Abstract

Objective

To characterize the sexual function of both prostate cancer patients and their partners, and to examine whether associations between sexual dysfunction and psychosocial adjustment vary depending on spousal communication patterns.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 116 prostate cancer patients and their partners completed psychosocial questionnaires.

Results

Patients and partners reported high rates of sexual dysfunction. Within couples, patients’ and their partners’ sexual function was moderately to highly correlated (r = 0.30–0.74). When patients had poor erectile function, their partners were more likely to report that the couple avoided open spousal discussions; this in turn was associated with partners’ marital distress (Sobel's Z = 12.47, p = 0.001). Patients and partners who reported high levels (+1SD) of mutual constructive communication also reported greater marital adjustment, regardless of their own sexual satisfaction. In contrast, greater sexual dissatisfaction was associated with poorer marital adjustment in patients and partners who reported low levels (−1SD) of mutual constructive communication (p<0.05).

Conclusion

Our findings underscore the need for psychosocial interventions that facilitate healthy spousal communication and address the sexual rehabilitation needs of patients and their partners after prostate cancer treatment. Although some couples may be reluctant to engage in constructive cancer-related discussions about sexual problems, such discussions may help alleviate the negative impact that sexual problems have on prostate cancer patients’ and their partners’ marital adjustment.

Keywords: prostate cancer, sexual function, marriage, couples, communication patterns

Introduction

Sexual dysfunction, which affects 33–98% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer, is a frequently compromised aspect of patient quality of life (QOL) [1]. Given the nature of their disease and its treatment, patients experience reduced sexual desire and diffculty becoming aroused, maintaining erections, ejaculating, and achieving orgasm [2,3]. Although sexual activity and sexual function decrease with age—and the median age at prostate cancer diagnosis in the United States is 68 years [4]—a recent national probability study of 3005 older adults in the United States found that 73% of those aged 57–64 years, 53% of those aged 65–74 years, and 26% of those aged 75–85 years reported being sexually active [5]. Thus, many prostate cancer patients have active sex lives that are adversely affected by their disease and its treatment.

Because patients’ partners are likely to be of a similar age and experiencing the physical consequences of the aging process themselves, they may have sexual function issues of their own [6,7]. It is also well documented that within couples, sexual dysfunctions may coexist [8,9]; however, few studies have examined the association between prostate cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction and their female partner’s sexual function. Schover et al. [10] found that 66% of patients who had undergone treatment for localized prostate cancer reported that their female partners had some form of sexual problem; however, the partners themselves were not surveyed. Neese et al. [11] interviewed 164 women whose partners had undergone radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy for prostate cancer; 38% reported being at least ‘slightly dissatisfied’ with their sexual relationships after treatment. Finally, a study of 90 couples found that prostate cancer patients’ erectile dysfunction was negatively associated with their female partners’ desire, arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, and sexual activity [12]. These studies suggest that when evaluating prostate cancer patients’ sexual function, it is also important to assess their partners’ sexual function.

Although the lack of a fulfilling sex life has been linked to psychological and marital distress [11,13–16], sexual dysfunction may affect the adjustment of patients and their partners in different ways. For example, Perez et al. [17] found that erectile dysfunction was not associated with emotional distress or poor QOL among prostate cancer patients because patients considered their ability to perform day-to-day activities to be more important than their sexual function in terms of their overall well-being. In that study, partners’ responses to patient sexual dysfunction were not assessed; however, other studies suggest that partner responses play a critical role in patient adjustment. Indeed, after controlling for patients’ depression, one study found that partners’ levels of general depression and depression about their sex lives were significant predictors of patients’ relationship and sexual satisfaction, as well as their evaluations of the quality of spousal discussions about sexual issues [18]. Another study found that partners were less concerned with patient sexual function than they were about how patients’ sexual problems would affect relational intimacy and quality [19]. Thus, non-sexual ways of expressing intimacy (e.g. communication) may play an important role in maintaining couples’ relationships and facilitating both partners’ adaptation in the face of sexual dysfunction after the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer.

The importance of open spousal communication for positive adaptation in the face of chronic and life-threatening diseases is well documented [20–24]; however, the ability of patients’ and their partners’ to openly and effectively communicate varies [25]. In fact, research has suggested that patients and their partners often avoid discussing how a prostate cancer diagnosis and treatments affect their emotions and relationships [26]. Ofman found that patient sexual dysfunction led to emotional distancing [27], and others have found that a substantial minority of couples disagree about whether the patients’ erectile function is adequate for sexual intercourse [28], suggesting that some couples have impaired communication about sexual problems and concerns. Indeed, the tendency to avoid cancer-related discussions or of one partner to suppress the other's efforts to discuss cancer-related concerns have been identified as sources of marital tension among couples coping with prostate cancer [29,30].

Couples distressed about their sexual relationship may not engage in needed problem-solving discussions because sexual dysfunction is a sensitive topic. Yet not discussing the sexual relationship may exacerbate patient and partner distress. Research in non-medically ill couples has demonstrated that couples who openly discuss their problems (i.e. mutual constructive communication), report high marital satisfaction [31,32]. In contrast, couples in which one partner pressures the other to talk about a problem while the other partner withdraws or becomes defensive (i.e. demand withdraw communication), report lower marital satisfaction [31]. In a study of couples coping with early stage breast cancer, Manne et al. [33] found that mutual constructive communication about cancer-related concerns was associated with less distress and more relationship satisfaction, whereas demand–withdraw communication and mutual avoidance were associated with higher distress for patients and their partners. To our knowledge, however, no studies have examined these spousal communication patterns in prostate cancer or their associations with patient and partner adjustment in the face of sexual dysfunction.

Because sexual dysfunction affects both members of the couple, characterizing the sexual function of prostate cancer patients and their partners and identifying relationship factors that may alleviate the adverse effects of sexual dysfunction on adjustment are critical to the development of psychosocial interventions aimed at improving both partners’ QOL [9,34,35]. In this study, we hypothesized that the partners of prostate cancer patients would report significant subjective sexual dysfunction and that the sexual function of patients and their partners would be significantly correlated. We also hypothesized that engaging in mutual constructive communication would alleviate the negative effects patient and/or partner sexual dysfunction has on both partners’ psychological and marital adjustment.

Methods

Eligibility and recruitment

The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this study. Eligible patients were identified from a review of medical charts and approached about study participation during clinic visits or contacted by mail. Patients who were approached by mail were provided a toll-free number to call to decline participation. Everyone who received a letter and who did not call the toll-free number to decline was contacted by phone and asked to participate. Patients were eligible if they had a prostate cancer diagnosis, were able to read and speak English, and were able to provide written informed consent. Even though prostate cancer rarely occurs in younger men, given the legal age of consent, patient eligibility also included being aged 18 years or older. Partners were eligible if they were female, were married to or living with a patient diagnosed with prostate cancer, were able to read and speak English, and were able to provide written informed consent.

We approached 274 prostate cancer patients (140 during clinic visits, and 134 by mail) and their partners. Of these, 195 couples (71%) expressed interest in participating (124 of those who were approached in the clinic and 71 who were approached by mail) and further screened for eligibility. Although 29 patients were ineligible (17 did not have a live-in partner, 7 did not speak English, 1 could not provide informed consent, 1 was homosexual, and 3 did not have a confirmed prostate cancer diagnosis), 166 patients and their partners met the eligibility criteria and were either mailed or handed questionnaires (described below) and asked to return them by mail in separate postage-paid envelopes. A series of t-tests were performed to determine whether patients who were recruited in the clinic differed from those recruited by mail on any of the major study variables. The only significant difference was for age t(121) = 2.31, p = 0.02. Specifically, those recruited in the clinic were younger (M = 66.39, SD = 8.23) than those who were recruited by mail (M = 69.69, SD = 6.77).

Of the 166 couples who consented and received questionnaires, complete data (surveys from both partners) were obtained from 116 couples (in six cases, only the patient returned the questionnaire, and in four cases, only the partner returned the questionnaire). Thus, the percentage of passive refusals (those who consented but did not return the surveys) was 24% (40 out of 166 couples). Chisquare comparisons were made between participants and non-participants (those who refused and those who consented but did not return the surveys) based on available data for age and race/ethnicity. No significant between-group differences were found.

Measures

Sexual function

Patients’ sexual function

The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) is a validated 15-item survey that evaluates different domains of men's sexual function including erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction [36]. Patients were asked to subjectively rate their level of sexual function for the preceding 4 weeks on a Likert-type scale from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating better sexual function. The IIEF provides a total sexual function score (Range = 5–75), which is a sum of the domain scores. Researchers have also used domain scores separately to examine specific aspects of male sexual function [37]. The 6-item erectile function domain in particular has been used as a proxy for male sexual dysfunction [38]. Scores range from 0 to 30; scores less than 21 indicate erectile dysfunction [39]. In this study, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's α) for all the IIEF domains ranged from 0.89 to 0.97.

Partner's sexual function

The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) is a 19-item validated questionnaire that addresses six domains of women's sexual function: arousal, lubrication, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and sexual pain [40]. Partners were asked to rate their own sexual function for the preceding 4 weeks on a Likert-type scale. Scores range from 0 (or 1) to 5, with higher scores indicating better sexual function. Although clinical cutoff scores have not yet been established for the FSFI, we used the scoring guidelines suggested by Weigel et al. [41] to make differential diagnoses. Specifically, total scores less than 26.5 are suggestive of female sexual dysfunction, and scores less than 4.95 on the lubrication domain, 4.6 on the orgasm domain, and scores less than 3 on the sexual pain domain are suggestive of the need for further evaluation for sexual dysfunction. In this study, internal consistency for the FSFI domains ranged from 0.78 to 0.99.

Psychosocial adjustment

Marital adjustment

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) [42] is a 32-item self-report measure assessing four components of marital functioning: satisfaction, cohesion, consensus, and affectional expression. Total scores on the DAS could range from 0 to 151; scores below 100 indicate marital distress. In this study, internal consistency reliability was high (α = 0.89 for men and 0.95 for women).

Psychological distress

The Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale is a well-validated 20-item self-report measure focusing on affective symptoms, including depression, hopelessness, fear, and sadness [43]. Scores 16 and above suggest the need for psychological evaluation. Internal consistency reliability in this study was α = 0.78 for men and 0.83 for women.

Spousal communication patterns

The Communication Patterns Questionnaire (CPQ) [44] evaluates how couples communicate when a relationship problem arises, how they communicate when they discuss the problem, and how they communicate after such a discussion. All items were rated on a 9-point Likert-type scale that ranged from ‘unlikely’ to ‘likely’. In this study, we used three CPQ subscales: mutual constructive communication (7 items) [correction made here after initial online publication], total demand–withdraw communication (6 items), and mutual avoidance (3 items). For men, internal consistency reliability was α = 0.71 for mutual constructive communication, 0.76 for mutual avoidance, and 0.78 for demand-withdraw. For women, internal consistency reliability was α = 0.80 for mutual constructive communication, 0.74 for mutual avoidance, and 0.77 for demand–withdraw communication.

Results

Sample

Demographics and medical variables

Patients

Most patients were white (83.7%); had at least some college level education (76.4%); were retired (54.5%); and were married (99.2%). The mean age was 67.36 years (SD = 7.94, Range = 47–83 years). Almost 79% reported at least one co-morbid condition including hypertension (50%), heart conditions such as angina or heart arrhythmias (30%), ulcers (19%), and diabetes (14%). Time elapsed since initial cancer diagnosis ranged from less than 1 year to 22 years (M = 4.56 years, SD = 3.76 years). Disease stage at diagnosis was 33% Stage 1, 42% Stage 2, 19% Stage 3, and 6% Stage 4. We conducted a series of one-way ANOVAs to examine whether there were any differences in the main study variables by disease stage. No significant differences were found (p's 5 0.13–0.93).

Approximately 52% of patients were undergoing treatment (28% hormonal therapy, 6% chemotherapy, 8% radiation, and 10% combined modality therapy) at the time of this study. Patients’ past treatments for prostate cancer included surgery (58% of patients), radiation (44%), chemotherapy (26%), and hormonal therapy (56%). We conducted a series of t-tests on the main study variables to determine whether there were any differences between patients currently receiving treatment and patients who were not currently receiving treatment. Patients currently receiving treatment reported significantly lower IIEF total scores (M = 13.11, SD = 14.56) than patients not currently receiving treatment (M = 26.48, SD = 23.89), t(114) = −3.73, p = 0.001. Analysis of the IIEF erectile function domain scores showed that patients receiving treatment (M = 3.29, SD = 6.40) had poorer erectile function than patients not receiving treatment (M = 9.14, SD = 10.96), t(114) = −3.60, p = 0.001. Patients receiving treatment also reported having poorer orgasm function (t(112) = −2.76, p = 0.001), sexual desire (t(111) = −5.16, p = 0.001), and intercourse satisfaction (t(113) = −3.37, p = 0.001). However, it is important to note that both groups reported very low IIEF total scores and that the erectile function scores of both groups were far below the clinical cutoff of 21, indicating erectile dysfunction.

Partners

Most partners were white (82.9%), had at least some college level education (66.1%) and were retired or unemployed (66.9%). Average age was 62.70 years (SD = 8.32, Range 40–82). Almost 58% reported at least one chronic medical condition including: hypertension (44%), heart disease (13%), ulcers (11%), and rheumatoid arthritis (10%).

Descriptive results

Patients’ average CESD score was 9.85 (SD = 7.68); partners’ average CESD score was 8.70 (SD = 7.49). Twenty-six patients (22%) and 23 partners (20%) scored ≥ 16 on the CESD. Patients’ average DAS score was 104.47 (SD = 10.83); partners average DAS score was 102.41 (SD = 14.77). A total of 42 patients (34%) and 57 partners (47%) had DAS scores that indicated marital distress; in 24 of the 116 couples (21%), both the patient and his partner had scores that indicated marital distress. Approximately 10% of the sample reported currently receiving some type of psychosocial counseling (6% of patients and 3% of spouses reported currently attending a prostate cancer support group). No patients or partners reported currently being in family or marital counseling.

The means, SDs, and correlations of the major study variables are shown in Table 1. Almost 84% of patients scored below the IIEF cutoff for erectile dysfunction, and 81% of their partners scored below the FSFI cutoff for sexual dysfunction. Partners reported poorer lubrication, poorer orgasm function, and more sexual pain compared with the FSFI domain score guides for normal female sexual function provided by Weigel et al. [41].

Table 1.

Correlations, means, and standard deviations on major study variables for men and women

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Means±SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEN | |||||||||||||

| 1 | DAS | — | 104.47±10.83 | ||||||||||

| 2 | CESD | –0.25** | — | 9.85±7.68 | |||||||||

| 3 | MCC | 0.50** | –0.33** | — | 13.57±7.37 | ||||||||

| 4 | MA | –0.29** | 0.21* | –0.62** | — | 8.37±4.83 | |||||||

| 5 | DWC | –0.33** | 0.05 | –0.60** | 0.63** | — | 16.58±9.02 | ||||||

| 6 | Erectile function | 0.16# | –0.15 | 0.10 | –0.08 | –0.08 | — | 5.89±9.24 | |||||

| 7 | Orgasmic function | 0.06 | –0.15 | 0.15 | –0.18* | –0.09 | 0.85** | — | 2.20±3.58 | ||||

| 8 | Sexual desire | 0.12 | –0.19* | 0.08 | –0.10 | –0.05 | 0.61* | 0.64** | — | 4.07±2.14 | |||

| 9 | Intercourse satisfaction | 0.16 | –0.17# | 0.16# | –0.13 | –0.06 | 0.90** | 0.90** | 0.64** | — | 2.54±4.50 | ||

| 10 | Overall satisfaction | 0.20* | –0.20* | 0.23* | –0.12 | –0.16# | 0.62** | 0.63** | 0.48** | 0.63** | — | 4.89±2.97 | |

| 11 | IIEF total score | 0.17# | –0.18* | 0.14 | –0.09 | –0.12 | 0.96** | 0.93** | 0.70** | 0.95** | 0.73** | — | 18.98±20.36 |

| WOMEN | |||||||||||||

| 1 | DAS | — | 102.41±14.77 | ||||||||||

| 2 | CESD | –0.13 | — | 8.70±7.49 | |||||||||

| 3 | MCC | 0.54** | –0.23* | — | 12.68±8.42 | ||||||||

| 4 | MA | –0.21* | 0.08 | –0.48** | — | 8.38±5.06 | |||||||

| 5 | DWC | –0.14 | –0.01 | –0.48** | 0.56** | — | 16.79±9.01 | ||||||

| 6 | Sexual desire | 0.10 | –0.19# | –0.001 | 0.10 | 0.11 | — | 2.69±1.78 | |||||

| 7 | Arousal | 0.18# | –0.17# | 0.15 | –0.01 | –0.002 | 0.63** | — | 2.16±2.28 | ||||

| 8 | Lubrication | 0.17# | –0.22* | 0.11 | 0.006 | 0.03 | 0.63** | 0.92** | — | 1.71±2.34 | |||

| 9 | Orgasmic function | 0.19* | –0.23* | 0.16 | –0.06 | 0.006 | 0.59** | 0.91** | 0.94** | — | 1.73±2.38 | ||

| 10 | Intercourse satisfaction | 0.31** | –0.31** | 0.36** | –0.32** | –0.19# | 0.19# | 0.63** | 0.60** | 0.62** | — | 3.56±1.83 | |

| 11 | Sexual pain | 0.12 | –0.19# | 0.12 | –0.08 | 0.03 | 0.34** | 0.59** | 0.62** | 0.64** | 0.60** | — | 1.63±2.53 |

| 12 | FSFI total score | 0.15 | –0.24* | 0.16 | –0.11 | –0.05 | 0.62** | 0.93** | 0.94** | 0.94** | 0.74** | 0.79** | 14.64±11.01 |

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

MCC, Mutual Constructive Communication; MA, Mutual Avoidance; DWC, Demand–Withdraw Communication.

To examine relationships among the major study variables, Pearson's correlations were calculated separately for patients and their partners. Patients’ sexual desire was negatively related to their distress (p<0.05). Partners’ orgasmic function, lubrication, and sexual satisfaction were significantly negatively associated with their distress; orgasmic function and sexual satisfaction were also significantly associated with partners’ marital adjustment.

To estimate correlations between patients and their partners, we used a pairwise approach recommended by Gonzalez and Griffn [45] that takes into account the degree of non-independence within dyad members. For each estimate, we defined a strong correlation as being greater than 0.6, a moderate correlation as being between 0.30 and 0.59, and a weak correlation as being 0.29 and below. Moderate to high (r = 0.30–0.74) within-couple correlations were found on all dimensions of patients’ and partners’ sexual function; reports of marital and psychological adjustment were also moderately correlated (Table 2). Patients’ erectile function and intercourse satisfaction were significantly positively associated with their partners’ marital adjustment, and significantly negatively associated with their partners’ distress. Patients’ and partners’ reports of mutual constructive and demand–withdraw communication were only weakly correlated. Reports of mutual avoidance were not correlated.

Table 2.

Paired correlations for prostate cancer patients and their partners

| Partners | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Marital adjustment | Distress | MCC | MA | DWC | Sexual desire | Arousal | Lubrication | Orgasmic function | Intercourse satisfaction | Sexual pain | FSFI total score |

| Marital adjustment | 0.43** | –0.24* | 0.33** | –0.05 | –0.13 | –0.03 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.28** | 0.29** | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Distress | –0.18# | 0.35** | –0.10 | 0.03 | 0.21 | –0.15 | –0.20# | –0.25* | –0.24* | –0.17 | –0.21# | –0.25* |

| MCC | 0.41** | –0.33** | 0.27* | –0.07 | –0.31** | –0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.22* | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| MA | –0.31** | 0.04 | –0.24* | 0.08 | 0.17 | –0.01 | –0.19* | –0.07 | –0.13 | –0.19* | 0.02 | –0.11 |

| DWC | –0.22* | 0.11 | –0.18# | 0.12 | 0.26* | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 | –0.23* | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Erectile function | 0.22* | –0.26** | 0.24* | –0.27** | –0.15 | 0.30** | 0.54** | 0.57** | 0.66** | 0.54** | 0.74** | 0.69** |

| Orgasmic function | 0.25* | –0.16 | 0.20# | –0.17 | –0.16 | 0.37** | 0.62** | 0.61** | 0.71** | 0.57** | 0.71** | 0.72** |

| Sexual desire | 0.14 | –0.12 | 0.12 | –0.17 | –0.17 | 0.32** | 0.56** | 0.54** | 0.61** | 0.49** | 0.60** | 0.63** |

| Intercourse satisfaction | 0.26* | –0.24* | 0.20* | –0.21* | –0.15 | 0.33** | 0.59** | 0.60** | 0.68** | 0.61** | 0.80** | 0.74** |

| IIEF total score | 0.25* | –0.26* | 0.21* | –0.16 | –0.26* | 0.33** | 0.61** | 0.62** | 0.72** | 0.60** | 0.78** | 0.75** |

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01.

MCC, Mutual Constructive Communication; MA, Mutual Avoidance; DWC, Demand–Withdraw Communication.

Analysis plan

We conducted a series of multiple regression analyses to examine the relationship between patient/partner sexual function (IIEF/FSFI domain scores) and spousal communication patterns (mutual constructive communication, mutual avoidance, and demand–withdraw communication) and their effect on the outcomes of psychological and marital adjustment after controlling for age, number of comorbidities, disease stage, and time since diagnosis. Because data from dyad members are interdependent, using a multilevel dyadic data analytic model such as the Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) is preferable [46]. Instead of analyzing patients’ and partners’ data separately, this approach allows researchers to simultaneously examine patients’ and partners’ data and to examine actor effects (the effects of one person's behaviors/perceptions on their own outcomes) and partner effects (the effects of one person's behaviors/perceptions on their partner's outcomes) [47]. Using the APIM, actor and partner effects can be estimated for mixed variables or for interactions between mixed-variables and between-dyad (e.g. length of marriage) or within-dyad (e.g. gender) variables [47]. In the current study, however, patients and partners reported on their own sexual function using different measures. Thus, sexual function could not be considered a mixed variable, and using the APIM would be inappropriate.

To examine the effects of patients’ or partner's sexual functioning on their own and each other's outcomes, we structured the data set such that data from patients and their partners were paired for each couple. Standard multiple regression techniques were then used to analyze patient and partner outcomes separately. Where applicable, the effect size r, associated with each t was calculated using the formula [48].

Associations of sexual function and spousal communication with psychosocial adjustment

Does the association between patients’ sexual function and their own psychosocial adjustment (i.e. psychological distress and marital adjustment) vary depending on communication patterns?

For the outcome of psychological distress, we found no significant interaction effects between men's sexual function and their reports of spousal communication.

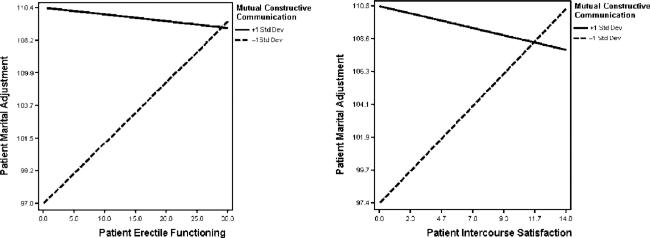

For the outcome of marital adjustment, we found significant interactions between patients’ sexual function and their reports of spousal communication (See Table 3). Illustrative plots depicting these interactions are shown in Figure 1. Specifically, patients who reported a high degree of mutual constructive spousal communication (+1SD) reported better marital adjustment overall than patients who reported a low degree (−1SD) of mutual constructive communication. Moreover, for patients who reported a low degree (− 1SD) of mutual constructive communication, greater erectile dysfunction was associated with lower marital adjustment (effect size r = 0.21). A similar pattern was found for patients’ intercourse satisfaction (effect size r = 0.23).

Table 3.

Moderating effects of mutual constructive communication on the associations between patient erectile function/intercourse satisfaction and patient marital adjustment

| b | StdErr | B | t | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Intercept | 91.47 | 8.24 | ||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.09 | –1.579 | 0.69 |

| Number of comorbidities | –0.44 | 0.57 | –0.07 | –0.77 | –0.224 | 0.24 |

| Stage of cancer | 0.50 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.43 | –1.81 | 2.81 |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 1.55 | –0.12 | 0.94 |

| Erectile function | 0.61 | 0.22 | 0.53 | 2.73* | 0.168 | 1.06 |

| MCC | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.61 | 6.31** | 0.624 | 1.20 |

| Erectile function × MCC | –0.03 | 0.01 | –0.48 | –2.33* | –0.058 | –0.005 |

| Intercept | 94.64 | 7.68 | ||||

| Age | –0.02 | 0.11 | –0.02 | –0.19 | –0.24 | 0.20 |

| Number of comorbidities | –0.52 | 0.53 | –0.10 | –0.98 | –1.58 | 0.54 |

| Stage of cancer | 0.32 | 1.10 | 0.03 | 0.30 | –1.82 | 2.47 |

| Time since diagnosis | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 1.42 | –0.14 | 0.84 |

| Intercourse satisfaction | 1.43 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 2.96** | 0.47 | 2.39 |

| MCC | 0.79 | 0.14 | 0.64 | 5.89** | 0.52 | 1.06 |

| Intercourse satisfaction × MCC | –0.07 | 0.03 | –0.61 | –2.52* | –0.13 | –0.02 |

MCC, Mutual Constructive Communication.

Figure 1.

Moderating effects of mutual constructive communication on the associations between patient erectile function/intercourse satisfaction and patient marital adjustment

Does the association between patients’ sexual function and their partners’ psychosocial adjustment (i.e. psychological distress and marital adjustment) vary depending on communication patterns?

For the outcome of psychological distress, we found no significant interactions between patients’ sexual function and partners’ reports of spousal communication. However, partners who reported greater mutual avoidance of discussing problems reported greater distress (t(114) = 2.02, p = 0.05, effect size r = 0.19).

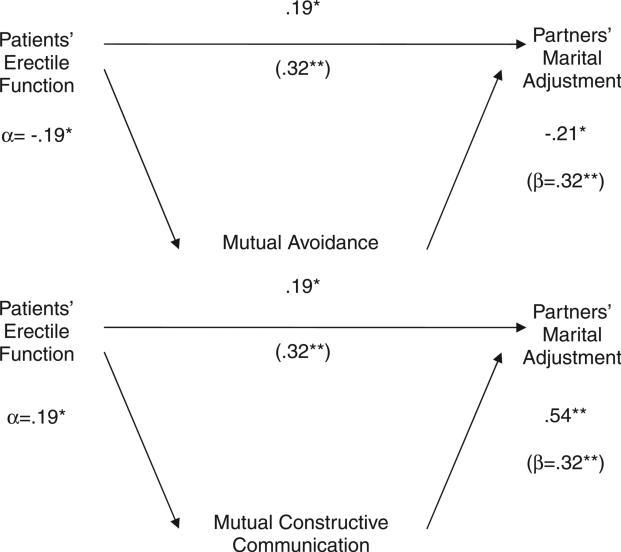

For the outcome of marital adjustment, we found no significant interactions between patients’ sexual function and partners’ reports of spousal communication patterns. However, associations between some of the variables suggested possible mediation. Using the statistical methods recommended by MacKinnon et al. to test mediation [49,50], we found that mutual constructive communication (Sobel's Z = 12.47, p = 0.001) and mutual avoidance (Sobel's Z = 12.47, p = 0.001) partially mediated the association between patients’ erectile function and their partners’ marital adjustment. Greater erectile dysfunction was associated with partners reporting more mutually avoidant spousal communication, which, in turn, was associated with partners’ marital distress (Figure 2). In contrast, better erectile function was associated with partners’ reporting more mutual constructive spousal communication, which, in turn, was positively associated with partners’ marital adjustment.

Figure 2.

Mediating effects of communication patterns on the association between patients’ erectile function and partners’ marital adjustment

Does the association between partners’ sexual function and their own psychosocial adjustment vary depending on communication patterns?

For the outcome of psychological distress, we found no significant interactions between partners’ sexual function and their reports of spousal communication.

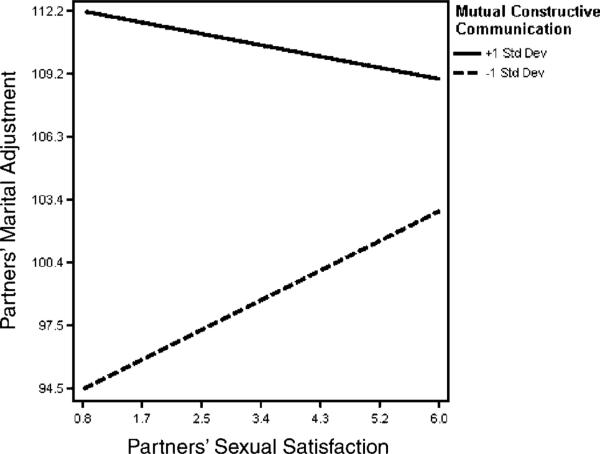

For the outcome of marital adjustment, we found that greater mutual avoidance (t(113) = −3.24, p = 0.002, effect size r = 0.29), and demand–withdraw communication (t(113) = −2.49, p = 0.01, effect size r = 0.23) were associated with greater marital distress. We also discovered a significant interaction between partners’ sexual satisfaction and reports of mutual constructive communication (t(113) - −2.02, p = 0.05, effect size r = 0.19). Figure 3 provides an illustrative plot depicting this interaction. Specifically, partners who reported a high degree of mutual constructive spousal communication (+ 1SD) reported higher levels of marital adjustment, regardless of their own level of sexual satisfaction. However, greater sexual dissatisfaction was associated with lower marital adjustment for partners who reported low levels of mutual constructive communication (− 1SD).

Figure 3.

Moderating effects of mutual constructive communication on the association between partners’ sexual satisfaction and their marital adjustment

Does the association between partners’ sexual function and patients’ psychosocial adjustment vary depending on communication patterns?

For the outcome of psychological distress, no significant interactions between wives’ sexual function and husbands’ reports of spousal communication patterns were found. However, men did report less distress when their wives reported better overall sexual function (wives’ FSFI total score), t(114) = −2.39, p = 0.02, effect size r = 0.22.

For the outcome of marital adjustment, we found no significant interactions between partners’ sexual function and patients’ reports of spousal communication patterns. However, patients did report greater marital adjustment when their partners reported being more sexually satisfied (t(113) = 2.03, p = 0.05, effect size r = 0.19).

Discussion

We found that patients and their partners both experience a high degree of sexual dysfunction, that patient and partner sexual dysfunction is related, and that sexual dysfunction was negatively associated with the psychological and marital adjustment of both prostate cancer patients and their partners. Paired correlations were moderate to high in almost all dimensions of patients’ and partners’ sexual function. Sexual dysfunction in either the patient or partner may have increased the incidence of sexual dysfunction in the other. Supporting this idea, Schover et al. [10] found that patients who had a partner with good sexual function had better sexual outcomes after prostate cancer treatment. Another study found that having a sexually active partner enhanced patients’ adherence to treatment for sexual dysfunction after prostate cancer treatment [51]. In the current study, patients reported lower levels of distress when their partners reported better overall sexual function and they reported greater marital adjustment when their partners reported greater sexual satisfaction. Moderate correlations between patients and their partners were also found with regard to psychological and marital distress. Thus, patient and partner sexual function and adjustment appear to be related. Although assortive mating may partially explain these findings, the presence of male sexual dysfunction and/or adjustment problems should prompt evaluation of the female partner in order to optimize therapy for the couple.

Our findings suggest that healthy spousal communication patterns may play an important role in alleviating the adverse effects of patients’ and partners’ own sexual dysfunction or dissatisfaction on their own marital adjustment. However, patients and their partners did not express strong agreement with regard to their reports of spousal communication. More research is needed to determine the source of this discrepancy. Because of their different roles in the marriage, patients and their partners may differ with respect to what they expect or need from each other and their relationship. This in turn may affect their perceptions of spousal communication, particularly its impact on psychosocial adjustment. Another possibility is that one partner may be more likely to voice his or her concerns more often than the other partner—who may take on a more supportive role and consequently not voice his or her own concerns—leading to a divergence in perspectives and different evaluations of spousal discussions. Future studies that employ observational methods to assess spousal communication in the setting of prostate cancer may help overcome some of the biases inherent in self-reports.

Although patients and their partners did not agree on how often they engaged in different spousal communication patterns, the perception that one was engaging in open, constructive spousal communication may have helped buffer couples from the negative effects of sexual dysfunction/dissatisfaction on their relationships. Specifically, patients who reported high levels of mutual constructive communication also reported better marital adjustment than those who reported low levels of mutual constructive communication, regardless of their level of erectile dysfunction. Patients and partners who reported more mutual constructive communication also reported better marital adjustment, regardless of their own levels of sexual satisfaction. Studies have shown that among non-medically ill couples, husbands and wives who report lower levels of sexual function and/or satisfaction are more likely to report lower levels of marital adjustment and marital quality [52,53]. Perhaps in the context of a life-threatening medical condition, such as prostate cancer, engaging in mutual constructive spousal communication can serve as a useful tool for helping couples to deal more effectively with their sexual problems and maintain and/or enhance marital quality.

Despite the potential utility of engaging in mutual constructive spousal communication, our findings suggest that couples coping with prostate cancer avoid engaging in mutual constructive communication when experiencing sexual problems. Partners were more likely to report engaging in mutual constructive spousal communication when patients had better erectile function and were more likely to report engaging in mutual avoidance when patients had poorer erectile function, which in turn, was associated with partners reporting lower marital adjustment. Interestingly, we found that communication patterns did not mediate the association between patients’ erectile function and patients’ marital adjustment. One possibility is that patients and their partners differed in their perceptions of communication patterns as evidenced by the low to non-significant paired correlations for these variables. One study has suggested that women focus more of their attention on their relationships and value open spousal communication more than men do [54], and, as such, may be more attuned to the effects of sexual problems on everyday patterns of relating. Still, our findings are consistent with studies that have shown that couples who decrease or discontinue sexual relations may also reduce expressions of non-sexual intimacy [55], such as engaging in healthy spousal communication. Given that almost 34% of patients and 47% of partners met the DAS criteria for marital distress and that the average length of time since diagnosis was 4.56 years, future prospective studies should examine how the effects of sexual problems on the frequency and quality of spousal communication in the setting of prostate cancer may ‘wear’ on a relationship over time.

This study had some limitations. We did not have pre-cancer sexual function data for either partner, so we could not assess the actual impact of prostate cancer on couples’ sexual and marital relationships. Thus, while it is likely that prostate cancer adversely affected patients’ sexual function—which, in turn, adversely affected their partners’ sexual function—it is also possible that for some couples, one or both partners had poor sexual function before the prostate cancer diagnosis due to advanced age and/or other medical conditions. Similarly, our determination of sexual function was based on participant self-report. People vary in what they consider adequate sexual function, and we had no way of knowing if participants’ sexual dysfunction was simply perceived or medically verifiable.

The cross-sectional nature of our study did not allow us to test whether spousal communication patterns mediated the relationship between patient sexual dysfunction and partner marital adjustment, or whether, for example, patient sexual dysfunction mediated the association between communication patterns and partner marital adjustment. Even though we found significant associations between communication and sexual function, the effect sizes for these interactions were low, which could be attributed to the fact that our communication measure assessed general patterns of discussions of marital problems and not discussions of sexual problems in particular. Another limitation is that the sample was relatively homogeneous in terms of race/ethnicity. Research has shown that African-American men weigh the risk of sexual dysfunction differently than do Caucasian men and view sexual function as more important to partner acceptance [56]. Future studies should thus seek to oversample racial and ethnic minorities to help increase the generalizability of findings.

Given the exploratory nature of our study, participation was restricted to men who had female sexual partners; and ultimately, almost all of the patients who participated were married. However, not all men are heterosexual or have sex within the confines of marriage. Blank [57] estimated that at least 5000 gay or bisexual men are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year in the United States; however, there is a dearth of research on the sexual functioning and relationship issues that gay, bisexual, and even heterosexual single men experience after prostate cancer treatment. For example, very little is known about how support and communication processes differ among couples where both partners are men compared with couples comprising a man and a woman. It is also unclear whether engaging in mutual constructive communication with an intimate partner is as important to the successful adaptation of gay and heterosexual patients who are single compared with those who are in more long-term, monogamous relationships. Finally, because the erectile function suitable for oral or anal penetration is different than that required for vaginal intercourse, [57] gay and bisexual men—and their partners—may be differently affected by erectile dysfunction in terms of their QOL and adjustment. Future studies will benefit from paying more careful attention to potential differences in the importance of erectile function, the centrality and role of communication with an intimate partner, and the ways in which sexual dysfunction may inhibit or disrupt one's relationship depending on one's sexual orientation and/or marital status.

Despite its limitations, this study represents an important first step toward understanding the role of spousal communication patterns in couples’ psychosocial adaptation in the face of sexual dysfunction following prostate cancer treatment. This is one of only a handful of studies that has used validated instruments to examine sexual function in the setting of prostate cancer from both patients’ and their partners’ perspectives. This study also highlights the importance of viewing sexual dysfunction after prostate cancer as a couples’ issue and underscores the need for more psychosocial interventions targeting both members of the couple. Indeed, many wives prefer to be included in their husbands’ health care, are open to receiving psychosocial counseling, and believe that seeking help for a sexual problem is something that should be decided mutually [11]. Thus, services that address patients and their partners conjointly and focus on coping with distress, sexual concerns, and spousal communication patterns following the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer may be beneficial for improving both partners’ QOL and adjustment.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported in part by a supplement to grant 5P30 CA16672-25 (Principal Investigator, John Mendel-sohn, MD; Project Leader, Cindy L. Carmack Taylor, PhD), and a multi-disciplinary award from the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command W81XWH-0401-0425 (Principal Investigator, Hoda Badr, PhD).

The authors would like to thank Dr. Leslie Schover for her helpful comments on a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

This article was published online on 5 December 2008. An error was subsequently identified. This notice is included in the online and print versions to indicate that both have been corrected [26/06/2009].

References

- 1.Sanders S, Pedro LW, Bantum EO, Galbraith ME. Couples surviving prostate cancer: long-term intimacy needs and concerns following treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10:503–508. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornblith A, Herr H, Ofman U, Sher H, Holland J. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses: the value of a database in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes in men treated for localized prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;273:129–135. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ries L, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975– 2004. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2007. (Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/, based on November 2006 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site 2007.) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Revenson TA. Social support and marital coping with chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes R, Dennerstein L. The impact of aging on sexual function and sexual dysfunction in women: a review of population-based studies. J Sex Med. 2005;2:317–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fugl-Meyer A, Fugl-Meyer K. Sexual disabilities are not singularities. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:487–493. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowe H, Costello AJ. Prostate cancer: perspectives on quality of life and impact of treatment on patients and their partners. Urol Nurs. 2003;23:279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1773–1785. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neese LE, Schover LR, Klein EA, Zippe C, Kupelian PA. Finding help for sexual problems after prostate cancer treatment: a phone survey of men's and women's perspectives. Psycho-Oncology. 2003;12:463–473. doi: 10.1002/pon.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shindel A, Quayle S, Yan Y, Husain A, Naughton C. Sexual dysfunction in female partners of men who have undergone radical prostatectomy correlates with sexual dysfunction of the male partner. J Sex Med. 2005;2:833–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Althof SE. Quality of life and erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2002;59:803–810. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz CE, Covino N, Morgentaler A, DeWolf W. Quality-of-life after penile prosthesis placed at radical prostatectomy. Psychol Health. 2000;15:651–661. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couper J, Bloch S, Love A, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of female partners of men with prostate cancer: a review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:937–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowan G, Mills R. Personal inadequacy and intimacy predictors of men’s hostility toward women. Sex Roles. 2004;51:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perez MA, Skinner EC, Meyerowitz BE. Sexuality and intimacy following radical prostatectomy: patient and partner perspectives. Health Psychol. 2002;21:288–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garos S, Kluck A, Aronoff D. Prostate cancer patients and their partners: differences in satisfaction indices and psychological variables. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1394–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petry H, Berry D, Spichiger E, et al. Responses and experiences after radical prostatectomy: perceptions of married couples in Switzerland. Int J Nurs Stud. 2004;41:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kornblith A, Regan M, Kim Y, et al. Cancer-related communication between female patients and male partners scale: a pilot study. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:780–794. doi: 10.1002/pon.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suls J, Green P, Rose G, Lounsbury P, Gordon E. Hiding worries from one's spouse: associations between coping via protective buffering and distress in male post-myocardial infarction patients and their wives. J Behav Med. 1997;20:333–349. doi: 10.1023/a:1025513029605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Badr H, Acitelli LK, Carmack Taylor CL. Does talking about their relationship affect couples’ marital and psychological adjustment to lung cancer? J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:53–64. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Badr H, Carmack Taylor C. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:673–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilton B. Family communication patterns in coping with early breast cancer. West J Nurs Res. 1994;16:366–388. doi: 10.1177/019394599401600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehmer U, Clark JA. Communication about prostate cancer between men and their wives. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ofman US. Sexual quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:1949–1953. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cytron S, Simon D, Segenreich E. Changes in the sexual behavior of couples after prostatectomy. A prospective study. Eur Urol. 1987;13:35–38. doi: 10.1159/000472733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornblith A, Herr HW, Ofman US, Scher HI, Holland JC. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses: the value of a data base in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavery JF, Clarke VA. Prostate cancer: patients’ and spouses’ coping and marital adjustment. Psychol Health Med. 1999;4:289–302. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christensen A, Shenk JL. Communication, conflict, and psychological distance in nondistressed, clinic, and divorcing couples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:458–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heavey CL, Christensen A, Malamuth NM. The long-itudinal impact of demand and withdrawal during marital conflict. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:797–801. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manne S, Ostroff J, Norton T, et al. Cancer-related relationship communication in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:234–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manne S, Babb J, Pinover W, Horwitz E, Ebbert J. Psychoeducational group intervention for wives of men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13:37–46. doi: 10.1002/pon.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Northouse L, Mood D, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosen R, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for the assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Briganti A, Naspro R, Gallina A, et al. Impact on sexual function of holmium laser enucleation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: results of a prospective, 2-center, randomized trial. J Urol. 2006;175:1817–1821. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tokatli Z, Akand M, Yaman O, Gulpinar O, Anafarta K. Comparison of International Index of Erectile Function with nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity testing in evaluation of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18:186–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosen R, Cappelleri J, Smith M, Lipsky J, Pena B. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–326. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosen R, Brown CH, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen A. Dysfunctional interaction patterns in couples. In: Noller P, Fitzpatrick M, editors. Perspectives on Marital Interaction. Multilingual Matters. Philadelphia: 1988. pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez R, Griffin D. The correlational analysis of dyad-level data in the distinguishable case. Pers Relatsh. 1999;6:449–469. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenny D, Kashy DA, Cook D. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data. Pers Relatsh. 2002;9:327–342. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel Analysis. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17:144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacKinnon DP, Warsi G, Dwyer JH. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multivariate Behav Res. 1995;30:41–62. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. The use of treatments for erectile dysfunction among survivors of prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:2397–2407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henderson-King DH, Veroff J. Sexual satisfaction and marital well-being in the first years of marriages. J Soc Pers Relationships. 1994;11:509–534. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edwards JN, Booth A. Sexuality, marriage, and well-being: the middle years. In: Rossi AS, editor. Sexuality Across the Life Course. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1994. pp. 233–259. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Acitelli LK, Young AM. Gender and thought in relationships. In: Fletcher G, Fitness J, editors. Knowledge Structures and Interactions in Close Relationships: A Social Psychological Approach. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schover LR. Sexual rehabilitation after treatment for prostate cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:1024–1030. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3+<1024::aid-cncr2820711421>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jenkins R, Schover LR, Fouladi RT, et al. Sexuality and health-related quality of life after prostate cancer in African-American and White men treated for localized disease. J Sex Marital Ther. 2004;30:79–93. doi: 10.1080/00926230490258884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blank TO. Gay men and prostate cancer: invisible diversity. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2593–2596. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]