuzumab is an effective therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with p53 mutations and deletions. Blood. 2004;103:3278–3281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albitar M, Do KA, Johnson MM, et al. Free circulating soluble CD52 as a tumor marker in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and its implications in therapy with anti-CD52 antibodies. Cancer. 2004;101:999–1008. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankfurt O, Hamilton E, Duffey S, et al. Alemtuzumab and rituximab combination therapy for patients with untreated CLL-a phase II trial. Blood. 2008;112:730. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zent CS, Call TG, Shanafeldt TD, et al. Early treatment of high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia with alemtuzumab and rituximab. Cancer. 2008;113:2110–2118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]