There is growing recognition that pain communication is important, and the way that people (e.g. partners, healthcare providers) respond to patients sharing their pain-related thoughts and feelings may have significant implications for pain-related outcomes[8]. One potentially important factor that has been relatively understudied until recently is the level of validation that may or may not be provided by people who are the recipients of a pain communication [4].

Many patients with chronic pain believe that others do not understand their pain or even consider their pain condition to be legitimate[9], beliefs which are likely to lead to increases in psychological distress and negative affect. It is possible that validation of pain-related thoughts and feelings for these patients may lead to reductions in negative affect. Furthermore, validation from a romantic partner may enhance relationship intimacy, which is related to several positive benefits (e.g. increased positive affect, improved psychological well-being) [10; 11]. Despite the potential benefits of validation, some research suggests that receiving social reinforcement (including validation) after sharing pain-related thoughts and feelings may be associated with worse patient outcomes such as increased pain[22].

This paper highlights studies examining the effects of validation of pain-related thoughts and feelings. It is divided into four sections. In the first section, we describe the concept of validation. The second section describes several theories that attempt to explain the impact of validation on patient outcomes (e.g. affect, report of pain intensity). In the third section, we review a number of studies examining validation and invalidation in the context of pain. In the final section of the paper, we highlight several important future directions for research on the influence of validation on chronic pain.

The concept of validation

Marsha Linehan, a key validation theorist, suggests that validation is a process in which a listener communicates that a person’s thoughts and feelings are understandable and legitimate.[12; 13] Linehan emphasizes that validating thoughts and feelings as understandable does not mean that the person validating necessarily agrees with the speaker’s perspective.[12; 13] For example, when responding to someone who has chronic pain, validation may include conveying acceptance and understanding of pain-related thoughts and feelings without encouraging potentially maladaptive behaviors (e.g. “It must be frustrating to have so much pain, I wonder how you will be able to manage your activities”). Validation, then, involves expressing that another person’s disclosure is understandable and legitimate, and conveys acceptance of that disclosure, whether or not the person communicating validation agrees with the content of that disclosure. By understandable and legitimate, we mean both that the listener hears and comprehends the content of the disclosure and that the listener conveys that given the circumstances, the content of that disclosure is reasonable and valid.

In the developing the construct of validation, Linehan describes six levels of validating behaviors that individuals (e.g. partners, friends, health professionals) may engage in (see Table 1). These six levels may be thought of as a continuum from a “low dose” of validation to a “high dose” of validation; examples are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of Validation

| Level | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| One: Listening and Observing | Listening and paying attention to the speaker. May involve making eye contact, nodding, etc. | Nodding and making eye contact with someone while they share their experience |

| Two: Accurate Reflection | Restating what the speaker has said in order to convey you have understood the content of their message. | Patient: “Compared to yesterday, I hurt a lot more today.” Validation: “So, your pain is worse today.” |

| Three: Articulating the Unverbalized | Inferring thoughts or feelings that may have been implied in the disclosure. | Patient: “I can’t get anything done – I have a pain flare every time I try to do something!” Validation: “It sounds like you are frustrated.” |

| Four: Validating in Terms of Sufficient (but Not Necessarily Valid) Causes | Validating what the speaker said is understandable given their background or history (e.g. their past experience with pain) | Patient: “I need more pain medication.” Validation: “It makes sense that you would want to take more pain medication, since that was helpful in the past.” |

| Give: Validating as Reasonable in the Moment | Validating what the speaker said is “reasonable in the moment” or justified in terms of their current situation | Patient: “I can’t keep doing this yard work.” Validation: “It makes sense that you want to take a break from the yard work, it’s difficult for you to just keep working till you complete the job when your back pain is getting worse.” |

| Six: Radical Genuineness | Treating the speaker as a valid and capable individual | Patient: “I am so worried because my pain is worse again today.” Validation: “Of course a pain flare leads you to feel anxious; a lot of people might feel that way in your shoes.” |

A valuable addition to the conceptualization of validation has been the growing emphasis placed on considering whether or not a person feels validated by a listener’s response.[10; 15] If a patient with pain feels understood and validated, it will likely influence their emotional state and their behaviors differently than if they perceive that others respond but do not understand them.

Models of validation

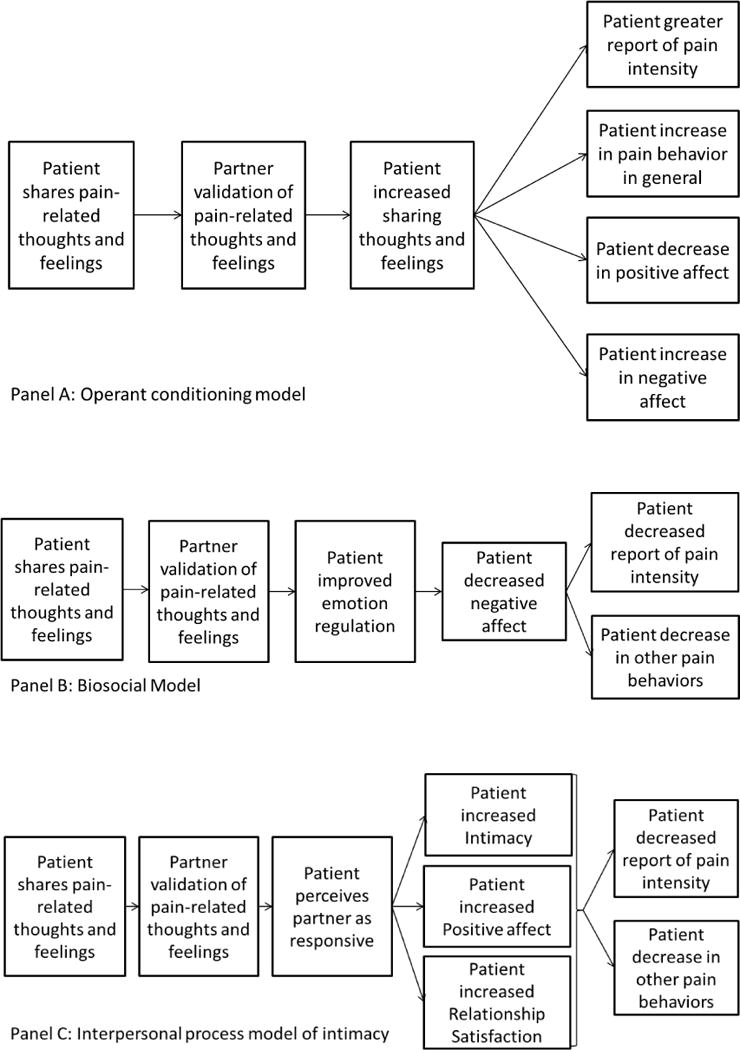

Three theoretical models can be used to predict how validation of pain-related thoughts and feelings may influence patient outcomes: the operant conditioning model, the biosocial model, and the interpersonal process model of intimacy.

The operant conditioning model[5] focuses on the role that social reinforcement plays in the development and maintenance of maladaptive and adaptive responses to persistent pain. This model views validation as a type of social reinforcement and predicts that validation increases the likelihood of whatever behavior it follows. Thus, if validation occurs after someone talks about their pain or shows other pain behaviors (see Figure 1, Panel A), then the likelihood of pain behaviors will increase. Alternatively, if validation occurs after someone discloses thoughts or feelings related to pain, this type of disclosure is likely to increase. Patients having persistent pain are likely to talk about their pain with close others, and many of these people are likely to respond with attention or assistance. The key issue is the timing of validation. Without intervention, some significant others may engage in validating behaviors right after patients provide detailed descriptions of pain without realizing that these validating behaviors have the potential to reinforce maladaptive pain behaviors such as focusing on the pain, spending excessive time reclining, or over-reliance on others for assistance.

Figure 1.

Models of Validation

According to the biosocial model[12; 13], validation has a soothing effect, reduces negative affect, and “takes the steam” out of interactions with high emotional arousal.[6] Several experimental research studies have provided support for the idea that reductions in negative affect may lead to reductions in pain[18–20; 23] According to the biosocial model, if patients receive validation after sharing pain-related thoughts and feelings, they will feel understood and accepted, will experience a reductions in emotional arousal and negative affect, and may experience a reduction in pain (see Figure 1, Panel B).

The interpersonal process model of intimacy[16; 17] views intimacy as the product of a transactional process. This model hypothesizes that intimacy is a result of interactions where one person (the speaker) shares personally relevant information and another person (the listener) responds in a way that causes the speaker to feel validated, understood and cared for, which is referred to as “perceived partner responsiveness.”[10] This model focuses on the speaker’s perception of the partner’s response in addition to the actual response of the listener. It may be especially useful when applied to patients with chronic pain interacting with close others (e.g. a spouse or partner) about their pain. The model (see Figure 1, Panel C) hypothesizes that when partners engage in validating behaviors after patients disclose pain-related thoughts and feelings, patients will report increased intimacy, positive affect, and relationship satisfaction; positive affective responses that in turn can lead to lower levels of reported pain.

These models each make predictions about the influence of validation; however, it is likely that the mechanism by which validation influences patients is more nuanced than any single model captures. What exactly is being reinforced by validating responses (e.g. emotional disclosure, verbal reports of pain) has not been well-studied, and understanding this complex process may help clarify how these models may overlap or occur simultaneously.

Empirical studies of validation

A number of studies have used the Validation and Invalidation Behavioral Coding System (VIBCS[7]) to code validation occurring in interactions between patients with chronic pain and their partners.[1–3] In these studies, romantic partners and patients were asked to discuss the pain experienced by the patient and how it has affected their lives. These conversations were videotaped and validating and invalidating behaviors of the non-patient partner subsequently coded with the VIBCS. Several key findings emerged. First, observers were able to reliably code both validating behaviors and invalidating behaviors. Second, these behaviors were found to be distinct from other spousal responses such as partner solicitousness. Third, in couples where the partner provided higher levels of validation, patients were much more likely to engage in disclosure and much less likely to report a sense of support entitlement. Finally, higher levels of validation were not related to patient reports of pain or symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Two experimental studies have explicitly tested the impact of validation and invalidation on pain-related outcomes. One study randomly assigned healthy student subjects (N=59) to receive either validation or invalidation from a research assistant while subjects participated in a pain tolerance task.[14] Results showed that over the course of the experiment, participants in the validation condition maintained their positive affect, while patients in the invalidation condition reported a decline in positive affect. Participants in the validation condition also reported a significant decrease in worry while participants in the invalidation group increased in worry. No pain rating or pain tolerance differences were found between conditions.

Another study using an experimental design was conducted with nurses (N=28) having current back pain.[21] This study manipulated verbal and non-verbal responses of validation and invalidation delivered by a research assistant a semi-structured interview about back pain. Participants who were assigned to the validation condition reported feeling less frustrated and less angry as compared to participants who received invalidation, who reported an increase in feelings of frustration and anger. Participants in the validation condition also reported greater satisfaction with the interview compared to participants in the invalidation condition. Interestingly, participants exposed to validation, as opposed to invalidation, did not report differences in post-interview pain.

These two experimental studies found changes in affect consistent with the hypotheses made by the biosocial model, while neither found changes in pain intensity over the course of the experiment. Reports of pain intensity may be considered a form of pain behavior, and the lack of change in this pain behavior does not fit with either the biosocial model or the operant conditioning model. Both of these studies have several strengths, such as their experimental designs. However, several questions are left unanswered. Neither study measured perceived validation or invalidation from the perspective of the participant; however, feeling understood and validated may be an important predictor of patient outcomes. Additionally, neither study measured aspects of the pain experience beyond pain intensity, such as non-verbal pain behaviors, pain-related disability, or interpretations about the meaning of the pain, which may be important indicators of patient outcomes. One possibility is that validation does not change the perceived intensity but enables patients to view their pain as more acceptable and less dangerous. Both of these studies also used research assistants to deliver validation/invalidation, which contributes to high internal validity but may compromise external validity. The use of a friend, partner, or someone the participant knows well would be an interesting future direction, as it is possible that validation from a close other would have a greater impact on participants. Lastly, the first study[14] used healthy participants while the second study[21] used nurses who reported back pain in past six months. Future research should determine if similar outcomes would occur with patients with chronic pain conditions.

Future directions

There are several potential future lines of research for this area. Some observational studies have coded for validation and invalidation, but currently, no studies have compared observational reports of validation with self-reported feelings of validation. Self-reported feelings of validation are a key construct in the interpersonal process model of intimacy, and future research should attempt to measure validation both via observation and self-report. It would be interesting to examine the degree to which observed validation correlates with self-reports of feeling validated and which is more predictive of patient outcomes.

Additionally, future research should expand the range of outcomes examined to look at the influence validation has on non-verbal pain behaviors, as these pain behaviors are a predictor of many other important outcomes in patients with chronic pain (e.g. physical disability and psychological distress). If validation reduces the incidence of pain behavior, teaching people who regularly interact with patients with chronic pain how to engage in validation may lead to reductions in physical disability and psychological distress in patients.

Further, additional experimental lab-based studies of validation are needed. Lab-based studies can control for a variety of factors such as type of pain and the manner in which validation/invalidation is delivered. To date, validation has only been compared to invalidation and has only been delivered by a research assistant. Future research could manipulate levels of validation (e.g. according to the six levels suggested by Linehan) or use a more neutral condition rather than only invalidation conditions as comparison groups. Including a neutral comparison condition, while desirable, may be very difficult since most interactions involve providing the patient with some indication that they are being understood or not. Thus, in experimental studies one might wish to compare a high validation condition to a low validation condition (rather than a strictly neutral condition). The source of validation can also be varied, to examine if validation from a close other (e.g. romantic partner, family member, or friend) or a medical professional influences patient outcomes differently than validation from a research assistant. It is also possible that other aspects of the relationship (e.g. gender dynamics, type of relationship, power differentials (e.g. between a provider and an uninsured patient seeking treatment), relationship satisfaction, closeness, etc.) may modulate the extent to which validation influences patient outcomes. Finally, experimental work should measure validation in a variety of patient populations in order to determine potential differences. For example, it may be the case the validation is particularly important for patient populations who often feel invalidated (e.g. patients with medically unexplained pain).

The results of these types of research studies have several important implications. If validation of pain-related thoughts and feelings is associated with positive patient outcomes, an important next step would involve developing interventions aimed at teaching others how to be validating. Interventions designed to teach family members or partners how to validate pain-related thoughts and feelings may improve family relationships and patient outcomes. Additionally, teaching healthcare providers to practice validation with patients may increase patient-physician communication and allow patients to feel more accepted and satisfied with their care.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by the following NIH grants (CA131148, AG041655, NR013910, UH2 AT00788, UM1 AR062800, AT007572, CA173307).

Reference List

- 1.Cano A, Barterian JA, Heller JB. Empathic and nonempathic interaction in chronic pain couples. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(8):678–684. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816753d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cano A, Leong L, Heller JB, Lutz JR. Perceived entitlement to pain-related support and pain catastrophizing: Associations with perceived and observed support. Pain. 2009;147(1–3):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cano A, Leong LEM, Williams AM, May DKK, Lutz JR. Correlates and consequences of the disclosure of pain-related distress to one’s spouse. Pain. 2012;147:249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cano A, Williams ACD. Social interaction in pain: Reinforcing pain behaviors or building intimacy? Pain. 2010;149:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fordyce WE. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fruzzetti A, Shenk C. Fostering validating respones in families. Social work in mental health. 2008;6(1–2):215–227. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fruzzetti AE. Validation and Invalidation Coding System. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjistravropolos T, Craig KD, Duck S, Cano A, Goubert L, Jackson PL, Mogil JS, Rainville P, Sullivan MJL, de C Williams AC, Vervoort T, Fitzgerald TD. A biopsychosocial formulation of pain communication. Psychological Bulletin. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0023876. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kool MB, van Middendorp H, Borije HR, Geenen R. Understanding the lack of understanding: Invalidating from the perspective of the patient with fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;61(12):1650–1656. doi: 10.1002/art.24922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Pietromonaco PR. Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1238–1251. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laurenceau JP, Barrett LF, Rovine MJ. The interpersonal process model of intimacy in marriage: A daily-diary and multilevel modeling approach. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(2):314–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linehan M. Validation and psychotherapy. In: Bohart A, Greenber LS, editors. Empathy reconsidered: New directions in psychotherapy. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linton SJ, Boersma K, Vangronsveld KLH, Fruzzetti AE. Painfully reassuring? The effects of validation on emotions and adherence in a pain test. European Journal of Pain. 2011;16:592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reis HT. The role of initmacy in interpersonal relationships. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9(1):15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reis HT, Patrick BC. Attachment and intimacy: Component processes. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reis HT, Shaver P. Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In: Duck S, editor. Handbook of personal relationships. Chicester: Wiley; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. The role of emotion in pain modulation. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2001;14:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhudy JL, Williams AM, McCabe KM, Russell JL, Maynard LJ. Emotional control of nociceptive reactions (ECON): Do affective valence and arousal play a role? Pain. 2008;136:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy M, Lebuis A, Peretz I, Rainville P. The modulation of pain by attention and emotion: A dissociation of perceptual and spinal nociceptive processes. European Journal of Pain. 2011;15 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vangronsveld KLH, Linton SJ. The effect of validating and invalidating communication on satisfaction, pain and affect in nurses suffering from low back pain during a semi-structured interview. European Journal of Pain. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.07.009. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White B, Sanders SH. The influence on patients’ pain intensity ratings of antecedent reinforcement of pain talk or well talk. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1986;17(3):155–159. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(86)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zelman DC, Howland EW, Nichols SN, Cleeland CS. The effects of induced mood on laboratory pain. Pain. 1991;46(1):105–111. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]