Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is characterized by low pulmonary function, inflammation, free-radical production, vascular dysfunction and subsequently a greater incidence of cardiovascular disease. By administering an acute oral antioxidant cocktail to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=30) and controls (n=30), we sought to determine the role of redox balance in the vascular dysfunction of these patients. Using a double blind, randomized, placebo controlled, crossover design, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and controls ingested placebo or the antioxidant cocktail (Vitamin-C, Vitamin-E, α-lipoic acid) after which brachial artery flow mediated dilation and carotid-radial pulse wave velocity were assessed using ultrasound Doppler. The patients exhibited lower baseline antioxidant levels (Vitamin-C and superoxide dismutase activity) and higher levels of oxidative stress (Thiobarbituic acid reactive species) in comparison to controls. The patients also displayed lower basal flow mediated dilation (p<0.05), which was significantly improved with antioxidant cocktail (3.1±0.5 vs. 4.7±0.6 %, p<0.05, placebo vs. antioxidant cocktail), but not controls (6.7±0.6 vs. 6.9±0.7 %, p>0.05, placebo vs. antioxidant cocktail). The antioxidant cocktail also improved pulse wave velocity in the patients (14±1 vs. 11±1 m·s−1, p<0.05, placebo vs. antioxidant cocktail), while not affecting controls (11±2 vs. 10±1 m·s−1, p>0.05, placebo vs. antioxidant). Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exhibit vascular dysfunction, likely mediated by an altered redox balance, which can be acutely mitigated by an oral antioxidant. Therefore, free radically-mediated vascular dysfunction may be an important mechanism contributing to this population’s greater risk and incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: COPD, free radicals, oxidative stress, endothelial function, vascular stiffness

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a condition that originates in the pulmonary system, but is now well recognized to manifest as a syndrome, encompassing other symptomology and co-morbidities beyond pulmonary disease, most of which appear to be vascular related 1–6. Specifically, an increased incidence of hypertension, advanced atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease (CAD), peripheral vascular disease, and elevated cardiovascular mortality are now often considered hallmarks of COPD 4–8. However, the mechanistic link between COPD, vascular dysfunction, and cardiovascular disease remains to be elucidated.

Vascular endothelial function has been documented to be related to both cardiovascular disease risk 9–11 and incidence 12, 13. Consequently, assessments of flow mediated dilation (FMD), a measure of vascular endothelial function, and pulse wave velocity (PWV), a measure of vascular stiffness, have grown in popularity as independent predictors of cardiovascular disease risk 14–16. Utilizing the FMD technique, prior studies have demonstrated that patients with COPD display reduced vascular function compared to age matched controls 17–19. Similarly, studies have revealed that patients with COPD exhibit significantly elevated vascular stiffness as assessed by PWV 20–22. Additionally, there is a growing hypothesis that pulmonary vascular dysfunction itself may be a key factor that instigates the development of COPD 23–25 and as a consequence systemic vascular dysfunction follows 26, although the nature of this relationship is currently not well understood 27.

Chronic inflammation associated with COPD 4, 20, 28–31 may be the instigator of, and related to, the peripheral vascular dysfunction associated with this population 18. However, the downstream effects of this inflammation 32, and the subsequent role of free radicals in disrupting vascular function in these patients has received little attention. To date, we are unaware of a single study that has aimed to reduce free radicals in patients with COPD to determine if this can improve vascular function, thus providing a mechanistic link between oxidative stress and the elevated cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, incidence and mortality in this population 3.

Previously it has been documented that an acute antioxidant cocktail (AOC) of known efficacy 33, 34 is capable of improving vascular function, as assessed by FMD, in the elderly population 33 and heart transplant recipients with history of heart failure 35, populations with increased CVD risk and a definitive incident, respectively. The AOC-induced improvement in redox balance 36 likely attenuates free radical mediated reductions in nitric oxide bioavailability, thus increasing endothelial dependent flow mediated dilation 33–35. These previous studies highlight the role of free radicals in mediating vascular dysfunction in vulnerable populations and that the AOC-induced improvements in vascular function were mediated by an improvement in redox balance.

Accordingly, by acutely administering an AOC to patients with COPD we sought to determine the role of redox balance in vascular dysfunction (FMD and PWV) in patients with COPD. Specifically, we employed FMD and PWV to assess vascular endothelial function and stiffness after acute ingestion of an oral AOC or placebo in patients with COPD and age matched controls. We hypothesized that the AOC would improve FMD and reduce PWV in COPD patients, but not controls, highlighting the role of redox balance in vascular dysfunction in this patient population.

METHODS

Subjects and General Procedures

Sixty volunteers were recruited for this study, 30 patients with COPD and 30 age and sex matched controls (Table 1). Although the majority of patients with COPD had a significant or recent history of smoking (months since quitting: 96 ± 33), current smokers were excluded, as acute smoke inhalation is capable of altering endothelial function37. A single control subject reported a history of smoking, but quit 240 months prior to the study. In accordance with recent guidelines 38, the inclusion criterion for patients with COPD was a pulmonary function test that was performed post-bronchodilator indicating an FEV1.0/FVC ratio < 0.70. Additionally, none of the patients with COPD reported a recent exacerbation (<3 months, Table 2) and were stable, in terms of symptom severity, during both visits. Subject characteristics, such as prevalence of CAD and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), unless otherwise indicated, were determined from health histories. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Utah and the SLC VAMC. Written informed consent was obtained from each subject before participation in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with COPD and Controls

| Characteristic | units | Control (n = 30) | COPD (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | yrs | 66 ± 2 | 66 ± 2 |

| Female/Male | n | 15/15 | 15/15 |

| Height | cm | 169 ± 2 | 166 ± 2 |

| Weight | kg | 74 ± 3 | 73 ± 4 |

| BMI | kg/m2 | 25 ± 1 | 26 ± 1 |

| SBP | mmHg | 129 ± 3 | 136 ± 4 |

| DBP | mmHg | 79 ± 1 | 80 ± 2 |

| FEV1.0 | L | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 * |

| FEV1.0 | % Predicted | 107 ± 4 | 55 ± 4 * |

| FVC | L | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.2 * |

| FEV1.0/FVC Ratio | % | 76 ± 1 | 45 ± 3 * |

| GOLD Classification | (n/group) | ||

| 1 “Mild” | - | 3 | |

| 2 “Moderate” | - | 13 | |

| 3 “Severe” | - | 8 | |

| 4 “Very Severe” | - | 6 | |

| Creatinine | mg/dL | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| Urea Nitrogen | mg/dL | 16.3 ± 0.6 | 16 ± 1.2 |

| Glucose | mg/dL | 85 ± 3.8 | 87 ± 3.2 |

| Cholesterol | mg/dL | 198 ± 10 | 195 ± 11 |

| HDL-cholesterol | mg/dL | 51 ± 3.2 | 57 ± 4.1 |

| LDL-cholesterol | mg/dL | 128 ± 8 | 121 ± 9 |

| Triglycerides | mg/dL | 144 ± 19 | 110 ± 12 |

| Erythrocytes | M/uL | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| Hemoglobin | g/dL | 15.2 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 0.5 |

| Hematocrit | % | 45 ± 0.7 | 47 ± 1.5 |

| Leukocytes | K/uL | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 0.6 * |

| Neutrophils | K/uL | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.5 * |

| Lymphocytes | K/uL | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| Monocytes | K/uL | 0.5 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.0 * |

| Eosinophils | K/uL | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| Basophils | K/uL | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

Mean ±SE;

p < 0.05 control vs. COPD

Table 2.

Subject History of Controls (n = 30) and Patients with COPD (n = 30)

| History | Control (# of cases) | COPD (# of cases) |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 7 | 17 * |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 7 | 6 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0 | 0 |

| Diabetes | 1 | 0 |

| Hypothyroid | 2 | 3 |

| Chronic Heart Failure | 1 | 2 |

| Anemia | 0 | 2 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 1 | 2 |

| Self-Reported Tobacco Smoking History | 1 | 26 * |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 1 | 2 |

| Exacerbation in last 3mo req Hospitalization | 0 | 0 |

| Exacerbation in last 6mo req Corticosteroids | 0 | 3 |

| Prescribed Supplemental Oxygen | 0 | 7 |

| Taking Supplemental Oxygen | 0 | 7 |

| Medications

| ||

| Pulmonary | ||

| Short acting Anticholinergic Bronchodilators | 0 | 5 * |

| Long acting Anticholinergic Bronchodilators | 0 | 7 * |

| Long acting β2-agonist | 1 | 14 * |

| Corticosteroids | 0 | 11 * |

| Cardiovascular | ||

| Calcium Channel Inhibitor | 2 | 9 * |

| Antiarrhythimc | 1 | 1 |

| Thiazide Diruetic | 2 | 4 |

| ACE inhibitor | 2 | 10 * |

| Angiotensin Receptor Blocker | 1 | 2 |

| β-blocker | 2 | 4 |

| Statin | 6 | 5 |

| Anticoagulant | 0 | 1 |

(n = 30 Controls, and n = 30 patients with COPD)

p < 0.05 control vs. patients with COPD

All subjects reported to the laboratory twice within one week (>48 h apart) after ingesting either placebo or the AOC in a balanced, double blind, crossover design. The standardized AOC, taken in the same manner, by all subjects was composed of 2 separate doses of Vitamin C, Vitamin E, and alpha-lipoic acid 33, which has previously been documented to reduce plasma free radicals as measured by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy 34, 39. The first AOC dose (300 mg alpha lipoic acid, 500 mg Vitamin C, 200 IU of Vitamin E) was taken 90 min prior to testing, while the second AOC dose (300 mg alpha lipoic acid, 500 mg Vitamin C, 400 IU of Vitamin E) was taken 60 min prior to testing. These doses and the dosing paradigm were chosen based upon both practicality (doses found in “over the counter” formulations) and efficacy, as assessed by a reduction in the free radical EPR signal 34, 39. Placebo microcrystalline cellulose capsules of similar taste, color, and appearance were likewise consumed in the same manner as the AOC trial. Subjects reported to the laboratory in a fasted state and without caffeine or alcohol use for 12 and 24 h, respectively. They also had not performed any exercise within the past 24 h. Upon arrival a venous blood sample was obtained for blood chemistry (electrolytes, creatinine, glucose, etc.), lipid panel, complete blood count (CBC), and biochemical assays (markers of antioxidant capacity and oxidative stress). Following this blood draw, subjects were positioned supine and rested quietly for 20 min prior to PWV and FMD testing.

Brachial Artery Flow-Mediated Dilation (FMD) and Reactive Hyperemia (RH)

The FMD was performed in accordance with recent guidelines 40. Briefly, after baseline measurements of brachial artery diameter and blood velocity were performed, a blood pressure cuff was inflated to a suprasystolic pressure for 5 min. Upon cuff release, measurements were assessed continuously for 2 min. During baseline and cuff release, images were sent in real-time to off-line software and later analyzed using automated edge detection. These analyses were performed by a trained technician who was blinded to both subject group and condition. FMD, was quantified as the peak diameter observed post occlusion and expressed as percent change from baseline (%). RH was quantified as the cumulative area under the curve for brachial artery blood flow during the entire 2 min post occlusion period.

Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV)

Concurrent pilot work in a separate study revealed a positive effect of the AOC on PWV in patients with COPD, therefore, due to the timing of this observation, this measurement was only performed in patients with COPD (n=17) and age and sex matched controls (n=17) during the latter portion of the current study. Prior to the FMD test, Ultrasound Doppler measurements were taken at the carotid and radial arteries to assess peripheral arterial stiffness (carotid-radial pulse wave velocity; c-rPWV), an approach previously utilized in this population 22 and has been documented to detect elevations in PWV in populations with heightened CVD risk 41, 42. Additionally, in young healthy individuals we have found that carotid-radial and carotid-femoral PWV are significantly related, and c-rPWV is therefore a predictor of carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (r = 0.5, unpublished observations). Pulse wave velocity was calculated using the foot-to-foot ECG gated method as described previously 43, 44, and expressed as meters per second (m·s−1).

Data Analysis

Area under the curve for shear rate and reactive hyperemia were calculated using the trapezoidal rule for the 2 min following cuff deflation. Statistical comparisons were performed using two way analysis of variance, analysis of covariance, t-tests, and chi square where appropriate. The level of significance was established at 0.05. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

The subject characteristics and medical history are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The subjects were well matched, aside from the typical greater incidence of hypertension in the patients with COPD, compared to controls. Of note, as there was no difference in vascular function (FMD) between the patients with COPD who had a history of hypertension and those who did not (p =0.56), the patients were not divided into two groups based on this characteristic. There were no sex differences with regards to basal vascular function (FMD or PWV) in either group, or in response to the antioxidant cocktail, therefore, the data for both sexes were combined.

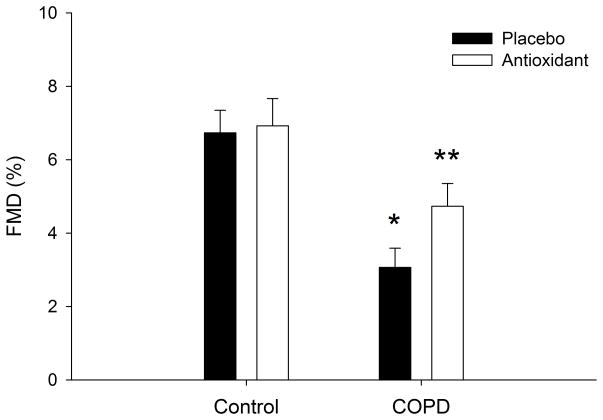

FMD and Reactive Hyperemia

In the placebo condition patients with COPD displayed significantly lower FMD compared to controls (3.1 ± 0.5 vs. 6.7 ± 0.6 %, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control, Figure 1). Flow mediated dilation was significantly improved with the AOC in the COPD patients (3.1 ± 0.5 vs. 4.7 ± 0.6 %, p < 0.05, placebo vs. AOC), but not controls (6.7 ± 0.6 vs. 6.9 ± 0.7 %, p > 0.05, placebo vs. AOC) (Figure 1). These results also held true when expressed as absolute change in brachial artery diameter, confirming a lower FMD in patients with COPD under placebo condition (0.01 ± 0.002 vs. 0.03 ± 0.003 cmΔ, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control) which was improved by ingestion of the AOC in the patients (0.01 ± 0.002 vs. 0.02 ± 0.003 cmΔ, p < 0.05, placebo vs. AOC) and not controls (0.03 ± 0.003 vs. 0.03 ± 0.004 cmΔ, p > 0.05, placebo vs. AOC). Shear rate, area under the curve (AUC), was not different between patients with COPD and controls (28776 ± 3305 vs. 31563 ± 2797 s−1, p > 0.05, COPD vs. control) and the AOC had no significant effect on shear rate in either group (COPD: 31308 ± 3586, Control: 31902 ± 3034 s−1, p > 0.05). Similarly, reactive hyperemia, AUC, was not different between groups (516 ± 68 vs. 590 ± 65 mL, p > 0.05, COPD vs. control, respectively) and the AOC had no effect on the RH (AUC) in either group (564 ± 75 vs. 582 ± 68 mL, p > 0.05, COPD vs. control, respectively).

Figure 1. Flow mediated dilation (FMD), expressed as peak relative change in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) as well as age and sex matched controls under placebo and antioxidant conditions.

*p < 0.05 COPD vs. control placebo condition, ** p < 0.05 placebo vs. antioxidant in COPD only.

To account for potential individual differences in shear rate and thus the stimulus for FMD, the FMD data were normalized for the shear stimulus (FMD/shear rate, AUC). COPD patients again exhibited reduced vascular function (0.12 ± 0.03 vs. 0.25 ± 0.03 FMD/shear rate, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control), which was significantly improved following acute ingestion of the oral AOC in the COPD patients (p < 0.05), but not controls (0.26±0.06 vs. 0.28±0.04 FMD/shear rate, p > 0.05, COPD vs. control). Time to peak vasodilation did not differ between control and COPD patients and was unaffected by the AOC in both groups.

Post hoc analysis of the subject characteristics revealed a significantly greater incidence of hypertension in the patients with COPD. With the potential that this specific comorbidity in the patients with COPD could have influenced their vascular function, the data were re-analyzed in three different ways to determine if hypertension, per se, played a role. The first approach, in addition to age and sex matching, the groups were matched for incidence of hypertension (dropping 10 hypertensives in the COPD group and 10 non-hypertensives in the healthy group leaving n=7 hypertensives in each group of 20 subjects (Beta still >0.8 for all major variables). This approach yielded the same initial result where patients with COPD exhibited significantly reduced FMD compared to controls (absolute (0.009±0.002 vs. 0.03±0.002 cmΔ), relative (2.6±0.6 vs. 7.7±0.8 %FMD), or normalized to shear rate (0.1063±0.03 vs. 0.3005±0.05 s−1), all p < 0.05), which was improved following the AOC in the COPD group only, abolishing the difference between the two groups. The second approach, filtering out all subjects with hypertension leaving 13 patients with COPD and 23 age matched controls with no incidence of hypertension, resulted in the same findings: A significantly blunted FMD (absolute (0.0107±0.002 vs. 0.0283±0.003 cmΔ), relative (2.6±0.6 vs. 6.6±0.7 %FMD), or normalized to shear rate (0.09±0.02 vs. 0.21±0.03 s−1), all p < 0.05), in the patients with COPD compared to the healthy controls. The third approach, utilizing an ANCOVA with hypertensive status as a covariate and all subjects included (n=60), revealed that the contribution of hypertensive status to basal FMD was not significant (partial eta square = 0.013, p = 0.40. Regardless of which approach/group of patients with COPD was examined there was not a statistically significant relationship between the indices of COPD severity (GOLD classification, FEV1/FVC ratio, %predicted FEV1, etc.) and AOC-induced vascular function improvement.

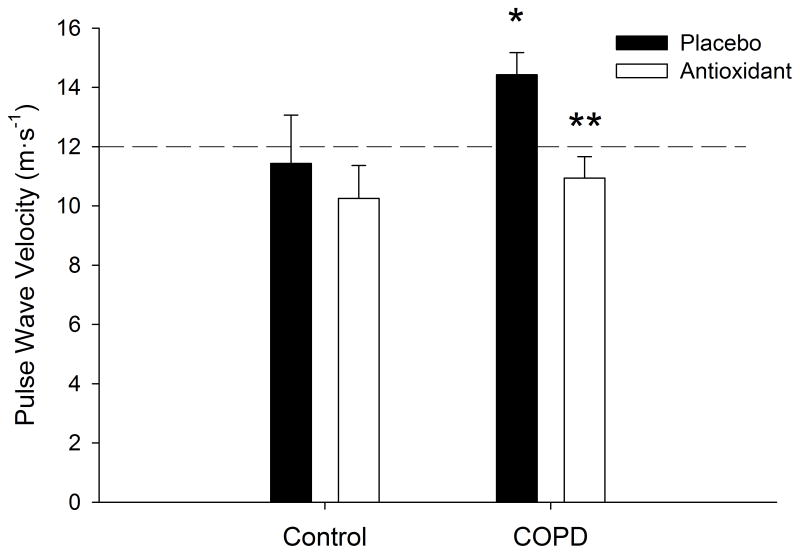

Pulse Wave Velocity (PWV)

In the placebo condition, COPD patients exhibited significantly higher PWV (14 ± 1 vs. 11 ± 2 m·s−1, p < 0.05, COPD vs. controls, respectively) (Figure 2). The AOC significantly reduced PWV in COPD patients (14 ± 1 vs. 11 ± 1 m·s−1, p < 0.05, control vs. AOC, respectively), but not in controls (11 ± 2 vs. 10 ± 1 m·s−1, p > 0.05, control vs. AOC, respectively).

Figure 2. Carotid-Radial Pulse Wave Velocity, under placebo and antioxidant conditions in both patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), as well as age and sex matched controls.

*p < 0.05 COPD vs. control placebo condition, ** p < 0.05 placebo vs. antioxidant in COPD only. Dashed line indicates the recommended 12 m·s−1 cutoff, as established by the “Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness Collaboration”, indicating elevated risk for cardiovascular disease 49.

Blood Assays

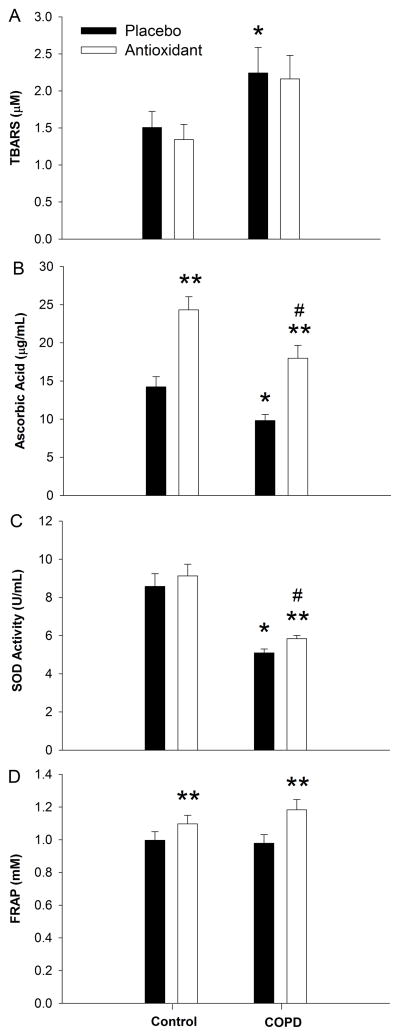

Analysis of the patients’ blood revealed lower initial levels of Vitamin C (10 ± 1 vs. 14 ± 1 ug/mL, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control), while both groups plasma levels were significantly (p < 0.05, placebo vs. AOC) increased following the AOC, the patients with COPD still exhibited lower levels of Vitamin C even after ingestion of the AOC (18 ± 2 vs. 24 ± 2 ug/mL, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control) (Figure 3). Global antioxidant capacity assessed using the FRAP was similar at baseline (1.0 ± 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.05 mM, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control), and was significantly (p < 0.05, placebo vs. AOC) increased in both groups following the AOC (1.2 ± 0.06 vs. 1.1 ± 0.05 mM, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control, respectively) (Figure 3). Superoxide dismutase activity was lower in patients at baseline (5.1 ± 0.2 vs. 8.6 ± 0.7 U/mL, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control) and only significantly increased in the patients with COPD following AOC ingestion (p < 0.05). Despite this AOC-induced increase, SOD activity remained lower in the patients, as compared to controls (5.8 ± 0.2 vs. 9.1 ± 0.6 U/mL, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control) (Figure 3). Oxidative stress as assessed by TBARS (an index of lipid peroxidation), was significantly higher in the patients with COPD (2.2 ± 0.3 vs. 1.5 ± 0.2 uM, p < 0.05, COPD vs. control) and was unchanged (p > 0.05) in either group following the AOC (2.2 ± 0.2 vs. 1.3 ± 0.2 uM, p > 0.05, COPD vs. control) (Figure 3). In a subset of the patients with COPD (n=16), free radical levels, directly assessed by EPR spectroscopy, was significantly reduced following the AOC (8.5 ± 2 vs. 3.8 ± 1 AU, p < 0.05, placebo vs. AOC). Regarding inflammation, the complete blood count obtained during the placebo trial revealed significantly elevated leukocytes (7.4 ± 0.6 vs. 5.6 ± 0.3 K/uL), neutrophils (4.8 ± 0.5 vs. 3.4 ± 0.3 K/uL), and monocytes (0.58 ± 0.04 vs. 0.46 ± 0.03 K/uL) in the COPD patients compared to controls. However, while statistically different, these elevated values were still within the normal range (Table 1).

Figure 3. Oxidative stress (Panel A) and antioxidant (Panel B–D) assessments, under placebo and antioxidant conditions in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) as well as age and sex matched controls.

* p < 0.05 control vs. COPD placebo condition, **p < 0.05, within group, # p < 0.05 control vs. COPD antioxidant condition.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine the role of redox balance in the vascular dysfunction associated with COPD. Patients with COPD did, indeed, display impaired vascular function, as assessed by FMD and PWV, when compared to age matched controls. Blood analyses revealed greater basal oxidative stress (TBARS) and lower endogenous antioxidant capacity (ascorbic acid and SOD) in the patients with COPD compared to controls. After AOC ingestion both groups displayed a similar increase in plasma ascorbic acid and total antioxidant capacity, indicating an equivalent initial effect of the AOC. Under these conditions, the differences in FMD and PWV between the patients with COPD and controls were mitigated. Therefore, collectively, these data reveal that patients with COPD exhibit an altered redox balance which appears to negatively impact vascular function and stiffness, likely predisposing this patient population to greater risk and incidence of cardiovascular disease.

Baseline Vascular Dysfunction in Patients with COPD

In agreement with prior work 18, using current methodologies for the assessment of flow mediated dilation 40 this study has demonstrated that patients with COPD are characterized by reduced vascular function, which is likely specific to the endothelium. In support of this contention, although not assessed in the current study, others have determined that there was no difference between controls and patients with COPD in terms of endothelium independent dilation using sublingual nitroglycerin 17 or intra-arterial infusion of sodium nitroprusside and verapamil 20. However, it is also important to note that not all agree that impaired endothelium dependent dilation is an obligatory component of COPD 20, and may actually depend upon exacerbation status 17. Interestingly, another vascular assessment performed in the current study, reactive hyperemia (RH), was not different between patients with COPD and controls, or as a result of ingestion of the AOC. RH, which reflect microvascular responsiveness, seems to be mediated through both endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms 45, but also appears to be predictive of CV events 46. Thus, a differential response between conduit artery (FMD) and microvascular function (RH), is not surprising, and is in agreement with prior work 17, 18 suggesting that RH alone may not be as sensitive as FMD. However, as RH plays an important role as a component of shear rate, the stimulus for FMD 47, 48, normalizing FMD for the increase in the shear rate, evoked by cuff occlusion and release, can be an important consideration. Although normalizing FMD to shear rate had no effect upon the interpretation of the current findings.

In support of the current FMD data, revealing attenuated vascular function in the patients with COPD, the pulse wave velocity assessment independently revealed significantly higher carotid-radial PWV in these patients when compared to controls in the placebo condition. Of note, placebo PWV in the patients was above the recommended 12 m·s−1 as established by the “Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness Collaboration”, indicating elevated risk for CVD 49, which was significantly reduced following acute AOC ingestion. While PWV is traditionally thought of as purely an estimate of vascular stiffness, more recent evidence suggests that PWV may be related to endothelial function 50–52, which may explain the AOC-mediated reduction in PWV. Taken together, reduced FMD and elevated PWV provide significant evidence of vascular dysfunction in patients with COPD which likely contributes to the elevated CVD risk and prevalence in this population 4–8.

Mechanisms of Vascular Dysfunction in Patients with COPD

According to the current findings, the mechanisms responsible for vascular dysfunction in the patients with COPD, appear to be partly mediated by an alteration in the redox balance by an attenuated antioxidant capacity and/or elevated oxidative stress, as the oral AOC improved vascular function only in the those with COPD. Interestingly, in contrast to our prior work focused upon aging, where the elderly exhibited a significant improvement in FMD following the ingestion of the AOC 33, the relatively old subjects in the current study were not affected by the AOC. However, it is important to note that, the control group for the patients with COPD were, on average, actually half a decade younger than the subjects in the prior study and contained individuals as young as 36 years of age who likely do not benefit from or may even respond negatively to such exogenous antioxidant treatment 33. In support of this interpretation, the placebo FMD of the control group in the current study was ~7%; whereas, the aged group in the paper published by Wray et al. was ~5% 33, thus there is less vascular dysfunction in the current control group likely attributable to a relatively younger cohort, albeit still lower vascular function than young individuals. However, more importantly, the current study reveals that, in comparison to age matched controls, patients with COPD exhibit reduced vascular function, which can be restored following ingestion of the AOC, suggestive of redox imbalance.

Previous work suggests that antioxidant capacity, as measured by Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC), was reduced in patients with COPD, resulting in greater superoxide levels in the blood 53. Numerous mechanisms could contribute to this reduced total antioxidant capacity such as reduced activity of superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase, etc.36, 54, 55. In the current study, basal levels of factors contributing to the antioxidant defense system, including superoxide dismutase activity and Vitamin C, were lower in the patients with COPD compared to controls (Figure 3). In parallel, TBARS, which estimates lipid peroxidation, a footprint of oxidative stress, was elevated in the patients with COPD (Figure 3) and is in agreement with prior literature suggesting that elevated oxidative stress is a characteristic of COPD 28. While we did not see an effect of the acute AOC on TBARS in either group, this lack of an effect agrees with prior work 35, 56. Specifically, such acute treatments may reduce free radicals, either through the inhibition of pro-oxidant enzymes (NADPH or oxidase xanthine oxidase) or direct molecular quenching, resulting in functional changes, but there is a delay in terms of when the downstream impact of the oxidative stress can be detected (e.g. TBARS). Indeed, the EPR data reported here suggests a reduction in free radicals with the ingestion of the AOC in the patients with COPD, but with such an approach we cannot ascertain all of the potential mechanisms or the exact origin of the free radicals. Future studies might consider the use of an inhaled formulation to better target the likely source of the inflammation and oxidative stress in the lungs 4. Consideration of both the antioxidant status and footprint of oxidative stress (TBARS), the patients with COPD appear to have an altered redox state due to a reduced antioxidant and/or pro-oxidant environment.

An oxidant imbalance contributes to greater levels of the free radicals superoxide and peroxynitrite, both potent endogenous competitors to the endothelial nitric oxide (NO)-vascular smooth muscle pathway 57, 58. Superoxide binds avidly with NO, reducing NO bioavailability, which increases the levels of peroxynitrite. Subsequently, peroxynitrite, itself, can oxidize tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), an essential co-factor for endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), leading to the uncoupling of eNOS which also reduces levels of NO, via reduced production 57, 59, 60. In vitro evidence suggests that Vitamin C, and likely other antioxidants, are capable of decreasing the oxidation of BH4 and preventing the uncoupling of eNOS 57, 61. It is likely that the reduced antioxidant status of patients with COPD resulted in greater free radical mediated reductions in NO bioavailability, either directly through the interaction of superoxide with NO, or indirectly through oxidation of BH4, which contributed to the blunted endothelial mediated FMD. In support of the contention that elevated free radicals are mediating the vascular dysfunction in patients with COPD, in the current study there was a significant increase in SOD in response to the AOC, likely due to a sparing of SOD, and a parallel reduction in total free radical signal, as measured by EPR in patients with COPD. Similarly, in agreement with the FMD findings, the PWV data indicated a COPD related elevation in arterial stiffness which was significantly reduced following ingestion of the AOC to within the values recommended for lower CVD risk 49 (Figure 2). These results highlight that PWV is also likely dependent upon free radical/antioxidant Redox balance and nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability, affecting vasomotor tone, and ultimately arterial distensibility 50–52, 62 in patients with COPD. As always, the effect of disease-specific medications on vascular function in a patient population such as this cannot be ruled out as playing a role in these findings.

Perspectives

The patients with COPD in this study had elevated oxidative stress, lower Vitamin C levels, and lower SOD activity, each likely contributing to impaired vascular function, as assessed by FMD and PWV. These findings contrast sharply with the age and sex matched controls. Also, of note, although not clearly demonstrating altered vascular function compared to the other patients, 17 of the patients with COPD compared to 7 of the controls exhibited medically-controlled hypertension. As the recruitment process was similar across all subjects, this difference highlights the elevated prevalence and/or risk of CVD amongst patients with COPD. Indeed, it was certainly possible that the greater incidence of hypertension in the patients with COPD could have explained the differences between the patients and age matched controls; however, employing several different statistical approaches, there was no evidence that this was the case. Therefore, based upon the current findings, it seems reasonable to propose that, in an attempt to improve vascular health and reduce cardiovascular disease risk in patients with COPD, an increase in antioxidant capacity could be targeted, perhaps by exogenous antioxidant supplementation or endogenously through exercise training 63, thereby reducing free radicals and improving endothelial function. While the success of the clinical trials using antioxidants as an intervention in CVD have been mixed 64–68, it is important to note that most trials have utilized a single antioxidant, and not a cocktail containing both water and fat soluble vitamins as in the current study. The antioxidant-induced improvement in vascular function, assessed by FMD and PWV, observed in the current study is suggestive of a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease associated with COPD, however, a randomized controlled trial with long-term supplementation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Experimental Considerations

As with most studies, especially those performed on clinical populations there are experimental considerations related to this work that need to be discussed. In the patients with COPD there were a disproportionate number of subjects with hypertension compared to controls, which proved not influence the conclusions of the current study, based upon post hoc matching of subjects and ANCOVA with hypertension as a covariate. However, this does raise the question, of what would be the impact of this AOC on subjects with a primary diagnosis of hypertension, but this is beyond the scope of the current study that focused upon COPD. It should also be recognized that there was not a statistically significant relationship between the indices of COPD severity and AOC-induced vascular function improvement, implying that other uncontrolled variables such as occult OSA, CAD, and the impact of several COPD-specific medications (e.g. long acting anticholinergics and β2-agonists) may have contributed to the variance in this study. A larger sample size and more proactive assessments of pathologies that do not come to light through health histories would be required to avoid these issues.

Conclusion

Patients with COPD exhibited altered redox balance as evidenced by blunted endogenous antioxidant capacity and elevated oxidative stress compared to age and sex matched controls. Vascular function, as measured by FMD and PWV, was impaired in patients with COPD when compared to controls. Following an acute AOC, antioxidant capacity was improved in patients with COPD, which coincided with significant improvements in vascular function, but not in controls. These results highlight the role of redox balance in vascular function of patients with COPD which likely contributes to the disproportionate risk for CVD in this population.

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is new?

This study has revealed that in comparison to healthy age matched controls, vascular endothelial function is impaired and vascular stiffness elevated in patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). This may help to explain the increased risk and prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with COPD. An acute oral antioxidant cocktail restored vascular function back to that of controls, highlighting the significant role that redox imbalance likely plays in this population.

What is relevant?

Vascular endothelial function and stiffness have been related to CVD, such as hypertension, CAD, or heart failure. Endothelial dysfunction has been demonstrated to precede the development of CVD. Restoring redox balance, via exogenous antioxidants, in patients with COPD may reduce CVD related morbidity and mortality in this population.

Summary

Patients with COPD exhibit impaired vascular endothelial function and elevated vascular stiffness, which appears to be mediated by a redox imbalance and may help to explain the increased risk of CVD in this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who volunteered for this study. We would also like to thank Jia Zhao and Van Reese for performing the blood assays.

SOURCES OF FUNDING: We would like to acknowledge financial support from NIH (P01 HL-091830 awarded to R.S.R), Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit grant E6910R awarded to R.S.R), and the American Heart Association (10SDG3050006 awarded to R.A.H, and 0835209N awarded to D.W.W). Advanced Fellowships in Geriatrics from the VA supported S.J.I, and M.A.H.W., in addition to a Career Development Award for J.M. (E7560W).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: none

References

- 1.Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Zulueta J, Cabrera C, Zagaceta J, Hunninghake G, Celli B, Group BC. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:155–161. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macnee W, Maclay J, McAllister D. Cardiovascular injury and repair in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:824–833. doi: 10.1513/pats.200807-071TH. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Konecny T, Somers K, Orban M, Koshino Y, Lennon RJ, Scanlon PD, Rihal CS. Interactions between copd and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Chest. 2010;138:621–627. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes PJ, Celli BR. Systemic manifestations and comorbidities of copd. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1165–1185. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luppi F, Franco F, Beghe B, Fabbri LM. Treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its comorbidities. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:848–856. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-101TH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sin DD, Wu L, Man SF. The relationship between reduced lung function and cardiovascular mortality: A population-based study and a systematic review of the literature. Chest. 2005;127:1952–1959. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuoka S, Yamashiro T, Diaz A, Estepar RS, Ross JC, Silverman EK, Kobayashi Y, Dransfield MT, Bartholmai BJ, Hatabu H, Washko GR. The relationship between small pulmonary vascular alteration and aortic atherosclerosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Quantitative ct analysis. Acad Radiol. 2011;18:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone IS, Barnes NC, Petersen SE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease? Heart. 2012;98:1055–1062. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Gooch VM, Miller, Sullivan ID, Lloyd JK, Deanfield JE, Spiegelhalter DJ. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. The Lancet. 1992;340:1111–1115. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93147-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeboah J, Crouse JR, Hsu FC, Burke GL, Herrington DM. Brachial flow-mediated dilation predicts incident cardiovascular events in older adults: The cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2007;115:2390–2397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, Johnson C, Polak JF, Post W, Lima JA, Crouse JR, Herrington DM. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;120:502–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Gerhard MD, Meredith IT, Knab S, Delagrange D, Lieberman EH, Ganz P, Creager MA, Yeung AC, Selwyn AP. Close relation of endothelial function in the human coronary and peripheral circulations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00327-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeboah J, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Mcburnie M, Burke G, Herrington D, Crouse J. Association between brachial artery reactivity and cardiovascular disease status in an elderly cohort: The cardiovascular health study. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:768–776. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1318–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Jacobs DR, Brumback L, Duprez DA, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Townsend RR, Vermeersch S, Segers P. Arterial wave reflections and incident cardiovascular events and heart failuremesa (multiethnic study of atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2170–2177. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber T, Auer J, O’Rourke MF, Kvas E, Lassnig E, Berent R, Eber B. Arterial stiffness, wave reflections, and the risk of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2004;109:184–189. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105767.94169.E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozben B, Eryuksel E, Tanrikulu AM, Papila-Topal N, Celikel T, Basaran Y. Acute exacerbation impairs endothelial function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi arsivi : Turk Kardiyoloji Derneginin yayin organidir. 2010;38:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eickhoff P, Valipour A, Kiss D, Schreder M, Cekici L, Geyer K, Kohansal R, Burghuber OC. Determinants of systemic vascular function in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:1211–1218. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1412OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr RG, Mesia-Vela S, Austin JHM, Basner RC, Keller BM, Reeves AP, Shimbo D, Stevenson L. Impaired flow-mediated dilation is associated with low pulmonary function and emphysema in ex-smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1200–1207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-980OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maclay JD, McAllister DA, Mills NL, Paterson FP, Ludlam CA, Drost EM, Newby DE, Macnee W. Vascular dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:513–520. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0414OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maclay JD, McAllister DA, Rabinovich R, Haq I, Maxwell S, Hartland S, Connell M, Murchison JT, van Beek EJ, Gray RD, Mills NL, Macnee W. Systemic elastin degradation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67:606–612. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivodtzev I, Minet C, Wuyam B, Borel JC, Vottero G, Monneret D, Baguet JP, Levy P, Pepin JL. Significant improvement in arterial stiffness after endurance training in patients with copd. Chest. 2010;137:585–592. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alford SK, van Beek EJ, McLennan G, Hoffman EA. Heterogeneity of pulmonary perfusion as a mechanistic image-based phenotype in emphysema susceptible smokers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7485–7490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913880107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arao T, Takabatake N, Sata M, Abe S, Shibata Y, Honma T, Takahashi K, Okada A, Takeishi Y, Kubota I. In vivo evidence of endothelial injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by lung scintigraphic assessment of 123i-metaiodobenzylguanidine. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1747–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peinado VI, Barbera JA, Ramirez J, Gomez FP, Roca J, Jover L, Gimferrer JM, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Endothelial dysfunction in pulmonary arteries of patients with mild copd. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L908–913. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.6.L908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao J, Wood JG, Gonzalez NC. Alveolar macrophages initiate the systemic microvascular inflammatory response to alveolar hypoxia. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;178:439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.03.008. Epub 2011 Mar 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabit R, Shale DJ. Vascular structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A chicken and egg issue? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1175–1176. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200709-1428ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folchini F, Nonato NL, Feofiloff E, D’Almeida V, Nascimento O, Jardim JR. Association of oxidative stress markers and c-reactive protein with multidimensional indexes in copd. Chron Respir Dis. 2011;8:101–108. doi: 10.1177/1479972310391284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eagan TM, Ueland T, Wagner PD, Hardie JA, Mollnes TE, Damas JK, Aukrust P, Bakke PS. Systemic inflammatory markers in copd: Results from the bergen copd cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:540–548. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00088209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinto-Plata VM, Mullerova H, Toso JF, Feudjo-Tepie M, Soriano JB, Vessey RS, Celli BR. C-reactive protein in patients with copd, control smokers and non-smokers. Thorax. 2006;61:23–28. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celli BR, Locantore N, Yates J, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, Bakke P, Calverley P, Coxson H, Crim C, Edwards LD, Lomas DA, Duvoix A, MacNee W, Rennard S, Silverman E, Vestbo J, Wouters E, Agustí A Investigators ftE. Inflammatory biomarkers improve clinical prediction of mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1065–1072. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201110-1792OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noguera A, Batle S, Miralles C, Iglesias J, Busquets X, MacNee W, Agusti AG. Enhanced neutrophil response in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2001;56:432–437. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wray DW, Nishiyama SK, Harris RA, Zhao J, McDaniel J, Fjeldstad AS, Witman MA, Ives SJ, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Richardson RS. Acute reversal of endothelial dysfunction in the elderly after antioxidant consumption. Hypertension. 2012;59:818–824. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.189456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wray DW, Uberoi A, Lawrenson L, Bailey DM, Richardson RS. Oral antioxidants and cardiovascular health in the exercise-trained and untrained elderly: A radically different outcome. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2009;116:433–441. doi: 10.1042/CS20080337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witman MA, Fjeldstad AS, McDaniel J, Ives SJ, Zhao J, Barrett-O’Keefe Z, Nativi JN, Stehlik J, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Vascular function and the role of oxidative stress in heart failure, heart transplant, and beyond. Hypertension. 2012;60:659–668. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg D, Youdim MB, Riederer P. Redox imbalance. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;318:201–213. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0976-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ijzerman RG, Serne EH, van Weissenbruch MM, de Jongh RT, Stehouwer CD. Cigarette smoking is associated with an acute impairment of microvascular function in humans. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2003;104:247–252. doi: 10.1042/CS20020318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, Jenkins CR, Hurd SS, Committee GS. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nhlbi/who global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (gold) workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson RS, Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Lawrenson L, Nishiyama S, Bailey DM. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: Role of free radicals. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2007;292:H1516–1522. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01045.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris RA, Nishiyama SK, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension. 2010;55:1075–1085. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang M, Bai Y, Ye P, Luo L, Xiao W, Wu H, Liu D. Type 2 diabetes is associated with increased pulse wave velocity measured at different sites of the arterial system but not augmentation index in a chinese population. Clin Cardiol. 2011;34:622–627. doi: 10.1002/clc.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEleavy OD, McCallum RW, Petrie JR, Small M, Connell JM, Sattar N, Cleland SJ. Higher carotid-radial pulse wave velocity in healthy offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21:262–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baguet JP, Kingwell BA, Dart AL, Shaw J, Ferrier KE, Jennings GL. Analysis of the regional pulse wave velocity by doppler: Methodology and reproducibility. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:407–412. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H European Network for Non-invasive Investigation of Large A. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meredith IT, Currie KE, Anderson TJ, Roddy MA, Ganz P, Creager MA. Postischemic vasodilation in human forearm is dependent on endothelium-derived nitric oxide. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 1996;270:H1435–H1440. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.4.H1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang AL, Silver AE, Shvenke E, Schopfer DW, Jahangir E, Titas MA, Shpilman A, Menzoian JO, Watkins MT, Raffetto JD, Gibbons G, Woodson J, Shaw PM, Dhadly M, Eberhardt RT, Keaney JF, Gokce N, Vita JA. Predictive value of reactive hyperemia for cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing vascular surgery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2113–2119. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitchell GF, Parise H, Vita JA, Larson MG, Warner E, Keaney JF, Keyes MJ, Levy D, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Local shear stress and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation: The framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2004;44:134–139. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000137305.77635.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pyke KE, Dwyer EM, Tschakovsky ME. Impact of controlling shear rate on flow-mediated dilation responses in the brachial artery of humans. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:499–508. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01245.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reference Values for Arterial Stiffness C. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: ‘Establishing normal and reference values’. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2338–2350. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naka KK, Tweddel AC, Doshi SN, Goodfellow J, Henderson AH. Flow-mediated changes in pulse wave velocity: A new clinical measure of endothelial function. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:302–309. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinlay S, Creager MA, Fukumoto M, Hikita H, Fang JC, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide regulates arterial elasticity in human arteries in vivo. Hypertension. 2001;38:1049–1053. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.095329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilkinson IB, Qasem A, McEniery CM, Webb DJ, Avolio AP, Cockcroft JR. Nitric oxide regulates local arterial distensibility in vivo. Circulation. 2002;105:213–217. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.101970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahman I, Morrison D, Donaldson K, MacNee W. Systemic oxidative stress in asthma, copd, and smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1055–1060. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Madamanchi NR, Vendrov A, Runge MS. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:29–38. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000150649.39934.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arthur JR. The glutathione peroxidases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1825–1835. doi: 10.1007/PL00000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silvestro A, Scopacasa F, Oliva G, de Cristofaro T, Iuliano L, Brevetti G. Vitamin c prevents endothelial dysfunction induced by acute exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:277–283. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuzkaya N, Weissmann N, Harrison DG, Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: Implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Somers MJ, Mavromatis K, Galis ZS, Harrison DG. Vascular superoxide production and vasomotor function in hypertension induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt. Circulation. 2000;101:1722–1728. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt TS, Alp NJ. Mechanisms for the role of tetrahydrobiopterin in endothelial function and vascular disease. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2007;113:47–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crabtree MJ, Tatham AL, Al-Wakeel Y, Warrick N, Hale AB, Cai S, Channon KM, Alp NJ. Quantitative regulation of intracellular endothelial nitric-oxide synthase (enos) coupling by both tetrahydrobiopterin-enos stoichiometry and biopterin redox status: Insights from cells with tet-regulated gtp cyclohydrolase i expression. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1136–1144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vásquez-Vivar J, Martásek P, Whitsett J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. The ratio between tetrahydrobiopterin and oxidized tetrahydrobiopterin analogues controls superoxide release from endothelial nitric oxide synthase: An epr spin trapping study. Biochem J. 2002;362:733–739. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3620733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramsey MW, Goodfellow J, Jones CJH, Luddington LA, Lewis MJ, Henderson AH. Endothelial control of arterial distensibility is impaired in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1995;92:3212–3219. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.11.3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Bailey DM, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Exercise-induced brachial artery vasodilation: Effects of antioxidants and exercise training in elderly men. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2010;298:H671–678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00761.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jialal I, Devaraj S. Antioxidants and atherosclerosis: Don’t throw out the baby with the bath water. Circulation. 2003;107:926–928. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048966.26216.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomson MJ, Puntmann V, Kaski JC. Atherosclerosis and oxidant stress: The end of the road for antioxidant vitamin treatment? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:195–210. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stephens NG, Parsons A, Schofield PM, Kelly F, Cheeseman K, Mitchinson MJ. Randomised controlled trial of vitamin e in patients with coronary disease: Cambridge heart antioxidant study (chaos) Lancet. 1996;347:781–786. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hodis HN, Mack WJ, LaBree L, Mahrer PR, Sevanian A, Liu CR, Liu CH, Hwang J, Selzer RH, Azen SP, Group VR. Alpha-tocopherol supplementation in healthy individuals reduces low-density lipoprotein oxidation but not atherosclerosis: The vitamin e atherosclerosis prevention study (veaps) Circulation. 2002;106:1453–1459. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000029092.99946.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Queiroz TM, Guimaraes DD, Mendes-Junior LG, Braga VA. Alpha-lipoic acid reduces hypertension and increases baroreflex sensitivity in renovascular hypertensive rats. Molecules. 2012;17:13357–13367. doi: 10.3390/molecules171113357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]