Abstract

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) is a ubiquitous brominated flame retardant, showing widespread environment and human exposures. A variable domain of the heavy chain antibody (VHH), naturally occurring in camelids, approaches the lower size limit of functional antigen-binding entities. Ease of genetic manipulation makes such VHHs a superior choice to use as an immunoreagent. In this study, a highly selective anti-TBBPA VHH T3-15 fused with alkaline phosphatase (AP) from E. coli was expressed, showing both an integrated TBBPA-binding capacity and enzymatic activity. A one-step immunoassay based on the fusion protein T3-15-AP was developed for TBBPA in 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)/phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), with a half-maximum signal inhibition concentration (IC50) of 0.20 ng mL−1. Compared to the parental VHH T3-15, T3-15-AP was able to bind to a wider variety of coating antigens and the assay sensitivity was slightly improved. Cross-reactivity of T3-15-AP with a set of important brominated analogs was negligible (<0.1%). Although T3-15-AP was susceptible to extreme heat (90 °C), much higher binding stability at ambient temperature was observed in the T3-15-AP based assay for at least 70 days. A simple pretreatment method of diluting urine samples with DMSO was developed for a one-step assay. The recoveries of TBBPA from urine samples by this one-step assay ranged from 96.7–109.9% and correlated well with an HPLC-MS/MS method. It is expected that the dimerized fusion protein, VHH-AP, will show promising applications in human exposure and environmental monitoring.

Keywords: Tetrabromobisphenol A, Variable domain of heavy chain antibody, Alkaline phosphatase, Fusion protein, Immunoassay, Urine

INTRODUCTION

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is routinely used for small molecules such as pesticides, drugs, and hormones in environmental and biomedical analysis due to its sensitivity, simplicity and high-throughput. Numerous ELISAs for small molecules are performed in a two-step competitive protocol which normally requires the addition of a primary (recognition) antibody followed by a secondary antibody chemically conjugated to an enzyme such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or alkaline phosphatase (AP). Alternatively, a one-step protocol that avoids the use of secondary antibodies has been developed with either the analyte or the recognition antibody chemically conjugated with enzymes or other reporters 1. The chemical conjugation methods may cause random cross-linking of molecules 2, leading to the loss of the enzyme activity or the antibody binding avidity to some extent. Also, the molecular ratio of such conjugate is hard to control and costly reagents are required. An attractive alternative method is genetically constructing a fusion protein of enzyme and antibody3, 4, thus eliminating the use of chemically produced antibody–enzyme conjugates when performing ELISAs. Advances in recombinant DNA technology enabled the production of single-chain variable fragments (scFv) and AP fusion proteins which have been demonstrated to preserved the binding and enzyme activity3. However, the poor affinity, solubility and stability of scFv may influence the interaction of fusion protein with target antigens 2, 5.

As an alternative to scFv, the variable domain of heavy chain antibody (VHH), a fragment derived from the camelid antibody devoid of light chain, is able to bind antigens comparable to conventional antibodies (polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies, pAbs 6, 7, 8 and mAbs 9). The VHH is smaller (around 15KD) than the scFv while showing greater thermal stability and solubility. Its concave-shaped paratopes make it robust 10 and able to recognize active sites normally inaccessible or cryptic for pAbs and mAbs 11. The ability of camelid VHHs to refold following heat or chemical denaturation is not observed for conventional antibodies or their recombinant fragments, i.e. scFv 12. VHHs can be genetically manipulated and easily cloned in bacteria 13, fungi 14 and even in plants 15 to pursue a variety of applications. Camelid VHHs genetically fused with green fluorescent proteins (GFP) proved to have both functional of VHH and GFP 16, serving as a tracer for antigens in live cells. The production of VHH-AP fusions specific for cholera toxin (CTX), ricin, staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) 17 and ochratoxin A18 have also been described. These VHH-AP fusions not only provide an enhanced affinity but also function as a combined target recognition and signal transduction molecule. These VHH-based fusion proteins simplified assay protocols, showed good solubility and reproducibility, and therefore have been gaining increasing attention in numerous biotechnological applications 19, 20. To explore the possibility of expanding the scope of this technology to environmental monitoring, in this study we developed a VHH-AP based one-step immunoassay for the small molecule pollutant tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA).

TBBPA has the largest worldwide market among all of the brominated flame retardants (BFRs) 21. It was widely used as a reactive flame retardant, covalently bound to printed circuit boards, epoxy and polycarbonate resins, and also as an additive flame retardant added to acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) resins or high impact polystyrene (HIPS) 21. The widespread usage of TBBPA has led to accumulation in abiotic and biotic matrices 22–24 and increased the concern regarding food safety and health in spite of its low toxicity 25. Although the exposure risk of TBBPA to the general population is low 26, there are risks associated with exposure to contaminated dust in occupational setting 27. Gas and liquid chromatography based techniques are the general methods in detecting TBBPA in various samples 28–30. As an alternative, immunoassays have been developed for TBBPA for environmental detection with high sensitivities 31–34. In an earlier work, we reported the selection of VHHs specific for TBBPA from an immunized alpaca VHH-derived library and the development of a VHH-based ELISA with a half-maximum signal inhibition concentration (IC50) of 0.4 ng mL−1 TBBPA 7.

VHH-AP fusion proteins have been used to develop quick immunoassays for large molecules 17, but it remains to be demonstrated if such constructs are suitable for small molecules. In this study, five anti-TBBPA VHH fusion with AP were expressed and used to develop a one-step ELISA for monitoring TBBPA in human urine. In addition, the binding ability and thermal stability were also measured and compared between the VHH-AP fusion proteins and the parental VHHs. This work presents VHH-AP fusion protein is a potential immunoreagent in environmental monitoring for small molecules.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Safety

All the sharps were disposed into sharps disposal containers, according to campus policies of the University of California, Davis. TBBPA and its analogs were discarded as hazardous waste and the tubes containing urine samples were discarded as biological waste.

Materials and Methods

The synthesis of haptens T1–T6 (Figure S-1 in Supporting Information) and the selection of anti-TBBPA VHHs were described in previous studies 7, 32. The TBBPA standard was purchased from TCI Co. Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). TBBPA derivatives and other BFR analogs were purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA). Plasmid pecan 45 encoding AP genes was a generous gift from Dr. Jinny L. Liu and Dr. Ellen R. Goldman from the Naval Research Laboratory, Washington D.C.. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP), bovine serum albumin (BSA) and imidazole were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO. USA). All restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were bought from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Ipswich, MA. USA). HisPur Ni-NTA resin, B-PER, Halt protease inhibitor cocktail, and Nunc MaxiSorp flat-bottom 96 well plates were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL, USA).

Preparation of the Fusion Protein VHH-AP

According to the amino acid sequences of the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) (Figure S-2 in Supporting Information), five anti-TBBPA VHHs (T3-4, T3-9, T3-12, T3-15, and T3-16) were selected using coating antigen T3-BSA and encoded in the pComb 3X vector. VHH genes were amplified by PCR (Forward primer: 5′-CAT GCC ATG GTG GCC CAG CCG GCC CAT KTG CAT CTC GTG GAG TCN GGN GG. Reverse primer 1: 5′-CAT GCC ATG ACT CGC GGC CCC CGA GGC CTC GTG GGG GTC TTC GCT GTG GTG CG; Reverse primer 2: 5′-CAT GCC ATG ACT CGC GGC CCC CGA GGC CTG GCC TTG TTT TGG TGT CTT GGG) and cloned into the AP-plasmid (pecan 45) using complementary Sfi I restriction sites. The VHH plasmid and VHH-AP plasmid were transformed to E. coli TOP 10F′ and BL21(DE3)pLysS, respectively, by heat shock. The proteins were expressed by 0.5 mM IPTG induction and purified with Ni-NTA resin by using 150 mM imidazole in PBS (0.01 mol L−1 phosphate, 0.137 mol L−1 NaCl, 3 mmol L−1 KCl, pH 7.4) for elution. The size and purity of VHHs and VHH-APs were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The VHHs and fusion VHH-APs were collected and stored at 20 °C after dialysis with 0.01 M PBS.

One-step ELISA Performance

Haptens T1–T6 coupled to the carrier protein BSA were used as coating antigens. One-step competitive ELISAs were carried out as follows. A microtiter plate was coated overnight with 100 μL of coating antigen (1μg mL−1) in 0.05 mol L−1 carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4 °C. The plate was blocked with 3% skim milk in PBS (pH 7.4) at ambient temperature for 1 h. After washing with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20), 50 μL per well of serial dilutions of TBBPA were added to the plate, followed by 50 μL of the VHH-APs, the concentrations of which have been determined by checkerboard titration. After incubation at ambient temperature for 1 h, the plate was washed and the AP activity was determined by addition of 150 μL of 1.0 mg mL−1 pNPP (1 M glycine buffer, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM ZnCl2, pH 10.4). The reaction was stopped at 10 min by addition of 50 μL of 3 M NaOH solution, and the absorbance was read in a microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 405 nm. The IC50 value was obtained from a four-parameter logistic equation generated by SigmaPlot 10.0. The indirect competitive VHH-based ELISA was developed in our previous work 7. In this study, T3-15-AP was selected to optimize and develop a one-step immunoassay.

Optimization of ELISA

The effects of organic solvents and pH on ELISA performance (IC50 and maximal signal (A0)) were studied at ambient temperature. The TBBPA was separately dissolved in PBS containing different concentrations of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or methanol (MeOH) (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 60%, v/v). The effects of buffer pH in a range of 4.0–11.0 on the assay were evaluated. Except the single variable, the rest of the assay conditions were the same as described above.

Cross-reactivity

The specificity of the T3-15-AP based assay was determined by its cross-reactivity (CR) with a group of structural analogs in a range of 0–2000 ng mL−1. The cross-reactivity was calculated with the equation as follows: CR (%) = [IC50(TBBPA)/IC50(tested compound)]×100.

Stability of VHH-AP

For the thermal stability study, fusion protein T3-15-AP was incubated at 90 °C for 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min, followed by cooling to ambient temperature. The capacity of T3-15-AP binding to the coating antigen T5-BSA was subsequently evaluated by ELISA. Meanwhile, the T3-15 was treated in the same way as above and the binding ability to T3-BSA was evaluated. With regard to long-term storage, both the T3-15 and T3-15-AP were stored at ambient temperature without any protective reagents and the binding activities were determined on day 1, 4, 8, 12, 20, 30, and 70.

Matrix Effects

The one-step immunoassay was applied to urine samples from volunteers for monitoring human exposure to TBBPA. Matrix effects were evaluated following a simple dilution protocol. In brief, blank urine samples were directly diluted with DMSO to form the final percentages of 10, 20, 40, and 60% of DMSO/urine (v/v) and a series concentration of TBBPA were spiked into each. After gently shaking for 10 min, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 ×g for 10 min at ambient temperature and the supernatant was subjected to a one-step assay. The IC50 and A0 were compared with those of assays for TBBPA prepared in PBS containing different percentage of DMSO (10, 20, 40, and 60%) to evaluate the matrix effect.

Sample Analysis

Urine samples fortified with TBBPA (0.5, 1, 5, 20, 50, and 100 ng mL−1) were diluted with DMSO to reach a final percentage of 60% of DMSO/urine (v/v). After completely mixing, the diluted samples were centrifuged as above and the supernatants were subjected to the one-step assay using a calibration curve generated in PBS containing 60% DMSO.

For HPLC-MS/MS method, 10 μL of formic acid and 3 mL of ethyl acetate were added into 1 mL of urine sample, followed by vortexing and ultrasonication for 20 min. The organic layer was collected after centrifugation at 3000 ×g for 20 min. The extraction steps were repeated 3 times. The extracts were vacuum dried and reconstituted with MeOH (1 mL) for use. The analysis by HPLC-MS/MS (Waters/Micromass, Manchester, UK) was carried out as described previously 7, except for that the running time was 12 min on the HPLC column.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Production of VHH-AP Fusions

VHHs against TBBPA were biopanned from a T5-thyroglobulin immunized alpaca VHH-derived library with coating antigens T1-BSA, T3-BSA and T5-BSA in our previous study 7. Sixteen VHHs panned with T3-BSA were selected for AP fusion, because these VHHs showed better recognition to TBBPA than those from other coating antigens (data not shown). Based on the composition of CDRs, VHHs were distinguished into five groups. T3-4, T3-9, T3-12, T3-15, and T3-16 were chosen as a representative from each group (Figure S-2 in Supporting Information). AP is a highly attractive fusion partner due to both its high melting temperature (thermal stability) and the fact AP is a very stable colorimetric enzyme frequently utilized in ELISAs. The AP used in this study is 449 amino acids (~47 KD) in length containing double mutations, D153G and D330N, the activity of which (kcat = 3200 s−1) is 40- to 50-fold higher than that of the wild-type bacterial enzyme (kcat = 65–80 s−1) 35. The AP mutant-fusion proved to be easily produced in high yield in E. Coli., which served as a bifunctional immunoreagent combined recognition to most of the coating antigens while possessing high enzymatic activities (Figure 1). The expressed VHH-AP fusions with a 6×His tag were purified in a Ni-affinity chromatography protocol and one dominant band of around 62 KD (Figure S-3 in Supporting Information) was found upon SDS-PAGE analysis. The yield of each fusion protein by weight was around 30 mg from 1-L bacterial culture media.

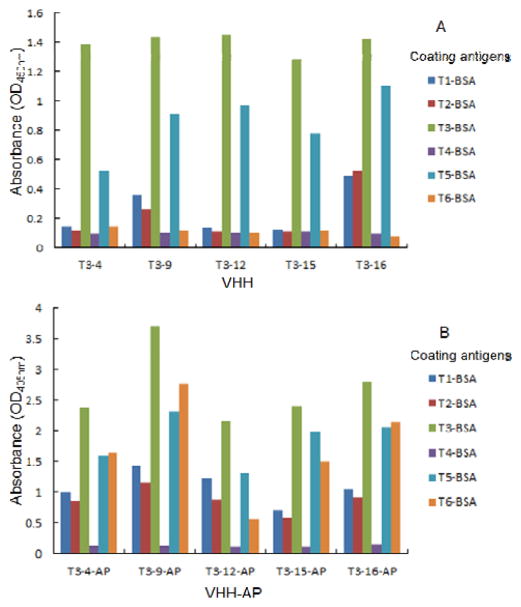

Figure 1.

The responses of VHH and VHH-AP clones to different coating antigens by ELISA (A: VHH; B: VHH-AP).

Binding Characteristics of VHH-AP Fusions

All the parental VHHs bound the coating antigens T3-BSA and T5-BSA, while T3-9 and T3-16 were also able to bind T1-BSA and T2-BSA (Figure 1A). However, the fusion proteins VHH-APs showed good binding to all the coating antigens except T4-BSA (Figure 1B). The failure of both VHH and VHH-AP fusion to recognize hapten T4 indicated the importance of the bromine atom in the generation of antibody in alpacas. The VHH-AP fusions showed better binding with haptens T3 and T5 than with haptens T1 and T2 (Figure 1B). The possible reason is that the immunizing hapten T5 is different from hapten T3 only having an additional 2-carbons in linker length, while different from haptens T1 and T2 in both linker length and spatial configuration (Figure S-1 in Supporting Information). It is noticeable that the TBBPA fragment-derived hapten T6 can be recognized by all VHH-AP fusions but not by parental VHHs (Figure 1). The paratope capacities of the VHH might be enlarged by fusion with the AP protein. It might be helpful in future studies to increase the paratope sizes and diversities. Because the bacterial AP usually exists as a symmetrical dimer 36, this could lead to unpredictable levels of complexity and aggregation 37. The dimerization and possible aggregation of the fusion protein likely contributed to the dramatic increase in affinity for the antigen 17, 38, 39. The binding affinities to TBBPA were evaluated for all VHH-AP fusions using one-step competitive ELISAs based on coating antigens T3-BSA and T5-BSA, both of which were well recognized by the VHH-AP fusions. The best assay sensitivity was obtained from T3-15-AP among all the VHH-AP fusions based on either T3-BSA or T5-BSA, indicating T3-15-AP had the highest binding affinity to TBBPA. Therefore, T3-15-AP was used for the remaining studies. The IC50 values of one-step assays for TBBPA varied in a range of 0.4–1.7 ng mL−1 with coating antigens T1-, T2-, T3-, T5- and T6-BSA. The best sensitivity (IC50 = 0.4 ng mL−1) was obtained from the combination of T3-15-AP and the homologous coating antigen T5-BSA. In our previous study, T3-15 showed almost equivalent sensitivity to TBBPA in both coating antigens T5-BSA and T3-BSA, with IC50 values of 0.54 and 0.41 ng mL−1, respectively 7. Nevertheless, T3-15-AP showed a little higher sensitivity to TBBPA in T5-BSA than in T3-BSA, with IC50 values of 0.39 and 0.69 ng mL−1, respectively (Figure S-4 in Supporting Information). The dimerization of AP fusion proteins possibly altered the binding ability of VHH, giving rise to the slight change for small molecule binding.

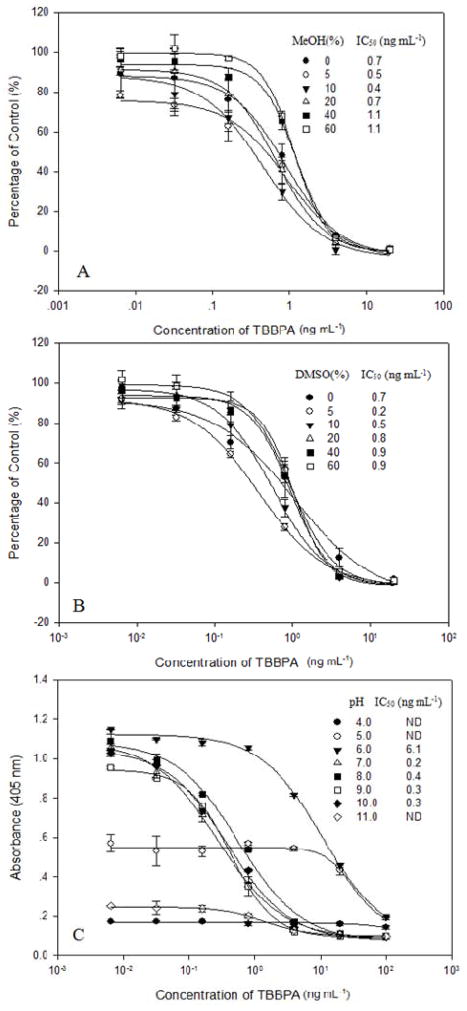

Optimization of the One-step ELISA

TBBPA, a lipophilic compound (Kow=4.5–5.3) 40, should be solubilized by organic solvents in immunoassay applications. Because the VHH was reported to be more tolerant to MeOH and DMSO than the pAb 8 and mAb 9, both of these solvents can be used as solubilizers to be miscible with water in the assay buffer. The optimal concentrations of coating antigen T5-BSA and T3-15-AP were determined by checkerboard titration. With the increase of MeOH in the range of 0–60%, A0 was typically enhanced from 1.02 to 1.46 A.U. and the IC50 values ranged from 0.4 to 1.1 ng mL−1. The best sensitivity was observed from the assay buffer containing 10% MeOH (IC50 = 0.4 ng mL−1) (Figure 2A). In the assay buffer with a range of 0–60% DMSO, the A0 changed between 1.41 and 1.53 A.U. and the IC50 values ranged from 0.2 to 0.9 ng mL−1 (Figure 2B). The best sensitivity was obtained at the concentration of 5% DMSO, with an A0 of 1.1 A.U. and an IC50 of 0.2 ng mL−1. Similar calibration curves were observed in the assays performed in high concentrations of DMSO (20–60%), showing less sensitivity (IC50 = 0.8–0.9 ng mL−1) and more narrow linear ranges in comparison with those in low concentrations of DMSO (5–10%). Solvent tolerance is one of the important considerations for the application of one-step ELISA for the lipophilic compounds. No obvious shift was observed for the performance of the one-step ELISAs at pH 7.0–10.0, as the A0 and IC50 varied slightly in a range of 1.07–1.22 A.U. and 0.20–0.40 ng mL−1, respectively (Figure 2C). Because the AP protein or the VHH might be denatured in the acidic or alkaline buffer, the fusion protein showed low binding affinity to TBBPA at pH ≤6.0 or ≥11.0 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of MeOH (A), DMSO (B) and pH (C) on the T3-15-AP based ELISA for TBBPA. ND: Not determined.

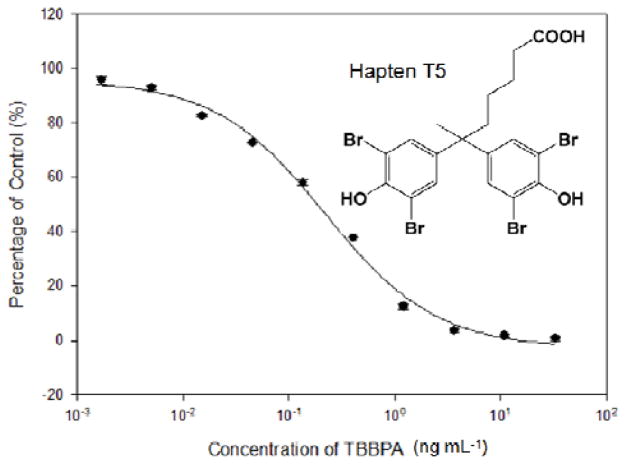

Figure 3 is a typical calibration curve of T3-15-AP based ELISA for TBBPA under optimized conditions (5% DMSO, pH 7.4). The assay had a linear range of 0.03–0.94 ng mL−1 (IC20–IC80) and an IC50 of 0.2 ng mL−1. Compared to the T3-15 based ELISA (10% MeOH, pH 7.4, IC50 = 0.4 ng mL−1), the sensitivity was increased 2-fold in the T3-15-AP based ELISA. In spite of the slight improvement of sensitivity, the one-step assay protocol was simplified and less immunoreagents were required in this assay than in the VHH-based ELISA.

Figure 3.

Calibration curve of T3-15-AP based one-step ELISA for TBBPA. T5 was used as both the immunizing hapten and the coating hapten conjugated with thyroglobulin and BSA, respectively. Values are the mean ± standard deviations of three well replicates.

Cross-reactivity

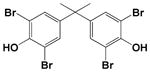

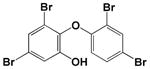

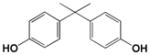

The specificity of the T3-15-AP was evaluated by comparing the IC50 value of TBBPA with that of its structural analogs, including 2,2′,6,6′-tetrabromobisphenol A diallyl ether (TBBPA-bAE), tetrabromobisphenol A bis(2-hydroxyethyl) ether (TBBPA-bOHEE)s, hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD), PBDEs (BDE-47, BDE-99), hydroxylated BDE-47 metabolites (5-OH-BDE-47 and 6-OH-BDE-47), 1,2-bis(pentabromodiphenyl) ethane (DBDPE) and bisphenol A (BPA), in one-step assays (Table 1). T3-15-AP showed similar specificity for TBBPA to the parental T3-15 7, having negligible cross-reactivity with the structural analogs (<0.1%). Multimerzation was reported to give rise to the effective affinity 17 on VHH-AP and the target, whereas, the specificity was likely determined in large part by the original antibody-analyte domain sites which appeared too rigid to be altered dramatically 3, 37 and the spatial position of bromine atoms and phenolic hydroxyl groups in TBBPA.

Table 1.

Cross-Reactivity of VHH T3-15-AP with TBBPA Atructural Analogues.

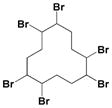

| Analogues | Structure | Cross-reactivity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| TBBPA |

|

100 |

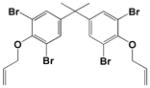

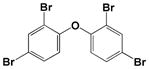

| TBBPA-bAE |

|

<0.1 |

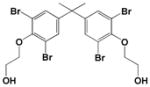

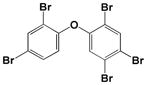

| TBBPA-bOHEE |

|

<0.1 |

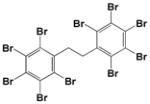

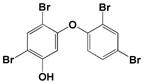

| BTBPE |

|

<0.1 |

| HBCD |

|

<0.1 |

| BDE-47 |

|

<0.1 |

| BDE-99 |

|

<0.1 |

| 5-OH-BDE 47 |

|

<0.1 |

| 6-OH-BDE 47 |

|

<0.1 |

| BPA |

|

<0.1 |

VHH-AP Stability

The stability of VHH-AP and VHH was evaluated by simultaneously testing the effects of both high and ambient temperature on the binding activities of T3-15-AP and T3-15 to T5-BSA and T3-BSA, respectively. T3-15 retained around 20% binding activity after heating at 90 °C for 90 min 7, while T3-15-AP lost half of its activity after only 10 min and almost all the binding activity after 20 min (Figure S-5A in Supporting Information). It has been reported that mutant E. coli APs showed a lower melting temperature of 87 °C 30 and thus the VHH-AP fusion proteins were less thermostable than the single domain antibodies 37, 39. The thermal denaturation of AP and the irreversible refolding process may interfere with the thermal stability of the fusion protein. In contrast, the fusion protein T3-15-AP demonstrated much more stability at ambient temperature than T3-15 (Figure S-5B in Supporting Information). T3-15 lost all binding ability to coating antigens by the fourth day, while T3-15-AP retained full binding activity even after incubating for 70 days, which is an important consideration for on-site applications. Besides the full stability of the mutant AP protein 35, excellent resistance of dimerized proteins to digestion by trypsin, chymotrypsin and serum proteases might also contribute to the long-term storage of T3-15-AP at ambient temperature 37. Although protection reagents, such as inhibitors of growth bacteria (e.g. glycerol and NaN3), can retard the loss of VHH activities at some levels (Figure S-6 in Supporting Information), the dimerization of VHH-AP is a natural way to stabilize the VHH.

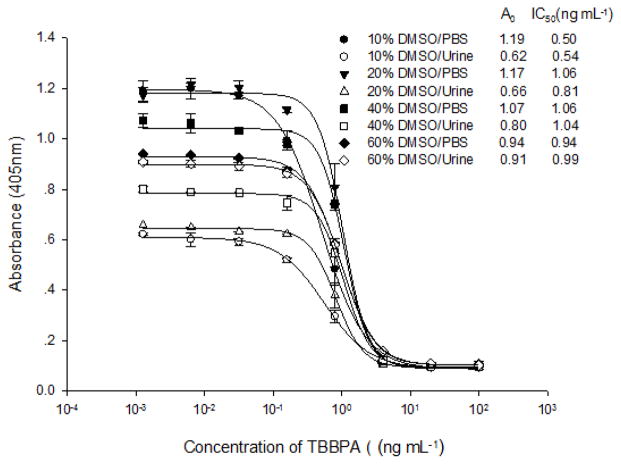

Matrix Effects

Dilution of sample extracts with assay buffer is one of the most common sample pretreatment methods to minimize matrix effects on ELISAs. The minimum dilution of sample to generate a standard curve similar to that generated in assay buffer was an indication of removal of matrix effects 41, 42. Because the VHH-AP based assay could be carried out in PBS containing up to 60% DMSO with an acceptable shift of IC50 values in a range of 0.2–0.9 ng mL−1 (Figure 2B), we presumed that the urine matrix effects could be minimized by directly diluting urine with DMSO, thus, improving the assay sensitivity in urine. The A0 value increased gradually from 0.62 A.U. in 10% of DMSO/urine (v/v) to 0.91 A.U. in 60% of DMSO/urine and IC50 values ranged from 0.54 to 1.04 ng mL−1 (Figure 4). At 60% of DMSO/urine, the responses of T3-15-AP to both T5-BSA and TBBPA were similar to those at 60% of DMSO/PBS (Figure 4). This suggests that urine matrix effects on the assay can be minimized by directly diluting with DMSO. A precipitate was produced with addition of DMSO. A possible reason is that a high concentration of DMSO not only solubilizes the TBBPA, but also denatures proteins or other materials sequestering TBBPA and precipitates salts and other materials giving rise to the matrix effects in urine. Another explanation might be that organic solvents activated a particle unfolding region of AP like myosin A 43 to produce more catalytic activity.

Figure 4.

Matrix effects of urine samples with different DMSO dilution on the one-step assay. The A0 and IC50 of calibration curves prepared in DMSO/urine were compared with those prepared in DMSO/PBS.

To match the assay requirement of urine samples diluted directly with DMSO, a new calibration curve of T3-15-AP based ELISA for TBBPA was generated in 60% of DMSO/PBS, showing an IC50 and an IC20 of 0.9 ng mL−1 and 0.23 ng mL−1, respectively. This calibration curve was used for sample analysis, with a minimum detection limit of 0.6 ng mL−1 in urine, which is more sensitive than other reports 44, 45.

Sample Analysis and Validation

Urine samples spiked with different concentrations of TBBPA were measured by both one-step ELISA and HPLC-MS/MS methods. Using the simple dilution protocol with 60% of DMSO in urine, the recoveries of TBBPA from urine by the one-step assay were in a range of 96.7–109.9% and the detectable concentration of TBBPA was 1.0 ng mL−1 (Table 2). In the HPLC-MS/MS method, TBBPA below 20 ng mL−1 was not detectable but satisfactory recoveries in a range of 98.9–106.1% were obtained from urine with 20–100 ng mL−1 TBBPA (Table 2). The results indicated that simple DMSO dilution is an acceptable pretreatment method for the detection of TBBPA in urine by the one-step ELISA which correlated well with HPLC-MS/MS.

Table 2.

Determination of TBBPA in urine samples by one-step ELISA and HPLC-MS/MS methods.

| Spiked TBBPA (ng mL−1 urine) | One-step ELISA | HPLC-MS/MS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured (ng mL−1) (Mean ± SD, n=3) | Average Recovery (%) | Measured (ng mL−1) (Mean ± SD, n=3) | Average Recovery (%) | |

| 0 | ND | -- | ND | -- |

| 0.5 | ND | -- | ND | -- |

| 1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 109.9 | ND | -- |

| 5 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 96.7 | ND | -- |

| 20 | 21.8 ± 0.8 | 108.8 | 19.8 ± 1.3 | 98.9 |

| 50 | 49.4 ± 2.8 | 98.7 | 50.2 ± 4.9 | 100.5 |

| 100 | 105.3 ± 5.8 | 105.3 | 106.1 ± 6.0 | 106.1 |

ND: Not detectable.

Occurrence data on TBBPA in human urine are scarce and limited to a study on the toxicokinetics of TBBPA in humans 45, in which the concentrations of unchanged TBBPA were below the LOD of a LC-MS/MS method (0.3 nmol/L–4 μmol/L) in all urine samples collected after a single oral dose of 0.1 mg kg−1 TBBPA in individuals. Although the majority of the TBBPA in urine was excreted as the glucuronide or sulfate conjugate, the excretion might be hydrolyzed to the parent TBBPA or concentrated for the determination of the total TBBPA in one-step assay. Because of the high sensitivity, time-saving and easy operation, the one-step ELISA has potential for the evaluation of human exposure to TBBPA.

CONCLUSION

This study, in terms of the bifunctional VHH-AP fusion protein, presents an innovative competitive immunoassay for determining TBBPA in a single step. Bacterial AP, due to its high catalytic efficiency and stability, was selected to fuse with anti-TBBPA VHHs for direct colorimetric detection. The homodimeric nature of AP may enlarge the paratopes, enhance the flexibility and heighten the effective affinity of fused VHHs. The resistance of fusion proteins to organic solvents, heat and pH was quite different from parental VHHs, but superior to most polyclonal and monoclonal immunoreagents. The difference in the sensitivity and specificity between the VHH and the VHH-AP based assays were not evident, illustrating genetic attachment of the AP did not negatively impact the function of the VHH. However, the recognition of diverse coating antigens by VHH-AP was broader than the parent VHH possibly due to broader paratopes formed by the AP fusion. Increasing the percentage of DMSO in urine sample helped to minimize matrix effects on the T3-15-AP based assay, allowing for the direct analysis of TBBPA in 60% of DMSO/urine with recoveries ranging from 96.7% to 109.9%. The sample pretreatment and assay protocol were simultaneously simplified. In all, this study demonstrated the utility of detecting small molecules using a genetically constructed VHH-AP immunoreagent, which reduced the number of steps needed in a conventional ELISA without altering sensitivity. In addition, the VHH-AP fusion protein worked successfully in a urine matrix, demonstrating its potential for monitoring chemical exposure through rapid urine analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program, P42ES04699, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, 2U50OH007550 and Ph.D. Programs Foundation of Ministry of Education of China, 20130008110019.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Supporting Information Available

Additional information as noted in text. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Harlow EL, Lane D. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1988. Antibodies. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SH, Zhang JB, Zhang ZP, Zhou YF, Yang RF, Chen J, Guo YC, You F, Zhang XE. Anal Chem. 2006;78:997–1004. doi: 10.1021/ac0512352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wels W, Harwerth IM, Zwickl M, Hardman N, Groner B, Hynes NE. Nat Biotechnol. 1992;10:1128–1132. doi: 10.1038/nbt1092-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki C, Ueda H, Suzuki E, Nagamune T. J Biochem. 1997;122:322–329. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willuda J, Honegger A, Waibel R, Schubiger PA, Stahel R, Zangemeister-Wittke U, Plückthun A. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5758–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bever CRS, Majkova Z, Radhakrishnan R, Suni I, McCoy M, Wang Y, Dechant J, Gee S, Hammock BD. Anal Chem. 2014;86:7875–7882. doi: 10.1021/ac501807j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J, Bever CRS, Majkova Z, Dechant JE, Yang J, Gee SJ, Xu T, Hammock BD. Anal Chem. 2014;86:8296–8302. doi: 10.1021/ac5017437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HJ, McCoy MR, Majkova Z, Dechant JE, Gee SJ, Tabares-da Rosa S, Gonzalez-Sapienza GG, Hammock BD. Anal Chem. 2012;84:1165–1171. doi: 10.1021/ac2030255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He T, Wang Y, Li P, Zhang Q, Lei J, Zhang Z, Ding X, Zhou H, Zhang W. Anal Chem. 2014;86:8873–8880. doi: 10.1021/ac502390c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muyldermans S, Baral TN, Retarnozzo VC, De Baetselier P, De Genst E, Kinne J, Leonhardt H, Magez S, Nguyen VK, Revets H, Rothbauer U, Stijemans B, Tillib S, Wernery U, Wyns L, Hassanzadeh-Ghassabeh G, Saerens D. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;128:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.10.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stijlemans B, Conrath K, Cortez-Retamozo V, Xong HV, Wyns L, Senter P, Revets H, De Baetselier P, Muyldermans S, Magez S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1256–1261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumoulin M, Conrath K, Van Meirhaeghe A, Meersman F, Heremans K, Frenken LG, Muyldermans S, Wyns L, Matagne A. Protein Sci. 2002;11:500–515. doi: 10.1110/ps.34602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zarschler K, Witecy S, Kapplusch F, Foerster C, Stephan H. Microb Cell Fact. 2013;12:97–110. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okazaki F, Aoki JI, Tabuchi S, Tanaka T, Ogino C, Kondo A. Appl Microbiol Biot. 2012;96:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ismaili A, Jalali-Javaran M, Rasaee MJ, Rahbarizadeh F, Forouzandeh-Moghadam M, Memari HR. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2007;47:11–19. doi: 10.1042/BA20060071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothbauer U, Zolghadr K, Tillib S, Nowak D, Schermelleh L, Gahl A, Backmann N, Conrath K, Muyldermans S, Cardoso MC, Leonhardt H. Nat Methods. 2006;3:887–889. doi: 10.1038/nmeth953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swain MD, Anderson GP, Serrano-Gonzalez J, Liu JL, Zabetakis D, Goldman ER. Anal Biochem. 2011;417:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Xu Y, Wan DB, Xiong YH, He ZY, Wang XX, Gee SJ, Ryu D, Hammock BD. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1387–1394. doi: 10.1021/ac504305z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herce HD, Deng W, Helma J, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. Nat Commu. 2013;4:2660–2668. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helma J, Schmidthals K, Lux V, Nuske S, Scholz AM, Krausslich H-G, Rothbauer U, Leonhardt H. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.BSEF. TBBPA factsheet. 2012 http://www.bsef.com/our-substances/tbbpa/about-tbbpa.

- 22.Guerra P, Eljarrat E, Barcelo D. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:2817–2824. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng J, Guo J, Zhou X, Zhou P, Fu X, Zhang W, Lin K. Environ Sci Pollut R. 2014;21:7656–7667. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2662-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson-Restrepo B, Adams DH, Kannan K. Chemosphere. 2008;70:1935–1944. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EFSA. EFSA Journal. 2011;9:2477–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colnot T, Kacew S, Dekant W. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88:553–573. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou X, Guo J, Zhang W, Zhou P, Deng J, Lin K. J Hazard Mater. 2014;273:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Brunete C, Miguel E, Tadeo JL. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:5497–5503. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo Q, Du Z, Zhang Y, Lu X, Wang J, Yu W. J Sep Sci. 2013;36:677–683. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201200730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris S, Allchin CR, Zegers BN, Haftka JJH, Boon JP, Belpaire C, Leonards PEG, Van Leeuwen SPJ, De Boer J. Environ Sci Technol. 2004;38:5497–5504. doi: 10.1021/es049640i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bu D, Zhuang H, Yang G, Ping X. Anal Methods. 2015;7:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu T, Wang J, Liu S-z, Lu C, Shelver WL, Li QX, Li J. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;751:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bu D, Zhuang H, Zhou X, Yang G. Talanta. 2014;120:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu C, Ou J, Cui Y, Wang L, Lv C, Liu K, Wang B, Xu T, Li QX, Liu S. Monoclonal Antibodies Immunodiagn Immunother. 2013;32:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mab.2012.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller BH, Lamoure C, Le Du MH, Cattolico L, Lajeunesse E, Lemaitre F, Pearson A, Ducancel F, Menez A, Boulain JC. Chembiochem. 2001;2:517–523. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010803)2:7/8<517::AID-CBIC517>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim EE, Wyckoff HW. Clin Chim Acta. 1990;186:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90035-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang JB, Tanha J, Hirama T, Khieu NH, To R, Hong TS, Stone E, Brisson JR, MacKenzie CR. J Mol Biol. 2004;335:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kortt AA, Dolezal O, Power BE, Hudson PJ. Biomol Eng. 2001;18:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0344(01)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu JL, Zabetakis D, Lee AB, Goldman ER, Anderson GP. J Immunol Methods. 2013;393:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO/ICPS Environmental Health Criteria 172: Tetrabromobisphenol A and Derivatives. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shelver WL, Smith DJ. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:3715–3721. doi: 10.1021/jf021175q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuang JC, Van Emon JM, Durnford J, Thomas K. Talanta. 2005;67:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2005.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brahms J, Kay CM. J Biol Chem. 1962;237:3449–3454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang MJ, Kim JH, Lee SK, Kang W, Kim HS, Lyoo WS, Jeong TC. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33:1797–1803. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schauer UMD, Völkel W, Dekant W. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91:49–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.