Abstract

Background

Residents have a critical role in the education of medical students and have a unique teaching relationship because of their close proximity in professional development and opportunities for direct supervision. Although there is emerging literature on ways to prepare residents to be effective teachers, there is a paucity of data on what medical students believe are the attributes of successful resident teachers.

Objective

We sought to define the qualities and teaching techniques that learners interested in internal medicine value in resident teachers.

Methods

We created and administered a resident-as-teacher traits survey to senior medical students from 6 medical schools attending a resident-facilitated clinical conference at McMaster University. The survey collected data on student preferences of techniques employed by resident teachers and qualities of a successful resident teacher.

Results

Of 90 student participants, 80 (89%) responded. Respondents found the use of clinical examples (78%, 62 of 80) and repetition of core concepts (71%, 58 of 80) highly useful. In contrast, most respondents did not perceive giving feedback to residents, or receiving feedback from residents, was useful to their learning. With respect to resident qualities, respondents felt that a strong knowledge base (80%, 64 of 80) and tailoring teaching to the learner's level (83%, 66 of 80) was highly important. In contrast, high expectations on the part of resident supervisors were not valued.

Conclusions

This multicenter survey provides insight into the perceptions of medical students interested in internal medicine on the techniques and qualities that characterize successful resident teachers. The findings may be useful in the future development of resident-as-teacher curricula.

What was known

Residents play a critical role in medical student education through near-peer teaching in clinical and didactic contexts.

What is new

Students value a good knowledge base and practical approaches to teaching from resident instructors.

Limitations

Students may have interpreted terms different from what the researchers intended; respondents were interested in internal medicine, which limits generalizability.

Bottom line

Learners highly rate practical teaching with take-home points, and prefer a supportive learning environment. The findings could inform resident-as-teacher programs.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument used in the study.

Introduction

Residents play a critical role in the education of junior learners. Medical students spend significant time with residents in both a clinical and educational context, often more time than they spend with faculty.1,2 As much as a third of medical students' knowledge can be attributed to resident teachers in self-reported surveys.2 Residents are responsible for teaching a broad range of knowledge and skill sets, from pathophysiology to bedside clinical teaching, and contribute greatly to the “informal curriculum” to develop students' interpersonal skills and professionalism.3–5 Studies also have demonstrated that faculty support the importance of resident teachers and feel that teaching is a fundamental responsibility of residents.6 Huynh and colleagues7 demonstrated that students who perceived the resident teaching as high quality also indicated higher satisfaction with their clerkship rotations. Studies have linked student satisfaction with resident teachers to career choices in that discipline.8 Finally, the residents' role in teaching medical students is enshrined in the competency frameworks of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education4 and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.9

Students perceive resident teachers as contributing to their knowledge and skill development, and view residents as being highly important to their learning experience.10,11 Resident teachers offer unique, but complementary, aspects to medical students' knowledge that is derived from their contact with faculty. Residents also hold a distinct role that differs from the role of faculty, because of their proximity in training to senior medical students. As a result, residents act as near-peer mentors who relate to students and identify knowledge, skill, or attitude gaps and, as such, facilitate learning in multiple domains.3,6

Despite the emphasis on development of competency in teaching by educational stakeholders, residents' preparation for that role is variable. A study by Zabar et al12 addressed the assessment of resident teacher competencies, including instructional skills that were broadly defined and evaluated from student, resident, and faculty perspectives. This showed that despite recognition of the importance of resident teachers, knowledge on what contributes to their success is lacking. As resident-as-teacher curricula are emerging, our study aimed to elicit the attributes and teaching techniques that characterize successful resident teachers from a student perspective.

Methods

Survey and Participants

We surveyed senior medical students from each of the 6 medical schools across Ontario, Canada, who were attending a weekend conference in clinical internal medicine, featuring resident-delivered, small group, interactive teaching sessions.

Students completed a questionnaire at the end of the conference. Verbal instructions were given to respondents that the survey was intended to elicit students' perceptions of resident teaching in general. Survey questions were developed following a literature search examining current understanding of resident-as-teacher domains. Techniques were defined as methods of teaching or educational strategies that a resident could explicitly choose to employ. Qualities were defined as professional or personal attributes or abilities of the resident (ie, skills as opposed to behaviors). Individual terms were not further defined to avoid leading the participant and thereby generating potential response bias. Teaching environment (clinical versus classroom) was not specified.

Ethics approval was obtained by the Faculty of Health Sciences/Hamilton Health Science Research Ethics Board.

The survey was reviewed for clarity and content by 6 local internal medicine residents, 2 local medical education experts, and 2 resident educational leaders. All questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale with anchors (“Not useful” to “Highly useful” for techniques, “Not important” to “Highly important” for qualities). Statistical analysis of data and confidence intervals (CI) were performed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Data were received from medical students across the province of Ontario, Canada. Of 90 participating students, 80 (89%) responded.

Of those surveyed, 45% (36 of 80) were students from McMaster University, 22% (18 of 80) from the University of Western Ontario, 18% (14 of 80) from Queens University, 8% (6 of 80) from the University of Ottawa, 5% (4 of 80) from the University of Toronto, and 2.5% (2 of 80) from the Northern Ontario School of Medicine. Twenty-five percent (20 of 80) of the respondents were in their third year of medical school, and 30% (24 of 80) were in their fourth year. All respondents had prior exposure to resident teachers.

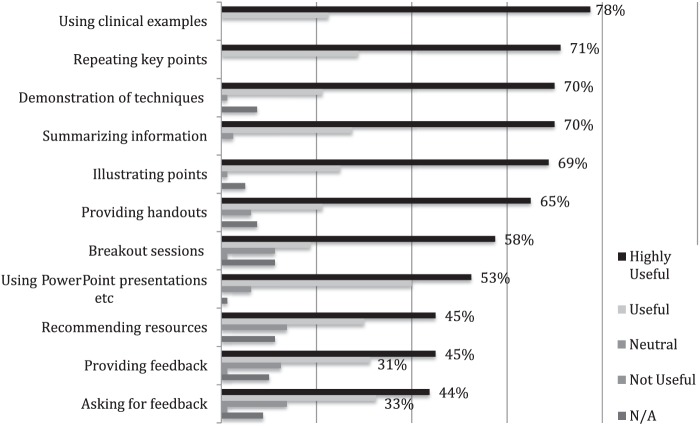

Resident Teaching Techniques

figure 1 shows the preferences of senior medical students toward resident teaching techniques. The techniques that received the highest rankings for usefulness included “Use of clinical examples” (78%, 62 of 80), “Summarizing information” (79%, 63 of 80), “Demonstration of techniques” (70%, 56 of 80), and “Illustrating points” (69%, 55 of 80).

FIGURE 1.

Resident Teaching Techniques

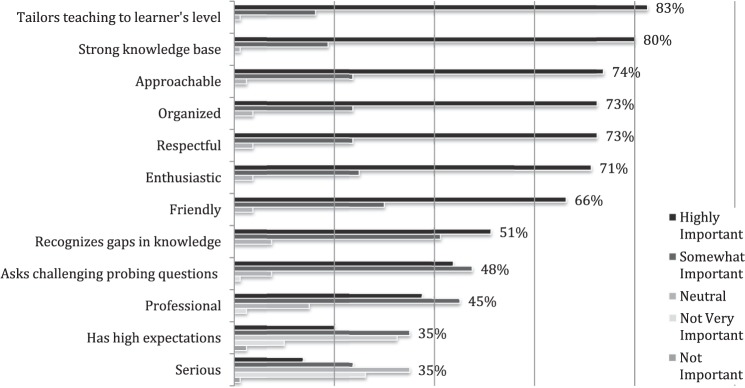

Resident Teacher Qualities

figure 2 illustrates medical student preferences in resident teacher qualities. Teacher attributes considered important to student learning by a high percentage of respondents included “Tailors teaching to the learner's level” (82%, 66 of 80), “Strong knowledge base” (80%, 64 of 80), and “Resident approachability, respectfulness, organization, and enthusiasm” (70%, 56 of 80). Only 44% (35 of 80) of students ranked “Asking challenging probing questions” as highly important, 20% (16 of 80) ranked “Has high expectations” as being important, and 14% (11 of 80) ranked a resident being “Serious” as being important.

FIGURE 2.

Resident Teacher Qualities

Discussion

Our findings showed senior medical students value resident teachers who provide clear, take-home teaching points. Teaching techniques that facilitate that goal, such as the use of clinical context, repetition of key points, summarizing information, demonstrating techniques, and using illustrations where applicable, were valued highly by students and indeed represent effective teaching techniques to be used when teaching in any environment.

Several studies have examined the qualities of faculty teachers, but the literature examining those of residents is sparse. Our findings are consistent with the literature on characteristics of good faculty teachers: Students value faculty who are supportive, inspiring, and communicate well.13 The results also corroborate the findings of earlier research showing that students value the ability to promote understanding14 and prefer a supportive learning environment.15

The finding that professionalism was not ranked as being highly important to their learning by most students may be due to several factors. Studies have demonstrated that professionalism is best learned and appreciated in long-term, context-based experiences.16–18 Additionally, the term professional was not explicitly defined on the survey and was intentionally left to interpretation by the students. We hypothesize that students may have interpreted professional as being negative, rather than positive, because it distances the resident from the student and reduces the near-peer nature of the interaction, an inherent asset of the resident as teacher.16 We believe this finding highlights the challenge in defining and demonstrating professionalism and the importance of further study of this topic in the medical student population. Furthermore, the use of challenging, probing questions, although a commonly used technique in medical education, was not rated as highly important by our survey respondents. We speculate that some students may find that technique intimidating and thus detractive from the learning experience. Alternately, the phrase challenging probing questions may have been interpreted by some respondents as intimidating.

Finally, we found that resident-delivered feedback was important to only a few students, consistent with our finding that students did not rate resident feedback as important.15 This may indicate that residents do not always deliver accurate or useful feedback, or that students may have had limited understanding of the meaning of feedback as phrased in our question. Many students equate feedback to evaluation, rather than to performance improvement. Future studies should explore student perception of the value of feedback if it is clear that residents are not providing formal, graded evaluation.

Our study has several limitations that may affect the generalizability of our results. The conference-based setting of the survey biased our sample toward highly motivated learners with a preference for internal medicine, introducing sampling bias. It is possible that students interested in other fields, such as procedural-based specialties, would have different views. Moreover, nearly half of our respondents originated from a single institution, McMaster University, which hosted the conference. The survey was developed by internal medicine physicians, which may have introduced further bias in the techniques and qualities students were asked to rank. Finally, survey respondents may have had varied interpretations of the terms used in our questions, which may have differed from those intended by the authors. Further testing in a wider scope, across multiple disciplines outside of internal medicine or longitudinal context, is needed to produce results that are more generalizable. Finally, senior medical students' perceptions may not reflect the true importance of different educational techniques and skills. Future research will need to determine whether the themes we found in an internal medicine–oriented student population persist across different settings and to explore the relationship between “great” resident teaching and student academic success.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that senior medical students preferred resident teachers who highlight key teaching points and tailor teaching to the learner's level. Learners rated practical teaching approaches with take-home points highly and expressed a preference for a supportive learning environment. The finding may be useful in the future development of resident-as-teacher curricula.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Eleanor Pullenayegum for her statistical support and guidance.

Footnotes

Lindsay Melvin, MD, is a Fourth-Year Resident in General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Zain Kassam, MD, MPH, FRCPC, is Chief Medical Officer, OpenBiome and Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Andrew Burke, MD, FRCPC, is Independent Dialysis Fellow, Western University; Parveen Wasi, MD, FRCPC, is a Professor, and currently serving as Director of Faculty Development, Department of Medicine, McMaster University; and John Neary, MD, FRCPC, is Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, McMaster University.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tonesk X. The house officer as teacher: what schools expect and measure. J Med Educ. 1979;54(8):613–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bing-You RG, Sproul MS. Medical students' perceptions of themselves and residents as teachers. Med Teach. 1992;14(2–3):133–138. doi: 10.3109/01421599209079479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordley DR, Litzelman DK. Preparing residents to become more effective teachers: a priority for internal medicine. Am J Med. 2000;109(8):693–696. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. July 2007. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed on September 13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensinger LD, Meah YS, Smith LG. Resident as teacher: the Mount Sinai experience and a review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2005;72(5):307–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. The perceptions of attending doctors on the role of residents as teachers of undergraduate clinical students. Med Educ. 2003;37(3):241–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huynh A, Savitski J, Kirven M, Godwin J, Gil K. Effects of medical students' experiences with residents as teachers on clerkship assessment. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):345–349. doi: 10.4300/JGME-03-03-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musunuru S, Lewis B, Rikkers LF, Chen H. Effective surgical residents strongly influence medical students to pursue surgical careers. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank JR, editor. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework: Better Standards, Better Physicians, Better Care. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makama JG, Ameh EA. Quality of teaching provided by surgical residents: an evaluation of the perception of medical students. Niger J Med. 2011;20(3):341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith CH, III, Wilson JF, Haist SA, Ramsbottom-Lucier M. Relationships of how well attending physicians teach to their students' performances and residency choices. Acad Med. 1997;72(10, suppl 1):118–120. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199710001-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zabar S, Hanley K, Stevens DL, Kalet A, Schwartz MD, Pearlman E, et al. Measuring the competence of residents as teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5, pt 2):530–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452–466. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owolabi MO, Afolabi AO, Omigbodun AO. Performance of residents serving as clinical teachers: a student-based assessment. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):123–126. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00130.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karani R, Fromme HB, Cayea D, Muller D, Schwartz A, Harris IB. How medical students learn from residents in the workplace: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):490–496. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulte C, Betts A, Garner K, Durning S. Student teaching: views of student near-peer teachers and learners. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):583–590. doi: 10.1080/01421590701583824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold L. Assessing professional behavior: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Acad Med. 2002;77(6):502–515. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 2010;35(7):e1252–e1266. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.789132. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.789132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]