Abstract

Antimicrobial proteins/peptides (AMPs) are effectors of innate immune systems against pathogen infection in multicellular organisms. Over half of the AMPs reported so far come from insects, and these effectors act in concert to suppress or kill bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. In this work, we have identified 86 AMP genes in the Manduca sexta genome, most of which seem likely to be functional. They encode 15 cecropins, 6 moricins, 6 defensins, 3 gallerimycins, 4 X-tox splicing variants, 14 diapausins, 15 whey acidic protein homologs, 11 attacins, 1 gloverin, 4 lebocins, 6 lysozyme-related proteins, and 4 transferrins. Some of these genes (e.g. attacins, cecropins) constitute large clusters, likely arising after rounds of gene duplication. We compared the amino acid sequences of M. sexta AMPs with their homologs in other insects to reveal conserved structural features and phylogenetic relationships. Expression data showed that many of them are synthesized in fat body and midgut during the larval-pupal molt. Certain genes contain one or more predicted κB binding sites and other regulatory elements in their promoter regions, which may account for the dramatic mRNA level increases in fat body and hemocytes after an immune challenge. Consistent with these strong mRNA increases, many AMPs become highly abundant in the larval plasma at 24 h after the challenge, as demonstrated in our previous peptidomic study. Taken together, these data suggest the existence of a large repertoire of AMPs in M. sexta, whose expression is up-regulated via immune signaling pathways to fight off invading pathogens in a coordinated manner.

Keywords: insect immunity, comparative genomics, RNA-Seq, phylogenetic relationship, hemolymph proteins, tobacco hornworm

1. Introduction

Like other insects, the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta solely depends on innate immunity to defend against pathogens (i.e. viruses, bacteria, fungi), parasites, and parasitoid wasps (Kanost et al., 2004; Kanost and Nardi, 2010). Nonself recognition leads to cellular and humoral responses. Hemocytes engulf, nodulate, or encapsulate the invaders (Strand, 2008). Proteins in hemolymph and other body fluids mount humoral responses, including serine proteinase cascades that generate phenoloxidase and Spätzle for melanization and Toll pathway activation, respectively (Jiang et al., 2010). PO-generated reactive compounds (Zhao et al., 2011; Nappi and Christensen, 2005) and antimicrobial proteins/peptides (AMPs) (Yi et al., 2014) then kill the invading bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites.

As effectors of the innate immune system, AMPs damage plasma membranes or impair cellular activities of pathogens (Bulet et al., 2004; Brogden, 2005). Insect AMPs, first identified in a lepidopteran species (Hultmark et al., 1980), are classified into three major groups: 1) α-helical peptides such as cecropins and moricins; 2) cysteine-stabilized peptides including defensins, drosomycins, and gallerimycins; 3) Gly/Pro-rich proteins such as attacins, gloverins and lebocins (Reddy et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2014). During infection or immune challenge, AMP production is induced in hemocytes, fat body, and epithelial cells via the Toll, Imd and other pathways (Lemaitre and Hoffmann, 2007). Some AMPs (e.g. cecropins) are not produced in the absence of an elicitor, while others (e.g. lysozyme) are present at low constitutive levels and become highly abundant upon immune challenge. As a model insect for biochemical studies, M. sexta has been extensively investigated regarding its antimicrobial immune responses (Jiang et al., 2010). Several AMPs were identified, including cecropins (Dickinson et al., 1988), moricin (Dai et al., 2008), gloverin (Zhu et al., 2003), lebocins (Rayaprolu et al., 2010; Rao et al., 2012), and lysozyme (Mulnix and Dunn, 1994). As their action mechanisms and transcriptional regulation have been studied only in a few cases, such knowledge is fragmentary, lacking genomic and evolutionary perspectives.

Immunity-related genes have been analyzed at the genome level in Drosophila melanogaster (Irving et al., 2001), Anopheles gambiae (Christophides et al., 2002), Apis mellifera (Evans et al., 2006), Tribolium castaneum ((Zou et al., 2007), and Bombyx mori (Tanaka et al., 2008). Components of these systems are conserved to different degrees in these species, indicative of a common origin before the radiation of holometabolous insects. In contrast to the highly conserved intracellular signaling pathways, AMP genes have experienced drastic changes in numbers and sequences between and within insect orders (d'Alencon et al., 2013). For instance, Drosophila defensin and drosomycin have similar structures and overlapping functions, but they diverged into two families early in the evolution.

To better understand M. sexta immune effectors, their transcriptional regulation and evolutionary relationships with homologs in other insects, we performed an analysis of the AMP genes in the genome. Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees provided insights into their evolutionary history. Identification of putative immune responsive elements in the promoters is consistent with analysis of expression profiles based on the RNA-Seq data and protein abundance changes in larval hemolymph (Zhang et al., 2011 and 2014). We studied sequence conservation and structure-function relationships via molecular modeling. This genome-wide analysis enriches our knowledge on AMP gene evolution, expression regulation, protein processing, and potential roles during immune responses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene identification, sequence improvement, and feature prediction

Manduca Genome Assembly 1.0, gene models in Manduca Official Gene Sets 1.0 (OGS 1.0) and 2.0 (OGS 2.0), and Cufflinks Assembly 1.0 (Cufflinks 1.0) (X et al., 2015) was downloaded from Manduca Base (ftp://ftp.bioinformatics.ksu.edu/pub/Manduca/). AMP sequences from M. sexta and other insects were used as queries to search Cufflinks 1.0 using the TBLASTN algorithm with default settings. Hits with aligned regions longer than 20 residues and identity over 30% were retained for retrieving corresponding cDNA sequences. Correct open reading frames (ORFs) in the retrieved sequences were identified using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). Errors resulting from problematic regions (e.g. NNN…) in Manduca Genome Assembly 1.0 were corrected after BLASTN search of Manduca Oases and Trinity Assemblies 3.0 (http://darwin.biochem.okstate.edu/blast/blast_links.html). The two genome-independent RNA-Seq assemblies (Cao and Jiang, 2015) were developed to cross gaps between genome scaffolds or contigs, to detect errors in the genome assembly and gene models, and to profile expression of genes. The manually improved sequences were incorporated into OGS 1.0 and in many cases verified by Manduca OGS 2.0 and Cufflinks Assembly 1.0b (http://darwin.biochem.okstate.edu/blast/blast_links.html). The latter was assembled based on all 52 cDNA libraries; Cufflinks 1.0 was based on 33 of the libraries. To uncover all genes in a cluster, which sometimes are too similar to distinguish by Cufflinks 1.0/1.0b, the relevant genome contigs were manually examined to identify exons based on the GT-AG rule and sequence alignment. All improved sequences were further validated by BLASTP homolog search of GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Conserved domains were identified using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/smart/set_mode.cgi) and InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/pfa/iprscan/). Signal peptides were predicted using SignalP4.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/) (Petersen et al., 2011) or Signal-3L (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/Signal-3L/) (Shen and Chou, 2007).

2.2. Sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments of AMPs from M. sexta and other insects (retrieved from GenBank at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were performed using MUSCLE, a module of MEGA 6.0 (http://www.megasoftware.net). The following parameters were used: refining alignment, gap opening penalty = −2.9, gap extension penalty = 0, hydrophobicity multiplier = 1.2, maximum iterations = 100, clustering method (for iterations 1 and 2) = UPGMB, and maximum diagonal length = 24. The aligned sequences were used to construct neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees using MEGA6.0 with bootstrap method for the phylogeny test (1000 replications Poisson model, uniform rates, and complete deletion of gaps or missing data).

2.3. Protein structure modeling

Amino acid sequences of the mature M. sexta AMPs were submitted to the I-TASSER server (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/) for protein 3D-structure prediction (Zhang, 2008). Models were built based on multiple-threading alignments by LOMETS and iterative TASSER simulations (Roy et al., 2010). A representative model was chosen for the production of molecular graphics using PyMol (DeLano Scientific, Palo Alto, CA).

2.4. Gene expression profiling

The 52 cDNA libraries, representing mRNA samples from whole insects, organs or tissues at various life stages, were constructed and sequenced by Illumina technology (X et al., 2015). Reads from the individual RNA-Seq datasets were trimmed to 50 bp and mapped to the updated OGS 1.0 (Section 2.1) using Bowtie (0.12.8) (Langmead et al, 2009). Numbers of the mapped reads were used to calculate FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) by RSEM (1.2.12) (Li and Dewey, 2011) for interlibrary comparisons. Hierarchical clustering of the log2(FPKM+1) values was performed using MultiExperiment Viewer (v4.9) (http://www.tm4.org/mev.html) with the Pearson correlation-based metric and average linkage clustering method. To study transcript changes after immune challenge, the entire set of AMP sequences were used as queries to search for corresponding contigs in the CIFH09 database (http://darwin.biochem.okstate.edu/blast/blast_links.html) (Zhang et al., 2011) by TBLASTN. The numbers of CF, CH, IF, and IH reads (C for control, I for induced after injection of bacteria, F for fat body, H for hemocytes) assembled into these contigs were retrieved for normalization and calculation of IF/CF and IH/CH ratios. When a polypeptide sequence corresponded to two or more contigs, sums of the normalized read numbers were used to calculate its relative mRNA abundances in fat body and hemocytes (Gunaratna and Jiang, 2013).

2.5. Promoter analysis

Potential transcription factor binding sites in the 1000 bp region before the transcription initiation site were searched using MacVector Sequence Analysis Software (Oxford Molecular Ltd.). Sequences, positions, and strand polarities of the perfectly matched GATA (WGATAR), R1 (KKGNNCTTTY), and CATTW boxes were documented. NF-κB motifs (GGGRAYYYYY) with 0, 1 or 2 mismatches were also identified.

3. Results

3.1. α-helical AMPs: cecropins and moricins

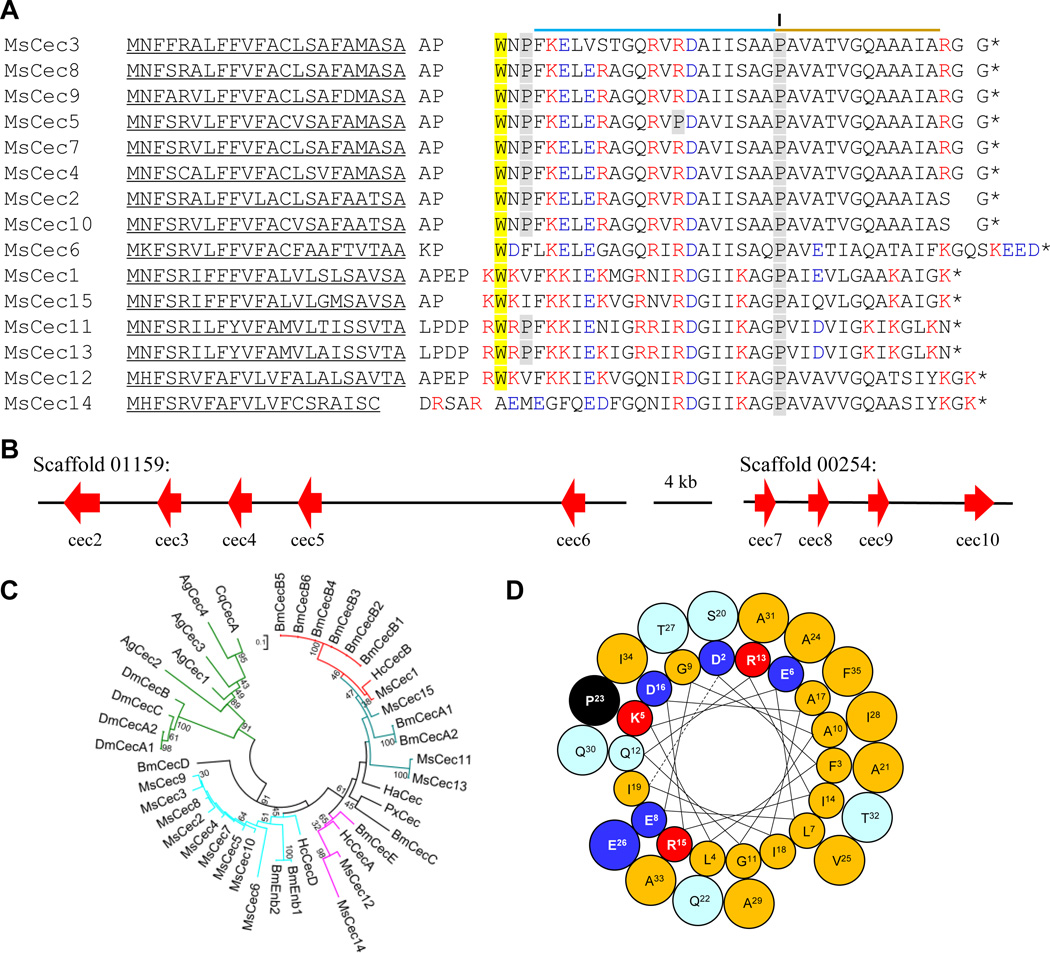

Most cecropins are cationic antibacterial peptides with a kinked α-helix (Steiner et al., 1981; Yi et al., 2014). We have identified fifteen cecropin genes in the Manduca genome. Cecropins 4/7, 8, and 9 correspond to bactericidin-2, 3, and 4 (Dickinson et al., 1988), respectively. After removal of a secretion signal peptide, two or four residues are likely removed by an amino dipeptidase that cuts after Xaa-Pro to generate the mature AMPs often with a Trp residue at position 1 or 2 (Fig. 1A). This Trp, which may not be required for the bactericidal activity (Vizioli et al., 2000), is conserved in all but cecropin 14. Secondary structure prediction indicates a large portion of the mature cecropins (36 to 43 residues long) is α-helical. A Pro, which is absolutely conserved in the known lepidopteran cecropins, may bend the long helical structure into N- (19 to 22 residues) and C-terminal (11/12 residues) parts. In cecropin 5, the N-terminal part is likely interrupted by another Pro. We further predict that the C-terminal Gly in cecropins 2~5, 7~10 is cleaved by a lyase to leave a carboxyl-terminal amide, shielding the negative charge of the carboxyl group that reduces their activity (Lee et al., 1989). The calculated isoelectric points (pI) of cecropins 1~5, 7~13, and 15 range from 10.5 to 11.5; those of cecropins 6 and 14 are 4.6 and 6.3, respectively. Perhaps, cecropins with different properties (e.g. pI, length, and Pro) but similar expression patterns may act upon bacteria with different surface properties. The patterns of cecropin gene duplications and sequence divergence provide some information about their molecular evolution (Fig. 1B). Cecropins 2~6 form one gene cluster on Scaffold 01159, whereas cecropins 7~10 form another on Scaffold 00254. The products of these M. sexta cecropin genes are most similar to Hyalophora cecropia cecropin D and B. mori enbocins (Fig. 1C). M. sexta cecropin 1 seems to form an orthologous group with H. cecropia cecropin B and B. mori cecropins B1~B5. M. sexta cecropins 12 and 14 form a clade with B. mori cecropin E and H. cecropia cecropin A. M. sexta cecropins 11, 13, 15 and B. mori cecropin A’s are close homologs. The moth cecropins differ significantly in sequence from their homologs in the dipteran species.

Fig. 1. M. sexta cecropins.

(A) Aligned sequences. Signal peptides are underlined. The (Xaa-Pro)1~2 at the amino terminus and Gly at the carboxyl terminus are separated by spaces from the mature peptides. Removal of the N- and C-terminal extensions was confirmed in cecropin 4/7 (bactericidin-2), cecropin 8 (bactericidin-3), and cecropin 9 (bactericidin-4) (Dickinson et al., 1988). The conserved Trp and Pro residues are shaded yellow and gray, respectively. The relatively hydrophilic N- and hydrophobic C-terminal helices are indicated by cyan and yellow lines, respectively. (B) Two clusters of nine genes (cec2~6 and cec7~10) located on the scaffolds with orientation and size indicated by red arrows. (C) Phylogenetic relationships of cecropins from A. gambiae (Ag), B. mori (Bm), Culex quinquefasciatus (Cq), D. melanogaster (Dm), H. armigera (Ha), H. cecropia (Hc), M. sexta (Ms), and Plutella xylostella (Px). Branches A, B, D and E are colored in teal, red, cyan and pink, respectively, for the moth cecropins that are substantially different from the dipteran cecropins in the green branch. (D) Helical wheel projection of M. sexta cecropin 6. In the two α-helices (Asp2 to Gln22; Ala24 to Phe35), hydrophobic and hydrophilic side chains are shown in cyan and yellow, respectively. The helix breaker (Pro23) is in black. Lys/Arg: red; Asp/Glu: blue.

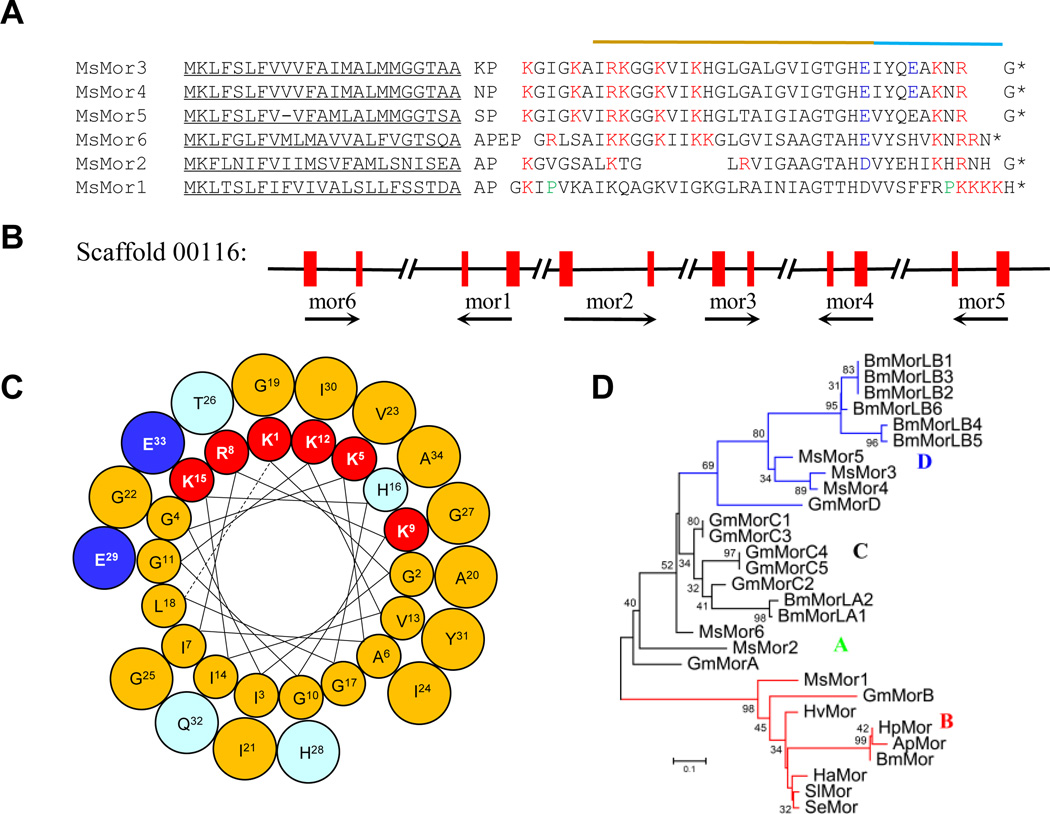

Moricins are cationic AMPs, which kill Gram-positive and -negative bacteria at low concentrations and have been found only in lepidopteran insects (Hara and Yamakawa, 1995a; Yi et al., 2014). Similar to cecropins, moricin maturation may involve signal peptide removal, amino dipeptidase processing, and C-terminal amidation by processing of a Gly residue (Fig. 2A). We identified a cluster of six moricin genes on Scaffold 00116, each encoding a precursor that becomes a mature peptide 32 to 42 residues long (Fig. 2B). Based on comparisons with the M. sexta moricin three-dimensional structure (Dai et al., 2008) and secondary structure predictions, moricins 2~6 may each form a 6~8-turn α-helix. Helical wheel projections clearly demonstrate the amphipathicity of moricins (Fig. 2C) and cecropins (Fig. 1D), critical for forming pores in bacterial plasma membrane. However, there are major structural differences between them. Lacking the conserved Pro, the middle portion of the moricins may form an uninterrupted α-helix. The mature cecropins and moricins likely form random coils in aqueous solution and organize into a (kinked) α-helix in a hydrophobic environment. The differences in amphipathicity and charge distribution may account for their distinct efficacies on various bacteria. The moricin gene family has experienced major expansion in G. mellonella, B. mori, and M. sexta after divergence of these species (Fig. 2D). M. sexta moricin 1 and G. mellonella moricin B may represent the most ancient clade B that includes the other moth moricins. M. sexta moricin 2 and G. mellonella moricin A are close homologs in clade A. M. sexta moricin 6, G. mellonella moricins C1~C5, B. mori moricin A1 and A2 cluster together in clade C. Clade D includes M. sexta moricins 3~5, G. mellonella moricin D, and B. mori moricins B1~B6.

Fig. 2. M. sexta moricins.

(A) Aligned sequences. Signal peptides are underlined. The (Xaa-Pro)1~2 at amino terminus and Gly at carboxyl terminus are separated by spaces from the mature peptides. The acidic, basic and Pro residues are in blue, red and green, respectively. The relatively hydrophobic N- and hydrophilic C-terminal helical portions are marked by yellow and cyan lines, respectively. (B) A cluster of six genes (mor1~6) with orientation and exon indicated by black arrows and red bars, respectively. (C) Helical wheel projection of M. sexta moricin 4. In the α-helix (Lys1 to Ala34), hydrophobic and hydrophilic side chains are shown in cyan and yellow, respectively. Lys/Arg: red; Asp/Glu: blue. (D) Phylogenetic relationships of moricins from Antheraea pernyi (Ap), B. mori (Bm), G. mellonella (Gm), H. armigera (Ha), Hyblaea puera (Hp), H. virescens (Hv), M. sexta (Ms), S. exigua (Se), and Spodoptera litura (Sl).

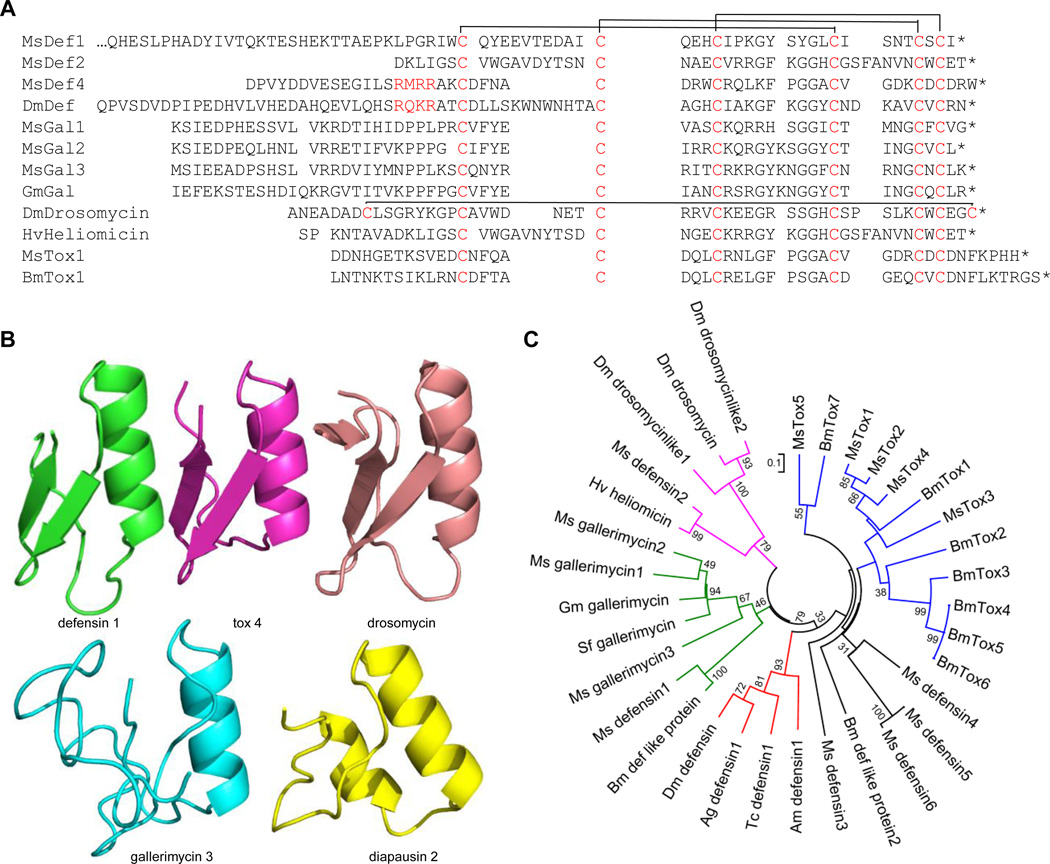

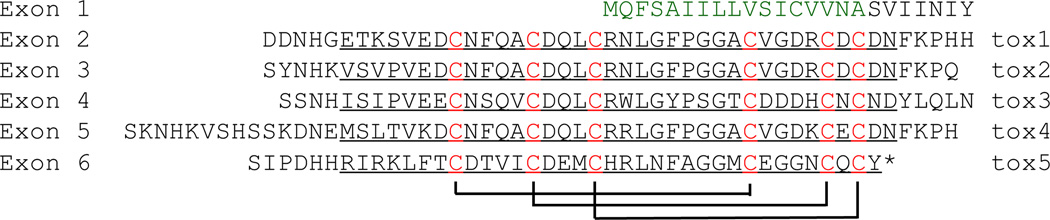

3.2. Cys-stabilized AMPs: defensins, gallerimycins, X-tox’s, diapausins, and WAPs

Insect defensins and their homologs (e.g. gallerimycin, X-tox) constitute a diverse family of AMPs, most of which are active against bacteria or fungi (Matsuyama and Natori, 1988; Schuhmann et al., 2003; Tanaka et al., 2003; d'Alencon et al., 2013; Zhu and Gao, 2013). These molecules may adopt an αβ fold stabilized by three disulfide bonds between Cys-1 and 4, Cys-2 and 5, Cys-3 and 6 (Fig. 3A). We have identified six defensins, three gallerimycins, and four X-tox variants in M. sexta. Their structure models, along with the drosomycin structure (Landon et al., 1997), suggest that the disulfide linkage pattern and the αβ fold are mostly conserved (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, sequence variations and lineage-specific family expansions are remarkable for these and other remotely related proteins (e.g. diapausins). Indeed, since M. sexta defensin 1 and B. mori defensin-like protein are so different in sequence from the dipteran, hymenopteran and coleopteran defensins (Fig. 3C), they were not thought to exist in Lepidoptera for a long time (Lamberty et al., 1999). These two moth proteins have a ~40-residue extension at the N-terminus. Lacking the extension, M. sexta defensin 2 is closely similar to the antifungal heliomicin (Lamberty et al., 1999) but less so to drosomycin (Fehlbaum et al., 1994). M. sexta defensins 3~6, similar to B. mori defensin-like protein 2, have an acidic N-terminal extension 42, 20, 22 and 22 residues long, respectively. A part of M. sexta defensin 4 (Fig. 3A) and B. mori defensin-like protein 2 are probably removed by an intracellular processing enzyme that cuts after RXXR. Because of their similarity with known antifungal peptides, it would be interesting to test if M. sexta defensins 1~6 kill fungal pathogens. M. sexta gallerimycins 1~3 are in a monophyletic group along with other lepidopteran gallerimycins (Fig. 3C) and their predicted connectivity of disulfide bonds (Fig. 3A) needs experimental verification. In summary, the drastic diversification of defensin sequences is consistent with the extensive speciation and adaptation of insects in different environments.

Fig. 3. Evolution of defensin-related proteins in insects.

(A) Aligned sequences. Conserved Cys residues (Cys-1~6, red) in the mature peptides form three disulfide bonds as depicted on top of the two groups. Another bond between Cys-0 and Cys-7 in drosomycin is also shown. The N-terminal pro-region in Drosophila defensin and M. sexta defensin 4 is removed by an intracellular protease that cuts after RXXR (red). (B) Structure models of M. sexta defension 1 (green), 5-tox domain 4 (pink), gallerimycin 3 (cyan) and diapausin (yellow). They resemble the Cys-stabilized αβ fold in drosomycin (brown). (C) Phylogenetic tree of drosomycins (pink), defensins (red, black, etc.), gallerimycins (green), and X-tox domains (blue) from various insects including A. gambiae (Ag), A. mellifera (Am), B. mori (Bm), D. melanogaster (Dm), Epiphyas postvittana (Ep), G. atrocyanea (Ga), G. mellonella (Gm), H. virescens (Hv), M. sexta (Ms), S. exigua (Se), Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf), and S. litura (Sl).

As defensin homologs, X-tox proteins in lepidopteran insects contain multiple copies of the Cys-stabilized αβ fold (Fig. 3B) (d'Alencon et al., 2013). Instead of gene duplication, they arose from exon duplication, sequence divergence, and alternative splicing. The M. sexta 5-tox gene contains six exons, exons 2 through 6 each coding for one tox domain (Fig. 4). Based on the RNA-Seq data, skipping of exon 3, exon 4, or both, by alternative splicing results in transcripts of 4-tox, 4-tox’, and 3-tox, respectively. Sequence comparison suggests that exon duplication yielded domains 1, 2 and 4, and similar events gave rise to the domains 3~6 in B. mori 7-tox (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 4. M. sexta 5-tox protein.

The amino acid sequence is divided into six regions encoded by exons 1~6, correspondingly. Exon 3, 4, or both are skipped in some transcripts through alternative splicing. Following the signal peptide (green), tox domain-1~5 (underlined) are identified in regions 2~6. Based on structure modeling, three disulfide bonds are formed between the conserved Cys residues (red) as shown.

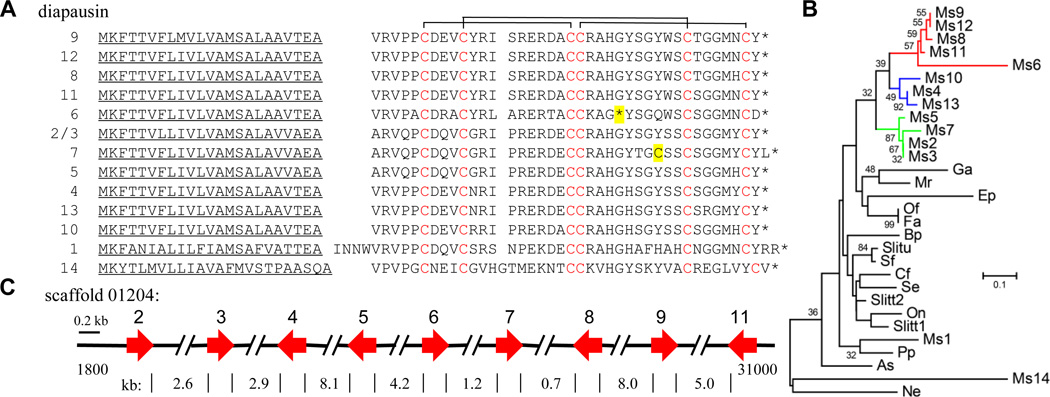

We identified a family of 14 peptides homologous to a protein named diapausin, from a beetle, Gastrophysa atrocyanea, which was identified in hemolymph of diapausing individuals (Tanaka et al., 2003). However, silencing of the G. atrocyanea diapausin gene expression did not affect diapause onset or maintenance, but the peptide was found to block fungal growth (Tanaka and Suzuki, 2005). We named the homologous peptides in M. sexta diapausins 1~14. In an independent study, diapausin 1 isolated from M. sexta hemolymph displays an antifungal activity (Al Souhail and Kanost, unpublished results), which may protect insects from fungal infection during diapause and other prolonged stationary stages. The diapausin 6 gene has a pre-mature stop codon and, thus, may represent a pseudogene encoding an inactive product (Fig. 5A). The other thirteen diapausins are encoded by a single exon, all have a secretion signal sequence and a mature peptide containing six conserved Cys residues, which likely form three disulfide bonds as observed in G. atrocyanea diapausin (Tanaka et al., 2003). Diapausins 2 and 3 are identical in amino acid sequence. Diapausin 7 has an extra Cys between Cys-4 and Cys-5. Diapausin 1 is orthologous to diapausins from G. atrocyanea and insects from other orders (Fig. 5B), including Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Neuroptera, Mecoptera, Dermaptera, Odonata, Hemiptera, Dictyoptera, and Plecoptera. In contrast to a single diapausin EST found in almost all of these insects, the family expansion in the lineage of M. sexta is remarkable. As a result of likely fairly recent gene duplications, diapausins 2~9 and 11 form a gene cluster (Fig. 5C) with amino acid sequence identity ranging from 65 to 100%.

Fig. 5. M. sexta diapausins.

(A) Aligned sequences. After the signal peptide (underlined), conserved Cys residues (Cys-1~6, red) in the mature diapausins form three disulfide bonds as depicted on the top (predicted from the structure of homologous diapausin (Kouno et al., 2007) The orphan Cys in diapausin 7 and the pre-mature stop codon (*) in diapausin 6 are highlighted yellow. (B) Phylogenetic relationships of diapausins in Agrotis segetum (As), Bittacus pilicornis (Bp), Choristoneura fumiferana (Cf), E. postvittana (Ep), Forficula auricularia (Fa), G. atrocyanea (Ga), Mantis religiosa (Mr), M. sexta (Ms1~14), Notostiva elongate (Ne), Osmylus fulvicephalus (Of), Ostrinia nubilalis (On), Pseudomallada prasinus (Pp), S. exigua (Se), S. frugiperda (Sf), S. litura (Slitu), and S. littoralis (Slitt) (C) A cluster of nine M. sexta diapausin genes with orientation and size indicated by red arrows.

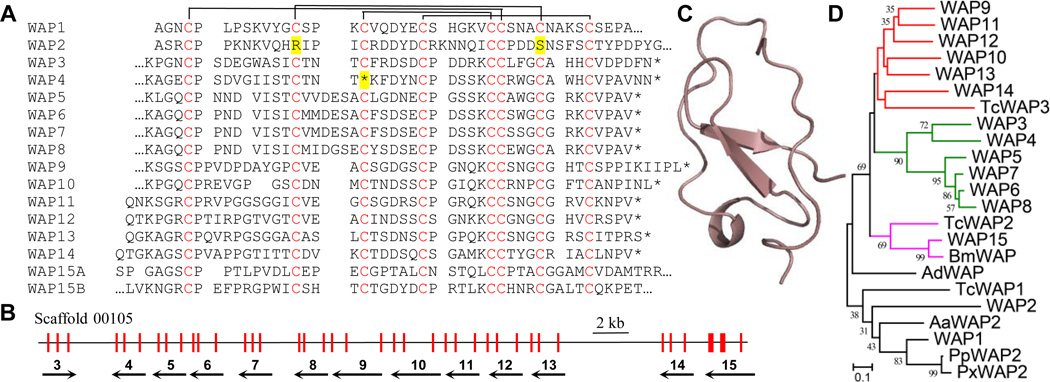

Whey acidic proteins (WAPs) and their homologs are involved in proteinase inhibition and microbe killing in vertebrates and invertebrates (Ranganathan et al., 1999; Smith et al., 2008). There are fifteen homologs in M. sexta, simply named WAP1~15 (Fig. 6A). WAP1~3, 5~14 have one 4-disulfide core structure (i.e. WAP domain), WAP15 has two core structures, and WAP4 stops immaturely. The eight Cys residues in typical WAP domains form disulfide bonds between 1–6, 2–7, 3–5 and 4–8, as demonstrated in human seminal plasma inhibitor (Grutter et al., 1988), but Cys-2 and 7 in WAP2 are substituted by Arg and Ser, respectively. The M. sexta WAP genes all contain three exons – exon 2 of WAP1~2, exon 3 of WAP3~14, exon 2 and exon 3 of WAP15 each encodes a WAP domain (Fig. 6B). WAP3~15 genes form a large cluster on Scaffold 00105; WAP1 and WAP2 are on Scaffold 00094. The disulfide linkage pattern in WAP domains differs greatly from those of the defensin-like proteins (Fig. 3), and so do their predicted structures, represented by WAP14 (Fig. 6C). M. sexta WAP1, WAP2 and their orthologs in A. aegypti, A. dorsata, P. polytes, P. xuthus, and T. castaneum (Fig. 6D) all have a C-terminal extension containing X3CX4CX5CX10CX3 (data not shown). M. sexta WAP15, B. mori WAP and T. castaneum WAP2 form another orthologous group with two WAP domains. WAP3~8 have an N-terminal extension (11 or 12 residues), longer than that in WAP9~14 (2 or 3 residues). The major family expansion suggests that WAPs play roles in insect physiological processes including immunity.

Fig. 6. Homologs of whey acidic protein (WAPs) in M. sexta.

(A) Aligned sequences. Conserved Cys residues (Cys-1~8, red) in the mature peptides may form four disulfide bonds as depicted. Extensions (…) in some of the homologs are deleted for clarity. Domains A and B in WAP15 are shown separately. The substituted Cys-2 and Cys-7 in WAP2 and the pre-mature stop codon (*) in WAP4 gene are highlighted yellow. (B) A cluster of thirteen genes (WAP3~15), with orientations and exons indicated by black arrows and red bars, respectively. (C) Structure model of M. sexta WAP14. (D) Phylogenetic relationships of four groups of WAP homologs (red, green, purple, and black) in A. aegypti (Aa), Apis dorsata (Ad), M. sexta (Ms), Papilio polytes (Pp), Papilio xuthus (Px), and T. castaneum (Tc).

3.3. Gly- and Pro-rich AMPs: gloverin, attacins and lebocins

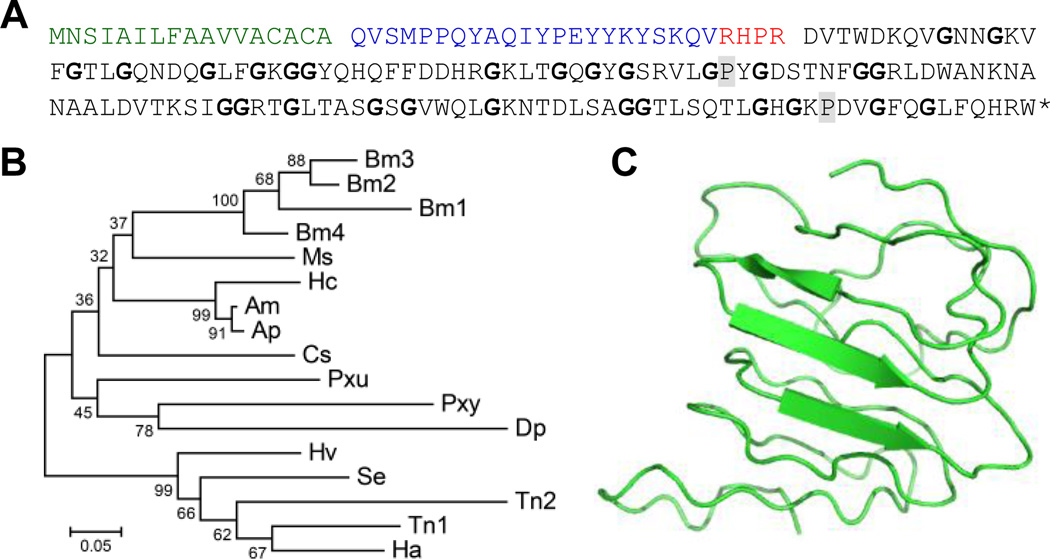

Gloverins from lepidopteran insects are Gly-rich AMPs active mostly against Gram-negative bacteria (Axen et al., 1997; Yi et al., 2014). They are synthesized as pre-pro-proteins and processed by intracellular proteinases (Fig. 7A). M. sexta gloverin, encoded by a single gene in the genome, is a 132-residue protein containing 21.2% Gly, like the other mature gloverins (130~135 residues long, 16.4~20.0% Gly). Seven gloverins from B. mori, H. armigera, H. virescens, and P. xuthus are slightly acidic (average pI: 6.57; range: 5.49~7.21), while ten from the other species are basic (average: 8.94, range: 8.16~9.64). Therefore, the role of overall charge property in their mode of action seems uncertain for gloverins. Multiple sequence alignment yields a phylogenetic tree consistent with the corresponding species tree (Fig. 7B). Molecular modeling suggests the gloverin adopts a loose structure bearing a 3-trand β sheet (Fig. 7C), and the high Gly content is likely responsible for the structural flexibility of M. sexta gloverin.

Fig. 7. M. sexta gloverin and its homologs in lepidopteran insects.

(A) Sequence features. As represented by M. sexta gloverin, all its homologs have a signal peptide (green) followed by a pro-region ending with RXXR (red). Removal of the pro-region by an intracellular processing enzyme has been confirmed in H. cecropia and H. armigera gloverins (Axen et al., 1997; Mackintosh et al., 1998). The mature proteins are rich in Gly (cyan) and, in most cases, cationic. (B) Phylogenetic relationships of mature gloverins from Antheraea mylitta (Am), A. pernyi (Ap), B. mori (Bm), Chilo suppressalis (Cs), Danaus plexippus (Dp), H. armigera (Ha), Heliothis virescens (Hv), H. cecropia (Hc), P. xuthus (Pxu), P. xylostella (Pxy), S. exigua (Se), and T. ni (Tn). (C) Model of M. sexta mature gloverin.

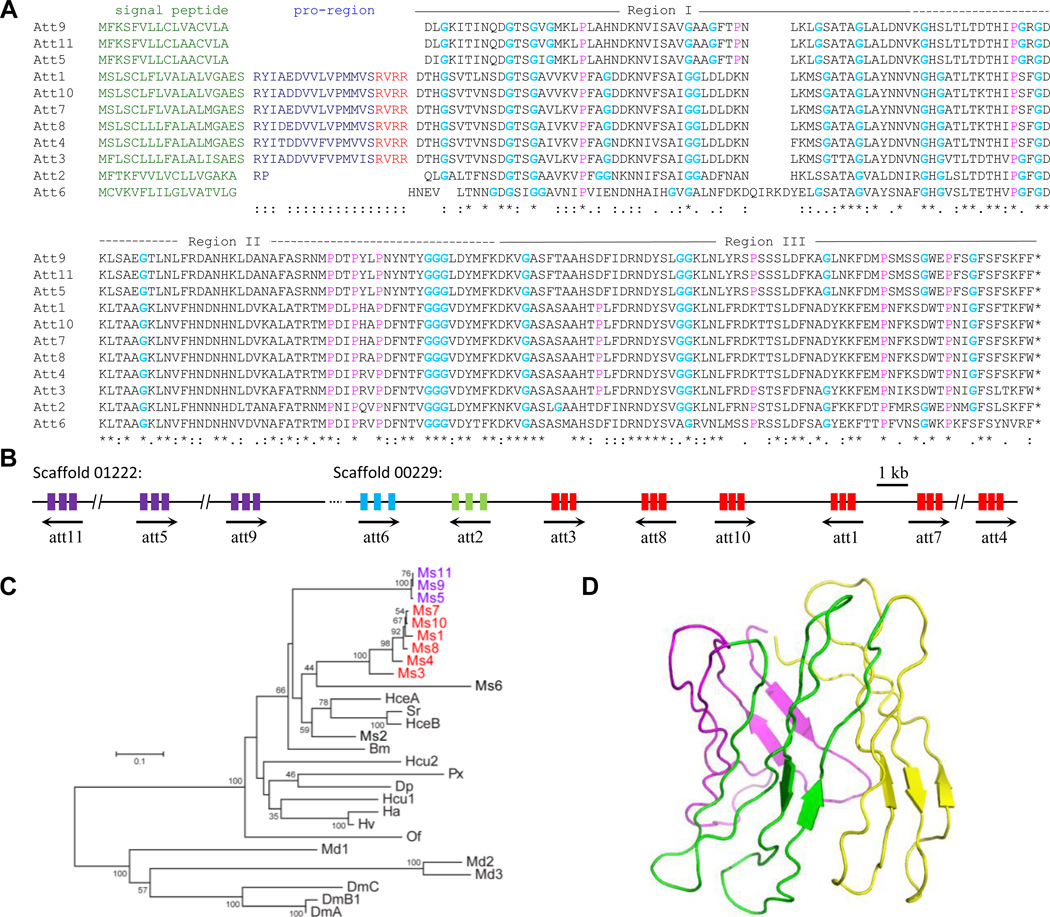

Like gloverins, attacins are Gly-rich AMPs active typically against Gram-negative bacteria (Hultmark et al., 1983). There are eleven attacins encoded by the M. sexta genome. All of them contain a signal peptide, and attacins 1, 3, 4, 7, 8 and 10 have a pro-region, likely removed by a convertase that cuts after RXXR for maturation (Fig. 8A). Gly contents of attacins 1~11 (10.1~12.3%) were lower than those of the gloverins (16.4~21.2%), and there is no clear homology between attacins and gloverins, based on our sequence comparison (data not shown). Attacin genes 5, 9, and 11 reside on Scaffold 01222; attacins 1~4, 6~8 and 10 genes form another cluster on Scaffold 00229 (Fig. 8B). Consistent with the gene loci, phylogenetic analysis reveals evolutionary history of the two lineages: 5-9-11 and 3-4-1-7-8-10 (Fig. 8C). Attacins 2 and 6 seem to have branched off earlier from the common ancestor and, like attacins 5, 9 and11, do not contain a pro-region. Attacin 2 (pI: 9.48) is closely related to attacins from the other insects, which are all basic (average and range of pIs: 9.41, 8.00~10.53) except for H. cecropia acidic attacin (pI: 6.03). The latter is more similar to attacins 1, 3~11 in sequence and pI (average: 6.73; range: 5.85~7.19). M. sexta attacin 6 (pI: 5.85) went through considerable sequence divergence while rounds of gene duplication gave rise to the other nine acidic or neutral attains. As discovered in D. melanogaster (Hedengren et al., 2000), mature attacins contains three domains: N, G1 and G2. Molecular modeling suggests that the three regions together form an antiparallel β-barrel stabilized by hydrogen bonds between the peptide strands (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8. M. sexta attacins.

(A) Aligned sequences. The secretion signal peptides (green) are followed by a pro-region (blue) ending with RXXR (red), a recognition site of intracellular processing enzymes, in attacins 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 10. Mature attacins consist of three regions rich in Gly (bold) as well as Pro (pink). Identical, highly and moderately conserved positions are marked “*” “:” and “.”, respectively. (B) Two clusters of attacin genes with orientations and exons indicated by black arrows and colored bars, respectively. (C) Neighbor-joining tree of the attacins from some lepidopteran and dipteran insects. The M. sexta att5, 9, 11 gene cluster (purple) (panel B), as well as att1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10 cluster (red), is consistent with the close phylogenetic relationships. (D) Structure model of M. sexta attacin 1. Regions I (pink), II (green) and III (yellow) together form a β-barrel-like structure stabilized by hydrogen bonds between peptide strands.

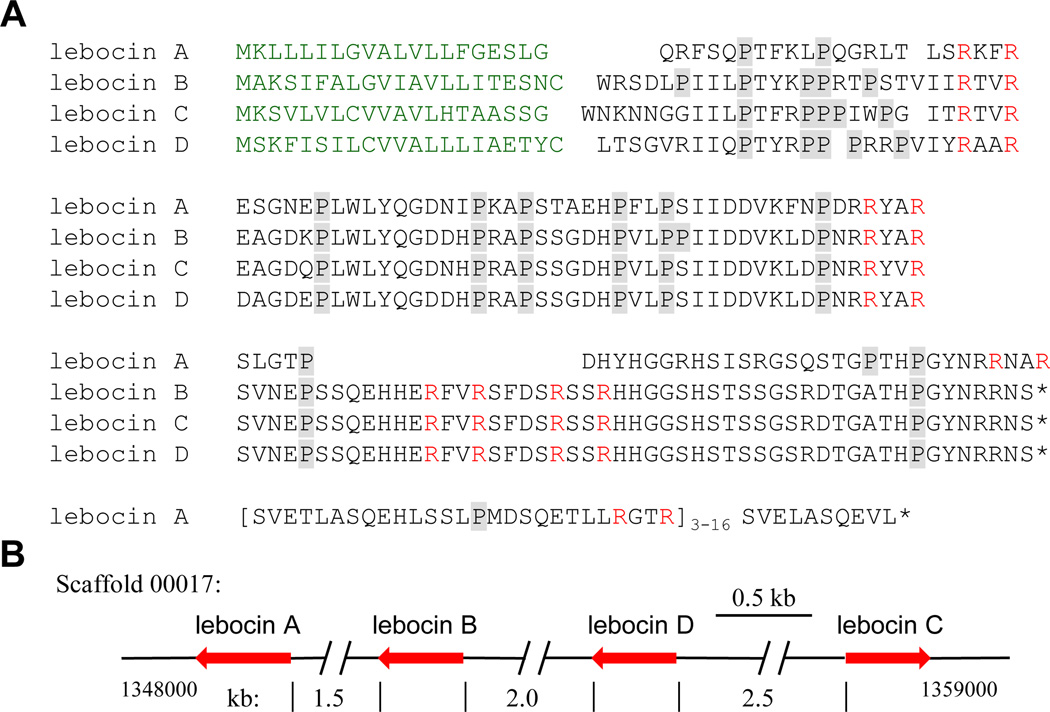

Lebocins are Pro-rich peptides active against bacteria (Yi et al., 2014). While lebocin and its cDNA were first isolated from B. mori (Hara and Yamakawa, 1995b; Chowdhury et al., 1995), the processing mechanism was not reported until fifteen years later (Rayaprolu et al., 2010). After removal of a signal peptide, M. sexta lebocin A precursor is predicted to be cut at the RXXR sites by intracellular, furin-like proteinases to form five different kinds of peptides (Fig. 9A). The second Arg, located at C-terminus of the four, is probably trimmed off by a carboxypeptidase to produce mature peptides LA1~4. LA1~3 were identified in M. sexta plasma, two of which were active against E. coli (Rayaprolu et al., 2010). Later, an extracellular processing mechanism was proposed for M. sexta lebocins B and C (Rao et al., 2012), but there was no direct evidence for the existence of such peptides in the larval plasma. In this work, we found lebocin D gene is located on Scaffold 00017, together with the other three genes in a cluster (Fig. 9B). Based on the identification of LA1~3 in plasma, we suggest that the LA3-corresponding region in lebocins B~D is further processed to LB3 (SVNEPSSQEHHERFV), LB4 (SFDSRSS), and LB5 (HHGGSHSTS SGSRDTGATHPGYNRRNS). It is unclear whether the Ser-, His-, and Gly-richness of these peptides may contribute to their weak antibacterial activity (Rao et al., 2012).

Fig. 9. M. sexta lebocins.

(A) A cluster of four lebocin genes (leb A~D) on Scaffold 00017. Red arrows represent gene sizes and orientations. (B) Aligned sequences. Following a secretion signal peptide (green), the mature proteins are converted to smaller peptides through proteolytic cleavage by intracellular convertases that recognizes RXXR. As demonstrated by the LC-MS/MS analysis of M. sexta hemolymph, the second Arg in the processed products of lebocin A (formerly lebocin) is removed by a specific carboxyl peptidase (Rayaprolu et al., 2010). While lebocin A becomes five peptides (LA4: SVETLASQEHL…ETLLRGT; LA5: SVELASQEVL) after processing, the LA3-corresponding region in lebocins B~D may be processed to produce three smaller peptides rich in Ser, His, or Gly. Pro residues in the sequences are shaded gray.

3.4. Other immune effectors: lysozymes, lysozyme-like proteins (LLPs), and transferrins

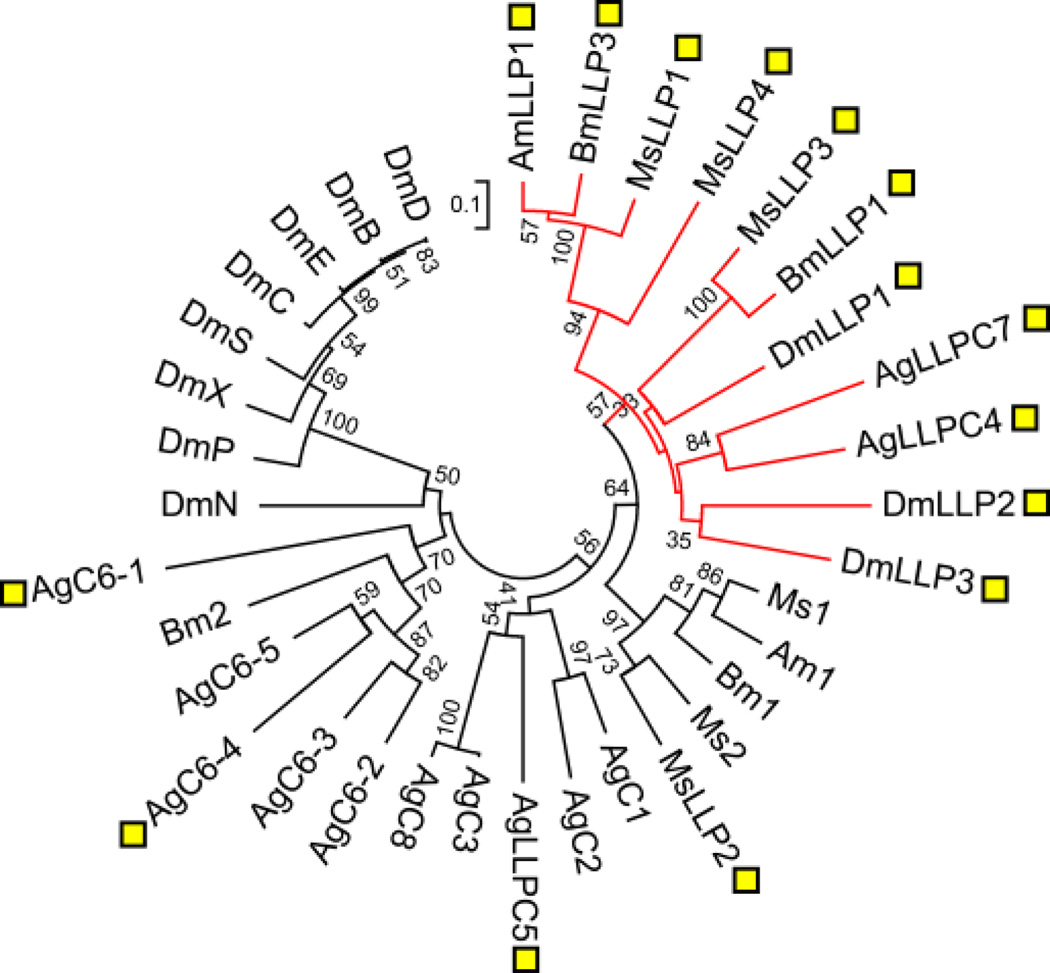

Lysozymes hydrolyze the β-1,4-glycosidic bond between N-acetylmuramic acid and N-acetyl-glucosamine of peptidoglycans. M. sexta lysozyme 1 (formerly lysozyme), whose expression is induced by immune challenge (Kanost et al., 1988; Mulnix and Dunn, 1994), somehow affects the prophenoloxidase activation (Rao et al., 2010). Its non-catalytic homolog LLP in B. mori has antibacterial activity, perhaps by interfering with membrane functions (Gandhe et al., 2007). In the M. sexta genome, we identified lysozymes 1, 2, and LLP1~4 genes: lysozymes 1, 2, and LLP2 on Scaffold 00095; LLP1 and LLP3 on Scaffold 00338; LLP4 on Scaffold 08332. The LLPs lack one or both of the catalytic residues (Glu and Asp). Lysozymes 1, 2, and LLP2 are descendants of a lysozyme gene orthologous to B. mori and A. mylitta lysozymes (Fig. 10). Likewise, M. sexta LLP1, A. mylitta LLP1 and B. mori LLP3 are orthologs, closer to M. sexta LLP4 than LLP3. Based on the phylogenetic analysis, divergence of lysozymes and most LLPs occurred early in the evolution of this group of genes. Mutation of the catalytic residues of lysozymes appears to have occurred multiple times in different lineages after the early separation of the lysozyme and LLP clades.

Fig. 10. Evolution of the lysozyme-related genes in M. sexta and other insects.

The mature protein sequences of lysozymes and LLPs from A. gambiae (Ag), A. mylitta (Am), B. mori (Bm), D. melanogaster (Dm), and M. sexta (Ms) are aligned to generate the neighbor-joining tree. A. gambiae C6, which contains five lysozyme domains, are labeled as AgC6-1~5. The sequences lacking one or both of the conserved Asp and Glu are indicated by yellow squares.

As key players of iron metabolism, transferrins bind iron at a high affinity (Garrick and Garrick, 2009). In insects, the transcription of transferrin genes can be dramatically induced upon immune challenge (Yun et al., 2009; Yoshiga et al., 1997). It has been hypothesized that increased concentration of transferrin in hemolymph may help to sequester iron, which is essential for bacteria, fungi and parasites. Insect transferrins consist of two homologous regions: the N-terminal lobe contains the conversed residues for iron binding while the C-terminal one no longer exerts this function (Lambert et al., 2005). Instead, immunological functions may have evolved in the C-lobe (Nichol et al., 2002). In the M. sexta genome, there are four genes encoding transferrins 1 (73,455 Da), 2 (76,738 Da), 3 (47,046 Da), and 4 (80,363 Da). Transferrin 1 is a hemolymph protein that binds ferric ion (Bartfeld and Law, 1990). Transferrins 2 and 4 are probably associated with cell membrane via C-terminal transmembrane region. Transferrin 3, 98.2% identical to transferrin 2 in the first 445 residues, has the intact N-terminal lobe and a 65-residue, truncated C-lobe. Lacking the transmembrane region, transferrin-3 may be a plasma protein that binds iron.

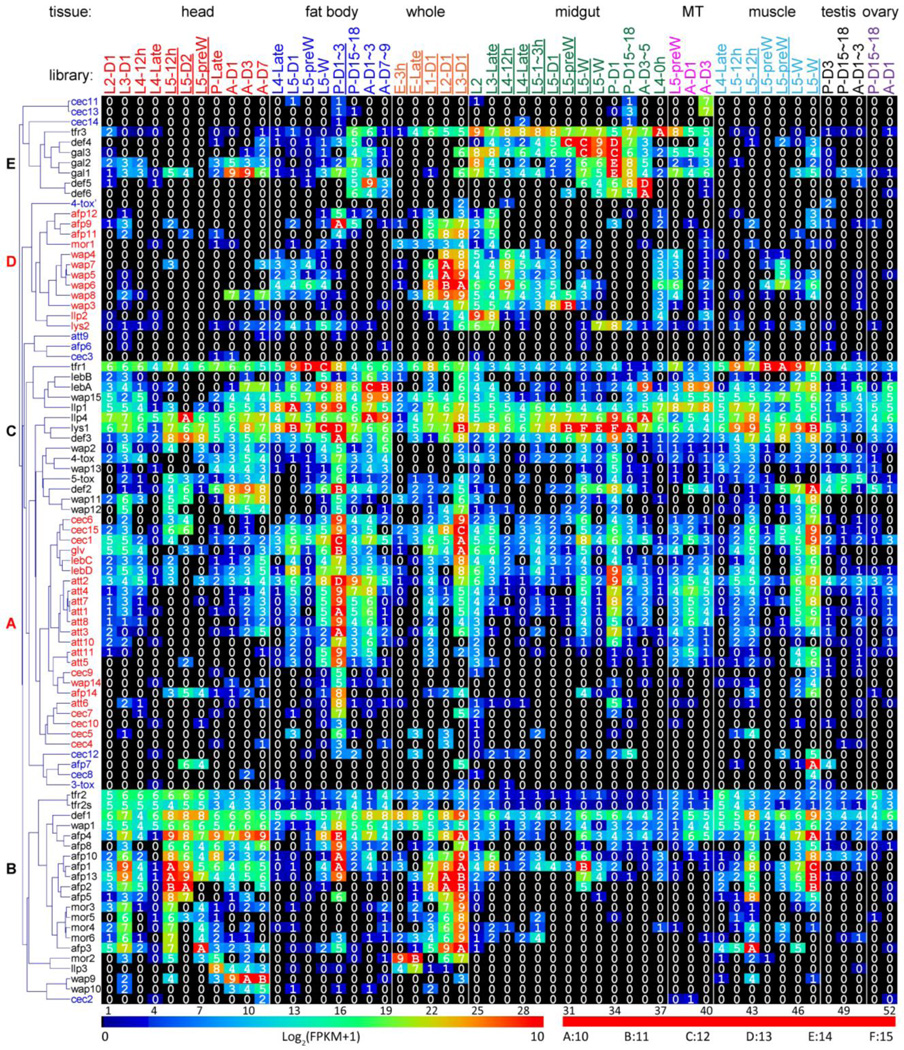

3.5. Expression profiles

To explore expression patterns of the putative AMPs, we examined their mRNA levels in 52 tissue samples from M. sexta at various developmental stages. Cluster analysis of the expression profiles resulted in six groups (Fig. 11). Group A (23 genes) includes attacins 1~8, 10, 11, cecropins 1, 4~7, 9, 10, 15, gloverin, lebocins C, D, diapausin 14 and WAP14, whose transcripts are most abundant in fat body of 5th instar feeding and wandering larvae, early pupae, and early adults. Their levels in midgut of wandering larvae and early pupae are also substantial. The mRNA levels of attacin 6, cecropins 4, 5, 7 and 10 are low-to-moderate in fat body of early pupae and lower in the other 51 tissue samples. The group B transcripts of defensin 1, diapausins 1~5, 8, 10, 13, LLP3, moricins 2~6, transferrins 2, 3, WAP1, 9 and 10 are abundant in the head extracts. While these genes are also transcribed in fat body of the wandering larvae, pupae and adults, possible fat body in the head total RNA samples does not adequately account for the stronger signals over the broad life stages. Interestingly, diapausins 9, 11, 12, lysozyme 2, LLP2, moricin 1, and WAP3~8 in group D are transcribed in midgut of feeding larvae, which is consistent with the detection of their mRNAs in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd instar whole larvae. Midgut expression of group E genes (gallerimycins 1~3, defensins 4~6, transferrin 4) in the feeding stages is greatly up-regulated to perhaps take the place of group D AMPs diminished in the wandering, pupal, and adult stages. Transcripts of the group C genes (defensins 2, 3, lebocins A, B, lysozyme 1, LLP1, 4, transferrin 1, 4-tox, 5-tox, WAP2, 11~13, 15) are present at high levels in many tissues. In contrast, attacin 9, cecropins 2, 3, 8, 11~14, diapausins 6, 8, 3-tox and 4-tox’ transcripts are low in most of the tissue samples.

Fig. 11. Transcript profiles of the M. sexta AMP genes in the fifty-two tissue samples.

The mRNA levels, as represented by log2(FPKM+1) values, are shown in the gradient heat map from blue (0) to red (≥10). The values of 0~0.49, 0.50~1.49, 1.50~2.49 … 8.50~9.49, 9.50~10.49 10.50~11.49, 11.50~12.49, 12.50~13.49, and 13.50~14.49 are labeled as 0, 1, 2 … 9, A, B, C, D and E, respectively. The 52 cDNA libraries (1 through 52) are constructed from the following tissues and stages: head [1. 2nd (instar) L (larvae), d1 (day 1); 2. 3rd L, d1; 3. 4th L, d0.5; 4. 4th L, late; 5. 5th L, d0.5; 6. 5th L, d2; 7. 5th L, pre-W (pre-wandering); 8. P (pupae), late; 9. A (adults), d1; 10. A, d3; 11. A, d7], fat body (12. 4th L, late; 13. 5th L, d1; 14. 5th L, pre-W; 15. 5th L, W; 16. P, d1–3; 17. P, d15–18; 18. A, d1–3; 19. A, d7–9), whole animals [20. E (embryos), 3h; 21. E, late; 22. 1st L; 23. 2nd L; 24. 3rd L), midgut (25. 2nd L; 26. 3rd L; 27. 4th L, 12h; 28. 4th L, late; 29. 5th L, 1–3h; 30. 5th L, 24h; 31. 5th L, pre-W; 32–33. 5th L, W; 34. P, d1; 35. P, d15–18; 36. A, d3–5; 37. 4th L, 0h), Malpighian tubules (MT) (38. 5th L, pre-W; 39. A, d1; 40. A, d3), muscle (41. 4th L, late; 42–43. 5th L, 12h; 44–45. 5th L, pre-W; 46–47. 5th L, W), testis (48. P, d3; 49. P, d15–18; 50. A, d1–3), and ovary (51. P, d15–18; 52. A, d1). Some libraries (underlined) are from single-end sequencing; the others are from paired-end sequencing. Note that some synonymous libraries exhibit different FPKMs due to method differences. Cluster analysis has revealed five distinct groups (A~E), as shown on the left. The group F genes (in blue font) are expressed at low levels [log2(FPKM+1): 0~4] in nearly all the 52 samples.

While cluster analyses categorize genes based on their relative levels in different samples to infer similar transcription regulation within each group, they tend to overlook the impact of actual (rather than relative) transcript levels, especially when one tries to compare them among family members (e.g. attaicn 2 vs. attacin 10). The mRNA levels of genes in this dataset vary dramatically. For instance, the FPKMs of lysozyme 1 mRNA in early embryo, wandering larval midgut and early pupal midgut are 3, 26,249 and 25,965, respectively. The FPKM values of attacin 9, cecropins 2, 3, 8, 11~14 transcripts were lower than 63 (average: 0.91) in all the 52 libraries. In contrast, attacin 2 and cecropin 1 mRNAs were moderate to high in over 2/3 of the 52 tissue samples, suggesting they are expressed constitutively to prevent infection. A comparison of mRNA levels for members in specific families suggests that attacin 2, cecropins 1, 15, defensin 1, WAP1 and WAP15 play more important roles than some of their homologs do (data not shown) in initial defense before gene expression has increased upon immune challenge.

3.6. Transcription up-regulation of AMP genes after immune challenge

Our studies on mRNA and polypeptide level changes (Zhang et al., 2011 and 2014; Gunaratna and Jiang, 2013) provided an overview of the immune system in response to a microbial challenge. In light of the genome sequence, we reanalyzed the results on AMPs (Table 1) in conjunction with a search for potential regulatory elements in the 1000 bp region upstream of each gene. We identified 13 R1 binding motifs, 261 GATA boxes, and 567 LPS responsive elements. The R1 binding site is required for Rel protein-mediated up-regulation of cecropin A1 transcription in D. melanogaster (Uvell and Engström, 2003). Nearly half of the fifteen cecropin genes (cecropins 2, 4, 5, 7, 11, 13, and 14) have an R1 binding site, as do diapausins 5, 7, attacin 11, lebocin B, LLP4, WAP5 and WAP9 (Table 1). Among the eight of these genes with transcript data available from immune challenge experiments, seven (attacin 11, lebocin B, cecropins 4, 5, 7, 8, WAP5) were induced 6 to 220-fold at mRNA levels and four (attacin 11, lebocin B, cecropins 5, 7) were elevated to >5 fold (p < 0.02) at protein levels (Zhang et al., 2014). However, when compared with the entire dataset, the presence or absence of an R1 element was not a good indicator of inducibility (data not shown). Neither were GATA and CATTW boxes, which are commonly found in the AMP genes.

Table 1.

Features of the M. sexta AMP genes, transcripts, and polypeptides

| name | length a (bp) |

κB b (2, 1, 0) |

GATA | R1 | CATTW | mRNA c | protein d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF/CF | IH/CH | I/C | p | ||||||

| diapausin 1 | 674 | 7, 0, 0 | 3 | 6 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 12.9 | 0.02 | |

| diapausin 2 | 7, 2, 0 | 3 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.96 | ||||

| diapausin 3 | 10, 2, 0 | 6 | 5 | ||||||

| diapausin 4 | 15, 2, 0 | 7 | 2 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 0.07 | ||

| diapausin 5 | 7, 2, 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |||||

| diapausin 6 | 471N | 10, 1, 0 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| diapausin 7 | 869 | 15, 0, 0 | 3 | 1 | 10 | ||||

| diapausin 8 | 13, 2, 0 | 3 | 2 | ||||||

| diapausin 9 | 133N | 11, 1, 0 | 6 | 8 | |||||

| diapausin 10 | 0 | 12.5 | 0.00 | ||||||

| diapausin 11 | 0 | 4.5 | nd | 8.9 | 0.00 | ||||

| diapausin 12 | 435 | 6, 0, 0 | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | nd | 11.6 | 0.01 | |

| diapausin 13 | 9, 4, 0 | 8 | 7 | 7.7 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0.02 | ||

| diapausin 14 | 511 | 4, 1, 0 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| attacin 1 | 5, 3, 1 | 9 | 10 | 83.6 | 16.6 | 91.6 | 0.12 | ||

| attacin 2 | 5, 1, 0 | 5 | 13 | 43.3 | 223.4 | 99.1 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 3 | 14, 2, 0 | 2 | 6 | 52.0 | 20.2 | 87.7 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 4 | 14, 6, 0 | 2 | 11 | 78.1 | 8.7 | 163.4 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 5 | 13, 4, 0 | 2 | 4 | 328.9 | nd | 101.4 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 6 | 16, 2, 2 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 24.9 | ||||

| attacin 7 | 21, 1, 1 | 3 | 3 | 108.1 | 41.6 | 66.3 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 8 | 11, 2, 1 | 7 | 10 | 108.1 | 41.6 | 150.9 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 9 | 8, 2, 0 | 3 | 8 | 102.6 | nd | 109.2 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 10 | 15, 1, 0 | 4 | 5 | 83.6 | 16.6 | 133.4 | 0.00 | ||

| attacin 11 | 15, 4, 1 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 219.8 | nd | 105.4 | 0.00 | |

| cecropin 1 | 11, 2, 0 | 5 | 10 | 24.5 | 34.4 | 2.3 | 0.00 | ||

| cecropin 2 | 9, 0, 0 | 4 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| cecropin 3 | 5, 0, 0 | 2 | 12 | 6.1 | 0.0 | ||||

| cecropin 4 | 9, 0, 0 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 18.4 | 0.0 | |||

| cecropin 5 | 6, 0, 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 78.0 | nd | 27.1 | 0.00 | |

| cecropin 6 | 6, 1, 0 | 6 | 6 | 17.3 | 11.9 | 18.6 | 0.00 | ||

| cecropin 7 | 8, 0, 0 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 18.0 | nd | 5.3 | 0.01 | |

| cecropin 8 | 16, 1, 0 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 6.0 | nd | 0.6 | 0.37 | |

| cecropin 9 | 10, 0, 0 | 6 | 16 | ||||||

| cecropin 10 | 11, 1, 0 | 6 | 14 | ||||||

| cecropin 11 | 8, 2, 0 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| cecropin 12 | 7, 2, 0 | 4 | 6 | ||||||

| cecropin 13 | 9, 2, 0 | 5 | 1 | 9 | |||||

| cecropin 14 | 10, 2, 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| cecropin 15 | 20 | 3.5 | 7.1 | ||||||

| defensin 1 | 5, 0, 0 | 2 | 10 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 0.6 | 0.55 | ||

| defensin 2 | 3, 0, 0 | 4 | 10 | ||||||

| defensin 3 | 9 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 0.20 | ||||

| defensin 4 | 9, 1, 0 | 3 | 11 | ||||||

| defensin 5 | 15, 2, 0 | 3 | 9 | ||||||

| defensin 6 | 10, 0, 0 | 4 | 9 | ||||||

| gallerimycin 1 | 10, 4, 0 | 1 | 6 | 127.0 | 8.3 | 21.8 | 0.00 | ||

| gallerimycin 2 | 9, 2, 0 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| gallerimycin 3 | 9, 2, 0 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| gloverin | 943 | 12, 0, 0 | 5 | 11 | 142.8 | 97.4 | 3.7 | 0.00 | |

| lebocin A | 14, 0, 0 | 2 | 13 | 370.9 | nd | 3.0 | 0.00 | ||

| lebocin B | 7, 0, 0 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 57.6 | 1.2 | 9.7 | 0.00 | |

| lebocin C | 9, 0, 0 | 5 | 10 | 142.3 | 7.1 | 33.4 | 0.00 | ||

| lebocin D | 14, 0, 0 | 4 | 9 | 451.5 | 0.9 | 37.2 | 0.00 | ||

| lysozyme 1 | 8, 2, 0 | 5 | 11 | 3.5 | 58.8 | 1.9 | 0.00 | ||

| lysozyme 2 | 14, 3, 0 | 2 | 6 | ||||||

| LLP1 | 11, 1, 0 | 2 | 11 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.24 | ||

| LLP2 | 10, 3, 0 | 4 | 7 | ||||||

| LLP3 | 10, 0, 0 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| LLP4 | 128 | 2 | |||||||

| moricin 1 | 7, 0, 0 | 2 | 8 | 118.3 | 103.3 | ||||

| moricin 2 | 16, 1, 0 | 2 | 8 | ||||||

| moricin 3 | 21, 2, 0 | 3 | 5 | ||||||

| moricin 4 | 15, 3, 0 | 2 | 9 | ||||||

| moricin 5 | 8, 1, 0 | 2 | 11 | ||||||

| moricin 6 | 836 | 4, 3, 0 | 1 | 11 | |||||

| transferrin 1 | 5, 0, 0 | 2 | 8 | 6.0 | nd | 1.1 | 0.69 | ||

| transferrin 2 | 6, 3, 0 | 4 | 7 | 17.9 | 8.7 | ||||

| transferrin 3 | 8, 2, 0 | 2 | 6 | 17.9 | 7.3 | ||||

| transferrin 4 | 8, 1, 0 | 6 | 5 | ||||||

| 5-tox | 5, 0, 0 | 3 | 11 | 42.3 | 84.8 | ||||

| WAP1 | 17, 2, 1 | 5 | 6 | 20.4 | 7.6 | 0.9 | 0.72 | ||

| WAP2 | 10, 0, 0 | 2 | 4 | 1.0 | 20.2 | 3.8 | 0.12 | ||

| WAP3 | 10, 0, 0 | 4 | 8 | 3.6 | nd | ||||

| WAP4 | 18, 3, 0 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| WAP5 | 16, 3, 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 7.7 | nd | |||

| WAP6 | 24, 4, 0 | 1 | 5 | 2.7 | nd | ||||

| WAP7 | 17, 2, 0 | 6 | |||||||

| WAP8 | 10, 0, 0 | 3 | 7 | 3.6 | nd | ||||

| WAP9 | 20, 0, 0 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 0.7 | nd | 1.1 | 0.88 | |

| WAP10 | 8, 0, 0 | 5 | 6 | ||||||

| WAP11 | 10, 3, 0 | 7 | 10 | 3.1 | 1.5 | ||||

| WAP12 | 15, 4, 0 | 6 | 8 | ||||||

| WAP13 | 14, 2, 0 | 3 | 9 | nd | 0.1 | ||||

| WAP14 | 14, 3, 0 | 1 | 9 | ||||||

| WAP15 | 16, 4, 0 | 4 | 7 | 0.7 | nd | ||||

length of the analyzed region before the longest transcript in Cufflink1.0: 1000 bp if unspecified. Length of the N stretch is indicated.

numbers of the κB motif (GGGRAYYYYY) with 2, 1, and 0 mismatch. R1 site, KKGNNTTTY; GATA box, WGATAR.

relative abundances of the mRNA in fat body (IF/CF) and hemocytes (IH/CH) (Zhang et al., 2011). nd, undetected.

I/C ratio from the peptidome data (Zhang et al., 2014). p-value from the Student’s t-test of normalized spectral counts.

We searched for putative NF-κB binding sites (GGGRAYYYYY) in 81 AMP genes that have >130 bp sequence upstream of their longest transcripts in the assembled scaffolds. This analysis revealed 6 genes containing NF-κB binding sites with 0, 1 and 2 mismatches (tier-1), 49 genes with 1 and 2 mismatches (tier-2), and 26 genes with 2 mismatches (tier-3) (Table 1). Among 40 of these genes showing increase in mRNA (≥6.0 fold) and/or protein (≥2.0 fold) levels after the immune challenge, 6 genes have κB elements with 0, 1 and 2 mismatches (tier-1), 17 genes in tier-2, and 17 in tier-3 are up-regulated. However, the presence of an NF-κB binding site is not a good indicator of inducibility, since 17 of the 40 genes lacking the perfect motif (tier-2) are up-regulated and so are the other 17 in tier-3. Nine other genes which contain multiple κB elements with 2 mismatches are not clearly induced (mRNA: 0.1~3.6 fold; protein: 0.6~1.1 fold) (Table 1). Transcriptional regulation of the eleven attacin genes is interesting: ten belong to group A (Fig. 11), five of the ten contain 1 or 2 perfect κB sites (tier-1), all eleven have 1 to 6 κB sites with mismatches (tier-2), and all 11 are induced upon immune challenge.

4. Discussion

Analysis of the M. sexta genome provides a deeper understanding of the extensive evolution of immune effector genes in this species. At one extreme, there is only one gloverin gene; at the other, 15 cecropin, 6 moricin, 15 WAP, 14 diapausin, and 11 attacin genes form large gene clusters at various locations in the genome (Fig. 1B, 2B, 5C, 6B, 8B). AMPs represent the fastest evolving protein group in insect immune systems (Table 2) (d'Alencon et al., 2013; Tanaka et al., 2008). The M. sexta genome contains 86 putative AMP genes, far more than those present in mammals (ca. 20) perhaps due to the evolution of adaptive immune mechanisms as effectors in vertebrates (Wiesner and Vilcinskas, 2010).

Table 2.

Numbers of AMP genes in M. sexta, B. mori, Danaus plexippus, and D. melanogaster*

| name | M. sexta | B. mori | D. plexippus | D. melanogaster |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| attacin | 11 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| cecropin | 15 | 13 | 5 | 4 |

| defensin | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| gallerimycin | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| X-tox | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| moricin | 6 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| gloverin | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| lysozyme-related | 6 | 4 | 6 | 11 |

| lebocin | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| diapausin | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| WAP | 15 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| transferrin | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| others | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Total | 86 | 42 | 28 | 38 |

The counts of B. mori and D. melanogaster AMP genes are mostly from Tanaka et al., 2008. BLASTP searches of GenBank with the M. sexta sequences yield the rest of the information.

In addition to the gene number, the dynamics of AMP evolution is also striking. The presence of gloverin, lebocins, and moricins in M. sexta and other lepidopteran species, but not beyond Lepidoptera, suggests these genes are relatively young. In contrast, defensins, found in plants, invertebrates and mammals, existed before the divergence of plant and animal kingdoms (Aerts et al., 2008). The lineage of defensins has attained extreme diversity in M. sexta. In one clade, defensins 1, 2, and gallerimycins 1~3 appear to have evolved from an ancient gene similar to drosomycins and defensins in dipteran insects (Fig. 3C). In the other clade, defensins 5 and 6 arose from a recent gene duplication while defensins 3 and 4 seem to have diverged much earlier. Exon duplication and alternative splicing gave rise to four X-tox proteins with 3, 4, 4, and 5 imperfect repeats of a Cys-stabilized αβ fold (Fig. 4). Molecular modeling suggests that these defensin-like proteins mostly adopt a conserved fold with various modifications (Fig. 3B). While there is no good evidence to support convergent evolution, we cannot rule out that possibility at present.

The fourteen M. sexta diapausins are results of a major family expansion, with ten encoded by a cluster of single exon genes (Fig. 5C). Based on our BLAST search of the EST database at NCBI, a similar expansion yielded multiple diapausins in Spodoptera exigua (data not shown). On the other hand, we did not identify any diapausin gene in the genomes of B. mori, A. gambiae, D. melanogaster and T. castaneum. These ancient genes, present in at least nine orders of insects (Fig. 5B), were apparently lost in these lineages. The low sequence similarity between diapausins and defensin homologs in insects makes it unclear whether they are related. At the structural level, G. atrocyanea diapausin has a disulfide-stabilized αβ fold (Kouno et al., 2007), but its disulfide linkage pattern and topology differ from those of the defensins. We consider that multiple AMPs with similar structures (e.g. 14 diapausins and 15 cecropins) may provide advantages to the host. The presence of multiple cecropins, moricins and attacins with slightly different structures could help to provide protection against a broad array of pathogens. Or, perhaps some AMPs may form oligomers that have activity distinct from those of the individual peptides. The presence of AMP gene families makes it possible for tissues such as fat body to more rapidly produce large amounts of peptides in response to infection than would be possible with a single gene, which may be a selective force in the evolution of large AMP gene families. The mixture of immune effectors in hemolymph likely acts in concert to kill invading microorganisms. For instance, lysozymes hydrolyze cell wall peptidoglycans of bacteria, providing access for cecropins to the cell membranes, where they act to form pores resulting in bacterial death. The members of an AMP family may vary in their activity, with some existing as evolutionary relics that are no longer an essential component of the immune system.

It is common in the evolution of AMPs and other proteins that once a protein fold with a useful biochemical action evolves, the core structure attains additions functions through gene duplication and divergence (Zhu and Gao, 2013). Therefore, it is highly desirable to determine or at least predict the basic structures of AMPs to better understand their functions and modes of action. Molecular models of the moricin and Cys-stabilized proteins (Fig. 2C, 3B, 6C) support the known homolog structures (Dai et al., 2008; Landon et al., 1997; Kouno et al., 2007). Template-independent modeling also reveals potential structural features of gloverin and attacins (Fig. 7C, 8D). The model structure for attacin 1, as a tripartite, β-barrel provides important insights into the structure, mechanism, and evolution of insect attacins. In M. sexta attacins 1~11, exon 1 encodes a signal peptide, a short pro-region (only in attacins 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10) and region I; exons 2 and 3 encode regions II and III, respectively. In the model, each region forms a 4-strand antiparallel β-sheet as a folding unit, and three units form a barrel. Most insect attacins contain three units, A. gambiae attacin and D. melanogaster diptericin have one, Musca domestica attacin 4 has two, and Aedes aegypti attacin has four. These units may form a patch on the surface of Gram-negative bacteria, allowing the turns, which link the neighboring β-strands, to insert into the cell membrane. Gloverin may utilize a similar mechanism to kill Gram-negative bacteria.

Posttranslational modifications are conserved mechanisms for AMP maturation. Removing secretion peptide by signal peptidase, trimming off (Xaa-Pro)1~2 by amino dipeptidase, and C-terminal amidation by action of lyase on a terminal Gly are commonly employed to generate cecropins and moricins. Cleavage next to RXXR by convertases and subsequent deletion of the C-terminal Arg residue(s) by carboxypeptidase are used to remove the pro-region, which can be active AMP (e.g. drosocin). In light of this, it would be interesting to test if pro-regions of the M. sexta attacins, defensin 4, and gloverin are active against bacteria. Processing at RXXR is used to the extreme in the cases of lebocins A~D, where 4 to 5 peptides are produced from each precursor polypeptide. Although weak antibacterial activity was detected in some of the peptides (Rayaprolu et al., 2010; Rao et al., 2012), the strict conservation of RXXR sites suggests that the resulting peptides may have immune functions, and perhaps are active against microorganisms that have not yet been tested.

Of course, the rapid evolution of AMPs has also occurred in noncoding parts of their genes (Table 1) and the available genome makes possible a start toward understanding how regulatory elements contribute to transcriptional control of large numbers of genes in an immune response in M. sexta. The transcription of AMP genes is a well-orchestrated process involving DNA-binding proteins and their cognate sequences, typically located in the upstream promoter region. We analyzed the AMP expression in 52 tissue samples and documented their mRNA levels (Fig. 11) in naïve insects. The temporospatial patterns suggest co-regulation of groups of AMP genes, and we further examined the immune inducibility of these genes in relation to putative responsive elements in their promoter regions. The results were surprising that only six of the forty up-regulated genes (attacins 1, 6~8, 11, WAP1) contain a perfect κB motif (GGGRAYYYYY). While 23 of the 40 have one or more of the motif with one mismatch (tier-1 and 2), the other 17 contain the κB site with 2 mismatches (tier 3). Apparently, this loosely defined consensus may not apply well to the M. sexta AMP genes. Co-evolution of the immune responsive elements and DNA-binding domains of the Rel-family transcription factors in this lineage of lepidopteran insects may have resulted in divergence of the optimal κB motif. Most of our knowledge on regulation of AMP gene expression in insects comes from research in Drosophila. Experimental studies of the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of AMPs in Lepidoptera are needed to gain an understanding of the diversity of immune mechanism in these insects. The identification here of the catalog of AMP genes with potential function in immune responses of M. sexta provides a resource for future work to characterize their regulation and their biochemical roles in defense against microbial infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants GM58634 (to H. Jiang) and GM041247 (to M. Kanost), and a DARPA grant (to G. Blissard). This work was approved for publication by the Director of Oklahoma Agricultural Experimental Station, and supported in part under project OKLO2450 (to H. Jiang). Computation for this project was performed at OSU High Performance Computing Center at Oklahoma State University supported in part through the National Science Foundation grant OCI–1126330.

Abbreviations

- AMP

antimicrobial protein/peptide

- WAP

whey acidic protein

- LLP

lysozyme-like protein

- C

control

- I

induced

- F

fat body

- H

hemocyte

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- ORF

open reading frame

References

- Aerts AM, François IE, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. The mode of antifungal action of plant, insect and human defensins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2069–2079. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axen A, Carlsson A, Engstrom A, Bennich H. Gloverin, an antibacterial protein from the immune hemolymph of Hyalophora pupae. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:614–619. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfeld NS, Law JH. Isolation and molecular cloning of transferrin from the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. sequence similarity to the vertebrate transferrins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21684–21691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulet P, Stocklin R, Menin L. Antimicrobial peptides from invertebrates to vertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:169–184. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jiang H. Integrated modeling of protein-coding genes in the Manduca sexta genome using RNA-Seq data from the biochemical model insect. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.01.007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Taniai K, Hara S, Kadono-Okuda K, Kato Y, Yamamoto M, Xu J, Choi SK, Debnath NC, Choi HK, Miyanoshita A, Sugiyama M, Asaoka A, Yamakawa M. cDNA cloning and gene expression of lebocin, a novel member of antibacterial peptides from the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214:271–278. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophides GK, Zdobnov E, Barillas-Mury C, Birney E, Blandin S, Blass C, Brey PT, Collins FH, Danielli A, Dimopoulos G, Hetru C, Hoa NT, Hoffmann JA, Kanzok SM, Letunic I, Levashina EA, Loukeris TG, Lycett G, Meister S, Michel K, Moita LF, Muller HM, Osta MA, Paskewitz SM, Reichhart JM, Rzhetsky A, Troxler L, Vernick KD, Vlachou D, Volz J, von Mering C, Xu J, Zheng L, Bork P, Kafatos FC. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002;298:159–165. doi: 10.1126/science.1077136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Alencon E, Bierne N, Girard PA, Magdelenat G, Gimenez S, Seninet I, Escoubas JM. Evolutionary history of x-tox genes in three lepidopteran species: origin, evolution of primary and secondary structure and alternative splicing, generating a repertoire of immune-related proteins. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;43:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Rayaprolu S, Gong Y, Huang R, Prakash O, Jiang H. Solution structure, antibacterial activity, and expression profile of Manduca sexta moricin. J Peptide Sci. 2008;14:855–863. doi: 10.1002/psc.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson L, Russell V, Dunn PE. A family of bacteria-regulated, cecropin D-like peptides from Manduca sexta. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:19424–19429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JD, Aronstein K, Chen YP, Hetru C, Imler JL, Jiang H, Kanost M, Thompson GJ, Zou Z, Hultmark D. Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis mellifera. Insect Mol Biol. 2006;15:645–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehlbaum P, Bulet P, Michaut L, Lagueux M, Broekaert WF, Hetru C, Hoffmann JA. Insect immunity: septic injury of Drosophila induces the synthesis of a potent antifungal peptide with sequence homology to plant antifungal peptides. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:33159–33163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhe AS, Janardhan G, Nagaraju J. Immune upregulation of novel antibacterial proteins from silkmoths (Lepidoptera) that resemble lysozymes but lack muramidase activity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick MD, Garrick LM. Cellular iron transport. Biochim Biophy Acta. 2009;1790:309–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutter MG, Fendrich G, Huber R, Bode W. The 2.5 a X-ray crystal-structure of the acid-stable proteinase-inhibitor from human mucous secretions analyzed in its complex with bovine α-chymotrypsin. EMBO J. 1988;7:345–351. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02819.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunaratna R, Jiang H. A comprehensive analysis of the Manduca sexta immunotranscriptome. Dev Comp Immunol. 2013;39:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara S, Yamakawa M. Moricin, a novel type of antibacterial peptide isolated from the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Biol Chem. 1995a;270:29923–29927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.50.29923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara S, Yamakawa M. A novel antibacterial peptide family isolated from the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biochem J. 1995b;310(2):651–656. doi: 10.1042/bj3100651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedengren M, Borge K, Hultmark D. Expression and evolution of the Drosophila attacin/diptericin gene family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;279:574–581. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultmark D, Engstrom A, Andersson K, Steiner H, Bennich H, Boman HG. Insect immunity-attacins, a family of antibacterial proteins from Hyalophora cecropia. EMBO J. 1983;2:571–576. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultmark D, Steiner H, Rasmuson T, Boman HG. Insect immunity: purification and properties of three inducible bactericidal proteins from hemolymph of immunized pupae of Hyalophora cecropia. Eur J Biochem. 1980;106:7–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb05991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving P, Troxler L, Heuer TS, Belvin M, Kopczynski C, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Hetru C. A genome-wide analysis of immune responses in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15119–15124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261573998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Vilcinskas A, Kanost MR. Immunity in lepidopteran insects. In. “Invertebrate Immunity”. In: Söderhäll K, editor. Adv Exp Med Biol. Vol. 708. 2010. pp. 181–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Dai W, Dunn PE. Peptidoglycan fragments elicit antibacterial protein synthesis in larvae of Manduca sexta. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1988;8:147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Jiang H, Yu XQ. Innate immune responses of a lepidopteran insect, Manduca sexta. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanost MR, Nardi JB. Innate immune responses of Manduca sexta. In: Goldsmith MR, Marec F, editors. Molecular Biology and Genetics of Lepidoptera. CRC Press; 2010. pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kouno T, Mizuguchi M, Tanaka H, Yang P, Mori Y, Shinoda H, Unoki K, Aizawa T, Demura M, Suzuki K, Kawano K. The structure of a novel insect peptide explains its Ca2+ channel blocking and antifungal activities. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13733–13741. doi: 10.1021/bi701319t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert LA, Perri H, Meehan TJ. Evolution of duplications in the transferrin family of proteins. Comp Biochem Physiol. Pt B, Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;140:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberty M, Ades S, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Brookhart G, Bushey D, Hoffmann JA, Bulet P. Insect immunity. Isolation from the lepidopteran Heliothis virescens of a novel insect defensin with potent antifungal activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9320–9326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landon C, Sodano P, Hetru C, Hoffmann J, Ptak M. Solution structure of drosomycin, the first inducible antifungal protein from insects. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1878–1884. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Ann Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Boman A, Sun CX, Andersson M, Jörnvall H, Mutt V, Boman HG. Antibacterial peptides from pig intestine: isolation of a mammalian cecropin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9159–9162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh JA, Gooley AA, Karuso PH, Beattie AJ, Jardine DR, Veal DA. A gloverin-like antibacterial protein is synthesized in Helicoverpa armigera following bacterial challenge. Dev Comp Immunol. 1998;22:387–399. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(98)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama K, Natori S. Purification of three antibacterial proteins from the culture medium of NIH-Sape-4, an embryonic cell line of Sarcophaga peregrina. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17112–17116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulnix AB, Dunn PE. Structure and induction of a lysozyme gene from the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;24:271–281. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nappi AJ, Christensen BM. Melanogenesis and associated cytotoxic reactions: applications to insect innate immunity. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;35:443–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol H, Law JH, Winzerling JJ. Iron metabolism in insects. Ann Rev Entomol. 2002;47:535–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan S, Simpson KJ, Shaw DC, Nicholas KR. The whey acidic protein family: a new signature motif and three-dimensional structure by comparative modeling. J Mol Graph Model. 1999;17:106–113. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(99)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao XJ, Ling EJ, Yu XQ. The role of lysozyme in the prophenoloxidase activation system of Manduca sexta: an in vitro approach. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao XJ, Xu XX, Yu XQ. Functional analysis of two lebocin-related proteins from Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;42:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayaprolu S, Wang Y, Kanost MR, Hartson S, Jiang H. Functional analysis of four processing products from multiple precursors encoded by a lebocin-related gene from Manduca sexta. Dev Comp Immunol. 2010;34:638–647. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KV, Yedery RD, Aranha C. Antimicrobial peptides: premises and promises. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:536–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Kucukural A, Zhang Y. I-TASSER: a unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat Protocols. 2010;5:725–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmann B, Seitz V, Vilcinskas A, Podsiadlowski L. Cloning and expression of gallerimycin, an antifungal peptide expressed in immune response of greater wax moth larvae, Galleria mellonella. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2003;53:125–133. doi: 10.1002/arch.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HB, Chou KC. Signal-3L: a 3-layer approach for predicting signal peptides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith VJ, Fernandes JM, Kemp GD, Hauton C. Crustins: enigmatic WAP domain-containing antibacterial proteins from crustaceans. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008;32:758–772. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Hultmark D, Engstrom A, Bennich H, Boman HG. Sequence and specificity of two antibacterial proteins involved in insect immunity. Nature. 1981;292:246–248. doi: 10.1038/292246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strand MR. The insect cellular immune response. Insect Sci. 2008;15:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Ishibashi J, Fujita K, Nakajima Y, Sagisaka A, Tomimoto K, Suzuki N, Yoshiyama M, Kaneko Y, Iwasaki T, Sunagawa T, Yamaji K, Asaoka A, Mita K, Yamakawa M. A genome-wide analysis of genes and gene families involved in innate immunity of Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;38:1087–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Sato K, Saito Y, Yamashita T, Agoh M, Okunishi J, Tachikawa E, Suzuki K. Insect diapause-specific peptide from the leaf beetle has consensus with a putative iridovirus peptide. Peptides. 2003;24:1327–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2003.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Suzuki K. Expression profiling of a diapause-specific peptide (DSP) of the leaf beetle Gastrophysa atrocyanea and silencing of DSP by double-strand RNA. J Insect Physiol. 2005;51:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvell H, Engström Y. Functional characterization of a novel promoter element required for an innate immune response in Drosophila. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8272–8281. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8272-8281.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiga T, Hernandez VP, Fallon AM, Law JH. Mosquito transferrin, an acute-phase protein that is up-regulated upon infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12337–12342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun EY, Lee JK, Kwon OY, Hwang JS, Kim I, Kang SW, Lee WJ, Ding JL, You KH, Goo TW. Bombyx mori transferrin: genomic structure, expression and antimicrobial activity of recombinant protein. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009;33:1064–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizioli J, Bulet P, Charlet M, Lowenberger C, Blass C, Muller HM, Dimopoulos G, Hoffmann J, Kafatos FC, Richman A. Cloning and analysis of a cecropin gene from the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:75–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner J, Vilcinskas A. Antimicrobial peptides: the ancient arm of the human immune system. Virulence. 2010;1:440–464. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.5.12983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- X, et al. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Yi HY, Chowdhury M, Huang YD, Yu XQ. Insect antimicrobial peptides and their applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:5807–5822. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5792-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SG, Gunaratna RT, Zhang XF, Najar F, Wang Y, Roe B, Jiang HB. Pyrosequencing-based expression profiling and identification of differentially regulated genes from Manduca sexta, a lepidopteran model insect. Insect Biochem Molec. 2011;41:733–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SG, Cao XL, He Y, Hartson S, Jiang H. Semi-quantitative analysis of changes in the plasma peptidome of Manduca sexta larvae and their correlation with the transcriptome variations upon immune challenge. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;47:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Lu Z, Strand M, Jiang H. Antiviral, antiparasitic, and cytotoxic effects of 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI), a reactive compound generated by phenoloxidase during insect immune response. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41:645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Gao B. Evolutionary origin of β-defensins. Dev Comp Immunol. 2013;39:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Johnson TJ, Myers AA, Kanost MR. Identification by subtractive suppression hybridization of bacteria-induced genes expressed in Manduca sexta fat body. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:541–559. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zou Z, Evans J, Lu Z, Zhao P, Williams M, Sumathipala N, Hetru C, Hultmark D, Jiang H. Comparative genome analysis of the Tribolium immune system. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R177. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.