Abstract

Background:

Heart transplant surgeries using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) typically requires mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICU) in post-operation period. Ultra fast-track extubation (UFE) have been described in patients undergoing various cardiac surgeries.

Aim:

To determine the possibility of ultra-fast-track extubation instead of late extubation in post heart transplant patients.

Materials and Methods:

Patients randomly assigned into two groups; Ultra fast-track extubation (UFE) group was defined by extubation inside operating room right after surgery. Late extubation group was defined by patients who were not extubated in operating room and transferred to post operation cardiac care unit (CCU) to extubate.

Results:

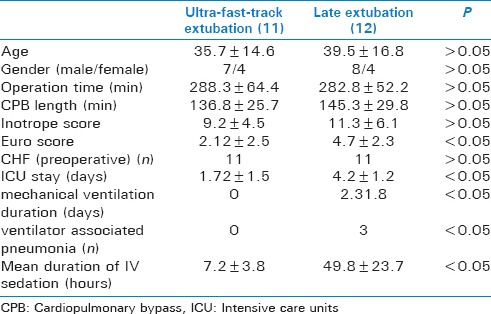

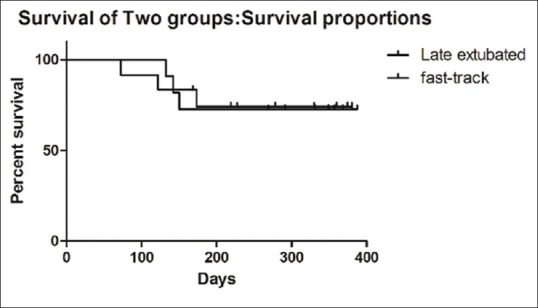

The mean cardiopulmonary bypass time was 136.8 ± 25.7 minutes in ultra-fast extubation and 145.3 ± 29.8 minutes in late extubation patients (P > 0.05). Mechanical ventilation duration (days) was 0 days in ultra-fast and 2.31 ± 1.8 days in late extubation. Length of ICU stay was significantly higher in late extubation group (4.2 ± 1.2 days) than the UFE group (1.72 ± 1.5 days) (P = 0.02). In survival analysis there was no significant difference between ultra-fast and late extubation groups (Log-rank test, P = 0.9).

Conclusions:

Patients undergoing cardiac transplant could be managed with “ultra-fast-track extubation”, without increased morbidity and mortality.

Keywords: Critical care, ultra fast-track extubation, heart transplant, heart transplant surgery

INTRODUCTION

Heart transplant surgeries using cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) typically requires mechanical ventilation in intensive care units (ICUs) during post-operation period. Some centers attempt early endotracheal extubation as part of a fast-tracking strategy, whereas others prefer mechanical ventilation in ICU as their routine patient management in the postoperative period.[1] Generally, the term “early extubation” is applied when the endotracheal tube is removed within 6 to 8 hours after the surgery.[2]

Fast-tracking and early endotracheal extubation have been described in patients undergoing various cardiac surgeries; however, criteria for patient selection have not been validated in a prospective manner.[3] Ultra Fast-track extubation (UFE) has been applied when patient is extubated in operating room (OR). The desire to reduce hospital costs by shortening ICU and hospital stay interest in early extubation has become oblige to current cardiothoracic surgery.

Besides, late extubation expose patients to multiple risk such as infectious complications, ventilator associated pneumonia, and atelectasis. The purpose of the present study was to determine the possibility of fast extubation instead of late extubation in post heart transplant patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was reviewed and approved by the University Review Board and hospital ethics committee and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in an appropriate version of the 2000 Declaration of Helsinki (http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm). Information about trial was given comprehensively both orally and in written form. All patients gave their informed written consents prior to their inclusion in the study according to University Hospital Ethical Board Committee.

Patient selection

Patients were selected in a prospective, randomized, controlled trial at a 1-year time period from those who underwent heart transplantation. Patients were eligible if they had undergone cardiac transplant, higher than 18 years of age. Randomization was performed based on odd number to ultra-fast-track extubation and evens to standard extubation. Ultra-fast-track extubation group were defined by extubation inside OR right after surgery. Late extubation group was defined by patients who were not extubated in OR and transferred to post-operation cardiac care unit (CCU). Patient in late extubation group had successfully passed mechanical ventilation weaning screening test or spontaneous breathing trial on the day of extubation.

Exclusion criteria were any patient with lung problems (impaired preoperative pulmonary function test), younger than 18 years or older than 70 years, pregnant, had a Simplified Acute Physiology Score II greater than 80, mechanical ventilation preoperatively, surgical procedure complexity assessed with the Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS) score <4.[4] Contraindications to ultra-fast-track extubation were (except for failure to meet standard extubation criteria) hemodynamic instability and persistent bleeding at the end of operation.

Demographic, preoperative and perioperative physiologic and radiographic features, coexisting conditions, and mechanical ventilation characteristics at randomization were recorded. Preoperative predicted operative mortality was calculated using the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation.

Ultra fast-track extubation

Patients underwent ultra-fast-track extubation in OR in case of stable hemodynamics (blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate), warm peripheries, adequate blood gas exchange, adequate muscle strength, satisfactory urine output, acceptable hematocrit chest tube drainage, and adequate pain control. Postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram was done in all patients before extubation.

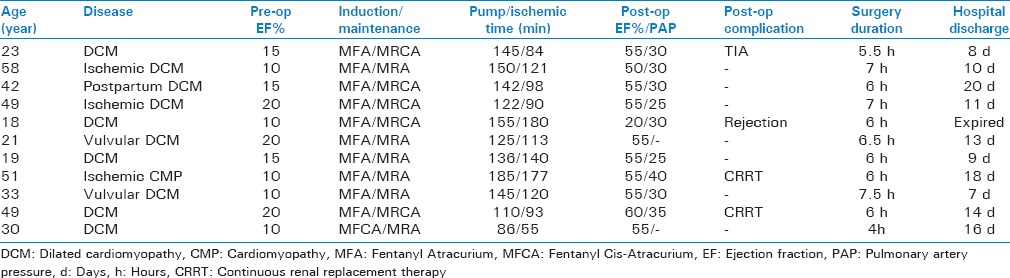

The reasons given by the anesthesiologists for deferring extubation are listed in Table 1. Significant pulmonary hypertension (PHT) after the discontinuation of cardio-CPB had been completed (independent of preoperative PHT). it was the most common cause for deferring OR extubation, followed by hypoxemia, coagulopathy, and hemodynamic instability.

Table 1.

Characteristics and pump time and hospital discharge days of patients with

Statistical analysis

All multiple comparison tests were two-tailed. Direct comparisons between two treatment groups were performed with the unpaired Student t-test or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney test when the data sets were not normally distributed. A survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards (COX PH) analysis. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant. All statistical analyzes were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 18.

RESULTS

Eleven patients were ultra-fast-track extubated (UFE) within operating room and 12 patients were late-extubated (LE) after 24 hours in CCU. Mean duration of ventilation among UFE patients was 36.2 ± 12.3 minutes and among LE patients was 28.7 ± 9.6 hours. The mean age of UFE patient was 35.7 ± 14.6 years and 39.5 ± 16.8 years in LE (P > 0.05). The mean weight of UFE patient was 76.8 ± 15.3 kg and 72.4 ± 18.4 in LE patients (P > 0.05). The mean CPB time was 136.8 ± 25.7 minutes in UFE and 145.3 ± 29.8 in LE patients (P > 0.05). Various aspects of UFE patients are provided in Table 1.

However, patients in the prolonged intubation group had more frequent unscheduled extubation and reintubations or recannulations. After adjustment for repeated operations, heart transplantations, and renal replacement therapy at base line remained similar between group differences in primary and secondary outcomes [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of patients outcomes characteristics between Ultra-fast-track extubation and late extubation

Finally using Kaplan-Meier and COX PH analysis, we considered death in follow-ups as status variable (event). Patients were censored from study if they failed to follow-up. The length of survival was the time between operation and death or end of follow-up time at 400 days. In survival analysis, there was no significant difference between UFE and LE groups (Log-rank test P = 0.9) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curve for both fast-track and late extubation groups survival were not significantly different (Log-rank test P value = 0.9)

DISCUSSION

Late extubation and mechanical ventilation is a part of postoperative care in cardiac surgery. Recent advances in surgical and anesthetic techniques have facilitated early extubation following cardiac surgery and heart transplant.[5] Potential benefits of an early extubation are decreasing cardiac and respiratory morbidity,[6] increasing cardiac performance, and lower rate of nosocomial pneumonia.[7] Early extubation has been shown to expedite ICU discharge[8] as well as overall length of stay, thus leads to reduce cancellation of surgery and decrease cost of patient care.[2] Studies have shown that early extubation after elective cardiac surgery of patients has not increased perioperative morbidity.[9,10]

In this study, ultra-fast-track extubation has provided much benefit for patients, who require prolonged mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery, in terms of mechanical ventilation duration, length of ICU stay, mortality rate, or frequency of infectious complications like ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). None of the patients had any severe underlying disease to compromise our study. The major factor that caused delay in UFE strategy was deep sedation and confusion. The reason for deep sedation was variable doses of intraoperative fentanyl and midazolam.

Other groups employ UFE strategy for all patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery, fulfilling the fast track criteria with the aim to wean and extubate patients within the first 6 hours following surgery.[11] In another study on 109 patients, no patient required reintubation within the first 24 hours after operation and only one patient required reintubation 3 days after operation for sputum retention.[12] Ultra-fast-track anesthesia using an ultra-short acting opiate remifentanil was used in 160 unselected patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting. Extubation within 10 minutes of the end of operation was feasible in 150 patients (94%). Five patients (3%) were extubated within 2 hours, and the remaining 5 patients (3%) were converted to standard anesthesia.[13,14] Another study on 304 patients receiving either a typical fentanyl/isoflurane/propofol regimen or a remifentanil/isoflurane/propofol regimen for ultra-fast-track cardiac anesthesia showed the efficacy of utilization of remifentanil and fentanyl in fast-track.[15]

In another study, it has been showed that CPB time and aortic cross clamp time are two factors which delay the early extubation.[16] Age, weight, sex, severity of pulmonary artery hypertension, and type of ventricular septal defect (VSD) did not affect early extubation.[17] Longer CPB time is consistently associated with prolonged mechanical ventilation after coronary artery disease (CHD) surgery.[3] This is not surprising, because longer CPB time is required for more complex cases or if unexpected difficulties occur.[18] Despite this, the complexity of the cases alone did not predict successful extubation in the OR in our analysis. Furthermore, longer CPB time is associated with an increased risk of inflammatory response syndrome with generalized edema, decreased respiratory compliance, acute lung injury, and coagulopathy, all of which affect the ability to extubate a patient immediately after surgery.[19]

In conclusion, patients undergoing elective repair may be managed with “ultra-fast-track extubation,” without increased morbidity and mortality. Prolonged unnecessary hospitalization contributes little, if any, to a more favorable therapeutic outcome. Family reliability and ready access to the cardiac surgical team will result in satisfactory outpatient resolution of most late-onset complications. Implementation of ultra-fast-track extubation provided adequate hemodynamic control and facilitated OR extubation in all patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trouillet JL, Combes A, Vaissier E, Luyt CE, Ouattara A, Pavie A, et al. Prolonged mechanical ventilation after cardiac surgery: Outcome and predictors. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:948–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marianeschi SM, Seddio F, McElhinney DB, Colagrande L, Abella RF, de la Torre T, et al. Fast-track congenital heart operations: A less invasive technique and early extubation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:872–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis S, Worley S, Mee RB, Harrison AM. Factors associated with early extubation after cardiac surgery in young children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:63–8. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102386.96434.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Spray TL, Moller JH, Iezzoni LI. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:110–8. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng DC, Wall C, Djaiani G, Peragallo RA, Carroll J, Li C, et al. Randomized assessment of resource use in fast-track cardiac surgery 1-year after hospital discharge. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:651–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200303000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Djaiani GN, Ali M, Heinrich L, Bruce J, Carroll J, Karski J, et al. Ultra-fast-track anesthetic technique facilitates operating room extubation in patients undergoing off-pump coronary revascularization surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2001;15:152–7. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2001.21936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng D. Anesthetic techniques and early extubation: Does it matter? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14:627–30. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2000.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westaby S, Pillai R, Parry A, O’Regan D, Giannopoulos N, Grebenik K, et al. Does modern cardiac surgery require conventional intensive care? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993;7:313–8. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(93)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng DC, Karski J, Peniston C, Asokumar B, Raveendran G, Carroll J, et al. Morbidity outcome in early versus conventional tracheal extubation after coronary artery bypass surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:755–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Kim KH, vanHeeckeren DW, Murrell HK, Cmolik BL, Graber R, et al. Cost analysis of early extubation after coronary bypass surgery. Surgery. 1996;120:611–7. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reis J, Mota JC, Ponce P, Costa-Pereira A, Guerreiro M. Early extubation does not increase complication rates after coronary artery bypass graft surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J CardiothoracSurg. 2002;21:1026–30. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Royse CF, Royse AG, Soeding PF. Routine immediate extubation after cardiac operation: A review of our first 100 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:1326–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00829-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Straka Z, Brucek P, Vanek T, Votava J, Widimsky P. Routine immediate extubation for off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting without thoracic epidural analgesia. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1544–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03934-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowler I, Djaiani G, Abel R, Pugh S, Dunne J, Hall J. A combination of intrathecal morphine and remifentanil anesthesia for fast-track cardiac anesthesia and surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:709–14. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.128414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng DC, Newman MF, Duke P, Wong DT, Finegan B, Howie M, et al. The efficacy and resource utilization of remifentanil and fentanyl in fast-track coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A prospective randomized, double-blinded controlled, multi-center trial. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1094–102. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200105000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowper PA, Peterson ED, DeLong ER, Jollis JG, Muhlbaier LH, Mark DB. Impact of early discharge after coronary artery bypass graft surgery on rates of hospital readmission and death. The Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:908–13. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lahey SJ, Borlase BC, Lavin PT, Levitsky S. Preoperative risk factors that predict hospital length of stay in coronary artery bypass patients > 60 years old. Circulation. 1992;86(Suppl 5):II181–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemmerling TM, Lê N, Olivier JF, Choinière JL, Basile F, Prieto I. Immediate extubation after aortic valve surgery using high thoracic epidural analgesia or opioid-based analgesia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:176–81. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neirotti RA, Jones D, Hackbarth R, Paxson Fosse G. Early extubation in congenital heart surgery. Heart Lung Circ. 2002;11:157–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1444-2892.2002.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]