Many have called for a redesign of internal medicine training.1–7 One result of this is that residency program directors have questioned the utility of traditional scheduling models with a weekly continuity clinic that conflicts with residents' inpatient rotations and duties. In fact, the Residency Review Committee for Internal Medicine has now mandated that programs “must develop models and schedules for ambulatory training that minimize conflicting inpatient and outpatient responsibilities.”8 Residency programs with large ambulatory training components (eg, primary care, internal medicine, family medicine) have traditionally allowed for such focused practice in ambulatory settings.

Numerous internal medicine residency programs have adopted scheduling models that alternate blocks of traditional inpatient rotations with dedicated ambulatory blocks. The first report of such a model was a “4 + 1” model.9 Since then, dozens of programs have used variations on this theme, including 3 + 1, 4 + 2, and 6 + 2 models, and hybrids thereof.10,11 Given the number of variations, we refer to such schema as “X + Y” models, where “X” refers to the inpatient rotations, and “Y” refers to designated ambulatory blocks.

All of the authors have extensive experience in crafting these schedules. Two of the authors (M.S. and S.Y.) have developed such schedules for more than a dozen internal medicine programs and a pediatrics program. These schedules, and the programs that use them, have several common themes. In addition, internal medicine and pediatrics residencies appear to have considerable overlap in educational issues and priorities.12 Given the growing interest in X + Y models, we thought it important to share some of our insights to help residency programs that are planning to restructure their educational curricula in this manner.

Crafting an X + Y Schedule

Preliminary Efforts

Although not an exhaustive list, the table outlines a list of questions that programs have used to guide their early transformation work. The questions assess for “readiness for change” and can be helpful in starting the local conversation about models. Transformation to an X + Y model involves significant scheduling and cultural changes that affect attending physicians, residents, and other health care professionals and staff. Ideally, planning should commence a year before the “go-live” date to allow for appropriate preparation and budgeting.

TABLE.

Questions to Consider When Choosing/Constructing an X + Y Template

The next step is determining the optimal “X” and “Y.” These choices depend on residency size, educational and service priorities, continuity clinic capacity, and the number of residents that can be relieved from inpatient duties at a given time (ie, 20% for a 4 + 1 system). Off-service residents rotating on medicine or pediatric services, rotations on other services, residency tracks, and combined programs (eg, medicine-pediatrics) may also affect the choice of X and Y.

Early brainstorming exercises with faculty, staff, and residents allow for frontline input, promote buy-in, and facilitate consideration of important issues for the given setting. As the X + Y concept is being discussed, one should concomitantly construct the schedule. This allows for concrete demonstrations to stakeholders of how the change will affect them and allows for their input.

The transition to an X + Y model provides programs with opportunities to enhance current rotations, eliminate rotations with marginal educational benefit, prioritize changes to enhance educational or patient care quality, or develop new rotations. The program can then determine the number of teaching services and the optimal team structures.

Constructing the Master Template

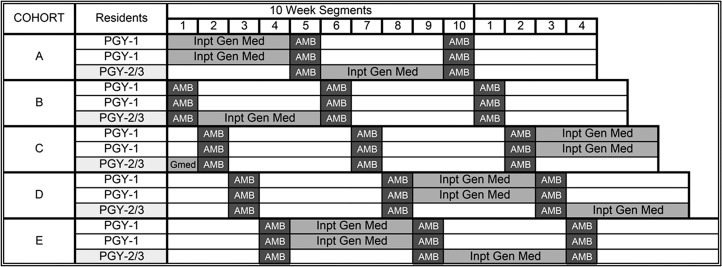

Once X and Y have been determined, residents are divided into cohorts. For X + 1 templates, X + Y groups are required (ie, a 4 + 1 system will need 4 + 1, or 5, cohorts). For X + 2 models, (X + Y)/2 cohorts are required (ie, a 4 + 2 model will require (4 + 2)/2, or 3, cohorts). Each cohort should have similar numbers of residents from each postgraduate year to minimize variations in future academic years. For programs with multiple continuity clinic sites, ideally members from each site need to be represented in each cohort. Cohorts are then staggered to ensure a resident presence during each ambulatory block. figure 1 illustrates the basic template structure for a 4 + 1 model.

FIGURE 1.

The 4 + 1 Schedule Template Format—Initial Transition Stagger

Abbreviation: AMB, 1 ambulatory week.

Figure modified from Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP. The 4:1 Schedule: A Novel Template for Internal Medicine Residencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):541–547.9

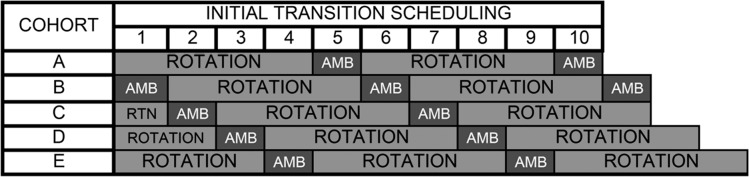

Use of an electronic spreadsheet to construct the schedule allows for a visual depiction. Counting functions and conditional formatting can be used to signal when inpatient teams are adequately populated or when there are deviations from the accreditation standards, such as too much time spent in critical care. To fill in the template, one starts with the highest-priority rotations (ie, rotations requiring a consistent team structure). figure 2 illustrates how to populate an inpatient medicine service of 1 resident and 2 interns in a 4 + 1 model. Populating resident teams using members from multiple cohorts allows for overlapping of team members. This enhances care transitions by preventing the entire team from rotating off the service at the same time.

FIGURE 2.

The 4 + 1 Schedule Template Format—Core Rotation General Internal Medicine

Abbreviations: PGY, postgraduate year; Inpt Gen Med, inpatient general internal medicine; AMB, 1 ambulatory week.

Figure modified from Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP. The 4:1 Schedule: A Novel Template for Internal Medicine Residencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):541–547.9

Once higher-priority rotations are scheduled, lower-priority rotations, electives, and vacations can be added. If appropriate counters are set, holes in the schedule can be identified and filled. For combined programs (eg, medicine-pediatrics), advance planning is required to allow residents to move between their core programs.

An anonymous master schedule can first be constructed and then later “back-filled” with specific residents. Initially, most programs construct yearly schedules, but once programs gain familiarity, schedules can span several years. This allows programs to forecast future scheduling holes and potential deviations from accreditation standards.

If there is a need to meet specific “Detail” program requirements (eg, “At least one-third of the residency training must occur in the ambulatory setting”8), programs can make additional accommodations to the “X” blocks, such as adding ambulatory subspecialty experiences to inpatient rotations.

Constructing the Ambulatory Block

Once the master schedule is constructed, the ambulatory block is developed. Block structure is influenced by the number of continuity clinics desired, the capacity of clinics to accommodate residents, faculty availability, the availability of ambulatory subspecialty opportunities, and the desire to create new experiences. Each ambulatory week is divided into 10 half-day sessions. The number of continuity clinic sessions must be sufficient to fulfill residency program requirements and goals. The remaining sessions may include didactic sessions, administrative time, urgent care sessions, or rotations through various clinics.

Clinic faculty are generally scheduled to precept on specific half-days. Many programs have clinic models in which faculty and residents “co-nest” in the same practice. This allows faculty to serve as team leaders of resident care teams that care for specific patient panels. Faculty can also serve as anchors for patient continuity while providing educational continuity to the residents. Some programs use a hybrid model with core clinic faculty linked to specific care teams and “drop-in” faculty. This allows faculty with other administrative or clinical roles to precept and helps diversify resident education.

Continuity of care in residents' patient panels is an important consideration, especially between ambulatory blocks. Programs must develop cross-coverage protocols that allow residents in the clinic to provide care for patients whose residents are not on their ambulatory block. If patients must see a covering resident, this patient encounter should ideally be overseen by the faculty leader of the care team. In addition to traditional measures of patient care (ie, percentage of time that patients see their assigned residents), it may be helpful to consider other continuity measures such as care team continuity and continuity for patients with chronic conditions. This allows for more specific assessments of continuity.

Implementing the Change

The process of planning, adjusting, and implementing an X + Y schedule ideally takes 1 year, but some programs have done it in less time. The popularity of these models and residents' familiarity with them seems to speed buy-in and change. Almost all programs have chosen to implement these changes at the beginning of an academic year, which offers logistic advantages. Programs (and residents) are also more comfortable with changes at this juncture.

Conclusion

Use of X + Y models is an increasingly popular approach to reduce conflict and enhance ambulatory education and focus. They have been used for the past 6 years in internal medicine programs, and the same forces that prompted their implementation in internal medicine are driving changes in pediatrics training. Use of X + Y models helps answer the call for residency redesign and provides a more balanced training environment for learners. To date, there are no data to show that X + Y models result in better learning, and research is needed to assess their outcomes on learning, patient care, and residents and learning satisfaction. Although there are always unique local challenges in changing one's training model, we believe the common basic tenets of construction and implementation laid out here will help other programs make these improvements.

Footnotes

Marc Shalaby, MD, is Program Director, Internal Medicine-Primary Care Residency, and Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania; Sandra Yaich, MEd, C-TAGME, is Education Associate, American Board of Internal Medicine; John Donnelly, MD, is Associate Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency, Christiana Care Health System, and Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics, Jefferson Medical College; Ryan Chippendale, MD, is Assistant Professor of Medicine, Section of Geriatrics, Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine; Maria C. DeOliveira, C-TAGME, is Director of Education Administration, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital; and Craig Noronha, MD, is Associate Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency, and Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Meyers FJ, Weinberger SE, Fitzgibbons JP, Glassroth J, Duffy FD, Clayton CP, et al. Redesigning residency training in internal medicine: the consensus report of the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Education Redesign Task Force. Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1211–1219. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159d010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine. Fitzgibbons JP, Bordley DR, Berkowitz LR, Miller BW, Henderson MC. Redesigning residency education in internal medicine: a position paper from the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):920–926. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(5):103–111. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmboe ES, Bowen JL, Green M, Gregg J, DiFrancesco L, Reynolds E, et al. Reforming internal medicine residency training: a report from the Society of General Internal Medicine's Task Force for Residency Reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1165–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinberger SE, Smith LG, Collier VU. Education Committee of the American College of Physicians. Redesigning training for internal medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):927–932. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MedPAC. Report to the Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Chapter 4: Graduate medical education financing: Focusing on educational priorities. 2010. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/Jun10_Ch04.pdf?sfvrsn=0. Accessed September 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen JL, Salerno SM, Chamberlain JK, Eckstrom E, Chen HL, Brandenburg S. Changing habits of practice: transforming internal medicine residency education in ambulatory settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1181–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Internal Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013-PR-FAQ-PIF/140_internal_medicine_07012013.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP. The 4:1 schedule: a novel template for internal medicine residencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(4):541–547. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00044.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoskote S, Mehta B, Fried ED. The Six-Plus-Two Ambulatory Care Model: a necessity in today's internal medicine residency program. J Med Educ Persp. 2012;1(1):16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shalaby M, DeOliveira MC, Noronha C, Zitnay R. How to implement an X+1 scheduling system in your residency program. Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Insight. 2013;11(2):10–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Task Force on the Future of Pediatric Education. The future of pediatric education II. Organizing pediatric education to meet the needs of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults in the 21st century. A collaborative project of the pediatric community. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1, pt 2):157–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]