Summary

A Children’s Oncology Group clinical trial aimed to determine if bortezomib (B) increased the efficacy of ifosfamide and vinorelbine (IV) in paediatric Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). This study enrolled 26 relapsed HL patients (< 30 years) treated with 2–4 cycles of IVB. The primary endpoint was anatomic complete response (CR) after 2 cycles. Secondary endpoints included overall response (OR: CR + partial response) at study completion compared to historical controls (72%; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 59–83%). Although few patients achieved the primary objective, OR with IVB improved to 83% (95% CI 61–95%. p=0.32). Although not statistically different, results suggest IVB may be a promising combination.

Keywords: clinical trials, paediatric oncology, childhood haematological malignancies, NF-κB

Introduction

Despite high initial success rates in the treatment of paediatric Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL), approximately 10–20% of patients develop resistant/relapsed disease (Kelly et al, 2012; Schwartz et al, 2009). While high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation has improved outcomes, the best of these regimens still have limited success rates (Schellong et al, 2005) and novel therapeutic approaches are required for these patients. Bortezomib is a small molecule that inhibits the 26S proteasome, stabilizing proteins degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system including the nuclear factor (NF)-κB inhibitor, IκB (Cvek & Dvorak, 2011). This pilot phase 2 clinical trial investigated the tolerability and efficacy of bortezomib in combination with ifosfamide and vinorelbine (IV), a previously tested regimen in relapsed paediatric HL (Trippett et al, 2015). The primary objective was to determine if IV plus bortezomib (IVB) improved the complete response (CR) rate in HL patients when compared to historical controls. Secondary objectives included overall response rate (CR + partial response [PR]) after 2 and 4 cycles of therapy. The relationship between pretreatment NF-κB pathway proteins in Hodgkin and Reed/Sternberg cells and response to IVB treatment were also examined.

Methods

The study (AHOD0521) was conducted by the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) between January 2007 and April 2008. Eligible patients were less than 30 years of age with a diagnosis of either primary refractory HL or HL in first relapse. Written informed consent was obtained according to institutional guidelines and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all institutional, Food and Drug Administration and National Cancer Institute requirements for human studies were met. Inclusion criteria included biopsy-confirmed HL at time of first relapse or progression with measurable disease (nodal diameter >2 cm), adequate performance status (Karnovsky scale ≥60 if > 16 years of age, Lansky scale ≥60 if ≤16 years), life expectancy of ≥2 months, recovery from the toxic effects of prior therapy and adequate bone marrow, pulmonary, renal, liver, central nervous system (CNS) and cardiac function. Key exclusion criteria included serious intercurrent illness or known hypersensitivity to mannitol, boron, E.coli-derived proteins or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF); CNS toxicity or peripheral neuropathy > Grade 2; other investigational drug within 14 days prior to enrollment; pregnancy, breastfeeding or concomitant use of an anticonvulsant or other known activators of the cytochrome P450 system.

The clinical trial was a multi-centre, open-label, non-randomized phase 2 study with up to four 21-day cycles. During each cycle, patients were treated with ifosfamide (3000 mg/m2/day on days 1–4) with MESNA (3 g/m2/day, days 1–5) by continuous infusion; vinorelbine (25 mg/m2/dose, days 1 and 5) and bortezomib 1.2 mg/m2/dose on days 1, 4 and 8 for each cycle. After 2 cycles of IVB, response was evaluated by computerized tomography (CT) and [18F]-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). The primary response objective was defined by anatomic tumour shrinkage after 2 cycles based on CT with negative PET assessment (see Supporting Information). Patients who achieved a CR after two cycles either proceeded to stem cell transplantation (SCT) or received additional cycles of therapy while awaiting SCT. Response was re-evaluated at the end of cycles 3 to 4 of IVB. Patients with progressive disease at any time during treatment were removed from protocol therapy.

The study was designed to compare 2-cycle CR rate in patients treated with IVB on this study to that of a historical control cohort treated with IV (COG study AHOD00P1), which had a 26% CR rate (16/61 patients) (Trippett et al, 2015). Interim monitoring for lack of efficacy was built in after 24 evaluable patients and required 5 or more CR for continued accrual. Follow-up data on AHOD0521 and AHOD00P1 are as of 31 March 2014 and 31 March 2012 respectively. Log rank test was used to compare event-free survival/overall survival (EFS/OS) between IVB and historical controls treated with IV (Peto & Peto, 1972). Statistical differences between CR rates were determined using the χ2 test. Adverse events were evaluated by Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0 (http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf). Pretreatment NF-kB pathway proteins expression was determined by immunohistochemistry (see Supporting Information, Methods for details).

Results

Of the 26 patients enrolled on study, 25 were deemed eligible and their characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Table I. Study accrual was suspended after 26 enrollments due to lack of efficacy in the interim monitoring, i.e. fewer than 5 patients with anatomic CR after 2 cycles of therapy in 24 evaluable patients. Two patients were considered un-evaluable for response; one received 1/3 dose of bortezomib due to pharmacy error (cycles 1 and 2), the other was removed after 1 dose of bortezomib at the physician’s discretion and parental preference. Supplemental Table II summarizes all Grade 3 and 4 adverse events reported among the 23 response-evaluable patients on the clinical trialm regardless of attribution. Haematological toxicities were the most common, including neutropenia (12/23, 52%), leucopenia (11/23, 48%), lymphopenia (8/23, 35%) and anaemia (6/23, 26%). The incidence of thrombocytopenia was modest (5/23, 22%). Infectious adverse events included 6 cases of bacteriaemia and 4 cases of varicella-zoster. There were two cases of Grade 3 neuralgias; the first case of neuralgia was associated with varicella-zoster and the second case resolved after the omission of G-CSF from further therapy courses. Other Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in more than one patient included Grade 3–4 hypokalemia (n=7), Grade 3 pain (n=5), alanine transaminase (n=4), emesis (n=2) and hyperglycaemia (n=2). No significant hepatic, cardiac or renal toxicities were seen.

Response assessment was based on central review of anatomic regression as measured by CT scan. Responses for all evaluable patients are summarized in Table I. Overall response (CR+PR) was 83% after 2 cycles (95% confidence interval [CI]: 61–95%). For the best response achieved during the study, 12 of the 23 evaluable patients (52%) achieved an anatomic CR. Two patients first attained a CR after 2 cycles, 3 patients after 3 cycles and 7 patients after 4 cycles. Nine patients (39%) achieved a PR (all after 2 cycles). Overall response was 91% after 2 to 4 cycles of IVB.

Table I.

Response to IVB therapy in 23 evaluable patients

| 2 cycle response | Best 2–4 cycle response |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT response | n | % | n | % |

| CR | 2 | 9 | 12 | 52 |

| PR | 17 | 74 | 9a | 39 |

| SD | 4 | 17 | 2b | 8 |

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ORR | 19 | 83 | 21 | 91 |

| FDG-PET response | n | % | n | % |

| Positive | 12 | 52 | 8c | 35 |

| Negative | 11 | 48 | 15 | 65 |

Three patients had a PR after 2 cycles of therapy without further response evaluations; 1 of these patients had a 3rd cycle of therapy and proceeded to stem cell transplantation.

One scan was read as SD by the Quality Assurance Response Centre, Boston but PD by institution. The patient was removed from therapy at physician's discretion.

One FDG-PET positive result was equivocal

IVB, ifosfamide, vinorelbine and bortezomib; CT, computerized tomography; FDG-PET, [18F]-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission tomography; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, overall response rate.

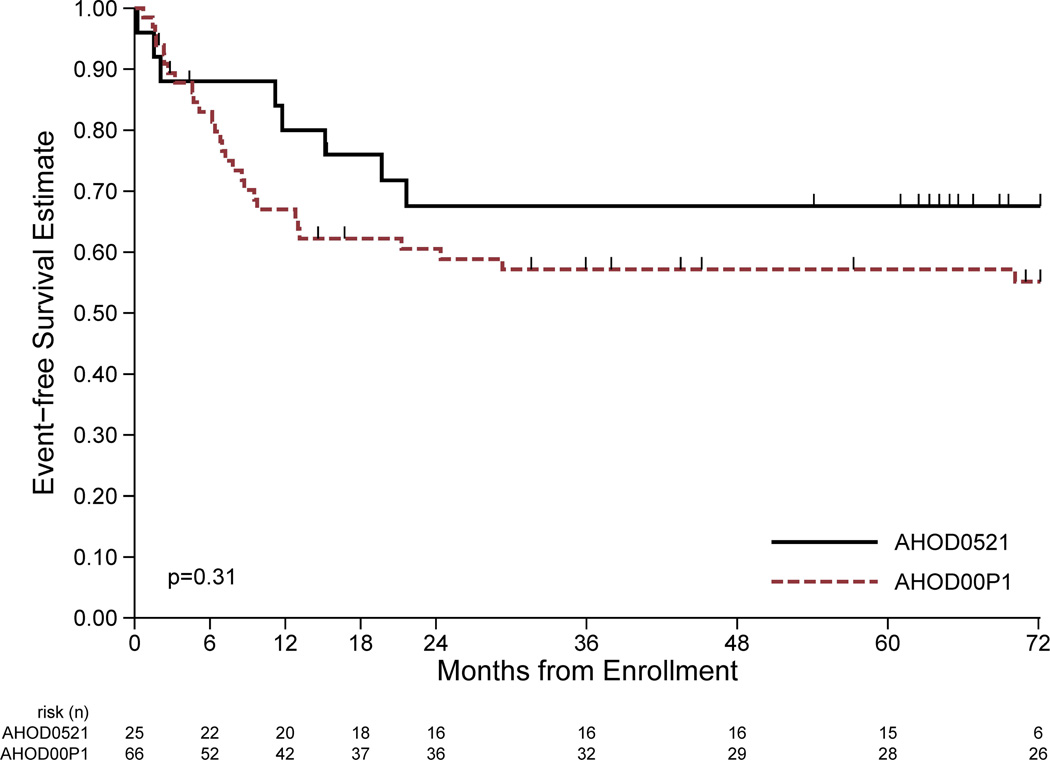

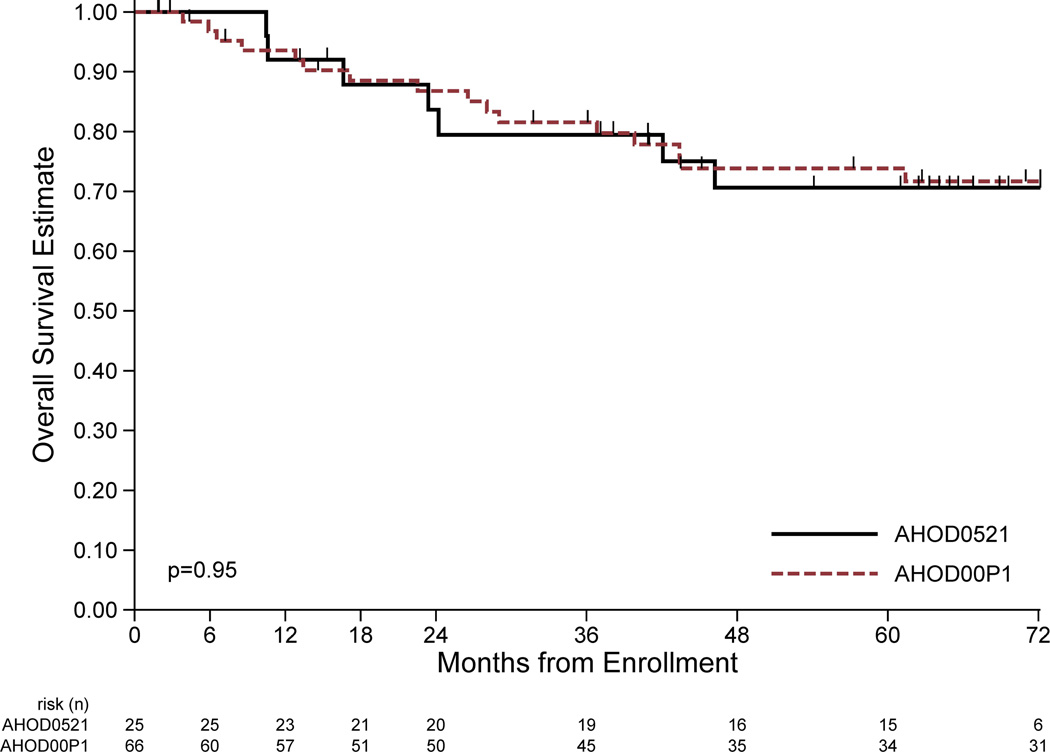

The EFS and OS estimates for patients treated on this study and the historical controls treated with IV are shown in Fig 1. Eight EFS events (first events all relapse/progression) and seven deaths have been reported among the 25 eligible patients on this study at a median follow-up of 67 (range 15–81) months. Four-year EFS and OS estimate for eligible patients was 68% (95% CI: 45–82%) and 79% (95% CI: 57–91%), respectively. Excluding the 2 un-evaluable patients (1 with relapse and subsequent death), the 4-year EFS and OS was 69% (95% CI 46–84%) and 72% (95% CI: 48–87%), respectively, for the 23 evaluable patients, which was not statistically different than the 72% EFS seen in historical controls (95% CI: 59–83%).

Figure 1.

Comparison of event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) between ifosfamide/vinorelbine (IV) with bortezomib (IVB; AHOD0521) to the historical control study using IV alone (AHOD00P1). A: EFS of patients in the current study (solid line) treated with IVB vs. patients treated with IV alone (dashed line). B: OS of current study using IVB (solid line) and historical control trial using IV(dashed line). Significance (p values) determined by log rank test.

Pre-treatment biopsies were assessed for NF-κB subunits, including RelA (p65), RelB, and Rel (Supplemental Fig 1A), along with CD30, CD40 and LMP1 to assess Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivity. Nuclear phospho-RelA and RelB NF-κB subunits, as well as cytoplasmic RelB, were overexpressed in all relapsed HL patients when compared to either non-malignant tissue, or to HL patients at original diagnosis (Supplemental Fig 1B). No significant associations were noted between NF-κB protein expression and prognostic HL risk factors, including prior radiation, number of involved sites at relapse, EBV status, treatment FDG-PET response, induction success or treatment response (data not shown).

Discussion

Although bortezomib did not increase anatomic CR after 2 cycles, it suggests an improvement in overall response (91%) at the completion of therapy. The primary endpoint of this study assumed that it would be feasible to detect an increase in early anatomic response rate, as determined by CT, from 26% (seen in historical control trial AHOD00P1) to 46%. Based on the modest early anatomic response, the study was closed by the data monitoring safety board. However, an additional 9 patients had a negative FDG-PET by the end of cycle 2, resulting in an overall early response rate by FDG-PET of 48%. Twenty-one of 23 patients (91%; 95% CI 72–99%) achieved an overall response (CR + PR) over 2–4 cycles by CT assessment vs. 72% (95% CI 59–83%) in the historical control trial. A larger study would be needed to determine whether adding bortezomib to standard HL retrieval therapy improved efficacy. In retrospect, a study design that included either a longer treatment prior to primary response assessment and/or a functional assessment of response may have allowed the trial to run to completion.

Although contemporary response criteria utilize FDG-PET imaging to define CR, anatomic (CT-based) response was used for this study to allow comparison with the historical control trial, which took place before the widespread availability of FDG-PET scanning. Nevertheless, it is notable that 5 of 8 patients had positive or equivocal FDG-PET scans at last assessment, versus only 2 of 15 with negative FDG-PET scans at last assessment (p=0.026 Fisher’s exact test). These results support the current literature that both FDG-PET and CT are useful response predictors in paediatric HL (Cheson, 2008) and suggests the possibility that the primary response assessment may have underestimated the efficacy of this regimen by relying solely on early anatomic response. Further exploration of proteasome inhibition for paediatric patients with relapsed/ refractory HL is worth consideration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Gaye Jenkins for technical assistance and to Lanie Lindenfeld for protocol assistance. This COG clinical trial was funded by U10CA098543 (Chairs Grant) and U10CA098413 (Statistics and Data Management) to the COG, a NIH-NCI-K23 (NIH-NCI-CA113775) (TMH), a Lymphoma SPORE Developmental Research Project (P50CA126752) and a grant to the DLDCC (NIH-CA125123) for statistical support of the biology studies.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

TMH, RD, SV, RPG, AS, DLP and KM performed the research. TMH, LC, PDA, TT, SH and CS designed the research study. LC, MM, NA, MFW and HL analysed the data. TMH wrote the paper. All authors assisted with critical paper revisions and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Clinical trial registration: This trial is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00381940)

Previous presentations, reports or publications containing material appearing in the manuscript

This work was presented in part at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), June, 2010: Horton, T.M., Drachtman, R.A., Chen, L., Trippet, T., De Alarcon, P., Chen, A.R., Guillerman, R.P., McCarten, K., Hogan, S.M., & Schwartz, C. (2010) A phase II study of bortezomib with ifosfamide and vinorelbine in paediatric patients with refractory/recurrent Hodgkin disease (HD): A Children's Oncology Group (COG) study. Proc ASCO, 28, Abstract 9537.

Competing interests: the authors have no competing interests.

Author statement of originality of work

The authors confirm that this manuscript contains original material.

References

- Cheson BD. New staging and response criteria for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. Radiol.Clin.North Am. 2008;46:213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2008.03.003. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvek B, Dvorak Z. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and the mechanism of action of bortezomib. Curr.Pharm.Des. 2011;17:1483–1499. doi: 10.2174/138161211796197124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KM, Hodgson D, Appel B, Chen L, Colev PD, Horton T, Keller FG. Children's Oncology Group's 2013 blueprint for research: Hodgkin lymphoma. Pediatr.Blood Cancer. 2012;60:972–978. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant test procedures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. 1972;135:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Schellong G, Dorffel W, Claviez A, Korholz D, Mann G, Scheel-Walter HG, Bokkerink JP, Riepenhausen M, Luders H, Potter R, Ruhl U. Salvage therapy of progressive and recurrent Hodgkin's disease: results from a multicenter study of the pediatric DAL/GPOH-HD study group. J.Clin.Oncol. 2005;23:6181–6189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CL, Constine LS, Villaluna D, London WB, Hutchison RE, Sposto R, Lipshultz SE, Turner CS, deAlarcon PA, Chauvenet A. A risk-adapted, response-based approach using ABVE-PC for children and adolescents with intermediate- and high-risk Hodgkin lymphoma: the results of P9425. Blood. 2009;114:2051–2059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippett TM, Schwartz CL, Guillerman RP, Gamis AS, Gardner S, Hogan S, London WB, Chen L, de Alarcon P. Ifosfamide and vinorelbine is an effective reinduction regimen in children with refractory/relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma, AHOD00P1: a children's oncology group report. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2015;62:60–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.