Abstract

Bulge loops are common features of RNA structures that are involved in the formation of RNA tertiary structures and are often sites for interactions with proteins and ions. Minimal thermodynamic data currently exist on the bulge size and sequence effects. Using thermal denaturation methods, thermodynamic properties of 1- to 5-nt adenine and guanine bulge loop constructs were examined in 10 mM MgCl2 or 1 M KCl. The loop parameters for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops in RNA constructs were between 3.07 and 5.31 kcal/mol in 1 M KCl buffer. In 10 mM magnesium ions, the ΔΔG° values relative to 1 M KCl were 0.47–2.06 kcal/mol more favorable for the RNA bulge loops. The loop parameters for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops in DNA constructs were between 4.54 and 5.89 kcal/mol. Only 4- and 5-nt guanine constructs showed significant change in stability for the DNA constructs in magnesium ions. A linear correlation is seen between the size of the bulge loop and its stability. New prediction models are proposed for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops in RNA and DNA in 1 M KCl. We show that a significant stabilization is seen for small bulge loops in RNA in the presence of magnesium ions. A prediction model is also proposed for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loop RNA constructs in 10 mM magnesium chloride.

Keywords: DNA bulge loops, magnesium binding to RNA, metal–RNA interactions, purine bulge loops, RNA thermodynamics

INTRODUCTION

Folding of RNA results in A-form helical regions that are interspersed by bulges and loops of various sizes. These nonhelical regions often have specific structural features that are defined by the sequence and hence, become recognition sites for biomolecules or ions (Peattie et al. 1981; Wu and Uhlenbeck 1987; Gott et al. 1991; Correll et al. 1997; Heinicke et al. 2011). A bulge loop forms when one or more nucleotides are present on one strand in a duplex region. Small bulge loops are found in most large and small RNA (Woese and Guttell 1989; Cevec et al. 2010). For small bulge loops, the unpaired nucleotides can be “flipped out” to allow a continual helical structure to form or can stack within the helix to bend the RNA (Turner 1992; Hermann and Patel 2000). Additional interactions between the bulge nucleotides and helical stems have been seen (Huthoff et al. 2004). Bending of the RNA due to adenine or uracil bulge loops has been examined using gel electrophoresis (Bhattacharyya et al. 1990), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (Gohlke et al. 1994), and transient electric birefringence (Zacharias and Hagerman 1995a,b), among other techniques. NMR has been used to study the dynamics of trinucleotide bulge loop structures (Zhang et al. 2006, 2010). X-ray interferometry studies have provided information on the ensemble of bent conformations present in trinucleotide DNA bulge loop constructs (Shi et al. 2014).

Currently, only one study exists in which thermodynamic properties of 1- to 3-nt adenine or uracil bulge loop RNA were examined (Longfellow et al. 1990). Single-nucleotide bulge loops have been studied in both RNA and DNA constructs (Zhu and Wartell 1999; Tanaka et al. 2004; Blose et al. 2007; Minetti et al. 2010). A recent study examined the thermodynamic stability of the trinucleotide bulge loops in RNA (Murray et al. 2014).

We have previously examined the thermodynamic properties of pyrimidine trinucleotide bulge loop constructs derived from the TAR RNA of HIV-1 and found that the stability of RNA constructs rich in cytosine- or uracil-nucleotides bulge loops were sequence dependent, with differences of up to 1.20 kcal/mol in 1 M KCl (Carter-O'Connell et al. 2008). An additional ∼1.95 kcal/mol gain in stability was measured for uracil-rich RNA bulge loops in 10 mM magnesium or calcium ions over 1 M KCl. In the current study, we examined the thermodynamic properties of RNA constructs containing 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops. Both adenine- and guanine-nucleotide bulge loops were studied in a 5′U–(Bulge)–U3′ helical context. We compared the thermodynamic parameters for 1- to 5-nt adenine or guanine bulge loops and measured the effect of the bulge loop size on RNA stability in 1 M KCl or 10 mM magnesium ions. An additional helical context, 5′U–(Bulge)–G3′, was also examined to model the 4-nt mixed purine and pyrimidine bulge loop constructs in RNA; these modifications were inspired by the A-rich bulge of the P5abc region of Group 1 intron from Tetrahymena thermophilia (Cate et al. 1997). The A-rich bulge of P5abc is involved in intron folding and shows several magnesium ion binding sites in the crystal structure (Cate et al. 1997; Doherty and Doudna 2001). The size and the secondary structure of this A-rich bulge is proposed to change as the RNA folds in the presence of magnesium ions (Wu and Tinoco 1998).

Bulged structures are also known to form in DNA if primer-template misalign during replication (Kunkel 1990) or during recombination when imperfect homologous strands interact. The bulged DNA is believed to play a role in frame-shift mutagenesis and in single stranded DNA viruses (Streisinger and Owen 1985). In this study, we have examined the DNA constructs with 1- to 5-nt adenine or guanine bulge loops in constructs similar to those used for RNA. This allows us to compare the thermodynamic effects of bulge nucleotides on both DNA and RNA constructs.

Here we show that the stability of purine-rich bulge constructs is influenced by the bulge size with a linear correlation seen between bulge size and stability, with the exception of the guanine trinucleotide bulge loops. Interactions with magnesium ions impart stability to all bulge loop constructs in RNA. Our data lead to new prediction models for 1- to 5-nt bulge loops in RNA and DNA.

RESULTS

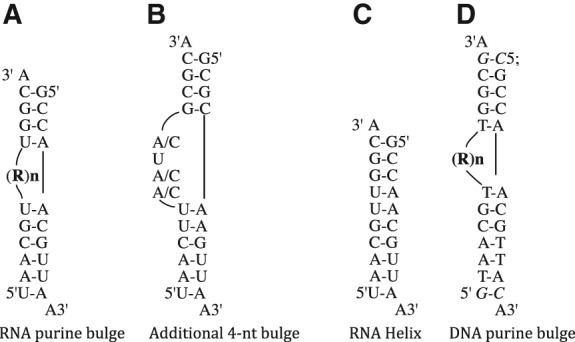

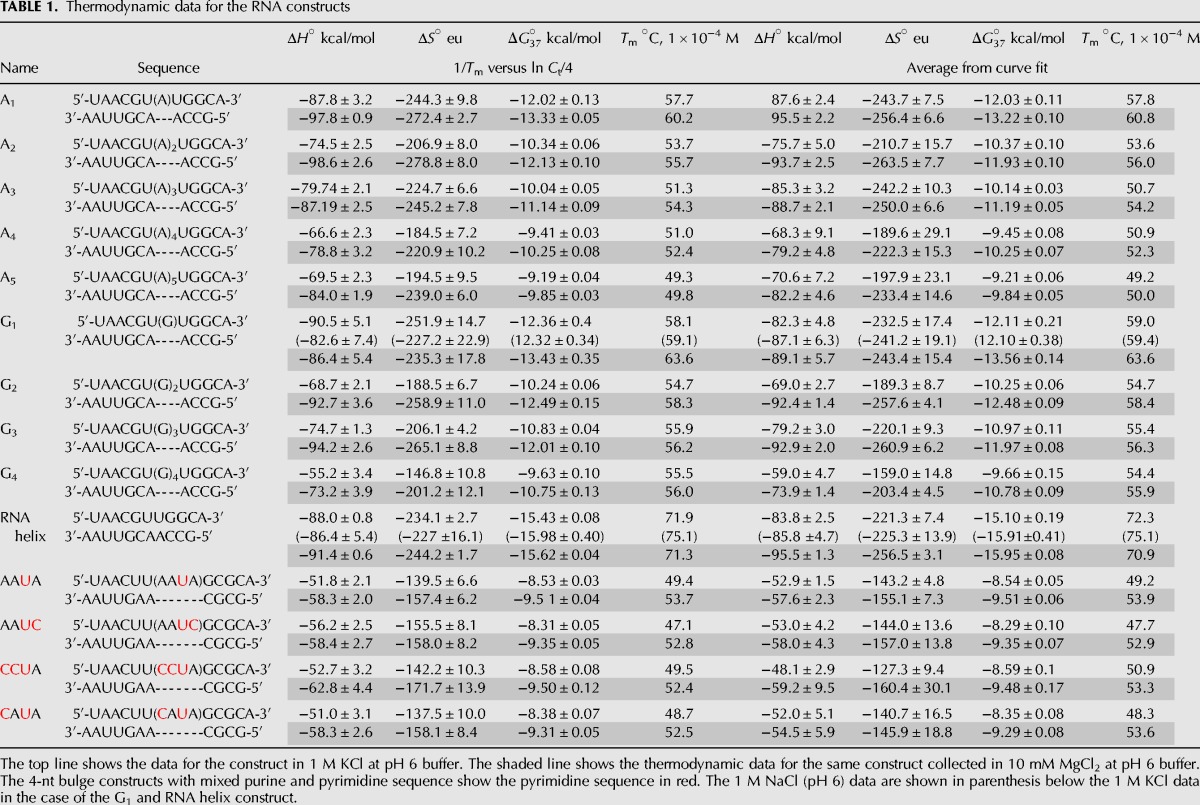

RNA constructs, 1 M KCl

The stability of 1- to 4-nt guanine bulge loop constructs ranged from −12.36 kcal/mol (1 nt) to −9.63 kcal/mol (4 nt) in 1 M KCl (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The stability of 1- to 5-nt adenine bulge loop constructs ranged from −12.02 kcal/mol (1 nt) to −9.19 kcal/mol (5 nt) in 1 M KCl (Fig. 1A; Table 1). The purine bulge loops of similar sizes showed similar stability in the helical context examined here, with the exception of the trinucleotide guanine bulge loop, which was 0.79 kcal/mol more stable than the corresponding adenine bulge loop construct (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

RNA and DNA constructs used in this study. (A) The purine bulged RNA constructs containing 1- to 5-nt (labeled RN, where R = A or G and N represents the number of nucleotides in the bulge). (B) Four-nucleotide constructs designed for examining mixed purine and pyrimidine bulge constructs. (C) The RNA helical construct without a bulge. (D) DNA constructs with RN bulge loop (where R = A or G, and N = number of nucleotides in the bulge). The additional base pairs added to the DNA constructs are shown in italics.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic data for the RNA constructs

A helix construct (with no bulge) was also examined. The stability of the helix construct in 1 M KCl at pH 6 buffer was −15.43 kcal/mol. The stability of the RNA helix construct in 1 M NaCl at pH 6 buffer was −15.98 kcal/mol (Table 1). Sodium ions have a slightly higher charge density, implying that the interactions of sodium ions with RNA should be slightly more favorable than those of potassium ions in the absence of any specific ion–RNA interactions.

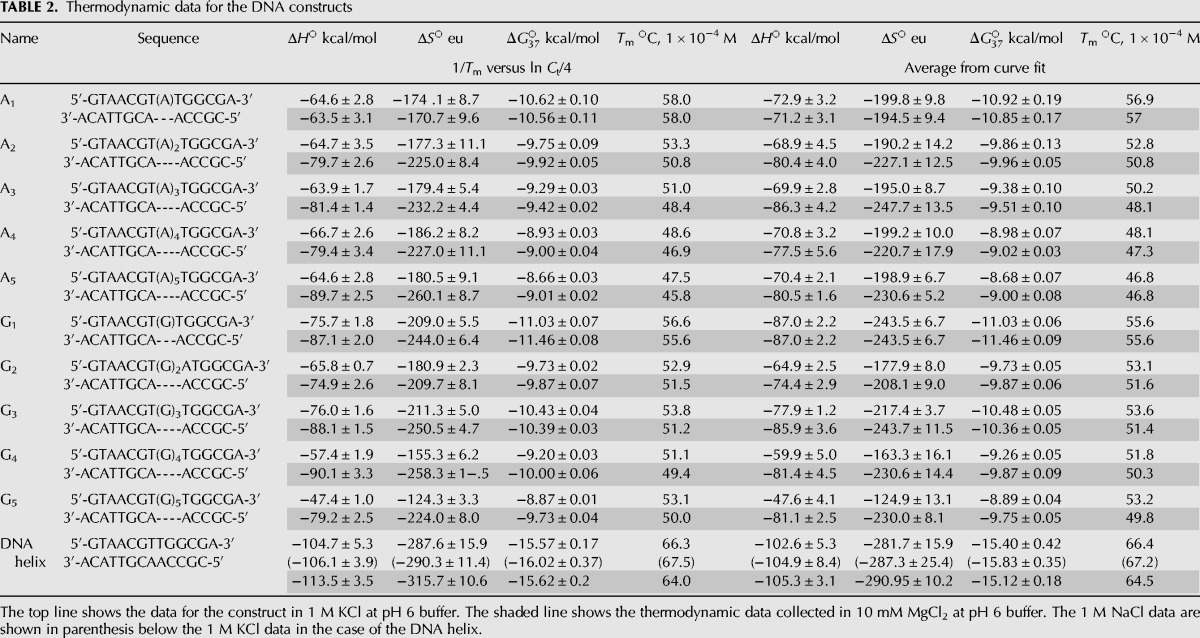

DNA constructs, 1 M KCl

One- to 5-nt adenine or guanine bulge loop DNA constructs were designed with an additional base pair in upper and lower stems to increase the stability of the DNA constructs while maintaining the same nearest-neighbor context around the bulge as in the RNA constructs (Fig. 1D). In 1 M KCl, the stability of guanine constructs ranged from −11.03 kcal/mol (1 nt) to −8.87 kcal/mol (5 nt). For adenine bulge loops, the stability changed from −10.62 kcal/mol (1-nt bulge) to −8.66 kcal/mol (5-nt bulge) (Table 2). The 3-nt guanine bulge loop shows slightly higher stability, similar to the RNA construct. The loop stabilities for DNA constructs were calculated in a manner similar to that used for RNA.

TABLE 2.

Thermodynamic data for the DNA constructs

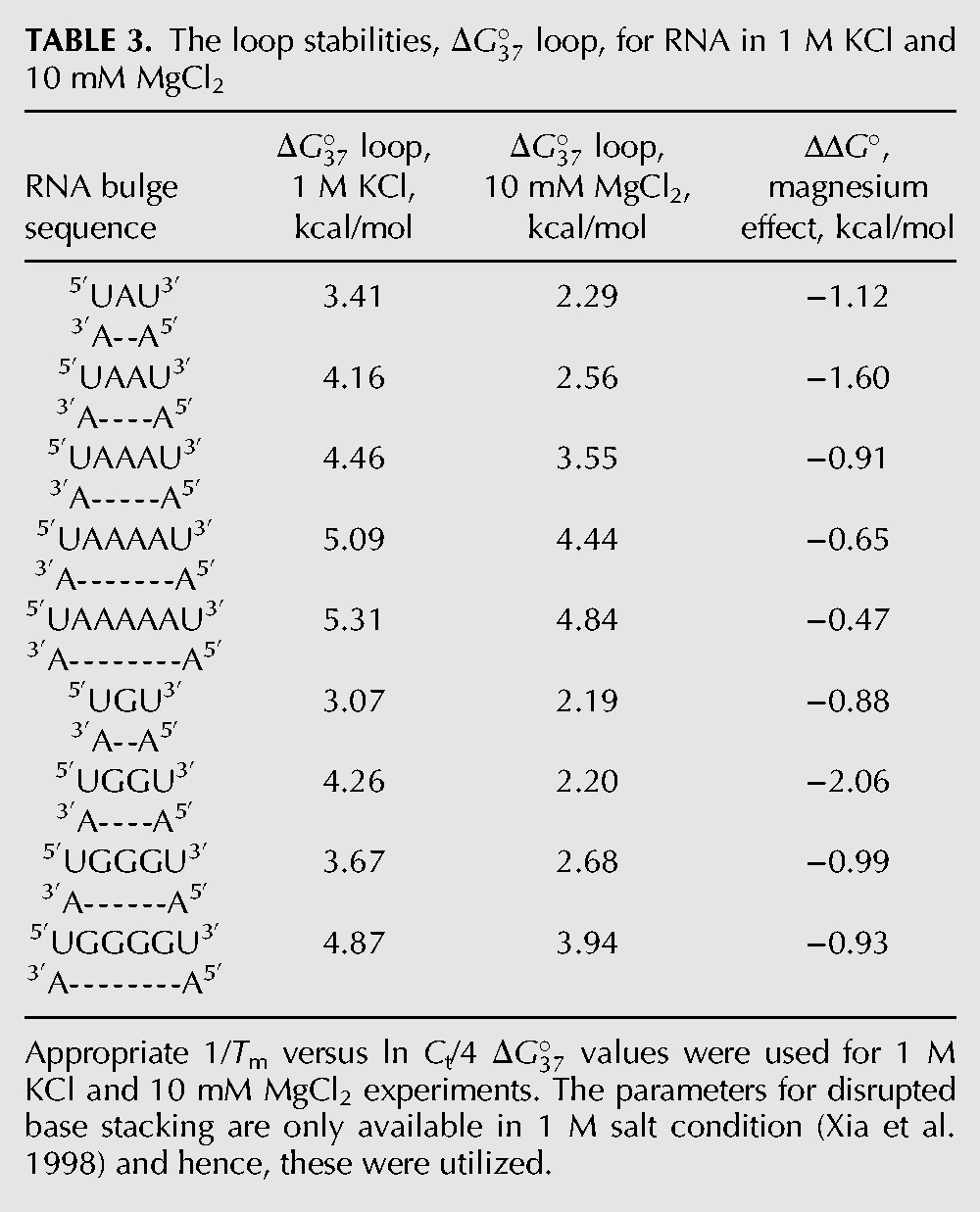

ΔG°37loop parameters, 1 M KCl

Breaking a helical structure with a bulge loop destabilizes the RNA. The changes to RNA stability upon incorporation of bulge loops are represented as loop parameter. For a single-nucleotide bulge loop, the assumption is that the helical base stacking is not disrupted (Jaeger et al. 1989; Blose et al. 2007) and hence, the calculations are performed as shown in Equation 1:

| (1) |

For 2- to 5-nt bulge loops, the calculations for the loop parameter were performed with the energetics of disrupted base stacking taken into account, as shown in Equation 2 (Jaeger et al. 1989; Xia et al. 1998):

| (2) |

The loop parameters for various size adenine and guanine bulge loops are reported in Table 3. One- to 5-nt adenine bulge loops destabilize the helical RNA between 3.41 and 5.31 kcal/mol. One- to 4-nt guanine bulge loops destabilize the helical RNA between 3.07 and 4.87 kcal/mol. The nearest-neighbor parameters from Xia et al. (1998) were utilized for disrupted base stacking in RNA.

TABLE 3.

The loop stabilities, loop, for RNA in 1 M KCl and 10 mM MgCl2

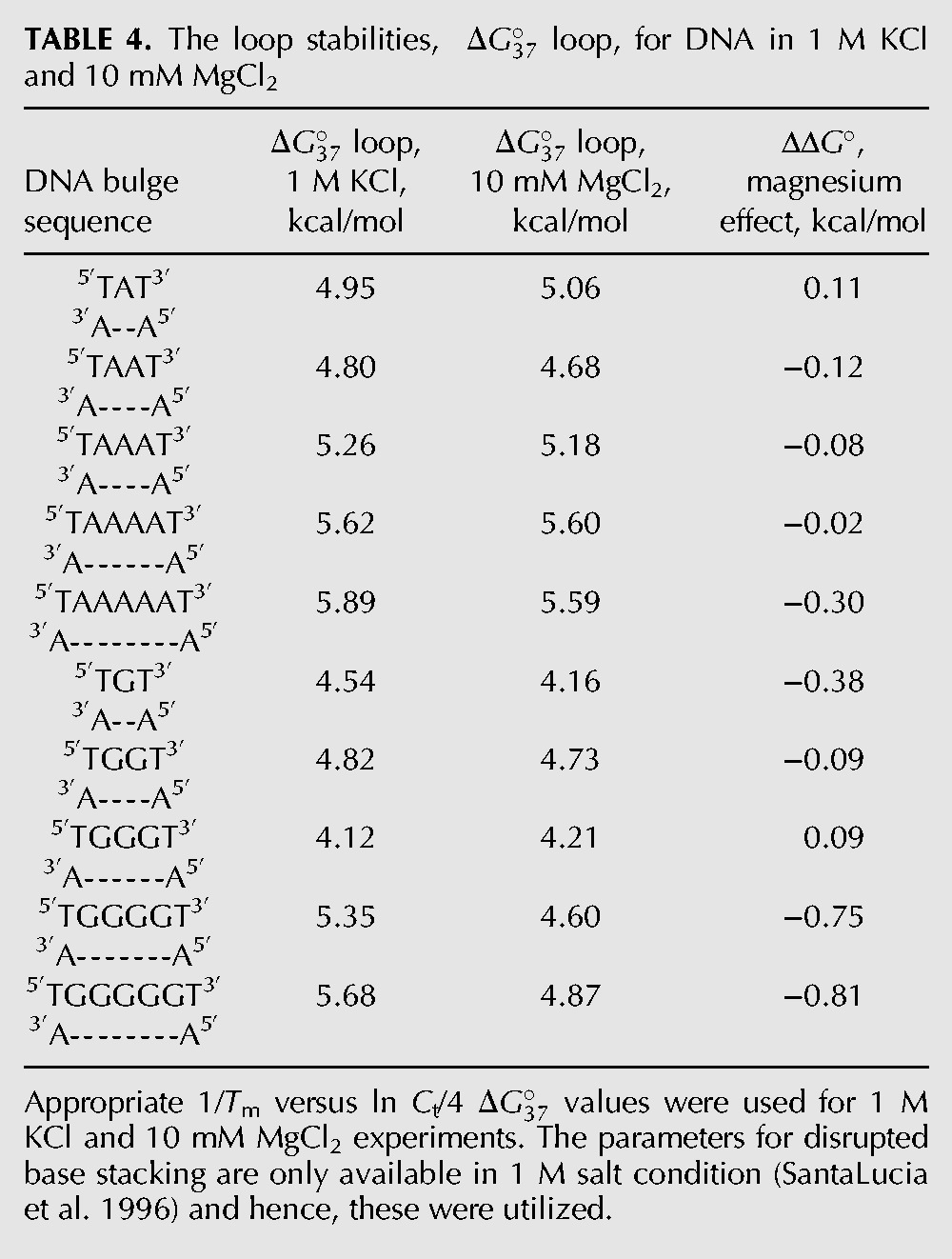

The calculations for DNA bulge loops were performed in a manner similar to those for RNA. The nearest-neighbor parameters for DNA were obtained from SantaLucia et al. (1996). Table 4 shows the loop parameters for DNA constructs. One- to 5-nt loops destabilize the helix between 4.54 and 5.89 kcal/mol.

TABLE 4.

The loop stabilities, loop, for DNA in 1 M KCl and 10 mM MgCl2

RNA constructs, 10 mM MgCl2

RNA bulge loop constructs are more stable in 10 mM magnesium chloride

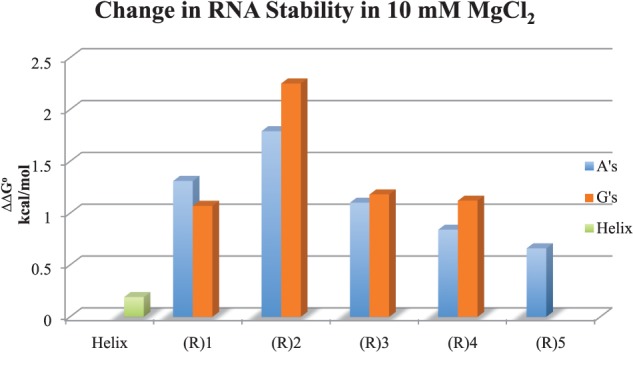

All RNA bulge loop constructs examined were additionally stabilized in the presence of 10 mM magnesium ions over 1 M KCl (Table 1; Fig. 2). The gain in stability in the presence of magnesium ions decreases the overall penalty for breaking the helical structure. Thus, 1- or 2-nt bulge loops with additional interactions with magnesium ions are energetically less expensive than would be expected based on loop parameter obtained in 1 M salt. Table 3 shows the loop parameter for 1- to 5-nt bulge loops in the presence of magnesium ions. The loop parameters were calculated as shown for 1 M KCl. The 1 M NaCl values were used for the disrupted base stacking interactions (Xia et al. 1998). The loop parameter was the most significant for the dinucleotide constructs: −1.60 kcal/mol for adenine and −2.06 kcal/mol for guanine (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

The change in stability of RNA constructs in 10 mM MgCl2 at pH 6. The ΔΔG° values (in kcal/mol) are the difference between in 1 M KCl and 10 mM MgCl2.

Mixed purine–pyrimidine 4-nt bulge loop RNA constructs are similar in stability to 4-nt all purine constructs

A slightly modified RNA construct was designed to study a mixture of purine and pyrimidine in the bulge loops (Fig. 1B). Changing one or more bulge loop purine to pyrimidine in the 4-nt bulge loop constructs had a minimal effect on in 1 M KCl conditions, from −8.31 to −8.58 kcal/mol. In 10 mM magnesium, all constructs gained nearly 1 kcal/mol (−9.31 to −9.58 kcal/mol) in stability, similar to 4-nt purine bulge loop constructs.

DNA constructs, 10 mM MgCl2

One- to 3-nt bulge loop DNA constructs showed similar stability in 10 mM magnesium and 1 M KCl. Four- and 5-nt bulge loops in DNA showed significant differences between adenine and guanine bulge loops. Four- and 5-nt guanine bulge loop constructs were additionally stabilized in 10 mM MgCl2 by −0.80 kcal/mol and −0.86 kcal/mol, respectively, over 1 M KCl (Table 2).

The loop parameters for DNA bulge loop were calculated as described for the RNA constructs (Table 4). The values utilized for the disrupted base pair stacking were those reported in 1 M salt (SantaLucia et al. 1996). The loop parameters in magnesium range from 4.16 kcal/mol for 1 nt to 5.59 kcal/mol for 5-nt bulge loops.

DISCUSSION

Bulge loops in RNA

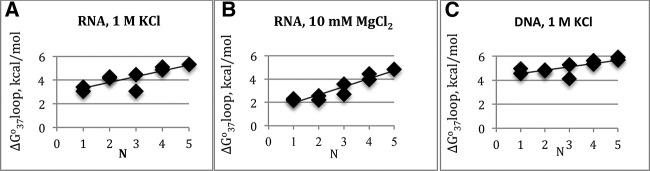

The presence of a bulge loop decreases the stability of RNA helix, with a larger energetic cost for a larger bulge loops in 1 M KCl, with the exception of trinucleotide guanine bulge loop. A linear correlation was seen between the bulge size and the loop (Fig. 3A) leading to the following prediction model:

| (3) |

(N = number of nucleotides in the bulge, with N values measured between 1 and 5).

FIGURE 3.

A plot of loop versus the number of nucleotides, N, in the bulge. Linear dependence is seen between the bulge loop size and the loop parameter. A plot of (A) RNA parameters in 1 M KCl; (B) RNA parameters in 10 mM MgCl2 RNA; (C) DNA parameters in 1 M KCl.

In the presence of 10 mM magnesium ions, a linear correlation was seen between the loop parameter and the number of bulge nucleotides (Fig. 3B) leading to the following prediction model in magnesium:

| (4) |

(N = the number of nucleotides in the bulge, with N values measured between 1 and 5).

The only previous work on various size bulge loops in RNA compared 1- to 3-nt adenine or uracil bulge loops in the context of 5′G–(Bulge)–G3′ or its complementary strand, 5′C–(Bulge)–C3′ in 1 M NaCl (Longfellow et al. 1990). Data for various size bulge loops are compared with the literature values below.

Single-nucleotide bulge loops

Single-base bulge loops have been extensively studied in DNA and RNA in 1 M NaCl (Tanaka et al. 2004; Blose et al. 2007; Minetti et al. 2010). Temperature-gradient gel electrophoresis has been performed on DNA and RNA single bulge loop constructs in one study where adenine and guanine 1-nt bulge loops had similar mobility for RNA and DNA constructs, implying similar structural conformations form in these constructs (Zhu and Wartell 1999). Zhu and Wartell assign loop parameter of 3.6 kcal/mol for adenine and guanine bulge loops inserted into 5′U–A3′/3′U–A5′ base pair relative to the helix. Our proposed model for 1-nt bulge loops gives a loop to be 3.5 kcal/mol. Three of the seven single-nucleotide bulge loops examined in the Longfellow et al. (1990) study show a similar value of 3.6 kcal/mol; averaging all seven constructs reported gives a parameter of 4.0 kcal/mol. All these values are within error of the predicted value using the model proposed here. The loop prediction using the current nearest-neighbor prediction models used by RNAstructure prediction program utilizes loop of 3.8 kcal/mol, similar to our proposed value. Single-nucleotide bulge loops were examined in multiple helical contexts by Blose et al. (2007) and showed nonnearest-neighbor interactions. A loop parameter of 3.9 kcal/mol was proposed for all single-nucleotide RNA bulge loops. Thus, within error, the prediction model proposed here for single-nucleotide bulge loops fits the general trends seen in the literature in one molar salt for RNA.

Dinucleotide bulge loops

The prediction model proposed here calculates of 4.0 kcal/mol for dinucleotide bulge loops in RNA. Longfellow et al. measured the values for adenine and uracil bulge loops. Longfellow et al.’s study had some hetro-duplexes that also formed homo-duplexes. When the RNA constructs that did not form homo-duplexes were utilized from the Longfellow et al. study, the parameter is 4.4 kcal/mol was obtained, which is within error of the proposed value. When all the dinucleotide bulge parameters are averaged, a value of 2.8 kcal/mol is obtained, which is the number currently utilized in the RNAstructure prediction program.

Trinucleotide bulge loops

Guanine and adenine trinucleotide bulge loops showed significant differences in stability in our study. The loop parameter was 4.46 kcal/mol for trinucleotide adenine bulge loops and 3.67 kcal/mol for trinucleotide guanine bulge loops. Trinucleotide bulge loops containing adenines were more stable than the corresponding dinucleotide bulge loops in the Longfellow et al. study. In a previous study, we had examined pyrimidine-rich trinucleotide bulge loop in HIV-1 TAR RNA, which gave a loop parameter of 5.94 kcal/mol for CCC and 7.17 kcal/mol for UCU bulge loop in 1 M KCl in 5′A–(Bulge)–G3′ helical context (Carter-O'Connell et al. 2008). We are further examining the helical constructs for the trinucleotide bulge loops, as base triple formation is implicated for HIV-1 TAR RNA (Puglisi et al. 1992; Huthoff et al. 2004). It is possible that structures formed by the trinucleotide bulge loops allow for additional interactions between the bulge nucleotides and the stem leading to a more complex thermodynamic profile. A recent study by Murray et al. (2014) assigns 4.2 kcal/mol for purine or 5.1 kcal/mole for pyrimidine trinucleotide bulge loops, with additional penalty per A–U closing base pair. Murray et al. study would predict loop parameter of 3.1 kcal/mol for our constructs. The specific helical contexts we have examined here were not examined in this study for a direct comparison of thermodynamic data. Our proposed model assigns 4.5 kcal/mol for the trinucleotide purine bulge loops in 1 M KCl. Murray et al.’s study also found that the pyrimidine bulge loops were energetically more expensive. A further examination of trinucleotide bulge loop is necessary to fully understand the deviation from the trends seen for other size bulge loops. Utilizing the measured values in Murray et al. or in this study will, however, improve the predictions over the existing prediction models.

Four- and 5-nt bulge loops

Our prediction model proposes a of 4.5 and 5.0 kcal/mol for 1 M KCl for a 4- and 5-nt bulge loop. The current RNAstructure prediction program utilizes a value of 3.6 and 4.0 kcal/mol for 4- and 5-nt bulge loops, both parameters are ∼1 kcal/mol lower than the prediction model proposed here.

Our results suggest that the parameters utilized in the current prediction models using free energy parameters underestimate the penalty for breaking the helical structure by bulge loops in one molar salt. In the absence of incorporating the loop parameters in magnesium ions, the current parameters utilized for RNA predictions lead to a decrease in the penalty for breaking the helix; hence, the current predictions model inadvertently lead to predictions that are closer to the values predicted here in the presence of magnesium ions. With more data being collected in the presence of magnesium ions, the effect of monovalent and divalent ions can be further delineated. RNA thermodynamic parameters obtained in the presence of magnesium ions will specifically improve the predictions for those motifs where RNA-magnesium interactions are significant as discussed below.

Magnesium effect on RNA bulge loops

Bulge loop constructs are expected to bend the RNA and hence, the negatively charged phosphates are expected to be in closer proximity. Interactions with positively charged ions are expected to neutralize the repulsion between nearby phosphate molecules. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to systematically measure the thermodynamic influence of magnesium ions on various size bulge loops in RNA and DNA constructs. We show that the interactions with 10 mM magnesium ions significantly alter the stability of RNA containing bulge loops by up to ∼2.0 kcal/mol (Table 3). It should be noted that experiments shown here were conducted only in two different helical contexts. In addition, the thermodynamic effects of magnesium ions are an aggregate of all favorable and unfavorable interactions and cannot be extrapolated to site-specific interactions at the bulge loop region. Our results show that for purine bulge loops in a 5′U–(Bulge)–U3′ helical context, the “average” change in stability (ΔΔG°) in 10 mM magnesium ions over 1 M KCl for 1 nt is −1.0 kcal/mol, for 2 nt is −1.8 kcal/mol, for 3 nt is −1.0 kcal/mol, 4 nt is −0.8 kcal/mol, and 5 nt is −0.7 kcal/mol (Table 3). The average value for “all” loop parameter for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops is −1.1 kcal/mol. Three-nucleotide pyrimidine bulge loop constructs showed an average change of −1.2 kcal/mol in magnesium ions over 1 M KCl (Carter-O'Connell et al. 2008). As the current models underestimate the penalty for breaking the helical structures for 4- and 5-nt bulge loops by ∼1 kcal/mol, the net result in prediction for these bulge loops will not be sufficiently different. However, for the single- and dinucleotide bulge loops, an additional difference in stability is seen in the presence of magnesium ions that is currently unaccounted for in the prediction models. Trinucleotide bulge loops should perhaps be treated as a special case and the measured parameters should be utilized where available. Improvements in RNA structure predictions are likely if significant magnesium effects are incorporated into the models.

Stability of DNA bulge loop constructs in 1 M salt

The plot of parameters for DNA bulge loop constructs shows a linear correlation with bulge loop size in 1 M salt conditions (Fig. 3C), with the exception of 3-nt guanine bulge loop. The following equation for predicting the loop parameter is proposed:

| (5) |

where N = number of nucleotides in the bulge, with N values measured between 1 and 5.

Single-nucleotide bulge loops have been studied in DNA (LeBlanc and Morden 1991; Zhu and Wartell 1999; Minetti et al. 2010) but the data on larger bulge loops have not been systematically collected. In the LeBlanc and Morden study, the adenine and guanine single-nucleotide bulge loops loop parameters were 4.6 and 4.4 kcal/mol in the 5′T–(Bulge)–T3′ helical context. The loop parameters for purine bulge loops are within error similar to our predicted values. Zhu and Wartell report loop parameter to be 3.3 kcal/mol for the same helical context. The current structure prediction model for DNA utilizes the values proposed by SantaLucia and Hicks (2004) for bulge loops. For single bulge nucleotide, the predicted value is 2 kcal/mol for 5′T–(Bulge)–T3′ helical context (with two A–T closing base pair). For dinucleotide bulge loops, loop parameter is 2.9 kcal/mol. A 0.1 kcal/mol increment is added for each 1 nt increase in bulge size. Our experimental data indicate that loop parameters are underestimated in current models for DNA structure prediction due to a lack of systematic experimental data on bulge loops.

Magnesium effect on DNA bulge loops

A comparison of thermodynamic data in 1 M KCl and 10 mM magnesium ions, 1- to 3-nt DNA bulge loop constructs did not show differences in stability for adenine and guanine bulge loops (Table 4). Guanine bulge loops showed increased magnesium effect for bulge loop of 4–5 nt; this effect needs to be examined further and could be due to interactions with specific stem nucleotides or specific ion interactions.

Although no systematic examination of bulge loops have been performed for DNA, effect of magnesium ions on small DNA constructs have been studied (Record 1975; Williams et al. 1989; Duguid et al. 1993; Owczarky et al. 2008). Under the ionic conditions examined here, no additional stabilization in 10 mM magnesium ions over 1 M KCl is expected based on the literature data.

Bulge loops in RNA versus DNA

DNA and RNA bulge loops show differences in thermodynamic parameters in both 1 M salt and in the presence of magnesium ions. In RNA, bulge loops are functionally relevant parts of the structures and are expected to form multiple conformers in solution. The ion interactions with various RNA conformations and their thermodynamic implications are unclear. In DNA, bulge loops are expected to form only due to defective processes and thus, should be efficiently repaired.

B-form DNA and A-form RNA helices exhibit different hydration, ion interaction and phosphate–phosphate distances, which lead to differences in measured thermodynamic parameters. The similarity and differences in nonhelical regions of RNA and DNA have not been examined systematically. The factors contributing to interactions with ions are unclear. We have previously shown differences in stability and ion interactions between RNA and DNA constructs in a 2 × 2 symmetrical internal loop constructs (Furniss and Grover 2011). We are further exploring the factors that contribute to the thermodynamic differences in various nonhelical structures in RNA and DNA.

CONCLUSIONS

RNA and DNA constructs containing purine-rich bulge loops decreased in stability as the size of the bulge loop increased in 1 M KCl, with a slightly greater penalty for breaking the DNA helices. One- and 2-nt bulge loops in RNA constructs gain additional stability in the presence of magnesium ions over 1 M KCl, thereby decreasing the energetic cost of the bulge loop, with the largest effect seen on dinucleotide bulge loops. We provide prediction models for 1- to 5-nt purine bulge loops in RNA and DNA in 1 M KCl, with additional predictions for RNA bulge loops in 10 mM magnesium ions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA constructs

All RNA constructs were ordered from Dharmacon, Inc. Sample purity was analyzed using mass spectrometry. Oligomers were purified using thin-layer chromatography using Baker Si500 silica plate 6:3:1 1-propanol, ammonium hydroxide, and water. Oligomers were extracted in water and spin filtered to remove any excess silica. Following drying on a SPD1010 SpeedVac System (Savant), the samples were deprotected with a buffer of 100 mM acetic acid adjusted to pH 3.8 with TEMED, provided by Dharmacon, Inc. The samples were loaded on a C18 Sep-Pak column (Waters: WAT020515) using 5 mM sodium bicarbonate buffer at a pH of 6. The samples were eluted in 2 mL of 30% acetonitrile (twice), with the final elution in 2 mL of 100% acetonitrile. The fractions containing the nucleic acid were dried, suspended in water and diluted in appropriate buffer for thermal denaturation experiments.

RNA constructs used in this study are shown in Figure 1. All RNA constructs were designed to yield one thermodynamically favored structure in solution using the nearest-neighbor model as utilized by the RNAstructure prediction program (Mathews et al. 2004). The presence of 3′-A overhang additionally stabilizes the RNA constructs and prevents the end base pairs from fraying (Freier et al. 1985). The helical contexts of the 4-nt bulge loop RNA examined were modeled after the A-rich bulge of P5abc region of the Group 1 intron from Tetrahymena thermophilia (Wu and Tinoco 1998). In order to obtain one thermodynamically favored structure in solution, a wild type A-rich bulge construct could not be generated, as it does not form the lowest stability structure in our construct design.

DNA constructs

All DNA constructs were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. DNA samples were purified in a manner similar to RNA constructs. DNA constructs were lengthened by one additional base pair on each stem to increase the construct stability.

Thermal denaturation experiments

All thermodynamic data were collected on a Cary 100 Bio UV-Visible Spectrophotometer, equipped with a 6 × 6 series II multicell peltier. The constructs were melted at the rate of 1°C/min between 0°C and 100°C. The change in absorbance was measured at the wavelength of 260 or 280 nm. All oligomers were melted as duplex in 1:1 concentration ratio using an average extinction coefficient. A concentration range of 10- to 50-fold was achieved by using a nine-step dilution scheme and by varying cuvette path length.

Buffers

The melt buffer was 10 mM cacodylic acid and 0.5 mM EDTA at pH 6.0. To this buffer, 10 mM magnesium chloride or 1 M KCl was added and the pH was adjusted to 6.0. The concentration of magnesium ions was established using complexometric titration and atomic absorption spectroscopy. RNA and DNA samples were melted in various additional concentrations (1 and 3 mM) of magnesium ions to ensure that the trend reported for 10 mM were valid (data provided in Supplemental Material). Each RNA construct was melted in a buffer containing 1 M KCl (containing no divalent metal ions) to measure the maximum stability of RNA under conditions where the negative charges on RNA are neutralized (Manning 1969; Record and Lohman 1978). The choice of potassium ions over sodium ions is based on the physiological relevance of potassium ions in the cells (Auffinger et al. 2011; Grover 2015). Three constructs were melted in 1 M NaCl buffer to determine any difference in stability between potassium and sodium buffers (Tables 1, 2). The results suggest that our data should be compatible with traditional 1 M NaCl experiments used in RNA structure predictions, as the constructs tested here did not show any additional stabilization in potassium ions over sodium ions.

Data analysis

Melting curves were analyzed in two ways: (1) by fitting individual melting curves using the two-state model using MeltWin 3.0, assuming linear sloping baselines and temperature independent ΔH° and ΔS° values (McDowell and Turner 1996); and (2) by plotting 1/Tm versus ln CT/4, as all the strands were nonself complementary. Thermodynamic parameters were obtained by van't Hoff analysis using the Equation 6 for noncomplementary duplexes:

| (6) |

where R is the gas constant and CT is the total strand concentration. The Gibbs free energy was calculated using Equation 7:

| (7) |

All data presented here fit the two-state model, with the difference between ΔH°, ΔS° values between the two models being <10% and those between ΔG° values being <5%. Figures showing representative melting curves and 1/Tm versus ln CT/4 plot are provided in the Supplemental Fig. S1. All further analyses utilized the values obtained using 1/Tm versus ln CT/4 analyses.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) MCB-0950582 grant to N.G. and via Venture Grants from Colorado College to the undergraduate student researchers. S.S. performed the RNA experiments on A- and G-rich constructs. Y.E.H. and E.S. contributed equally to the DNA project. We thank the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Colorado College for prioritizing and supporting undergraduate research.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.046631.114.

REFERENCES

- Auffinger P, Grover N, Westhof E. 2011. Metal ion binding to RNA. In Structural and catalytic roles of metal ions in RNA in metals in life sciences (ed. Sigel A, et al. ), pp. 1–35. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya A, Murchie AIH, Lilley DMJ. 1990. RNA bulges and the helical periodicity of double-stranded RNA. Nature 343: 484–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blose J, Manni M, Klapec K, Stranger-Jones Y, Zyra A, Sim V, Griffith C, Long J, Serra M. 2007. Non-nearest-neighbor dependence of the stability for RNA bulge loops based on the complete set of group I single-nucleotide bulge loops. Biochemistry 46: 15123–15135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-O'Connell I, Booth D, Eason B, Grover N. 2008. Thermodynamic examination of trinucleotide bulged RNA in the context of HIV-1 TAR RNA. RNA 14: 2550–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate J, Hanna R, Doudna J. 1997. A magnesium ion core at the heart of a ribozyme domain. Nat Struct Biol 4: 553–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevec M, Thibaudeau C, Plavec J. 2010. NMR structure of the let-7 miRNA interacting with the site LCS1 of lin-41 mRNA from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 7814–7821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CC, Freeborn B, Moore PB, Steitz TA. 1997. Metals, motifs, and recognition in the crystal structure of a 5S rRNA domain. Cell 91: 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty E, Doudna J. 2001. Ribozyme structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 30: 457–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguid J, Bloomfield VA, Benevides J, Thomas GJ Jr. 1993. Raman spectroscopy of DNA-metal complexes. I. Interactions and conformational effects of the divalent cations: Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Pd, and Cd. Biophys J 65: 1916–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freier S, Alkema D, Sinclair A, Neilson T, Turner DH. 1985. Contribution of dangling end stacking and terminal base-pair formation to the stabilities of XGGCCp, XCCGGp, XGGCCYp, and XCCGGYp helices. Biochemistry 24: 4533–4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furniss S, Grover N. 2011. Thermodynamic examination of the pyrophosphate sensor helix in the thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitch. RNA 17: 710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke C, Murchie AIH, Lilley DMJ, Clegg R. 1994. Kinking of DNA and RNA helices by bulged nucleotides observed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 11660–11664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott J, Wilhelm L, Uhlenbeck O. 1991. RNA binding properties of the coat protein from bacteriophage GA. Nucleic Acids Res 19: 6499–6503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover N. 2015. On using magnesium and potassium ions in RNA experiments, Chapter 14. In Regulatory non-coding RNAs (ed. Carmichael G). Humana Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke LA, Nallagatla SR, Hull CM, Bevilacqua PC. 2011. RNA helical imperfections regulate activation of the protein kinase PKR: effects of bulge position, size, and geometry. RNA 17: 957–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann T, Patel D. 2000. RNA bulges as architectural and recognition motifs. Structure 15: R47–R54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huthoff H, Girard F, Wijmenga SS, Berkout B. 2004. Evidence for a base-triple in the free HIV-1 TAR RNA. RNA 10: 412–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger JA, Turner DH, Zuker M. 1989. Improved predictions of secondary structures for RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 7706–7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. 1990. Misalignment-mediated DNA synthesis errors. Biochemistry 29: 8003–8011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc DA, Morden K. 1991. Thermodynamic characterization of deoxyribooligonucleotide duplex containing bulges. Biochemistry 30: 4042–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longfellow CE, Kierzek R, Turner DH. 1990. Thermodynamic and spectroscopic study of bulge loops in oligoribonucleotides. Biochemistry 29: 278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning GS. 1969. Limiting laws and counterion condensation in polyelectrolyte solutions I. Colligative properties. J Chem Phys 51: 924–933. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Disney MD, Childs JL, Schroeder SJ, Zuker M, Turner DH. 2004. Incorporating chemical modification constraints into a dynamic programming algorithm for prediction of RNA secondary structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 7287–7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell J, Turner DH. 1996. Investigation of the structural basis for thermodynamic stabilities of tandem GU mismatches: solution structure of (rGAGGUCUC)2 by two-dimentional NMR and simulated annealing. Biochemistry 35: 14077–14089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetti CSA, Remeta DP, Dickstein R, Breslauer KJ. 2010. Energetic signatures of single base bulges: thermodynamic consequences and biological implications. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 97–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MH, Hard JA, Zonsko BM. 2014. Improved model to predict the free energy contribution of trinucleotide bulges to RNA duplex stability. Biochemistry 53: 3502–3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owczarky R, Moreira BG, Youg Y, Behlke MA, Walder JA. 2008. Predicting stability of DNA duplexes in solutions containing magnesium and monovalent cations. Biochemistry 47: 5336–5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peattie DA, Douthwatte S, Garrett R, Noller H. 1981. A “bulged” double helix in a RNA–protein contact site. Proc Natl Acad Sci 12: 7331–7335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi JD, Tan R, Calnan BJ, Frankel AD, Williamson JR. 1992. Conformation of the TAR RNA-arginine complex by NMR spectroscopy. Science 257: 76–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Record MT. 1975. Effects of Na+ and Mg2+ ions on the helix-coil transition of DNA. Biopolymers 14: 2137–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Record MT, Lohman T. 1978. A semiempirical extension of polyelectrolyte theory to the treatment of oligoelectrolytes: application to oligonucleotide helix-coil transitions. Biopolymers 17: 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- SantaLucia J, Hicks D. 2004. The thermodynamics of DNA structural motifs. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 33: 415–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SantaLucia J, Allawi HT, Seneviratne PA. 1996. Improved nearest neighbor parameters for predicting DNA duplex stability. Biochemistry 35: 3555–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Beauchamp KA, Harbury PB, Herschlag D. 2014. From a structural average to the conformational ensemble of a DNA bulge. Proc Natl Acad Sci 111: E1473–E1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streisinger G, Owen J. 1985. Mechanism of spontaneous and induced frameshift mutation in bacteriophage. Genetics 109: 633–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka F, Kameda A, Yamamoto M, Ohuchi A. 2004. Thermodynamic parameters based on a nearest-neighbor model for DNA sequences with a single-bulge loop. Biochemistry 43: 7143–7150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DH. 1992. Bulges in nucleic acids. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2: 334–337. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AP, Longfellow CE, Freier SM, Kierzek R, Turner DH. 1989. Laser temperature-jump, spectroscopic, and thermodynamic study of salt effects on duplex formation by dGCATGC. Biochemistry 28: 4283–4291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR, Guttell RR. 1989. Evidence for several higher order structural elements in ribosomal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 3119–3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Tinoco IJ. 1998. RNA folding causes secondary structure rearrangement. Proc Natl Acad Sci 95: 11555–11560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H-N, Uhlenbeck OC. 1987. Role of a bulged a residue in a specific RNA protein interaction. Biochemistry 26: 8221–8227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia TB, SantaLucia J, Bruckard ME, Kierzek R, Schroeder SJ, Zuker M, Turner DH. 1998. Thermodynamic parameters for an expanded nearest-neighbor model for the formation of RNA duplexes with Watson–Crick base pairs. Biochemistry 37: 14719–14735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias M, Hagerman PJ. 1995a. The bend in RNA created by the trans-activation response element bulge of human immunodeficiency virus is straightened by arginine and by Tat-derived peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92: 6052–6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharias M, Hagerman PJ. 1995b. Bulge-induced bends in RNA: quantification by transient electric birefringence. J Mol Biol 247: 486–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Sun X, Watt ED, Al-Hashimi HM. 2006. Resolving the motional modes that code for RNA adaptation. Science 311: 653–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Kim N-K, Peterson RD, Wang Z, Feigon J. 2010. Structually conserved five nucleotide bulge determines the overall topology of the core domain of human telemerase RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107: 18761–18768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Wartell RM. 1999. The effect of base sequence on the stability of RNA and DNA single base bulges. Biochemistry 38: 15986–15993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.