Testing can be a learning event. Research from cognitive science suggests that repeated retrieval using various formats can enhance long-term learning, that feedback enhances this benefit, that testing can potentiate further study, and that benefits of testing go beyond rote memory. These observations open opportunities for teaching and research.

Abstract

Testing within the science classroom is commonly used for both formative and summative assessment purposes to let the student and the instructor gauge progress toward learning goals. Research within cognitive science suggests, however, that testing can also be a learning event. We present summaries of studies that suggest that repeated retrieval can enhance long-term learning in a laboratory setting; various testing formats can promote learning; feedback enhances the benefits of testing; testing can potentiate further study; and benefits of testing are not limited to rote memory. Most of these studies were performed in a laboratory environment, so we also present summaries of experiments suggesting that the benefits of testing can extend to the classroom. Finally, we suggest opportunities that these observations raise for the classroom and for further research.

Almost all science classes incorporate testing. Tests are most commonly used as summative assessment tools meant to gauge whether students have achieved the learning objectives of the course. They are sometimes also used as formative assessment tools—often in the form of low-stakes weekly or daily quizzes—to give students and faculty members a sense of students’ progression toward those learning objectives. Occasionally, tests are also used as diagnostic tools, to determine students’ preexisting conceptions or skills relevant to an upcoming subject. Rarely, however, do we think of tests as learning tools. We may acknowledge that testing promotes student learning, but we often attribute this effect to the studying students do to prepare for the test. And yet, one of the most consistent findings in cognitive psychology is that testing leads to increased retention more than studying alone does (Roediger and Butler, 2011; Roediger and Pyc, 2012). This effect can be enhanced when students receive feedback for failed tests and can be observed for both short-term and long-term retention. There is some evidence that testing not only improves student memory of the tested information but also ability to remember related information. Finally, testing appears to potentiate further study, allowing students to gain more from study periods that follow a test. Given the potential power of testing as a tool to promote learning, we should consider how to incorporate tests into our courses not only to gauge students’ learning, but also to promote that learning (Klionsky, 2008).

We provide six observations about the effects of testing from the cognitive psychology literature, summarizing key studies that led to these conclusions (see Table 1). For the purposes of this essay, we have chosen to report studies performed with undergraduates learning educationally relevant materials (e.g., text passages as opposed to word pairs). We also suggest some ways these key observations can be incorporated into classroom practice to benefit students’ learning, and we note related research questions that could extend our understanding of testing effects in the undergraduate biology classroom.

Table 1.

Key studies delineating test-enhanced learning effects

| Study | Research question(s) | Conclusion | Length of delay before final test | Study participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeated retrieval enhances long-term retention in a laboratory setting | ||||

| “Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention” (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006a) | Is a testing effect observed in educationally relevant conditions? Is the benefit of testing greater than the benefit of restudy? Do multiple tests produce a greater effect than a single test? | Testing improved retention significantly more than restudy in delayed tests. Multiple tests provided greater benefit than a single test. | Experiment 1: 2 d; 1 wk Experiment 2: 1 wk | Undergraduates ages 18–24, Washington University |

| “Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests” (Smith and Karpicke, 2014) | What effect does the type of question presented in retrieval practice have on long-term retention? | Retrieval practice with multiple-choice, free-response, and hybrid formats improved students’ performance on a final, delayed test taken 1 wk later when compared with a no-retrieval control. The effect was observed for both questions that required only recall and those that required inference. Hybrid questions provided an advantage when the final test had a short-answer format. | 1 wk | Undergraduates, Purdue University |

| “Retrieval practice produces more learning that elaborative studying with concept mapping” (Karpicke and Blunt, 2011) | What is the effect of retrieval practice on learning relative to elaborative study using a concept map? | Students in the retrieval-practice condition had greater gains in meaningful learning compared with those who used elaborative concept mapping as a learning tool. | 1 wk | Undergraduates |

| Various testing formats can enhance learning | ||||

| “Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests” (Smith and Karpicke, 2014) | See above. | See above. | See above. | See above. |

| “Test format and corrective feedback modify the effect of testing on long-term retention” (Kang et al., 2007) | What effect does the type of question used for retrieval practice have on retention? Does feedback have an effect on retention for different types of questions? | When no feedback was given, the difference in long-term retention between short-answer and multiple-choice questions was insignificant. When feedback was provided, short-answer questions were slightly more beneficial. | 3 d | Undergraduates, Washington University psychology subjects’ pool |

| “The persisting benefits of using multiple-choice tests as learning events” (Little and Bjork, 2012) | What effect does question format have on retention of information previously tested and related information not included in retrieval practice? | Both cued-recall and multiple-choice questions improved recall compared with the no-test control. However, multiple-choice questions improved recall more than cued-recall questions for information not included in the retrieval practice, both after a 5-min and a 48-h delay. | 48 h | Undergraduates, University of California, Los Angeles |

| Feedback enhances benefits of testing | ||||

| “Feedback enhances positive effects and reduces the negative effects of multiple-choice testing” (Butler and Roediger, 2008) | What effect does feedback on multiple-choice tests have on long-term retention of information? | Feedback improved retention on a final cued-recall test. Delayed feedback resulted in better final performance than immediate feedback, though both showed benefits compared with no feedback. The final test occurred 1 wk after the initial test. | 1 wk | Undergraduate psychology students, Washington University |

| “Correcting a metacognitive error: feedback increases retention of low-confidence responses” (Butler et al., 2008) | What role does feedback play in retrieval practice? Can it correct metacognitive errors as well as memory errors? | Both initially correct and incorrect answers were benefited by feedback, but low-confidence answers were most benefited by feedback. | 5 min | Undergraduate psychology students, Washington University |

| Learning is not limited to rote memory | ||||

| “Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative study with concept mapping” (Karpicke and Blunt, 2011) | What is the effect of retrieval practice on learning relative to elaborative study using a concept map? Does retrieval practice improve students’ ability to perform higher-order cognitive activities (i.e., building a concept map) as well as simple recall tasks? | Compared with elaborative study using concept mapping, retrieval practice improved students’ performance both on final tests that required short answers and final tests that required concept map production. See also earlier entry for this study. | 1 wk | Undergraduates |

| “Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests” (Smith and Karpicke, 2014) | See above. | See above. | See above. | See above. |

| “Repeated testing produces superior transfer of learning relative to repeated studying” (Butler, 2010) | Does test-enhanced learning promote transfer of facts and concepts from one domain to another? | Testing improved retention and increased transfer of information from one domain to another through test questions that required factual or conceptual recall and inferential questions that required transfer. | 1 wk | Undergraduate psychology students, Washington University |

| Testing potentiates further study | ||||

| “Pretesting with multiple-choice questions facilitates learning” (Little and Bjork, 2011) | Does pretesting using multiple-choice questions improve performance on a later test? Is an effect observed only for pretested information or also for related, previously untested information? | A multiple-choice pretest improved performance on a final test, both for information that was included on the pretest and related information. | 1 wk | Undergraduates, University of California, Los Angeles |

| “The interim test effect: testing prior material can facilitate the learning of new material” (Wissman et al., 2011) | Does an interim test over previously learned material improve retention of subsequently learned material? | Interim testing improves recall on a final test for information taught before and after the interim test. | No delay | Undergraduates, Kent State University |

| The benefits of testing appear to extend to the classroom | ||||

| “The exam-a-day procedure improves performance in psychology classes” (Leeming, 2002) | What effect does a daily exam have on retention at the end of the semester? | Students who took a daily exam in an undergraduate psychology class scored higher on a retention test at the end of the course and had higher average grades than students who only took unit tests. | One semester | Undergraduates enrolled in Summer term of Introductory Psychology, University of Memphis |

| “Repeated testing improves long-term retention relative to repeated study: a randomized controlled trial” (Larsen et al., 2009) | Does repeated testing improve long-term retention in a real learning environment? | In a study with medical residents, repeated testing with feedback improved retention more than repeated study for a final recall test 6 mo later. | 6 mo | Residents from Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine programs, Washington University |

| “Retrieving essential material at the end of lectures improves performance on statistics exams” (Lyle and Crawford, 2011) | What effect does daily recall practice using the PUREMEM method have on course exam scores? | In an undergraduate psychology course, students using the PUREMEM method had higher exams scores than students taught with traditional lectures, assessed by four noncumulative exams spaced evenly throughout the semester. | ∼3.5 wk | Undergraduates enrolled in either of two consecutive years of Statistics for Psychology, University of Louisville |

| “Using quizzes to enhance summative-assessment performance in a web-based class: an experimental study” (McDaniel et al., 2012) | What effects do online testing resources have on retention of information in an online undergraduate neuroscience course? | Both multiple-choice and short-answer quiz questions improved retention and improved scores on the final exam for questions identical to those on the weekly quizzes and those that were related but not identical. | 15 wk | Undergraduates enrolled in Web-based brain and behavior course |

| “Increasing student success using online quizzing in introductory (majors) biology” (Orr and Foster, 2013) | What effect do required pre-exam quizzes have on final exam scores for students in an introductory (major) biology course? | Students were required to complete 10 pre-exam quizzes throughout the semester. The scores of students who completed all of the quizzes or none of the quizzes were compared. Students of all abilities who completed all of the pre-exam quizzes had higher average exam scores than those who completed none. | One semester | Community college students enrolled in an introductory biology course for majors |

| “Teaching students how to study: a workshop on information processing and self-testing helps students learn” (Stanger-Hall et al., 2011) | What effect does a self-testing exercise done in a workshop have on final exam questions covering the same topic used in the workshop? | Students who participated in the retrieval-practice workshop performed better on the exam questions related to the material covered in the workshop activity. However, there was no difference in overall performance on the exam between the two groups. | 10 wk | Undergraduate students in a introductory biology class |

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT THE EFFECTS OF TESTING?

Repeated Retrieval Enhances Long-Term Retention in a Laboratory Setting

The idea that active retrieval of information from memory improves memory is not a new one: William James proposed this idea in 1890, and Edwina Abbott and Arthur Gates provided support for this idea in the early part of the 20th century (James, 1890; Abbott, 1909; Gates, 1917). During the past decade, however, evidence of the benefits of testing has mounted. We summarize here three studies illustrating this effect in undergraduates learning educationally relevant materials in a laboratory setting.

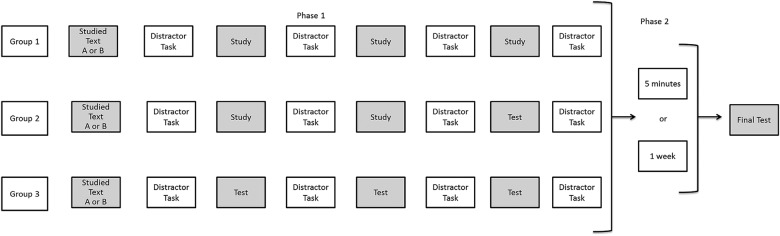

Roediger and Karpicke (2006a) investigated the effects of single versus multiple testing events on long-term retention using educationally relevant conditions. Their goal was to determine whether any connection existed between the number of times students were tested and the size of the testing effect. The investigators worked with undergraduates in a laboratory environment, asking them to read passages ∼250 words long. The authors compared three conditions: students who studied the passages four times for 5 min each (SSSS group); students who studied the passages three times and completed one recall test in which they were given a blank sheet of paper and asked to recall as much of the passage as they could (SSST group); students who studied the passages one time and then performed the recall practice three times (STTT group) (see Figure 1). Student retention was then tested either 5 min or 1 wk later using the same type of recall test used for retrieval practice. Interestingly, results differed significantly depending on when the final test was performed. Students who took their final test very soon after their study period (i.e., 5 min) benefited from repeated studying, with the SSSS group performing best, the SSST group performing second best, and the STTT group performing least well. This result suggests that studying is more effective when the information being learned is only needed for a short time. However, when long-term retention is the goal, testing is more effective. The researchers found that, when the final test was delayed by a week, the results were reversed, with the STTT group performing ∼5% higher than the SSST group and ∼21% higher than the SSSS group. Testing had a greater impact on long-term retention than did repeated study, and the participants who were repeatedly tested had increased retention over those who were only tested once. This supports testing as a learning tool, because, in the laboratory setting, repeated testing facilitated long-term retention more than repeated study.

Figure 1.

Design of Roediger and Karpicke (2006a) experiment examining testing effect.

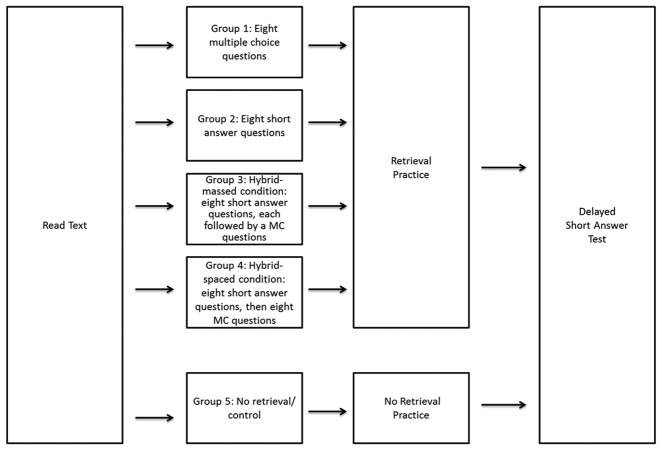

Smith and Karpicke (2014) examined the effects of different types of questions on student learning in a series of experiments with undergraduate students in a laboratory environment. By examining the effects of different question types in a laboratory setting, the authors sought to conclude which is most effective in facilitating learning. In one experiment, five groups of students were compared. Students read four texts, each ∼500 words long. After each reading, four groups of students then participated in different types of retrieval practice, while the fifth group was the no-retrieval control (see Figure 2). One week later, the students returned to the lab for a short-answer test on each of the reading passages. Confirming other studies, students who had participated in some type of retrieval practice performed much better on the final assessment, getting approximately twice as many questions correct as those who did not have any retrieval practice. This was true for both questions that were directly taken from information in the texts and questions that required inference from the text. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the benefits conferred by the different types of retrieval practice; multiple-choice, short-answer, and hybrid questions following the reading were equally effective at enhancing the students’ learning. Other experiments in the series essentially replicated these results, although one experiment did find a slight advantage for hybrid retrieval practice (short answer plus multiple choice) in preparing students for short-answer tests consisting of verbatim questions on short reading passages. These results suggest that the benefits of testing are not tied to a specific type of retrieval practice but rather to retrieval practice in general.

Figure 2.

Design of Smith and Karpicke (2014) experiment examining effect of question format on testing effect.

Karpicke and Blunt sought to evaluate the impact of retrieval practice on students’ learning of undergraduate-level science concepts, comparing the effects of retrieval practice to the elaborative study technique of concept mapping (Karpicke and Blunt, 2011). In one experiment, students studied a science text and were then divided into one of four conditions: a study-once condition, in which they did not interact further with the concepts in the text; a repeated-study condition, in which they studied the text four additional times; an elaborative-study condition, in which they studied the text one additional time, were trained in concept mapping, and produced a concept map of the concepts in the text; a retrieval-practice condition, in which they completed a free-recall test, followed by an additional study period and recall test. All students were asked to complete a self-assessment predicting their recall within 1 wk; students in the repeated-study group predicted better recall than students in any of the other groups. Students then returned a week later for a short-answer test consisting of questions that could be answered verbatim from the text and questions that required inferences from the text. Students in the retrieval-practice condition performed significantly better on both the verbatim questions and the inference questions than students in any other group. The authors then asked whether these results would be observed when different types of texts were used (e.g., those with enumeration structures and those with sequence structures); whether the results would differ for specific students; and whether the advantage of retrieval practice would persist if the final test consisted of a concept-mapping exercise. The authors observed that retrieval practice produced better performance than did elaborative study using concept mapping for both types of texts (enumeration texts and sequence texts) and on both types of final tests (short answer and concept mapping). When they examined the effects on individual learners, they found that 84% (101/120) students performed better on the final tests when they used retrieval practice as a study strategy rather than concept mapping.

Thus, these studies provide evidence that testing can promote learning of educationally relevant materials in laboratory environments. In these examples alone, multiple aspects of the effectiveness for testing as a learning tool were explored. The laboratory environment allowed researchers to determine which method of testing, whether it be type of question or type of information, facilitate the best learning and the most long-term retention. This setting also was used to compare the testing effects seen with other commonly used learning tools, that is, repeated study and concept maps. These summaries provide only an introduction to the rich literature on the testing effect; several recent review articles provide a thorough overview of the work in this area (Roediger and Karpicke, 2006b; Roediger and Butler, 2011; Roediger et al., 2011).

Various Testing Formats Can Enhance Learning

As the study by Smith and Karpicke suggests, multiple testing formats can enhance learning. As noted earlier, they observed that free-recall, multiple-choice, and hybrid testing formats generally provided equivalent benefits, with greater benefits observed for hybrid tests under specific conditions (Smith and Karpicke, 2014). Like Smith and Karpicke, others have studied different question types and their efficacy in increasing short-term and long-term retention.

Kang, McDermott, and Roediger examined the effects of multiple-choice questions and short-answer questions on undergraduate students’ ability to recall information from short articles after a 3-d delay (Kang et al., 2007). In the final test, they used both short-answer and multiple-choice questions. The authors observed that, when students answered either short-answer or multiple-choice questions after reading the article, they recalled more information on the final test, whether the questions on the final test were multiple choice or short answer. When feedback (i.e., the correct answer to the question) was given on the postreading test, short-answer questions provided slightly more benefit than did multiple-choice questions. However, when feedback was not provided, initial multiple-choice questions provided the greater benefit. The authors speculate that the greater retrieval demands of a short-answer question may lead “to more thorough encoding of feedback” (Kang et al., 2007, p. 547).

Little and Bjork (2012) examined the effects of multiple-choice and cued-recall tests on recall of tested information and untested, related information in undergraduates in a laboratory setting. After reading three passages, each student took a cued-recall test for one passage, a multiple-choice test for a second passage, and no test for the third passage. The students then returned 48 h later for a cued-recall test consisting of questions that targeted both previously tested and related but previously untested information. Interestingly, the authors observed that both the multiple-choice and cued-recall tests improved recall over the no-test control for tested information, but only the multiple-choice test improved recall for information that was not included on initial tests.

Together, these and other studies suggest that multiple question formats can provide the benefit associated with testing. It appears that the context may determine which question type provides the greatest benefit, with free-recall questions, multiple-choice, hybrid free-recall/multiple-choice, and cued-recall questions all providing significant benefit over study alone. The most influential studies in the field suggest that free recall provides greater benefit than other question types (see Pyc et al., 2014), but the results described here reveal an incompletely answered question.

Feedback Enhances the Benefits of Testing

Considerable work has been done to examine the role of feedback on the testing effect. Butler and Roediger (2008) designed an experiment in which undergraduates studied 12 historical passages and then took multiple-choice tests in a lab setting. The students either received no feedback, immediate feedback (i.e., following each question), or delayed feedback (i.e., following completion of the 42-item test). One week later, the students returned for a comprehensive cued-recall test. While simply completing multiple-choice questions after reading the passages did improve performance on the final test, corresponding to other reports on the testing effect, feedback provided an additional benefit. Interestingly, delayed feedback resulted in better final performance than did immediate feedback, although both conditions showed benefit over no feedback.

In a follow-up study, Butler, Karpicke, and Roediger demonstrated that feedback can provide a particular benefit by strengthening student recall of correct but low-confidence responses (Butler et al., 2008). Working with undergraduates in a laboratory setting, they asked students multiple-choice items about general knowledge (e.g., What is the longest river in the world?), following each item with a prompt to determine confidence in the answer (i.e., 1 = guess, 4 = high confidence). Students then received feedback for some of the multiple-choice items but no feedback for others. After a 5-min delay, students completed a cued-recall test. While a testing effect was observed even in the absence of feedback, feedback strongly improved final performance, approximately doubling student performance over testing without feedback. This result was true both for questions students had answered correctly and questions they had answered incorrectly on the initial multiple-choice test, but was most pronounced for low-confidence correct answers.

Thus, feedback on both low-confidence correct answers and incorrect answers may further enhance the testing effect, allowing students to solidify their understanding of concepts about which they are unclear. These results are consistent with observations that student learning from in-class concept questions is enhanced by instructor explanations (Smith et al., 2011).

Learning Is Not Limited to Rote Memory

One concern that instructors may have with regard to using testing as a teaching and learning strategy is that it may promote rote memory. While most instructors recognize that memory plays a role in allowing students to perform well within their academic domain, they want their students to be able to do more than simply remember and understand facts, but instead to achieve higher cognitive outcomes (Bloom, 1956). Some studies address this concern and report results suggesting that testing provides benefits beyond improving simple recall. For example, the studies by Karpicke and Blunt (2011) and Smith and Karpicke (2014) described earlier determined the effects of testing on students’ recall of specific facts from reading passages and on their ability to answer questions that required inference. In these studies, the authors defined “inference” as drawing conclusions that were not directly stated within the passages but could be drawn by synthesizing from multiple facts within the passage. In both studies, the investigators observed that testing following reading improved students’ ability to answer both types of questions on a delayed test, thereby providing evidence that benefits of testing are not limited to answers that require only rote memory.

Butler (2010) also examined whether test-enhanced learning can be used to promote transfer, or the ability to use facts and concepts from one domain in a different knowledge domain. In one experiment, undergraduates studied six passages and then restudied two passages, repeatedly took the same test on two passages, and repeatedly took different tests on two passages. The tests were cued recall, and after students responded, feedback was provided. One week later, students returned for a cued-recall test. The test consisted of questions that required factual or conceptual recall and inferential questions that required application of the same fact or concept within the same knowledge domain (Bloom, 1956). As observed by Karpicke and colleagues, testing improved students’ ability to answer both recall and inferential questions.

In a follow-up experiment described in the same report, Butler (2010) examined the effects of testing on students’ ability to transfer knowledge to a different domain, again comparing the effects of testing to restudy. Butler provides the following example to illustrate the “far transfer” effect the experiment targeted:

The following concept was tested on the initial test … : “A bat has a very different wing structure from a bird. What is the wing structure of a bat like relative to that of a bird?” (Answer: “A bird’s wing has fairly rigid bone structure that is efficient at providing lift, whereas a bat has a much more flexible wing structure that allows for greater maneuverability.”) The related inferential question about a different domain was the following: “The U.S. Military is looking at bat wings for inspiration in developing a new type of aircraft. How would this new type of aircraft differ from traditional aircrafts like fighter jets?” (Answer: “Traditional aircrafts are modeled after bird wings, which are rigid and good for providing lift. Bat wings are more flexible, and thus an aircraft modeled on bat wings would have greater maneuverability.”)

Butler observed that repeated testing improved students’ ability to transfer knowledge to different domains when compared with restudy. In this experiment, the students were explicitly told that the information they had studied could be used to answer the questions on the final test, alerting them to the need to use information that might otherwise seem unrelated. Nonetheless, students needed to be able to recall the relevant information and see how it could apply within a new context, and testing enhanced this ability in comparison with studying alone. Butler draws on the work of others to provide potential explanations for this effect, suggesting that retrieving information from memory may lead to the elaboration of existing retrieval routes or the development of additional retrieval routes (Bjork, 1975; McDaniel and Masson, 1985, cited in Butler, 2010).

Testing Potentiates Further Study

Elizabeth Ligon Bjork and colleagues have reported results that raise the intriguing possibility that testing can potentiate further study through experiments that demonstrate that pre-testing improves recall. Little and Bjork examined the effects of multiple-choice pretests on recall of tested information and related, untested information in undergraduates in a laboratory setting. Students read two texts, one of which was preceded by a 10-question multiple-choice test. After a 5-min retention interval, students took a cued-recall test consisting of questions covered on the pretest and questions that were previously untested (Little and Bjork, 2011). This result suggests that the very act of pretesting may enhance students’ later learning, perhaps by cuing students to focus on key ideas and common distracters during subsequent study.

Wissman, Rawson, and Pyc have reported work that suggests retrieval practice over one set of material may facilitate learning of later material that may be related or unrelated (Wissman et al., 2011). Specifically, they investigated the use of “interim tests.” Undergraduate students were asked to read three sections of a text. In the interim test group, they were tested after reading each of the first two sections, specifically by typing everything they could remember about the text. After completing the interim test, they were advanced to the next section of material. The “no interim test” group read all three sections with no tests in between. Both groups were tested on section 3 after reading it. Interestingly, the group that had completed interim tests on sections 1 and 2 recalled about twice as many “idea units” from section 3 as the students who did not take interim tests. This result was observed both when sections 1, 2, and 3 were about different topics and when they were about related topics. Thus, testing may have benefits that extend beyond the target material.

Other studies that used less educationally relevant materials (e.g., word pairs) provide further support to a conclusion that testing can potentiate further study (Hays et al., 2013; see also Soderstrom and Bjork, 2014, and references therein).

The Benefits of Testing Appear to Extend to the Classroom

All of the reports described earlier focused on experiments performed in a laboratory setting. In addition, there are several studies that suggest the benefits of testing may also extend to the classroom.

In 2002, Leeming used an “exam-a-day” approach to teaching an introductory psychology course (Leeming, 2002). He found that students who completed an exam every day rather than exams that covered large blocks of material scored significantly higher on a retention test administered at the end of the semester.

Larsen, Butler, and Roediger asked whether a testing effect was observed for medical residents’ learning about status epilepticus and myasthenia gravis, two neurological disorders, at a didactic conference (Larsen et al., 2009). Specifically, residents participated in an interactive teaching session on the two topics and then were randomly divided into two groups. One group studied a review sheet on myasthenia gravis and took a test on status epilepticus, while the other group took a test on myasthenia gravis and studied a review sheet on status epilepticus. Six months later, the residents completed a test on both topics. The authors observed that the testing condition produced final test scores that averaged 13% higher than the study condition.

Lyle and Crawford (2011) examined the effects of retrieval practice on student learning in an undergraduate statistics class. In one section of the course, students were instructed to spend the final 5–10 min of each class period answering two to four questions that required them to retrieve information about the day’s lecture from memory. The students in this section of the course performed ∼8% higher on exams over the course of the semester than students in sections that did not use the retrieval-practice method, a statistically significant difference.

McDaniel, Wildman, and Anderson examined the effects of unsupervised online quizzing on student performance in a Web-based undergraduate Brain and Behavior class (McDaniel et al., 2012). The goal was to compare the effects of multiple-choice quiz questions, short-answer quiz questions, and targeted study of facts on students’ performance on a unit exam corresponding to about 3 wk worth of class material. Students read textbook chapters weekly and took weekly online quizzes. Some facts were targeted on the online quiz through multiple-choice questions, some were targeted through short-answer questions, some were targeted through representation of the target fact, and some were not represented on the weekly quizzes. The authors observed that both types of quiz questions improved student performance on the unit exam in comparison with facts that were not targeted on the weekly quizzes, both on questions that were identical on the unit exam and the weekly quizzes and on questions that were related but not identical.

Orr and Foster (2013) did a similar study in an introductory biology course for majors, examining the effects of frequent quizzing on student test performance. Using the MasteringBiology platform, Orr and Foster assigned 10 quizzes, each with 10 questions to students over the course of the semester. They then compared exam performance of students who took all or none of the quizzes, finding that students who took all of the quizzes performed significantly better than those who took none of the quizzes. Importantly, this trend was observed both for high-, middle-, and low-performing students, suggesting that frequent quizzing can provide benefit for students across a range of academic abilities (an observation that is consistent with results from Karpicke and Blunt, 2011).

Kathrin Stanger-Hall and colleagues used testing as a learning event in a workshop designed to teach study techniques to students in an introductory biology class (Stanger-Hall et al., 2011). Student volunteers from the class attended several workshop sessions, one of which focused on retrieval practice as a study tool. In this self-testing exercise, students were asked to individually recall and draw a diagram drawn in class the previous week. As a group, students were then asked to generate a table of the structures, structural characteristics, and processes that should have been included in the diagram. At the end of this collective-recall process, students were again asked to draw the diagram individually. To measure the effect of this intervention, the researchers compared the performance of workshop participants and nonparticipants on final exam questions related to the topic covered in the self-testing exercise. Generally, workshop participants’ performance was higher on these questions, although the difference was significant for only three of seven questions, including one of two questions that required higher-level thinking (defined as Bloom’s application level or above). This difference was particularly notable, because overall performance on the exam was not different between the two groups.

WHAT ARE COMMON FEATURES OF “TESTS” THAT PROMOTE TEST-ENHANCED LEARNING?

The term “testing” evokes a certain response from most of us: the person being tested is being evaluated on his or her knowledge or understanding of a particular area and will be judged right or wrong, adequate or inadequate, based on the performance given. This implicit definition does not reflect the settings in which the benefits of “test-enhanced learning” have been established. In the experiments done in cognitive science laboratories, the “testing” was simply a learning activity for the students; in the language of the classroom, it could be considered a “no-stakes” formative assessment with which students could evaluate their memory of a particular subject. In most of the studies from classrooms, the testing was either no-stakes recall practice (Larsen et al. 2009; Lyle and Crawford, 2011; Stanger-Hall et al., 2011) or low-stakes quizzes (McDaniel et al., 2012; Orr and Foster, 2013). Thus, the term “retrieval practice” may be a more accurate description of the activity that promoted students’ learning. Implementing approaches to test-enhanced learning in a class should therefore involve no-stakes or low-stakes scenarios in which students are engaged in a recall activity to promote their learning rather than being repeatedly subjected to high-stakes testing situations. This point may be emphasized by findings from Leight et al. (2012). In this study, students took a collaborative test immediately following a high-stakes individual test in an introductory biology class. The researchers examined the effects on students’ retention of the tested content later in the semester and found that the individual test/collaborative test combination did not have a significant effect, highlighting a potential limitation of the testing effect in a classroom setting.

The distinction between high-stakes and low-/no-stakes testing is particularly important because of the consequences that high-stakes evaluation scenarios can have on identity-threatened groups. Stereotype threat is a phenomenon in which individuals in a stereotyped group underperform on high-stakes evaluations (Steele, 2010). In essence, social cues that activate a stereotype in an identity-threatened group generate anxiety about fulfilling the stereotype, producing a cognitive load that significantly impedes performance on the assessment. This phenomenon has been demonstrated for women in math, African Americans in higher education, white males in sports competitions, and a variety of other groups that are negatively stereotyped in a particular domain. Importantly, the effect is particularly potent in high-achieving individuals within that domain—for example, women who are high achievers in math are more likely to see a decline in their test performance if they are reminded of the stereotype that women are not good at math (Steele, 2010). In science classrooms, it may therefore be particularly important to consider approaches to test-enhanced learning that are no- or low-stakes and are articulated as learning opportunities, thereby minimizing the potential for stereotype threat. The potential for stereotype threat may be further minimized by teaching strategies that indicate that stereotypes are not believed in the class (Cohen et al., 2006; Miyake et al., 2010).

WHY IS IT EFFECTIVE?

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the effects of testing. The retrieval effort hypothesis suggests that the effort involved in retrieval provides testing benefits (Gardiner et al., 1973). This hypothesis predicts that tests that require production of an answer, rather than recognition of an answer, would provide greater benefit, a result that has been observed in some studies (Butler and Roediger, 2007; Pyc and Rawson, 2009) but not others (Little and Bjork, 2012; some experiments in Smith and Karpicke, 2014; some experiments in Kang et al., 2007).

Bjork and Bjork’s new theory of disuse provides an alternative hypothesis to explain the benefits of testing (Bjork and Bjork, 1992). This theory posits that memory has two components: storage strength and retrieval strength. Retrieval events improve storage strength, enhancing overall memory, and the effects are most pronounced at the point of forgetting—that is, retrieval at the point of forgetting has a greater impact on memory than repeated retrieval when retrieval strength is high. This theory aligns with experiments demonstrating that study is as or more effective as testing when the delay before a final test is very short (see, e.g., Roediger and Karpicke, 2006a), because the very short delay between study and the final test means that retrieval strength is very high—an experience many students can verify from their own experience cramming. At a greater delay, however, experiences that build retrieval strength (e.g., testing) confer greater benefit than studying.

More recently, Bjork, Bjork, and colleagues found that multiple-choice tests can confer a benefit by stabilizing access to marginal knowledge (Cantor et al., 2015). This theory supports the use of retrieval practice, because the authors posit that marginal knowledge can be reactivated, and one way to do this is through multiple-choice testing.

WHAT ARE OPPORTUNITIES FOR IMPLEMENTATION IN THE CLASSROOM?

These results point to several possible implementations within the classroom.

Incorporating frequent quizzes into a class’s structure may promote student learning. These quizzes can consist of short-answer or multiple-choice questions and can be administered online or face-to-face. The studies summarized earlier suggest that providing students the opportunity for retrieval practice—and, ideally, providing feedback for the responses—will increase learning of targeted as well as related material.

Providing “summary points” during a class to encourage students to recall and articulate key elements of the class. Lyle and Crawford’s study examined the effects of asking students to write the main points of the day’s class during the last few minutes of a class meeting, and they observed a significant effect on student recall at the end of the semester (Lyle and Crawford, 2011). Setting aside the last few minutes of a class to ask students to recall, articulate, and organize their memory of the content of the day’s class may provide significant benefits to their later memory of these topics. Whether this exercise is called a minute paper or the PUREMEM (pure memory, or practicing unassisted retrieval to enhance memory for essential material) approach, it may benefit student learning.

Perhaps most exciting, Bjork and colleagues have reported results suggesting that pretesting students’ knowledge of a subject may prime them for learning. By pretesting students before a unit or even a day of instruction, an instructor may help alert students both to the types of questions that they need to be able to answer and the key concepts and facts they need to be alert to during study and instruction.

Finally, instructors may be able to aid their students’ metacognitive abilities by sharing a synopsis of these observations. Telling students that frequent quizzing helps learning—and that effective quizzing can take a variety of forms—can give them a particularly helpful tool to add to their learning tool kit (Stanger-Hall et al., 2011). Adding the potential benefits of pretesting may further empower students to take control of their own learning, such as by using example exams as primers for their learning rather than simply as pre-exam checks on their knowledge.

As noted above, when considering ways to use testing to promote learning in a class, it may be important to use no- or low-stakes testing scenarios. This approach may allow the testing to serve as a learning event for the students with minimal potential for provoking anxiety or other performance-inhibiting responses. Pulfrey, Buchs, and Butera provide evidence that instructor feedback can be particularly valuable for student study behavior when the feedback is not accompanied by a grade, suggesting that multiple aspects of a testing-for-learning scenario may have maximum benefit under these conditions (Pulfrey et al., 2011).

It is important to note that incorporating testing—or recall practice—as a learning tool in a class should be done in conjunction with other evidence-based teaching practices, such as sharing learning objectives with students, carefully aligning learning objectives with assessments and learning activities, and offering opportunities to practice important skills. When considered through that lens, using retrieval practice as a learning tool may be a particularly valuable opportunity to both strengthen memory and to promote students’ metacognition (Tanner, 2012).

WHAT ARE THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR RESEARCH?

Although each of the opportunities for the classroom is consistent with results observed in a psychology lab, and these practices have been supported in some classroom-based experiments, we believe that the testing effect has not been investigated extensively in college biology classrooms. Thus, research questions are abundant: Are frequent quizzes in an undergraduate biology class effective at promoting recall on a later test? Do they help prepare students to answer questions that require higher-level cognitive functions? Is there a quizzing regimen that is particularly effective? What delay between study and quizzing is most effective? Are particular types of quiz questions more effective than others? Does regular quizzing impact student study behavior? Are testing effects observed that are independent of/additive with such behavioral changes? Do pretests have a measurable effect on student learning? If so, what are the parameters of this effect? Is the testing effect observed for all students, or does it have particular benefits or harms for certain groups of students? The questions that can be asked about the role of testing in students’ biology learning are important and largely unanswered and a rich source for new investigations.

One particularly rich opportunity for research relates to the type of learning outcomes that testing can promote. Relatively little work has been done on the degree to which the testing effect can impact lower- versus higher-order cognitive outcomes. While some studies have addressed the impact of retrieval practice on students’ ability to answer questions requiring inference, and one study has examined the effects of retrieval practice on students’ ability to construct concept maps, these experiments involved relatively limited assessments of learning outcomes (Butler, 2010; Karpicke and Blunt, 2011; Smith and Karpicke, 2014). Experiments performed in a class examining a range of cognitive outcomes, such as the research described by Stanger-Hall et al. (2011), would provide a more robust evaluation of the testing effect.

Pretesting may also provide a particularly interesting opportunity within the biology classroom. Most studies that have demonstrated test-enhanced learning have relied on retrieval practice, thereby strengthening students’ ability to recall key information. In these studies, the retrieval practice may have also given students the opportunity to process the retrieved information and link it to other phenomena, but it did not explicitly alert students to the types of cognitive outcomes they should expect to achieve. Pretesting, on the other hand, has the potential to do exactly that (Little and Bjork, 2011), priming students to focus on key information and cognitive activities encountered during study. In this way, pretesting may serve to produce “a time for telling,” as Schwartz and Bransford (1998) observed when they had students’ compare conflicting data sets before reading and lecture. Investigating this possibility may be a particularly fruitful avenue for biology education researchers.

SUMMARY

The testing effect has a rich history in the cognitive psychology literature, with results from laboratory experiments indicating that retrieval practice enhances long-term retention; multiple question types can be effective; feedback enhances the benefits of testing; the testing effect is not limited to enhancing rote memory; and testing potentiates further study. A limited number of studies have suggested that test-enhanced learning may be achieved in the college classroom through incorporation of low- or no-stakes retrieval practice. A variety of questions about the parameters and limitations of test-enhanced learning in the undergraduate biology classroom remain unanswered, providing a rich avenue for future inquiry.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.CBE-14-11-0208) on March 03, 2015.

REFERENCES

- Abbott EE. On the analysis of the factors of recall in the learning process. Psychol Monogr. 1909;11:159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA. In: Information Processing and Cognition, ed. New York: Wiley; 1975. Retrieval as a memory modifier: an interpretation of negative recency and related phenomena; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork RA, Bjork EL. In: From Learning Processes to Cognitive Processes: Essays in Honor of William K. Estes, vol. 2, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation; p. 35067. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC. Repeated testing produces superior transfer of learning relative to repeated studying. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2010;36:1118–1133. doi: 10.1037/a0019902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Karpicke JD, Roediger HL., III Correcting a metacognitive error: feedback increases retention of low-confidence correct responses. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2008;14:918–928. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Roediger HL., III Testing improves long-term retention in a simulated classroom setting. Eur J Cogn Psychol. 2007;19:514–527. [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Roediger HL., III Feedback enhances the positive effects and reduces the negative effects of multiple-choice testing. Mem Cogn. 2008;36:604–616. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.3.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor AD, Eslick AN, Marsh EJ, Bjork RA, Bjork EL. Multiple-choice tests stabilize access to marginal knowledge. Mem Cogn. 2015;43:193–205. doi: 10.3758/s13421-014-0462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GL, Garcia J, Apfel N, Master A. Reducing the racial achievement gap: a social-psychological intervention. Science. 2006;313:1307–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.1128317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner JM, Craik FIM, Bleasdale FA. Retrieval difficulty and subsequent recall. Mem Cogn. 1973;1:213–216. doi: 10.3758/BF03198098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates AI. Recitation as a factor in memorizing. Arch Psychol. 1917;6(40) [Google Scholar]

- Hays MJ, Kornell N, Bjork RA. When and why a failed test potentiates the effectiveness of subsequent study. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2013;39:290–296. doi: 10.1037/a0028468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W. The Principles of Psychology. New York: Holt; 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Kang SHK, McDermott KB, Roediger HL., III Test format and corrective feedback modify the effect of testing on long-term retention. Eur J Cogn Psychol. 2007;19:528–558. [Google Scholar]

- Karpicke JD, Blunt JR. Retrieval practice produces more learning than elaborative studying with concept mapping. Science. 2011;331:772–775. doi: 10.1126/science.1199327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ. The quiz factor. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2008;7:265–266. doi: 10.1187/cbe.08-02-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen DP, Butler AC, Roediger HL., III Repeated testing improves long-term retention relative to repeated study: a randomized controlled trial. Med Educ. 2009;43:1174–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeming FC. The exam-a-day procedure improves performance in psychology classes. Teach Psychol. 2002;29:210–212. [Google Scholar]

- Leight H, Saunders, Calkins R, Withers M. Collaborative testing improves performance but not content retention in a large-enrollment introductory biology class. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11:392–401. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-04-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little JL, Bjork EL. Pretesting with multiple-choice questions facilitates learning. Presentation at Cognitive Science Society, Boston, MA, July 2011. 2011 www.researchgate.net/publication/265883438_Pretesting_with_Multiple-choice_Questions_Facilitates_Learning (accessed 15 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Little JL, Bjork EL. The persisting benefits of using multiple-choice tests as learning events. Presentation at Cognitive Science Society, Sapporo, Japan, August 2012. 2012 http://mindmodeling.org/cogsci2012/papers/0128/paper0128.pdf (accessed 11 November 2014) [Google Scholar]

- Lyle KB, Crawford NA. Retrieving essential material at the end of lectures improves performance on statistics exams. Teach Psychol. 2011;38:94–97. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Masson MEJ. Altering memory representations through retrieval. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 1985;11:371–385. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel MA, Wildman KM, Anderson JL. Using quizzes to enhance summative-assessment performance in a web-based class: an experimental study. J Appl Res Mem Cogn. 2012;1:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Kost-Smith LE, Finkelstein ND, Pollock SJ, Cohen GL, Ito TA. Reducing the gender achievement gap in college science: a classroom study of values affirmation. Science. 2010;330:1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.1195996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr R, Foster S. Increasing student success using online quizzing in introductory (majors) biology. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2013;12:509–514. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-10-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulfrey C, Buchs C, Butera F. Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: the mediating role of autonomous motivation. J Educ Psychol. 2011;103:683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Pyc MA, Agarwal PK, Roediger HL., III . Test-enhanced learning. In: Benassi V, Overson C, Hakala C, editors. In: Applying the Science of Learning in Education: Infusing Psychological Science into the Curriculum, ed. Society for the Teaching of Psychology; 2014. http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php (accessed 14 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pyc MA, Rawson KA. Testing the retrieval effort hypothesis: does greater difficulty correctly recalling information lead to higher levels of memory? J Mem Lang. 2009;60:437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Butler AC. The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Karpicke JD. Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychol Sci. 2006a;17:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Karpicke JD. The power of testing memory: basic research and implications for educational practice. Persp Psychol Sci. 2006b;1:181–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Putnam AL, Smith MA. Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. Psychol Learn Motiv. 2011;55:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roediger HL, III, Pyc MA. Inexpensive techniques to improve education: applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice. J App Res Mem Cogn. 2012;1:242–248. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DL, Bransford JD. A time for telling. Cogn Instr. 1998;16:475–522. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MA, Karpicke JD. Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests. Memory. 2014;22:784–802. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2013.831454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MK, Wood WB, Krauter K, Knight JK. Combining peer discussion with instructor explanation increases student learning from in-class concept questions. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2011;10:55–63. doi: 10.1187/cbe.10-08-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderstrom NC, Bjork RA. Testing facilitates the regulation of subsequent study time. J Mem Lang. 2014;73:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Stanger-Hall KF, Shockley FW, Wilson RE. Teaching students how to study: a workshop on information processing and self-testing helps students learn. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2011;10:187–198. doi: 10.1187/cbe.10-11-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York: Norton; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner KD. Promoting student metacognition. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2012;11:113–120. doi: 10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissman KT, Rawson KA, Pyc MA. The interim test effect: testing prior material can facilitate the learning of new material. Psychon Bull Rev. 2011;18:1140–1147. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]