Abstract

Objectives

To describe real-world treatment patterns and health care resource use and to estimate opportunities for early-switch (ES) from intravenous (IV) to oral (PO) antibiotics and early-discharge (ED) for patients hospitalized in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) complicated skin and soft tissue infections.

Methods

This retrospective observational medical chart review study enrolled physicians from four UAE sites to collect data for 24 patients with documented MRSA complicated skin and soft tissue infections, hospitalized between July 2010 and June 2011, and discharged alive by July 2011. Data include clinical characteristics and outcomes, hospital length of stay (LOS), MRSA-targeted IV and PO antibiotic use, and ES and ED eligibility using literature-based and expert-validated criteria.

Results

Five included patients (20.8%) were switched from IV to PO antibiotics while being inpatients. Actual length of MRSA-active treatment was 10.8±7.0 days, with 9.8±6.6 days of IV therapy. Patients were hospitalized for a mean 13.9±9.3 days. The most frequent initial MRSA-active therapies used were vancomycin (37.5%), linezolid (16.7%), and clindamycin (16.7%). Eight patients were discharged with MRSA-active antibiotics, with linezolid prescribed most frequently (n=3; 37.5%). Fifteen patients (62.5%) met ES criteria and potentially could have discontinued IV therapy 8.3±6.0 days sooner, and eight (33.3%) met ED criteria and potentially could have been discharged 10.9±5.8 days earlier.

Conclusion

While approximately one-fifth of patients were switched from IV to PO antibiotics in the UAE, there were clear opportunities for further optimization of health care resource use. Over half of UAE patients hospitalized for MRSA complicated skin and soft tissue infections could be eligible for ES, with one-third eligible for ED opportunities, resulting in substantial potential for reductions in IV days and bed days.

Keywords: IV-to-PO switch, length of stay, clinical criteria, antibiotic therapy, economics

Introduction

Patients who are hospitalized due to complicated skin and soft tissue infections (cSSTIs) caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) represent a substantial clinical and economic burden.1–3 Standard treatment options for patients with MRSA cSSTIs include intravenous (IV) antibiotic therapy, frequently using vancomycin. Although these infections have a relatively low risk of complications, readmissions, or mortality once the patient is stabilized, patients often remain in the hospital for the full duration of treatment.

Treatment options are available that allow some of these patients to complete therapy outside the hospital through either outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) or oral (PO) antibiotic therapy, with PO therapy preferred by patients in many settings.4,5 There are several PO therapies with activity against MRSA available as options for patients with MRSA cSSTIs, including clindamycin, linezolid, and rifampicin, in combination with another active agent, doxycycline, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Selection must be guided by local susceptibility data, as MRSA isolate resistance varies; it should also consider properties such as tolerability, bioavailability, and efficacy in patients with complicated disease.6,7

Epidemiologic reports of MRSA burden in the Middle East vary by country but suggest rates of 20%–60% in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from blood cultures.8 Data specific to MRSA are very limited in the Middle East despite the growing information needs of clinical and policy decision-makers for real-world treatment patterns and opportunities to improve efficiency of care. Recently, the largest real-world chart review of MRSA cSSTI in 12 European countries was reported.9,10 This study evaluated the proportion of patients who, in current practice, are actually switched from IV to PO therapy or are discharged on OPAT. In addition, it sought to determine the proportion of patients who may be eligible for IV-to-PO switch (early switch [ES]) and early discharge (ED) from inpatient to outpatient IV or PO antibiotic therapy, using a set of literature-based, expert-validated criteria. Our aim was to apply this study concept using the same criteria-based approach to emerging markets through a real-world study of treatment patterns, health care resource use, and criteria-based assessment of ES and ED opportunities in patients with MRSA cSSTIs in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Methods

This retrospective observational medical chart review study was an extension of a chart review in 12 European countries, which has been published elsewhere.9,10 Data were collected in the UAE between November 2012 and February 2013 from medical charts of patients treated for documented MRSA cSSTI admitted to the hospital from July 1, 2010, through June 30, 2011, and discharged alive by July 31, 2011. Collected data included clinical and resource utilization outcomes and real-world treatment patterns, including treatments utilized, IV antibiotic therapy duration, and hospital length of stay (LOS); these were documented for MRSA cSSTI patients. Patients who could have been switched from IV to PO MRSA therapy and those who could have been discharged earlier (ie, using oral antibiotics or OPAT) based on eligibility criteria (Table 1) were identified and the potential reduction in IV-line usage for antibiotic administration and hospital LOS was calculated.

Table 1.

Patient and disease characteristics

| All UAE patients (N=24) |

IV-to-PO switch (N=5) |

IV-only (N=19) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 50.2±16.1 | 54.2±16.3 | 49.1 ± 16.3 |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (45.8%) | 1 (20.0%) | 10 (52.6%) |

| Asian, n (%) | 22 (91.7%) | 3 (60.0%) | 19 (100.0%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity | 2.2±2.9 | 2.2±2.9 | 2.2±2.9 |

| Index, mean ± SD | |||

| Primary reason for hospitalization is treatment of MRSA cSSTI, n (%) | 16 (66.7%) | 4 (80.0%) | 12 (63.2%) |

| Timing of cSSTI diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| At hospital admission | 16 (66.7%) | 4 (80.0%) | 12 (63.2%) |

| 1–3 days after admission | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| 4+ days after admission | 6 (25.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Type of cSSTI, n (%) | |||

| Surgical site infection | 10 (41.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | 8 (42.1%) |

| Major abscess | 12 (50.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 9 (47.4%) |

| Deep/extensive cellulitis | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| cSSTI location, n (%) | |||

| Head/skull/neck | 3 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Torso/abdomen | 16 (66.7%) | 5 (100.0%) | 11 (57.9%) |

| Upper extremity | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Lower extremity | 4 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock during cSSTI episode, n (%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; IV, intravenous; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PO, oral; SD, standard deviation; UAE, United Arab Emirates.

Patient selection

Study investigators (hospital-based infectious disease specialists, internal medicine specialists with an infectious disease sub-specialty, and medical microbiologists) identified patients who had a microbiologically confirmed MRSA cSSTI, such as deep/extensive cellulitis, infected wound or ulcer, major abscess, or other soft tissue infections requiring substantial surgical intervention, and received ≥3 days of IV anti-MRSA antibiotics as determined by their physician. Anti-MRSA antibiotics included, but were not limited to, the following: clindamycin, daptomycin, fusidic acid, linezolid, rifampicin, teicoplanin, tigecycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and vancomycin.

Patients treated for the same cSSTI within 3 months of hospitalization and those with suspected or proven diabetic foot infections, osteomyelitis, infective endocarditis, meningitis, joint infections, necrotizing soft tissue infections, gangrene, prosthetic joint infection, or prosthetic implant/device infection were excluded from the study. Additionally, patients were excluded from the study if they were pregnant or lactating, had significant concomitant infection at other sites, were immunosuppressed (eg, diagnosed hematologic malignancy, neutropenia, or rheumatoid arthritis; receiving chronic steroids or cancer chemotherapy), or enrolled in another cSSTI-related clinical trial.

Actual treatment patterns

Actual treatment patterns were summarized in terms of the total length of antibiotic therapy, length of IV antibiotic therapy, and LOS. The actual length of therapy was calculated as the time between initiation of MRSA-targeted therapy and last day of MRSA-targeted therapy or discharge. IV length of therapy included only the subset of those days for which IV antibiotics were prescribed. LOS was calculated as the number of days from hospital admission for patients admitted for cSSTI, or cSSTI diagnosis date and hospital discharge. Time to MRSA-active therapy, number of lines of MRSA-active therapy, first and last MRSA-active antibiotics used, and frequency of MRSA-targeted antibiotics at hospital discharge were also evaluated.

Opportunities for ES and ED

ES and ED eligibility criteria for use in real-world clinical settings were created using literature review11–17 and expert consensus opinion. ES eligibility required the patient to meet all the following criteria prior to IV antibiotic discontinuation: stable clinical infection, afebrile/temperature <38°C for 24 hours, normalized white blood cell count (4×109/L< white blood cell <12×109/L), no unexplained tachycardia, systolic blood pressure ≥100 mg Hg (for OPAT), and oral fluids/medications/diet tolerated with no gastrointestinal absorption problems. ED eligibility, at a minimum, required the patient to meet all the criteria discussed earlier for ES prior to discharge, with no reason to remain in the hospital except for infection management.

For patients who were ES eligible, the hypothetical length of IV therapy was calculated as the days between the start of initial MRSA-targeted IV antibiotic administration and the date when patients satisfied the last of the key ES criteria. For patients who were ED eligible, hypothetical LOS was calculated as the days between when patients were admitted if their reason for admission was for cSSTI or the date on which the cSSTI was diagnosed, and the date when the last ED criteria was met. To understand the potential economic impact of ED, the estimated mean cost per bed days saved in ED-eligible patients was calculated by multiplying the bed days saved by a UAE-specific unit cost of $575.08 (2691 dirhams) per bed day based on World Health Organization-reported unit costs for providing a UAE hospital bed day in the year 2007;18 this was reported in international dollars (local currency units) and adjusted for inflation to the year 2012.19 Costs included by the World Health Organization represent the “hotel” component of hospital costs, such as personnel, capital, and food, and do not include drug and diagnostic test costs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted for all patients, and stratified by whether patients received IV-only antibiotics or were switched from IV to PO. No formal statistical testing was undertaken to compare IV-only and IV-to-PO switched patients, given the limited sample sizes.

Results

While the initial intent was to collect data from approximately ten sites, due to low prevalence of MRSA cSSTI, a total of 19 sites were recruited from which four sites were able to identify 24 eligible patients.

Patient and clinical characteristics

The majority of patients were Asian with an average age at hospital admission of 50.2 years and an almost even split between males and females (Table 2). Fourteen patients (58.3%) reported comorbidities, with diabetes (50%), congestive heart failure (16.7%), and chronic pulmonary disease (16.7%) being most frequently reported.

Table 2.

Actual antibiotic and health care resource use

| All UAE patients (N=24) |

IV-to-PO switch (N=5) |

IV-only (N=19) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of MRSA-targeted lines of therapy, n(%) | |||

| 1 | 16 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (84.2%) |

| 2 | 5 (20.8%) | 3 (60.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| 3 | 3 (12.5%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| MRSA-active length of therapy (including PO), mean ± SD | 10.8±7.0 | 12.6±7.4 | 10.4±7.1 |

| MRSA-active IV days, mean (SD) | 9.8±6.6 | 7.4±4.6 | 10.4±7.1 |

| MRSA-targeted antibiotics used in initial line, n (%) | |||

| Clindamycin IV | 4 (16.7%) | 2 (40.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Linezolid IV | 4 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Meropenem IV | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Teicoplanin IV | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Tigecycline IV | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Vancomycin IV | 8 (33.3%) | 2 (40.0%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| Tigecycline IV + Vancomycin IV | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| MRSA-targeted antibiotics used in last line, n (%) | |||

| Clindamycin IV | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Clindamycin PO | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Linezolid IV | 5 (20.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Linezolid PO | 3 (12.5%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Meropenem IV | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| TMP/SMX PO | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0.%) |

| Teicoplanin IV | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Tigecycline IV | 2 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) |

| Vancomycin IV | 6 (25%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (31.6%) |

| Tigecycline IV + Vancomycin IV | 1 (4.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) |

| MRSA-targeted antibiotics prescribed at discharge | 8 (33.3%) | 3 (60%) | 5 (26.3%) |

| Ciprofloxacin POa | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20%) |

| Clindamycin POa | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Doxycycline POa | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| Linezolid POa | 3 (37.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (40.0%) |

| Trimethoprim POa | 1 (12.5%) | 1 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| TMP/SMX POa | 1 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) |

| LOS, days from cSSTI index through discharge, mean (SD) | 13.9±9.3 | 14.2±7.6 | 13.8±9.8 |

| Regular ward days, mean (SD) | 10.3±8.9 | 14.2±7.6 | 9.3±9.1 |

| High dependency/intermediate care days, mean (SD) | 2.9±8.3 | 0±0 | 3.6±9.3 |

| Intensive care unit days, mean (SD) | 0.6±3.1 | 0±0 | 0.8±3.4 |

| Surgical procedures for cSSTI treatment, n (%) | 21 (87.5%) | 5 (100.0%) | 16 (84.2%) |

| Total number of procedures among those with any procedures, mean ± SD | 1.1 ±0.6 | 1.2±0.4 | 1.1 ±0.6 |

Note:

Denominator is patients with any MRSA-targeted antibiotic prescribed at discharge.

Abbreviations: cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; IV, intravenous; LOS, length of stay; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PO, oral; SD, standard deviation; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; UAE, United Arab Emirates.

Two-thirds of patients reported treatment of MRSA cSSTI (66.7%) as the primary reason for hospitalization, with 41.7% of patients presenting with a surgical site infection, 50% with major abscess, and 8.3% deep/extensive cellulitis.

Actual treatment patterns and health care resource utilization

All patients received at least one MRSA-active therapy, and of these, five (20.8%) were switched from IV-to-PO MRSA-active therapy while hospitalized. Mean (± standard deviation) LOS from cSSTI diagnosis through discharge was 13.9±9.3 days. Almost all patients (87.5%) required at least one surgical procedure, such as debridement, incision, or drainage for cSSTI management.

The mean time to administration of MRSA-active therapy was 1.7±1.2 days following MRSA cSSTI diagnosis. Mean length of MRSA-active antibiotic treatment by any route (ie, IV, intramuscular, or PO) was 10.8±7.0 days, with MRSA-active IV antibiotic treatment lasting a mean 9.8±6.6 days. Sixteen patients (66.7%) were treated with a single MRSA-active antibiotic regimen, five patients (20.8%) changed at least one MRSA-active regimen, and three patients (12.5%) modified their antibiotic regimen twice while in the hospital (changes from IV to PO formulations of the same medication, such as linezolid IV to linezolid PO, were not counted as a regimen change).

The most frequently prescribed initial MRSA-active therapy was vancomycin (37.5%), followed by linezolid (16.7%) and clindamycin (16.7%) (Table 2). Analysis of final inpatient MRSA-active antibiotic regimens showed that during the course of treatment the proportion of inpatients receiving vancomycin decreased, whereas the proportion of patients receiving linezolid IV and PO increased (Table 2). A total of eight patients (33.3%) were discharged from the hospital on either a PO MRSA-active antibiotic regimen, with linezolid PO being the discharge antibiotic for 37.5% patients.

The mean duration of MRSA-active IV therapy for patients who were switched from IV to PO therapy was 7.4±4.6 days compared with 10.4±7.1 days for patients treated only by the IV-only route. Mean hospital LOS was similar for patients who were switched from IV to PO therapy compared with patients treated only by the IV route (14.2±7.6 days versus 13.8±9.8 days, respectively).

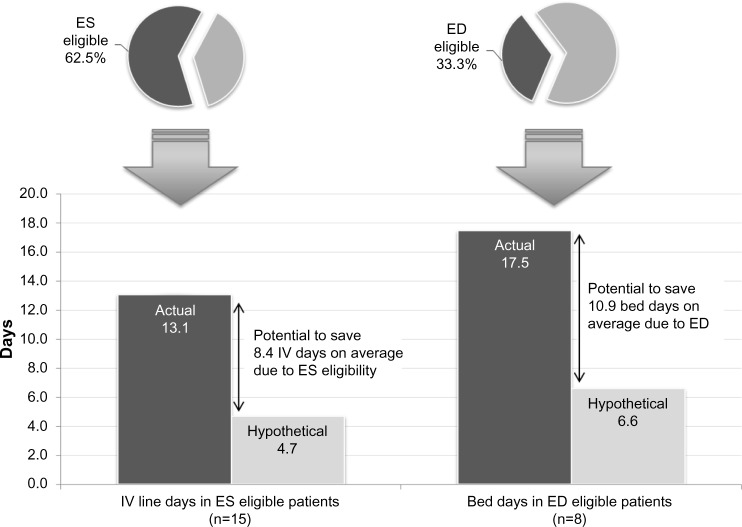

Actual and hypothetical outcomes based on ES and ED eligibility

A total of 15 (62.5%) patients met all six key ES criteria prior to actual IV discontinuation. Among the ES-eligible patients, the actual mean length of IV therapy was 13.1±6.4 days but hypothetically could have been 4.7±3.7 days when removing days after patients met all ES criteria, suggesting a potential reduction in IV therapy duration of 8.3±6.0 days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of actual and hypothetical IV-line and bed days in ES- and ED-eligible patients.

Abbreviations: ED, early discharge; ES, early switch; IV, intravenous.

Eight patients (33.3%) met all key ED criteria prior to hospital discharge. The actual mean LOS for patients meeting key ED criteria was 17.5±6.9 days; the hypothetical LOS for these patients was 6.6±3.2 days, suggesting a potential reduction in LOS of 10.9±5.8 days (Figure 1). Assuming an average cost of $575.08 (2691 dirhams) per bed day, the total savings would be $6268 (29,333 dirhams) in bed-day cost savings realized per ED-eligible patient.

Discussion

This is the first study in the UAE to retrospectively evaluate actual real-world clinical practice and assess ES and ED opportunities in hospitalized patients with MRSA cSSTIs. In this study, almost two-thirds of patients with MRSA cSSTIs met ES criteria and one-third met ED criteria prior to actual discharge. In eligible patients, the IV days and LOS could potentially be reduced by ~8 days and ~11 days, respectively. These results suggest important policy implications for the UAE that should be further investigated in larger patient samples across the Middle East.

This study supports the growing demand and need for real-world comparative effectiveness data in the Middle East. Often clinical trial populations are not reflective of the typical patient population seen in clinical practice. Our study addresses this need for clinical practice data in MRSA cSSTI and provides a snapshot of management patterns in the UAE, making this data set unique, as there are very few sources of data in the Middle East with both clinical and resource utilization details.

Results from our research appear to indicate a similar or greater need for ES/ED antibiotic policies in the UAE compared with Europe and USA, where ED policies are already in place in some institutions. Published studies enrolling patients with various infectious diseases in several European countries and the USA suggest that ~30% to more than 50% of patients could be switched from IV to PO antibiotic therapy11,15,20–23 and that 20%–30% of patients could be discharged earlier on PO antibiotic therapy.11,15,22 These rates are lower than those observed within this UAE population. Moreover, recent data from a 12-country ES/ED study in Europe using the same methodology as this UAE pilot study suggest that more patients are eligible for ES or ED in the UAE as compared with Europe, with rates of ES ranging from 12.0% (Slovakia) to 56.3% (Greece) and ED from 10.0% (Slovakia) to 48.2% (Portugal).9,10 However, mean actual MRSA-active antibiotic days and LOS were shorter than those observed in any European countries studied (mean MRSA-active IV days from 10.1 days [United Kingdom] to 16.6 days [Poland]; LOS from 15.2 days [United Kingdom] to 25.0 days [Portugal]).

This study was a medical chart review conducted retrospectively, and therefore, our results are subject to the well-known limitations of this study design. Because information was limited to medical charts, dates that patients met criteria for ES and ED were estimated based on data available in the patients’ medical records if these dates were not recorded. Finally, it was also not possible to proactively apply ES and ED criteria to determine the actual (rather than potential) cost-savings using a retrospective study design. Ideally, the applicability of the ES and ED criteria used in this study needs to be validated prospectively.

Several challenges exist for the treatment of hospitalized patients in Middle Eastern low- and middle-income countries, including bed capacity, LOS, and efficiency of care.24,25 For the majority of cSSTIs, the key cost driver is hospital LOS (in general or specialist wards).26,27 Therefore, identification of ES and ED opportunities for patients with MRSA cSSTI hospitalized in the UAE, and more broadly in the Middle East, could lead to significant reductions in LOS, thereby providing a mechanism for improving hospital efficiency to meet the needs of more patients.

Conclusion

This proof-of-concept study suggests that almost two-thirds of patients with MRSA cSSTI in the UAE could potentially be switched to PO therapy and more than one-third discharged earlier from the hospital, resulting in potential cost savings for the health care system. This evidence, specific to MRSA cSSTI, suggests that hospitals in the Middle East should explore the implementation of such ES and ED pathways and that implementation should be tailored to the local culture and environment and to fit within their budget and broad antibiotic stewardship strategies.28

Acknowledgments

Clinical experts involved in the original study design, which was adapted to the UAE:

UK: Dilip Nathwani, Wendy Lawson; Germany: Christian Eckmann; France: Eric Senneville; Spain: Emilio Bouza; Italy: Giuseppe Ippolito; Austria: Agnes Wechsler Fördös; Portugal: Germano do Carmo; Greece: George Daikos; Slovakia: Pavol Jarcuska; Czech Republic: Michael Lips, Martina Pelichovska; and Ireland: Colm Bergin.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Ashraf El Houfi and Nadeem Javed have received no financial support toward the production of this article. Ashraf El Houfi has received lecture fees, travel support for attending meetings, and fees for advisory boards from Pfizer, Sanofi, MSD, and 3M. Nadeem Javed has received lecture fees, travel support for attending meetings, and/or fees for advisory boards from Pfizer. Jennifer M Stephens and Caitlyn T Solem are employees of Pharmerit International and were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with this study. Cynthia Macahilig is an employee of Medical Data Analytics, a subcontractor to Pharmerit International for this project. Nirvana Raghubir, Richard Chambers, Jim Z Li, and Seema Haider are employees of Pfizer. Editorial support in preparing the manuscript for submission was provided by Paul Hassan of Engage Scientific, Horsham, UK, and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author contributions

Ashraf El Houfi, Nadeem Javed, Caitlyn T Solem, Jennifer M Stephens, Nirvana Raghubir, Richard Chambers, Jim Z Li, and Seema Haider contributed to the study design. Cynthia Macahilig was involved in data acquisition. Caitlyn T Solem, Jennifer M Stephens, Cynthia Macahilig, and Richard Chambers undertook data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Edelsberg J, Berger A, Weber DJ, Mallick R, Kuznik A, Oster G. Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(2):160–169. doi: 10.1086/526444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatoum HT, Akhras KS, Lin SJ. The attributable clinical and economic burden of skin and skin structure infections in hospitalized patients: a matched cohort study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;64(3):305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsky BA, Weigelt JA, Gupta V, Killian A, Peng MM. Skin, soft tissue, bone, and joint infections in hospitalized patients: epidemiology and microbiological, clinical, and economic outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(11):1290–1298. doi: 10.1086/520743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bamford KB, Desai M, Aruede MJ, Lawson W, Jacklin A, Franklin BD. Patients’ views and experience of intravenous and oral antimicrobial therapy: room for change. Injury. 2011;42(Suppl 5):S24–S27. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(11)70129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borner M, Scheithauer W, Twelves C, Maroun J, Wilke H. Answering patients’ needs: oral alternatives to intravenous therapy. Oncologist. 2001;6(Suppl 4):12–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-suppl_4-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha BA. Oral antibiotic therapy of serious systemic infections. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(6):1197–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, et al. Infectious diseases society of America and the society for healthcare epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borg MA, de Kraker M, Scicluna E, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in invasive isolates from southern and eastern Mediterranean countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(6):1310–1315. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckmann C, Lawson W, Nathwani D, et al. Antibiotic treatment patterns across Europe in patients with complicated skin and soft-tissue infections due to meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a plea for implementation of early switch and early discharge criteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathwani D, Eckmann C, Lawson W, et al. Pan-European early switch/early discharge opportunities exist for hospitalized patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):993–1000. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai M, Franklin BD, Holmes AH, et al. A new approach to treatment of resistant gram-positive infections: potential impact of targeted IV to oral switch on length of stay. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:94–100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SL, Azmi S, Wong PS. Clinicians’ knowledge, beliefs and acceptance of intravenous-to-oral antibiotic switching, Hospital Pulau Pinang. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67(2):190–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matthews PC, Conlon CP, Berendt AR, et al. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT): is it safe for selected patients to self-administer at home? A retrospective analysis of a large cohort over 13 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(2):356–362. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathwani D, Moitra S, Dunbar J, Crosby G, Peterkin G, Davey P. Skin and soft tissue infections: development of a collaborative management plan between community and hospital care. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52(7):456–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parodi S, Rhew DC, Goetz MB. Early switch and early discharge opportunities in intravenous vancomycin treatment of suspected methicillin-resistant staphylococcal species infections. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9(4):317–326. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seaton RA, Bell E, Gourlay Y, Semple L. Nurse-led management of uncomplicated cellulitis in the community: evaluation of a protocol incorporating intravenous ceftriaxone. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(5):764–767. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1651–1672. doi: 10.1086/420939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization WHO-CHOICE Unit Cost Estimates for Service Delivery. 2011. [Accessed February 12, 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/choice/country/country_specific/en/index.html.

- 19.Trading Economics United Arab Emirates Consumer Price Index (CPI) 2008–2014. [Accessed November 5, 2013]. Available from: http://www.tradingeconomics.com/united-arab-emirates/consumer-price-index-cpi.

- 20.Buyle FM, Metz-Gercek S, Mechtler R, et al. Prospective multicentre feasibility study of a quality of care indicator for intravenous to oral switch therapy with highly bioavailable antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(8):2043–2046. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Giammarino L, Bihl F, Bissig M, Bernasconi B, Cerny A, Bernasconi E. Evaluation of prescription practices of antibiotics in a medium-sized Swiss hospital. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(47–48):710–714. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dryden M, Saeed K, Townsend R, et al. Antibiotic stewardship and early discharge from hospital: impact of a structured approach to antimicrobial management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(9):2289–2296. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertz D, Koller M, Haller P, et al. Outcomes of early switching from intravenous to oral antibiotics on medical wards. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(1):188–199. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arabi Y, Venkatesh S, Haddad S, Al Shimemeri A, Al Malik S. A prospective study of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit: predictors and impact on resource utilization. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(5):403–410. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/14.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong R, Hathi S, Linnander EL, et al. Building hospital management capacity to improve patient flow for cardiac catheterization at a cardiovascular hospital in Egypt. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(4):147–153. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38019-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Hospitalizations with healthcare-associated complicated skin and skin structure infections: impact of inappropriate empiric therapy on outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):535–540. doi: 10.1002/jhm.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of hospitalizations with complicated skin and skin-structure infections: implications of healthcare-associated infection risk factors. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(12):1203–1210. doi: 10.1086/648083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharpe BA. Putting a critical pathway into practice: the devil is in the implementation details. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):928–929. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]