Abstract

Targeting of vascular intervention by systemically delivered supramolecular nanofibers after balloon angioplasty is described. Tracking of self-assembling peptide amphiphiles using fluorescence shows selective binding to the site of vascular intervention. Cylindrical nanostructures are observed to target the site of arterial injury, while spherical nanostructures with an equivalent diameter display no binding.

Keywords: Peptides, Supramolecular Chemistry, Self-assembly, Vascular Targeting

Cardiovascular interventions, such as bypass grafting, angioplasty, and stenting, are associated with high failure rates from restenosis.[1] Neointimal hyperplasia is one of the main causes of restenosis after vascular interventions. Current FDA-approved therapies to prevent neointimal hyperplasia are limited to drug-eluting stents, which deliver drugs locally to the site of injury.[2] Alternatively, a systemically delivered therapy that is targeted to the site of interest in the vasculature would offer several advantages: 1) the opportunity for drug delivery without the long-term presence of a foreign body material, such as a stents; 2) the ability to deliver multiple doses of a drug; 3) delivery of high local drug concentrations not possible with stents which are limited by their drug carrying surface area; and 4) avoidance of systemic side effects due to the targeted nature of the therapeutic. We report here the development of systemically delivered supramolecular nanostructures that target the site of arterial intervention. Following systemic delivery we found that targeted nanofibers localized to the site of arterial intervention, while targeted nanospheres of comparable diameter failed to bind. These nanostructures demonstrate that the integration of both specific targeting peptides and filamentous self-assembly leads to the optimal binding at the site of vascular intervention.

Substantial improvement of drug delivery methods with high efficacy and minimal toxicity will require nanoscale carriers that incorporate targeting information and are fully biocompatible. Nanostructures can display small molecules,[3] aptamers,[4] antibodies,[5] and proteins[6] on their surfaces to release drugs at a targeted site.[7] Creating a targeted vehicle through bottom up supramolecular design of a nanostructure requires the integration of shape and targeting chemistry. Filamentous polymer micelles were previously found to stay in the circulation ten times longer than spherical analogues.[8] In addition, the shape and aspect ratio of a nanoscale delivery vehicle may affect both its margination and adhesion to the vessel wall while in circulation.[9] With respect to the targeting moiety, specific binding to the desired area requires homing biomolecules with specific affinity to sites in the vasculature. Following arterial injury collagen IV, the most abundant protein in the basement membrane,[10] is exposed to circulating blood elements making it an ideal target for an intravascular therapy. Previous reports have used a collagen-binding peptide on lipid-polymeric nanoparticles to target sites of balloon angioplasty.[11] Follow up studies have used the same targeted drug carrier with a cancer chemotherapeutic agent, paclitaxel, to prevent neointimal hyperplasia.[12]

We describe the development and evaluation of a nanostructure built by self-assembly from a single molecule that targets areas of vascular intervention. The molecule used is a peptide amphiphile (PA) that self-assembles into supramolecular nanostructures in water.[13] PAs have been investigated for applications in regenerative medicine, biomedical applications,[14] and systemic delivery.[15] One of the supramolecular design possibilities with these molecules is the control of nanostructure shape by changing or deleting their β-sheet forming domain.[16] Furthermore, the high density of peptide segments on the nanostructure surface has been shown to be effective at delivering molecules either through covalent attachment or encapsulation.[17] Using a nanostructure based on PAs with a constant collagen-binding sequence but variable self-assembly domain, we demonstrate the shape-dependent binding of supramolecular nanostructures.

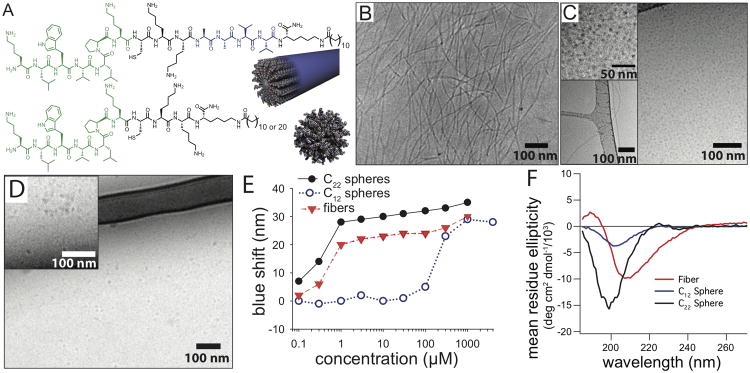

Three targeted PAs were synthesized to test the effects of nanostructure morphology on in vivo targeting. All three PAs contained the same collagen-binding peptide sequence (derived from previously performed phage display[11]), and an aliphatic tail; however, the β-sheet forming region (A2V2), present for the targeted nanofiber was removed from the targeted nanospheres (Figure 1A). Two types of PA nanospheres were synthesized; one had the same hydrophobic tail used in the nanofiber PA (C12-nanosphere), and one with a larger hydrophobic tail to probe the effects of increased hydrophobicityin the self-assembling molecules (C22-nanosphere). Other than these specific changes to the peptide sequence and hydrocarbon tail, the spheres and fibers were synthesized and prepared under the same conditions. Cryo-TEM revealed formation of filamentous structures in the case of the targeted nanofibers, which contains the β-sheet forming region (Figure 1B). The C22-nanosphere PA without a β-sheet forming region formed spherical nanostructures, roughly 10 nm in diameter(Figure 1C). Spheres were by far the dominant morphology but we did notice a few fibers by cryo-TEM (Figure 1C, lower left inset). Similar spherical structures were observed for C12-nanospheres (Figure 1D). These observations were confirmed by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), yielding slopes of -1 for the PA fiber, and 0 for both PA spheres, in the low-q region, which suggest the presence of cylindrical and spherical shapes, respectively. A polydisperse core-shell cylinder fit was applied to the core shell nanofiber, with a diameter of 6 nm (Figure S1). For the targeted nanospheres, a polydisperse core-shell sphere model indicates the presence of spheres with an average diameter of 10 nm and 5.4 nm, for the C12-nanosphere and the C22-nanosphere, respectively. Additionally, a control peptide of the binding peptide alone (KLWVLPKC) did not display any evidence of self-assembly by SAXS. These results demonstrate that the β-sheet region is necessary for the formation of a one-dimensional assembly, while a PA with only the targeted sequence and aliphatic tail is driven primarily by hydrophobic collapse to form nanoscale spheres. The vicinity of charged groups (lysines) next to the hydrophobic domain for C12-nanosphere and C22-nanosphere likely generated electrostatic repulsion instead of cohesive interactions from β-sheet hydrogen bonding, contributing to the formation of spherical micelles instead of fibers. A non-targeted nanofiber containing a scrambled binding sequence (PWKKLLV) was synthesized as a binding control for in vivo experiments. This PA also showed fiber formation by cryo-TEM and SAXS (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Collagen-targeting peptide amphiphiles assemble into nanofiber and nanospheres in aqueous solutions. (A) Structures and proposed nanostructures of the targeted nanofiber (top) and targeted nanospheres (bottom). The portion of the peptide shown in green is the collagen-targeting sequence, and the portion in blue is the β-sheet region for the nanofiber. (B) Cryo-TEM of the targeted nanofiber, (C) targeted C22-nanosphere, and (D) targeted C12-nanosphere. Upper-left insets in (C) and (D) are higher magnification image with enhanced contrast to show presence of spheres, while some fibers were observed as a minority population in C22-nanospheres (C, lower left insert). (E) Blue shift in maximum fluorescence emission wavelength of Nile red in the presence of PA fibers and spheres to determine critical aggregation concentrations.(F) Differences in secondary structure shown by circular dichroism of PA fibers and spheres.

The inclusion of the β-sheet region has a substantial effect on intermolecular packing and peptide secondary structure. Measurement of critical aggregation concentrations (CACs) were performed for the PAs that form spheres and fibers using the maximum fluorescence emission of the hydrophobic dye Nile Red. A blue shift in the maximal emission indicates the incorporation of Nile Red into the hydrophobic region of a self-assembled nanostructure.[18] A low CAC was observed for the targeted nanofiber (<300 nM), while the targeted C12-nanosphere had a much higher CAC, at approximately 300 μM, demonstrating that the β-sheet domain strongly contributed to when fibers appear (Figure 1E). For in vivo targeting, a low CAC is desirable to maintain nanostructure integrity after dilution into blood circulation. Comparable CACs of spheres and fibers are essential to generate a fair comparison of shape functionality in vivo. Based on Nile Red fluorescence, the C22-nanosphere PA displayed a similar curve to that of the fiber-forming PA with an observed CAC of less than 300 nM. Administration of 1.0 ml of a 1.3 mM solution of the nanofibers via tail vein injection results in a plasma concentration of PA of 22 ± 3 μM after 5 minutes. The plasma concentration achieved is two orders of magnitude over the calculated CAC, which suggests that the supramolecular structures remain intact after systemic administration. Furthermore, cryo-TEM of the targeted nanofiber at a concentration of 200 μM in a solution containing 10% fetal bovine serum showed the presence of intact fibers, suggesting that serum proteins do not disrupt PA self-assembly, and that the CAC is sufficiently low enough to maintain nanostructure integrity in vivo (Figure S3). Additionally, circular dichroism results showed more β-sheet character for the targeted nanofiber when compared to both, targeted nanospheres (C12 and C22) or the targeting peptide, which displayed a random coil conformation (Figure 1F). This difference in secondary structure likely contributed to the distinct self-assembly behavior of the cylinders and spheres. The hydrogen bonding forming β-sheet structures produced assemblies for the targeted nanofiber at much lower concentrations relative to the targeted C12-nanosphere, while the difference in hydrophobicity likely contributed to the morphology differences between the PA fiber and C22-nanosphere.

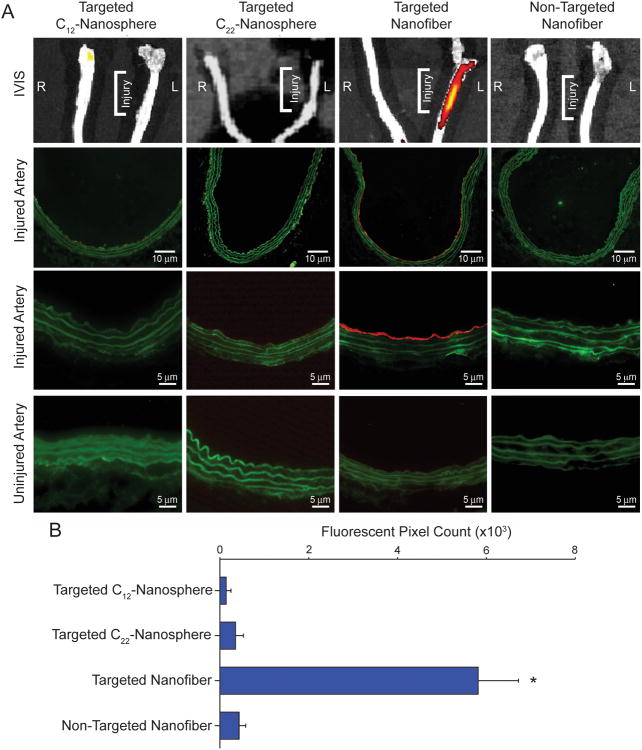

The rat carotid balloon injury model was used to investigate the binding of the targeted nanospheres, targeted nanofibers, and non-targeted nanofibers. PA molecules, which assembled into either spheres or fibers, were labeled via a cysteine-maleimide reaction with AlexaFluor 546 for visualization in vivo. After injection of the fluorescently-labeled nanostructures, binding to the injured artery was observed only with the targeted nanofiber (P<0.05, Figure 2). In all cases, no binding was observed on the uninjured contralateral artery. Arterial cross-sections of the respective arteries confirmed binding of the targeted nanofiber to nearly the entire circumference of the injured artery, while a nanofiber with a scrambled targeting sequence displayed no binding. Higher magnification revealed binding of the targeted nanofiber to the luminal surface demonstrating that the nanofiber does not penetrate into the tissue upon binding (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In vivo targeting of targeted and non-targeted nanostructures. A) Fluorescent image of gross injured and uninjured carotid arteries (top row) and arterial cross-sections of injured left carotid artery at lower magnification (2nd row) and higher magnification (3rd row), and right uninjured carotid artery (4th row). B) Graphical representation of the quantification of positive fluorescent signal from the arterial cross-sections. *P<0.05 versus all other treatment groups.

To compare the effect of shape, both C12-nanosphere and C22-nanosphere were injected in the same manner as the nanofiber. Binding of the C12-spherical nanostructures containing the targeting sequence and a diameter comparable to that of the nanofibers or of the non-targeted nanofibers was not observed on arterial cross-sections (Figure 2). Because of the high CAC value, the C12-nanospheres could disassemble quickly after tail vein injection. To address this issue, C22-nanospheres with similar CAC to fibrous nanostructures were tested. These spherical nanostructures, with a CAC similar to that of the targeted fiber, also did not show any binding to the site of vascular injury (Figure 2).

These results suggest that the supramolecular shape of the nanostructures has a profound impact on binding. One possible explanation for this effect is a difference in circulation time between the spheres and fibers; the nanofiber may be cleared from circulation at a slower rate relative to spheres of similar dimensions.[8] Differential biodistribution and/or pharmacokinetics of the materials could also partially account for the observed preferential binding of the targeted nanofibers. Since very little is known about how self-assembled nanoparticles such as these behave in the systemic circulation, future work of ours will concentrate on studying the biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and biosafety of these delivery vehicles. Lastly, the disparity between sphere and cylinder binding could be explained by the multivalent presentation of peptides along the long-axis of the cylinder, increasing the number of potential binding sites of the nanofiber to exposed collagen. Binding of polymer spherical nanoparticles 50 nm in diameter was previously reported using the same collagen-binding sequence.[11-12] Interestingly, the 10 nm spherical micelles investigated here do not have the capacity to bind to the arterial lumen possibly because of the small surface area of contact with the wall. We have demonstrated that both the targeting sequence and the filament-like shape with dimensions on the low end of the nanoscale range were essential to bind to the injured artery in vivo. From a therapeutic standpoint, there could be advantages to the use of vehicles in the low nanoscale range, especially if morphology and at least one dimension of their size is precisely controlled.

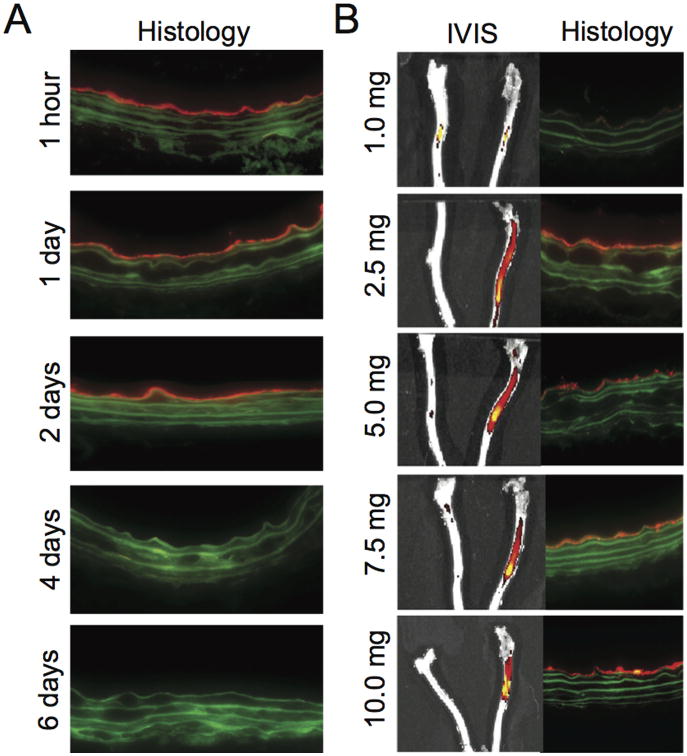

Duration of binding of the targeted nanofiber to the injured vessel was determined by arterial harvest at various time periods after injection. Targeted nanofiber binding to the injured vessel was observed for up to 2 days; after this time, binding was no longer detected (Figure 3A). While fluorescence is an indirect measurement and not a measurement of intact PA, the presence of the fluorophore for two days at the site of injury suggests a local persistence of the nanofiber. Binding for this period of time is ideal for treatment purposes, since cell proliferation in the arterial wall has been shown to peak 3 days after angioplasty.[19]

Figure 3.

Time and dose dependence of nanofiber targeting. (A) Cross-sectional fluorescence imaging of injured carotid arteries from animals injected with the targeted nanofiber (5.0 mg). (B) Fluorescent images of gross and 200× cross sections of uninjured and injured carotid arteries 1 hour after injection of the targeted nanofiber at various doses.

To determine the optimal dose of targeted nanofibers for subsequent in vivo studies, animals were injected with a range of concentrations, from 1 to 10 mg. The lowest dose tested of targeted nanofiber that produced binding to the injured vessel detectable by histology was 1.0 mg; however, there was no difference in bulk fluorescence detectable by IVIS (Figure 3B). Quantification of the fluorescent signal on the arterial cross-sections revealed a statistically significant increase in fluorescent signal with injection of 2.5 mg versus 1.0 mg (P=0.019). There was a trend toward an increase with 5.0 vs. 1.0 mg (P=0.056) and 10.0 vs. 1.0 mg (P=0.096) but these did not reach statistical significance (Figure S6). No statistically significant differences were noted between 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0 mg. These data suggest that injection of 2.5 mg may result in a concentration at which further nanofibers could no longer bind to the wall, indicating complete luminal binding at the site of injury.

We have demonstrated here shape-dependent targeting of nanostructures to injured vasculature. The presence of a β-sheet forming domain drives self-assembly of PAs into nanofibers through hydrogen bonding. When displaying a collagen-targeting sequence in these systems, the nanofibers revealed binding to the site of vascular intervention relative to both targeted spherical micelles and non-targeted nanofiber controls. Binding was observed for up to two days after injection, demonstrating that a peptide-based targeted therapy has potential as a drug delivery therapeutic. Overall, the targeted nanofiber represents a novel platform for targeting sites in the vascular system.

Experimental Section

PA Synthesis

The collagen-targeting PAs and peptides were synthesized using standard Fmoc solid-phase synthesis conditions as described previously.[20] All PAs were synthesized on a Rink Amide MBHA resin LL (EMD Millipore). A Fmoc-lysine(mtt) was first coupled to the resin and then deprotected for 5×2 minutes in 93% dichloromethane (DCM), 2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and 5% triisopropylsilane (TIPS). The hydrophobic tail was then coupled to the lysine side chain using 8 equivalents of dodecanoic acid (C12 spheres and fibers) or docosanoic acid (C22 spheres) with N, N, N′, N′-Tetramethyl-O-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)uronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU)(7.9 eq) and diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) (12 eq) in dimethylformamide (DMF), DCM, and N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) (2:1:1). Docosanoic was dissolved in a higher percentage of DCM to improve solubility. The remaining amino acids were coupled using standard Fmoc-chemistry. PAs were cleaved in a 90% TFA, 5% 2, 2′-(ethylenedioxy)diethanethiol, 2.5% TIPS, and 2.5% H2O solution for two hours and subsequently precipitated in cold diethyl ether. PAs were then dissolved in H2O with 0.1% TFA and purified by HPLC on a C8 Jupiter column. PA purity was determined after purification by LC/MS (Figure S4). Fluorescent labeling of the collagen-targeting PA was achieved by reacting AlexaFluor 546-maleimide with four times excess of the targeted nanofiber or nanosphere in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4) (Figure S5). Any unreacted dye was removed by dialysis overnight in a 4k MWCO membrane. Both fluorescently-labeled PA and unlabeled PA were dissolved in hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), an organic solvent known to disrupt hydrogen bonds, and mixed together for at least 15 min. Samples were lyophilized to dryness to form a powder. After lyophilization in HFIP, samples were dissolved in water, aliquoted, and lyophilized again. The final percentage of fluorescently-labeled PA was 1.8 mol% relative to total PA concentration.

Materials Characterization

Cryo-TEM images were obtained on a JEOL 1230 TEM at 100 kV. For the targeted and scrambled nanofibers, PAs were dissolved at concentrations of 250 μM, while spherical micelles were dissolved at 5 mM to ensure visualization while imaging. Samples were prepared using an FEI Vitrobot, plunged into liquid ethane, and stored in liquid nitrogen until imaging. SAXS experiments were carried out at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory using previously described protocols.[20] Briefly, samples were dissolved at a concentration of 5 mM, inserted into a 1.5 mm quartz capillary, and irradiated with a 15 keV x-ray beam for 5 s. Circular dichroism experiments were performed at 1mM in a diluted phosphate buffer on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrophotometer. Additional information is available in the supplementary information. Critical aggregation concentrations (CACs) were determined by measuring maximum emission wavelength of Nile red. Nile red, dissolved in ethanol, was added to solutions of PAs or peptides for a final Nile Red concentration of 250 nM. The final concentration of ethanol was kept to a minimum (<0.5%) to prevent disruption of the assemblies. Fluorescence was measured using a Nanolog HJ Fluorometer.

Animal Surgery

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 350 to 400 g underwent carotid artery balloon injury as previously described [21]. After balloon injury, the arteriotomy was ligated and heparin 50 units/kg was injected through the tail vein of the animal. After the heparin circulated for 10 min, the different nanostructures, dissolved in 1 mL of Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), were injected via tail vein into the animal. Blood flow was then restored to the common carotid artery and the neck incision was closed. Rats were euthanized at 1 h, 1, 2, 4, 6 or 14 days post-injection, based on the experiment being conducted. The number of animals per treatment group for the different experiments is as follows: for the binding of the nanofibers, n=6/treatment group; for the binding of the nanospheres, n=2/treatment group; for the binding duration study, n=3/treatment group; for the concentration study, n≥1/treatment group.

Tissue Processing

Carotid arteries and viscera were harvested after in-situ perfusion with PBS (250 mL) and placed in 2% paraformaldehyde overnight for fixation. Tissue was processed as previously described.[21]

Fluorescent Imaging

Carotid arteries harvested at respective time points underwent fluorescent imaging. Digital images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM-510 microscope (Hallbergmoos, Germany) with a 40× objective, HE Cy3 filter (Zeiss filter #43), using excitation and emission wavelengths of 550-575 nm and 605-670 nm, respectively. To assess binding of the nanostructures, the fluorescent pixels of the arterial cross-sections were quantified in high power field (20× objective) images using Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical Analysis

All results are given as mean ± the standard error of the mean. Sigma Stat (Sys Stat Software, Inc. San Jose) was used to determine differences between multiple groups by performing one-way analysis of variance and using the Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test for all pair-wise comparisons. Non-normally distributed data were analyzed by an ANOVA on ranks with the Dunn's post hoc test. Statistical significance was assumed when P<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Bioengineering Research Partnership 1R01HL116577-01), a Catalyst Award from the Louis A. Simpson and Kimberly K. Querrey Center for Regenerative Nanomedicine at Northwestern University, as well as Research Seed Funding from the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. TJM was supported by a graduate research fellowship from the National Science Foundation; HAK was supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 vascular surgery training grant (T32HL094293); and ESMB is supported by a postdoctoral research fellowship from the American Heart Association (13POST16090011). We acknowledge the Bioimaging Facility (BIF), Cell Imaging Facility (CIF), Keck Biophysics Facility, and Peptide Core Facility at Northwestern University. The BIF and CIF are supported, in part, by the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Grant Number UL1TR000150 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. SAXS results were obtained at the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team (DND-CAT) located at Sector 5 of the Advanced Photon Source (APS). DND-CAT is supported by E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., The Dow Chemical Company, and Northwestern University. Use of the APS, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- 1.Gröschel K, Riecker A, Schulz JB, Ernemann U, Kastrup A. Stroke. 2005;36:367–373. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152357.82843.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastrati A, Mehilli J, von Beckerath N, Dibra A, Hausleiter J, Pache J, Schühlen H, Schmitt C, Dirschinger J, Schömig A. Jama. 2005;293:165–171. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hrkach J, Von Hoff D, Ali MM, Andrianova E, Auer J, Campbell T, De Witt D, Figa M, Figueiredo M, Horhota A, Low S, Mc Donnell K, Peeke E, Retnarajan B, Sabnis A, Schnipper E, Song JJ, Song YH, Summa J, Tompsett D, Troiano G, Van Geen Hoven T, Wright J, Lo Russo P, Kantoff PW, Bander NH, Sweeney C, Farokhzad OC, Langer R, Zale S. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:12839–12839. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farokhzad OC, Jon S, Khademhosseini A, Tran TNT, LaVan DA, Langer R. Cancer Research. 2004;64:7668–7672. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian X, Peng XH, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie S. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;26:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nbt1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Nature. 2010;464:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Choi CHJ, Alabi CA, Webster P, Davis ME. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:1235–1240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914140107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vance D, Martin J, Patke S, Kane RS. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2009;61:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geng Y, Dalhaimer P, Cai S, Tsai R, Tewari M, Minko T, Discher DE. Nature Nanotechnology. 2007;2:249–255. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Decuzzi P, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Ferrari M. Pharm Res. 2008;26:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Doshi N, Prabhakarpandian B, Rea-Ramsey A, Pant K, Sundaram S, Mitragotri S. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;146:196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LeBleu VS, MacDonald B, Kalluri R. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2007;232:1121–1129. doi: 10.3181/0703-MR-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan JM, Zhang L, Tong R, Ghosh D, Gao W, Liao G, Yuet KP, Gray D, Rhee JW, Cheng J, Golomb G, Libby P, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:2213–2218. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914585107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan JM, Rhee JW, Drum CL, Bronson RT, Golomb G, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:19347–19352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115945108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Cui H, Webber MJ, Stupp SI. Biopolymers. 2010;94:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bip.21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matson JB, Stupp SI. Chemical Communications. 2012;48:26–33. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15551b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soukasene S, Toft DJ, Moyer TJ, Lu H, Lee HK, Standley SM, Cryns VL, Stupp SI. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9113–9121. doi: 10.1021/nn203343z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a Cui H, Muraoka T, Cheetham AG, Stupp SI. Nano Lett. 2009;9:945–951. doi: 10.1021/nl802813f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Muraoka T, Koh CY, Cui H, Stupp SI. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:5946–5949. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pashuck ET, Stupp SI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8819–8821. doi: 10.1021/ja100613w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Kapadia MR, Chow LW, Tsihlis ND, Ahanchi SS, Eng JW, Murar J, Martinez J, Popowich DA, Jiang Q, Hrabie JA, Saavedra JE, Keefer LK, Hulvat JF, Stupp SI, Kibbe MR. Journal of vascular surgery. 2008;47:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Matson JB, Webber MJ, Tamboli VK, Weber B, Stupp SI. Soft matter. 2012;8:2689–2692. doi: 10.1039/C2SM25785H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soukasene S, Toft DJ, Moyer TJ, Lu H, Lee HK, Standley SM, Cryns VL, Stupp SI. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9113–9121. doi: 10.1021/nn203343z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minkenberg CB, Li F, van Rijn P, Florusse L, Boekhoven J, Stuart MC, Koper GJ, Eelkema R, van Esch JH. Angewandte Chemie. 2011;123:3483–3486. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik N, Francis SE, Holt CM, Gunn J, Thomas GL, Shepherd L, Chamberlain J, Newman CM, Cumberland DC, Crossman DC. Circulation. 1998;98:1657–1665. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.16.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toft DJ, Moyer TJ, Standley SM, Ruff Y, Ugolkov A, Stupp SI, Cryns VL. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7956–7965. doi: 10.1021/nn302503s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vavra AK, Havelka GE, Martinez J, Lee VR, Fu B, Jiang Q, Keefer LK, Kibbe MR. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry / official journal of the Nitric Oxide Society. 2011;25:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.