Abstract

Cyclic amines such as pyrrolidine and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline undergo redox-annulations with α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones. Carboxylic acid promoted generation of a conjugated azomethine ylide is followed by 6π-electrocylization, and, in some cases, tautomerization. The resulting ring-fused pyrrolines are readily oxidized to the corresponding pyrroles or reduced to pyrrolidines.

Electrocyclic ring-closures of conjugated azomethine ylides enable efficient access to 5- and 7-membered azacycles.1,2 A number of mechanistically distinct methods for the generation of the required dipolar intermediates have been developed, the most common of which involve decarboxylation or the deprotonation of a preformed iminium salt.1,2 In contrast, the direct generation of conjugated azomethine ylides via redox-neutral amine α-C–H functionalization3,4 as an avenue for 1,5- and 1,7-electrocyclizations has been explored to only a limited extent.1 Previous examples include the reaction of enamines or related compounds with dimethyl acetylenedicarboxylate (DMAD) (e.g., eq 1)5 or intramolecular rearrangements of dienamines bearing multiple electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., eq 2).6 Oxidative C–H functionalization methods for the generation of conjugated azomethine ylides have also emerged.7–9 Here we report a carboxylic acid facilitated method for the in situ generation of conjugated azomethine ylides and their subsequent 1,5-electrocyclizations. Simple cyclic amines such as pyrrolidine or 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes/ketones serve as the starting materials in these cascade reactions (eq 3).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

Our group has recently advanced a general amine α-C–H bond functionalization concept to access reactive azomethine ylide intermediates via the condensation of a secondary amine with an aldehyde or a ketone.3u, 10 This enabled the development of a range of new reactions in which azomethine ylides are transformed in non-pericyclic ways.11,12 Carboxylic acids were found to be essential additives in many of these processes as they substantially lower the barriers for azomethine ylide formation. In addition, carboxylic acids serve to readily protonate azomethine ylides to form iminium ions or related N,O-acetal intermediates that undergo further transformations. Thus, the presence of a carboxylic acid, while required to access azomethine ylides, appears to be incompatible with well-established pericyclic azomethine ylide chemistry. However, we could recently show that azomethine ylides, accessed via a benzoic acid catalyzed process, readily undergo intramolecular [3+2]-cycloadditions.13 To test whether this strategy is compatible with other types of pericyclic reactions, we decided to explore 1,5-electrocyclizations using pyrrolidine and chalcone as model substrates.

As summarized in Table 1, reactions between pyrrolidine and chalcone proceeded under a range of conditions. No formation of 1a was observed in the absence of a carboxylic acid additive (entry 1). Instead, analysis of the crude reaction mixture by 1H-NMR indicated the presence of the conjugate addition product (not shown) in addition to unmodified chalcone.14 Addition of benzoic acid (0.5 equiv) under otherwise identical conditions led to the formation of 1a as a single diastereomer in 65% yield (entry 2). The presence of molecular sieves was not essential, but slightly diminished yields were obtained in their absence (entry 3). Improved results were obtained upon lowering the reaction molarity from 0.25 M to 0.1 M (entry 4). Carboxylic acid additives other than benzoic acid were less effective (entries 5–7). While a reduction in benzoic acid loading was tolerated (entry 8), the best results were obtained with one equivalent of this additive (entry 9). Solvents other than toluene were explored briefly but provided inferior results (entries 10, 11). Finally, while the amount of pyrrolidine could be reduced, this led to longer reaction times and slightly diminished yields (entries 12, 13).

Table 1.

Evaluation of Reaction Conditions.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | X | solvent (M) | additive (equiv) | time [h] | yield (%) |

| 1 | 5 | PhMe (0.25) | - | 15 | trace |

| 2 | 5 | PhMe (0.25) | BzOH (0.5) | 5 | 65 |

| 3a | 5 | PhMe (0.25) | BzOH (0.5) | 5 | 58 |

| 4 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | BzOH (0.5) | 5 | 74 |

| 5 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | AcOH (0.5) | 5 | 65 |

| 6 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | 2-EHA (0.5) | 5 | 69 |

| 7 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | HCO2H (0.5) | 5 | trace |

| 8 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | BzOH (0.2) | 6 | 68 |

| 9 | 5 | PhMe (0.1) | BzOH (1.0) | 3 | 77 |

| 10 | 5 | n-BuOH (0.1) | BzOH (1.0) | 5 | 23 |

| 11 | 5 | 1,2-DCE (0.1) | BzOH (1.0) | 12 | trace |

| 12 | 3 | PhMe (0.1) | BzOH (1.0) | 3 | 62 |

| 13 | 2 | PhMe (0.1) | BzOH (1.0) | 15 | 64 |

Without molecular sieves. 2-EHA = 2-ethylhexanoic acid.

|

(4) |

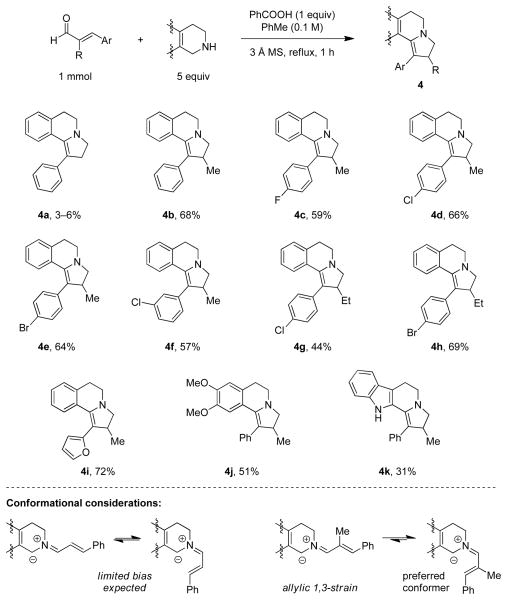

A range of diversely substituted chalcones readily underwent reactions with pyrrolidine under the optimized conditions, providing the corresponding pyrrolizidine-type annulation products in moderate to good yields (Scheme 1).15 Substitution of either of chalcone’s phenyl groups for a methyl substituent was not tolerated; no 1,5-electrocyclization products could be isolated. Similarly, reactions of pyrrolidine with cinnamaldehyde or α-methyl-cinnamaldehyde led to complex reaction mixtures and no appreciable formation of the desired annulation products. The scope of the reaction was easily extended to THIQ’s (eq 4). However, the expected products 3 were not observed. Rather, tautomeric products 2 were obtained, indicating that isomerization to the thermodynamically more stable enamines is rapid under the reaction conditions.

Scheme 1.

Scope of the reaction with pyrrolidine.

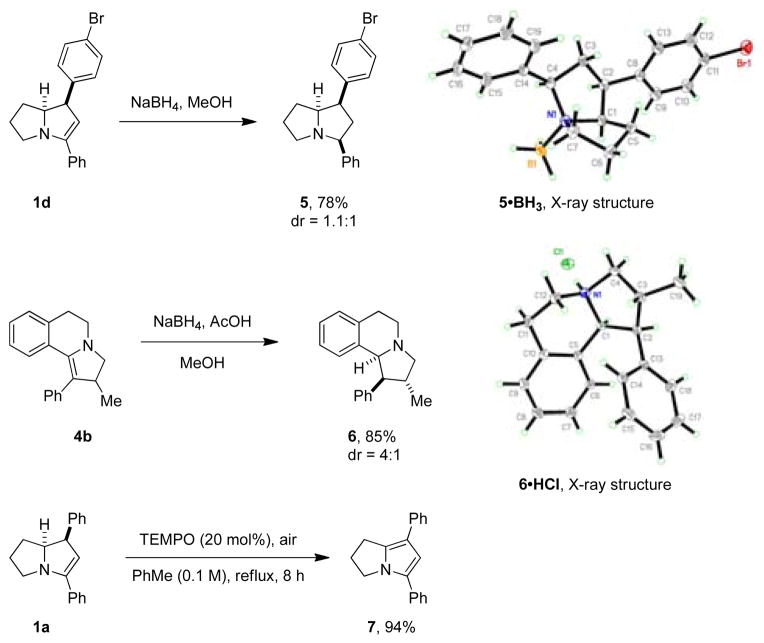

In contrast to pyrrolidine, THIQ’s and tryptoline readily underwent annulation reactions with cinnamaldehydes (Scheme 2). Parent cinnamaldehyde itself was a poor substrate, resulting in complex product mixtures out of which product 4a could be isolated in only 3–6% yield. However, α-substituted cinnamaldehydes gave rise to fast reactions and moderate to good yields of annulation products. This is consistent with what would be expected based on a simple conformational analysis. The presence of an α-substituent should result in an increased amount of the requisite conformer for the 6π-electrocyclization, as this avoids an unfavorable allylic 1,3-interaction present in the non-productive conformer (Scheme 2).16 The amine annulation products could be reduced to the corresponding pyrrolidine ring-systems (Scheme 3). Reduction of 1d with sodium borohydride led to the formation of 5 as a nearly 1:1 mixture of readily separable diastereomers. The BH3 complex of the major diastereomer, which was found to be stable to chromatographic purification, was analyzed by X-ray crystallography. A moderately selective reduction was achieved with 4b, allowing for the isolation of 6 in a 4:1 ratio of easily separable diastereomers. X-ray quality crystals of the HCl salt of the major diastereomer could be obtained which served to establish its relative configuration. Finally, 1a could be readily oxidized to ring-fused pyrrole 7 under aerobic conditions.17

Scheme 2.

Scope of the reaction with cinnamaldehydes.

Scheme 3.

Product transformation.

In summary, we have developed a simple method for the redox-neutral C–H annulation of amines with α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones, providing easy access to alkaloid-like structures from simple starting materials. This study further establishes that the generation of azomethine ylides via a carboxylic acid promoted process is compatible with the subsequent pericyclic transformation of these dipolar species. This concept, which was applied here for the first time to 6π-electrocyclizations, is expected to find widespread use in related transformations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH–NIGMS (R01GM101389) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Dr. Tom Emge (Rutgers University) for crystallographic analysis.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures and characterization data. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Selected reviews on azomethine ylide electrocyclizations: Pinho e Melo TMVD. Eur J Org Chem. 2006:2873.Nyerges M, Toth J, Groundwater PW. Synlett. 2008:1269.Anac O, Gungor FS. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:5931.

- 2.Other selected reviews on azomethine ylides: Padwa A. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. 1. Wiley; New York, N. Y: 1984. Padwa A, editor. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. 2. Wiley; New York, N. Y: 1984. Gothelf KV, Jorgensen KA. Chem Rev. 1998;98:863. doi: 10.1021/cr970324e.Padwa A, Pearson WH. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry Toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. Wiley; Chichester, U. K: 2002. Najera C, Sansano JM. Curr Org Chem. 2003;7:1105.Coldham I, Hufton R. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2765. doi: 10.1021/cr040004c.Pandey G, Banerjee P, Gadre SR. Chem Rev. 2006;106:4484. doi: 10.1021/cr050011g.Bonin M, Chauveau A, Micouin L. Synlett. 2006:2349.Nair V, Suja TD. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:12247.Stanley LM, Sibi MP. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2887. doi: 10.1021/cr078371m.Najera C, Sansano JM. Top Heterocycl Chem. 2008;12:117.Pineiro M, Pinho e Melo TMVD. Eur J Org Chem. 2009:5287.Burrell AJM, Coldham I. Curr Org Synth. 2010;7:312.Adrio J, Carretero JC. Chem Commun. 2011;47:6784. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10779h.

- 3.Selected reviews on amine C–H functionalization, including redox-neutral approaches: Murahashi SI. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:2443.Matyus P, Elias O, Tapolcsanyi P, Polonka-Balint A, Halasz-Dajka B. Synthesis. 2006:2625.Campos KR. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a.Murahashi SI, Zhang D. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:1490. doi: 10.1039/b706709g.Li CJ. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:335. doi: 10.1021/ar800164n.Jazzar R, Hitce J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374.Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d.Pan SC. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2012;8:1374. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.8.159.Mitchell EA, Peschiulli A, Lefevre N, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:10092. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201539.Zhang C, Tang C, Jiao N. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3464. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15323h.Jones KM, Klussmann M. Synlett. 2012;23:159.Peng B, Maulide N. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:13274. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301522.Platonova AY, Glukhareva TV, Zimovets OA, Morzherin YY. Chem Heterocycl Compd. 2013;49:357.Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC. Chem Rev. 2013;113:5322. doi: 10.1021/cr300503r.Girard SA, Knauber T, Li CJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:74. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304268.Haibach MC, Seidel D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:5010. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306489.Wang L, Xiao J. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:1137.Vo CVT, Bode JW. J Org Chem. 2014;79:2809. doi: 10.1021/jo5001252.Seidel D. Org Chem Front. 2014;1:426. doi: 10.1039/C4QO00022F.Qin Y, Lv J, Luo S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:551.Seidel D. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:317. doi: 10.1021/ar5003768.

- 4.Selected reviews on other types of redox-neutral transformations: Burns NZ, Baran PS, Hoffmann RW. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:2854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806086.Ketcham JM, Shin I, Montgomery TP, Krische MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:9142. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403873.Mahatthananchai J, Bode JW. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:696. doi: 10.1021/ar400239v.Huang H, Ji X, Wu W, Jiang H. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:1155. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00288a.

- 5.(a) Reinhoudt DN, Trompenaars WP, Geevers J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976;17:4777. [Google Scholar]; (b) Reinhoudt DN, Geevers J, Trompenaars WP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:1351. [Google Scholar]; (c) Verboom W, Visser GW, Trompenaars WP, Reinhoudt DN, Harkema S, van Hummel GJ. Tetrahedron. 1981;37:3525. [Google Scholar]; (d) Jiang S, Janousek Z, Viehe HG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994;35:1185. [Google Scholar]; (e) De Boeck B, Jiang S, Janousek Z, Viehe HG. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:7075. [Google Scholar]; (f) Bhuyan PJ, Sandhu JS, Ghosh AC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:1853. [Google Scholar]; (g) De Boeck B, Viehe HG. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:513. [Google Scholar]; (h) Vvedensky VY, Ivanov YV, Kysil V, Williams C, Tkachenko S, Kiselyov A, Khvat AV, Ivachtchenko AV. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:3953. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Reinhoudt DN, Visser GW, Verboom W, Benders PH, Pennings MLM. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:4775. [Google Scholar]; (b) Orlemans EOM, Lammerink BHM, Van Veggel FCJM, Verboom W, Harkema S, Reinhoudt DN. J Org Chem. 1988;53:2278. [Google Scholar]; (c) Bianchi L, MacCagno M, Petrillo G, Scapolla C, Tavani C, Tirocco A. Eur J Org Chem. 2014;2014:39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Grigg R, Myers P, Somasunderam A, Sridharan V. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:9735. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yadav AK, Yadav LDS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:686. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Examples of reactions in which a 1,5-electrocyclization is followed by the formation of a fused pyrrole ring: Grigg R, Nimal Gunaratne HQ, Henderson D, Sridharan V. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:1599.Soeder RW, Bowers K, Pegram LD, Cartaya-Marin CP. Synth Commun. 1992;22:2737.Grigg R, Kennewell P, Savic V, Sridharan V. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:10423.Deb I, Seidel D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2945.

- 9.Amine C–H functionalization in the context of 1,7-electrocyclizations, selected examples: Mayer T, Maas G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:205.Reinhard R, Glaser M, Neumann R, Maas G. J Org Chem. 1997;62:7744.Reisser M, Maas G. J Org Chem. 2004;69:4913. doi: 10.1021/jo049586o.Tóth J, Dancsó A, Blaskó G, Tőke L, Groundwater PW, Nyerges M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:5725.Yin G, Zhu Y, Lu P, Wang Y. J Org Chem. 2011;76:8922. doi: 10.1021/jo2016407.

- 10.Selected examples from our lab: Zhang C, De CK, Mal R, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:416. doi: 10.1021/ja077473r.Zhang C, Das D, Seidel D. Chem Sci. 2011;2:233.Deb I, Das D, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2011;13:812. doi: 10.1021/ol1031359.Ma L, Chen W, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:15305. doi: 10.1021/ja308009g.Das D, Sun AX, Seidel D. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:3765. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300021.Das D, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2013;15:4358. doi: 10.1021/ol401858k.Dieckmann A, Richers MT, Platonova AY, Zhang C, Seidel D, Houk KN. J Org Chem. 2013;78:4132. doi: 10.1021/jo400483h.Chen W, Wilde RG, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2014;16:730. doi: 10.1021/ol403431u.Richers MT, Breugst M, Platonova AY, Ullrich A, Dieckmann A, Houk KN, Seidel D. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:6123. doi: 10.1021/ja501988b.Chen W, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2014;16:3158. doi: 10.1021/ol501365j.Jarvis CL, Richers MT, Breugst M, Houk KN, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2014:3556. doi: 10.1021/ol501509b.

- 11.Related studies by others, examples: Poirier RH, Morin RD, McKim AM, Bearse AE. J Org Chem. 1961;26:4275.Burrows WD, Burrows EP. J Org Chem. 1963;28:1180.Oda M, Fukuchi Y, Ito S, Thanh NC, Kuroda S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:9159.Zheng L, Yang F, Dang Q, Bai X. Org Lett. 2008;10:889. doi: 10.1021/ol703049j.Pahadi NK, Paley M, Jana R, Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16626. doi: 10.1021/ja907357g.Mao H, Xu R, Wan J, Jiang Z, Sun C, Pan Y. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:13352. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001896.Xue X, Yu A, Cai Y, Cheng JP. Org Lett. 2011;13:6054. doi: 10.1021/ol2025247.Zheng QH, Meng W, Jiang GJ, Yu ZX. Org Lett. 2013;15:5928. doi: 10.1021/ol402517e.Lin W, Cao T, Fan W, Han Y, Kuang J, Luo H, Miao B, Tang X, Yu Q, Yuan W, Zhang J, Zhu C, Ma S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:277. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308699.Haldar S, Mahato S, Jana CK. Asian J Org Chem. 2014;3:44.Rahman M, Bagdi AK, Mishra S, Hajra A. Chem Commun. 2014;50:2951. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00454j.Ramakumar K, Tunge JA. Chem Commun. 2014;50:13056. doi: 10.1039/c4cc06369d.Li J, Wang H, Sun J, Yang Y, Liu L. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:2523. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42431f.Lin W, Ma S. Org Chem Front. 2014;1:338.Mahato S, Haque MA, Dwari S, Jana CK. RSC Adv. 2014;4:46214.

- 12.Other recent examples of redox-neutral amine α-C–H functionalization: Jurberg ID, Peng B, Woestefeld E, Wasserloos M, Maulide N. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:1950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108639.Chen L, Zhang L, Lv J, Cheng JP, Luo S. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:8891. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201532.Sugiishi T, Nakamura H. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2504. doi: 10.1021/ja211092q.Han YY, Han WY, Hou X, Zhang XM, Yuan WC. Org Lett. 2012;14:4054. doi: 10.1021/ol301559k.He YP, Wu H, Chen DF, Yu J, Gong LZ. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:5232. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300052.Kang YK, Kim DY. Chem Commun. 2014;50:222. doi: 10.1039/c3cc46710d.Mori K, Kurihara K, Akiyama T. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3729. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00894d.Mori K, Kurihara K, Yabe S, Yamanaka M, Akiyama T. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3744. doi: 10.1021/ja412706d.Cao W, Liu X, Guo J, Lin L, Feng X. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:1632. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404327.Wang PF, Jiang CH, Wen X, Xu QL, Sun H. J Org Chem. 2015;80:1155. doi: 10.1021/jo5026817.

- 13.Mantelingu K, Lin Y, Seidel D. Org Lett. 2014;16:5910. doi: 10.1021/ol502918g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The conjugate addition product exists in equilibrium with the starting materials and is known to readily form at room temperature. This beta-amino ketone is unstable under standard column chromatography conditions. See reference 10j.

- 15.For selected reviews on pyrrolizidine natural products, see: Hartmann T, Witte L. In: Alkaloids: Chemical and biological perspectives. Pelletier SW, editor. Vol. 9. Pergamon Press Ltd; Headington Hill Hall, Oxford OX3 0BW, England: Pergamon Press Inc; Maxwell House, Fairview Park, Tarrytown, New York 10523, USA: 1995. p. 155.Daly JW, Spande TF, Garraffo HM. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1556. doi: 10.1021/np0580560.Robertson J, Stevens K. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31:1721. doi: 10.1039/c4np00055b.

- 16.Hoffmann RW. Chem Rev. 1989;89:1841. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxidation of 1a can be achieved in the absence of TEMPO, but reactions were found to be much slower. For instance, under otherwise identical conditions of Scheme 3 but without TEMPO, the yield of 7 was only 13% with most of 1a remaining unchanged.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.