Summary

Over 50 years ago, the discovery of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) set a new field of science in motion - the field of poly(ADP-ribosyl) transferases (PARPs) and ADP-ribosylation. The field is still flourishing today. The diversity of biological processes now known to require PARPs and ADP-ribosylation was practically unimaginable even two decades ago. From an initial focus on DNA damage detection and repair in response to genotoxic stresses, the field has expanded to include the regulation of chromatin structure, gene expression, and RNA processing in a wide range of biological systems, including reproduction, development, aging, stem cells, inflammation, metabolism, and cancer. This special focus issue of Molecular Cell includes a collection of three Reviews, three Perspectives, and a SnapShot, which together summarize the current state of the field and suggest where it may be headed.

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation and MARylation, respectively) are post-translational modifications of proteins catalyzed by members of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) family of enzymes. Studies over the past two decades have lead to a tremendous expansion of our knowledge of the molecular actions and biological functions of (1) PAR and MAR, (2) the proteins that bind them, and (3) the enzymes that catalyze their addition to, or cleavage from, target proteins. Such a diversity of targets, partners, functions, and biological endpoints was practically unimaginable even two decades ago. In this Perspective, I provide a brief history and overview of the field, as well as an introduction to the current areas of research that are discussed in the other PARP- and ADP-ribosylation-related pieces in this issue. At the end of this piece, I have included interviews with two scientists who made ground-breaking discoveries at the dawn of the field: Pierre Chambon, who discovered PAR in the early 1960s (Chambon et al., 1966; Chambon et al., 1963) and Masanao Miwa, who discovered PAR glycohydrolase (PARG), an enzyme that degrades PAR, in the early 1970s (Miwa and Sugimura, 1971; Miwa et al., 1974).

Whence You Came, PARPs and ADP-ribosylation?

The years between 1959–1961 saw a flurry of research activity leading to the discovery of DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Hurwitz, 2005). It was against this backdrop that Pierre Chambon and colleagues, working in the early 1960s, made their initial discoveries that unwittingly launched a new field, which would eventually encompass PARPs and ADP-ribosylation. While studying the synthesis of RNA by RNA polymerase, Chambon and colleagues incubated chicken liver nuclear extracts with α32P-ATP and found that the addition of NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide), a precursor of NAD+ (Figure 1), caused a large increase in 32P incorporation, even in the absence of the other NTPs. They tentatively identified the reaction product as polyA (Chambon et al., 1963). However, upon further analysis, they soon realized that the reaction product was not ‘classical’ polyA, since it contained both the phosphate and ribose moieties from the NMN. This quickly led to the identification of the chemical structure of the product as a polymer of ADP-ribose by Chambon et al., as well as the laboratories of Takashi Sugimura and Osamu Hayaishi in Japan (Chambon et al., 1966; Fujimura et al., 1967a; Fujimura et al., 1967b; Hasegawa et al., 1967; Nishizuka et al., 1967; Reeder et al., 1967; Sugimura et al., 1967). The rest, as they say, is history.

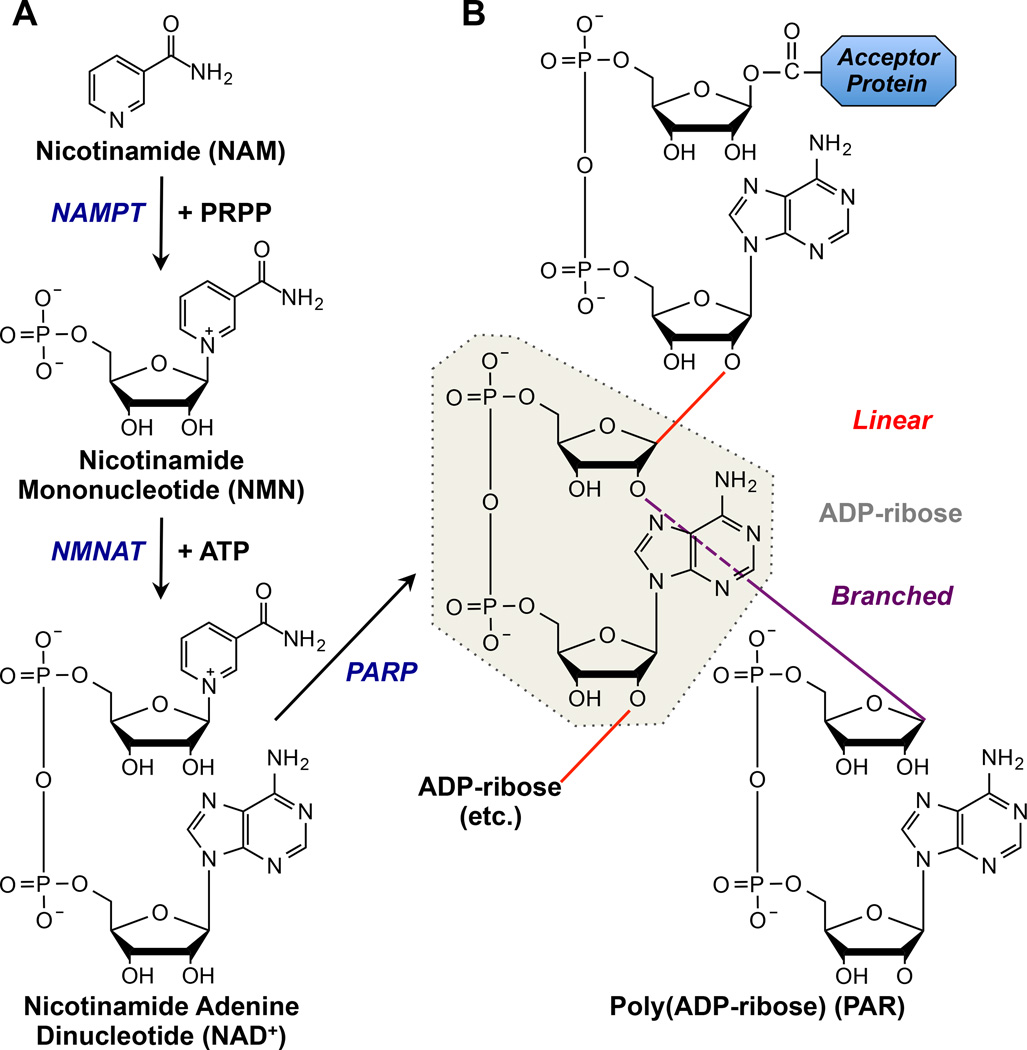

Figure 1. Biosynthesis of NAD+ and PAR.

Pathway for the biosynthesis of NAD+ and poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) from precursors, showing the chemical structures of the precursors, intermediates, and products, as well as the enzymes catalyzing each reaction (listed in blue text).

(A) Biosynthesis of NAD+ in a pathway leading from nicotinamide (NAM), through nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), to NAD+. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) catalyzes the synthesis of NMN from NAM and 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate (PRPP). Nicotinamide adenylyltransferase-1, -2, or -3 (NMNAT-1, -2, or -3) catalyzes the synthesis of NAD+ from NMN and ATP.

(B) Biosynthesis of PAR from NAD+ on a target protein, catalyzed by PARPs. PAR can be elongated by the addition of ADP-ribose units (grey highlight) in a linear (red) or branched (purple) manner.

All in the Family

Today, we recognize a family of at least 17 PARP-related enzymes, all containing the ‘PARP signature’ motif (Ame et al., 2004; Hottiger, 2015), which have recently been organized under a new ‘ADP-ribosyltransferase, diphtheria toxin-like’ (ARTD) nomenclature (Hottiger, 2015; Hottiger et al., 2010). Some of the family members (e.g., PARP-1 and PARP-2) catalyze the synthesis of PAR on target proteins using NAD+ as a donor of ADP-ribose units (Figure 1). However, other family members - the mono(ADP-ribosyl) transferases (e.g., PARP-3 and PARP-16), which comprise most of the family - use NAD+ to catalyze the covalent attachment of MAR on target proteins. Finally, three remaining family members (e.g., PARP-13) lack any apparent catalytic activity (Hottiger, 2015).

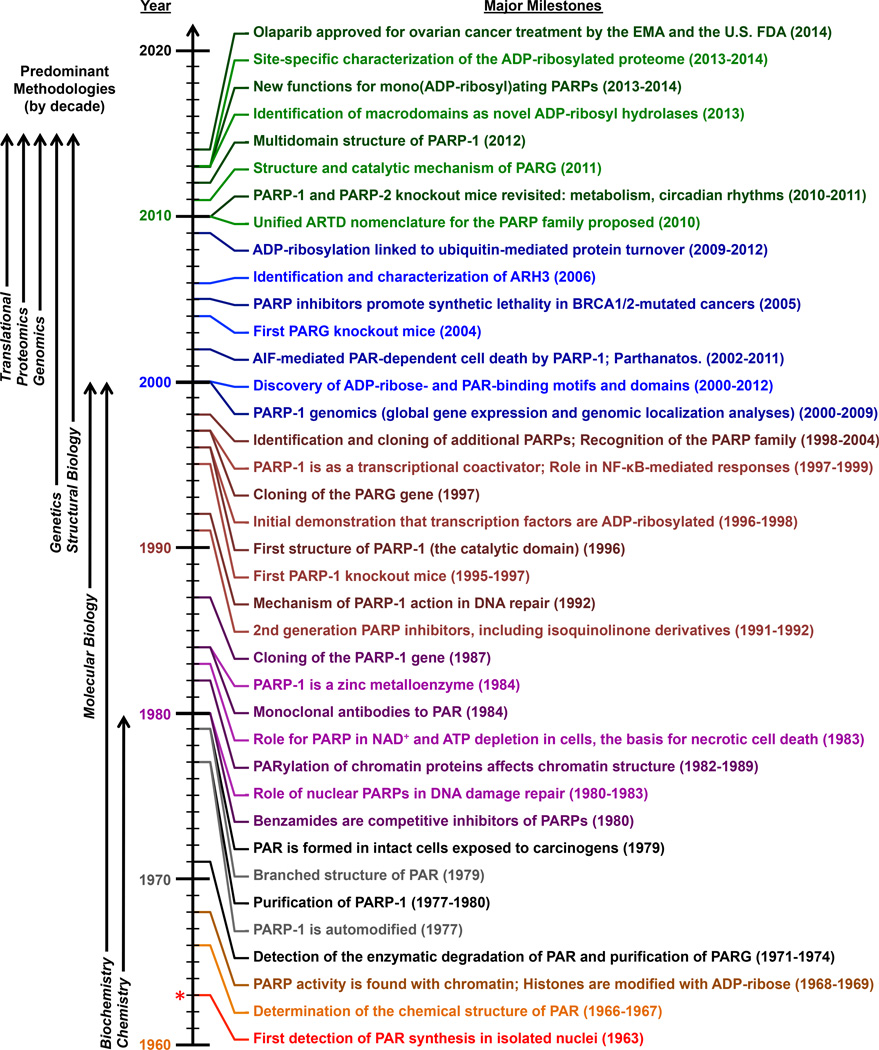

Like many fields that have focused on the activity of a family of enzymes, the PARP and ADP-ribosylation field has progressed from biochemistry and molecular biology to genomics and physiology (Figure 2; see also the expanded timeline included in the Supplementary Materials). Most of the early studies of PARPs and ADP-ribosylation were carried out with PARP-1, the most ubiquitous and abundant PARP family member (D'Amours et al., 1999). PARP-1 is a ‘DNA-dependent’ nuclear PARP-1 whose catalytic activity is potently stimulated by damaged DNA (D'Amours et al., 1999). Over the past five decades, we have seen our understanding of the molecular and biological functions of PARP-1 evolve from roles in DNA damage detection and repair (Bouchard et al., 2003), to roles in the regulation of chromatin structure and transcription (Kraus and Lis, 2003; Krishnakumar and Kraus, 2010), and now, more recently, to key roles in cellular stress responses and physiological processes (Bai and Canto, 2012; Luo and Kraus, 2012). In addition, PARP-1 enzymatic activity has become a key target for therapeutic interventions using PARP inhibitors (Tangutoori et al., 2015).

Figure 2. Timeline of major milestones in the PARP and ADP-ribosylation field.

Major discoveries, observations, and technical advances in the PARP and ADP-ribosylation field are color-coded by decade, starting from the initial discovery of PAR by Chambon et al. in 1963 and extending to the present. The predominant methodological approaches used in each decade are shown to the left.

Our understanding of the other members of PARP family is more limited, but progress is slowly being made, from a role of PARP-5b (Tankyrase-1) function at telomeres in the nucleus (Smith et al., 1998), to a role for PARP-16 in the unfolded protein response at the endoplasmic reticulum (Jwa and Chang, 2012). In spite of recent heroic ‘survey’ studies that have helped to define the subcellular localization, catalytic activity, and non-nuclear functions of other PARP family members (Vyas et al., 2013; Vyas et al., 2014), many questions remain. A field that once seemed small and highly focused in the days of biochemistry and molecular biology now seems enormous as we begin to consider the vast number of possible roles for this family of enzymes in physiology and disease.

Recent Advances, Future Prospects

The field of PARPs and ADP-ribosylation has experienced a sea change over the past two decades. The focus of the field has shifted dramatically during this time, from DNA repair under stress conditions to regulation of gene expression, RNA, and cytoplasmic functions under normal physiological conditions. Also during this time, the field identified and characterized the broader set of enzymes that degrade or remove PAR and MAR, as well as proteins that bind PAR and MAR. In this regard, the field has adopted the nomenclature used by the histone modification field describing ‘writers’ (i.e., PARPs), ‘erasers’ (i.e., PAR glycohydrolases, such as PARG and ARH3, and ADP-ribosyl hydrolases, such as MacroD1 and TARG1), and ‘readers’ (i.e., proteins that contain PAR-binding motifs, macrodomains, PAR-binding zinc fingers, WWE domains) (see the SnapShot by Hottiger in this issue; (Hottiger, 2015)). In the following sections, I briefly introduce the five recent conceptual and technical advances that are the subject of the accompanying pieces in this issue.

Structural biology of writers, erasers, and readers

In 1996, Ruf et al. published the first crystal structure of a domain of PARP-1, the catalytic domain (Ruf et al., 1996). Since then, additional structures have helped elucidate how the various domains of PARP-1 interact to establish DNA-dependent catalysis (Ali et al., 2012; Langelier et al., 2012). In addition, studies in the past ten years have provided structural insights for (1) PARG (Slade et al., 2011), (2) macrodomains with ADP-ribosyl hydrolase activity (Rosenthal et al., 2013; Jankevicius et al., 2013; Sharifi et al. 2013), and (3) macrodomains and WWE domains with ADP-ribose and/or PAR-binding activities (Karras et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2012). As described in the Review by Barkauskaite et al. in this issue (Barkauskaite et al., 2015), these studies have helped to reveal the PARP enzymatic mechanism and activation, as well as regulation of ADP- ribosylation signals by readers and erasers.

Proteomics and the study of ADP-ribosylation

For a field concerned with site-specific post-translational modifications, revelations about which amino acids are targeted by PARP proteins and development of methods for reliably detecting those modifications were slow to come. Early biochemical assays suggested that ADP-ribosylation occurs on glutamate residues (Burzio et al., 1979; Ogata et al., 1980a; Ogata et al., 1980b; Riquelme et al., 1979) and aspartate residues (Suzuki et al., 1986), while later studies indicated that ADP-ribosylation occurs on lysine residues (Altmeyer et al., 2009; Haenni et al., 2008; Messner et al., 2010) (n.b., Glu, Asp, and Lys are the three amino acids most commonly thought to be targeted).

Although methods for mass spectrometry-based proteomic analyses have improved dramatically over the past 20 years, they were not, until recently, able to identify ADP-ribosylated peptides due to the labile nature of the ADP-ribose moiety during mass spectrometry (Daniels et al., 2015). To circumvent this issue, some labs identified proteins ‘pulled-down’ by PAR using mass spectrometry, but these studies were unable to determine definitively on a global basis if the interaction of the proteins with PAR was covalent or non-covalent (Gagne et al., 2008; Gagne et al., 2012; Isabelle et al., 2012; Jungmichel et al., 2013). In other words, these studies were unable to unambiguously distinguish the ‘ADP-ribose interactome’ (i.e., noncovalent) from the ‘ADP-ribosyl-proteome’ (i.e., covalent). Recent studies using improved mass spectrometry techniques have overcome this limitation, allowing site-specific characterization of the ADP-ribosylated proteome (Daniels et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2013). In the Perspective by Daniels et al. in this issue (Daniels et al., 2015), the authors review the newest proteomic approaches (mass spectrometry-based and others) for studying site-specific ADP-ribosylation of proteins, discuss the pro and cons of these methods, and ways in which the data generated by these methods should be interpreted.

RNA regulation by PARP family members

An emerging area of PARP and PAR molecular biology is related to the regulation of RNA. In this regard, PARP-1 acts to silence rDNA chromatin, regulate ribosomal biogenesis, and promote the processing, translation, and stability of mRNAs (Ryu et al., 2015). For example, PARP-1 (1) interacts physically and functionally with noncoding pRNA to retain silent rDNA chromatin in the nucleolus (Guetg et al., 2012) and (2) promotes ribosome biogenesis by PARylation of several nucleolar proteins (Boamah et al., 2012). Furthermore, PAR is required for the assembly of cytoplasmic stress granules, which contain PAR, PARPs, and PARG, as well as RNA-binding proteins that regulate the translation and stability of mRNAs in response to stress (Leung et al., 2011). The identification of roles for PARPs and PAR in RNA regulation brings the total of major biochemical and molecular functions of PARPs and PAR to three: (i.e., DNA repair, gene expression, and RNA regulation). In the Review by Bock et al. in this issue (Bock et al., 2015), the authors review and discuss the latest findings about how PARP-dependent regulation of RNAs, including the modulation of RNA processing, translation, and decay, affects numerous processes in the cell.

The new biology of PARP family members

Of all the potential areas of knowledge within the PARP and ADP-ribosylation field, the one we know the least about is the physiological functions of PARP family members. The initial phenotype of the original PARP-1 knockout mouse was disappointing, since there were no obvious defects when the mice were grown without deliberate stressors (Wang et al., 1995). Later studies, however, did find some DNA repair defects in the PARP-1 knockout mice (de Murcia et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1997). Recent breakthroughs have come from the realization that the biological roles of a stress-sensing protein, such as PARP-1, should be explored in response to stress, not the pathogen-free, fixed-light, low fat diet environments to which typical laboratory mice are exposed (Luo and Kraus, 2012). This realization led to some groundbreaking stress-response studies in mice demonstrating clear roles for PARP-1 and PARP-2 in metabolism (Bai et al., 2011a; Bai et al., 2011b; Devalaraja-Narashimha and Padanilam, 2010), and for PARP-1 in circadian rhythms (Asher et al., 2010). Studies of PARG function in knockout mice have also revealed important insights, such as the catabolism of PAR is essential for life (Cortes et al., 2004; Koh et al., 2004). Interestingly, the knockout of PARP-1 or PARG in a variety of species results in similar outcomes, suggesting that PARP-1 or PARG do not necessarily act antagonistically to each other, but rather may act in similar biological pathways (Kim et al., 2005). Thus, synthesis and degradation of PAR may be two sides of the same coin, with each one alone unable to maintain a normal phenotype. In the Review by Bai in this issue (Bai, 2015), the author discusses the biological roles that PARPs play in cancer biology, oxidative stress, and inflammatory and metabolic diseases.

Molecular actions and clinical promise of PARP inhibitors

Given their key roles in numerous physiological and pathological states, the potential benefit of targeting the enzymatic activity of PARPs for therapeutic purposes is very high (Tangutoori et al., 2015). In no area has this been more evident than in cancers. Two groundbreaking studies in 2005 showed that PARP inhibitors act to promote synthetic lethality in BRCA1/2-mutated cancers (Bryant et al., 2005; Farmer et al., 2005), although further studies have shown that PARP inhibitors may be effective in killing cells with intact BRCA1/2 (Frizzell and Kraus, 2009; Tangutoori et al., 2015), possibly through non-DNA repair pathways. In 2014, Olaparib (AstraZeneca's Lynparza) was the first PARP inhibitor approved for cancer treatment by both the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), targeting advanced ovarian cancers associated with defective BRCA1/2 genes. PARP inhibitors have also shown promise for the treatment of inflammation, heart disease, and stroke. In the Perspective by Knudsen et al. in this issue (Knudsen et al., 2015), the authors review the mechanisms by which PARP inhibitors elicit clinical responses, as well as strategies for translating preclinical studies of PARP function into therapeutic advances.

Conclusions

The past two decades have brought a host of new discoveries that have fundamentally changed our understanding of the molecular and biological functions of PAR, PARPs, and associated proteins (i.e., erasers and readers). The impact of these discoveries is beginning to be felt in the realm of human health and medicine, where PARP inhibitors are now being used in the clinic. The field of PARPs and ADP-ribosylation may be mature, but young scientists who have entered the field are bringing new ideas and fresh perspectives that are pushing the field in new directions. The field’s past was certainly interesting and full of important discoveries, but the future looks even brighter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank (1) Pierre Chambon and Masanao Miwa for agreeing to be interviewed for this piece and for providing candid answers, (2) colleagues in the field, including Ivan Ahel, Péter Bai, Paul Chang, Michael Hottiger, Anthony Leung, John Pascal, Guy Poirier, and Zhao-Qi Wang, for providing helpful suggestions about the timeline, and (3) Keun Woo Ryu and Shino Murakami for assistance with the figures. The PARP-related research in the author’s lab is supported by a grant from the NIH/NIDDK.

Appendix

Interviews with Pierre Chambon and Masanao Miwa: Perspectives on the Beginning of the PARP and ADP-ribosylation Field

While preparing for this special focus issue on PARPs and ADP-ribosylation for Molecular Cell, I interviewed Pierre Chambon and Masanao Miwa, two scientists who were present at the beginning of the field and made significant contributions to it. Their responses to my questions provide some interesting insights into beginning of the field.

An interview with Pierre Chambon, who made the initial discovery of PAR (1963–1966)

Dr. Chambon is on the faculty at the Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cellular Biology (IGBMC), Strasbourg, France, which he founded in 1994.

WLK: The studies described in your 1963 BBRC paper, in which you described the NMN- and DNA-dependent production of a new polyadenylic acid, were aimed at understanding the activity of RNA polymerase. What was the state of the field at the time? What motivated you to do those experiments? Were you surprised at the outcome?

PC: In the mid-1950s, I was a medical student at the Faculté de Médecine de Strasbourg and was spending half of my time working at the Institute of Chimie Biologique, which was led by Paul Mandel, who had a great interest in the synthesis of RNA. My first work was to determine the distribution of nucleoside mono-, di-, and triphosphates for each of the four bases in spleen and bone marrow. In the medical thesis that I defended at the end of the fifties (1958), I concluded that RNA could very well be synthesized in vivo starting from nucleoside triphosphates, rather than from nucleoside diphosphates polymerized by the E. coli polynucleotide phosphorylase, as proposed by Marianne Manago in the laboratory of Severo Ochoa (1958). Fortunately for me, the lab of Sam Weiss (Chicago) reported in 1959 the synthesis of RNA in vitro by incubating rat liver nuclei with all four labeled nucleoside triphosphates, a result which was rapidly confirmed in several laboratories (those of S. Ochoa, P. Berg and J. Hurwitz) in which soluble extracts from bacteria could synthesize RNA in the presence of DNA from nucleoside triphosphates (NTP).

Upon his return to our laboratory, my colleague Jacques Weill, who had spent a year in Ochoa laboratory, brought back the bacterial system, with the idea to repeat the synthesis of RNA from NTP in extracts from liver cells. Unfortunately, we rapidly realized that very little of the liver RNA polymerase was soluble, most of it being very tightly bound to chromatin and impossible to solubilize, even in 2 M salt: the so-called “aggregate enzyme.” This led us to initiate a series of studies in which we incubated “aggregate enzyme” preparations of various tissues from animals subjected to different treatments in order to determine how the overall transcription catalyzed by transcriptionally “engaged” RNA polymerase molecules was affected by a given treatment. The approach we were using at that time later became known as “run-on nuclear transcription.” Importantly, it was believed that the RNA synthesized in vitro by the aggregate enzyme corresponded to “engaged” RNA polymerase molecules and, therefore, was similar to the rapidly labeled RNA extracted from lysed cells.

At the end of 1961, a medical student, Michel Revel (who later moved to the Weizmann Institute, where he made a bright career) was working on a project with Paul Mandel, namely the effect of nicotinamide administration on the compensatory hypertrophy of one kidney upon resection of the other one. As previous work from Revel and Mandel had shown that addition of NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide) to whole kidney nuclei incubated in vitro stimulated 14C-adenine incorporation into an RNA fraction, we incubated liver “aggregate enzyme” preparations with labeled α32P-ATP, with or without the other NTPs. We observed an enormous increase in 32P incorporation, and tentatively identified the product of the reaction as polyA (see our BBRC paper, 1963).

However, upon further analysis of the products of the reaction, we soon realized that it was not a “classical” polyA, since both the phosphate and ribose of NMN were present in the reaction product. Together with my student, Janine Doly, we worked very hard during the next two years to purify the product of the reaction in amounts that allowed us to establish its structure on firm grounds, with the help of a Parisian colleague, F. Petek. Unexpectedly, we found that it was a polymer of adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADPR): PAR, synthesized from NAD+ (DPN at that time), which was itself synthesized from ATP and NMN by the “aggregate” fraction of nuclear extracts. As a matter of fact, the enzyme was not an enzyme catalyzing the formation of polyA from ATP, but a transglucosidase catalyzing the polymerization of NAD+ molecules through the formation of a linkage between ribose molecules, with the simultaneous removal of the nicotinamide moiety. We reached this conclusion in the spring of 1966 and our manuscript was published in BBRC in the fall of 1966. You can imagine how relieved we were to be the first to publish that what we initially had tentatively identified as polyA was in fact PAR, synthesized not by a polyA polymerase, but by a yet unknown nuclear transglucosidase, which was later named PAR polymerase (PARP)!

As soon as we realized in 1962 that the product of the reaction was not an RNA, it was clear to us that the “aggregate” DNA-dependent RNA polymerase was not involved in the synthesis of our “polyadenylic” product. Rather we thought that it could be the product of a novel polyA polymerase (see our 1963 and 1966 BBRC papers). As a matter of fact, during the same period, we were still working on the aggregate RNA polymerase, attempting to solubilize it in order to purify it and measuring its activity under various pathophysiological conditions, which as a matter of fact was at the origin of our interest in the molecular mechanisms underlying the action of steroid hormones at the transcriptional level. We found and published that the activity of the liver aggregate RNA polymerase was indeed increased upon estradiol administration to a male chicken!

You asked me whether I was surprised at the outcome. Yes, because I had essentially no idea about the possible functions of PAR.

WLK: In the decade after your initial discovery, there were a number of follow-up studies published, including one from you in 1966 published in BBRC, which characterized PAR in more detail. Were there any controversies in those early days about the existence of PAR, its chemical structure, its function, or the synthesizing enzyme?

PC: In fact, my student Janine Doly, together with another student, worked until 1998 on the purification of PAR synthesized in vitro and found that it was closely associated with histones. She also partially purified the PARP to the extent that its in vitro synthesis became dependent on the addition of DNA or histones, or both. In 1968, she defended her thesis, which contains these results that we never published, for several reasons. First, because 1968 was the time of the last (!) Revolution in France, and I was deeply involved in it, trying to convince French scientists that the organization of French biomedical research should be based on those in other countries, particularly that of USA (you may know that I spent 1967 in Stanford, working in the lab of Arthur Kornberg where, among other things, I learned how research should be organized). Second, I had no idea whatsoever what the physiological functions of PAR and PARP could be, whereas that of RNA polymerase was undoubtedly most important. Third, I had a small group of five students in 1968, and we had preliminary evidence (from the inhibitory effect of α-amanitin) that there could be multiple RNA polymerases in animal cells and strong indications that we were on the edge of solubilizing in large amounts the “aggregate” RNA polymerase and to purify it, we decided to focus our efforts there. I therefore abruptly stopped all work on PAR and PARP, thinking that I could resume our studies, if one day there was genetic evidence that PAR and PARP were physiologically meaningful, which I was not convinced of in 1968, wondering whether it could be an in vitro artifact!

To finish with your question, there has not been, to my best knowledge, any controversies concerning what we published in 1966.

WLK: Although not a major focus of your research program during your career, you continued to study aspects of PARP biology with Gilbert de Murcia, especially using mouse genetic models. What motivated those experiments and how did they relate to the state of the field at the time? How important do you think mouse models have been to our understanding of PARP function?

PC: As discussed above, I stopped working on PAR, in particular because I had no idea of its biological importance. Also, to be motivated, I had to work on problems whose importance was clearly evident at the time. In other words, I needed genetic evidence supporting the relevance of PAR and PARP for life. This was clearly not the case at that time. But, I also stated at the time that whenever a genetic approach would become possible, I certainly would study the role of PARP. Accordingly, we collaborated with the team of Josiane Ménissier and Gilbert de Murcia to make the first knockouts of PARP-1 (1997) and PARP-1/PARP-2 (2003).

I think that mouse models are of paramount importance to reveal the physiological and pathophysiological functions of genes and their products. Cell/tissue-specific mutations at specific times during the life of the mouse should be done systematically to reveal and/or confirm functions, which can only be guessed from in vitro or pharmacological studies. More mouse models must be done.

WLK: Looking back over the past 50+ years of PARylation and PARPs, which have seen the field move from DNA repair to transcription, and physiology to cancer, where do you think the field might go next?

PC: I was not anticipating that PARylation would be of such importance. That being said, I am still amazed that it appears to be as important as it is, at least as suggested by the in vitro studies. It may be informative to look at simple model organisms (zebrafish?) and to mouse or human stem cells during their differentiation (2D and 3D). Nonetheless, I hate to make predictions and nothing surprises me, because the logic of life is not predictable!

WLK: Does the field now resemble in any way what you thought it might when you were making your initial discoveries in 1960s?

PC: What always impresses me is how long it takes for a research field to progress. People always say that scientific knowledge is progressing faster and faster. I do not believe that this is true. In the present case, it started in 1960, almost 60 years ago (much longer than the active life of a normal scientist!). Obviously, the field has progressed, but we should not forget that it is thanks to technological advancements, many of which are not related to the activity of biologists. Obviously, the field does not resemble in any way today what I thought it might become when I was making my initial discoveries in the 1960s. At that time, I did not even dream of a genetic revolution (and many other discoveries in Physics and Chemistry), which have made possible all of the present advances in our understanding of life.

An interview with Masanao Miwa, who made the initial discovery of PARG (1971– 1974)

Dr. Miwa is currently on the faculty at the Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology, Japan

WLK: Many of the early discoveries regarding PAR were from Japanese scientists. Why was there an interest by these scientists in PAR? Who were the leaders in the Japanese PARP community and what were their thoughts as the initial discoveries about PAR coalesced?

MM: The leaders in the Japanese PARP community in the early days of the field were Dr. Takashi Sugimura at National Cancer Center Research Institute at Tokyo and Dr. Osamu Hayaishi at University of Kyoto. I heard the following story from Dr. Takashi Sugimura, who told me that he was reading a chapter in the Annual Review of Biochemistry, which reported the findings by Chambon, Weill, and Mandel that polyA synthesis in chicken liver nuclei was enhanced 1,000-fold by the addition of nicotinamide mononucleotide to the incubation mixture. Dr. Sugimura was very much impressed by the observation that the synthesis of a high molecular weight compound like polyA was greatly enhanced by a small molecule like nicotinamide mononucleotide. Dr. Sugimura tried to confirm the results reported by Chambon et al. (1963), but was unable to since the product was alkaline resistant, which would not be expected for an RNA molecule. This finding was reported at a small meeting in Japan. Dr. Hayaishi was also interested in the report from Chambon et al. because he was an expert in tryptophan metabolism and NAD+ synthesis. The labs of both Dr. Sugimura and Dr. Hayaishi eventually came to the same conclusion that the product was not polyA, but PAR.

WLK: In the decade after the initial discovery of PAR, there were a number of follow-up studies published that characterized PAR in more detail. Were there any controversies in those early days about the existence of PAR, its chemical structure, its function, or the synthesizing enzyme?

MM: There were some questions on the natural occurrence of PAR, since it was present at low amounts in cells. Kidwell and Mage in 1976, and Sakura et al. in 1977, showed the presence of PAR in HeLa cells and in calf thymus, respectively, using a specific antibody against PAR. In addition, I thought that PAR should be present in vivo, since the antibody against PAR was present in sera of the patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Furthermore, the function of PAR was not clear at that time, but Burzio and Koide published an interesting paper in 1970 on the effect of ADP-ribosylation on DNA synthesis, but it was not clear whether it represented DNA replication or DNA repair.

WLK: Do you have any specific recollections about how the field studying PAR and PARPs came together, solidified, and established a unique identify, which was evident by the mid- 1970s?

MM: In Japan, there was a funding system supported by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, where leaders in Japanese scientific research could secure grants for cancer research to organize a team, including young scientists, and support their research. They met at least once a year to report their achievements. My research program was well supported by this program. There was strong competition between members of National Cancer Center Research Institute and Kyoto University. This competition was a driving force for PARP research in Japan at the time. During the meetings, I learned many things about PAR and PARPs, which were coming together as a field and obtaining a unique identity.

In addition, Princess Takamatsu, whose mother had passed away due to cancer, supported cancer research in Japan by holding at least two international symposia on cancer, where Japanese scientists could meet many distinguished scientists from abroad. Princess Takamatsu supported not only travel and lodging, but also invited the speakers from abroad and from Japan to her residence to have a big farewell party. It was an unforgettable experience for PARP researchers around the world and it helped to foster many friendships. I was quite happy to have an opportunity to be acquainted with various PARP leaders around the world from the first international meeting on PARP and ADP-ribosylation.

WLK: In the early 1970s, you made some of the initial discoveries characterizing the degradation of PAR by PARG. What motivated you to do those experiments? Were you surprised at the outcome?

MM: When I joined in the field, it was already established that there were PAR degrading enzymes, like snake venom phosphodiesterase and rat liver phosphodiesterase. However, when PAR is partially degraded, it has a structure that cannot be re-elongated. Therefore, I thought that there might be another enzyme to reverse the actions of PARP - an enzyme that could split the ribose-ribose bond. I was quite surprised and pleased when my hypothesis was finally proven.

WLK: Looking back over the past 50+ years of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and PARPs, which have seen the field move from DNA repair to transcription, and physiology to cancer, what do you think are some of the most surprising discoveries?

MM: I suppose there have been a number of discoveries that have surprised me. For example, I was surprised by the finding from Matsushima-Hibiya et al. (2003) that the butterfly toxin, pierisin, can ADP-ribosylate DNA. Another surprise for me was the developmental and neurological phenotypes of the PARG deficient fruit flies that we made, reported in Hanai et al. (2004). They can eclose at 29°C, but not at 25°C. In addition, they cannot fly and die within two weeks. After this, Ted Dawson’s group observed early embryonic lethality of PARG knockout in mice. Finally, I was surprised by the findings of one of my graduate students, Masayuki Kanai, who observed the localization of PARP-1 to the centrosome, as reported in Kanai et al. (2003). Knockout of the PARP-1 gene or treatment of cells with PARP inhibitors causes amplification of the centrosomes, which is frequently found in cancer tissues. These findings suggest and important relationship between disregulation of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and carcinogenesis.

WLK: You have been working in the PARP field your entire career. Does the field now resemble in any way what you thought it might when you were making your initial discoveries in 1970s?

MM: I think the field is expanding more extensively and rapidly these days than I ever could have imagined. When I found PARG, I felt there was not much left to do in this field.

WLK: In which directions do you think the field may go over the next two decades? What do you think are the major unanswered questions that still need to be addressed?

MM: I think the next great discovery will be made in the role poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in chromatin structure, studied in three dimensions. Furthermore, methods for the detection and quantification PAR in cells or tissues under physiological conditions without DNA damage are needed. Finally, I think that the continued development of highly specific inhibitors of PARG and PARP family members for the treatment of cancer and other diseases should be emphasized.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali AA, Timinszky G, Arribas-Bosacoma R, Kozlowski M, Hassa PO, Hassler M, Ladurner AG, Pearl LH, Oliver AW. The zinc-finger domains of PARP1 cooperate to recognize DNA strand breaks. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2012;19:685–692. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmeyer M, Messner S, Hassa PO, Fey M, Hottiger MO. Molecular mechanism of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1 and identification of lysine residues as ADP-ribose acceptor sites. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:3723–3738. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ame JC, Spenlehauer C, de Murcia G. The PARP superfamily. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2004;26:882–893. doi: 10.1002/bies.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher G, Reinke H, Altmeyer M, Gutierrez-Arcelus M, Hottiger MO, Schibler U. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 participates in the phase entrainment of circadian clocks to feeding. Cell. 2010;142:943–953. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P. Biology of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases – the factotums of cell maintenance. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.034. (this Issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C. The role of PARP-1 and PARP-2 enzymes in metabolic regulation and disease. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C, Brunyanszki A, Huber A, Szanto M, Cen Y, Yamamoto H, Houten SM, Kiss B, Oudart H, et al. PARP-2 regulates SIRT1 expression and whole-body energy expenditure. Cell metabolism. 2011a;13:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P, Canto C, Oudart H, Brunyanszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, Yamamoto H, Huber A, Kiss B, Houtkooper RH, et al. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell metabolism. 2011b;13:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkauskaite E, Jankevicius G, Ahel I. Structures and mechanisms of enzymes employed in the synthesis and degradation of PARP-dependent protein ADP-ribosylation. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.007. (this issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah EK, Kotova E, Garabedian M, Jarnik M, Tulin AV. Poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) regulates ribosomal biogenesis in Drosophila nucleoli. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock FJ, Todorova TT, Chang P. RNA regulation by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.037. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard VJ, Rouleau M, Poirier GG. PARP-1, a determinant of cell survival in response to DNA damage. Experimental hematology. 2003;31:446–454. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burzio LO, Riquelme PT, Koide SS. ADP ribosylation of rat liver nucleosomal core histones. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1979;254:3029–3037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P, Weill JD, Doly J, Strosser MT, Mandel P. On the formation of a novel adenylic compound by enzymatic extracts of liver nuclei. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1966;25:638–643. [Google Scholar]

- Chambon P, Weill JD, Mandel P. Nicotinamide mononucleotide activation of new DNA-dependent polyadenylic acid synthesizing nuclear enzyme. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1963;11:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(63)90024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes U, Tong WM, Coyle DL, Meyer-Ficca ML, Meyer RG, Petrilli V, Herceg Z, Jacobson EL, Jacobson MK, Wang ZQ. Depletion of the 110-kilodalton isoform of poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase increases sensitivity to genotoxic and endotoxic stress in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7163–7178. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7163-7178.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amours D, Desnoyers S, D'Silva I, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. The Biochemical journal. 1999;342(Pt 2):249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CM, Ong S-E, Leung AK. The promise of proteomics in the study of ADP-ribosylation. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.012. (this issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CM, Ong SE, Leung AK. Phosphoproteomic approach to characterize protein mono- and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation sites from cells. Journal of proteome research. 2014;13:3510–3522. doi: 10.1021/pr401032q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Murcia JM, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Ricoul M, Dutrillaux B, Mark M, Oliver FJ, Masson M, Dierich A, LeMeur M, et al. Requirement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in recovery from DNA damage in mice and in cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:7303–7307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalaraja-Narashimha K, Padanilam BJ. PARP1 deficiency exacerbates diet-induced obesity in mice. The Journal of endocrinology. 2010;205:243–252. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frizzell KM, Kraus WL. PARP inhibitors and the treatment of breast cancer: beyond BRCA1/2? Breast cancer research : BCR. 2009;11:111. doi: 10.1186/bcr2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Hasegawa S, Shimizu Y, Sugimura T. Polymerization of the adenosine 5'-diphosphate-ribose moiety of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide by nuclear enzyme. I. Enzymatic reactions. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1967a;145:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(67)90043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Hasegawa S, Sugimura R. Nicotinamide mononucleotide-dependent incorporation of ATP into acid-insoluble material in rat liver nuclei preparation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1967b;134:496–499. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JP, Isabelle M, Lo KS, Bourassa S, Hendzel MJ, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Poirier GG. Proteome-wide identification of poly(ADP-ribose) binding proteins and poly(ADP-ribose)-associated protein complexes. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:6959–6976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagne JP, Pic E, Isabelle M, Krietsch J, Ethier C, Paquet E, Kelly I, Boutin M, Moon KM, Foster LJ, et al. Quantitative proteomics profiling of the poly(ADP-ribose)-related response to genotoxic stress. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:7788–7805. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guetg C, Scheifele F, Rosenthal F, Hottiger MO, Santoro R. Inheritance of silent rDNA chromatin is mediated by PARP1 via noncoding RNA. Molecular cell. 2012;45:790–800. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenni SS, Hassa PO, Altmeyer M, Fey M, Imhof R, Hottiger MO. Identification of lysines 36 and 37 of PARP-2 as targets for acetylation and auto-ADP-ribosylation. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2008;40:2274–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S, Fujimura S, Shimizu Y, Sugimura R. The polymerization of adenosine 5'-diphosphate-ribose moiety of NAD by nuclear enzyme. II. Properties of the reaction product. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1967;149:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottiger MO. SnapShot: Intracellular ADP-ribosylation. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.001. (this issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottiger MO, Hassa PO, Luscher B, Schuler H, Koch-Nolte F. Toward a unified nomenclature for mammalian ADP-ribosyltransferases. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2010;35:208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz J. The discovery of RNA polymerase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:42477–42485. doi: 10.1074/jbc.X500006200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isabelle M, Gagne JP, Gallouzi IE, Poirier GG. Quantitative proteomics and dynamic imaging reveal that G3BP-mediated stress granule assembly is poly(ADP-ribose)-dependent following exposure to MNNG-induced DNA alkylation. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:4555–4566. doi: 10.1242/jcs.106963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmichel S, Rosenthal F, Altmeyer M, Lukas J, Hottiger MO, Nielsen ML. Proteome-wide identification of poly(ADP-Ribosyl)ation targets in different genotoxic stress responses. Molecular cell. 2013;52:272–285. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jwa M, Chang P. PARP16 is a tail-anchored endoplasmic reticulum protein required for the PERK- and IRE1alpha-mediated unfolded protein response. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:1223–1230. doi: 10.1038/ncb2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karras GI, Kustatscher G, Buhecha HR, Allen MD, Pugieux C, Sait F, Bycroft M, Ladurner AG. The macro domain is an ADP-ribose binding module. The EMBO journal. 2005;24:1911–1920. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MY, Zhang T, Kraus WL. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP-1: 'PAR-laying' NAD+ into a nuclear signal. Genes & development. 2005;19:1951–1967. doi: 10.1101/gad.1331805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen KE, de Bono JS, Rubin MA, Feng FY. Chromatin to clinic: The molecular rationale for PARP1 inhibitor function. Molecular cell. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.016. (this issue). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh DW, Lawler AM, Poitras MF, Sasaki M, Wattler S, Nehls MC, Stoger T, Poirier GG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Failure to degrade poly(ADP-ribose) causes increased sensitivity to cytotoxicity and early embryonic lethality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:17699–17704. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406182101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus WL, Lis JT. PARP goes transcription. Cell. 2003;113:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnakumar R, Kraus WL. The PARP side of the nucleus: molecular actions, physiological outcomes, and clinical targets. Molecular cell. 2010;39:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langelier MF, Planck JL, Roy S, Pascal JM. Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science. 2012;336:728–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1216338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung AK, Vyas S, Rood JE, Bhutkar A, Sharp PA, Chang P. Poly(ADP-ribose) regulates stress responses and microRNA activity in the cytoplasm. Molecular cell. 2011;42:489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Kraus WL. On PAR with PARP: cellular stress signaling through poly(ADP-ribose) and PARP-1. Genes & development. 2012;26:417–432. doi: 10.1101/gad.183509.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner S, Altmeyer M, Zhao H, Pozivil A, Roschitzki B, Gehrig P, Rutishauser D, Huang D, Caflisch A, Hottiger MO. PARP1 ADP-ribosylates lysine residues of the core histone tails. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:6350–6362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M, Sugimura T. Splitting of the ribose-ribose linkage of poly(adenosine diphosphate-robose) by a calf thymus extract. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1971;246:6362–6364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M, Tanaka M, Matsushima T, Sugimura T. Purification and properties of glycohydrolase from calf thymus splitting ribose-ribose linkages of poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) The Journal of biological chemistry. 1974;249:3475–3482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y, Ueda K, Nakazawa K, Hayaishi O. Studies on the polymer of adenosine diphosphate ribose. I. Enzymic formation from nicotinamide adenine dinuclotide in mammalian nuclei. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1967;242:3164–3171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata N, Ueda K, Hayaishi O. ADP-ribosylation of histone H2B. Identification of glutamic acid residue 2 as the modification site. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980a;255:7610–7615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata N, Ueda K, Kagamiyama H, Hayaishi O. ADP-ribosylation of histone H1. Identification of glutamic acid residues 2, 14, and the COOH-terminal lysine residue as modification sites. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1980b;255:7616–7620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder RH, Ueda K, Honjo T, Nishizuka Y, Hayaishi O. Studies on the polymer of adenosine diphosphate ribose. II. Characterization of the polymer. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1967;242:3172–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme PT, Burzio LO, Koide SS. ADP ribosylation of rat liver lysine-rich histone in vitro. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1979;254:3018–3028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf A, Mennissier de Murcia J, de Murcia G, Schulz GE. Structure of the catalytic fragment of poly(AD-ribose) polymerase from chicken. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:7481–7485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu KW, Kim DS, Kraus WL. New facets in the regulation of gene expression by ADP-ribosylation and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases. Chemical reviews. 2015;115:2453–2481. doi: 10.1021/cr5004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade D, Dunstan MS, Barkauskaite E, Weston R, Lafite P, Dixon N, Ahel M, Leys D, Ahel I. The structure and catalytic mechanism of a poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase. Nature. 2011;477:616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature10404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S, Giriat I, Schmitt A, de Lange T. Tankyrase, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase at human telomeres. Science. 1998;282:1484–1487. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura T, Fujimura S, Hasegawa S, Kawamura Y. Polymerization of the adenosine 5'-diphosphate ribose moiety of NAD by rat liver nuclear enzyme. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1967;138:438–441. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(67)90507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Quesada P, Farina B, Leone E. In vitro poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of seminal ribonuclease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1986;261:6048–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangutoori S, Baldwin P, Sridhar S. PARP inhibitors: A new era of targeted therapy. Maturitas. 2015;81:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S, Chesarone-Cataldo M, Todorova T, Huang YH, Chang P. A systematic analysis of the PARP protein family identifies new functions critical for cell physiology. Nature communications. 2013;4:2240. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S, Matic I, Uchima L, Rood J, Zaja R, Hay RT, Ahel I, Chang P. Family-wide analysis of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activity. Nature communications. 2014;5:4426. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Michaud GA, Cheng Z, Zhang Y, Hinds TR, Fan E, Cong F, Xu W. Recognition of the iso-ADP-ribose moiety in poly(ADP-ribose) by WWE domains suggests a general mechanism for poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation-dependent ubiquitination. Genes & development. 2012;26:235–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.182618.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Auer B, Stingl L, Berghammer H, Haidacher D, Schweiger M, Wagner EF. Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease. Genes & development. 1995;9:509–520. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZQ, Stingl L, Morrison C, Jantsch M, Los M, Schulze-Osthoff K, Wagner EF. PARP is important for genomic stability but dispensable in apoptosis. Genes & development. 1997;11:2347–2358. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang J, Ding M, Yu Y. Site-specific characterization of the Asp- and Glu-ADP-ribosylated proteome. Nature methods. 2013;10:981–984. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.