Abstract

Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) are a class of biologically important molecules and their structural analysis is the target of considerable research effort. Advances in tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) have recently enabled the structural characterization of several classes of GAGs. However, the highly sulfated GAGs, such as heparins, have remained a relatively intractable class due their tendency to lose SO3 during MS/MS producing few sequence-informative fragment ions. The present work demonstrates for the first time the complete structural characterization of the highly sulfated heparin-based drug, Arixtra. This was achieved by Na+/H+ exchange, to create a more ionized species that was stable against SO3 loss, and that produced complete sets of both glycosidic and cross-ring fragment ions. MS/MS, enabling the complete structural determination of Arixtra®, including the stereochemistry of its uronic acid residues and suggests an approach for solving the structure of more complex, highly sulfated heparin-based drugs.

Heparin (Hp) and structurally related heparan sulfate (HS) are biopolymers comprised of highly sulfated uronic acid and glucosamine repeating units and are found intracellularly, in the extracellular matrix, and on the cell surface of a wide variety of species.1,2 To develop a deeper understanding of their biological function in angiogenesis3, tumor metastasis4, viral invasion5, cell growth and proliferation6 and anticoagulation,7 elucidation of their molecular level structures is of great interest but remains a challenge.8 Unlike biopolymers such as proteins or nucleic acids, the biosynthetic pathways for GAGs are not based on a template mechanism, with the result that they are heterogeneous in composition, and highly polydisperse in molecular weight.9,10 While Hp is produced in large amounts as a drug, HS is often extracted from tissues in small quantities requiring sensitive analytical methods, such as MS.9 Negative mode electrospray ionization (ESI) is commonly used due to the highly acidic nature of Hp and HS11 and it provides the multiply charged precursor ions required for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

The presence of a high number of labile sulfate groups renders most of the MS/MS techniques insufficient for the structural characterization of Hp and HS.12 Previously, methods such as collision induced dissociation (CID) and infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) were found to lead to sulfate decomposition (loss of SO3) and to provide few, if any, sequence-informative cleavages.10,11,13 EDD and other electron based methods have been used to characterize HS oligosaccharides with a low level of sulfation as well as chondroitin sulfate GAGs,14–16 but these methods become less efficient as the number of sulfo groups per disaccharide increases.

Research on MS/MS methods for Hp analysis has been directed at the retention of labile sulfate groups during ion activation but with limited success. Increasing the charge state to a level where all the sulfate groups are ionized reduces sulfate loss and increases structurally-informative cleavages,13,17,18 but as the number of sulfate groups per disaccharide increases, charge-charge repulsion limits the ability to produce molecular ions with higher charge states with sufficient intensities for MS/MS.10,19 Even when the right charge state is fragmented, most of the cleavages obtained are glycosidic bond cleavages which cannot be used for locating the position of the sulfate groups within a monosaccharide unit. Multistage CID (MSn) has provided structural information on these molecules but requires substantial amounts of sample and still is inefficient in Hp oligosaccharides having more than one sulfo group per disaccharide unit.13

Exchanging H+ with metal cations such as Na+ or Ca2+ has been show to stabilize sulfate groups and to increase the formation of sequence-informative fragment ions,13,20 but these previous studies showed few glycosidic and cross-ring cleavages and failed to provide comprehensive structural identification of analytes.13 Here we show that use of NaOH as a component of electrospray (ESI) enables the production of a precursor in which all ionizable protons are removed or replaced by Na+. This precursor is found to be uniquely suitable for MS/MS analysis, and leads to the production of abundant glycosidic and cross-ring fragments, enabling full characterization of a highly sulfated synthetic Hp oligosaccharide using a single CID spectrum.

A Bruker 9.4 T FTICR (Billerica, MA, USA) with an Apollo II duo source or a Thermo Scientific LTQ Orbitrap XL FT mass spectrometer with a standard, factory-installed nanospray ion source (San Jose, CA, USA) was used in these experiments. Arixtra was purchased from the hospital formulary and desalted on a BioGel P2 column BioRad (Hercules, CA, USA). Arixtra® (1.3 μM) in 50:50 methanol: water with 1.0 mM NaOH was used for analysis. Negative mode ESI was used to ionize the sample and argon was used as the collision gas. For MS/MS by FTICR, precursor ions were mass selected by a quadruople mass filter, and then accumulated for 2–3 seconds in a hexapole collision cell with concurrent CID. 24 spectra were acquired and signal averaged for each tandem mass spectrum. In this manner, the CID spectra for different charge states with different degree of sodiation were acquired and compared. Confidently assigned glycosidic bonds were used for internal calibration giving mass accuracy of less than 1 ppm and only peaks with S/N ratio > 10 are reported. Peaks were assigned from their accurate mass values using the software package Glycoworkbench.21 All product ions are annotated using Wolff-Amster annotation22 a modification of the Domon and Costello nomenclature.23

Arixtra® is a synthetic ultralow molecular weight heparin based on the pentasaccharide sequence that comprises the antithrombin III binding site present in both Hp and HS that is responsible for anticoagulant activity.24 Arrangement of the monosaccharide units, the position of the sulfo group substitution, and the stereochemistry of the uronic acid within this pentasaccharide are critical for its anticoagulant activity.25,26 Arixtra® [C31H53O49S8N3] has 8 sulfo groups and three carboxyl groups for a total of 10 acidic sites. Higher charge states lead to less sulfate loss13,17 but charge-charge repulsion limits the ability to achieve a charge state in which all the sulfo groups are deprotonated.

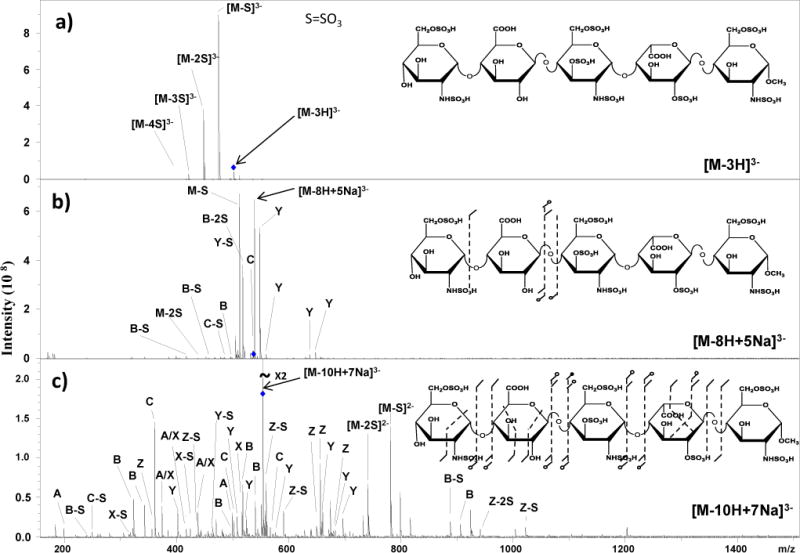

The most abundant charge state observed in the mass spectrum of Arixtra® was [M-3H]3− (supporting information). In this case only three sulfo groups were deprotonated, leaving the remaining 7 acidic groups protonated. Mild CID activation of this molecular ion produces very intense SO3 loss peaks, as shown in Figure 1a. As previously reported,13 increasing the deprotonation of sulfo and carboxyl groups through metal cation/H+ exchange reduces SO3 loss and affords structurally-informative cleavages. In Figure 1b, Na+/H+ exchange leads to de-protonation of 8 acidic groups, [M-8H+5Na]3+, which equals the number of sulfo groups in Arixtra®. While the most intense peaks in the resulting spectrum are the SO3 loss peaks, a few glycosidic fragments are observed that provide limited structural information. When all the acidic groups were deprotonated, a CID spectrum for [M-10H+7Na]3− was obtained, which had a uniform distribution of both glycosidic, cross-ring cleavages with few low intensity peaks resulting from neutral SO3 loss (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

CID spectra for triply deprotonated molecular ions of Arixtra®. a) CID of [M-3H]3− showing that a low charge state leads to the loss of SO3 and little useful structural information. b) Deprotonation of eight acidic groups, equal to the number of sulfo groups, through Na+/H+ exchange and charging, reduces SO3 loss but provides few useful fragments. c) When all ten acidic groups are deprotonated, a large number of structurally informative glycosidic and cross-ring cleavages are observed.

Due to the high density of assignable peaks within this spectrum, a simple annotation is used that does not include the entire ion nomenclature. In this annotation, A is used to denote any cleavage corresponding to the actual A fragment while A-S is used to denote loss of SO3 from the corresponding A fragment. A complete peak list is included in the supporting information (S1).

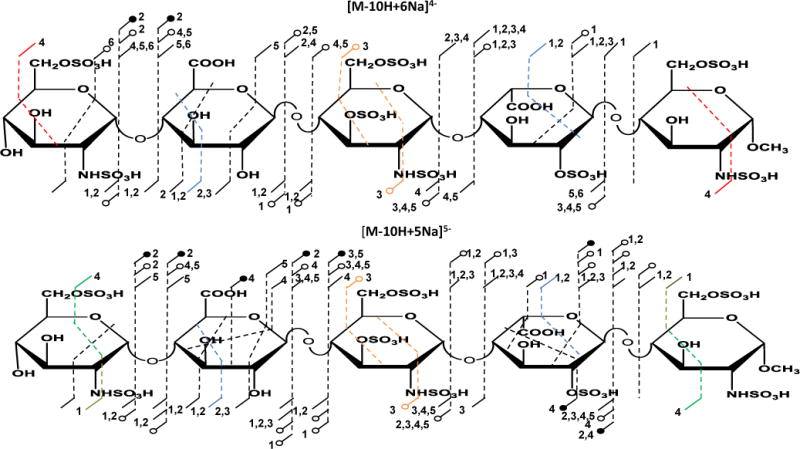

Higher charge states of the fully deprotonated sample were examined and found to give complementary data. Annotated structures for [M-10H+6Na]4− and [M-10H+5Na]5− show the observed fragmentations, which include an entire set of glycosidic bond cleavages and abundant cross-ring cleavages (Figure 2). For the molecular ion [M-10H+6Na]4−, Z1 places two sulfo groups on the reducing end residue, and the mass difference between 0,2X1 and Y1 places a sulfo group at the 2-position of the iduronic acid residue.

Figure 2.

Annotated structures showing observed cleavages for Arixtra for two different charge states and levels of sodiation. Both [M-10H+6Na]4− and [M-10H+5Na]5− show similar fragmentation patterns affording more comprehensive structural information. The numbers adjacent to a cleavage indicate the number of sodium ions present in the fragment ion, open circles denote SO3 loss accompanying the indicated fragmentation, and filled circles denote loss of 2 or more SO3 groups. Colored lines indicate isobaric cleavages, for example 2,4X4 and 1,5A4, shown in red, have the same elemental composition, and are indistinguishable by mass measurement.

The mass difference between B3 and C2 show there are three sulfo groups in the central glucosamine residue occupying all available sites of modification, i.e., 2-N-sulfo, 3-O-sulfo and 6-O-sulfo. The mass difference between Y4 and the 2,4X4 cleavage in the non-reducing end residue establishes sulfation on the 6-O- and 2-N-positions. The 2,4X4 fragment is isobaric with a 1,5A5 fragment, but 1,5 cleavage is unusual in the CID mass spectra of GAGs, while 2,4 cleavage is fairly common.

Fragmentation of another fully deprotonated molecular ion of one higher charge state [M-10H+5Na]5− (Figure 2) produces similar cleavages to those observed for [M-10H+6Na]4− with additional fragments including 2,4A5 that allow for the placement of the two sulfo groups on the 2-N and 6-O positions in the reducing end residue. The 2,4A5 fragment is isobaric with a 1,5X4 cleavage, but again, the former is common and abundant in CID spectra of GAGs, and can be confidently assigned as such. A full mass list can be found in the supporting information.

The effectiveness of this method using FTMS Orbitrap provided similar results, indicating that this approach can be applied using a wide variety of FT mass spectrometers. Moreover, the Orbitrap can afford additional low mass fragments such as 0,3X0, 3,5X0, 0,3A0, 0,4A1, and 1,3A1, ions using a high collision dissociation (HCD) fragmentation approach (supporting information).

An increase in SO3 loss fragments is observed in the spectra as the charge state increases and the number of the sodium cations in the molecular ion decreases. This suggests that stabilizing the sulfo groups is more readily achieved by increasing the degree of sodiation of the molecular ion rather than by increasing the molecular ion charge.

Uronic acid C5-stereochemistry (glucuronic acid/ iduronic acid) is another important aspect of the Arixtra® structure that determines how it interacts antithrombin III and other proteins to influences their functions.24,27 Efforts to distinguish iduronic acid and glucuronic acid in Hp, HS and dermatan sulfate analytes is an ongoing challenge15,28,29 for analytical chemists. In the attempt to determine whether the abundant cross-ring cleavages generated by CID can aid in elucidating uronic acid stereochemistry, we examined the cross-ring cleavages all of the uronic acid residues in a variety of GAG samples (chondroitin 4-sulfate, dermatan sulfate) dp4-dp10, Hp oligosaccharides dp4-dp8, and chemoenzymatically synthesized Hp (dp7) and HS dp10-dp12) oligosaccharides. These results will be a subject of a future publication, which establishes the diagnostic nature of 2,4An ions in characterizing uronic acid stereochemistry.

In all experiments, 2,4An (where n is the uronic acid residue position in the analyte) cleavage(s) appeared in all glucuronic acid residues but is absent (or present at very low intensity) in iduronic acid residues as long as all the acidic groups in the ion are deprotonated. In Arixtra®, a 2,4A2 fragment appears in the glucuronic acid residue but not in the iduronic acid residue. Although 2,4A2 fragment is isobaric with 1,5X1 fragments, H/D exchange experiments confirmed the assignment of the 2,4A2 fragment (supporting information).

Unlike the previously reported Q-TOF mass spectral data on Arixtra®,13 our study fully assigns all the fragments required for the complete establishment of primary structure. Additional studies are underway in the investigators’ laboratories on longer oligosaccharides and even full-length Hp and HS chains to establish the effectiveness of this method on larger highly sulfated GAGs.

It is interesting to compare this approach to prior efforts on GAGs and other polyanionic biomolecules such as nucleic acids. Molecules with multiple acidic sites have a high propensity to pair with metal ions, which adversely impacts mass spectrometric analysis, by introducing heterogeneity from incomplete replacement of the ionizable protons by metal ions. For this reason, researchers usually take great care to rigorously desalt anionic samples prior to MS analysis.30–32 During the ESI experiments, reagents such as formic acid or ammonium hydroxide have been used to reduce metal/proton exchange and the consequential splitting of peaks that reduces the efficiency of both MS and MS/MS analysis.17,32 In contrast to the standard approach for anionic biomolecules, the current work purposely introduces metal ions to exhaustively replace ionizable protons, which greatly improves the MS/MS analysis.

Prior investigations of the MS/MS behavior of highly sulfated GAGs have had limited success because they did not investigate the appropriate precursor species. When more than a single protonated acidic group remains in a precursor ion, MS/MS fragmentation is generally accompanied by the loss of SO3. Since sulfo group loss effectively competes with glycosidic and through-ring cleavage, this results in a loss of sequence-informative fragmentation. In conclusion, MS/MS analysis can provide complete sequence coverage for highly sulfated GAG oligosaccharides if the precursor molecular ion has all, or all but one, of its acidic groups deprotonated through a combination of charging and Na+/H+ exchange.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

National Institutes of Health Grant GM38060 is gratefully acknowledged for supporting this work.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FTICR

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry

- GAGs

glycosaminoglycans

- Hp

heparin

- HS

heparin sulfate

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional FTICR tandem mass spectra, Orbitrap data, isotope labeling results, and mass-intensity tables. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

JACS Authors note: Authors are required to submit a graphic entry for the Table of Contents (TOC) that, in conjunction with the manuscript title, should give the reader a representative idea of one of the following: A key structure, reaction, equation, concept, or theorem, etc., that is discussed in the manuscript. The TOC graphic may be no wider than 9.0 cm and no taller than 3.5 cm as the graphic will be reproduced at 100% of the submission size. A surrounding margin will be added to this width and height during Journal production.

References

- 1.Blackhall FH, Merry CL, Davies EJ, Jayson GC. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1094. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kjellen L, Lindahl U. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:341. doi: 10.1172/JCI13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu D, Shriver Z, Qi Y, Venkataraman G, Sasisekharan R. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2002;28:67. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-20565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilgard P, Stockert R. Hepatology. 2000;32:1069. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.18713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashiyama S, Abraham JA, Klagsbrun M. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:933. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabenstein DL. Natural Product Reports. 2002;19:312. doi: 10.1039/b100916h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thanawiroon C, Rice KG, Toida T, Linhardt RJ. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capila I, Gunay NS, Shriver Z, Venkataraman G. In: Chemistry and Biology of Heparin and Heparan Sulfate. Hari GG, Robert JL, Charles AH, editors. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 2005. p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi L, Amster J, Linhardt RJ. Current Anal Chem. 2005;1:223. doi: 10.2174/157341105774573929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naggar EF, Costello CE, Zaia J. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1534. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CJ, Beni S, Limtiaco JFK, Langeslay DJ, Larive CK. Ann Rev Anal Chem. 2011;4:439. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-061010-113911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaia J, Costello CE. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2445. doi: 10.1021/ac0263418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff JJ, Amster IJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2007;18:234. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff JJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2015. doi: 10.1021/ac061636x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolff JJ, Leach FE, Laremore TN, Kaplan DA, Easterling ML, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3460. doi: 10.1021/ac100554a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Busch AM, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:790. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClellan JE, Costello CE, O’Conno PB, Zaia J. Anal Chem. 2002;74:3760. doi: 10.1021/ac025506+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saad OM, Leary JA. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2985. doi: 10.1021/ac0340455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor CJ, Burke RM, Wu B, Panja S, Nielsen SB, Dessent CEH. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2009;285:70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tissot Brr, Ceroni A, Powell AK, Morris HR, Yates EA, Turnbull JE, Gallagher JT, Dell A, Haslam SM. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9204. doi: 10.1021/ac8013753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Busch AM, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:294. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Domon B, Costello CE. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:397. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petitou M, van Boeckel CAA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3118. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg RD, Lam L. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1979;76:1218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noti C, Seeberger PH. Chemistry & Biology. 2005;12:731. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuberan B, Lech MZ, Beeler DL, Wu ZL, Rosenberg RD. Nat Biotech. 2003;21:1343. doi: 10.1038/nbt885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaia J, Li X, Chan S, Costello C. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:1270. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hitchcock AM, Costello CE, Zaia J. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2350. doi: 10.1021/bi052100t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilar M, Belenky A, Wang BH. J Chromatogr A. 2001;921:3. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)00833-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fountain KJ, Gilar M, Gebler JC. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:1295. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laremore TN, Leach FE, Iii, Solakyildirim K, Amster IJ, Linhardt RJ. In: Methods Enzymol. Minoru F, editor. Vol. 478. Academic Press; 2010. p. 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.