Abstract

Gene therapy is the introduction of genetic material into patient’s cells to achieve therapeutic benefit. Advances in molecular biology techniques and better understanding of disease pathogenesis have validated the use of a variety of genes as potential molecular targets for gene therapy based approaches. Gene therapy strategies include: mutation compensation of dysregulated genes; replacement of defective tumor-suppressor genes; inactivation of oncogenes; introduction of suicide genes; immunogenic therapy and antiangiogenesis based approaches. Preclinical studies of gene therapy for various gynecological disorders have not only shown to be feasible, but also showed promising results in diseases such as uterine leiomyomas and endometriosis. In recent years, significant improvement in gene transfer technology has led to the development of targetable vectors, which have fewer side-effects without compromising their efficacy. This review provides an update on developing gene therapy approaches to treat common gynecological diseases such as uterine leiomyoma and endometriosis.

Keywords: Gene therapy, Adenovirus, Uterine leiomyoma, Endometriosis

1. Introduction

1.1. Gene therapy

Gene therapy is defined as the transfer of genetic material (DNA or RNA) into target cells for the purpose of curing or alleviating disease(s) [1]. The first authorized human gene therapy trial was initiated in 1990 for the treatment of an autosomal recessive form of severe combined immunodeficiency (ADASCID) [2]. Although limited significant clinical benefit was observed, an avenue of hope was opened especially when the first report of success with gene therapy was reported by Cavazzana-Calvo et al. [3]. This involved the treatment of two infants with the X-linked form of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID-X1) caused by mutations in the common gamma chain (γc) gene. This landmark success was subsequently overshadowed by the occurrence of acute leukemia as a complication of gene therapy in two of 14 infants treated. During the past decade, there has been a growing appreciation of the broader scope for gene therapy.

Achieving therapeutic benefit requires the genetic repair of large numbers of cells and, depending on the nature of the target disease, durable long-term expression of the gene(s) of interest. For the vast majority of potentially amenable diseases, existing gene delivery technologies are simply not efficient enough to repair sufficient numbers of cells to confer optimal and permanent therapeutic benefit. Recently, tremendous efforts have been focusing on constructing ideal vectors and selecting the suitable disease that can be targeted by gene therapy approach to overcome these drawbacks [4]. In this regard uterine fibroids represent a very good candidate for gene therapy because of many inherent characters [4].

1.2. Gene delivery methods

Gene delivery technologies can be broadly divided into those that exploit relatively simple non-viral strategies and those that exploit favorable aspects of virus biology. Examples of the former include microinjection, calcium phosphate co-precipitation, electroporation, microparticle bombardment and liposome technology. The basic drawbacks of these approaches are a very low efficiency of gene delivery, and the absence of specific mechanisms to secure a favorable intracellular fate for the introduced DNA.

Although tremendous advances have been made in gene transfer technology, an ideal vector system has not yet been constructed [4]. The ideal vector for gene delivery would fulfill the following criteria: (i) the vector should be easy to produce at a higher titer to allow the delivery of a small volume and should be amenable to commercial production and processing; (ii) the vector should be able to express the transgene over a sustained period and the expression should be precisely regulated; (iii) immunologically inert, and therefore allow for repeated administration; (iv) specificity for the targeted cells; (v) the vector should have no size limit to the genetic materials it can deliver; (vi) the vector should allow for site-specific integration into chromosome of target cells or should reside in the nucleus as an episome and (vii) the vector should have the ability to transfect both dividing and non-dividing cells [4–6]. The fulfillment of these criteria represents a challenge.

1.2.1. Non-viral vector

A naked DNA injection, without any carrier, into local tissues or into the systemic circulation is the simplest and safest physical/mechanical approach for gene therapy [7]. The use of this approach is limited at present, by its comparatively low efficiency. Among the physical methods commonly used for gene delivery are microinjection, particle bombardment (gene gun) and electroporation.

Microinjection: Microinjection is the simplest gene delivery method. Microinjection of naked DNA directly into the nucleus was shown to bypass cytoplasmic degradation, resulting in a much higher level of gene expression than intracytoplasmic injection [8].

Gene gun: The concept of gene-mediated particle bombardment, gene gun, is to move naked DNA plasmid into target cells on an accelerated particle carrier with a device called the gene gun [7]. Because of their small size, the DNA-loaded particles penetrate the cell membrane and carry the bound DNA into the cell. The DNA dissociates from and is expressed intra-cellularly [9,10]. The major application of this technology is genetic immunization, with the most obvious target being the skin.

Electroporation: Electroporation designates the use of electric pulses to transiently permeabilize the cell membrane and produces an electrophoretic effect on DNA, leading the polyanionic molecule to move towards or across the destabilized membrane [11].

Synthetic vectors: Synthetic vectors provide opportunities for improved safety, greater flexibility and more facile manufacturing [12]. In general, synthetic vectors (cationic lipids and polymers), complex with DNA, condense the genetic material into small particles. Such complexes of plasmid DNA with cationic lipids and polymers are known, respectively, as lioplexes and polyplexes. These small particles mediate their cellular entry and protect the delivered genes by sterically blocking the access of nucleolytic enzymes [13]. Technically, these vectors are relatively straightforward and easily scaled up and produced in large amounts [14].

1.2.2. Viral vectors

The basic concept of viral vectors is to utilize the innate ability of the virus to deliver genetic material into the infected cells [4]. Viral vectors are derived from viruses with either RNA or DNA genomes and are represented as both integrating and non-integrating vectors. The viral vectors include retrovirus, adenovirus, adeno associated virus (AAV), lentivirus and herpes simples virus (HSV). They are different in their immunogenicity, vector tropism, maximum size of gene that can be packaged and integration into the host genome leading to persistent transgene expression in dividing cells [4].

1.2.2.1. Adenovirus vectors

1.2.2.1.1. Adenovirus vector structure and pathway of infection

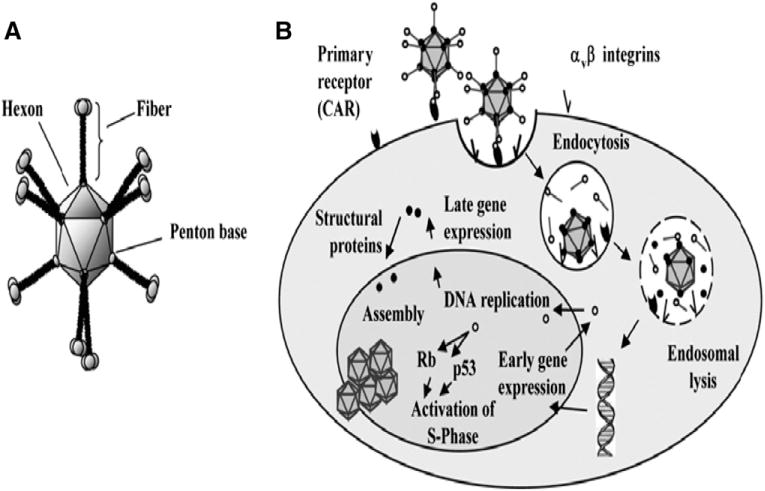

Adenoviruses are DNA viruses. They contain about 36 kb of double-stranded DNA. Adenoviral infection is mediated by binding of the knob region, located at the carboxy terminus of the fiber, to its corresponding receptor, which is the Coxsackie-Adenovirus Receptor (CAR) for most serotypes [15]. This binding is followed by interaction between cellular integrins and an arginine–glycine–aspartic acid motif (RGD-motif) located at the adenovirus penton base. This binding leads to the formation of endosomes and viral internalization. Following this receptor-mediated endocytosis, the virus escapes from the endosome and the adenoviral DNA is transported into the nucleus. Then the virus docks to the nuclear core complex receptor and genes from the early region 1 (E1a and E1b) are quickly transcribed (Fig. 1) or in case of non replicating Ads, transgene expression begins [16].

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram depicts a) Adenovirus virion b) Adenovirus infection pathway [16].

The natural tropism of intravascular Ad results in accumulation mainly in the liver, spleen, heart, lung and kidneys [17–20]. Tissue macrophages, such as Kuppfer cells of the liver, have a major role in clearing Ad from blood.

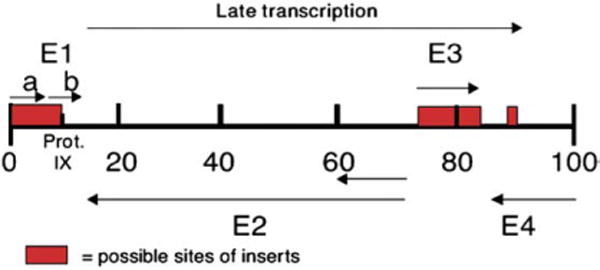

At least three regions of the viral genome can accept insertions or substitutions of DNA to generate a helper independent virus: a region in E1, a region in E3, and a short region between E4 and the end of the genome [21]. In the fifth-generation vectors (Ad5), the E1, E3 regions are removed to make room for the therapeutic transgene and to prohibit viral replication [22] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Structure of Adenovirus DNA [22].

1.2.2.1.2. Adenovirus vectors: merits and demerits

Replication-incompetent adenoviral vectors (Ad) have emerged as very popular and safe vectors for human gene therapy and are the most commonly used vehicle in clinical trials [23]. The use of Ad vectors in gene therapy is advantageous because of many positive attributes including the following: (1) Ad has the ability to provide efficient in vivo gene transfer to both dividing and non-dividing cells [24]; (2) Ad has exhibited higher in vivo stability; (3) Ad stocks can be prepared to ultra-pure high concentrations (1013 particles/ml), which allow the delivery of large amounts of viral particles in finite volumes; (4) Ad is nononcogenic and stays episomic, which makes it relatively safe [25]; (5) Ad can accommodate larger transgenes of up to 7.5 kb [22]; (6) Ad supports high levels of gene targeting to the nucleus, which results in significant gene expression [23]; (7) Ad tropism can be manipulated permitting cell-specific transfection; targeting concept which aims at specific transduction of the target cells and hence decreases the tropism of Ad towards the normal cells and enhances the ability of the virus to infect tumor cells [26].

However, the gene delivery efficiency of human serotype 5 recombinant adenoviruses (Ad5) in tumor gene therapy clinical trials to date face some disadvantages, mainly due to the development of Ad-neutralizing antibodies within the human population limiting the gene transfer to target cells [27], short life span of gene expression due to local immune response against Ad5 [28], the inability of Ad5-based vectors to transduce important therapeutic target cell types due to paucity of the primary Coxsackie/Ad receptor (CAR) in many human tumors [29,30] as well as virus dissemination to normal tissues [28,30,31].

1.2.2.1.3. Adenovirus serotype 5 vectors modifications

It is well-established that Ad5-luc is CAR-dependent for cell entry [32]. Conversely, CAR is scarce in tumor tissues [31,33] or, at best, is relatively lacking on target cells in comparison with normal cells [34]. So Ad5 targeting to tumors could be useful to enhance the Ad5 tumor transfection as well as to limit the non target tissue transfection. Three principal means for achieving this goal exist: a) transductional targeting, (b) transcriptional targeting and (c) oncolytic virus principle.

Transductional targetingTransductional targeting aims at deletion of the broad tropism of Ad5 toward normal epithelial cells and/or enhances virus infectivity of CAR deficient tumor cells [35]. One such modification is the insertion of short peptide (21 amino acid) composed of arginine, glysine, and aspartate (RGD) to the H1 loop of the wild Ad5 fiber knob domain to reroute Ad5 binding to the cellular integrin [36,37]]. Another strategy is to employ knob switching by creating chimeric fibers possessing the knob domains of alternate human Ad serotypes beside the Ad5 native fiber, Ad5/3 and Ad5-sigma, which are created by substituting one Ad5 fiber with adenovirus serotype 3 (Ad3) or reovirus fiber, respectively. Functionally, Ad5-sigma utilizes CAR, sialic acid, and the junctional adhesion molecule 1 (JAM1) for cell entry [38], while Ad5/3 is redirected to bind the putative Ad3 receptors (CD80, CD86, or CD46) [32].Recently, more radical modifications based on xenotype knob switching with nonhuman adenovirus have been exploited, e.g., Ad5-CAV2 in which the Ad5 fiber knob is switched to that of the canine Ad serotype 2 [39].

-

Transcriptional targetingIn transcriptional targeting, the expression of the gene of interest is placed under the control of a tumor-specific promoter (TSP) that maintains a tumor-on status, a normal tissue-off status, especially liver off status [40,41] in order to achieve a higher level of tumor cell selectivity.

Tumor-specific promoters (TSP)

A promoter is the component of the genetic transcriptional unit that is involved in binding of the RNA polymerase, required for initiation of mRNA transcription [42,43]. Further, the promoter is activated by transcription factors presented under tissue-specific control [43]. Therefore, in order for a promoter to be activated in a particular tissue type, that tissue must express specific factors that recognize the promoter. Although a number of TSPs have been studied for cancer gene therapy, recent research has focused rigorously on evaluating candidate TSPs with regard to their specificity and selectivity attributes for transcriptional targeting of viruses [43–45].

-

Oncolytic adenovirus principleOncolytic or conditionally replicating adenovirus (CRAD) concept is another improvement in Ad based gene and viral therapy approaches. In these vectors, the viral genome and subsequent replication is modified in such a way that it will only be complemented by the tumor cell and lead to virus replication, oncolysis, and subsequent release of the virus progeny [46,47]. Normal tissue is spared due to lack of replication [48]. This replication cycle is important because it allows dramatic local amplification of the input dose, and, in theory, a CRAd could replicate until all tumor cells are lysed [49]. Several adenovirus examples have been developed for diseases such as cervical and prostate cancer [46,47]. The oncolytic virus implies two principles:

Deletion-based conditionally replicative adenovirus (type I CRAds)

Two approaches are utilized in type I CRADs. In the first approach, two mutations are introduced in the viral gene coding for the E1B protein, a region responsible for binding and inactivation of wild type p53 in infected cells leading to induction of S-phase-required for viral replication [50,51]. In the second approach, a 24 bp deletion was introduced in the constant region 2 (CR2) of the E1A gene [52]. This domain of the E1A protein is responsible for binding the retinoblastoma tumor-suppressor (Rb)/cell cycle regulator protein, thereby allowing the Ad to induce S phase entry[53]. As a result, CRAds with the either 24 E1A or E1B deletions have reduced ability to overcome G1-S checkpoint in normal cells and therefore cannot replicate. Conversely, both Rb and p53 pathways are defective in most tumor cells, and hence viruses can replicate [54,47].

Promoter-based conditionally replicative adenovirus (Type II CRAd)

In type II CRAD, a TSP such as mesothelin promoter (MSLN), replaces endogenous viral promoter to control early translated genes (E1A) of the virus [49]. This restricts viral replication to target tissues, actively expressing the transcription factors that stimulate this TSP.

1.3. Gene therapy strategies

These treatment strategies include mutation compensation, molecular chemotherapy, immunopotentiation and alteration of drug resistance.

1.3.1. Mutation compensation

Mutation compensation involves correction of the genetic lesions that are etiologic for neoplastic transformation [55]. This gene therapy strategy is also known as correctional gene therapy and focuses on functional ablation of expression, dysregulated oncogenes, replacement or augmentation of the expression of tumor-suppressor genes or interferences with signaling pathways of some growth factors or other biochemical processes that contribute to the initiation or the progression of the tumor [56–58]. The purest examples of this gene therapy strategy are the restoration of normal function of tumor-suppressor genes (P53) and interference with over expressed wild type estrogen receptor (ER) using dominant negative ER (DNER) [59].

1.3.2. Molecular chemotherapy

Molecular therapy, which is known also as cytoreductive gene therapy or suicide gene therapy, refers to the delivery of genes that kill cells by direct or indirect effects. These strategies include gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy, pro-apoptotic, anti-angiogenic and gene-directed radioisotopic therapy [60–63]. Gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy involves delivering a gene that encodes an enzyme, which then converts an innocuous prodrug to a toxic agent within tumor cells. The two most widely used gene-directed enzyme prodrug systems are Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSVTK) plus ganciclovir (GCV) and Escherichia coli bacterial cytosine deaminase plus 5-fluorocytosine [64].

1.3.3. Immunopotentiation

Modulation of immune response is particularly attractive as a key focus of tumor gene therapy. It involves the enhancement of the immune system’s ability to destroy tumor cells. The immunopotentiation gene therapy capitalizes on strategies such as the expression of cytokine genes which may enhance the activity of antigen-presenting cells and T cells [65], the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, such as B7.1 and B7.2, which facilitate the recognition and killing of tumor cells [66,67] or the delivery of exogenous immunogens, which generate local inflammatory reaction that increases the ability of antigen-presenting cells to recognize tumor-associated antigens [68].

1.3.4. Alteration of drug resistance

A major hurdle in cancer chemotherapy is anti-cancer drug-related toxicity, mainly the myelosuppression [69]. Multidrug resistance gene (MDR1) confers multidrug resistance towards several anti-cancer drugs [70]. Gene therapy approaches involving retroviral transfer of MDR1 gene, aldehyde dehydrogenase class 1 gene (ALDH-1) and mutated dihydrofolate reductase gene to haematopoietic progenitor cells protects against the myelosuppression induced by these drugs [70–72].

1.3.5. Oncolytic virus concept

Oncolytic viruses such as conditionally replicating adenoviruses (CRAds), take the advantage of tumor-specific changes, which allow preferential replication in and subsequent death of tumor cells [46,47].

1.4. Genes targeted in gene therapy of benign gynecological diseases

1.4.1. Dominant negative estrogen receptor (DNER) concept

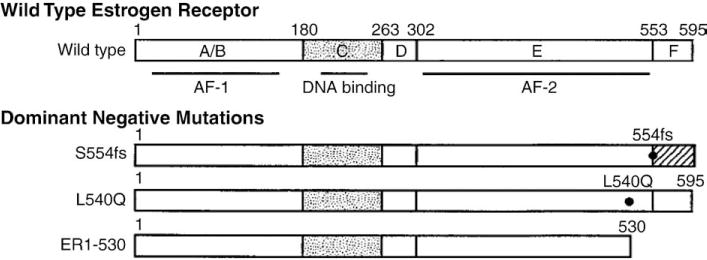

Estrogen receptor (ER) consists of six domains (A–F), which include at least two activation functions (present in the A/B and E domains), a DNA binding region (domain C), ligand binding and dimerization regions present in domain E [73,74] (Fig. 3). Previous biochemical studies have identified particular amino acids and regions of the receptor that are critically involved in some of these functions [75–77].

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram of the wild type and mutant estrogen receptors [117].

Several dominant negative ER mutants have been generated [78–80], including truncated receptors (ER1-530 and ER1-536, missing the last 65 or 59 amino acid residues), a point mutant (L540Q), and a frameshift mutant (S554fs). These mutants are altered such that the ligand-dependent transcription activation region in domain E of the ER is inactivated (S554fs and L540Q mutants) or missing (ER1-530 mutant) [78]. However, the three mutants bind estradiol with good affinity [75,78]. These dominant negative receptors were shown to effectively suppress the ability of wild type ER to activate transcription when they are either co-expressed with wild type ER in cells or introduced into cells containing endogenous ER [78,79].

Dominant negative forms of the ER have been suggested as a method to inactivate the wild type ER [81] demonstrated that adenovirus-directed expression of the frame-shifted ER (S554fs) suppressed the proliferation of ER-positive breast cancer cells. Lee et al. [82] reported that adenovirus-mediated expression of a truncated receptor (ER1-536) induced apoptosis in rat pituitary prolactinoma cells and inhibited tumor growth in nude mice. This ER mutant exerts its growth-inhibiting effect by making inactive heterodimers with wild type ERα (the dominant form of ER in leiomyoma tissue) as well as ERβ. These aberrant heterodimers are either unable to bind to the estrogen-responsive elements (ERE) in different growth-related genes or unable to activate transcription when bound to ERE [78].

1.4.2. Herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase gene/Ganciclovir approach

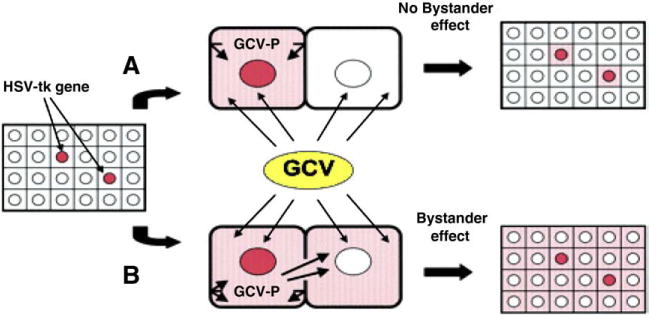

The Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV1TK) suicide gene therapy system involves the targeted transfection of cells with the HSV1-TK gene, followed by treatment with the prodrug Ganciclovir (GCV) to induce tumor cell death (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

HSV1TK/GCV By standard effect: A; normal cells with low GIJ protein level B; tumor cells with high GIJ protein level [90].

GCV, a nontoxic guanosine analogue, is specifically metabolized into the toxic triphosphorylated form (GCVTP) in presence of herpes simplex thymidine kinase [83]. Incorporation of this toxic metabolite into polymerizing DNA results in nascent chain termination by inhibiting DNA polymerase, and single-strand breaks [83,84], thereby inhibiting DNA synthesis and blocking the cell cycle, ultimately leading to cell death via apoptosis [84,85].

Fortunately intratumoural delivery of HSV1TK gene followed by GCV administration results in targeted killing of both HSV1TK-positive cells and neighboring negative cells (by stander effect) [61,86,87]. The by stander phenomenon has been observed both in vitro [88] and in vivo [89]. The effectiveness of cytotoxic gene therapy depends greatly on the presence of a “bystander effect” because currently, it is impossible to achieve 100% gene transfer in vivo.

1.5. Benign gynecological diseases

1.5.1. Uterine leiomyoma and gene therapy

Uterine leiomyomas are the most common gynecological tumors affecting more than 25% of reproductive-age women [91]. Symptomatic fibroids are associated with a host of clinical problems including menorrhagia, pelvic pressure, pelvic pain, spontaneous abortions, and infertility [92]. As a consequence of these complications, uterine fibroids rank as the major reason for hysterectomy in the United States, accounting for approximately 67% of all hysterectomies performed among middle-aged women [93,94], or one-third of all total hysterectomies performed annually in the United States [91].

Unfortunately, there is no optimal treatment option for uterine leiomyoma and the gold standard treatment is surgery [95,96]. This surgical option is extremely costly, carries a risk of major complications and constitutes a clinical dilemma for patients desire to preserve their fertility [97,4]. Thus, the development of novel therapeutic strategies would be a welcome addition for uterine leiomyoma; especially, if it is conservative, relatively safe localized method of treatment which is able to ablate the uterine fibroid without interfering with ovulation, local blood supply to uterus and systemic sex hormonal milieus and hence the fertility [4,95,98–100].

Uterine leiomyoma is an attractive target for gene therapy because of several inherent biologic features. The disease is localized and well-circumscribed in the uterus which simplifies targeting the treatment to the tumor by direct ultrasound-guided intratumor injection using existing technology [4]. Another favorable feature is that uterine fibroids are slow-growing tumors and marked clinical improvement of fibroid-related symptoms (e.g., irregular vaginal bleeding, pelvic pain, and infertility) and patient satisfaction does not necessitate complete resolution of the fibroid but rather a modest decrease in their size [101,102].

The first reported attempt to develop a gene therapy approach for the treatment of uterine fibroids was developed by Niu et al. [103] as a non-viral mediated transfer of the suicide gene for thymidine kinase into human leiomyoma cells. They demonstrated significant cell death when only 5% of the leiomyoma cells transfected. Unfortunately, this study was limited to in vitro study using human leiomyoma cell cultures.

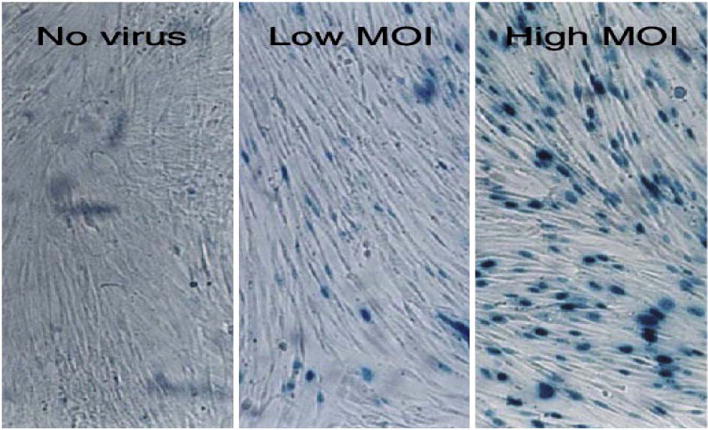

Our earlier laboratory studies demonstrated the optimal ability of adenovirus to transfect both human and Eker rat derived uterine leiomyoma cells (ELT3) at 10 PFU/cells and 100 PFU/cell respectively [104] and thus pointed out the potential use of adenovirus (Ad)-mediated gene therapy for uterine leiomyoma (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Adenovirus-infected human leiomyoma cells. LM-15 cells were optimally transfected with Ad-LacZ at a high multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 PFU/cell. At a low MOI of 5 PFU/cell, about 50% of cells were successfully transfected [104].

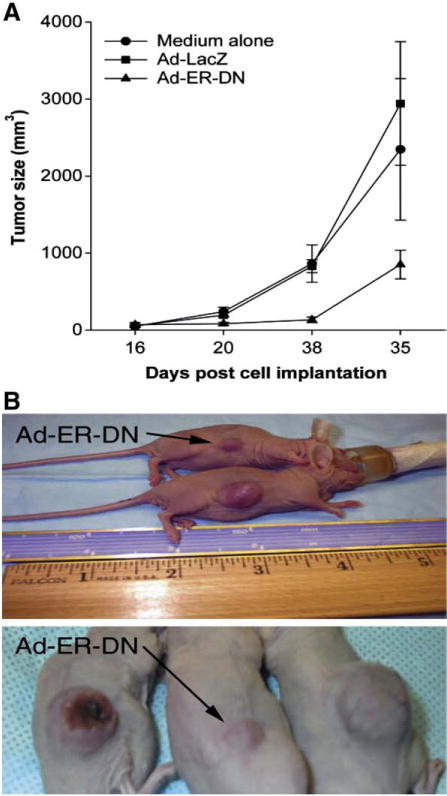

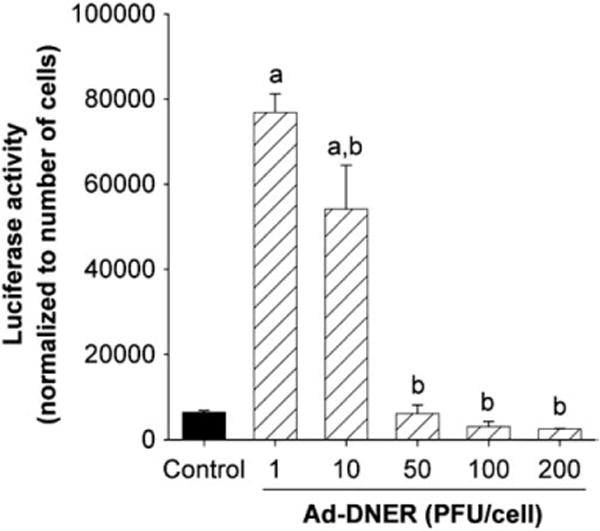

Applying mutation compensation gene therapy strategy via delivery of DNER by adenovirus vehicle to perturb the estrogen-signaling pathway was very encouraging [104–106]. In an in vitro animal model, Ad5-DNER induced significant death in ELT3 cells. In addition, Ad-DNER induced an increase in both caspase-3 levels and the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio, with evident apoptosis in the TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase)-mediated dUDP nick-end labelling (TUNEL) assay [104]. In nude mice, rat leiomyoma cells transduced ex vivo with Ad-DNER supported significantly smaller tumors compared with Ad-LacZ treated cells 5 weeks after implantation. In mice treated by direct intratumor injection into pre-existing lesions, Ad-DNER caused immediate overall arrest of tumor growth [104] (Fig. 6). Furthermore, our subsequent in vitro work using both primary and immortalized human LM cells has also demonstrated that such treatment intercepted with the wild type estrogen receptor functions (Fig. 7) and modulated the expression of several genes implicated in leiomyoma growth, apoptosis, estrogen metabolism and extracellular matrix formation in cultured human leiomyoma cells [105].

Fig. 6.

Direct intratumor injection of adenovirus with dominant negative estrogen receptor (ER) inhibited tumor growth. Direct intratumor injection of the corresponding agent was performed on day 16 after cell implantation. (A) Ad-ER-DN treatment caused immediate overall arrest of tumor growth. The difference among treatment and control groups was highly significant (P=0.007). Results are mean±SD (n=10) of two independent experiments. (B) Tumors treated with Ad-ER-DN demonstrated inhibition of tumor progression [104].

Fig. 7.

Effect of Ad-DNER on transcriptional activity of endogenous ER of rat uterine leiomyoma cells (ELT3 cell line). The ER transcriptional activity was assayed using Ad-ERE-luc, and the relative light units were normalized to the cell number. Results are plotted as mean±SE of three independent experiments. P<0.01 was considered a significant difference from control (a) or from Ad-DNER 1 PFU/cell (b) [105].

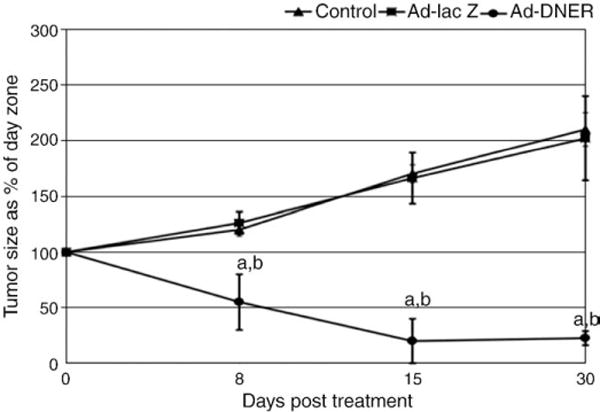

Also we demonstrated that Ad-DNER was able to markedly shrink Eker rat uterine leiomyoma volume. The shrinkage reached a peak of 80% and was sustained for 30 days after a single Ad-DNER inoculation (Fig. 8). Furthermore, Ad-DNER modulated the expression of several estrogen regulated genes controlling apoptosis (Fig. 9), proliferation and extracellular matrix formation [106]. This provided potential mechanisms of action of this approach and explains the rapid and impressive tumor shrinkage. Noteworthy, locally injected Ad in these approaches was minimally disseminated, only into liver and uterus of injected animals. Also this treatment approach was safe and did not induce any macroscopic or microscopic tissue damage nor caused any significant changes in serum liver function tests over the follow up period (one month) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 8.

Ad-DNER injection into Eker rat uterine leiomyoma significantly shrinks total leiomyoma volume (compared to both vehicle control and Ad-LacZ treated animals). Tumor volume was calculated as a percentage of its corresponding day zero (pretreatment) volume and presented as M±SE of at least three animals at each time point. a,b indicate significant difference from vehicle control and Ad-LacZ treated animals, respectively, at P<0.05 [106].

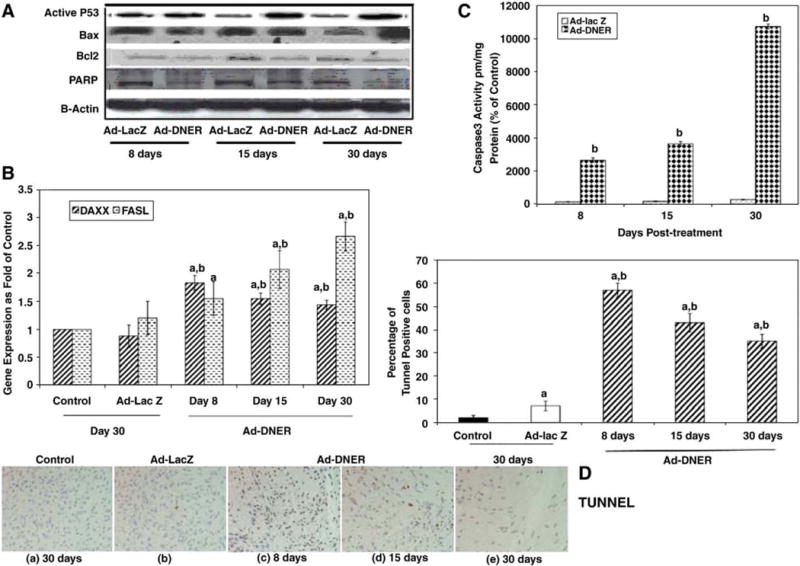

Fig. 9.

Ad-DNER treatment of fibroid lesions in Eker rats induces modulation of several estrogen regulated genes controlling both (A) intrinsic (p53, BAX, Bcl2 and PARP) and (B) extrinsic (DAXX and fas L) apoptotic pathways. Data represent uterine leiomyoma tissues collected at 8, 15 and 30 days post Ad-DNER treatment compared to either vehicle control or Ad-lacZ treated group: (A) Protein levels assessed by western blot; (B) DAXX and FAS L mRNA expression; (C) demonstrate increased Caspase 3 activity; (D) increase in the percentage of positive TUNNEL cells in the Ad-DNER treated lesions. The letters a or b indicate significant difference from vehicle control or Ad-lac Z treated lesions respectively at P<0.05 using two tailed student T test in (C) caspase 3 experiment and Tukey test as post-ANOVA test in (B) RT-PCR and (D) TUNNEL assay experiments [106].

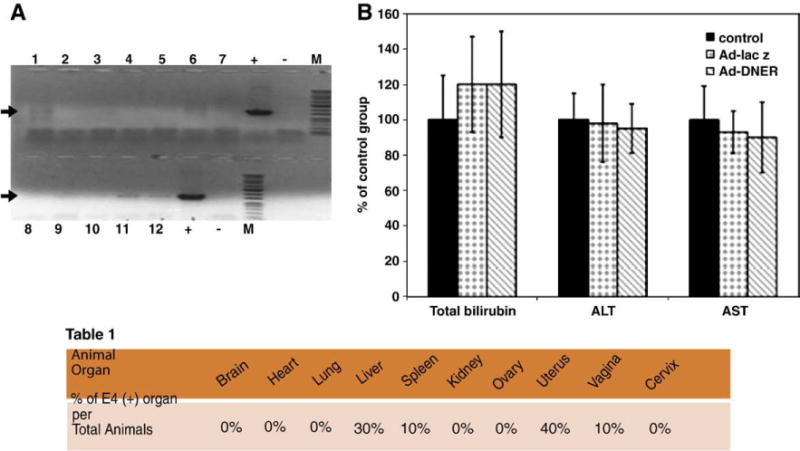

Fig. 10.

Safety studies of the Ad-DNER gene therapy approach after a single direct intra-fibroid treatment of Eker rat. (A) Assessment of adenovirus particles dissemination into Eker rat body organs by PCR amplification of the specific Ad5 E4 region detected by 714pb DNA band on 1% agarose gel. The band was detected mainly in tumor tissues while faint bands were detected also in uterus (lane 11) and liver (Lane 12) respectively, in 40% and 30% of the treated animals. (B) Although Ad-DNER particles were detected in the liver of 40% of Eker rats injected with adenovirus, Ad-DNER did not produce any significant change in liver function tests (AST, ALT and total bilirubin) evaluated 30 days post adenovirus injection, compared to vehicle control animals [106].

In a similar way suicidal gene therapy strategy has been tested in the context of uterine leiomyoma with impressive results [69,103,107]. Ad-HSV1TK/GCV effectively inhibited the growth of both ELT-3 cells and the primary human LM cells with impressive strong bystander effect [69]. This finding confirmed previous report by Niu et al. [103], using plasmid vector with the advantage of high probability of in vivo tumor transfection efficiency.

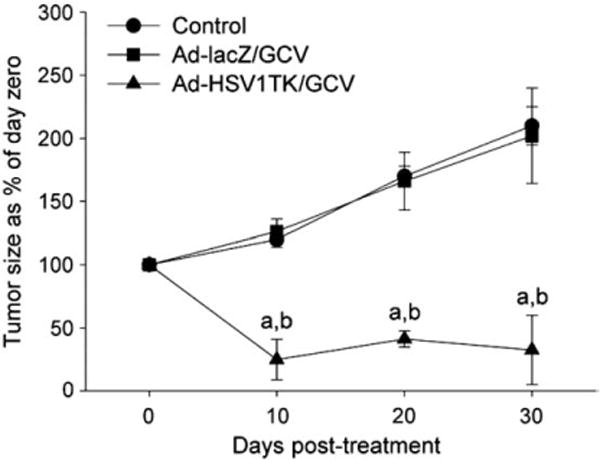

In Eker rat, an immunocompetent animal model of uterine leiomyoma, we demonstrated that the Ad-HSV1TK/GCV approach was very efficient in decreasing uterine leiomyoma volume whereas Ad-HSV1TK/GCV treatment significantly decreased uterine fibroid volume by 75%±16, 58.7%±6.3, and 67.5%±27.5 of pretreatment volume at days 10, 20, and 30, respectively. (Fig. 11). These effects were mediated via increased caspase 3 activity, Bax expression, TUNEL apoptosis marker; and decreased cyclin D1, PCNA, Bcl2, and PARP protein expressions [107]. Additionally, Ad-transfection was tumor-localized and safe to non target tissues which confirmed the safety. Furthermore, Ad-transfection induced local CD4+ and CD8+ infiltration which add back to the success of this approach.

Fig. 11.

Adenovirus-mediated delivery of herpes simplex virus 1 thymidine kinase gene (Ad-HSV1TK) (3×1010 PFU/cm3 of tumor) by a single direct injection into Eker rat uterine leiomyoma followed by a subcutaneous injection of GCV 50 mg/kg/day for 10 days significantly shrinks Eker rat uterine leiomyoma volume when compared with both Ad-LacZ/GCV and vehicle-treated animal groups. Uterine leiomyoma tumor volume was measured by both MRI scanning and caliper measurement. Tumor volume was calculated as a percentage from day 0. Each time point was represented by mean± SE of 3 animals. a,bIndicate a significant difference from control and Ad-LacZ/GCV-treated groups, respectively, at P<0.05 using the Tukey test as a post-ANOVA test [107].

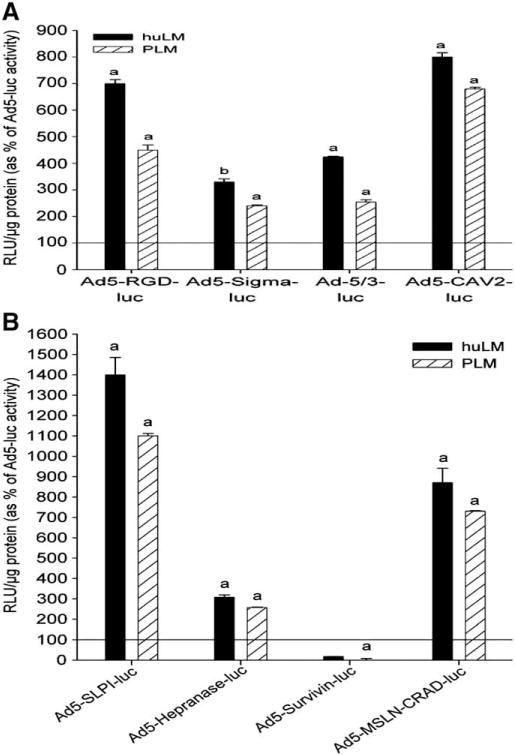

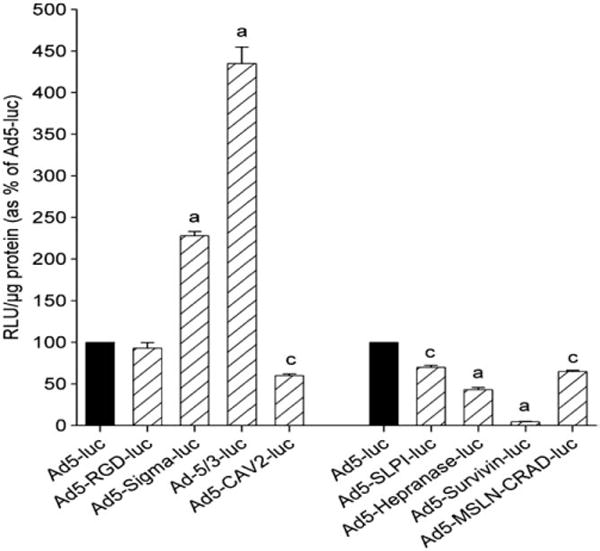

To optimize gene therapy of leiomyoma, the expression of the transgene should be restricted exclusively to leiomyoma. Selective expression of transgenes in leiomyoma can be achieved by transductional and/or transcriptional targeting. Fortunately, the localized nature of leiomyoma helps to identify the target easily for the clinical introduction of gene therapy vectors and hence avoid inadvertent transfection to the surrounding normal uterine myometrium (transductional targeting). For transcriptional targeting, however, the biological uniqueness of leiomyoma (such as leiomyomas-specific transcription factors or proteins) should be identified to design leiomyoma-specific promoter/vectors which would drive therapeutic gene expression only in leiomyoma tumor cells. Generating improved delivery systems and refining the mechanisms that control gene expression will be a key step in the development of safe clinical protocols for gene therapy of uterine leiomyoma. Thus we have presented the utility of several modified Ad vectors in the human leiomyoma cell line. Our goal was to identify the best Ad vector to enable the targeting of therapeutic genes to human leiomyoma cells with minimal effect on normal myometrial cells, as well as normal liver cells [108]. Our results demonstrated that Ad5-RGD-luc and Ad5-CAV2-luc, Ad5-SLPI-luc and Ad5-MSLN-CRAD-luc at 5, 10 and 50 PFU/cell, showed significantly higher expression levels of luciferase activity in both primary and immortalized human leiomyoma cells when compared with Ad5-Luc (Fig. 12). Additionally, these modified viruses demonstrated selectivity toward leiomyoma cells, compared with myometrial cells. In addition, these targeted modified Ad vectors exhibited lower liver cell transduction, compared with Ad5-luc, at the same dose levels [108].

Fig. 12.

Evaluation of modified adenovirus vectors in human leiomyam cells. (A) fiber-modified adenoviruses; Ad5-SLPI-luc, Ad5-heparanase-luc, and Ad5-MSLN-CRAD-luc and (B) transcriptional targeted adenoviruses;Ad5-SLPI-luc and Ad5-MSLN-CRAD-luc showed higher luciferase expression levels in both human primary (PLM) and immortalized leiomyoma (huLM) cells at 10 PFU/cell when compared with Ad5-luc at the same dose level, while survivin showed uterine leiomyoma cells off-profile. Luciferase activities (RLU) were normalized to the protein content and expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) of 4 separate experiments and plotted as percentage of Ad5-luc activity. a; Indicates significant differences compared with corresponding Ad5-luc at 10 PFU/cell (P<0.05) [108].

Construction of these candidate modified (improved) adenoviral vectors with promising therapeutic gene such as DNER or HSV1TK then testing these modalities in Eker rat, an immune competent animal model resembling the human situation, for long period of time might lead to a human clinical trial. This approach is not far from becoming a medical reality. By the end of the year 2005, worldwide, over 600 clinical trials using gene therapy have been conducted [109], and by the end of July 2007, worldwide, over 1300 clinical trials were done [110]. Most of these clinical trials were phase I and or phase II, which means their primary goal is determining the safety of the agents (phase I) or their potential efficacy (phase II) [111–114]. The fields of gynecology and gynecologic oncology now exist at the forefront of evolving novel gene therapy approaches to both benign and malignant disease [115,116]. However, gynecologic gene therapy has advanced to human clinical trials for ovarian carcinoma [115,116]. A phase III human clinical trial has begun in patients with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer [117].

1.5.2. Endometriosis and gene therapy

Endometriosis is a chronic and recurrent disease characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue (glands and stroma) outside the uterine cavity [118]. It affects 5% to 10% of reproductive-age women [119]. Endometriosis associated pelvic pain and subfertility impose a substantial burden on the quality of life of affected women. It also represents a significant financial burden in terms of the amount of money that has to be spent on expensive therapies [120]. The annual healthcare costs and costs of productivity loss associated with endometriosis at $2801 and $1023 per patient, respectively [121].

Endometriosis is an estrogen dependent disease and current medical therapy aims at suppressing ovulation with reduction in circulating estrogen to a postmenopausal level [122]. Such treatment is limited to short duration because of substantial hypoestrogenic effects including: hot flushes, dry vagina and loss of bone mineral density. Moreover, recurrence of pelvic pain occurs in 30–70% of patients within 6–18 months after discontinuation of treatment [123] and there is a 24% probability of recurrence of pelvic pain within 3 years after conservative surgery [99]. In addition, medical treatment has no beneficial effects on the treatment of endometriosis associated subfertility [124].

Seemingly, we are still far from having an ideal treatment for endometriosis. New therapies that act on endometriosis cells at a molecular level rather than to suppress ovarian estrogen production are still required for the therapeutic armamentarium against this disease [125].

Gene therapy is an emerging form of molecular medicine that has expanded in scope from malignant to benign diseases [104]. Gene therapy involves the introduction of genetic material to the cell, whose subsequent products will address the therapeutic outcome [115]. In the new millennium, endometriosis started to find its way to gene therapy applications.

In 2002, Dabrosin et al. [126] reported on gene therapy of endometriosis in a mouse model. Those investigators transplanted mouse endometrial tissues into the peritoneal cavity of estrogen-supplemented ovariectomized mice to develop endometriosis lesions. One week after transplantation, the first and second groups of mice were treated with intraperitoneal injection of 1 ml of PBS containing 1×109 PFU of adenovirus expressing murine angiostatin gene (Adangiostatin), which is a natural angiogenesis inhibitor or a control adenovirus, respectively. A third and fourth groups consisted of normally cycling mice, which were treated with intraperitoneal Adangiostatin or control virus, respectively. Mice were sacrificed on a subsequent period from 2 to 18 days post-treatment. In the first two groups, peritoneum and visceral organs were examined with a dissecting microscope, endometriosis lesions detected and removed for H&E staining and immunohistochemistry. Blood was collected for hormonal assays and peritoneal fluid obtained for angiostatin protein expression. Animals were weighted as were their uteri and ovaries.

The results have shown that endometriosis lesions were eradicated in 100% of the Ad-angiostatin treated mice within two weeks in comparison to only 15% of control virus-treated mice in the same time period (P<0.0001). Immunohistochemistry for Factor VIII demonstrated that on day 5 of Ad-Angiostatin treatment, not only the bulk of the experimental endometriosis tissue had decreased, but the content of the vasculature was markedly decreased both in extent and in numbers of vessels as compared to day 0. Western Blot analysis of peritoneal lavage showed bands corresponding to murine angiostatin protein in Ad-angiostatin treated but not in control virus-treated mice. In normal cycling mice, Ad-angiostatin treatment resulted in significant decrease in ovarian steroid production, reduction in ovarian size and weight with disappearance of follicles and corpora lutea, decrease in uterine weight and increase in body weight similar to that of ovariectomized mice.

Dabrosin et al. [126], concluded that inhibition of endometriosis associated angiogenesis through transient over expression of angiostatin gene delivered to the peritoneal cavity via adenovirus vector is an effective method for eradication of endometriosis lesions. The authors recommended that local or targeted delivery of the vector be considered to avoid untoward effects on normal ovarian and uterine functions.

Dominant negative mutants of estrogen receptors (DNER) are altered estrogen receptor forms that are unable to activate transcription of estrogen-responsive genes when estradiol binds to them. They have the additional property of being able to suppress the transcriptional activity mediated by the wild type estrogen receptor when both are co-expressed in the same cells [79, 127]. Our group studied the effects of transfer of dominant negative estrogen receptor genes to endometriosis cells via adenovirus vector in vitro [59].

We first tested the ability of adenovirus to transfect endometriosis cells in vitro. For this purpose, we used RT-PCR to measure mRNA expression of Coxsackievirus-Adenovirus Receptor (CAR), which is the main portal of adenovirus entry into cells, in primary endometriosis cells versus normal endometrial cells. Then, both cell types were transfected with adenovirus expressing β-galactosidase (Lac-Z) as a marker gene at different multiplicities of infection (MOIs) to determine transduction efficiency of adenovirus in endometriosis versus endometrial cells.

The results of this part of the study showed that CAR mRNA expression is significantly higher in endometriosis versus normal endometrial cells. Transduction of endometriosis and normal endometrial cells by adenovirus expressing marker gene confirmed these findings where adenovirus achieved a transduction efficiency of 80% in endometriosis cells versus 28% in normal endometrial cells at MOI of 50 PFU/cell (P<0.05).

The next step was to test the effects of transfection of endometriosis cells by adenovirus expressing dominant negative estrogen receptors (Ad-DNER). For this purpose, we used three groups of endometriosis cells: the first was treated with Ad-DNER, the second group was treated with a control virus and the third group was treated with medium alone. Cells were examined for cellular proliferation using a fluorometric assay implementing Hoechst 33258, cytokine production using Bioplex protein array system and cellular apoptosis using deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated (dUTP) nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay.

Our findings have shown that Ad-DNER-treated endometriotic cells, as compared with control virus-treated cells, showed cell rounding and detachment (cell death), a 72% reduction in the number of viable cells 5 days after transduction, significantly less production of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic cells.

The authors concluded that adenovirus cans efficiently transfect endometriosis cells in vitro. Dominant negative estrogen receptor genes, when transferred to endometriosis cells, can result in cellular death, reduce cellular proliferation, cytokine production and induce cellular apoptosis [59]. This new molecular based therapy allows functional stripping of estrogenic drive to endometriosis cells without suppression of ovarian steroid production thus preventing hypoestrogenic effects. Also, the ability of Ad-DNER treatment to reduce proinflammatory and angiogenic cytokine production by endometriosis cells conveys dual ablative effect on endometriosis via apoptosis and reduction in cytokine secretion which is essential for the pathogenesis of endometriosis [128].

Both our study and that of Dabrosin et al. utilized adenovirus serotype-5 (Ad5) as a viral vector for gene transfer. Ad5 as a gene transfer vector is easy to propagate in laboratories, has mild pathogenicity and low mutagenesis potential in humans. Also, Ad5 can transduce dividing and non-dividing cells. However, this wide viral tropism means that both target and non target cells will be transfected. This will lead to sequestration of the virus in non target tissues while limiting the amount of virus available for target tissues. Moreover, uptake of the viral vectors and their transgene by non target tissues increases toxicity to these tissues and increases the immune response against adenoviruses if they are taken by immune cells [25].

Transductional targeting involves selective gene transfer by the vector to particular tissue or cells of interest. This is achieved through inducing structural changes in adenovirus fiber to allow it to recognize receptors selectively expressed on pathological tissues only [44]. Transcriptional targeting depends on non selective transfer of the gene to different tissues; however, gene expression will be possible only in pathological tissues through driving the gene expression under tissue-specific promoters that are “on” in pathological tissues but “off” in normal tissues [129]. In a recent publication by our group, we screened a number of transductionally targeted and transcriptionally targeted adenoviruses to detect the ones that can achieve highest gene transfer and expression in endometriosis cells and lowest expression in normal tissues and cells [130]. The targeted adenoviruses used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

| Targeting strategy | Virus name | Abbreviation | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type (non targeted) | Adenovirus serotype 5 | Ad5-CMV-luc | Encodes adenovirus serotype-5 fiber with cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter driving luciferase (luc) transgene expression | |

| Transductional targeting | Adenovirus-RGD | Ad5-RGD-Luc | Integrin binding peptide (arginine–glycine– aspartate) is attached to the adenovirus fiber HI loop to expand tropism to integrin expressing cells | [36] |

| Adenovirus sigma | Ad-sigma-luc | Encoding the wild type Ad5 fibers and the sigma-1 protein which is a reovirus attachment protein that can infect cells expressing sialic acid or junction adhesion molecule-1 (JAM-1) | [131] | |

| Adenovirus 5/3 | Ad5/3-luc | Ad-5 fiber knob has been replaced by that of adenovirus serotype-3 to redirect binding to the putative Ad-3 receptors CD80, CD86 or CD46. | [132] | |

| Transcriptional targeting | Adenovirus-survivin | Ad-survivin-luc | Transgene expression is derived by surviving promoter | [133] |

| Adenovirus-secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor | Ad-SLPI-luc | Transgene expression is derived by SLPI promoter | [134] | |

| Adenovirus-heparanase | Ad-heparanase luc | Transgene expression is derived by heparanase promoter | [135] |

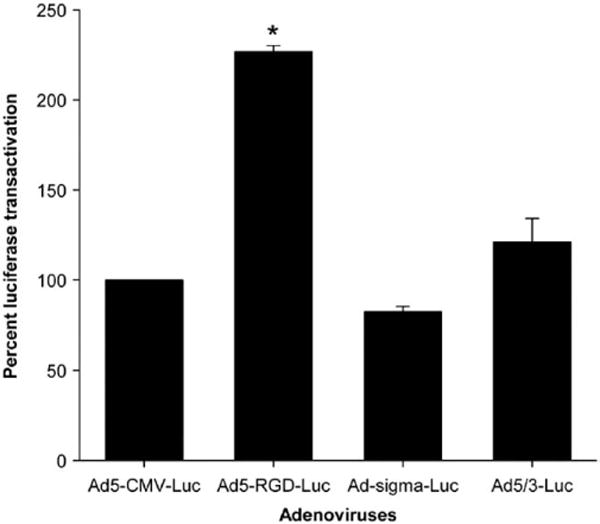

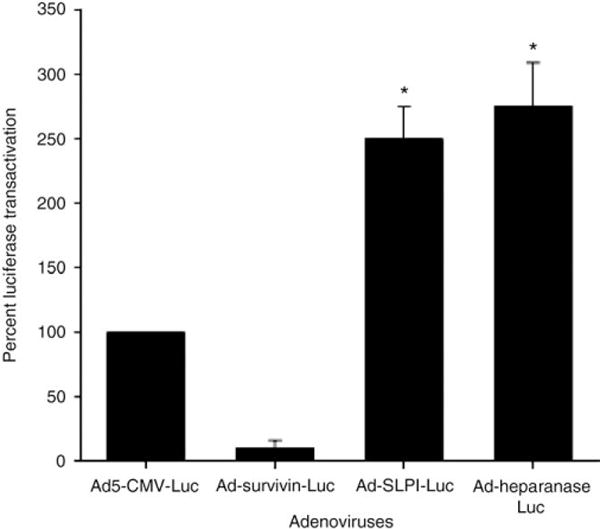

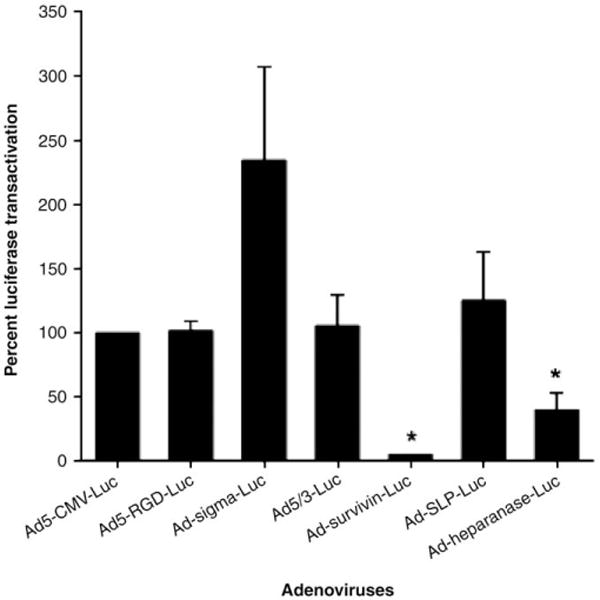

Targeted adenoviruses were used to transfect primary human endometriosis cells as target cells or human liver tissue slices taken from seronegative donors before transplantation into recipients (Fig. 13). All adenoviruses used were replication deficient viruses with a luciferase reporter gene in the E1 region under the control of corresponding promoters. Gene transfer and expression activity of each virus was reflected by its luciferase transactivation level.

Fig. 13.

Evaluation of modified adenovirus transduction efficiency in normal human liver cell line (THLE3) at 10 PFU/cell. Luciferase activities (RLU) were normalized to the protein content, and expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM) of 4 separate experiments, and plotted as percentage of corresponding Ad5-luc activity. a,c; indicate significant difference from Ad5 (P<.001 and P<.01, respectively) [108].

The results have shown that among transductionally targeted adenoviruses, Ad5-RGD-luc achieved the highest reporter gene transfer efficiency (Fig. 14). Among transcriptionally targeted adeno-viruses, Ad-SLPI-luc and Ad-heparanase-luc achieved significantly higher reporter gene expression than Ad5-luc or the wild type (Fig. 15). In the liver tissues, Ad-survivin-luc and Ad-heparanase-luc achieved significantly lower reporter gene expression levels as compared to the Ad5-luc (Fig. 16).

Fig. 14.

Luciferase transactivation in endometriosis cells mediated by transductionally targeted adenoviruses at MOI of 10 PFU/cell.

Fig. 15.

Luciferase transactivation in endometriosis cells mediated by transcriptionally targeted adenoviruses at MOI of 10 PFU/cell.

Fig. 16.

Luciferase transactivation in liver tissues mediated by transductionally and transcriptionally targeted adenoviruses at MOI of 10 PFU/cell.

We concluded from this study that Ad-heparanase-luc has high gene expression level in endometriosis cells but minimal levels in liver tissues so it achieves an “endometriosis on, liver off” phenotype and can work as an excellent vector for gene therapy of endometriosis.

2. Conclusions and future directions

Current nonsurgical management options for uterine leiomyoma and endometriosis are limited. Gene-based therapeutic approaches may represent future viable alternatives, especially for women who want to preserve their fertility. Further understanding and uncovering of the genetic and environmental mechanisms responsible for uterine leiomyoma and endometriosis will aid in designing more targeted and specific gene therapy protocols. Additional research is needed to improve our understanding of the genetic and cellular mechanisms of these common gynecologic disorders. Dominant negative ER (delivered via an adenovirus) as well as Ad-HSV-tk/GCV provided two promising approaches to induce apoptosis and eventually shrink leiomyoma, and these approaches could conceivably constitute the basis for future clinical trials. Several other biological pathways in leiomyoma represent potential targets for gene therapy application. For instance, several lines of evidence have suggested that the apoptotic mechanisms are downregulated in leiomyoma cells compared with normal myometrium [136]. Thus, gene therapy of leiomyoma can be executed by switching on the apoptosis mechanism through both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways (by delivering apoptosis-inducing ligands, such as TNF, TRAIL, and FasL; or by delivering pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, such as Bax or active caspase molecules). In endometriosis, in addition to estrogen dependency, angiogenesis, which is essential for endometriosis growth, is driven by different growth factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and platelet-derived endothelial growth factor (PDGF)[137–140]. Each of these angiogenic factors represents a potential gene therapy target.

To optimize gene therapy of leiomyoma and endometriosis, the expression of the transgene should be restricted exclusively to target tissues. Selective expression of transgenes in the pathological tissues can be achieved by transductional and/or transcriptional targeting. For transcriptional targeting, however, the biological uniqueness of leiomyoma or endometriosis (such as endometriosis-specific transcription factors or proteins) should be identified. This identification will allow the design of disease-specific promoters in vectors driving therapeutic gene expression only in the abnormal cells.

Generating improved delivery systems and refining the mechanisms that control gene expression will be a key step in the development of safe clinical protocols of gene therapy of benign gynecologic disorders.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Veera Rajaratnam, Director of Scientific Publications and Grant Support Core at the Center for Women’s Health Research, Meharry Medical College, for the excellent editing and dedication towards expediting the submission and revision of this manuscript. The authors gratefully acknowledge the following sources of financial support: NIH/NICHD 1 R01 HD046228-01 to AA.

Footnotes

This review is part of the Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews theme issue on “The Role of Gene- and Drug Delivery in Women’s Health — Unmet Clinical Needs and Future Opportunities”.

References

- 1.Trent RJA, Alexander IE. Clinical perspectives gene therapy: applications and progress towards the clinic. Int Med J. 2004;34:621–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2004.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaese RM, Culver KW, Miller AD, Carter CS, Fleisher T, Clerici M, Shearer G, Chang L, Chiang Y, Tolstoshev P, Greenblatt JJ, Rosenberg SA, Klein H, Berger M, Mullen CA, Ramsey WJ, Muul L, Morgan RA, Anderson WF. T lymphocyte-directed gene therapy for ADA-SCID: initial trial results after 4 years. Science. 1995;270:475–480. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavazzana-Calvo M, Hacein-Bey S, de Saint Basile G, Gross F, Yvon E, Nusbaum P, Selz F, Hue C, Certain S, Casanova JL, Bousso P, Deist FL, Fischer A. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Hendy A, Salama S. Gene therapy and uterine leiomyoma: a review, Hum. Reprod Updat. 2006;12:385–400. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Somia N, Verma IM. Gene therapy: trials and tribulations. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;2:91–99. doi: 10.1038/35038533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehier-Humbert S, Guy RH. Physical methods for gene transfer: improving the kinetics of gene delivery into cells. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:733–753. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishikawa M, Huang L. Nonviral vectors in the new millennium: delivery barriers in gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:861–870. doi: 10.1089/104303401750195836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendrie PC, Russell DW. Gene targeting with viral vectors. Molec Ther. 2005;12:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benn SI, Whitsitt JS, Broadley KN, Nanney LB, Perkins D, He L, Patel M, Morgan JR, Swain WF, Davidson JM. Particle-mediated gene transfer with transforming growth factor-beta1 cDNAs enhances wound repair in rat skin. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:894–902. doi: 10.1172/JCI119118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JM, Krieg T, Eming SA. Particle-mediated gene therapy of wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:452–459. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mir LM, Moller PH, Andrée F, Gehl J. Electric pulse-mediated gene delivery to various animal tissues. Adv Genet. 2005;54:83–114. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2660(05)54005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pack DW, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Design and development of polymers for gene delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelhady HG, Allen S, Davies MC, Roberts CJ, Tendler SJ, William PM. Direct real-time molecular scale visualisation of the degradation of condensed DNA complexes exposed to DNase I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4001–4005. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Worgall SA. Realistic chance for gene therapy in the near future. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:118–124. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1680-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnett BG, Crews CJ, Douglas JT. Targeted adenoviral vectors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1575:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00249-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier O, Greber UF. Adenovirus endocytosis. J Gene Med. 2003;5:451–462. doi: 10.1002/jgm.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huard J, Lochmuller H, Acsadi G, Jani A, Massie B, Karpati G. The route of administration is a major determinant of the transduction efficiency of rat tissues by adenoviral recombinants. Gene Ther. 1995:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Eb MM, Cramer SJ, Vergouwe Y, Schagen FH, van Krieken JH, van der Eb AJ, Borel Rinkes IH, van de Velde CJ, Hoeben RC. Severe hepatic dysfunction after adenovirus-mediated transfer of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene and ganciclovir administration. Gene Ther. 1998;5:451–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds P, Dmitriev I, Curiel D. Insertion of an RGD motif into the HI loop of adenovirus fiber protein alters the distribution of transgene expression of the systemically administered vector. Gene Ther. 1999;6:1336–1339. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bilbao R, Gerolami R, Bralet MP, Quan C, Tran PL, Tennant B, Prieto J, Bréchot CT. Transduction efficacy, antitumoral effect, and toxicity of adenovirus-mediated herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: the woodchuck animal model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2000;7:657. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vorburger SA, Hunt KK. Adenoviral gene therapy. Oncologist. 2002;7:46–59. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-1-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kay MA, Holterman AX, Meuse L, Gown A, Ochs HD, Linsley PS, Wilson CB. Long-term hepatic adenovirus-mediated gene expression in mice following CTLA4Iα administration. Nat Genet. 1995;11:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallenbeck PL, Stevenson SC. Targetable gene delivery vectors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;465:37–46. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46817-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bangari DS, Mittal SK. Current strategies and future directions for eluding adenoviral vector immunity. Curr Gene Ther. 2006;6:215–226. doi: 10.2174/156652306776359478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rein DT, Breidenbach M, Curiel DT. Current developments in adenovirus-based cancer gene therapy. Future Oncol. 2006;2:137–143. doi: 10.2217/14796694.2.1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanerva A, Hemminki A. Adenoviruses for treatment of cancer. Ann Med. 2005;37:33–43. doi: 10.1080/07853890410018934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worgall S, Wolff G, Falck-Pedersen E, Crystal RG. Innate immune mechanisms dominate elimination of adenoviral vectors following in vivo administration. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:37–44. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Li Q, Ertl HC, Wilson JM. Cellular and humoral immune responses to viral antigens create barriers to lung-directed gene therapy with recombinant adenoviruses. J Virol. 1995;69:2004–2015. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2004-2015.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim M, Zinn KR, Barnett BG, Sumerel LA, Krasnykh V, Curiel DT, Douglas JT. The therapeutic efficacy of adenoviral vectors for cancer gene therapy is limited by a low level of primary adenovirus receptors on tumour cells. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:1917–1926. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone D, Ni S, Li ZY, Gaggar A, DiPaolo N, Feng Q, Sandig V, Lieber A. Development and assessment of human adenovirus type 11 as a gene transfer vector. J Virol. 2005;79:5090–5104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5090-5104.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomko RP, Xu R, Philipson L. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3352–3356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanerva A, Wang M, Bauerschmitz GJ, Lam JT, Desmond RA, Bhoola SM, Barnes MN, Alvarez RD, Siegal GP, Curiel DT, Hemminki A. Gene transfer to ovarian cancer versus normal tissues with fiber-modified adenoviruses. Molec Ther. 2002;5:695–704. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergelson JM, Cunningham JA, Droguett G, Kurt-Jones EA, Krithivas A, Hong JS, Horwitz MS, Crowell RL, Finberg RW. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science. 1997;275:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mueck AO, Seeger H, Huober J. Chemotherapy of breast cancer-additive anticancerogenic effects by 2-methoxyestradiol? Life Sci. 2004;75:1205–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noureddini SC, Curiel DT. Genetic targeting strategies for adenovirus. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;2:341–347. doi: 10.1021/mp050045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dmitriev I, Krasnykh V, Miller CR, Wang M, Kashentseva E, Mikheeva G, Belousova N, Curiel DT. An adenovirus vector with genetically modified fibers demonstrates expanded tropism via utilization of a coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor-independent cell entry mechanism. J Virol. 1998;72:9706–9713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9706-9713.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cripe TP, Dunphy EJ, Holub AD, Saini A, Vasi NH, Mahller YY, Collin MH, Snyde JD, Krasnykh V, Curiel DT, Wickham TJ, DeGregori J, Bergelson JM, Currier MA. Fiber knob modifications overcome low, heterogeneous expression of the coxsackievirus–adenovirus receptor that limits adenovirus gene transfer and oncolysis for human rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2953–2960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercier GT, Campbell JA, Chappell JD, Stehle T, Dermody TS, Barry MA. A chimeric adenovirus vector encoding reovirus attachment protein sigma1 targets cells expressing junctional adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6188–6193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400542101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glasgow JN, Bauerschmitz GJ, Curiel DT, Hemminki A. Transductional and transcriptional targeting of adenovirus for clinical applications. Curr Gene Ther. 2004;4:1–14. doi: 10.2174/1566523044577997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vile RG, Sunassee K, Diaz RM. Strategies for achieving multiple layers of selectivity in gene therapy. Mol Med Today. 1998;4:84–92. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(97)01157-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassaux G. New cloning tools for the design of better transgenes. Gene Ther. 1999;6:307–308. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pruzan R, Chatterjee PK, Flint SJ. Specific transcription from the adenovirus E2E promoter by RNA polymerase III requires a subpopulation of TFIID. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5705–5712. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X, Wu J, Hornischer K, Kel1 A, Wingender E. TiProD: the Tissue-specific Promoter Database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj113. Database. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoff-Khalili MA, Stoff A, Rivera AA, Mathis JM, Everts M, Wang M, Kawakami Y, Waehler R, Mathew QL, Yamamoto M, Rocconi RP, Siegal GP, Richter DF, Dall P, Zhu ZB, Curiel DT. Gene transfer to carcinoma of the breast with fiber-modified adenoviral vectors in a tissue slice model system. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:1203–1210. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.11.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu ZB, Makhija SK, Lu B, Wang M, Wang S, Takayama K, Siegal GP, Reynolds PN, Curiel DT. Targeting mesothelioma using an infectivity enhanced survivin-conditionally replicative adenoviruses. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:701–711. doi: 10.1097/01243894-200609000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heise C, Kirn DH. Replication-selective adenoviruses as oncolytic agents. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:847–851. doi: 10.1172/JCI9762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hermiston T. Gene delivery from replication-selective viruses: arming guided missiles in the war against cancer. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1169–1172. doi: 10.1172/JCI9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rocconi RP, Zhu ZB, Stoff-Khalili M, Rivera AA, Lu B, Wang M, Alvarez RD, Curiel DT, Makhija SK. Treatment of ovarian cancer with a novel dual targeted conditionally replicative adenovirus (CRAd) Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haviv YS, Curiel DT. Engineering regulatory elements for conditionally-replicative adeno-viruses. Curr Gene Ther. 2003;3:357–385. doi: 10.2174/1566523034578311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCormick F. Cancer-specific viruses and the development of ONYX-015. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Freytag SO, Barton KN, Brown SL, Narra V, Zhang Y, Tyson D, Nall C, Lu M, Ajlouni M, Movsas B, Kim JH. Replication-competent adenovirus-mediated suicide gene therapy with radiation in a preclinical model of pancreatic cancer. Molec Ther. 2007;15:1600–1606. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fueyo J, Gomez-Manzano C, Alemany R, Lee PS, McDonell TJ, Mitlianga P, Shi YX, Levin VA, Yung WK, Kyritis AP. A mutant oncolytic adenovirus targeting the Rb pathway produces anti-glioma effect in vivo. Oncogene. 2000;19:2–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Russell WC. Update on adenovirus and its vectors. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2573–2604. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-11-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosenfeld ME, Curiel DT. Gene therapy strategies for novel cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin Oncol. 1996;8:72–77. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199601000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elledge RM, Alfred DC. The p53 tumor suppressor gene in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:39–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00666204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seth P. Vector-mediated cancer gene therapy: an overview. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:512–517. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.5.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wantanabe M, Nasu Y, Kashiwakura Y. Adeno-associated virus 2-mediated intratumoral prostate cancer gene therapy: long-term maspin expression efficiently suppresses tumor growth. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16:699–710. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Othman EE, Salama S, Ismail N, Al-Hendy A. Toward gene therapy of endometriosis: adenovirus-mediated delivery of dominant negative estrogen receptor genes inhibits cell proliferation, reduces cytokine production, and induces apoptosis of endometriotic cells. Fertil Steril. 2007;88:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salama S, Kamel M, Christman G, Wang H, Al-Hendy A. Gene therapy of uterine fibroids: adenovirus-mediated herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir treatment inhibits growth of human and rat leiomyoma cells. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2007;63:61–70. doi: 10.1159/000095627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wack S, Rejiba S, Parmentier C, Aprahamian M, Hajri A. Telomerase transcriptional targeting of inducible Bax/TRAIL gene therapy improves gemcitabine treatment of pancreatic cancer. Molec Ther. 2008;16:252–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cai KX, Tse LY, Leung C, Tam PK, Xu R, Sham MH. Suppression of lung tumor growth and metastasis in mice by adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of vasostatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:939–949. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Britz-Cunningham SH, Adelstein SJ. Molecular targeting with radionuclides: state of the science. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1945–1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greco O, Dachs GU. Gene directed enzyme/prodrug therapy of cancer: historical appraisal and future prospectives. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:22–36. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(2001)9999:9999<::AID-JCP1060>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tepper RI, Mule JJ. Experimental and clinical studies of cytokine gene-modified tumor cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:153–164. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.2-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Döhring C, Angman L, Spagnoli G, Lanzavecchia A. T-helper- and accessory-cell-independent cytotoxic responses to human tumor cells transfected with a B7 retroviral vector. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:754–759. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dummer R, Yue FY, Pavlovic J, Geertsen R, Döhring C, Moelling K, Burg G. Immune stimulatory potential of B7.1 and B7.2 retrovirally transduced melanoma cells: suppression by interleukin 10. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1413–1419. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalgleish A. The case for therapeutic vaccines. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:5–10. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199602000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wijayahadi N, Haron MR, Stanslas J, Yusuf Z. Changes in cellular immunity during chemotherapy for primary breast cancer with anthracycline regimens. J Chemother. 2007;19:716–723. doi: 10.1179/joc.2007.19.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abonour R, Williams DA, Einhorn L, Hall KM, Chen J, Coffman J, Traycoff CM, Bank A, Kato I, Ward M, Williams SD, Hromas R, Robertson MJ, Smith FO, Woo D, Mill B, Srour EF, Cornetta K. Efficient retrovirus-mediated transfer of the multidrug resistance 1 gene into autologous human long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2000;6:652–658. doi: 10.1038/76225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cowan KH, Moscow JA, Huang H, Zujewski JA, O’Shaughnessy J, Sorrentino B, Hines K, Carter C, Schneider E, Cusack G, Noone M, Dunbar C, Steinberg S, Wilson W, Goldspiel B, Read EJ, Leitman SF, McDonagh K, Chow C, Abati A, Chiang Y, Chang YN, Gottesman MM, Pastan I, Nienhuis A. Paclitaxel chemotherapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation and engraftment of hematopoietic cells transduced with a retrovirus containing the multidrug resistance complementary DNA (MDR1) in metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1619–1628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takebe N, Zhao SC, Adhikari D, Mineishi S, Sadelain M, Hilton J, Colvin M, Barnerjee D, Bertino JR. Generation of dual resistance to 4-hydroperoxycyclo-phosphamide and methotrexate by retroviral transfer of the human aldehyde dehydrogenase class 1 gene and a mutated dihydrofolate reductase gene. Molec Ther. 2001;3:88–96. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Farwell SE, Lees JA, White R, Parker MG. Characterization and colocalization of steroid binding and dimerization activities in the mouse estrogen receptor. Cell. 1990;60:953–962. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90343-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gronemeyer H. Transcription activation by estrogen and progesterone receptors. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:89–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wrenn CK, Katzenellenbogen BS. Structure–function analysis of the hormone binding domain of the human estrogen receptor by region-specific mutagenesis and phenotypic screening in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1998;268:24089–24098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katzenellenbogen BS, Bhardwaj B, Fang H, Ince BA, Pakdel F, Reese JC, Schodin D, Wren CK. Hormone binding and transcription activation by estrogen receptors: analyses using mammalian and yeast systems. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;47:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Danielian PS, White R, Hoare SA, Fawell SF, Parker MG. Identification of residues in the estrogen receptor that confer differential sensitivity to estrogen and hydroxytamoxifen. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:232–240. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.2.8469236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ince BA, Schodin DJ, Shapiro DJ, Katzenellenbogen BS. Repression of endogenous estrogen receptor activity in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells by dominant negative estrogen receptors. Endocrinology. 1995;136:3194–3199. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.8.7628351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ince BA, Zhuang Y, Wrenn CK, Shapiro DJ, Katzenellenbogen BS. Powerful dominant negative mutants of the human estrogen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14026–14032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chien PY, Ito M, Park Y, Tagami T, Gehm BD, Jameson JL. A fusion protein of the estrogen receptor (ER) and nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) strongly inhibits estrogen-dependent responses in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:2122–2136. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.12.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lazennec G, Alcorn JL, Katzenellenbogen BS. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of a dominant negative estrogen receptor gene abrogates estrogen-stimulated gene expression and breast cancer cell proliferation. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:969–980. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee EJ, Duan WR, Jakacka M, Gehm BD, Jameson JL. Dominant negative ER induces apoptosis in GH(4) pituitary lactotrope cells and inhibits tumor growth in nude mice. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3756–3763. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tasciotti E, Zoppe M, Giacca M. Transcellular transfer of active HSV-1 thymidine kinase mediated by an 11-amino-acid peptide from HIV-1 Tat. Cancer Gene Ther. 2003;10:64–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reid R, Mar EC, Huang ES, Topal MD. Insertion and extension of acyclic, dideoxy, and ara nucleotides by herpesviridae, human-alpha and human-beta polymerases: a unique inhibition mechanism for 9-(1,3-dihydroxy-2-propoxymethyl) guanine triphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:3898–3904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Robe PA, Princen F, Martin D, Malgrange B, Stevenaert A, Moonen G, Gielen J, Merville MP, Bours V. Pharmacological modulation of the bystander effect in the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase/ganciclovir gene therapy system: effects of dibutyryl adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate, A-glycyrrhetinic acid, and cytosine arabinoside. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:241–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palu G, Cavaggioni A, Calvi P, Franchin E, Pizzato M, Boschetto R, Parolin C, Chilosi M, Ferrini S, Zanusso A, Colombo F. Gene therapy of glioblastoma multiforme via combined expression of suicide and cytokine genes: a pilot study in humans. Gene Ther. 1999;6:330–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubsam LZ, Boucher PD, Murphy PJ, KuKuruga M, Shewach DS. Cytotoxicity and accumulation of ganciclovir triphosphate in bystander cells cocultured with herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase-expressing human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:669–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Freeman SM, Abboud CN, Whartenby KA, Packman CH, Koeplin DS, Moolten FL, Abraham GN. The “bystander effect”: tumor regression when a fraction of the tumor mass is genetically modified. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5274–5283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smythe WR, Hwang HC, Elshami AA, Amin KM, Eck SL, Davidson BL, Wilson JM, Kaiser LR, Albelda SM. Treatment of experimental human mesothelioma using adenovirus transfer of the herpes simplex thymidine kinase gene. Ann Surg. 1995;222:78–86. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199507000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mesnil M, Yamasaki H. By stander effect in herpes simplex virus-thymidine kinase/gancilovir cancer gene therapy; role of gap junctional intercellular communication. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3989–3999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Evans P, Brunsell S. Uterine fibroid tumors: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Phys. 2007;75:1503–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Surrey ES, Lietz AK, Schoolcraft WB. Impact of intramural leiomyomata in patients with a normal endometrial cavity on in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer cycle outcome. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:405–410. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)01714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chryssikopoulos A, Loghis C. Indications and results of total hysterectomy. Int Surg. 1986;71:188–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Velebil P, Wingo PA, Xia Z, Wilcox LS, Peterson HB. Rate of hospitalization for gynecologic disorders among reproductive-age women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:764–769. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00252-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Andreyko JL, Marshall LA, Dumesic DA, Jaffe RB. Therapeutic uses of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1987;42:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lefebvre G, Vilos G, Allaire C, Jeffrey J, Arneja J, Birch C, Fortier M, Wagner MS. The management of uterine leiomyomas. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2003;25:396–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marret H, Lansac J, Fourquet F. Transvaginal hysterectomy: not always the rational approach for leiomyomas. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;120:232–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kettel LM, Murphy AA, Morales AJ, Yen SSC. Clinical efficacy of the antiprogesterone RU486 in the treatment of endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:116–120. doi: 10.1093/humrep/9.suppl_1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vercellini P, Maddalena S, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Crosignani PG. Abdominal myomectomy for infertility: a comprehensive review. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:873–879. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.4.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Payne JF, Haney AF. Serious complications of uterine artery embolization for conservative treatment of fibroids. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:128–131. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Goodwin SC, Walker WJ. Uterine artery embolization for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;10:315–320. doi: 10.1097/00001703-199808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hutchins FL, Jr, Worthington-Kirsch R, Berkowitz RP. Selective uterine artery embolization as primary treatment for symptomatic leiomyomata uteri. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(99)80061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Niu H, Simari RD, Zimmermann EM, Christman GM. Nonviral vector-mediated thymidine kinase gene transfer and ganciclovir treatment in leiomyoma cells. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:735–740. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Al-Hendy A, Lee EJ, Wang HQ, Copland JA. Gene therapy of uterine leiomyomas: adenovirus-mediated expression of dominant negative estrogenreceptor inhibits tumor growth in nude mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hassan MH, Salama SA, Arafa HM, Hamada FM, Al-Hendy A. Adenovirus-mediated delivery of a dominant negative estrogen receptor gene in uterine leiomyoma cells abrogates estrogen- and progesterone-regulated gene expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3949–3957. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]