Abstract

Despite the significant progress on iron reduction by thermophilic microorganisms, studies on their ability to reduce toxic metals are still limited, despite their common co-existence in high temperature environments (up to 70°C). In this study, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, an obligate thermophilic methanogen, was used to reduce hexavalent chromium. Experiments were conducted in a growth medium with H2/CO2 as substrate with various Cr6+ concentrations (0.2, 0.4, 1, 3, and 5 mM) in the form of potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7). Time-course measurements of aqueous Cr6+ concentrations with the 1, 5-diphenylcarbazide colorimetric method showed complete reduction of the 0.2 and 0.4 mM Cr6+ solutions by this methanogen. However, much lower reduction extents of 43.6%, 13.0%, and 3.7% were observed at higher Cr6+ concentrations of 1, 3 and 5 mM, respectively. These lower extents of bioreduction suggest a toxic effect of aqueous Cr6+ to cells at this concentration range. At these higher Cr6+ concentrations, methanogenesis was inhibited and cell growth was impaired as evidenced by decreased total cellular protein production and live/dead cell ratio. Likewise, Cr6+ bioreduction rates decreased with increased initial concentrations of Cr6+ from 13.3 to1.9 µM h−1. X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy revealed a progressive reduction of soluble Cr6+ to insoluble Cr3+ precipitates, which was confirmed as amorphous chromium hydroxide by X-ray diffraction and selected area electron diffraction pattern. However, a small fraction of reduced Cr occurred as aqueous Cr3+. Scanning and transmission electron microscope observations of M. thermautotrophicus cells after Cr6+ exposure suggest both extra- and intracellular chromium reduction mechanisms. Results of this study demonstrate the ability of M. thermautotrophicus cells to reduce toxic Cr6+ to less toxic Cr3+ and its potential application in metal bioremediation, especially at high temperature subsurface radioactive waste disposal sites, where the temperature may reach ∼70°C.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dissimilatory microbial reduction of metals is a common mechanism for bacteria and archaea to obtain energy to support their growth under anaerobic conditions (Lovely, 1993; Nies, 1999; Lloyd, 2003; Gadd, 2010; Lovely, 2013). A substantial number of metal reducing bacteria have been isolated from a variety of environments and their ability to respire different metals and metalloids has been well documented (Lloyd et al., 2003; Gadd, 2010; Lovely, 2010, 2012; Satyanarayana et al., 2013). Because of their small sizes, high surface area to volume ratio, and metabolic versatility, microbes can strongly interact with metals and regulate their fate in various environments by altering their physical and chemical states, which affect their solubility, mobility, bioavailability, and toxicity (Barkay and Schaefer, 2001; Gadd, 2004). The ability of microorganisms to use metals as terminal electron acceptors (TEAs) allows for alternative remediation methods at metal contaminated sites over the traditional physical and chemical methods (Liu et al., 2002; Satyanarayana et al., 2013; Lovely, 2013).

Since the first discovery of Fe3+ reduction by thermophilic enrichment cultures (Slobodkin et al., 1995), many studies have shown that thermophilic bacteria and archaea are capable of growing organotrophically with fermentable substrates or chemolithoautotrophically with molecular hydrogen when coupled with reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ (Slobodkin et al., 1997; Vargas et al., 1998; Zavarzina et al., 2002; Kashefi et al., 2002; Gavrilov et al., 2003). Furthermore, various thermophilic and hyperthermophilic archaea and bacteria have been reported to possess the ability to reduce structural Fe3+ in ferruginous smectite with H2 as an electron donor (Kashefi et al., 2008). The results of these studies suggest the possibility of reduction of toxic metal ions by biogenic Fe2+ in clay minerals as an electron donor (Jaisi et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011; Bishop et al., 2011, 2014). More recently, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, a thermophilic methanogen, has been reported to reduce structural Fe3+ in smectite minerals at 65°C (Zhang et al., 2013). It was suggested that, cooperative and competitive microbial iron reduction and methanogenesis by this archaeon in the presence of clay minerals could have important implications for understanding the biogeochemical cycles of methane and iron on the earth and beyond (Zhang et al., 2013). Despite the significant progress on iron reduction by thermophilic microorganisms, studies on their ability to reduce toxic metals are still limited in comparison with mesophiles. However, thermophilic microorganisms, owing to their ability to survive and flourish under elevated temperatures (∼65 – 70°C), may offer opportunities for bioremediation of heavy metals under such conditions (Brim et al., 2003; Satyanarayana et al., 2013). To date, there exist only a handful of studies on reduction of toxic metals, such as Cr6+, by thermophilic microorganisms. Among them, an anaerobic fermenter, Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus isolated from the Triassic Taylorsville Basin in Virginia was able to reduce Fe3+, [Co3+-EDTA]− and Cr6+ at 55°C (Zhang et al., 1996). Thermus scotoductus SA01 isolated from a South African gold mine and Pyrobaculum islandicum, a hyperthermophilic archaeon, were able to reduce various metals and radionuclides including Fe3+, [Co3+-EDTA]−, Mn4+, U6+, Tc7+, and Cr6+ at 65°C and 100°C, respectively (Kieft et al., 1999; Kashefi and Lovely, 2000). Deinococcus geothermalis, a radiation-resistant thermophilic bacterium and, Bacillus thermoamylovorans, a moderately thermophilic, facultatively anaerobic bacterium, were also shown to possess the ability to reduce Cr6+ at 55°C and 50°C, respectively (Brim et al., 2003; Slobodkina et al., 2007). In addition, a recent study has demonstrated that both the thermophilic methanogen M. thermautotrophicus and mesophilic methanogen Methanosarcina mazei possess the ability to reduce V5+ under both growth and non-growth conditions with various rates and extents depending on different substrates and V5+ concentrations (Zhang et al., 2014).

Among the various forms of chromium in the environment, Cr6+ is considered toxic because it is mutagenic and carcinogenic to biological systems, largely due to its high solubility and strong oxidizing nature. This toxicity of Cr6+ is in contrast to the less soluble and less toxic Cr3+, which readily forms insoluble oxides, hydroxides or sulfates at slightly acidic to alkaline pH conditions (Cervantes et al., 2001; Motzer and Engineers, 2004; McNeill et al., 2012). It has been reported that the application of chromate as a corrosion inhibitor of storage reactors at high temperature radioactive waste disposal sites has become a major problem to local ecosystems (Dresel et al., 2008), partly due to the toxicity of Cr6+. As of 2005, over 50% of the 170 U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) sites were contaminated with chromium (Atlas and Philip, 2005), because of leaks and spills of stock dichromate liquid or solids from canisters (Dresel et al. 2008). The Cr6+ in these canisters is a waste product of nuclear fuel production, nuclear research, and nuclear reactor operations at U.S. DOE facilities (Palmisano and Hazen, 2003).

At these contaminated sites, methanogens are commonly present, such as in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) located in a salt bed in southern New Mexico that was designed by the DOE for permanent disposal of defense-related wastes (Wang and Francis, 2005). In addition, methanogens are also abundant at other subsurface sites such as the Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory (Swedish high-level radioactive waste repository) at depths ranging from 68 to 446 m below sea level (Kotelnikova and Pederson, 1997; Kotelnikova and Pederson, 1998; Pedersen, 1999; Kotelnikova, 2002). In deep subsurface aquifers, concentration of H2(aq.) is usually much higher than in other aquatic environments (e. g., 0.05–100 µM in Äspö granitic groundwaters) (Kotelnikova and Pederson, 1997; Kotelnikova, 2002). Therefore, with hydrogen as electron donor and inorganic carbon (CO2) as electron acceptor and carbon source, autotrophic thermophilic methanogens could play a vital role in metal bioremediation, especially at high temperature subsurface radioactive waste disposal sites, where toxic metals are commonly present. The study of the interactions between thermophilic methanogens and Cr6+, and the potential of these microorganisms to reduce toxic and soluble Cr6+ to insoluble and less toxic Cr3+ is important for chromium remediation.

The objective of this research was to investigate the kinetics and mechanisms of microbial reduction of Cr6+ by M. thermautotrophicus, a thermophilic methanogen. A laboratory based experiment using a pure culture of M. thermautotrophicus was performed at different Cr6+ concentrations under an optimal temperature of 65°C at pH 7 to address the following questions: (i) Is M. thermautotrophicus capable of reducing Cr6+ in aqueous solution? If so, how does the concentration of Cr6+ affect the reduction rate, extent, and cell viability? (ii) How does the kinetics of Cr6+ bioreduction differ at different concentrations of Cr6+? (iii) What is the oxidation state of the reduced chromium and what is the possible end product of bioreduction? (iv) Is the reduction mechanism intracellular or extracellular? Wet chemistry, spectroscopic and microscopic methods were used to investigate the reduction kinetics and to characterize the interactions of thermophilic methanogen with Cr6+ in aqueous solution. Our results demonstrate the ability of M. thermautotrophicus to reduce Cr6+ but bioreduction of Cr6+ slowed or inhibited methanogenesis and cell growth. In addition to its implication for bioremediation, this study also contributes to a better understanding of chromium biogeochemistry in a variety of high temperature subsurface environments.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Methanogen growth

M. thermautotrophicus was kindly provided by Dr. Xiuzhu Dong (Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China). It was routinely cultured in a sulfate-free enrichment culture medium under a strictly anaerobic atmosphere. The medium contained (per liter of DI water) 1.08 g KH2PO4, 1.6 g Na2HPO4, 0.29 g NH4Cl, 0.29 g NaCl, 0.0096 g CaCl2·2H2O, 0.096 g MgCl2·H2O, 4 g NaHCO3, 1.6 g yeast extract, 0.5 g tryptone, 0.5 g peptone, 1 mL of vitamin solution (Kenealy and Zeikus, 1981), 1 mL trace metal solution (Zehnder and Wuhermann, 1977), and 1 mL of 0.1% resazurin (redox indicator). The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.0 by adding 0.1 N HCl as needed. The medium was then transferred to 60 mL serum bottles that were pre-washed with 10% nitric acid and quartz distilledwater followed by degassing with O2-free H2/CO2 gas mix (80:20 v/v) by passing through a hot copper column. After autoclaving at 121°C for one hour, mixed H2/CO2 (80:20) gas was injected into the headspace of the serum bottles until a pressure of 140 kPa was reached. The medium was then inoculated with M. thermautotrophicus inside an anaerobic glove box (filled with 95% N2 and 5% H2, Coy Laboratory Products, Grass Lake, Michigan) and incubated at 65°C. Cells were transferred three times prior to bioreduction experiments.

2.2 Toxicity test

The toxicity of Cr6+ to M. thermautotrophicus cells at various concentrations (0.2, 1, 3 and 5 mM) was tested so that an appropriate range of Cr6+ concentration could be used for the subsequent Cr6+ bioreduction experiments. . M. thermautotrophicus was exposed to Cr6+ under optimal growth conditions for 115 hours. At each time interval, cells were determined to be alive or dead using the LIVE/DEAD® Cell Imaging Kit (Life Technologies Corporation, Eugene, Oregon, USA) according to manufacturer’s recommendations. After ∼15 min incubation, cells were viewed under a fluorescence microscope (AX-70) by using a FITC filter. The ratio of live to dead cells was calculated by counting the individual live (green) and dead (red) cells. To obtain statistically meaningful results, ten fields of view were averaged for each measurement. An artificial mixture of heat-killed (autoclaved at 121°C for an hour) and exponential growth phase M. thermautotrophicus cells was used to test the reliability of the kit.

2.3 Cr6+ bioreduction experiment

This full-scale experiment was performed to determine the ability and kinetics of M. thermautotrophicus to reduce Cr6+ under optimal growth conditions as well as characterization of reduced Cr3+ solid. Cells in the exponential growth phase (1.56 × 109 cells mL−1 as determined by DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) fluorescent stain) were combined with anoxic, filter-sterilized stock solution of potassium dichromate, K2Cr2O7 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo) to final Cr6+ concentrations of 0, 0.2, 0.4, 1, 3 or 5 mM. For each Cr6+ concentration, abiotic (no cells) and heat-killed controls were set up in parallel to the live-cell experiments. For the heat-killed experiment, cells in the exponential growth phase (1.56 × 109 cells mL−1) were autoclaved for 1 hr. Each concentration was run in duplicate and incubated at 65°C. All solutions and cultures were transferred using sterile needles and syringes inside an anaerobic glove box. The bioreduction experiments were run for 100 hours.

2.4 Analytical methods

2.4.1 Chemical analyses

Aqueous Cr6+ concentration was measured spectrophotometrically using the 1, 5-diphenyl carbazide (DPC) colorimetric method (Urone, 1955). At the end of the experiments, Cr3+ concentrations in both solid precipitates and supernatants were analyzed separately by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Agilent Technologies 700 Series) and were used to calculate mass balance. Prior to the measurements, solid precipitates were harvested by centrifugation (10,000 g for 10 min), washed with anoxic DI water and dissolved in 1% HNO3, whereas the supernatant was filtered through 0.2 µm filter to remove any particulates. Total chromium in both the dissolved precipitates and the supernatant were measured with ICP-OES based on a chromium calibration curve created using a potassium dichromate solution with concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 mM.

2.4.2 Protein assay measurement

Cellular protein concentrations at four different Cr6+ concentrations (0.2, 1, 3, and 5 mM) were determined by using the Bradford reagent method to evaluate the change in the methanogen biomass over the course of Cr6+ bioreduction (Bradford, 1976). One mL aliquot of cell culture from the bioreduction serum bottles was collected and placed into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube followed by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min. The cell pellet was washed three times with pre-filtered quartz distilled water (pore size, 0.2 µm) to remove any interfering components from the medium (peptone, tryptone, and yeast extract). To lyse the cells and release their protein, 0.9 mL of the re-suspended cell culture solution was added to 0.1 mL of 0.2 M NaOH followed by heating for 10 min at 100°C. The lysed cells were then centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min and 0.8 mL of the resulting supernatant was mixed with 0.2 mL of the Bradford reagent (Sigma Co. St. Louis, Mo). Protein concentration was measured spectrophotometrically at 595 nm wavelength with bovine serum albumen (BSA) as a standard after 5 min of reaction time (Bradford, 1976).

2.4.3 Methane and hydrogen measurements

Time course methane and hydrogen concentrations were measured to determine the reaction stoichiometry of methanogenesis at various concentrations of Cr6+. At a given time point, 1 mL of headspace gas was withdrawn with a gas-tight syringe and analyzed for CH4 and H2 concentrations with Agilent Technologies gas chromatographic systems (6890 N series). CH4 concentration was analyzed with a flame ionization detector (FID) separated on a capillary column (HP-MOLSIV, 30 m × 0.53 mm; J&W Scientific). H2 concentration was analyzed with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) with a packed column (Shin Carbon 100/120, 2 m × 1 mm; Restek, Belefonte, PA). Based on measured partial pressures of CH4 and H2 in the headspace, the aqueous CH4 and H2 concentrations at equilibrium were calculated by the Gas law and Henry’s law using their respective Henry’s constants (where KH for CH4 at 65°C = 1.51 × 10−3 mol L−1 atm−1, Schwarzenbach et al., 1995; KH for H2 at 65°C = 9.5 × 10−4 mol L−1 atm−1, Canfield et al., 2005).

2.4.4 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

SEM observations were made to identify any morphological changes of M. thermautotrophicus upon exposure of Cr6+ and to identify the mineral phase of reduced chromium. Among the five different Cr6+ concentrations, the 0.4 mM, 1 mM, and 3 mM Cr6+ samples were observed under SEM. Cells and reduced chromium precipitates were first fixed inside an anaerobic glove box for 20 min with 2% formaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a 0.05 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at a 1:1 ratio (sample: fixative). After this primary fixation, a few drops of sample suspension were placed over the surface of a glass cover slip and sequentially dehydrated using varying proportions of ethanol followed by critical point drying with a Tousimis Samdri-780A Critical Point Dryer (CPD). Critical point dried samples were coated with carbon using Denton Vacuum Evaporator DV-502A. A Zeiss Supra 35 VP SEM with Genesis 2000 X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) was employed for cell imaging and morphological and compositional analyses of the reduced chromium phases.

2.4.5 Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM/EDS coupled with STEM (scanning transmission electron microscopy) were employed to observe the intracellular and extracellular distributions of reduced chromium phases in bioreduced samples. After complete reduction of Cr6+ (39 hrs. of incubation), a 5 mL cell-chromium suspension was taken from the 0.4 mM Cr6+ bioreduction experiment and centrifuged at 5000 g for 6 min. The resulting cell pellet was washed three times with anaerobic DI water inside a glove box to remove any excess salts. Ultrathin sections (∼50–60 nm) of the sample material were obtained by following the procedure described previously (Dong et al., 2003) followed by counterstaining by lead citrate. JEOL JEM-2100 LaB6 TEM with an accelerating voltage of 200 KeV fitted with STEM/EDS was employed for high resolution imaging and for compositional analysis. To identify the reduced chromium mineral, selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern was acquired with a Gatan Orius SC200D camera.

2.4.6 XANES

XANES spectroscopy was used as a fingerprint to identify the average oxidation state of chromium in the supernatant before and after bioreduction. Because X-ray absorption spectroscopy requires a higher concentration of chromium than the microscopy studies above, a separate set of bioreduction experiments was set up with 5 times higher cell concentration (∼5 × 109 cells/mL) than that used in a typical bioreduction experiment at 1 mM Cr6+ concentration. Cultures were sampled at various time points, with each sample centrifuged and the supernatant loaded into lucite cuvettes with 6 µm polypropylene windows and frozen rapidly in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray absorption spectra were measured at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), beamline X3A, with a Si(111) double crystal monochromator; harmonic rejection was accomplished using a Ni focusing mirror. Fluorescence excitation spectra for all samples were measured with a 13-element solid-state Ge detector array. Samples were held at ∼ 15 K in a Displex cryostat during XAS measurements. The transmission mode XANES spectra of solid chromium chloride (CrCl3) and solid potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) were measured as reference standards for Cr3+ and Cr6+, respectively. X-ray energies were calibrated by reference to the absorption spectrum of a chromium metal foil, measured concurrently. All of the data shown represent the average of 3 scans, measured using 10 eV steps in the pre-edge region (1 s integration time), 0.3 eV steps in the edge region (5950 – 6100 eV; 2 s), and 5 eV steps in the EXAFS region (6100 – 6500 eV; 1 s). Data reduction and normalization were accomplished using SixPack (http://home.comcast.net/~sam_webb/sixpack.html).

3. RESULTS

3.1.Toxicity test

At 0.2 mM Cr6+ concentration, there was a substantial amount of cell growth over a 115 day period, but higher concentrations of Cr6+ inhibited cell growth (Fig. 1). Likewise, cell viability was dependent on Cr6+ concentration. When the initial Cr6+ concentration was low (0.2 mM), the live/dead cell ratio initially declined, but at 20 hrs this ratio started to increase (Fig. 1). In contrast, higher concentrations of Cr6+, such as 1, 3, and 5 mM, led to a gradual decline of the live/dead cell ratio over time.

Figure 1.

Changes in total cell concentration (open symbols) and the live/dead cell ratio (filled symbols) of M. thermautotrophicus upon exposure to various Cr+6 concentrations. At 0.2 mM Cr6+ concentration, total cell concentration increased over time, but cell viability initially declined followed by a quick recovery after Cr6+ was reduced. At higher Cr6+ concentrations, total cell concentration remained nearly constant but cells continued to die over time.

3.2.Cr6+ bioreduction by M. thermautotrophicus

Negligible amounts of Cr6+ reduction were observed in either no-cell or heat-killed controls (Fig. 2). However, in the presence of M. thermautotrophicus, 0.2 and 0.4 mM Cr6+ was completely reduced with rates of 13.3 and 10.3 µM h−1, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1). At higher Cr6+ concentrations (i.e., 1 mM, 3 mM and 5 mM), the bioreduction rates decreased to 4.2, 3.7 and 1.9 µM h−1 with the lower reduction extents of 43.6%, 13.0% and 3.7% respectively. In a separate set of bioreduction experiment conducted for XANES analysis, 1 mM of Cr6+ was completely reduced in ∼130 hrs when the cell concentration was increased to ∼5 × 109 cells/mL, suggesting that it was the Cr6+/cell ratio that was responsible for cell toxicity and Cr6+ reduction. The amount of Cr6+ reduction per cell in this case was similar to that for the 0.2 mM Cr6+ bioreduction experiment. The mass balance calculation, based on the ICP-OES measurements of chromium in the supernatants and dissolved precipitates showed that, at 0.2 and 0.4 mM initial concentrations of Cr6+, about 30% of the reduced Cr3+ (e.g., 0.05 mM and 0.11 mM) was in an aqueous form (Fig. 3). At 1 mM initial concentration of Cr6+, about 26% the reduced Cr3+ (0.11 mM) was aqueous, whereas in case of 3 and 5 mM initial concentrations of Cr6+, about 85 and 65% of the reduced Cr3+ (0.33 and 0.04 mM) was in aqueous form even though the bioreduction extents were very low at these concentrations.

Figure 2.

Bioreduction of Cr6+ by M. thermautotrophicus at various concentrations. 100% reduction was achieved at Cr6+ concentrations of 0.2 and 0.4 mM L−1, but bioreduction was incomplete at 1, 3 and 5 mM Cr6+ concentrations. No-cell and heat-killed controls do not show any significant Cr6+ reduction in comparison with bioreduction.

Table 1.

Rates and extents of Cr6+ reduction by M. thermautotrophicus at various initial Cr6+ concentrations.

| Initial Cr6+ Conc. (mM) |

Rate of bioreduction (µM h-1) |

Extent of bioreduction (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.17 | 13.3 | 100 |

| 0.40 | 10.3 | 100 |

| 0.98 | 4.2 | 43.6 |

| 2.90 | 3.7 | 12.9 |

| 5.05 | 1.9 | 3.7 |

Figure 3.

Different fractions of chromium recovered after 100 hrs of incubation at various Cr6+ concentrations. At 0.2 and 0.4 mM Cr6+ concentrations, about 30% of the reduced chromium (0.05 and 0.11 mM) was in aqueous form whereas, at 1 mM Cr6+ concentration, only about 26% of the reduced chromium (0.11 mM) was aqueous. At the Cr6+ concentrations of 3 and 5 mM, about 85 and 65% of the reduced Cr3+ (0.33 and 0.04 mM, respectively) was in aqueous form even though the reduction extents were very low at these concentrations.

3.3. Protein assay measurement

Similar to the toxicity test, high Cr6+ concentrations (1, 3 and 5 mM) inhibited the growth of M. thermautotrophicus at both low (4.40 × 106 cells/mL, Fig. 4a) and high (1.56 × 109 cells/mL, Fig. 4b) cell concentrations. Total protein concentration in the 0.2 mM Cr6+ treatment showed a minor decrease at the beginning when Cr6+ reduction was active (0−13 hrs), but started to increase after Cr6+ was completely reduced (Fig. 4 inset). However, at 1, 3, and 5 mM, total protein concentrations monotonically decreased from the beginning to the end, suggesting a toxic nature of Cr6+ to the cells.

Figure 4.

Time course changes of total protein concentration of M. thermautotrophicus upon exposure to various Cr6+ concentrations at 1.56 × 109 cells/mL (a) and 4.40 × 106 cells/mL (b) concentrations. Cells were able to recover after 0.2 mM Cr6+ was completely reduced. At higher Cr6+ concentrations, total protein concentration declined suggesting that cells died over time.

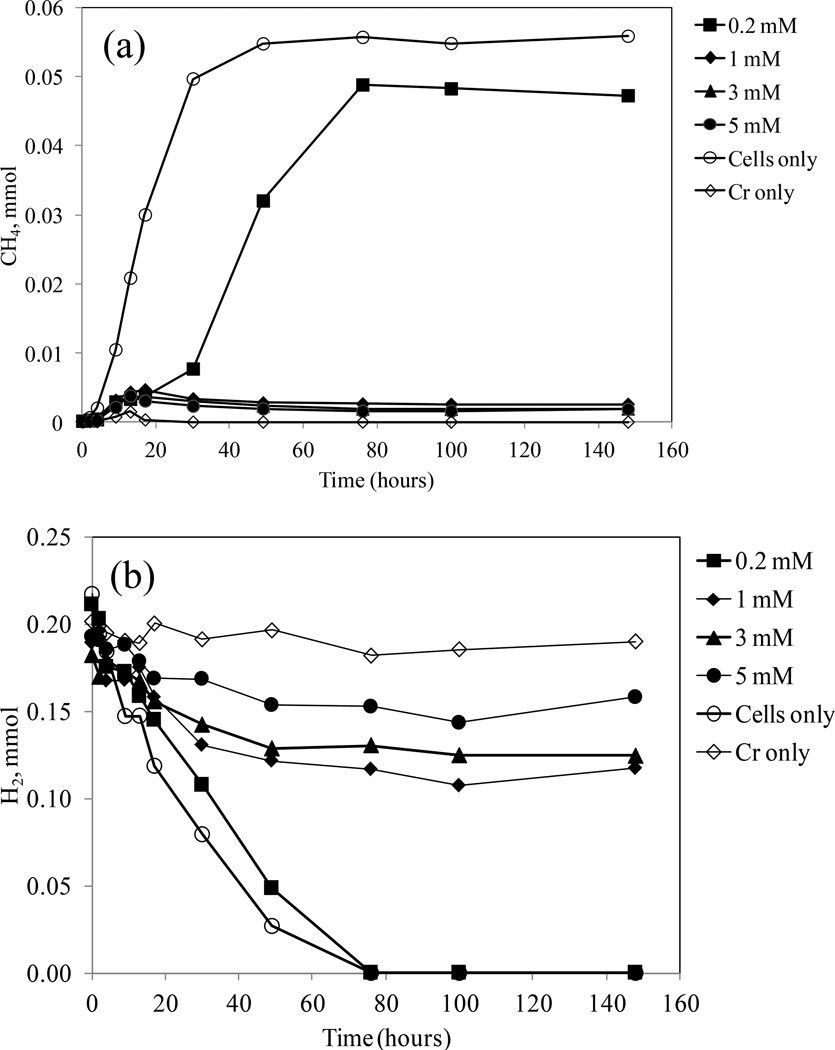

3.4.Methane and hydrogen measurement

In the absence of chromium, a significant amount of methane was produced (Fig. 5a). However, addition of various concentrations of Cr6+ inhibited methanogenesis to different extents. For the treatment without chromium, consumption of H2 and production of CH4 showed an expected stoichiometric ratio of 4:1, where the amount of H2 consumption was ∼0.21 mmol and the methane production was ∼0.055 mmol (Fig. 5a, b) following the reaction below,

| Eq. 1 |

However, when 0.2 mM Cr6+ concentration was added to the system, the amount of H2 consumption was ∼0.21 mmol, with a corresponding ∼0.048 mmol of methane was produced. This system also had a 0.174 mM (0.0069 mmol) reduction of Cr6+ (Fig. 5a, b; Table 2). According to the 4:1 stoichiometric ratio of H2 and CH4, the amount of H2 required to produce 0.048 mmol CH4 should be ∼0.19 mmol, leaving ∼0.02 mmol H2 for Cr6+ bioreduction. So the ratio of H2 consumption and Cr6+ bioreduction was 0.02:0.007, very close to the theoretical ratio of 3:1 according to the following equation,

| Eq. 2 |

The stoichiometric relationship between H2 consumption and Cr6+ reduction was also similar for the other Cr6+ concentrations (Table 2). Therefore, every mole of Cr+6 required 3 moles of H2 to produce 2 moles of Cr3+ during this bioreduction experiment.

Figure 5.

Time course methane production (a) and hydrogen consumption (b) by M. thermautotrophicus with or without Cr6+ at various concentrations. Presence of chromium in the experiments inhibited methanogenesis.

Table 2.

H2 consumption and the corresponding reduction of Cr6+ at various initial concentrations.

| Initial Cr6+ conc. (mM) |

Cr6+ reduced (Initial- final) (mM) |

Cr6+ reduced (Initial- final) (mmol) |

Total CH4 produced (mmol) |

Stoichiome tric consumption of H2 (mmol) |

Actual H2 consumption (mmol) |

Amount of H2 used to reduce Cr6+ reduction (mmol) |

Ratio of H2 to Cr6+ reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.174 | 0.174 | 0.0069 | 0.048 | 0.192 | 0.212 | 0.020 | 1:2.9 |

| 0.98 | 0.428 | 0.0172 | 0.003 | 0.012 | 0.072 | 0.060 | 1:3.4 |

| 2.90 | 0.375 | 0.0148 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.060 | 0.052 | 1:3.5 |

| 5.05 | 0.190 | 0.0076 | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.030 | 0.022 | 1:2.8 |

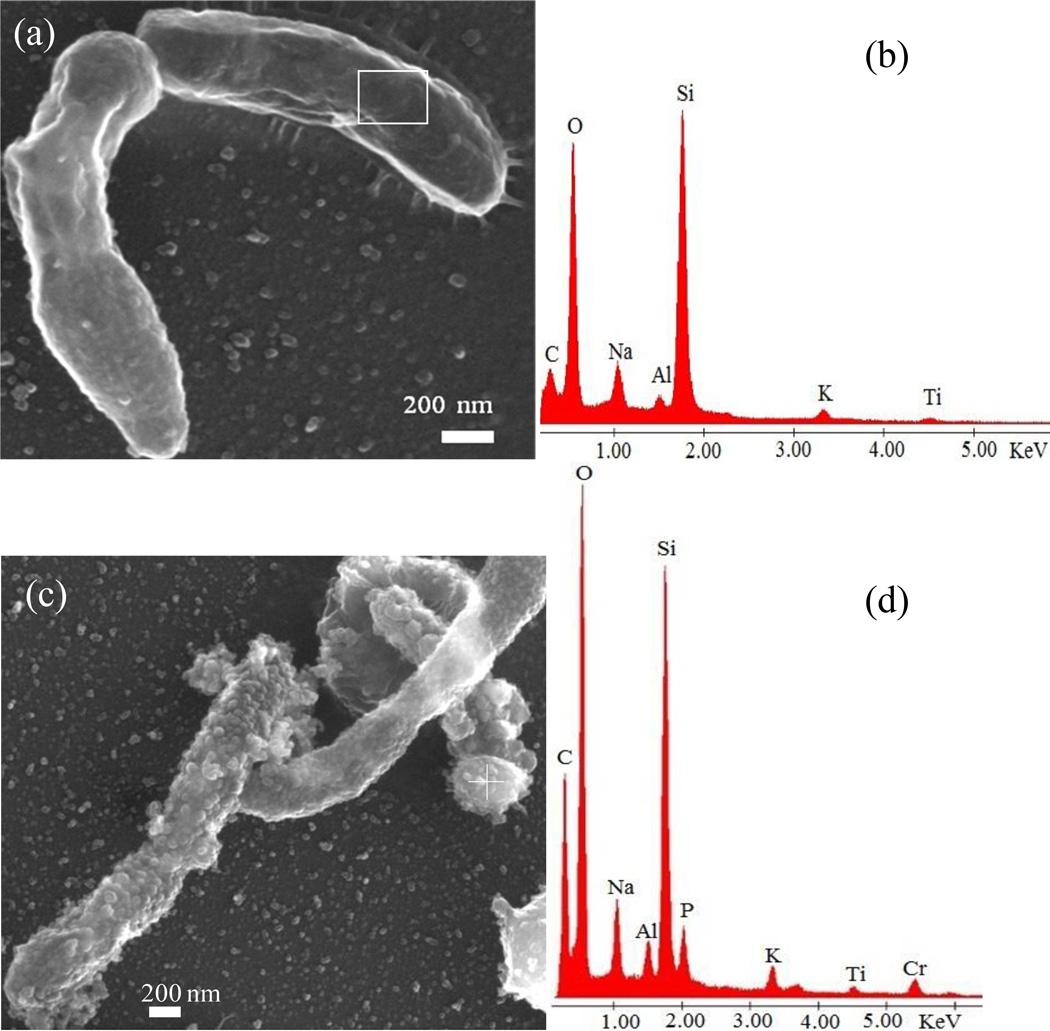

3.5. SEM and TEM observations

Because the 0.4, 1, and 3 mM experiments gave rise to the same results, the 0.4 mM experimental data were presented here as a representative example. SEM observations revealed that cells not exposed to chromium had a smooth surface (Fig. 6a), and EDS analysis did not show any Cr (Fig. 6b). In comparison, M. thermautotrophicus cells exhibited a rough surface upon exposure to Cr6+ (Fig. 6c). Those particles on the surface of cells and also away from cells were confirmed as chromium precipitates by energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analyses (Fig. 6d). In the EDS spectra for both non-exposed and exposed cell surfaces, Si, Al, Na, P, and K appeared to be derived from the underlying glass substrate, because these elements were also detected from the glass surface without any sample. SEM elemental mapping showed a correspondence between C and Cr, but Si, Al, and K were depleted (Fig. 7), suggesting that Cr was associated with cell biomass.

Figure 6.

SEM images with corresponding EDS. M. thermautotrophicus cells incubated without chromium (a) and the corresponding EDS from the squared area (b). No surface roughness was observed in control cells. A M. thermautotrophicus cell after exposure of 0.4 mM Cr6+ showing a rough surface (c) and EDS from the ‘+’ area of (c) showing a chromium peak at 5.4 KeV. Other elements are from the supporting glass substrate as they are also present without cells.

Figure 7.

SEM elemental maps from the 0.4 Cr6+ experimental sample showing the distribution of different elements over the surface of a M. thermautotrophicus cell. There was depletion of Si, Al, and K underneath the cell. C is from the cellular material and Cr is nearly uniformly distributed outside and inside the cell. Slight difference in the size of the image and elemental maps is due to image distortion caused by electron beam on the cell over the time period of mapping.

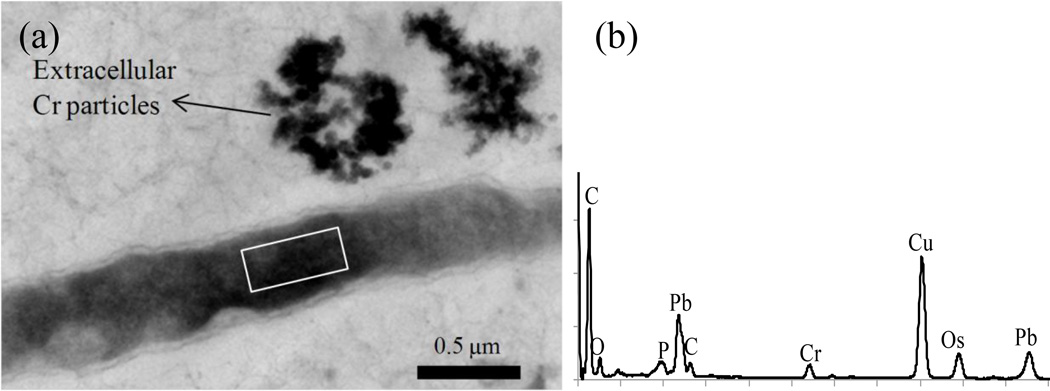

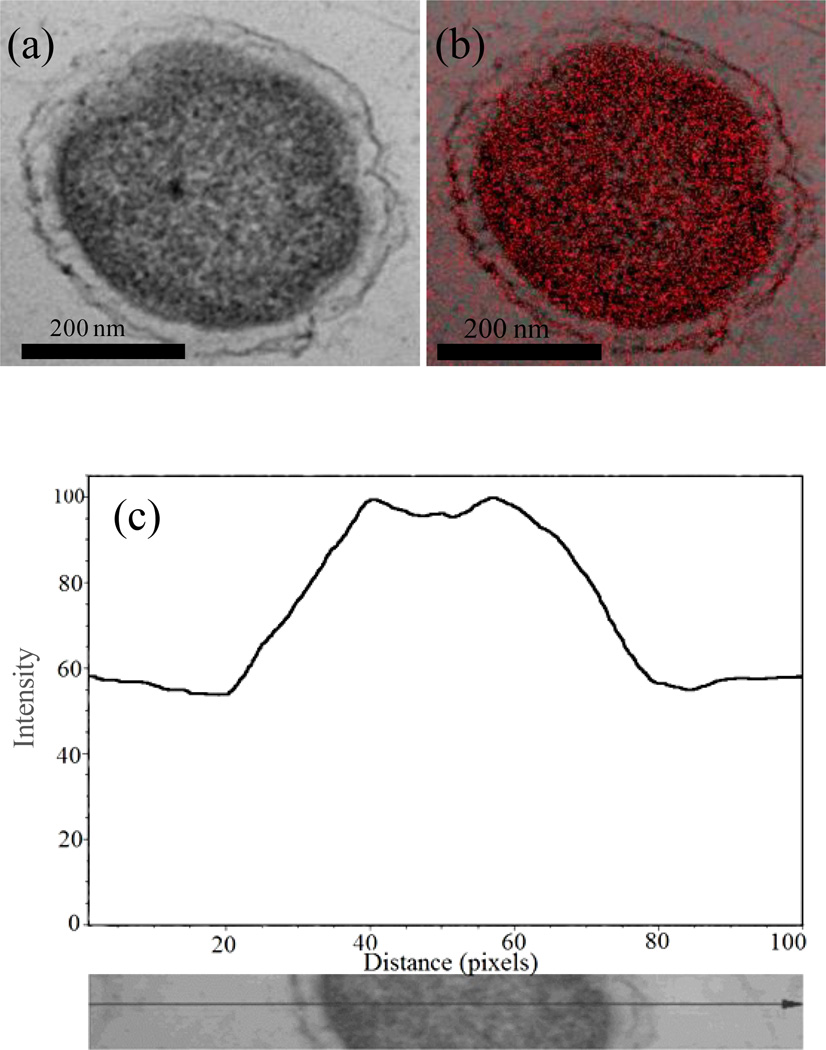

TEM/STEM/EDS investigations showed the presence of reduced chromium precipitates both outside (Fig. 8) and inside (Fig. 9) cells. When chromium precipitates were inside the cell, there appeared to be a clear zonation near the surface (Figs. 9). A SEM line scan showed chromium precipitation inside the cell as represented by higher signal intensity within the cell than outside (Fig. 9c). These precipitates were later identified as chromium hydroxide particles by SAED with characteristic d-spacing of 0.46 nm (Fig. 10). Other lines of chromium hydroxide were absent, likely due to their low intensities and diffuse nature.

Figure 8.

TEM image of M. thermautotrophicus after Cr+6 exposure (0.4 mM conc.). The image shows a clear distribution of chromium particles inside and outside of the cell (a), The EDS spectrum (b) corresponds to the rectangular area in Figure a. C and Cu peaks are from carbon coated TEM Cu grids. Os peak is from Os tetroxide used as a secondary fixative and Pb peaks are from Pb citrate used to stain the sample. P, Ca, and Cl peaks are from the components in the growth medium that may have remained even after washing.

Figure 9.

STEM image of a M. thermautotrophicus cell (a), elemental map showing chromium distribution inside the cell (b). A line scan showing chromium distribution inside the cell (c). The Y-axis is signal intensity and the X-axis is a measure of distance.

Figure 10.

TEM image of chromium hydroxide precipitates formed after complete reduction of 0.4 mM Cr6+ by M. thermautotrophicus. (a) Chromium hydroxide precipitates; (b) The corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern for the area (black arrow) shown in (a) showing characteristic d-spacing of 0.46 nm, one of the 3-line chromium hydroxide. The other two lines were not observed, likely due to low intensity.

3.6. XANES

Reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+ by M. thermautotrophicus was confirmed using XANES. A comparison of the initial time point (blue) to the final “complete” time point (red) reveals that there is a clear shift toward lower energy and concomitant sharpening of the white line absorption (∼ 6005 eV), and a concurrent abolition of the 1s→3d bound-state transition (∼ 5993 eV; Fig. 11). Examination of a series of time points in between shows that the changes in 1s→3d intensity are monotonic, almost linearly dependent on exposure time of Cr6+ to cells (inset to Fig. 11). The shifts in the white line are more complex, but generally follow the same trend. When compared to the model data, it is clear that these changes are indicative of reduction of Cr6+, most likely to Cr3+, consistent with the chemical data in Fig. 2. For Cr6+ in K2Cr2O7, this peak is sharp and prominent, as there are no 3d electrons present and these molecular orbitals are heavily mixed with metal ion 4p orbitals in forming the Cr=O bonds, resulting in high transition probability. In contrast, the Cr3+ in CrCl3 is a nearly-octahedral d3 ion, with centrosymmetry that significantly lowers the probability of the 1s→3d transition, and this peak is all but absent for this compound (Fig. 11). The bioreduction data show trends that are consistent with these two extremes. The remaining differences between the two sets of samples can likely be attributed to sample phase, as the two standard samples were measured in the solid state, while the bioreduction samples were frozen solutions.

Figure 11.

Cr K-edge XANES spectra at different times during Cr6+ bioreduction (blue = initial; red = final). The 1s to 3d transition becomes progressively weaker, indicating reduction of Cr6+. Inset: Intensity of 1s to 3d transition at 5993 eV vs. incubation time in hours.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1 Reduction kinetics of Cr6+ to Cr3+ by M. thermautotrophicus

In our bioreduction experiment using various concentrations of Cr6+, bioreduction rates and extents of Cr6+ by M. thermautotrophicus cells varied with the initial Cr6+ concentration, with higher rates and extents at lower Cr6+ concentrations (Table 1). Other thermophilic microorganisms have been previously reported to reduce Cr6+ with various rates and extents. For example, an anaerobic hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrobaculum islandicum completely reduced 0.45 mM Cr6+ at 100°C with a rate of 212.5 µM h−1 when H2 was supplied as an electron donor (Kashefi and Lovely, 2000). Thermus scotodoctus SA-01 isolated from a South African Gold mine coupled reduction of 0.1 mM Cr6+ (rate of 5 µM h−1) with oxidation of lactate at 65°C (Kieft et al., 1999). A moderately thermophilic bacterium Bacillus thermoamylovorans SKC1 completely reduced 0.6, 1.8, and 3 mM Cr6+ at 50°C with a rate ranging from 6 to 17.8 µM h−1 (Slobodkina et al., 2007). Likewise, a thermophilic anaerobic fermenter, Thermoanaerobacter ethanolicus, enhanced reduction rate of Cr6+ (0.7 mM) by 2–4 times relative to abiotic controls (e.g., 17 vs. 3.7 µM h−1, Zhang et al., 1996) at 55°C. Our measured Cr6+ bioreduction rates (1.9–13.3 µM h−1) and extents (3.7–100%) by M. thermautotrophicus fell within the range of those observed by various thermophilic bacteria and archaea. The high rate of Cr6+ bioreduction by P. islandicum could possibly be due to the effect of high temperature (100°C). The positive effect of high temperature on bioreduction kinetics has been observed previously, where the rates of structural Fe3+ reduction in clay minerals by thermophilic methanogens were higher than those by mesophilic methanogens (Zhang et al., 2012, 2013).

Among the mesophilic microorganisms capable of reducing Cr6+, Ochrobactrum anthropi was reported to have a very high reduction rate of 320 µM h−1 with a 100% extent of reduction, even at an initial Cr6+ concentration of as high as 7.7 mM (Li et al., 2008). In comparison, Cr6+ bioreduction rates and capacities of other mesophiles such as Cellulomonas sp. (Sani et al., 2002), sulfate-reducing bacteria (Cheung and Gu, 2003), Shewanella sp. (Lall and Mitchell, 2007), and Bacillus sp. (Masood and Malik, 2011) were only 2, 1, 25, and 38 µM h−1 when the initial Cr6+ concentrations were 0.2, 0.6, 0.5, and 2 mM, respectively. Similarly, E. Cloacae strain HO1 reduced 5 mM Cr6+ at the rate of 2 µM h−1 using sucrose as a carbon source (Rege et al., 1997). Although the exact rates of Cr6+ bioreduction depend on various experimental conditions and microbial physiology, in general thermophiles exhibit higher rates than mesophiles (with the exception of Ochrobactrum anthropi). These high rates make thermophilic methanogens an attractive agent for efficient bioremediation at high temperature chromium contaminated sites.

4.2. Reduction products

From a bioremediation standpoint, it is desirable to achieve a complete reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+ followed by precipitation of the reduced chromium. Based on our TEM/EDS-SAED data, the majority of the reduced chromium was in the form of chromium hydroxide or oxide. However, its positive identification could not be made because of its amorphous nature. The presence of a chromium hydroxide- or oxide-like phase has been documented previously in the bioreduction of Cr6+ by Flexivirga alba ST13T, based on a comparative analysis of XANES spectra of Cr(OH)3 and the Cr-precipitate (Sugiyama et al., 2012). Similarly, Cr2O3 nanoparticles were produced and adsorbed on the cell surface of S. oneidensis MR-1 during the bioreduction of Cr6+ and its chemical nature was confirmed by energy dispersive spectroscopy imaging and Raman spectroscopy (Wang et al., 2012).

Although Cr6+ was completely reduced to Cr3+ at low concentrations (<0.4 mM), our data showed that a certain fraction of reduced Cr3+ was in aqueous phase (∼30% for 0.2 and 0.4 mM Cr6+ concentrations, Fig. 3). This result is consistent with previous studies showing that a certain fraction of bioreduced chromium was in the form of soluble Cr3+-organic complexes (Puzon et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012). These water soluble Cr3+ complexes are known to coordinate with various functional groups including hydroxyl, carboxyl, amido and mercapto groups possibly derived from microbial cells (Cheng et al., 2010; Dogan et al., 2011 and Chen et al., 2012). Although, the formation of water soluble Cr3+-organic complexes is not desirable from a bioremediation perspective, the gradual conversion of organo-Cr3+ species into Cr(OH)3 has been reported before, but with a slow transformation rate (two years under certain experimental conditions, Cheng et al., 2012). Therefore, the organo-Cr3+ complexes might only be transient products produced during our Cr6+ bioreduction and over time they may be transformed to chromium hydroxide- or oxide.

4.3. Cr+6 reduction mechanisms by M. thermautotrophicus

SEM and TEM/STEM observations suggest that Cr6+ reduction by M. thermautotrophicus occurred both extra- and intra-cellularly (Figs. 6–9). This finding is similar to the previous results for Cr6+ reduction by Bacillus cereus (Chen et al., 2012), Ochrobactrum anthropi (Li et al., 2008), Shewanella oneidensis, MR-1 (Middleton et al., 2003), where both bacterial surfaces and intracellular regions were identified as the major sites for chromium reduction and immobilization. Biologically induced extracellular mineralization of soluble metal ions to insoluble metal precipitates has been previously described as an important electron transport mechanism for microorganisms to obtain energy (Nies, 1999; Frankel and Bazylinski, 2003; Kanmani et al., 2012; Lovely, 2013). Although, the majority of the mechanisms of extracellular reduction of Cr6+ by various microorganisms are explained in the presence of cytochromes (Belchik et al., 2011; Morais et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012; Viti et al., 2013; Ahemad, 2014), M. thermautotrophicus does not contain cytochromes or membrane-associated methanophenazine, which would function in electron transfer from H2 to the electron-accepting steps (Thauer et al., 2008; Kaster et al., 2011). Nevertheless, other electron carriers, such as ferredoxins and several protein coding sequences for ferredoxins, have been identified in the genomes of M. thermautotrophicus (Kaster et al., 2011). These carriers are known to participate in spontaneous redox reactions (Thauer et al., 2008; Kaster et al., 2011). Therefore, membrane associated extracellular reduction of Cr6+ by M. thermautotrophicus may have involved these ferredoxins-dependent reactions in the electron transport chain.

Intracellular reduction of metal ions involves transport of metal ions into the cell cytoplasm, and this process is mediated by membrane transport proteins (Chellapandi, 2011). Toxic metals have no uptake systems for them to enter the cells using channels designed for other ions and organic molecules. However, due to the structural similarity of chromate ions to SO42− ions, they can easily be transported across biological membrane via the sulfate transport system in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Cervantes and Campos-Garcia, 2007; Ramírez-Díaz et al., 2008). In the case of M. thermautotrophicus, it is predicted to have a large number of transport systems for inorganic solutes including dichromate ions, many of which have components related to the ABC family of ATP-dependent transporters (Smith et al., 1997). Once Cr6+ is transported into the cells, its reduction to Cr3+ could have taken place by certain proteins in M. thermautotrophicus that are similar (86%) to a known NADPH-dependent FMN reductase in Methanobacterium sp. (NCBI accession # YP_004518865). However, it has been documented that the subsequent intracellular reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+ could generate an oxidative stress and DNA damage due to the formation of transient Cr5+ species (Suzuki et al., 1992; Myers et al., 2000; Kalabegishvili et al., 2003; Viti et al., 2013), which may have accounted for the observed initial inhibition of cell growth at 0.2 mM Cr6+ or complete cell death at higher Cr6+ concentrations. Even so, the presence of superoxide dismutase, SOD (NP_275303) in the genome M. thermautotrophicus (Smith et al., 1997) suggests that this archaeon has a genetic potential to survive this oxidative stress, which would allow for cell recovery after Cr6+ was fully reduced to Cr3+ at 0.2 mM Cr6+ concentration (Figs. 1 and 4). This inhibition - recovery cycle, through these mechanisms, is similar to Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 regaining their viability after Cr6+ concentrations of 0.02 mM, 0.035 mM and 0.05 mM were reduced to below the detection limit (< 0.002 mM). It was hypothesized that the reduction of Cr6+ itself is a detoxification mechanism for MR-1 cells (Viamajala et al., 2004). However, a lower growth rate of S. oneidensis MR-1 observed even after the complete reduction of Cr6+ was considered to be associated with residual toxicity possibly from cellular and DNA damage, or due to retention of Cr3+ inside the cells (Viamajala et al., 2004). Similarly, in a Cr6+ reduction study by sulfate reducing bacteria (SRB), total protein concentration of active enrichment culture increased only after a significant reduction of Cr6+ occurred (after ∼144 hrs) (Cheung and Gu, 2003), suggesting a similar inhibition-recovery cycle.

In contrast, at higher Cr6+ concentrations, M. thermautotrophicus cells did not show any recovery (Figs. 1 & 4). This inability is likely due to the transport of high levels of Cr6+ ions into the cell and the consequent unrecoverable cytotoxic effects such as DNA damage, which could have been caused by hydroxyl radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated during the intracellular reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+. These hydroxyl radicals and ROS have been reported to trigger direct DNA alterations as well as other genotoxic effects to cells (Cervantes et al., 2001; Ramírez-Díaz et al., 2008; Kanmani et al., 2012). Therefore, the production of these toxic components may have been a major mechanism for cell mortality at high Cr6+ concentrations (>0.4 mM), which eventually could have negatively affected the rate and extent of Cr6+ reduction in our experiment.

Another hypothesis for the chromium toxicity may be related to the soluble Cr3+ complexes. During the Cr6+ reduction by Shewanella sp. MR-4, the soluble Cr3+ cation or hydroxyl complexes were hypothesized to be transported into the cytoplasm of MR-4 cells which binds nonspecifically to DNA and other cellular components, inhibiting transcription and possibly DNA replication (Bencheikh-Latmani et al., 2007).

4.4. Relationship between methanogenesis and Cr6+ bioreduction

Our observed inhibition of methanogenesis by Cr6+ reduction could be explained by the direct toxic effect of Cr6+ on M. thermautotrophicus. An alternative hypothesis could be the diversion of electron flow from CO2 to Cr6+. In the normal pathway of methanogenesis, hydrogenases in hydrogenotrophic methanogens can oxidize H2 to a proton by releasing two electrons, and these two electrons are utilized to reduce methyl-coenzyme M (CH3-S-CoM) to CH4 (Deppenmeier et al., 1999). However, it has been reported that, in the presence of bioavailable Fe3+, these electrons could be diverted to Fe3+ to reduce it to Fe2+ or other metal ions to their lower oxidation states (Bond and Lovley, 2002, Liu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013, 2014). Based on this, it can be hypothesized that, in this experiment, electrons from H2 could have diverted to Cr6+ instead of CO2 to make CH4. This electron diversion hypothesis is supported by the stoichiometric consumption of H2 to the production of Cr3+ (Fig. 5, Table 2, and Eq. 1, 2), implying that electrons used to reduce Cr6+ were derived from H2.

4.5. Implication for bioremediation

Although a number of high temperature chromium contaminated sites have been recognized worldwide, metal bioremediation studies using thermophiles are very limited (Kanmani et al., 2012; Lovely, 2013). Our results demonstrated the ability of M. thermautotrophicus to reduce Cr6+ to Cr3+ with various rates and extents depending on the initial Cr6+ concentrations. Considering the Cr6+ concentration of greater than 0.028 mM L−1 in groundwater, which is below the lowest concentration of Cr6+ utilized in this study (Dresel et al., 2008), and the recorded temperatures of as high as 70°C at depths of greater than 18 m at DOE’s Hanford Site in south-central Washington State (Agnew and Corbin, 1998), Cr6+ reduction and immobilization by thermophilic methanogen M. thermautotrophicus could be an important mechanism for bioremediation, especially beneath large storage tanks (Brookins, 1990; Cattant et al., 2008).

This detailed study not only expands the known microbial species that can biologically transform and immobilize soluble Cr6+ to insoluble chromium hydroxide or oxide, it also raises the possibility of injecting methanogens to high temperature subsurface environments such as subsurface radioactive waste disposal sites (Brookins, 1990), where heavy metals may be predominant forms of contaminants (Riley et al., 1992; Palmisano and Hazen, 2003; Cattant et al., 2008). In these environments, thermophilic methanogens could use hydrogen as electron donor in deep subsurface and inorganic carbon as carbon source (Pederson, 1996; Kotelnikova, 2002) to reduce heavy metals such as Cr6+. In doing so, thermophilic methanogens could potentially play a vital role in minimizing migration of these contaminants in the subsurface.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Thermophilic methanogen, M. thermautotrophicus was capable of reducing Cr6+ as a terminal electron acceptor at 65°C when coupled with oxidation of H2. This archaeon completely reduced 0.2 and 0.4 mM Cr6+ to Cr3+ both extra- and intracellularly. At higher Cr6+ concentrations, incomplete reduction occurred, possibly due to the toxic nature of chromium to this methanogen. The reduced chromium occurred predominantly in the form of hydroxide- or oxide-like, amorphous solid, with a certain fraction of soluble Cr3+. The observed inhibition of methanogenesis by Cr6+ reduction could be due to the chromium associated cytotoxic effects or diversion of electron flow from CO2 to Cr6+. Cr6+ reduction and immobilization by thermophilic methanogens could potentially be useful for the bioremediation purpose, especially in radioactive waste disposal sites, where temperature may be high and heavy metals may be predominant.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Subsurface Biogeochemical Research (SBR) Program, Office of Science (BER), U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) grant no. DE-SC0005333 to H.D. and by the U. S. National Science Foundation (CHE-1152755 to DLT). The authors are grateful to three anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the quality of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agnew SF, Corbin RA. Analysis of SX farm leak histories: historical leak model. Los Alamos, New Mexico: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M. Bacterial mechanisms for Cr(VI) resistance and reduction: an overview and recent advances. Folia Microbiol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s12223-014-0304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas RM, Philip J, editors. Bioremediation: Applied Microbial Solutions for Real-World Environmental Cleanup. Washington,D.C.: ASM Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barkay T, Schaefer J. Metal and radionuclide bioremediation: Issues, considerdations and potentials. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2001;4:318–323. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00210-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencheikh-Latmani R, Obraztsova A, Mackey MR, Ellisman MH, Tebo BM. Toxicity of Cr(III) to Shewanella sp. Strain MR-4 during Cr(VI) reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:214–220. doi: 10.1021/es0622655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop ME, Glasser P, Dong H, Arey B, Kovarik L. Reduction and immobilization of hexavalent chromium by Fe-bearing clay minerals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2014 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2014.02.040. [Google Scholar]

- Bond DR, Lovley DR. Reduction of Fe(III) oxide by methanogens in the presence and absence of extracellular quinones. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;4(2):115–124. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:48–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim H, Venkateswaran A, Kostandarithes HM, Fredrickson JK, Daly MJ. EngineeringDeinococcus geothermalisfor Bioremediation of High-Temperature Radioactive Waste Environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4575–4582. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4575-4582.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookins DG. Radionuclide behavior at the Oklo nuclear reactor, Gabon. Waste Management. 1990;10:285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Canfield DE, Kristensen E, Thamdrup B. Aquatic Geomicrobiology, Advances in Marine Biology. Vol. 48. Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattant F, Crusset D, Féron D. Corrosion issues in nuclear industry today. Materials today. 2008;11:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes C, Campos-Garcia J, Devars S, Gutierrez-Corona F, Loza-Tavera H, Torres-Guzman JC, Moreno-Sanchez R. Interactions of chromium with microorganisms and plants. Federation of European Microbiological Societies. 2001;25:335–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes C, Campos-Garcia J. Reduction and efflux of chromate by bacteria. Microbiology Monographs. 2007;6:408–417. [Google Scholar]

- Chellapandi P. In silico description of cobalt and nickel assimilation systems in the genomes of methanogens. Systems and Synthetic Biology. 2011;5:105–114. doi: 10.1007/s11693-011-9087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Huang Z, Cheng Y, Pan D, Pan X, Yu M, Pan Z, Lin Z, Guan X, Wu Z. Cr(VI) uptake mechanism of Bacillus cereus . Chemosphere. 2012;87:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Yan F, Huang F, Chu W, Pan D, Chen Z, Zheng J, Yu M, Lin Z, Wu Z. Bioremediation of Cr(VI) and immobilization as Cr(III) by Ochrobactrum anthropi . Environ. Sci. Tech. 2010;44:6357–6363. doi: 10.1021/es100198v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Holman H-Y, Lin Z. Remediation of chromium and uranium contamination by microbial activity. Elements. 2012;8:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung KH, Gu J-D. Reduction of chromate (CrO4 2−) by an enrichment consortium and an isolate of marine sulfate-reducing bacteria. Chemosphere. 2003;52:1523–1529. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00491-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codd R, Lay PA, Tsibakhashvili NY, Kalabegishvili TL, Murusidze IG, Holman HY. Chromium(V) complexes generated in Arthrobacter oxydans by simulation analysis of EPR spectra. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2006;100:1827–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daulton TL, Little B, Jones-Meehan J, Blom DA, Allard LF. Microbial reduction of chromium from the hexavalent to divalent state. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2007;71:556–565. [Google Scholar]

- Deppenmeier U, Lienard T, Gottschalk G. Novel reactions involved in energy conservation by methanogenic archaea. FEBS Letters. 1999;457:291–297. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrenko GN, Konovalova VV, Shum OA. Reduction of Cr(VI) by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas . Microbiology. 2003;72:327–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan NM, Kantar C, Gulcan S, Dodge CJ, Yilmaz BC, Mazmanci MA. Chromium (VI) bioremoval by Pseudomonas bacteria: Role of microbial exudates for natural attenuation and biotreatment of Cr(VI) contamination. Environ. Sci.Tech. 2011;45:2278–2285. doi: 10.1021/es102095t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Kostka JE, Kim J. Microscopic evidence for microbial dissolution of smectite. Clays Clay Minl. 2003;51:502–512. [Google Scholar]

- Dresel PE, Ainsworth CC, Qafoku NP, Liu C, McKinley JP, Ilton ES, Fruchter JS, Phillips JL. Geochemical Characterization of Chromate Contamination in the 100 Area Vadose Zone at the Hanford Site. The U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC05-76RL01830. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Frankel RB, Bazylinski DA. Biologically induced mineralization by bacteria. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2003;54:95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Gadd GM. Microbial influence on metal mobility and application for bioremediation. Geoderma. 2004;122:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Gadd GM. Metals, minerals and microbes: Geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology. 2010;156:609–643. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilov SN, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Slobodkin AI. Physiology of organotrophic and lithotrophic growth of the thermophilic iron-reducing bacteria Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens and Thermoanaerobacter siderophilus . Microbiology (English translation of Mikrobiologiia) 2003;72:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalabegishvili TL, Tsibakhashvili NY, Holman HN. Electron spin resonance study of chromium (V) formation and decomposition by basalt-inhabiting bacteria. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2003;37:4678–4684. doi: 10.1021/es0343510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmani P, Aravind J, Preston D. Remediation of chromium contaminants using bacteria. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. 2012;9:183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Kashefi K, Lovely DR. Reduction of Fe(III), Mn(IV), and toxic metal at 100°C by Pyrobaculum islandicum . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1050–1056. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.3.1050-1056.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaster A-K, Goenrich M, Seedorf H, Liesegang H, Wollherr A, Gottschalk G, Thauer RK. More Than 200 Genes Required for Methane Formation from H2 and CO2 and Energy Conservation Are Present in Methanothermobacter marburgensis and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus . Archaea. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/973848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenealy W, Zeikus JG. Influence of corrinoid antagonists on methanogen metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 1981;146:133–140. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.1.133-140.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft TL, Fredrickson JK, Gorby YA, Onstott TC, Kostandarithes HM, Bailey TJ, Kennedy DW, Li SW, Plymale AE, Spadoni CM, Gray MS. Dissimilatory reduction of Fe(III) and other electron acceptors by a thermus isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:1214–1221. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1214-1221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotelnikova S, Pederson K. Distribution and activity of methanogens and homoacetogens in deep granitic aquifers at Äspö Hard Rock Laboratory, Sweden. FEMS Microb. Ecol. 1998;26:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kotelnikova S, Pederson K. Evidence for methanogenic Archaea and homoacetogenic Bacteria in deep granitic rock aquifers. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1997;20:339–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lall R, Mitchell J. Metal reduction kinetics in Shewanella . Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2754–2759. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Pan D, Zheng J, Cheng Y, Xiaoyan M, Huang F, Lin Z. Microscopic investigations of the Cr(VI) uptake mechanism of living Ochrobactrum anthropi . Langmuir. 2008;24:9630–9635. doi: 10.1021/la801851h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Dong H, Bishop ME, Wang H, Agrawal A, Trischler S, Eberl DD, Xie S. Reduction of structural Fe(III) in nontronite by methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri . Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2011;75:1057–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Wang H, Dong H, Qui X, Dong X, Cravotta III CA. Mineral transformations associated with goethite reduction by Methanosarcina barkeri . Chem. Geol. 2011;288:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd JR. Microbial reduction of metals and radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003;27:411–425. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovely D. The Prokaryotes-Prokaryotic Physiology and Biochemistry. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2013. Dissimilatory Fe(III)- and Mn (IV)- Reducing Prokaryotes. [Google Scholar]

- Lovley DR. Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. In: Lovley DR, editor. Environmental Microbe-Metal Interactions. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2000. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lovely DR. Dissimilatory metal reduction. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 1993;47:263–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood F, Malik A. Hexavalent chromium reduction by Bacillus sp. Strain FM1 isolated from heavy-metal contaminated soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011;86:114–119. doi: 10.1007/s00128-010-0181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill L, McLean J, Edwards M, Parks J. State of the Science of Hexavalent Chromium in Drinking Water. Water Research Foundation. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Middleton SS, Latmani RB, Mackey MR, Ellisman MH, Tebo BM, Criddle CS. Cometabolism of Cr(VI) by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 produces cell-associated reduced chromium and inhibits growth. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2003;83:627–637. doi: 10.1002/bit.10725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais PV, Branco R, Francisco R. Chromium resistance strategies and toxicity: what makes Ochrobactrum tritici 5bv11 a strain highly resistant. Biometals. 2012;24:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9446-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer WE, Engineers T. Chemistry, Geochemistry, and Geology of Chromium and Chromium Compounds. CRC press; 2004. ISBN 1-56670-608-4. [Google Scholar]

- Myers CR, Carstens BP, Antholine WE, Myers JM. Chromium(VI) reductase activity is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000;88:98–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nies DH. Microbial heavy-metal resistance. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999;51:730–750. doi: 10.1007/s002530051457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmisano A, Hazen T. Bioremediation of metals and radionuclides: What it is and how it works. (2nd edition) 2003 PBD: 30 Sep 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parker DL, Borer P, Bernier-Latmani R. The response of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 to Cr(III) toxicity differs from that of Cr(VI) Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzon GJ, Roberts AG, Kramer DM, Xun L. Formation of soluble organo-chromium(III) complexes after chromate reduction in presence of cellular organics. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2005;39:2811–2817. doi: 10.1021/es048967g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Diaz MI, Diaz-Perez C, Vargas E, Riveros-Rosas H, Campos-Garcia J, Cervantes C. Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to chromium compounds. Biometals. 2008;21:321–332. doi: 10.1007/s10534-007-9121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings DE, Dew D, Du Plessis C. Biomineralization of metal-containing ores and concentrates. Trends Biotechnol. 2003;21:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rege MA, Petersen JN, Johnstone DL, Turick CE, Yonge DR, Apel WA. Bacterial reduction of hexavalent chromium by Enterobacter cloacae strain HO1 grown on sucrose. Biotechnology Letters. 1997;19:691–694. [Google Scholar]

- Riley RG, Zachara JM, Wobber FJ. Chemical Contaminants on DOE Lands and Selection of Contaminant Mixtures for Subsurface Science Research. Washington, DC: US Department of Energy, Office of Energy Research, Subsurface Science Program; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sani RK, Peyton BM, Smith WA, Apel WA, Peterson JN. Dissimilatory reduction of Cr(VI), Fe(III), and U(VI) by Cellulomonas isolates. App. Microbiol. Biotech. 2002;60:192–199. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayan T, Littlechild J, Kawarabayasi Y. Thermophilic microbes in environmental and industrial biotechnology: Biotechnology of thermophiles. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenbach RP, Gschwend PM, Imboden DM. Environmental Organic Chemistry, Illustrative Examples, Problems, and Case Studies. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodkin A, Reysenbach A-L, Strutz N, Dreier M, Wiegel J. Thermoterrabacterium ferrireducens gen. nov., sp. nov., a Thermophilic anaerobic dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacterium from a continental hot spring. Intl. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997;47:541–547. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobodkin AI. Thermophilic microbial metal reduction. Microbiology. 2005;74:501–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slobodkina GB, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Slobodkin AI. Reduction of chromate, selenite, tellurite, and iron (III) by the moderately thermophilic bacterium Bacillus thermoamylovorans SKC1. Microbiology. 2007;76:530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DR, Doucette-Stamm LA, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Reeve JN. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, deltaH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Sugito H, Mamiya K, Suzuki Y, Ando K, Ohnuki T. Hexavalent chromium reduction by an actinobacterium Flexibirga alba ST13T in the family Dermacoccaceae . J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2012;113:367–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Miyata N, Horitsu H, Kawai K, Takamizawa K, Tai Y, Okazaki M. NAD(P)H-Dependent Chromium(VI) Reductase of Pseudomonas ambigua G-1: a Cr(VI) intermediate is formed during the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:5340–5345. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5340-5345.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thauer RK, Kaster AK, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urone PF. Stability of colorimetric reagent for chromium, S-diphenylcarbazide in various solvents. Anal. Chem. 1955;27:1354–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas M, Kashefi K, Blunt-Harris EL, Lovley DR. Microbiological evidence for Fe(III) reduction on early Earth. Nature. 1998;395:65–67. doi: 10.1038/25720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viamajala S, Peyton BM, Sani RK, Apel WA, Peterson JN. Toxic effects of chromium(VI) on anaerobic and aerobic growth of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Biotechnol. Progr. 2004;20:87–95. doi: 10.1021/bp034131q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viti C, Marchi E, Decorosi F, Giovannetti L. Molecular mechanisms of Cr(VI) resistance in bacteria and fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Francis AJ. Evaluation of Microbial Activity for Long-Term Performance Assessments of Deep Geologic Nuclear Waste Repositories. Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences. 2005;6:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sevinc PC, Belchik SM, Fredrickson J, Shi L, Lu HP. Single-cell imaging and spectroscopic analyses of Cr(VI) reduction on the surface of bacterial cells. Langmuir. 2012;29:950–956. doi: 10.1021/la303779y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavarzina DG, Sokolova TG, Tourova TV, Chernyh NA, Kostrikina NA, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA. Thermincola ferriacetica sp. nov., a new anaerobic, thermophilic, facultatively chemolithoautotrophic bacterium capable of dissimilatory Fe(III) reduction. Extremophiles. 2007;11:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00792-006-0004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehnder AJB, Wuhermann K. Physiology of a Methanobacterium strain AZ. Arch. Microbiol. 1977;111:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Liu S, Logan J, Mazumder R, Phelps TJ. Enhancement of Fe(III), Co(III), and Cr(VI) reduction at elevated temperatures and by a thermophilic bacterium. Appl. Biochem. Biotech. 1996;57/58:923–932. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Dong H, Liu D, Fisher TB, Wang S, Hunag L. Microbial reduction of Fe(III) in illite-smectite minerals by methanogen Methanosarcina mazei . Chem. Geol. 2012;292–293:35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Dong H, Liu D, Agrawal A. Microbial reduction of Fe(III) in smectite minerals by thermophilic methanogen Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus . Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2013;106:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Dong H, Zhao L, McCarrick R, Agrawal A. Microbial reduction and precipitation of vanadium by mesophilic and thermophilic methanognes. Chem. Geol. 2014;370:29–39. [Google Scholar]