Abstract

Research has indicated that Hispanics have high rates of heavy drinking and depressive symptoms during late adolescence. The purpose of this study was to test a bicultural transaction model composed of two enthnocultural orientations (acculturation and enculturation); and stressful cultural transactions with both the U.S. culture (perceived ethnic discrimination) and Hispanic culture (perceived intragroup marginalization) to predict alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms among a sample of 129 (men = 39, women = 90) late adolescent Hispanics (ages 18 to 21) enrolled in college. Results from a path analysis indicated that the model accounted for 18.2% of the variance in alcohol use severity and 24.3% of the variance in depressive symptoms. None of the acculturation or enculturation domains had statistically significant direct effects with alcohol use severity or depressive symptoms. However, higher reports of ethnic discrimination were associated with higher reports of alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms. Similarly, higher reports of intragroup marginalization were associated with higher depressive symptoms. Further, both ethnic discrimination and intragroup marginalization functioned as mediators of multiple domains of acculturation and enculturation. These findings highlight the need to consider the indirect effects of enthnocultural orientations in relation to health-related outcomes.

Keywords: Hispanics, late adolescence, alcohol, depressive symptoms, cultural stress, acculturation

Late adolescence spans ages 18 to 21, corresponds with the college years for many (Steinberg, 2008), and is a time of transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. This period is also marked by heavy drinking (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2006) and elevated depressive symptoms (Rudolph, 2009). Further, heavy drinking and elevated depressive symptoms are notably prevalent among late adolescent Hispanics (Cheref, Lane, Polanco-Roman, Gadol, & Miranda, 2014; Venegas, Cooper, Naylor, Hanson, & Blow, 2012), due in part to ethnocultural orientation (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006).

Ethnocultural Orientation

Ethnocultural orientation consists of two cultural dimensions: (1) acculturation, the degree to which an individual from one culture (e.g., Hispanic) acquires cultural behaviors, beliefs, and values from a new receiving culture (e.g., U.S.; Williams & Berry 1991); and (2) enculturation, a process of (re)-socialization heritage culture norms (Kim & Abreu, 2001). These dimensions can unfold independently over time and can be measured separately (Kim & Ominzo, 2006; Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010).

Further, each ethnocultural dimension consists of multiple domains (Schwartz et al., 2010). For instance, the behavioral domain encompasses cultural practices such as preferences in language use and food choice, whereas the affective domain is comprised of attitudes toward the heritage and receiving culture (Kim & Abreu, 2001).

Enthnocultural Orientation and Health

Among Hispanics, higher acculturation is associated with greater alcohol consumption (Zemore, 2007) and fewer depressive symptoms (Torres, 2010). Conversely, higher enculturation is associated with less alcohol consumption (Des Rosiers, Schwartz, Zamboanga, Ham, & Huang, 2013) and fewer depressive symptoms (Cano & Castillo, 2010). However, the extant research on enculturation is limited (Castillo & Caver, 2009) and is heavily focused on the behavioral domain of ethnocultural orientation (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2006). Further, research lacks theoretical explanatory frameworks for relations between ethnocultural orientation and health (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2006). Consequently, little is known about the mechanisms through which ethnocultural orientation affects health outcomes. To address this gap, we examined associations of acculturation and enculturation domains with alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms, as well as potential mediators of those associations.

Cultural Transactions

Cultural transactions, or perceptions of one's interactions with the receiving and heritage cultures, may help explain the link between ethnocultural orientation and health outcomes. Although cultural transactions can be positive (Cano, Vaughan, de Dios, Castro, Roncancio, & Ojeda, in press) or negative (Cano et al., 2015), we focused on negative cultural transactions. This follows from Acculturation Strain Theory, which proposes that enthnocultural orientation, operationalized as a unidimensional continuum of acculturation, is associated with increased experience of cultural stressors that in turn contribute to substance use and poor mental health outcomes (Vega, Zimmerman, Gil, Warheit, & Apospori, 1997). Although this model does not explicitly discuss the role of enculturation on cultural transactions, it argues that negative cultural transactions mediate the effect of ethnocultural orientation on health outcomes.

Among Hispanics, ethnic discrimination (i.e., being treated unfairly or negatively based on one's ethnic background; Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998) may serve as an indicator of an intercultural transaction (perceptions of encounters with the receiving [U.S.] culture) that links ethnocultural orientation with substance use and mental health. Higher acculturation is associated with greater perceived discrimination, whereas higher enculturation is associated with less perceived discrimination (Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013). In turn, perceived discrimination is associated with increased substance use (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2013) and depressive symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011).

Intragroup marginalization, the perceived distancing from one's ethnic group members when one displays characteristics of the dominant group (Castillo, Conoley, Brossart, & Quiros, 2007), may serve as an indicator of an intracultural transaction (perceptions of encounters with the heritage [Hispanic] culture) that link ethnocultural orientation with substance use and mental health. Higher acculturation is associated with greater intragroup marginalization (Castillo et al., 2007). In turn, greater intragroup marginalization is associated with greater depressive symptomatology (Cano, Castillo, Castro, de Dios, & Roncancio, 2014). No published study has examined relations between intragroup marginalization and enculturation or alcohol use.

Present Study

Therefore, we tested a bicultural transaction model that integrates a bidimensional operationalization of ethnocultural orientation and two cultural transactions: intragroup marginalization and ethnic discrimination. The purpose of this model was to develop a framework that was both culturally and clinically relevant to understand substance use and mental health among Hispanics. We hypothesized that behavioral and affective acculturation and enculturation, as well as intragroup marginalization and perceived discrimination, would be directly associated with alcohol use and depressive symptomatology. In addition, we hypothesized that behavioral and affective acculturation and enculturation would be indirectly associated with alcohol use and depressive symptomatology by way of their associations with intragroup marginalization and perceived discrimination.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 129 late adolescents. Participants were recruited via an email that described study aims and procedure, contained an internet link to the anonymous survey, and voluntary consent information. Eligible participants had to self-identify as Hispanic or Latina/o and be enrolled in a two or four-year institution of higher education. No compensation was provided.

Measures

Alcohol use severity was measured with the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 1993). Higher scores indicated greater alcohol use severity.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Higher scores indicated higher depressive symptoms.

Perceived ethnic discrimination was measured with the Environmental Scale from the Social, Attitudinal, Familial, and Environmental Acculturation Stress Scale (S.A.F.E.; Fuentes & Westbrook, 1996). Higher mean scores indicated a higher perception of ethnic discrimination.

Intragroup marginalization was measured using the Intragroup Marginalization Inventory-Family Scale (IMI-F; Castillo et al., 2007). Higher summed scores indicated greater perceptions of intragroup marginalization.

Behavioral acculturation and enculturation were measured with the Anglo Orientation Subscale (AOS) and the Mexican Orientation Subscale (MOS), respectively of the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II; Cuéllar et al., 1995). Higher mean subscale scores indicate higher behavioral acculturation and enculturation. Affective acculturation and enculturation were evaluated with the Anglo Marginalization Subscale (ANGMAR) and the Mexican Marginalization Subscale (MEXMAR) of the ARSMA-II. Higher mean subscale scores indicate lower affective acculturation and enculturation. Items in the ARSMA-II with the term “Mexican” were modified to “Hispanic/Latino” to make them applicable to Hispanic respondents of various national origins.

Analytic Plan

The current study utilized a path analysis with Full Information Maximum Likelihood to estimate all direct and indirect paths. The model was evaluated using four model fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1995; Kline, 2005): (a) chi-square test of model fit (χ2) > .05, (b) comparative fit index (CFI) > .90, (c) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .08, and (d) standardized root means square residual (SRMR) < .08. Estimated paths were controlled for self-reported age and gender (female=1).

Results

Descriptive Analysis

The sample included undergraduate men (30.2%) and women (69.8%) of predominately Mexican heritage (76.0%), with a mean age of 19.41 (SD = 1.11). A majority of the participants (95.3%) were enrolled in four-year institutions. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations, and internal consistency for the variables used in path analysis.

Table 1. Bivariate Correlations, Means, Standard Deviations, and Internal Consistency for Variables Used in Path Analysis (n = 129).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | M | SD | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Alcohol Use Severity | - | 4.28 | 5.45 | .88 | |||||||||

| 2. | Depressive Symptoms | .18* | - | 17.82 | 12.10 | .91 | ||||||||

| 3. | Age | -.01 | -.02 | - | 19.41 | 1.11 | - | |||||||

| 4. | Gender | -.30** | .11 | -.11 | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| 5. | Ethnic Discrimination | .23* | .45** | .02 | .15 | - | 22.93 | 8.30 | .84 | |||||

| 6. | Intragroup Marginalization | .12 | .30** | -.08 | .05 | .17 | - | 28.87 | 12.87 | .83 | ||||

| 7. | Behavioral Acculturation | -.06 | .02 | -.15 | .14 | -.20* | .22* | - | 3.38 | .54 | .78 | |||

| 8. | Behavioral Enculturation | .01 | .01 | .02 | .08 | .08 | -.38** | -.29** | - | 3.45 | .77 | .89 | ||

| 9. | Affective Acculturation | .20* | .13 | .02 | .01 | .31** | .10 | -.07 | .25** | - | 2.41 | .98 | .94 | |

| 10. | Affective Enculturation | .09 | .15* | .02 | .18* | .21* | .30** | .12 | -.06 | .49** | - | 2.05 | .73 | .88 |

p < .05,

p < .01, α = Cronbach's alpha internal consistency.

Path Analysis

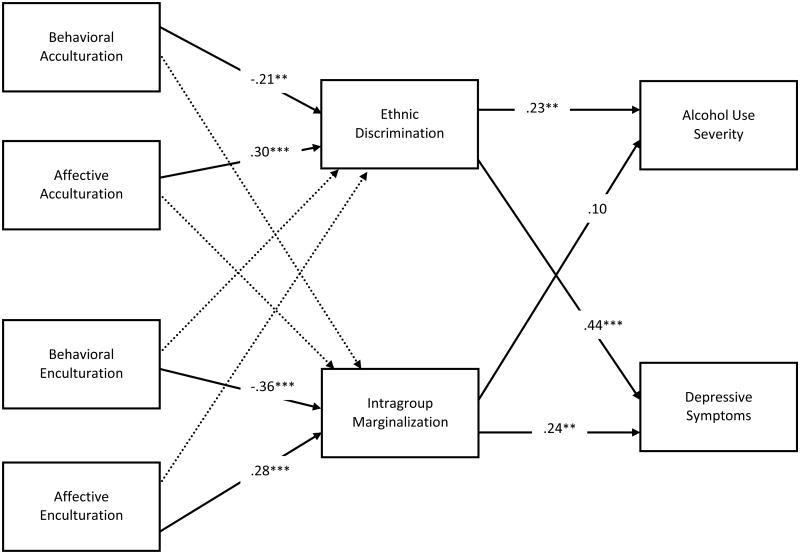

Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized model with statistically significant standardized coefficients from the final model. Most fit indices for the hypothesized model indicted adequate model fit; however, the RMSEA was greater than .08. Therefore, we omitted four paths specified by the modification indices that were not statistically significant. All omitted paths were from enthnocultural orientation predicting cultural transactions. Results from the modified path analysis indicated adequate model fit: χ2 (n = 129, df = 5) = 6.87, p > .05, CFI = 0.981, RMSEA = 0.054, SRMR, = 0.030. The final model accounted for following proportions of variance: alcohol use severity (18.2%), depressive symptoms (24.3%), perceived discrimination (16.0%), and intragroup marginalization (22.7%).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model with Standardized Coefficients from Final Path Analysis.

* p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; Dotted line = omitted path from final model; Estimated paths controlled for age and gender

Direct Effects

Perceived discrimination was directly associated with alcohol use severity (β = .23, p < .01). Perceived discrimination (β = .44, p < .001) and intragroup marginalization (β = .25, p < .01) were directly associated with depressive symptoms. Domains of acculturation and enculturation were not directly associated with either outcome.

Indirect Effects

Affective acculturation was indirectly associated (β = .07, p < .05) with alcohol use severity via perceived discrimination. Behavioral enculturation (β = -.09, p < .05) and affective enculturation (β = .07, p < .05) were indirectly associated with depressive symptoms via intragroup marginalization. Behavioral acculturation (β = -.09, p < .05) and affective acculturation (β = .13, p < .01) were indirectly associated with depressive symptoms via perceived discrimination.

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine mechanisms explaining associations of ethnocultural orientation with alcohol use and depressive symptoms within a bicultural transaction model. The model was partially supported in that acculturation domains were associated with perceived discrimination, but not with intragroup marginalization. Conversely, enculturation domains were associated with intragroup marginalization, but not with perceived discrimination. This underscores the value of using a bidimensional model of ethnocultural orientation, as each dimension can uniquely influence different negative cultural transactions.

As hypothesized, higher ethnic discrimination was associated with higher alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms. Higher intragroup marginalization was associated with more depressive symptoms, but was not significantly associated with alcohol use severity. These findings are consistent with the assertion that negative cultural transactions may increase the risk of adverse health outcomes (Lazarus, 1997).

As with other studies, domains of acculturation and enculturation were not directly associated with alcohol use severity or depressive symptoms (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Baezconde-Garbanati, Ritt-Olson, & Soto, 2012; Schwartz et al., 2011; Zamboanga, Raffaelli, & Horton, 2006). However, domains of acculturation and enculturation had indirect effects on alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms via ethnic discrimination and intragroup marginalization. Thus, ethnocultural orientation is nevertheless an important factor in alcohol use and depression by virtue of its indirect effects via negative cultural transactions.

These findings support the recommendation to examine indirect effects of ethnocultural orientations to identify the pathways through which they may affect health-related outcomes (Schwartz et al., 2007). Furthermore, multiple domains of acculturation and enculturation had unique and different indirect associations on alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms. This underscores the importance of using multifaceted measures of ethnocultural orientation in order to gain a clear understanding of its complex effects on health outcomes.

Clinical Implications

Findings from this study may have some clinical implications. For example, alcohol use and depression interventions may benefit from integrating coping and problem-solving skills to help late adolescent Hispanics more effectively manage experiences of discrimination (Edwards & Romero, 2008; Zayas, 2001). Similarly, interventions can address intragroup marginalization as a systemic family issue to be targeted at a family interactional level (Szapocznik et al., 1989). At the individual level, interventions may include cognitive restructuring techniques coping strategies to manage intragroup marginalization and prevent potential conflicts. Also, these issues can be incorporated into the training of mental health service providers via case vignettes with corresponding recommendations to address intragroup marginalization (see Castillo, 2009). Finally, negative feelings toward the receiving and heritage cultures may be reduced by promoting ethnic identity exploration and encouraging adolescents to gain knowledge about each group's history and cultural beliefs (Holcomb-McCoy, 2005).

Limitations

The study has some limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design, causal interpretations cannot be made. Second, self-report measures are vulnerable to participant misrepresentation or error. Third, the sample was composed of late adolescents in college that were predominantly of Mexican heritage. Studies are needed with samples that reflect the broader Hispanic population in more psychosocial stages of development. Lastly, the study was limited to negative cultural transactions. Future studies may examine if and how positive cultural transactions fit within the framework of the bicultural transaction model.

Conclusion

Operationalization of ethnocultural orientation has advanced to include both the acquisition of the receiving culture and maintenance of the heritage culture. Similarly, an explanatory framework of ethnocultural orientation and health outcomes might be enhanced by reflecting the experience of encounters with both the receiving and heritage cultures. In doing so, we may develop a more comprehensive understanding of ethnocultural orientation and health that can inform the modification and development of psychosocial health interventions.

Highlights.

18.2% of the variance in alcohol use severity and 24.3% of the variance in depressive symptoms were explained by the path model.

Higher reports of ethnic discrimination were associated with higher reports of alcohol use severity and depressive symptoms.

Higher reports of intragroup marginalization were associated with higher depressive symptoms.

None of the acculturation or enculturation domains had statistically significant direct effects with alcohol use severity or depressive symptoms.

Both ethnic discrimination and intragroup marginalization functioned as mediators of multiple domains of acculturation and enculturation.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by Grant R25 DA026401 funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Flórez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. 2nd. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castillo LG. The role of enculturation and acculturation on Latina college student distress. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education. 2010;9:221–231. doi: 10.1177/1538192710370899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Castillo LG, Castro Y, de Dios MA, Roncancio AM. Acculturative stress and depressive symptomatology among Mexican and Mexican American students in the US: Examining associations with cultural incongruity and intragroup marginalization. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 2014;36:136–149. doi: 10.1007/s10447-013-9196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, et al. Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: Examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;42:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Vaughan EL, de Dios MA, Castro Y, Roncancio AM, Ojeda L. Alcohol use severity among Hispanic emerging adults in higher education: Understanding the effect of cultural congruity. Substance Use and Misuse. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1018538. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG. The role of intragroup marginalization in Latino college student adjustment. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 2009;31:245–254. doi: 10.1007/s10447-009-9081-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Caver KA. Expanding the concept of acculturation in Mexican American rehabilitation psychology research and practice. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54:351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0017801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, Brossart DF, Quiros A. Construction and validation of the intragroup marginalization inventory. Cultural Diversity &Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:232–240. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheref S, Lane R, Polanco-Roman L, Gadol E, Miranda R. Suicidal ideation among racial/ethnic minorities: moderating effects of rumination and depressive symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;21:31–40. doi: 10.1037/a0037139. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar I, Arnold B, Maldonado R. Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: A revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1995;17:275–304. doi: 10.1177/07399863950173001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Des Rosiers SE, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Ham LS, Huang S. A cultural and social cognitive model of differences in acculturation orientations, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol-related risk behaviors among Hispanic college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69:319–340. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:24–39. doi: 10.1177/0739986307311431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes JN, Westbrook FD. Using the social, attitudinal, familial, and environmental (S.A.F.E.) acculturation stress scale to assess the adjustment needs of Hispanic college students. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 1996;29:67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb-McCoy C. Ethnic identity development in early adolescence: implications and recommendations for middle school counselors. Professional School Counseling. 2005;9:120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Evaluating model fit. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BSK, Abreu JM. Acculturation measurement: Theory, current instruments, and future directions. In: Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, Alexander CM, editors. Handbook of Multicultural Counseling. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. pp. 394–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kim BS, Omizo MM. Behavioral acculturation and enculturation and psychological functioning among Asian American college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2006;12:245–258. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.12.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Acculturation isn't everything. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01089.x.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Cortina LM. Towards an integrated understanding of Latino/a acculturation, depression, and smoking: A gendered analysis. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2013;1:3–20. doi: 10.1037/a0030951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D. Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among US Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Young adult drinking. Alcohol Alert. 2006;68:1–8. Retrieved from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa68/aa68.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, Santos LJ. Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:937–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Adolescent depression. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. 2nd. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009. pp. 444–466. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;7:385–401. doi: 10.1177/01466216770010030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Castillo LG, Ham LS, Huynh Q, Park IJK, et al. Cano MA. Dimensions of acculturation: Associations with health risk behaviors among immigrant college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:27–41. doi: 10.1037/a0021356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga B, Hernandez-Jarvis L. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Adolescences. 8th. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Santisteban D, Rio AT, Perez-Vidal A, Santisteban D, Kurtines WM. Family effectiveness training: An intervention to prevent drug abuse and problem behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1989;11:4–27. doi: 10.1177/07399863890111002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L. Predicting levels of Latino depression: Acculturation, acculturative stress, and coping. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:256–263. doi: 10.1037/a0017357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Zimmerman R, Gil A, Warheit GJ, Apospori E. Acculturation strain theory: Its application in explaining drug use behavior among Cuban and other Hispanic youth. Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:1943–1948. doi: 10.3109/10826089709035608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venegas J, Cooper TV, Naylor N, Hanson BS, Blow JA. Potential cultural predictors of heavy episodic drinking in Hispanic college students. American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:145–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Berry JW. Primary prevention of acculturative stress among refugees: Application of psychological theory and practice. American Psychologist. 1991;46:632–641. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.6.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Raffaelli M, Horton NJ. Acculturation status and heavy alcohol use among Mexican American college students: Investigating the moderating role of gender. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:2188–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH. Incorporating struggles with racism and ethnic identity in therapy with adolescents. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2001;29:361–373. doi: 10.1023/A:1012267230300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore SE. Acculturation and alcohol among Latino adults in the United States: A comprehensive review. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:1968–1990. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000191775.01148.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]