Summary

Peptide-based vaccines, one of several anti-tumor immunization strategies currently under investigation, can elicit both MHC Class I-restricted (CD8+) and Class II-restricted (CD4+) responses. However, the need to identify specific T-cell epitopes in the context of MHC alleles has hampered the application of this approach. We have tested overlapping synthetic peptides (OSP) representing a tumor antigen as a novel approach that bypasses the need for epitope mapping, since OSP contain all possible epitopes for both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Here we report that vaccination of inbred and outbred mice with OSP representing tumor protein D52 (TPD52-OSP), a potential tumor antigen target for immunotherapy against breast, prostate, and ovarian cancer, was safe and induced specific CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses, as demonstrated by development of specific cytotoxic T cell (CTL) activity, proliferative responses, interferon (IFN)-γ production and CD107a/b expression in all mice tested. In addition, TPD52-OSP-vaccinated BALB/c mice were challenged with TS/A breast carcinoma cells expressing endogenous TPD52; significant survival benefits were noted in vaccine recipients compared to unvaccinated controls (P < 0.001). Our proof-of-concept data demonstrate the safety and efficacy of peptide library-based cancer vaccines that obviates the need to identify epitopes or MHC backgrounds of the vaccinees. We show that an OSP vaccination approach can assist in the disruption of self-tolerance and conclude that our approach may hold promise for immunoprevention of early-stage cancers in a general population.

Keywords: Overlapping Synthetic Peptides (OSP), Vaccine, Cancer, Tumor protein 52

1. Introduction

The goal of therapeutic vaccines against cancer is to induce or enhance immune responses directed against tumor antigens. Peptides derived from tumor-specific (mutated) or tumor-associated antigens are presented in the grooves of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II molecules on cancer cells, where they activate either CD8+ T cells with cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) activity or CD4+ T lymphocytes (T helper) that secrete cytokines capable of inhibiting the growth of tumor cells. An optimal cancer vaccine must therefore contain at least two antigenic epitopes: one that will induce specific CTL responses and a T-helper epitope [1-3].

Currently, several peptide-based vaccines targeting specific tumor antigens are under development [1, 2]. Peptide-based vaccine studies have focused on identifying epitopes that are capable of eliciting either MHC Class I-restricted (CD8+) and/or Class II-restricted (CD4+) responses. Peptide vaccines may have advantages over other tumor vaccine approaches that rely on intact proteins or tumor cells [4, 5]. Several advantages in terms of relative ease of peptide synthesis, chemical stability, storage, delivery, and the lack of oncogenic or infectious potential has made the peptides attractive vaccine candidates for clinical use. However, a major limitation of the widespread usefulness of peptide vaccines is the need to identify specific T-cell epitopes in the context of MHC alleles [6].

In a previous report, we described a novel strategy that bypasses the need for epitope mapping for an outbred population: vaccination with overlapping synthetic peptides (hereafter referred to simply as OSP) [7]. We demonstrated that OSP derived from viral structural proteins induced strong cell-mediated immunity in outbred and different inbred mice. Potential advantages of OSP vaccines are: 1) OSP are promiscuous, as they contain all the peptide sequences comprising their cognate protein, 2) OSP covering short amino acid sequences of a toxic protein are very likely nontoxic, 3) OSP contain all possible epitopes for both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells of a genetically diverse population and can bind to different MHC alleles, 4) OSP contain all possible CTL epitopes, thereby minimizing target sequence variations that would result in loss of, or diminished, recognition by CTL, 5) OSP vaccines can be designed rapidly, because only the amino acid sequence of the target protein is required, and 6) OSP may bind directly by MHC molecules expressed on the cell surfaces or ingested and processed by antigen presenting cells. Therefore, neither epitopes nor MHC alleles need to be identified.

In this study, we evaluated the use of an OSP vaccine corresponding to tumor protein D52 (TPD52) for safety, immunogenicity and anti-tumor efficacy in mice. TPD52 was chosen because 1) it is a small protein (21 kDa, 180 amino acids (aa)) and the entire sequence can be covered with 34 peptides of 15 aa in length, with 10 aa overlaps between sequential peptides and 2) murine orthologue of TPD52 (mD52) represents a “self,” non-mutated tumor-associated antigen (TAA). The mD52 has been cloned and, based on the sequence information, is predicted to be 86% identical to human TPD52 [8]. The human TPD52 gene family is comprised of four genes, hD52, hD53, hD54 and hD55 [8-11]. TPD52 proteins are involved in several cell functions, such as exocytotic secretion, vesicle trafficking, calcium-mediated signal transduction, cell proliferation and apoptosis [10]. The human D52 locus has been mapped to chromosome 8q21, a chromosome band that is frequently overrepresented in human cancer. Several reports have shown that hD52 is overexpressed in cancers of the breast, lung, prostate, colon, and ovary, as well as in B-cell malignancies [12-15]. Also, expression of TPD52 has been reported in some normal tissues in inbred and outbred mice [16-18]. It has been shown that hD52 and hD53 genes encode markers or regulators of cancer-cell proliferation [8], suggesting that TPD52 may be important for initiating and perhaps maintaining a tumorigenic and metastatic phenotype. Recent data also showed that mD52 expression initiated cellular transformation, tumorigenesis, and progression to metastasis [17].

Briefly, our results conclude that TPD52-OSP vaccination was safe and effective in inducing CTL responses with anti-tumor activity in mice. In a breast-cancer cell challenge model, TPD52-vaccinated mice had a significantly prolonged survival compared to control mice. In addition, activation of T cells directed against the tumor-associated self-antigen was without noticeable development of autoimmunity. The information provided by this study may be useful for the development of peptide-based vaccines without identifying either epitopes or MHC backgrounds of the vaccinees.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Peptides

Tumor Protein D52 (TPD52)-OSP consisted of a group of 34 peptides of 15 aa in length, with 10 aa overlaps between sequential peptides representing the murine form of TPD52; these peptides were custom-made by Millipore/Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) clade B Tat (Tat-OSP, also termed Control-OSP) consisted of 23 peptides of 15 aa in length, with 5 aa overlaps between sequential peptides; the peptides were obtained from the AIDS Research Reagent Repository Program (ARRRP; NIAID, NIH).

2.2. Cell lines

TS/A cells, a spontaneous murine mammary adenocarcinoma cell line of BALB/c origin, were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with L-glutamine, antibiotics and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). P815 cells (mastocytoma cells; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with L-glutamine, antibiotics and 10% FBS.

2.3. TPD52 expression analysis

To determine expression of mD52 in parental TS/A cells and different tissues (breast, liver, thymus, kidney, heart and spleen tissue), total RNA was extracted by TriZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), treated with RNase-free DNase and used for amplification in an RT-PCR reaction using the SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Two μl of total RNA were processed in a 50 μl final volume, the reverse transcription cycles consisted of 1 cycle of 30 min at 50°C; 2 min at 94°C, followed by PCR amplification using primer pairs for mD52: forward: 5′-AAGGTCTGCTGAAGACAGAGC-3′; and mD52 reverse: 5′-TGTGGAATTCAGGACTTCTC-3′, and the housekeeping gene product; glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Invitrogen) as internal control. The final amplification consisted of 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. The PCR was terminated by elongation at 72°C for 10 min. The results were visualized on 2% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

2.4. Mice

Eight to ten-week old outbred NMRI (Harlan, IN) and inbred BALB/c (H-2d) (Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY) mice were housed and cared for in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council.

2.5. Immunization protocol

Mice were immunized subcutaneously with TPD52-OSP at 5 μg of each individual peptide in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) per mouse together with MPL+TDM Adjuvant System (Sigma) or CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODNs) (Coley Pharmaceutical, Wellesley, MA) (50 μg) plus Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA) (for some of the tumor challenge studies). Control mice were immunized subcutaneously with either with Control-OSP (Tat-OSP), PBS or adjuvant only. Immunizations were given at weeks 0, 3, and 6. Mice were euthanized 10 days after the last boost and their spleens were collected to evaluate cellular immune responses.

2.6. Cell proliferation assay

Splenocytes (5 × 105) from vaccinated and control mice (NMRI, BALB/c) were cultured with either TPD52-OSP, Tat-OSP (1 μM) or no OSP for 4 days in 96-well U-bottomed plates, then pulsed with 1 μCi/well [3H]thymidine overnight. After cells were harvested, [3H]thymidine incorporation was assessed using a β-counter (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). The data were recorded by using the stimulation index (SI), calculated as the ratio of cpm of stimulated cells to cpm of cells grown in medium only.

2.7. IFN-γ ELISPOT assays

Assays were performed using mouse ELISPOT kits from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA) as described by the supplier. Splenocytes from NMRI and BALB/c mice were restimulated overnight with 1 μM OSP in the IFN-γ pre-coated plates.

2.8. Intracellular IFN-γ assay

Splenocytes were harvested from immunized and control mice and incubated for 18 h at 37°C in 96 U-well plates at 5 × 105 cells/well together with 1 μM OSP. During the last 4 hours, 1 μl/well GolgiStop (BD Pharmingen) was added to the culture. Cells were stained with 1 μg/well FITC-labeled anti-mouse CD8 and CD4 monoclonal antibody (mAb; BD Pharmingen). Following surface labeling, the cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde (20 min, 4°C) and then permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (10 min, 4°C) before intracellular labeling with 0.5 μg/well PE-labeled rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (BD Pharmingen) for 20 min at 4°C. After a final wash, the cells were resuspended in FACS buffer and analyzed immediately by FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

2.9. In vitro CTL activity assay

Ten days after final vaccination, BALB/c mouse splenocytes were harvested. Splenocytes from vaccinated and control mice were cultured with OSP (5 μM) and recombinant interleukin-2 (rIL-2) (20 U/ml) for 5 days in 24-well plates. Cytolytic activity of the T-cell cultures was assessed by standard 4- to 6-h 51Cr release assays, using different ratios of effector (E) to target cells (T). As targets, either P815 (H-2d) cells or TS/A cells were labeled with 51Cr for 90 min at 37°C, washed, and 104 P815 cells were incubated with TPD52-OSP or Control-OSP overnight. All experiments were repeated at least two times, and representative results are shown. The mean percentage of specific lysis in triplicate wells was calculated by the standard formula ([(release by CTL − release by targets alone) / (release by 5% Triton-X100 − release by targets alone)] × 100%). Maximum release was determined from supernatants of cells that were lysed by addition of 5% Triton-X100. Spontaneous release was determined from the target cells without addition of effector cells.

2.10. CD107a/b (lysosome-associated membrane protein, LAMP-1/2) expression assay

Splenocytes from individual groups of BALB/c mice were cultured for 5 days at 37°C in 24 well plates at 5 × 106 cells/well together with 20 U/well rIL-2 and 5 μM TPD52-OSP or Tat-OSP in accordance with the prior immunization. Splenocytes from control mice given adjuvant only were cultured with rIL-2 only. Splenocytes were washed and resuspended in supplemented RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) and stimulated with TS/A cells (at an E:T ratio of 5:1); medium alone served as the negative control. FITC-labeled anti-mouse-CD107a & b (10 μl/ml) (BD Pharmingen) were added directly to the wells to detect degranulation. Following 1 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, 1 μl of monensin (Golgi-stop; BD Biosciences) was added for a final concentration of 6 μg/ml and incubated for an additional 5 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Samples were then surface-stained using PE-labeled anti-mouse CD8. After washing, cells were resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) until multicolor flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur.

2.11. Tumor challenge

BALB/c mice (10/group) were immunized subcutaneously according the immunization protocol. To induce lung metastases, mice were challenged intravenously with 103 or 5 × 103 TS/A tumor cells in 100 μl of Hanks solution (Invitrogen) 10 days after the final immunization and followed prospectively. TPD52-OSP vaccine recipients and control groups were monitored regularly for any distress and weight loss. Mortality rate was tracked daily, and mice were euthanized for humane reasons when they lost > 15% of body weight.

2.12. Immunohistochemistry and histopathology on tissue sections

Analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue was performed on 5 μm-thick sections that were deparaffinized through xylene and 100% ethanol and blocked for endogenous peroxidase activity by incubation in 0.3% H2O2-absolute methanol for 10 min. Sections were fixed with acetone before staining with rabbit polyclonal anti-CD3 antibody (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA). Matched sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Slides were analyzed using an Olympus BX51 microscope. Photomicrographs were taken with a Q Imaging micropublisher 3.3 RTV digital camera.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Survival data were analyzed using the method of Kaplan and Meier [19]. Differences were tested using the log rank test. Two-sided p-values are presented. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. TPD52 expression in the TS/A cell line and in normal murine tissues

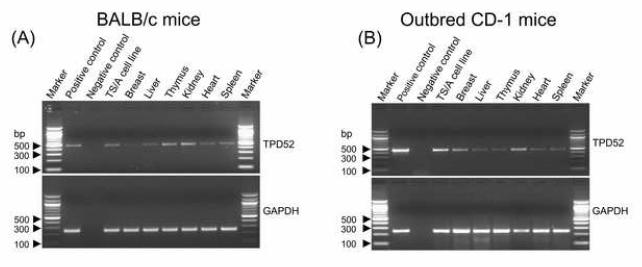

Murine D52 naturally mirrors human TPD52 with respect to known function and expression in tumor cells compared to normal cells and tissues, and thus represents a “self,” non-mutated TAA with direct relevance to several human cancers, including prostate, breast, lung, ovarian and colon carcinomas. We tested the expression of mD52 in cultured TS/A breast carcinoma cells and normal mouse tissues, such as thymus, kidney, liver, heart, mammary tissue, and spleen. Total RNA was isolated from the TS/A cell line and tissues as described in Materials and Methods. PCR amplification demonstrated expression of mD52 in the TS/A cell line, mammary tissue, and several mouse tissues (Fig. 1); the highest level of expression was in TS/A cells and the kidney.

Figure 1.

TPD52 expression in the TS/A cell line and tissues from normal BALB/c mice (A) and outbred CD-1 mice (B). PCR amplification is shown for mD52 (top panels) and the housekeeping gene GAPDH (bottom panels). Plasmid mTPD52 was used as positive control for the PCR and amplification without template cDNA was used as negative control.

3.2. OSP induced cell-mediated immunity (CMI) in mice

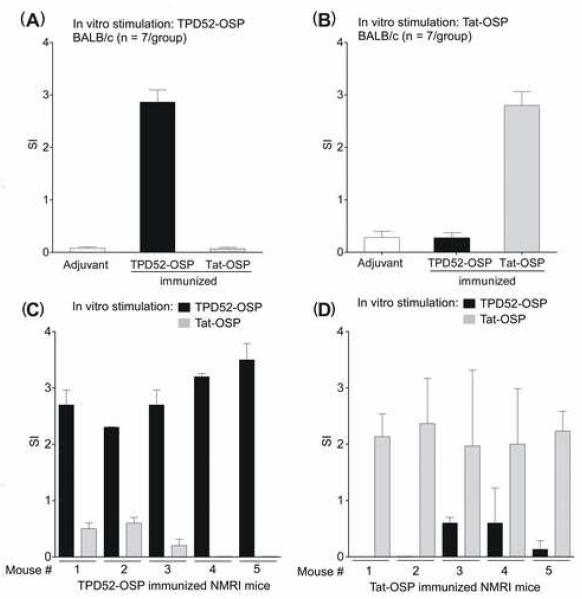

To determine the safety and immunogenicity of TPD52-OSP vaccination in genetically diverse hosts, groups of inbred mice (n = 7 per group) and outbred NMRI mice (n = 5 per group) were used. The latter were derived from outbred Swiss mice by random breeding; these mice do not tolerate skin grafts from each other and express MHC molecules that are similar to H-2q but differ between individuals of the same strain. Mice were immunized either with; TPD52-OSP, Tat-OSP, or PBS and adjuvant only. All animals tolerated the immunization series without untoward effects. Ten days after the last boost, splenocytes from these mice were cultured with the two corresponding OSP or in medium only in vitro. Proliferative responses were examined by [3H]thymidine incorporation. Pooled splenocytes from TPD52-OSP-immunized BALB/c (Fig. 2A and B) and splenocytes from individual NMRI mice (Fig. 2, C and D) only showed significant proliferative responses when restimulated with TPD52-OSP but not with Tat-OSP; the converse was true for Tat-OSP-immunized animals.

Figure 2.

Antigen-specific proliferative responses induced by OSP immunization in inbred BALB/c and outbred NMRI mice. BALB/c mice were immunized either with TPD52-OSP or Tat-OSP. Control mice received adjuvant only. Ten days after the last boost, pooled BALB/c splenocytes were stimulated overnight with either TPD52-OSP (A) or Tat-OSP (B) and proliferation was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation. SI, stimulation index as per Material and Methods. Outbred NMRI mice were immunized with either TPD52-OSP (n = 5) (C) or Tat-OSP (D), and 10 days after the last boost, proliferation of splenocytes from the individual mice was measured by [3H]thymidine incorporation.

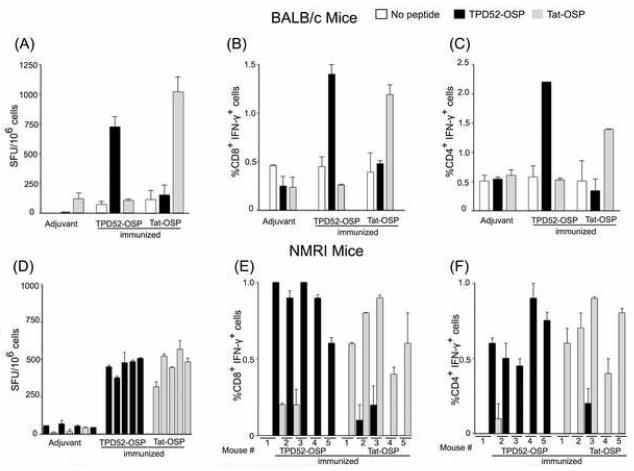

Next, we examined the production of IFN-γ in mice by ELISPOT analysis and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) in the cohorts of TPD52-OSP or Tat-OSP-vaccinated or control mice. As shown in Fig. 3A and D, the number of spot-forming units (SFU) was higher in splenocytes in the TPD52-OSP or Tat-OSP immunized mice when the cells were restimulated in vitro with the corresponding OSP compared to control mice. Restimulation of splenocytes with corresponding OSP yielded between 714 and 998 SFU/106 for BALB/c mice and 305 and 567 SFU/106 for outbred NMRI mice. Measured directly without in vitro restimulation, SFU ranged between 72 and 116 SFU/106 splenocytes in BALB/c mice and 11 and 56 SFU/106 in NMRI mice (TPD52-OSP and Tat-OSP vaccinated mice), respectively; the corresponding numbers for the adjuvant controls were 11-120 SFU/106 splenocytes. In addition, ICS showed that after restimulation with the corresponding peptides, TPD52-OSP and Tat-OSP-immunized BALB/c mice had an increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells from 0.45% to 1.4% and from 0.39% to 1.19% (Fig. 3B), respectively, and an increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells from 0.57% to 2.2% and from 0.51% to 1.39% (Fig. 3C), respectively. We observed similar results in outbred NMRI mice (Fig. 3E and F). Of note, every single one of these random-bred mice showed increases in ICS after specific restimulation with peptides corresponding to the OSP immunogens. Together, these results demonstrate that vaccination with OSP was safe and induced specific T-cell responses, involving both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, in an inbred population (BALB/c) and within each animal of a genetically diverse population of NMRI mice.

Figure 3.

Antigen-specific IFN-γ production induced by OSP immunization in inbred BALB/c (A-C) and outbred NMRI mice (D-F) as measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT analysis or intracellular cytokine staining (ICS). Animals were immunized as described in the legend to Figure 2. Ten days after the last immunization, splenocytes from BALB/c mice were pooled and stimulated in vitro with or without relevant OSP overnight. The number of spot-forming units (SFU) was determined by ELISPOT analysis (A). (B, C) ICS. D, ELISPOT analysis and (E, F) ICS of individual NMRI mice vaccinated as above.

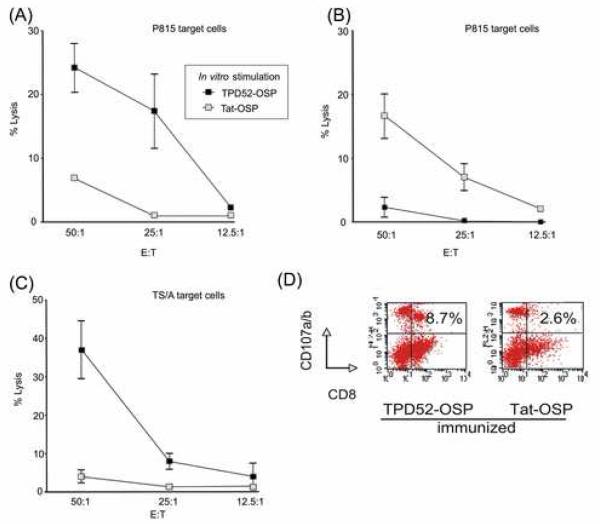

3.3. Assessment of CTL activity in vitro

To assess the functionality of the CD8+ TPD52-specific cellular immune responses, the 51Cr-release assay was used to measure antigen-specific CTL activity in OSP-immunized and control BALB/c mice. Splenocytes from immunized mice were expanded in vitro in the presence of OSP and rIL-2 for 5 days and used as effector cells. As targets, either P815 cells (H-2d) were pulsed with relevant OSP and labeled with 51Cr or TS/A cells were labeled with 51Cr, and used at different E:T ratios (Materials and Methods). Specific CTL responses were induced by OSP-immunization in all mice, as indicated by specific lysis of MHC-matched P815 cells loaded with corresponding OSP (Fig. 4, A and B) (p < 0.005, p < 0.01). In addition, to confirm antigen-specific lysis, we used TS/A tumor cells (the same tumor cell line that used for in vivo challenge) as targets (Fig. 4C) (p < 0.01). These results indicate that by OSP immunization, antigen-specific CTL activity generated and CTL can kill tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Quantification of antigen-specific CTL activity and degranulation of TPD52-specific CD8+ T cells in OSP-immunized mice. Splenocytes from (A), TPD52-OSP- and (B), Tat-OSP-immunized BALB/c mice were expanded in vitro in the presence of OSP and rIL-2 for 5 days and used as effector cells. As target cells, P815 cells (H-2d) were labeled with 51Cr and then loaded with OSP. (C), TPD52-OSP- and Tat-OSP-immunized BALB/c mice were used as donors of effector cells and restimulated with TPD52-OSP. TS/A cells were labeled with 51Cr and used as target cells. Target cells were mixed with various numbers of effector cells. E:T, effector-to-target cell ratio. (D), Splenocytes from BALB/c mice given TPD52-OSP or Tat-OSP were cultured with rIL-2 and the corresponding OSP. Restimulated splenocytes were then mixed with TS/A tumor cells. FITC-labeled anti-mouse-CD107a & b were added directly to the wells to detect degranulation.

3.4. Degranulation of TPD52-specific CD8+ T cells in response to in vitro stimulation with TS/A tumor cells

To confirm specific targeting of syngeneic tumor cells, we assessed the expression of CD107a and b (LAMP-1 and LAMP-2) in CD8+ T cells following immunization. Degranulation of intracellular vesicles by lymphocytes can be measured using CD107a and b, as described recently for CD8+ T cells [20]. Degranulation is accompanied by the transport of the CD107a and b proteins to the cell surface, followed by immediate reinternalization. Surface expression of the CD107a and b markers on actively degranulating CD8+ T cells is inversely correlated with the presence of perforin and directly correlated with cytotoxic activity [20]. Thus, expression of CD107 is directly correlated with cytotoxic activity.

Splenocytes were harvested from TPD52-OSP and Tat-OSP-immunized BALB/c mice and cultured with the corresponding OSP as described in Materials and Methods; splenocytes from mice given adjuvant only were grown in rIL-2 without peptides. Based upon the expression of CD107a/b by FACS analysis, 8.7% of TPD52-OSP-restimulated splenocytes from TPD52-OSP-immunized mice responded to TS/A tumor cells and degranulated, presumably lysing target cells (Fig. 4D, left panel). In contrast, only 2.6% of Tat-OSP-restimulated splenocytes from Tat-OSP-immunized mice were CD8+CD107a/b+ when brought in contact with TS/A tumor cells (Fig. 4D, right panel), which was similar to the 2.2% CD8+CD107a/b+ splenocytes from control mice given adjuvant only. This degranulation assay thus confirmed our standard 51Cr-release cytotoxicity assay. Together, these data show that OSP immunization generated peptide-specific CTL activity and that activated CTL underwent degranulation, released IFN-γ and effectively killed TS/A tumor cells, which express endogenous mD52 as shown in Fig. 1. Thus, TPD52-OSP immunization effectively broke tolerance and generated specific CTL against tumor cells overexpressing the corresponding TAA.

3.5. Anti-tumor effects of TPD52-OSP vaccination in BALB/c mice

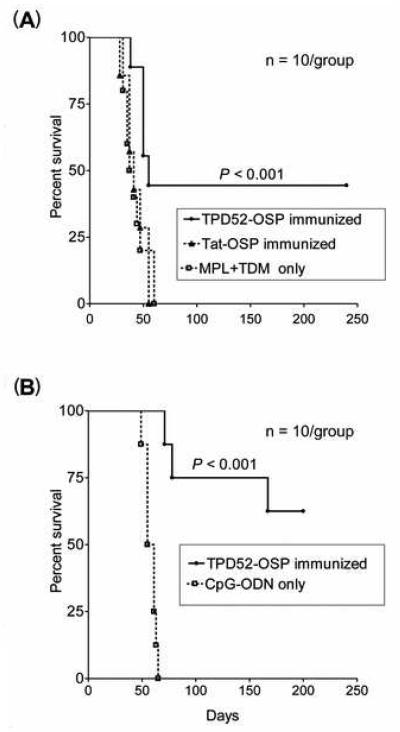

Our next goal was to examine in vivo whether vaccination with OSP could protect BALB/c mice against syngeneic tumor cell challenge. Mice were immunized with TPD52-OSP or Control-OSP at 5 μg of each individual peptide in PBS per mouse together with MPL+TDM adjuvant. As additional control, a group of mice was given adjuvant only. Ten days after the last immunization, all mice were inoculated intravenously with 103 TS/A tumor cells and monitored prospectively for development of metastatic disease as described (Materials and Methods). TPD52-OSP-vaccinated mice showed a delayed tumor growth and weight loss pattern compared to control mice, all of which died around day 55 post tumor challenge (Fig. 6A). In contrast, TPD52-OSP-immunized mice had a 40 percent long-term survival rate (p < 0.001). No significant survival difference was observed between mice given Tat-OSP or MPL+TDM adjuvant only (p < 0.6).

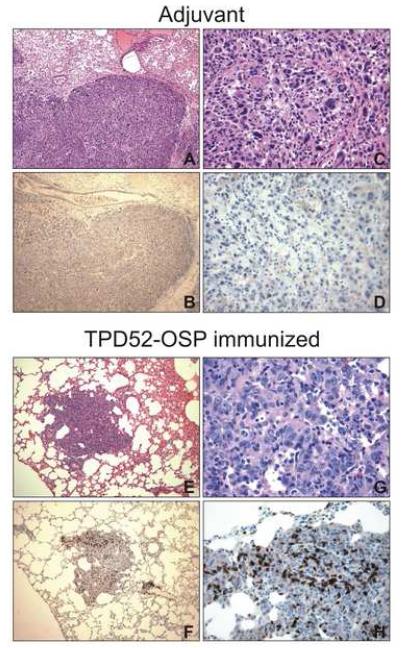

Figure 6.

CD3+ lymphocyte infiltration in lungs of immunized mice. Sections from the lungs were subjected to either H&E staining (A, C, E, F) to reveal tissue topography or immunohistochemistry (IHC) with polyclonal anti-CD3 antibody (B, D, F, H). CD3+ cells were seen as brown cells. Magnification at 10x (left column) and 40x (right column).

Immunized mice undergoing necropsy were also routinely assessed for evidence of autoimmunity. We observed no abnormal lymphocytic infiltrates into organs, such as liver, heart and kidney (data not shown). These observations have been confirmed in another study [18].

Recruitment of innate immunity by optimizing adjuvants may result in improved anti-tumor CTL responses. Enhancing the interaction between T cells and antigen presenting cells (APC) by attracting larger numbers of APC and/or stimulating their function may thus yield greater anti-tumor immune responses. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG-ODNs) have been shown to activate APC (particularly tissue dendritic cells), leading to up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and the secretion of cytokines necessary for T lymphocyte activation [21-23]. To augment the immunogenicity of our OSP vaccine strategy, we selected CpG-ODN as adjuvant. Mice were immunized with TPD52-OSP plus CpG-ODN in IFA and then challenged with TS/A tumor cells (5 × 103 tumor cells/mouse). Fig. 5B shows that CpG-ODN enhanced the anti-tumor effects of TPD52-OSP vaccination and improved the long-term survival rate (62.5%) (p < 0.001); the median survival exceeded 170 days, compared to 65 days in the vaccine trial involving MPL+TDM as adjuvant for the TPD52-OSP vaccine.

Figure 5.

Anti-tumor efficacy of TPD52-OSP vaccination in BALB/c mice. Ten days after the last immunization with (A), MPL+TDM adjuvant, or (B), CpG-ODN adjuvant, BALB/c mice were challenged with TS/A cells (103 and 5 × 103 cells, respectively). Control groups consisted of mice given the irrelevant Tat-OSP with adjuvant or adjuvant only. The percent survival is shown by Kaplan-Meier plot; log rank analysis was used to determine statistically significant differences between TPD52-OSP-immunized and control mice (p < 0.001).

3.6. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on tissue sections

Next, we sought to test whether TPD52-OSP-immunized mice had more tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in pulmonary tissues compared to control mice. Lung tissue sections were stained by IHC for CD3+ cells. Mice vaccinated with TPD52-OSP showed high numbers of CD3+ cells in the tumor tissue (Fig. 6, F and H). This pattern of lymphocytic infiltration was in stark contrast to that observed in the control mice (Fig. 6, B and D). High numbers of tumor-infiltrating CD3+ cells were significantly associated with small tumor size and better survival rates of the TPD52-OSP vaccinated mice.

In a separate study, macroscopic examination of lungs of TPD52-OSP and Tat-OPS-immunized mice and mice given adjuvant only (MPL+TDM) revealed significantly reduced lung metastases in vaccinees compared to the two controls. In this experiment, higher numbers of tumor cells were inoculated (2 × 105 as opposed 1 × 103 TS/A cells). Consistent with the smaller size of the lung nodules, the mean lung weight of TPD52-OSP-immunized mice was lower than that of control mice (336 mg versus 556 mg for mice given Tat-OPS and 553 mg for mice given adjuvant only; p= 0.0285 by Student’s T test comparing vaccinees versus the combined controls).

Together, these data show that TPD52-OSP vaccination induced specific cellular immune responses that resulted in the rejection of TPD52+ tumors. Of note, our OSP vaccination strategy successfully overcame peripheral T-cell tolerance against the TPD52 self-antigen without inducing autoimmunity.

4. Discussion

Peptide-based vaccines are among one of several approaches that are presently being pursued as cancer vaccines. The relative ease of their production, storage, delivery, their chemical stability, lack of infectious potential without the risk of genetic integration or recombination has made peptides attractive vaccine candidates. The concept of peptide vaccines is based on identification and chemical synthesis of T-cell epitopes, which are immunodominant and can induce specific immune responses. Vaccines based upon several peptides have undergone clinical trials for cancer immunotherapy [1, 2, 4, 24-30].

However, the main obstacle associated with peptide vaccines based upon defined T-cell epitopes is the need to identify the latter in the context of MHC alleles. In patients, this generally restricts a peptide vaccine approach to individuals with HLA A2, unless mixtures of peptides tailored for additional HLA alleles are employed as recently described by Slingluff et al. [27, 31].

We have demonstrated in the past that an OSP vaccine derived from viral structural proteins can elicit robust CMI in multiple strains of outbred and inbred mice [7]. In the present study, we selected TPD52 as a model because it represents a “self” tumor antigen overexpressed in the cells used as tumor challenge. The human ortholog is overexpressed in various tumors, including breast, prostate, lung and colon carcinomas. Many TAAs have been shown to be expressed during fetal development. Therefore, weak host immune response to such “self-TAAs” would be expected. In addition, the induction of immune responses to a self-antigen raises the concern of development of autoimmunity. Here, we report that our OSP vaccine strategy corresponding to endogenous TPD52 led to strong peptide-specific cell-mediated immunity (CMI) and more importantly, reduced tumor growth and increased survival of mice bearing tumors. We observed a 40 percent long-term survival rate in TPD52-OSP immunized mice in our initial tumor challenge study.

In a separate experiment, we utilized CpG-ODN as adjuvant to enhance the ability of antigen presentation and to induce costimulatory molecules on APC, as well as to secrete cytokines that mediate proliferation and maturation of effector cells [32]. It has been shown that CTL populations that specifically target cancer cells can be expanded by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, which increase the cross talk between the innate and adaptive immune systems [33]. Switching to CpG-ODN as adjuvant increased the survival rate for TPD52-OSP-immunized mice to 62.5%, suggesting that this vaccination induced effective cellular immunity that resulted in the rejection of TPD52+ tumors without the development of adverse autoimmunity. A recent study has also shown that immunization with recombinant mD52 protein with CpG/ODN resulted 40-50% in the rejection of tumors over-expressing mD52 protein [18].

Studies have demonstrated that tumor-specific CD4+ T helper (Th) cells critically contribute to the development and efficacy of anti-tumor responses [1, 4, 34-38]. The effectiveness of Th cells probably for their capacity to deliver necessary signals to professional APC needed for tumor-specific CTL priming [39-41]. In addition, antigen-specific CD4+ T cells may provide CTL with necessary growth stimuli during the effector phase [42]. It would also be valuable to induce CTL responses against a wide range of various epitopes to minimize the generation of tolerized T cells. Since OSP contain all possible epitopes for the CD4+ as well as CD8+ T cells of a genetically diverse population, OSP can offer pivotal antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell help to induce, expand, and sustain an effective CD8+ CTL response.

The mechanisms of tolerance that prevent autoimmunity may also obviate the development of sufficient anti-tumor responses, since most tumor antigens are self-antigens. Therefore, cancer vaccines directed against self-antigens must be able to overcome host tolerance in order to elicit a potent cell-mediated immune response capable of completely eliminating the tumor. OSP contain all possible epitopes of an antigen, not only the immunodominant ones, which have been linked to tolerance [43]. Thus, OSP vaccines, unlike vaccines based upon immunodominant epitopes, can break tolerance.

Vaccines designed to generate an immune response against a self-protein raise safety concerns. The lack of an autoimmune response toward normal cells expressing basal levels of TPD52 may imply that a threshold level of TPD52 expression, such as that present on a tumor cell, is required for initiating an autoimmune response. We detected no autoimmune toxicity in our experiments following immunizations. However, CD3+ cell infiltration in lung metastases was pronounced in TPD52-OSP-vaccinated mice and practically absent in tumor tissue of control mice, implying homing of TPD52-specific lymphocytes in the former group of mice. We conclude that the high degree of tumor infiltration by CD3+ cells and the small tumor size predicted a favorable outcome for the vaccinated mice.

In summary, we have demonstrated that an OSP vaccine targeting TPD52 broke peripheral T-cell tolerance against this self-antigen and induced immune responses that resulted in rejection of TPD52+ tumors in the absence of deleterious autoimmunity. We conclude that our OSP vaccine strategy may be of use for the implementation of peptide-based vaccines without needing to identify either epitopes or MHC backgrounds of the vaccinees. Most importantly, our OSP cancer vaccine strategy could benefit individuals of all genetic backgrounds, not just those with HLA A2. Given that hTPD52 is overexpressed in a variety of human cancers, our novel anti-TPD52 vaccination strategy may hold promise against malignancies other than breast cancer, for which we have provided proof-of-concept in the murine model.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. R. Bronson (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for histology support, Dr. M. Humbert for graphical support, and E. L. Hall-Meyers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) for technical support and Susan Sharp for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Claudia Adams Barr Award 9616397 to S.M. and NIH grant PO1 AI048240 to R.M.R.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Berzofsky JA, Oh S, Terabe M. Peptide vaccines against cancer. Cancer Treat Res. 2005;123:115–36. doi: 10.1007/0-387-27545-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Purcell AW, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. More than one reason to rethink the use of peptides in vaccine design. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(5):404–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411(6835):380–4. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Disis ML, Grabstein KH, Sleath PR, Cheever MA. Generation of immunity to the HER-2/neu oncogenic protein in patients with breast and ovarian cancer using a peptide-based vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(6):1289–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Disis ML, Gooley TA, Rinn K, Davis D, Piepkorn M, Cheever MA, et al. Generation of T-cell immunity to the HER-2/neu protein after active immunization with HER-2/neu peptide-based vaccines. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(11):2624–32. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Singh-Jasuja H, Emmerich NP, Rammensee HG. The Tubingen approach: identification, selection, and validation of tumor-associated HLA peptides for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53(3):187–95. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiang S, Song R, Popov S, Mirshahidi S, Ruprecht RM. Overlapping synthetic peptides as vaccines. Vaccine. 2006;24(37-39):6356–65. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Byrne JA, Mattei MG, Basset P. Definition of the tumor protein D52 (TPD52) gene family through cloning of D52 homologues in human (hD53) and mouse (mD52) Genomics. 1996;35(3):523–32. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Byrne JA, Nourse CR, Basset P, Gunning P. Identification of homo- and heteromeric interactions between members of the breast carcinoma-associated D52 protein family using the yeast two-hybrid system. Oncogene. 1998;16(7):873–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cao Q, Chen J, Zhu L, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Sha J, et al. A testis-specific and testis developmentally regulated tumor protein D52 (TPD52)-like protein TPD52L3/hD55 interacts with TPD52 family proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344(3):798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Boutros R, Fanayan S, Shehata M, Byrne JA. The tumor protein D52 family: many pieces, many puzzles. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325(4):1115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Balleine RL, Fejzo MS, Sathasivam P, Basset P, Clarke CL, Byrne JA. The hD52 (TPD52) gene is a candidate target gene for events resulting in increased 8q21 copy number in human breast carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2000;29(1):48–57. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1005>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Byrne JA, Balleine RL, Schoenberg Fejzo M, Mercieca J, Chiew YE, Livnat Y, et al. Tumor protein D52 (TPD52) is overexpressed and a gene amplification target in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(6):1049–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Byrne JA, Tomasetto C, Garnier JM, Rouyer N, Mattei MG, Bellocq JP, et al. A screening method to identify genes commonly overexpressed in carcinomas and the identification of a novel complementary DNA sequence. Cancer Res. 1995;55(13):2896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rubin MA, Varambally S, Beroukhim R, Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Paris PL, et al. Overexpression, amplification, and androgen regulation of TPD52 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3814–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Chen SL, Maroulakou IG, Green JE, Romano-Spica V, Modi W, Lautenberger J, et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel gene expressed in multiple cancers. Oncogene. 1996;12(4):741–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lewis JD, Payton LA, Whitford JG, Byrne JA, Smith DI, Yang L, et al. Induction of tumorigenesis and metastasis by the murine orthologue of tumor protein D52. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(2):133–44. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Payton LA, Lewis JD, Byrne JA, Bright RK. Vaccination with metastasis-related tumor associated antigen TPD52 and CpG/ODN induces protective tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0416-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kaplan EL, Meier PR. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observation. Journal of the Americal Statistical Association. 1958;(53):457–81. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Betts MR, Brenchley JM, Price DA, De Rosa SC, Douek DC, Roederer M, et al. Sensitive and viable identification of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells by a flow cytometric assay for degranulation. J Immunol Methods. 2003;281(1-2):65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(03)00265-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Klinman DM, Yi AK, Beaucage SL, Conover J, Krieg AM. CpG motifs present in bacteria DNA rapidly induce lymphocytes to secrete interleukin 6, interleukin 12, and interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(7):2879–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Krieg AM. An innate immune defense mechanism based on the recognition of CpG motifs in microbial DNA. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;128(2):128–33. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Weigel BJ, Rodeberg DA, Krieg AM, Blazar BR. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides potentiate the antitumor effects of chemotherapy or tumor resection in an orthotopic murine model of rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(8):3105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Knutson KL, Schiffman K, Disis ML. Immunization with a HER-2/neu helper peptide vaccine generates HER-2/neu CD8 T-cell immunity in cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(4):477–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Muderspach L, Wilczynski S, Roman L, Bade L, Felix J, Small LA, et al. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus (HPV) peptide vaccine for women with high-grade cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia who are HPV 16 positive. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(9):3406–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Salazar LG, Coveler AL, Swensen RE, Gooley TA, Goodell V, Schiffman K, et al. Kinetics of tumor-specific T-cell response development after active immunization in patients with HER-2/neu overexpressing cancers. Clin Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.08.006. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Slingluff CL, Jr., Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA, Smolkin ME, Hibbitts S, Murphy C, et al. Immunologic and Clinical Outcomes of a Randomized Phase II Trial of Two Multipeptide Vaccines for Melanoma in the Adjuvant Setting. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(21):6386–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Meijer SL, Dols A, Jensen SM, Hu HM, Miller W, Walker E, et al. Induction of circulating tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells after vaccination of melanoma patients with the gp100 209-2M peptide. J Immunother. 2007;30(5):533–43. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3180335b5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Welters MJ, Kenter GG, Piersma SJ, Vloon AP, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, et al. Induction of tumor-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell immunity in cervical cancer patients by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 long peptides vaccine. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(1):178–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rusakiewicz S, Molldrem JJ. Immunotherapeutic peptide vaccination with leukemia-associated antigens. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(5):599–604. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Slingluff CL, Jr., Chianese-Bullock KA, Bullock TN, Grosh WW, Mullins DW, Nichols L, et al. Immunity to melanoma antigens: from self-tolerance to immunotherapy. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:243–95. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mescher MF, Curtsinger JM, Agarwal P, Casey KA, Gerner M, Hammerbeck CD, et al. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Celis E. Toll-like receptor ligands energize peptide vaccines through multiple paths. Cancer Res. 2007;67(17):7945–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ossendorp F, Toes RE, Offringa R, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ. Importance of CD4(+) T helper cell responses in tumor immunity. Immunol Lett. 2000;74(1):75–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ito D, Albers A, Zhao YX, Visus C, Appella E, Whiteside TL, et al. The wild-type sequence (wt) p53(25-35) peptide induces HLA-DR7 and HLA-DR11-restricted CD4+ Th cells capable of enhancing the ex vivo expansion and function of anti-wt p53(264-272) peptide CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177(10):6795–803. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Garcia-Hernandez Mde L, Gray A, Hubby B, Kast WM. In vivo effects of vaccination with six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate: a candidate antigen for treating prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1344–51. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Perales MA, Wolchok JD. CD4 help and tumor immunity: beyond the activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(10):881–2. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.08.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Velders MP, Markiewicz MA, Eiben GL, Kast WM. CD4+ T cell matters in tumor immunity. Int Rev Immunol. 2003;22(2):113–40. doi: 10.1080/08830180305220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393(6684):478–80. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393(6684):474–8. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393(6684):480–3. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kobayashi H, Ngato T, Sato K, Aoki N, Kimura S, Tanaka Y, et al. In vitro peptide immunization of target tax protein human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-specific CD4+ helper T lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(12):3814–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Grossmann ME, Davila E, Celis E. Avoiding Tolerance Against Prostatic Antigens With Subdominant Peptide Epitopes. J Immunother. 2001;24(3):237–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]