Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite improvement in motor function after intervention, adults with chronic stroke experience disability in everyday activity. Factors other than motor function may influence affected upper limb (UL) activity.

OBJECTIVE

To characterize affected UL activity and examine potential modifying factors of affected UL activity in community-dwelling adults with chronic stroke.

METHODS

Forty-six adults with chronic stroke wore accelerometers on both ULs for 25 hours and provided information about potential modifying factors (time spent in sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, motor dysfunction of the affected UL, age, activities of daily living (ADL) status, and living arrangement). Accelerometry was used to quantify duration of affected and unaffected UL activity. The ratio of affected-to-unaffected UL activity was also calculated. Associations within and between accelerometry-derived variables and potential modifying factors were examined.

RESULTS

Mean hours of affected and unaffected UL activity were 5.0 ± 2.2 and 7.6 ± 2.1 hours, respectively. The ratio of affected-to-unaffected UL activity was 0.64 ± 0.19, and hours of affected and unaffected UL activity were strongly correlated (r=0.78). Increased severity of motor dysfunction and dependence in ADLs were associated with decreased affected UL activity. No other factors were associated with affected UL activity.

CONCLUSIONS

Severity of motor dysfunction and ADL status should be taken into consideration when setting goals for UL activity in people with chronic stroke. Given the strong, positive correlation between affected and unaffected UL activity, encouragement to increase activity of the unaffected UL may increase affected UL activity.

Keywords: accelerometry, arm, body-worn sensors, function, rehabilitation, stroke, upper limb

INTRODUCTION

Despite participation in rehabilitation regimens, paresis of the affected upper limb (UL) after stroke results in impaired motor function (e.g. coordination, strength) that persists for more than six months in a majority of people.1 The focus of many physical rehabilitation approaches, such as constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT),2 task-specific training,3 and robot-assisted training, 4 is to improve motor function of the affected UL because early recovery of UL function is a strong predictor for later recovery.5 Even with improvements in motor function following intervention, adults with chronic stroke continue to experience disability in everyday activity,6 which indicates that additional factors influence real-world use of the affected UL. If these additional factors can be identified, they can be targeted as part of treatment intervention to further increase affected UL activity.

Many factors, including sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depression, multiple comorbidities, and age, are associated with reduced levels of physical activity and increased levels of disability in nondisabled adults7–11 and adults with stroke,12–16 and could potentially modify affected UL activity. We recently examined the relationship between these potential modifying factors and UL activity in nondisabled adults, and demonstrated that only the amount of time spent in sedentary activity was associated with activity of both ULs.17 It is important to know if similar relationships exist in adults with chronic stroke.

Additional factors related to stroke, including dependence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL),18 whether the dominant UL was affected by stroke,19 and severity of motor dysfunction,20 are associated with affected UL motor function as measured by clinical tests, and might also influence affected UL activity in adults with chronic stroke. Furthermore, living with others compared to living alone is associated with better perceived general health,21 and could influence UL activity. The association between these factors and affected UL activity in chronic stroke has not yet been explored.

It is also important to distinguish real-world activity (i.e. activity that occurs in an individual’s home, work, and community settings) from rehabilitation-related activity that occurs inside hospital or clinical settings. In clinical settings, rehabilitation approaches that target the affected UL (e.g. CIMT and robot-assisted training) often require the affected UL to be used in a way that the limb is not typically used outside of the clinic. This is done because it is expected that gains made in therapy will translate into increased use of the affected UL in real-world settings. To ascertain if this translation truly occurs, affected UL activity needs to be measured in both real-world and clinical settings.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to characterize real-world affected UL activity, and potential modifying factors of affected UL activity, in community-dwelling adults with chronic stroke. We hypothesized that increased time spent in sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, age, and severity of motor dysfunction would be associated with decreased real-world affected UL activity. We also hypothesized that real-world affected UL activity would be greater in participants who lived alone, and who were independent in ADLs.

METHODS

Participants

Data from forty-six adults with chronic stroke were examined in this study. Participants were enrolled in a randomized control trial (NCT 01146379) between April 2011 and December 2013. The randomized control trial examines the dose-response effect of task-specific training on UL function in adults with mild-to-moderate chronic stroke. Only baseline (i.e. pretreatment) data were analyzed for this study. Participants were recruited from the Cognitive Rehabilitation Research Group and the Brain Recovery Core databases at Washington University School of Medicine. These databases contain contact information for patients with stroke admitted to Barnes Jewish Hospital or The Rehabilitation Institute of St. Louis in St. Louis, Missouri, USA, who consented to being contacted for potential participation in future research studies. Participants were also recruited from the community via word of mouth and flyers. All participants provided informed consent for participation in the randomized control trial, which was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University in St. Louis.

Inclusion criteria at time of consent included 1) ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke as determined by a stroke neurologist, 2) cognitive skills sufficient to participate, determined by a score of 0–1 on items 1b and 1c of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS),22 3) mild to moderate unilateral UL weakness, defined by a score of 1–3 on item 5 of the NIHSS, 4) ability to actively move the affected UL, determined by an Action Research Arm Test (ARAT, see Measures section of Methods for description) score of 10–49,23 and 5) ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included 1) inability to follow commands, 2) psychiatric diagnosis, 3) current participation in stroke treatment (e.g. therapy, botox), 4) other neurological diagnosis, and 5) pregnancy.

Procedure

Participants completed a one-hour office visit at the Neurorehabilitation Lab at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, where they provided demographic and medical information. Accelerometers were used to record duration of UL activity, and were placed on both wrists, proximal to the ulnar styloid, at the beginning of the office visit. Participants completed a battery of study assessments that measured potential modifying factors of affected UL activity. Participants were then instructed to wear the accelerometers for the subsequent 24 hours while they went about their normal daily routines, with permission to remove the devices when bathing or showering. Participants returned the accelerometers on a subsequent visit, at which time accelerometry data were visually inspected to ensure that patients wore the accelerometers during the designated wearing period.

Measures

Accelerometry-Derived Variables that Quantify UL Activity

Real-world activity of the ULs was captured using accelerometers. The GT3X Activity Monitor (Actigraph; Pensacola, Florida) measures acceleration in three axes with a dynamic range of ± 6 gravitational units. Data is stored on an on-board microchip that can be downloaded at a later time. Due to its small (38 × 37 × 18 mm) size and portability, the GT3X Activity Monitor is ideal for measuring activity that occurs in real-world settings. Use of accelerometry to measure real-world UL activity in people with stroke has established validity and reliability.24–26

Acceleration was sampled in all three axes at 30Hz. Raw acceleration was integrated into 1 second samples, and converted into activity counts (0.01664g/count) using ActiLife 6 software (ActiGraph; Pensacola, FL). Data were then processed using MATLAB R2011b (Mathworks; Natick, MA). A custom-written program combined activity counts from all three axes into a single value, called the vector magnitude, using the following equation: √(x2 +y2 + z2). Vector magnitudes were calculated for each second of activity. Vector magnitude values were then dichotomized into two categories using a filter threshold.17,27 Seconds when the vector magnitude was ≥2 were defined as “activity,” and seconds when the vector magnitude was <2 were defined as “no activity.” Seconds of activity were summed to determine hours of affected and unaffected UL activity. The activity ratio was calculated by dividing hours of affected UL activity by hours of unaffected UL activity.17,27

Two accelerometry-derived variables quantify real-world affected UL activity: hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio. Hours of affected UL activity directly reflects duration of real-world affected UL activity. The activity ratio, which is also referred to in the literature as the “ratio of more- to-less-impaired arm acceleration,”24 reflects affected UL activity with respect to unaffected UL activity. Importantly, the activity ratio is stable (mean ± SD = 0.95 ± 0.06) and independent of hours of UL activity in nondisabled adults (r = 0.08).17

Potential Modifiers of UL Activity

Factors hypothesized to modify affected UL activity included time spent in sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, severity of stroke-induced motor dysfunction, age, ADL status, and living arrangement (see Introduction).

Time spent in sedentary activity during a typical weekday, quantified in hours, was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale, a valid self-report measure of daily physical activity.28,29 Sedentary activity was defined as activity of 1.4 METS (Metabolic Equivalent of Task30) or less, and includes activities such as sleeping, reading, and watching television.

Cognitive impairment was quantified using the Short Blessed Test, a cognitive screening test used to assess memory, orientation, and concentration.31 This tool has been used to assess cognitive impairment in adults with stroke.13,32,33 Errors on six questions are weighted (total score = 28), with higher scores indicating more-impaired cognition. Scores ≥6 indicate probable cognitive impairment.34

Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, a screening test for depression and depressive disorder35 that has been validated for use in adults with stroke.36,37 Twenty questions are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (total score = 60), with higher scores indicating increased depressive symptomatology. Scores ≥ 16 indicate probable clinical depression.35,38

Number of comorbidities was obtained using a checklist of common medical conditions. Self-reported recall of health conditions is more accurate with checklists than with open- or free-response methods.39,40

Severity of stroke-induced motor dysfunction was assessed using the ARAT, a performance-based assessment with established reliability that quantifies the capacity to reach, grasp, move/manipulate, and release objects (total score = 57).41–43 Higher scores indicate less motor dysfunction.

Age was obtained from the recruitment databases. ADL status (i.e. independent versus dependent for bathing, grooming, or dressing) and living arrangement (i.e. lives with others versus alone) were collected via self-report.

Additional self-reported demographic and health characteristics (i.e. education, employment, hand dominance, side affected by stroke, time since most-recent stroke, number of strokes) were collected according to routine clinical practice, and where appropriate, examined to see if they influenced potential modifiers of affected UL activity (i.e. moderating effects were examined).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All data were checked for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests and variance was assessed using Levene’s test.44 Means and standard deviations were calculated for normally-distributed variables, and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for non-normally-distributed variables. Correlation analyses (Pearson, Spearman, and biserial44) were used to examine associations among and between hours of affected UL activity, hours of unaffected UL activity, the activity ratio, and potential modifiers of affected UL activity. Correlation coefficients <0.30 were weak, between 0.30 and 0.60 were moderate, and ≥0.60 were considered strong.45 Independent t-tests were used to examine differences in hours of affected and unaffected UL activity; and to examine differences in hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio based on ADL status, living arrangement, and whether the dominant versus the nondominant UL was affected. All significance tests were two-tailed and criteria for significance was set at alpha = 0.05.

RESULTS

Forty-six subjects participated in this study. Mean age was 60 ± 11 years. Sex (male: n=30/46), race (African American: n=24/46; Caucasian: n=22/46), and side affected by stroke (dominant: n=24/46) were well-represented across participants. The median time since most-recent stroke was 0.9 (IQR = 1.4) years, and the median number of strokes was 1 (IQR = 1). Participants wore the accelerometers for the designated wearing period (median: 24.9 hours, IQR: 1.55 hours). No technical problems with the accelerometers were observed.

Descriptive statistics of potential modifiers of affected UL activity are provided in the Table. Participants spent 66% (15.8/24 hours) of their time during a typical weekday in sedentary activity. Scores for self-reported cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, and age exhibited a broad range of values. All participants experienced motor dysfunction of the affected UL, as indicated by Action Research Arm Test scores. A majority of participants were independent in ADLs and lived with others. The dominant UL was affected in approximately half of study participants.

Table.

Descriptive statistics of, and correlations between, potential modifiers, hours of affected UL activity, and the activity ratio (n=46, except as noted†)

| Potential Modifiers | Mean ± SD or Median (IQR) | Range | Correlations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Hours of Affected UL Activity | Activity Ratio | |||

| Hours of Sedentary Activity† | 15.8 ± 4.0 | 6 – 23 | 0.00 | 0.27 |

| Cognitive Impairment† | 2 (7) | 0 – 28 | −0.09 | 0.17 |

| Depressive Symptomatology | 9 (17) | 0 – 52 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Number of Comorbidities | 3 (2) | 0 – 7 | −0.02 | −0.08 |

| Motor Dysfunction of Affected UL | 36 (15) | 10 – 48 | 0.49* | 0.63* |

| Age | 60 ± 11

|

32 – 83 | 0.00 | −0.02 |

|

N (%)

|

||||

| ADL Status (independent) | 37 (80) | |||

| Living Arrangement (lives with others) | 34 (74) | |||

| Dominant UL Affected | 24 (52) | |||

Assessment scores were missing for some participants; for Hours of Sedentary Activity, n = 36; for Cognitive Impairment, n = 45

p < 0.01

Abbreviations: ADL = Activities of Daily Living, UL = Upper Limb

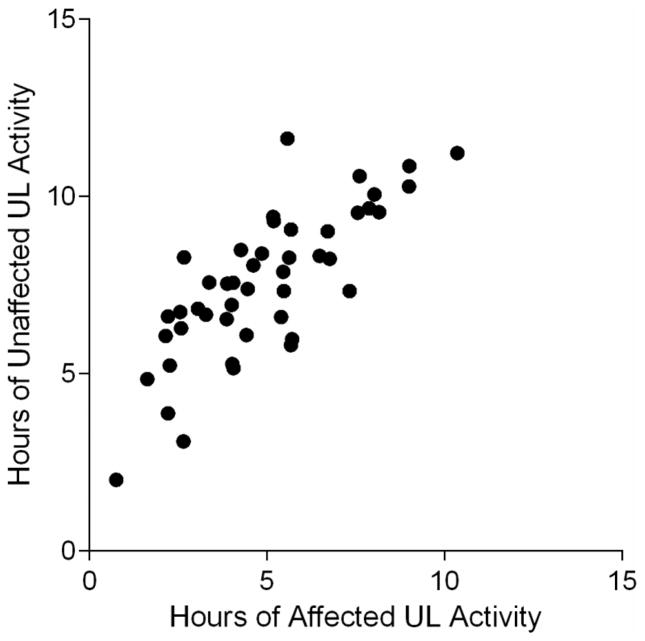

Hours of affected UL activity (5.0 ± 2.2, range: 0.8–10.4) were significantly less than hours of unaffected UL activity (7.6 ± 2.1, range: 2.0–11.6, p < 0.01). Hours of affected UL activity were positively associated with hours of unaffected UL activity (r = 0.78, p < 0.01), as illustrated in Figure 1. The activity ratio was 0.64 ± 0.19 (range: 0.32–1.00).

Figure 1.

Scatterplot of hours of affected versus unaffected UL activity. The correlation between the two variables was strong (r=0.78).

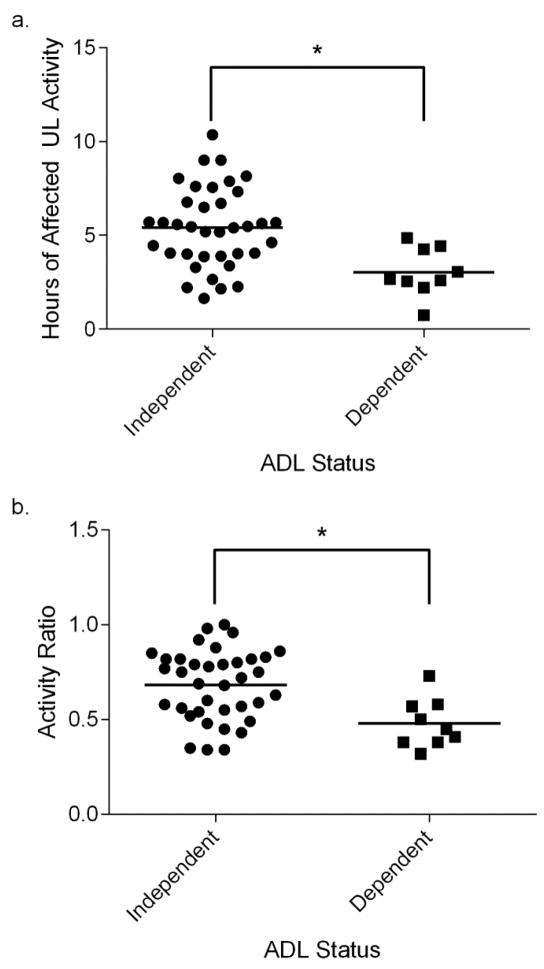

Correlation coefficients between potential modifiers and both hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio are provided in the Table. Severity of motor dysfunction of the affected UL was moderately associated with hours of affected UL activity, and strongly associated with the activity ratio. Correlation coefficients between the remaining potential modifiers listed in the Table and both hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio were weak and lacked significance (for all values, p > 0.12). Affected UL activity was greater in participants who were independent in ADLs (5.4 ± 2.1 hours) than in participants who received assistance for bathing, grooming, or dressing (3.0 ± 1.3 hours, p < 0.01, Figure 2a). The activity ratio also was greater in participants who were independent in ADLs (0.68 ± 0.18) than in participants who received assistance (0.48 ± 0.13, p < 0.01, Figure 2b). For living arrangement, there was no difference between participants who lived alone versus those who lived with others in hours of affected UL activity (mean difference: 0.09 hours, p = 0.9) or the activity ratio (mean difference: 0.02, p = 0.78).

Figure 2.

ADL status versus real-world affected UL activity. Each symbol represents a single subject. Horizontal lines represent mean values. Hours of affected UL activity (a) and the activity ratio (b) were significantly higher in participants who were independent for bathing, grooming, or dressing than in participants who were dependent.

*p < .01

Secondary analyses explored the relationship between additional stroke-related variables and both hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio to see if the additional stroke-related variables influenced the correlations described above (i.e. moderating effects were examined). Time since most-recent stroke and number of strokes were not correlated with either hours of affected UL activity or the activity ratio (for all values, ρ < 0.23, p >0.60). There was no difference in hours of affected UL activity based on whether the dominant UL was affected (mean difference: 0.75 hours, p=0.25). The activity ratio was higher, however, in participants whose dominant UL was affected (0.70 ± 0.18) than in participants whose nondominant UL was affected (0.57 ± 0.18, p = 0.02). Statistical tests investigating the relationship between potential modifiers and the activity ratio were therefore re-examined while controlling for whether the dominant UL was affected using partial correlations; no significant changes in correlation coefficients or t-test statistics were observed. Last of all, the association between ADL status and motor dysfunction of the affected UL was examined because both modifiers were associated with accelerometry-derived variables. The biserial correlation between ADL status and severity of motor dysfunction of the affected UL was not significant (r = −0.32, p = 0.12).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to characterize real-world affected UL activity, and examine potential modifiers of UL activity, in community-dwelling adults with chronic stroke. Hours of affected UL activity were strongly correlated with hours of unaffected UL activity (r = 0.78), even though duration of affected UL activity was 2.6 hours less than unaffected UL activity. That the affected UL was less active than the unaffected UL was confirmed by an activity ratio of 0.64 ± 0.19. The activity ratio was higher in participants whose dominant UL was affected than in participants whose nondominant UL was affected; whether the dominant UL was affected, however, did not confound associations between the activity ratio and potential modifiers of affected UL activity. In accordance with our hypotheses, increased severity of motor dysfunction and dependence in ADLs were associated with decreased hours of affected UL activity and activity ratios. The participants’ time spent in sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, age, and living arrangement were not associated with hours of affected UL activity or the activity ratio.

Our findings confirm that real-world activity of both affected and unaffected ULs is lower in adults with chronic stroke than in adults without stroke, where real-world activity of the dominant and nondominant ULs averages 9.1 and 8.6 hours, respectively.17 Michielsen et al. also found that activity of the ULs in adults with chronic stroke (unaffected UL: 5.3 hours, affected UL: 2.4 hours) was lower than in nondisabled adults (dominant UL: 5.4 hours, nondominant UL: 5.1 hours).46 The authors acknowledge that the inconvenience of wearing their accelerometry-based system (consisting of 5 accelerometers across the thighs, trunk, and ULs) may have resulted in underestimation of real-world UL activity in their sample, which likely explains the difference in hours of affected and unaffected UL activity observed between this study and theirs.

While it is known that activity of both ULs is reduced immediately after stroke,47 it is alarming that unaffected UL activity remains reduced in chronic stroke (7.6 hours compared to 9.1 hours of dominant UL activity in nondisabled adults).17 Even though only one UL is affected at the level of impairment (i.e. hemiparesis), both ULs are affected at the level of activity in everyday life. The strong correlation between hours of affected and unaffected UL activity in our study indicates that decreased affected UL activity is associated with decreased unaffected UL activity. This phenomenon may be explained by the fact that many daily activities are performed bilaterally, and require both ULs to work together (e.g. stacking boxes, stabilizing a piece of paper with one hand while writing with the other hand). 48,49 Hence, reduced affected UL activity might lead to reduced unaffected UL activity. Viewed from the opposite direction, the correlation suggests that affected UL activity might be increased by increasing activity of the unaffected UL because of the bilateral nature of everyday tasks. If such a causal relationship exists, increasing unaffected UL activity in order to increase affected UL activity could be an alternative intervention strategy for patients who do not respond to, or meet entry criteria for, other interventions, such as CIMT or robotic-assisted therapy. Furthermore, it would address the issue of reduced unaffected UL activity in chronic stroke.

Whether the dominant versus nondominant UL is affected should also be considered when addressing real-world affected UL activity. This study demonstrated greater activity ratios in participants whose dominant UL was affected than in participants whose nondominant UL was affected. This finding is consistent with studies that demonstrated less motor impairment,19 and greater recovery after bilateral arm training,50 of the affected UL in chronic stroke patients whose dominant UL was affected. As a whole, these results suggest that people whose nondominant ULs are affected by stroke may need more encouragement to use their affected ULs.

Increased severity of motor dysfunction was associated with decreased hours of affected UL activity and decreased activity ratios. That better motor function and increased real-world affected UL activity are associated is unsurprising, given the positive relationship observed between tests of motor ability (e.g. Fugl-Meyer Assessment) and global function (i.e. Functional Independence Measure).20,51,52 On the other hand, the associations between ADL status, and both hours of affected UL activity and the activity ratio are not as straightforward. While it is reasonable to assume that dependence in ADLs can occur as a result of UL motor dysfunction, it is not the sole contributor to dependence in ADLs. Paresis of the lower limb, poor balance, and cognitive status, among other factors, can also contribute to dependence in ADLs. Interventions other than increasing motor function of the affected UL, such as use of adaptive equipment, might allow a person to be independent in ADLs while indirectly contributing to increased affected UL activity (e.g. use of adaptive equipment could encourage use of both ULs to complete many tasks).

Time spent in sedentary activity, cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, age, and living arrangement were not associated with hours of affected UL activity or the activity ratio. In nondisabled adults, these same factors were not associated with hours of real-world UL activity, with the exception of time spent in sedentary activity, which showed a modest correlation (r = −0.36). 17 In the present study, the parameters used to assess time spent in sedentary activity, hours of affected UL activity, and the activity ratio were sufficiently broad to detect correlations, had they existed. The range of values for cognitive impairment, depressive symptomatology, number of comorbidities, and age were also broad, and would have demonstrated significant correlations with either hours of affected UL activity or the activity ratio, had they existed. Regarding living arrangement, even though previous research indicates that living alone offers protective effects against self-perceived morbidity and poor health status,21 living arrangement was not associated with affected UL activity in study participants. While the factors described above are associated with physical activity12–16 and perceived general health,21 they were not associated with real-world affected UL activity. Goals related to affected UL activity therefore need not be reduced in the presence of these factors.

Because of its observational design, the main limitation of this study is its inability to demonstrate a cause-effect relationship between potential modifying factors and real-world affected UL activity. A longitudinal design would be necessary to demonstrate such a relationship. A second limitation is that accelerometry is a useful index of UL function in daily life, rather than a direct quantification of function itself. As used here, accelerometry cannot distinguish between volitional (i.e. reaching) and non-volitional (i.e. arm-swing during gait) movements. The effect of this on our data would be to possibly inflate the duration of UL activity, but would not likely influence the activity ratio. With advances in technology, this weakness will likely be rectified. Despite this inherent limitation at present, accelerometry is one of the best tools available for objectively measuring UL activity in real-world settings.

CONCLUSIONS

This study characterized real-world affected UL activity in community-dwelling adults with chronic stroke, and examined associations between affected UL activity and numerous factors hypothesized to modify affected UL activity. Increased severity of motor dysfunction and dependence in ADLs were associated with decreased hours of affected UL activity and decreased activity ratios, and should be considered when designing treatment interventions and setting goals to improve real-world affected UL activity in adults with chronic stroke. Because real-world affected and unaffected UL activity were strongly correlated, increasing real-world activity of the unaffected UL could be a potential strategy for increasing affected UL activity in adults with chronic stroke, and deserves further exploration.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This material was based on work supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences (grant UL1 TR00048) from the National Center for Advancing Translation Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Additional NIH support included T32 HD7434-18, TL1 TR000449, and R01 HD068290. Special thanks to Louis Poppler, MD, for providing critical feedback during manuscript preparation.

Contributor Information

Ryan R. Bailey, Program in Physical Therapy, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. St. Louis, MO, USA.

Rebecca L. Birkenmeier, Program in Occupational Therapy, Program in Physical Therapy, Department of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. St. Louis, MO, USA

Catherine E. Lang, Program in Occupational Therapy, Program in Physical Therapy, Department of Neurology. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. St. Louis, MO, USA

References

- 1.Wade DT, Hewer RL. Functional abilities after stroke: measurement, natural history and prognosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Feb. 1987;50(2):177–182. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.50.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf SL, Winstein CJ, Miller JP, et al. Effect of constraint-induced movement therapy on upper extremity function 3 to 9 months after stroke: the EXCITE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2006 Nov 1;296(17):2095–2104. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkenmeier RL, Prager EM, Lang CE. Translating animal doses of task-specific training to people with chronic stroke in 1-hour therapy sessions: a proof-of-concept study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair Sep. 2010;24(7):620–635. doi: 10.1177/1545968310361957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fasoli SE, Krebs HI, Stein J, Frontera WR, Hogan N. Effects of robotic therapy on motor impairment and recovery in chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil Apr. 2003;84(4):477–482. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nijland RH, van Wegen EE, Harmeling-van der Wel BC, Kwakkel G. Presence of finger extension and shoulder abduction within 72 hours after stroke predicts functional recovery: early prediction of functional outcome after stroke: the EPOS cohort study. Stroke Apr. 2010;41(4):745–750. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.572065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonita R, Solomon N, Broad JB. Prevalence of stroke and stroke-related disability. Estimates from the Auckland stroke studies. Stroke. 1997 Oct;28(10):1898–1902. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Martinez JA, Hu FB, Gibney MJ, Kearney J. Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and obesity in the European Union. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999 Nov;23(11):1192–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaffe K, Barnes D, Nevitt M, Lui LY, Covinsky K. A prospective study of physical activity and cognitive decline in elderly women: women who walk. Arch Intern Med. 2001 Jul 23;161(14):1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penninx BW, Leveille S, Ferrucci L, van Eijk JT, Guralnik JM. Exploring the effect of depression on physical disability: longitudinal evidence from the established populations for epidemiologic studies of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1999 Sep;89(9):1346–1352. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fultz NH, Ofstedal MB, Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Additive and interactive effects of comorbid physical and mental conditions on functional health. J Aging Health. 2003 Aug;15(3):465–481. doi: 10.1177/0898264303253502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspersen CJ, Pereira MA, Curran KM. Changes in physical activity patterns in the United States, by sex and cross-sectional age. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000 Sep;32(9):1601–1609. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rand D, Eng JJ, Tang PF, Jeng JS, Hung C. How active are people with stroke?: use of accelerometers to assess physical activity. Stroke. 2009 Jan;40(1):163–168. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.523621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatemichi TK, Desmond DW, Stern Y, Paik M, Sano M, Bagiella E. Cognitive impairment after stroke: frequency, patterns, and relationship to functional abilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994 Feb;57(2):202–207. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002 Aug 1;52(3):253–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karatepe AG, Gunaydin R, Kaya T, Turkmen G. Comorbidity in patients after stroke: impact on functional outcome. J Rehabil Med. 2008 Nov;40(10):831–835. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser A, Kase CS, Scaramucci A, D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA. The influence of gender and age on disability following ischemic stroke: the Framingham study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003 May-Jun;12(3):119–126. doi: 10.1016/S1052-3057(03)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bailey RR, Lang CE. Upper-limb activity in adults: referent values using accelerometry. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(9):1213–1222. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.12.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mercier L, Audet T, Hebert R, Rochette A, Dubois MF. Impact of motor, cognitive, and perceptual disorders on ability to perform activities of daily living after stroke. Stroke. 2001 Nov;32(11):2602–2608. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JE, Eng JJ. Individuals with the dominant hand affected following stroke demonstrate less impairment than those with the nondominant hand affected. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2006 Sep;20(3):380–389. doi: 10.1177/1545968305284528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, Divine GW, Feussner J. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. Outcome assessment and sample size requirements. Stroke. 1992 Aug;23(8):1084–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.8.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joung IM, van de Mheen H, Stronks K, van Poppel FW, Mackenbach JP. Differences in self-reported morbidity by marital status and by living arrangement. Int J Epidemiol. 1994 Feb;23(1):91–97. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institue of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. [Accessed July 17, 2014];Stroke Scales and Related Information. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/stroke/strokescales.htm.

- 23.Yozbatiran N, Der-Yeghiaian L, Cramer SC. A standardized approach to performing the action research arm test. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008 Jan-Feb;22(1):78–90. doi: 10.1177/1545968307305353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uswatte G, Foo WL, Olmstead H, Lopez K, Holand A, Simms LB. Ambulatory monitoring of arm movement using accelerometry: an objective measure of upper-extremity rehabilitation in persons with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005 Jul;86(7):1498–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Pas SC, Verbunt JA, Breukelaar DE, van Woerden R, Seelen HA. Assessment of arm activity using triaxial accelerometry in patients with a stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 Sep;92(9):1437–1442. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang CE, Bland MD, Bailey RR, Schaefer SY, Birkenmeier RL. Assessment of Upper Extremity Impairment, Function, and Activity After Stroke: Foundations for Clinical Decision Making. J Hand Ther. 2012 Sep 10; doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uswatte G, Miltner WH, Foo B, Varma M, Moran S, Taub E. Objective measurement of functional upper-extremity movement using accelerometer recordings transformed with a threshold filter. Stroke. 2000 Mar;31(3):662–667. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.3.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aadahl M, Jorgensen T. Validation of a new self-report instrument for measuring physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 Jul;35(7):1196–1202. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000074446.02192.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen LG, Groenvold M, Jorgensen T, Aadahl M. Construct validity of a revised Physical Activity Scale and testing by cognitive interviewing. Scand J Public Health. 2010 Nov;38(7):707–714. doi: 10.1177/1403494810380099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Aug;43(8):1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983 Jun;140(6):734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards DF, Hahn MG, Baum CM, Perlmutter MS, Sheedy C, Dromerick AW. Screening patients with stroke for rehabilitation needs: validation of the post-stroke rehabilitation guidelines. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2006 Mar;20(1):42–48. doi: 10.1177/1545968305283038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dromerick AW, Lang CE, Birkenmeier RL, et al. Very Early Constraint-Induced Movement during Stroke Rehabilitation (VECTORS): A single-center RCT. Neurology. 2009 Jul 21;73(3):195–201. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ab2b27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000 Dec 12;55(11):1724–1726. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. APPL PSYCH MEAS. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinar D, Gross CR, Price TR, Banko M, Bolduc PL, Robinson RG. Screening for depression in stroke patients: the reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. Stroke. 1986 Mar-Apr;17(2):241–245. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agrell B, Dehlin O. Comparison of six depression rating scales in geriatric stroke patients. Stroke. 1989 Sep;20(9):1190–1194. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997 Jun;12(2):277–287. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarz N, Oyserman D. Asking questions about behavior: Cognition, communication, and questionnaire construction. Am J Eval. 2001 Spring-Summer;22(2):127–160. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen G, Java R. Memory for Medical History - Accuracy of Recall. Appl Cognitive Psych. 1995 Aug;9(4):273–288. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsieh CL, Hsueh IP, Chiang FM, Lin PH. Inter-rater reliability and validity of the action research arm test in stroke patients. Age Ageing. 1998 Mar;27(2):107–113. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van der Lee JH, De Groot V, Beckerman H, Wagenaar RC, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. The intra- and interrater reliability of the action research arm test: a practical test of upper extremity function in patients with stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001 Jan;82(1):14–19. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Lee JH, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. The responsiveness of the Action Research Arm test and the Fugl-Meyer Assessment scale in chronic stroke patients. J Rehabil Med. 2001 Mar;33(3):110–113. doi: 10.1080/165019701750165916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Field AP. Discovering statistics using SPSS: (and sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll) 3. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michielsen ME, Selles RW, Stam HJ, Ribbers GM, Bussmann JB. Quantifying nonuse in chronic stroke patients: a study into paretic, nonparetic, and bimanual upper-limb use in daily life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012 Nov;93(11):1975–1981. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang CE, Wagner JM, Edwards DF, Dromerick AW. Upper extremity use in people with hemiparesis in the first few weeks after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007 Jun;31(2):56–63. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0b013e31806748bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCombe Waller S, Whitall J. Bilateral arm training: why and who benefits? Neuro Rehabilitation. 2008;23(1):29–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailey RR, Klaesner JW, Lang CE. An Accelerometry-Based Methodology for Assessment of Real-World Bilateral Upper Extremity Activity. PLoS One. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCombe Waller S, Whitall J. Hand dominance and side of stroke affect rehabilitation in chronic stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2005 Aug;19(5):544–551. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr829oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chae J, Johnston M, Kim H, Zorowitz R. Admission motor impairment as a predictor of physical disability after stroke rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1995 May-Jun;74(3):218–223. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fong KN, Chan CC, Au DK. Relationship of motor and cognitive abilities to functional performance in stroke rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 2001 May;15(5):443–453. doi: 10.1080/02699050010005940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]