Abstract

Purpose.

A clinical vaccine that protects from ocular herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection and disease still is lacking. In the present study, preclinical vaccine trials of nine asymptomatic (ASYMP) peptides, selected from HSV-1 glycoproteins B (gB), and tegument proteins VP11/12 and VP13/14, were performed in the “humanized” HLA–transgenic rabbit (HLA-Tg rabbit) model of ocular herpes. We recently reported that these peptides are highly recognized by CD8+ T cells from “naturally” protected HSV-1–seropositive healthy ASYMP individuals (who have never had clinical herpes disease).

Methods.

Mixtures of three ASYMP CD8+ T-cell peptides derived from either HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 were delivered subcutaneously to different groups of HLA-Tg rabbits (n = 10) in incomplete Freund's adjuvant, twice at 15-day intervals. The frequency and function of HSV-1 epitope-specific CD8+ T cells induced by these peptides and their protective efficacy, in terms of survival, virus replication in the eye, and ocular herpetic disease were assessed after an ocular challenge with HSV-1 (strain McKrae).

Results.

All mixtures elicited strong and polyfunctional IFN-γ– and TNF-α–producing CD107+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, associated with a significant reduction in death, ocular herpes infection, and disease (P < 0.015).

Conclusions.

The results of this preclinical trial support the screening strategy used to select the HSV-1 ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes, emphasize their valuable immunogenic and protective efficacy against ocular herpes, and provide a prototype vaccine formulation that may be highly efficacious for preventing ocular herpes in humans.

Keywords: HSV-1, HLA transgenic rabbit, animal model, T cell, glycoprotein B, VP11/12, VP13/14, vaccine, ocular

The preclinical study characterizes a novel asymptomatic prophylactic CD8+ T-cell epitope-based herpes vaccine that protect against corneal infection and disease in the “humanized” HLA transgenic rabbit model of ocular herpes.

With a staggering one billion individuals worldwide currently carrying herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), herpes remains one of the most prevalent viral infections of the eye.1–7 Ocular herpes infection causes a spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from blepharitis, conjunctivitis, and dendritic keratitis to disciform stromal edema and blinding stromal keratitis (HSK).8,9 In the United States alone, over 450,000 people have a history of recurrent ocular HSV requiring doctor visits, antiviral drug treatments, and, in severe cases, corneal transplants.10–12 Despite the availability of many intervention strategies, the global picture for ocular herpes continues to deteriorate.13 Current antiviral drug therapies (e.g., acyclovir and derivatives) do not eliminate the virus and reduce recurrent herpetic disease by only approximately 45%.14 The development of an effective vaccine would present an unparalleled alternative to antiviral drugs, as it would be a powerful and cost-effective means to reduce HSV-1 ocular infection and lessen associated blinding ocular herpetic disease (reviewed previously1).

Our long-term goal is to develop a vaccine to prevent HSV-1 infection and protect against ocular herpes disease. The most recent vaccine clinical trials that used recombinant HSV proteins failed to protect despite inducing strong HSV-specific neutralizing antibodies. These failures emphasize three major gaps in knowledge: the need to induce strong T-cell responses (in addition to humoral responses) for protection against ocular herpes,15 the need to identify protective human herpes T-cell epitopes from HSV antigens (Ags) to be incorporated in the next generation HSV vaccines,15 and the preclinical evaluation of protective efficacy of human herpes T-cell epitopes in a reliable animal model of ocular herpes infection and disease.

One “common denominator” among previously failed vaccine clinical trials is that they either used the whole virus or whole HSV proteins (e.g., HSV glycoprotein B and/or D [gB and/or gD]), which deliver protective epitopes, nonprotective epitopes, and maybe even pathogenic epitopes (i.e., infection- or disease-enhancing epitopes, reviewed previously1). Thus, although these traditional vaccines were intended to target only HSV-specific protective B- and T-cell immunity, antigen processing also might have generated HSV-derived T-cell epitopes that elicit nonprotective T-cell responses and possibly even harmful T-cell responses.1 We recently found that HSV-1 seropositive symptomatic (SYMP) patients (with a history of numerous episodes of recurrent ocular herpes disease) tend to develop CD4+ T cells16 and CD8+ T cells1,2,4–6 that strongly recognize a subset of HSV-1 epitopes that differs from HSV-1 epitopes that are strongly recognized by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from HSV-1 seropositive healthy asymptomatic (ASYMP) individuals (who have never had clinical herpes disease), and vice versa. The former epitopes are designated as “symptomatic” or SYMP epitopes and the later are designated “asymptomatic” or ASYMP epitopes.

In the present study, based on the above observation in humans, we tested the hypotheses that: (1) an ocular herpes vaccine that exclusively includes ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes (while excluding SYMP T-cell epitopes) will be highly immunogenic and protective in the “humanized” HLA-A*02:01 transgenic rabbit (HLA-Tg rabbit) model of ocular herpes17,18 and (2) immunization of HLA-Tg rabbits with a mixture of ASYMP human herpes T-cell epitopes selected from several HSV-1 Ags will generate multiepitopes and polyfunctional protective CD8+ T-cell responses. To test these hypotheses, and to pave the way toward moving ASYMP multiepitopic peptide vaccines to clinical application, we used our recently developed HLA-Tg rabbit model.18 This preclinical animal model of ocular herpes mounts “humanized” HLA-restricted CD8+ T-cell responses to human epitopes.18

We report here that immunization of HLA-Tg rabbits with mixtures of human HSV-1 ASYMP human epitopes, selected from gB and tegument proteins VP11/12 and VP13/14, induced potent and polyfunctional HSV-specific IFN-γ– and TNF-α–producing CD107+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. These CD8+ T-cell responses were positively associated with a significant reduction in death, ocular herpes infection, and corneal herpetic disease (P < 0.015). The findings of this preclinical study strongly suggest that mixtures of HSV-1 ASYMP epitopes display promising immunogenic and protective properties to be considered in the next generation of ocular herpes vaccines, and confirm the relevance of “humanized” HLA-Tg rabbits as a useful preclinical animal model for assessing the protective efficacy of human CD8+ T-cell epitope-based vaccines against ocular herpes.

Materials and Methods

HLA-A*02:01 Tg Rabbits

A colony of HLA Tg rabbits maintained at University of California, Irvine (Irvine, CA, USA) were used for all experiments. The HLA-Tg rabbits were derived from New Zealand White rabbits.19 The HLA-Tg rabbits retain their endogenous rabbit MHC locus and express human HLA-A*02:01 under the control of its normal promoter.19 Before this study, the expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules on the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of each HLA-Tg rabbit was confirmed by FACS analysis. Briefly, rabbit PBMCs were stained with 2 μL of anti–HLA-A2 monoclonal antibodies (mAb; clone BB7.2; BD-Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA), at 4°C for 30 minutes. The cells were washed and analyzed by flow cytometer using a LSRII (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA, USA). The acquired data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR, USA). All rabbits used in these studies had a similar high level of HLA-A*02:01 expression (>90%). This eliminated any potential bias due to variability of HLA-A*0201 molecule levels in different animals. New Zealand White rabbits (non-Tg control rabbits), purchased from Western Oregon Rabbit Co. (Philomath, OR, USA), were used as controls. All rabbits were housed and treated in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmologic Research, the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC; Frederick, MD, USA), and National Institutes of Health (NIH; Bethesda, MD, USA) guidelines.

Virus Production

Strain McKrae HSV-1 was used in this study. The virus was triple plaque purified and prepared as described previously.20–22

Peptide Vaccines

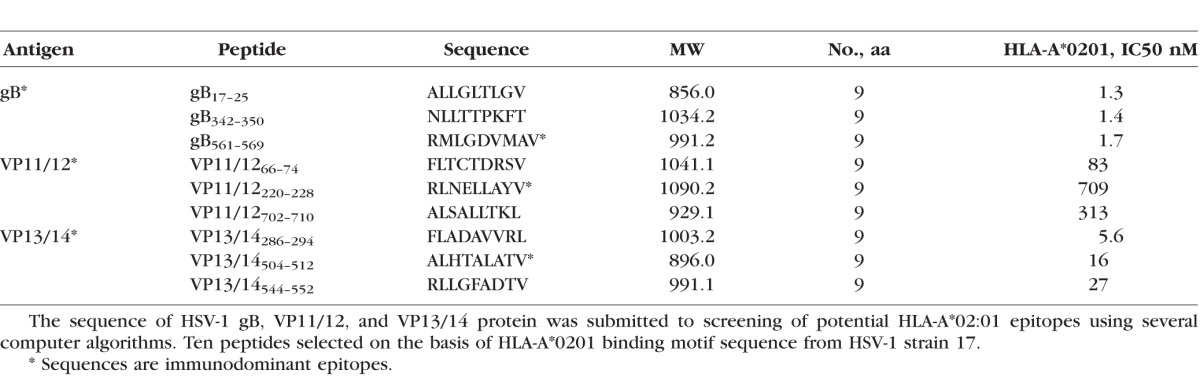

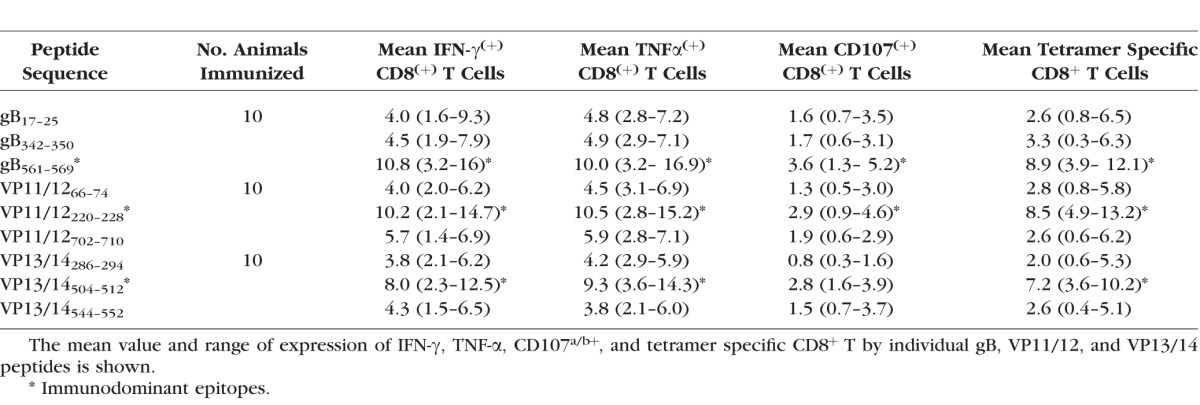

We selected 9 potential peptide epitopes from HSV-1: three from gB (gB17–25, gB342–350, and gB561–569), three from VP11/12 (VP11/1266–74, VP11/12220–228, VP11/12702–710), and three from VP13/14 (VP13/14286–294, VP13/14504–512, VP13/14544–552; Table 1). Peptide epitopes were synthesized by 21st Century Biochemicals (Marlboro, MA, USA). All peptides were HPLC purified to a purity of 95% to 98%.

Table 1.

Potential HLA-A*02:01-Restricted Epitopes Selected From Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV)

Immunization

Rabbits (HLA-Tg, 8–10 weeks) with similar, high expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules (>90%) were used, as described above. Groups of age-matched HLA-A*02:01 rabbits (n = 10 each) were immunized subcutaneously twice (2 weeks apart) with a mixture of three CD8+ peptide epitopes (each at 100 μM) delivered with the CD4+ T helper epitope (PADRE) emulsified in CpG (ODN 2007) in a total volume of 200 μL. As a negative control, a group of HLA-Tg rabbits (n = 10) were injected with adjuvant alone. Two weeks after the final immunization, both eyes were ocularly infected (challenges) as described above.

Clinical Scores

Rabbits were examined for ocular disease and survival for 30 days after challenge. Ocular disease was determined by a masked investigator using fluorescein staining and slit-lamp examination before challenge, and on days 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, and 21 thereafter. A standard 0 to 4 scale: 0, no disease; 1, 25%; 2, 50%; 3, 75%; and 4, 100% staining, was used.

Quantification of Infectious Virus

Tears were collected from both eyes using a Dacron swab (type 1; Spectrum Laboratories, Los Angeles, CA, USA) on days 3, 5, and 7 after challenge. Individual swabs were transferred to a 2 mL sterile cryogenic vial containing 1 mL culture medium and stored at −80°C until use. The HSV-1 titers in tear samples were determined by standard plaque assays on RS cells as described previously.23

PBMC Isolation

Blood (20 mL) was drawn from each rabbit into a yellow-top Vacutainer Tube (Becton Dickinson). Sera were isolated by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 800g. We isolated PBMCs by gradient centrifugation using leukocyte separation medium (Cellgro; Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in complete culture medium consisting of RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS (Bio-Products, Woodland, CA, USA) supplemented with ×1 penicillin/L-glutamine/streptomycin, ×1 sodium pyruvate, ×1 nonessential amino acids, and 50 μM of 2-mercaptoethanol (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA). Aliquots of freshly isolated PBMC also were cryopreserved in 90% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in liquid nitrogen for future testing.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

We analyzed PBMC by flow cytometry. The following antibodies were used: mouse anti-rabbit CD8 (clone MCA1576F; AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK), mouse anti-rabbit CD4 (clone MCA799F, AbD Serotec), mouse anti-human CD107a, CD107b, rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2), and mouse anti-human TNF-α, (BD-Pharmingen). For surface staining, mAbs against various cell markers were added to a total of 1 × 106 cells in PBS containing 1% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS] buffer) and left for 45 minutes at 4°C. For intracellular staining mAbs were added to the cells and incubated for 45 minutes on ice and in the dark. Cells were washed again with Perm/Wash and FACS buffer, and fixed in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For the measurement of CD107a/b, IFN-γ and TNF-α, cells were first in vitro stimulated with individual peptides. Briefly, 1 × 106 cells were transferred into 96-well flat bottom plates and stimulated with peptides (10 μg/mL in 200 μL complete culture medium) in the presence of BD Golgi stop (10 μg/mL) for 6 hours at 37°C. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 5 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) and no peptide were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. At the end of the incubation period, the cells were transferred to a 96-well round bottom plate and washed once with FACS buffer. Surface and intracellular staining was done as described above. A total of 50,000 events was acquired by LSRII (Becton Dickinson) followed by analysis using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Tetramer Assay

For tetramer-specific CD8+ T-cell response, PBMCs were analyzed for the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific to each of the three immunizing CD8+ T-cell epitopes using the corresponding HLA-A2–peptide/Tetramer as we described previously.5,16,24 A human β2-microglobulin was incorporated in the tetramers, as no rabbit β2-microglobulins are currently available. Briefly, the cells were first incubated with 1 μg/mL of PE-labeled HLA-A2–peptide/Tetramer at 37°C for 30 to 45 minutes. The cells were washed twice and stained with 1 μg/mL of FITC-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit CD8 mAb (clone MCA1576F; AbD Serotec). After 2 additional washings, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde in FACS buffer. A total of 50,000 events was acquired by LSRII followed by analysis using FlowJo software. The absolute numbers of individual peptide-specific CD8+ T cells were calculated using the following formula: (# of events in CD8+/Tetramer[+] cells) × (# of events in gated lymphocytes)/(# of total events acquired).

Statistical Analyses

Data for each assay were compared by ANOVA and Student's t-test using GraphPad Prism version 5 (La Jolla, CA, USA). Differences between the groups were identified by ANOVA and multiple comparison procedures, as we described previously.24 Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Selection of Asymptomatic HLA-A*02:01-Restricted T-Cell Epitopes From HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 Proteins

Nine ASYMP peptide epitopes that induced strong CD8+ T-cell responses from “naturally” protected HSV-1–seropositive healthy ASYMP individuals (who have never had clinical herpes disease), but not from SYMP individuals, were selected from HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 proteins. We recently reported that these peptide epitopes induced significantly higher expression of granzyme B (GzmB), granzyme K (GzmK), perforin (PFN), degranulation marker CD107a/b, and IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells from ASYMP, compared to SYMP individuals.4,5,25,26 Briefly, in 10 sequentially studied HLA-A*0201 positive, HSV-1 seropositive ASYMP individuals, the most frequent, robust, and polyfunctional gB-specific CD8+ T-cell responses, as assessed by a combination of tetramer, IFN-γ-ELISpot, CFSE proliferation, CD107a/b cytotoxic degranulation, expression of GzmB, GzmK, PFN, were directed mainly against gB17–25, gB342–350, and gB561–569 epitopes. Similarly, 3 of 10 potential VP11/12 peptides, VP11/1266–74, VP11/12220–228, and VP11/12702–710, were selected as being highly recognized by CD8+ T cells from 10 HSV-1 seropositive ASYMP individuals, while CD8+ T cells from ASYMP individuals significantly reacted to 3 of 10 VP13/14 epitopes (VP13/14286–294, VP13/14504–512, and VP13/14544–552).

As an important initial phase in the development of an ocular herpes subunit vaccine, we next determined the capacity of these peptides to induce sustained CD8+ T-cell responses in vivo. We tested the hypothesis that immunization with mixtures of ASYMP synthetic peptides bearing these T-cell epitopes from gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 would stimulate strong, functional, and multiepitope CD8+ T cells in the ocular herpes HLA-A*02:01 transgenic (HLA-Tg) rabbit model.

Selection of HLA-A*02:01 Tg Rabbits for Preclinical Evaluation of the Efficacy of HSV-1 ASYMP CD8+ Peptide Vaccines Against Ocular Herpes

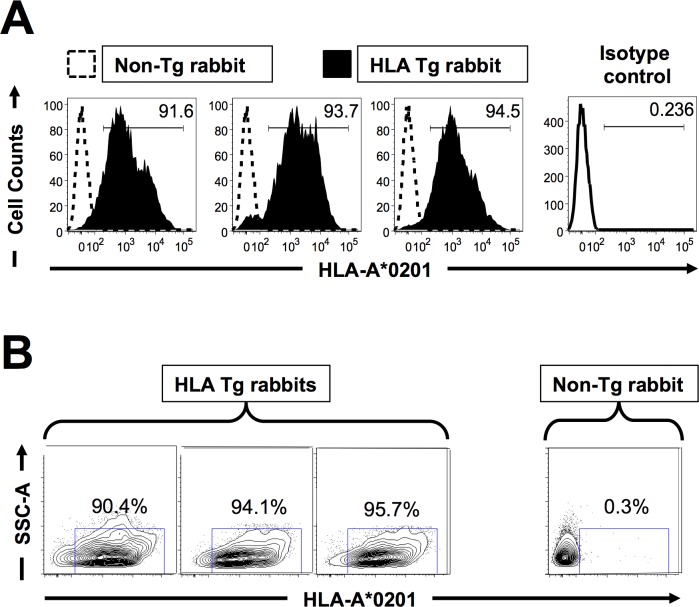

We first selected HLA-Tg rabbits with similar high expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules, since expression of the rabbits' own MHC class I molecules might interfere with the human HLA-A*02:01-restricted responses.18 All rabbits used had similar high expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules in over 90% of PBMC by FACS (Figs. 1A, 1B). As expected, no HLA-A*02:01 expression was detected in wild-type (nontransgenic) rabbits (negative controls). The specificity of anti-human HLA-A*02:01 antibody was confirmed using an isotype IgG control. The high expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules in the selected HLA-Tg rabbits should result in rabbit CD8+ T cells using the human HLA-A*02:01 molecules at the thymic selection and peripheral effector levels.18

Figure 1.

Detection of HLA-A*02:01 molecules in PBMC of HLA transgenic rabbits. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from either HLA-Tg rabbits or from wild type nontransgenic rabbits (8–10 weeks old) were stained with PE conjugated anti–HLA-A2 mAb, (clone BB7.2) and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Level of expression of HLA-A2 molecules on the surface of APCs. (B) Percentage of APCs expressing HLA-A2 molecules. The results are representative of three independent experiments. For subsequent immunogenicity and protection studies all of the HLA-Tg rabbits used had high expression of HLA-A*02:01 molecules (>90%).

Frequent HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 Epitope-Specific CD8+ T Cells Induced in HLA-Tg Rabbits by Mixtures of ASYMP Peptides

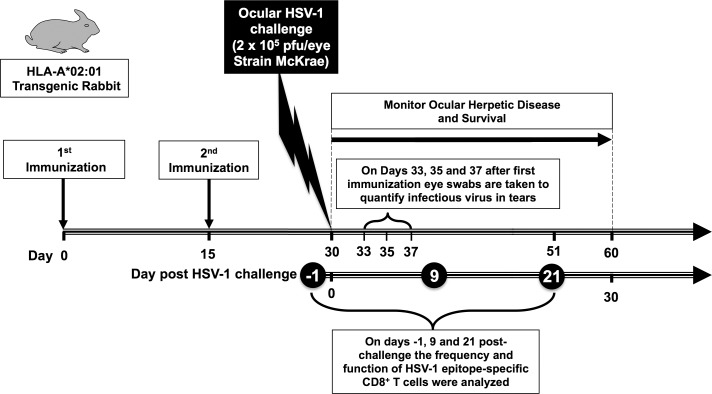

To gain insight into the immunogenicity of HSV-1 asymptomatic peptide vaccines, and to obtain maximal information from limited numbers of animals, we analyzed the HSV-1 epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in 3 groups of HLA-Tg rabbits (n = 10) each immunized with mixtures of 3 ASYMP CD8+ T-cell peptides derived from gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 molecule (i.e., gB17–25, gB342–350, and gB561–569 in Group 1; VP11/1266–74, VP11/12220–228, and VP11/12702–710 in Group 2; and VP13/14286–294, VP13/14504–512, and VP13/14544–552 in Group 3, as shown in Table 1). Because concomitant induction of T helper CD4+ T cells is crucial in the priming and maintenance of HSV-specific CD8+ T cells,5,27 each mixture of CD8+ T-cell epitopes was delivered with PADRE, a promiscuous HSV-1 CD4+ T helper epitope that binds to most MHC class II molecules, including rabbit MHC class II molecules.5,18 As illustrated in Figure 2, 15 days after the second immunization each animal received an ocular challenge with HSV-1 (2 × 105 plaque-forming units [pfu]/eye, strain McKrae).

Figure 2.

Illustration of peptide immunization regimen, HSV-1 challenge, T-cell immunogenicity, and protective efficacy studies in HLA-Tg rabbits. Three groups of age-matched HLA-A*02:01 rabbits (n = 10 each) were immunized subcutaneously twice (on days 0 and 15) with CD8+ peptide epitopes as outlined in Materials and Methods. As a negative control, a fourth group of HLA transgenic rabbits (n = 10) received adjuvant alone (mock-vaccinated). Two weeks after final immunization, HLA-Tg rabbits were ocularly challenged (both eyes, without scarification) with 2 × 105 pfu of HSV-1 (strain McKrae) delivered as eye drops in 20 μL of tissue culture media. Rabbits were examined for ocular disease immediately before ocular challenge, and on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 thereafter. Survival was determined in a window of 30 days after challenge. Tears from both eyes were collected by swabbing rabbit eyes with a Dacron swab on days 3, 5, and 7 after challenge for titration of viral load. Frequency and function of HSV-1 epitope-specific CD8+ T cells were analyzed on days −1, 9, and 21 post challenge.

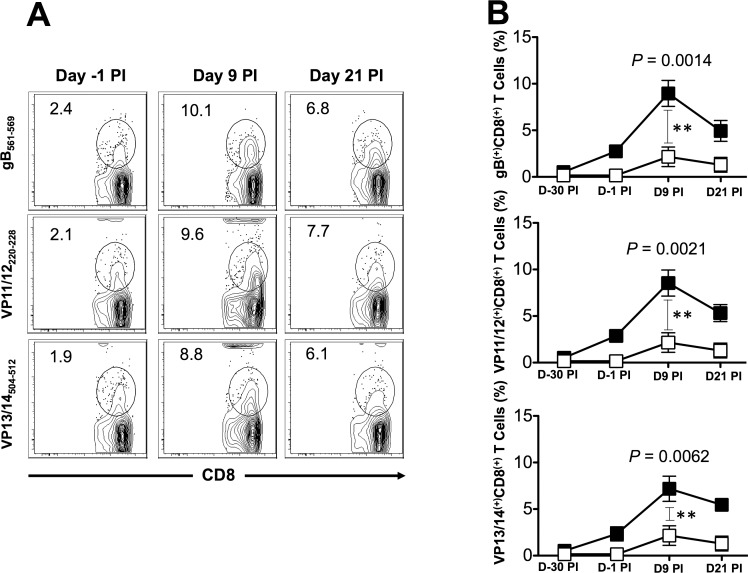

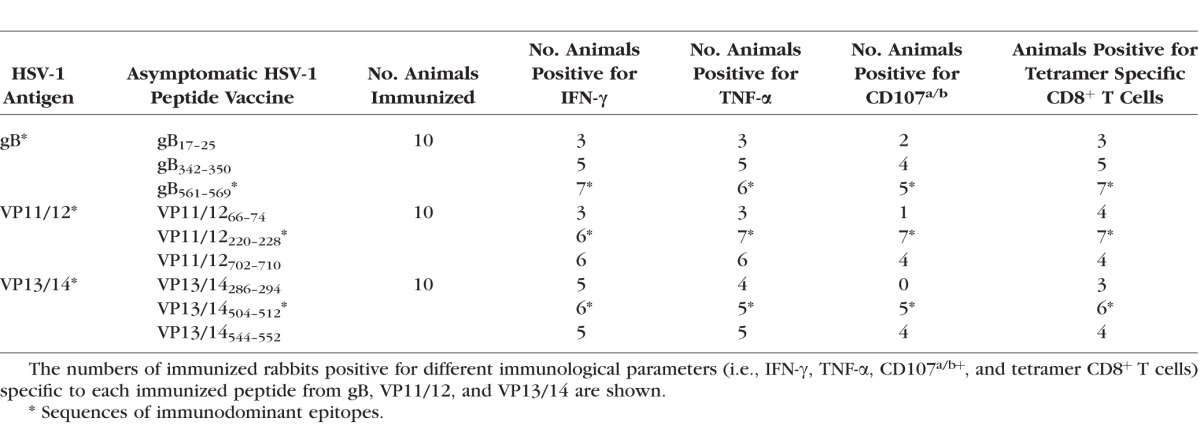

The frequencies of CD8+ T cells were determined in PBMC from each animal, using human epitope-specific tetramers before immunization, 14 days after second immunization (i.e., −1 before HSV-1 challenge), and 9 and 21 days after challenge. As shown in Figures 3A and 3B and in Tables 2 and 3, one of the three gB peptides (gB561–569), one of the three peptides from VP11/12 (VP11/12220–228), and one of the three peptides from VP13/14 (VP13/14504–512) elicited significantly higher frequencies of CD8+ T cells in the majority of immunized HLA-Tg rabbits compared to mock-immunized HLA-Tg rabbits (P < 0.01). The remaining six peptides from gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 (i.e., gB17–25, gB342–350, VP11/1266–74, VP11/12702–710, VP13/14286–294, and VP13/14544–552) induced moderate to low CD8+ T-cell responses. The frequency of CD8+ T cells induced by each of the three immunodominant ASYMP epitopes (i.e., gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512) was boosted following HSV-1 challenge (Fig. 3B), suggesting that CD8+ T cells induced by these synthetic “artificial” peptide epitopes were able to be recognized and be boosted by the “native” HSV-1 epitopes following HSV-1 challenge. Interestingly, most animals (6 of 10) developed CD8+ T cells against the VP11/12220–228 peptide. Five of 10 animals showed significant responses to gB561–569 and to VP13/14504–512 (Table 2). As expected, none of the control animals that received adjuvant alone (mock-vaccinated) showed significant increase in percentage of CD8+ T cells specific to any of the epitopes tested (Fig. 3B). Collectively, frequent CD8+ T cells were detected against each of the three HSV-1 Ags, pointing to induction of strong T-cell immunogenicity by mixtures of ASYMP epitopes.

Figure 3.

Frequency of gB-, VP11/12-, and VP13/14-specific CD8+ T cells induced in HLA-Tg rabbits after immunization and virus challenge. We immunized HLA-Tg rabbits twice as shown in Figure 2 with mixtures of ASYMP peptides from gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 antigens and bled 15 days after the second immunization (i.e., 1 day before challenge). Animals were ocularly challenged with HSV-1 and bled on days 9 and 21 after challenge as shown in Figure 2 above. Blood from mock-immunized rabbits that received adjuvant alone was used as a negative control. We isolated PBMCs from blood at the indicated time points and the frequency of HSV-1 epitope-specific CD8+ T cells was determined specific to each of the three immunizing CD8+ T-cell epitopes using the corresponding HLA-A2-peptide/Tetramer. (A) Representative contour plot of tetramer CD8+ T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes in PBMCs from immunized rabbits. The numbers at the top of each box represents the percentages of epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells. (B) Average frequency of tetramer specific CD8+ T cells. Solid squares represent immunized rabbits. Open squares represent mock-immunized rabbits. The results are representative of 2 independent experiments. The indicated P values, calculated using the ANOVA test, show statistical significance between peptide immunized and mock-immunized rabbits on day 9 after infection.

Table 2.

Number of HLA-Tg Rabbits With Positive CD8+ T-cell Responses Detected in a Group of 10 Animals Immunized With Mixtures of gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 ASYMP Peptides

Table 3.

Average CD8+ T-Cell Frequencies and Responses Detected in 10 HLA-Tg Rabbits Immunized With Mixtures of gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 ASYMP Peptides

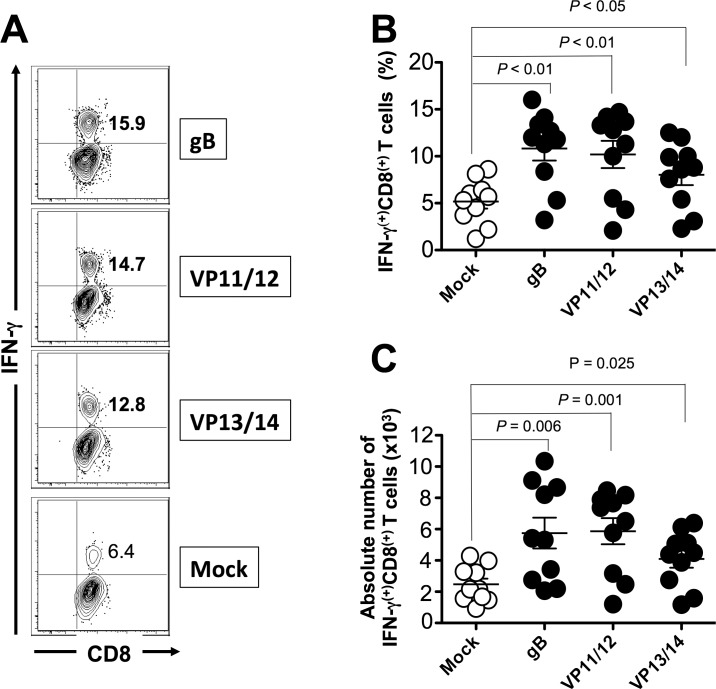

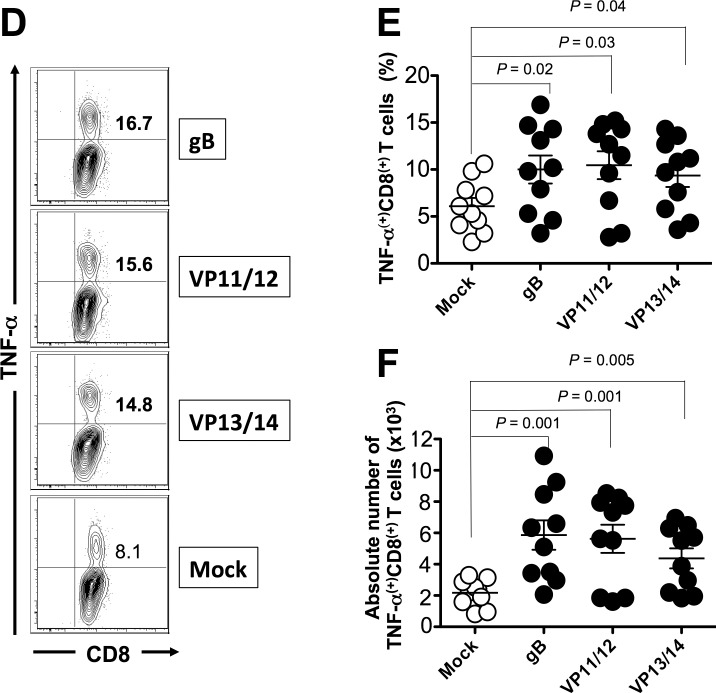

Induction of Polyfunctional CD8+ T Cells in HLA-Tg Rabbits by Mixtures of HSV-1 ASYMP Peptides

We next determined whether the mixtures of ASYMP epitopes from HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 will induce functional CD8+ T cells in terms of IFN-γ, TNF-α-production, and CD107 expression (i.e., cytotoxic activity). As shown in Figures 4A through 4C and in Table 2, 9 days after the challenge, at the time of acute infection, three of the nine peptides (one from each Ag) elicited significant IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells in PBMC from HLA-Tg rabbits. Of the three peptides selected from VP11/12, VP11/12220–228 elicited significantly higher IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells (Tables 2, 3). Lower, but significant levels of IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells were generated against VP11/12702–710, but no cytotoxic activity was detected against the remaining VP11/1266–74 peptide (Tables 2, 3). Similar results were obtained when CD8+ T cells were tested for production of TNF-α (Figs. 4D–F; Table 2). In addition, CD8+ T cells derived from immunized HLA-Tg rabbits showed cytolytic activity against gB561–569 peptide and low but consistent cytotoxic T-cell responses against the remaining gB peptides (gB17–25 and gB342–350; Figs. 4G–I; Tables 2, 3). As expected, none of the peptides elicited significant CD8+ T-cell responses in mock-vaccinated HLA-Tg rabbits (Fig. 4). Most animals (6 of 10) developed CD8+ T-cell responses against a single gB peptide (gB561–569; Tables 2, 3). In contrast, 6 of 10 animals showed potent IFN-γ–producing CD107+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells to two VP11/12 peptides (VP11/1266–74 and VP11/12220–228; Tables 2, 3). Interestingly, most animals developed CD8+ T-cell responses against all three VP13/14 peptides (Tables 2, 3). Six of 10 animals showed potent IFN-γ–producing CD107+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells to VP13/14504–512 while five showed significant response to VP13/14286–294 and VP13/14544–552. Collectively, the results point to polyfunctionality of CD8+ T cells induced by mixtures of ASYMP epitopes from HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14.

Figure 4.

Mixture of ASYMP peptides from gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 induce polyfunctional IFN-γ– and TNF-α–producing CD107(+)CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and expression of CD107a/b by CD8+ T cells was determined from PBMC of peptide immunized and mock-immunized HLA-Tg rabbits 9 days after HSV-1 challenge, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Representative contour plot of IFN-γ(+)CD8(+) T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes detected in PBMCs from immunized and control mock-immunized rabbits. (B) Average frequency and (C) average absolute number of IFN-γ(+)CD8(+) T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes detected in PBMCs from 10 immunized and 10 control mock-immunized rabbits. (D) Representative contour plot of TNF-α(+)CD8(+) T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes detected in PBMCs from immunized and control mock-immunized rabbits. (E) Average frequency and (F) average number of TNF-α(+)CD8(+) T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes detected in PBMCs from 10 immunized and 10 control mock-immunized rabbits. (G) Representative contour plot of CD107a/b(+)CD8(+) T cells detected in immunized and mock immunized rabbits. (H) Average frequency and (I) average absolute numbers of CD107a/b(+)CD8(+) T cells specific to gB561–569, VP11/12220–228, and VP13/14504–512 epitopes detected in PBMCs from 10 immunized and 10 control mock-immunized rabbits. Solid circles represent immunized HLA rabbits and open circles represent mock-immunized rabbits. The results are representative of 2 independent experiments. The indicated P values, calculated using ANOVA test, show statistical significance between mock and immunized rabbits.

Figure 4.

Continued.

Figure 4.

Continued.

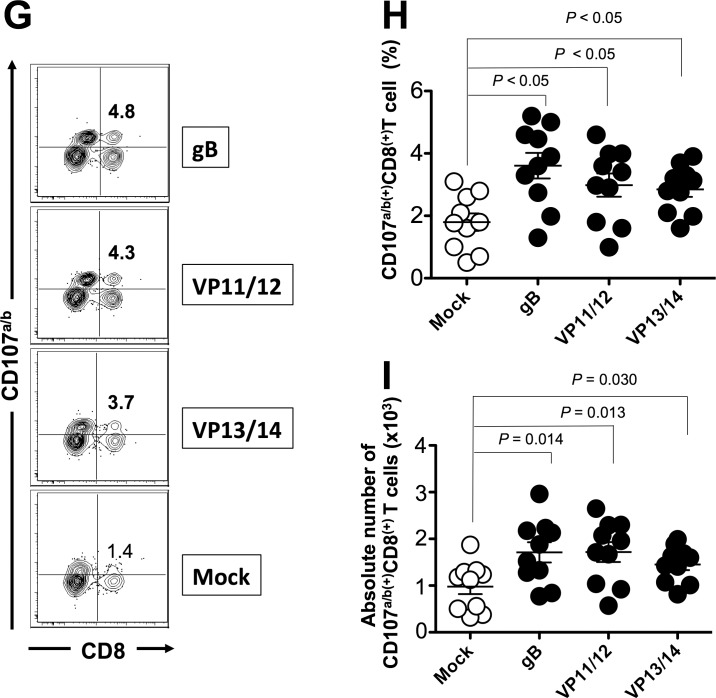

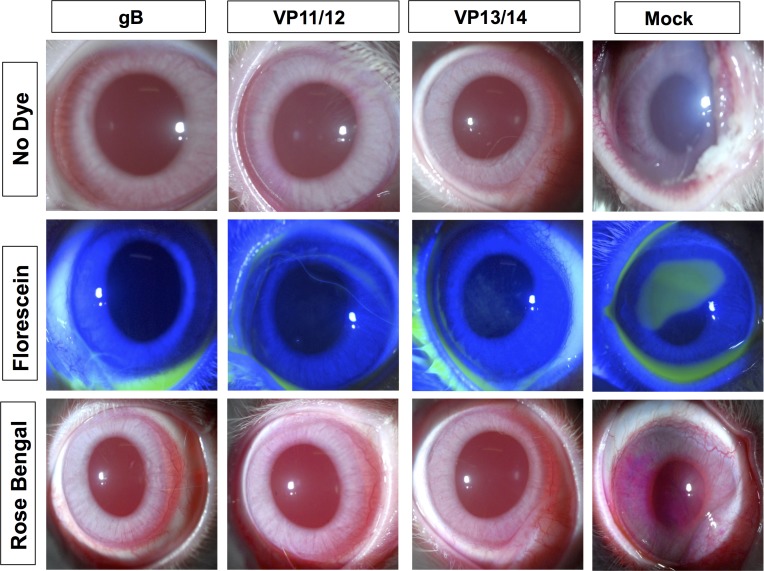

Protective Efficacy Against Ocular HSV-1 Infection and Disease

Groups of HLA-Tg rabbits (n = 10 mice per group) were immunized subcutaneously twice as above. As illustrated in Figure 2, two weeks after the final immunization, animals from all groups received an ocular HSV-1 challenge (2 × 105 pfu, McKrae strain) without scarification. The rabbits then were assessed for up to 30 days post challenge for ocular herpes pathology, ocular viral titers, and survival.

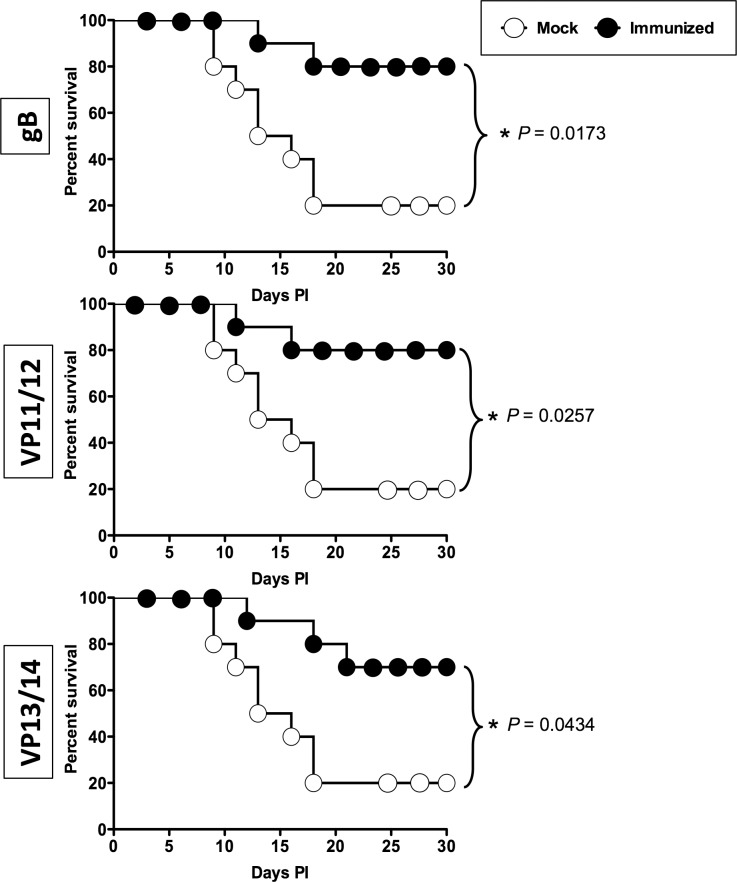

As shown in Figures 5A and 5B, on day 10 after infection, the pathology clinical scores observed in the immunized groups were significantly lower compared to those recorded in the mock-immunized group (P < 0.01 for all). Furthermore, significantly less virus was detected on day 7 post infection (the peak of viral replication) in the eye swabs of the vaccinated groups compared to the mock-immunized group (P < 0.01, Fig. 5C). Most animals in the vaccinated groups survived infection (80%–70%) compared to only 30% survival in the mock-immunized group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5D). The mixtures of gB and VP11/12 peptides showed a trend to provide better protection than the VP13/14 peptide mixture.

Figure 5.

Protective immunity against corneal disease, ocular herpes replication, and survival induced by ASYMP gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 CD8+ T-cell epitopes in HLA transgenic rabbits. Two weeks after the final immunization, all animals were challenged ocularly with 2 × 105 pfu of HSV-1 (strain McKrae) and examined for signs of ocular disease, virus titer, and survival in a window of 30 days after infection. (A) On day 10 after infection, the corneal epithelial cells of HLA-Tg rabbits were stained with topical dye (fluorescein or rose Bengal) to characterize ocular surface diseases and quantify their severity. Fluorescein and rose Bengal are instilled as a drop at a concentration of 0.1% to 1% at the surface of the eye. Rabbit eye images were taken under the correct color light using slit-lamp (blue for fluorescein and red for Rose Bengal). After staining the eyes were rinsed with PBS. The images show uptake of dye in the mock group and absence of the staining in the immunized group. (B) Clinical assessments by slit-lamp were made before inoculation, and on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, and 21 thereafter. The examination was performed by investigators blinded to the treatment regimen of the rabbit eyes and scored according to a standard 0 to 4 scale: 0, no disease; 1, 25%, 2, 50%; 3, 75%; 4, 100%. (C) Virus titrations were determined from eye swabs on days 3, 5, and 7 post infection. Rabbits were swabbed with moist, type 1-calcium alginate swabs and titrated on RS cell, as described in Material and Methods. The maximum virus titers obtained on day 7 are shown. (D) Survival was determined in a window of 30 days post challenge, as described in Material and Methods, using Kaplan Meier Test to show statistical significance between mock and immunized rabbits. Solid circles represent immunized and open circles represent mock-immunized rabbits. The results are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Figure 5.

Continued.

Figure 5.

Continued.

Altogether, these results indicated that immunization with mixtures of ASYMP peptide CD8+ T-cell epitopes from HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 decreased ocular herpes disease, decreased virus replication, and protected against lethal ocular herpes in the HLA-Tg rabbit model of ocular herpes; and support HLA-A*02:01 Tg rabbits as a useful animal model for investigating the underlying mechanisms by which CD8+ T cells specific to human HSV-1 CD8+ T-cell epitopes mediate control of ocular herpes infection and disease.

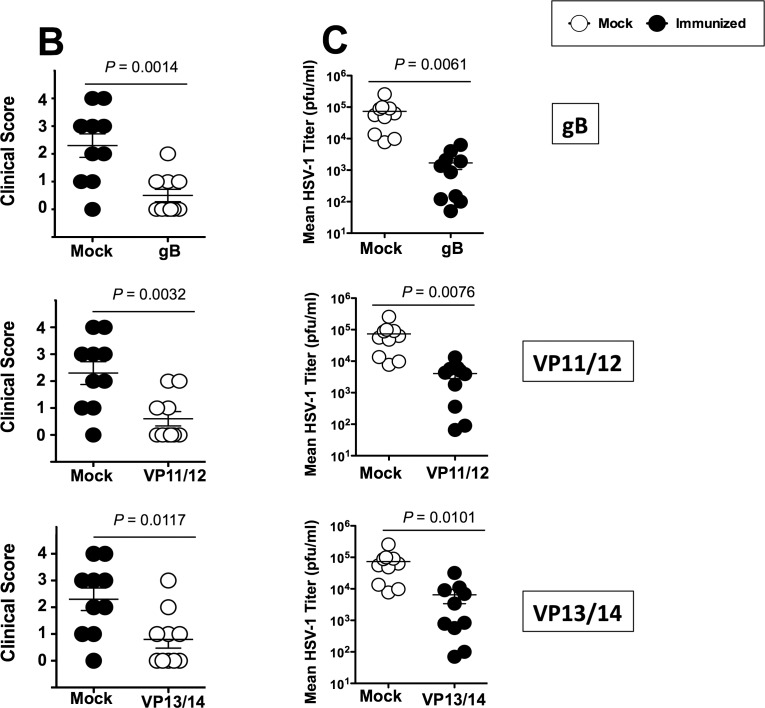

Frequent and Polyfunctional CD8+ T Cells Specific to HSV-1 ASYMP Epitopes Are Associated With Reduced Corneal Herpetic Disease in Immunized HLA-Tg Rabbits

Antibody depletion of CD8+ T cells often is used in mice to determine if a protective immunity is CD8+ T-cell dependent. Unfortunately, at this time, in vivo CD8+ T-cell depletion studies are not feasible in rabbits because of the lack of a suitable in vivo depleting antibody. Thus, we determined whether the observed protection against recurrent ocular herpes was associated with frequency and function of CD8+ T cells specific to ASYMP HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 epitopes.

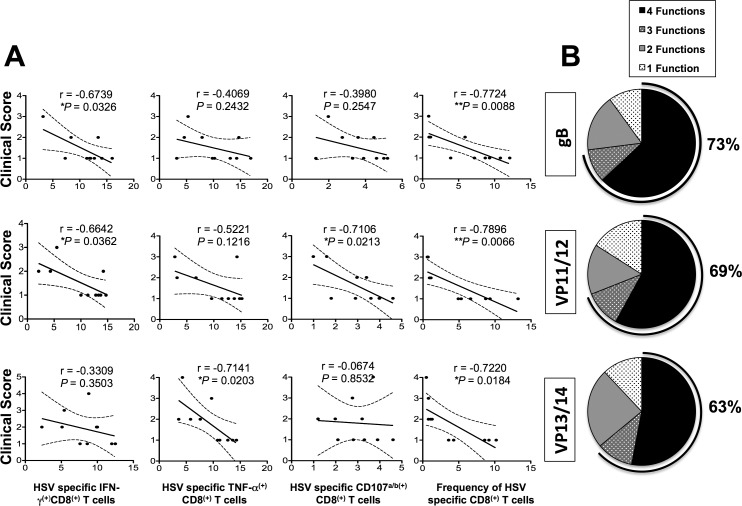

The function of CD8+ T cells specific to HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 epitopes was detected using specific tetramers together with intracellular staining for TNF-α and IFN-γ and surface expression of CD107a/b, as described in Materials and Methods. There were significantly more HSV-specific IFN-γ–producing CD8+ T cells (Fig. 6, Table 3) in protected HLA-Tg rabbits compared to unprotected rabbits. Approximately two-thirds (73%, 69%, and 63%) of HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells in protected HLA-Tg rabbits, respectively, expressed at least two functions (i.e., production of IFN-γ and cytotoxic activity measured by expression of CD107a/b). In contrast, less than a third (27%) of the HSV-1 epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells in mock-vaccinated unprotected HLA-Tg rabbits expressed two functions. Thus, high proportions of polyfunctional HSV-specific CD8+ T cells coproducing IFN-γ and CD107a/b (two immune effectors known to be associated with protection against ocular herpes) appeared to be associated with protection in HLA-Tg rabbits.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the frequency and function of HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 ASYMP epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells and severity of corneal disease in immunized HLA transgenic rabbits. (A) Correlation between clinical scores and HSV-specific (i) IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells, (ii) TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells, (iii) CD107a/b+ CD8+ T cells, and (iv) frequency of CD8+ T cells in gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 immunized rabbits. Several immunological parameters such as T-cell frequency (using epitope-specific tetramers) and functions (by determining expression cytotoxic molecule CD107a/b, proliferating and producing IFN-γ and TNF-α) by HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 ASYMP epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells were correlated in various groups of immunized HLA-Tg rabbits with severity of corneal symptoms using Spearman's test. In all panels, black circles denote individual rabbits, and the R and P values determine the average detected in 10 rabbits per group. (B) Pie charts show cumulative percentage of animals developing HSV-1 ASYMP epitope-specific CD8+ T cells with one, two, three, and four functions.

Altogether, these results suggested that TNF-α– and IFN-γ–producing HSV-specific CD107+CD8+ cytotoxic T cells might have a role in limiting ocular herpes infection and disease.

Discussion

Herpes simplex virus-1 ASYMP epitopes-specific CD8+ T-cell responses assessed in vitro, correlate with less frequent and less severe ocular herpetic disease in HSV-seropositive individuals.4,16,25,26,28–33 We wanted to determine whether in vivo immunization with these human ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes induces frequent and polyfunctional HSV-specific CD8+ T cells that reduce herpetic corneal disease. Using the new “humanized” HLA-Tg rabbit model of ocular herpes infection and disease, we characterized the T-cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy of nine human ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes that we recently identified from three major HSV-1 Ags, namely, gB, tegument proteins VP11/12, and VP13/14.25,26 We showed that immunization with mixtures of HSV-1 ASYMP peptides elicited polyfunctional CD8+ T-cell responses in HLA-Tg rabbits and protected HLA-Tg rabbits from ocular herpes infection and disease following an ocular challenge. These preclinical results indicated that these ASYMP T-cell epitopes from glycoprotein gB, and from tegument proteins VP11/12 and VP13/14 are logical candidates to be included in the next generation of ocular herpes vaccines.

Although full-length proteins generally are regarded as ineffective immunogens for CD8+ T-cell responses,34 the 9-mer peptides used here have the optimal length for binding with high affinity to HLA class I molecules. There are several advantages of a vaccine comprised of multiple peptide epitopes: HSV-1 ASYMP epitopes can be included and HSV-1 SYMP epitopes can be avoided, and epitopes from multiple viral proteins can be included. This is likely to produce even more efficacious protection than any one of the 3 epitope mixtures (each from a different viral protein) used here. Multiple HLA class I haplotypes, beside HLA-A*02:01, can be targeted (reviewed previously2). Moreover, the mixtures of asymptomatic peptides vaccine did boost the number and function of local HSV-specific CD8+ T cells in protected HLA-Tg rabbits, while the number and function of local HSV-specific CD8+ T cells were significantly lower in unprotected HLA-Tg rabbits. These findings are in agreement with our recent report showing lower frequencies of functional HSV-1 gD epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells in protected HLA-Tg rabbits compared to more dysfunctional exhausted PD1+CD8+ and TIM-3+CD8+ T cells in unprotected HLA-Tg rabbits.17 Thus, the present results highlight the potential of mixtures of peptides vaccine for activating potent functional CD8+ T-cell responses against ocular herpes, compared to immunization with a single immunodominant peptide.13,35–38

In these studies, mixtures of peptides, instead of individual peptides, were used because only small cohorts of HLA-Tg rabbits were available. A possible concern of a multipeptide vaccine is the possibility of epitope competition among the mixtures of epitope peptides for specific HLA-A*02:01 molecules. This could impair induction of a full spectrum of T-cell responses against all of the desired ASYMP epitopes. One approach to avoid this possibility would be to administer individual peptides at different injection sites. It is noteworthy that in this report, using peptide epitope mixtures for immunization, CD8+ T-cell responses were induced in HLA-Tg rabbits by 6 of the 9 peptides studied (Tables 2, 3). The polyfunctionality of induced CD8+ T cells may have a critical role in protection against ocular herpes infection and disease, since the quality of CD8+ T-cell responses, rather than their quantity (i.e., frequency of CD8+ T cells and magnitude of CD8+ T-cell responses) correlated better with protection.

To the best of our knowledge, the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of asymptomatic epitopes from glycoproteins B and D, and from tegument proteins, such as VP11/12 and VP13/14, have never been described in rabbits. Thus, the results of the present study revealed for the first time the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of several new CD8+ T-cell epitopes from many HSV-1 proteins, expanding the panel and diversity of HSV-1 Ags epitopes, and confirming that tegument proteins can induce strong CD8+ T-cell responses.

Traditional vaccine formulations using recombinant proteins are generally ineffective at induction of CD8+ T-cell responses.34 This limitation results from the basic biology of Ag processing and presentation of CD8+ T-cell epitopes, which necessitates endogenous synthesis and presentation in the context of HLA class I molecules. Through identification of protective human ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes from HSV-1 proteins, herpes vaccine formulations can be simplified, enabling molecular-level vaccine characterization and improved safety profiles. We demonstrated the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of mixtures of several HSV-1 epitopes derived from 3 different HSV-1 proteins against ocular herpes infection and disease. This epitope-based approach, however, comes at the expense of decreased immunogenicity, requiring the addition of immunoadjuvants, as well as mixing and delivering of multiple epitopes from one or several Ags.34 Moreover, we found that HSV-1 ASYMP epitopes-specific polyfunctional CD8+ T cells induced by these molecular vaccines correlated with reduced corneal disease.

It is estimated that approximately 450,000 adults in the United States have a history of recurrent herpetic ocular disease (symptomatic; SYMP individuals), with approximately 20,000 individuals per year experiencing recurrent, painful, and potentially blinding ocular herpetic lesions.1,2,4–6 The seropositive SYMP and ASYMP individuals are different with regards to HSV-1 epitopes-specificity (the magnitude and the nature of their CD8+ T cells1–6,16,24,25,39 Thus, a vaccine that converts the presumably nonprotective profile of CD8+ T cells seen in SYMP patients into the protective profile seen in ASYMP individuals will likely lead to a decrease in ocular herpes infection and disease. In the present study, we demonstrated that immunization with mixtures of peptide vaccines exclusively bearing human ASYMP gB, VP11/12, or VP13/14 epitopes, that are mainly recognized by CD8+ T cells from HSV-1 seropositive healthy ASYMP individuals who have never had clinical herpes disease,6,7 reduced infectious virus in tears and lessened ocular herpes following ocular challenge in prophylactically immunized HLA-Tg rabbits. This peptide vaccine excludes SYMP epitopes that are recognized mostly by CD8+ T cells from SYMP individuals with a history of numerous episodes of recurrent ocular herpes disease. It remains to be determined whether this ASYMP epitopes vaccine given therapeutically to latently infected HLA-Tg rabbits will significantly decrease virus reactivation from TG (virus shedding in tears) and/or recurrent ocular disease, and increase the numbers and functions of local HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 epitopes specific CD8+ T cells over the existing immune response induced by the primary infection. Preclinical studies in HLA-Tg rabbits assessing the protective efficacy of these ASYMP epitopes vaccines in a therapeutic setting will be the subject of future reports.

Mice have been the animal model of choice for most immunologists, and results from mice have yielded tremendous insights into the role of T cells in protection against primary herpes infection.5,16,40–44 In addition, HLA-Tg mice can develop T-cell responses to human epitopes.4 From a practical standpoint, the size of rabbit cornea is significantly larger than those of mice and offer plentiful amount of tissues for phenotypic and functional characterization of HSV-specific T cells using individual tissues.17,45–48 In addition, compared to mice, the surfaces of the rabbit and human eye are relatively immunologically isolated from systemic immune responses.47 To overcome the hurdle that rabbits do not mount T-cell responses specific to human HLA-restricted human epitopes, we recently introduced a novel “humanized” HLA-Tg rabbit model of ocular herpes in which the rabbits express HLA (HLA class I molecules).18,49 This novel HLA-Tg rabbit mounts CD8+ T-cell responses specific to HLA-restricted epitopes similar to humans. Since expression of the rabbits' own MHC class I molecules might interfere with the human HLA-A*02:01-restricted responses,9 and to ensure that all rabbits have high level of expression of HLA-A*0201 molecules in over 90% of their CD8+ T-cells, only those HLA-Tg rabbits with these characteristics were used in these studies. We previously reported that all gD epitopes that are recognized by CD8+ T cells from HSV-1 infected HLA-Tg rabbits are recognized by CD8+ T cells from HLA-A*0201–positive HSV seropositive humans.18 Thus, the HLA-Tg rabbit model will be useful for preclinical testing of candidate vaccines bearing human T-cell epitopes.

The human population is genetically diverse in terms of HLA haplotypes. Thus, a question of practical importance is the translation of the current immunological findings in a single HLA-Tg rabbit strain for the development of an epitope-based vaccine for a genetically heterogeneous human population. We chose the HLA-A*02:01 haplotype in this study because: (1) >51% of humans, regardless of age, sex, ethnicity, and race, are this haplotype,2 and (2) we have HLA-A*02:01 Tg rabbits available for in vivo studies. Previous comparisons of HLA frequencies among cohorts of genital herpes patients showed associations of HLA-B27 and -Cw2 with symptomatic disease.50 In contrast, we have not detected any correlations between any particular HLA class I or class II haplotype and resistance or susceptibility to ocular herpes disease (unpublished data). Thus, we do not think the difference in ocular herpetic disease is due to a particular HLA haplotype. Although the high degree of HLA polymorphism often is pointed to as a major hindrance to the use of epitope-based vaccines, this can be overcome by the inclusion of multiple supertype-restricted epitopes, recognized in the context of diverse related HLA alleles, and by designing mixtures of peptide-based vaccines with higher epitope densities. Thus, broad population coverage can be established, providing that epitopes corresponding to multiple HLA supertype families are incorporated into the vaccine. A combination of nine HLA supertypes can provide greater than 99% coverage of the entire repertoire of HLA molecules.51,52 A multiepitope-based herpes vaccine could also include several T-cell epitopes present not only in one herpesvirus glycoprotein, such as gD, but also in several different proteins chosen to represent the HLA supertypes known to provide recognition in a large proportion of the global population. Such a multiepitope T cell–based vaccine would be broadly effective in the vast majority of individuals regardless of their HLA haplotype.

Whether the vaccine results obtained from the HLA-Tg rabbit model will correlate with vaccine results in humans remains to be determined in future studies. The advances in the present study offer great promise for mixture peptide-based vaccines. It will take time to optimize the parameters that influence immunogenicity of peptide-based herpes simplex vaccine, including route of immunization, method of antigen attachment, particle size, and composition (i.e., synthetic, or self-assembling, e.g., virus-like particles). A general principle is that immunogenicity is greatly enhanced by delivering peptide epitopes and TLR (or other innate immune receptor) activating substances in the same particle.53–55 Finally, it also will be important to determine the potency of mixture peptide-based vaccines in nonhuman primates and humans.

In conclusion, there are three principal findings in the present report. First, a human herpes vaccine that exclusively contains a mixture of human ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes derived from HSV-1 gB, VP11/12, and VP13/14 provides protection in HLA-A*02:01 Tg rabbits against ocular herpes infection and disease. Second, frequent polyfunctional HSV-1 ASYMP epitopes-specific CD8+ T cells were induced by mixtures of ASYMP human epitopes in protected HLA-Tg rabbits, suggesting their contribution in protection. Third, the study validates the HLA-A*02:01 Tg rabbit model of ocular herpes for preclinical testing of future herpes vaccine candidates bearing human ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitopes against ocular herpes. Overall, this preclinical therapeutic vaccine study in HLA-A*02:01 Tg rabbits provides optimism for the evaluation of a T-cell vaccination approach using multiple minimal ASYMP epitope peptides and paves the way for the clinical testing of ASYMP CD8+ T-cell epitope-based vaccines against recurrent ocular herpes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alison Deckhut Augustine and Dale Long from the NIH Tetramer Facility (Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA) for providing the Tetramers used in this study. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Supported by Public Health Service Research Grants EY019896, EY14900, and EY024618 from the NIH, The Discovery Center for Eye Research, and Research to Prevent Blindness.

Disclosure: R. Srivastava, None; A.A. Khan, None; J. Huang, None; A.B. Nesburn, None; S.L. Wechsler, None; L. BenMohamed, None

References

- 1. Kuo T,, Wang C,, Badakhshan T,, Chilukuri S,, BenMohamed L. The challenges and opportunities for the development of a T-cell epitope-based herpes simplex vaccine. Vaccine. 2014; 32: 6733–6745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Samandary S,, Kridane-Miledi H,, Sandoval JS,, et al. Associations of HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C alleles frequency with prevalence of herpes simplex virus infections and diseases across global populations: implication for the development of an universal CD8+ T-cell epitope-based vaccine. Hum Immunol. 2014; 75: 715–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chentoufi AA,, Dervillez X,, Rubbo PA,, et al. Current trends in negative immuno-synergy between two sexually transmitted infectious viruses: HIV-1 and HSV-1/2. Curr Trends Immunol. 2012; 13: 51–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dervillez X,, Qureshi H,, Chentoufi AA,, et al. Asymptomatic HLA-A*02:01-restricted epitopes from herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B preferentially recall polyfunctional CD8+ T cells from seropositive asymptomatic individuals and protect HLA transgenic mice against ocular herpes. J Immunol. 2013; 191: 5124–5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chentoufi AA,, Zhang X,, Lamberth K,, et al. HLA-A*0201-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes identified from herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D. J Immunol. 2008; 180: 426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang X,, Dervillez X,, Chentoufi AA,, Badakhshan T,, Bettahi I,, BenMohamed L. Targeting the genital tract mucosa with a lipopeptide/recombinant adenovirus prime/boost vaccine induces potent and long-lasting CD8+ T cell immunity against herpes: importance of MyD88. J Immunol. 2012; 189: 4496–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farooq AV,, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012; 57: 448–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001; 20: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Banerjee K,, Biswas PS,, Rouse BT. Elucidating the protective and pathologic T cell species in the virus-induced corneal immunoinflammatory condition herpetic stromal keratitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2005; 77: 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dana MR,, Qian Y,, Hamrah P. Twenty-five-year panorama of corneal immunology: emerging concepts in the immunopathogenesis of microbial keratitis peripheral ulcerative keratitis, and corneal transplant rejection. Cornea. 2000; 19: 625–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas J,, Rouse BT. Immunopathogenesis of herpetic ocular disease. Immunol Res. 1997; 16: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kumaraguru U,, Davis I,, Rouse BT. Chemokines and ocular pathology caused by corneal infection with herpes simplex virus. J Neurovirol. 1999; 5: 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chentoufi AA,, Kritzer E,, Tran MV,, et al. The herpes simplex virus 1 latency-associated transcript promotes functional exhaustion of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in latently infected trigeminal ganglia: a novel immune evasion mechanism. J Virol. 2011; 85: 9127–9138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. HEDS. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339: 300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knipe DM,, Corey L,, Cohen JI,, Deal CD. Summary and recommendations from a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) workshop on “Next Generation Herpes Simplex Virus Vaccines.” Vaccine. 2014; 32: 1561–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chentoufi AA,, Binder NR,, Berka N,, et al. Asymptomatic human CD4+ cytotoxic T-cell epitopes identified from herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B. J Virol. 2008; 82: 11792–11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khan AA,, Srivastava R,, Chentoufi AA,, et al. Therapeutic immunization with a mixture of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein d derived “asymptomatic” human CD8+ T-cell epitopes decreases spontaneous ocular shedding in latently infected HLA transgenic rabbits: association with low frequency of local PD-1+TIM-3+CD8+ exhausted T cells [pubished online ahead of print April 15, 2015]. J Virol. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00788-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Chentoufi AA,, Dasgupta G,, Christensen ND,, et al. A novel HLA (HLA-A*0201) transgenic rabbit model for preclinical evaluation of human CD8+ T cell epitope-based vaccines against ocular herpes. J Immunol. 2010; 184: 2561–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu J,, Peng X,, Schell TD,, Budgeon LR,, Cladel NM,, Christensen ND. An HLA-A2.1-transgenic rabbit model to study immunity to papillomavirus infection. J Immunol. 2006; 177: 8037–8045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nesburn AB,, Burke RL,, Ghiasi H,, Slanina SM,, Wechsler SL. A therapeutic vaccine that reduces recurrent herpes simplex virus type 1 corneal disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998; 39: 1163–1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nesburn AB,, Burke RL,, Ghiasi H,, Slanina SM,, Wechsler SL. Therapeutic periocular vaccination with a subunit vaccine induces higher levels of herpes simplex virus-specific tear secretory immunoglobulin A than systemic vaccination and provides protection against recurrent spontaneous ocular shedding of virus in latently infected rabbits. Virology. 1998; 252: 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nesburn AB,, Slanina S,, Burke RL,, Ghiasi H,, Bahri S,, Wechsler SL. Local periocular vaccination protects against eye disease more effectively than systemic vaccination following primary ocular herpes simplex virus infection in rabbits. J Virol. 1998; 72: 7715–7721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nesburn AB,, Ramos TV,, Zhu X,, Asgarzadeh H,, Nguyen V,, BenMohamed L. Local and systemic B cell and Th1 responses induced following ocular mucosal delivery of multiple epitopes of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D together with cytosine-phosphate-guanine adjuvant. Vaccine. 2005; 23: 873–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang X,, Chentoufi AA,, Dasgupta G,, et al. A genital tract peptide epitope vaccine targeting TLR-2 efficiently induces local and systemic CD8+ T cells and protects against herpes simplex virus type 2 challenge. Mucosal Immunol. 2009; 2: 129–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srivastava R,, Khan AA,, Spencer D,, et al. HLA-A02:01-restricted epitopes identified from the herpes simplex virus tegument protein VP11/12 preferentially recall polyfunctional effector memory CD8+ T cells from seropositive asymptomatic individuals and protect humanized HLA-A*02:01 transgenic mice against ocular herpes. J Immunol. 2015; 194: 2232–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khan AA,, Srivastava R,, Spencer D,, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein B epitope-specific effector and memory CD8+ T cells from ocular herpes symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. J Virol. 2015; 89: 3776–3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X,, Issagholian A,, Berg EA,, Fishman JB,, Nesburn AB,, BenMohamed L. Th-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte chimeric epitopes extended by Nepsilon-palmitoyl lysines induce herpes simplex virus type 1-specific effector CD8+ Tc1 responses and protect against ocular infection. J Virol. 2005; 79: 15289–15301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chentoufi AA,, BenMohamed L. Future viral vectors for the delivery of asymptomatic herpes epitope-based immunotherapeutic vaccines. Future Virol. 2010; 5: 525–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chentoufi AA,, Kritzer E,, Yu DM,, Nesburn AB,, Benmohamed L. Towards a rational design of an asymptomatic clinical herpes vaccine: the old the new, and the unknown. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012; 2012: 187585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dasgupta G,, Chentoufi AA,, Kalantari M,, et al. Immunodominant “asymptomatic” herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 protein antigens identified by probing whole-ORFome microarrays with serum antibodies from seropositive asymptomatic versus symptomatic individuals. J Virol. 2012; 86: 4358–4369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dasgupta G,, Nesburn AB,, Wechsler SL,, BenMohamed L. Developing an asymptomatic mucosal herpes vaccine: the present and the future. Future Microbiol. 2010; 5: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dervillez X,, Gottimukkala C,, Kabbara KW,, et al. Future of an “asymptomatic” T-cell epitope-based therapeutic herpes simplex vaccine. Future Virol. 2012; 7: 371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Khan AA,, Srivastava R,, Lopes PP,, et al. Asymptomatic memory CD8+ T cells: from development and regulation to consideration for human vaccines and immunotherapeutics. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014; 10: 945–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. BenMohamed L,, Wechsler SL,, Nesburn AB. Lipopeptide vaccines--yesterday today, and tomorrow. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002; 2: 425–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Channappanavar R,, Twardy BS,, Suvas S. Blocking of PDL-1 interaction enhances primary and secondary CD8 T cell response to herpes simplex virus-1 infection. PLoS One. 2012; 7: e39757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakuishi K,, Apetoh L,, Sullivan JM,, Blazar BR,, Kuchroo VK,, Anderson AC. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 2010; 207: 2187–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jin HT,, Anderson AC,, Tan WG,, et al. Cooperation of Tim-3 and PD-1 in CD8 T-cell exhaustion during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107: 14733–14738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fourcade J,, Sun Z,, Benallaoua M,, et al. Upregulation of Tim-3 and PD-1 expression is associated with tumor antigen-specific CD8+ T cell dysfunction in melanoma patients. J Exp Med. 2010; 207: 2175–2186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chentoufi AA,, Dasgupta G,, Nesburn AB,, et al. Nasolacrimal duct closure modulates ocular mucosal and systemic CD4(+) T-cell responses induced following topical ocular or intranasal immunization. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010; 17: 342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wuest T,, Farber J,, Luster A,, Carr DJ. CD4+ T cell migration into the cornea is reduced in CXCL9 deficient but not CXCL10 deficient mice following herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Cell Immunol. 2006; 243: 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Conrady CD,, Zheng M,, Stone DU,, Carr DJ. CD8+ T cells suppress viral replication in the cornea but contribute to VEGF-C-induced lymphatic vessel genesis. J Immunol. 2012; 189: 425–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dasgupta G,, Chentoufi AA,, Nesburn AB,, Wechsler SL,, BenMohamed L. New concepts in herpes simplex virus vaccine development: notes from the battlefield. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009; 8: 1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Knickelbein JE,, Khanna KM,, Yee MB,, Baty CJ,, Kinchington PR,, Hendricks RL. Noncytotoxic lytic granule-mediated CD8+ T cell inhibition of HSV-1 reactivation from neuronal latency. Science. 2008; 322: 268–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. BenMohamed L,, Osorio N,, Srivastava R,, Khan AA,, Simpson JS,, Wechsler SL. Decreased reactivation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) latency associated transcript (LAT) mutant using the in vivo mouse UV-B model of induced reactivation [published online ahead of print May 22, 2015]. J Neurovirol. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00788-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45. Webre JM,, Hill JM,, Nolan NM,, et al. Rabbit and mouse models of HSV-1 latency, reactivation, and recurrent eye diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012; 7: 12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hill JM,, Nolan NM,, McFerrin HE,, et al. HSV-1 latent rabbits shed viral DNA into their saliva. Virol J. 2012; 9: 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nesburn AB,, Bettahi I,, Dasgupta G,, et al. Functional Foxp3+ CD4+ CD25(Bright+) “natural” regulatory T cells are abundant in rabbit conjunctiva and suppress virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells during ocular herpes infection. J Virol. 2007; 81: 7647–7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perng GC,, Osorio N,, Jiang X,, et al. Large amounts of reactivated virus in tears precedes recurrent herpes stromal keratitis in stressed rabbits latently infected with herpes simplex virus [published online ahead of print April 10, 2015]. Curr Eye Res. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02713683.2015.1020172:1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49. Dasgupta G,, BenMohamed L. Of mice and not humans: how reliable are animal models for evaluation of herpes CD8(+)-T cell-epitopes-based immunotherapeutic vaccine candidates? Vaccine. 2011; 29: 5824–5836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lekstrom-Himes JA,, Hohman P,, Warren T,, et al. Association of major histocompatibility complex determinants with the development of symptomatic and asymptomatic genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infections. J Infect Dis. 1999; 179: 1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sette A,, Livingston B,, McKinney D,, et al. The development of multi-epitope vaccines: epitope identification, vaccine design and clinical evaluation. Biologicals. 2001; 29: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sette A,, Newman M,, Livingston B,, et al. Optimizing vaccine design for cellular processing, MHC binding and TCR recognition. Tissue Antigens. 2002; 59: 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Heit A,, Schmitz F,, Haas T,, Busch DH,, Wagner H. Antigen co-encapsulated with adjuvants efficiently drive protective T-cell immunity. Eur J Immunol. 2007; 37: 2063–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fischer S,, Schlosser E,, Mueller M,, et al. Concomitant delivery of a CTL-restricted peptide antigen and CpG ODN by PLGA microparticles induces cellular immune response. J Drug Target. 2009; 17: 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schlosser E,, Mueller M,, Fischer S,, et al. TLR ligands and antigen need to be coencapsulated into the same biodegradable microsphere for the generation of potent cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. Vaccine. 2008; 26: 1626–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]