Abstract

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression is a risk factor for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). A 57% decline in creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFRcr) is an established surrogate outcome for ESRD in clinical trials, and 30% decrease has recently been proposed as a surrogate endpoint. However, it is unclear if change in novel filtration markers provides additional information for ESRD risk to change in eGFRcr.

Study Design

Cohort study.

Setting & Participants

Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study participants from four US communities

Predictors

Percent change in filtration markers (eGFRcr, cystatin C–based eGFR (eGFRcys), the inverse of β2-microglobulin concentration [1/B2M]) over a 6-year period.

Outcome

Incident ESRD.

Measurements

Cox proportional hazards regression with adjustment for demographics, kidney disease risk factors, and first measurement of eGFRcr.

Results

During a median follow-up of 13 years, there were 142 incident ESRD cases. In adjusted analysis, declines of >30% in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M were significantly associated with ESRD compared to stable concentrations of filtration markers (HRs of 19.96 [95% CI, 11.73-33.96], 16.67 [95% CI, 10.27-27.06], and 22.53 [95% CI, 13.20-38.43], respectively). Using the average of declines in the three markers, >30% decline conferred higher ESRD risk than that for eGFRcr alone (HR, 31.97 [95% CI, 19.40-52.70; p=0.03] vs. eGFRcr).

Limitations

Measurement error could influence estimation of change in filtration markers.

Conclusions

A >30% decline in kidney function assessed using novel filtration markers is strongly associated with ESRD, suggesting the potential utility of measuring change in cystatin C and B2M in settings where improved outcome ascertainment is needed, such as clinical trials.

Keywords: β2-microglobulin (B2M), creatinine, cystatin C, filtration marker, chronic kidney disease (CKD), disease progression, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), kidney disease outcome, surrogate endpoint

A doubling of serum creatinine, equivalent to a 57% decline in creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFRcr), is an established surrogate endpoint for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in clinical trials.1,2 However, a decline of this magnitude may take decades to develop.3,4 Thus, the US Food and Drug Administration and National Kidney Foundation sponsored a large effort to evaluate the prognostic value of smaller changes in eGFRcr. The investigators concluded that a 57% decline was strongly associated with ESRD but rare, whereas a 30% decline in eGFRcr was an order of magnitude more common but perhaps sufficiently robust as a surrogate of future ESRD risk.5,6

eGFRcr is an imperfect measure of kidney function, owing to variability in creatinine due to its non-GFR determinants, such as muscle mass and dietary protein intake.7 Novel markers of kidney filtration, individually or combined with serum creatinine, have been shown to improve estimation of directly measured GFR.8,9 Two such proteins, cystatin C (13.3 kDa) and β2-microglobulin (B2M; 11.8 kDa), are freely filtered by the glomerulus, absorbed, and fully degraded by the proximal tubules.10,11 Cystatin C and B2M may be influenced by different non-GFR determinants such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, inflammation, smoking, blood pressure, and cholesterol.10-18 As individual markers, cystatin C–based eGFR (eGFRcys) and 1/B2M are strongly associated with kidney disease outcomes, similar to or perhaps even more so than eGFRcr.16,19-22 Furthermore, the use of multiple markers in combination may improve ESRD risk estimation, beyond eGFRcr alone.22,23 However, the usefulness of change in these novel kidney filtration markers as surrogates for chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression is not known.

Our objective was to determine whether percent change in novel kidney filtration markers (eGFRcys and 1/B2M) over a six-year period were independently associated with increased risk of ESRD during 15 years of follow-up within a community-based population.

METHODS

Study Design

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study is a community-based, prospective cohort study of 15,792 healthy, middle-aged, predominantly black and white men and women initially recruited in 1987-1989 from four US communities: Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Jackson, Mississippi; and suburbs of Minneapolis, Minnesota. In the overall ARIC Study population at the time of enrollment, participants were 45-64 years of age, 55.2% were women, and 27.0% were African-American. More details about the ARIC study design are provided elsewhere.24

Study Population

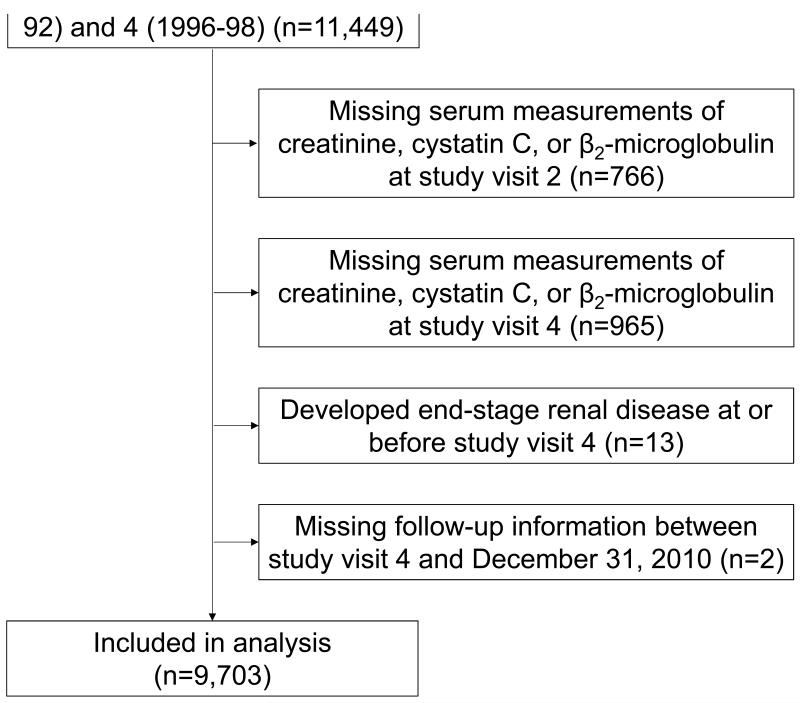

Our study population consisted of ARIC Study participants with measured values for creatinine, cystatin C, and B2M at two time points: ARIC study visits 2 (1990-1992) and 4 (1996-1998). Participants with ESRD at or before visit 4 were excluded from the analysis (n=13). After exclusions, the analytic sample size in the present study was 9,703 (Figure 1). Participants provided written documentation of informed consent at each study visit, and procedures were approved by the institutional review board at each study center.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Study Participant Selection

Data Collection

During each study visit, trained staff administered questionnaires to participants to collect information on demographics (age, race, sex) and kidney disease risk factors (medical history, medication use, cigarette smoking status). Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2 using measurements taken while participants wore light clothing without shoes. Two seated measurements of blood pressure were taken by a certified technician using a random-zero sphygmomanometer after five minutes of rest, and the mean of the measurements was used for analysis. Study participants provided 12-hour fasting blood samples and spot urine samples at both measurement times. Blood samples were centrifuged within 30 minutes of collection at 3,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C and stored at −70°C for future laboratory analysis. High-density cholesterol was measured enzymatically after precipitation with dextran sulfate-magnesium.25 Total cholesterol was determined automatically after oxidation by cholesterol oxidase and measured colorimetrically.26

Kidney Filtration Markers

Creatinine was measured at study visit 2 in serum specimens and at study visit 4 in plasma specimens according to the original study protocol by the modified kinetic Jaffe method. In 2012-2013, cystatin C was measured using the Gentian immunoassay (Gentian, Moss, Norway) and B2M was measured using Roche β2-microglobulin reagent on the Roche Modular P800 Chemistry analyzer in stored serum samples collected at study visit 2. In 2010, cystatin C and B2M were measured using a particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay with a BNII nephelometer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics) using stored plasma samples collected at study visit 4. Creatinine, cystatin C, and B2M values were standardized and calibrated to account for differences in methods across laboratories.27 eGFRcr and eGFRcys were calculated using the 2009 CKD-EPI (CKD Epidemiology Collaboration) creatinine equation and 2012 CKD-EPI cystatin C equation, respectively.8,28 For ease of comparison to GFR estimates, we calculated the inverse of the values for B2M. The primary exposure of interest was percent change in circulating concentrations of filtration markers between the first measurement (study visit 2, 1990-1992) and the last measurement (study visit 4, 1996-1998) as a proportion of the first measurement. The three marker composite was calculated as: (percent change in eGFRcr + percent change in eGFRcys + percent change in 1/B2M)/3.

Definition of ESRD

Incident ESRD was defined as entry into the US Renal Data System (USRDS) registry between study visit 4 (1996-1998) through the end of follow-up (December 31, 2010). The USRDS registry consists of individuals receiving kidney dialysis or kidney transplant based upon the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medical Evidence Form-2728 as reported within 45 days of initiation of renal replacement therapy. As a sensitivity analysis, we used an alternative outcome—incident kidney failure—encompassing treated and untreated kidney failure and death due to kidney failure, which has been previously described and validated (C.M.R., manuscript under consideration).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation, median with interquartile range, and proportion) were used to assess baseline participant characteristics, concentrations of and percent change in filtration markers, and ESRD according to categories of percent change in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M (greater than 30% decline [< −30%]; 10%-30% decline [-30% to −10%]; less than 10% decline to less than 10% increase [> −10% to < 10%; denoted as −9.9% to 9.9% for convenience], and 10% or greater increase [≥ 10%]). Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the relationship between percent change in the filtration markers (eGFRcr, eGFRcys, 1/B2M).

To assess the independent effect of percent change in kidney filtration markers on risk of incident ESRD, Cox proportional hazards regression was used with adjustment for demographics (age, sex, race) and kidney disease risk factors (body mass index, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, diabetes status, total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, history of coronary heart disease, and current cigarette smoking status). In separate models, we additionally adjusted for first measurement of eGFRcr.

In addition to categories of percent change, percent change in filtration markers was modelled continuously using linear spline terms with one knot at 0%. Hazard ratios (HRs) for ESRD risk were estimated per 30% decline in the filtration marker (i.e. negative percent change). Seemingly unrelated regression was used to test for difference in the coefficient for continuous decline in an individual filtration marker (eGFRcys, 1/B2M) or three marker composite and ESRD risk compared to the coefficient for continuous decline in eGFRcr and ESRD risk.

As a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted for first measurement of the respective filtration marker (i.e. first measurement of eGFRcys, first measurement of 1/B2M) instead of first measurement of eGFRcr. For the three marker composite, we adjusted for first measurement eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M. Albuminuria was not measured at the same ime point as the other covariates (study visit 2, 1990-1992). We therefore adjusted for albuminuria at the second time point (study visit 4, 1996-1998) in a sensitivity analysis. In addition to the three-marker composite, other combinations of filtration markers were explored in sensitivity analyses, including the average of percent change in two markers (eGFRcr and eGFRcys; eGFRcr and 1/B2M; eGFRcys and 1/B2M) and a risk score determined by the number of filtration markers that declined greater than 30% (range, 0-3). Competing risk regression was used to account for the competing risk of death.30 Analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Among 9,703 study participants, 142 (1.5%) reached ESRD during a median follow-up of 13.1 years. During the six years between study visits, over half of the study population had “stable” eGFRcr (defined as a change from baseline between −9.9% and +9.9%) and 7% of participants had greater than 30% decline in eGFRcr (Table 1). Compared to participants with stable eGFRcr, those with greater than 30% decline in eGFRcr were more likely to be older, black, and have a higher body mass index. In addition, those with greater than 30% decline in eGFRcr were more likely to have higher systolic blood pressure and to have diabetes, and to be taking anti-hypertensive medication. Median initial eGFRcr values were 95.8, 96.7, 99.0, and 78.6 mL/min/1.73 m2 among those with greater than 30% decline, 10%-30% decline, with stable eGFRcr, and 10% or greater increase, respectively (Table 2). Baseline demographic characteristics and risk factors demonstrated similar patterns by categories of percent change in eGFR based on cystatin C (eGFRcys) and 1/B2M (Tables S1 and S2, available as online supplementary material).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Risk Factors Assessed at Baseline

| Category of Percent Change in eGFRcr Over 6 Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < −30% | −30% to −10% | −9.9% to 9.9% | ≥ 10% | |

| No. of participants | 657 (6.8%) | 3,588 (37.0%) | 5,004 (51.6%) | 454 (4.7%) |

| Age (y) | 58.3 ±5.7b | 56.8 ±5.7 | 56.5 ±5.6 | 56.3 ±5.5 |

| Female sex | 404 (61.5%) | 2,004 (55.9%) | 2,893 (57.8%) | 274 (60.4%) |

| Black race | 226 (34.4%)b | 881 (24.6%)b | 856 (17.1%) | 104 (22.9%)b |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.9 ±5.7b | 27.6 ±5.1 | 27.8 ±5.3 | 28.7 ±5.6b |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 127.9 ±21.8b | 120.6 ±18.3b | 119.1 ±16.8 | 120.0 ±17.9 |

| Anti-hypertensive medication use | 303 (46.1 %)b | 1,103 (30.7%)b | 1,336 (26.7%) | 188 (41.4%)b |

| Diabetes mellitus | 169 (25.8%)b | 428 (11.9%) | 568 (11.4%) | 68 (15.0%) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 213.1 ±41.7 | 207.8 ±37.6 | 209.0 ±37.5 | 212.6 ±47.3 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48.5 ±16.6b | 50.2 ±16.6 | 50.6 ±17.0 | 48.9 ±15.4 |

| History of coronary heart disease | 69 (10.6%)b | 212 (6.0%) | 249 (5.1%) | 27 (6.1%) |

| Current smoker | 127 (19.4%) | 677 (18.9%) | 961 (19.2%) | 76 (16.7%) |

| ACR categoryc | ||||

| <30 mg/g | 493 (76.1%) | 3,285 (92.5%) | 4,642 (93.4%) | 410 (91.3%) |

| 30-300 mg/g | 94 (14.5%) | 219 (6.2%) | 285 (5.7%) | 30 (6.7%) |

| >300 mg/g | 61 (9.4%) | 49 (1.4%) | 41 (0.8%) | 9 (2.0%) |

Note: N=9,703. Baseline is study visit 2 (1990-1992). Values for categorical variables are given as number (percentage); values for continuous variables are given as mean ± standard deviation. Conversion factor for cholesterol in mg/dL to mmol/L, ×0.02586.

p<0.05 for comparison to reference group (−9.9% to +9.9% change in eGFRcr category)

Urine ACR was measured at study visit 4 (1996-1998) only

ACR, albumin-creatinine ratio; eGFRcr, creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high-density lipoprotein;

Table 2.

ESRD, Concentrations of Filtration Markers, and Percent Change in Filtration Markers

| Category of Percent Change in Filtration Marker Over 6 Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < −30% | −30% to −10% | −9.9% to 9.9% | ≥ 10% | |

| eGFRcr | ||||

| No. of participants | 657 (6.8%) | 3,588 (37.0%) | 5,004 (51.6%) | 454 (4.7%) |

| Incident ESRD | 76 (11.6%)a | 44 (1.2%)a | 19 (0.4%) | 3 (0.7%) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)b | 10.80 (8.63-13.52)a | 0.99 (0.74-1.33)a | 0.31 (0.20-0.48) | 0.53 (0.17-1.65) |

| First valuec | 95.8 (86.5, 104.6)a | 96.7 (88.4, 106.5)a | 99.0 (92.6, 105.3) | 78.6 (70.4, 83.4)a |

| Last valuec | 60.1 (50.6, 67.0)a | 78.6 (71.8, 88.7)a | 94.2 (88.6, 100.3) | 91.0 (85.1, 99.1 )a |

| Percent changec | −35.3 (−42.2, −32.6)a | −15.5 (−22.4, −13.8)a | −3.1 (−8.5, −1.5) | 15.8 (11.7, 23.3)a |

| eGFRcys | ||||

| No. of particpants | 555 (5.7%) | 3,562 (36.7%) | 4,946 (51.0%) | 640 (6.6%) |

| Incident ESRD | 53 (9.6%)a | 54 (1.5%)a | 26 (0.5%) | 9 (1.4%) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)b | 9.49 (7.25-12.43)a | 1.23 (0.94-1.60)a | 0.42 (0.29-0.62) | 1.18 (0.61-2.27) |

| First valuec | 89.5 (75.1, 101.9)a | 97.5 (85.3, 106.0)a | 95.5 (80.7, 105.8) | 72.5 (63.1, 81.6)a |

| Last valuec | 50.0 (28.6, 63.1 )a | 79.8 (70.7, 88.8)a | 93.0 (79.3, 101.3) | 86.7 (76.0, 95.9)a |

| Percent changec | −39.5 (−58.1, −33.3)a | −15.7 (−20.4, −12.6)a | −3.7 (−6.8, 0.6) | 16.1 (12.9, 22.9)a |

| 1/B2M | ||||

| No. of participants | 500 (5.2%) | 3,332 (34.3%) | 4,878 (50.3%) | 993 (10.2%) |

| Incident ESRD | 58 (11.6%)a | 55 (1.7%)a | 20 (0.4%) | 9 (0.9%) |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)b | 11.64 (9.00-15.06)a | 1.36 (1.04-1.77)a | 0.33 (0.21-0.51) | 0.72 (0.37-1.38) |

| First valuec | 0.52 (0.44, 0.61 )a | 0.57 (0.50, 0.64)a | 0.55 (0.49, 0.62) | 0.50 (0.43, 0.57)a |

| Last valuec | 0.32 (0.25, 0.39)a | 0.47 (0.41, 0.53)a | 0.53 (0.48, 0.61) | 0.59 (0.52, 0.67)a |

| Percent changec | −36.5 (−44.4, −32.7)a | −15.8 (−20.4, −12.6)a | −2.3 (−6.2, 2.4) | 17.5 (12.9, 24.3)a |

| 3-Marker composite^ | ||||

| No. of participants | 347 (3.6%) | 3,638 (37.5%) | 5,393 (55.6%) | 325 (3.4%) |

| Incident ESRD | 60 (17.3%)a | 51 (1.4%)a | 25 (0.5%) | 6 (1.9%)a |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)b | 18.95 (14.71-24.40)a | 1.14 (0.87-1.51)a | 0.37 (0.25-0.55) | 1.53 (0.69-3.40)a |

| Percent changec | −36.0 (−43.9, −32.7)a | −15.0 (−19.0, −12.3)a | −4.1 (−7.1, 0.2) | 15.3 (12.1, 21.5)a |

Note: N=9,703. Unless otherwise indicated, values are given as number (percentage) or median [interquartile range].

B2M, β2-Microglobulin; CI, confidence interval; eGFRcr, creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate-creatinine; eGFRcys, cystatin C–based estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease

p<0.05 for comparison to reference group (−9.9% to +9.9% change in eGFRcr category)

Incidence rate per 1,000 person-years

Median [interquartile range] for first measurement (study visit 2 [1990-1992]), last measurement (study visit 4 [1996-1998]), and percent change [(first measurement – last measurement)/first measurement]

3-Marker Composite: mean of percent change in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M

Percent change in eGFRcr was moderately, positively correlated with percent change in eGFRcys (r = 0.35) and percent change in 1/B2M (r = 0.36). Percent change in eGFRcys was strongly, positively correlated with 1/B2M (r = 0.56).

Compared to eGFRcr, there were fewer individuals with greater than 30% decline in other filtration markers (eGFRcys, 1/B2M) and the average of change in all three filtration markers (three-marker composite; Table 2). However, the incidence of ESRD in the greater than 30% decline category was similar for eGFRcys and 1/B2M, and higher for the composite of all three markers compared to eGFRcr.

For the individual filtration markers, participants with greater than 30% decline in the filtration marker had 17- to 23-times higher risk of ESRD than those with a stable concentration of the filtration marker (−9.9% to 9.9% change from baseline) after adjustment for demographic characteristics, established risk factors for kidney disease, as well as first measurement of eGFRcr (Table 3). Participants with 10%-30% decline in an individual filtration marker had statistically significant two- to four-times higher risk of ESRD than those with a stable concentration of the filtration marker. Decline in eGFRcr was more strongly associated with risk of ESRD than decline in eGFRcys (p<0.001) and not significantly different than 1/B2M (p=0.9). The association between 10% or greater increase in individual filtration markers and ESRD risk was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios for ESRD by Percent Change in Filtration Markers Over 6 Years

| Categorical Percent Change | Continuous Percent Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < −30% | −30% to −10% | −9.9% to 9.9% | ≥ 10% | Per −30%c | P vs. eGFRcrd | |

| Adjusted for covariatesa | ||||||

| eGFRcr | 21.42 (12.62, 36.36) | 2.92 (1.68, 5.07) | 1.00 (reference) |

1.42 (0.42, 4.83) | 11.70 (8.80, 15.58) | -- |

| eGFRcys | 16.34 (10.05, 26.56) | 2.92 (1.83, 4.68) | 1.00 (reference) |

1.77 (0.80, 3.93) | 4.71 (3.81, 5.83) | <0.001 |

| 1/B2M | 24.36 (14.30, 41.49) | 4.16 (2.46, 7.03) | 1.00 (reference) |

2.02 (0.91, 4.48) | 11.35 (8.63, 14.92) | 0.6 |

| 3-Marker Composite^ |

32.35 (19.65, 53.25) | 3.10 (1.90, 5.05) | 1.00 (reference) |

3.02 (1.23, 7.42) | 15.37 (11.58, 20.39) | 0.05 |

| Adjusted for covariatesa + first eGFRcr value | ||||||

| eGFRcr | 19.96 (11.73, 33.96) | 2.61 (1.50, 4.55) | 1.00 (reference) |

0.59 (0.17, 2.04) | 10.77 (8.14, 14.24) | -- |

| eGFRcys | 16.67 (10.27, 27.06) | 3.00 (1.88, 4.81) | 1.00 (reference) |

1.31 (0.59, 2.93) | 4.82 (3.87, 5.99) | <0.001 |

| 1/B2M | 22.53 (13.20, 38.43) | 4.03 (2.38, 6.81) | 1.00 (reference) |

1.90 (0.86, 4.20) | 10.69 (8.09, 14.11) | 0.9 |

| 3-Marker Composite^ |

31.97 (19.40, 52.70) | 3.16 (1.94, 5.16) | 1.00 (reference) |

1.77 (0.71, 4.44) | 14.76 (11.07, 19.69) | 0.03 |

Note: N=9,703.Values are given as adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

Adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive medication use, diabetes status, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, history of coronary heart disease, current cigarette smoking status

Continuous percent change was modelled using Cox proportional hazard regression with linear spline terms with one knot at 0%. Hazard ratios express ESRD risk per 30% decline in the filtration marker (i.e. negative percent change).

P-value corresponds to the test of difference in the coefficient for decline in an individual filtration marker or 3-marker composite and ESRD risk compared to the coefficient for decline in eGFRcr and ESRD risk (reference group indicated by the dash mark) using seemingly unrelated regression. Poisson models were used for the seemingly unrelated regression analysis, using linear spline terms with one knot at 0% to represent continuous decline in filtration markers.

3- Marker Composite: mean of percent change in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M

B2M, β2-Microglobulin; CI eGFRcr, creatinine-based estimated glomerular filtration rate; eGFRcys, cystatin C–based estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease

For the three-marker composite, calculated as the mean of change in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M, those with greater than 30% decline had a 32-fold increased risk of ESRD than those with a stable concentration of the mean of three filtration markers after adjusting for covariates and first measurement of eGFRcr (HR, 31.97; 95% CI, 19.40-52.70; Table 3). Estimates of ESRD risk among participants with 10%-30% decline in the three-marker composite were similar in magnitude to estimates for individual filtration markers. Percent change in the three-marker composite was more strongly associated with ESRD risk than eGFRcr decline in models accounting for covariates and first measurement of eGFRcr (p=0.03).

Patterns were similar when percent change in filtration markers was modelled continuously (Table 3). Results were not substantially different after adjustment for first measurement of eGFRcr (Table 3) or adjustment for first measurement of the respective filtration marker (Table S3). After adjusting for albuminuria at a different time point, the results were attenuated but similar to the main results (Table S4).

ESRD risk estimates associated with decline in the two-marker combination of eGFRcr and eGFRcys (HR for greater than 30% decline, 20.12; 95% CI, 12.60-32.13) and the two-marker combination eGFRcys and 1/B2M (HR for greater than 30% decline, 26.85; 95% CI, 15.67-46.04) were not significantly different than that for decline in eGFRcr (Table S5). Compared to the individual filtration markers, ESRD risk estimates were stronger for decline in the two-marker combination of eGFRcr and 1/B2M (HR for greater than 30% decline, 37.82; 95% CI, 22.13-64.61; p for all comparisons to individual filtration markers <0.001).

A risk score determined by the number of filtration markers that declined greater than 30% (range, 0-3) was strongly, monotonically associated with ESRD risk. Compared to having no markers that declined greater than 30%, the risk of ESRD for one, two, and all three markers that declined greater than 30% was 3.67 (95% CI, 2.26-5.96), 12.83 (95% CI, 7.58-21.72), and 36.23 (95% CI, 23.20-56.59), respectively, after adjusting for demographics, kidney disease risk factors, and first measurement of eGFRcr.

The estimates of association between percent change in filtration markers and kidney failure were weaker but demonstrated similar patterns as the results for ESRD (Table S6). Competing risk analyses were conducted to account for the competing risk of death before ESRD, and the results were slightly attenuated but consistent with the main findings.

DISCUSSION

In this community-based population, progression of CKD assessed using greater than 30% percent change in novel filtration markers (eGFRcys and 1/B2M) over a six-year period was a strong, independent risk factor for ESRD during 15 years of follow-up, similar in magnitude to decline in eGFRcr. Compared to eGFRcr decline, risk of ESRD was substantially higher when percent change in eGFRcr, eGFRcys, and 1/B2M were combined together. Substantial (greater than 30%) decline in novel filtration markers may be less common, but appears to be more specific for ESRD than equivalent changes in eGFRcr.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine change in novel filtration markers as a surrogate for ESRD risk. Two previous studies have investigated the relationship between change in eGFRcr and ESRD.31,32 In the Alberta Kidney Disease Network study of 598,397 adults with a median follow-up of 3.5 years, study participants with a “certain drop” in kidney function, defined as 25% or greater decline in eGFRcr over a one-year period, had a 5-fold increased risk of ESRD after adjusting for first measurement of eGFRcr, age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, socioeconomic status, kidney function, proteinuria, and history of comorbidities (HR, 5.11; 95% CI, 4.56-5.71).31 Participants with an “uncertain drop” in kidney function, corresponding to less than 25% change in eGFRcr, had 2.13-fold (95% CI, 1.84-2.47) increased risk of ESRD compared to those with stable kidney function. The Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium conducted a large meta-analysis of 1.5 million participants with 12,344 ESRD events during a mean follow-up of 3.1 years within 22 cohorts. In a continuous analysis with 0% change as the reference, 30% decline in eGFRcr was associated with 6.7-fold (95% CI, 3.9-11.5) increased risk of ESRD among those with baseline eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 after adjusting for first measurement of eGFR and potential confounders.32

The ESRD risk estimates associated with change in eGFRcr in the present study were considerably stronger than those previously reported. The use of a higher cut-point for CKD progression (greater than 30% eGFRcr decline in the present study versus 25% or greater eGFRcr decline in the Alberta Kidney Disease Network study) may explain the higher estimates of ESRD risk in the present study. However, the same threshold for CKD progression was used in the Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium as in the present study, but ESRD risk estimates in the consortium were also lower than in the present study, and similar in magnitude to the Alberta study. The longer time period between measurements of creatinine (six years in the present study versus one year in the Alberta study and one to three years in the consortium) and longer follow-up time (15 years in the present study versus 3.5 years in the Alberta study and 3.1 years in the consortium) may allow for more reliable estimates of kidney disease progression and ESRD risk. Lastly, the Canadian registry consisted of clinic-based patients with two measurements of serum creatinine in a one-year period, which is a more selective and perhaps a higher risk population than the present community-based study population.

Among those with 10% or greater increase in eGFRcr in the present analysis, the median of the initial eGFRcr measurements was lower than that for other categories of eGFRcr change. Regression towards the mean may explain this increase in the lowest initial eGFRcr measurements towards the average population value at the subsequent measurement.33 Another possibility is that the rise in eGFRcr may be due to the return of kidney function following an episode of acute kidney injury. However, we expect that the occurrence of acute kidney injury would have minimal influence on this analysis due to the assessment of creatinine at planned study visits in this community-based population, rather than a nephrology clinic-based study. A 10% or greater increase in eGFRcr was not significantly associated with ESRD risk in the present study, which is consistent with results from analyses adjusting for covariates and first measurement of eGFRcr in previous studies.31,32

An important limitation of this study is the potential for selection bias due to non-random loss to follow-up. Defining ESRD case status based on the USRDS registry, instead of a study visit-based definition, reduced the likelihood of this selection bias influencing these results. Participants with missing data for first or last measurement of filtration markers, precluding the calculation of percent change, were excluded from the analysis. Participants with kidney disease may be less likely to attend study visits than healthier participants. As such, exclusion due to missing study visit data may result in an underestimation of the strength of the association between change in filtration markers and risk of ESRD, and reduced the precision of the risk estimate. Another limitation is the lack of baseline measurement of urine albumin-creatinine ratio, which is a strong risk factor for ESRD.34 However, in a sensitivity analysis adjusting for albuminuria at the second time point, the associations between percent change in filtration markers and ESRD risk were attenuated but similar to the overall results. Values of filtration markers may be subject to measurement error due to differences in laboratory methods at the two time points. However, an extensive calibration study among 200 ARIC participants was conducted to quantify and correct for this source of error across all study visits over 25 years of follow-up.27 Random error or bias in the assays, if still present after calibration, would be expected to underestimate the association between change in filtration markers and ESRD risk. Although measured GFR was not available, CKD-EPI eGFR is well-established as an approximation of measured GFR particularly in populations with higher levels of kidney function, such as in the ARIC Study.28 It is possible that some participants were misclassified, (eg, those with lower creatinine generation due to sarcopenia but with actual decline in true GFR). In this scenario, those with declining kidney function would instead be classified as having stable eGFRcr (the reference group) and this would result in an underestimate of the true risk of ESRD. Our finding of the strong association between multiple markers and ESRD should be replicated in other cohorts, particularly CKD populations and those with higher proportions of moderately and severely increased albuminuria.

Strengths of this study include the use of a large, well-characterized, prospective cohort. Furthermore, long-term follow-up was available for the ascertainment of incident ESRD through linkage with the USRDS registry. In addition, we measured and adjusted for many important kidney disease risk factors, including first measurement of eGFRcr as well as the other filtration markers. The ARIC Study is representative of community-dwelling, middle- and older-aged adults (aged 53-75 years at the beginning of the risk period) with a wide range of kidney function.

In conclusion, CKD progression assessed using mean change in multiple filtration markers is a strong risk factor for ESRD risk, similar to or greater than that for any one filtration marker. Measuring mean change in novel filtration markers (eGFRcys and 1/B2M) in addition to creatinine may provide a stronger surrogate for ESRD than change in eGFRcr alone in epidemiologic research, clinical trials, and clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Support: The ARC Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C).

Additional support was provided by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R01 DK076770 (Principal Investigator: B. Astor/L. Kao) and R01 DK089174 (Principal Investigator: E. Selvin). Dr Rebholz is supported in part by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute grant T32 HL007024. Dr Coresh is partially supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant U01 DK085689 (Chronic Kidney Disease Biomarkers Consortium).

Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Reagents for the β2-microglobulin assays in the ARIC visit 2 samples were donated by Roche Diagnostics. Reagents for the cystatin C and β2-microglobulin assays in the ARIC visit 4 samples were donated by Siemens.

The study sponsors did not have a role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Contributions: Research idea and study design: JC; data acquisition: JC, ES; data analysis/interpretation: CMR, MEG, KM, ES, JC; statistical analysis: CMR; supervision or mentorship: JC. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. JC takes responsibility that this study has been reported honestly, accurately, and transparently; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Table S1: Demographic characteristics and risk factors assessed at baseline, by percent change in eGFRcys.

Table S2: Demographic characteristics and risk factors assessed at baseline, by percent change in 1/B2M.

Table S3: HRs for ESRD, by percent change in filtration markers, adjusted for covariates and first measurement of respective filtration marker.

Table S4: HRs for ESRD, by percent change in filtration markers, adjusted for covariates, first eGFR measurement, and albuminuria.

Table S5: Adjusted HRs for ESRD, by mean percent change in combinations of 2 filtration markers.

Table S6: HRs for kidney failure, by percent change in filtration markers.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this article (doi:_______) is available at www.ajkd.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Bain RP, Rohde RD, The Collaborative Study Group The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakris GL, Whelton P, Weir M, Mimran A, Keane W, Schiffrin E, Evaluation of Clinical Trial Endpoints in Chronic Renal Disease Study Group The future of clinical trials in chronic renal disease: outcome of an NIH/FDA/Physician Specialist Conference. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40(8):815–825. doi: 10.1177/00912700022009549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosansky SJ, Glassock RJ. Is a decline in estimated GFR an appropriate surrogate end point for renoprotection drug trials? Kidney Int. 2014;85(4):723–727. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens LA, Greene T, Levey AS. Surrogate end points for clinical trials of kidney disease progression. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(4):874–884. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coresh J, Matsushita K, Sang Y, et al. GFR decline as an alternative endpoint for kidney failure - meta-analysis of CKD Prognosis Consortium cohorts: A report from an NKF FDA workshop [Abstract] J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:12A. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inker LA, Heerspink HJ, Mondal H, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. GFR decline as an endpoint for clinical trials in CKD - a meta-analysis of treatment effects from randomized trials: report of an NKF-FDA workshop. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:12A. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(23):2473–2483. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):20–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dharnidharka VR, Kwon C, Stevens G. Serum cystatin C is superior to serum creatinine as a marker of kidney function: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(2):221–226. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schardijn GH, Statius van Eps LW. Beta 2-microglobulin: its significance in the evaluation of renal function. Kidney Int. 1987;32(5):635–641. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grubb AO. Cystatin C--properties and use as diagnostic marker. Adv Clin Chem. 2000;35:63–99. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2423(01)35015-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. Changes in dietary protein intake has no effect on serum cystatin C levels independent of the glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int. 2011;79(4):471–477. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxmann AC, Ahmed MS, Marques NC, et al. Influence of muscle mass and physical activity on serum and urinary creatinine and serum cystatin C. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):348–354. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02870707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight EL, Verhave JC, Spiegelman D, et al. Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int. 2004;65(4):1416–1421. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009;75(6):652–660. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Astor BC, Shafi T, Hoogeveen RC, et al. Novel markers of kidney function as predictors of ESRD, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in the general population. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(5):653–662. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juraschek SP, Coresh J, Inker LA, et al. Comparison of serum concentrations of beta-trace protein, beta2-microglobulin, cystatin C, and creatinine in the US population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(4):584–592. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08700812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanga Z, Nock S, Medina-Escobar P, Nydegger UE, Risch M, Risch L. Factors other than the glomerular filtration rate that determine the serum beta-2-microglobulin level. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhavsar NA, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, et al. Comparison of measured GFR, serum creatinine, cystatin C, and beta-trace protein to predict ESRD in African Americans with hypertensive CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):886–893. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spanaus KS, Kollerits B, Ritz E, et al. Serum creatinine, cystatin C, and beta-trace protein in diagnostic staging and predicting progression of primary nondiabetic chronic kidney disease. Clin Chem. 2010;56(5):740–749. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.138826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon V, Shlipak MG, Wang X, et al. Cystatin C as a risk factor for outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(1):19–27. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peralta CA, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, et al. Cystatin C identifies chronic kidney disease patients at higher risk for complications. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(1):147–155. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Judd S, et al. Detection of chronic kidney disease with creatinine, cystatin C, and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and association with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1545–1552. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The ARIC investigators The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28(6):1379–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siedel J, Hagele EO, Ziegenhorn J, Wahlefeld AW. Reagent for the enzymatic determination of serum total cholesterol with improved lipolytic efficiency. Clin Chem. 1983;29(6):1075–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parrinello CM, Grams ME, Couper D, et al. Calibration of analytes over twenty-five years in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study: The impact of calibration on chronic kidney disease prevalence and incidence. Clin Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.238873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turin TC, Coresh J, Tonelli M, et al. Short-term change in kidney function and risk of end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(10):3835–3843. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, et al. Decline in Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate and Subsequent Risk of End-Stage Renal Disease and Mortality. JAMA. 2014 Jun 25;311(24):2518–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis CE. The effect of regression to the mean in epidemiologic and clinical studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(5):493–498. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.