Abstract

Context:

Many newly credentialed athletic trainers gain initial employment as graduate assistants (GAs) in the collegiate setting, yet their socialization into their role is unknown. Exploring the socialization process of GAs in the collegiate setting could provide insight into how that process occurs.

Objective:

To explore the professional socialization of GAs in the collegiate setting to determine how GAs are socialized and developed as athletic trainers.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

Individual phone interviews.

Patients or Other Participants:

Athletic trainers (N = 21) who had supervised GAs in the collegiate setting for a minimum of 8 years (16 men [76%], 5 women [24%]; years of supervision experience = 14.6 ± 6.6).

Data Collection and Analysis:

Data were collected via phone interviews, which were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were analyzed by a 4-person consensus team with a consensual qualitative-research design. The team independently coded the data and compared ideas until a consensus was reached, and a codebook was created. Trustworthiness was established through member checks and multianalyst triangulation.

Results:

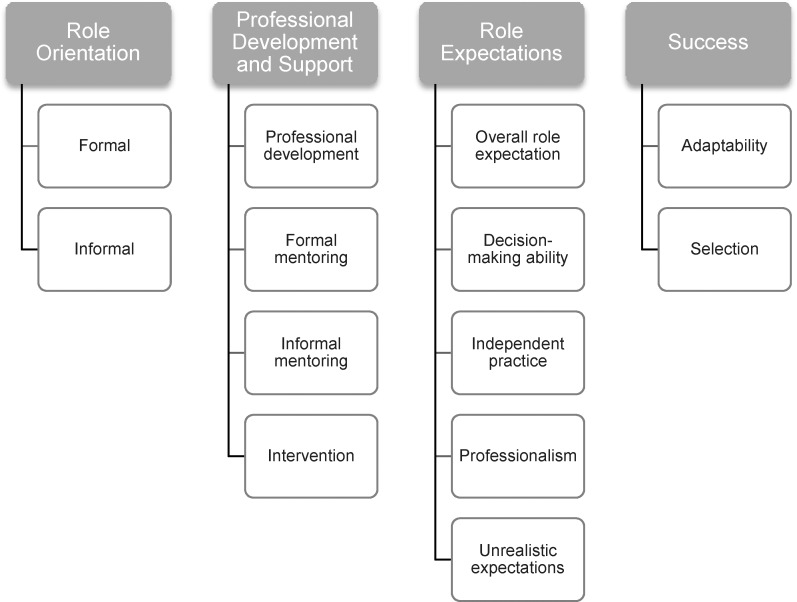

Four themes emerged: (1) role orientation, (2) professional development and support, (3) role expectations, and (4) success. Role orientation occurred both formally (eg, review of policies and procedures) and informally (eg, immediate role immersion). Professional development and support consisted of the supervisor mentoring and intervening when appropriate. Role expectations included decision-making ability, independent practice, and professionalism; however, supervisors often expected GAs to function as experienced, full-time staff. Success of the GAs depended on their adaptability and on the proper selection of GAs by supervisors.

Conclusions:

Supervisors socialize GAs into the collegiate setting by providing orientation, professional development, mentoring, and intervention when necessary. Supervisors are encouraged to use these socialization tactics to enhance the professional development of GAs in the collegiate setting.

Key Words: professional development, orientation, mentoring, qualitative research

Key Points

Supervisors believed graduate assistantships were important in the professional growth of new athletic trainers to help transition them into clinical practice.

Several processes were used to socialize graduate assistants into their roles in the collegiate setting, including orientations and providing mentorship and support.

Supervisors were responsible for professionally developing graduate assistants, but several supervisors had unrealistic expectations for graduate assistants to practice as full-time staff and experienced athletic trainers.

Graduate assistantships are an important part of the professional and educational development of athletic trainers (ATs) and, for many, are rites of passage into the collegiate setting.1 Graduate assistant athletic trainers (GAs) have met all credentialing requirements to provide patient care, but having complete autonomy and decision-making power may be a new experience for them. As new professionals transition from being supervised students to autonomous clinicians, part of their success may depend on the way they are socialized into their new positions.2 However, the socialization of GAs, as newly credentialed ATs, into their roles has not been described. More specifically, little is known about the role of the supervisor in providing development and supervision to the GAs throughout the socialization process or the tactics supervisors use to socialize the GAs into their roles as new practitioners. Recently, the National Athletic Trainers' Association Executive Committee on Education recommended exploring the employer's responsibility in the development of newly credentialed ATs.3 Insight into how employers help develop and support GAs could lead to models for transitioning new ATs into practice.

One way to develop and support new GAs is through organizational professional socialization. Professional socialization is the process by which an individual learns the roles and responsibilities of the position while acquiring knowledge, skills, and attitudes associated with the profession.4–6 Socialization is the method by which new employees or students are oriented into a new position and the experiences of socialization, which help foster the employees' professional identity.7 Organizational socialization occurs after the individual enters the organizational setting in which the individual is able to learn and adapt to the position.1 In the collegiate setting, organizational socialization can be very complicated because it involves learning the particular culture and roles within the organization, which vary depending on the setting.1,6,8 Individuals learn and adapt to their positions through socialization and mentoring. Formal training can also facilitate that process.1 Recently, a qualitative study2 examining the role of clinical teachers in the professional socialization of newly graduated nurses found the success of socialization largely depended on the extent of mentoring and support the new nurses received from preceptors. Socialization can produce both positive (eg, success, growth, enrichment) and negative (eg, role instability) effects. These effects can determine the success or failure of that individual.1

Although a great deal of research has focused on professional socialization of experienced ATs in the collegiate and high school settings, it is unclear how GAs in the college/university setting are socialized into their roles. Our purpose was to explore the professional socialization of GAs in the collegiate setting to determine how GAs were socialized and how they developed as ATs. Our research questions were the following: (1) What processes are used to socialize GAs into the collegiate setting? (2) What are the expectations of GAs within the collegiate setting? (3) What is the supervisor's role in developing the GA?

METHODS

This study employed a consensual qualitative-research approach, which used a research team (the 4 authors) to reach a consensus interpretation of data. The theoretical framework of this study was symbolic interactionism, which emphasizes how the interaction, culture, and environment shapes and develops an individual and how that individual constructs meaning from his or her experience.9 During the professional socialization process, GAs continuously interact with others and their environment as they transition from being students to new professionals. Because of that constant and dynamic interaction, professional socialization is grounded in symbolic interactionism.1 We used the consensual qualitative-research approach because the multianalyst triangulation would give us a clearer picture of the constant and dynamic interaction of professional socialization.

Institutional review board approval was obtained before initiating this study. Interviews were conducted using a semistructured format guided by a questionnaire. Before beginning the study, all participants' questions were addressed, and participants provided informed consent.

PARTICIPANTS

Inclusion criteria for this study consisted of being an athletic trainer who had supervised GAs for a minimum of 8 years in the collegiate setting. Eight years was chosen to ensure that the participants had a wealth of experience in supervising GAs. We elected to examine only collegiate GAs because we wanted to interview supervisors who worked closely with GAs. We also wanted to limit the study to 1 group of GAs instead of expanding to all GAs (eg, clinic, high school setting) at this time. We recruited participants via an e-mail from the Board of Certification (Omaha, NE), which was sent to all 3138 ATs who were identified as employed in the college setting and certified for at least 10 years. We chose ATs with 10 years of experience because, at minimum, in a 10-year period, an individual could have 2 years of graduate assistantship experience and 8 years supervising GAs in the collegiate setting. In addition to the recruitment e-mail, we asked participants to provide the names of colleagues who fit the inclusion criteria. Twenty-one ATs (16 men [76%], 5 women [24%]; years of supervisory experience = 8–33 years; mean ± SD = 14.6 ± 6.6 years; total GAs supervised by all participants = 800+) participated in this study. Individual participant demographics are presented in Table 1. Interviews were conducted until data saturation, which occurred when no new relevant information emerged, and no additional data needed to be collected.10

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Participant Pseudonyms |

National Collegiate Athletic Association Division |

Job Title |

Time in Setting, y |

Time Supervising Graduate Assistants, y |

Graduate Assistants Supervised, No. |

| Adelaide | I | Head AT | 11 | 12 | >30 |

| Ann | II | Assistant AT | 13 | 11 | 15 |

| Bob | I | Head AT | 26 | 18 | >30 |

| Franklin | I | Assistant AT | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| Gary | III | Head AT | 17 | 16 | >15 |

| Gob | I | Head AT | 20 | 8 | >15 |

| Greg | I | Head AT | 23 | 23 | >103 |

| Kitty | I | Associate AT | 25 | 24 | >100 |

| Larry | I | Head AT | 11 | 11 | 6 |

| Lindsay | I | Associate AT | 10 | 10 | 30 |

| Lionel | II | Head AT | 21 | 10 | >20 |

| Maggie | I | Head AT | 10 | 10 | >90 |

| Michael | II | Head AT | 16 | 14 | 10 |

| Mort | III | Head AT | 24 | 22 | 12 |

| Paul | II | Head AT | 23 | 18 | 30 |

| Stan | II | Head AT | 12 | 11 | 6 |

| Stefan | I | Clinical supervisor | 8 | 8 | 45 |

| Steve | I | Head AT | 11 | 8 | >10 |

| Ted | III | Clinical coordinator and supervisor | 11 | 15 | 15 |

| Tobias | I | Director of athletic training services | 22 | 18 | >80 |

| Wayne | I | Head AT | 38 | 33 | >120 |

Abbreviation: AT, athletic trainer.

Procedures

Supervising ATs who fit the criteria and were interested in participating in the study responded via e-mail or phone to the primary investigator (A.B.T). The primary investigator then contacted the supervisors via phone to explain the study, confirm inclusion criteria, obtain consent, gather demographic information, and schedule an interview. Data were collected via semistructured phone interviews that lasted approximately 60 minutes. The semistructured interview questions (Table 2) were based on our research questions as well as prior socialization research.1,4,11,12 The interview questions were designed to explore the meanings and processes of socialization and allowed for follow-up questions as needed. To ensure clarity, we pilot-tested the interview questions with 2 supervisors who fit our inclusion criteria. The data from the pilot study were not included in the final analysis. The primary investigator conducted all interviews. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews were conducted until data saturation occurred.

Table 2.

Semistructured Interview Guide

| 1. Would you please describe for me your current role in relation to the GAs at your institution? |

| 2. How many athletic training GAs do you currently employ at your institution? |

| 3. How do you feel GAs prepare themselves for their roles at your institution? |

| 4. Can you explain the mentoring process for new GAs at your institution? |

| 5. How are the GAs oriented to their roles at your institution? |

| a. Is this orientation different from the orientation you received when beginning this job? How so? |

| 6. How long does it typically take for GAs to be successfully oriented into their position? |

| a. What do you feel contributes to the length of this process? |

| 7. Discuss the expectations you have for GAs in regard to clinical skills. |

| 8. Discuss the expectations you have for GAs in regard to interpersonal skills. |

| 9. What do you feel contributes to the GAs' ability to fulfill obligations or keeps them from fulfilling obligations? |

| 10. Do your expectations (or obligations) change during their second year? |

| 11. How does socialization change during their second year? (eg, Do GAs assist in helping to mentor or socialize the first-year GAs? Do second-year GAs obtain any additional roles?) |

| 12. What shortcomings do you feel the GAs have? |

| 13. What processes are in place to help GAs improve their shortcomings? |

| 14. What challenges do GAs face during their first year as a GA? |

| 15. Are there skills (clinical or interpersonal) that you wish were better? |

| 16. Is there something that you feel should be implemented into the educational preparation of students to better prepare them to transition into being a GA? |

| 17. What advice would you give to an individual about to enter the collegiate setting as a GA? |

Abbreviation: GA, graduate assistant.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

The authors formed a 4-person consensus team, which consisted of the primary investigator and 3 other ATs with experience in qualitative research. The research team had more than 35 years of collective experience with qualitative methods and had a strong understanding of professional socialization. Data were analyzed using the consensual qualitative-research approach. Consensual qualitative research uses multiple researchers to reach a consensus about the data and uses auditors to check for accuracy.13 Each member of the research team independently performed open coding on 3 transcripts.10 We then compared ideas until a consensus was reached, and a codebook was created. Using that codebook, we individually coded a fourth transcript to ensure the codebook was accurate. The primary investigator then coded the remaining transcripts. Three randomly selected coded transcripts were sent to each team member for cross-analysis to ensure the codebook was complete and the transcripts were coded correctly. Another randomly selected coded transcript was then sent to an independent auditor, an AT with experience in qualitative research, to analyze the domains and core ideas to ensure reliability.

Trustworthiness was established through narrative-accuracy member checks, which allowed participants to review their transcripts for accuracy and make clarifications and changes as necessary. Trustworthiness was also established through the use of consensual qualitative research, which enables a research team to consider multiple perspectives to reach a consensus on the data.13 By using a research team, we reduced the bias inherent in analysis with 1 researcher. Pseudonyms were used to protect the identities of the participants.

RESULTS

Four themes emerged from the findings that described the participants' perceptions of professional socialization of GAs in the collegiate setting: (1) role orientation, (2) professional development and support, (3) role expectations, and (4) success. These themes were further broken down into subcategories (Figure).

Figure.

Emergent themes and subthemes of supervisors' perspectives of the professional socialization of graduate assistants.

Role Orientation

The first theme that emerged was role orientation. This theme can be broken into 2 subcategories: (1) formal and (2) informal. Each participant reported an orientation for GAs, whether formal or informal. Formal orientation included information dissemination (eg, policies and procedures) and structured activities for the GAs with specific outcomes (eg, becoming certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation). Informal orientation included activities that were unstructured and more individualized,14 such as the GAs shadowing their supervisors or immediate role immersion.

Formal Orientation

Many supervisors reported that formal orientation started at the interview, when supervisors outlined clear expectations so that a GA would know the role and what to expect. Before the starting date, many supervisors provided the GAs with policy and procedure information, the AT staff manual, and additional orientation information, such as expectations and the starting date for employment. On-campus, formal orientation ranged from 2 days to 2 months before any patient-care responsibilities. Most commonly, the GAs arrived 1 to 2 weeks before beginning patient care and participated in various orientation activities (Table 3). One of the principal parts of the orientation was relaying the supervisors' expectations of GAs, such as clinical coverage, attire, and professional communication. Paul stated, “Orientation pretty much spells out our expectations.” Tobias concurred: “They know what all of the expectations are. Coming in, we are pretty clear.” Although GAs learned a great deal of information during formal orientation, many participants reported that formal orientation was insufficient for the GAs to learn everything they need to know.

Table 3.

Educational Components of a Formal Role Orientation

| • Policy and procedures manual |

| • Preceptor expectations |

| • Emergency action plan |

| • Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator recertification |

| • Insurance protocol |

| • Electronic medical record keeping and documentation |

| • Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| • Occupational safety and health |

| • Concussion baseline-testing protocol |

| • Preparticipation physical examination protocol |

Informal Orientation

Each participant used informal orientation (eg, shadowing the assigned mentor or other staff member or immediate role immersion) throughout preseason to supplement the formal orientation. Lionel used both formal and informal orientation but found GAs adapted faster with informal orientation, commenting “GAs are more comfortable being oriented on a personal level.” Participants stated that GAs assigned to a spring sport typically spent time in the fall shadowing and assisting ATs with teams, such as football, until their sport started. This provided interactions with other GAs and full-time staff as well as time to adapt and the opportunity to ask questions and to learn their role more informally. Lindsay discussed GAs' formal introductions to the policies and procedures of the institution but then shadowing a staff member to help the GAs adapt to their new roles: “As the GAs demonstrate they are capable, the staff member turns over control [of that sport].”

Graduate assistants were also informally oriented to their roles through immediate role immersion. As Bob noted, “We bring them in and just throw them to the fire. I don't believe they learn it until they actually have to do it.” Larry remarked, “I think [orientation] gives them an idea of what to expect, but you are not going to see until you have been in it, until you really get a chance. You tell someone what to expect, but until you really experience it [you will not understand].” Many other participants also reflected on this type of orientation. Gary stated,

We throw them in. It wasn't quite sink or swim, but you had to stand on your tiptoes at times. We essentially let them fumble around on their own. We didn't really have a lot of time to get them comfortable [making decisions]. They showed up on a Monday, practice started on Wednesday, and they had to get going.

Franklin found that the faster GAs were immersed, the faster they became oriented and adapted to their roles, but 1 negative aspect of immediate role immersion was that some topics were not addressed. Franklin said, “Sometimes [GAs] fall through the cracks in terms of how to order x-rays, [magnetic resonance imaging], that kind of stuff.”

Professional Development and Support

The second theme that emerged was professional development and support. The participants felt that a large part of the GA socialization process was the supervisor's role in supporting and developing the GA. This theme of development and support is described in the following subcategories: (1) professional development, (2) formal mentoring, (3) informal mentoring, and (4) intervention.

Professional Development

Professional development was a large aspect of the socialization of GAs for many participants. Professional development refers to the supervisor's role in improving and building on the GA's athletic training skills (eg, evaluation, injury management, rehabilitation, administration). Many participants had weekly or monthly meetings to professionally develop the GA by providing feedback on cover letters and resumes, help with job searching and interview techniques, and teaching new skills, such as muscle energy techniques, Graston technique, or Kinesio taping. Maggie reported it was important for the GAs “to have everything they need to be more marketable than the next person.” Participants felt they had an important role in developing and supporting the GAs. Wayne knew the institutions and AT services were responsible for providing GAs with a positive learning experience to help them develop professionally. He explained,

We give them 2 more years of clinical experience in an academic setting. For a GA to be successful, it has to serve both parties equally. In a lot of GA settings, the institution is not taking responsibility to fulfill [its] end of it. Their goal is to get free help, or cheaper help, rather than hiring full-time assistants. If we are going to use the skills and the license[s] of these people, we truly have an obligation to provide for them a truly useful academic experience, a very useful clinical experience that will provide professional growth, and we have to give them an acceptable life experience.

Participants developed the GAs in many ways, such as arranging learning and professional development experiences for the GAs based on their needs. Adelaide described,

If [GAs] want experience working with a different sport, I will arrange for them to cover a tournament. If the [GA] wants more rehabilitation experience, I will find an athlete with a specific need and mentor the GA through that rehabilitation process. If [GAs] want more experience with administration, I will train them through the insurance process. If they are weak with evaluation skills, I will put them in a clinic where they will do evaluations all day long. It is not fair for the person, if I don't meet what they are trying to accomplish.

Kitty also stressed the importance of helping her GAs to develop professionally:

When they get here, their clinical skills go up because we retrain them in everything. We teach them to think very differently. We teach to think outside of the box; we teach them to think holistically. We train them to think differently and that changes their skills. Go to the [AT] program that is going to develop you as a person, not just be at a program where you are going to take care of your sport and that is it.

Formal Mentoring

Another way the participants supported the GAs was through formal mentoring, which involved planned developmental meetings between the GA and an assigned staff member or weekly meetings with the entire staff (or both). Adelaide stated,

Each GA is assigned to a full-time AT to oversee them on their injury reports. GAs have someone who is going to be around when their sport is going on, so they have the opportunity to ask questions, seek advice, review whatever policy and procedure they need to review.

The GAs could not remember everything that they learned at orientation, so the formal mentoring helped to fill in the gaps. Many participants reported weekly staff meetings or one-on-one meetings with the GAs (or both) to talk about any patient or clinical concerns, to review patient cases, and to provide feedback. Tobias noted, “We do a good job mentoring them so they know what is coming next and they are not surprised, and they are not left out alone to make each mistake. They get a ton of feedback.”

Lindsay also commented on the mentoring process at her institution, saying “mentors meet with their GA almost daily to check in and see how everything is going, providing feedback, plan[ning] for the next day, etc.”

The length of the formal mentoring depended on the institution and the GA. Stan mentored the GAs until he felt they were comfortable with autonomous practice, whereas at other institutions, the formal mentoring lasted the duration of the assistantship. At some institutions, the mentoring started formally with daily interactions but then became more informal as the GAs gained comfort in their roles. Michael explained, “For the first month, the GA shadows [the supervisor] and the mentoring is initiated by the supervisor. After a little while, the balance changes and then the mentor backs off a bit and the GA is the initiator.”

The mentoring dynamic also depends on what the GA needs. Ann described, “Sometimes they just need someone to ask questions to. Sometimes they need someone to be around all of the time. It just depends on the person.”

Informal Mentoring

Along with the formal mentoring, many participants reported mentoring the GAs informally throughout their assistantships. Informal mentoring consisted of unplanned interactions between the GA and a staff member who was not assigned to mentor that GA. Ted explained that the mentoring process at his institution was more informal: “The mentoring process kind of evolves organically and often if the GA seeks [mentoring] out.” Many participants reported having a family-like atmosphere for the GAs, and many mentoring relationships evolved naturally over the course of the assistantship. All participants reported having an open-door policy with their GAs, so if the GAs needed anything, the supervisors would be there to help. Kitty remarked, “We have a huge open-door policy. They know I say that they can come into my office and they can get a hold of me on my cell phone at any time.” Larry concurred: “We have an open-door policy because our ATR [athletic training room] is so small our GAs can come talk to us at any time with issues that they have.” Franklin stated, “I am there as a resource in case they come up with something they are unfamiliar with. I am there as a sounding board and as a response for them if they are in over their heads.” Greg noted, “I will be there to answer questions and help the GAs with problems when they make me aware of them.”

Intervention

Another important aspect of the program's role in developing the GAs was intervening when the GA was not fulfilling expectations or they had weaknesses that affected patient care. Intervention occurred when the supervisors stepped in on behalf of the patient, coach, or athletic training services to address concerns or mistakes. Most participants reported they would pull the GA aside and discuss a specific situation or event and provide feedback for improvement. Ann believed the biggest aspect of intervention is an open line of communication: “The biggest thing again is the open communication that we are all here to help you get better.” Most problems were solved by communication, but there were times when the participants had to further intervene with their GAs. When needed, participants reported they put GAs on performance-improvement plans to improve areas of weakness both clinically and academically, conducted in-service sessions to improve clinical skills, or sent GAs to human resources classes to remedy areas of weakness in professionalism or communication.

Maggie commented, “I usually will try to find a class that human resources offers on professionalism or communicating with tact or aggressive versus assertive.” Many participants decreased the GA's clinical time and increased his or her academic-development time. Tobias described, “We would decrease the time in patient care and increase the GA's clinical education time.” Some participants reported they did not have a specific process in place because it has not been necessary. Stefan explained, “I don't have a process in place. I do that on an individual basis. Remediation or with issues with disciplinary stuff [is something] that we haven't had to deal with at the graduate level.” Regardless of how they intervened, many supervisors discussed the importance of reinforcing the GA's confidence. Adelaide reported, “I think it important to point out what they did well. ‘Keep up the good work here,' and ‘I saw some improvement here,' and ‘maybe this is how you can continue to improve in this particular area.'”

Role Expectations

The third theme that emerged was role expectations, with 5 subcategories: (1) overall role expectation, (2) decision-making ability, (3) independent practice, (4) professionalism, and (5) unrealistic expectations.

Overall Role Expectation

Overall role expectation refers to the participant's expectations of the GAs in regard to their role. Many participants expected new GAs to be competent practitioners at the level of a new health care professional. Ann stated, “We don't expect them to be at the same level [as] someone who has been doing this for 10 years, but we do expect them to have a good basic understanding of entry-level skills.” Kitty agreed: “I expect them to know and be confident with injury prevention, management, etc, at a level high enough to pass the BOC [Board of Certification examination].” Although the supervisors expected them to be competent, they also expected the GAs to fail sometimes. Wayne remarked, “You cannot expect a professional to be correct 100% of the time. It just doesn't happen. You have to have the ability to fail safely and then deal with the consequences.”

In addition to providing competent patient care, the participants expected the GAs to keep an open mind, to be willing to continually learn new techniques, and to respond well to feedback. Steve asks GAs to

…bring their undergraduate education, but also don't be afraid to learn something new. Don't just rely on what you did at the undergraduate level or criticize what is being done at your institution. Be open to new methods, new ways, learn, use your abilities, have confidence in yourself, but don't be overconfident. Be prepared to work hard and learn on the fly and adjust your beliefs to meet the needs of your environment.

Decision-Making Ability

Another role expectation of GAs was to make decisions in regard to patient care and the role as a GA, which is critical to success. Wayne noted,

As they come into my program, I stress to them, or my emphasis to them is, to make a decision. Whatever that decision is, there is no such thing as a wrong decision, in my opinion. There are some decisions that are more appropriate than others, but the only wrong decision is no decision because there is no defense for no decision. Make decisions, but always, always have a reason for that decision, and be able to explain why that decision was made.

Ann also expressed the importance of making decisions:

We want you to make decisions. We want you to be in charge of your team, but we want you to ask questions. There are times when you might not know what to do, and that is OK, to not know everything. But be involved and take ownership in wanting to be better.

Not only did the participants expect GAs to make decisions, but they also expected them to make the wrong decision sometimes. Tobias commented, “Someone who isn't making any mistakes really isn't making a lot of decisions.”

Independent Practice

Another role expectation that emerged frequently was the ability of the GAs to practice independently without needing a supervisor present. Wayne described, “They are expected to be autonomous, licensed, and certified professionals. Their days as student[s] are over.” Larry agreed: “They have total control over their sport. They are doing all of the injury reports. They are doing all of the rehabs. They travel to games. Then, they have to switch sports because they have a fall and spring sport.” Greg also expected autonomous practitioners, saying, “Everyone is busy and has their own sport to cover so the staff is not looking over the GA's shoulder.”

Although most supervisors expected the GAs to be able to function autonomously at the beginning, Tobias did not share this expectation. He explained, “But my expectation has never been that a 22 year old should be able to be 100% on [his] own. If we wanted someone to be 100% on their own, we would hire a full-time staff [person].” He did, however, expect the GAs to gain autonomy and independence during their training:

Second years are expected to be much more autonomous. We want them to be more independent and not check in quite as much. We want them to come to us [full-time staff] with challenges but also a solution in mind. The first year, they have a little more guidance.

Many other participants felt second-year GAs should be more autonomous because they had a year of experience working in their position. Franklin believed, “They should be able to function fully. I mean I don't want to say fully, but they should be able to handle 90% of the problems on their own.”

Professionalism

Graduate assistants were also expected to display a high level of professionalism, which includes maturity, maintaining open lines of communication, forming appropriate relationships with athletes and coaches, and promoting athletic training and their institutions. Maggie held her GAs to a high standard because they were graduating from a program that had her name on it. She remarked, “I hold very high standards for them because when they leave here, this is my alumni program when they leave here, they are leaving a program that essentially has my name on it. I hold them to high standards.” She expected them to act professionally and appropriately and to communicate with her if there was ever a problem. Most of the participants (86%) also expected their GAs to communicate professionally with coaches, student-athletes, physicians, parents, supervisors, and peers. This professional communication involved the ability to articulate clearly, act with maturity, and treat other parties with respect. Lindsay reported,

They need to be able to communicate specifically with staff and physicians. They need to be able to break it down in nonmedical terms for an athlete and a coach but also be able to switch back and talk to a physician and sound like that competent medical professional.

Supervisors also expected the GAs to communicate calmly and treat people with respect. Building rapport with athletes and coaches was a vital part of being a GA.

Other professional expectations that participants discussed included how to appropriately interact with coaches, athletes, athletic training students, and members of the opposite sex. Participants did not want their GAs to interact socially with athletic training students or student–athletes or to abuse athletic training students. Ann stated, “Learning how to draw that professional line is challenging sometimes.” A few participants had fired GAs because of professional misconduct, lying, cheating, or forming inappropriate relationships with student–athletes. Greg said, “I tell [the GAs] there is only 1 thing to worry about: the moment I stop trusting you, I fire you. A young lady, I brought her in and said ‘I am sorry you lied to me. I told you that can't happen; now I can't trust you. Give me my keys back.'” Bob also recalled firing a GA for professional misconduct: “One we had to let go because of the 2 DUIs [driving while intoxicated]. Yes… [the GA] had to go.”

Unrealistic Expectations

Although participants had many role expectations for their GAs, some believed the expectations of GAs were unrealistic. Unrealistic expectations included expecting the GAs to operate at the level of an experienced, full-time, staff member. Wayne described,

In many GA settings, the institution is not taking responsibility to fulfill [its] end of it. [The institution's] goal is to get free help, or cheaper help, rather than hiring full-time assistants. It is not acceptable to have a GA come in and spend 45 to 50 hours a week in clinical coverage for sports and then go study. Those are things that are traditional in that setting because they all know what we had to do in the past. Just because we have done it in the past does not mean that it is right.

Tobias expressed some of the same thoughts on unrealistic expectations:

The problem isn't with GA preparation—the problem is with the system. People have unrealistic expectations of what a GA should be. What they really need is a full-time employee. So, their expectation is that the GA will function as a full-time, experienced employee. So you are hiring the wrong thing.

When asked if GAs were prepared to be autonomous practitioners, as many supervisors expected, Tobias responded,

The complaint that comes from my colleagues is that these kids can't operate by themselves totally independently. My answer to them is, that is 100% right and neither can a brand-new doctor, brand-new nurse, brand-new dentist, or anybody else. They [other professions] do a residency, fellowship; they are supervised into professional practice. A GA at a college or university should always be supervised at first and mentored. So, for you to expect them to be able to, you need to be supervising them. If you want someone you don't have to supervise medically, then you need to hire someone who already has experience. You need to hire a full-time staff person. That is your responsibility as an employer.

Some supervisors' expectations conflicted with Tobias' because many supervisors needed the GAs to act independently. Gary received pressure from the educational director of a nonathletic training graduate program, who expected the GAs to function as full-time staff members:

It was a full-time job on a very small amount of money. You are expected to have responsibilities and do them right. They are expected to put in a certain amount of time. The education director told me they work until the job gets done. “It has always been that way and will always be that way. Work them until they drop, then work them some more.” OK. So we rode them hard and put them away wet every year.

Wayne has seen this type of system at many institutions. He noted,

A lot of institutions' GAs have the wrong term. They should not be called GAs. They are actually doing a serfdom. That system needs to stop...What I thought was unfair when I was a graduate student, I went through the initiation-type experience. I didn't think it enhanced my abilities, and I said it then if I could do it differently, I would.

Although some participants believed that unrealistic expectations were placed on GAs, many continued to have high expectations of GAs. One commented, “As a full-time staff member, you have enough to do, and you want to spend the least amount of time as possible.” Many supervisors had their own teams to worry about, and they lacked the time or resources to mentor or micromanage the GAs. A few supervisors said that GAs should be prepared to work completely independently with no mentoring. Gary explained,

Give them a chance to make all of the decision with some kind of mentorship, but at the undergraduate [professional] level. Don't do it at the GA level because, by that point, all of these people, like myself, are expecting them to just do it. I'm guessing most anyone who hires a GA would be in the same position. The GAs are here to pick up the workload, and we don't want to spend a lot of time watching over them. If we are going to spend this time watching over them, we might as well just do it ourselves.

Some unrealistic expectations placed on GAs were due to external pressure (eg, athletic department, educational department) or busy schedules. Despite unrealistic expectations of GAs, many supervisors understood the GAs were new clinicians and expected them to operate as new clinicians, whereas others had higher expectations of GAs to act as experienced, full-time clinicians.

Success

The fourth and final theme refers to the success of the individual to function in his or her role as a GA and can be further classified into 2 subcategories: (1) adaptability and (2) selection.

Adaptability

Adaptability refers to the GA's ability to adapt to the setting and the specific policies, procedures, and responsibilities of a GA. Many participants reported that the success of the GA was highly dependent on his or her adaptability. Maggie stated, “It has a lot to do with their ability to adapt to new situations, their time management, and communication.” Stan expressed, “Those who were more independent and wanted to take it and run with it adapted faster and were more successful.” Michael had similar reflections:

Those who want to be in that setting will adapt and do well. Those who take initiative are more likely to be successful…[those who go] above and beyond. Confidence, a belief about being included in the decision-making process, and ownership in the job enable the GA to adapt and be successful.

Many participants described adaptability as dependent on the person; GAs who are confident, who are able to make independent decisions, and who have strong work ethics, common sense, and communication skills will adapt faster and be more successful. Lionel commented, “GAs who are not confident and [are] unable to adapt have more trouble clinically because people won't trust them, and they don't further develop their skills.”

Selection

Participants reported that success also depended on their selection of GAs and picking the GAs that were the right fit for their institutions. Wayne said, “They are good people. That is why I picked them. I actively recruited, interviewed, and picked these people. It is no accident that they are going to be successful.” Tobias shared similar thoughts on the importance of selecting the right GAs: “It is much easier to put a good deal of work into finding the really good ones than it is trying to fix or mentor the ones that aren't really good once they get here.” Michael concurred, noting, “That is where the interview is critical. There has to be some kind of mojo from me and that person.” Kitty selected GAs with the intangible qualities (eg, hard working, motivated, and maturity) that cannot be taught and has found those GAs are more successful.

DISCUSSION

The aim of our investigation was to explore the professional socialization of GAs in the collegiate setting to determine how GAs are socialized and developed as ATs. We examined 3 research questions: (1) What processes are used to socialize GAs into the collegiate setting? (2) What are the expectations of GAs in the collegiate setting? (3) What is the supervisor's role in developing the GA? Our results provide a deeper understanding of the supervisors' expectations of GAs and of how GAs are socialized into their roles. Supervisors expected GAs to perform independent patient care at the level of a new health care provider, to make decisions, and to maintain professional relationships. GAs were socialized into their roles with orientation, professional development, and mentoring.

Role Orientation

The GAs were oriented to their roles both formally and informally. Orientation is vital to the success of new medical professionals because it directly relates to productivity and high-quality patient care.15 Effective orientation increases confidence, critical thinking skills, and retention.15 Our participants provided the GAs with written policies, procedures, and protocols in addition to reviewing those items in a formal-orientation setting. Prior researchers examining the socialization of ATs in the collegiate1 and high school settings11 found they were not being formally oriented into their roles. Collegiate ATs reported that job responsibilities (eg, job description) were described in writing, but aside from administrative duties (eg, referral process or vehicle requests), responsibilities were not discussed formally.1 Those ATs commented that some stress and uncertainty might have been alleviated if they had experienced a formal orientation. Although not specifically discussed, the participants in our study who used both formal and informal orientation methods had fewer examples of GA problems that had to be remedied. This suggests that implementing formal orientation activities can alleviate some stress during the socialization process by outlining expectations and procedures.

Many GAs were informally oriented to their roles in the collegiate setting through immediate role immersion or shadowing their mentors. Many supervisors reported that the GAs were needed for patient care and were expected to work immediately upon campus arrival; therefore, those GAs did not have a transition period. This is consistent with other ATs working at the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division-I level, in which new ATs were expected to perform their roles competently at the very beginning.1 However, the ATs working in Division I already had at least 2 years of experience as GAs, whereas most GAs are in their first professional position after certification. High school ATs described their orientation as highly informal, and they learned through trial and error and through observing coaches and the athletic director.11 Our data often showed that the GAs learned their role through trial and error, consistent with previous findings.1,11

A number of supervisors felt that immediate role immersion was the only way the GAs would truly learn their roles. Some of our participants used this “thrown-in-the-fire” method as a way to orient the GAs into their roles, because many believed the GAs would not know how to do the job unless they actually experienced doing it; however, supervisors were always there to provide a safety net for the GAs. Graduate assistants who were interviewed about the essential elements of their postprofessional programs were oriented to their roles via immediate role immersion.16 Although that might make for a difficult transition, the GAs felt that immediate role immersion helped with clinical decision making and mastery of tasks because they were just “thrown into the fire.” The GAs were able to make decisions on their own while still having a safety net. Both GAs in postprofessional athletic training programs16 and new nurses17 were expected to “hit the ground running,” but some nurses concluded that was an unrealistic expectation to place on new graduates.17 Although nursing supervisors acknowledged that was a high expectation, they felt it was necessary because they were often understaffed and did not have time for gradual transitions. Many participants reported needing GAs to immediately provide patient care; therefore, like nurses, many GAs did not experience gradual transitions into their roles.

Having a limited orientation process with immediate role immersion might not be the most effective way to orient new clinicians to their positions. Our findings indicate that some task-specific training, such as how to order diagnostic imaging or to make referrals, may be overlooked with primarily informal orientation processes. Research18 with physicians and nurses has shown the pitfalls of a limited-orientation process, including anxiety and low levels of job satisfaction, confidence, patient satisfaction, and of patient care. The orientation process for new medical professionals is very important because orientation directly affects patient care.15 Merely reviewing policy and procedures or immediately immersing clinicians into practice may not be enough to promote critical thinking and positively affect patient care. High turnover, low levels of job satisfaction, and unprepared nurses prompted Bumgarner et al15 to develop a patient-centered approach to nurse orientation that included both formal and informal methods. The formal orientation covered organizational structure and policies and procedures, whereas the informal orientation consisted of preceptors directly observing patient care, reviewing documentation and patient outcomes, and providing feedback for improvement. With this combination of formal orientation and informal, individualized orientation, new nurses improved in confidence and patient care.

Based on the information provided by our participants, we recommend orientation that consists of both formal and informal methods. During the formal orientation, once GAs arrive at the institution, we suggest supervisors provide information about the organizational structure of the university, discuss AT service policies and procedures, and demonstrate certain administrative tasks (eg, ordering magnetic resonance imaging, patient referrals). During the informal orientation, we recommend more one-on-one interaction so the supervisor can provide the GA with feedback for improvement. If the institution chooses to use immediate role immersion, the supervisor should observe the GA's patient care, review documentation, and evaluate the GA to determine his or her readiness to practice independently. If the GA is not fully prepared for independent practice, the supervisor can supply additional mentoring to better prepare the GA to provide care. The supervisor can then determine whether the new AT has the basic level of competency to work safely without supervision. Researchers could further examine which methods of formal and informal orientation the new employees in various settings felt helped them adapt to their setting and role.

Development and Support

Supervisors provided development and support for the GAs in the form of professional development, formal and informal mentoring, and intervening when necessary. Being a GA can be very stressful because the students are adapting to their roles as new, independent clinicians; maintaining a full academic course load; and, often, participating in research.19 Many supervisors realized that the transition from student to independent clinician was a difficult time for GAs; therefore, many supervisors tried to develop and support the GA professionally during the assistantship. Graduate nurse clinicians were able to transfer their learning when they received support and encouragement from their supervisors and tended to have trouble with autonomy and leadership when supervisors did not provide support.20 That was evident in our results as well. Respondents who mentioned how active they were in supporting and mentoring the GAs described fewer instances when the GAs were unsuccessful.

Although supervisors acknowledge that support is needed for the professional development and socialization of GAs, some of our participants were hesitant to provide support because of their unrealistic expectations of GAs or because of their own time constraints. Supervisors reported not having enough time to devote to developing the GAs because they were too busy with their own job requirements. Kania et al21 found that, in 2003, there was an average ratio of 80 athletes to 1 AT, and each AT was responsible for an average of 3.24 sports. Based on current calculations of the number of collegiate athletes (453 347) and the number of ATs working in the collegiate setting (6963), the ratio now appears to be 1 AT for 65 student–athletes.22,23 Therefore, ATs are still busy in addition to their supervising or mentoring responsibilities. The “Appropriate Medical Coverage of Intercollegiate Athletics” guidelines24 are often used to determine how many ATs are needed to safely provide patient care in the collegiate setting; however, those guidelines do not account for supervising and mentoring GAs or serving as preceptors. Thus, when determining how many ATs are needed for patient care, other duties (such as supervising GAs) are often not considered, and supervisors are often too busy to help GAs develop or to provide mentoring. In a previous study,25 preceptors were interviewed to determine the prevalence of mentoring they provided in undergraduate professional programs. Although mentoring did occur, Panseri25 found that some of the biggest barriers to ATs providing mentorship and support to athletic training students were time constraints and being overworked, underpaid, and understaffed. If the staff members responsible for supervising GAs are too busy with their job responsibilities, they cannot adequately support GAs and help them develop. One way to emphasize the importance of this professional development and mentorship is to include supervision of GAs in the job description and to evaluate all full-time staff members who supervise GAs. Supervisors could then be evaluated for this responsibility during their annual performance reviews and be rewarded for helping new professionals develop.

Despite being busy, many supervisors reported using various professional development techniques, such as formal and informal mentoring. Prior investigators11,26,27 showed that mentorships were important for the growth and development of athletic training students and new ATs. Mentorships are useful for new ATs as they learn and adapt to their roles. In nursing, mentors also increased the value of the mentoring process by assisting the protégés in planning experiences to provide exposure to enhance learning.28 Our participants helped the GAs through scheduling development or patient care opportunities based on the needs of the GAs. This mentoring would help make the GAs more marketable and enhance their professional development.

Not only is the mentorship process positive for the protégé, but it also provides benefits to the mentor. Mentors benefit from their role because the relationship allows them to keep current with research and new techniques.29 Mentors gain personal satisfaction and a renewed sense of purpose; the relationships may prevent burnout, and mentors can be proud of their role in helping the next generation to develop. Other potential benefits are to the institution, such as enhanced productivity, improved morale, recruitment advantages, and the improved skills of the protégé.

For mentorships to be successful, the GAs needed to be willing to learn, to ask questions, and to make supervisors aware of any problems. Protégé responsibilities include being open to feedback and willing to learn and taking initiative.27,28 Pitney and Ehlers27 found that undergraduate athletic training students must take the initiative to develop and sustain mentorships. Some of our participants reported ceasing formal mentorships because the GAs acted as if they were too busy or did not want to learn from the supervisors. Accessibility and approachability are important traits for mentors to have. Many participants in our study reported having open-door policies and forming relationships with their GAs, which fostered mentorships. Participants felt that GAs adapted to their roles better with increased mentorship and support. Emotional support was also provided to GAs through mentorships, which helped the GAs deal with the stress of being new clinicians and students. The benefits of mentoring relationships depend on the amount of time invested by the mentor and the protégé.29 Some protégés do not fully understand the importance of mentoring, which may mean they do not take full advantage of the relationship.30 For mentorships to work, the protégés need to take the initiative and develop these relationships.27

Another important aspect of GA professional development our participants described was intervening and providing feedback on clinical skills and patient care. By actively evaluating a nurse's skills, interpersonal relationships, and documentation abilities, nursing supervisors can intervene as needed to enhance patient care and to help the new nurse develop professionally.28 Some supervisors intervened with GAs and provided constructive feedback to improve their patient care. Supervisors consistently reported that an open line of communication and providing feedback, both positive and negative, were vital to developing the GAs. Therefore, to effectively develop the GAs, supervisors should not only be approachable and accessible, but they should also actively evaluate the GAs, review patient cases, provide feedback, intervene as necessary, and schedule learning opportunities based on the individual needs of the GA.

Role Expectations

Supervisors expected GAs to be competent and independent practitioners, which includes making decisions regarding patient care, communicating, and maintaining professionalism, yet some supervisors may have unrealistic expectations of their GAs. These findings are similar to those reported by Carr and Volberding,31 who interviewed employers and employees regarding the readiness and preparation of new ATs. Interpersonal communication, decision making, and independence are necessary skills, but new ATs are not always able to fulfill those expectations. Although our participants have those same expectations of their GAs, many understood the GAs have not had a great deal of autonomous practice at developing those skills. Our participants stated that GAs had the clinical skills necessary to provide patient care, but they needed practice to further develop their clinical skills. Massie et al32 showed that employers who supervised entry-level employees understand that some skills can only be learned “on the job,” and such employers do not expect athletic training programs to provide students with more than entry-level skills.

The most frequently cited expectation was communication. Athletic training employers place a high value on the ability of a GA to communicate professionally with key stakeholders, such as coaches, physicians, athletes, and other ATs.32 In the Carr and Volberding study31 of athletic training employer and employee's opinions of preparation and readiness for the workforce, interpersonal communication was critical. However, despite the importance of communication, it was the most commonly cited weakness in new AT graduates. Professional programs should provide opportunities that allow athletic training students to gain experience in communicating with coaches' physicians, patients, and other ATs. For some high-stake conversations, such as talking with patients who have eating disorders or with upset coaches, standardized patients or standardized “coaches” can provide those experiences for students in a nonthreatening manner. Many participants reported that GAs were weak in communication because they had never had the experience of communicating with coaches or physicians during their professional preparation, although they did communicate with athletes and ATs.

Many of our participants had specific expectations for the GAs regarding their duties and professional conduct. For GAs to be successful, those expectations need to be clearly outlined during orientation. Many “millennial” GAs need clear, tangible expectations to be successful. Research on millennial students has indicated that this generation expects a “how-to” guide to be successful.33 A quality orientation can also contribute to success by outlining rules, regulations, and procedures. Millennial students need constant feedback if they are to fulfill expectations.33 Supervisors must be very clear with their expectations and provide feedback and direction.

Unrealistic Expectations

Many participants expressed unrealistic expectations. Some participants who expected the GAs to function as experienced, full-time (40+ h/wk) staff felt that was the “initiation process” into athletic training; others felt those expectations still exist because it “has always been that way.” Many supervisors viewed GAs as a “workforce” and a way to assist the often overworked full-time staff. These unrealistic expectations are unfortunate because they may hinder the professional development of GAs. One participant who went through this “initiation process” knew it was not the best approach to his learning and professional development. Romyn et al17 reported new nursing graduates were being used to provide a “much needed body,” which may not foster the successful socialization of new nurses into their roles and may ultimately compromise patient care. Our findings indicate that many GAs work as much as 40 to 60 h/wk and are merely “picking up the slack,” without having opportunities to develop. A systematic review34 examining the effect of clinical supervision on the patient and educational outcomes of entry-level physicians in residency programs demonstrated that inadequate supervision led to medical errors and misdiagnoses. In addition, supervision resulted in both positive patient outcomes and positive educational outcomes for the entry-level physicians. Physicians who were not being supervised committed more medical errors than those who were supervised did. This could also be happening with new ATs because our participants commented that many GAs have no experience providing independent patient care. New GAs should be properly supervised to ensure they are providing optimal patient care.

Success

The biggest reported contributions to GA success were the selection of GAs and their personal characteristics, such as the ability to adapt. Success, or the GAs' ability to fulfill their roles, depended on the supervisor's selection of the GAs best fit for the institution and the GAs' ability to adapt to their roles.

Participants who properly vetted the GAs for their programs had greater success with the GAs. A few supervisors who did not invest as much time in selecting their GAs stated the GA either took longer to adapt to the role or was relieved of duty. Some participants recruited through word of mouth and personal recommendations, rather than advertising positions, because they felt that enabled them to select the right GAs for their programs. In addition, some participants selected GAs based on their intangible personal characteristics (eg, work ethic, maturity, confidence, motivation) that could not be taught. In a survey of AT employers' hiring criteria, Kahanov and Andrews35 found that personal characteristics, such as maturity, assertiveness, enthusiasm, initiative, ambition, and oral communication skills, were the most important. Carr and Volberding31 interviewed employers and ATs to determine the level of preparation in new ATs and identified confidence, humility, the ability to learn from mistakes, and the willingness to take initiative as important characteristics in new ATs. Future GAs should be advised that personal characteristics are very important to supervisors and to their success as GAs. Kahanov and Andrews35 suggested that discussing the important hiring criteria during professional education may help athletic training students when they apply for jobs and graduate assistantships.

In addition to GA selection criteria, supervisors felt GAs were more successful when they adapted to the policies and procedures at their specific institution. The ability of GAs to adapt to their institutions parallels Pitney et al's1 description of the final stage of socialization: gaining stability within the organization. Gaining stability occurred when the AT's values were in line with the institution's, when the AT felt supported, and when he or she was able to autonomously use the skills learned. Similar to Pitney et al,1 our results showed that when GAs were unable to adapt to their role, they were often dismissed from the role or made the decision to leave; role instability often caused the AT to leave the institution and take another position.

Limitations

One limitation of this study is that our results were not longitudinal. We were exploring only the participants' reflections on socialization and were not examining the socialization process. We also explored only the supervisors' views, and it is unclear how the GAs perceive their socialization into their roles in the collegiate setting. Another limitation is the generalizability of this study. Because we interviewed only supervisors of GAs in the collegiate setting, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings.

Future Research

The results from our study add to the literature and describe the socialization process of GAs in the collegiate setting. Although we examined the perceptions of the supervisors, future investigators should examine the GAs' perceptions of their socialization to learn which aspects they feel help them adapt to their new roles. Researchers could explore the learning and professional development needs of the GAs as they are socialized into their roles. Researchers can also assess the best practices for mentoring and developing the GAs by determining which mentoring practices are the most beneficial and which could be improved. Addressing how socialization for GAs in postprofessional and residency programs differs from the socialization of GAs in programs that are not postprofessional would also be useful.

CONCLUSIONS

Transitioning from being a student to being a GA is a challenging but important part of professional development. Supervisors have many expectations of GAs, some of which may be unrealistic. To facilitate a better transition to practice for ATs during their time as GAs, supervisors must recognize the needs of the GAs and focus on their professional and educational development. Supervisors should help the GA develop professionally through mentoring and intervention, as needed, and strive to create meaningful learning experiences that will facilitate autonomous practice. Most supervisors care about the GAs and their professional development. However, the unrealistic expectations of GAs to function as full-time staff members needs to change, given the transitional nature of the GA role. Supervisors should view their work with GAs as an opportunity to mentor and guide young ATs as they enter the professional phase of their careers instead of an opportunity to hire an AT at a reduced cost.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Great Lakes Athletic Trainers' Association through the Robert Behnke Research Assistance Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pitney WA, Ilsley PP, Rintala JJ. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I context. J Athl Train. 2002;37(1):63–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown J, Stevens J, Kermode S. Supporting student nurse professionalisation: the role of the clinical teacher. Nurse Educ Today. 2011;32(5):606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Athletic Trainers Association. Future Directions in Athletic Training Education. Dallas, TX: National Athletic Trainers' Association;; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klossner J. The role of legitimation in the professional socialization of second-year undergraduate athletic training students. J Athl Train. 2008;43(4):379–385. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty-Restrepo J. Education literature: current literature summary. Athl Train Educ J. 2012;7(2):83–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pitney WA. Organizational influences and quality-of-life issues during the professional socialization of certified athletic trainers working in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2006;41(2):189–195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitus JS. Organizational socialization from a content perspective and its effect on the affective commitment of newly hired rehabilitation counselors. J Rehabil. 2006;72(2):12–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winterstein AP. Organizational commitment among head athletic trainers: examining our work environment. J Athl Train. 1998;33(1):54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charmaz K. Grounded theory methods in social justice research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 2011. pp. 359–380. In. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitney WA. The professional socialization of certified athletic trainers in high school settings: a grounded theory investigation. J Athl Train. 2002;37(3):286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mensch J, Crews C, Mitchell M. Competing perspectives during organizational socialization on the role of certified athletic trainers in high school settings. J Athl Train. 2005;40(3):333–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill CE, Thompson BJ. Nutt Williams E. A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns Psychol. 1997;25(4):517–571. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer TN, Bodner T, Erdogan B, Truxillo DM, Tucker JS. Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: a meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(3):707–721. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bumgarner SD, Biggerstaff GH. A patient-centered approach to nurse orientation. J Nurse Staff Dev. 2000;16(6):249–256. doi: 10.1097/00124645-200011000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neibert PJ. Novice to expert practice via postprofessional athletic training education: a grounded theory. J Athl Train. 2009;44(4):378–390. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.4.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romyn DM, Linton N, Giblin C, et al. Successful transition of the new graduate nurse. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2009;6(1):1–17. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boswell S, Lowry LW, Wilhoit K. New nurses' perceptions of nursing practice and quality patient care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;19(1):76–81. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200401000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed S, Giacobbi PR. The stress and coping responses of certified graduate athletic training students. J Athl Train. 2004;39(2):193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Currie K, Tolson D, Booth J. Helping or hindering: the role of nurse managers in the transfer of practice development learning. J Nurs Manag. 2007;15(6):585–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kania ML, Meyer BB, Ebersole KT. Personal and environmental characteristics predicting burnout among certified athletic trainers at National Collegiate Athletic Association institutions. J Athl Train. 2009;44(1):58–66. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-44.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2011 year-end membership statistics. 2013 http://members.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/2011EOY-stats.htm. Accessed May 29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irick E. 1981–1982 – 2011–12 NCAA Sports Sponsorship and Participation Rates Report. Indianapolis, IN: National Collegiate Athletic Association;; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Recommendations and guidelines for appropriate medical coverage of intercollegiate athletics. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. 2013 http://www.nata.org/appropriate-medical-coverage-intercollegiate-athletics. Accessed May 29. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panseri ML. An Exploration of Mentoring in Athletic Training Clinical Education: Establishing a Preliminary Model Based on the Grounded Theory [master's thesis] Morgantown, WV: University of West Virginia;; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan D, Mentorship Brewer K. and professional role development in undergraduate nursing education. Nurs Educ. 1997;22(6):20–24. doi: 10.1097/00006223-199711000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitney WA, Ehlers GG. A grounded theory study of the mentoring process involved with undergraduate athletic training students. J Athl Train. 2004;39(4):344–351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greene MT, Puetzer M. The value of mentoring: a strategic approach to retention and recruitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2002;17(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coates WC. Being a mentor: what's in it for me? Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark RA, Harden SL. Mentor relationships in clinical psychology doctoral training: results of a national survey. Teach Psychol. 2000;27(4):262–268. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr WD, Volberding J. Employer and employee opinions of thematic deficiencies in new athletic training graduates. Athl Train Educ J. 2012;7(2):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massie JB, Strang AJ, Ward RM. Employer perceptions of the academic preparation of entry-level certified athletic trainers. Athl Train Educ J. 2009;4(2):70–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monoco M, Martin M. The millennial student: a new generation of learners. Athl Train Educ J. 2007;2(1):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farnan JM, Petty LA, Georgitis E, et al. A systematic review: the effect of clinical supervision on patient and residency education outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):428–442. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824822cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kahanov L, Andrews L. A survey of athletic training employers' hiring criteria. J Athl Train. 2001;36(4):408–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]