Abstract

Rationale: Interstitial lung disease (ILD), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), is highly prevalent, yet RA-ILD is underrecognized.

Objectives: To identify clinical risk factors, autoantibodies, and biomarkers associated with the presence of RA-ILD.

Methods: Subjects enrolled in Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) cohorts were evaluated for ILD. Regression models were used to assess the association between variables of interest and RA-ILD. Receiver operating characteristic curves were generated in BRASS to determine if a combination of clinical risk factors and autoantibodies can identify RA-ILD and if the addition of investigational biomarkers is informative. This combinatorial signature was subsequently tested in ACR.

Measurements and Main Results: A total of 113 BRASS subjects with clinically indicated chest computed tomography scans (41% with a spectrum of clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD) and 76 ACR subjects with research or clinical scans (51% with a spectrum of RA-ILD) were selected. A combination of age, sex, smoking, rheumatoid factor, and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies was strongly associated with RA-ILD (areas under the curve, 0.88 for BRASS and 0.89 for ACR). Importantly, a combinatorial signature including matrix metalloproteinase 7, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine, and surfactant protein D significantly increased the areas under the curve to 0.97 (P = 0.002, BRASS) and 1.00 (P = 0.016, ACR). Similar trends were seen for both clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD.

Conclusions: Clinical risk factors and autoantibodies are strongly associated with the presence of clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD on computed tomography scan in two independent RA cohorts. A biomarker signature composed of matrix metalloproteinase 7, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine, and surfactant protein D significantly strengthens this association. These findings may facilitate identification of RA-ILD at an earlier stage, potentially leading to decreased morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: interstitial lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, subclinical, biomarkers, risk prediction

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Approximately 10% of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have clinically evident interstitial lung disease (ILD) and an additional 30% have subclinical ILD, yet RA-ILD is poorly understood and underrecognized. It is unknown if a combination of well-established clinical risk factors, autoantibodies, and novel biomarkers can identify patients with RA with a spectrum of ILD.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We demonstrate that a model composed of age, sex, smoking history, rheumatoid factor, and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies is strongly associated with the presence of both clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD in two independent cohorts. A peripheral blood biomarker signature composed of matrix metalloproteinase 7, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine, and surfactant protein D significantly strengthens this association. These findings suggest that currently available clinical risk factors, autoantibodies, and investigational biomarkers could be used to identify patients with RA-ILD.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (1), a highly prevalent systemic connective tissue disease, currently affects approximately 1.5 million adults in the United States (2). With the successful implementation of disease-modifying agents and biologics geared toward management of articular disease (3), lung disease has become one of the leading causes of death in patients with RA, second only to cardiovascular disease (4). A spectrum of interstitial lung disease (ILD) is present on the computed tomography (CT) scans of 30–60% of patients with RA (5–7) and is the only complication of RA increasing in prevalence (4, 8). Furthermore, although RA mortality rates are declining, death from RA-ILD has increased (9), emphasizing the need for improved detection and earlier intervention.

Clinically evident RA-ILD (previously diagnosed ILD) occurs in about 10% of the RA population (5, 6, 8, 9). Subclinical disease (10) (no previous ILD diagnosis but interstitial lung abnormalities [ILA] [11] on CT) is present in an additional 30% of individuals (7, 9), with 34–57% demonstrating radiologic progression over 1–2 years (12, 13). These data support the hypothesis that some subclinical RA-ILD could eventually progress to clinically evident disease. Despite this, RA-ILD often goes unrecognized, highlighting the need for clinical tools that identify early stages of disease, such as clinical prediction models.

Given the radiologic and histologic overlap between RA-ILD and the usual interstitial pneumonia pattern pathognomonic for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (14–16), several studies have noted that patients with RA-ILD and IPF share similar risk factors. For instance, risk factors for RA-ILD and most idiopathic interstitial pneumonias include older age, male sex, and smoking (16–21). Moreover, our group has recently shown that peripheral blood levels of matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP7), a biomarker associated with survival in IPF (22–24), are significantly elevated in patients with RA with both clinically established and subclinical ILD (25). Based on these findings we hypothesize that validated IPF biomarkers associated with clinical outcomes, such as MMP7, pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine (PARC)/CC-chemokine ligand-18 (26, 27), and surfactant protein D (SP-D) (28–31), could identify RA-ILD (6). Importantly, several independent IPF biomarker studies suggest that peripheral blood biomarkers are most effective when used in conjunction with clinical risk factors (23, 28). In addition, it is important to note that multiple independent studies have shown that select autoantibodies (high-titer rheumatoid factor [RF] [17, 18, 32] and anticyclic citrullinated peptide [CCP] antibodies [17, 18, 33–35]) are specifically associated with the presence of ILD in patients with RA and therefore could further enhance the value of clinical risk factors.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate if a combination of previously identified clinical risk factors and autoantibodies can identify the presence of clinically evident and subclinical ILD in two independent RA cohorts. In addition, we will determine if the addition of a combinatorial biomarker signature composed of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D can strengthen the association with a spectrum of RA-ILD. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (36).

Methods

Study Design

The Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) is a large, single-center, prospective observational study of more than 1,350 subjects established in 2003. Protocols for enrollment and data collection have been described previously (37) and are available online (www.BRASSstudy.org). BRASS subjects with chest CT scans performed for clinical indications (18) and with blood samples (n = 113) were evaluated for ILD. A subset of subjects had pulmonary function testing (PFT) available. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) cohort consisted of patients with RA evaluated for ILD through the University of Pittsburgh and the Brigham and Women’s Hospital between 2010 and 2013. ACR subjects with CT scans available to be interpreted (n = 76) were included in this study. Baseline demographics and smoking history were obtained from the medical records. We have previously reported subject characteristics of the BRASS and ACR cohorts (18, 25). More details including timing of the serum samples, autoantibodies, and PFTs are found in the online supplement. This project was granted institutional review board approval by the Partners Human Research Committee at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (protocol number 2010-P-002840/1).

High-Resolution CT Analysis

Chest CT scans were evaluated for the presence of ILA (18) using a sequential reading method previously described and detailed in the online supplement (11, 38). Based on the presence of ILA, individuals were classified as having clinically evident, subclinical, or indeterminate RA-ILD (see Figure E1 in the online supplement).

Multiplex ELISA

Serum samples were analyzed for three investigational biomarkers (MMP7, PARC, and SP-D) using a customMAP multiplex bead-based immunoassay as previously described (Rules Based Medicine, Austin, TX) (39, 40).

Statistical Analysis

Univariate analyses were conducted with Fisher exact tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests where appropriate. For multivariate analyses, unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were used to assess the strength of the association between RA-ILD and investigational biomarkers. Select variables of interest (age, sex, smoking, RF, and anti-CCP) were adjusted for in logistic regression models in BRASS and ACR. To evaluate the ability of a combinatorial signature to identify the presence of RA-ILD, we first evaluated clinical risk factors (age, sex, and smoking history) associated with RA-ILD in the literature and our univariate analyses in BRASS. We subsequently added autoantibodies (RF and anti-CCP) and investigational biomarkers (MMP7, PARC, and SP-D). Respiratory symptoms and PFTs were not included in our exploratory modeling given the variability in available data between the two cohorts and the large amount of missing data.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to identify if a combinatorial signature composed of these clinical risk factors and autoantibodies was effective in identifying subjects with RA-ILD, including clinically evident and subclinical disease, from no RA-ILD. We subsequently generated the areas under the curve (AUC) for each biomarker of interest and determined if a combination of these investigational proteins improved performance of the clinical signature. This combinatorial signature was tested in the ACR cohort and subsequently evaluated in a combination of BRASS and ACR cohorts We believe that the utility of a diagnostic test derived from these variables lies in its ability to identify subclinical disease. Therefore, we derived a risk score for subclinical RA-ILD in BRASS subjects and subsequently assessed performance characteristics in ACR subjects with subclinical RA-ILD. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

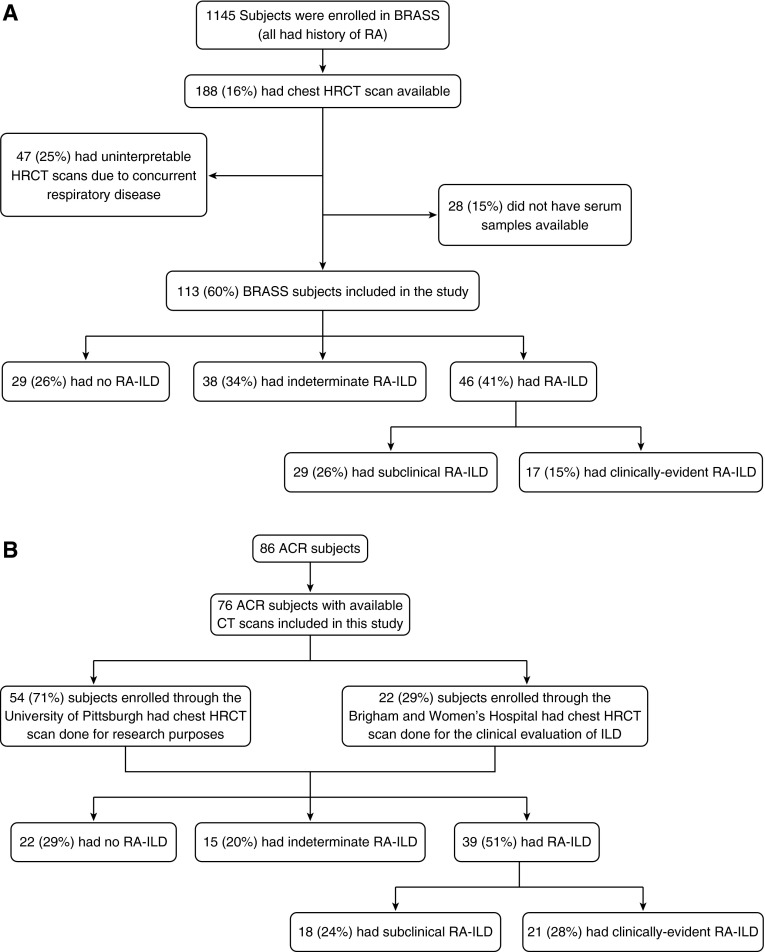

Of 1,145 BRASS subjects enrolled, 113 were included in this study (Figure 1A); 29 (26%) had no evidence of ILD on chest CT scan and 46 (41%) had a spectrum of RA-ILD, including 17 (15%) with clinically evident RA-ILD and 29 (26%) with subclinical RA-ILD. A total of 38 (34%) had indeterminate ILA. Of the 17 subjects with clinically evident RA-ILD, 10 had evidence of radiologically severe ILA on CT scan and 7 had evidence of ILA on CT scan and reported a previous history of ILD. Of 86 ACR subjects, 76 had chest high-resolution CTs available for interpretation by the sequential reading method. Based on this assessment, 21 (28%) subjects had clinically evident RA-ILD, 18 (24%) had subclinical RA-ILD, 15 (20%) had indeterminate ILA, and 22 (29%) had no ILD (Figure 1B; see Figure E2). Subjects indeterminate for ILA were excluded from primary analyses in both cohorts; more details and supplemental analyses including these individuals are detailed in the online supplement. Characteristics of BRASS and ACR subjects are summarized in Table 1. In comparing those with a spectrum of RA-ILD in the BRASS and ACR cohorts, BRASS subjects were more likely to be on medication (steroid, methotrexate, tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors) and had higher anti-CCP titers. There was no statistical difference in baseline demographics, RF, or PFT parameters (see Table E1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment in BRASS (A) and ACR (B) cohorts. A flow diagram of study enrollment divides participants into groups according to presence and subtype of interstitial lung disease. ACR = American College of Rheumatology; BRASS = Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; CT = computed tomography; HRCT = high-resolution computed tomography; ILD = interstitial lung disease; RA = rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of BRASS and ACR Subjects Stratified by Severity of RA-ILD, Excluding Indeterminate Subjects*

| BRASS Cohort |

ACR Cohort |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No RA-ILD (n = 29 [39%]) | Subclinical RA-ILD (n = 29 [39%]) | Clinically Evident RA-ILD (n = 17 [23%]) | No RA-ILD (n = 22 [36%]) | Subclinical RA-ILD (n = 18 [25%]) | Clinically Evident RA-ILD (n = 21 [29%]) |

| Demographics |

||||||

| Age, yr | 53 ± 12 | 68 ± 10† | 65 ± 10† | 50 ± 8 | 65 ± 8† | 64 ± 14† |

| Sex, female | 28 (97%) | 23 (79%) | 13 (76%)‡ | 16 (76%) | 13 (72%) | 12 (57%) |

| Race, white | 27 (93%) | 25 (89%) | 14 (82%) | 15 (71%) | 4 (22%) | 14 (67%) |

| Pack-years of smoking | 9 ± 17 | 25 ± 38† | 14 ± 19 | 4 ± 9 | 6 ± 8 | 21 ± 30‡ |

| Ever-smoker | 12 (41%) | 20 (69%)‡ | 9 (53%) | 8 (42%) | 8 (44%) | 11 (52%) |

| Medication use (ever) | ||||||

| Steroid | 24 (83%) | 27 (93%) | 16 (94%) | 15 (68%) | 12 (67%) | 9 (43%) |

| Methotrexate | 22 (76%) | 25 (86%) | 12 (71%) | 14 (67%) | 11 (65%) | 12 (57%) |

| TNF-α inhibitor | 16 (55%) | 17 (59%) | 15 (88%)† | 2 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (29%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||||||

| RF | 114 ± 186 | 346 ± 665‡ | 204 ± 232‡ | 144 ± 357 | 241 ± 407 | 418 ± 783 |

| Anti-CCP | 83 ± 113 | 182 ± 126† | 197 ± 148† | 155 ± 151 | 142 ± 160 | 87 ± 122 |

| Pulmonary function testing | n = 12 | n = 15 | n = 13 | n = 18 | n = 12 | n = 21 |

| FEV1, % of predicted | 90 ± 19 | 76 ± 23† | 69 ± 27‡ | 100 ± 21 | 84 ± 14† | 73 ± 24† |

| FVC, % of predicted | 90 ± 16 | 80 ± 19‡ | 70 ± 27‡ | 101 ± 14 | 82 ± 14† | 71 ± 23† |

| DlCO, % of predicted | 74 ± 18 | 69 ± 13 | 57 ± 23 | 84 ± 19 | 61 ± 19† | 53 ± 17† |

Definition of abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology; BRASS = Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; CCP = cyclic citrullinated peptides; DlCO = diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; RA-ILD = rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease; RF = rheumatoid factor; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α.

Data are given as n (%) or mean ± SD where appropriate. Prebronchodilator pulmonary function measurements presented.

Data missing: BRASS: race (n = 1), pack-years of smoking (n = 10), RF (n = 4), anti-CCP (n = 2), DlCO (n = 20). ACR: sex/race (n = 1), ever-smoker (n = 3), pack-years of smoking (n = 9), methotrexate use (n = 2), RF (n = 12), DlCO (n = 13).

Patient characteristics of those with varying severities of RA-ILD have been previously published (18, 25); this table is specific to those subjects who were included in this study; of note, in the BRASS cohort, individuals with interstitial lung abnormalities on high-resolution computed tomography scan, but who reported a previous history of pulmonary fibrosis, have now been included in the clinically evident RA-ILD phenotype.

P ≤ 0.05 when compared with No ILD.

P ≤ 0.10 when compared with No ILD.

BRASS Cohort

Clinical risk factors

Based on univariate analyses, older age, male sex, and ever-smoking were associated with RA-ILD (Table 1). The AUCs for these three demographic variables of interest ranged from 0.59 to 0.80 for RA-ILD, with age having the strongest association (Table 2). A combination of these clinical risk factors had an AUC of 0.84 for the spectrum of RA-ILD. In clinically evident RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.56 to 0.77 with a combined AUC of 0.80; in subclinical RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.59 to 0.82 with a combined AUC of 0.86 (see Figure E3).

Table 2.

ROC Curves of Clinical Risk Factors, Autoantibodies, and Investigational Biomarkers for the Spectrum of RA-ILD in the BRASS and ACR Cohorts

| Variable | BRASS |

ACR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subclinical RA-ILD AUC | Clinically Evident RA-ILD AUC | Spectrum of RA-ILD AUC | Subclinical RA-ILD AUC | Clinically Evident RA-ILD AUC | Spectrum of RA-ILD AUC | |

| Age | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| Sex | 0.59 | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.60 | 0.56 |

| Smoking history | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.56 |

| Age, sex, smoking history | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.84 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| RF | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| Anti-CCP | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.60 |

| RF, Anti-CCP | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.69 |

| Age, sex, smoking history, RF, anti-CCP | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 0.89 |

| MMP7 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.83 |

| PARC | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| SP-D | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.91 |

| Combinatorial signature | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| Age, sex, smoking history, RF, anti-CCP, combinatorial signature | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Definition of abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology; AUC = area under the curve; BRASS = Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; CCP = cyclic citrullinated peptides; MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; PARC = pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine; RA-ILD = rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease; RF = rheumatoid factor; ROC = receiver operating characteristic; SP-D = surfactant protein D.

Autoantibodies

Levels of RF were significantly increased in RA-ILD with higher levels in subclinical disease than clinically evident disease (Table 1). Levels of anti-CCP significantly increased with severity of RA-ILD. The AUCs for RF and anti-CCP were 0.65 and 0.75 for RA-ILD, respectively (Table 2). When adding these autoantibodies to the clinical risk factors, the AUC increased to 0.88 for the spectrum of RA-ILD in BRASS (P = 0.25 for the difference between the curves). The combined AUC was 0.86 for clinically evident RA-ILD (P = 0.26) and 0.89 for subclinical RA-ILD (P = 0.27) (see Figure E4). When dichotomizing age, RF, and anti-CCP, the ROC curve AUCs followed similar, but attenuated, trends (see Table E2).

Investigational biomarkers

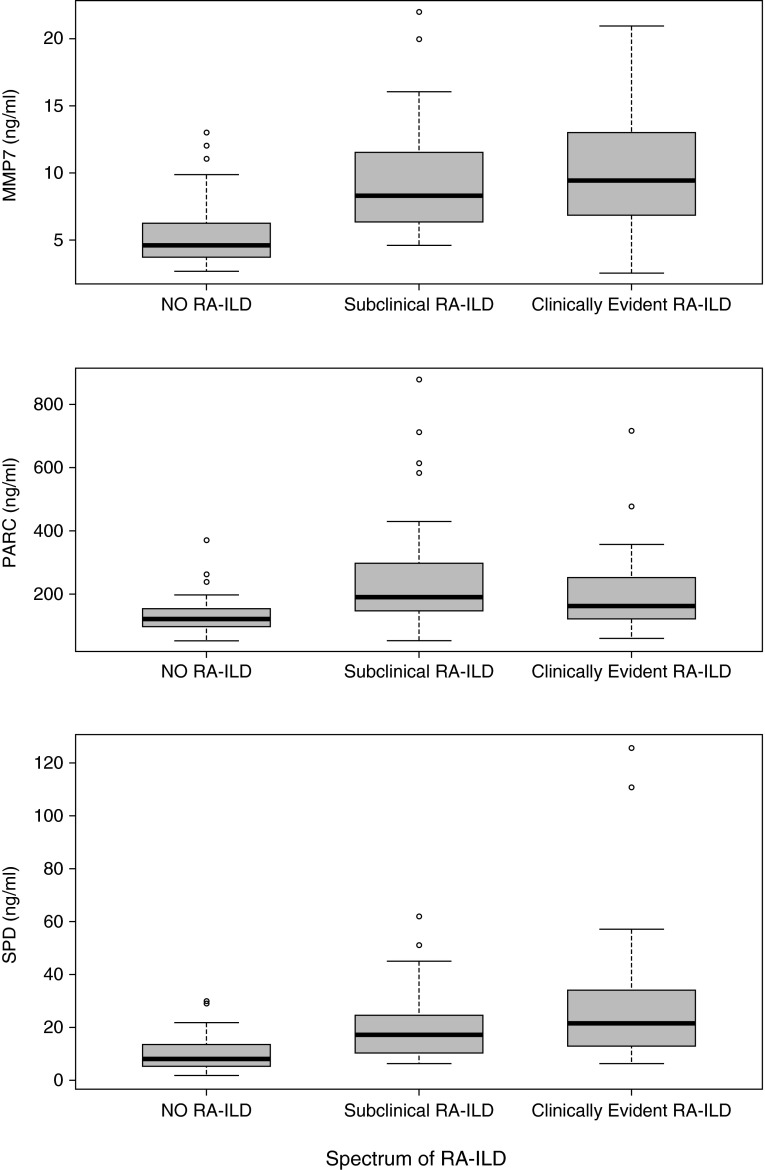

In BRASS, levels of MMP7 and SP-D significantly increased with severity of RA-ILD; PARC levels peaked in subclinical RA-ILD (Table 3). MMP7 and SP-D were significantly associated with clinically evident RA-ILD based on unadjusted logistic regression (see Table E3). After adjusting for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction, only MMP7 remained significant (P < 0.017). For subclinical RA-ILD, MMP7, PARC, and SP-D were all significantly increased in BRASS, and all biomarkers remained significant after Bonferroni correction (see Table E3). Multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusting for age, sex, smoking, RF, and CCP in both clinically significant and subclinical RA-ILD are presented in Table E3. When adjusting for all five confounders, MMP7 and PARC remained statistically significant.

Table 3.

Biomarker Levels in a Spectrum of RA-ILD in BRASS and ACR Cohorts

| BRASS Cohort |

ACR Cohort |

Combined Cohort |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No RA-ILD (n = 29) | Subclinical RA-ILD (n = 29) | Clinically Evident RA-ILD (n = 17) | No RA-ILD (n = 22) | Subclinical RA-ILD (n = 18) | Clinically Evident RA-ILD (n = 21) | No RA-ILD (n = 51) | Subclinical RA-ILD (n = 47) | Clinically Evident RA-ILD (n = 38) | |

| MMP7 | 5.7 ± 2.5 | 9.1 ± 3.3* | 10.4 ± 3.2* | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 10.0 ± 5.4* | 9.3 ± 5.0* | 5.3 ± 2.4 | 9.4 ± 4.2* | 9.8 ± 4.3* |

| PARC | 132 ± 63 | 277 ± 183* | 169 ± 72* | 129 ± 49 | 217 ± 141* | 225 ± 157* | 131 ± 57 | 254 ± 169* | 200 ± 128* |

| SP-D | 11.9 ± 7.9 | 20.6 ± 12.0* | 27.5 ± 28.7* | 7.1 ± 3.1 | 18.4 ± 13.7* | 31.2 ± 24.1* | 9.8 ± 6.7 | 19.8 ± 12.6* | 29.5 ± 26.0* |

Definition of abbreviations: ACR = American College of Rheumatology; BRASS = Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; PARC = pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine; RA-ILD = rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease; SP-D = surfactant protein D.

Data are given as mean ± SD.

P ≤ 0.05 when compared with no interstitial lung abnormalities.

In RA-ILD, AUCs for the three investigational biomarkers ranged from 0.75 to 0.86; a combination of these biomarkers was 0.92 (Table 2). In clinically evident RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.69 to 0.90 with a combined AUC of 0.92; in subclinical RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.74 to 0.86 with a combined AUC of 0.94 (see Figure E5).

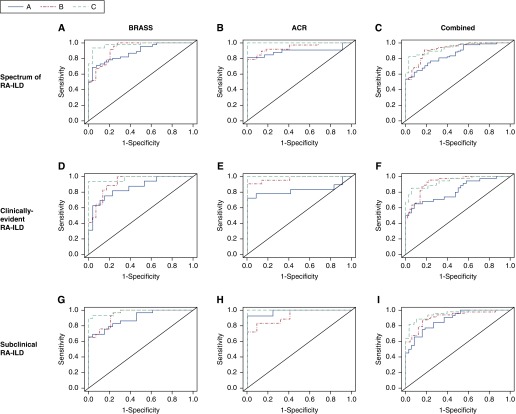

Combinatorial signature

A combination of clinical risk factors and autoantibodies is strongly associated with RA-ILD, including both clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD. Importantly the addition of the three investigational biomarkers MMP7, PARC, and SP-D significantly increased the AUC to 0.97 for RA-ILD in BRASS (P = 0.002 for the difference between the curves) (Table 2, Figure 2) (41). The AUC increased to 0.98 (P = 0.01) for clinically evident RA-ILD and to 0.98 (P = 0.01) for subclinical RA-ILD. To determine if our analysis was biased by subjects who had chest CT scans for evaluation of respiratory symptoms, we compared the ROC curves of our combinatorial signature in relation to CT indication (respiratory symptoms and/or history of pulmonary fibrosis [n = 24] vs. no symptoms or ILD history [n = 22]); there was no significant difference between the curves (see Table E4).

Figure 2.

A comparison of receiver operating characteristic curves for the spectrum of RA-ILD in BRASS, ACR, and combined cohorts. A: Age, sex, ever-smoker, RF, anti-CCP. B: MMP7, PARC, SP-D. C: Age, sex, ever-smoker, RF, anti-CCP, MMP7, PARC, SP-D. (A) Spectrum of RA-ILD in BRASS. A: AUC 0.88, B: AUC 0.92, C: AUC 0.97; A versus B, AUC increases 0.04, P = 0.2; A versus C, AUC increases 0.09, P = 0.002. (B) Spectrum of RA-ILD in ACR. A: AUC 0.89, B: AUC 0.95, C: AUC 1.00; A versus B, AUC increases 0.05, P = 0.18; A versus C, AUC increases 0.11, P = 0.016. (C) Spectrum of RA-ILD in combined. A: AUC 0.85, B: AUC 0.92, C: AUC 0.94; A versus B, AUC increases 0.07, P = 0.061; A versus C, AUC increases 0.09, P = 0.002. (D) Clinically evident RA-ILD in BRASS. A: AUC 0.86, B: AUC 0.92, C: AUC 0.98; A versus B, AUC increases 0.06, P = 0.2; A versus C, AUC increases 0.12, P = 0.01. (E) Clinically evident RA-ILD in ACR. A: AUC 0.82, B: AUC 0.97, C: AUC 1.00; A versus B, AUC increases 0.15, P = 0.045; A versus C, AUC increases 0.18, P = 0.017. (F) Clinically evident RA-ILD in combined. A: AUC 0.82, B: AUC 0.92, C: AUC 0.94; A versus B, AUC increases 0.10, P = 0.033; A versus C, AUC increases 0.12, P = 0.002. (G) Subclinical RA-ILD in BRASS. A: AUC 0.89, B: AUC 0.94; C: AUC 0.98; A versus B, AUC increases 0.05, P = 0.2; A versus C, AUC increases 0.09, P = 0.01. (H) Subclinical RA-ILD in ACR. A: AUC 0.98, B: AUC 0.93; C: AUC 1.00; A versus B, AUC decreases 0.05, P = 0.103; A versus C, AUC increases 0.02, P = 0.19. (I) Subclinical RA-ILD in combined. A: AUC 0.88, B: AUC 0.91; C: AUC 0.95; A versus B, AUC increases 0.03, P = 0.24; A versus C, AUC increases 0.07, P = 0.007. ACR = American College of Rheumatology; AUC = area under the curve; BRASS = Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study; CCP = cyclic citrullinated peptides; MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; PARC = pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine; RA-ILD = rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease; RF = rheumatoid factor; SP-D = surfactant protein D.

ACR Cohort

Clinical risk factors

Based on univariate analyses, older age and ever-smoking were associated with RA-ILD (Table 1). The AUCs ranged from 0.56 to 0.83 for RA-ILD, with age also having the strongest association in this cohort (Table 2). A combination of these clinical risk factors was 0.89 for the spectrum of RA-ILD. In clinically evident RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.55 to 0.78, with a combined AUC of 0.84; in subclinical RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.52 to 0.90 with a combined AUC of 0.94 (see Figure E3).

Autoantibodies

Although levels of RF increased with severity of RA-ILD, RF and anti-CCP levels were not significantly increased in the validation cohort (Table 1). The AUCs for RF and anti-CCP were 0.59 and 0.60 for RA-ILD, respectively (Table 2). When adding these autoantibodies to the clinical risk factors, the AUC increased to 0.89 for the spectrum of RA-ILD (P = 0.45 for the difference between the curves). The combined AUC was 0.82 for clinically evident RA-ILD (P = 0.43), and 0.98 for subclinical RA-ILD (P = 0.16) (see Figure E4).

Investigational biomarkers

In ACR, levels of PARC and SPD significantly increased with severity of RA-ILD; MMP7 levels peaked in subclinical RA-ILD (Table 3). MMP7, PARC, and SP-D were all significantly increased in both clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD based on unadjusted logistic regression (see Table E3). After adjusting for multiple testing using the Bonferroni correction, MMP7 and SPD remained significant. Multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusting for age, sex, smoking, RF, and CCP are presented in Table E3. No biomarkers were significant when adjusting for all five confounders in either clinically evident or subclinical RA-ILD.

The AUCs for these three investigational biomarkers ranged from 0.70 to 0.91 for RA-ILD. A combination of these biomarkers was 0.95 for the spectrum of RA-ILD (Table 2). In clinically evident RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.69 to 0.93 with a combined AUC of 0.97; in subclinical RA-ILD, the AUCs ranged from 0.71 to 0.87 with a combined AUC of 0.93 (see Figure E5). Based on these analyses, MMP7 emerged as the strongest individual biomarker of RA-ILD in BRASS and ACR cohorts, including clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD.

Combinatorial signature

Similar to the BRASS cohort, although a combination of clinical risk factors and autoantibodies was very strongly associated with RA-ILD in ACR, a combination of the three investigational biomarkers MMP7, PARC, and SP-D significantly increased the AUC to 1.00 for the spectrum of RA-ILD in the ACR cohort (P = 0.016 for the difference between the curves) (Table 2). The AUC was 1.00 (P = 0.017) for clinically evident RA-ILD and 1.00 (P = 0.19) for subclinical RA-ILD (Figure 2).

Combined Analysis of BRASS and ACR Cohorts

Baseline variables of the spectrum of RA-ILD in the combined BRASS and ACR cohorts are presented in Table E1. Based on unadjusted logistic regression, age, sex, smoking, and RF were strongly associated with the spectrum of RA-ILD, but anti-CCP was not strongly associated with RA-ILD. MMP7, PARC, and SP-D were also significantly associated with the spectrum of RA-ILD severity (Figure 3, Table 3; see Table E5). A combination of the clinical risk factors, RF, and anti-CCP had an AUC of 0.85 for RA-ILD (0.82 for clinically evident disease and 0.88 for subclinical disease) (Figure 2; see Figures E3 and E4 and Table E6). A signature composed of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D had an AUC of 0.92 for RA-ILD, P = 0.061 when compared with the AUC for clinical risk factors, RF, and anti-CCP (0.92 for clinically evident disease, P = 0.033; 0.91 for subclinical disease, P = 0.24) (Figure 2; see Figure E5 and Tables E6A and E6B). A combinatorial signature composed of clinical risk factors, RF, anti-CCP, and experimental biomarkers had an AUC of 0.94 for RA-ILD, P = 0.002 when compared with the AUC for clinical risk factors, RF, and anti-CCP (0.94 for clinically evident disease, P = 0.002; 0.95 for subclinical disease, P = 0.007) (Figure 2; see Table E6A).

Figure 3.

Serum levels of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D across the spectrum of RA-ILD in the combined Brigham and Women's Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study and American College of Rheumatology cohorts. Box-and-whisker plot depicting levels of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D in serum samples of patients with no RA-ILD, subclinical RA-ILD, and clinically evident RA-ILD. Circles represent outliers. P values identify statistically significant differences between subgroups as determined by unadjusted logistic regression analyses. MMP7: Subclinical RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P < 0.0001; clinically evident RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P < 0.0001. PARC: Subclinical RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P = 0.0001; clinically evident RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P = 0.0031. SP-D: Subclinical RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P = 0.0001; clinically evident RA-ILD versus no RA-ILD, P < 0.0001. MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; PARC = pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine; RA-ILD = rheumatoid arthritis–associated interstitial lung disease; SP-D = surfactant protein D.

Diagnostic Test for the Identification of Subclinical RA-ILD

Using logistic regression, we derived the following formula for the identification of subclinical RA-ILD in the BRASS cohort: risk score = 0.38 × age − 6.4 × sex − 2.3 × ever-smoker − 0.0005 × RF + 0.0026 × CCP + 0.65 × MMP7 + 0.15 × SPD + 0.024 × PARC. The cutoff with the optimal combination of sensitivity and specificity was 28.2 (i.e., a patient was most likely to have subclinical RA-ILD with a risk score > 28.2). We subsequently evaluated this algorithm in ACR RA subjects without clinically evident ILD and found that it correctly identified subclinical RA-ILD with a sensitivity of 0.87 and specificity of 0.92, yielding a positive likelihood ratio of 10.4 and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.15.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a combination of clinical risk factors (older age, male sex, ever-smoking) and autoantibodies (RF, anti-CCP) is strongly associated with the presence of clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD. An investigational biomarker signature composed of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D significantly enhances the ability to identify individuals both independently and in combination with the previously mentioned variables. Importantly, this combinatorial signature composed of clinical risk factors, autoantibodies, and investigational biomarkers was tested in two independent RA cohorts composed of individuals with a spectrum of clinically evident and subclinical ILD.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the association of RA-ILD with older age, male sex, and smoking status (17–21). In addition, our group and others have shown that elevated levels of RF and anti-CCP are associated with clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD (17, 18, 32–35). Although this study shows that a combination of clinical risk factors, RF, and anti-CCP identifies the presence of RA-ILD, it is important to note that RF and anti-CCP were weakly associated with the presence of RA-ILD, especially in the ACR cohort.

Increased levels of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D have been previously associated with disease progression and reduced survival in patients with IPF (22–24, 27–31). Given the high percentage of individuals with RA-ILD with a radiologic or histologic usual interstitial pneumonia pattern classically observed in IPF, we hypothesized that biomarkers predictive of clinical outcomes in IPF would be associated with RA-ILD. In this study we have shown that MMP7, PARC, and SP-D blood levels are significantly increased in two independent RA cohorts. This combinatorial biomarker signature performed as well as clinical risk factors and autoantibodies and significantly enhanced the ability to identify the presence of both clinically evident and subclinical ILD when used in combination with these risk factors. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to show that a combination of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D can identify the presence of subclinical and clinically evident RA-ILD.

Despite the fact that RA individuals are at increased risk of developing ILD and the associated significant morbidity and mortality, the presence of subclinical RA-ILD is not currently detected in this population even though it may represent early stages of clinically evident RA-ILD (10, 42). This is particularly concerning given that ILA are frequently associated with respiratory symptoms and functional abnormalities in at-risk populations, such as smokers, the elderly, and individuals with RA, even when unrecognized by the patient or physician (11, 18, 43, 44). The high prevalence of both RA and smoking places these individuals at an even higher risk of developing ILD (12, 45), and continues to support the importance of smoking cessation in all patients with RA as a key component of the management of individuals at risk for ILD (10). The research outlined in this paper provides a better understanding of the clinical and molecular characteristics of subclinical RA-ILD and highlights the potential role of novel biomarkers in identifying a spectrum RA-ILD.

The high prevalence of subclinical ILD in RA and the poor clinical outcomes associated with the development of clinically evident RA-ILD highlight the need for effective methods to risk-stratify subjects with subclinical ILD. Early detection of ILD in patients with RA at risk for disease progression could lead to a meaningful change in clinical outcomes given the availability of numerous disease-modifying agents, biologics (3), and novel antifibrotic therapies (46). Although our study did not test the association of molecular features with disease progression, we have identified investigational biomarkers that are strongly associated with the presence of RA-ILD. Importantly in patients with IPF, MMP7, PARC, and SPD have been shown to predict disease progression and survival (22–24, 27–31). Furthermore, similar to our findings in RA-ILD, these biomarkers have been shown to improve the predictive ability of well-established IPF clinical risk factors (i.e., older age, male sex, and ever-smoking) (23, 28). In fact, application of a diagnostic algorithm combining these clinical risk factors with autoantibodies and investigational biomarkers yielded strong positive and negative likelihood ratios for subclinical ILD.

This suggests that a clinical prediction model (47) incorporating these variables, such as the BODE index (48) or ILD GAP model (49, 50), has the potential to identify patients with RA at risk for developing ILD. To achieve this important goal, the study of large RA cohorts with detailed clinical phenotyping and longitudinal follow-up will be required. These future studies could ultimately lead to a better understanding of the significance of subclinical RA-ILD and the rate of progression, and will therefore have the potential to positively impact clinical outcomes of patients with RA with progressive lung fibrosis.

Our study has several limitations. First, the BRASS cohort has a limited number of subjects with all data available, considerable variation in the timing of studies, and significant bias caused by the selection of subjects with clinically indicated CT scans (18). To address the possible bias caused by clinically indicated CT scans, we subdivided CT scans by indication (symptoms and/or ILD history) and found no significant difference between the ROC curves. This suggests that the findings in the BRASS cohort may be caused primarily by the radiologic changes seen on CT scan rather than the symptoms prompting the CT scan, and therefore more generalizable. In addition, to address the limitations of using an enriched derivation cohort and to determine the ability of our signature to identify the presence of RA-ILD in an unselected RA population, we validated our findings in the ACR cohort, in which subjects without a prior diagnosis of ILD underwent chest CT imaging for research purposes only, thus providing an unbiased subset of subjects with RA without known ILD. Second, although our findings suggest that clinical risk factors and autoantibodies alone may identify the presence of RA-ILD in two independent cohorts, it is possible that the performance of these risk factors will decrease in a larger cohort, particularly when age, RF, and anti-CCP are stratified and incorporated into a clinical prediction model.

Third, although the investigational biomarker signature (MMP7, PARC, and SP-D) was tested in an independent cohort, there are limitations of validity inherent to all experimental biomarkers, especially reproducibility and generalizability (51). Additional studies should be conducted to determine the ability of this combinatorial signature to correlate with meaningful clinical outcomes. Finally, there are additional biomarkers of interest based in the literature, such as KL-6, which were not included in this signature because they have not been shown to predict outcomes; future studies should investigate a broader array of biomarkers and other variables of interest, such as respiratory symptoms and PFTs. All of these important limitations should be addressed in subsequent prospective studies.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that clinical risk factors, autoantibodies, and a biomarker signature composed of MMP7, PARC, and SP-D identify the presence of clinically evident and subclinical RA-ILD in two independent cohorts. Our findings may facilitate earlier identification of a spectrum of RA-ILD, potentially leading to improved clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Rebecca Betensky for her statistical expertise. They also thank their collaborators in Myriad Rules Based Medicine (Ralph McDade, Karri Ballard, and Rob Bencher) and their study participants.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/NHLBI grants 1K23HL119558-01A1 (T.J.D.), R01 HL111024 (G.M.H.), U01HL105371 (I.O.R.), and P01HL114501 (I.O.R). Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study is currently sponsored by Crescendo Bioscience, UCB, and Bristol Myers Squibb.

Author Contributions: Drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content, all authors. Acquisition of the clinical data, T.J.D., A.S.P., J.C.O., M.F.G., A.T., D.K., C.F., P.F.D., C.V.O., and D.P.A. Statistical analysis and interpretation of the clinical data, T.J.D., A.S.P., H.H., M.N., M.E.W., G.W., S.Y.E.-C., G.M.H., A.M.K.C., N.A.S., D.P.A., and I.O.R. Administrative, technical, or material support, M.L.F. and C.K.I.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201411-1950OC on March 30, 2015

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2010;376:1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001-2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:460–464. doi: 10.1002/acr.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M, et al. American College of Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–784. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young A, Koduri G, Batley M, Kulinskaya E, Gough A, Norton S, Dixey J Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) group. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:350–357. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown KK. Rheumatoid lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:443–448. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-045MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle TJ, Lee JS, Dellaripa PF, Lederer JA, Matteson EL, Fischer A, Ascherman DP, Glassberg MK, Ryu JH, Danoff SK, et al. A roadmap to promote clinical and translational research in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2014;145:454–463. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabbay E, Tarala R, Will R, Carroll G, Adler B, Cameron D, Lake FR. Interstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:528–535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9609016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bongartz T, Nannini C, Medina-Velasquez YF, Achenbach SJ, Crowson CS, Ryu JH, Vassallo R, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Incidence and mortality of interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1583–1591. doi: 10.1002/art.27405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, Fischer A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, Murphy J, Cohen M, Raghu G, Brown KK. Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease-associated mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:372–378. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0622OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle TJ, Hunninghake GM, Rosas IO. Subclinical interstitial lung disease: why you should care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1147–1153. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1420PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, Ross JC, Estépar RS, Lynch DA, Brehm JM, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:897–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gochuico BR, Avila NA, Chow CK, Novero LJ, Wu HP, Ren P, MacDonald SD, Travis WD, Stylianou MP, Rosas IO. Progressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:159–166. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawson JK, Fewins HE, Desmond J, Lynch MP, Graham DR. Predictors of progression of HRCT diagnosed fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:517–521. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim EJ, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern. Chest. 2009;136:1397–1405. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Assayag D, Elicker BM, Urbania TH, Colby TV, Kang BH, Ryu JH, King TE, Collard HR, Kim DS, Lee JS. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: radiologic identification of usual interstitial pneumonia pattern. Radiology. 2014;270:583–588. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assayag D, Lubin M, Lee JS, King TE, Collard HR, Ryerson CJ. Predictors of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease. Respirology. 2014;19:493–500. doi: 10.1111/resp.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly CA, Saravanan V, Nisar M, Arthanari S, Woodhead FA, Price-Forbes AN, Dawson J, Sathi N, Ahmad Y, Koduri G, et al. British Rheumatoid Interstitial Lung Network. Rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: associations, prognostic factors and physiological and radiological characteristics. A large multicentre UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1676–1682. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyle TJ, Dellaripa PF, Batra K, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Hatabu H, Nishino M, Weinblatt ME, Ascherman DP, Washko GR, et al. Functional impact of a spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 2014;146:41–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weyand CM, Schmidt D, Wagner U, Goronzy JJ. The influence of sex on the phenotype of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:817–822. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<817::AID-ART7>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oliver JE, Silman AJ. Risk factors for the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006;35:169–174. doi: 10.1080/03009740600718080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saag KG, Cerhan JR, Kolluri S, Ohashi K, Hunninghake GW, Schwartz DA. Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:463–469. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.8.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosas IO, Richards TJ, Konishi K, Zhang Y, Gibson K, Lokshin AE, Lindell KO, Cisneros J, Macdonald SD, Pardo A, et al. MMP1 and MMP7 as potential peripheral blood biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e93. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards TJ, Kaminski N, Baribaud F, Flavin S, Brodmerkel C, Horowitz D, Li K, Choi J, Vuga LJ, Lindell KO, et al. Peripheral blood proteins predict mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:67–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song JW, Do KH, Jang SJ, Colby TV, Han S, Kim DS. Blood biomarkers MMP-7 and SP-A: predictors of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2013;143:1422–1429. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Doyle TJ, Liu Y, Aggarwal R, Wang X, Shi Y, Ge SX, Huang H, Lin Q, Liu W, et al. Biomarkers of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum (Munch) 2015;67:28–38. doi: 10.1002/art.38904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasse A, Pechkovsky DV, Toews GB, Schäfer M, Eggeling S, Ludwig C, Germann M, Kollert F, Zissel G, Müller-Quernheim J. CCL18 as an indicator of pulmonary fibrotic activity in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1685–1693. doi: 10.1002/art.22559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasse A, Probst C, Bargagli E, Zissel G, Toews GB, Flaherty KR, Olschewski M, Rottoli P, Müller-Quernheim J. Serum CC-chemokine ligand 18 concentration predicts outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:717–723. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1201OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinder BW, Brown KK, McCormack FX, Ix JH, Kervitsky A, Schwarz MI, King TEJ., Jr Serum surfactant protein-A is a strong predictor of early mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2009;135:1557–1563. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi H, Fujishima T, Koba H, Murakami S, Kurokawa K, Shibuya Y, Shiratori M, Kuroki Y, Abe S. Serum surfactant proteins A and D as prognostic factors in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their relationship to disease extent. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1109–1114. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9910080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlo NP, van Moorsel CH, Ruven HJ, Zanen P, van den Bosch JM, Grutters JC. Surfactant protein-D predicts survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene KE, King TEJ, Jr, Kuroki Y, Bucher-Bartelson B, Hunninghake GW, Newman LS, Nagae H, Mason RJ. Serum surfactant proteins-A and -D as biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:439–446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00081102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luukkainen R, Saltyshev M, Pakkasela R, Nordqvist E, Huhtala H, Hakala M. Relationship of rheumatoid factor to lung diffusion capacity in smoking and non-smoking patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 1995;24:119–120. doi: 10.3109/03009749509099296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inui N, Enomoto N, Suda T, Kageyama Y, Watanabe H, Chida K. Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies in lung diseases associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:1074–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harlow L, Rosas IO, Gochuico BR, Mikuls TR, Dellaripa PF, Oddis CV, Ascherman DP. Identification of citrullinated hsp90 isoforms as novel autoantigens in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:869–879. doi: 10.1002/art.37881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giles JT, Danoff SK, Sokolove J, Wagner CA, Winchester R, Pappas DA, Siegelman S, Connors G, Robinson WH, Bathon JM. Association of fine specificity and repertoire expansion of anticitrullinated peptide antibodies with rheumatoid arthritis associated interstitial lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1487–1494. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyle TJ, Patel AS, Hatabu H, Nishino M, Wu G, Osorio JC, Golzarri M, Magaldi EN, Chu SG, Frits ML, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease risk-stratification is potentially enhanced by peripheral blood biomarkers [abstract]. Presented at the International Colloquium on Lung & Airway Fibrosis. 2014. Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, Canada. p. 106. September 20–24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iannaccone CK, Lee YC, Cui J, Frits ML, Glass RJ, Plenge RM, Solomon DH, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA. Using genetic and clinical data to understand response to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapy: data from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:40–46. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, Ross JC, Umeoka S, Diaz A, Sciurba FC, Hunninghake GM, San José Estépar R, Silverman EK, et al. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol. 2010;17:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorelik E, Landsittel DP, Marrangoni AM, Modugno F, Velikokhatnaya L, Winans MT, Bigbee WL, Herberman RB, Lokshin AE. Multiplexed immunobead-based cytokine profiling for early detection of ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:981–987. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stears RL, Martinsky T, Schena M. Trends in microarray analysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:140–145. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosas IO, Dellaripa PF, Lederer DJ, Khanna D, Young LR, Martinez FJ. Interstitial lung disease: NHLBI workshop on the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:S169–S177. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-429LD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle TJ, Washko GR, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, Divo MJ, Celli BR, Sciurba FC, Silverman EK, et al. COPDGene Investigators. Interstitial lung abnormalities and reduced exercise capacity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:756–762. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1618OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunninghake GM, Hatabu H, Okajima Y, Gao W, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Nishino M, Araki T, Zazueta OE, Kurugol S, et al. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2192–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saag KG, Kolluri S, Koehnke RK, Georgou TA, Rachow JW, Hunninghake GW, Schwartz DA. Rheumatoid arthritis lung disease: determinants of radiographic and physiologic abnormalities. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1711–1719. doi: 10.1002/art.1780391014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King TE, Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, Gorina E, Hopkins PM, Kardatzke D, Lancaster L, et al. ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steyerberg E. New York: Springer; 2009. Clinical prediction models: a practical approach to development, validation, and updating. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, Ley B, Lee JS, Mooney JJ, Jones KD, Elicker BM, Wolters PJ, Koth LL, King TE, Jr, et al. Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: the ILD-gap model. Chest. 2014;145:723–728. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ley B, Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, Ryu JH, Tomassetti S, Lee JS, Poletti V, Buccioli M, Elicker BM, Jones KD, et al. A multidimensional index and staging system for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:684–691. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doyle TJ, Pinto-Plata V, Morse D, Celli BR, Rosas IO. The expanding role of biomarkers in the assessment of smoking-related parenchymal lung diseases. Chest. 2012;142:1027–1034. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]