During the 2012–2013 academic year, 7.7 million secondary school students took part in organized interscholastic sports, compared with just 4 million participants during the 1971–1972 year.1 Many student-athletes define themselves by their identities as athletes.2 Threats to that identity may come in the form of struggling performance; a chronic, career-ending, or time-loss injury; conflicts with coaches and teammates; or simply losing the passion for playing their sport.3–5 These challenges and associated factors may put the student-athlete in a position to experience a psychological concern or to exacerbate an existing mental health concern.2

The types, severities, and percentages of mental illnesses are growing in young adults aged 18 to 25 years, an age group a little older than secondary school student-athletes.6 Given that mental illnesses being reported in the 18- to 25-year-old age group may well start before or during adolescence and given the overall numbers of student-athletes at the secondary school level, clinicians are certain to encounter student-athletes with psychological concerns. The goal of this consensus statement is to provide recommendations for developing a plan to address the psychological concerns of student-athletes at the secondary school level. The recommendations will discuss education on mental disorders in young adults, stressors unique to being a student-athlete at the secondary school level, recognition of behaviors to monitor, special circumstances faced by student-athletes that may affect their psychological health, collaborating with secondary school professionals to assist student-athletes with psychological concerns, and legal considerations. Also addressed are educational efforts for student-athletes, coaches, and parents, as well as practical steps to consider when proposing a psychological-concerns plan to administration. The interassociation work group that developed these recommendations included representatives from 8 national organizations and an attorney experienced in sports medicine and health-related litigation; all members had a special interest in and experience with psychological concerns in student-athletes. This multidisciplinary group of professionals included experts in athletic training, general medicine, psychology, psychiatry, pediatrics, secondary school counseling, sport psychology, critical-incident stress management, and law.

Recommendations of the consensus statement are directed at the athletic health care team, athletic department administration and staff, and secondary school administration. This includes athletic trainers (ATs); team physicians; coaches; athletic department administrators; administrators such as principals and superintendents; secondary school nurses; and secondary school counselors. It is imperative to remember that the student-athlete is first and foremost a student of the school district and in most cases a minor child; therefore, collaboration with secondary school departments is a must.

Two points about this consensus statement are critical. First, the terms psychological concern and mental disorder are used instead of mental illness because only credentialed mental health care professionals have the legal authority to diagnose a mental illness. Suspecting a mental illness in a student-athlete that affects the student-athlete's psychological health is a concern that noncredentialed mental health care professionals have. Thus, we selected psychological concerns for the title, although that term and mental disorder are interchangeable within the statement. Second, only credentialed, licensed mental health care professionals are to legally evaluate, diagnose, treat, and classify a student-athlete with a mental illness. The credentialed mental health care professional should perform that medical-legal duty and not a noncredentialed individual, no matter how caring that person may be. This consensus statement was produced to inform ATs about developing a plan to recognize potential psychological concerns in secondary school student-athletes and to establish an effective mechanism for referring the student-athlete into the mental health care system for assessment and treatment by a credentialed mental health care professional. This consensus statement does not make recommendations regarding mental illness evaluation or care. Rather, our intent was to assist the AT, in collaboration with the athletic department and secondary school administration, in facilitating the evaluation and care of the student-athlete suspected of a psychological concern by credentialed mental health care professionals. Throughout this statement, the terms psychological and mental are used; various authors in both the text and in literature citations chose to use one or the other. Although the terms are synonymous, the focus of the statement is recognition and referral, not treatment; treatment is left to the credentialed mental health care professional. Additionally, in this statement, the term secondary school is interchangeable with high school as found in the literature.

This statement mirrors the 2013 document “Interassociation Recommendations for Developing a Plan to Recognize and Refer Student-Athletes With Psychological Concerns at the Collegiate Level: An Executive Summary of a Consensus Statement.”2 That statement was designed for use by the AT practicing at the intercollegiate level. The current statement is designed for use by ATs practicing at the secondary school level, or in the absence of an AT at a particular secondary school, administrators may use this statement to develop a plan to address their student-athletes' psychological concerns. Ideally, a certified AT will help to develop and implement the recommendations of this consensus statement. The information contained in the collegiate and high school statements is similar but is targeted for each audience, and each statement is to be regarded as a stand-alone document for the indicated setting.

Purpose of This Consensus Statement

The purpose of this consensus statement is for the reader to take the information provided and develop an appropriate plan for his or her institution to address the psychological concerns of student-athletes as part of a comprehensive sports medicine health care program. Specific goals of the statement are to

-

1.

Provide essential information on mental illness in adolescents.

-

2.

Describe stressors unique to student-athletes and give examples of triggers that may create a new mental disorder or exacerbate an existing mental disorder.

-

3.

Offer appropriate information for recognizing potential psychological concerns in student-athletes through behaviors to monitor.

-

4.

Review special considerations that may challenge a student-athlete's mental health.

-

5.

Discuss considerations in developing a referral system so that student-athletes can obtain psychological assistance.

-

6.

Develop an ongoing relationship with secondary school entities to assist in the referral, care, and disposition of psychological issues in student-athletes.

-

7.

Describe considerations during mental health emergencies and catastrophic incidents.

-

8.

Address legal liability for secondary schools when developing a plan to refer student-athletes with psychological concerns.

-

9.

Explain considerations in educating student-athletes, coaches, and parents on psychological health.

-

10.

Suggest considerations for collaborating with athletic departments and school administrations in developing a plan to effectively recognize, refer, and care for secondary school student-athletes with psychological concerns.

Organization of Consensus Statement

This consensus statement is organized as follows:

-

1.

Background and review of mental illness in adolescents, recommendations for recognizing potential psychological concerns in student-athletes through discussion of stressors unique to student-athletes, and triggering mechanisms or events that may create a mental illness or exacerbate an existing mental illness

-

2.

Behaviors to monitor

-

3.

Recommendations for special circumstances with potential effects on a student-athlete's mental health: psychological response to injury; concussions; substance and alcohol abuse; attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis, treatment, and documentation; eating disorders; bullying and hazing considerations

-

4.

Recommendations for collaboration among the AT, school nurse, and school counselors to recognize psychological concerns; preparticipation physical examination screening questions and tools to indicate a history of prior mental disorder; approaching a student-athlete with a potential psychological concern; and referring the student-athlete to a secondary school counseling service or a community mental health care professional, including for an emergent mental health incident

-

5.

Recommendations for confidentiality considerations

-

6.

Recommendations for attending to mental health emergency incidents and mental health catastrophic incidents

-

7.

Recommendations for legal considerations in developing a plan to deal with the psychological concerns of student-athletes, particularly minor children

-

8.

Recommendations for educating student-athletes, coaches, and parents on psychological health

-

9.

Recommendations on collaborating with athletic department and secondary school administration in developing a plan and document to share with ATs, school nurses, school counselors, team physicians, athletic administration, and coaches to effectively address student-athlete psychological concerns

-

10.

Conclusions

The recommendations in this consensus statement use the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) criterion scale proposed by the American Academy of Family Physicians,7 which are based on the highest quality of evidence available. Each letter designation characterizes the quality, quantity, and consistency of evidence in the available literature to support a recommendation.

A. The recommendation is based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence.

B. The recommendation is based on inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence.

C. The recommendation is based on consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, or a case series for studies of diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or screening.

Although this consensus statement uses SORT level C evidence for best practices, the educational component of mental illness in young adults is based on SORT level A evidence.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Education About Mental Disorders in Young Adults

-

1.

The Plan for Recognition and Referral of Student-Athletes With Psychological Concerns (also known as the Plan) includes data on the prevalence of mental disorders in American adolescents, including the definition of a mental disorder according to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition.8

-

2.

The Plan provides data on mental disorders in adolescents and young adults.

-

3.

The Plan reviews data on the comorbidity of mental disorders and the risk factors in mental disorders affecting adolescents and young adults.

Category: A

Recognition of Psychological Concerns in Student-Athletes

-

1.

The Plan lists stressors unique to student-athletes.

-

2.

The Plan lists behaviors to monitor.

-

3.

The Plan provides a list of depression symptoms.

-

4.

The Plan offers a list of anxiety symptoms.

-

5.

The Plan contains a nonexclusive list of special considerations that may affect the student-athlete: psychological response to injury or loss of playing time or career, concussion, substance or alcohol abuse, ADHD, eating disorder, bullying, and hazing.

Category: A

Referring Student-Athletes for Psychological Concerns

-

1.

The Plan considers the familiarity of the AT, school nurse, school counselor, and team physician in identifying potential psychological concerns at the secondary school level.

-

2.

The Plan offers questions regarding a student-athlete's history of a mental health concern or present psychological status at the preparticipation physical examination, with follow-up questionnaires if the student-athlete's answers indicate the need for further evaluation.

-

3.

The Plan provides questions to consider asking when approaching a student-athlete with a potential psychological concern.

-

4.

The Plan addresses referring the student-athlete for psychological concerns. The Plan recommendations include a secondary school district emergent-referral plan.

-

5.

The Plan addresses suicide by providing facts and figures, suicide risk and protective factors, suicide symptoms and danger signs, steps to take in the presence of fears that a student-athlete may take his or her life, and information on surviving the loss of a loved one to suicide.

-

6.

The Plan discusses confidentiality issues.

Categories: B, C

Student-Athlete Mental Health Emergencies and Catastrophic Incidents

-

1.

The Plan recommends the development of an Emergency Action Plan that follows the recommendations in the “National Athletic Trainers' Association's Position Statement: Emergency Planning in Athletics”9 that will be implemented in the event of a student-athlete emergency stemming from a mental health incident (attempted harm to oneself or others).

-

2.

The Plan recommends the development of a Catastrophic Incident Guideline, which will be implemented in the event of a student-athlete mental health catastrophic incident (suicide, homicide, permanent disability).

-

3.

The Plan recommends developing, in collaboration with counseling services and other crisis management organizations, a crisis counseling plan to be implemented after a catastrophic incident.

Categories: A, B

Legal Considerations

The Plan reviews legal implications to be shared with the secondary school district general counsel when developing the Plan and recommends general counsel approval of the Plan before implementation.

Categories: B, C

Building Plan for Recognition and Referral of the Student-Athlete With Psychological Concerns

-

1.

Establish the need for the Plan with secondary school administration and athletic department administration by using data and other best-practices information found in the consensus statement.

-

2.

Write an initial draft of the Plan document by using information found in the consensus statement.

-

3.

Share the Plan draft with secondary school administration and staff and athletics administration for feedback from and approval by all entities.

-

4.

Once the Plan is approved, distribute it to all ATs, school nurses, school counselors, team physicians, coaches, and administrators involved in the Plan for referral.

-

5.

Review the Plan annually and update as necessary, including all involved entities.

-

6.

Provide a psychological-health educational component to student-athletes and their parents or guardians.

Category: C

BACKGROUND

Similar to physical injuries, psychological concerns can range from mild to severe, with varying effects on the life of the adolescent. In addition, some of these conditions can be lifelong, whereas others may be short-lived. Normal adolescence is a period of great change and maturation, during which emotional and behavioral difficulties are commonplace; however, the incidence of diagnosed mental health conditions remains consistent across studies, and psychological concerns must be appropriately recognized and treated.

In 2001, the US Surgeon General10 defined mental health as “the successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and to cope with adversity.” Approximately 1 in every 4 to 5 youths in this country experiences impairment during his or her lifetime as a result of a mental health disorder.11 The prevalence of many emotional and behavioral disorders in children and adolescents is higher than that of some well-known physical ailments, such as asthma and diabetes.11

The American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5),8 states that “a mental disorder is a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotional regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental process underlying mental functioning.” The definition8 further states that mental disorders are “usually associated with significant distress or disability in social, occupational, or other important activities.” It is important to note that classifying a mental disorder only describes the mental disorder an individual has; it does not describe the individual.8 Thus, labeling a student-athlete as a “maniac” or a “druggie” further stigmatizes individuals with mental disorders. The diagnosis of a mental disorder should also have clinical utility, meaning it should assist clinicians in determining the treatment plan and prognosis for the patient. Having the diagnosis of a mental disorder is not equivalent to needing treatment.8

Most DSM-5 disorders have a numeric International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code, and the DSM-5 disorders are grouped into 22 major diagnostic classes, categorizing hundreds of mental disorders.8 The DSM-5 diagnosis is applied to an individual's current presentation, not to a previous diagnosis.8 It is imperative that the DSM-5 not be applied by untrained individuals. Only those with appropriate clinical training and diagnostic skills may diagnose an individual with a mental disorder. The criteria in the DSM-5 serve as a guideline for the mental health care professional to form a clinical judgment and are not merely a recipe to follow.8

In a recent study, nearly 1 in 3 adolescents (31.9%) met the criteria for anxiety disorder, 19.1% were affected by behavioral disorders, 14.3% experienced mood disorders, and 11.4% had substance-use disorders.11 The early onset of major classes of mental disorders has been documented.6 Of the affected adolescents,11 half experienced symptoms of their anxiety disorder by age 6, of their behavioral disorder by age 11, of their mood disorder by age 13, and of their substance-use disorder by age 15. Comorbidity rates of affected individuals have been reported at 40%, and 22.2% described having a mental disorder with severe impairment or distress that interfered with daily life.11

The average age of onset for major depression and dysthymia is between 11 and 14 years of age.12 The rate of outpatient treatment for depression13 increased markedly in the United States between 1987 and 1997, with 75.3% of those individuals being treated with antidepressant medication in 2007.

The US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration6 reported in 2012 that 45.9 million American adults aged 18 or older, 20% of the survey population, experienced a mental illness in 2010. Of those aged 12 to 17 years, 8% (1.9 million) had experienced a major depressive episode in 2010, which was defined as having a depressed mood or loss of interest in daily activities that lasted at least 2 weeks.6

Most seriously impairing and persistent mental disorders found in adults are associated with onset during childhood or adolescence and have high comorbidity.14 Of adolescents aged 13 to 17 years who had experienced childhood adversity (ie, parental loss, parental maltreatment, parental maladjustment, or economic hardship), 58.3% reported at least 1 childhood adversity and 59.7% reported multiple childhood adversities; childhood adversities were strongly associated with the onset of psychiatric disorders. The prevalence ranged from 15.7% with fear disorders to 40.7% with behavioral disorders. A total of 28.2% of all onsets of psychiatric disorders were associated with 1 or more childhood adversities.15 Disorder onset was somewhat predictable and provides clues to the best times for intervention. The median age of disorder onset was 6 years for anxiety, 11 years for behavior, 13 years for mood, and 15 years for substance use.16

Epidemiologic surveys estimate that as many as 30% of the adult population in the United States meet the criteria for a year-long DSM mental disorder.17,18 Fewer than half of individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder receive treatment.19,20 Mental disorders are widespread, with serious cases concentrated in a relatively small proportion of patients with high comorbidity.21Anxiety disorders are reported often in mental-disorder surveys21 and appear to exact significant and independent tolls on health-related quality of life.22

Mental health care professionals are discovering more information on various mental health disorders. For example, intermittent explosive disorder is much more common than previously recognized.23 The typical onset is at age 14 years, with significant comorbidity of mental disorders that have later ages of onset. Only 28.8% of patients ever received treatment for their anger.23

Anxiety disorders, such as panic disorders and social phobia, were the most common conditions, affecting 31.9% of teens. Next were behavioral disorders, including ADHD, which affect 19.1% of teens. Mood disorders, including major depressive disorder, were third at 14.3% and substance-use disorders were fourth at 11.4%.2 Comorbidity is also a significant concern within this age group, given that nearly 40% of patients with 1 class of disorder also met the criteria for a second class of disorder at some point in their lives.

In a landmark study funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the prevalence of a broad range of mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents was examined. Participants in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement consisted of youths aged 13 to 18 years. One in 10 children had a serious emotional disturbance that interfered with daily activities. In addition, few affected youths received adequate mental health care. Mood disorders affected 14.3% of teens, including twice as many girls as boys. The prevalence of these disorders increased with age: a nearly 2-fold increase between age 13 to 14 years and age 17 to 18 years. One in 3 adolescents (31.9%) met the criteria for an anxiety disorder, ranging from 2.2% for generalized anxiety disorder to 19.3% for a specific phobia. These disorders are more common in girls.11

Concerns about adolescent mental health are shared by many countries. In a review24 of community survey studies from around the world, approximately one-fourth of youths experienced a mental disorder during the past year and about one-third did so across their lifetimes.

The incidence of depression increases with age. It is 1% to 2% at age 13, climbs to 3% to 7% at age 15, and continues to increase throughout early adulthood. Results are mixed when it comes to the effects of social class, race, and ethnicity.11 Although rare in children, the prevalence of bipolar disorder (mania and hypomania) ranges from 0% to 0.9% in those aged 14 to 18 and from 0% to 2.1% over a lifetime. As far as comorbidity, both major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder are associated with multiple other conditions, including ADHD, anxiety disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder.25,26 Half of all adult mental disorders have their onset during adolescence, and suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents.27

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey28 revealed the following regarding adolescent medication use for psychological concerns:

Approximately 6.0% of US adolescents aged 12 to 19 reported psychotropic drug use in the past month.

Antidepressants (3.2%) and ADHD drugs (3.2%) were used most often, followed by antipsychotics (1.0%); anxiolytics, sedatives, and hypnotics (0.5%); and antimanics (0.2%).

Boys (4.2%) were more likely than girls (2.2%) to use ADHD drugs. Girls (4.5%) were more likely than boys (2.0%) to use antidepressants.

Psychotropic drug use was higher among non-Hispanic white adolescents (8.2%) than non-Hispanic black (3.1%) and Mexican American (2.9%) adolescents.

About one-half of US adolescents using psychotropic drugs in the past month had seen a mental health professional in the past year (53.3%).

By 2020, it is estimated that psychiatric and neurologic conditions will account for 15% of the total burden (in terms of both prevalence and financial costs) of all diseases. Identified gaps in resources for childhood mental health that can be targeted for improvement can be categorized as economic, staffing, training, and policy.24 Approximately 25% of affected youth will have a second mental health disorder. This incidence actually increases 1.6 times for each additional year from age 2 (18.2%) to age 5 (49.7%). In addition, children with a physical illness are more likely to develop depression and those with an emotional disorder have an increased risk of developing physical disorders.29,30

Considering the number of student-athletes within secondary school athletic departments and the statistical data on mental disorders in the United States, particularly those affecting adolescents, there is a high probability that most secondary school athletic teams include student-athletes who experience 1 or more psychological concerns. The AT, in collaboration with the athletic department and secondary school administration, should develop a plan to recognize student-athletes with psychological concerns and facilitate an effective referral system to mental health care professionals for evaluation and treatment.

RECOGNITION OF PSYCHOLOGICAL CONCERNS IN STUDENT-ATHLETES

Stressors and Triggering Events Unique to Secondary School Student-Athletes

To maintain a competitive advantage, universities may recruit increasingly younger players, which affects secondary school coaches, student-athletes, and their families. Many student-athletes report higher levels of negative emotional states than non–student-athlete adolescents and have been identified as having higher incidence rates for sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, mood disturbances, short tempers, decreased interest in training and competition, decreased self-confidence, and inability to concentrate.

Some of these changes in mood can also be related to overtraining.31,32 Due to pressures to win, competitions for athletic scholarships, and the adoption of professional training methods to ensure these outcomes, overtraining has become a way of life for many of our young athletes. They may compete year-round, often with multiple teams, and both train and compete multiple times each week. However, an emphasis on work without time for rest and recovery can lead to physical and psychological staleness and burnout.33–35

Student-athletes often exhibit sport identity foreclosure,36 and the greater this rigid identification, the more negative the psychological reaction can be when real and perceived barriers arise in their sporting lives. Stressors of athletic participation may include being cut from a team, dealing with injury, performance challenges, mistakes in play, dealing with success, pressure to overspecialize or overtrain, and early termination from sport.37–39

Demands and stressors on the student-athlete can be physical (eg, physical conditioning, injuries, environmental conditions), mental (eg, game strategy, meeting coaches' expectations, attention from media and fellow students, time spent in sport, community-service requirements, and less personal and family time), and academic (eg, classes, study time, projects, papers, examinations, attaining and maintaining the required grade point average to remain on the team, and earning and maintaining a collegiate or academic scholarship). These stressors place numerous expectations on a student-athlete.40

Pressure on a student-athlete is common when there is no off-season and training continues throughout the year. The student-athlete is exposed to a predictable pattern of lack of sleep and underrecovery, putting him or her at risk for anxiety and depression.41–53 Recovery is closely related to well-being and performance, yet many student-athletes are mired in persistent cycles of chronic fatigue.46 For student-athletes, the complex combination of long-term training and uncontrollable life variables often leads to overtraining, putting them at risk for physical, mental, and emotional health problems.

All too often, athletes are portrayed as superhuman, larger than life, and unaffected by stress or concerns of a clinical nature.54–58 Although many individuals are equipped to meet these physical and mental expectations, a segment of the student-athlete population will have difficulty. The stressors of being a student-athlete can trigger a new psychological concern, exacerbate an existing concern, or cause a past concern to resurface. Triggering events and stressors to be aware of are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Triggering Events3

| Events may serve to trigger a new mental or emotional health concern or exacerbate an existing condition in a student-athlete. Some examples of these triggering events are |

| • Poor performance or perceived poor performance by the student-athlete |

| • Conflicts with coaches or teammates |

| • A debilitating injury or illness, resulting in a loss of playing time or surgery |

| • Concussions |

| • Class concerns: schedule, grades, amount of work |

| • Lack of playing time |

| • Family and relationship issues |

| • Changes in importance of sport, expectations by self/parents, role of sport in life |

| • Violence: being assaulted, a victim of domestic violence, automobile accident, or merely witnessing a personal injury or assault on a family member, friend, or teammate |

| • Bullying or hazing |

| • Adapting to school schedule |

| • Lack of sleep |

| • History of mental disorder |

| • Burnout from sport or school |

| • Anticipated end of playing career |

| • Sudden end of career due to injury or medical condition |

| • Death of a loved one or close friend |

| • Alcohol or drug abuse |

| • Significant dieting or weight loss |

| • History of physical or sexual abuse |

| • Gambling problems |

| Adapted with permission from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. |

Behaviors to Monitor

The AT, team physicians, and others in the athletic department (eg, athletic administrators, coaches, academic support staff, school counselors) are in positions to observe and interact with student-athletes on a daily basis. In most cases, athletic department and secondary school personnel have the trust of the student-athlete, and the student-athlete may turn to them for advice or assistance with a personal concern or during a crisis. Other student-athletes may seek out teammates or nonathlete students, teachers, friends, or family members. However, some student-athletes, will not be aware of how a stressor is affecting them, or even if they are aware, will not inform anyone. These student-athletes may act out in a nonverbal way to alert others that something is bothering them.3–5 Oftentimes, when a student-athlete, AT, team physician, coach, teammate, or parent considers a student-athlete's health, the primary thought is of a physical injury and its effect on participation status; the student-athlete's mental health may be secondary.59 However, both physical and mental health are equally important for the student-athlete's well-being.

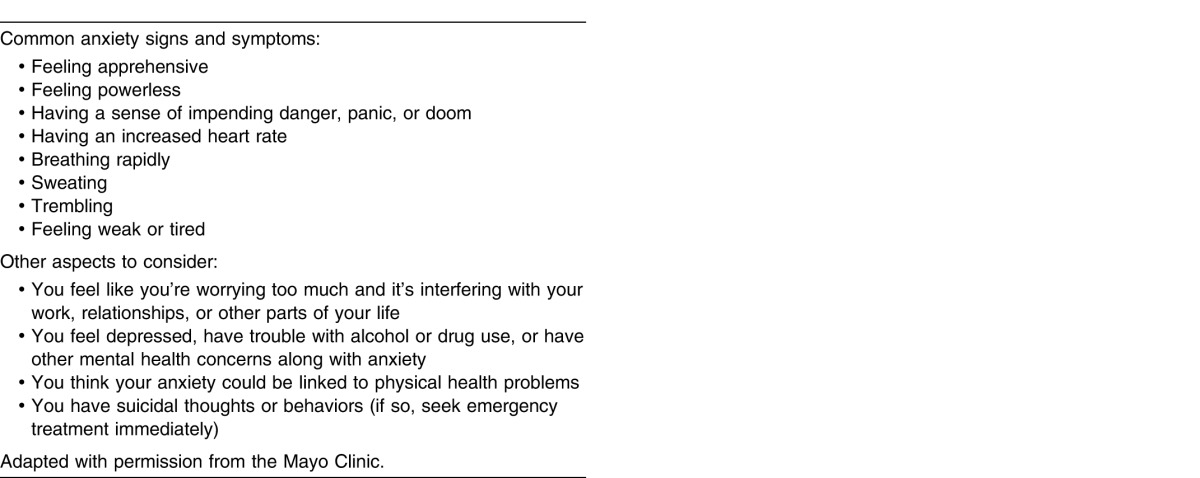

Behaviors that may be symptoms of a psychological concern in a student-athlete are provided in Table 2, although the list is not all-inclusive. Behaviors may occur alone or in combination, may be subtle in appearance, and may range in severity. Referral to a mental health care professional should be considered as the number and severity of behaviors increase or the concerning behavior is a dramatic change from the student-athlete's normal presentation. Symptoms of the 2 most common mental disorders, depression and anxiety, are found in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 2.

| • Changes in eating and sleeping habits |

| • Unexplained weight loss or weight gain |

| • Drug or alcohol abuse |

| • Gambling issues |

| • Withdrawal from social contact |

| • Decreased interest in activities that have been enjoyable or taking up risky behavior |

| • Talking about death, dying, or “going away” |

| • Loss of emotion or sudden changes of emotion within a short period of time |

| • Problems concentrating, focusing, or remembering |

| • Frequent complaints of fatigue, illness, or being injured that prevent participation |

| • Unexplained wounds or deliberate self-harm |

| • Becoming more irritable or having problems managing anger |

| • Irresponsible, lying |

| • Legal concerns, fighting, difficulty with authority |

| • All-or-nothing thinking |

| • Negative self-talk |

| • Feeling out of control |

| • Mood swings |

| • Excessive worry or fear |

| • Agitation or irritability |

| • Shaking, trembling |

| • Gastrointestinal complaints, headaches |

| • Overuse, unresolved, or frequent injuries |

| Adapted with permission from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. |

Table 3.

Depression Signs and Symptoms60

| Individuals may feel |

| • Sad |

| • Anxious |

| • Empty |

| • Hopeless |

| • Guilty |

| • Worthless |

| • Helpless |

| • Irritable |

| • Restless |

| • Indecisive |

| • Aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems |

| Individuals may present (with) |

| • Lack of energy, depressed, sad mood |

| • Loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed (hanging out with friends, practice, school, sex) |

| • Decreased performance in school or sport |

| • Loss of appetite or eating more than normal, resulting in weight gain or weight loss |

| • Problems falling asleep, staying asleep, or sleeping too much |

| • Recurring thoughts of death, suicide, or suicide attempts |

| • Problems concentrating, remembering information, or making decisions |

| • Unusual crying |

Table 4.

Anxiety Disorders: Warning Signs and Symptoms61

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS THAT MAY AFFECT THE PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH OF THE STUDENT-ATHLETE

Psychological Response to Injury or the Sudden End of the Playing Career

The AT, physician, and coach should always consider the student-athlete's possible psychological response to a physical injury. No matter how minor, it is still a cause of stress to the student-athlete. Each student-athlete is different, so the signs or symptoms described by 1 student-athlete may not be the same as those experienced by another, even with the same injury. Any injury, particularly one that is time limiting, season ending, or perhaps career ending, may be a significant source of stress. Student-athletes respond to injury stress in various ways: Some handle it well, with little effect, whereas others struggle physically or emotionally (or both). A student-athlete who sustains an injury for the first time while participating at the secondary school level will display a learning curve for handling the physical and emotional responses to pain and disability, which the AT can help the student-athlete navigate. During this time of psychological and physical stress associated with an injury, the student-athlete's behavior should be observed. Detecting any symptoms of psychological concern is part of the comprehensive care plan for student-athletes.62

Student-athletes often fear reinjury upon their return to participation. The AT should be aware of this possibility, reassure the student-athlete of his or her readiness to resume participation, and monitor the student-athlete for any symptoms that might indicate a developing psychological problem.63

Concussions

The evolving awareness of concussion sequelae includes the cognitive and psychological effects on student-athletes sustaining this injury.64–69 A student-athlete who sustains a concussion should be monitored for any changes in behavior or self-reported psychological difficulties.

Once a student-athlete experiences a concussion, the school nurse's role is to collaborate with the AT. In the absence of a school AT, the nurse should work to monitor concussion resolution and any psychological changes in the student-athlete.70

Substance and Alcohol Abuse

Total US prevalence11 for substance-use disorders is 11.4%, whereas drug abuse and dependence is 8.9% and alcohol abuse and dependence is 6.4%. With age, there is a 5- to 11-fold increase in the prevalence of these disorders, which tend to be somewhat more frequent in males.71 Of collegiate student-athletes who experienced psychological concerns, particularly depression, 21% reported high alcohol-abuse rates while in high school.72 A total of 86% of US high school students indicated that some classmates drink, smoke, or use drugs during the school day, and 75% of 12- to 17-year-olds said that seeing pictures of teens partying with marijuana or alcohol on social networking sites encouraged other teens to party.73

Despite state laws on the use of alcohol by underaged individuals, student-athletes are exposed to alcohol use in high school. In a collegiate athlete population surveyed for alcohol abuse as well as self-reported depression, anxiety, and other psychiatric symptoms, 21% reported high levels of alcohol abuse and problems associated with it. Significant correlations were found between reported alcohol abuse and self-reported depression and psychiatric symptoms.72

Health care providers should be alert to the possibility of substance and alcohol use among their athletes to avoid enabling them. Having an untreated mental illness (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or ADHD) makes it more likely that student-athletes will use substances or alcohol.74

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Documentation of ADHD

In the adolescent and young adult population, the prevalence of behavior disorders, including ADHD, is 8.7%. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder affects males to females in a more than 3 to 1 ratio. Chronic and impairing behavior patterns result in abnormal levels of inattention or hyperactivity or their combination.11,74 Considered a chronic neurobiological syndrome, ADHD is often characterized by inappropriate levels of either inattention or overactivity and impulsiveness. Athletes sometimes meet the criteria for ADHD in both symptom categories.

According to the DSM-5, the severity of ADHD is determined by the number of symptoms, as well as the level of impairment in social and work functioning. Severe ADHD is present in patients with many symptoms in excess of those required for diagnosis, several symptoms that are severe, or significant impairment as a result of the symptoms. Moderate ADHD is diagnosed in individuals whose symptoms are between minor and severe.

Diagnosing ADHD in children and adolescents can be challenging. Therefore, it is important that all the diagnostic criteria are met using objective data, any comorbid conditions are identified, and other medical conditions that can cause ADHD-like symptoms are considered. Several objective symptom-assessment scales, including the Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales, Vanderbilt Assessment Scales, and Conners Rating Scales, can be completed by parents, teachers, and adolescents and are helpful in evaluating ADHD symptoms.75 Common symptoms of ADHD are found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Signs and Symptoms

| Student-athletes who have symptoms of inattention may |

| • Be easily distracted, miss details, forget things, and frequently switch from 1 activity to another |

| • Have difficulty focusing on 1 thing |

| • Become bored with a test after only a few minutes unless they are doing something enjoyable |

| • Have difficulty focusing attention on organizing and completing a task or learning something new |

| • Have trouble completing or turning in homework assignments, often losing things needed to complete tasks or assignments |

| • Not appearing to listen when spoken to |

| • Daydream, become easily confused, and move slowly |

| • Have difficulty processing information as quickly and accurately as others |

| • Struggle to follow instructions |

| Student-athletes who have symptoms of hyperactivity may |

| • Fidget constantly |

| • Talk nonstop |

| • Dash around, touching or playing with anything and everything in sight |

| • Have trouble sitting still during dinner, school, or traveling (constantly getting up and down in their seat, frequently walking around the bus or plane) |

| • Be constantly in motion |

| • Have difficulty doing quiet tasks or activities |

| Student-athletes who have symptoms of impulsivity may |

| • Be very impatient |

| • Blurt out inappropriate comments, show their emotions without restraint, and act without regard for consequences |

| • Have difficulty waiting for things they want or waiting their turn in line |

| • Often interrupt conversations or others' activities |

| Source: National Institute of Mental Health |

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders affect females twice as often as males, but the incidence in both sexes increases with age. Total prevalence11 is 2.7%. In population-based studies of adults, the estimated lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is relatively low (0.5% to 1.0% for anorexia nervosa and 0.5% to 3.0% for bulimia nervosa).76–84 Youths who do not meet DSM-IV85 criteria for eating disorders of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa fall into a classification of eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS). In the clinical setting, EDNOS tends to be diagnosed more frequently than either anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.85–87

For some athletes, the focus on weight management becomes obsessive, and disordered-eating behaviors develop. Although misuse of substances such as diet pills, stimulants, or laxatives is commonly associated with eating disorders, some athletes may develop a concurrent substance-use disorder.88 Signs and symptoms of eating disorders are found in Table 6.

Table 6.

Eating Disorders: Signs and Symptoms89

| Anorexia nervosa |

| • Extreme thinness (emaciation) |

| • Relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight |

| • Intense fear of gaining weight |

| • Distorted body image, self-esteem that is heavily influenced by perceptions of body weight and shape, or denial of the seriousness of low body weight |

| • Lack of menstruation among girls and women (amenorrhea) |

| • Extremely restricted eating |

| • Compulsive exercise |

| Other symptoms may develop over time, including |

| • Thinning of bones (osteopenia or osteoporosis) |

| • Brittle hair and nails |

| • Dry and yellowish skin |

| • Growth of fine hair all over the body (lanugo) |

| • Mild anemia and muscle wasting and weakness |

| • Severe constipation |

| • Low blood pressure, slowed breathing and pulse |

| • Damage to the structure and function of the heart |

| • Brain damage |

| • Multiorgan failure |

| • Drop in internal body temperature, causing the person to feel cold all the time |

| • Lethargy, sluggishness, or feeling tired all the time |

| • Infertility |

| Bulimia nervosa |

| • Chronically inflamed and sore throat |

| • Swollen salivary glands in neck and jaw |

| • Worn tooth enamel, increasingly sensitive and decaying teeth as a result of exposure to stomach acid |

| • Acid reflux disorder and other gastrointestinal problems |

| • Intestinal distress and irritation from laxative abuse |

| • Severe dehydration from purging of fluids |

| • Electrolyte imbalance (too low or too high levels of sodium, calcium, potassium, and other minerals), which can lead to heart attack |

| Additional source: National Institute of Mental Health |

Bullying and Hazing

Bullying is a type of youth violence and can cause physical, social, emotional, and academic issues. The harm done by bullying not only affects the victim but can also affect friends and families and the overall health and safety of schools and neighborhoods. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines bullying as any unwanted aggressive behavior(s) by another youth or group of youths who are not siblings or current dating partners that involves an observed or perceived power imbalance and is repeated multiple times or is highly likely to be repeated. Bullying may inflict harm or distress on the targeted youth, including physical, psychological, social, or educational harm.90

A young person can be a bully, a victim, or both. Bullying can take place via physical, verbal, or social methods of aggression and can occur in person or through technology (cyberbullying). In athletes, signs of being bullied include the loss of focus, playing or performing tentatively, feeling anxious, dropping out of tournaments or competitions, or quitting sports altogether. In addition, adolescent athletes are frequently reluctant to tell their parents or coaches they have been bullied due to embarrassment, shame, and wanting to remain “part of the team.”91,92

Studies on bullying91,93 revealed that

High school students being bullied on school property totaled 20%, although other studies showed that the overall prevalence of bullying, regardless of location, ranged from 13% to 75%.

A total of 16% of high school students reported they were bullied electronically.

Bullying occurred in 23% of public schools on a daily or weekly basis. A higher percentage of middle school students than high school students described being bullied.

Students reported being verbally bullied (18%), physically bullied (8%), physically threatened (5%), the subject of rumors (18%), and purposefully excluded from activities (6%).

Warning signs that a student is being bullied include the following:

unexplained injuries

loss of personal items

sudden loss of friends

difficulty sleeping

frequent headaches

complaints of stomach discomfort

faking illness or injuries

Warning signs that a student might be bullying others include the following:

frequently getting into verbal or physical fights

having unexplained money or belongings

increasing aggression

having friends who are antagonistic

being overly concerned with popularity

displaying exclusivity in their associates

Best practices would suggest that the AT who suspects a student is either bullying or being bullied first contact the head coach and then the school counselor. The response to this problem is similar to the response required if an AT suspects that an athlete is experiencing a mental health concern. The AT is not expected to directly address the problem with the student and engage in a therapeutic relationship. However, making a referral to the head coach and school counselor ensures that the AT has taken the proper steps to ensure that a school professional has been notified and will address the concern appropriately. It is then the responsibility of the coach and counselor to take the proper steps to investigate and remediate the problem.

Hazing of team members can be viewed as a rite of passage on athletic teams. However, hazing can also be viewed as a part of the bullying spectrum. Hazing is defined as any humiliating or dangerous activity expected of a student who wants to belong to a group, regardless of his or her willingness to participate.94

Studies on hazing in American high schools95–97 revealed that

Of students who belonged to groups, 48% were subjected to hazing activities.

A total of 43% were subjected to humiliating activities.

Potentially illegal acts were performed by 30%.

The first hazing experience took place before age 13 in 25%.

Dangerous hazing activities were just as prevalent in high school (22%) as in college (21%).

Hazing associated with substance abuse increased with age, from 23% in high school to 51% in college.

Males hazed more than females, but both groups described high levels of hazing.

Hazing would not be reported by 36% because there was no one to tell.

Hazing would not be reported by 27% because adults would not handle it correctly.

Hazing resulted in negative consequences for 71%. Consequences included getting into fights; being injured; fighting with parents; doing poorly in school; hurting other people; having difficulty eating, sleeping, or concentrating; and feeling angry, confused, embarrassed, or guilty.

Hazing rituals are frequently dangerous and can often harm relationships among team members. They are not harmless rites of passage used to build closeness or earn respect within the group. These incidents can negatively affect both the victims and the perpetrators. Common feelings that result from hazing include apathy, mistrust, anxiety, depression and isolation, loss of self-esteem and self-confidence, increase in stress levels, and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder.98

REFERRAL OF THE STUDENT-ATHLETE FOR PSYCHOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND CARE

Team Approach

It is useful to have a team in place to address the psychological concerns of student-athletes. This team includes the team physician(s), ATs, school nurses, school counselors, and community-based mental health care professionals (clinical psychologists and psychiatrists). Physicians practicing sports medicine frequently encounter psychological concerns in student-athletes. Physicians also discuss psychological issues with injured student-athletes fairly frequently, although their comfort and perceived competence vary widely.99

School counselors can be an excellent source of information for the AT. If a student has permitted the school counselor to discuss personal information with the AT, as dictated by the local and district policies, the AT can use that information to best serve the student. The AT should meet with the school counseling staff early in the year to obtain information that could be critical in working with student-athletes. Also, in the case of emergent referrals for mental health problems, the AT can obtain the contact information for the local crisis intervention specialists. Also, the AT should meet with the school counselors and school nurse to educate them regarding the symptoms of concussions and postconcussion sequelae. If the school counselors are aware that a student-athlete has sustained a concussion, they can notify the student-athlete's teachers to consider making academic adjustments.

The AT should establish a network within the secondary school and school district:

Make connections and become oriented with the school nurse and school counselor.

Learn the district's policies and procedures for referrals. Discuss a plan of action should a referral be warranted.

Include the nurse and counselor in the referral plan (introducing them if necessary). Ask for their input and feedback on various scenarios. This is no different than the process of creating a required Emergency Action Plan.

The AT must determine what resources are available on campus and when. Many districts provide school nurses and counselors only on certain days of the week and at certain times of the day. An early meeting between the AT and the school-based health team facilitates efficient communication protocols. Knowing when, where, and how to access the school nurse and counselor is essential for the AT to execute a plan of action. In addition, the school nurse and counselor can advise the AT regarding legal limitations, confidentiality considerations, and the school's current plan of action. They will also be able to identify youth mental health resources within the community. The AT and school health team can then expand the plan of action to incorporate the AT's scope of care, protocols for after-school hours, procedures for contacting parents, and district policy regarding contracted employees, as needed. The school health team can also advise the AT regarding situations in which a parent may be the source of the problem or a barrier to the child's access to mental health care. Given that until children reach age 18, legal guardians have the authority to make decisions on virtually all aspects of their health care, relying on the school administration for this type of intervention will be critical.

Depending on the hiring model for the secondary school AT, his or her scope of responsibility may differ. For instance, if the AT is employed by the school or district directly, the role may be different in an on-campus emergency than if the AT is a contracted employee, or vendor, of the school. District administration may need to be consulted for delineation as to what the AT should or should not do in the event of a mental health emergency. This would also be related to mandated-reporter guidelines and whether psychological concerns are included in the list of circumstances for which reporting is required. Consideration should also be given to a game situation versus a practice day. If the AT does not have any assistant ATs (by far the most common scenario), then he or she may need to request assistance from other responsible adults. If a psychological concern occurs during a game, the AT may be unable to continue to maintain the focus on the field or court and may be unavailable to care for an injured player. Identifying an appropriate, qualified, and responsible adult to either handle the mental health emergency or monitor the game for injuries is suggested. In a practice situation, an assistant coach may be able to provide assistance.

Team or family physicians may be called upon to meet with and evaluate a student-athlete for a reported psychological concern. Some physicians prescribe medications to student-athletes for mental disorders and encourage the referral for counseling by a mental health care professional. In many cases, the physician is seeing a student-athlete for a psychological concern on the recommendation of the AT, coach, school nurse, school counselor, or parent. When evaluating and managing a student-athlete with a psychological concern, physicians should rely on their experience but recognize their limits. Physicians collaborating with mental health care professionals can develop the plan of care, including counseling and medication as needed, appropriate for the student-athlete.

In 2010, ATs were surveyed on student-athlete mental health issues.59 Highlights of the survey relative to ATs' comfort in managing student-athlete mental health concerns are provided in Table 7. This consensus statement recommends that each athletic training program consider exploring more educational opportunities in psychology, communication, and critical thinking to enhance the ability of ATs to recognize and refer student-athletes for psychological concerns.100,101

Table 7.

National Collegiate Athletic Association: Managing Student-Athletes Mental Health Concerns59

| • Almost 85% of athletic trainers indicated that anxiety disorders affected their student-athletes |

| • 83% indicated that eating disorders and disordered eating were concerns |

| • Mood disorders (77%), substance-related disorders (69%), and management and treatment (46%) were concerns |

| • 87% were engaged in campus counseling, 71% engaged other athletics personnel, and 66% sought off-campus help |

| • 60% engaged coaches and 23% referred to the 2012–13 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook3 |

| Adapted with permission from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. |

The Preparticipation Physical Examination and the Student-Athlete's Psychological History

The preparticipation physical examination is an optimal time to ask about a history of mental health problems and to screen for common mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety, learning disabilities, and eating disorders. Questions related to nutrition, weight, performance, learning disabilities, eating disorders, and other mental disorders should be included in the health history. The preparticipation physical examination offers an opportunity to ask open-ended questions, demonstrate openness, and destigmatize mental health concerns by including mental health as an important aspect of overall health. Suggestions for mental health questions during the preparticipation physical examination are found in Table 8.

Table 8.

Student-Athlete Preparticipation Medical History: Mental Health-Related Item102

| Statement |

Yes/No |

| I often have trouble sleeping | |

| I wish I had more energy most days of the week | |

| I think about things over and over | |

| I feel anxious and nervous much of the time | |

| I often feel sad or depressed | |

| I struggle with being confident | |

| I don't feel hopeful about the future | |

| I have a hard time managing my emotions (frustration, anger, impatience) | |

| I have feelings of hurting myself or others | |

| Adapted with permission from Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. | |

Any affirmative answers to the mental health questions of the preparticipation physical examination should be brought to the attention of the physician for a discussion with the student-athlete to ascertain whether follow-up evaluation, care, or medication is required. The vast majority of secondary school student-athletes are minors; therefore, parental notification of discussions and referrals is recommended.

Approaching the Student-Athlete With a Potential Psychological Concern

Approaching a student-athlete with a concern about mental well-being can be an uncomfortable experience. However, the health and wellness of the student-athlete is paramount. Before arranging a private meeting with the student-athlete, it is important to have accurate facts, with context, relative to the behavior of concern. The conversation should focus on the student-athlete as a person, not as an athlete. Listening empathetically and encouraging the student-athlete to talk about what is happening are essential. A list of open-ended questions to consider asking the student-athlete to encourage discussion of the situation is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Approaching the Student-Athlete With a Potential Mental Health Concern: Questions to Ask59

| • “How are things going for you?” |

| • “Tell me what is going on.” |

| • “Your behavior [mention the incident or incidents] has me concerned for you. Can you tell me what is going on, or is there something I need to know to understand why this incident happened?” |

| • “Tell me more [about the incident].” |

| • “How do you feel about this [the incident or the facts presented]?” |

| • “Tell me how those cuts [or other wounds] got there.” |

| • “Perhaps you would like to talk to someone about this issue?” |

| • “I want to help you, but this type of issue is beyond my scope as [coach, athletic trainer, administrator]. I know how to refer you to someone who can help.” |

| Adapted with permission from the National Collegiate Athletic Association. |

Table 10.

Suicide Facts and Figures

| Suicide is a preventable public health problem and a leading cause of death in the United States. More investment in suicide prevention, education, and research will prevent the untimely deaths of thousands of Americans each year. |

| General |

| • An American dies by suicide every 12.95 minutes. |

| • Americans attempt suicide an estimated 1 000 000 times annually. |

| • 90% of people who die by suicide have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder at the time of their death. |

| • In 2012, firearms were the most common method of death by suicide, accounting for 50.9% of all suicide deaths, followed by suffocation (including hangings) at 24.8% and poisoning at 16.7%. |

| • For every woman who dies by suicide, 4 men die by suicide, but women are 3 times more likely to attempt suicide. |

| • Over 40 000 Americans die by suicide every year. |

| • Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States. |

| • The combined medical and work loss costs of suicide in the United States each year are $44 billion. |

| • More than 1.5 million years of life are lost annually to suicide. |

| • 50% to 75% of all people who attempt suicide tell someone about their intention. |

| • Suicide rates tend to be highest in the spring months, peaking in April. |

| • In 2010, suicide took more lives than war, murder, and natural disasters. |

| • 90% of those who attempt suicide do not go on to die by suicide. |

| Youth |

| • Suicide is the second leading cause of death for ages 10–24. |

| • The suicide rate among American Indian/Alaska Native adolescents and young adults ages 15–24 is 1.8 times the national average. |

| Adapted with permission from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. |

Table 11.

Suicide: Risk and Protective Factors106

| A combination of individual, relational, community, and societal factors contribute to the risk of suicide. Risk factors are those characteristics associated with suicide; they may or may not be direct causes. |

| Risk factors |

| • Family history of suicide |

| • Family history of child maltreatment |

| • Previous suicide attempt(s) |

| • History of mental disorders, particularly clinical depression |

| • History of alcohol and substance abuse |

| • Feelings of hopelessness |

| • Impulsive or aggressive tendencies |

| • Cultural and religious beliefs (eg, belief that suicide is the noble resolution of a personal dilemma) |

| • Local epidemics of suicide |

| • Isolation, a feeling of being cut off from other people |

| • Barriers to accessing mental health treatment |

| • Loss (relational, social, work, or financial) |

| • Physical illness |

| • Easy access to lethal methods |

| • Unwillingness to seek help due to the stigma attached to mental health and substance abuse disorders or to suicidal thoughts |

| Protective factors buffer individuals from suicidal thoughts and behavior. To date, protective factors have not been studied as extensively or rigorously as risk factors. Identifying and understanding protective factors are, however, as important as researching risk factors. |

| Protective factors |

| • Effective clinical care for mental, physical, and substance abuse disorders |

| • Easy access to a variety of clinical interventions and support for help-seeking |

| • Family and community support (connectedness) |

| • Support from ongoing medical and mental health care relationships |

| • Skills in problem solving, conflict resolution, and nonviolent ways of handling disputes |

| • Cultural and religious beliefs that discourage suicide and support instincts for self-preservation |

Table 12.

Suicide Warning Signs

| Warning signs of suicide: |

| • Talking about wanting to die. |

| • Looking for a way to kill oneself. |

| • Talking about feeling hopeless or having no purpose. |

| • Talking about feeling trapped or in unbearable pain. |

| • Talking about being a burden to others. |

| • Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs. |

| • Acting anxious, agitated, or recklessly. |

| • Sleeping too little or too much. |

| • Withdrawing or feeling isolated. |

| • Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge. |

| • Displaying extreme mood swings. |

| The more of these signs a person shows, the greater the risk. Warning signs are associated with suicide but may not be what cause a suicide. |

| What to do: |

| If someone you know exhibits warning signs of suicide |

| • Do not leave the person alone. |

| • Remove any firearms, alcohol, drugs or sharp objects that could be used in a suicide attempt. |

| • Call the US National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255). |

| • Take the person to an emergency room or seek help from a medical or mental health professional. |

| The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-TALK (8255) |

| A free, 24/7 service that can provide suicidal persons or those around them with support, information and local resources. |

| Adapted with permission from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. |

Table 13.

How to Talk to Someone Who May Be Struggling With Depression or Anxiety

| Don't assume someone will reach out. Only 1 in 5 seeks help. You can encourage them to make that critical first step. |

| 1. Ask if you can talk in private. |

| 2. Ask questions to open up the conversation. |

| • How are you doing? |

| • You haven't seemed yourself lately. Is everything okay? |

| • Is anything bothering you? |

| 3. Listen to their story, and express concern and caring. |

| 4. Ask if they have thought about hurting themselves or ending their life. |

| 5. Encourage them to seek mental health services. Tell them seeking help can take courage, but it's the smart thing to do. |

| Avoid: |

| • Minimizing feelings. |

| • Advice to fix it. |

| • Debating on the value of life. |

| • Offering clichés. |

| Do: |

| • Listen. |

| • Express concern and caring. |

| • Ask open-ended questions. |

| • Talk about suicide openly and directly. |

| If they are considering suicide: |

| • Take the person seriously. |

| • Tell them to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-TALK (8255). |

| • Help them remove lethal means. |

| • Escort them to an emergency room, counseling service, or psychiatrist. |

| Adapted with permission from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. |

Table 14.

Helping Survivors of Suicide107

| The loss of a loved one by suicide is often shocking, painful, and unexpected. The grief that ensues can be intense, complex, and long term. Grief and bereavement is an extremely individual and unique process. |

| There is no given duration to being bereaved by suicide. Survivors of suicide are not looking for their lives to return to their prior state because things can never go back to how they were. Survivors aim to adjust to life without their loved one. |

| Common emotions experienced with grief are |

| • Shock |

| • Pain |

| • Anger |

| • Despair |

| • Depression |

| • Sadness |

| • Rejection |

| • Abandonment |

| • Denial |

| • Numbness |

| • Shame |

| • Disbelief |

| • Stress |

| • Guilt |

| • Loneliness |

| • Anxiety |

| The single most important and helpful thing you can do is listen. Let them talk at their own pace; they will share with you when (and what) they are ready to. Be patient. Repetition is a part of healing, and as such, you may hear the same story multiple times. Repetition is part of the healing process, and survivors need to tell their stories as many times as necessary. You may not know what to say, and that's okay. Your presence and unconditional listening are what a survivor is looking for. |

| Survivors of suicide support groups are helpful to survivors to express their feelings, tell their stories, and share with others who have experienced a similar event. These groups are good resources for the healing process, and many survivors find them helpful. Please consult our Web site (www.suicidology.org) for a listing of support groups in or near your community. |

| Additional resources |

| • Survivors of Suicide (www.survivorsofsuicide.com) |

| • Suicide Awareness: Voices of Education (SAVE; www.save.org) |

| • American Foundation of Suicide Prevention (AFSP; www.afsp.org) |

| Adapted with permission from the American Association of Suicidology. |

Encouraging a student-athlete to consider a mental health evaluation can be challenging, given the stigma that is still sometimes attached to receiving mental health care.103 Student-athletes experience as much or more psychological distress as nonathletes; however, they use professional mental health services less than nonathletes.104

Pointing out that mental health is as important as physical health is one line of reasoning that may persuade the reticent student-athlete to seek help for a psychological concern. Assisting the student-athlete in accessing the mental health care system at the secondary school or community through prearranged services eases the transition from deciding to seek help to meeting a mental health care professional.

Confidentiality

In approaching student-athletes with questions of concern, it is important to notify them of the limits of confidentiality. Those ATs who have established a rapport with their athletes may be successful in making a student feel comfortable enough to discuss personal problems. However, it is important for the AT to explain the limits of confidentiality during the conversation. If a student discusses a personal concern that becomes an emergent psychological concern, then the AT is mandated by state law to follow the procedures set forth by the secondary school district.

Once the student-athlete has been approached and agrees to go for a psychological evaluation or self-reports wanting to be evaluated for a psychological concern, he or she should be referred as soon as possible. In most cases, unless there is an imminent risk of harm to themselves or others or a code-of-conduct violation has taken place, student-athletes cannot be compelled to report for a mental health evaluation. When a student-athlete is reticent to undergo a mental health evaluation, the AT may make the following suggestions:

Express confidence in the mental health profession.

Clarify what counseling is and how it could help the student-athlete's overall health.

Emphasize the confidential nature of mental health care and referral.

The question of whether to inform the student-athlete's parents or coach invariably arises. The AT should emphasize that parents and coaches are concerned about the welfare of the student-athlete and that informing them about psychological health is no different than informing them about physical health. The AT should encourage the disclosure but not insist. Due to the minor age of most secondary school student-athletes, secondary school districts must develop referral protocols for psychological concerns to ensure compliance with state law regarding the care of minor children. This includes emergent mental health care evaluations in the event of a threat or actual incident of self-harm, harm to others, or destruction of property.

Suicide in Student-Athletes

Approximately 4700 young people between the ages of 14 and 24 die by suicide annually in the United States.105 In addition, 1 in 6 high school students seriously consider attempting suicide, and 1 in 13 high school students attempt suicide 1 or more times.105 Suicide facts and figures (Table 10), suicide risk and protective factors (Table 11), suicide symptoms and danger signs (Table 12), steps to take when fearing that a person may take his or her life (Table 13), and information on surviving the loss of a loved one to suicide (Table 14) are supplied to assist in developing a plan.

Emergencies and Catastrophic Incidents in Student-Athletes With Psychological Concerns

Although psychological concerns in student-athletes rarely result in a medical emergency (ie, injury to themselves or others) or a catastrophic event (ie, suicide, homicide, permanent disability), it is prudent to plan for such circumstances.

The following guidelines may be included in the emergent mental health emergency response plan (as approved by the school district):

Respond with empathy and support

Enact the school crisis response plan

Notify the student crisis team

Identify the level of intervention or referral needed (emergent, urgent, less urgent, or nonurgent) and remember that not all mental health concerns require referral

Ensure safety and err on the side of safety

Collaborate with colleagues

Mobilize the student's support system (including family)

Connect immediately with the appropriate resources

Follow up on the referral

In the event of a medical emergency resulting from an injury to the student-athlete with a psychological concern or to others, the Emergency Action Plan for that venue should be implemented immediately. The “National Athletic Trainers' Association Position Statement: Emergency Planning in Athletics”9 should be consulted when developing an athletic department Emergency Action Plan.

Crisis Counseling for Student-Athletes

Traumatic events have the potential to simultaneously evoke both human resilience and distress.107–109 Student-athletes may be exposed to a variety of potential traumatic stressors in the course of their athletic pursuits as well as in the course of their daily lives. Examples of traumatic events common to students include death of or injury to friends or family members, exposure to suicide in the community, significant motor vehicle crashes involving the athlete or friends, exposure to violence, and significant injury during athletic events. These examples illustrate the variety of events that can cause a traumatic stress reaction (including grief), even if the student-athlete was not directly affected.110

Stress reactions to a traumatic event are typically normal human reactions. Many, if not most, of these reactions are self-limiting and will resolve with support, time, and natural resilience. Recognition that an individual needs formal assistance is based on the level of distress that the student-athlete experiences and, most important, the degree to which that distress impairs his or her ability to function in any domain (eg, school performance, athletic performance, relationships). Initial reactions are often limited, and it is normal to experience temporary disruptions in daily functioning during times of traumatic stress. However, when a reaction persists, referral for mental health support is indicated. Early intervention with mental health care is more effective in resolving traumatic stress than a prolonged period of waiting.110

In the first days to weeks after a traumatic event, common reactions are intrusive thoughts and images of the event; periods of emotional numbing alternating with periods of heightened emotions; and anxiety symptoms including trouble sleeping, irritability, changes in appetite, fatigue, and an increase in general tension. Individuals differ in their rate of recovery from these initial signs of distress. Reactions that warrant immediate referral for evaluation include significant use of alcohol or substances to manage distress, suicidal thinking, thoughts of harming others, and severe panic.111 Severe physical stress reactions (ie, repeated fainting, chest pain, difficulty breathing, persistent vomiting, severe persistent insomnia) are not common, and student-athletes with these problems should be immediately referred to a medical professional.

The AT is in a unique position to be helpful during and after a traumatic incident. The AT's relationship with the student-athlete offers the opportunity to provide support and recognition of the need for referral to formal mental health support. The traumatic stress literature has identified several actions that can be taken to support those who have suffered a traumatic event.110

Hobfoll et al111 outlined the essential elements of psychological first aid: (1) promote a sense of safety, (2) promote calming, (3) promote self-efficacy and collective efficacy, (4) promote connectedness, and (5) promote hope. These 5 elements can be accomplished through active listening and crisis support, along with knowledge of the available resources for referral.

Referral resources after a traumatic event should be used for students of concern. These personnel should be trained in traumatic stress counseling as well as grief management to provide the student with appropriate professional support. Ideally, the resources available for student-athletes after traumatic events should be identified in advance to allow for more effective referral in a crisis.

Legal Considerations in Developing a Plan for Psychological Concerns in Student-Athletes

The majority of student-athletes at the secondary school level are below the legal age of 18. This means that the secondary school student-athlete must be considered of minor age, and therefore, appropriate measures must be practiced to comply with state laws. Legal considerations promote the idea that an interdisciplinary approach, including individuals in various positions within secondary schools, and when necessary, outside resources, should be a goal in confronting the complex subject of mental health and the student-athlete.

Legal liabilities vary from state to state, and health care providers, including ATs, should apprise themselves of the applicable state laws. The AT has the duty to conform to the standard of care required of the profession by exercising reasonable care for the health and safety of student-athletes.