Abstract

Background

Several studies have assessed the effects of computer-based cognitive programs (CCP) in the management of age-related cognitive decline, but the role of CCP remains controversial. Therefore, this systematic review evaluated the evidence on the efficacy of CCP for age-related cognitive decline in healthy older adults.

Methods

Six electronic databases (through October 2014) were searched. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool. The standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of a random-effects model were calculated. The heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q statistic and quantified with the I2 index.

Results

Twelve studies were included in the current review and were considered as moderate to high methodological quality. The aggregated results indicate that CCP improves memory performance (SMD, 0.31; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.45; p < 0.0001) and processing speed (SMD, 0.50; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.87; p = 0.007) but not executive function (SMD, -0.12; 95% CI -0.33 to 0.09; p = 0.27). Furthermore, there were long-term gains in memory performance (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.05; p = 0.01).

Conclusion

CCP may be a valid complementary and alternative therapy for age-related cognitive decline, especially for memory performance and processing speed. However, more studies with longer follow-ups are warranted to confirm the current findings.

Introduction

Age-related cognitive decline, as a non-pathological loss in cognitive function, is common in older adults [1–5] that hampers the basic activities of daily life, resulting in a loss of personal autonomy [6–8]. The loss of independence is a key feature of dementia and is a source of both physical and psychological stress for older adults [9]. Therefore, there is a growing demand for effective, low-cost solutions to improve or delay age-related cognitive decline.

Cognitive training programs have been offered to prevent or minimize age-related cognitive decline and usually consist of guided practice of specific cognitive tasks or cognitive stimulation programs aimed at improving general cognition [10]. Previous studies indicated that traditional cognitive training programs could enhance cognitive functions, such as memory performance, processing speed and executive function in healthy older adults [10–12].

With the development of new technologies, computer-based cognitive programs (CCP), which promise a series of advantages over traditional cognitive training, have been rapidly disseminated to older adults. CCP can set the initial level of task difficulty according to the participants’ baseline competency and can be gradually adjusted as performance improves, which keeps the activity engaging and fun. Furthermore, CCP enable the standardization of intervention [13]. In the last two decades, CCP have been well developed, and some clinical trials reported CCP delayed cognitive decline and improved cognitive function in healthy older adults [14–18]. However, the role of CCP in the management of age-related cognitive decline remains controversial. A previous review also reported that computerized cognitive training was an effective, less labor intensive alternative for treating cognitive impairment [19], but it was only a descriptive review without a quantitative analysis.

Therefore, this review evaluated the evidence on the efficacy of CCP for age-related cognitive decline in healthy older adults. The meta-analyses in this review focused on memory performance, processing speed and executive function. Based on our findings, we offer recommendations for future research.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

Electronic databases (to October 2014) were searched: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database, Wan Fang Data and Weipu Database for Chinese Technical Periodicals. The following keywords were used in various combinations: older adult(s), elderly, aging, aged, cognition, cognitive ability, cognitive function, computer(s), computerized training, video and game(s). To identify unpublished studies, trial registrations (WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) and dissertations (Chinese Dissertation Full-text Database and ProQuest Dissertations) were searched. The reference lists of relevant articles were reviewed for additional trials, and we contacted experts in the field.

Study selection

The studies that met the following criteria were included: (1) study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs); (2) the participant: healthy older adults (> 60 years old); (3) the intervention: CCP including modified cognitive training tasks, video games or neuropsychological software designed to improve cognitive functions, such as memory, processing speed, executive function, etc.; (4) the outcomes: memory, executive function, processing speed; and (5) the publication was available in either English or Chinese. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) participants were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of senile dementia; (2) the outcomes did not include any cognitive functions; and (3) participants were mixed with younger and older adults. After the exclusion of duplicates, two authors independently identified and selected the studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion among the authors.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted data from the studies. The following contents were extracted: general information (study source, sample size and age), details of the intervention (type, duration and dose), main outcomes and the follow-up duration. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was assessed independently by two authors using the Cochrane Collaboration tool [20,21]. The following domains were assessed: 1) random sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding of participants and personnel, 4) blinding of outcome assessments, 5) incomplete outcome data and 6) selective reporting. Every domain was classified as “low risk of bias”, “high risk of bias” or “unclear risk of bias”. The necessary information was supplemented by contacting the corresponding author. There were no disagreements on the risk of bias assessments among the authors.

Data synthesis and analysis

The meta-analyses were conducted using the Cochrane Collaboration software (Review Manager Version 5.2). For continuous data, the standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated in the meta-analysis. In order to get expected heterogeneity, random-effects model was employed in summary estimates of the treatment effect. The heterogeneity was assessed by the Cochran Q statistic (considered significant when the P value was less than 0.10) and was quantified using the I 2 index (considered high when I 2 was greater than 75%). Similar intervention groups were combined using the formula of the Cochrane handbook for a single pair-wise comparison. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on outcome measures. Potential publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting of the Begg funnel plots.

Results

Literature search

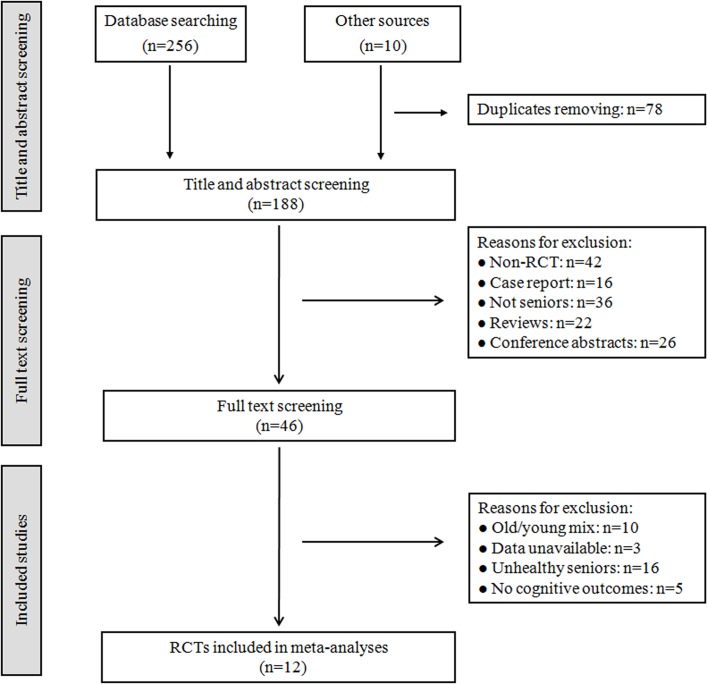

The detailed search process is illustrated in Fig 1. A total of 188 records were retrieved after removing duplicates. In total, 46 full-text publications were identified after screening the titles and abstracts. Based on the inclusion criteria, 12 studies were included in the review [14–18,22–28]. During the full-text screening, 34 studies were excluded due to unavailable data [29–31] (n = 3), no cognitive measures (n = 5), old/young mix (n = 10) and unhealthy seniors (n = 16). During conducting this review, the related experts were contacted, but there were not more information such as unpublished data, ongoing research, etc.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of study selection.

RCTs: randomized controlled trials.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of all the included studies are summarized in Table 1. In total, 12 RCTs with 2008 participants were included in our review [14–18,22–28]. All of the studies were published in English. The study duration ranged from 4 weeks to 24 weeks. The training programs were practiced 10 to 75 sessions (mean ± SD: 32.67 ± 17.84) ranging from 15 to 120 minutes each session (mean ± SD: 55.83 ± 29.19). The follow-up duration ranged between 12 and 48 weeks. The control interventions included no contact control [14,16], education [15,16,22–25], no training [17], physical exercise [18,23], Tetris [26], computer-based daily online news [27] and waiting list [28].

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

| First author, year, country | Sample size | Age: mean or range (year) | Dose | Follow-up (week) | Main outcome Assessments | Experimental group Intervention (Game name) | Control group intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edwards, 2002, US[14] | 97 | 74 | 60 min, 10 sessions, 6 wk | — | Digit span, Stroop test, Trial making test A and B, Digit symbol subset | Computerized speed of processing training | No contact control |

| Edwards, 2005, US[15] | 181 | 76 | 60 min, 10 sessions, 5 wk | — | Digit span, Stroop test, Trial making test A and B, Digit symbol subset | Computerized speed of processing training | Computerized education |

| Mahncke, 2006, US[16] | 182 | 71 | 60 min, 40–50 sessions, 8–10 wk | 12 | Digit span, Processing speed | Brain plasticity–based computerized cognitive Training | 1) Video-education; 2) No-contact control |

| Basak, 2008, US[17] | 40 | 69 | 120 min, 21–24 sessions, 7–8 wk | — | Visual short-term memory, Operation span | Real-time strategy video game | No training |

| Buschkuehl, 2008, Switzerland[18] | 39 | 80 | 32 min, 24 sessions, 12 wk | 48 | Digit span, Verbal free recall, Viaual free recall | Computerized cognitive training(Working memory and reaction time tasks) | Physical exercise |

| Smith, 2009, US[22] | 487 | 75 | 60 min, 40 sessions, 8 wk | — | Digit span, Letter-number sequencing, Immediate recall, Delayed recall, Overall memory, Processing speed | Brain plasticity–based computerized cognitive training | Video-education |

| Klusmann 2010, Germany[23] | 259 | 70–93 | 90 min, 75 sessions, 24 wk | — | Immediate recall, Delayed recall, Stroop test, Trail making tests A/B | Computerized cognitive training | 1) Physical exercise; 2) Education |

| Stern, 2011, US[24] | 60 | 66 | 60 min, 36 sessions, 12 wk | 12 | Letter-number sequencing, Digit symbol subset, Trial making test A and B | 1) Emphasis change game training (Space Fortress)2) Standard game training (Space Fortress) | Education |

| Zelinski, 2011, US[25] | 487 | 75 | 60 min, 40 sessions, 8–10 wk | 12 | Letter-number sequencing, Digit span, Immediate recall, Delayed recall, Overall memory, Processing speed | Brain plasticity–based computerized cognitive Training | Video-education |

| Nouchi, 2012, Japan[26] | 32 | 69 | 15 min, 20 sessions, 4 wk | — | Frontal assessment battery at bedside, Trial making test B, Digit symbol coding and symbol search | Brain game training(Brain Age) | Tetris |

| Bozoki, 2013, US[27] | 60 | 68 | 30 min, 30 sessions, 6 wk | — | Delayed recall, MON-monitoring, IDN-identification | Computerized game training (My Better Mind) | Computer-based daily online news |

| Miller, 2013, US[28] | 84 | 82 | 20–25 min, 40 sessions, 8 wk | 16 | WMS-III | Computerized cognitive training (Dakim’s Brain Fitness) | Waiting list |

Abbreviations: wk = week; MON = Monitoring (simple reaction time); IDN = Identification (visual-motor reaction time); WMS-III = Wechsler memory scale III.

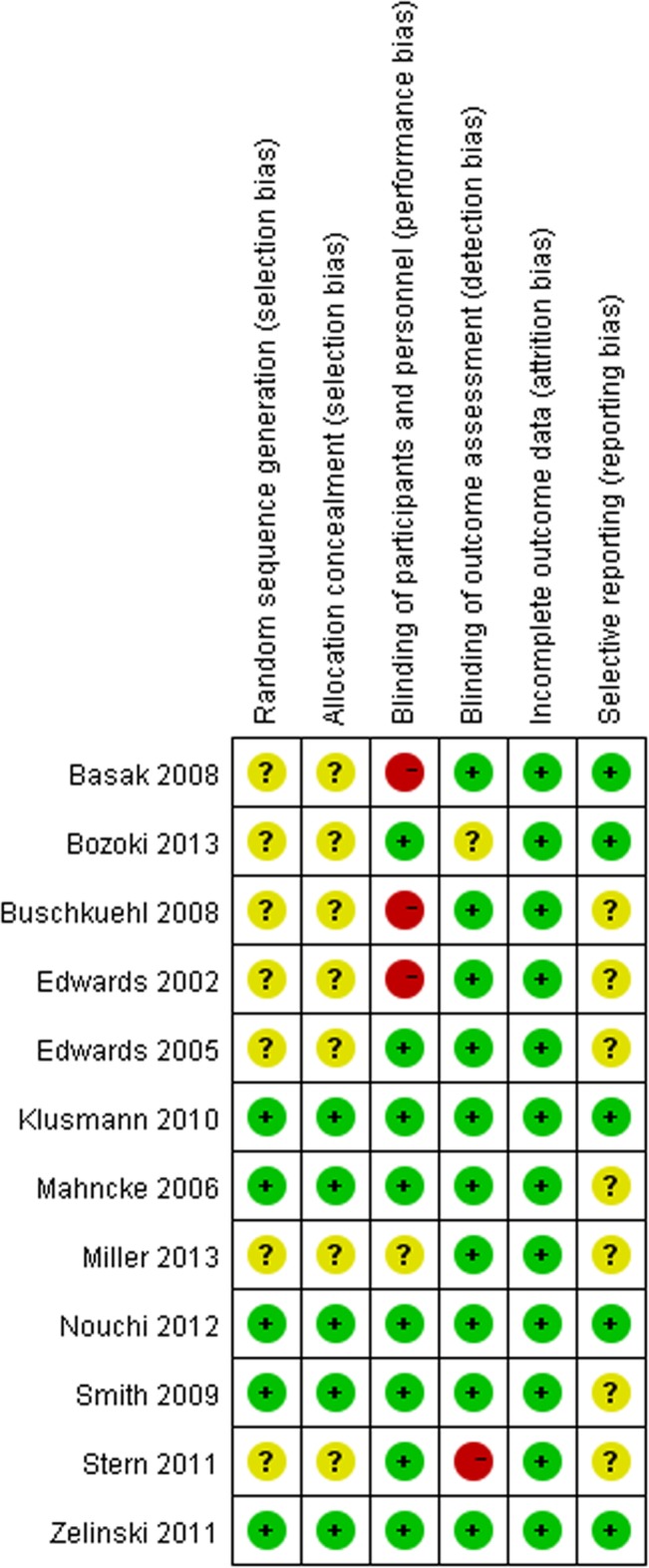

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in the individual studies is presented in Fig 2. In total, 5 trials [16,22,23,25,26] reported adequate methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment, and the other studies were unclear [14,15,17,18,24,27,28]. Most trials (83%) [14–18,22,23,25,26,28] used independent outcome assessors who were unaware of the group assignment. Although 3 studies were at high risk for bias [14,17,18], 8 trials (67%) [15,16,22–27] blinded the participants. For incomplete outcome data, all trials [14–18,22–28] were at low risk. 5 trials [17,23,25–27] were at low risk for selective reporting. In assessing the bias, necessary information was supplemented or clarified by contacting study-authors, especially for selective reporting [23,25,26].

Fig 2. Risk of bias.

Red (-): high risk of bias; Yellow (?): unclear risk of bias; Green (+): low risk of bias.

Quantitative data synthesis

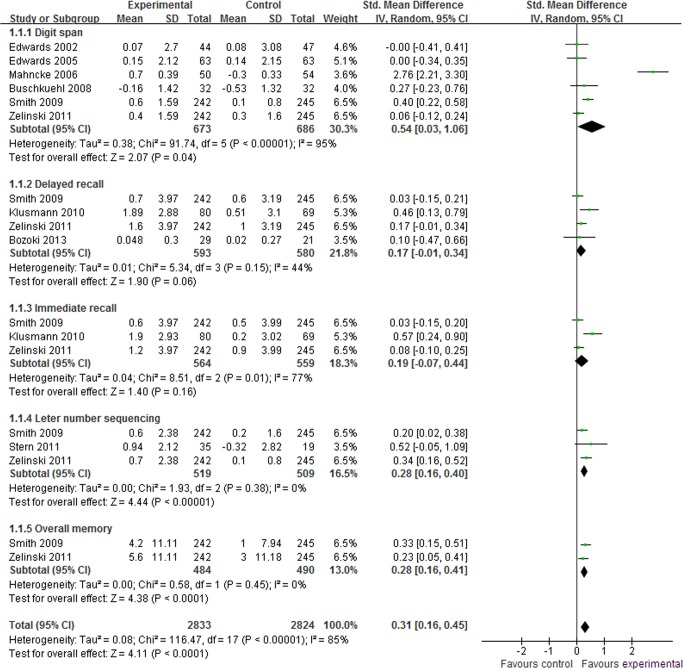

Memory

Memory is the ability to retain, store and recall information. Age-related memory loss is a universal condition for older adults. In total, 10 studies [14–18,22–25,27] assessed the effect of CCP in memory performance. The aggregated results indicated that CCP improved memory performance (SMD, 0.31; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.45; p < 0.0001, Fig 3) compared to the control interventions. In the subgroup meta-analyses, CCP demonstrated significant effects in digit span (SMD, 0.54; 95% CI 0.03 to 1.06; p = 0.04, Fig 3) [14–16,18,22,25], letter-number sequencing (SMD, 0.28; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.40; p < 0.00001, Fig 3) [22,24,25] and over memory (SMD, 0.28; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.41; p < 0.0001, Fig 3) [22,25]. CCP were also associated with small but not significant improvements in delayed recall (SMD, 0.17; 95% CI -0.01 to 0.34; p = 0.06, Fig 3) [22,23,25,27] or immediate recall (SMD, 0.19; 95% CI -0.07 to 0.44; p = 0.18, Fig 3) [22,23,25].

Fig 3. Forest plot of the effect of computer-based cognitive programs in memory performance.

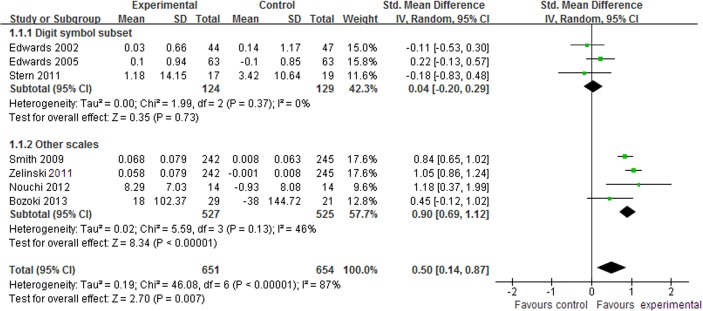

Processing speed

Processing speed is the ability to quickly process information. In total, 8 studies [14–16,22,24–27] assessed the effect of CCP on processing speed. There was no significant difference between CCP and control interventions in digit symbol subset (SMD, 0.04; 95% CI -0.20 to 0.29; p = 0.73, Fig 4) [14,15,24] but CCP demonstrated better effects in other assessment scales (SMD, 0.90; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.12; p < 0.00001, Fig 4) [22,25–27]. Furthermore, the aggregated results indicated that CCP were associated with significant improvements in processing speed (SMD, 0.50; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.87; p = 0.007, Fig 4).

Fig 4. Forest plot of the effect of computer-based cognitive programs in processing speed.

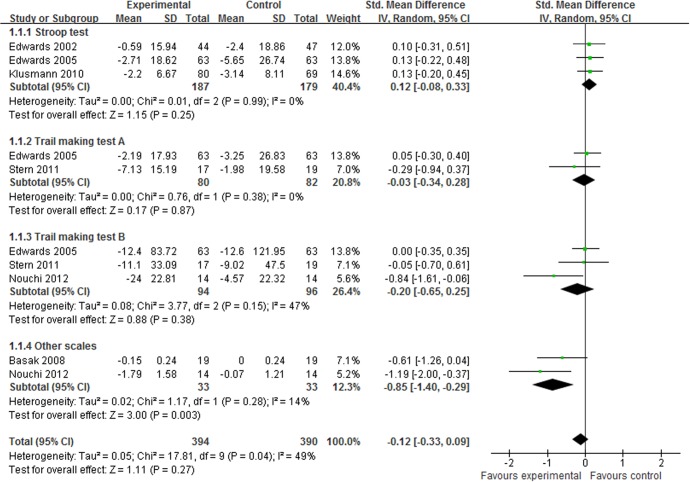

Executive function

Executive function consists of a broad spectrum of abilities, including cognitive flexibility, planning, and abstract thinking skills. Older adults usually have poorer executive function due to cognitive decline [32]. In total, 6 studies [14,15,17,23,24,26] assessed the effect of CCP on executive function. The aggregated results indicated that there was no significant difference between CCP and control interventions on executive function (SMD, -0.12; 95% CI -0.33 to 0.09; p = 0.27, Fig 5). In the subgroup meta-analyses, the results did not support the effect of CCP in the Stroop test (SMD, 0.12; 95% CI -0.08 to 0.33; p = 0.25, Fig 5) [14,15,23], trail marking test A (SMD, -0.03; 95% CI -0.34 to 0.28; p = 0.87, Fig 5) [15,24] or trail marking test B (SMD, -0.20; 95% CI -0.65 to 0.25; p = 0.38, Fig 5) [15,24,26].

Fig 5. Forest plot of the effect of computer-based cognitive programs in executive function.

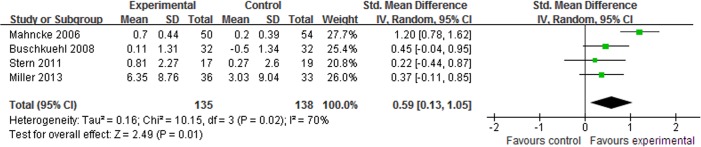

The long-term effect

In total, 5 studies [16,18,24,25,28] assessed the long-term effect of CCP for age-related cognitive decline. Some studies reported that there was no significant difference between CCP and control interventions, but the aggregated results indicate that CCP had better long-term effects on memory performance (SMD, 0.59; 95% CI 0.13 to 1.05; p = 0.01, Fig 6) [16,18,24,28]. Significant differences in the improvements from baseline to the 3-month follow-up were also reported between brain plasticity-based computerized cognitive training and video education in processing speed and attention [25].

Fig 6. Forest plot of the long-term effect of computer-based cognitive programs in memory performance.

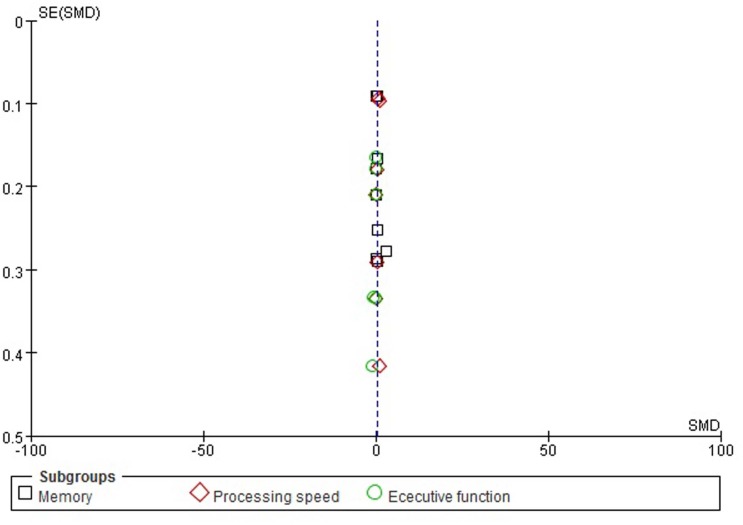

Publication bias

The funnel plots for memory, processing speed, and executive function were performed (Fig 7), but it is difficult to interpret the result of publication bias due to such a small subset of studies.

Fig 7. Funnel plot for memory, processing speed, and executive function.

Discussion

The current review evaluated the evidence on the effects of CCP in age-related cognitive decline in healthy older adults. In total, 12 moderate to high quality studies were included in our review. The aggregated results indicated that CCP improved memory performance and processing speed. There was also a long-term enhancement in memory performance.

Our positive results concur with previous reviews [10,19]. The last review conducted by Kueider and his colleagues concluded that computerized training was an effective, less labor intensive alternative compared with traditional, paper-and-pencil cognitive training [19]. However, it was only a qualitative review with both RCTs and non-RCTs published from 1986 to 2011. Any strictly qualitative approach may be problematic because it is more subjective than a meta-analysis. In our review, 12 moderate to high quality RCTs were included [14–18,22–28]. Detailed subgroup meta-analyses were conducted based on the different outcome measures. The aggregated results indicated that CCP improved memory performance and processing speed. Furthermore, there was a long-term enhancement in memory performance. Consequently, the current review provides stronger evidence of CCP beneficial effects on age-related cognitive decline.

Compared with traditional cognitive training, CCP have several advantages. It is a more convenient, cost-effective training strategy for older adults with cognitive decline. With the development of modern technology, ownership of personal computers has grown sharply, and older adults have access to CCP. Computerized training also requires less face-to-face training. Thus, trainer costs can be significantly reduced. Furthermore, CCP offer self-paced, individualized training, which sets the initial level of task difficulty according to the baseline competency of the participants and gradually adjusts it as they improve performance (keeping the activity engaging and fun). These advantages promote the application and popularization of CCP.

The CCP-related improvements in cognitive function may be associated with neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is a long-term physiological process of structural and functional self-repair in the brain [33]. Enhancing plasticity in the older adult brain may slow the progression of cognitive decline and improve specific cognitive functions, such as memory, attention, language and executive function [16,22,25]. Computer-based cognitive training usually consists of programmed tasks, which may adjust the complexity of the training based on the user’s performance. This programmed stimulation is beneficial for neuroplasticity in the brain [16,22]. Brain plasticity-based computerized cognitive training indicated favorable gains in memory performance, processing speed and attention in older adults [16,22,25]. Brain imaging findings support that neuroplasticity training may increase the activation of damaged brain regions, which may improve cognitive function and facilitate recovery from neurological diseases [34]. Previous studies also demonstrated that cognitive training might benefit plasticity by improving sensory systems in the cerebral cortex [35,36].

There were some potential limitations in our review. 1) Some aggregated results may have been influenced by high heterogeneity, especially for immediate recall and digit span. The main reason was that different computerized tasks were used in eligible studies. These tasks contained not only simple arithmetic calculations, but also complex logic puzzle games designed to engage spatial executive processing and non-verbal reasoning. Although tasks may continuously adjust difficulty based on user performance, their complexity was obviously different. Furthermore, dosage of computerized interventions may affect the aggregated results. It ranged from 4 weeks to 24 weeks in eligible studies. Longer treatment period may result in better improvements. In addition, the explanation could be age differences, but there are not obvious age differences among eligible studies. 2) Only studies published after 2000 were included in our review because the criteria for mild cognitive impairment were not defined until 1999 [37]. Some patients with mild cognitive impairment may be included in earlier studies. 3) There was a degree of uncertainty in identifying the relevant studies due to limited retrieval resources, language barriers, and publication bias.

Conclusions

In this review, there was positive evidence of CCP benefits for age-related cognitive decline in healthy older adults. CCP should be recommended as a complementary and alternative therapy for age-related cognitive decline, especially in memory performance and processing speed. However, more well-designed RCTs with longer follow-ups are warranted to confirm the current findings.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Nilsson L-G. Memory function in normal aging. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2003; 107: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Salthouse TA. Memory aging from 18 to 80. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003; 17: 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coppin AK, Shumway-Cook A, Saczynski JS, Patel KV, Ble A, Ferrucci L, et al. Association of executive function and performance of dual-task physical tests among older adults: analyses from the InChianti study. Age Ageing. 2006; 35: 619–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ. Declining Executive Control in Normal Aging Predicts Change in Functional Status: The Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004; 52: 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salthouse TA. The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review. 1996; 103: 403–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee Y, Kim JH, Lee KJ, Han G, Kim JL. Association of cognitive status with functional limitation and disability in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005; 17: 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cahn-Weiner DA, Malloy PF, Boyle PA, Marran M, Salloway S. Prediction of functional status from neuropsychological tests in communitydwelling elderly individuals. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000; 14: 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Owsley C, McGwin G. Association between visual attention and mobility in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004; 52: 1901–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reijnders J, van Heugten C, van Boxtel M. Cognitive interventions in healthy older adults and people with mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Ageing Research Reviews. 2013; 12:263–275. 10.1016/j.arr.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, Marsiske M, et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288: 2271–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Uchida S, Kawashima R. Reading and solving arithmetic problems improves cognitive functions of normal aged people: a randomized controlled study. Age (Dordr). 2008; 30: 21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gates N, Valenzuela M. Cognitive exercise and its role in cognitive function in older adults. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010; 12: 20–27. 10.1007/s11920-009-0085-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Edwards J, Wadley V, Myers Re, Roenker DL, Cissell G, Ball K. Transfer of a speed of processing intervention to near and far cognitive functions. Gerontology. 2002; 48:329–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edwards JD, Wadley VG, Vance DE, Wood K, Roenker DL, Ball KK. The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday performance. Aging Ment Health. 2005; 9:262–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahncke HW, Connor BB, Appelman J, Ahsanuddin ON, Hardy JL, Wood RA, et al. Memory enhancement in healthy older adults using a brain plasticity-based training program: a randomized, controlled study. Proc Nalt Acad Sci USA. 2006; 103:12523–12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basak C, Boot WR, Voss MW, Krammer AF. Can training in a real-time strategy video game attenuate cognitive decline in older adults? Psychol Aging. 2008; 23:765–777. 10.1037/a0013494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buschkuehl M, Jaeqqi SM, Hutchison S, Perrig-Chiello P, Däpp C, Müller M, et al. Impact of working memory training on memory performance in old-old adults. Psychol Aging. 2008; 23:743–753. 10.1037/a0014342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kueider AM, Parisi JM, Gross AL, Rebok GW. Computerized cognitive training with older adults: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40588 10.1371/journal.pone.0040588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins JPT, Douglas GA. Assessing risk of bias in included studies In: Julian PTH, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. pp. 187–241. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2011. October 18;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith GE, Housen P, Yaffe K, Ruff R, Kennison RF, Mahncke HW, et al. A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity: results from the Improvement in Memory with Plasticity-based Adaptive Cognitive Training (IMPACT) study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009; 57:594–603. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klusmann V, Evers A, Schwarzer R, Schlattmann P, Reischies FM, Heuser I, et al. Complex mental and physical activity in older women and cognitive performance: a 6-month randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010; 65:680–688. 10.1093/gerona/glq053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stern Y, Blumen HM, Rich LW, Pichards A, Herzberg G, Gopher D. Space fortress game training and exercise control in older adults: a pilot intervention. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2011; 18:653–677. 10.1080/13825585.2011.613450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zelinski EM, Spina LM, Yaffe K, Ruff R, Kennison RF, Mahncke HW, et al. Improvement in memory with plasticity-based adaptive cognitive training: results of the 3-month follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011; 59:258–265. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nouchi R, Taki Y, Takeuchi H, Hashizume H, Akitsuki Y, Shigemune Y, et al. Brain training game improves executive functions and processing speed in the elderly: a randomized controlled trial. PloS One. 2012;7(1):e29676 10.1371/journal.pone.0029676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bozoki A, Radovanovic M, Winn B, Heeter C, Anthony JC. Effects of a computer-based cognitive exercise program on age-related cognitive decline. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013; 57:1–7. 10.1016/j.archger.2013.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller KJ, Dye RV, Kim J, Jennings JL, O’Toole E, Wong J, et al. Effect of a computerized brain exercise program on cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013; 21:655–663. 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jia FW, Li SY, Pu F, Li DY. A training system for cognitive function of the age based on Android. Medical Information. 2014; 27:2–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhu L, Song W, Yue Y, Liu L. Effect of computer-assisted cognitive training on the cognitive function and depression in patients. Clin J Cerebrovasc. 2011; 8:508–512. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu WB, Hu YS, Wu Y, Bai YL, Jiang LC, Zhu B, et al. A study of rehabilitation video training for cognitive impairment. Chinese Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2008; 07:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li H, Lv C, Zhang T, Chen K, Chen C, Gai G, et al. Trajectories of age-related cognitive decline and potential associated factors of cognitive function in senior citizens of Beijing. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2014; 11:806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mesulam MM. A plasticity-based theory of the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000; 924:42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levin HS. Neuroplasticity and brain imaging research: implications for rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 87(12 Suppl 2):S1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gilbert CD, Sigman M, Crist RE. The neural basis of perceptual learning. Neuron. 2001; 31:681–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM. Cortical plasticity: From synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998; 21:149–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment. Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999; 56:303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.