Abstract

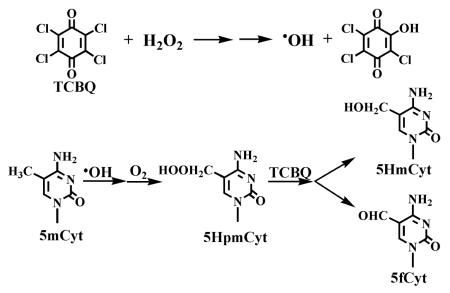

Halogenated quinones are a class of carcinogenic intermediates and newly identified chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water. We found recently that the highly reactive and biologically important hydroxyl radical (•OH) can be produced by halogenated quinones and H2O2 independent of transition metal ions. However, it is not clear whether these quinoid carcinogens and H2O2 can oxidize the nucleoside 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5mdC) to its methyl oxidation products, and if so, what is the underlying molecular mechanism. Here we show that three methyl oxidation products 5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-, and 5-formyl-2′-deoxycytidine could be produced when 5mdC was treated with tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (TCBQ) and H2O2. The formation of the oxidation products was markedly inhibited by typical •OH scavengers and under anaerobic condition. Analogous effects were observed with other halogenated quinones and the classic Fenton system. Based on these data, we proposed that the oxidation of 5mdC by TCBQ/H2O2 might be through the following mechanism: •OH produced by TCBQ/H2O2 may first abstract hydrogen from the methyl group of 5mdC, leading to the formation of 5-(2′-deoxycytidylyl)methyl radical, which may combine with O2 to form peroxyl radical. The unstable peroxyl radical transforms into the corresponding hydroperoxide 5HpmdC, which reacts with TCBQ and results in the formation of 5HmdC and 5fdC. This is the first report that halogenated quinoid carcinogens and H2O2 can induce potent methyl oxidation of 5mdC via a metal-independent mechanism, which may partly explain their potential carcinogenicity.

Keywords: Halogenated quinones, hydroxyl radical, 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine, 5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine, 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine, 5-formyl-2′-deoxycytidine

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Halogenated quinones are a class of toxicological intermediates which can cause acute nephrotoxicity, hepatoxicity, and carcinogenesis [1, 2]. They have also been found as reactive intermediates or products in processes used to oxidize or degrade polyhalogenated persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in a variety of chemical and enzymatic systems [3-8]. More recently, several polyhalogenated quinones, which are suspected bladder carcinogens, were observed as new chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water [7, 8]. Tetrachloro-1, 4-benzoquinone (TCBQ, also called p-chloranil) is one of the major genotoxic and carcinogenic quinoid metabolites of the widely used wood preservative pentachlorophenol (PCP). PCP has been found in over 20% of the National Priorities List sites identified by the U.S. EPA and classified as a group 2B environmental carcinogen [3].

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is an extremely reactive oxidant, important in biology, medicine, chemistry and environmental science [3, 9-11]. In biology, •OH is considered as the most reactive and harmful of the so-called reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause DNA and other macromolecule oxidation [9-11]. Cancer, Parkinson′s disease and arthritis are but a few of the ailments that are related to •OH generation [9]. One of the most widely accepted mechanisms for •OH production is via the transition metal-catalyzed Fenton reaction [3, 9-11]. Recently, however, we found that •OH could be produced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with TCBQ and other halogenated quinones independently of transition metal ions [12, 13]. A novel nucleophilic substitution and homolytic decomposition reaction mechanism has been proposed [3, 13]. We also found that alkoxyl and carbon-centered quinone ketoxy radicals could be generated via a similar mechanism by halogenated quinone mediated decomposition of organic hydroperoxides [14-16].

It is well-known that the genetic material is constructed from the four DNA nucleosides, and 5-methylcytosine (5mCyt) is often considered to be the fifth base of the genome. Cytosine residues in DNA are methylated enzymatically, usually in the CpG dinucleotide [17]. In humans, approximately 5% cytosine residues are methylated, which play an important role in regulation of transcription during cellular differentiation and silencing of invading viral genomes [18, 19]. The reverse of this process, DNA demethylation is equally important for cleaning genomic slate during embryogenesis or achieving rapid reactivation of silenced gene [20]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that Tet family of proteins have the capacity to convert 5mCyt not only to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5HmCyt), but also to 5-formylcytosine (5fCyt) and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caCyt) in vitro [21-23]. In addition, there is evidence for the presence of 5fCyt and 5caCyt in the genomic DNA of mouse ES cells [23-26]. Emerging evidence has shown that 5mCyt derivatives are involved in normal development as well as in many diseases [27-30].

It has been shown that 5HmCyt and 5fCyt were produced when 5mCyt was treated by Fenton-type reagents or after UV-light exposure [31-34]. However, it is still not clear whether halogenated quinones and H2O2 can oxidize 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5mdC) to form its methyl oxidation products or not; and if so, what is the possible underlying mechanism. Therefore, in the present study we addressed the following questions: (i) Can 5HmdC, 5fdC or other methyl oxidation products be produced by halogenated quinones and H2O2; (ii) If so, is the oxidation dependent on •OH production; (iii) What is the molecular mechanism underlying 5mdC oxidation; and (iv) What are the potential biological and environmental implications?

Materials and Methods

Materials

Analytical grade chemicals, HPLC grade organic solvents, and chelex-100 treated buffer were used throughout. 5mdC purchased from TCI (Shanghai, China) was used as received. All halogenated quinones were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was purchased from Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China). 5HmdC and 5fdC purchased from Berry & Associates, Inc. (Dexter, MI) were used as standard.

Reactions of XBQs, H2O2, and 5mdC

The basic system used in the study consisted of 0.1mM XBQs dissolved in acetonitrile (final acetonitrile concentration in the reaction mixture, 2%), 1.0mM H2O2 and 2.0mM 5mdC in 10mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 1h unless otherwise stated. The phosphate buffer used for all experiments was pretreated with chelex-100 ion-exchange resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, 5g/L) overnight to remove trace transition metal probably presented in phosphate buffer as contaminants. The reaction solutions were directly injected into HPLC-triple quadrupole MS system for analysis.

HPLC/triple-quadrupole mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) analysis of oxidation products of 5mdC

The HPLC separation was conducted on an Agilent 1290 series equipped with two pumps, autosampler, and solvent cabinet (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany). A reversed-phase ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6×150mm, 5μm, Agilent) was used, and the mobile phase of 10.0% methanol and 90.0% water (with 0.1% formic acid) was used for isocratic elution at a flow rate of 1.0mL/min. The eluate from the HPLC column was directly introduced into an ESI-triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6410B series, Santa Clara, CA) with flow-splitting. The mass spectrometer was operated in the positive ion mode. For Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) analysis, collision energy was performed at 5eV. The fragmentor voltage was 90V, nitrogen was used as nebulizer gas and the desolvation gas (nitrogen) was heated to 300°C and delivered at a flow rate of 9.0L/min. The capillary voltage was set at 3500V. The injection volume is 10μL for the reaction mixture containing nucleotide. Since more than 97% 5mdC could not be oxidized by the reaction, 5mdC was used as an internal standard for calibration and quantification of the formed oxidation products in the reaction mixtures in HPLC-MS/MS analysis. In addition, the characteristic daughter ion m/z 83 was used for the analysis of 5mdC (CID 5eV). The data were collected by Agilent MassHunter Data Acquisition Workstation.

Results and Discussion

Three methyl oxidation products were identified during metal-independent oxidation of 5mdC by TCBQ and H2O2

Three major oxidation products of 5mdC were observed by HPLC-MS/MS analysis, when 5mdC (2.0 mM) was incubated with the combination of TCBQ (0.1 mM) and H2O2 (1.0 mM) together, but not by either of them alone (Figure S1). Two of these products showed the same chromatographic retention time (1.7 and 4.3min), and the same MRM fragmentation pattern (m/z 258→142 and 256→140) as the authentic standard 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine (5HmdC), and 5-formyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5fdC), and therefore they were identified as 5HmdC and 5fdC, respectively.

Interestingly and unexpectedly, a new peak with the retention time at 1.8min was also observed in the HPLC profile besides 5HmdC and 5fdC. This was identified by LC/MS/MS method as the corresponding hydroperoxide, 5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine (5HpmdC), which was previously identified as one of the oxidation products during photosensitized one-electron oxidation of 5mdC [35], but was not reported when 5mC was treated by Fenton-type reagents or after UV-light exposure [31-34]. We found that 5HpmdC produced in our TCBQ/H2O2 system was the same as that produced in the photosensitized oxidation of 5mdC, since they showed the same chromatographic retention time and the same MRM fragmentation pattern (Figure S2). The high resolution MS data further confirmed that the compound is indeed 5HpmdC (experimental value: m/z = 274.10390; theoretical value: m/z = 274.10336). To our surprise, 5HpmdC, together with 5HmdC and 5fdC, could also be observed when 5mdC was oxidized by the classic Fenton system (FeIIEDTA/H2O2) in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first report that 5HpmdC could be produced by two distinct •OH-producing systems, the metal-dependent Fenton system and the metal-independent TCBQ/H2O2 system.

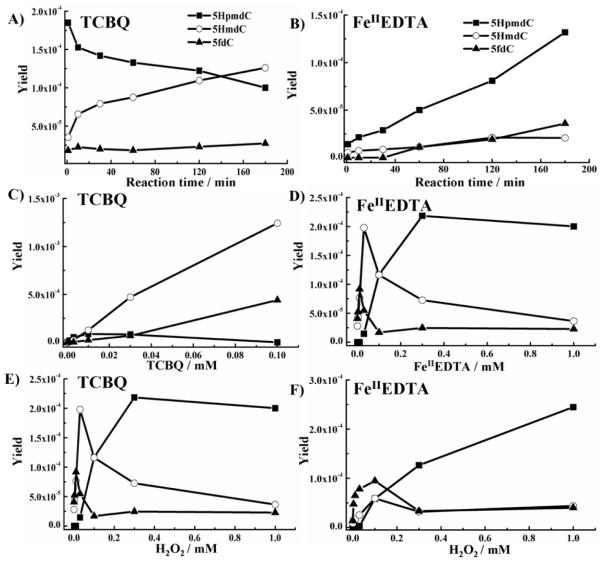

The formation of the three methyl oxidation products of 5mdC was found to be time and dose-dependent on TCBQ (or FeIIEDTA) and H2O2 (Figure 1, for details, see Supporting Information). Besides the above three methyl oxidation products, other •OH-oxidized products of 5mdC were also investigated in TCBQ/H2O2 system (see Supporting Information).

Figure 1. Time course and dose-dependent formation of methyl oxidation products of 5mdC by TCBQ (or FeIIEDTA) with H2O2.

Time-dependent formation of 5mdC oxidation products by TCBQ (A) or FeIIEDTA (B) with H2O2. Dose-dependent formation of methyl oxidation products of 5mdC on TCBQ (C) or FeIIEDTA (D). Dose-dependent formation of methyl oxidation products of 5mdC on H2O2 (E and F). The reaction solution contained 0.01mM TCBQ (or FeIIEDTA), 0.1mM H2O2 and 0.1mM 5mdC in 10mM phosphate buffer, pH7.4, at 37°C.

Both •OH and molecular oxygen (O2) played a critical role in the formation of 5mdC oxidation products by TCBQ and H2O2

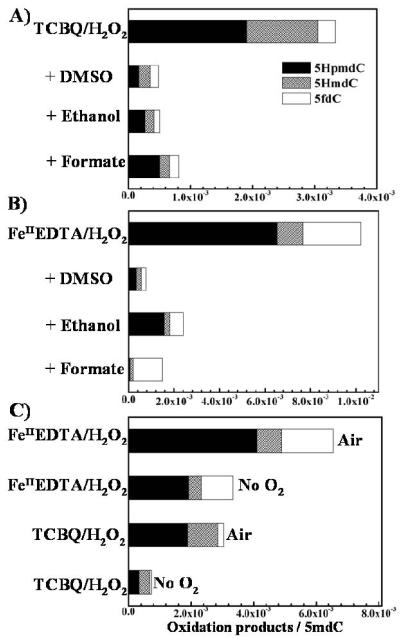

Since we have shown recently that •OH can be produced through homolytical decomposition of H2O2 by TCBQ independent of transition metal ions [12, 13], we hypothesized that •OH may play a critical role in methyl oxidation of 5mdC. To test whether •OH was involved or not, three typical •OH scavengers including DMSO, ethanol and sodium formate were chosen. We found that the three •OH scavengers can significantly suppress the oxidation of 5mdC by TCBQ and H2O2 (Figure 2A). Analogous inhibitory effects were observed in FeIIEDTA/H2O2 system (Figure 2B). These results indicate that •OH indeed played an essential role in the formation of 5mdC oxidation products.

Figure 2. Both •OH and O2 played a critical role in the formation of oxidation products of 5mdC by TCBQ/H2O2 and FeIIEDTA/H2O2.

Inhibition effect by •OH scavengers on the formation of 5mdC oxidation products by TCBQ/H2O2 (A) and FeIIEDTA/ H2O2 (B); the formation of 5mdC oxidation products under anaerobic condition by TCBQ/H2O2 and FeIIEDTA (C). The reaction solution contained 2.0mM 5mdC, 0.1mM TCBQ (or FeIIEDTA), and 1.0mM H2O2.

The most feasible pathway for •OH to oxidize the methyl group of 5mdC should be the abstraction of a hydrogen atom by •OH from the methyl group with the concomitant formation of a carbon-centered 5-(2′-deoxycytidylyl)methyl radical, which then combines with molecular oxygen (O2) to form its corresponding peroxyl radical. The unstable peroxyl radical transforms into the corresponding hydroperoxide 5HpmdC. If the above hypothesis were right, then O2 should also play an important role in the formation of the methyl oxidation products. To test whether this is the case, the same experiments were conducted in an Anaerobic Chamber. Interestingly, we found that the generation of 5mdC oxidation products in both TCBQ/H2O2 and FeIIEDTA/H2O2 system decreased markedly by 70% and 50%, respectively, under anaerobic condition (Figure 2C). These results clearly suggest that O2 is also important for the formation of 5mdC oxidation products.

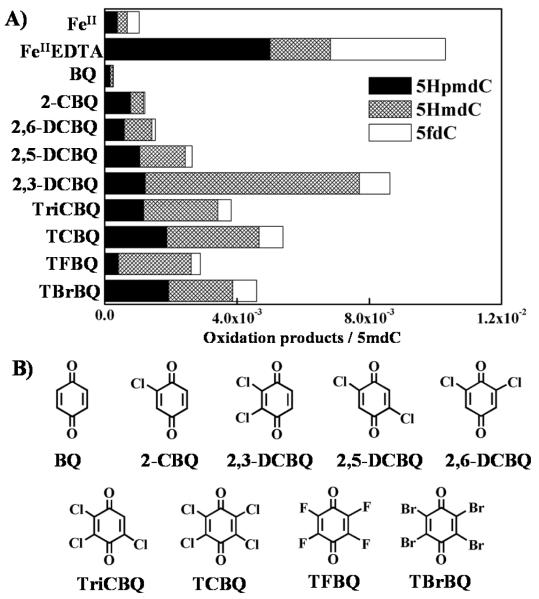

Analogous oxidation of 5mdC was also observed with other halogenated quinones

5mdC can also be effectively oxidized to 5HpmdC, 5HmdC and 5fdC when TCBQ was substituted by other XBQs. These include 2-chloro- (2-CBQ), 2,3-dichloro- (2,3-DCBQ), 2,5-dichloro- (2,5-DCBQ), 2,6-dichloro- (2,6-DCBQ), 2,3,5-trichloro- (TriCBQ), tetrafluoro- (TFBQ) and tetrabromo-1,4-benzoquinone (TBrBQ) (Figure 3). The reactivity of XBQs depends on the type, number, and position of halogen substitution, and ranks in the descending order of 2,3-DCBQ > TCBQ, TBrBQ > TriCBQ > TFBQ > 2,5-DCBQ > 2,6-DCBQ > 2-CBQ. In contrast, 1,4-benzoquinone (p-BQ) that lacks any halogen substitution induced much less oxidation products under the same experiment conditions. These results clearly indicate the importance of halogen substitution of XBQs played in the enhanced oxidation of 5mdC by XBQs/H2O2. Surprisingly, 2,3-DCBQ displays strongest oxidation capacity among the 9 tested XBQs, which is more than twice more efficient than that of TCBQ/H2O2, and similar to that of FeIIEDTA mediated Fenton reaction. Further studies are needed to understand why 2,3-DCBQ is so special.

Figure 3. (A) Methyl oxidation products of 5mdC could also be produced by other XBQs and H2O2.

All the reaction mixture contained 2.0mM 5mdC, 1.0mM H2O2 and 0.1mM XBQs (FeII or FeIIEDTA). (B) The chemical structures of XBQs used in this study.

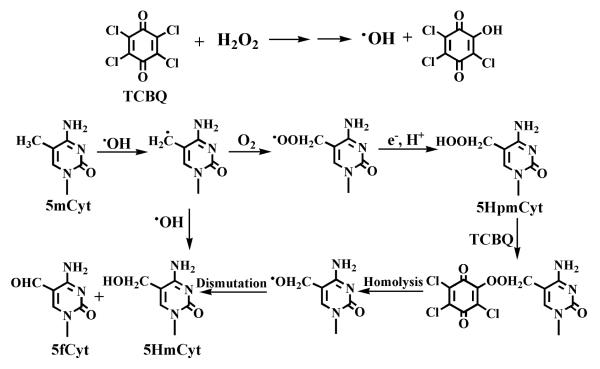

Proposed mechanism for the formation of 5mdC oxidation products by TCBQ/H2O2

Based on the above data and other previous studies [10], we proposed that the formation of 5HpmdC, 5HmdC and 5fdC from 5mdC by TCBQ/H2O2 might be through the following metal-independent mechanism (Scheme 1): First, •OH produced by TCBQ/H2O2 may abstract hydrogen atom from the methyl group of 5mdC, resulting in the formation of the carbon-centered 5-(2′-deoxycytidylyl)methyl radical, which then combines with O2 to form its corresponding peroxyl radical. The unstable peroxyl radical can transform into the corresponding hydroperoxide 5HpmdC. A further nucleophilic reaction may take place between 5HpmdC and TCBQ, forming a quinone-peroxide reaction intermediate, which can decompose homolytically to produce 5-CH2O• alkoxyl radical (Scheme 1) [14]. The generated 5-CH2O• alkoxyl radical may transform into 5HmdC and 5fdC via dismutation. The combination of 5-(2′-deoxycytidylyl)methyl radical and •OH can also lead to the formation of 5HmdC. An alternative pathway for the generation of 5HmdC and 5fdC might be due to reduction and dehydration of 5HpmdC. To our knowledge, this is the first report that halogenated quinoid carcinogens and H2O2 can induce potent methyl oxidation of 5mdC via a metal-independent mechanism.

Scheme 1.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of 5mCyt oxidation products by TCBQ and H2O2 via a metal-independent pathway.

It should be noted that, although we tried hard to identify the proposed carbon-centered 5-(2′-deoxycytidylyl)methyl radical by ESR spin-trapping methods, using various spin trapping agents such as the well-known dimethyl pyridine N-oxide (DMPO) and α-(4-pyridyl-1-oxide)-N-tert-butylnitrone (POBN), we failed to detect this radical so far. The reason might be that either the radical adduct formed may not be stable enough, or the concentration of the radical adduct was just too low to be detected by ESR. Further studies are needed to solve this problem.

Potential biological and environmental implications

In conclusion, these findings demonstrate that not only TCBQ, but also other XBQs together with H2O2 can effectively oxidize 5mdC to form its methyl oxidation products not requiring the involvement of redox-active transition metal ions, and the oxidation efficiency of some XBQs is comparable to that of classic iron-mediated Fenton reaction. These results may partly explain the potential carcinogenicity of not only PCP but also other widely used polyhalogenated aromatic compounds which can be metabolized in vivo or dechlorinated chemically to tetra-, di-, or monohalogenated quinones [4-6, 36, 37]. Recently, four chloro- and bromo-benzoquinones were identified as new chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water, which may be responsible for the observed bladder cancer risk [7, 8]. Regarding the wide distribution of XBQs in the environment and the fact that the established 5mdC oxidation occurs even at physiologically relevant concentrations of XBQ (as low as 10μM), our new findings may have potential biological and environmental implications for future study of these ubiquitous halogenated quinoid carcinogens. Further investigations are needed to study whether these oxidation reactions occur in cellular and animal models. If the conversion of 5mCyt to 5HmCyt and other oxidation derivatives by redox-active quinones were confirmed in mammalian cells, this study would provide a new understanding of a non-enzymatic pathway for DNA demethylation induced by environmental pollutants, which might play important roles in development and many diseases.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1: A) HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of oxidation products of 5mdC by TCBQ (0.1mM) and H2O2 (1.0mM). a) TIC. Specific mass transitions for 5HpmdC b), m/z 274→158; 5HmdC c), m/z 258→142; and 5fdC d), m/z 256→140; B) Positive ion spectrum (MS/MS) of 5HpmdC.

Figure S2: HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of 5HpmdC. a), photosensitized oxidation of 5mdC by 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone b), FeIIEDTA/H2O2 system c), TCBQ/H2O2 system.

Figure S3: HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and 1-carbamoyl-2-oxo-4,5-dihydroxyimidazolidine in the mixture of 5mdC (2.0mM), TCBQ (0.1mM) and H2O2 (1.0mM).

Scheme S1: Proposed mechanism for the formation of other 5mdC oxidation products 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and 1-carbamoyl-2-oxo-4,5-dihydroxyimidazolidine by TCBQ and H2O2 [9].

Highlights.

Three methyl oxidation products were generated in the mixture of 5mCyt, TCBQ and H2O2.

The oxidation was markedly inhibited by •OH scavengers and under anaerobic condition.

Analogous effects were observed in the classic Fenton system.

The proposed mechanism may partly explain halogenated quinones’ carcinogenicity.

Acknowledgement

The work in this paper was supported by Project 973 (2008CB418106); Hundred-Talent Project, CAS; NSFC Grants (21207150, 20925724, 20877081, 20890112, 20921063 and 21237005); National Institutes of Health Grants ES11497, RR01008, and ES00210 (B.-Z.Z.). This work was also supported by NIH grant HL073056 (to B.K.).

Abbreviations

- TCBQ

tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (p-chloranil)

- PCP

pentachlorophenol

- •OH

hydroxyl radical

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- 5mCyt

5-methylcytosine

- 5HmCyt

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5fCyt

5-formylcytosine

- 5caCyt

5-carboxylcytosine

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- 5mdC

5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine

- 5HmdC

5-(hydroxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine

- 5fdC

5-formyl-2′-deoxycytidine

- 5HpmdC

5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine

- p-BQ

1,4-benzoquinone

- 2-CBQ

2-chloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- 2,3-DCBQ

2,3-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- 2,5-DCBQ

2,5-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- 2,6-DCBQ

2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- TriCBQ

2,3,5-trichloro-1,4-benzoquinone

- TFBQ

tetrafluoro-1,4-benzoquinone

- TBrBQ

tetrabromo-1,4-benzoquinone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Bolton JL, Trush MA, Penning TM, Dryhurst G, Monks TJ. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000;13:135–160. doi: 10.1021/tx9902082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Song Y, Wagner BA, Witmer JR, Lehmler HJ, Buettner GR. Nonenzymatic displacement of chlorine and formation of free radicals upon the reaction of glutathione with PCB quinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:9725–9730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810352106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zhu BZ, Shan GQ. Potential mechanism for pentachlorophenol-induced carcinogenicity: a novel mechanism for metal-independent production of hydroxyl radicals. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:969–977. doi: 10.1021/tx900030v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Meunier B. Chemistry. Catalytic degradation of chlorinated phenols. Science. 2002;296:270–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1070976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gupta SS, Stadler M, Noser CA, Ghosh A, Steinhoff B, Lenoir D, Horwitz CP, Schramm KW, Collins TJ. Rapid total destruction of chlorophenols by activated hydrogen peroxide. Science. 2002;296:326–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1069297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sorokin A, Meunier B, Seris JL. Efficient oxidative dechlorination and aromatic ring cleavage of chlorinated phenols catalyzed by iron sulfophthalocyanine. Science. 1995;268:1163–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.268.5214.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhao Y, Qin F, Boyd JM, Anichina J, Li XF. Characterization and determination of chloro- and bromo-benzoquinones as new chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4599–4605. doi: 10.1021/ac100708u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Qin F, Zhao YY, Zhao Y, Boyd JM, Zhou W, Li XF. A toxic disinfection by-product, 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone, identified in drinking water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:790–792. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wagner JR, Cadet J. Oxidation reactions of cytosine DNA components by hydroxyl radical and one-electron oxidants in aerated aqueous solutions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;43:564–571. doi: 10.1021/ar9002637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xu G, Chance MR. Hydroxyl radical-mediated modification of proteins as probes for structural proteomics. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3514–3543. doi: 10.1021/cr0682047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhu BZ, Zhao HT, Kalyanaraman B, Frei B. Metal-independent production of hydroxyl radicals by halogenated quinones and hydrogen peroxide: an ESR spin trapping study. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhu BZ, Kalyanaraman B, Jiang GB. Molecular mechanism for metal-independent production of hydroxyl radicals by hydrogen peroxide and halogenated quinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17575–17578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704030104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zhu BZ, Zhao HT, Kalyanaraman B, Liu J, Shan GQ, Du YG, Frei B. Mechanism of metal-independent decomposition of organic hydroperoxides and formation of alkoxyl radicals by halogenated quinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3698–3702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605527104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhu BZ, Shan GQ, Huang CH, Kalyanaraman B, Mao L, Du YG. Metal-independent decomposition of hydroperoxides by halogenated quinones: Detection and identification of a quinone ketoxy radical. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11466–11471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900065106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhu BZ, Zhu JG, Mao L, Kalyanaraman B, Shan GQ. Detoxifying carcinogenic polyhalogenated quinones by hydroxamic acids via an unusual double Lossen rearrangement mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:20686–20690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010950107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Barlow DP. Methylation and imprinting: from host defense to gene regulation? Science. 1993;260:309–310. doi: 10.1126/science.8469984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cedar H. DNA methylation and gene activity. Cell. 1988;53:3–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90479-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Doerfler W. Patterns of DNA methylation--evolutionary vestiges of foreign DNA inactivation as a host defense mechanism. A proposal. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1991;372:557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nabel CS, Kohli RM. Demystifying DNA demethylation. Science. 2011;333:1229–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1211917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ito S, D’Alessio AC, Taranova OV, Hong K, Sowers LC, Zhang Y. Role of Tet proteins in 5mC to 5hmC conversion, ES-cell self-renewal and inner cell mass specification. Nature. 2010;466:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nature09303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C, Zhang Y. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pfaffeneder T, Hackner B, Truß M, Münzel M, Müller M, Deiml CA, Hagemeier C, Carell T. The discovery of 5-formylcytosine in embryonic stem cell DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:7008–7012. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Münzel M, Globisch D, Carell T. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, the sixth base of the genome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6460–6468. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, Ding J, Jia Y, Chen Z, Li L, Sun Y, Li X, Dai Q, Song CX, Zhang K, He C, Xu GL. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Li W, Liu M. Distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in different human tissues. J. Nucleic Acids. 2011;2011:870726. doi: 10.4061/2011/870726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jin SG, Jiang Y, Qiu R, Rauch TA, Wang Y, Schackert G, Krex D, Lu Q, Pfeifer GP. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine is strongly depleted in human cancers but its levels do not correlate with IDH1 mutations. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7360–7365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Haffner MC, Chaux A, Meeker AK, Esopi DM, Gerber J, Pellakuru LG, Toubaji A, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Nelson WG, Netto GJ, De Marzo AM, Yegnasubramanian S. Global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine content is significantly reduced in tissue stem/progenitor cell compartments and in human cancers. Oncotarget. 2011;2:627–637. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, Ito S, Yang C, Xiao MT, Liu LX, Jiang WQ, Liu J, Zhang JY, Wang B, Frye S, Zhang Y, Xu YH, Lei QY, Guan KL, Zhao SM, Xiong Y. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cao H, Wang Y. Quantification of oxidative single-base and intrastrand cross-link lesions in unmethylated and CpG-methylated DNA induced by Fenton-type reagents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:4833–4844. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Castro GD, Stamato CJ, Castro JA. 5-methylcytosine attack by free radicals arising from bromotrichloromethane in a model system: structures of reaction products. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1994;17:419–428. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Castro GD, Diaz Gomez MI, Castro JA. 5-Methylcytosine attack by hydroxyl free radicals and during carbon tetrachloride promoted liver microsomal lipid peroxidation: structure of reaction products. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1996;99:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(95)03680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Privat E, Sowers LC. Photochemical deamination and demethylation of 5-methylcytosine. Chem. Res.Toxicol. 1996;9:745–750. doi: 10.1021/tx950182o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bienvenu C, Wagner JR, Cadet J. Photosensitized oxidation of 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine by 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone: characterization of 5-(hydroperoxymethyl)-2′-deoxycytidine and stable methyl group oxidation products. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:11406–11411. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Haugland RA, Schlemm DJ, Lyons RP, 3rd, Sferra PR, Chakrabarty AM. Degradation of the chlorinated phenoxyacetate herbicides 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid by pure and mixed bacterial cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1990;56:1357–1362. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1357-1362.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chignell CF, Han SK, Mouithys-Mickalad A, Sik RH, Stadler K, Kadiiska MB. EPR studies of in vivo radical production by 3,3′,5,5′-tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in the Sprague-Dawley rat. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2008;230:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: A) HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of oxidation products of 5mdC by TCBQ (0.1mM) and H2O2 (1.0mM). a) TIC. Specific mass transitions for 5HpmdC b), m/z 274→158; 5HmdC c), m/z 258→142; and 5fdC d), m/z 256→140; B) Positive ion spectrum (MS/MS) of 5HpmdC.

Figure S2: HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of 5HpmdC. a), photosensitized oxidation of 5mdC by 2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone b), FeIIEDTA/H2O2 system c), TCBQ/H2O2 system.

Figure S3: HPLC-MS/MS MRM analysis of 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and 1-carbamoyl-2-oxo-4,5-dihydroxyimidazolidine in the mixture of 5mdC (2.0mM), TCBQ (0.1mM) and H2O2 (1.0mM).

Scheme S1: Proposed mechanism for the formation of other 5mdC oxidation products 5,6-dihydroxy-5,6-dihydro-5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine and 1-carbamoyl-2-oxo-4,5-dihydroxyimidazolidine by TCBQ and H2O2 [9].