Abstract

Aims

The original Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) Axis I diagnostic algorithms have been demonstrated to be reliable. However, the Validation Project determined that the RDC/TMD Axis I validity was below the target sensitivity of ≥ 0.70 and specificity of ≥ 0.95.

Consequently, these empirical results supported the development of revised RDC/TMD Axis I diagnostic algorithms that were subsequently demonstrated to be valid for the most common pain-related TMD and for one temporomandibular joint (TMJ) intra-articular disorder. The original RDC/TMD Axis II instruments were shown to be both reliable and valid. Working from these findings and revisions, two international consensus workshops were convened, from which recommendations were obtained for the finalization of new Axis I diagnostic algorithms and new Axis II instruments.

Methods

Through a series of workshops and symposia, a panel of clinical and basic science pain experts modified the revised RDC/TMD Axis I algorithms by using comprehensive searches of published TMD diagnostic literature followed by review and consensus via a formal structured process. The panel's recommendations for further revision of the Axis I diagnostic algorithms were assessed for validity by using the Validation Project's data set, and for reliability by using newly collected data from the ongoing TMJ Impact Project—the follow-up study to the Validation Project. New Axis II instruments were identified through a comprehensive search of the literature providing valid instruments that, relative to the RDC/TMD, are shorter in length, are available in the public domain, and currently are being used in medical settings.

Results

The newly recommended Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) Axis I protocol includes both a valid screener for detecting any pain-related TMD as well as valid diagnostic criteria for differentiating the most common pain-related TMD (sensitivity ≥ 0.86, specificity ≥ 0.98) and for one intra-articular disorder (sensitivity of 0.80 and specificity of 0.97). Diagnostic criteria for other common intra-articular disorders lack adequate validity for clinical diagnoses but can be used for screening purposes. Inter-examiner reliability for the clinical assessment associated with the validated DC/TMD criteria for pain-related TMD is excellent (kappa ≥ 0.85). Finally, a comprehensive classification system that includes both the common and less common TMD is also presented. The Axis II protocol retains selected original RDC/TMD screening instruments augmented with new instruments to assess jaw function as well as behavioral and additional psychosocial factors. The Axis II protocol is divided into screening and comprehensive self-report instrument sets. The screening instruments’ 41 questions assess pain intensity, pain-related disability, psychological distress, jaw functional limitations, and parafunctional behaviors, and a pain drawing is used to assess locations of pain. The comprehensive instruments, composed of 81 questions, assess in further detail jaw functional limitations and psychological distress as well as additional constructs of anxiety and presence of comorbid pain conditions.

Conclusion

The recommended evidence-based new DC/TMD protocol is appropriate for use in both clinical and research settings. More comprehensive instruments augment short and simple screening instruments for Axis I and Axis II. These validated instruments allow for identification of patients with a range of simple to complex TMD presentations.

Temporomandibular disorders (TMD) are a significant public health problem affecting approximately 5% to 12% of the population.1 TMD is the second most common musculoskeletal condition (after chronic low back pain) resulting in pain and disability.1 Pain-related TMD can impact the individual's daily activities, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life. Overall, the annual TMD management cost in the USA, not including imaging, has doubled in the last decade to $4 billion.1

Patients often seek consultation with dentists for their TMD, especially for pain-related TMD. Diagnostic criteria for TMD with simple, clear, reliable, and valid operational definitions for the history, examination, and imaging procedures are needed to render physical diagnoses in both clinical and research settings. In addition, biobehavioral assessment of pain-related behavior and psychosocial functioning—an essential part of the diagnostic process—is required and provides the minimal information whereby one can determine whether the patient's pain disorder, especially when chronic, warrants further multidisciplinary assessment. Taken together, a new dual-axis Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (DC/TMD) will provide evidence-based criteria for the clinician to use when assessing patients, and will facilitate communication regarding consultations, referrals, and prognosis.2

The research community benefits from the ability to use well-defined and clinically relevant characteristics associated with the phenotype in order to facilitate more generalizable research. When clinicians and researchers use the same criteria, taxonomy, and nomenclature, then clinical questions and experience can be more easily transferred into relevant research questions, and research findings are more accessible to clinicians to better diagnose and manage their patients. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD) have been the most widely employed diagnostic protocol for TMD research since its publication in 1992.3 This classification system was based on the biopsychosocial model of pain4 that included an Axis I physical assessment, using reliable and well-operationalized diagnostic criteria, and an Axis II assessment of psychosocial status and pain-related disability. The intent was to simultaneously provide a physical diagnosis and identify other relevant characteristics of the patient that could influence the expression and thus management of their TMD. Indeed, the longer the pain persists, the greater the potential for emergence and amplification of cognitive, psychosocial, and behavioral risk factors, with resultant enhanced pain sensitivity, greater likelihood of additional pain persistence, and reduced probability of success from standard treatments.5

The RDC/TMD (1992) was intended to be only a first step toward improved TMD classification, and the authors stated the need for future investigation of the accuracy of the Axis I diagnostic algorithms in terms of reliability and criterion validity—the latter involving the use of credible reference standard diagnoses. Also recommended was further assessment of the clinical utility of the Axis II instruments. The original RDC/TMD Axis I physical diagnoses have content validity based on the critical review by experts of the published diagnostic approach in use at that time and were tested using population-based epidemiologic data.6 Subsequently, a multicenter study showed that, for the most common TMD, the original RDC/TMD diagnoses exhibited sufficient reliability for clinical use.7 While the validity of the individual RDC/TMD diagnoses has been extensively investigated, assessment of the criterion validity for the complete spectrum of RDC/TMD diagnoses had been absent until recently.8

For the original RDC/TMD Axis II instruments, good evidence for their reliability and validity for measuring psychosocial status and pain-related disability already existed when the classification system was published.9–13 Subsequently, a variety of studies have demonstrated the significance and utility of the original RDC/TMD biobehavioral measures in such areas as predicting outcomes of clinical trials, escalation from acute to chronic pain, and experimental laboratory settings.14–20

Other studies have shown that the original RDC/TMD biobehavioral measures are incomplete in terms of prediction of disease course.21–23 The overall utility of the biobehavioral measures in routine clinical settings has, however, yet to be demonstrated, in part because most studies have to date focused on Axis I diagnoses rather than Axis II biobehavioral factors.24

The aims of this article are to present the evidence-based new Axis I and Axis II DC/TMD to be used in both clinical and research settings, as well as present the processes related to their development.

Materials and Methods

The RDC/TMD (Axis I and Axis II) was a model system when it was published in 1992, but the authors recognized that it was only a beginning and that further research was needed to improve its validity and clinical utility. Table 1 summarizes the subsequent major steps from the RDC/TMD to the new DC/TMD. Specifically, in 2001, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in the USA, recognizing the need to rigorously assess the diagnostic accuracy of the dual-axis RDC/TMD, funded the multisite Validation Project that resulted in a dataset of 705 participants who were classified, based on reference standard diagnoses, into 614 TMD cases and 91 controls.25 A description of the study methods as well as the demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample are available.25–27 Reference standard diagnoses were established by consensus between two TMD and orofacial pain experts at each of three study sites using a comprehensive history, physical examination, and imaging studies (panoramic radiograph, bilateral temporomandibular joint [TMJ] magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and computed tomography [CT]). Acceptable validity was defined a priori as sensitivity ≥ 0.70 and specificity ≥ 0.95.3 When the original RDC/TMD Axis I TMD diagnoses were compared to these reference standard diagnoses, the findings supported the need for revision of these Axis I TMD diagnostic algorithms to improve their diagnostic accuracy.8 The Validation Project subsequently developed and validated revised RDC/TMD Axis I diagnostic algorithms for myofascial pain and arthralgia that have excellent diagnostic accuracy.27 However, revised diagnostic algorithms alone, without recourse to TMJ imaging, were still inadequate for valid diagnoses of two of the three types of disc displacements (DD) and for degenerative joint disease (DJD). Original RDC/TMD Axis II instruments were shown to be reliable and valid for screening for psychosocial distress and pain-related disability, but revision was warranted for both increased scope and improved clinical efficiency.28,29

Table 1.

| 1992: Publication of RDC/TMD |

| ○ Expert-based classification of most common TMD derived from epidemiologic and clinic data |

| ○ Dual-axis system: Clinical conditions (Axis I) and pain-related disability & psychological status (Axis II) |

| 2001 - 2008: Validation Project |

| ○ Multicenter study with reference standard examiners |

| ○ Comprehensive assessment of the reliability and validity of the RDC/TMD |

| ○ Establish need to revise RDC/TMD |

| 2008: Symposium at IADR*** Conference (Toronto) |

| ○ Revised RDC/TMD presented to the international research community |

| ○ Published critique and recommendations to enhance use in research |

| 2009: International RDC/TMD Consensus Workshop at IADR Conference (Miami) |

| ○ Input from the international dental and medical clinical and research community as well as from patient advocate perspective |

| ○ Published critique and recommendations to facilitate use in clinical and research settings |

| 2010: Publication of Major Findings by Validation Project |

| ○ Revised RDC/TMD algorithms provided reliable and valid clinical criteria for pain-related TMD |

| ○ Demonstrated need for imaging for most TMJ disc displacements and degenerative joint disease |

| ○ Support for existing Axis II instruments |

| ○ Recommended development of DC/TMD with international input |

| 2010: Symposium at IADR Conference (Barcelona) |

| ○ DC/TMD presented to the international clinical and research community |

| ○ Critique and comments on Axis I diagnostic algorithms for the most common TMD and Axis II assessment protocol |

| 2011: International RDC/TMD Consensus Workshop at IADR conference (San Diego) |

| ○ Refinement of Axis I diagnostic algorithms for common and uncommon TMD |

| 2011-2012: Field Trials of Axis I Examiner Specifications and Axis I & II Self-report Instruments |

| ○ Test sites: Buffalo (US), Minneapolis (US), Malmö (Sweden), Aarhus (Denmark), Heidelberg (Germany), and Stockholm (Sweden) |

| 2012: Finalization of DC/TMD |

| ○ Further input from members of national and international TMD pain organizations |

| ○ Review of the DC/TMD by the IADR 2009 conference participants |

| 2013: Final Estimates of Reliability and Validity for Axis I Diagnostic Criteria |

| ○ Derived from the Validation Project Dataset |

| ○ Finalization of DC/TMD |

Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders

Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders

International Association for Dental Research

In July 2008, the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network sponsored a symposium at the International Association for Dental Research (IADR) Conference in Toronto entitled “Validation Studies of the RDC/ TMD: Progress Towards Version 2.”30 Presentation of the revised RDC/TMD Axis I diagnostic algorithms and Axis II findings by the Validation Project's key investigators was followed by critiques from researchers in the areas of radiology, neurology, pain psychology, and TMD and orofacial pain.31–36 A mandate emerged from the symposium in support of holding a consensus workshop for the development of a new DC/TMD.

In March 2009, the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network (IADR) and the Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group (of the International Association for the Study of Pain [IASP]) organized the “International Consensus Workshop: Convergence on an Orofacial Pain Taxonomy” at the IADR Conference in Miami to address the recommendations from both the Validation Project investigators29 and the 2008 Toronto meeting regarding development of the new DC/TMD. The Validation Project's findings and recommendations, as well as comprehensive literature searches regarding diagnostic tests, served as the basis for the resulting consensus-based recommendations that are available in the executive summary.37,38 An ad-hoc Taxonomy Committee was appointed by the workshop participants and charged with finalizing the workshop recommendations; these recommendations were then reviewed by the workshop participants for feedback and approval. The Validation Project's findings and recommendations were subsequently published in 2010.8,25–29

In July 2010, the working draft of the new DC/ TMD was presented to the international clinical and research community for critique and comments at a symposium at the IADR Conference in Barcelona, Spain. Further refinement of select new DC/TMD diagnoses occurred in 2011 at the “International RDC/ TMD Consensus Workshop” at the IADR Conference in San Diego. From 2011 to 2012, the examiner specifications for the Axis I assessment protocol and the Axis II instruments were field-tested. In 2012, the new DC/TMD manuscript was then reviewed and finalized by the Miami 2009 workshop participants for publication. Detailed information regarding the development of the new DC/TMD is available on the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network website.39

Concurrent with the above activities was the development of a new taxonomic classification structure. The Taxonomy Committee and selected members of the 2009 workshop used the taxonomic structures developed by the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP)40 to develop the structure used in this manuscript. This more comprehensive taxonomic structure and related diagnostic criteria were refined by members of the workshop held in 2011 in San Diego, and at the “International Consensus Workshop: Expanded TMD Taxonomy for Further Classification Research” in June 2012 at the IADR Conference in Iguacu Falls, Brazil. The AAOP council endorsed this taxonomic structure in 2012.

With each refinement of the DC/TMD algorithms, the Validation Project team used the available dataset and reference standards from that project to document new estimates of diagnostic validity. Each of these analyses was reviewed and approved by members of the Taxonomy Committee. When the final Axis I diagnostic algorithms were established, the Validation Project team also tested their inter-examiner reliability by using examination data collected from 46 patients by the 6 examiners who are implementing the TMJ Impact Project, the Validation Project's follow-up study. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were employed for validity and reliability estimates across multiple examiners as well as adjustment of variance estimates for correlated data within patients. For the Axis II portion of the new DC/TMD, the implementation of the consensus report from the 2009 Miami workshop was further refined based on recommendations from a subsequent workshop41 and recommendations from a recent publication that built upon Validation Project findings.28

Results

Overview

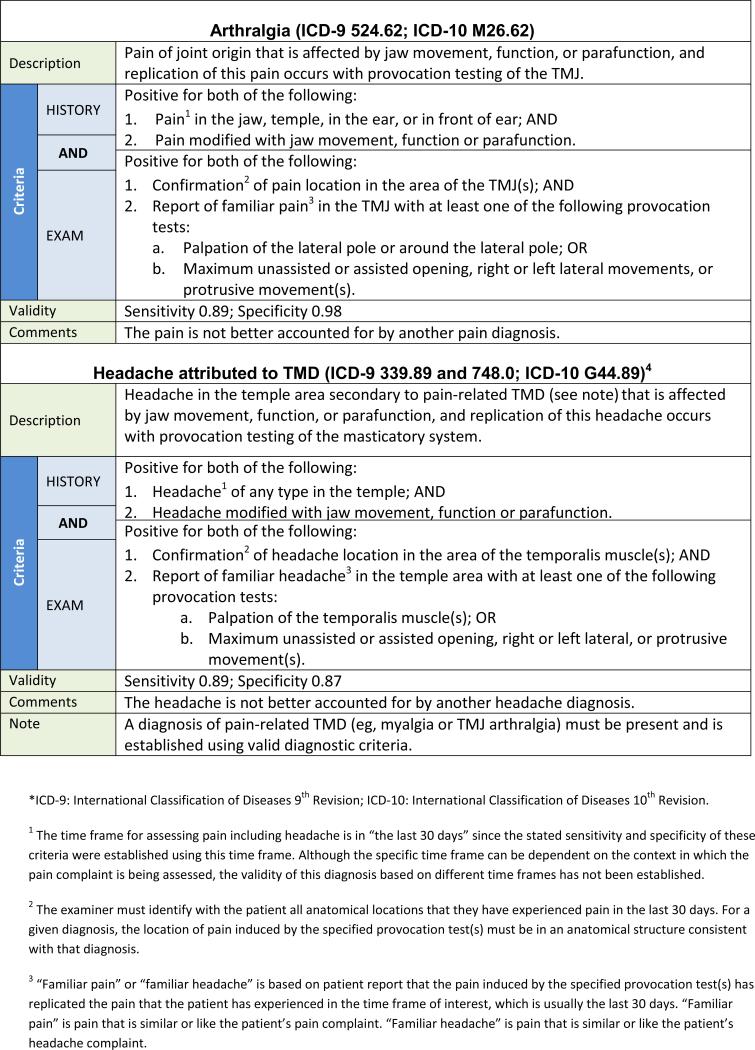

The following recommendations represent an evidence-based new DC/TMD intended for immediate implementation in clinical and research settings. The 12 common TMD include arthralgia, myalgia, local myalgia, myofascial pain, myofascial pain with referral, four disc displacement disorders, degenerative joint disease, subluxation, and headache attributed to TMD. The diagnostic algorithms with established estimates of sensitivity and specificity for the most common TMD are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Acceptable sensitivity and specificity for a definitive diagnosis are considered as sensitivity ≥ 70% and specificity ≥ 95%.3 Diagnostic criteria with lower target sensitivity or specificity, or having only content validity, were used when there was no available alternative. Decision trees are available that map the patient history responses and clinical findings to these specific disorders except for subluxation.42 Table 4 provides an expanded taxonomic classification structure for both common and less common TMD. The diagnostic criteria for these less common TMD have content validity but have not been assessed for criterion validity.43 The diagnostic criteria for the less common TMD represent revisions of the AAOP's diagnostic criteria that have been updated in a joint effort by members of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and the Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group of the IASP. Rigorous assessment of these diagnostic criteria for their criterion validity remains to be accomplished.

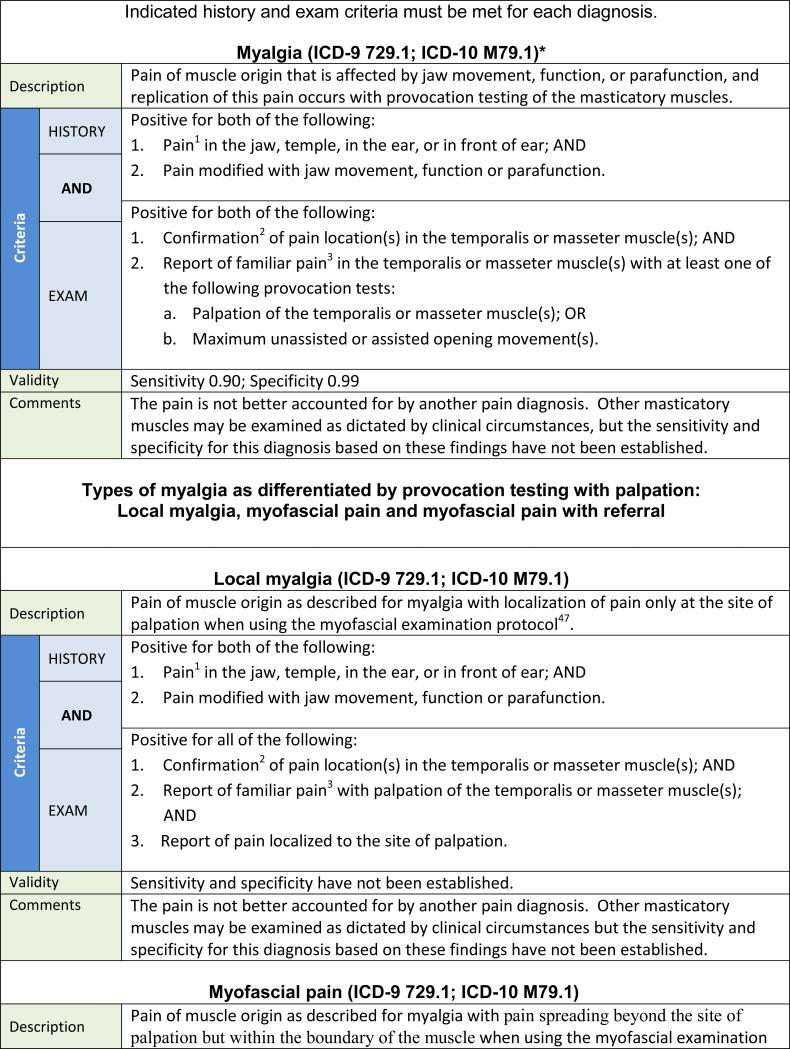

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for the Most Common Pain-Related Temporomandibular Disorders

|

|

|

|

|

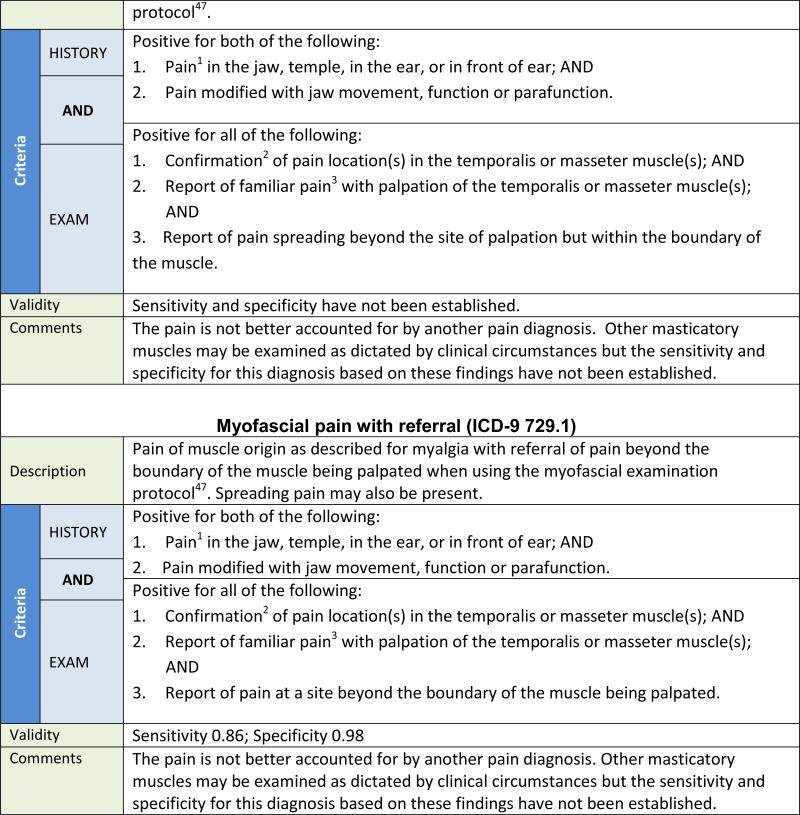

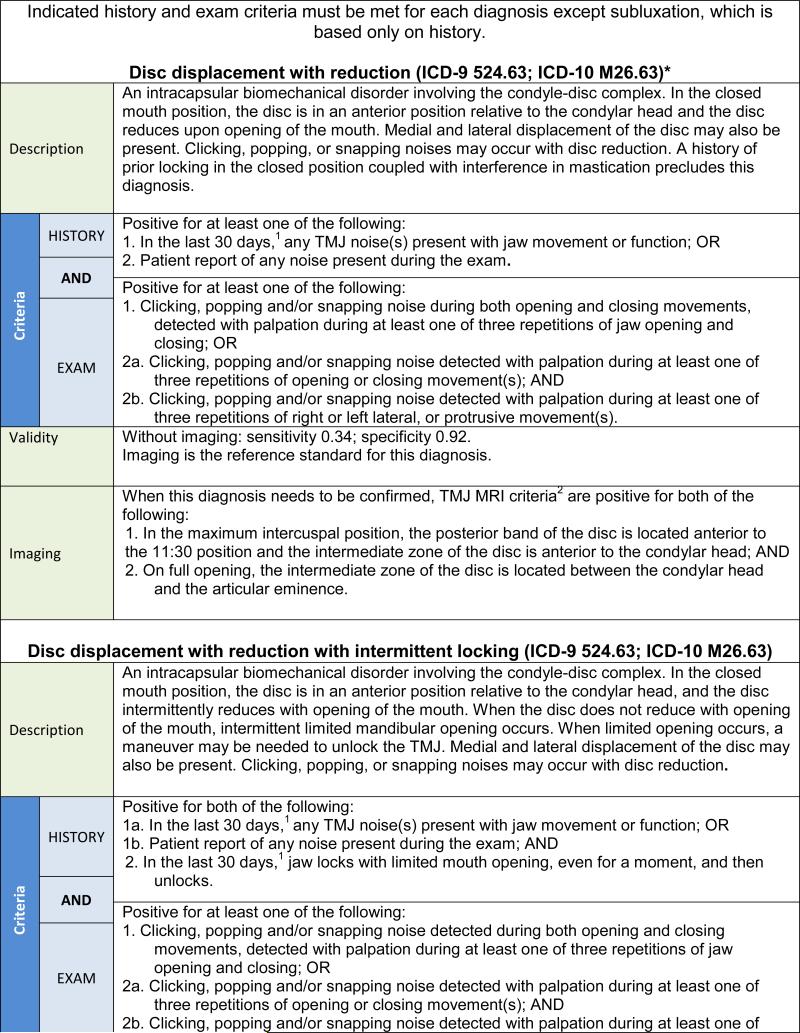

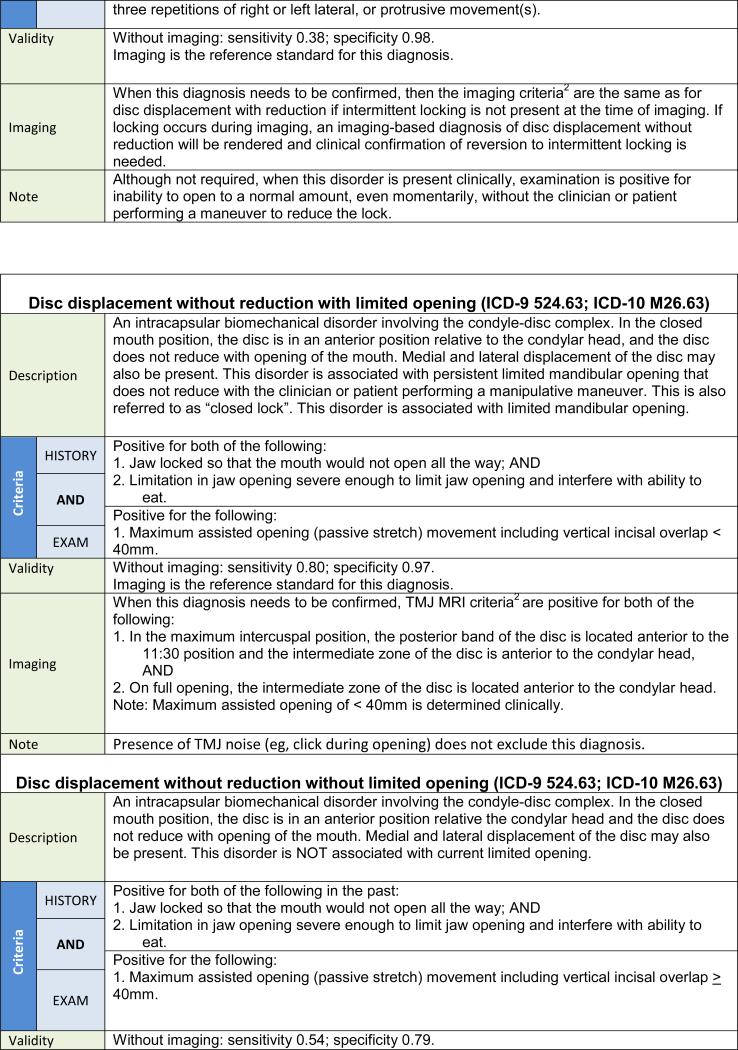

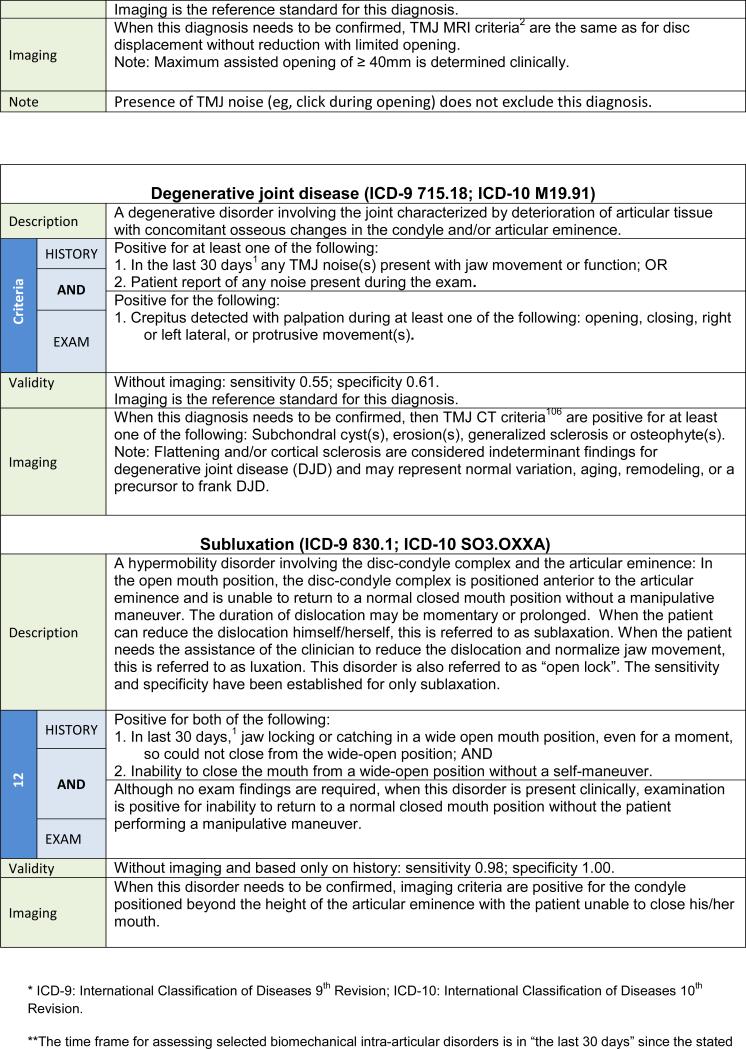

Table 3.

Diagnostic Criteria for the Most Common Intra-articular Temporomandibular Disorders

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

Taxonomic Classification for Temporomandibular Disorders

| I. TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT DISORDERS |

| 1. Joint pain |

| A. Arthralgia |

| B. Arthritis |

| 2. Joint disorders |

| A. Disc disorders |

| 1. Disc displacement with reduction |

| 2. Disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking |

| 3. Disc displacement without reduction with limited opening |

| 4. Disc displacement without reduction without limited opening |

| B. Other hypomobility disorders |

| 1. Adhesions / adherence |

| 2. Ankylosis |

| a. Fibrous |

| b. Osseous |

| C. Hypermobility disorders |

| 1. Dislocations |

| a. Sublaxation |

| b. Luxation |

| 3. Joint diseases |

| A. Degenerative joint disease |

| 1. Osteoarthrosis |

| 2. Osteoarthritis |

| B. Systemic arthritides |

| C. Condylysis/idiopathic condylar resorption |

| D. Osteochondritis dissecans |

| E. Ostronecrosis |

| F. Neoplasm |

| G. Synovial chondromatosis |

| 4. Fractures |

| 5. Congenital/developmental disorders |

| A. Aplasia |

| B. Hypoplasia |

| C. Hyperplasia |

| II. MASTICATORY MUSCLE DISORDERS |

| 1. Muscle pain |

| A. Myalgia |

| 1. Local myalgia |

| 2. Myofascial pain |

| 3. Myofascial pain with referral |

| B. Tendonitis |

| C. Myositis |

| D. Spasm |

| 2. Contracture |

| 3. Hypertrophy |

| 4. Neoplasm |

| 5. Movement disorders |

| A. Orofacial dyskinesia |

| B. Oromandibular dystonia |

| 6. Masticatory muscle pain attributed to systemic/central pain disorders |

| A. Fibromyalgia/ widespread pain |

| III. HEADACHE |

| 1. Headache attributed to TMD |

| IV. ASSOCIATED STRUCTURES |

| 1. Coronoid hyperplasia |

Table developed in collaboration with Peck and colleagues.43

The new DC/TMD Axis II protocol has been expanded by adding new instruments to evaluate pain behavior, psychological status, and psychosocial functioning. The inclusion of the biobehavioral domain has been well accepted in the pain field overall, and the specific inclusion of new DC/TMD Axis II instruments has been recommended as a general model for assessing any pain patient.44 Finally, a “stepped” assessment model is embedded in the new DC/TMD components, allowing the protocol to support assessment ranging from screening to comprehensive expert evaluation.

Workshop Recommendations for Axis I Pain-Related TMD Diagnoses

The Axis I TMD Pain Screener45 is a simple, reliable, and valid self-report instrument used to assess for the presence of any pain-related TMD, with sensitivity and specificity ≥ 0.95.46 For screening for pain-related TMD, the full six item version has sufficient reliability for assessing individuals, such as in a clinical setting, whereas a three-item version is suitable for assessment of a population in research settings. The DC/TMD Symptom Questionnaire (DC/TMD SQ) provides the necessary history for rendering a specific diagnosis in conjunction with the new DC/TMD painrelated diagnostic algorithms.

The changes in the diagnostic procedures for the pain diagnoses in the new DC/TMD, as compared to the corresponding disorders in the RDC/TMD, are summarized in Table 5. In the new DC/TMD, myalgia represents what was called myofascial pain in the RDC/TMD. The term myofascial pain now describes two new DC/TMD diagnoses: myofascial pain and myofascial pain with referral. Further detail regarding these changes can be found in the Examination Specifications.47 The diagnostic algorithms in the new DC/TMD for arthralgia and myalgia now include criteria for modification of pain by function, movement, or parafunction; these criteria are also included in the TMD Pain Screener. The clinical examination includes provocation tests for TMJ arthralgia of pain with any jaw movement (ie, opening, lateral, and protrusive) and TMJ palpation. For myalgia, the tests include pain with opening jaw movements and palpation of the temporalis and masseter muscles. Pain from these provocation tests must replicate the patient's pain complaint.

The disorder of myofascial pain with limited opening, as described in the RDC/TMD, is eliminated.

For the new DC/TMD, muscle pain diagnoses are organized into four major subclasses: myalgia, tendonitis, myositis, and spasm (see Table 4). Myalgia is further subdivided into three mutually exclusive types of myalgia: (1) local myalgia, defined as pain localized to the site of palpation; (2) myofascial pain, defined as pain spreading beyond the site of palpation but within the boundary of the muscle being palpated; and (3) myofascial pain with referral, defined as pain at a site beyond the boundary of the muscle being palpated. The diagnostic criteria for myalgia and one of its types, myofascial pain with referral, have criterion validity and are listed in Table 2. The palpation pressure for myalgia is 1 kg for 2 seconds, but to differentiate the three types of myalgia, the duration of the 1 kg of palpation pressure is increased to 5 seconds to allow more time to elicit spreading or referred pain, if present.47 The diagnostic criteria for local myalgia and myofascial pain, which have content validity but for which criterion validity has not been established, are presented in Table 2 for completeness; their respective validity estimates will be posted on the Consortium website after they are established.48 If a diagnosis of myalgia is desired, and no distinction between the three types is needed, then the more general diagnostic procedures as described in Table 2 are sufficient.

Table 5.

From RDC/TMD to DC/TMD: Comparison of Diagnostic Procedures for Pain-Related TMD

| RDC/TMD | DC/TMD | |

|---|---|---|

| HISTORY (applicable to all pain-related TMD) | ||

| Presence of masticatory system pain | ✓ | ✓ |

| Headache of any type in temporal region | ✓ | |

| Pain or headache modification with jaw movement, function, or parafunction | ✓ | |

| EXAMINATION | ||

| Arthralgia | ||

| Confirmation of location of pain in the joint | ✓ | |

| Pain with joint palpation | ||

| • Lateral pole | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Around lateral pole | ✓ | |

| • Posterior site | ✓ | |

| Pain with range of motion | ✓ | ✓ |

| Familiar pain with palpation or range of motion | ✓ | |

| Myalgia (“Myofascial pain” in RDC/TMD) | ||

| Confirmation of location of pain in a masticatory muscle | ✓ | |

| Pain with muscle palpation (required sites) | ||

| • Temporalis | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Masseter | ✓ | ✓ |

| • Posterior mandibular region | ✓ | |

| • Submandibular region | ✓ | |

| • Lateral pterygoid area | ✓ | |

| • Temporalis tendon | ✓ | |

| Pain with maximum unassisted or assisted opening | ✓ | |

| Familiar pain with palpation or opening | ✓ | |

| Local myalgia (new diagnosis) | ||

| Sustained palpation with no identification of spreading pain or referral patterns | ✓ | |

| Myofascial pain (new diagnosis) | ||

| Sustained palpation with identification of spreading pain but no referral patterns | ✓ | |

| Myofascial pain with referral (new diagnosis) | ||

| Sustained palpation with identification of referral patterns (spreading pain may also be present) | ✓ | |

| Headache attributed to TMD (new diagnosis) | ||

| Confirmation of location of headache in temple area | ✓ | |

| Familiar headache with palpation or range of motion | ✓ | |

Workshop Recommendations for Axis I TMJ Disc Displacement (DD) and Degenerative Joint Disease (DJD)

The clinical procedures for assessing DD with reduction, DD without reduction without limited opening, and DJD lead to clinical diagnoses based on procedures that exhibit low sensitivity but good to excellent specificity. Consequently, for treatment decision-making in selective cases, confirmation of a provisional clinical diagnosis requires imaging. In contrast, the clinical procedures for assessing DD without reduction with limited opening have acceptable sensitivity and specificity, and the clinical evaluation may be sufficient for the initial working diagnosis.

The changes made to the diagnostic procedures in the new DC/TMD for DD and DJD as compared to the RDC/TMD are summarized in Table 6. Further detail regarding these changes can be found in the Examination Specifications.47 TMJ noise by history is a recommended criterion for the intra-articular disorders of DD with reduction and DJD. This history criterion may be met by the patient's report of any joint noise (click or crepitus) during the 30 days prior to the examination, or by the patient's detection of any joint noise with jaw movements during the clinical examination. In addition, a diagnosis of DD with reduction requires examiner detection of clicking, popping, or snapping noises during the examination. Establishing a diagnosis of DJD necessitates examiner detection of crepitus (eg, crunching, grinding, or grating noises) during the examination. For DJD, no distinction between fine versus coarse crepitus is made. Finally, for DD without reduction, an assisted opening measurement (including the amount of vertical incisal overlap) of < 40 mm yields the subtype of “with limited opening,” while the measurement ≥ 40 mm yields the subtype of “without limited opening,” and joint noises, if present, do not affect the diagnosis of DD without reduction as long as the required criteria for DD without reduction are met.

DD with reduction with intermittent locking and TMJ subluxation are included as new disorders. The diagnostic algorithms for these disorders include specific criteria from the patient history, including current intermittent locking with limited opening for DD with reduction with intermittent locking and jaw locking in the wide-open position for TMJ subluxation.

Nomenclature change: The terms osteoarthritis and osteoarthrosis are considered to denote subclasses of DJD.

Table 6.

From RDC/TMD to DC/TMD: Comparison of Diagnostic Procedures for Disc Displacements and Degenerative Joint Disease with New History-Based Diagnosis of Subluxation

| RDC/TMD | DC/TMD | |

|---|---|---|

| HISTORY | ||

| “In last 30 days, any noise present” applicable to disc displacement with reduction with and without intermittent locking, and degenerative joint disease | ✓ | |

| “In last 30 days, jaw locks with limited mouth opening and then unlocks” applicable to disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking | ✓ | |

| “Ever have jaw lock or catch so that it would not open all the way” and “interfered with eating” applicable to disc displacement without reduction with and without limited opening | ✓ | ✓ |

| “In last 30 days, when you opened your mouth wide, jaw locked or caught so that it would not close all the way” applicable to subluxation | ✓ | |

| EXAMINATION | ||

| Disc displacement with reduction | ||

| Report by patient of any joint noise (click or crepitus) | ✓ | |

| Click detection (# of opening/closing cycles required for click) | 2 of 3 | 1 of 3 |

| Click detection during lateral and protrusive movements | ✓ | ✓ |

| 5mm vertical distance between reciprocal clicks | ✓ | |

| Elimination of click in protrusive position | ✓ | |

| Disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking | ✓ | |

| Disc displacement without reduction with limited opening | ||

| Unassisted opening* ≤ 35mm and assisted opening ≤ 4mm more than unassisted opening | ✓ | |

| Assisted opening* < 40mm | ✓ | |

| Contralateral movements < 7mm and/or uncorrected deviation to the ipsilateral side on opening | ✓ | |

| Absence of noise, or noise not meeting criteria for disc displacement with reduction | ✓ | |

| Disc displacement without reduction without limited opening | ||

| Unassisted opening* > 35mm and assisted opening > 4mm more than unassisted opening | ✓ | |

| Assisted opening* ≥ 40mm | ✓ | |

| Contralateral and protrusive movements ≥ 7mm | ✓ | |

| Noise not meeting criteria for disc displacement with reduction | ✓ | |

| Degenerative joint disease | ||

| Report by patient of any joint noise (click or crepitus) | ✓ | |

| Crepitus (only coarse) with palpation | ✓ | |

| Crepitus (either fine or coarse) with palpation | ✓ | |

Measurement of opening includes interincisal opening plus vertical incisal overlap.

Workshop Recommendations for Axis I Headache Disorders

“Headache attributed to TMD” is included as a new disorder type to replace “Headache or facial pain attributed to temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder“ as described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders II (ICHD- 2).49 The diagnostic algorithm for headache attributed to TMD has been previously published50 and has been incorporated into the beta version of the ICHD-3 (See Table 5).51

Workshop Recommendations for Axis II Evaluation

It is well recognized that patients’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses to pain are quite independent of the source of their pain, so the workgroup recommended instruments currently used in other areas of medicine to assess the psychosocial functioning associated with any pain condition. In addition, the Jaw Functional Limitation Scale (JFLS) was selected to assess jaw function specific to TMD. The criteria used to select the additional Axis II instruments were reliability, validity, interpretability, patient and clinician acceptability, patient burden, and feasibility, as well as availability of translated versions for different languages and cultures. All areas of biopsychosocial assessment with the recommended instruments are available from the Consortium52 and are summarized in Table 7.

Axis II screeners. Five simple self-report screening instruments are included for detection of pain-relevant psychosocial and behavioral functioning. The Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) is a short, reliable, and valid screening instrument for detecting “psychological distress” due to anxiety and/or depression in patients in any clinical setting.53 A cutoff of > 6, suggesting moderate psychological stress, should be interpreted as warranting observation, while a cutoff of > 9, suggesting severe psychological distress, should be interpreted as warranting either further assessment or referral.53 The Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) is a short, reliable, and valid instrument that assesses pain intensity and pain-related disability.10 The two GCPS subscales are: (1) Characteristic Pain Intensity (CPI), which reliably measures pain intensity, with ≥ 50/100 considered “high intensity,” and (2) the pain-disability rating, which is based on number of days that pain interferes with activity and on extent of interference with social, work, or usual daily activities. High pain and high interference, or moderate to severe disability (classified as Grades 3 or 4), should be interpreted as disability due to pain, warranting further investigation, and suggests that the individual is experiencing significant impact from the TMD on his or her life. The third instrument is a pain drawing of the head, jaw, and body, and it allows the patient to report the location of all pain complaints.54,55 Widespread pain suggests the need for comprehensive assessment of the patient. The fourth instrument is the reliable and valid short form (eight items) of the JFLS that assesses global limitations across mastication, jaw mobility, and verbal and emotional expression.56,57 The fifth instrument is the Oral Behaviors Checklist (OBC), which assesses the frequency of oral parafunctional behaviors.58,59

Comprehensive Axis II instruments. The instruments to be used when indicated by clinical specialists or researchers in order to obtain a more comprehensive evaluation of psychosocial functioning are listed in Table 7 and follow the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinic Trials (IMMPACT) recommendations.60 Those recommendations include assessment of pain intensity, physical functioning (both general and disease-specific), and emotional functioning. In addition to measuring pain intensity and pain disability (via GCPS, as described previously) and disease-specific physical functioning (via the 20-item version of the JFLS), the new DC/TMD includes new measures for a more comprehensive assessment of emotional functioning. This assessment uses the PHQ-961 for depression (with cutoffs of 5, 10, 15, and 20 representing, respectively, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe levels of depression) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)62 for anxiety (with cutoffs of 10 and 15 representing, respectively, moderate and severe levels of anxiety). Finally, like the RDC/TMD, the new DC/ TMD retains a measure for physical symptoms by using the PHQ-1563 (with cutoffs of 5, 10, and 15 representing, respectively, low, medium, and high somatic symptom severity) due to the overwhelming importance of overall symptom reporting in individuals with TMD.64 The pain drawing and the OBC are also components of the comprehensive assessment.

Table 7.

Recommended Axis II Assessment Protocol

| Domain | Instrument | No. of items | Screening | Comprehensive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) | 3 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Pain locations | Pain drawing | 1 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Physical function | Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) | 4 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Limitation | Jaw Functional Limitation Scale-short form (JFLS) | 8 | ✓ | |

| Jaw Functional Limitation Scale-long form (JFLS) | 20 | ✓ | ||

| Distress | Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) | 4** | ✓ | |

| Depression | Patient Health Questionnaire-9* (PHQ-9) | 9** | ✓ | |

| Anxiety | Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) | 7** | ✓ | |

| Physical symptoms | Patient Health Questionnaire-15* (PHQ-15) | 15 | ✓ | |

| Parafunction | Oral Behaviors Checklist (OBC) | 21 | ✓ | ✓ |

The RDC/TMD depression and non-specific physical symptoms instruments could be substituted for the PHQ-9 and PHQ-15, respectively, if continuity with legacy data is important.

Each of the PHQ-4, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 include one additional item beyond the number listed above; the additional item is a global reflective question regarding functional interference due to any of the endorsed symptoms on that instrument.

Data Collection Forms and Examination Specifications

A short, focused new DC/TMD Symptom Questionnaire (DC/TMD SQ)65 was developed to assess pain characteristics as well as history of jaw noise, jaw locking, and headache. The DC/TMD SQ provides the necessary history for the Axis I diagnostic criteria. The new DC/TMD operational specifications for the clinical tests, examination forms, DC/TMD SQ, and biobehavioral assessment instruments can be downloaded from the Consortium website38 and used without copyright infringement.

Validity of the Newly Recommended DC/TMD Axis I Diagnostic Algorithms

Sufficient data from the Validation Project existed to provide a credible estimate of the criterion validity for myalgia as a class with sensitivity of 0.90 (95% confidence limits of 0.87 and 0.94) and specificity of 0.99 (0.97, 1.00). Myofascial pain with referral as a type of myalgia showed sensitivity of 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) and specificity of 0.98 (0.97, 0.99). Finally, arthralgia had sensitivity of 0.89 (0.84, 0.92) and specificity of 0.98 (0.95, 0.99). Among the intracapsular diagnoses, excellent validity was confirmed for DD without reduction with limited opening, with sensitivity of 0.80 (0.63, 0.90) and specificity of 0.97 (0.95, 0.98). The validity for the other disc displacements was inadequate: DD with reduction had sensitivity of 0.34 (0.28, 0.41) and specificity of 0.92 (0.89, 0.94); DD with reduction with intermittent locking showed sensitivity of 0.38 (0.24, 0.54) and specificity of 0.98 (0.96, 0.99); and disc displacement without reduction without limited opening exhibited sensitivity of 0.54 (0.44, 0.62) and specificity of 0.79 (0.74, 0.83). The sensitivity of the recommended clinical criteria for DJD was 0.55 (0.47, 0.62) and specificity was 0.61 (0.56, 0.65). The total width of all confidence intervals was < 0.20, except for disc displacement with reduction with intermittent locking for which the total interval was 0.30.

Interexaminer Reliability of the Recommended DC/TMD Axis I Diagnostic Algorithms

Interexaminer reliability of myalgia, as a patient-specific diagnosis, was demonstrated to be excellent, with kappa = 0.94 (0.83, 1.00), as was also myofascial pain with referral, which had kappa = 0.85 (0.55, 1.00). GEE-based kappa estimates for the joint-specific diagnoses were computed using data from the TMJ Impact Project's examiner reliability assessments. Reliability for arthralgia was excellent, at kappa = 0.86 (0.75, 0.97). However, detection of intracapsular diagnoses, based only on clinical signs and symptoms, was too low for most reliability estimates to be credible. This was due to the low prevalence of these diagnoses in the convenience sample used for this reliability study. In addition, there were no cases of DD without reduction with limited opening (all measurements for vertical interincisal opening were > 40 mm), and DD with reduction with intermittent locking was rare (4 of 92 TMJs). DD with reduction showed kappa = 0.58 (0.33, 0.84). DD without reduction without limited opening manifested an excellent kappa of 0.84, although the confidence limits were wide (0.38, 1.00). The point estimate of examiner agreement on DJD was kappa = 0.33 with a wide confidence interval (0.01, 0.65) associated with the low examiner detection rate for DJD; this diagnosis was made by at least one examiner in only 20 TMJs during a total of 138 examinations performed in 46 subjects. Also contributing to the low kappa point estimate was low examiner agreement on a finding of crepitus, at kappa = 0.3 (0.00, 0.61).

Discussion

The new DC/TMD Axis I and Axis II are an evidence-based assessment protocol that can be immediately implemented in the clinical and research setting. Compared to the original RDC/TMD protocol,3 the new DC/TMD includes a valid and reliable Axis I screening questionnaire for identifying pain-related TMD as well as valid and reliable Axis I diagnostic algorithms for the most common pain-related TMD as part of a comprehensive TMD taxonomic classification structure. Diagnostic criteria for all but one of the most common intra-articular disorders lacked adequate validity for clinical diagnoses but can be used for screening purposes. The necessary information for fulfilling the Axis I diagnostic criteria is collected from the specified examination protocol in conjunction with the core self-report instruments that assess pain symptoms involving the jaw, jaw noise and locking, and headache. Axis II core assessment instruments assess pain intensity, pain disability, jaw functioning, psychosocial distress, parafunctional behaviors, and widespread pain. These changes in the core patient assessment instrument set serve as a broad foundation for patient assessment and further research. The new DC/ TMD includes important additions, deletions, and modifications to the original RDC/TMD that deserve comment. These changes are a result of research findings and expert contributions from professional clinical and research groups guided by the principle to create a new parsimonious DC/TMD based on the best available evidence. This article cites the core assessment instruments that existed at the time of this publication, and these instruments will be updated as indicated in the future with the most current versions available on the Consortium website.38

Features of the DC/TMD History and Examination Protocol

The criterion for a patient report of pain modified— that is, made better or worse—by jaw function, movement, or parafunction is now a requirement for all pain-related TMD diagnoses; this feature is shared with other musculoskeletal pains.66,67 Questions regarding pain modification are integral to the history and are derived from the TMD Pain Screener or from the more comprehensive DC/TMD SQ that contains all of the history questions required for the new DC/TMD diagnostic algorithms.45,46,65 Pain modification is especially important in differential diagnosis in a broader clinical setting when comorbid conditions may be present, especially other pain conditions of the trigeminal system.

The clinical provocation of “familiar pain” has proved useful in the assessment of other orthopedic and pain disorders.68–74 The rationale is that the clinician needs to provoke the patient's pain complaint in order for a positive examination response to be clinically meaningful. A patient report of familiar pain is required with pain provoked by jaw movement and/ or palpation to diagnose all pain-related TMD, including arthralgia, myalgia, the three types of myalgia, and headache attributed to TMD. Familiar pain is pain that is like or similar to the pain that the patient has been experiencing. The intent is to replicate the patient's chief complaint of pain(s) in such a way that the patient describes the provoked pain in the same way— because it is the same type of pain. This criterion minimizes false-positive findings from pain-provoking tests in asymptomatic patients and incidental findings in symptomatic patients. Similarly, a report of “familiar headache“ is required from the examination as part of the diagnostic algorithm for “Headache attributed to TMD.” It must, however, be emphasized that the presence of familiar pain is not associated exclusively with the diagnoses of arthralgia, myalgia, and the three types of myalgia, as other conditions may cause familiar pain during jaw movement or from palpation of jaw structures such as muscle or joint. For example, infection and rheumatoid disease affecting the TMJ can result in the report of familiar pain from movement and/or palpation of the associated structures. In order for the criterion of familiar pain to lead logically to the specified diagnosis, the signs must explain the symptoms; the symptom history, or additional assessment, must effectively rule out other competing diagnoses.75

For myalgia and the three types of myalgia diagnoses, palpation of only the temporalis and masseter muscles is required; mandatory palpation of the temporalis tendon, lateral pterygoid area, submandibular region, and posterior mandibular region has been eliminated because of poor reliability,76–78 and not examining these areas does not significantly affect the validity of these diagnoses.27 For example, the lateral pterygoid area is commonly tender in non-cases, leading to false positives when the RDC/TMD are used.76 It is also uncommon for these other sites to be painful to palpation when the masseter or temporalis muscles are not, but they may be included as part of the examination when clinically indicated or for specific research questions. For the same reason, palpation of the posterior aspect of the TMJ through the external auditory meatus has also been eliminated but can be used when indicated.

TMJ noises can be difficult to detect, even with auscultation using a stethoscope, and may be sporadically present. In addition, the data of the Validation Project have demonstrated that patient differentiation of noises such as clicking, crunching, grinding, or grating noises (ie, crepitus) was an inconsistent source of clinical information. Typically, such information gathering requires reviewing these noises with the patient and then carefully interpreting their responses. These data confirm the most reliable approach is based on patient detection of any such noise within the last 30 days or patient detection of any noise occurring with jaw movements during the clinical examination. Whether to use “last 30 days” or a different period is addressed in the footnote in Table 3. The distinction between coarse and fine crepitus was omitted, as these sounds are not reliably distinguished and the distinction does not contribute to the diagnostic accuracy of DJD.

Changes to Original RDC/TMD Pain Diagnoses

The original RDC/TMD diagnosis of myofascial pain with limited opening has not yet demonstrated unique clinical utility and was eliminated in the new DC/TMD. The remaining original RDC/TMD diagnosis of myofascial pain has been reorganized in the new DC/TMD into two new disorders with criterion validity: myalgia (as a subclass of muscle pain disorders) and myofascial pain with referral (as a type of myalgia); see Table 4. Although the diagnostic criteria for local myalgia and myofascial pain, as types of myalgia, have content validity, the criterion validity has not been established. Myofascial pain with referral is a distinct clinical disorder with central convergence accounting for the referral of pain to other anatomical sites.79–81 Referred pain has clinical utility for, at a minimum, differential diagnosis regarding the identification of pain in other anatomical locations, including pain referred to the teeth that is shown ultimately to be pain of muscular origin.

“Headache attributed to TMD” is a new Axis I diagnostic classification.82 Tension-type headache (TTH) and migraine have been associated with TMD.19,83–90 In particular, TTH and TMD share many symptoms,19,90,91 although this may not imply identical pathophysiology or underlying mechanisms.88,91,92 A subgroup of headache patients experience increased headache following masticatory system overuse such as clenching of the teeth.88,89,92,93 Longitudinal studies have found that the development of TMD was accompanied by an increase in headache and that the presence of TMD at baseline predicted the onset of headache.94,95 Finally, treatment of the masticatory system has also been associated with a report of decreased headaches.96–98 These findings suggest that some headaches may be secondary to TMD.

Frequency of TTH99 and migraine correlate with functional disability and are a useful patient characterization,100–102 and increased frequency of headaches in the temples is associated with increased symptoms of pain-related TMD.102 Future research will explore whether frequency of pain when used to subclassify headache attributed to TMD, TMJ arthralgia, and TMD myalgia improves the identification of patients with more complex pain problems. Consequently, frequency and duration of “jaw pain” is assessed by the DC/TMD Symptom Questionnaire— Long Form that was developed for the TMJ Impact Project; this is available on the Consortium website.103

Changes to Original RDC/TMD TMJ Diagnoses

A diagnostic category of DD with reduction with intermittent limited opening (ie, episodic self-limiting “closed lock”) was included in the new DC/TMD. This is a common, clinically significant “mechanical” joint disorder that can require treatment. Another newly included diagnostic category is the mechanical joint disorder of TMJ dislocation characterized by “open lock” of the jaw and typically diagnosed based on patient history. If the patient is able to reduce this dislocation, it is termed “subluxation,” and if the dislocation requires an interventional reduction, it is termed “luxation.” Sufficient data were only available to assess the diagnostic validity of subluxation.104

The low sensitivity for the diagnostic algorithms for DD and DJD suggests these criteria be limited to providing provisional diagnoses. For example, for a diagnosis of DD with reduction, a positive history of noise and the presence clinically of clicking noises (as specified) effectively rules in the diagnosis due to the high specificity of the criteria, while a negative finding can be associated with false negatives due to low sensitivity. Consequently, some DD with reduction will not have clinically detectable noise or will have fewer clicks or different types of noise, and the disorder will not be diagnosed using the clinical criteria.105 Based on available data, DD with reduction is highly prevalent and is probably without clinical consequence unless pain occurs with the noise, or functional limitations such as limited opening or interference in mastication are present. Nevertheless, imaging using MRI is required for a definitive diagnosis of TMJ DD, and CT imaging is required for a definitive diagnosis of DJD. The single diagnostic exception is DD without reduction with limited opening (ie, “closed lock”), which shows good diagnostic validity without imaging (ie, sensitivity 80%; specificity 97%). However, the criteria for DD without reduction with limited opening have not been assessed in subjects with other causes of limited opening such as adhesions, coronoid hyperplasia, or muscle contracture. The need for a definitive DD diagnosis, and thus the indication to use imaging, is based on whether the information gained will change the patient's treatment plan or prognosis. Reliable imaging criteria for these disorders are available.106

Taxonomic Classification Structure and Classification of the Less Common TMD

A comprehensive taxonomic system is presented in Table 4. The diagnostic criteria for the less common TMD were derived, in part, from the best available definitions for those disorders included in existing AAOP guidelines. This was augmented by a review of the literature for diagnostic criteria defining other disorders not identified in the AAOP guidelines. The comprehensive taxonomic system and criteria for these disorders is available43 and will be continually updated on the Consortium website as new information emerges. These AAOP-based diagnostic criteria were developed by clinicians and researchers according to their experience and the literature.40 Although these criteria have content validity, their criterion validity has not been assessed, so special caution should accompany their use clinically. Treatment decisions based on these diagnoses should be undertaken with careful consideration of all risks and benefits associated with the resulting care plan.

Nomenclature

Since the terms osteoarthrosis and osteoarthritis have not been consistently used in medicine, these terms were subclassified under the broader term DJD. Use of DJD is also endorsed by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons.107 When pain co-occurs with DJD, the additional diagnosis of arthralgia can be used—as is the case with DD. A former diagnosis of osteoarthritis by the RDC/TMD is now dually coded as degenerative joint disease and joint pain (ie, arthralgia).

Changes to Original RDC/TMD Axis II

IMMPACT guidelines for clinical trials assessing pain recommend that patients be assessed for pain intensity and emotional functioning as well as general and disease-specific physical functioning.60 These four domains are assessed using the core Axis II instruments of GCPS (pain intensity subscale), PHQ-4 (emotional functioning), GCPS (general physical functioning by using the pain interference subscale), and JFLS (disease-specific physical functioning). Domains that bridge behavior with Axis I and are of direct utility for the clinician and researcher have been added. The biopsychosocial model of pain recognizes that pain is not purely a sensory process but that it is always accompanied by cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects which influence how a patient reacts to and reports pain, and which, in turn, result in coping strategies that may be helpful or harmful in maintaining adequate functioning.22,23 If these coping strategies are harmful, they can contribute to the development of chronic pain. Indeed, a set of psychosocial factors such as anxiety, depressed mood, psychological distress, fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophic thoughts, passive coping strategies, and social isolation have been recognized as risk factors for the development of chronic pain in musculoskeletal disorders.108–110 Similar risk factors have also been identified for chronicity in individuals with TMD. 18,64,111,112

In addition, psychosocial factors are at least as important for the treatment outcome as are initial pain intensity and physical diagnoses.113,114 The expansion of Axis II instruments for the new DC/TMD allows for identification of patients’ psychosocial and behavioral status in order to identify factors that, if present, must be addressed from the beginning of any treatment in an attempt to decrease suffering and increase functioning. In addition, early biobehavioral intervention appears to reduce the risk of patients developing persistent or chronic pain.109,115 Core risk factor assessment instruments include the OBC to identify maladaptive parafunctional behaviors and pain drawings to readily identify presence of widespread pain or other regional pain conditions. Frequent parafunctional behaviors may operate at several levels, including that of possibly repetitive trauma to the masticatory system, and appear to be significant predictors for TMD onset and are strongly associated with chronic TMD pain.116,117 In addition, the presence of significant psychosocial distress should be considered as a particularly important comorbid condition contributing to TMD onset as well as being associated with chronic TMD pain.64,118

Widespread pain suggests potential systemic disorders, including rheumatic diseases and/or central sensitization (eg, fibromyalgia), suggesting the need for further medical assessment. It is therefore advisable that the core set of Axis II instruments be used routinely in all clinical assessments. Use of the Axis II instruments in the clinical setting will permit assessment of the biobehavioral constructs currently known to be relevant to pain disorders and thereby lead to appropriate interventions as guided by the patient's status.18,21

An in-depth evaluation of the patient's psychosocial status is important for all research studies comparing TMD treatment modalities. Axis II psychosocial factors have better prognostic value than Axis I physical diagnoses.18,112 Research that does not take into account these important risk factors cannot improve our understanding of TMD and of which treatments work and why.24

Clinical Application of the New DC/TMD

The comprehensive evaluation necessary to design a specific patient's care plan is beyond the scope of this article. The reader is referred to an example of a clinical assessment protocol75 that can be used, in conjunction with the new DC/TMD, to rule out other orofacial pathology, including odontogenic pathology, trigeminal autonomic dysfunction cephalalgias, other headache disorders, and neuropathic pain disorders. An “unusual” presentation such as swelling, warmth and redness, autonomic signs, or sensory or motor deficiencies warrants high suspicion, since these are not typical TMD signs. The new DC/TMD is an effective and efficient adjunct to well-developed clinical reasoning skills, keeping in mind that the history must lead to a provisional diagnosis, and the clinical examination, augmented when indicated by other assessment tools, is needed to confirm or refute this provisional diagnosis. The validity of the diagnostic criteria revolves around use of reliable clinical tests; several versions of the clinical procedures are available on the Consortium website.47 Finally, multiple diagnoses are permitted: one of the muscle pain diagnoses (eg, myalgia or one of three types of myalgia), as well as diagnoses for each joint, including a joint pain diagnosis, any one of four disc displacement diagnoses, a degenerative joint disorder diagnosis, and/or a subluxation diagnosis.

In addition to the formal new DC/TMD diagnoses for the common disorders, other diagnoses listed in Table 4 may be required to fully capture all findings; for example, a lateral pterygoid spasm could coexist with a myalgia of the other masticatory muscles, resulting in two muscle diagnoses.

The new DC/TMD assessment protocol has both screening and confirmatory tests for the most common Axis I physical diagnoses and for Axis II contributing factors (Table 8). The Axis I TMD Pain Screener is recommended for all patients in any clinical setting.46 A positive screen is followed by further evaluation to arrive at the specific TMD pain-related diagnoses. The Axis II screening instruments consist of 41 questions from the PHQ-4, GCPS, OBC, and JFLS (short form), as well as a pain drawing, with minimal burden to the patient and clinician10,53; their use is recommended when triage indicates a pain disorder is present, and their use should be considered mandatory in cases of persistent pain lasting 6 months or longer or in the presence of prior unsuccessful treatment(s). Overall, the Axis II screening instruments identify barriers to treatment response, contributors to chronicity, and targets for further intervention.15,16 Positive findings with these screening instruments require further investigation using the comprehensive Axis II assessment instruments listed in Table 7; or, to establish a definitive diagnosis, referral is required to the patient's physician or a qualified mental health provider, ideally a health psychologist or psychiatrist.119

Table 8.

Clinical and Research Applications of Selected DC/TMD Axis I and Axis II Tests

| Axis I: Physical diagnosis | Axis II: Psychosocial status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain diagnoses | Joint diagnoses | Distress and pain disability | ||

| Application | Clinical or research | Clinical | Clinical or research | |

| Screening test | TMD pain screener | DC/TMD for disc displacements, degenerative joint disease, and sublaxation | PHQ-4 and GCPS | PHQ-9, GAD-7, PHQ-15, and GCPS |

| Confirmatory test | DC/TMD for myalgia, arthralgia, and headache attributed to TMD | Imaging: MRI for disc displacements, CT for degenerative joint disease, and panoramic radiographs, MRI, or CT for sublaxation | Consultation with mental health provider | Structured psychiatric or behavioral medicine interview |

Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4), Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15).

The final two Axis II instruments can be used with any patient. The OBC assesses for the presence of parafunctional behaviors that may be a form of trauma to the masticatory system.120

Likewise, the JFLS can be used to identify jaw-related functional limitations that may be present in any patient and then can be used to document changes over time. Axis II instruments and their application are discussed more fully elsewhere.28,29,121 All Axis II instruments are available on the Consortium website.

Adjunctive Tests

The new DC/TMD provides the core provocation tests necessary for the diagnosis of masticatory muscle and TMJ pain, but false positives and negatives can occur. Adjunctive tests may include static and dynamic tests, joint play tests such as compression and distraction, bitetests, “end-feel” tests, clenching tests, and palpation of the other masticatory muscles that are not part of the core criteria.122–128 Even though these tests did not improve overall validity of the diagnostic algorithms, they may, nevertheless, be useful in specific circumstances in which the history suggests a pain-related TMD and the formal new DC/TMD examination protocol is negative.27,126,128,129 When used, these adjunctive tests must also provoke familiar pain. Occlusal tests also did not contribute to the diagnostic validity of any of the TMD, but occlusal factors including intercuspal occlusal contacts, open bite, and the slide from centric relation to maximum intercuspal position can all be affected by DD and DJD,130 and documentation of occlusal status during initial assessment is warranted. The history and clinical examination remains the cornerstone for TMD diagnosis, and all adjunctive tests, including electronic diagnostic instruments, require assessment for their diagnostic accuracy and evidence of incremental validity for a true positive diagnosis of TMD prior to being recommended for clinical use.131–133

Patient Advocacy

The workshop at Miami in 2009 had the benefit of obtaining patient advocate input. A paradigm shift was advocated from a doctor-based assessment to patient-reported assessment. In short, patients want their symptom experience to be a more central part of the assessment and treatment recommendations. For example, limited mouth opening has been traditionally assessed using less than 40 mm as a “cut-off”; a recent population-based study involving more than 20,000 individuals supports this cutoff.134 An alternative perspective is to ask patients if they perceive a limitation in their opening independent of this “cutoff.” Ultimately, what the patient believes, feels, and reports is as important as what the clinician is able to observe and measure.

Future Directions

The new DC/TMD protocol, like the original RDC/ TMD, needs to be further tested and periodically reassessed to make appropriate modifications to maximize its full value as new research findings are reported. Ongoing changes and updates to the new DC/TMD will be managed and available through the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network. The larger TMD community is encouraged to make recommendations for its development, including developing assessment tools for use in children and adolescents, to validate the new DC/TMD in diverse settings, and to expand the Axis II tools in order to contribute to the ongoing development of its validity and clinical utility.

In terms of immediate goals, ongoing processes through the Consortium include further development of the taxonomy for Axis I conditions and critical review of Axis II constructs and instruments. Research regarding the ontological structure of both Axis I and Axis II concepts is ongoing in order to develop more logical taxonomic concepts. Axis III is being developed for identifying clinically relevant biomarkers such as quantitative sensory measures as well as genomic or molecular profiles. Finally, an Axis IV is envisioned as a method to classify a patient into clinically meaningful categories by collapsing large amounts of variability across biopsychosocial and molecular genomic domains through, for example, the use of modern clustering models.135

Although the new DC/TMD protocol will be an important tool for future research projects addressing underlying TMD mechanisms and etiologies, it has limitations. It is now recognized that TMD are a heterogenous group with manifestations well beyond the signs and symptoms associated with the current Axis I diagnoses. TMD are frequently associated with complaints indicating one or more other persistent pain conditions.11,116 This fact requires a broader assessment of TMD patients beyond Axis I, and it underlies the significance of Axis II and the current development of Axis III. A more comprehensive medical assessment of comorbid physical disorders and biobehavioral status with expansion of Axis II risk determinants for TMD will allow for identifying subpopulations of patients based on underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.136

This will lead to the development of new algorithms and new diagnostic categories that are based on etiologies and a parallel classification based on mechanisms. Consequently, it can be expected that such categories, including the associated diagnostic procedures, will contribute to the development of personalized treatments for TMD and other related conditions with a high comorbidity with TMD. We are at the beginning of a new horizon that shows great promise in producing new diagnostic procedures and treatment modalities for TMD and other interrelated conditions.

Conclusion

The new DC/TMD protocol is intended for use within any clinical setting and supports the full range of diagnostic activities from screening to definitive evaluation and diagnosis. The new protocol provides a common language for all clinicians while providing the researcher with the methods for valid phenotyping of their subjects—especially for pain-related TMD. Although the validity data identifies the need for imaging to obtain a definitive TMJ-related diagnosis, imaging should not be used routinely but rather considered when it is important to a specific patient or a research question. The Axis II screeners provide the clinician with an easy method to screen for pain intensity, psychosocial distress, and pain-related disability for triaging, treatment planning, and estimating the patient's prognosis. The additional Axis II instruments, a core part of all TMD assessments, provide the clinician and researcher with current methods to further assess the status of the individual regarding multiple factors relevant to pain management. The new DC/TMD protocol is a necessary step toward the ultimate goal of developing a mechanism and etiology-based DC/TMD that will more accurately direct clinicians in providing personalized care for their patients.

Acknowledgments

Research performed by the Validation Project Research Group was supported by NIH/NIDCR U01-DE013331. The development of the examination specifications in support of the diagnostic criteria was also supported by NIH/NIDCR U01-DE017018 and U01-DE019784. Reliability assessment of Axis I diagnoses was supported by U01-DE019784. Workshop support was provided by the International Association for Dental Research, Canadian Institute for Health Research, International RDC/ TMD Consortium Network, Medotech, National Center for Biomedical Ontology, Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group of the International Association for the Study of Pain, and Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. The authors thank the American Academy of Orofacial Pain for their support; Terrie Cowley, president of the TMJ Association, for her participation in the Miami workshop; and Dr Vladimir Leon-Salazar for his assistance with finishing the manuscript. The Taxonomy Committee was composed of JeanPaul Goulet, Thomas List, Richard Ohrbach (chair), and Peter Svensson. The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Footnotes

International Association for Dental Research.

International Association for the Study of Pain.

Contributor Information

Eric Schiffman, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences School of Dentistry University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Richard Ohrbach, Department of Oral Diagnostic Sciences School of Dental Medicine University at Buffalo New York, New York USA.

Edmond Truelove, Department of Oral Medicine School of Dentistry University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA.

John Look, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences School of Dentistry University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Gary Anderson, Department of Developmental and Surgical Sciences School of Dentistry University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Jean-Paul Goulet, Section of Stomatology Faculty of Dentistry Laval University Quebec, Canada.

Thomas List, Odont Dr, Department of Stomatognathic Physiology Faculty of Odontology Malmö University Malmö, Sweden.

Peter Svensson, Dr Odont, Department of Clinical Oral Physiology School of Dentistry Aarhus University and Professor Center for Functionally Integrative Neuroscience MindLab Aarhus University Hospital Aarhus, Denmark.

Yoly Gonzalez, Department of Oral Diagnostic Sciences School of Dental Medicine University at Buffalo Buffalo, New York, USA.

Frank Lobbezoo, Department of Oral Kinesiology Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) University of Amsterdam and VU University Amsterdam MOVE Research Institute Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Ambra Michelotti, Department of Orthodontics and Gnathology School of Dentistry University of Naples Federico II Naples, Italy.

Sharon L. Brooks, Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine School of Dentistry University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

Werner Ceusters, Department of Psychiatry School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences University at Buffalo Director of Research of the Institute for Healthcare Informatics and Director of the Ontology Research Group New York State Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Life Sciences Buffalo, New York, USA.

Mark Drangsholt, Department of Oral Medicine School of Dentistry University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA.

Dominik Ettlin, University of Zurich Zurich, Switzerland.

Charly Gaul, Migraine and Headache Clinic Königstein, Germany.

Louis J. Goldberg, Department of Oral Diagnostic Sciences School of Dental Medicine University at Buffalo Buffalo, New York, USA.

Jennifer A. Haythornthwaite, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences School of Medicine Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Lars Hollender, Odont Dr, Division of Oral Radiology Department of Oral Medicine School of Dentistry University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA.

Rigmor Jensen, Danish Headache Center Department of Neurology Glostrup Hospital University of Copenhagen Copenhagen, Denmark.

Mike T. John, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences 6-320 Moos Tower University of Minnesota Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Antoon De Laat, Department of Oral Health Sciences KU Leuven and Dentistry, University Hospital Leuven Leuven, Belgium.

Reny de Leeuw, Department of oral Health Science College of Dentistry University of Kentucky Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

William Maixner, Mary Lily Kenan Flagler Bingham Distinguished Professor and Director Center for Neurosensory Disorders University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA.

Marylee van der Meulen, Department of Oral Kinesiology Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) University of Amsterdam and VU University Amsterdam MOVE Research Institute Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Greg M. Murray, University of Sydney Sydney, Australia.

Donald R. Nixdorf, Department of Diagnostic and Biological Sciences and Adjunct Assistant Professor Department of Neurology University of Minnesota, Minneapolis and Research Investigator HealthPartners Institute for Education and Research Bloomington, Minnesota, USA.

Sandro Palla, Dr Med Dent, Emeritus University of Zurich Zurich, Switzerland.

Arne Petersson, Odont Dr, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Faculty of Odontology Malmö University Malmö, Sweden.

Paul Pionchon, Department of Orofacial Pain and Department of Psychology Faculty of Odontology Université d'Auvergne Clermont Ferrand, France.

Barry Smith, Departments of Philosophy, Neurology, and Computer Science University at Buffalo Buffalo, New York, USA.

Corine M. Visscher, Department of Oral Kinesiology Academic Centre for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA) University of Amsterdam and VU University Amsterdam MOVE Research Institute Amsterdam Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Joanna Zakrzewska, Division of Diagnostic, Surgical and Medical Sciences Eastman Dental Hospital UCLH NHS Foundation Trust London, UK.

Samuel F. Dworkin, Emeritus Department of Oral Medicine School of Dentistry and Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences School of Medicine University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA.

References

- 1.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research [7/28/2013];Facial Pain. http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/FindDataByTopic/FacialPain/

- 2.Feinstein AR. Clinical judgment. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1967. p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: Review criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:301–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loeser JD, Fordyce WE. Chronic pain. In: Carr JE, Dengerink HA, editors. Behavioral Science in the Practice of Medicine. Elsevier; New York: 1983. pp. 331–346. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merskey H. Introduction. In: Giamberardino MA, Jensen TS, editors. Pain Comorbidities: Understanding and Treating the Complex Patient. IASP Press; Seattle: 2012. pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Truelove EL, Sommers EE, Le Resche L, Dworkin SF, Von Korff M. Clinical diagnostic criteria for TMD. New classification permits multiple diagnoses. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:47–54. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1992.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.John MT, Dworkin SF, Mancl LA. Reliability of clinical temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. Pain. 2005;118:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truelove E, Pan W, Look JO, et al. The Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders. III: Validity of Axis I diagnoses. J Orofac Pain. 2010;24:35–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turk DC, Rudy TE. Towards a comprehensive assessment of chronic pain patients. Behav Res Ther. 1987;25:237–249. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin SF, Von KM, LeResche L. Multiple pains and psychiatric disturbance. An epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:239–244. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810150039007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osterweis M, Kleinman A, Mechanic D, Institute of Medicine . Committee on Pain, Disability, and Chronic Illness Behavior. Pain and Disability: Clinical, Behavioral, and Public Policy Perspectives. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1987. p. 306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin SF, von Korff MR, LeResche L. Epidemiologic studies of chronic pain: A dynamic-ecologic perspective. Ann Behav Med. 1992;14:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcusson A, List T, Paulin G, Dworkin S. Temporomandibular disorders in adults with repaired cleft lip and palate: A comparison with controls. Eur J Orthod. 2001;23:193–204. doi: 10.1093/ejo/23.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin SF, Huggins KH, Wilson L, et al. A randomized clinical trial using Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders-Axis II to target clinic cases for a tailored self-care TMD treatment program. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16:48–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dworkin SF, Turner J, Mancl L, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a tailored comprehensive care treatment program for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain. 2002;16:259–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epker J, Gatchel RJ. Prediction of treatment-seeking behavior in acute TMD patients: Practical application in clinical settings. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garofalo JP, Gatchel RJ, Wesley AL, Ellis E., 3rd. Predicting chronicity in acute temporomandibular joint disorders using the research diagnostic criteria. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:438–447. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballegaard V, Thede-Schmidt-Hansen P, Svensson P, Jensen R. Are headache and temporomandibular disorders related? A blinded study. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:832–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Meulen MJ, Lobbezoo F, Aartman IH, Naeije M. Ethnic background as a factor in temporomandibular disorder complaints. J Orofac Pain. 2009;23:38–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epker J, Gatchel RJ, Ellis E., 3rd A model for predicting chronic TMD: Practical application in clinical settings. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:1470–1475. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]