In the United States, approximately 1.2 million individuals are infected with HIV, 168,000 remain without a diagnosis, and 50,000 new infections occur annually.1,2 Estimates of new infections have not changed significantly during the last 15 years, and the number of new diagnoses appears to be increasing in certain populations.1 Although the largest group of individuals with newly diagnosed HIV remains men who have sex with men, new cases disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities, adolescents and young adults, and the economically disadvantaged. Blacks represent 14% of the total population but account for 44% of all new infections, whereas Hispanics represent 16% of the total population but account for 20% of all new infections. Individuals aged 13 to 29 years account for the highest rate of new HIV infections among all ages, and black men who have sex with men in this age range represent the group with the largest increase in new infections since 2006.1–3 Also, approximately half of all individuals with newly diagnosed HIV in the United States live in the poorest census tracts,3 and of the 1.2 million individuals living with HIV infection, only 40% are actively engaged in HIV care and only 30% are virally suppressed.4

The HIV care continuum was developed in 2011 to improve our understanding of the HIV epidemic as a whole and to describe the spectrum of care from initial infection to achievement of viral suppression.5 Inherent in the continuum is the concept that the early components, the “diagnosis” end of the continuum, are sequential and contingent; ie, a patient cannot be linked to care without first receiving a diagnosis of HIV or cannot be retained in care without first being linked. This contingency is not sustained at the “care” end of the continuum; here, individuals with viral suppression may stop therapy for a variety of reasons and cease receiving care, effectively moving backwards along the continuum. From a societal perspective, optimal care for individuals with HIV infection must include a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach to all phases of care, including identification, linkage to and retention in care, and adherence to treatment.6

In the United States, more than 135 million emergency department (ED) visits occur annually and EDs are considered the most common site of missed opportunities for diagnosing HIV infection.7–9 During the last decade, emergency physicians have increasingly recognized the importance of EDs in HIV diagnosis and prevention while serving the same populations that are disproportionately affected by HIV infection.10–13 Moreover, EDs provide care to a large number of individuals with known HIV infection, many of whom have ceased receiving care. In a sense, EDs operate at a crossroads of the HIV care continuum, with individuals filtering in from both the “diagnosis” and “care” ends. Individuals who are disengaged from or are cyclically engaged in care commonly present to EDs with non-HIV-related illnesses or progression of HIV disease. Such patients also often present with psychiatric illnesses or substance abuse—related issues, both of which are associated with poor engagement in care.14 Given these features, EDs are outstanding settings to identify patients with undiagnosed HIV infection while facilitating linkage to care for those receiving a new diagnosis and who previously had not received one.

In this volume of Annals, Hsieh et al15 advance our understanding of the HIV epidemic by providing insight for how emergency physicians and emergency care processes may more broadly affect patients with HIV infection. This study reports, for the first time in an ED setting, estimates of all components of the HIV care continuum among a cohort of ED patients with HIV infection. Furthermore, their study includes suggested additional components tied to both physician and patient awareness of diagnosis, treatment, and disease stage, recognizing that awareness is a requisite to action. Using multiple data sources, including an identity-unlinked seroprevalence evaluation, nontargeted rapid HIV screening, and structured patient surveys, the authors were able to estimate all facets of the HIV care continuum.

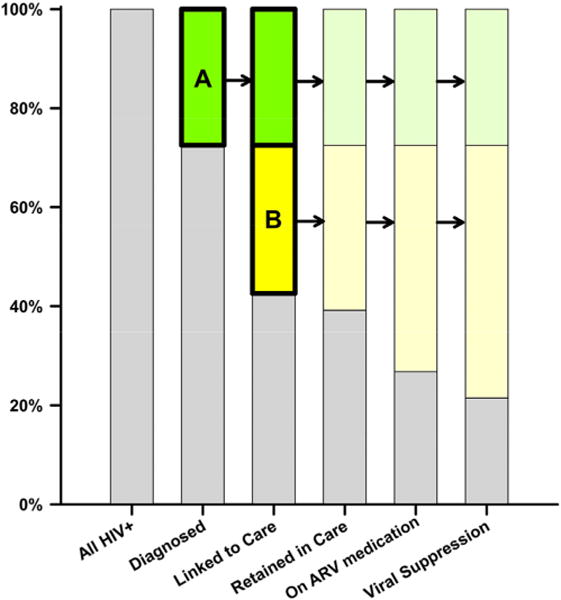

Several important considerations should be inferred from this study, some of which are highlighted in the Figure. First, approximately 8% of the Johns Hopkins ED cohort was infected with HIV. The population served by their hospital has a high prevalence of HIV infection, and although the infection rate in other settings may not compare to this estimate, essentially all urban settings serve populations with higher HIV prevalence than that of the general population in the United States.16 Of the patients infected with HIV, approximately 27% had not received a diagnosis (Figure) compared with 14% nationally,4 confirming the importance of ongoing HIV screening in EDs. Although different approaches of identifying patients for ED-based testing continue to be evaluated and the optimal screening approach remains uncertain,17–20 testing for HIV infection, irrespective of the screening approach, remains the critical first step in a series of important interventions aimed at reducing the burden of HIV disease. Identifying such individuals with HIV infection provides a critical opportunity to link them to care in which treatment slows disease progression and reduces infectivity. In fact, HIV-infected individuals receiving treatment have near-normal life expectancies,21,22 and those with undetectable viral loads have a 96% reduction in forward transmission.23 Also, knowing one’s serostatus attenuates behaviors that contribute to transmission of the virus.24,25

Figure.

The HIV care continuum using estimates from Hsieh et al15 (gray shaded), with particular emphasis on identifying and linking patients with undiagnosed HIV infection (A, green), relinkage of patients with known HIV infection but who have ceased care (B, yellow), and the potential downstream effects of these actions (color shaded). ARV, Antiretroviral.

Second, although emergency physicians should continue to identify patients with undiagnosed HIV infection, those having previously received a diagnosis but who are not actively engaged in HIV care benefit substantially from linkage or relinkage to care. Patients in the act of transitioning their care because of serious life events (eg, loss of insurance or moving to a new city) may need particular help accessing HIV care. These same patients are more likely to be treated in EDs because of challenges that exist in navigating the US health care system. In the Johns Hopkins ED cohort, approximately 30% of patients who previously received a diagnosis were not in care (Figure), which is similar to or slightly larger than the proportion who had not received a diagnosis. As such, emergency physicians have a substantial opportunity to improve downstream aspects of HIV care by identifying and consistently relinking patients who previously received a diagnosis of HIV infection but who have ceased care. Routine linkage to specialized HIV care should be consistently and actively adopted in EDs.

Third, the estimates provided by Hsieh et al15 systematically differ from statistics of the broader non-ED HIV-infected population,4 suggesting that patients who present to EDs are more likely not to have received a diagnosis and less likely to be in care, to be receiving antiretroviral therapy, or to have suppressed viral loads. This supports the discussion above that the populations most affected by HIV are the same ones most likely to present for care in EDs. In addition, these are the same populations who transition through the HIV continuum poorly.26 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has presented data supporting that younger individuals, blacks and Hispanics, and male injection drug users are less likely to have viral suppression than their counterparts.26,27 These same groups are also less likely to have health insurance coverage and access to regular medical care.28

EDs are a critical access point to the US health care system for many individuals, including those most affected by HIV infection. The article by Hsieh et al15 provides important insight into one of many ways EDs support public health and the health of their communities. The ED HIV care continuum represents a snapshot of the spectrum of HIV prevention, diagnosis, and care activities in that community. By working at the crossroads of the HIV continuum—diagnosis, linkage, and relinkage to care—EDs interface with individuals at the most vulnerable points in the health care system for populations that are commonly disenfranchised and marginalized. By shoring up these points, EDs help to support the patient, the community, and the health care system as a whole.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Emily Hopkins, MSPH (Denver Health, Denver, CO), and Meggan Bucossi, BA (Denver Health, Denver, CO), for their contributions to conceptual ideas included in this editorial.

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist. Supported in part by R34MH090870 from the National Institute of Mental Health (Dr. Gardner) and R01AI106057 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Dr. Haukoos).

Footnotes

Supervising editor: Kathy J. Rinnert, MD, MPH

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States. 2011:201. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/PDF/us.pdf. Accessed April 20.

- 2.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection in 18 areas, 2005–2009. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2015 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/#supplemental. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV care continuum for the United States and Puerto Rico. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/Continuum_Surveillance.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- 5.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall HI, Tang T, Westfall AO, et al. HIV care visits and time to viral suppression, 19 US jurisdictions, and implications for treatment, prevention and the national HIV/AIDS strategy. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 emergency department summary tables. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2011_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- 8.Jenkins TC, Gardner EM, Thrun MW, et al. Risk-based human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing fails to detect the majority of HIV-infected persons in medical care Settings. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:329–333. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194617.91454.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Wayne DB, et al. Comparison of missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in 3 geographically proximate emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(suppl 1):S17–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.018. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman RE, Lyons MS, Haukoos JS. Uncovering HIV infection in the emergency department: a broader perspective. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:653–657. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J, et al. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2006 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2008:1–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothman RE. Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for HIV counseling, testing, and referral: critical role of and a call to action for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ledyard HK, et al. Health department collaboration with emergency departments as a model for public health programs among at-risk populations. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:259–265. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wawrzyniak AJ, Rodriguez AE, Falcon AE, et al. Association of individual and systemic barriers to optimal medical care in people living with HIV/AIDS in Miami-Dade County. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(suppl 1):S63–S72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh YH, Kelen GD, Laeyendecker O, et al. HIV care continuum for HIV-infected emergency department patients in an inner-city academic emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.01.001. Available at: http://dx/doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and AIDS in the United States by geographic distribution. 2012 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_geographic_distribution.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- 17.Haukoos JS. The impact of nontargeted HIV screening in emergency departments and the ongoing need for targeted strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:20–22. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haukoos JS, Hopkins E, Bender B, et al. Comparison of enhanced targeted rapid HIV screening using the Denver HIV risk score to nontargeted rapid HIV screening in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ruffner AH, et al. Randomized comparison of universal and targeted HIV screening in the emergency department. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:315–323. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a21611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman RE, Gauvey-Kern M, Woodfield A, et al. Streamlining HIV testing in the emergency department—leveraging kiosks to provide true universal screening: a usability study. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:122–127. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wada N, Jacobson LP, Cohen M, et al. Cause-specific mortality among HIV-infected individuals, by CD4(+) cell count at HAART initiation, compared with HIV-uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2014;28:257–265. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292:224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, et al. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: implications for HIV prevention programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley H, Hall HI, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:1113–1117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare disparities report. 20122012 Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr12/. Accessed April 20, 2015.