Abstract

Background

Clinician counseling about medication can improve patient understanding and adherence. This study developed a teaching session for physician learners about medication prescribing and communication, with evaluation at the physician and patient levels.

Objective

We analyzed whether patients would perceive and report more comprehensive clinician presentation of medication information when receiving prescriptions from their physician in the intervention clinic.

Methods

We conducted a single site, prospective intervention study that included lectures, role play, an objective standardized clinical examination (OSCE), and reminders displayed in patient care areas. For physician-level assessment, pretests and posttests included a written case presentation and a OSCE. For patient-level assessment, we used a cross-sectional observational design that included study of patient recall information, and assessment of patient satisfaction before and after intervention.

Results

Twenty-seven family medicine residents and sports medicine fellows participated in the teaching session, focused on presenting patients the reasons, risks, and regimen of prescribed medication. In written testing, learners presented significantly more comprehensive information in posttests. In the OSCE (n = 14), all learners presented risks and regimen information. However, patient-level assessment showed no significant difference between before and after intervention. Notably, the covariates patient activation and satisfaction with communication both had a significant association with patient recall information.

Conclusions

Our intervention improved learner presentation of medication information. However, patient recall of the information conveyed did not change. Although physician training did not have a positive effect on patient recall, patient activation emerged as a critical influence of patients' perceptions of medication discussions.

What was known

Medication counseling is known to improve patient understanding and adherence.

What is new

An educational intervention improved the information residents and fellows provided during medication counseling evaluation, but it had no impact on measures of patient-level outcomes.

Limitations

Small sample and single specialty, single site study limit generalizability.

Bottom line

Learning about prescribing improved learner presentation of medication information but did not affect patient recall. Patient activation emerged as a key component of patients' perceptions of medication discussions.

Introduction

Clinician counseling about medication can improve patient understanding of medication instructions and adherence to instructions.1,2 However, the importance of these discussions may be overlooked because of the routine nature of prescribing. Research shows that during the average 15.9 minutes of a patient visit, only 49 seconds are used to discuss a new prescription,3 and only 33% of patients receive verbal counseling regarding the side effects of a new prescription.4 In addition to risk information, research supports presenting medication name, directions for and duration of use, and reason for the medication in prescribing discussions.5–8 Studies have shown that patients who receive less counseling about new medication are less likely to adhere to medication regimens.9,10 Medication adherence appears to be determined by patients' perceived need for the medication, patient understanding and response to side effects, and the cost of medication.5 Physicians can affect the patient's perceived need and address concerns through the prescription discussion.6

Although some physicians rely on other resources to supplement medication counseling, physician discussions regarding risks generate higher patient awareness than pharmacist counseling or written educational materials.7 Patients struggle with reading drug labels and provided instructions8,9 and prefer physicians as a trusted source of health information,10,11 specifically prescription information.12,13

This study provides evidence of a model for teaching resident physicians how to counsel patients about new prescription medication. We hypothesized that (1) family medicine residents and fellows will describe a more complete medication presentation following an educational intervention; and (2) patients who receive prescriptions following the intervention will report more comprehensive medication discussions than patients who received prescriptions prior to the intervention.

Methods

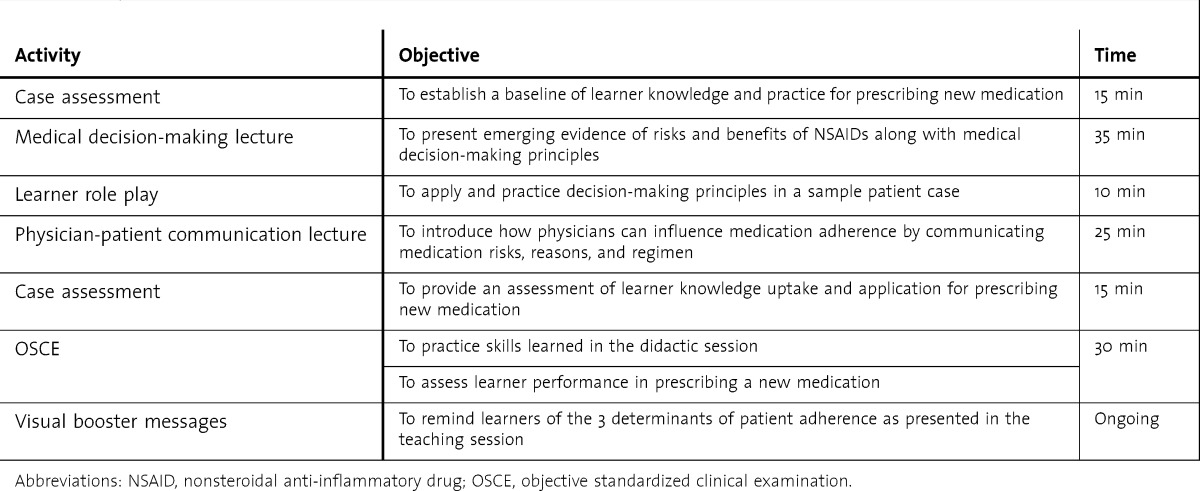

During a single session, the teaching intervention included 2 sections: medical decision making and physician-patient communication (table 1). The session combined didactic teaching and learner interaction through role play, with a decision-making section that focused on medication prescribing, including emerging evidence about the risks of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and a communication section that focused on how to present information to patients, specifically the determinants of patient adherence. In the communication presentation we included preliminary results from patient-level assessments to establish where gaps existed in current practice. The intervention was designed to address the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education's patient care and interpersonal and communication skills competencies.14

TABLE 1.

Risks, Reasons, and Regimen in Medication Discussions Teaching Intervention and Assessment

As booster messages, reminder cards (business card–sized) were posted on the computer screens of clinic rooms that read “reasons, risks, regimen.” More comprehensive 8½- × 11-inch posters describing the determinants were posted in the teaching consult room.

Learner-Level Evaluation

Prior to the teaching session learners completed 2 case assessments, which presented patient cases that might be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Learners read the case and recorded what nonpharmacologic treatments and medications they would recommend to the patient, and if they chose to prescribe medications, what they would tell the patient. For the pretest, learners completed a hypertension case and a musculoskeletal knee pain case. Following the intervention, learners completed 2 more cases on lower back pain and upper respiratory infection.

Learner responses were assessed in 2 domains. The teaching physician (sports and family medicine faculty member) rated the medication recommendations on 3 Likert-scale items (1, lowest; to 7, highest): evidence-based, safety, and efficacy. Second, 2 social scientists coded learners' responses about what they would tell patients according to the presence/absence of risks, reasons, and regimen. To assess pre-post differences, learners received 1 point for each category per case, for a score of 0 to 6.

Following the teaching session, learners were invited to participate in a 3-step objective standardized clinical examination (OSCE) to practice their skills. Learners were given a case of a 28-year-old woman presenting with headaches, and were asked to prepare for a patient encounter. Learners then consulted with a faculty member, presenting the case and discussing their recommendation just as they would when staffing cases in a standard clinic day. Lastly, learners spent up to 10 minutes presenting their medication recommendation to a standardized patient in a clinical observation room. This interaction was video recorded and transcribed.

The outcome measure of the OSCE was patient-centered communication, derived from Street and colleagues'15,16 verbal behavior coding scheme. For this study, only physician behaviors were included because the patient was a standardized patient. In previous studies, coding reliabilities on physician behavior codes have ranged from 0.64 to 0.83.17–19 Relevant to the intervention are 3 codes: rationale (physician justification for medical procedures, tests, or recommendations), risks (description that explains possible negative side effects), and instructions (provide clear how-to directions). The first author divided transcripts into utterances as the unit of analysis. Two coders then categorized physician utterances into mutually exclusive categories of the coding scheme.16 When coders disagreed, the first author reviewed the utterance with the coders to reach consensus.

Patient-Level Evaluation

Patient recruitment occurred in the waiting room of a community hospital pharmacy in the summer of 2012, for 1 week preceding the intervention and for a second 1-week period 4 weeks after the intervention. Screening was conducted verbally prior to consent and included 3 criteria: age older than 18 years, had an appointment with his or her clinician, and waiting for a new (not refill) prescription. Analysis is limited to patients who reported the name of the medication prescribed.

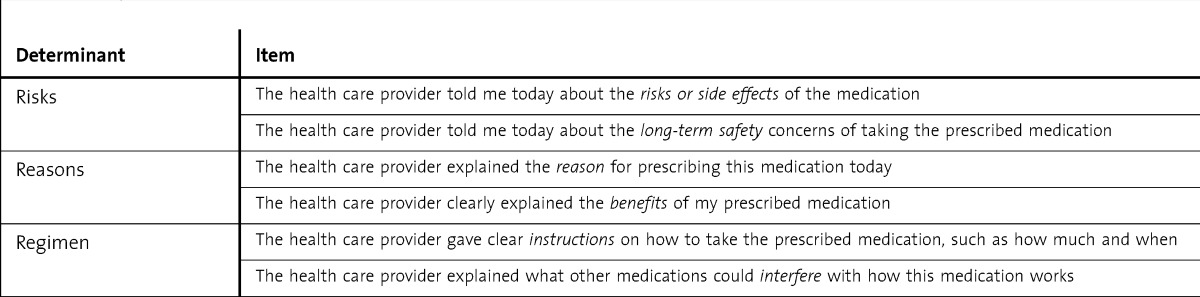

The primary outcome was patient-reported recall of the clinician's presentation of risks, reasons, and regimen in the new prescription medication discussion, measured by an index that summed 6 items related to recall of the determinants of medication adherence: risks, reasons, and regimen (R3iMeDi).20 table 2 presents the individual items and representative determinants. The index ranged from 6 to 30, where high scores indicated positive discussion.

TABLE 2.

Risks, Reasons, and Regimen in Medication Discussions Index

Two variables were included as potential covariates of medication discussions: satisfaction with communication, and patient activation. An adapted communication satisfaction scale21 assessed patient perception of clinician communication behaviors, including respect, listening, response to patient needs, and time to ask questions. Patient activation is the knowledge, skills, and confidence to manage personal health,22 and was assessed with the Patient Activation Measure.23 Participants also reported age, sex, ethnicity, education, overall health status,24 and the clinic from which the medication was prescribed.

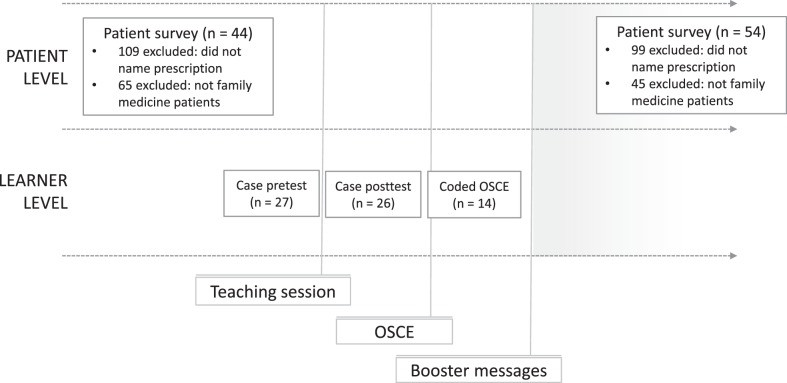

A diagram of the overall evaluation process is shown in the figure. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

FIGURE.

Timeline of Intervention and Evaluation

Abbreviation: OSCE, objective standardized clinical examination.

Quantitative analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 22 (IBM Corp). For learner-level effects, pre-post differences were assessed with paired-samples t tests. For patient-level effects, before-after intervention differences were assessed with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA).

Results

Learner-Level Effects

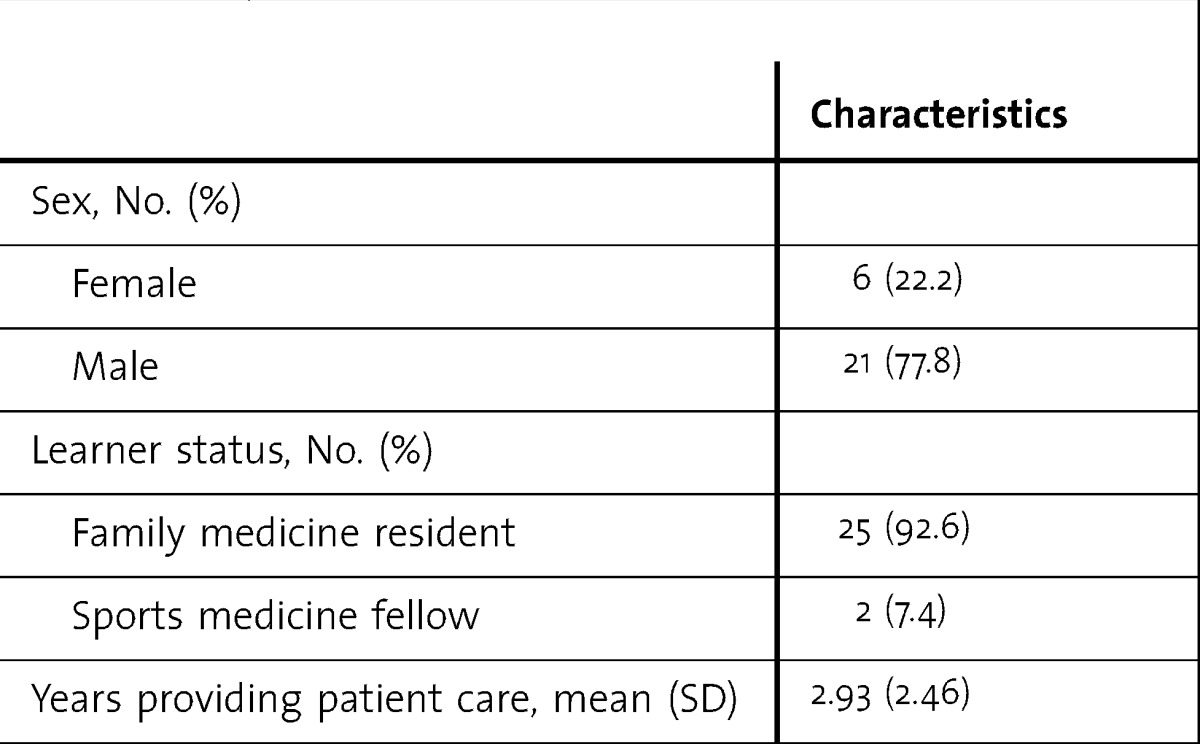

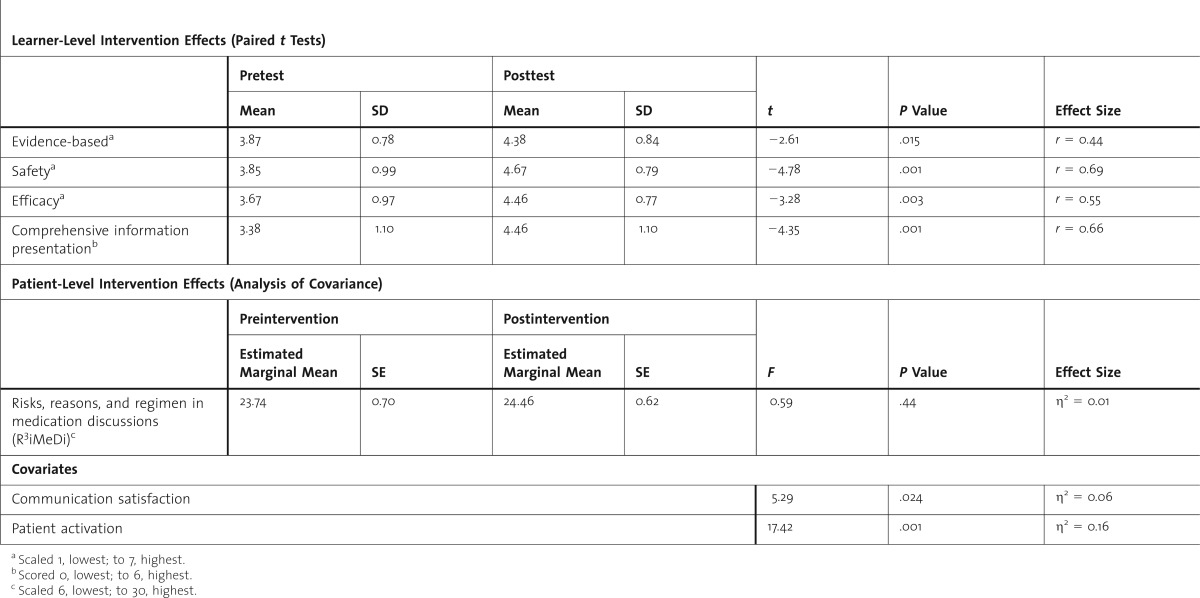

A total of 27 of 36 family medicine residents and sports medicine fellows participated in the teaching session, of which 26 (72%) completed both pretesting and posttesting. table 3 presents individual characteristics of physician participants in the educational intervention. The teaching physician assessed that in posttest, learners recommended treatments as more evidence-based, safer, and more efficacious. Means, significance, and effect sizes25 are reported in table 4. At pretest, the largest deficit in communicating those recommendations was reason for prescription, with only 33.3% (9 of 27) of learners presenting this in their open text. Both risks and regimen were presented in at least 1 of the cases by 92.6% (25 of 27) of learners. Following the intervention, learners presented significantly more comprehensive information in posttests, supporting the first hypothesis.

TABLE 3.

Individual Characteristics of Participants (N = 27) in Educational Intervention

TABLE 4.

Intervention Effects at Learner and Patient Levels

A total of 15 learners completed the OSCE; 14 consented to video recording. In the recorded OSCEs (n = 14), all physicians presented risks and regimen information. However, 6 did not provide reasons (rationale) for their prescription recommendation. Learners provided an average 1.64 (SD = 2.13) utterances of rationale, an average 4.79 (SD = 3.36) utterances of risk, and an average 8.29 (SD = 4.48) utterances of instructions.

Patient-Level Effects

Before the intervention, 101 patients volunteered to participate and could name the medication prescribed; 44 of these were patients from the family medicine clinic. After intervention, 95 patients volunteered who could name the medication prescribed; 54 of these were family medicine clinic patients. Statistical tests showed no differences between before and after groups on demographic factors.

In an ANCOVA, the independent variable was survey administration, before or after the intervention. The dependent variable was the R3iMeDi index. Patient activation and satisfaction with communication were included as covariates. Communication satisfaction and patient activation were positively related to recall of discussion (table 4). An ANCOVA was replicated for the 98 respondents from clinics other than family medicine with the same result and revealed no significant difference between the 2 time points.

Discussion

Our intervention was successful in an educational context regarding new prescription instructions, demonstrating improvement in learner medical decision making and physician-patient communication. The results also showed learners could improve further in presenting the reasons for their medication decisions. This may be attributed to the didactic session's focus on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug risk.

In contrast, for our clinical outcome measure, patient recall of physician messages, there was no change following the intervention. The difference in intervention effects at the learner and patient levels is not without precedent. In a systematic review of communication training effects, interventions demonstrated a clearer relationship improvement in physician behavior as compared with patient behavior.26 At least 3 factors may influence this gap. First, learner assessment immediately followed the intervention, whereas the patient assessment lagged by 1 month. Although we posted booster messages in clinic rooms, simple, small visual reminders may not have been enough to overcome degradation over time, particularly because it was only a single teaching session. Second, a Hawthorne effect27 likely influenced physician performance. Third, the patient assessment design made the assumption that improvements in learner performance would be reflected by overall clinic performance. Results here may show a dilution effect in which improvements in resident performance are diluted across the clinic grouping.

Although the intervention did not influence patient recall, patient activation was associated with perceptions of medication discussions. Our intervention focused only on physician education, whereas previous successful interventions included patient intervention as well, specifically distribution of a patient handout.28 This type of patient intervention may influence patient activation. The role of patient activation is also noteworthy in the context of medication taking. When patients encounter information that conflicts with medication from their provider, patient adherence decreases.29

By collecting data in the pharmacy setting, the study leverages the time period in which a patient has been exposed to the clinician's information but not yet the pharmacist's input. This allows for more accurate recall of information delivered by the physician and minimizes potential confounding factors, such as self-directed inquiry,30 pharmacist counseling,7 etc.

Our study has limits in its design and in participant factors. In the learner evaluation, use of 2 different musculoskeletal cases sought to prevent priming and retest bias; however, this difference affects pretest/posttest variability. The study is also limited by its reliance on self-reported data, allowing for patient self-selection and social desirability bias. Patient recall continues to be a challenge; however, two-thirds of patients recall the information given upon prescription.31 Because there were no external measures, such as third-party review or clinician self-assessment, it is challenging to determine the impact of findings in a broader clinical sense. Sample size and insufficient power may have contributed to the nonsignificant results for patient-level outcomes. Finally, generalizability may be limited by the single site nature of this study.32

Conclusion

Our educational intervention provides 1 model for improving learner performance in presenting medication information to patients, and it found an important relationship between patients' perceptions of medication discussions and patient activation. More inquiry is needed to determine how residents implement these teaching principles in practice and how individual patient factors may affect that implementation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lauren Cafferty for her tireless efforts in data collection. They would also like to thank Ms Cafferty and Dr Monica Schmidt for coding the transcribed encounter data.

Footnotes

Christy J. W. Ledford, PhD, is Assistant Professor, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Marc A. Childress, MD, is Staff Physician, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital; Christopher C. Ledford, MD, is Staff Physician, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital; and Heather D. Mundy, MD, is Resident Physician, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital.

Funding: This educational intervention was funded by a small grant from the Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians. The patient-level evaluation was funded by an intramural grant from Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

These results were presented at the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare, Montreal, Canada, in September 2013.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the US Army, US Air Force, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the Department of Defense at large.

References

- 1.Stevenson FA, Cox K, Britten N, Dundar Y. A systematic review of the research on communication between patients and health care professionals about medicines: the consequences for concordance. Health Expect. 2004;7(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Kravitz RL, Heritage J, Liu H, Kim S, et al. How much time does it take to prescribe a new medication. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72(2):311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris LA, Tabak ER, Gondek K. Counseling patients about prescribed medication: 12-year trends. Med Care. 1997;35(10):996–1007. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHorney CA. The Adherence Estimator: a brief, proximal screener for patient propensity to adhere to prescription medications for chronic disease. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(1):215–238. doi: 10.1185/03007990802619425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledford CJ, Villagran MM, Kreps GL, Zhao X, McHorney C, Weathers M, et al. “Practicing medicine”: patient perceptions of physician communication and the process of prescription. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(3):384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitt MR, Miller MJ, Harrison DL, Farmer KC, Allison JJ, Cobaugh DJ, et al. Communicating non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug risks: verbal counseling, written medicine information, and patients' risk awareness. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, III, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Tilson HH, Bass PF, Parker RM. Misunderstanding of prescription drug warning labels among patients with low literacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(11):1048–1055. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2618–2624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Wilson IB, Weissman J. Whom do older adults trust most to provide information about prescription drugs. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(2):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Williams BR, Cipri CS, Wenger NS. Which providers should communicate which critical information about a new medication?: patient, pharmacist, and physician perspectives. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):462–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Street RL, Gordon HS, Ward MM, Krupat E, Kravitz RL. Patient participation in medical consultations: why some patients are more involved than others. Med Care. 2005;43(10):960–969. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178172.40344.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Street RL, Millay B. Analyzing patient participation in medical encounters. Health Commun. 2001;13(1):61–73. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1301_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Adam Kelly P, Souchek J, Wray NP. Physician-patient communication following invasive procedures: an analysis of post-angiogram consultations. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(5):1015–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Street RL, Krupat E, Bell RA, Kravitz RL, Haidet P. Beliefs about control in the physician-patient relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):609–616. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon HS, Street RL, Sharf BF, Souchek J. Racial differences in doctors' information-giving and patients' participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ledford CJ, Childress MA, Ledford CC, Mundy HD. The practice of prescribing: discovering differences in what we tell patients about prescription medications. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(2):255–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheraghi-Sohi S, Bower P, Mead N, McDonald R, Whalley D, Roland M. What are the key attributes of primary care for patients?: building a conceptual ‘map’ of patient preferences. Health Expect. 2006;9(3):275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledford CJ. Exploring the interaction of patient activation and message design variables: message frame and presentation mode influence on the walking behavior of patients with type 2 diabetes. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(7):989–1000. doi: 10.1177/1359105311429204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6, pt 1):1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Cancer Institute. HINTS: Question details. http://hints.cancer.gov/question-details.aspx?qid=744. Accessed August 29, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenthal R. Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007;45(4):340–349. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernald DH, Coombs L, DeAlleaume L, West D, Parnes B. An assessment of the Hawthorne Effect in practice-based research. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(1):83–86. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarn DM, Paterniti DA, Orosz DK, Tseng CH, Wenger NS. Intervention to enhance communication about newly prescribed medications. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):28–36. doi: 10.1370/afm.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter DM, Elstad EA, Blalock SJ, DeVellis RF. Conflicting medication information: prevalence, sources, and relationship to medication adherence. J Health Comm. 2013;19(1):67–81. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.798380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hameen-Anttila K, Nordeng H, Kokki E, Jyrkkä J, Lupattelli A, Vainio K, et al. Multiple information sources and consequences of conflicting information about medicine use during pregnancy: a multinational Internet-based survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(2):e60. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarn DM, Flocke SA. New prescriptions: how well do patients remember important information. Fam Med. 2011;43(4):254–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferguson L. External validity, generalizability, and knowledge utilization. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(1):16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]