Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the feasibility of focal intraluminal irreversible electroporation (IRE) in the ureter with a novel electrode catheter and to study the treatment effects in response to increasing pulse strength.

Material and Methods

Five IRE treatment settings were each evaluated twice for the ablation of normal ureter in five Yorkshire pigs (1–4 ablations/animal, total of 10 ablations) using a prototype device under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. Animals received either unilateral or bilateral treatment, limited to a maximum of two ablations in any one ureter. Treatment was delivered with increasing pulse strength (1000V–3000V; increments of 500V) while keeping the pulse duration (100 µseconds) and number of pulses (90) constant. Ureter patency was assessed immediately following treatment with an antegrade ureteropyelography. Animals were sacrificed within 4 hours following treatment, and treated urinary tract was harvested for histopathologic analysis using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s Trichrome (MT) stains.

Results

IRE was successfully performed in all animals without evidence of ureteral perforation. H&E analysis of IRE treatments demonstrated full thickness ablation at higher field strengths (mucosa to the adventitia). MT stains showed preservation of connective tissue at all field strengths.

Conclusion

Intraluminal catheter directed IRE ablation is feasible and produces full thickness ablation of normal ureters. There was no evidence of lumen perforation even at the maximum voltages evaluated in the study.

Keywords: catheter directed therapy, image guided intervention, interventional radiology, irreversible electroporation, genitourinary intervention

Introduction

Irreversible electroporation (IRE) has been evaluated in multiple preclinical studies (1–6) for focal ablation of renal parenchyma adjacent to the renal pelvis and the ureter in large animal models. Results from these studies indicate that IRE may be safe for the focal ablation of tissue near such heat-sensitive structures (1–2). IRE of the renal parenchyma causes cell death with preservation of the extracellular matrix and other collagenous structures within the treated region (1,5). Acute loss of urothelium in the collecting system was reported, which demonstrated complete recovery within 2–3 weeks following treatment (6). Studies have also reported the absence of clinically significant remodeling or disruption of the urinary collecting system (1,2). Long-term clinical and imaging follow up after renal IRE in animals showed preservation of normal urinary function and flow characteristics (6). IRE has also been evaluated for the focal ablation of renal tumors in humans in a treat and resect trial (7). Results from this study suggest that IRE may be a safe and feasible technique and may offer advantages over thermal ablation including greater sparing and rapid recovery of normal renal tissues and shorter treatment duration. Further evaluation of IRE in humans (8) has provided feasibility and safety data for treatment of tumors adjacent to bile ducts (9), pancreatic ducts (10,11), or nerves (12).

Ureteroscopic and percutaneous management of urothelial cancer is typically used with patients who are contraindicated for surgical treatment because of existing conditions such as poor renal function, bilateral cancer or presence of chronic kidney conditions. Treatment is mostly used in patients with low grade disease. However, clinically used ablative approaches of electro-diathermy or laser treatment is associated with high complication rates (14%) and high rate of disease recurrence (52%) (19). The inability to safely perform deep treatment may be a key factor limiting the wider use of ablative therapy. Sparing of the renal collecting system from injury and post-treatment urothelial regeneration may make IRE an alternative for the treatment of early-stage urothelial cancers. The development of a new catheter mounted electrode has enabled image guided focal IRE for endoluminal treatment of urothelial tumors that could preserve urinary tract form and function. In this study, we examine feasibility, acute safety and tissue response to catheter mounted endoluminal IRE in swine ureters using a clinically relevant range of increasing energy delivery settings.

Materials and Methods

Prototype Catheter

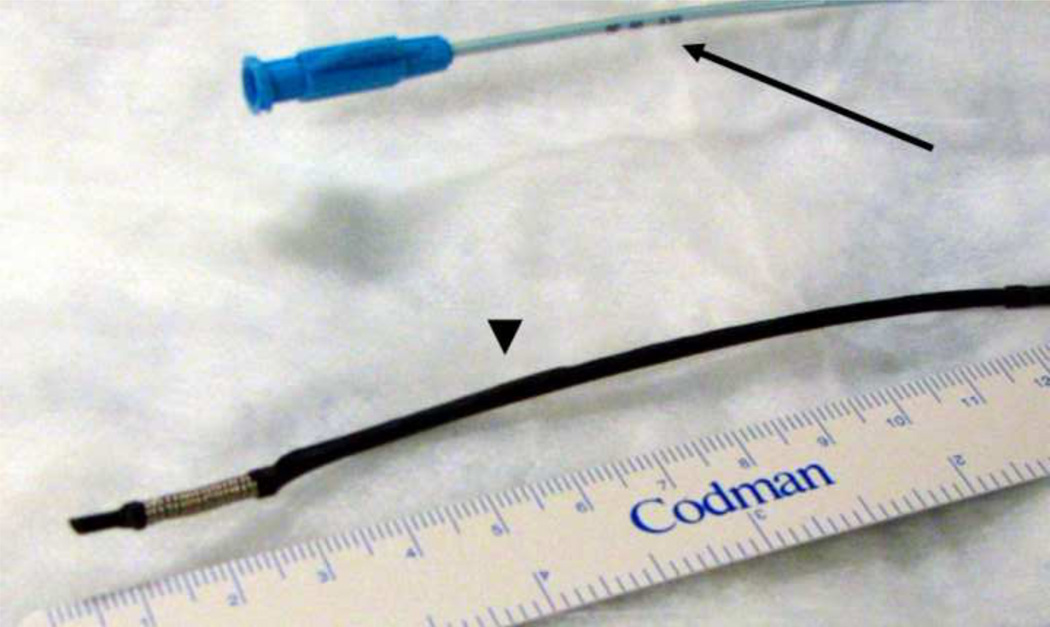

A flexible electrode catheter was created by winding 22 gauge (0.025 in. diameter) medical grade stainless steel tubing (316 LVM; Amazon Supplies) at the distal tip of a straight tip catheter (Soft-Vu, 65 cm, 5 Fr., Angiodynamics Inc., Latham, NY) to create an electrode with a working length of 15 mm (Figure 1). The wiring for the passage of current was passed along the body of the catheter, leaving the inner lumen open for guidewire access. The electrode was sized to be 2.5 mm in external diameter to allow the gentle dilation of the ureter and achieve uniform contact between the electrode coil and the tissues. The external diameter of the modified device was ~7Fr.

Figure 1.

Prototype catheter mounted electrode used for intraluminal IRE of swine ureter. The catheter hub and body are blue (arrow), and the insulated portions of the catheter overlying the wiring are black in appearance (arrowhead).

Experimental Procedure

The goal of the experiments was to evaluate IRE delivered at five different voltage values. Treatment at each voltage was attempted twice, once each in the proximal or distal ureter. As the study involved a new technique (IRE), new type of procedure (fluoroscopy guided ablation of ureter wall) and device, the experiments had to be performed in an incremental fashion. The first two animals received a single treatment each at voltages (2500V and 2000V) that were expected to evoke a definite response in the tissue. The experience gained from the first two studies was used to perfect the experimental procedure. The next two animals received two treatments each, and the last animal received four treatments. In case of animal 3 and 4, choice of treatment location was also dictated by the ability to establish percutaneous access to the ureter and the reach of the catheter device inside the lumen. Treatment was limited to a maximum of two ablations in any one ureter. A total of 10 treatments were completed, distributed over five animals. The chronological sequence of experiments and treatment parameters evaluated in each animal can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence of experiments and treatment settings evaluated in the study.

| Animal# | Ureter Treatment Location | Voltage Applied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Right distal | 2500V |

| 2 | Right distal | 2000V |

| 3 | Right proximal | 2500V |

| Left proximal | 2000V | |

| 4 | Right proximal | 3000V |

| Right distal | 3000V | |

| 5 | Left proximal | 1500V |

| Left distal | 1000V | |

| Right proximal | 1500V | |

| Right distal | 1000V |

Following an experimental protocol approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, five female Yorkshire swine (weight range 35–50 kg) were sedated with intravenous tiletamine hydrochloride and zolazepam hydrochloride (6 mg/ kg; Telazol; Fort Dodge Animal Health, IA) and maintained on general anesthesia with inhaled isoflurane (2–3% Aerrane; Baxter Healthcare, Round Lake, IL). Pigs were positioned prone on a fluoroscopy table and were prepared and draped in a sterile fashion. Access to the ureter was obtained via direct calyceal puncture using a 21 gauge needle under ultrasound guidance (Prosound; Hitachi-Aloka, Wallingford, CT). Location in the collecting system was confirmed by injection of dilute iohexol contrast (Omnipaque 300, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) under fluoroscopic visualization (Innova, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). After serial dilation over a wire, a 9 Fr 10-cm length sheath (Pinnacle, Terumo, Somerset, NJ) was inserted into the proximal ureter on one side.

The IRE catheter was introduced into the ureter through the inner lumen of the sheath using a guidewire to maintain access. The guidewire was removed prior to treatment delivery. The catheter coil served as a monopolar electrode and a grounding pad (ESRS return electrode, Bovie Medical, Tampa, FL) attached to the flank of the animal completed the circuit for IRE pulse delivery. After fluoroscopic confirmation of catheter location, rocuronium (0.7–0.12 mg/kg) was administered before IRE pulse delivery and was titrated to maintain paralysis during IRE treatment. Pulses were delivered by a using a commercial generator (Nanoknife, Angiodynamics, Latham, NY). Pulse duration (100 µs) and number (90 pulses) remained constant for voltage settings evaluated in this study. Electrocardiography was continuously monitored (GE Marquette Mac 5000; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) but pulse delivery was not synchronized with the cardiac cycle. The IRE catheter was removed after completion of pulse delivery and patency of the ureter lumen was assessed by antegrade injection of saline diluted iohexol contrast immediately following treatment. Fluoroscopic imaging was used to monitor for extravasation of contrast material as well as assess ureteric anatomy and flow. The animal was sacrificed under anesthesia within 4 hours following IRE pulse delivery. Euthanasia was performed with intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (87 mg/kg) and phenytoin sodium (11 mg/kg) (Euthasol; Vibrac AH, Fort Worth, Tex).

Histologic Analysis

The ureter and the kidney on the side receiving treatment, including the vesicoureteric junction, were removed en-bloc for analysis. The renal pelvis was entered with scissors and the pelvis and ureter were dissected longitudinally, exposing the mucosal surface. The ureteral mucosa was visually inspected to identify treatment locations, which were then sectioned and stored in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution. Samples of normal ureter distant from treated regions were also analyzed. A cross-section from each sample was processed in alcohol and xylene, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4-µm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin and Masson trichrome (MT). Histopathologic analysis was performed by an experienced veterinary pathologist (SM). The histology slides were evaluated by the pathologist for the depth to which treatment effect was seen penetrating in the major layers of the ureter (urothelium, lamina propia, muscularis and the adventitia). Further, each layer showing treatment effect was scored on a scale 1–4. The lowest score of 1 was given when few or no cells were seen exhibiting features of necrosis observed in the treatment region. The highest score of 4 was given when all evaluated cells in a given layer exhibited signs of necrosis without observable presence of viable cells in the treated region. Intermediary scores (2 or 3) were assigned when regions of necrosis and viable cells were found interspersed in the treatment zone. Scores were independently assigned for both the tissue samples from a treatment setting, and the lower score of the two was considered as the final treatment outcome for that particular treatment setting.

Results

Procedure Outcomes

The IRE procedure was technically successful for all 10 treatments. The two treatments delivered at 3000V resulted in high current load on the generator, leading to transient interruption of treatment. The remaining pulses were delivered following a brief resting period to allow recovery of tissue impedance. This was not encountered during treatment delivery at other voltage settings. Delivery of pulses at all voltage settings resulted in significant current induced neuromuscular activation in the immediate vicinity of the grounding pad. Due to the potential for catheter migration secondary to skeletal muscle contraction, intraprocedural fluoroscopy was used to confirm stability of the electrode position in all cases. EKG monitoring during the procedure did not reveal any impact of IRE pulse delivery on the electrocardiogram. Antegrade contrast evaluation of the treated ureters immediately following the procedure showed no signs of acute extravasation or dilation (Figure 2). Fluoroscopic evaluation after the two treatments at 3000V and one of the two treatments at 2500V showed impeded peristaltic segments in the vicinity of electrode location. However, all ureters remained patent and normal urinary flow was observed to be restored within 1–2 hours in the two animals that had demonstrated impeded peristalsis.

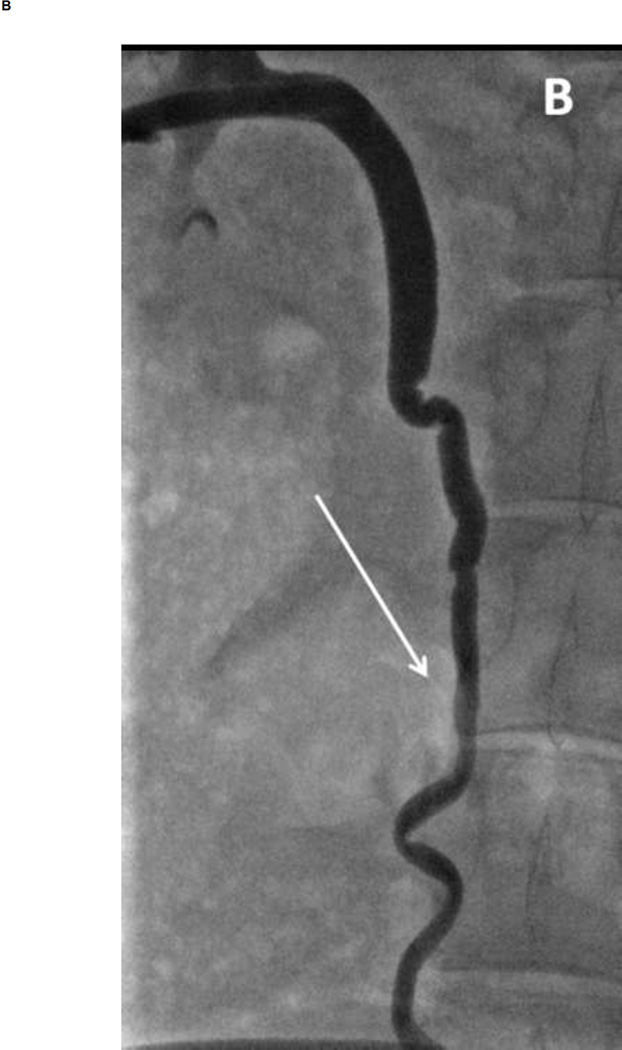

Figure 2. Fluoroscopic images during IRE of the ureter.

(A) Image acquired immediately following delivery of pulses (2000V treatment setting). The electrode can be seen within the lumen (arrow). Flow of contrast can be observed with some evidence of spasm delaying flow. (B) Image acquired within four hours following treatment. Ureter lumen appears patent without evidence of perforation or extravasation of contrast media.

Gross Pathology

At gross examination, well-demarcated focal lesions were observed in the ureter (Figure 3) corresponding to treatment location in all animals. Compared to the pale tan coloration of normal untreated ureter, treated regions were red-brown in appearance. No visually observable gross changes in surrounding fat, bowel, or kidney were seen during necropsy of the animals to recover the treated tissue. Treatment regions measured approximately 15 mm long in all evaluated sections; exact measurements were confounded by tissue edema and post-mortem tissue deformation.

Figure 3. Photograph of exposed ureteral mucosa treated at 2000V, after formalin fixation.

Gross visual examination reveals a well defined dark red to brown region (arrowhead) indicative of tissue injury that appears distinctly different from surrounding normal tissue (arrow). The lesion measures approximately 18mm in length.

Histopathology

Histopathologic analysis identified ablation sites in 10/10 treated sites. Sections of untreated ureter adjacent to the treatment area appeared normal on gross and histopathologic analysis. When compared to normal untreated ureter, ureteral tissue treated with IRE (Figure 4) showed treatment related changes through the full thickness (mucosa to adventitia) of the ureter wall and the full circumference of ureteral lumen. Treatment related effects could be observed in all the four layers of the ureter (urothelium, lamina propia, muscularis and adventitia), with evidence of cell necrosis in every layer. Cell necrosis was identified based on nuclear shrinkage and pyknosis of nuclei. Figure 5 depicts the basis of our scoring scheme to quantify necrosis in tissue samples, and the figure insets detail typical histological findings at different conditions.. Regions of necrosis appeared patchy at lower voltage settings (). At 1000V, only the urothelial layer was given a score of 3 while the other layers were scored at 2. At 1500V, all layers were scored at 3, and even the urothelium did not exhibit complete necrosis of cells in the treatment region. Treatments performed at 2000V or higher received the maximum score of 4 in all layers examined. Interruption of pulse delivery at 3000V did not seem to affect the quality or penetration of cell necrosis on histological analysis. Complete results are presented in Table 2.. Necrotic regions showed ulceration and sloughing of the urothelium, with edema, hyperemia, hemorrhage and mild neutrophilic infiltration. MT staining (Figure 6) revealed intact collagen fibers in all layers of the wall, however individual fibers were frequently separated due to stromal edema in the area.

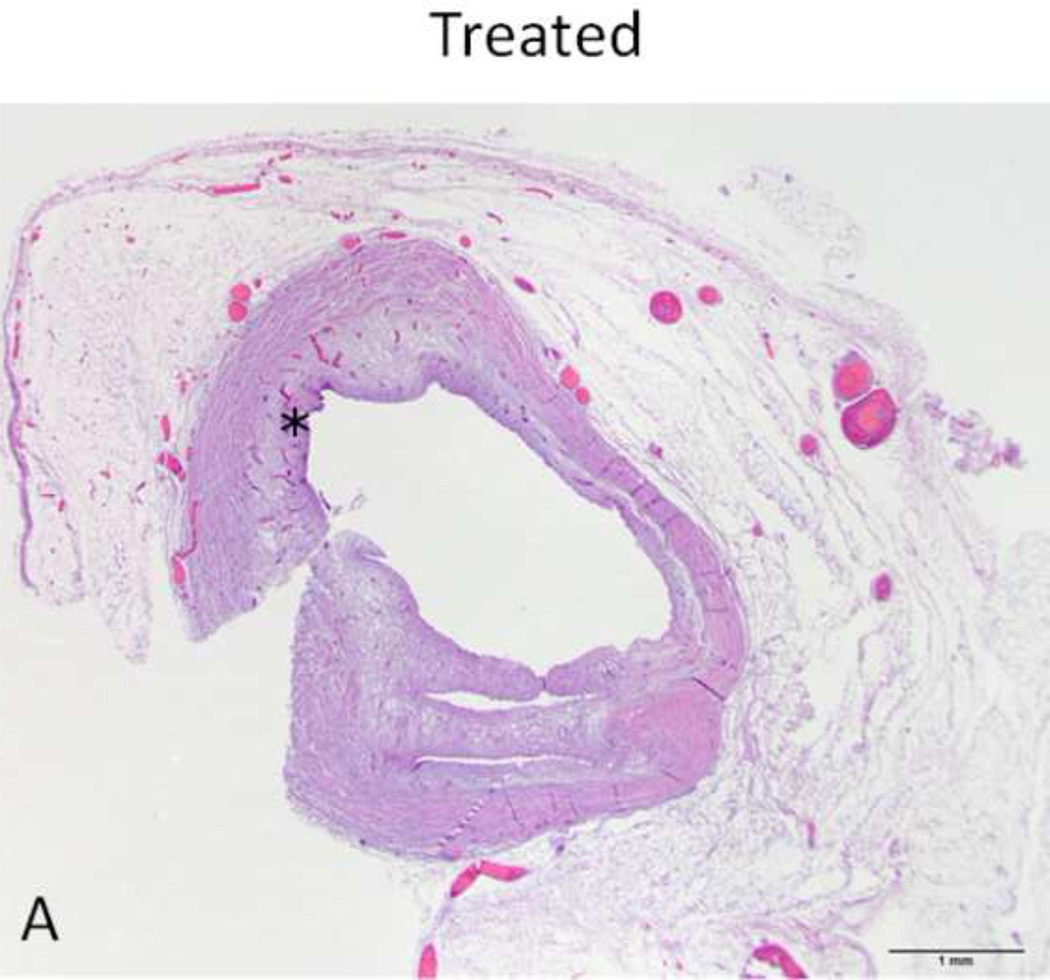

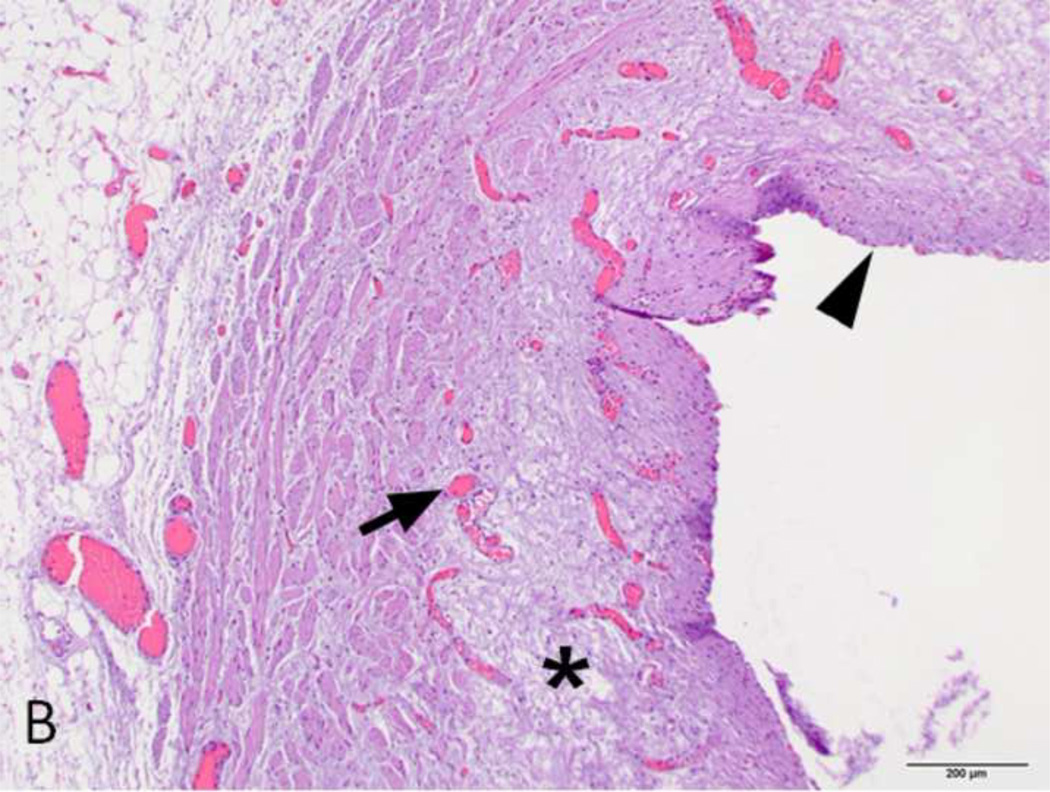

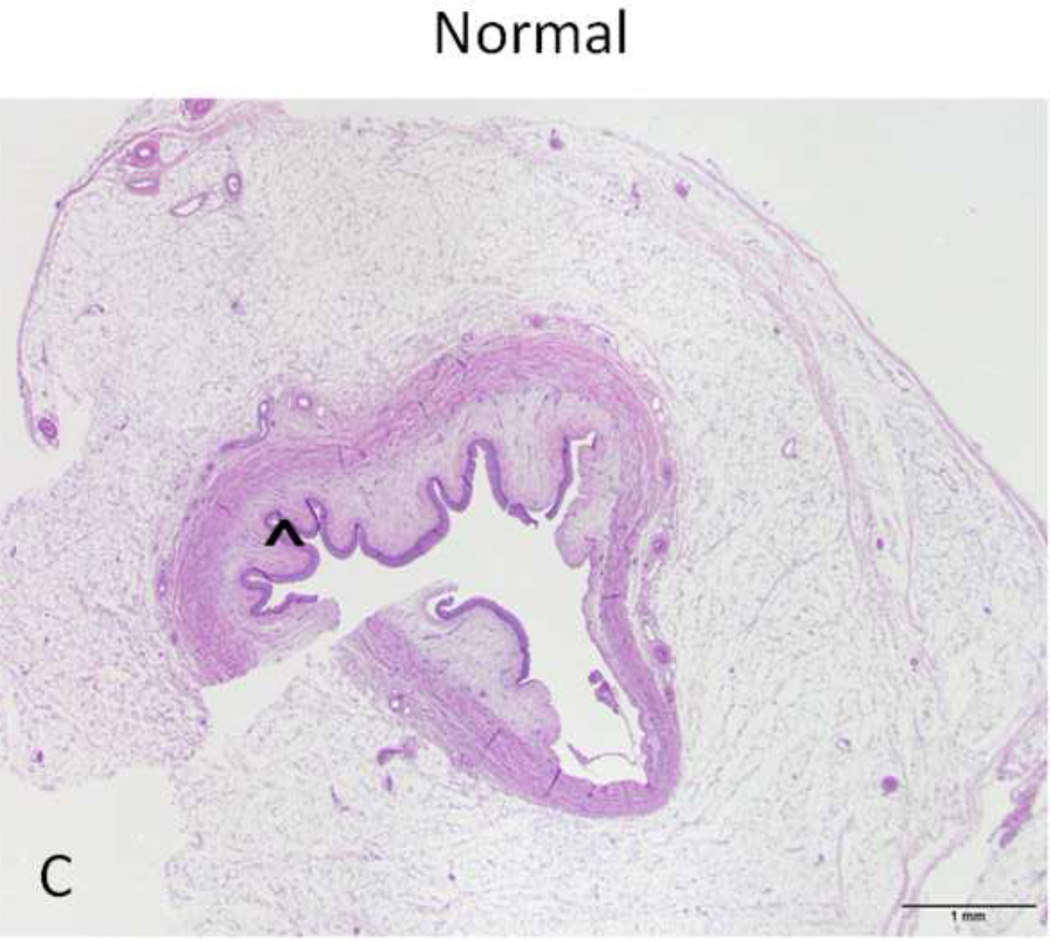

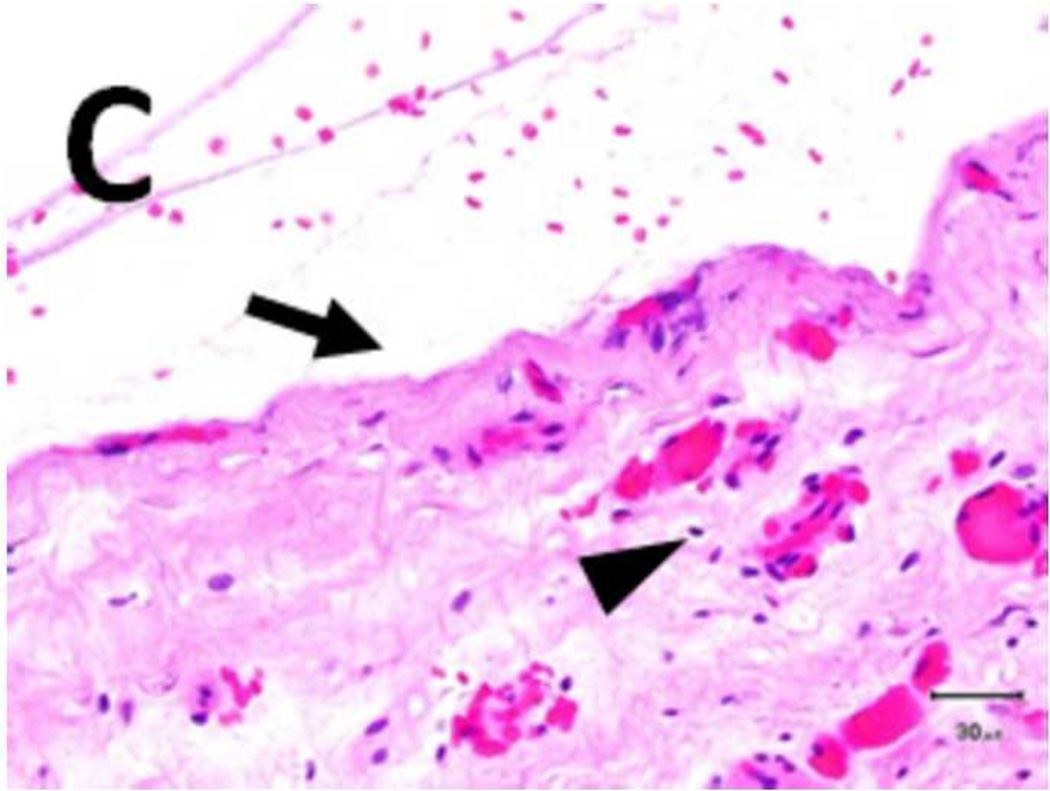

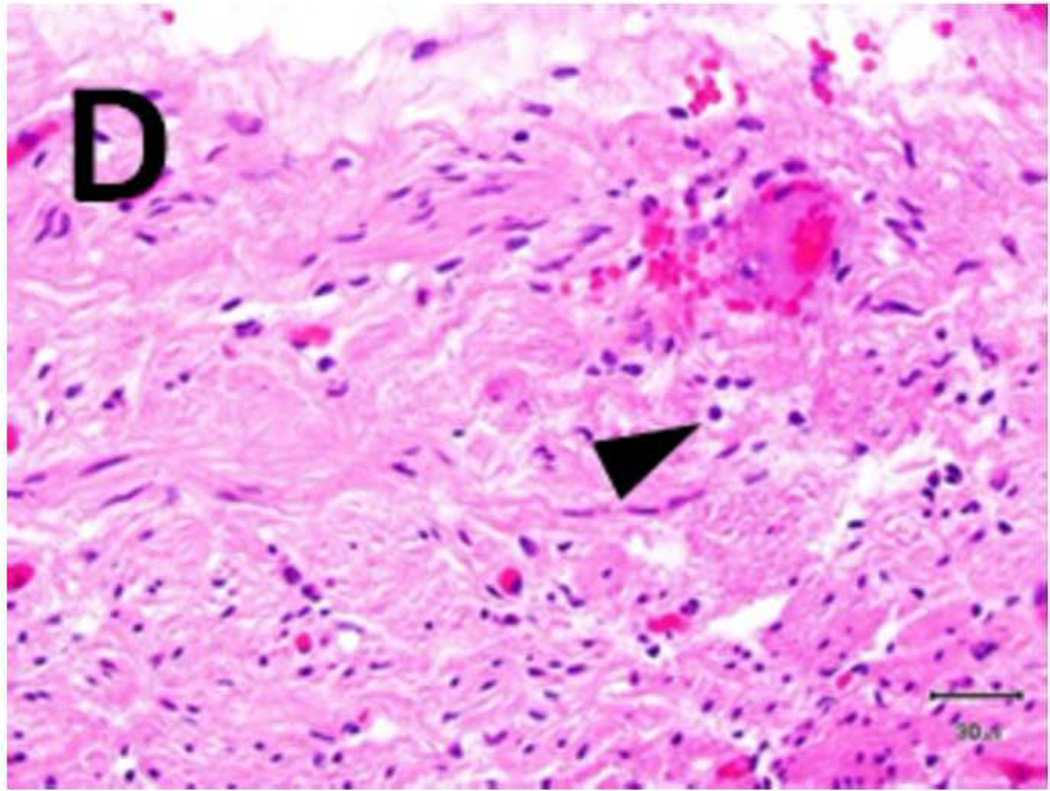

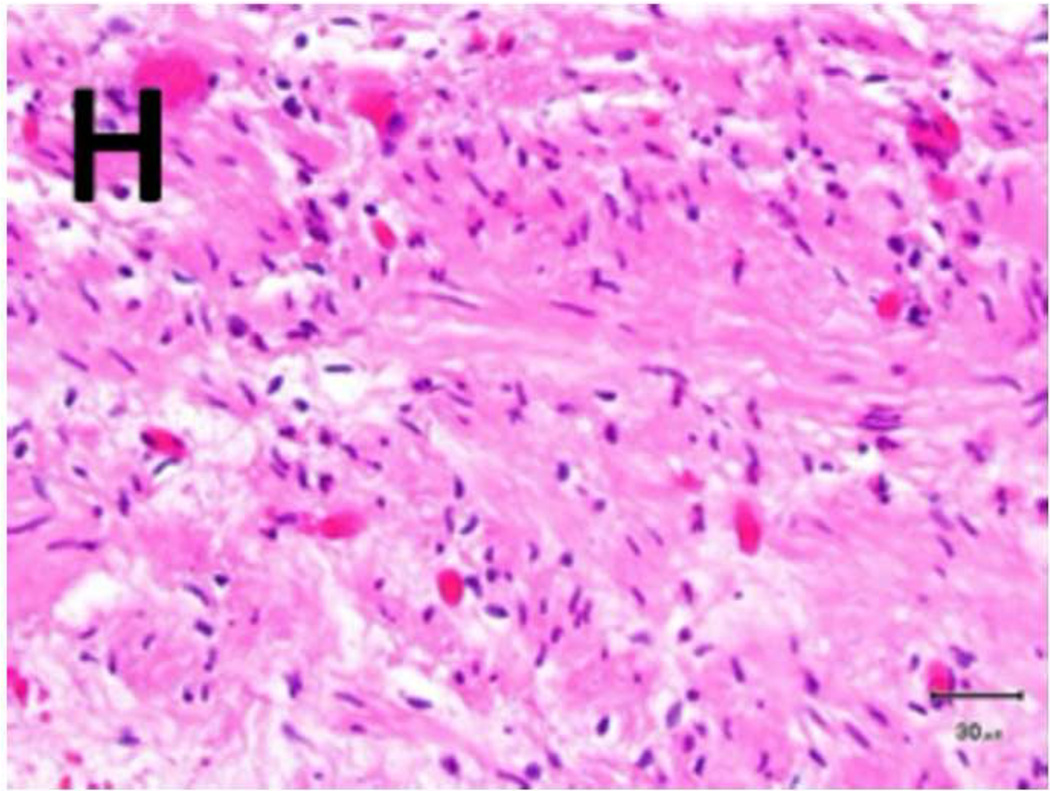

Figure 4. H&E stain of treated and normal ureter.

A and C) Low magnification (original magnification 20×, scale bar: 1mm) cross-sectional image of treated and normal ureteral wall respectively. B) High magnification (100×, scale bar 200 µm) of region from A (asterisk) showing treated ureter with evidence of loss of urothelium (arrowhead), edema (asterisk) and hyperemia (arrow). D) High magnification (100 ×, scale bar: 200 µm) image of normal ureter from C (arrowhead).

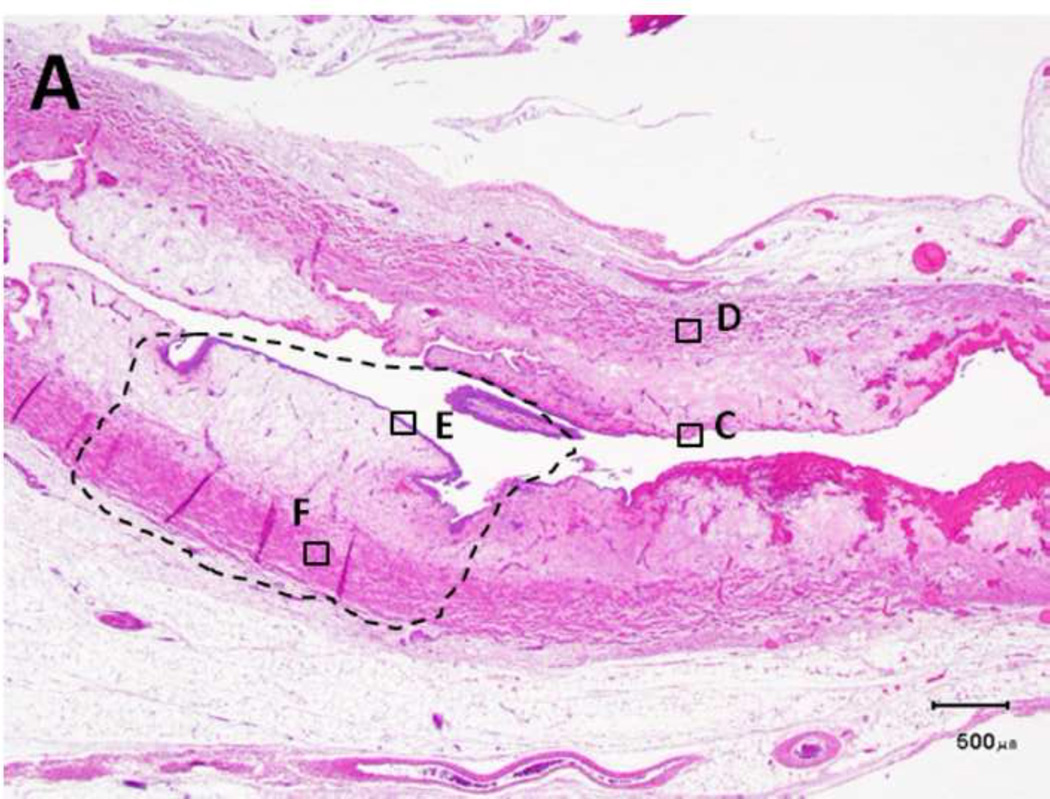

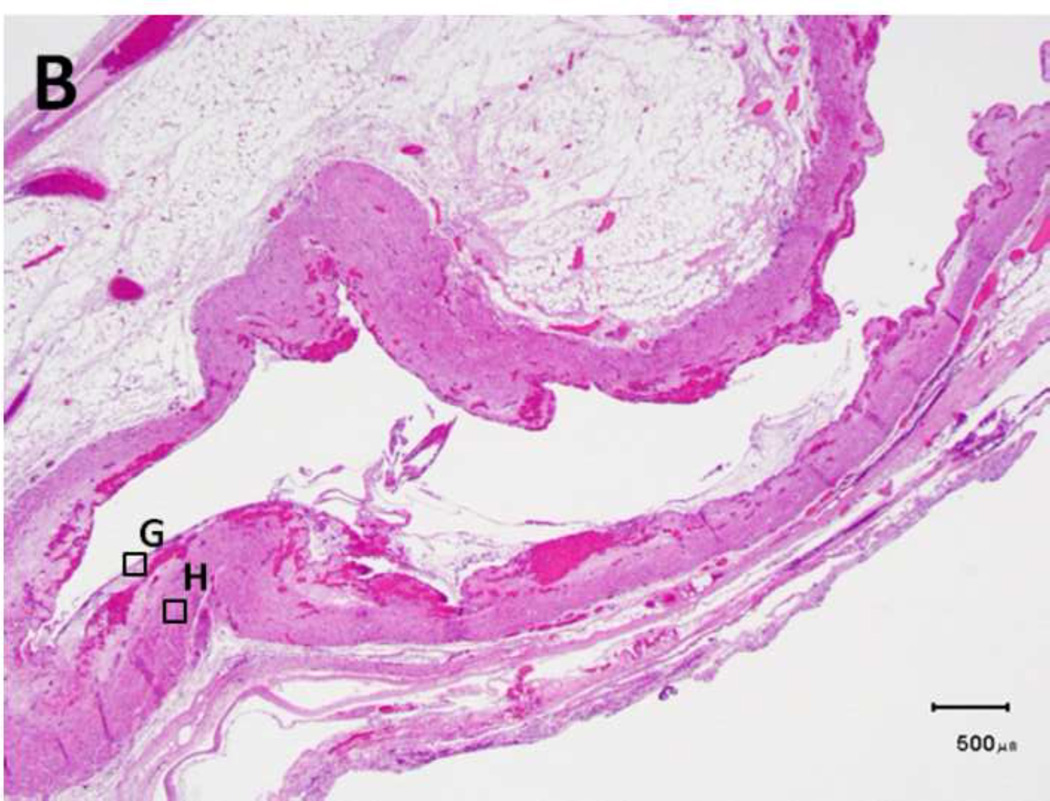

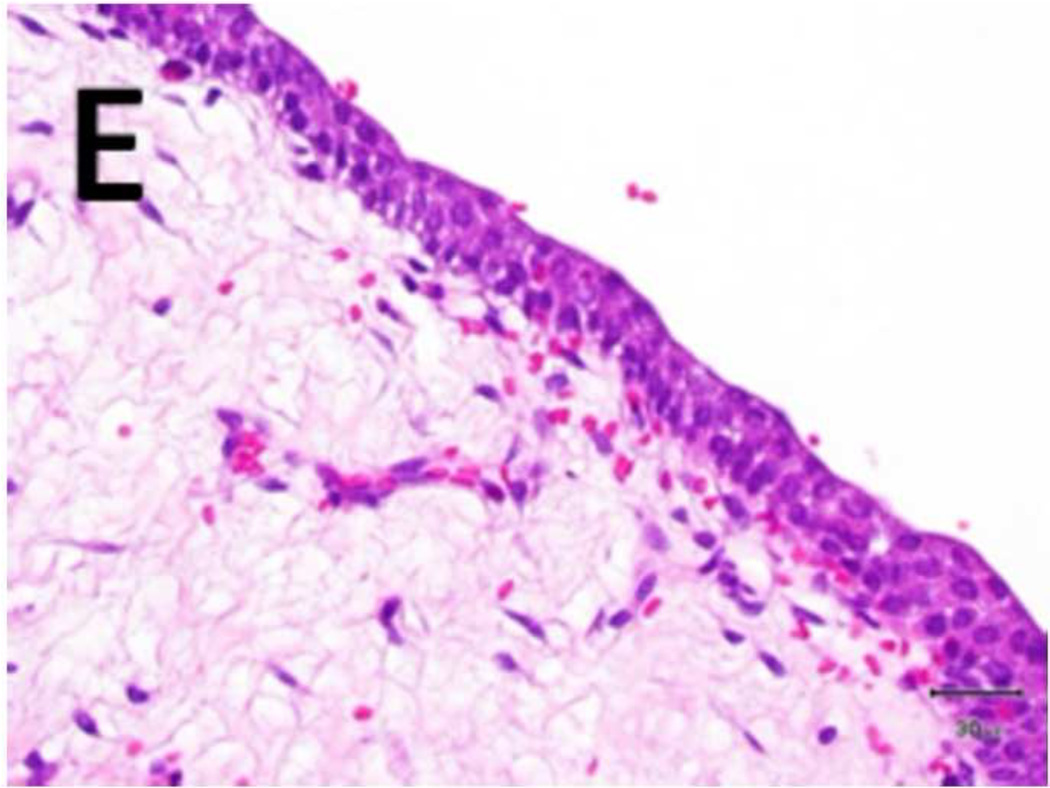

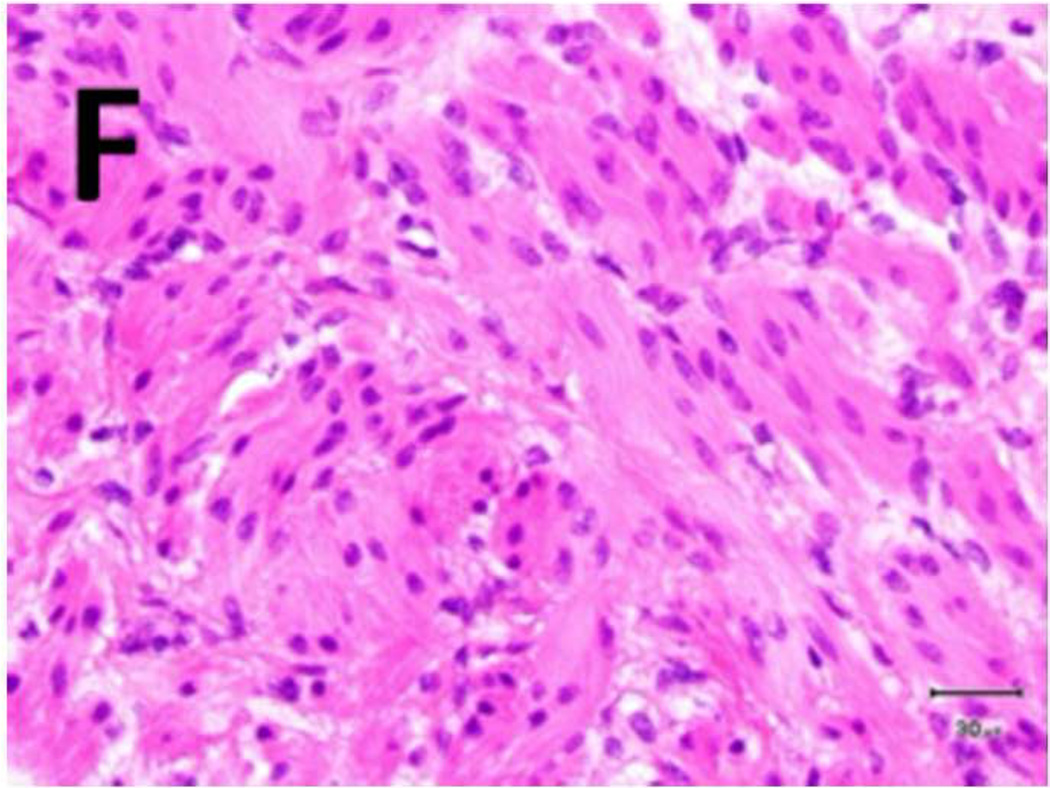

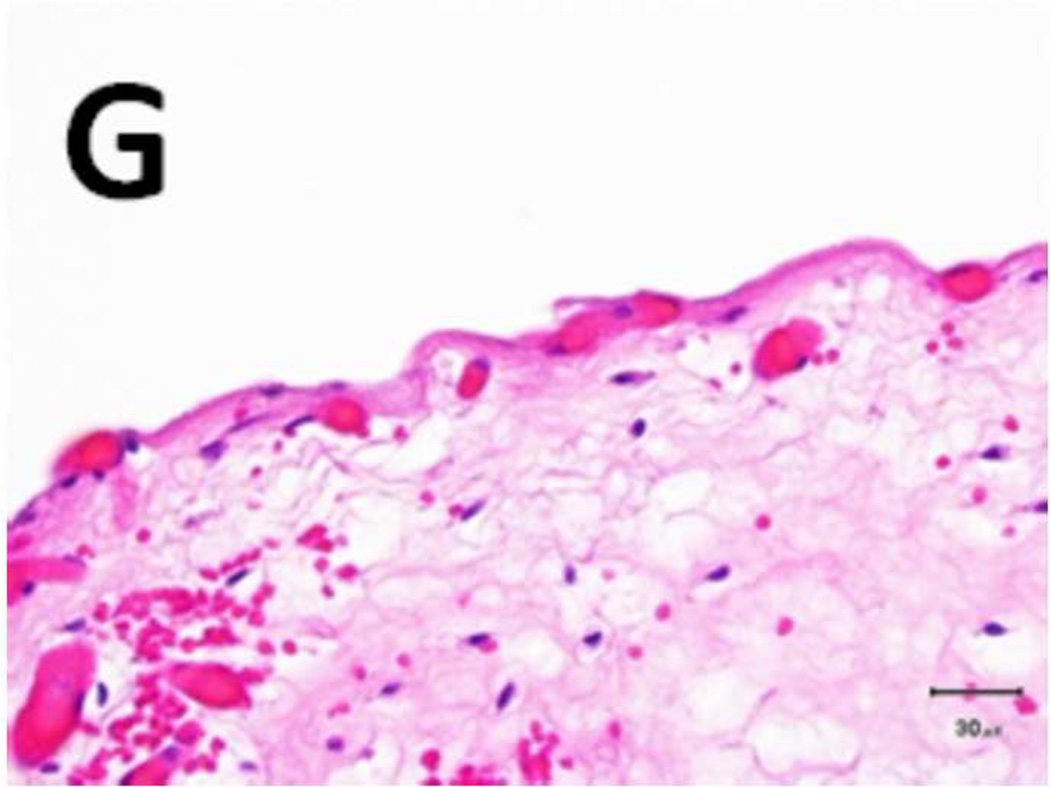

Figure 5. Schema used for quantifying necrosis in different layers in treated ureters.

A) Shows a sample with an ablation zone with a score of 3 (area of cells death in ablation zone is >50% and < 100%). All tissues show evidence of cell death except for the contoured area in which all layers were viable. Labeled boxes indicate magnified areas in C: (ablated utothelium and lamina propria), D: (ablated muscularis), E: (viable urothelium and lamina propria) and F: (viable muscularis). Cell death is characterized by loss of urothelium (arrow in C) and are nuclear shrinkage in lamina propria and muscularis (pyknosis, arrowhead in C and D). B) Shows a sample with an ablation zone with a score of 4 (area of cells death in ablation zone is 100%). All tissues showed evidence of cell death. Labeled boxes indicate magnified areas in G: (ablated utothelium and lamina propria), H: (ablated muscularis). Original magnifications: 20 × in A, B, 400× in C, D, E, F, G, H. Scale bars: 500 µm in A, B, 30 µm in C, D, E, F, G, H.

Table 2.

Quantification of the extent of necrosis observed in each layer of the ureter in response to evaluated treatment settings

| Treatment Setting (V) |

Extent of Necrosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urothelium | Lamina Propia | Muscularis | Adventitia | |

| 1000 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1500 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 2000 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 2500 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| 3000 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

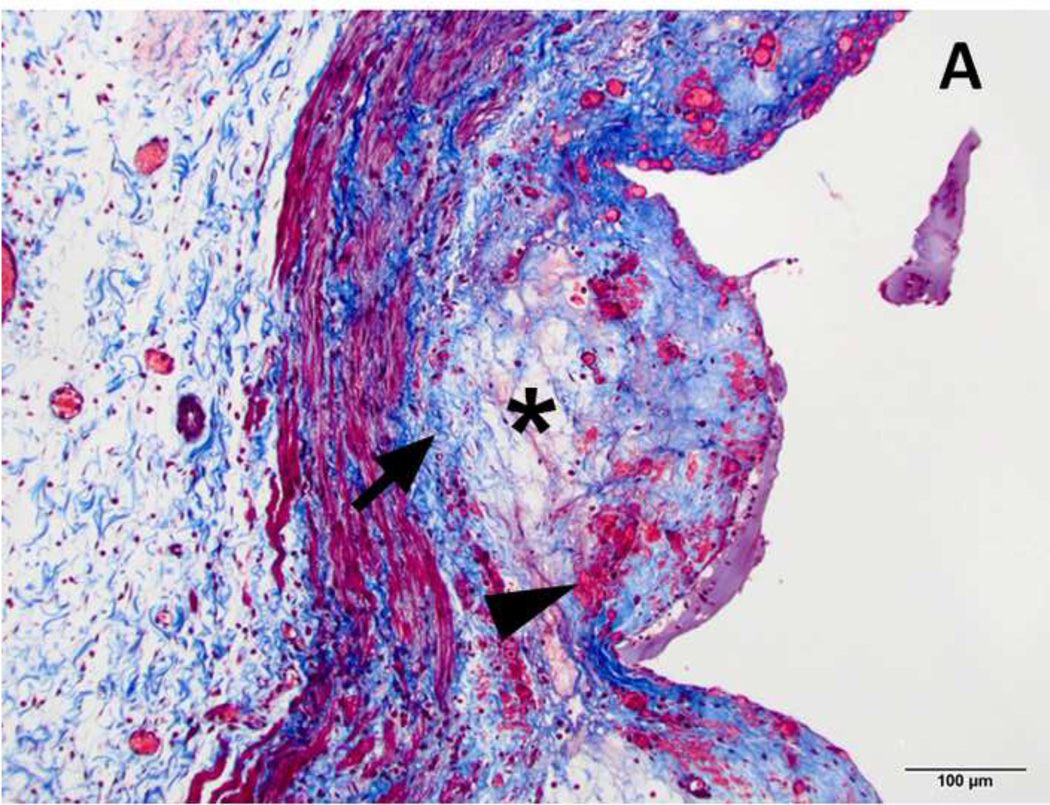

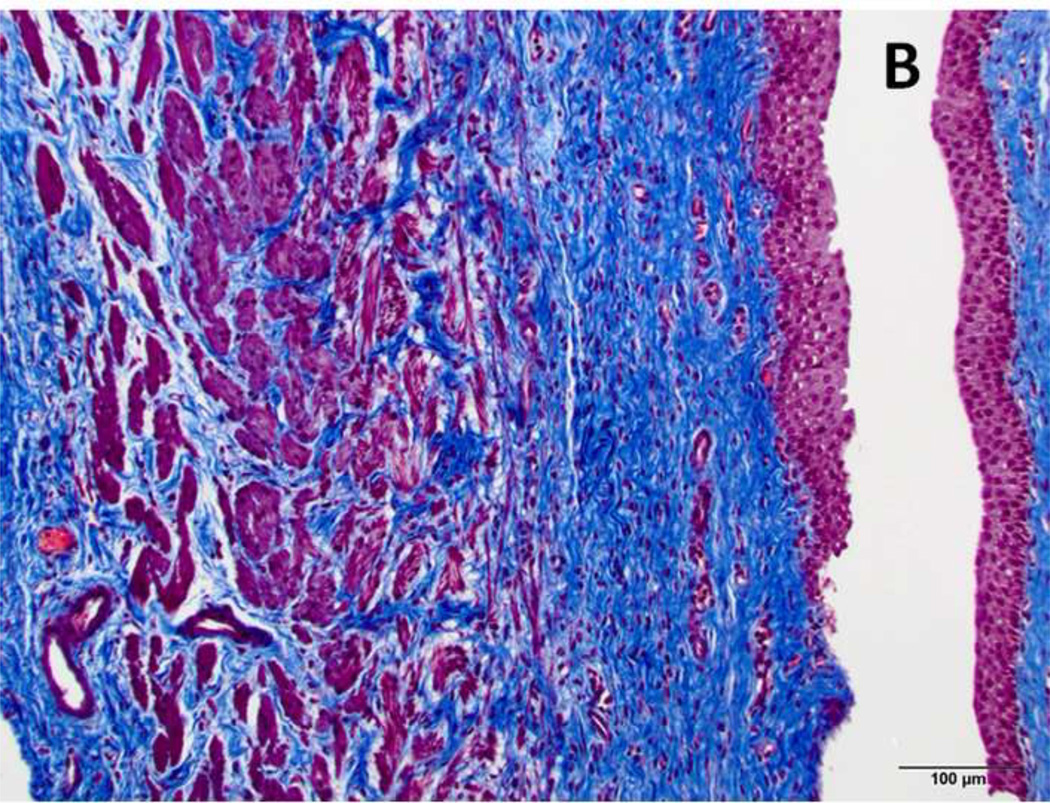

Figure 6. Masson Trichrome stain of treated and normal ureter.

(A) Blue staining collagen fibers (arrow), are separated by edema (asterisk) and hemorrhage (arrowhead). These changes are not observed in normal control (B). Original magnification: 200×, scale bar: 100 microns.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the feasibility of fluoroscopy guided catheter directed IRE of the ureteral wall in a large animal model. Treated ureters demonstrated histological evidence of cell death through the full thickness of the ureteral wall, with preservation of collagen fibers in the extracellular matrix. These findings are consistent with similar preservation observed and reported following needle directed IRE of solid organs (13,14,15). The treatment effect penetrated all layers at the treatment settings evaluated in the study, but caused transmural necrosis and injury to the muscularis at settings of 2000V or higher. This is an important consideration for future studies as injury to complete necrosis of the muscularis could increase chances of stricture formation. The voltage range utilized in this study corresponds to typical voltages used in clinical practice. IRE treatment of the ureter, even at maximum energy settings, did not cause lumenal perforation in the immediate post-procedure setting. Analysis of the untreated tissue immediately adjacent to the treated regions did not offer evidence of injury from device placement. Gross tissue measurements suggested that dimensions of visually observable ablation zones matched electrode dimensions, regardless of the treatment settings used.

Compared to needle directed IRE, catheter directed IRE has some significant advantages when treating intraluminal tumors. Treatments delivered with IRE require close proximity with the exposed portion of the electrode. Due to the anatomy of tubular structures such as ureters or bile ducts, optimal needle positioning for IRE is challenging. Endoluminal catheter placement can be confirmed visually with commonly used endoscopic techniques or fluoroscopy. Catheter directed IRE may therefore reduce the risks related to needle insertion to surrounding organs and circumvent difficulties in accurate needle placement stemming from respiratory motion.

Laser therapy and electro-diathermy are the predominant ablative therapies used focal treatment of urothelial cancer in the upper urinary tract. Best results with focal ablation are reported in patients with very early and low stage disease. Laser treatment of patients with higher grade disease carries significant risk of recurrence (31–65%), and deeper tissue penetration is accompanied with higher risk of stricture formation (20). These risks primarily arise because of the thermal mechanism of laser therapy, where deeper penetration for better outcomes is difficult to achieve while maintaining a good safety profile. The development of catheter directed IRE therapy may surmount some of these problems.

Postprocedural imaging suggested that all treated ureters maintained lumen integrity and patency until the designated endpoint of the experimental protocol. Pathologist analysis of H&E stained tissues samples consistently suggested transmural ablation of the ureteral wall. Sloughing of the urothelial layer was consistently observed in all treated tissue, but not in the adjoining healthy untreated tissue. This suggests urothelial injury and sloughing as a direct consequence of the ablation and not from electrode alone. Therefore, catheter directed IRE has potential as an alternative treatment modality for upper tract urothelial carcinomas. Furthermore, Masson Trichrome stains for collagen in the extracellular matrix indicate relative morphologic preservation, likely accounting for all ureters remaining intact and functional. While there is some debate on the thermal aspects of IRE, at the current stage we are unable discern between thermal and non-thermal injury to the ureter. The small size of the ureter and the construction of our electrode catheter makes it difficult to directly monitor tissue temperature during treatment delivery. Instead, we computed the energy deposited during treatment using the voltage-current measurements taken during pulse delivery. The energy deposited during treatment varied from 80J for treatments at 1000V to 520J for treatments delivered at 2500V. While these energy values by themselves are not substantial, it must be noted that the energy was deposited in a very short period of time (90 seconds) in a small volume of poorly perfused tissue. These considerations lead us to suspect thermal effects with IRE of the ureter, especially when performed at higher voltages. However, lack of sufficient data does not allow us to form any firm conclusions. There were some limitations in this study. We conducted our experiments on normal swine ureters rather than utilizing a tumor model. IRE’s ability to ablate tumor tissue may require different device settings and have different effects on tissue integrity. This study focused on the feasibility of catheter directed IRE in the ureter and application to other tubular structures such as bile ducts, airways, or gastrointestinal tract may require alterations in treatment devices and parameters. Longer-term studies are needed to elucidate the effects of healing and regeneration on ureter function and patency. In both an acute and chronic study on IRE ablation of nerves, Schoellnast et al described loss of function due to nerve cell death with intact endoneurium (16). While signs of nerve regeneration were observed, none of the animals regained full function after 2 months. While smooth muscle has been reported to be able to regenerate following injury (17,18), this process may take 2–3 months for the healing process to complete even in small lesions. It is unclear what the effect of a denuded segment of ureter would have over a longer healing period.

In summary, intraluminal delivery of IRE is feasible using a catheter-mounted device and can achieve full thickness circumferential ablation in a normal swine ureter

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources:

The project was supported by a philanthropic grant from the Thompson Foundation. The authors acknowledge the support of NIH Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748) for core laboratory services that were used for the presented work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The research in this manuscript was presented as a talk in the 2013 Society of Interventional Radiology Annual meeting in New Orleans.

References

- 1.Deodhar A, Monette S, Single GW, Jr, et al. Renal tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation: preliminary results in a porcine model. Urology. 2011;77:754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendler JJ, Porsch M, Hühne S, Baumunk D, Buhtz P, Fischbach F, et al. Short- and mid-term effects of irreversible electroporation on normal renal tissue: an animal model. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:512–520. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0452-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommer CM, Fritz S, Wachter MF, et al. Irreversible electroporation of the pig kidney with involvement of the renal pelvis: technical aspects, clinical outcome, and three-dimensional CT rendering for assessment of the treatment zone. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:1888–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olweny EO, Kapur P, Tan YK, Park SK, Adibi M, Cadeddu JA. Irreversible electroporation: evaluation of nonthermal and thermal ablative capabilities in the porcine kidney. Urology. 2013;81:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wimmer T, Srimathveeravalli G, Gutta N, et al. Planning irreversible electroporation in the porcine kidney: are numerical simulations reliable for predicting empiric ablation outcomes? Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014 May 17; doi: 10.1007/s00270-014-0905-2. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wendler JJ, Pech M, Porsch M, et al. Urinary tract effects after multifocal nonthermal irreversible electroporation of the kidney: acute and chronic monitoring by magnetic resonance imaging, intravenous urography and urinary cytology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:921–926. doi: 10.1007/s00270-011-0257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pech M, Janitzky A, Wendler JJ, et al. Irreversible electroporation of renal cell carcinoma: a first-in-man phase I clinical study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011:132–138. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheffer HJ, Nielsen K, de Jong MC, et al. Irreversible electroporation for nonthermal tumor ablation in the clinical setting: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:997–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silk MT, Wimmer T, Lee KS, et al. Percutaneous ablation of peribiliary tumors with irreversible electroporation. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayanan G, Hosein PJ, Arora G, et al. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation for downstaging and control of unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1613–1621. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin RC, 2nd, McFarland K, Ellis S, Velanovich V. Irreversible electroporation therapy in the management of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niessen C, Jung EM, Schreyer AG, et al. Palliative treatment of presacral recurrence of endometrial cancer using irreversible electroporation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:128. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-David E, Ahmed M, Faroja M, et al. Irreversible electroporation: treatment effect is susceptible to local environment and tissue properties. Radiology. 2013;269:738–747. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee EW, Chen C, Prieto VE, Dry SM, Loh CT, Kee ST. Advanced hepatic ablation technique for creating complete cell death: Irreversible electroporation. Radiology. 2010;255:426–433. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charpentier KP, Wolf F, Noble L, Winn B, Resnick M, Dupuy DE. Irreversible electroporation of the liver and liver hilum in swine. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoellnast H, Monette S, Ezell PC, et al. The delayed effects of irreversible electroporation ablation on nerves. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:375–380. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2610-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorham SD, French DA, Shivas AA, Scott R. Some observations on the regeneration of smooth muscle in the repaired urinary bladder of the rabbit. Eur Urol. 1989;16:440–443. doi: 10.1159/000471636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehman J, Ragab MM, Venkatesh R, et al. Smooth-muscle regeneration after electrosurgical endopyelotomy in a porcine model as confirmed by electron microscopy. J Endourol. 2004;18:982–988. doi: 10.1089/end.2004.18.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cutress ML, Stewart GD, Zakikhani P, Phipps S, Thomas BG, Tolley DA. Ureteroscopic and percutaneous management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC): systematic review. BJU Int. 2012 Sep;110(5):614–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bader MJ, Sroka R, Gratzke C, Seitz M, Weidlich P, Staehler M, Becker A, Stief CG, Reich O. Laser therapy for upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma: indications and management. Eur Urol. 2009 Jul;56(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]