Abstract

The transition from late childhood through middle adolescence represents a critical developmental period during which there is a rapid increase in the initiation and escalation of alcohol use. Alcohol use is part of a constellation of risk taking behaviors that increase during this developmental transition, which can be explained by environmental and genetic factors. Social learning theory (SLT) implicates observations of parental drinking in the development of alcohol use in youth. Parental risk taking more broadly has not previously been examined as a factor predictive of alcohol use escalation in youth across adolescence. The current study examined the relative contributions of maternal risk taking on the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) and maternal alcohol use in the prediction of alcohol escalation among youth over three years. Participants were a sample of 245 youth (55.0% male, 49.6% Caucasian) who participated annually between Grades 8 and 10, drawn from a larger study of adolescent risk-taking. Within our sample, maternal risk taking, as measured by the BART, predicted increases in alcohol use. Interestingly, maternal alcohol use and other youth factors were not predictive of escalations in youth alcohol use. Our findings suggest the importance of considering maternal riskiness more broadly, rather than solely focusing on maternal alcohol use when attempting to understand youth alcohol use across adolescence. These findings emphasize the relevance of maternal risk taking as measured by a behavioral task and suggest a general level of riskiness displayed by mothers might encourage youth to behave in a riskier manner themselves.

Keywords: alcohol use escalation, risk taking, Balloon Analogue Risk Task, mothers

1. INTRODUCTION

The transition from late childhood through middle adolescence represents a critical developmental period during which there is a rapid increase in the initiation and escalation of alcohol use. Although some alcohol use during adolescence is normative (Faden, 2006), youth who drink have an increased likelihood of engaging in risky sex behaviors (Mason et al., 2010), having accidents and injuries (Bonomo et al., 2001), being victims of sexual assault (Champion, Foley, Durant, Hensberry, Altman, & Wolfson, 2004), having sleep problems (Huang, Ho, Lo, Lai, & Lam, 2013), and being aggressive (Maldonado-Molina, Jennings, & Komro, 2010). Further, elevated alcohol use during this period is associated with later impairments in mental and physical health, social functioning, and occupational functioning (Friedman, Terras, Zhu, & McCallum, 2004; McGue, Iacono, Legrand, & Elkin, 2001), as well as with problematic alcohol use in adulthood (Brown & Tapert, 2004; Hawkins et al., 1997; Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006; Masten, Faden, Zucker, & Spear, 2008). Given these negative effects, identifying risk factors predictive of increases in early alcohol use, which could be targeted within prevention and intervention programs, is a critical public health goal.

Alcohol use is part of a constellation of risk taking behaviors that escalate during adolescence. More generally, risk taking behaviors like substance use, delinquent behaviors, risky sexual behaviors, and risky driving frequently co-occur (Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1994; Mishra & Lalumière, 2009; Mishra, Lalumière, & Williams, 2010), suggesting there are common factors predictive of their emergence (Zuckerman, 2007). Environmental and genetic factors are thought to underlie youth substance use behaviors, with environmental factors playing a stronger role earlier in development and genetic factors coming online later in adolescence (Baker, Maes, Larrson, Lichtenstein, & Kendler, 2011). One theory suggesting how environmental factors might influence youth substance use is social leaning theory (SLT; Bandura, 1986), which suggests risk taking behaviors like substance use emerge when youth mimic parental patterns of risk taking (e.g., Bandura, 2004; Hardburg, Davis, & Kaplan, 1982; White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000). Here, youth observe parental risk taking behaviors, as well as the consequences of these behaviors, which influences their beliefs about the costs and benefits of risk taking (Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). Social learning theory has been used to explain links between maternal substance use and female offspring use (e.g. Denton & Kampfe, 1994; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007), parental drinking/tobacco use and offspring use of these substances (Richter & Richter, 2001), and maternal risky sex and risky sexual activity in offspring (Bonell et al., 2006; Brakefield, Wilson, & Donenberg, 2012; Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2010). Thus, SLT can help to explain how youth learn about and mimic parental patterns of risk taking.

Although SLT suggest youth learn about specific risky behaviors (e.g., risky sex, substance use) by observing their parents, it is possible this learning generalizes to risk taking more broadly. Specifically, youth might be more likely to engage in a variety of risky behaviors after observing their parents behave in a risky manner across contexts. Related to this, research demonstrates youth whose parents are risky across multiple contexts are more likely to behave in a risky manner themselves (Wilder & Watt, 2002), suggesting parental riskiness more broadly predicts youth risk taking behaviors. Thus, to better understand how parental riskiness affects youth alcohol use, it would be helpful to examine the effects of parental riskiness, within a controlled laboratory setting, on self-reported youth drinking. Because parental risk taking varies across contexts, it is difficult to ascertain its impact on youth drinking. Following from this, it is possible a more generalized measure of parental riskiness could provide a proxy for real-world parental risk taking behaviors youth observe across contexts. This perspective allows us to move beyond somewhat reductive theories that merely tie observations of parental alcohol consumption to youth consumption, by discussing the influence of generalized parental riskiness across contexts.

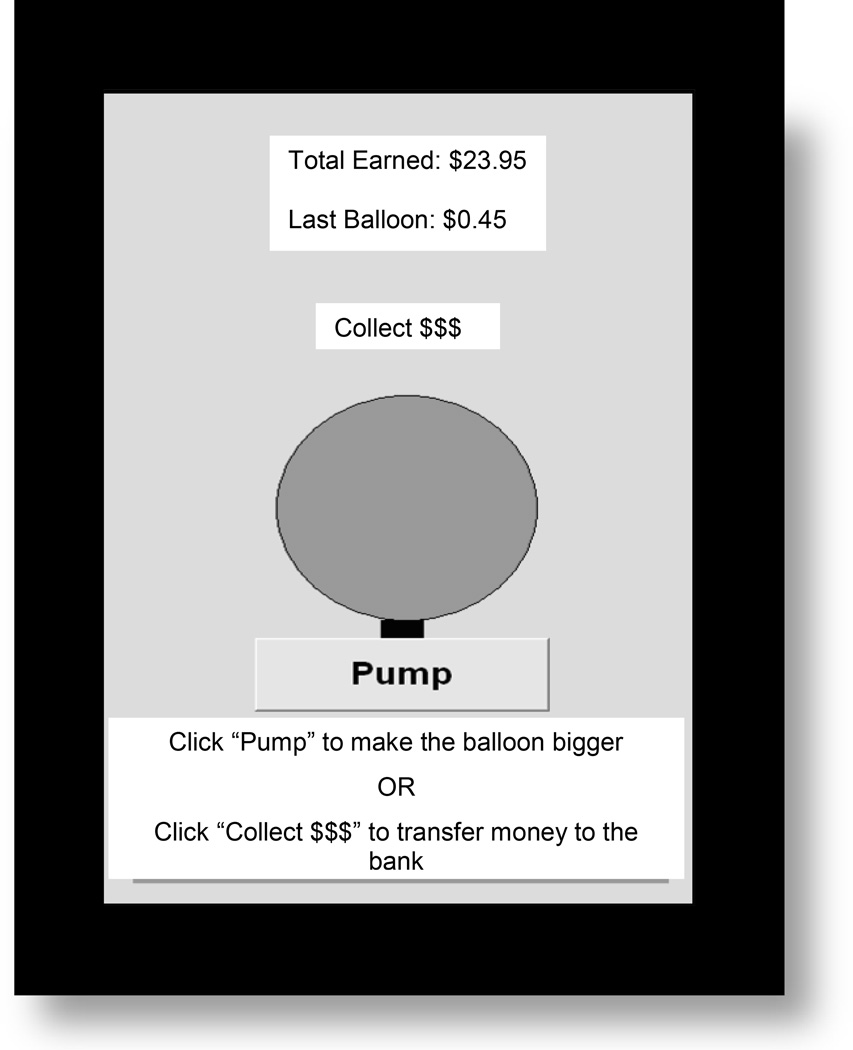

One potential tool for gauging parental risk taking within the laboratory is the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART), a computerized assessment of risk taking propensity (Hopko et al., 2006; Lejuez et al., Gwadz, 2007; Lejuez, Aklin, Zvolensky, & Pedulla, 2003; Lejuez et al., 2002). On the BART, participants inflate a series of 60 animated balloons. The more an individual balloon is inflated, the more money a participant earns, with the caveat that all money earned for a given balloon will be lost if the balloon is inflated too much and explodes. Thus, the task is able to determine participants’ likelihood of behaving in a risky manner by measuring the average number of pumps balloons are inflated in the context of earning monetary rewards (see Method). Importantly, performance on the BART is associated with substance use, psychopathy, and risky sex among adults (e.g., Hopko et al., 2006; Hunt, Hopko, Bare, Lejuez, & Robinson, 2005; Lejuez et al., 2002), suggesting it captures adults’ likelihood of behaving in a risky manner across contexts. Thus, BART scores can serve as a proxy of individuals’ general riskiness across multiple contexts.

To determine whether general level of parental riskiness on the BART could inform our understanding of youth drinking above and beyond actual parental drinking behaviors, it is necessary to compare the relative effects of both on youth drinking across development. Thus, the current study sought to examine the effects of parental risk taking on the BART, while taking parental drinking into account, in predicting the trajectory of youth alcohol use across three years. For added control, we examined youth alcohol use expectancies to ensure youths’ positive beliefs about alcohol use did not solely predict outcomes. In line with previous research examining the effects of maternal behaviors on youth outcomes (Bonell et al., 2006; Brakefield et al., 2012; Cavazos-Rehg et al., 2010; Denton & Kampfe, 1994; Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007), we hypothesized maternal risk taking, as measured by the BART, would predict youth drinking behaviors, such that youth of mothers with elevated risk taking on the BART would have the greatest increases in alcohol consumption across the three annual assessments.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

Participants were a convenience sample of 277 youth, recruited from the Washington D.C. metropolitan area (55.0% male, 49.6% Caucasian), taking part in a larger, longitudinal study of mechanisms for HIV-related risk behaviors (see Table 1). The study recruited English proficient 9–13 year-old community youth and their families; no other inclusion criteria were used. Details of the larger longitudinal study are reported elsewhere (Daughters et al., 2009; MacPherson, Magidson, Reynolds, Kahler, & Lejuez, 2010). Youth and their parents (94% biologically related) completed six annual assessments; data from the current study includes children who participated in grades 8 through 10, because a comprehensive alcohol assessment was conducted during these years. All participants were invited to take part in each wave of data collection, regardless of their participation at previous waves (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Data

| Factor | Grade 8 | Grade 9 | Grade 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | N = 185 | N = 198 | N = 160 |

| Past Year Youth Alcohol Use1 | 3.24 (11.53) | 3.48 (8.87) | 5.21 (11.79) |

| Age | 13.12 (0.56) | 14.10 (0.55) | 15.12 (0.56) |

| Sex | 55.0% male | ||

| Maternal BART Score2 | 34.62 (12.90) | ||

| Positive Alcohol Expectancies | 9.75 (3.09) |

. “Past year youth alcohol use” is the total number of alcoholic beverages youth reported consuming during the past year.

. “Maternal BART Score” is the adjusted average pumps score on the BART for mothers. The adjusted average pumps score is the mothers’ average number of pumps on un-popped balloons across the 60 balloon trials.

2.2. Procedure

At each assessment, study procedures and confidentiality were separately described to parents and youth; informed consent and assent were obtained. Youth and their parents were administered all measures in separate private rooms. Parents provided demographics, including age, gender, and race/ethnicity about themselves and their child. Parents and youth were compensated for study participation. The University of Maryland Institutional Review Board approved study procedures.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Mother and adolescent alcohol use

We used a modified version (Aklin, Lejuez, Zvolensky, Kahler, & Gwadz, 2005) of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001) to assess past year alcohol use at each assessment among youth. Youth were asked to report how many alcoholic beverages in total they had consumed over the prior year. The number of alcoholic beverages youth reported consuming increased over time (see Table 1).

Participants’ mothers also reported on their own alcohol usage. Since we assumed it would be difficult for mothers to accurately report the total number of drinks they had consumed during the prior year, we asked about their average frequency of past year alcoholic beverage consumption. Options (and percent endorsed) for past year alcohol consumption were “zero” (26.0%), “once” (8.1%), “monthly or less” (22.5%), “2–4 times a month” (20.2%), “2–3 times per week” (13.9%), and “four or more times a week” (9.2%).

2.3.2. Positive Alcohol Expectancies

Youths’ positive alcohol expectancies were measured during the third annual assessment using the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire – Adolescent Brief (AEQ-AB; Stein et al., 2007), a seven-item measure with two subscales: General Positive Effects and Potential Negative Effects. Youth rated the extent to which they agreed on statements like: “alcohol helps a person relax, feel less tense, and can keep a person’s mind off mistakes at school or work.” Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Disagree Strongly) to 5 (Agree Strongly). The AEQ-AB is internally reliable and valid when used with adolescent samples (Stein et al., 2007). Given current research suggesting a link between positive alcohol expectancies and increased frequency of use and early initiation (Cable & Sacker, 2007; Coleman & Cater, 2004; Zamboanga, Schwarts, Ham, Hernandez Jarvis, & Olthuis, 2009), we utilized the positive expectancy scale.

2.3.3. Mother’s risk taking propensity

We used the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART; Lejuez et al., 2002) to measure maternal risk taking propensity. The BART consisted of 60 balloon trials. Mothers were presented with a balloon and were prompted to “pump” the balloon to earn money (see Figure 1). On each of the 60 balloon trials, the number of points earned per pump varied, with 20 balloons having a low value (0.5 cents per pump), 20 balloons having a medium value (1.0 cents per pump), and 20 balloons having a high value (5.0 cents per pump). Mothers were informed the more they pumped, the more money they could earn, with the caveat that popping a given balloon would cause them to lose all money accrued for that balloon. Each balloon was programmed to pop between 1 and 128 pumps, with an average breakpoint of 64 pumps; this information was not provided to the mothers. Mothers were informed they could stop pumping a balloon and click “Collect $$$” at any point during each balloon trial, thereby transferring money accrued from a given balloon to the permanent bank. When mothers pumped a balloon too much and it exploded, a “pop” sound was heard, the balloon image popped, the money in the temporary bank was lost, and the next trial began. As in previous studies, we used the average number of pumps (range 11–82) across trials on balloons that did not explode (Lejuez et al., 2002) as our measure of risk taking.

Figure 1. Balloon Analogue Risk Task.

2.4. Analyses

Latent growth modeling (LGM), a case of structural equation modeling, was used to examine trajectories of child alcohol use over time in Mplus 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). We utilized full information maximum likelihood estimation methods to handle missing data, which provides less biased parameter estimates than listwise or pairwise deletion, under the missing at random assumption (Little & Rubin, 1987). Utilizing this approach also allowed us to include data from all participants who were assessed at some point during the longitudinal data collection. LGM estimates means and variances for a latent baseline (intercept) and change over time (slope). To estimate these models, regression weights from each manifest variable to the latent intercept are set at 1.0. Regression weights for the slope factor define the shape of the trajectory over time and are fixed to identify the model. Specifically, the loadings were set to 0.0, 1.0, and 2.0 for each Wave of the alcohol use measure, respectively. Error variances and intercept-slope correlations were allowed to be freely estimated. Several fit indices were used to evaluate the fit of the model, including the χ2 statistic, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI, Tucker & Lewis, 1973) and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990). Good fit was indicated by CFI and TLI values ≥ .90, RMSEA values ≤ .08, and nonsignificant chi-square values (Schweizer, 2010).

We first examined an unconditional model of alcohol use to determine whether quantity of alcohol consumed increased over development. We then utilized a model building approach to determine whether potential covariates were associated with youth alcohol use. Finally, we added mothers’ BART scores and mothers’ alcohol use frequency as predictors of the latent intercept and slope, while controlling for significant demographic covariates and youths’ positive alcohol use expectancies.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Means and standard deviations of key study variables are included in Table 1. Table 2 presents correlations between past year quantity of youth alcohol use at the three assessment points and all major study independent variables. Data were next examined to ensure they met the criteria for univariate normality. All skew and kurtosis statistics appeared to be in the acceptable range, with the exception of the youth alcohol use variable, which was positively skewed. We transformed the data by adding a constant and taking the natural log of each alcohol use value at the three assessment points and then re-assessed the descriptive statistics. The new distributions were within the acceptable bounds for skew and kurtosis and used throughout the following analyses.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix (N = 245)

| Youth Gender |

Youth Age |

Grade 8 Alcohol |

Grade 9 Alcohol |

Grade 10 Alcohol |

Y2 Mom BART |

Y3 Mom Alcohol |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Gender1 | ____ | ||||||

| Youth Age | .05 | ____ | |||||

| Grade 8 Alcohol2 | .15* | .04 | ____ | ||||

| Grade 9 Alcohol | .09 | .10 | .48** | ____ | |||

| Grade 10 Alcohol | .08 | −.05 | .84** | .47** | ____ | ||

| Maternal BART2 | −.15 | .05 | −.03 | .06 | .13 | ____ | |

| Maternal Alcohol3 | −.14* | −.22** | .07 | .17* | .18* | .00 | ____ |

| Grade 8 AEQ | .00 | .13 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .07 | −.06 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01.

Phi coefficients are reported for correlations within dichotomous variables. Otherwise, Pearson correlations are presented. AEQ-AB POS = Alcohol Expectancies Questionnaire – Adolescent Brief Version, Positive Expectancies.

. Gender is dichotomized as female = 0, male = 1.

. Maternal BART is the adjusted average pumps score on the BART for mothers. The adjusted average pumps score is the mothers’ average number of pumps on un-popped balloons across the 60 balloon trials.

. Maternal Alcohol is the frequency of past year drinking for mothers. Options for past year alcohol use on the assessment mothers completed were “zero”, “once”, “a few times”, “1–3 times per month”, “1–3 times per week”, and “almost every day or more.”

3.2. Unconditional Growth Model

First, we tested an unconditional latent growth curve model to examine trajectories of youth alcohol use. The unconditional model fit the data extremely well: χ2(df=1) = .759, p = 0.38; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 (90% CI = 0.00 – 0.16). Both the mean of the intercept (M = .70, SE = 0.06, p < .001) and the slope (M = 2.08, SE =0.04, p < .001) were significant, suggesting that baseline alcohol use was different from zero and that number of drinks increased across adolescence. The correlation between intercept and slope was not significant (r = .04, p = .63), however, suggesting that drinking at grade 8 did not predict changes in alcohol use over time.

3.3. Conditional Model 1: Demographic Predictors

Next, we tested a model where we regressed covariates, including age, sex, race, and mothers’ education level onto the latent alcohol use intercept and slope. The model continued to fit the data well: χ2(df=5) = 5.56, p = 0.35; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.02 (90% CI = 0.00 – 0.10). Gender (Est. = 0.26, SE = 0.12, p = .039) and maternal education status (Est. = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p = .03) were associated with baseline alcohol use, such that boys and children whose parents attained higher levels of education reported drinking more than their peers. No demographic predictor was significantly associated with changes in drinking over time. Thus, we retained only gender and maternal education in our final model.

3.4. Conditional Model 2: Maternal Predictors

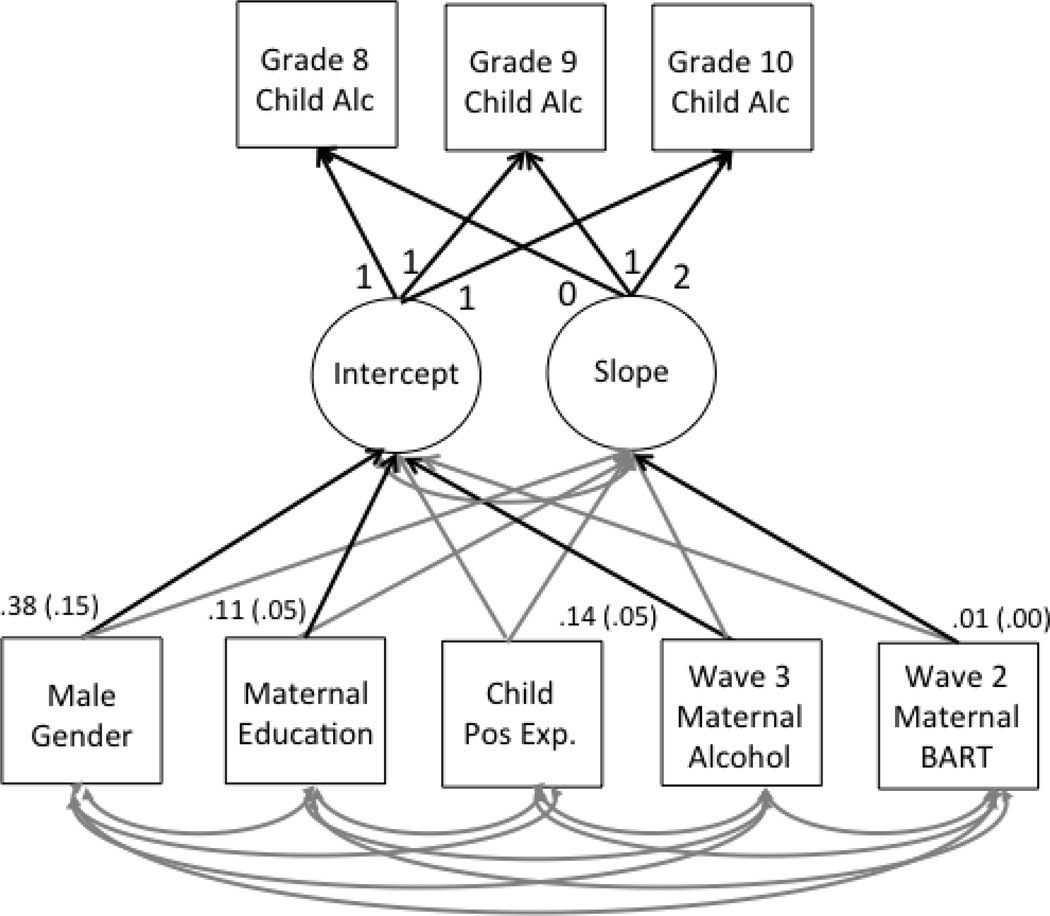

Lastly, we examined a model that included maternal risk taking on the BART as a predictor of youth alcohol use trajectories, controlling for youth report of positive alcohol expectancies and mother’s self-reported drinking behaviors (see Figure 2). This model also fit the data well: χ2(df=6) = 9.17, p = 0.16; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.06 (90% CI = 0.00 – 0.14). Gender (Est. = 0.35, SE = 0.15, p = .019), maternal education (Est. = 0.11, SE = 0.05, p = .016) and maternal history of drinking (Est. = 0.14, SE = 0.05, p = .004) were associated with baseline levels of youth alcohol use. Specifically, boys, children of mothers with higher educational attainment, and children with mothers who reported greater levels of prior drinking evidenced elevations in baseline alcohol use. Only maternal risk taking propensity on the BART (Est. = 0.01, SE = 0.004, p = .037) significantly predicted the slope, suggesting greater maternal risk taking on the BART was associated with greater increases in the quantity of youth alcohol use over time. Neither maternal drinking habits (Est. = −0.03, SE = 0.03, p = .373) nor youth-reported positive alcohol use expectancies (Est. = .01, SE = 0.02, p = .465) predicted changes in the quantity of alcohol youth consumed.

Figure 2. Final Conditional Latent Growth Model of Child Alcohol Use with Unstandardized Estimates and (Standard Errors) (N=245).

Note. Bold paths represent significant paths, grey paths represent non-significant paths. These are unstandardized estimates.

4. DISCUSSION

The extant literature on the relationship between parental and youth risk taking has primarily relied on self-report measures of specific parental and youth risky behaviors, while largely ignoring the broader construct of general parental risk taking as a predictor of youth alcohol use. In light of literature suggesting youth risk behaviors emerge as a result of viewing and subsequently mimicking general parental risk taking across a host of different situations (e.g., Bandura, 2004; Harburg, Davis, & Kaplan, 1982; White, Johnson, & Buyske, 2000), the reliance on self-report measures of specific parental risk behaviors is somewhat incomplete in understanding youth outcomes. The present study aimed to fill this gap by utilizing a laboratory-based assessment of maternal risk taking as a predictor of change in quantity of youth alcohol use over time. Results and their implications are discussed below.

Our findings suggest maternal risk taking on the BART is an important predictor of youth alcohol use escalation. These findings expand upon the existing literature, which demonstrates parental alcohol use is associated with earlier initiation, faster escalation, and more rapid transition from initiation to problematic use among offspring (e.g., Chassin, Curran, Hussong, & Colder, 1996; Hussong, Bauer, & Chassin, 2008; Hussong, Huang, Serrano, Curran, & Chassin, 2012) and suggest maternal riskiness more broadly is relevant to offspring alcohol use escalation. To better clarify these relations, it will be important to determine whether maternal riskiness is also associated with youth alcohol use outcomes beyond escalation. Since it is possible there are multiple common factors underlying both maternal risk taking on the BART and frequency of maternal alcohol use, it will be necessary to have larger adequately powered samples in future studies to be able to examine these patterns and determine whether SLT is the best explanation, or whether other factors might be more relevant. Indeed, it is possible both environmental and genetic factors could explain why maternal risk taking on the BART predicts youth alcohol escalation. Perhaps common genetic factors predict maternal and youth risk taking propensity, with observations of maternal riskiness amplifying these relations. Unfortunately, we did not have the capacity to examine genetic relations within the current study, which is an important future direction. However, as research demonstrates environmental factors are more relevant in predicting substance use than are genetic factors earlier in adolescence, SLT likely remains the strongest explanation for these findings (Baker et al., 2011).

There are multiple limitations of this study that must be taken into account when interpreting our findings. First, maternal risk taking on the BART was assessed only at one time point. Thus, we were unable to assess whether changes in maternal risk taking on the BART could explain changes in quantity of youth alcohol use. Second, our alcohol use variable was a single item measure for both mothers and children, with relatively low rates and frequencies of use over time. Thus, we are unable to draw conclusions regarding potential relationship between maternal risk taking on the BART and problematic levels of alcohol use among mothers and youth. Third, although our sample was sociodemographically diverse, it was a community-based convenience sample, which could limit the generalizability of findings. Fourth, because the majority of parental participants were mothers, we were unable to examine the role of paternal risk taking on the BART on youth alcohol use. Fifth, it is possible genetic factors underlie parental risk taking on the BART and resulting youth use, which we were unable to examine in the current study. Sixth, we lacked power to determine whether youth risk taking on the BART might have served as a mediator of the relations between maternal BART and youth drinking. Finally, it is possible we lacked power to detect the effects of both maternal risk taking on the BART and maternal alcohol use frequency on youth drinking. Despite these limitations, the current study provides a strong framework for elucidating the relationship between maternal risk taking on the BART and quantity of youth alcohol use across adolescent development.

There are a number of potential clinical implications of the current work that are relevant for prevention and intervention efforts. In regards to prevention, the present study suggests higher levels of maternal risk taking on the BART are predictive of greater escalations in youth alcohol use over time. As such, in order to prevent escalation of youth alcohol use, it may be important to identify mothers who have higher levels of risk taking in order to prevent alcohol use escalation in their children. Following this, an inclusion of psychoeducation about the effects of parental modeling in prevention programs might be beneficial. Regarding interventions, results of the present study suggest that in order to treat youth alcohol use, a dual-focused treatment may be beneficial, where youth’s own alcohol use is addressed in addition to maternal risk taking influencing youth use. This fits well with current models of substance use treatment for youth, where the family unit and/or primary parent/guardian are often considered and included in treatment for youth alcohol use (Liddle, Dakof, Turner, Henderson, & Greenbaum, 2008; Smit, Verdurmen, Monshouwer, & Smit, 2008). Thus, a consideration of maternal risk taking across contexts may be important for both intervention and prevention efforts for adolescent alcohol use.

In conclusion, the current study helps to elucidate the complex relationship between maternal riskiness and youth alcohol use escalation from early to middle adolescence. Strengths of the current work include our relatively large sample of mother-child dyads, our diverse sample, our longitudinal design, and our use of a behavioral assessment of maternal risk taking. Our findings suggest the importance of considering maternal riskiness more broadly, rather than solely focusing on maternal alcohol use when attempting to understand youth alcohol use across adolescence. These findings emphasize the relevance of all risky behaviors parents might display in front of youth daily and suggest a general level of riskiness modeled by parents might encourage youth to behave in a riskier manner themselves. Further extensions and replications of this work are necessary in order to confirm causality in additional samples and to explore potential mediators and moderators of this relationship.

Highlights.

Social learning theory implicates parental drinking in offspring consumption

Parental risk taking has not been examined as a predictor of offspring alcohol use

Maternal risk taking predicts youth drinking above and beyond maternal drinking

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

Funding for this study was provided by grants from the National Institute of Drug Abuse Grant 1 F31 DA035033-01 (PI: Banducci), R01DA018647 (PI: Lejuez), 1F31 DA034999 (PI: Dahne), and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship DGE 1322106 (PI: Ninnemann). NIDA and NSF had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Anne N. Banducci took the lead on developing the conceptualization for the paper, writing the first draft of the paper, and editing the final manuscript. Julia W. Felton conducted all of the data analyses for the current paper and contributed to writing sections of the manuscript. Jennifer Dahne and Andrew Ninnemann contributed to writing the manuscript. C.W. Lejuez contributed to the study design, oversaw the study implementation, and was involved with all stages of manuscript preparation. All authors have contributed to and have approved of the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Aklin WM, Lejuez CW, Zvolensky MJ, Kahler CW, Gwadz M. Evaluation of behavioral measures of risk taking propensity with inner city adolescents. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(2):215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JH, Maes HH, Larsson HH, Lichtenstein PP, Kendler KS. Sex differences and developmental stability in genetic and environmental influences on psychoactive substance consumption from early adolescence to young adulthood. Psychological Medicine: A Journal of Research In Psychiatry And The Allied Sciences. 2011;41(9):1907–1916. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000259X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, US: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo Y, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Lynskey M, Bowes G, Patton G. Adverse outcomes of alcohol use in adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96(10):1485–1496. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9610148512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell CC, Allen EE, Strange VV, Oakley AA, Copas AA, Johnson AA, Stephenson JJ. Influence of family type and parenting behaviours on teenage sexual behaviour and conceptions. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(6):502–506. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakefield T, Wilson H, Donenberg G. Maternal models of risk: Links between substance use and risky sexual behavior in African American female caregivers and daughters. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35(4):959–968. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tapert SF. Adolescence and the trajectory of alcohol use: Basic to clinical studies. In: Dahl RE, Spear L, editors. Adolescent brain development: Vulnerabilities and opportunities. New York, NY, US: New York Academy of Sciences; 2004. pp. 234–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cable N, Sacker A. The role of adolescent social disinhibition expectancies in moderating the relationship between psychological distress and alcohol use and misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(2):282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Spitznagel EL, Bucholz KK, Nurnberger JR, Edenberg HJ, Kramer JR, Bierut L. Predictors of sexual debut at age 16 or younger. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(3):664–673. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9397-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champion HL, Foley KL, Durant RH, Hensberry R, Altman D, Wolfson M. Adolescent sexual victimization, use of alcohol and other substances, and other health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35(4):321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Colder CR. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: a longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of abnormal psychology. 1996;105(1):70. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LM, Cater S. Fourteen to 17-year-olds' experience of 'risky' drinking--A cross-sectional survey undertaken in south-east England. Drug And Alcohol Review. 2004;23(3):351–353. doi: 10.1080/09595230412331289509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Reynolds EK, MacPherson L, Kahler CW, Danielson CK, Zvolensky M, Lejuez C. Distress tolerance and early adolescent externalizing and internalizing symptoms: The moderating role of gender and ethnicity. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(3):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton R, Kampfe C. The relationship between family variables and adolescent substance abuse: a literature review. Adolescence. 1994;29:475–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan SC, Duncan TE, Strycker LA. Alcohol use from ages 9 to 16: A cohort-sequential latent growth model. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006;81(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden VB. Trends in initiation of alcohol use in the United States 1975 to 2003. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30(6):1011–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, Clayton R. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and psychopathology. 2004;16(01):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Brown TL, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Leukefeld C, Clayton RR. Developmental patterns of African American and Caucasian adolescents' alcohol use. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12(4):740. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.4.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman AS, Terras A, Zhu W, McCallum J. Depression, negative self-image, and suicidal attempts as effects of substance use and substance dependence. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23(4):55–71. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harburg E, Davis DR, Caplan R. Parent and offspring alcohol use: Imitative and aversive transmission. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1982;43(5):497–516. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins CA, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:280–290. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR. The generality of deviance. In: Hirschi T, Gottfredson MR, editors. The generality of deviance. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Aklin WM, Osborne A, Simmons BL, Strong DR. Construct Validity of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART); Relationship with MDMA Use by Inner-City Drug Users in Residential Treatment. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2006;28(2):95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Huang R, Ho S, Lo W, Lai H, Lam T. Alcohol consumption and sleep problems in Hong Kong adolescents. Sleep Medicine. 2013;14(9):877–882. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MK, Hopko DR, Bare R, Lejuez CW, Robinson EV. Construct Validity of the Balloon Analog Risk Task (BART): Associations With Psychopathy and Impulsivity. Assessment. 2005;12(4):416–428. doi: 10.1177/1073191105278740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong A, Bauer D, Chassin L. Telescoped trajectories from alcohol initiation to disorder in children of alcoholic parents. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2008;117(1):63. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Huang W, Serrano D, Curran PJ, Chassin L. Testing whether and when parent alcoholism uniquely affects various forms of adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40(8):1265–1276. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9662-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson K, Montgomery A. Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29:691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Aklin W, Daughters S, Zvolensky M, Kahler C, Gwadz M. Reliability and Validity of the Youth Version of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART-Y) in the Assessment of Risk-Taking Behavior Among Inner-City Adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36(1):106–111. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Aklin WM, Zvolensky MJ, Pedulla CM. Evaluation of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) as a predictor of adolescent real-world risk-taking behaviours. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(4):475–479. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(03)00036-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, Richards JB, Ramsey SE, Stuart GL, Brown RA. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 2002;8(2):75–84. doi: 10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, Lejuez C. Changes in Sensation Seeking and Risk Taking Propensity Predict Increases in Alcohol Use Among Early Adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(8):1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Molina MM, Jennings WG, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol on trajectories of physical aggression among urban youth: An application of latent trajectory modeling. Journal of Youth And Adolescence. 2010;39(9):1012–1026. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9484-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W, Hitch JE, Kosterman R, McCarty CA, Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins J. Growth in adolescent delinquency and alcohol use in relation to young adult crime, alcohol use disorders, and risky sex: A comparison of youth from low-versus middle-income backgrounds. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51(12):1377–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Faden VB, Zucker RA, Spear LP. Underage drinking: A developmental framework. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supplement 4):S235–S251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, lacono WG, Legrand LN, Elkins I. Origins and consequences of age at first drink: II. Familial risk and heritability. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(8):1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Lalumière ML. Is the crime drop of the 1990s in Canada and the USA associated with a general decline in risky and health-related behaviors? Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Lalumière ML, Williams RJ. Gambling as a form of risk taking: Individual differences in personality, behavioral preferences for risk, and risk-accepting attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;49:616–621. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rende R, Slomkowski C. Incorporating the family as a critical context in genetic studies of children: Implications for understanding pathways to risky behavior and substance use. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(6):606–616. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter L, Richter DM. Exposure to parental tobacco and alcohol use: Effects on children’s health and development. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71:182–203. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer K. Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2010;26(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Smit E, Verdurmen J, Monshouwer K, Smit F. Family interventions and their effect on adolescent alcohol use in general populations; a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97(3):195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L, Katz B, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Golembeske C, Lebeau-Craven R, Monti P. Validity and reliability of the alcohol expectancy questionnaire-adolescent, brief. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2007;16(2):115–127. doi: 10.1300/J029v16n02_06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- White H, Johnson V, Buyske S. Parental modeling and parenting behavior effects on offspring alcohol and cigarette use: A growth curve analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;12(3):287–310. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder EI, Watt T. Risky parental behavior and adolescent sexual activity at first coitus. Milbank Quarterly. 2002;80(3):481–524. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Ham LS, Hernandez Jarvis L, Olthuis JV. Do alcohol expectancy outcomes and valuations mediate peer influences and lifetime alcohol use among early adolescents? The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research And Theory on Human Development. 2009;170(4):359–376. doi: 10.1080/00221320903218380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking and risky behavior. Washington, DC US: American Psychological Association; 2007. Sensation Seeking and Risk; pp. 51–72. 51–72. [Google Scholar]