Abstract

Obesity, low-quality diet, and inactivity are all prevalent among survivors of endometrial cancer. The present review was conducted to assess whether these characteristics are associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Electronic databases, conference abstracts, and reference lists were searched, and researchers were contacted for preliminary results of ongoing studies. The quality of the methodology and reporting was evaluated using appropriate checklists. Standardized mean differences were calculated, and data were synthesized narratively. Eight of the 4385 reports retrieved from the literature were included in the analysis. Four of the 8 studies were cross-sectional, 1 was retrospective, 1 was prospective, and 2 were randomized controlled trials. Obesity was negatively associated with overall HRQoL in 4 of 4 studies and with physical well-being in 6 of 6 studies, while it was positively associated with fatigue in 2 of 4 studies. Meeting the recommendations for being physically active, eating a diet high in fruit and vegetables, and abstaining from smoking were positively associated with overall HRQoL in 2 of 2 studies, with physical well-being in 2 of 3 studies, and with fatigue in 1 of 3 studies. Improvements in fatigue and physical well-being were evident after lifestyle interventions. The findings indicate a healthy lifestyle is positively associated with HRQoL in this population, but the number of studies is limited. Additional randomized controlled trials to test effective and practical interventions promoting a healthy lifestyle in survivors of endometrial cancer are warranted.

Keywords: endometrial cancer, healthy lifestyle, obesity, physical activity, quality of life, survivors

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in the United Kingdom. Each year, more than 7000 cases are diagnosed,1,2 Endometrial cancer has one of the highest survival rates; 75% of diagnosed women are likely to survive for at least 10 years.1 Given these data, research on the survivorship population is of considerable importance.

Endometrial cancer survivors experience decreased health-related quality of life (HRQoL), primarily due to cancer and its treatment.3 Other factors, however, like lifestyle behaviors, may also play a role. Evidence from the general cancer survivorship literature suggests that meeting nutritional and physical activity recommendations is positively associated with HRQoL.4 A recent Cochrane review indicated that exercise interventions significantly improve HRQoL in cancer survivors.5 Nevertheless, there is a high prevalence of low physical activity, poor dietary quality, and obesity among endometrial cancer survivors,6 many of whom demonstrate low physical fitness levels7 and have persistent and long-term treatment effects like fatigue6 and mild bowel injury symptoms.8 These conditions and persistent treatment-related symptoms have been associated with poorer HRQoL in this population.

Despite the robust evidence regarding the effects of diet, physical activity, and obesity on endometrial cancer risk,9 data on these factors and outcomes for survivors of endometrial cancer are limited. The purpose of this review is to explore the associations of obesity (body mass index [BMI], body composition), diet (food groups, dietary patterns), and physical activity with HRQoL in survivors of endometrial cancer.

LITERATURE SEARCH METHODS

Eligibility criteria

The population of interest included survivors of endometrioid carcinoma stages I–IV.10,11 Due to differences in morphology and prognosis, clear cell or papillary serous carcinomas as well as sarcomas were excluded.12 Survivors were defined as those surviving after the end of primary or adjuvant therapy treatment with or without recurrent disease. Studies investigating the associations of obesity, diet, and physical activity with HRQoL in survivors of endometrial cancer were eligible (see Appendix S1 available in the Supporting Information for this article online). Inclusion was limited to studies that reported a measure of the effect or association between the variables and HRQoL.

Assessment of HRQoL.

HRQoL was conceptually defined as subjective assessments of physical well-being and symptoms (e.g., functional activities, fatigue, pain), social well-being (e.g., family distress, work), psychological well-being (e.g., anxiety, depression), and spiritual well-being (e.g., uncertainty, hope).13 A conceptual definition was used because there is no commonly accepted definition of HRQoL, though it is broadly accepted to be a multidimensional, self-rated measure of well-being.

The questionnaires most commonly used to assess HRQoL are the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30),14 the Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G),15 and the Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36).16 These are standardized tools, and a comparison of their characteristics is shown in Table 1. The physical, emotional, and functional subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the FACT-G are sufficiently similar to allow direct comparisons.17 The same applies to the physical functioning, emotional functioning/mental health, and pain subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and SF-36.18 The correlations between the FACT-G physical well-being score and the SF-36 physical composite score as well as between the FACT-G emotional well-being score and the SF-36 mental composite score are also strong.19 Thus, the operational definition of HRQoL included overall HRQoL, 4 well-being domains (physical, functional, emotional, and social), and 2 symptoms (fatigue and pain).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the three questionnaires commonly used to assess health-related quality of life

| Characteristic | FACT-G (27 items) | EORTC QLQ-C30 (30 items) | SF-36 (36 items) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall structure | 4 scales of well-being | 5 scales of functioning and 9 scales of symptoms | 7 scales of functioning and 1 scale of symptoms, clustered in 2 composite scores |

| Scaling | |||

| Well-being scales | Functional scales | Physical health | |

| Physical well-being (7 items) | Physical functioning (5 items) | Physical functioning (10 items) | |

| Functional well-being (7 items) | Role functioning (2 items) | Role physical (4 items) | |

| Emotional well-being (6 items) | Emotional functioning (4 items) | Bodily pain (2 items) | |

| Social/family well-being (7 items) | Social functioning (2 items) | General health (5 items) | |

| Symptoms | Cognitive functioning (items) | Mental health | |

| Fatigue (13 items)a | Symptom scales/items | Role emotional (3 items) | |

| Anemia (7 items)a | Fatigue (3 items) | Social functioning (2 items) | |

| Pain (2 items) | Mental health (5 items) | ||

| Nausea and vomiting (2 items) | Vitality (4 items) | ||

| Dyspnea, insomnia, constipation, diarrhea, appetite loss, financial difficulties (1 each) | |||

| Overall score (27 items) | Global health status/QoL (2 items) | ||

| Item delivery | Statements | Questions | Both questions and statements |

| Response options | Likert scales with 5 options | Likert scales with 4 or 7 options |

|

| Recall period | Past 7 days | Past week | Past 4 weeks |

Abbreviations: EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy–General; QoL, quality of life; SF-36, Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey.

aAdditional subscales in the FACT-G. Not counted in the overall score of FACT-G but counted in the overall score of FACIT-F (Functional Assessment for Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue) and/or FACT-An (anemia).

Identification of studies

Embase, MEDLINE via PubMed, Cochrane, and PsycINFO databases were searched from database inception until January 2014, with no language restrictions. Reference lists from included papers were scanned visually. The following websites were also included in the search: World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/ictrp/en), Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com), and ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov). To identify unpublished literature, relevant conference proceedings were searched manually, and experts were contacted for preliminary results of ongoing studies. An experienced academic librarian contributed to the search protocol (see Appendix S2 in the Supporting Information online), which included relevant terms for the following domains: diet, energy balance, body composition, physical activity, fatigue, pain, HRQoL, and physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being.

Study selection

One researcher (D.A.K.) reviewed the titles and abstracts and, subsequently, the full texts of those references that seemed to satisfy inclusion criteria. In the interest of time, authors were not contacted. The team discussed potential ambiguities before making a final decision on study inclusion. Duplicate reports of any study were regarded as a single study. Duplication was identified through sample size, authorship, and methodology, and the most appropriate data sets were selected. If data from the primary papers could not be extracted, a secondary analysis of more than 1 study was included in the analysis.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using EndNote X7 and Microsoft Excel 2011. The guidelines from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination20 were followed to generate the data extraction forms (Appendix S3 available in the Supporting Information online).

Quality assessment

Methodological quality was assessed through the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklists.21 Quality of reporting was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational studies22 and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement for clinical trials.23 Data on quality assessment of the cohorts and trials are available in Appendix S4 in the Supporting Information online.

Data synthesis.

As only 2 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were identified, the data were synthesized narratively.24 Studies were clustered primarily by outcome measures. To allow comparisons between different measurement tools and sample sizes, standardized mean differences (effect sizes) were produced by calculating Cohen’s d [d = (mean1 – mean2)/SDpooled] between nonobese (i.e., normal-weight and overweight) and obese (all categories) subjects and between those meeting guidelines (as defined in the papers) and those who did not. In order for data from Blanchard et al. (2010)25 to be included in the analysis, the obese and nonobese groups in the study were assumed to be of equal size. Fatigue and pain scales were corrected for directional differences, so that all scales have the same direction. Standardized mean differences were defined as small if d = 0.2, medium if d = 0.5, and large if d = 0.8.26

RESULTS

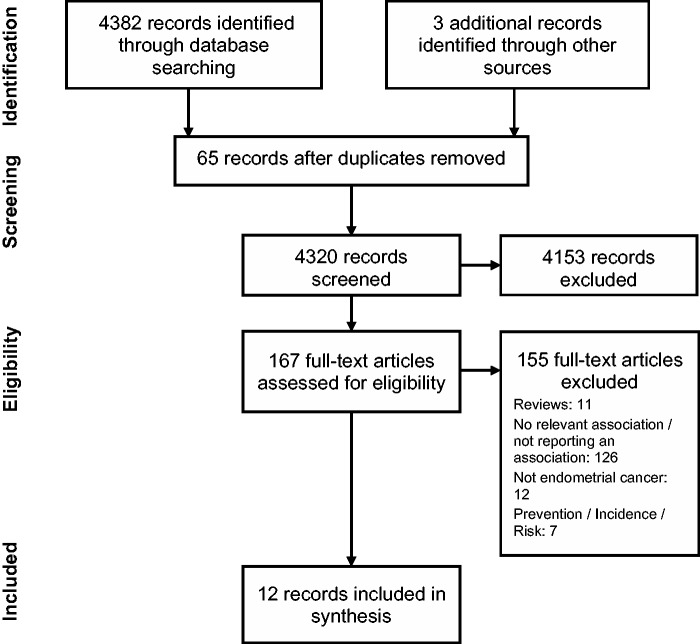

In total, 4382 records were identified. Of those, 12 reports of 8 studies were included in the final analysis. The flowchart (Figure 1) shows the study selection process and the reasons for exclusion. Four of the 8 studies were cross-sectional, 1 was retrospective, 1 was prospective, and 2 were RCTs. The evaluation tools most widely used were the EORTC QLQ-C30, the SF-36, and the FACT-G.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the literature search and selection process

Table 24,27–29 shows the 4 studies that assessed overall HRQoL. Three were cross-sectional and 1 was retrospective. Two used the SF-36, 1 the EORTC, and 1 the FACT instrument, but all showed similar patterns of improved HRQoL with lower BMI and healthier lifestyle behaviors. Specifically, 3 studies assessed the impact of BMI on HRQoL. Two of them found small to medium differences of 0.21 (0.04–0.37) and 0.29 (0.01–0.59) on HRQoL between the nonobese and obese groups,28,29 and 1 found large differences (0.75 [0.54–0.96]).27 The last study showed an improved general HRQoL with lower BMI and increased physical activity after adjusting for major confounders. Furthermore, there was a large size difference of 0.78 (0.30–1.26) in HRQoL in survivors who met the physical activity guidelines, consumed 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day, and abstained from smoking.4

Table 2.

Effects of exposure variables on health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

| Reference | Design | No. of subjects | Body composition measure | Dietary measure | Physical activity measure | HRQoL measure | Mean difference/coefficient (95% CI) | Covariates included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | Retrospective follow-up: 2.5 y | 158 | BMI extracted from medical records | N/A | N/A | EORTC QLQ-C30 | d nonobese vs obese: 0.29 (0.01–0.59) | Patient characteristics |

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | Cross-sectional | 386 | Self-reported weight & height | N/A | Modified Leisure score index from GLTEQ | Total FACT-An | d nonobese vs obese: 0.75 (0.54–0.96) | Age, marital status, education, income, disability, time since diagnosis disease stage, tumor grade, adjuvant therapy |

| BMI on QoL, β = −0.17, P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| d PA vs no PA: 0.48 (0.38–0.58) | ||||||||

| Exercise on QoL, β = 0.21, P < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | Cross-sectional | 666 | Self-reported weight & height | N/A | N/A | SF-36 | General health d nonobese vs obese: 0.21 (0.04–0.37) | Age, education, marital status, treatment, time since diagnosis, no. of comorbidities |

| BMI on general health, β = 0.50, P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| Blanchard et al. (2008)4 | Cross-sectional | 729 | Self-reported BMI | Self-reported assessed by question: How many days per week do you eat at least 5 servings of FV a day? | GLTEQL: met/did not meet ACS PA recommendation | SF-36 | Meeting PA recommendation vs not: d = 0.3 | Race, stage, education, marital status, total no. of comorbidities |

| Eating 5-a-day vs not: d = 0.1 | ||||||||

| PA and 5-a-day and no-smoking vs not meeting the guidelines: d=0.78 (0.30–1.26) |

Abbreviations: ACS PA, American Cancer Society physical activity recommendations; BMI, body mass index; d, standardized mean difference; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire; FACT-An, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy–Anemia; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy–General; FV, fruit and vegetables; GLTEQ, Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire; PA, physical activity; SF-36, Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey.

Effect sizes regarding HRQoL domains and symptoms are shown in Table 3.4,6,25,27–31 Better scores for physical well-being were universally demonstrated in the nonobese groups, but with wide variability that ranged from small to large effect sizes. Two of the 3 studies found significantly better physical well-being scores27,30 in those meeting the physical activity guidelines, with the magnitude of difference being medium to large. Marginally better scores or nonsignificant trends toward them were demonstrated for functional well-being in nonobese and physically active survivors.

Table 3.

Effect of exposure variables on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) domains and symptoms

| Reference | HRQoL measure | Standardized mean difference (95%CI); d = (mean1–mean2)/SDpooled |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (nonobese vs obese) | Physical activity (met vs did not meet guidelines) | ||

| Physical well-being | |||

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | FACT-G PWB | 0.19 (0.01–0.40) | 0.43 (0.21–0.65) |

| von Gruenigen et al. (2011)6 a | FACT-G PWB | – | 0.16 (−0.43 to 0.75)b |

| Fader et al. (2011)31 c | FACT G PWB | 0.81 (0.40–1.23) | – |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 PF | 0.45 (0.15–0.74) | – |

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | SF-36 PF | 0.76 (0.59–0.93) | – |

| Basen-Engquist et al. (2009)30 | SF-36 PF | 0.66 (0.28–1.04) | 0.86 (0.40–1.32) |

| Blanchard et al. (2010)25 | SF-36 PHc | 0.44 (0.20–0.69) | – |

| Functional well-being | |||

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | FACT-G FWB | 0.05 (−0.16 to 0.26) | 0.26 (0.04–0.48) |

| von Gruenigen et al. (2011)6 a | FACT-G FWB | – | 0.35 (−0.25 to 0.95)b |

| Fader et al. (2011)31 c | FACT-G FWB | 0.19 (−0.22 to 0.60) | – |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 RF | 0.31 (0.01–0.60) | – |

| Emotional well-being/mental health | |||

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | FACT-G EWB | 0.06 (−0.14 to 0.27) | 0.14 (−0.07 to 0.36) |

| von Gruenigen et al. (2011)6 a | FACT-G EWB | – | 0.45 (−0.15 to 1.05)b |

| Fader et al. (2011)31 c | FACT-G EWB | 0.12 (−0.28 to 0.53) | – |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 EF | 0.25 (0.09–0.42) | – |

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | SF-36 MHs | 0.12 (−0.04 to 0.29) | – |

| Blanchard et al. (2010)25 | SF-36 MHc | 0.16 (−0.09 to 0.40) | – |

| Social well-being | |||

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | FACT-G SWB | 0.20 (−0.01 to 0.41) | 0.33 (0.23–0.33) |

| Fader et al. (2011)31 c | FACT-G SWB | 0.30 (0.14–0.46) | – |

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | SF-36 SF | 0.12 (0.05–0.20) | – |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 SF | 0.25 (−0.05 to 0.54) | – |

| Fatigue | |||

| Courneya et al. (2005)27 | FACIT-F | −0.42 (−0.62 to −0.21) | −0.40 (−0.61 to −0.18) |

| von Gruenigen et al. (2011)6 a | FACIT-F | – | −0.54 (−1.14 to 0.06)b |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 F | −0.28 (−0.58 to 0.01) | – |

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | FAS | −0.34 (−0.50 to −0.17) | – |

| Basen-Engquist et al. (2009)30 | BFI | 0.04 (−0.33 to 0.41) | −0.44 (−0.89 to 0.01) |

| Pain | |||

| Basen-Engquist et al. (2009)30 | BPI | −0.11 (−0.48 to 0.26) | −0.52 (−0.97 to −0.07) |

| Smits et al. (2013)29 | EORTC QLQ-C30 P | −0.30 (−0.59 to −0.01) | – |

| Oldenburg et al. (2013)28 | SF-36 BP | −0.47 (−0.64 to 0.31) | – |

Abbreviations: BFI, Brief Fatigue Inventory; BP, bodily pain; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; EF, emotional functioning; EWB, emotional well-being; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Questionnaire; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue; FACIT-G, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–General; FAS, Fatigue Assessment Survey; FWB, functional well-being; MHc, mental health composite score; MHs, mental health score; P, pain; PF, physical function, PHc, physical composite score; PWB, physical well-being; RF, role-functional; SF, social functioning; SF-36, Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey; SWB, social well-being.

bMeeting either 5-a-day and no smoking or 150 min/wk and no smoking.

Emotional well-being was slightly better in 1 of 5 studies in nonobese subjects29 and was nonsignificantly better in the rest. There was a trend toward better emotional well-being in those who met the physical activity goals (0.14 [−0.07 to 0.36])27 and in those who met 2 of the 3 health behavior recommendations compared with those who did not (0.45 [−0.15 to 1.05]).6 Small significant differences in social well-being between BMI categories were reported in 2 of 4 studies.

Furthermore, findings for nonobese and physically active survivors showed either a nonsignificant trend or significantly lower fatigue scores of a medium effect size (0.28–0.54), apart from 1 study that reported slightly increased fatigue in nonobese subjects (0.04 [−0.33 to 0.41]).30 Finally, pain was lower in the nonobese groups, with the difference between the nonobese and the obese groups ranging from −0.11 to −0.47, and scores showing a medium size difference (−0.52 [−0.97 to −0.07]) in favor of the physically active group in 1 study.30

Data from the 2 clinical trials on lifestyle interventions for weight loss (Table 432–35) partly support the prospective, retrospective, and cross-sectional data on HRQoL domains and symptoms. Only 1 of these trials showed a significant difference in fatigue after 3 months (P = 0.008) and in physical functioning after 6 months (P = 0.048).32 However, neither of these trials was statistically powered to detect differences in quality of life, and both may suffer from selection bias, as many participants were following relatively healthy lifestyles. Their methodological quality was scored as acceptable32 or low.34

Table 4.

Health-related quality of life after lifestyle interventions

| Reference | Study characteristics | Total no. of subjects | Body composition measure | Dietary measure | Physical activity measure | HRQoL measure | Mean difference between groups at 12 mo/coefficient (95% CI) | Covariates included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| von Gruenigen et al. (2008)34; von Gruenigen et al. (2009)35 | RCT | 45 ITT | BMI measured | 3-day dietary records performed on 1 weekend and 2 weekdays at 3, 6, & 12 mo | 4-item leisure score index from Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, (classified as mild,moderate, or strenuous) | FACIT-F | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC) | Baseline measurement |

| Stage I/II endometrial cancer | Response rate: 40% | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): BMI, | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): total intake, −90 kcal; vitamin C | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): LSI, 15.8**; pedometer, NR | HRQoL | −0.14 (−0.61 to 0.33) | ||

| LI for 6 mo vs UC | Attrition rate: 16% | −0.5 kg/m2; weight, −4.9 kg* | intake, 15.6 mg; folate intake, 101.4 μg) | Physical WB | −0.10 (−0.57 to 0.38) | |||

| FU: 12 mo | Completion rate: 80% | Functional WB | −0.13 (−0.61 to 0.35) | |||||

| Type I EC: 100% | Adherence rate: 73% | Emotional WB | −0.29 (−0.77 to 0.18) | |||||

| Social WB | 0.10 (−0.38 to 0.57) | |||||||

| Fatigue | −0.15 (−0.62 to 0.32) | |||||||

| SF-36 | NR | |||||||

| McCarroll et al. (2013)32; von Gruenigen et al. (2012)33 | RCT | 75 ITT | BMI measured | Two 24-h recalls: 1 classified as FV servings/d and 1 classified as kcal/d | Four-item LSI from Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire, along with duration questions 7-day pedometer step test at baseline and 6 mo | FACT-G (assessed at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 mo) | Fatigue at 3 mo significantly different between groups, P = 0.008 | Age, time since diagnosis, stage, adjuvant treatment, comorbidities, and baseline measurement |

| Stage I/II endometrial cancer | Response rate: 19% | Body composition using DXA (NR) | Physical function at 6 mo significantly different between groups, P = 0.048 | |||||

| LI for 6 mo vs UC | Attrition rate: 21% | Biomarkers (NR) | Total FACT-G score was improved in the LI group from baseline to 3 mo (P < 0.05) and 6 mo (P < 0.001) | |||||

| FU: 12 mo | Completion rate: 78% | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): BMI, −1.8 kg/m2; weight, −4.6 kg***; waist circum., −1.6 cm* | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): total intake, −187 kcal***; FV, 0.9 servings/d*** | Effect size at 12 mo (LI–UC): LSI, 7.8 points***; minutes of PA, 89 min/wk***; pedometer, not measured at 12 mo | ||||

| Type I EC: 100% | Adherence rate: 84% |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; circum., circumference; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; EC, endometrial cancer; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue; FACT-G, Functional Assessment for Cancer Therapy–General; FV, fruits and vegetables; FU, follow-up; ITT, intention-to-treat analysis; LI, lifestyle intervention; LSI, Leisure Score Index; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Vit C, vitamin C; UC, usual care; WB, well-being.

*P < 0.05, significant compared with baseline; **P < 0.05, significant between groups; ***P < 0.001, between groups.

DISCUSSION

Both obesity and the failure to meet guidelines for healthy lifestyle behaviors were negatively associated with HRQoL. Associations were stronger for the HRQoL domain of physical well-being and a subscale measure of fatigue. Overall, the effect sizes, although limited and for which wide standard deviations were found, are of a magnitude similar to that in the general population36 and in survivors of different types of cancer, such as breast, prostate, and colorectal.4,37,38 This further strengthens the hypothesis that maintaining a healthy lifestyle by being physically active, meeting dietary guidelines, abstaining from smoking, and maintaining a healthy weight correlates with an improved quality of life in this group of cancer patients. However, as most of the studies reviewed were cross-sectional, causality cannot be inferred.

The current results are consistent with a meta-analysis of cancer survivors who demonstrated an improved quality of life following exercise interventions.5 Although a recent analysis showed that attaining desirable exercise levels might be unlikely in cancer survivors, behavioral interventions showed an improvement in aerobic capacity,39 a strong predictor of mortality.40 Given the low physical fitness levels of endometrial cancer survivors7 and findings that indicate only small changes are needed to provide substantial health benefits,41 facilitating the physical activity levels of this population is imperative. Furthermore, exercise seems to ameliorate cancer-related fatigue,42 although this type of fatigue may be driven more by dysfunctions of the central nervous system than by abnormal muscle metabolism (as in malnutrition-related fatigue).43 Further mechanistic studies can provide insight on this.

It would have been desirable, but was not possible, to establish dose-response relationships. However, many studies4,27–29 indicated a tendency toward an inverse association between unhealthy lifestyle and HRQoL assessments, which seems consistent among survivors of different types of cancer.4 No clear evidence of an association between body composition and HRQoL, or of the effects of diet on HRQoL, has been described. Objective body composition and serum biomarker measurements had been pre-specified in the protocol of the SUCCEED trial.32 A future report from the trial may provide further insight into the nutritional status of endometrial cancer survivors, given that central adiposity is a stronger predictor of mortality in women than BMI.44

Regarding weight loss, it is generally accepted that unintentional weight loss is a clear risk factor for a worse prognosis. Unfortunately, the scarcity of data does not allow firm conclusions about intentional weight loss in endometrial cancer survivors. However, valid points can be drawn from the largest trials in other cancer survivors and from the broad body of literature on obese older adults. The literature from the general obese elderly population strongly supports that HRQoL – especially physical function – and cardiometabolic risk factors will be improved by a lifestyle intervention that involves weight loss; moreover, the side effects of such an intervention are minor.45–47 The underlying mechanisms are beyond the scope of this discussion but have been previously documented.48 Evidence from cancer survivors supports the benefits for physical function following a 1-year home-based weight loss, diet-and-exercise intervention.49 Importantly, adherence to the lifestyle intervention strongly correlated with HRQoL outcomes in cancer survivors,50 and ceasing the intervention reduced the beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions.49,51 Survivors of early-stage endometrial cancer do not experience a high burden of symptoms29 and are most likely to die from cardiovascular disease long after their cancer diagnosis.52 Although the results of large-scale weight-loss interventions in breast cancer survivors are still awaited,53 these findings indicate that intentional weight loss might be beneficial in survivors of early-stage endometrial cancer, particularly if it incorporates physical activity that includes resistance training.

As far as can be determined, this is the first report of an association between HRQoL and obesity, diet, and physical activity in endometrial cancer survivors. The review was conducted following the PRISMA guidelines,54 but given the broad scope of the review, intervention and comparison criteria were not prespecified. A comprehensive search strategy was used to identify potential studies. Although the results are based only on published data, future studies should adhere to guidelines for quality of reporting. No study reported objective measures of physical activity. Most studies used self-reported, validated questionnaires, which are prone to recall and social desirability bias.

Despite the discrepancy in the scales of the HRQoL instruments – the FACT-G measures well-being, whereas the EORTC QLQ-C30 and SF-36 measure functional assessments – the similarity of most of the scales is sufficient to allow direct comparisons to be made, as indicated in the discussion of assessment of HRQoL below. The nonsignificant results in the social well-being category are not very informative, primarily because of the important differences among the instruments used to measure this scale.55 To eliminate the effects of each instrument, standardized mean differences were calculated where possible. Importantly, the observed differences are based on subjective assessments and, therefore, rely on the individual’s perceptions of the level of each scale they experience, which may vary among individuals. While Cohen’s effect sizes determine statistically significant differences, they seem to correlate well with clinical significance.56 Thus, the medium size differences in overall HRQoL, physical well-being, and fatigue may be cautiously interpreted as clinically important differences that can guide implementation of interventions and policy decisions. Even the small size differences may be important because of the large population of endometrial cancer survivors and the high prevalence of obesity and unhealthy lifestyle among them.

Findings may not be generalizable because of the lack of sociodemographic data reporting. Given the high level of education and lack of ethnic diversity among participants in studies that collected such data, the results may not apply to the broader population of endometrial cancer survivors, who are often of low socioeconomic level.1

Implications for practice and research

Future research should address the longitudinal effect of weight control, exercise, and diet after a diagnosis of endometrial cancer and should examine the potential effects on HRQoL. In light of funding constraints, HRQoL, an indicator of survival,57 could be a valuable alternative method of evaluating prognosis, but this remains to be elucidated in endometrial cancer survivors affected mostly by early-stage disease, since evidence from breast cancer survivors suggests that HRQoL is predictive of survival in advanced-stage, but not early-stage, disease.57

Interventions targeting more representative samples of cancer survivors can increase the generalizability of the findings. Behavior change can be challenging, however, due to socioeconomic and environmental barriers,58 which include restricted access to recreational facilities and the increased cost of healthier diets. Further challenges include cancer-related effects like fatigue, limited social support, lack of motivation, and uncertainty about the effects of diet.58–60 Self-monitoring, social support, practice, and rewards are effective in improving physical activity when incorporated into lifestyle interventions.61 Contrarily, the relevant effectiveness of techniques to achieve dietary change is more obscure, given the inaccuracy of dietary reporting in most trials.62 Self-efficacy about weight management improved following lifestyle interventions in survivors of early-stage endometrial32 and other cancers.63

While data are limited in this population, it is reasonable to speculate that sarcopenia, and even cachexia, could be prevalent.64 These conditions add significantly to the mortality burden of obesity.65 Accordingly, further research should extend to anthropometric indices other than BMI, like waist-to-height ratio, handgrip strength, and body composition analysis, and should also focus on the effects of resistance training and a plant-based, protein-sufficient diet. Notably, interventions should be supported by appropriate policy actions66 in order to be efficacious.

CONCLUSION

The data, while predominantly cross-sectional, indicate that overall HRQoL and physical well-being are positively correlated with adherence to lifestyle recommendations, while fatigue is negatively associated with adherence. Future RCTs should evaluate health behavior change interventions (determining the safety, frequency, duration, intensity, and delivery mode) in endometrial cancer survivors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Abir Mukherjee for his helpful comments on the literature search strategy and Prof Jane Wardle and Dr George Grimble for their invaluable comments on previous drafts of the manuscript.

Funding. Completion of this project was funded by the University College London (UCL) Grand Challenges Scheme (D.A.K.), the Department of Women’s Cancer at the UCL EGA Institute for Women’s Health, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at UCL Hospitals, London, United Kingdom. The funders had no role in the study design, the collection or analysis of data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of the article at the publisher’s website:

Appendix S1. Exposure and outcome variables

Appendix S2. Search strategy

Appendix S3. Data extraction form

Appendix S4. Quality assessment

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Intelligence Network. Outline of Uterine Cancer in the United Kingdom: Incidence, Mortality and Survival . London, UK: NCIN; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coupland VH, Okello C, Davies EA, et al. The future burden of cancer in London compared with England. J Public Health (Oxf). 2010;32:83–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Penson RT, Wenzel LB, Vergote I, et al. Quality of life considerations in gynecologic cancer. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95 (Suppl 1):S247–S257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society's SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Gruenigen VE, Waggoner SE, Frasure HE, et al. Lifestyle challenges in endometrial cancer survivorship. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Modesitt SC, Geffel DL, Via J, et al. Morbidly obese women with and without endometrial cancer: are there differences in measured physical fitness, body composition, or hormones? Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuku S, Fragkos C, McCormack M, et al. Radiation-induced bowel injury: the impact of radiotherapy on survivorship after treatment for gynaecological cancers. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1504–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Cancer Research Fund. Continuous Update Project Report. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Endometrial Cancer . London, UK: WCRF; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;105:103–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creasman WT. New gynecologic cancer staging. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:287–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felix AS, Weissfeld JL, Stone RA, et al. Factors associated with type I and type II endometrial cancer. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1851–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition . Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzner B, Bode RK, Hahn EA, et al. Equating EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G scores and its use in oncological research. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:3169–3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuenstner S, Langelotz C, Budach V, et al. The comparability of quality of life scores: a multitrait multimethod analysis of the EORTC QLQ-C30, SF-36 and FLIC questionnaires. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashing-Giwa KT, Kim J, Tejero JS. Measuring quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: preliminary assessment of instrumentation validity in a cross-cultural study. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. York, UK: University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2009. https://http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/SysRev/!SSL!/WebHelp/1_3_UNDERTAKING_THE_REVIEW.htm. Accessed November 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Critical appraisal: notes and checklists. http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/checklists.html. Updated 2011. Accessed November 10, 2013.

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328:702–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications/NS_Synthesis_Guidance_v1.pdf. Published 2006. Accessed November 1, 2013.

- 25.Blanchard CM, Stein K, Courneya KS. Body mass index, physical activity, and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences . 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Courneya KS, Karvinen KH, Campbell KL, et al. Associations among exercise, body weight, and quality of life in a population-based sample of endometrial cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldenburg CS, Boll D, Nicolaije KA, et al. The relationship of body mass index with quality of life among endometrial cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smits A, Lopes A, Das N, et al. The impact of BMI on quality of life in obese endometrial cancer survivors: does size matter? Gynecol Oncol. 2013;132:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basen-Engquist K, Scruggs S, Jhingran A, et al. Physical activity and obesity in endometrial cancer survivors: associations with pain, fatigue, and physical functioning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:288e281–e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fader AN, Frasure HE, Gil KM, et al. Quality of life in endometrial cancer survivors: what does obesity have to do with it? Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011;2011:308609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarroll ML, Armbruster S, Frasure HE, et al. Self-efficacy, quality of life, and weight loss in overweight/obese endometrial cancer survivors (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;132:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Gruenigen V, Frasure H, Kavanagh MB, et al. Survivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Gruenigen VE, Courneya KS, Gibbons HE, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention program in obese endometrial cancer patients: a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Gruenigen VE, Gibbons HE, Kavanagh MB, et al. A randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention in obese endometrial cancer survivors: quality of life outcomes and mediators of behavior change. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:17 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ul-Haq Z, Mackay DF, Fenwick E, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among adults, assessed by the SF-36. Obesity. 2013;21:E322–E327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlesinger S, Walter J, Hampe J, et al. Lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:99–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George SM, Alfano CM, Groves J, et al. Objectively measured sedentary time is related to quality of life among cancer survivors. PloS One. 2014;9:e87937 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bourke L, Homer KE, Thaha MA, et al. Interventions to improve exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:831–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Mackey JR, et al. Cardiopulmonary function and age-related decline across the breast cancer survivorship continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2530–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cramp F, Byron-Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006145 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006145.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kisiel-Sajewicz K, Siemionow V, Seyidova-Khoshknabi D, et al. Myoelectrical manifestation of fatigue less prominent in patients with cancer related fatigue. PloS One. 2013;8:e83636 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor AE, Ebrahim S, Ben-Shlomo Y, et al. Comparison of the associations of body mass index and measures of central adiposity and fat mass with coronary heart disease, diabetes, and all-cause mortality: a study using data from 4 UK cohorts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Felix HC, West DS. Effectiveness of weight loss interventions for obese older adults. Am J Health Promot. 2013;27:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N, et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:1218–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouchonville M, Armamento-Villareal R, Shah K, et al. Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:423–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waters DL, Ward AL, Villareal DT. Weight loss in obese adults 65years and older: a review of the controversy. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1054–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demark-Wahnefried W, Morey MC, Sloane R, et al. Reach Out to Enhance Wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2354–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Winger JG, Mosher CE, Rand KL, et al. Diet and exercise intervention adherence and health-related outcomes among older long-term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48:235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waters DL, Vawter R, Qualls C, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss after lifestyle intervention in frail, obese older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17:3–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC, et al. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:176–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rock CL, Byers TE, Colditz GA, et al. Reducing breast cancer recurrence with weight loss, a vanguard trial: the Exercise and Nutrition to Enhance Recovery and Good Health for You (ENERGY) Trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34:282–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN, et al. Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical research: issues, evidence and recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:2179–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:102 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin-Watt J, et al. Cancer survivors' exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: a questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology. 2013;22:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hefferon K, Murphy H, McLeod J, et al. Understanding barriers to exercise implementation 5-year post-breast cancer diagnosis: a large-scale qualitative study. Health Educ Res. 2013;28:843–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maley M, Warren BS, Devine CM. A second chance: meanings of body weight, diet, and physical activity to women who have experienced cancer. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45:232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, et al. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals' physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Avery KN, Donovan JL, Horwood J, et al. Behavior theory for dietary interventions for cancer prevention: a systematic review of utilization and effectiveness in creating behavior change. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosher CE, Lipkus I, Sloane R, et al. Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START trial: exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors' maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psychooncology. 2013;22:876–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laky B, Janda M, Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan S, et al. Pretreatment malnutrition and quality of life – association with prolonged length of hospital stay among patients with gynecological cancer: a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:232 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalyani RR, Corriere M, Ferrucci L. Age-related and disease-related muscle loss: the effect of diabetes, obesity, and other diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:819–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lobstein T, Brinsden H. Symposium report: the prevention of obesity and NCDs: challenges and opportunities for governments. Obes Rev. 2014;15:630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Gruenigen VE, Gil KM, Frasure HE, et al. The impact of obesity and age on quality of life in gynecologic surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.