Abstract

Mutations in the human progranulin gene resulting in protein haploinsufficiency cause frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 inclusions. Although progress has been made in understanding the normal functions of progranulin and TDP-43, the molecular interactions between these proteins remain unclear. Progranulin is proteolytically processed into granulins, but the role of granulins in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease is unknown. We used a Caenorhabditis elegans model of neuronal TDP-43 proteinopathy to specifically interrogate the contribution of granulins to the neurodegenerative process. Complete loss of the progranulin gene did not worsen TDP-43 toxicity, whereas progranulin heterozygosity did. Interestingly, expression of individual granulins alone had little effect on behavior. In contrast, when granulins were coexpressed with TDP-43, they exacerbated its toxicity in a variety of behaviors including motor coordination. These same granulins increased TDP-43 levels via a post-translational mechanism. We further found that in human neurodegenerative disease subjects, granulin fragments accumulated specifically in diseased regions of brain. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of a toxic role for granulin fragments in a neurodegenerative disease model. These studies suggest that presence of cleaved granulins, rather than or in addition to loss of full-length progranulin, may contribute to disease in TDP-43 proteinopathies.

Keywords: C. elegans, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, granulin, neurodegenerative disease, progranulin, TDP-43

Introduction

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is the second most common cause of dementia in individuals under 65 years of age and is characterized by progressive changes in behavior, personality, and language (Neary et al., 1998). FTLD oftentimes presents with motor neuron disease (or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; ALS). Once thought to be unrelated disorders, FTLD and ALS are now understood to lie at two ends of the same disease spectrum (Murphy et al., 2007). This belief is supported by the identification of TDP-43 inclusions in large sets of both FTLD and ALS cases (Neumann et al., 2006; Mackenzie and Rademakers, 2007).

TDP-43 inclusions are found in individuals with familial forms of FTLD due to loss of function mutations in the progranulin gene (PGRN; Neumann et al., 2007). Progranulin is a highly conserved, secreted glycoprotein with multiple functions including regulation of inflammation, stress response, and programmed cell death (Cenik et al., 2012; Petkau and Leavitt, 2014). The holoprotein can be cleaved by proteolytic enzymes into individual granulin peptides, whose function seem to oppose those of progranulin, at least with respect to wound healing (Zhu et al., 2002). Progranulin haploinsufficiency leads to less than half the expected amount of circulating protein (Ghidoni et al., 2008; Finch et al., 2009; Sleegers et al., 2009), possibly due to abundant cleavage of the deficient holoprotein into granulin fragments. Importantly, homozygous loss-of-function mutations in progranulin do not cause FTLD with TDP-43 inclusions (FTLD-TDP), but rather are associated with neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (NCL), a juvenile onset lysosomal storage disease with seizures, ataxia, and blindness (Smith et al., 2012). As homozygous loss of PGRN is linked to NCL and heterozygous loss of the gene causes FTLD-TDP, it appears that absence and deficiency of progranulin lead to distinct clinicopathological states. Granulins are produced in progranulin haploinsufficient but not null states, suggesting that the presence of granulin cleavage fragments is a critical factor in modulating disease phenotype.

We wondered whether granulins could directly contribute to TDP-43 toxicity and disease pathogenesis. Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila, mouse, and other animal models of TDP-43 proteinopathy have shown that expression of either wild-type or mutant forms of human TDP-43 promote neuronal dysfunction, behavioral deficits, and neurodegeneration (Wegorzewska et al., 2009; Ash et al., 2010; Hanson et al., 2010; Kabashi et al., 2010; Li et al., 2010; Liachko et al., 2010; Stallings et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2010; Igaz et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011; Vaccaro et al., 2012). In this study, we examined the role of granulins in TDP-43 toxicity using a C. elegans model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Complete loss of the progranulin gene had no effect on TDP-43 toxicity. In contrast, we found that pgrn-1 mutant animals expressing TDP-43 in the presence of specific granulins exhibited behavioral impairments significantly greater than animals expressing either TDP-43 or granulin alone. The degree of impairment suggests a synergistic effect between these molecules. The effect was circuit specific and associated with higher levels of TDP-43. These data implicate granulins as potentially playing a pathogenic role in FTLD-TDP.

Materials and Methods

Strains.

C. elegans were cultured at 20°C according to standard procedures. Strain descriptions are at www.wormbase.org. The N2E control strain was used as the wild-type strain. The pgrn-1(tm985) strain has a 347 bp deletion in the pgrn-1 gene resulting in a null allele (Kao et al., 2011). All animals assayed were hermaphrodites. The following C. elegans strains were used in this study: CF3050 pgrn-1(tm985) I; CF3577 N2; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP], Line 1; CF3578 N2; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP], Line 2; CF3588 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP], Line 1; CF3589 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP], Line 2; AWK33 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocIs1[Ppgrn-1+TMdomain::granulin1::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Punc-122::GFP]; AWK88 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP]; rocIs1[Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin1::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Punc-122::GFP]; AWK43 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx14[Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin2::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Pmyo-2::GFP]; AWK134 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP]; rocEx14[Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin2::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry]; AWK106 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocIs7[Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin3::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Pmyo-2::GFP]; AWK137 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP]; rocIs7[Ppgrn-1+TMdomain::granulin3::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry]; AWK307 pgrn-1(tm985) I; muIs206[Pegl-3::huTDP-43::GFP]; rocEx48[Pmyo-2::GFP]; AWK351 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx49[Pced-1::granulin1::GFP]; AWK352 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx50[Pced-1::granulin2::GFP]; AWK353 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx51[Pced-1::granulin3::GFP]; TU38 deg-1(u38) X; CF3884 pgrn-1(tm985) I; deg-1(u38) X; AWK182 pgrn-1(tm985) I; deg-1(u38) X; rocIs5 [Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin3::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Pmyo-2::GFP]; AWK354 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx20 [Paex-3::huMAPT 4R1N + Pmyo-3::RFP]; AWK355 pgrn-1(tm985) I; rocEx20 [Paex-3::huMAPT 4R1N + Pmyo-3::RFP]; rocIs7 [Ppgrn-1 + TMdomain::granulin3::FLAG::polycistronic mCherry + Pmyo-2::GFP].

Generation of transgenic C. elegans.

To generate strains expressing the individual granulins, each granulin was amplified separately from wild-type C. elegans progranulin cDNA using the following primers:

Granulin 1 (forward: 5′ GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCCACCAATGCGACGCAGAAACTGAG 3′, reverse: 5′ GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGAATGCATCTAGCTCCTTGTGGATCACAA 3′); Granulin 2 (forward: 5′ GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCGTCGTCTGCCCGGACAAGGCTAGCA 3′, reverse: 5′ GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGCTGCGAGCAAAACTGCCCGTGACA 3′); Granulin 3 (forward: 5′ GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCATTGCCTGTGGAGTTGGAAAGACG 3′, reverse: 5′ GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGCTCGCACTTTCCACCATCAACAC 3′). Each granulin was then cloned into a Gateway vector containing 0.5 kb of the pgrn-1 promoter, the N-terminal 25 aa of progranulin (which contains a secretion signal) and a C-terminal FLAG tag plus polycistronic mCherry. Constructs were microinjected into the gonads of adult pgrn-1(-) C. elegans. Stable lines were isolated and extrachromosomal arrays for granulins 1 and 3 were integrated by UV irradiation using the method of Frank et al. (2003). Integrated lines were outcrossed at least four times to our lab's pgrn-1(tm985) strain.

Behavioral assays

Thrashing assay.

Day 1 adult animals were singled to a drop of M9 and the number of thrashes was counted for 30 s. A thrashing event was scored when the head crossed the midline. Twelve animals were scored per trial. Differences between strains were calculated by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferonni correction.

Lifespan, development, and progeny assays.

Lifespan experiments were performed as described previously (Hansen et al., 2007) at 20°C. For development assays, a total of 50 synchronized eggs/strain at approximately the 100 cell stage were picked and incubated at 20°C. After 48 h, the number of animals in each stage of larval development was determined. Differences between strains were calculated by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction. Progeny assays were performed as described previously (Kao et al., 2011). At least 16 animals of each strain synchronized at the late larval stage (L4) of development were singled to 35 mm NGM plates with OP50 bacteria. Animals were transferred to a new set of plates every 12 h, and the number of progeny on each plate was scored 2 d after each transfer.

Standard and early-stage egg-laying.

Egg laying assays were performed as described previously (Trent et al., 1983; Desai and Horvitz, 1989; Schafer and Kenyon, 1995; Weinshenker et al., 1995; Sawin et al., 2000; Dempsey et al., 2005). Briefly, for each strain at least eight Day 1 adults were placed into 5 mg/ml serotonin hydrochloride or M9 alone and number of eggs laid determined. Total eggs laid were normalized to the total brood size for each strain. Strains were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. Early stage egg laying was performed as described previously (Bany et al., 2003), with modifications. Briefly, ∼30–40 synchronized Day 1 adults of each strain were placed on a lawn of OP50 at room temperature and allowed to lay eggs for 30 min. At least 100 eggs per strain were scored for number of cells using a Zeiss dissecting scope. Embryos with eight or fewer cells were scored as “early stage.” The assay was repeated twice and results analyzed with one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Pumping and defecation.

Pumping assay was performed on Day 1 adult animals as described previously (Raizen et al., 1995). For defecation studies, at least 15 Day 1 adult animals were picked to an OP50 seeded plate. After 5 min of adaptation at room temperature, number of seconds between enteric muscle contractions was determined. Results were compared using a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction.

Microscopy and tissue integrity.

Animals were mounted onto glass slides with 2% agarose pads containing 30 mm levamisole hydrochloride and imaged using a Zeiss AxioImager microscope with 5× and 63× DIC objectives. Of the 11 DA/DB motor neurons in C. elegans, the nine most posterior were scored in the neuron counting assays due to masking of DB3 and DA2 by GFP coinjection marker. Neurons were counted as whole if they displayed both an intact cell body and axon. All six VC neurons were scored in the neuron counting assays. Body length of each animal was measured using ImageJ software. Bacterial packing was assessed through blind visual scoring of images of the pharynx taken at 63× magnification. Necrotic PVC interneurons were counted at 63× magnification in 100 animals at L2, L3, L4, and Day 1 adulthood and summed and normalized to the number of animals assayed to determine the total PVC neuron death for each strain.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Mixed stage worms were collected and total RNA was isolated using TRIZOL (Invitrogen) and purified using a DNA-free kit (Ambion). RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a Nanodrop ND1000 spectrophotometer. Two micrograms of RNA were used to synthesize cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). For qRT-PCR, primers for TDP-43 and reference genes were used at a concentration of 300 nm; sequences are described in Table 1). Reference genes and corresponding primers (cdc-42, pmp-3, and Y45F10D.4) were selected based on validation performed by Hoogewijs et al. (2008). qRT-PCR was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7900HT Sequence Detection instrument using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Invitrogen). Expression levels of TDP-43 for each sample were normalized to the geometric mean of the three reference genes. Each biological replicate was assayed in triplicate, and a total of three biological replicates were performed. Relative gene expression was calculated using the Livak method with the pgrn-1;TDP-43 strain as a calibrator. Differences between strains were determined by two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction.

Table 1.

qRT-PCR primer sequences and product length

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TDP-43 (primer set 1) | gtgctcgtctccacggttac | ttctaccagccggacacctc | 98 |

| TDP-43 (primer set 2) | gacgatggtgtgactgcaaac | gcagctcatcctcagtcatgtcc | 113 |

| cdc-42 | ctgctggacaggaagattacg | ctcggacattctcgaatgaag | 111 |

| pmp-3 | gttcccgtgttcatcactcat | acaccgtcgagaagctgtaga | 115 |

| Y45F10D0.4 | gtcgcttcaaatcagttcagc | gttcttgtcaagtgatccgaca | 139 |

Antibodies and immunoblotting

C. elegans.

Animals from each strain were collected and washed in M9 buffer, sonicated in ice-cold worm extraction buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mm NaF, 0.5 mm pefabloc, Pierce c0mplete protease inhibitor, Pierce Ph0sSTOP phosphatase inhibitor) and centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C at 13000 rpm on a table top centrifuge. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant was normalized for protein, boiled in LDS buffer (Invitrogen), resolved on 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF. Antibodies used for Western blotting were the following: anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, no. F3165, dilution 1:1000) to detect FLAG-tagged granulin; anti-human TDP-43 (Abcam, no. ab57105, dilution 1:500); anti-phosphoTDP-43 (Cosmobio, 11-9, dilution 1:1000), anti-actin (Millipore, no. MAB1501R, dilution 1:5000), and goat anti-mouse (LI-COR IRDye CW800, 1:10,000 dilution). Imaging and quantification was performed on a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared System. Three biological replicates were performed for each experiments and results averaged for quantification.

Human brain tissue.

Frozen human brain tissue was obtained from the UCSF Neurodegenerative Disease Brain Bank. Subjects were chosen based on a postmortem interval <24 h (range 2.3–23.8 h; Table 6). Adjacent tissue blocks were fixed, embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned, stained for hematoxylin and eosin, and rated for astrogliosis (0–3 scale). Frozen tissue blocks were chosen for inclusion based on a level of severe (2–3+ gliosis) or absent (0–1+ gliosis) neurodegeneration in the adjacent fixed tissue block. Using these criteria, we selected the middle frontal gyrus (severe neurodegeneration) and calcarine cortex (absent neurodegeneration) to interrogate by Western blot. Tissue sections were suspended in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors, sonicated, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a novel anti-human granulin E antibody. The following epitope used to generate the anti-human granulin E rabbit polyclonal antibody: ECGEGHFCHDNQTCCR. We performed dot blots to determine cross-reactivity of our anti-granulin E antibody with other human granulins. This antibody specifically recognizes granulin E and not granulins A–D, F, G, or petite (p, paragranulin).

Table 6.

Clinical information for control, AD, and FTLD-TDP subjects

| Pathological diagnosis | Age at death | Gender | PMI | Other findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| 1 | 86 | F | 7.8 | — |

| 2 | 76 | M | 8.2 | — |

| AD | — | |||

| 1 | 63 | M | 6.0 | — |

| 2 | 62 | M | 9.9 | — |

| 3 | 72 | M | 7.9 | — |

| FTLD-TDP-A | ||||

| 1 | 64 | M | 2.3 | AGD |

| 2 | 72 | M | 23.8 | — |

| 3 | 78 | F | 9.0 | — |

The pathological diagnosis, age at death, gender, post-mortem interval (PMI), and secondary pathological findings for all subjects in Figure 8 are listed. All subjects were negative for Pgrn mutations. AGD, Argyrophilic grain disease.

Results

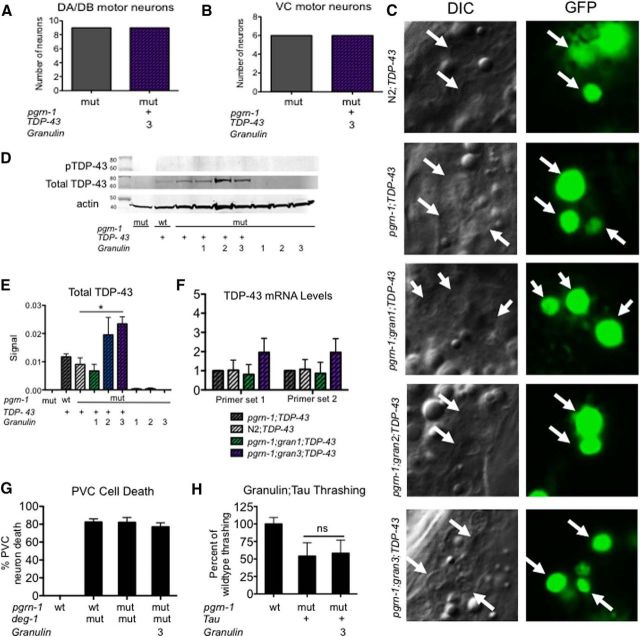

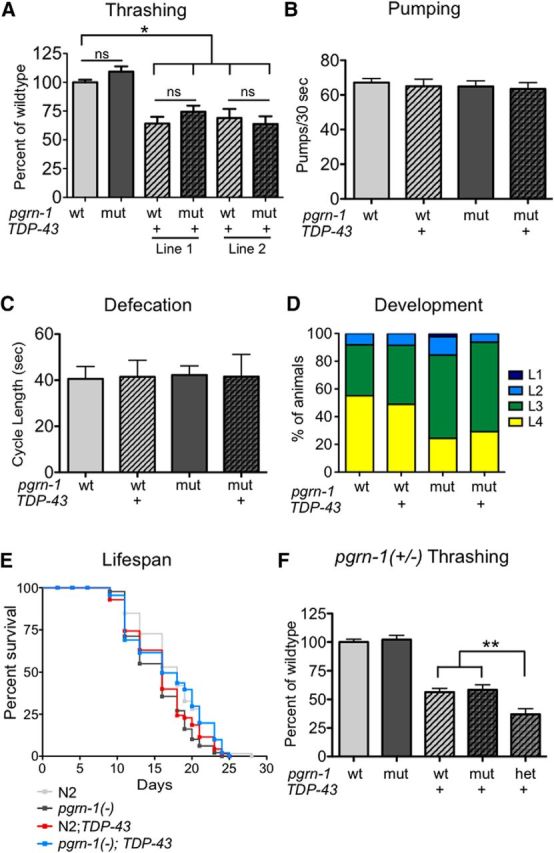

Neuronal TDP-43 impairs specific behaviors

Earlier studies have shown that expression of human TDP-43 in C. elegans neurons causes a significant decrease in motor coordination as measured by thrashing ability (Ash et al., 2010; Liachko et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011). We generated a similar model of TDP-43 proteinopathy by stably expressing human TDP-43 behind a pan-neuronal egl-3 promoter in a wild-type N2 background. Upon characterization of two independent lines of this strain, we found defects in motor coordination consistent with that seen by others (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, other stereotyped motor programs, such as pharyngeal pumping and defecation were unaffected in these animals (Fig. 1B,C). We further investigated the effect of TDP-43 on the animal's rate of larval development and lifespan. In both cases, we found that neuronal TDP-43 expression did not significantly impair these behaviors (Fig. 1D,E; Table 2). These findings suggest that certain neuronal populations, including neurons involved in the thrashing program, are more sensitive to TDP-43, whereas other circuits and processes are preserved.

Figure 1.

Progranulin gene dosage differentially affects behavior in TDP-43 animals. A, TDP-43 expression impairs motor function as measure by thrashes per 30 s. Two independent lines of animals expressing TDP-43 were tested. These lines exhibited similar results in all assays tested; therefore, data from only one is shown in subsequent figures. Data represents average of 3 trials (n = 12 per trial). B, C, TDP-43 expression did not affect pharyngeal contractions (B) or rate of defecation (C; n = 15 per trial). D, To measure development, the larval stage of each animal was scored at 48 h after the 100-cell stage. Data are graphed as percentage developing to each larval stage after 48 h (n = 50). E, Lifespan is unaffected by TDP-43 expression (Mantel–Cox test). Data shown corresponds to trial 1 of 3 in Table 2. F, pgrn-1(+/−); TDP-43 animals exhibit impaired motor coordination compared with the wild-type N2 strain (n ≥ 11). For all panels: ns, not significant; wt, wild-type; mut, mutant; het, heterozygote; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA. Error bars represent SD.

Table 2.

Loss of progranulin does not shorten lifespan in TDP-43 animals

| Strain | Trial | Mean lifespan ± SEM | Events/obs | Percentage difference from N2 | p value summary vs N2 | p value summary vs pgrn-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | 1 | 13.8 ± 0.8 | 77/90 | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-) | 14.4 ± 0.7 | 83/90 | 4.3 | ns | — | |

| N2;TDP-43 | 11.3 ± 0.7 | 79/90 | −18.1 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 15.7 ± 0.7 | 77/90 | 13.8 | ns | ns | |

| N2 | 2 | 16.2 ± 0.5 | 71/90 | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(tm985) | 14.4 ± 0.5 | 67/90 | −11.2 | * | — | |

| N2;TDP-43 | 14.9 ± 0.6 | 80/90 | −7.8 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 16.1 ± 0.7 | 56/90 | −0.9 | ns | * | |

| N2 | 3 | 14.7 ± 0.7 | 54/80 | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-) | 14.2 ± 0.7 | 50/80 | −3.4 | ns | — | |

| N2;TDP-43 | 11.6 ± 0.6 | 60/80 | −21.0 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 13.2 ± 0.8 | 40/80 | −10.2 | ns | ns |

Three independent lifespan trials were performed comparing wild-type and pgrn-1(-) strains with and without TDP-43. Average lifespans of strains were compared using the Mantel–Cox statistical test (ns, not significant;

*p < 0.01).

TDP-43 toxicity is unaffected by loss of the pgrn-1 gene but worsened by heterozygosity

Because progranulin haploinsufficiency is associated with TDP-43 pathology, we asked whether progranulin gene dosage modulated the phenotype of animals expressing TDP-43. Similar to the human protein, C. elegans progranulin is produced throughout life and is secreted from a number of tissues including a subset of head neurons and the intestine (Kao et al., 2011). We crossed a null pgrn-1(tm985) allele into our neuronal TDP-43 strains. The pgrn-1(tm985) mutant produces neither progranulin mRNA nor protein (Kao et al., 2011). As no progranulin protein is produced, by extension, granulins also are not produced in these animals.

First, we examined motor coordination. Despite the fact that loss of progranulin improves an animal's ability to successfully respond to stressful stimuli (Judy et al., 2013), complete loss of the pgrn-1 gene did not alter thrashing for better or for worse in TDP-43 animals (Fig. 1A). Pharyngeal pumping and defecation, which were unaffected by the presence of TDP-43, were also not worsened by loss of pgrn-1 (Fig. 1B,C). We next tested rate of development. Compared with controls, pgrn-1 mutants at baseline have slightly delayed development (Kao et al., 2011). Expression of TDP-43 in a pgrn-1(-) mutant background did not further delay development (Fig. 1D). Finally, we examined lifespan in pgrn-1(-); TDP-43 animals and found no significant effect of pgrn-1 loss on longevity (Fig. 1E; Table 2). Together, these data suggest that complete loss of the pgrn-1 gene, and therefore loss of both progranulin and granulins, does not exacerbate neuronal TDP-43 toxicity.

In humans, loss of two progranulin alleles causes NCL while loss of one allele leads to FTLD-TFP. Therefore, we next asked whether pgrn-1 heterozygosity impacts TDP-43 toxicity. In contrast to pgrn-1 null animals, pgrn-1(+/−);TDP-43 animals exhibited significantly impaired motor coordination compared with TDP-43 in a wild-type background (Fig. 1F). This finding suggests that partial loss of progranulin gene function impacts TDP-43 toxicity in a manner distinct from complete loss of function. It also implies that the granulin cleavage products, which are not seen in nulls but are found in heterozygotes, may play a role in this toxicity. To interrogate this possibility, next we examined the effect of individual granulins when expressed in the absence of full-length progranulin.

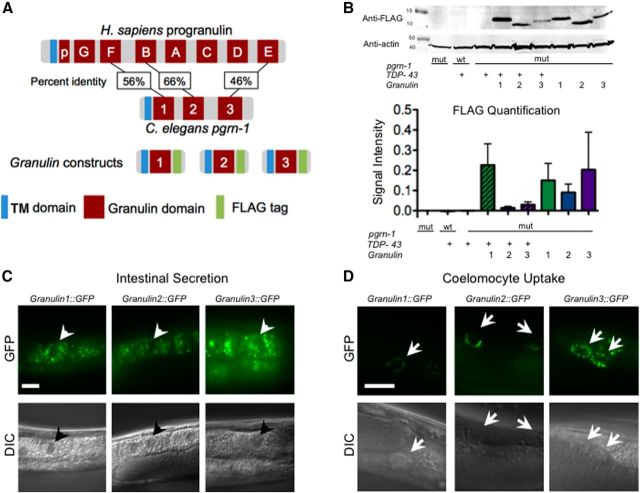

Expression of individual granulins impairs reproduction, development and growth in pgrn-1;TDP-43 animals

The C. elegans progranulin protein has three granulin domains (1, 2, and 3), compared with seven and one-half granulins in humans. Nematode granulins 1, 2, and 3 are most closely homologous to human granulins F, B, and E (Fig. 2A). The relative simplicity of the C. elegans progranulin protein allowed us to examine each of the granulins individually. Therefore, we generated transgenic strains expressing FLAG-tagged granulin 1, 2, or 3 behind the endogenous progranulin promoter in a pgrn-1(-) background (heretofore referred to as gran 1, 2, or 3 animals; Fig. 2A). These strains produce no full-length progranulin, only granulin fragments. We then crossed each pgrn-1(-); gran strain to our pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 animals to produce pgrn-1(-); TDP-43; granulin 1, 2, or 3 lines (heretofore referred to as TDP-43;gran1, TDP-43;gran2, or TDP-43;gran3 animals). We quantified granulin expression in each of these strains by Western blotting. We found no statistically significant difference in granulin expression (Fig. 2B). Similarly, we found no differences in the subcellular localization or secretion efficiency of granulin 1, 2, or 3 when fused to GFP (Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Coexpression of TDP-43 with granulin 2 or 3 synergistically delays larval development. A, Models of Homo sapiens versus C. elegans progranulin protein and FLAG-tagged granulin constructs (TM domain, transmembrane domain). B, Anti-FLAG Western blot (top) and quantification (bottom) demonstrates granulin expression in indicated strains. No significant differences are found (n = 3 biological replicates; one-way ANOVA; error bars represent SD). C, Gran1::GFP, gran2::GFP and gran3::GFP are all localized in a subset of vesicles in intestinal cells. Representative images from each line are shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. Arrowheads indicate intestinal nuclei. D, All three granulins were efficiently secreted from their cells of origin and taken up by coelomocytes, which do not produce progranulin (Kao et al., 2011). Representative images of granulin::GFP in coelomocytes is shown. Scale bar, 10 μm. Arrows indicate posterior coelomocytes.

Upon generation of the TDP-43;granulin strains, we noted an alteration in fitness of some lines. Wild-type animals produce ∼300 progeny in their lifetime. TDP-43 expression decreases the number of progeny by ∼10% (Table 3), similar to the number of progeny in pgrn-1 mutants (Kao et al., 2011). pgrn-1(-); TDP-43 animals had ∼23% decrease in progeny compared with pgrn-1(-), but addition of granulins 2 and 3 decreased this even further by 51 and 71%, respectively. Of the granulins, only granulin 1 did not alter progeny production when coexpressed with TDP-43 (Table 3).

Table 3.

TDP-43;granulin animals have reduced brood sizes

| Strain | Average progeny ± SE | Change vs pgrn-1(-) (%) | Progeny laid after Day 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | 291.7 ± 16.4 | +7.6 | 1.1 |

| N2;TDP-43 | 274.3 ± 8.2 | +1.2 | 0.2 |

| pgrn-1(-) | 271.0 ± 7.8 | — | 1.5 |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 208.1 ± 28.7 | −23.2 | 0.6 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran1 | 247.6 ± 4.8 | −8.6 | 0.6 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran1;TDP-43 | 271.8 ± 7.0 | +0.3 | 0.6 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran2 | 192.0 ± 17.3 | −29.2 | 5.8 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran2;TDP-43 | 131.8 ± 42.5 | −51.4 | 21.7 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3 | 186.5 ± 7.6 | −31.2 | 12.8 |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3;TDP-43 | 78.8 ± 12.0 | −70.9 | 8.3 |

The average number of progeny per strain was determined for strains as indicated. The percentage difference from the pgrn-1(-) strain and the percentage of progeny laid after Day 5 of adulthood are indicated.

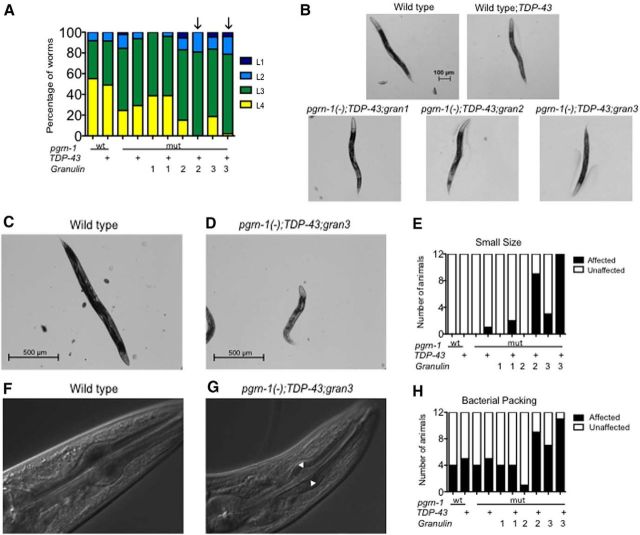

After hatching from eggs, C. elegans pass through four larval stages before reaching adulthood. We measured rate of development by quantifying the number of animals that had reached the L4 stage 48 h after the 100 cell embryo stage. We noted that the TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals were most delayed, with no animals reaching L4 stage 48 h after collection of synchronized eggs (Fig. 3A). Although TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals were developmentally delayed, once they reached the L4 stage they appeared grossly indistinguishable from wild-type (Fig. 3B), suggesting a protracted but otherwise normal developmental program.

Figure 3.

TDP-43 and granulins 2 and 3 synergistically delay development, impair growth, and increase bacterial packing. A, Granulin 2 and 3 delay development when coexpressed with TDP-43 (n = 50 per strain). B, Representative micrographs from each strain at L4 stage show that animals reach similar size. C–E, Measurement of animal size at Day 5 of adulthood. Representative images of a wild-type (C) and TDP-43;gran3 (D) worms. Animals <2 SD below the wild-type mean are score scored as small size. Results are shown in E (n = 12). F–H, Representative images of a normal pharynx from a wild-type animal (F) and abnormal bacterial packing in a TDP-43;gran3 animal (G) are shown. Scores for bacterial packing in each strain tested are shown in H (n = 12).

Despite appearing normal at the L4 stage, we found that with increasing age, the TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals appeared smaller and thinner than control animals. To quantify these differences, we measured the body length of each Day 5 adult animal and scored them as “small size” if they were two SD below the average length of the wild-type strain. Although equal in size at L4 stage, strains expressing both TDP-43 and granulin 2 or 3 failed to undergo postlarval somatic growth, and therefore by Day 5 of adulthood measured significantly smaller than control animals or those expressing TDP-43 or granulin alone (Fig. 3C–E). Some animals also displayed widening of the pharynx with packed bacteria, suggesting ineffective forward movement of food into the intestine. Thus, we blindly scored the animals for the presence of bacterial packing in the pharynx. TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals also displayed more bacterial packing in the pharynx (Fig. 3F–H). Once again, the combined effects of TDP-43 and granulin 2 or 3 suggest that they act together to promote toxicity. Of note, the TDP-43;gran 1 animals do not demonstrate decreased progeny number, delayed development, reduced size or pharyngeal bacterial packing. These data support differential roles for granulin 1 compared with granulins 2 and 3.

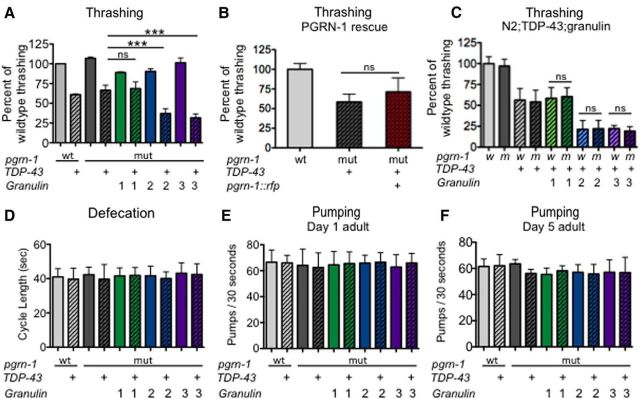

Neuronal circuits exhibit differential susceptibility to the effects of TDP-43 and granulins

We earlier showed that TDP-43 selectively affected thrashing over pharyngeal pumping and defecation (Fig. 1). These behaviors are subserved by distinct neuronal circuits and neurotransmitters. The thrashing circuit generates coordinated movement through cholinergic neurons (such as DA and DB) activating dorsal body wall muscles, whereas GABAergic neurons (such as VD) simultaneously inhibit ventral wall muscles. Gran 1, 2, and 3 animals exhibited normal thrashing compared with wild-type (Fig. 4A, solid bars). In contrast, coexpression of granulin 2 or 3 with TDP-43 caused the resulting animals to have a substantially worse motor phenotype than TDP-43 alone, again suggesting a synergistic effect between TDP-43 and granulins 2 and 3 (Fig. 4A, hatched bars; Table 4). Consistent with the reproductive, growth and developmental findings, TDP-43;gran1 animals did not display additional motor dysfunction beyond that seen with TDP-43 alone, supporting the idea that granulin 1 has a distinct functional interaction with TDP-43 compared with granulin 2 or 3.

Figure 4.

Animals expressing TDP-43 with granulin 2 or 3 exhibit circuit-specific neuronal dysfunction. A, Granulin 2 and 3 impair motor coordination when coexpressed with TDP-43. Data are averages from 3 separate trials (n = 12 per trial). TDP-43 with coinjection marker alone was tested and had no effect on thrashing compared with TDP-43 alone (data not shown). B, Coexpression of full-length progranulin (Ppgrrn-1::pgrn-1::rfp) with TDP-43 in a pgrn-1(-) background does not alter motor function (n = 12 per trial). C, Endogenous progranulin does not ameliorate motor defects caused by coexpression of granulins 2 and 3 with TDP-43 (n = 12 per trial). D, Granulins did not impair defecation in TDP-43 animals (n = 15 per trial). E, Granulins did not impair pharyngeal function in TDP-43 animals (n = 15 per trial). F, Pharyngal pumping was measured at Day 5 of adulthood as previously described. No significant differences were seen between strains. Data shown represents one trial (n = 6 per trial). For all panels: ns, not significant; wt or w, wild-type; mut or m, mutant; ***p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA. Error bars represent SD. Unless otherwise indicated, data are from Day 1 adult animals.

Table 4.

Summary of p values for thrashing assays in TDP-43 animals

| N2 | pgrn-1(-); TDP-43 | pgrn-1(-); gran1 | pgrn-1(-); gran1; TDP-43 | pgrn-1(-); gran2 | pgrn-1 (-); gran2; TDP-43 | pgrn-1 (-); gran3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(tm985) | ns | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| N2;TDP-43 | *** | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | *** | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran1 | ns | *** | — | — | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran1;TDP-43 | *** | ns | ** | — | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran2 | ns | *** | ns | *** | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran2;TDP-43 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3 | ns | *** | ns | *** | ns | *** | — |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3;TDP-43 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** |

Thrashing scores were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction (ns, not significant;

**p < 0.05,

***p < 0.0001).

To ensure that the observed motor phenotype was specific to transgenic expression of the individual granulins as opposed to the full-length progranulin protein, we assayed TDP-43 animals expressing full-length progranulin in a pgrn-1(-) background. We found that expression of full-length PGRN-1 did not worsen the thrashing ability of TDP-43 expressing animals, suggesting that the toxic phenotypes observed are specific to the individual granulins (Fig. 4B). To determine whether endogenous full-length progranulin could ameliorate the effects of the individually expressed granulins, we then tested strains with TDP-43 and granulins expressed in a wild-type background (N2;TDP-43; gran). We found that presence of endogenous progranulin does not mitigate the motor dysfunction associated with granulin and TDP-43 coexpression (Fig. 4C).

The defects in thrashing seen in TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals could be due to dysfunction in cholinergic, GABAergic or both types of neurons. To determine which neurons were adversely affected, we investigated additional behaviors. Defecation is a stereotyped motor behavior in C. elegans that is primarily subserved by GABAergic neurons (McIntire et al., 1993). Neither TDP-43 nor granulins alone impaired defecation. Similarly, coexpression of TDP-43 and granulins 1, 2, or 3 did not impair the normal defecation cycle (Fig. 4D). The relative resistance of this circuit to TDP-43;granulin supports a lack of susceptibility of GABAergic neurons to these proteins. It also indirectly suggests that in the thrashing assay, cholinergic neurons were dysfunctional.

We also investigated pharyngeal pumping. The pharyngeal nervous system consists of 20 neurons that can be divided into 14 different types (Albertson and Thomson, 1976). Of these 14 types of neurons, three appear to be required for normal pumping: M3, M4, and MC (Avery and Horvitz, 1987; Raizen and Avery, 1994; Raizen et al., 1995). When tested on Day 1, pharyngeal pumping was no different from wild-type in all strains tested, including TDP-43;gran strains (Fig. 4E). We had noted bacterial packing in the pharynges of Day 5 adult TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 strains (Fig. 3F), suggesting an inability to efficiently move bacteria from the pharynx to the intestine. This suggests an alteration in pumping in Day 5 adults, which can lead to decreased food intake and stunting of growth, as we observed in TDP-43; gran2 and TDP-43; gran3 animals (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we tested pharyngeal pumping in Day 5 adults. Once again we saw no change in the number of pumping cycles (Fig. 4F). Defects in M4, a weakly cholinergic neuron, lead to animals that still pump, but bacteria become trapped in the corpus and anterior isthmus due to inefficient isthmus peristalsis (Avery and You, 2012). These animals then fail to grow because they cannot pass food into their intestine. This is precisely the phenotype that we see in TDP-43;gran 2 and TDP-43; gran3 strains—small animals that pump at the normal rate but ineffectively. This supports pumping as another cholinergic circuit that is differentially susceptible to coexpression of TDP-43 and granulins 2 and 3.

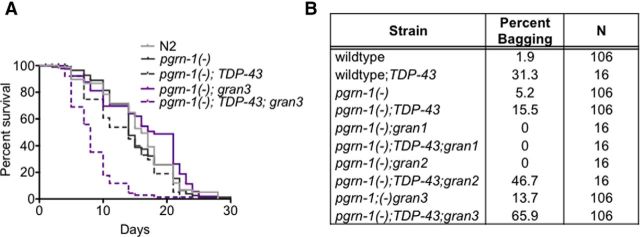

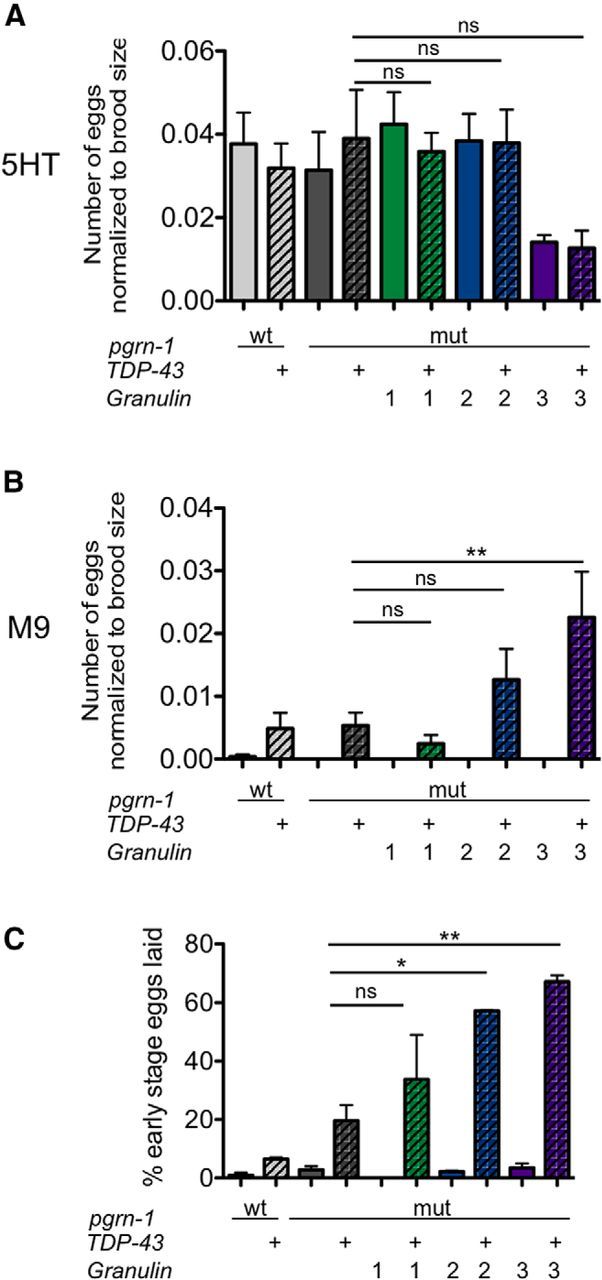

TDP-43;granulin animals exhibit decreased progeny production and extended reproductive span

To further investigate the effects of granulin and TDP-43 coexpression on C. elegans behavior, we performed lifespan assays. Like TDP-43 alone, granulin 3 expression did not significantly impair lifespan; however, animals expressing both granulin 3 and TDP-43 were short lived compared with controls (median lifespan of 8 vs 16 d; Fig. 5A; Table 5). We noted that the majority of early deaths in TDP-43;gran3 animals was due to “bagging” or internal hatching of progeny, suggesting that coordination and/or control of egg laying in these animals was impaired. To further examine this bagging phenotype, we performed progeny assays. We found that alone, gran 2 and 3 animals had slightly smaller brood sizes but no more bagging than wild-type (Table 3; Fig. 5B). TDP-43 alone seemed to provoke bagging, however coexpression of TDP-43 with granulin 2 or 3 further decreased progeny production and resulted in more animals dying from internal hatching of progeny. Interestingly, the gran 2 and 3 strains, as well as their TDP-43 expressing counterparts had prolonged reproductive spans even though their total progeny were fewer (Table 3). This suggests that granulins alone can modulate reproductive behavior, although presence of TDP-43 once again has a synergistic effect.

Figure 5.

Coexpression of TDP-43 and specific granulins reduces lifespan and alters reproductive efficiency. A, Strains expressing both TDP-43 and granulin 3 had a median lifespan of 8 d, compared with 16 d for wild-type (n = 90). Shown is trial 1 of two independent trials (Table 5). B, Percentage of animals with internally hatched progeny for each strain.

Table 5.

Lifespan of TDP-43;gran3 animals

| Strain | Trial | Mean lifespan ± SEM | Events/obs | Percentage difference compared with N2 | p value summary vs N2 | p value summary vs pgrn-1(-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | 1 | 15.1 ± 0.7 | 68/90 | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(tm985) | 15.0 ± 0.6 | 77/90 | −0.7 | ns | — | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 12.6 ± 0.7 | 68/90 | −16.6 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3 | 15.9 ± 0.9 | 57/90 | 5.3 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43;gran3 | 8.1 ± 0.4 | 71/90 | −46.4 | *** | *** | |

| N2 | 2 | 16.4 ± 0.8 | 72/90 | — | — | — |

| pgrn-1(-) | 15.0 ± 0.8 | 60/90 | −8.5 | ns | — | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43 | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 73/90 | −18.9 | ** | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);gran3 | 17.4 ± 1.0 | 39/90 | 6.1 | ns | ns | |

| pgrn-1(-);TDP-43;gran3 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 74/90 | −45.7 | *** | *** |

Two independent lifespan trials were performed on strains as indicated. Average lifespans of strains were compared using the Mantel–Cox statistical test (ns, not significant;

**p < 0.01,

***p < 0.0001).

Dysfunctional cholinergic neurons cause a constitutive egg laying defect in TDP-43;gran animals

The egg laying circuit in C. elegans has been described at the cellular and molecular level. The hermaphrodite specific neuron (HSN) promotes egg-laying through serotonin (5-HT) signaling onto the vulval muscles. Defective release of serotonin (5-HT) from HSN neurons results in internal hatching of progeny also known as an egg-laying defective (Egl) phenotype (Desai et al., 1988). To determine whether loss of HSN activity underlies the Egl phenotype we observed, we provided exogenous 5-HT in the media. If defective release of 5-HT from HSN were responsible for the bagging of TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals, we would expect this maneuver to provoke egg laying. However, exogenous 5-HT did not stimulate egg laying in TDP-43;gran 2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals (Fig. 6A), suggesting intact 5-HT signaling from HSN.

Figure 6.

Expression of TDP-43 with granulins 2 and 3 results in a constitutive egg-laying (Egl-C) phenotype. A, Animals were treated with 5 mg/ml serotonin hydrochloride (5HT) for 1 h and then eggs laid were quantified (n = 8 per strain). B, Animals were treated with M9 for 1 h and then eggs laid were quantified. Granulin; TDP-43 animals exhibited constitutive egg laying (n = 8 per strain). C, The percentage of early-stage eggs laid by Day 1 adults from each strain. Granulin; TDP-43 animals exhibited premature egg laying (data shown are the average of two trials, n ≥ 100 per trial). For all panels: ns, not significant; wt, wild-type; mut, mutant; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA. Error bars represent SEM.

During the egg laying assay, we noted that TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals spontaneously laid eggs into M9 liquid buffer and also in the absence of food (Fig. 6B), conditions in which wild-type animals will normally inhibit egg laying (Riddle et al., 1997). This hyperactive or constitutive egg laying (Egl-C) phenotype is seen when cholinergic VC neurons fail to inhibit 5-HT release from the HSN (Bany et al., 2003). Wild-type animals typically retain eggs in the gonad for a period of development to the 30–100 cell stage before release, whereas Egl-C animals lay early staged eggs (Bany et al., 2003). We quantified the number of early stage eggs, scored as eggs with eight or fewer cells, produced by our strains. We found, like other Egl-C mutants, that TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals laid substantially more early stage eggs than N2, TDP-43, or granulin animals (Fig. 6C). Thus, similar to the thrashing and pumping assays, these findings support a loss of function of cholinergic neurons.

The hyperactive Egl-C phenotype of TDP-43;gran2 and TDP-43;gran3 animals is at odds with the frequent bagging we observed in our lifespan and progeny assays. The bagging that we observed tended to occur on Day 4 or after during the reproductive span. It is possible that with age, the HSN neurons also become dysfunctional thus leading to bagging.

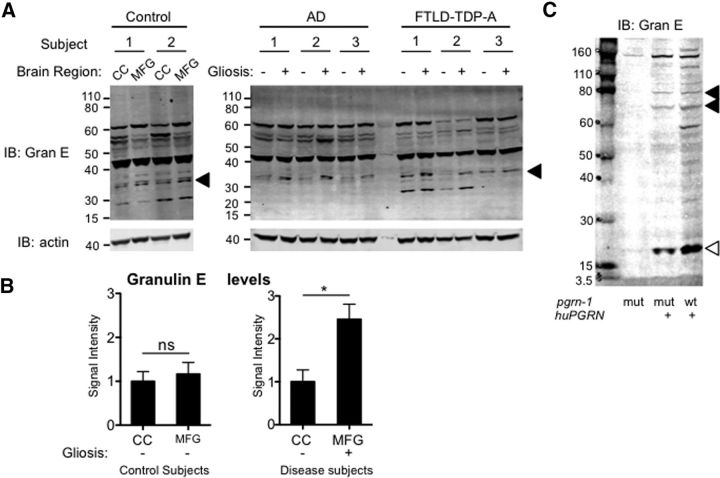

Granulins promote TDP-43 accumulation

We were interested in how coexpression of TDP-43 with granulins 2 and 3 led to the neuronal dysfunction that we observed. First, we looked for evidence of neuron loss. We used Punc-129::GFP to visualize the DA and DB motor neurons associated with locomotion and Plin-11::pes10::GFP to visualize the ventral type-C motor neurons associated with egg laying. These neurons are associated with the abnormal thrashing and egg laying behaviors we observed previously. We found no evidence of neuron loss in the different strains (Fig. 7A,B), which was also the case in other models of TDP-43 proteinopathy (Ash et al., 2010). At autopsy, individuals with TDP-43 proteinopathies exhibit neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, which are the result of abnormal nuclear clearance and resultant cytoplasmic accumulation of TDP-43 (Lee et al., 2012). Therefore, we investigated whether the subcellular localization of the TDP-43 changed with granulin expression. We observed no change in nuclear localization of TDP-43 in TDP-43;gran strains (Fig. 7C). Similarly, no change in TDP-43 S409/S410 phosphorylation could be detected in granulin strains (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Granulins 2 and 3 promote TDP-43 accumulation. A, Intact DA/DB motor neurons (cell bodies and axons) were quantified for pgrn-1(-) and TDP-43;gran 3 animals expressing the Punc-129::GFP neuronal marker. No significant differences were found (n = 10). B, VC neurons (cell bodies and axons) were counted for pgrn-1(-) and TDP-43;gran 3 animals expressing the Plin-11::GFP neuronal marker. No significant differences were found (n = 10). C, Images of TDP-43::GFP nuclear localization in Day 1 adult worms. Arrows indicate neuronal nuclei. TDP-43 was observed only in nuclei and not in neuronal cell bodies or extensions. D, Western blot against total TDP-43 and phospho-TDP-43 (S409/S410) for indicated strains. E, Quantitation of total TDP-43 from Western blots, normalized to actin loading control. Data shown represents the average of three independent trials (unpaired Mann–Whitney test, single tail, *p < 0.05; error bars represent SEM). F, TDP-43 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR using two different primer sets for TDP-43. Shown is the fold-change in expression compared with the pgrn-1;TDP-43 strain. No significant differences were observed (n = 3 independent biological replicates, one-way ANOVA, error bars represent SD). G, Granulin does not affect deg-1(d)-induced touch cell necrosis. Necrotic PVC touch receptor neurons were quantified in strains through development and the percentage of animals demonstrating necrotic cells determined (n ≥ 120, error bars indicate SEM). H, Granulin does not further impair motor control in tau transgenic strains (n = 12; ns, not significant, one-way ANOVA; error bars represent SD).

TDP-43 toxicity is dose-dependent, with relatively small increases in the protein having significantly more neuronal toxicity (Barmada et al., 2014). Therefore we wondered whether the levels of TDP-43 were altered in granulin expressing animals. Granulin 1 is robustly expressed (Fig. 2B) but did not alter TDP-43 levels. Interestingly, TDP-43 levels were higher in animals coexpressing TDP-43 with granulin 2 or 3 compared with control animals (Fig. 7D,E). The mechanism by which gran 2 and 3 increased TDP-43 could be pre- or post-translational. Therefore, we performed qRT-PCR for TDP-43 mRNA levels. We found no significant differences in TDP-43 mRNA levels, suggesting a post-translational mechanism for TDP-43 accumulation (Fig. 7F). Together, these data suggest that granulins 2 and 3 appear to exacerbate TDP-43 toxicity by promoting its accumulation via a post-translational mechanism.

Mutations in progranulin have been directly linked to FTLD but allelic variants may also influence other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's Disease (AD; Brouwers et al., 2007; Perry et al., 2013). Thus, we assessed the effect of the granulins on other C. elegans neurodegenerative disease models. deg-1(d) animals express a mutant calcium channel that leads to loss of the touch receptor cells (Chung et al., 2000). Expression of granulin in a deg-1(d) background had no effect on touch neuron survival (Fig. 7G). We also tested a C. elegans model of tauopathy. Unlike our TDP-43 model, granulin coexpression had no effect on tau toxicity. (Fig. 7H). Together, these data suggest that granulins exhibit specificity in their ability to exacerbate the injurious effects of TDP-43.

Progranulin cleavage products accumulate in human neurodegenerative disease

Little is known about progranulin cleavage in humans. Therefore, we next asked whether progranulin cleavage products are seen in human neurodegenerative disease. To do this, we assessed the levels of cleaved granulins in control subjects and individuals with AD or FTLD-TDP, the subtype of neurodegeneration found in progranulin mutation carriers. Subject characteristics are found in Table 6. As internal controls for the diseased brain regions [middle frontal gyrus (MFG), defined as a gliosis score or 2–3], we used nondiseased brain tissue [calcarine cortex (CC), gliosis score or 0–1] from the same individuals. The same regions were sampled in control subjects. To ensure that we were measuring granulins, we generated a novel anti-human granulin antibody that specifically recognized granulin E. When we used this anti-human granulin E antibody for Western blotting, we found that a ∼33 kDa band was consistently over-represented in the diseased brain regions compared with nondiseased region and this was not seen in control subjects (Fig. 8A,B). This suggests that cleavage of full-length progranulin into granulin fragments is a part of the disease process in AD and FTLD. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of progranulin cleavage from human neurodegenerative disease subjects. We also used this antibody to probe human progranulin expressed in C. elegans. It also shows that human progranulin can be processed into smaller cleaved fragments when transgenically expressed (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8.

A granulin cleavage product is over-represented in diseased brain regions from AD and FTLD patients. A, Anti-granulin E and anti-actin Western blots of postmortem brain tissue from control subjects or patients with pathological diagnosis of AD or FTLD-TDP-A. Tissue was sampled from diseased regions with high gliosis (middle frontal gyrus, MFG) and nondiseased areas with low gliosis (CC) in AD and FTLD subjects and the same areas in control individuals. A ∼33 kDa band is marked by arrowheads. See Table 6 for clinical information. B, Quantification of the ∼33 kDa fragment from control or neurodegenerative disease subjects normalized to actin. Shown is the fold-change in signal intensity in CC compared MFG (*p = 0.023, Student's t test). C, Anti-granulin E Western blot of C. elegans strains expressing human progranulin tagged with mCherry. Arrowheads indicate specific bands, open arrowhead indicates a granulin E cleavage fragment.

Discussion

In this study, our goal was to specifically interrogate the role of granulins in the pathobiology of neurodegenerative disease. We made several novel observations. First, we showed that progranulin gene dosage impacts TDP-43 toxicity. We also found that specific disease-relevant circuits were more vulnerable to the combined effects of TDP-43 and granulin. The ability of granulins to exacerbate toxicity in neurodegenerative models was specific to TDP-43 in the models that we tested. Further, we demonstrated that although granulins 1, 2 and 3 were all expressed, granulins 2 and 3 exacerbated TDP-43 toxicity while granulin 1 did not. We also showed that granulins 2 and 3 increased levels of TDP-43 via a post-translational mechanism. Finally, we showed that in diseased brain regions from patients with AD and FTLD, cleavage fragments of progranulin accumulate. Together, these data are the first demonstration of a toxic role for granulins in neurodegeneration and offer a potential mechanism, impaired clearance of TDP-43, to pursue further.

Heterozygous, loss-of-function progranulin mutations associated with FTLD lead to the deposition of TDP-43 inclusions, thus we chose a C. elegans model of neuronal TDP-43 proteinopathy for our study. We used wild-type rather than mutant forms of TDP-43 as our model for three reasons. First, wild-type TDP-43 causes a mild but reproducible behavioral phenotype compared with the severe deficits seen with mutant TDP-43 (Liachko et al., 2010). A mild phenotype would increase the likelihood of recognizing exacerbation if granulins contributed to toxicity. Second, others have shown that wild-type and mutant TDP-43 have potentially different modes of toxicity. A315T mutant TDP-43 disrupts calcium homeostasis and leads to activation of the necrotic cell death pathway, but the mechanism of wild-type TDP-43 toxicity is less clear (Aggad et al., 2014). Finally, progranulin mutations lead to disease in the setting of wild-type TDP-43 (Gass et al., 2006); therefore, wild-type TDP-43 is more clinically relevant to progranulin haploinsufficiency.

What constitutes progranulin haploinsufficiency? Several groups have shown that this condition results in decreased progranulin mRNA (Coppola et al., 2008) and circulating protein levels (Ghidoni et al., 2008; Finch et al., 2009; Sleegers et al., 2009). Because progranulin proteases presumably maintain their normal function, it is reasonable to speculate that similar absolute levels of progranulin are subject to protease digestion, regardless of starting levels. Therefore, relative levels of the cleaved granulins would be increased. This scenario could help explain why progranulin mutation carriers have less than half the expected levels of circulating progranulin, despite one normal progranulin allele. Reagents to assess granulin levels are lacking, thus direct measures of these cleavage products have not been made. Given that granulins have been shown to act in a reciprocal fashion with progranulin (Zhu et al., 2002), investigation of granulin function in neurodegenerative disease is critical to understanding both the mechanism of disease and the implications of progranulin replacement therapies.

The granulin motif is both ancient and highly conserved. Progranulin knock out mice and tissue culture studies have shown a role for progranulin in regulation of innate immunity (Park et al., 2011; Pickford et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2011; Matsubara et al., 2012), neuronal connectivity and survival (Kleinberger et al., 2010; Tapia et al., 2011; Gass et al., 2012; Ward et al., 2014), as well as response to injury and environmental toxins (Tao et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011; Almeida et al., 2012; Martens et al., 2012; Tanaka et al., 2013; Minami et al., 2014). Yet these studies either have no granulin present or lack of characterization of granulin levels. Indeed, the groups that have specifically investigated progranulin heterozygote mice show a phenotypic difference from null mice (Ahmed et al., 2010; Filiano et al., 2013). Earlier, we had leveraged the power of C. elegans genetics and behavioral analysis to show that progranulin null mutants exhibit enhanced stress response and accelerated clearance of apoptotic cells (Kao et al., 2011; Judy et al., 2013). However, in these studies, it is not clear whether it was loss of progranulin or the granulins that conferred the phenotypes. We reasoned that by expressing granulins in the absence of progranulin, we could begin to dissect the contributions of cleaved granulins. It remains to be seen whether expression of a noncleavable form of progranulin can counter the effects of the granulin fragments.

It is also notable in our study that not all of the granulins exacerbated TDP-43 toxicity. High resolution NMR suggests that of the human granulins, only A, C, and F take on a defined three-dimensional structure in solution while granulins B, D, E, G, and petite are poorly structured disulfide isomers (Tolkatchev et al., 2008). C. elegans granulin 1 is most homologous to human granulin F, which is predicted to be highly structured. Conversely, granulins 2 and 3 are most homologous to human granulins B and E, which are predicted to lack consistent structure. The different functional consequence of granulins 2 and 3 compared with granulin 1 may relate to these structural differences.

It remains to be determined how granulins 2 and 3 increase TDP-43 levels, although in this study we have shown here that it likely involves a post-translational mechanism. Phosphorylation at S409/S410 is unchanged, but other post-translational modifications remain possible. Intriguingly, in humans, progranulin is delivered to the endolysosomal system by its receptor, sortilin (Hu et al., 2010), so granulins may regulate lysosomal degradation of TDP-43. Though C. elegans does not have a direct homolog of sortilin, it does have sortilin-like receptors whose significance in this process remains to be determined. While TDP-43 toxicity is dose-dependent, increasing protein clearance by inducing autophagy can ameliorate its toxicity and is a potential site of therapeutic intervention (Barmada et al., 2014).

Nonetheless, the identification of a pathological role for granulins in the setting of TDP-43 proteinopathy has several implications. It suggests that progranulin null animals may not be complete in their modeling of FTLD, but rather be better models for the progranulin null state found in juvenile onset NCL. It also suggests that granulins may be potential drug targets. Finally, until the functions of granulins are better understood, the prospect of progranulin repletion as a therapeutic option should be approached with caution. Progranulin repletion into a proinflammatory milieu with activated proteases could lead to enhanced relative levels of granulin, which may ultimately be harmful.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the NIH R21 NS082709, Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia (CFR) and Hellman Family Foundation to AWK; NIH P50 AG19724, CFR and Tau Consortium to WWS; NIH P50 AG23501 to BLM and NIH P50 AG023501 to W.W.S. and B.L.M. We thank Greame Davis (UCSF) for providing the human TDP-43 construct, Kaveh Ashrafi and Cynthia Kenyon (UCSF) for strains, and Kaveh Ashrafi for helpful discussions. Additional strains were provided by the Mitani Laboratory at the Tokyo Women's Medical University (Tokyo, Japan) and the C. elegans Genetic Center, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Aggad D, Vérièpe J, Tauffenberger A, Parker JA. TDP-43 toxicity proceeds via calcium dysregulation and necrosis in aging Caenorhabditis elegans motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12093–12103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2495-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Z, Sheng H, Xu YF, Lin WL, Innes AE, Gass J, Yu X, Wuertzer CA, Hou H, Chiba S, Yamanouchi K, Leissring M, Petrucelli L, Nishihara M, Hutton ML, McGowan E, Dickson DW, Lewis J. Accelerated lipofuscinosis and ubiquitination in granulin knockout mice suggests a role for progranulin in successful aging. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:311–324. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertson DG, Thomson JN. The pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1976;275:299–325. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1976.0085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida S, Zhang Z, Coppola G, Mao W, Futai K, Karydas A, Geschwind MD, Tartaglia MC, Gao F, Gianni D, Sena-Esteves M, Geschwind DH, Miller BL, Farese RV, Jr, Gao FB. Induced pluripotent stem cell models of progranulin-deficient frontotemporal dementia uncover specific reversible neuronal defects. Cell Rep. 2012;2:789–798. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash PE, Zhang YJ, Roberts CM, Saldi T, Hutter H, Buratti E, Petrucelli L, Link CD. Neurotoxic effects of TDP-43 overexpression in C. elegans. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3206–3218. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, Horvitz HR. A cell that dies during wild-type C. elegans development can function as a neuron in a ced-3 mutant. Cell. 1987;51:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L, You YJ. C. elegans feeding. WormBook. 2012;2012:1–23. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.150.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bany IA, Dong MQ, Koelle MR. Genetic and cellular basis for acetylcholine inhibition of Caenorhabditis elegans egg-laying behavior. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8060–8069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-22-08060.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada SJ, Serio A, Arjun A, Bilican B, Daub A, Ando DM, Tsvetkov A, Pleiss M, Li X, Peisach D, Shaw C, Chandran S, Finkbeiner S. Autophagy induction enhances TDP43 turnover and survival in neuronal ALS models. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:677–685. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers N, Nuytemans K, van der Zee J, Gijselinck I, Engelborghs S, Theuns J, Kumar-Singh S, Pickut BA, Pals P, Dermaut B, Bogaerts V, De Pooter T, Serneels S, Van den Broeck M, Cuijt I, Mattheijssens M, Peeters K, Sciot R, Martin JJ, Cras P, et al. Alzheimer and Parkinson diagnoses in progranulin null mutation carriers in an extended founder family. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1436–1446. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.10.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenik B, Sephton CF, Kutluk Cenik B, Herz J, Yu G. Progranulin: a proteolytically processed protein at the crossroads of inflammation and neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:32298–32306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.399170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S, Gumienny TL, Hengartner MO, Driscoll M. A common set of engulfment genes mediates removal of both apoptotic and necrotic cell corpses in C. elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:931–937. doi: 10.1038/35046585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola G, Karydas A, Rademakers R, Wang Q, Baker M, Hutton M, Miller BL, Geschwind DH. Gene expression study on peripheral blood identifies progranulin mutations. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:92–96. doi: 10.1002/ana.21397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey CM, Mackenzie SM, Gargus A, Blanco G, Sze JY. Serotonin (5HT), fluoxetine, imipramine and dopamine target distinct 5HT receptor signaling to modulate Caenorhabditis elegans egg-laying behavior. Genetics. 2005;169:1425–1436. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.032540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C, Horvitz HR. Caenorhabditis elegans mutants defective in the functioning of the motor neurons responsible for egg laying. Genetics. 1989;121:703–721. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.4.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C, Garriga G, McIntire SL, Horvitz HR. A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature. 1988;336:638–646. doi: 10.1038/336638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filiano AJ, Martens LH, Young AH, Warmus BA, Zhou P, Diaz-Ramirez G, Jiao J, Zhang Z, Huang EJ, Gao FB, Farese RV, Jr, Roberson ED. Dissociation of frontotemporal dementia-related deficits and neuroinflammation in progranulin haploinsufficient mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5352–5361. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6103-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch N, Baker M, Crook R, Swanson K, Kuntz K, Surtees R, Bisceglio G, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Boeve B, Petersen RC, Dickson DW, Younkin SG, Deramecourt V, Crook J, Graff-Radford NR, Rademakers R. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain. 2009;132:583–591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Baum PD, Garriga G. HLH-14 is a C. elegans achaete-scute protein that promotes neurogenesis through asymmetric cell division. Development. 2003;130:6507–6518. doi: 10.1242/dev.00894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J, Cannon A, Mackenzie IR, Boeve B, Baker M, Adamson J, Crook R, Melquist S, Kuntz K, Petersen R, Josephs K, Pickering-Brown SM, Graff-Radford N, Uitti R, Dickson D, Wszolek Z, Gonzalez J, Beach TG, Bigio E, Johnson N, et al. Mutations in progranulin are a major cause of ubiquitin-positive frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2988–3001. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass J, Lee WC, Cook C, Finch N, Stetler C, Jansen-West K, Lewis J, Link CD, Rademakers R, Nykjaer A, Petrucelli L. Progranulin regulates neuronal outgrowth independent of sortilin. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Franzoni M, Binetti G. Low plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2008;71:1235–1239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000325058.10218.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Taubert S, Crawford D, Libina N, Lee SJ, Kenyon C. Lifespan extension by conditions that inhibit translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2007;6:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KA, Kim SH, Wassarman DA, Tibbetts RS. Ubiquilin modifies TDP-43 toxicity in a Drosophila model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11068–11072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.078527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogewijs D, Houthoofd K, Matthijssens F, Vandesompele J, Vanfleteren JR. Selection and validation of a set of reliable reference genes for quantitative sod gene expression analysis in C. elegans. BMC Mol Biol. 2008;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Padukkavidana T, Vægter CB, Brady OA, Zheng Y, Mackenzie IR, Feldman HH, Nykjaer A, Strittmatter SM. Sortilin-mediated endocytosis determines levels of the frontotemporal dementia protein, progranulin. Neuron. 2010;68:654–667. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaz LM, Kwong LK, Lee EB, Chen-Plotkin A, Swanson E, Unger T, Malunda J, Xu Y, Winton MJ, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Dysregulation of the ALS-associated gene TDP-43 leads to neuronal death and degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:726–738. doi: 10.1172/JCI44867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judy ME, Nakamura A, Huang A, Grant H, McCurdy H, Weiberth KF, Gao F, Coppola G, Kenyon C, Kao AW. A shift to organismal stress resistance in programmed cell death mutants. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E, Lin L, Tradewell ML, Dion PA, Bercier V, Bourgouin P, Rochefort D, Bel Hadj S, Durham HD, Vande Velde C, Rouleau GA, Drapeau P. Gain and loss of function of ALS-related mutations of TARDBP (TDP-43) cause motor deficits in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:671–683. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao AW, Eisenhut RJ, Herl Martens L, Nakamura A, Huang A, Bagley JA, Zhou P, de Luis A, Neukomm LJ, Cabello J, Farese RV, Jr, Kenyon C. A neurodegenerative disease mutation that accelerates the clearance of apoptotic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4441–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100650108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinberger G, Wils H, Ponsaerts P, Joris G, Timmermans JP, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S. Increased caspase activation and decreased TDP-43 solubility in progranulin knockout cortical cultures. J Neurochem. 2010;115:735–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EB, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Gains or losses: molecular mechanisms of TDP43-mediated neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:38–50. doi: 10.1038/nrn3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liachko NF, Guthrie CR, Kraemer BC. Phosphorylation promotes neurotoxicity in a Caenorhabditis elegans model of TDP-43 proteinopathy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16208–16219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2911-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ray P, Rao EJ, Shi C, Guo W, Chen X, Woodruff EA, 3rd, Fushimi K, Wu JY. A Drosophila model for TDP-43 proteinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3169–3174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913602107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie IR, Rademakers R. The molecular genetics and neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: recent developments. Neurogenetics. 2007;8:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10048-007-0102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens LH, Zhang J, Barmada SJ, Zhou P, Kamiya S, Sun B, Mins SW, Gan L, Finkbeiner S, Huang EJ, Farese RV., Jr Progranulin deficiency promotes neuroinflammation and neuron loss following toxin-induced injury. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3955–3959. doi: 10.1172/JCI63113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara T, Mita A, Minami K, Hosooka T, Kitazawa S, Takahashi K, Tamori Y, Yokoi N, Watanabe M, Matsuo E, Nishimura O, Seino S. PGRN is a key adipokine mediating high fat diet-induced insulin resistance and obesity through IL-6 in adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2012;15:38–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntire SL, Jorgensen E, Horvitz HR. Genes required for GABA function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1993;364:334–337. doi: 10.1038/364334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami SS, Min SW, Krabbe G, Wang C, Zhou Y, Asgarov R, Li Y, Martens LH, Elia LP, Ward ME, Mucke L, Farese RV, Jr, Gan L. Progranulin protects against amyloid beta deposition and toxicity in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat Med. 2014;20:1157–1164. doi: 10.1038/nm.3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Henry RG, Langmore S, Kramer JH, Miller BL, Lomen-Hoerth C. Continuum of frontal lobe impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:530–534. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, Passant U, Stuss D, Black S, Freedman M, Kertesz A, Robert PH, Albert M, Boone K, Miller BL, Cummings J, Benson DF. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann M, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Vanmassenhove B, Kretzschmar HA, Van Deerlin VM, Clark CM, Grossman M, Miller BL, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. TDP-43-positive white matter pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:177–183. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000248554.45456.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B, Buti L, Lee S, Matsuwaki T, Spooner E, Brinkmann MM, Nishihara M, Ploegh HL. Granulin is a soluble cofactor for toll-like receptor 9 signaling. Immunity. 2011;34:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DC, Lehmann M, Yokoyama JS, Karydas A, Lee JJ, Coppola G, Grinberg LT, Geschwind D, Seeley WW, Miller BL, Rosen H, Rabinovici G. Progranulin mutations as risk factors for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:774–778. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkau TL, Leavitt BR. Progranulin in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:388–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickford F, Marcus J, Camargo LM, Xiao Q, Graham D, Mo JR, Burkhardt M, Kulkarni V, Crispino J, Hering H, Hutton M. Progranulin is a chemoattractant for microglia and stimulates their endocytic activity. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DM, Avery L. Electrical activity and behavior in the pharynx of Caenorhabditis elegans. Neuron. 1994;12:483–495. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DM, Lee RY, Avery L. Interacting genes required for pharyngeal excitation by motor neuron MC in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;141:1365–1382. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR. Introduction to C. elegans. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR, editors. C. elegans II. New York: Cold Spring Harbor; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sawin ER, Ranganathan R, Horvitz HR. C. elegans locomotory rate is modulated by the environment through a dopaminergic pathway and by experience through a serotonergic pathway. Neuron. 2000;26:619–631. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81199-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer WR, Kenyon CJ. A calcium-channel homologue required for adaptation to dopamine and serotonin in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1995;375:73–78. doi: 10.1038/375073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleegers K, Brouwers N, Van Damme P, Engelborghs S, Gijselinck I, van der Zee J, Peeters K, Mattheijssens M, Cruts M, Vandenberghe R, De Deyn PP, Robberecht W, Van Broeckhoven C. Serum biomarker for progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:603–609. doi: 10.1002/ana.21621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, Damiano J, Franceschetti S, Carpenter S, Canafoglia L, Morbin M, Rossi G, Pareyson D, Mole SE, Staropoli JF, Sims KB, Lewis J, Lin WL, Dickson DW, Dahl HH, Bahlo M, Berkovic SF. Strikingly different clinicopathological phenotypes determined by progranulin-mutation dosage. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:1102–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallings NR, Puttaparthi K, Luther CM, Burns DK, Elliott JL. Progressive motor weakness in transgenic mice expressing human TDP-43. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:404–414. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y, Matsuwaki T, Yamanouchi K, Nishihara M. Increased lysosomal biogenesis in activated microglia and exacerbated neuronal damage after traumatic brain injury in progranulin-deficient mice. Neuroscience. 2013;250:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W, Lu Y, Tian QY, Zhang Y, Guo FJ, Liu GY, Syed NM, Lai Y, Lin EA, Kong L, Su J, Yin F, Ding AH, Zanin-Zhorov A, Dustin ML, Tao J, Craft J, Yin Z, Feng JQ, Abramson SB, et al. The growth factor progranulin binds to TNF receptors and is therapeutic against inflammatory arthritis in mice. Science. 2011;332:478–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1199214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao J, Ji F, Wang F, Liu B, Zhu Y. Neuroprotective effects of progranulin in ischemic mice. Brain Res. 2012;1436:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia L, Milnerwood A, Guo A, Mills F, Yoshida E, Vasuta C, Mackenzie IR, Raymond L, Cynader M, Jia W, Bamji SX. Progranulin deficiency decreases gross neural connectivity but enhances transmission at individual synapses. J Neurosci. 2011;31:11126–11132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6244-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolkatchev D, Malik S, Vinogradova A, Wang P, Chen Z, Xu P, Bennett HP, Bateman A, Ni F. Structure dissection of human progranulin identifies well-folded granulin/epithelin modules with unique functional activities. Protein Sci. 2008;17:711–724. doi: 10.1110/ps.073295308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent C, Tsuing N, Horvitz HR. Egg-laying defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1983;104:619–647. doi: 10.1093/genetics/104.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai KJ, Yang CH, Fang YH, Cho KH, Chien WL, Wang WT, Wu TW, Lin CP, Fu WM, Shen CK. Elevated expression of TDP-43 in the forebrain of mice is sufficient to cause neurological and pathological phenotypes mimicking FTLD-U. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1661–1673. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccaro A, Tauffenberger A, Aggad D, Rouleau G, Drapeau P, Parker JA. Mutant TDP-43 and FUS cause age-dependent paralysis and neurodegeneration in C. elegans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward ME, Taubes A, Chen R, Miller BL, Sephton CF, Gelfand JM, Minami S, Boscardin J, Martens LH, Seeley WW, Yu G, Herz J, Filiano AJ, Arrant AE, Roberson ED, Kraft TW, Farese RV, Jr, Green A, Gan L. Early retinal neurodegeneration and impaired Ran-mediated nuclear import of TDP-43 in progranulin-deficient FTLD. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1937–1945. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegorzewska I, Bell S, Cairns NJ, Miller TM, Baloh RH. TDP-43 mutant transgenic mice develop features of ALS and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18809–18814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker D, Garriga G, Thomas JH. Genetic and pharmacological analysis of neurotransmitters controlling egg laying in C. elegans. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6975–6985. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06975.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YF, Gendron TF, Zhang YJ, Lin WL, D'Alton S, Sheng H, Casey MC, Tong J, Knight J, Yu X, Rademakers R, Boylan K, Hutton M, McGowan E, Dickson DW, Lewis J, Petrucelli L. Wild-type human TDP-43 expression causes TDP-43 phosphorylation, mitochondrial aggregation, motor deficits, and early mortality in transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10851–10859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1630-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Xilouri M, Bruban J, Shioi J, Shao Z, Papazoglou I, Vekrellis K, Robakis NK. Extracellular progranulin protects cortical neurons from toxic insults by activating survival signaling. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:2326.e5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Mullane PC, Periz G, Wang J. TDP-43 neurotoxicity and protein aggregation modulated by heat shock factor and insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1952–1965. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Huang C, Chen H, Wang D, Landel CP, Xia PY, Bowser R, Liu YJ, Xia XG. Transgenic rat model of neurodegeneration caused by mutation in the TDP gene. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Nathan C, Jin W, Sim D, Ashcroft GS, Wahl SM, Lacomis L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Wright CD, Ding A. Conversion of proepithelin to epithelins: roles of SLPI and elastase in host defense and wound repair. Cell. 2002;111:867–878. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]