Abstract

Numerous versions of human papillomavirus (HPV) therapeutic vaccines designed to treat individuals with established HPV infection, including those with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), are in development because approved prophylactic vaccines are not effective once HPV infection is established. As human papillomavirus 16 (HPV-16) is the most commonly detected type worldwide, all versions of HPV therapeutic vaccines contain HPV-16, and some also contain HPV-18. While these two HPV types are responsible for approximately 70% of cervical cancer cases, there are other high-risk HPV types known to cause malignancy. Therefore, it would be of interest to assess whether these HPV therapeutic vaccines may confer cross-protection against other high-risk HPV types. Data available from a few clinical trials that enrolled subjects with CINs regardless of the HPV type(s) present demonstrated clinical responses, as measured by CIN regression, in subjects with both vaccine-matched and nonvaccine HPV types. The currently available evidence demonstrating cross-reactivity, epitope spreading, and de novo immune stimulation as possible mechanisms of cross-protection conferred by investigational HPV therapeutic vaccines is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is best known as the causative agent of cervical cancer, the fourth most common cancer among women globally. This is the case despite advances in screening techniques and the availability of approved prophylactic vaccines. Every year in the United States, there are 12,360 new cases of cervical cancer and 4,020 deaths (1). High-risk HPV types associated with the development of malignancies have been linked to 90 to 93% of anal cancers, 12 to 63% of oropharyngeal cancers, 36 to 40% of penile cancers, 40 to 64% of vaginal cancers, and 40 to 51% of vulvar cancers (2). Overall, HPV is estimated to be responsible for 5.2% of the worldwide cancer burden (3). Of note, the incidence of HPV-associated anal and oropharyngeal cancers is increasing in the United States (4).

The designation of papillomaviruses as the family Papillomaviridae was created in the seventh report of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses (5). The papillomaviruses were further divided into genera by assigning Greek letters and into species by Roman numerals (6). For example, HPV-16, -31, -33, -35, -52, -58, and -67 belong to genus alpha, species 9 (α9) (6). The circular double-stranded-DNA genomes of papillomaviruses are approximately 8 kb in size and commonly encode 8 proteins (6). The L1 gene encodes a major capsid protein, while the L2 gene encodes a minor capsid protein. A more traditional designation of HPV types was based on the nucleotide sequence of the L1 gene. A designation of a new type was created whenever a full-length papillomavirus clone was described which was at least 10% dissimilar from any other known papillomavirus type (6).

Currently, three effective HPV prophylactic vaccines are commercially available, all of which contain HPV L1 proteins that are capable of forming viruslike particles (VLPs). Gardasil (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA), a quadrivalent HPV VLP prophylactic vaccine containing the L1 proteins of HPV-16, -18, -6, and -11, was the first to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in 2006. Cervarix (GalaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium), a bivalent version containing the L1 proteins of HPV-16 and -18, was approved 3 years later in the United States. Gardasil 9 (Merck), which includes L1 VLPs from HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -52, -59, -6, and -11, was approved by the FDA in late 2014. Gardasil and Cervarix were designed to prevent 70% of cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer cases caused by HPV-16 and -18, while Gardasil 9 was designed to prevent approximately 90% of such cases. HPV types associated with the development of malignancy are regarded as high risk. On the other hand, HPV-6 and -11, which are included in Gardasil and Gardasil 9, are considered low risk and are associated with the development of genital warts. While Gardasil and Gardasil 9 include aluminum-containing adjuvant (amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate), Cervarix uses AS04, which is made of 3-O-desacyl-4′-monophosphoryl lipid A adsorbed onto aluminum as hydroxide salt. These three vaccines are called prophylactic vaccines, as they are designed to prevent HPV infection from occurring. In contrast, HPV therapeutic vaccines for individuals who have already acquired HPV are in development, and none are currently available on the market.

A common belief has been that HPV vaccines, both prophylactic and therapeutic, confer mostly HPV type-specific protection. However, some level of cross-protection against nonvaccine HPV types has been demonstrated for the prophylactic vaccines Gardasil and Cervarix (7–14). In the phase III randomized, double-blinded clinical trial examining the efficacy of Cervarix, Paavonen et al. observed vaccine efficacy not only against cervical intraepithelial neoplasias of grade 2 and worse (CIN2+) associated with HPV-16 and -18 but also against CIN2+ associated with HPV-31, -33, and -45 (11). In the study examining the effect of Gardasil on oncogenic nonvaccine HPV types, significant reduction of CIN2+ associated with 10 nonvaccine high-risk HPV types (HPV-31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, and -59), most notably HPV-31, was observed (7). It is generally accepted that the bivalent prophylactic vaccine confers additional protection against HPV-31, -33, and -45, while the quadrivalent vaccine protects against HPV-31 (14). Furthermore, cross-neutralizing antibodies against HPV-31 and -45 have been demonstrated in vaccine recipients (15).

In order to gain insights into the mechanisms of cross-protection against nonvaccine HPV types, two groups studied serum samples from vaccine recipients using different approaches in vitro (16, 17). Serum samples from Cervarix recipients were incubated with HPV-16 or HPV-18 VLPs prior to a VLP-based multiplex immunoassay for antibodies against HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -45, -52, and -58 L1 VLPs. The vaccine-derived antibodies were type specific and cross-reacted to a lesser degree with other HPV types within the species. For example, serum incubated with HPV-16 VLPs showed decreased antibody concentrations binding to HPV-16, -31, -33, -52, and -58 (α9 species) but not HPV-18. On the other hand, serum incubated with HPV-18 VLPs showed decreased antibody concentrations binding to HPV-18 and -45 (α7 species) but not HPV-16, -31, -33, -52, and -58 (17). Bissett and colleagues used L1 VLPs of nonvaccine HPV types (HPV-31, -33, -35, or -58) coupled to magnetic Sepharose beads to isolate antibodies from serum samples from Cervarix recipients (16). These purified antibodies were then tested for their ability to neutralize L1L2 pseudoviruses. The neutralization titers of HPV-16 L1L2 pseudoviruses, nonvaccine-HPV-type L1L2 pseudoviruses used for isolation, and other nonvaccine-HPV-type L1L2 pseudoviruses were compared. The titer against HPV-16 was greatly reduced after antibody depletion with nonvaccine VLPs. Increased neutralization of L1L2 pseudoviruses of nonvaccine HPV types not used for antibody isolation was not observed. The data appear to support the notion that cross-neutralization is due to a small fraction of antibodies exhibiting different but overlapping specificities rather than weak cross-recognition of nonvaccine types by vaccine-type-HPV-specific antibodies (16). Both of these studies examined a small number of subjects, and further work is needed to clarify exactly how prophylactic vaccines confer cross-protection. However, it is safe to conclude that some types of cross-reactivity are responsible for the observed cross-protection. The most recently FDA-approved HPV prophylactic vaccine, Gardasil 9, contains all the HPV types for which cross-protection by Gardasil and Cervarix has been shown. Therefore, further investigation in this area would be of academic interest.

Many clinical trials testing putative HPV therapeutic vaccines have selectively vaccinated subjects known to be positive for HPV-16 DNA (18–27) or for HPV-16 and/or -18 DNA (28–30). However, in some clinical trials, subjects with cervical intraepithelial lesions of grade 2 or 3 (CIN2/3) were enrolled regardless of the HPV type(s) detected (31–33). Therefore, cross-protection against nonvaccine HPV types could be assessed in these studies. An example is our phase I clinical trial of an HPV-16 E6 peptide-based HPV therapeutic vaccine (PepCan), which used a Candida skin test reagent (Candin; Nielsen Biosciences, San Diego, CA) as a novel vaccine adjuvant (33). Forty-four percent (4 of 9) of subjects with HPV-16 at entry and 57% (8 of 14) of subjects with nonvaccine HPV types showed histological regression. Nieminen and colleagues reported a regression rate of 20% (11 of 56) in vaccine (modified Vaccinia Ankara with modified HPV-16 E6 and E7 and human interleukin 2) recipients with HPV-16 monoinfection at entry, while the regression rate of all vaccine recipients was 31% (40 of 129) (32). In recipients of ZYC101a [plasmid DNA encoding regions of HPV-16 and -18 E6 and E7 proteins, encapsulated in biodegradable poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles] who were less than 25 years old, the regression rate was 64% in those with HPV-16 or -18 at entry, 73% in subjects with other HPV types, and 23% in the placebo group (31). These data suggest that the cross-protection for CIN2/3 associated with nonvaccine HPV types is at least equal to that of CIN2/3 associated with vaccine HPV types. An obvious possible mechanism of cross-protection is cross-reactivity of T cells induced by the vaccines. Alternative possible mechanisms are epitope spreading and de novo immune stimulation.

CROSS-REACTIVITY

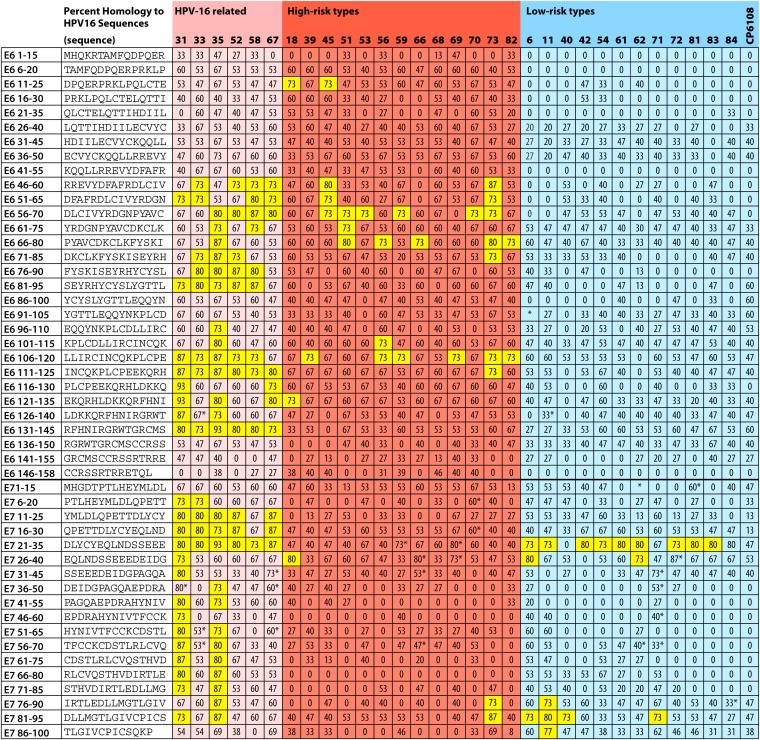

Cross-protection and cross-reactivity of HPV prophylactic vaccine-induced antibodies have been demonstrated for HPV types closely phylogenetically related to the vaccine HPV types. Likewise, cross-reactivity of T cells induced by HPV therapeutic vaccines is expected to target epitopes of HPV types with high amino acid sequence homology. In Fig. 1, the amino acid sequences of HPV-16 E6 and E7 proteins (Papillomavirus Episteme, http://pave.niaid.nih.gov/#home), divided into overlapping 15-mer peptides, are compared (NCBI BLAST, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) with those of other high-risk and low-risk HPV types (34). Based on homology, peptides containing potentially cross-reactive T-cell epitopes are found most frequently in HPV-16-related types and to a lesser extent in other high-risk HPV types. In low-risk HPV types, such potentially cross-reactive peptides are only present in the E7 protein, not the E6 protein. Whether or not high amino acid homology results in cross-recognition has been addressed for a select number of T-cell epitopes described within the HPV-16 E6 and E7 proteins. Tables 1 and 2 list CD4 and CD8 HPV-16 T-cell epitopes described to date to our knowledge for which the amino acid sequences and the restricting HLA molecules have been identified. The homologous peptides used to study each of the marked epitopes in Tables 1 and 2 are listed in Tables 3 to 7.

FIG 1.

Amino acid sequence homologies between peptides (15 amino acids in length) of HPV-16 and other HPV types. The peptides with ≥70% homology are highlighted in yellow. *, amino acid insertion(s) is present.

TABLE 1.

CD4 T-cell epitopes of HPV-16 E6 and E7 proteins described, with HLA restriction elements identified

| Epitope (length) | Sequence | HLA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| E6 11–32 (22) | DPQERPRKLPQLCTELQTTIHD | DP17 | 59 |

| E6 11–32 (22) | DPQERPRKLPQLCTELQTTIHD | DP1401 | 59 |

| E6 37–68 (32) | CVYCKQQLLRREVYDFAFRDLCIVYRDGNPYA | DP0201 | 59 |

| E6 52–62 (11)a | FAFRDLCIVYR | DR11 | 38 |

| E6 52–61 (10) | FAFRDLCIVY | DP0201 | 59 |

| E6 61–82 (22) | YRDGNPYAVCDKCLKFYSKISE | DP0101 | 59 |

| E6 61–82 (22) | YRDGNPYAVCDKCLKFYSKISE | DP1401 | 59 |

| E6 71–92 (22) | DKCLKFYSKISEYRHYCYSLYG | DP0101 | 59 |

| E6 73–105 (33) | CLKFYSKISEYRHYCYSLYGTTLEQQYNKPLCD | DP0401 | 59 |

| E6 74–83 (10)b | LKFYSKISEY | DP | 39 |

| E6 91–112 (22) | YGTTLEQQYNKPLCDLLIRCIN | DR15 or DQ05 | 59 |

| E6 101–122 (22) | KPLCDLLIRCINCQKPLCPEEK | DQ06 | 59 |

| E6 121–142 (22) | EKQRHLDKKQRFHNIRGRWTGR | DP0201 or DQ05 | 59 |

| E6 127–141 (15) | DKKQRFHNIRGRWTG | DR01 | 60 |

| E6 129–138 (10) | KQRFHNIRGR | DR7 | 59 |

| E7 21–42 (22) | DLYCYEQLNDSSEEEDEIDGPA | DR4 | 59 |

| E7 35–50 (16) | EDEIDGPAGQAEPDRA | DQ2 | 61 |

| E7 43–77 (35) | GQAEPDRAHYNIVTFCCKCDSTLRLCVQSTHVDIR | DR3 | 61 |

| E7 50–62 (13) | AHYNIVTFCCKCD | DR15 | 61 |

| E7 51–72 (22) | HYNIVTFCCKCDSTLRLCVQST | DP1901 | 59 |

| E7 58–68 (11) | CCKCDSTLRLC | DR17 | 62 |

| E7 61–80 (20) | CDSTLRLCVQSTHVDIRTLE | DR0901 | 63 |

| E7 71–85 (15) | STHVDIRTLEDLLMG | DQ0201 | 64 |

| E7 76–86 (11) | IRTLEDLLMGT | DR12 | 59 |

TABLE 2.

CD8 T-cell epitopes of HPV-16 E6 and E7 proteins described, with HLA restriction elements identified

| Epitope (length) | Sequence | HLA | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E6 13–22 (10) | QERPRKLPQL | B7 | 59 |

| E6 29–37 (9) | TIHDIILEC | B48 | 65 |

| E6 29–38 (10) | TIHDIILECV | A02, A0201 | 59, 65, 66 |

| E6 31–38 (8) | HDIILECV | B4002 | 65 |

| E6 52–61 (10)a | FAFRDLCIVY | B57 | 35, 59, 67 |

| E6 52–61 (10) | FAFRDLCIVY | B35 | 65 |

| E6 52–61 (10)b | FAFRDLCIVY | B58 | 36 |

| E6 75–83 (9)c | KFYSKISEY | B62 | 37 |

| E6 80–88 (9) | ISEYRHYCY | B18 | 68 |

| E6 133–142 (10)d | HNIRGRWTGR | A6801 | 37 |

| E6 137–146 (10) | GRWTGRCMSC | B27 | 59 |

| E6 149–158 (10) | SSRTRRETQL | B14 | 59 |

| E7 7–15 (9) | TLHEYMLDL | B8 | 69 |

| E7 7–15 (9) | TLHEYMLDL | B48 | 67 |

| E7 11–19 (9) | YMLDLQPET | A02, A0201 | 59, 70 |

| E7 11–20 (10) | YMLDLQPETT | A0201 | 66 |

| E7 44–52 (9) | QAEPDRAHY | B18 | 68 |

| E7 61–69 (9) | CDSTLRLCV | A2402 | 71 |

| E7 67–76 (10) | LCVQSTHVDI | A2402 | 71 |

| E7 79–87 (9) | LEDLLMGTL | B60 | 67 |

| E7 82–90 (9) | LLMGTLGIV | A0201 | 66 |

| E7 86–93 (8) | TLGIVCPI | A0201 | 66 |

Cross-reactivity to homologous sequences from other HPV types has been tested and demonstrated (Table 4).

Cross-reactivity to homologous sequences from other HPV types has been tested and demonstrated (Table 5).

Cross-reactivity to homologous sequences from other HPV types has been tested but not demonstrated (Table 6).

Cross-reactivity to homologous sequences from other HPV types has been tested but not demonstrated (Table 7).

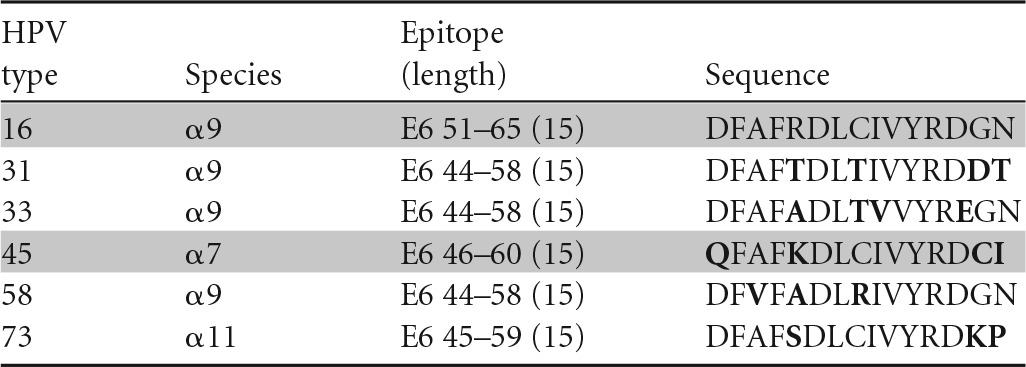

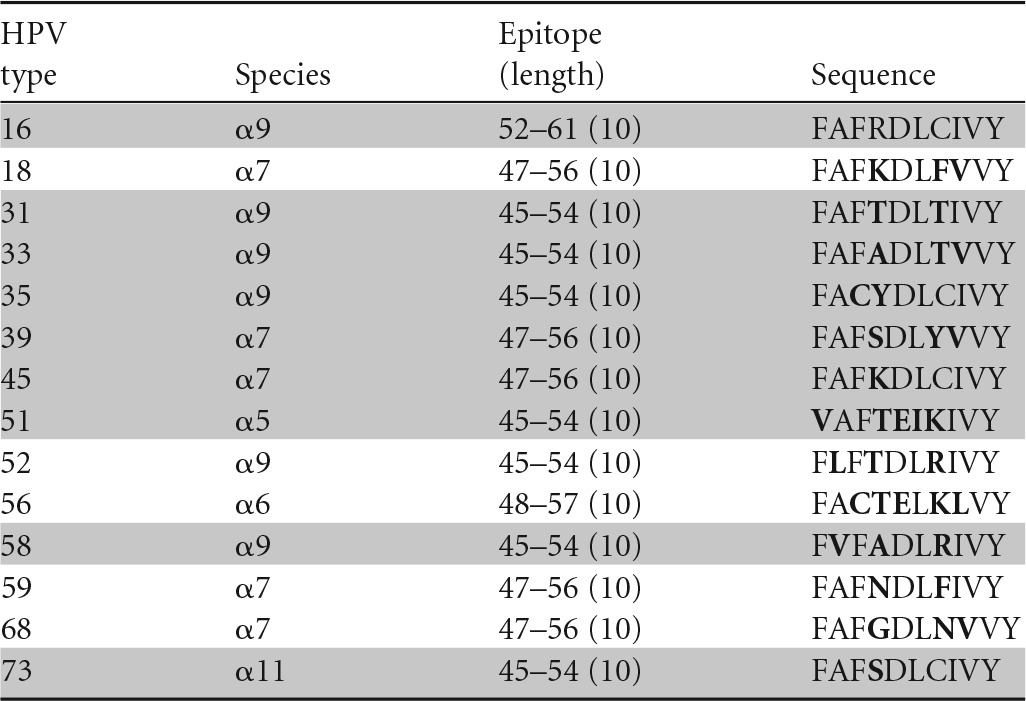

TABLE 3.

Peptides from high-risk HPV types homologous to HPV-16 E6 aa-51-to-65 epitope for assessment of cross-reactive CD4 epitopesa

Amino acids different from those of HPV-16 are shown in bold, and peptides recognized in ELISPOTs are highlighted in gray.

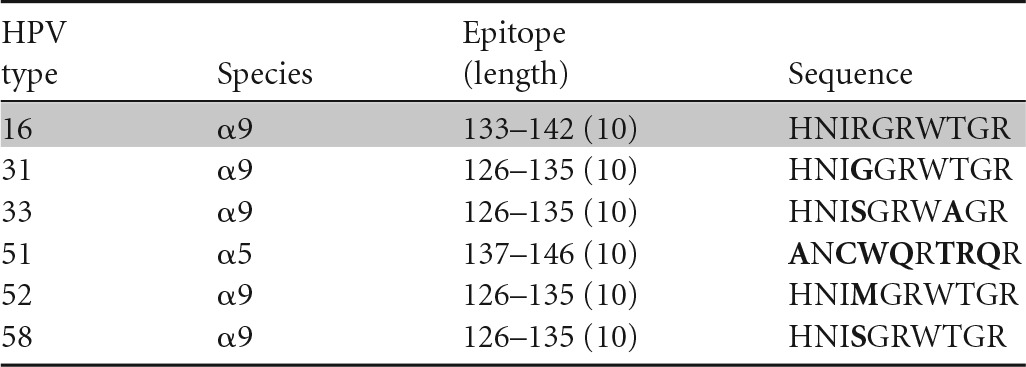

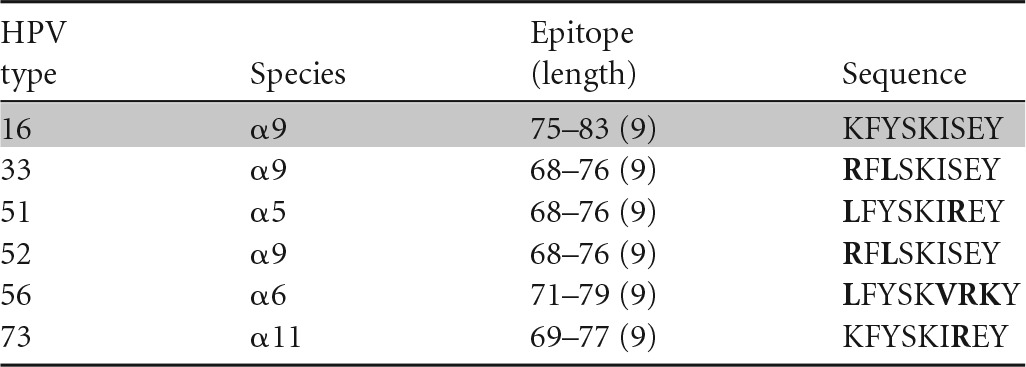

TABLE 7.

Peptides from high-risk HPV types homologous to HPV-16 E6 aa-133-to-142 (HLA A6801 restricted) epitope for assessment of cross-reactive CD8 epitopesa

Amino acids different from those in HPV-16 are shown in bold, and peptides recognized in ELISPOTs are highlighted in gray.

Our group approached this question by isolating T-cell clones positive for an HPV-16 epitope and examining the recognition of homologous sequences from other high-risk HPV types using a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISPOT) (35–37). If the number of spot-forming units for a homologous sequence from another HPV type was equal to or greater than 50% of the number for HPV-16, then that HPV type was considered to be cross-reactive. Using this criterion, an example in which an HPV-16 E6 aa-52-to-62-epitope-specific CD4 T-cell clone was cross-reacting with a homologous peptide from HPV-45 has been shown (Table 3) (38). Other homologous peptides (≥70% amino acid homology) from HPV-31, -33, -58, and -73 were not recognized. Therefore, cross-recognition with HPV-45, which belongs to the α7 species (HPV-18 related), was observed, while cross-recognition with other α9 species (HPV-16-related types HPV-31, -33, and -58) was not.

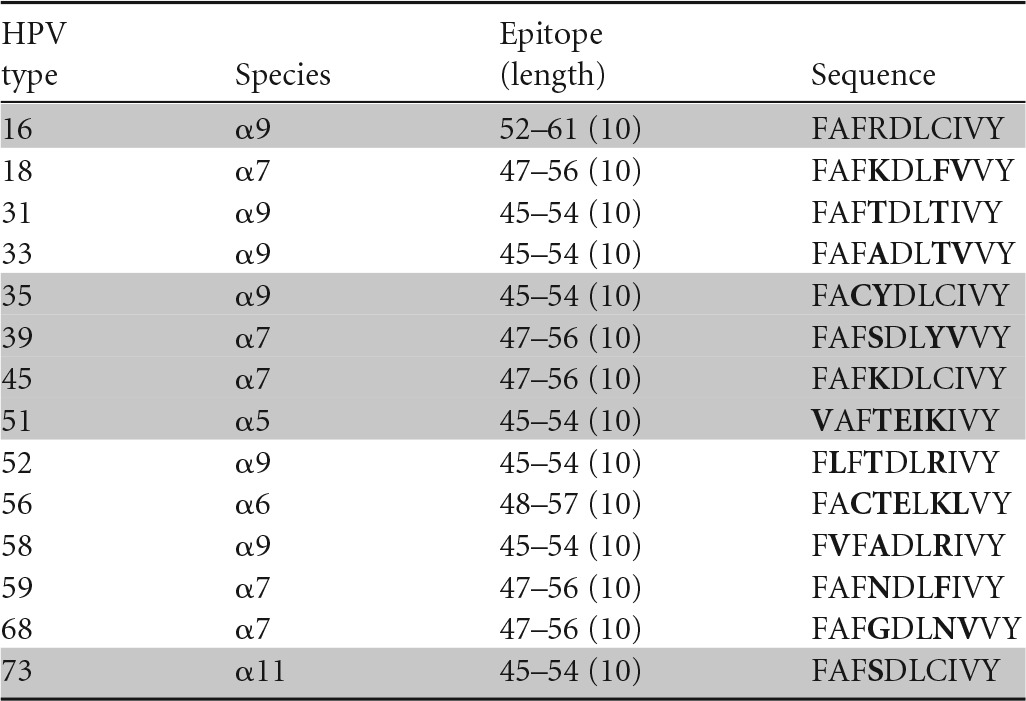

A similar conclusion can be drawn regarding cross-recognition of homologous CD8 HPV T-cell epitopes. A CD8 T-cell clone specific for the HPV-16 E6 aa-52-to-61 epitope restricted by the HLA class I B57 molecule has been shown to cross-recognize HPV-35 (α9), -39 (α7), -45 (α7), -51 (α5), and -73 (α11) (35) (Table 4), while another CD8 T-cell clone specific for the same peptide but restricted by another HLA class I molecule, B58, has been shown to cross-recognize HPV-31 (α9), -33 (α9), -35 (α9), -39 (α7), -45 (α7), -51 (α5), -58 (α9), and -73 (α11) (36) (Table 5). On the other hand, a CD8 T-cell clone recognizing the HPV-16 E6 aa-75-to-83 epitope restricted by the HLA class I B62 molecule (Table 6) and another clone recognizing the E6 aa-133-to-142 epitope restricted by the HLA class I A6801 molecule (Table 7) did not recognize any homologous peptides tested (37). Therefore, the presence of amino acid homology does not automatically lead to cross-recognition and it is not species specific when present. Whether or not such cross-recognition is present in natural infection is not known, since the generation of homologous epitopes from native protein by endogenous antigen processing has not been investigated. On the other hand, the possibility of cross-recognition can be ruled out in the absence of peptide recognition.

TABLE 4.

Peptides from high-risk HPV types homologous to HPV-16 E6 aa-52-to-61 (HLA B57 restricted) epitope for assessment of cross-reactive CD8 epitopesa

Amino acids different from those in HPV 16 are shown in bold, and peptides recognized in ELISPOTs are highlighted in gray.

TABLE 5.

Peptides from high-risk HPV types homologous to HPV 16 E6 aa-52-to-61 (HLA B58 restricted) epitope for assessment of cross-reactive CD8 epitopesa

Amino acids different from those in HPV-16 are shown in bold, and peptides recognized in ELISPOTs are highlighted in gray.

TABLE 6.

Peptides from high-risk HPV types homologous to HPV-16 E6 aa-75-to-83 (HLA B62 restricted) epitope for assessment of cross-reactive CD8 epitopesa

Amino acids different from those in HPV-16 are shown in bold, and peptides recognized in ELISPOTs are highlighted in gray.

Another group has taken the investigation of cross-recognition of HPV-16 CD4 T-cell epitopes one step further. van den Hende and colleagues investigated the cross-recognition of five closely related members of the α9 species (HPV-31, -33, -35, -52, and -58) (39). Using overlapping peptides, approximately half of the responding subjects displayed recognition of more than two other HPV types, suggesting that cross-recognition may be relatively common. However, further investigation using enriched and clonal T-cell populations and naturally processed epitopes derived from whole proteins demonstrated only one example of an HPV-16-specific CD4 T-cell clone capable of cross-recognizing homologous peptides of other HPV types (Table 1). Therefore, they concluded that the HPV-16 E6-specific CD4 T-cell responses are unlikely to cross-recognize and so unlikely to cross-protect against other highly related HPV types. Overall, cross-recognition can be demonstrated, but rarely. Thus, cross-recognition is unlikely to be the main mechanism of cross-protection seen in the recipients of HPV therapeutic vaccines.

EPITOPE SPREADING

Epitope spreading is a process in which antigenic epitopes distinct from and non-cross-reactive with an inducing epitope become additional targets of an ongoing immune response (40). It can be beneficial to the host by resulting in protection from other pathogens, or it can be harmful to the host in the setting of autoimmunity (41). In our phase I clinical trial of a peptide-based HPV therapeutic vaccine, statistically significant increases in CD3 T-cell responses to HPV-16 E7 protein, which was not included in the vaccine, were demonstrated in two vaccine recipients (33). Both subjects also had significantly increased responses to the E6 protein, which is included in the vaccine. One subject had HPV-16 DNA detected before and after vaccination, while the other subject had HPV-45 detected prior to and after vaccination. These may be the first examples of epitope spreading in recipients of an HPV therapeutic vaccine (33). For the subject with HPV-45, cross-recognition would be unlikely, as the HPV-45 E7 aa-1-to-15 region only has 33% amino acid homology with the HPV-16 sequences of the same region (Fig. 1). The presence of latent HPV-16 infection no longer detectable with the current method of HPV detection may be more likely. Epitope spreading has been shown to correlate with tumor regression in peptide-based cancer immunotherapy (42–47) and may be quite beneficial in enhancing the therapeutic effects of the treatment. Therefore, future investigations to uncover additional evidence of epitope spreading and to elucidate underlying mechanisms should be pursued.

DE NOVO IMMUNE STIMULATION

The idea of using Candida skin testing reagent as a novel vaccine adjuvant came about from observations that intralesional injections of recall antigens result in common wart regression (48–54). Traditionally, recall antigens, which typically include a panel derived from Candida, mumps virus, and Trichophyton, were used as a control to indicate intact cell-mediated immunity in patients being tested for tuberculosis by placing purified protein derivative (PPD; an extract of Mycobacterium tuberculosis); T-cell-mediated inflammation would emerge within 24 to 48 h (55). Many studies have shown that recall antigens were effective not only in regressing injected warts, but also in regressing untreated distant warts (48–52, 54). These studies suggested that T cells may have a role in wart regression. In a recently completed phase I investigational new drug study in which the largest wart was treated with Candin, our group reported complete resolution of the treated warts in 82% (9 of 11) of the subjects and complete resolution of distant untreated warts in 75% (6 of 8) of the subjects (52). Furthermore, T-cell responses to the HPV-57 L1 peptide were detected in 67% (6 of 9) of the complete responders. Therefore, intralesional injection of Candida may have resulted in de novo generation of anti-HPV T-cell responses. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that Candida has a proliferative effect on T-cells and that the cytokine most frequently produced by Langerhans cells exposed to Candida was interleukin 12, which promotes T-cell response (56, 57). Intriguingly, injecting the wart, which is the site of active infection, may not be necessary to induce T-cell responses, as one group reported that weekly intradermal injections of PPD in the forearms was effective in treating anogenital warts in pregnant women (58).

Additional evidence of de novo immune stimulation was demonstrated in our clinical trial of the HPV therapeutic vaccine mentioned above (33). HPV-DNA testing was performed prior to vaccination and 20 weeks after initiation of vaccination. The rate of HPV clearance was higher for low-risk HPV types (62%) than for HPV-16 (33%), HPV-16-related types (33%), and other high-risk types (25%) (Table 8), although the vaccine only contained HPV-16 E6 peptides. Since there is no amino acid sequence homology equal to or greater than 70% between the E6 protein of HPV-16 and the E6 proteins of low-risk HPV types (Fig. 1), de novo immune stimulation is likely responsible for the low-risk HPV types becoming undetectable. One should keep in mind that the subjects' own immunity may account for some degree of HPV clearance. Nevertheless, it is possible that our HPV therapeutic vaccine, which consists of HPV-16 E6 peptides and Candida skin test reagent, may work through a nonspecific immune stimulatory effect of the Candida skin test reagent in addition to the HPV-specific effects induced by the HPV-16 E6 peptides (33).

TABLE 8.

Defining cross-protection by HPV clearance

| HPV type(s) | No. (%) of subjects (n = 23) who had indicated HPV type(s): |

|

|---|---|---|

| Prior to vaccination | Cleared | |

| 16 | 9 | 3 (33) |

| 16 relateda | 15 | 5 (33) |

| Non-16-related high riskb | 16 | 4 (25) |

| Low riskc | 13 | 8 (62) |

HPV-16-related HPV types include HPV-31, -33, -35, -52, and -58.

Other high-risk HPV types include HPV-39, -45, -51, -53, -56, -59, -66, -73, and -82.

Low-risk HPV types include HPV-6, -61, -62, -72, -81, -83, -84, and -CP6108.

The three potential mechanisms discussed here, cross-recognition, epitope spreading, and de novo immune stimulation, need not be mutually exclusive. Further investigation of the mechanisms of cross-protection conferred by HPV therapeutic vaccines should yield interesting findings, and they may be quite different from the mechanisms of cross-protection conferred by the HPV prophylactic vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01CA143130 and UL1TR000039.

M.N. is one of the inventors named in patents and patent applications describing an HPV therapeutic vaccine named PepCan.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. 2014. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi AK. 2010. Beyond cervical cancer: burden of other HPV-related cancers among men and women. J Adolesc Health 46(Suppl):S20–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tota JE, Chevarie-Davis M, Richardson LA, Devries M, Franco EL. 2011. Epidemiology and burden of HPV infection and related diseases: implications for prevention strategies. Prev Med 53(Suppl 1):S12–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, Eheman C, Saraiya M, Bandi P, Saslow D, Cronin KA, Watson M, Schiffman M, Henley SJ, Schymura MJ, Anderson RN, Yankey D, Edwards BK. 2013. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst 105:175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Regenmortel MHV, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Calisher CH, Carsten EB, Estes MK, Lemon SM, Maniloff J, Mayo MA, McGeoch DJ, Pringle CR, Wickner RB. 2002. Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard HU, Burk RD, Chen Z, van Doorslaer K, zur Hausen H, de Villiers EM. 2010. Classification of papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virology 401:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown DR, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen OE, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, Garcia P, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Steben M, Bosch FX, Dillner J, Joura EA, Kurman RJ, Majewski S, Munoz N, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, Bryan J, Lupinacci LC, Giacoletti KE, Sings HL, James M, Hesley TM, Barr E. 2009. The impact of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV; types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine on infection and disease due to oncogenic nonvaccine HPV types in generally HPV-naive women aged 16-26 years. J Infect Dis 199:926–935. doi: 10.1086/597307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler CM, Moscicki AB, Romanowski B, Roteli-Martins CM, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Costa Clemens SA, Dubin G. 2006. Sustained efficacy up to 4.5 years of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine against human papillomavirus types 16 and 18: follow-up from a randomised control trial. Lancet 367:1247–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68439-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kavanagh K, Pollock KG, Potts A, Love J, Cuschieri K, Cubie H, Robertson C, Donaghy M. 2014. Introduction and sustained high coverage of the HPV bivalent vaccine leads to a reduction in prevalence of HPV-16/18 and closely related HPV types. Br J Cancer 110:2804–2811. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malagon T, Drolet M, Boily MC, Franco EL, Jit M, Brisson J, Brisson M. 2012. Cross-protective efficacy of two human papillomavirus vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 12:781–789. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Hedrick J, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Garland S, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, Bosch FX, Jenkins D, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Lehtinen M, Dubin G. 2009. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet 374:301–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler CM, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen OE, Hernandez-Avila M, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, Garcia P, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Steben M, Bosch FX, Dillner J, Joura EA, Kurman RJ, Majewski S, Munoz N, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, Bryan J, Lupinacci LC, Giacoletti KE, James M, Vuocolo S, Hesley TM, Barr E. 2009. The impact of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV; types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine on infection and disease due to oncogenic nonvaccine HPV types in sexually active women aged 16-26 years. J Infect Dis 199:936–944. doi: 10.1086/597309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szarewski A. 2007. Prophylactic HPV vaccines. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 28:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westra TA, Stirbu-Wagner I, Dorsman S, Tutuhatunewa ED, de Vrij EL, Nijman HW, Daemen T, Wilschut JC, Postma MJ. 2013. Inclusion of the benefits of enhanced cross-protection against cervical cancer and prevention of genital warts in the cost-effectiveness analysis of human papillomavirus vaccination in the Netherlands. BMC Infect Dis 13:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draper E, Bissett SL, Howell-Jones R, Edwards D, Munslow G, Soldan K, Beddows S. 2011. Neutralization of non-vaccine human papillomavirus pseudoviruses from the A7 and A9 species groups by bivalent HPV vaccine sera. Vaccine 29:8585–8590. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bissett SL, Draper E, Myers RE, Godi A, Beddows S. 2014. Cross-neutralizing antibodies elicited by the Cervarix(R) human papillomavirus vaccine display a range of alpha-9 inter-type specificities. Vaccine 32:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherpenisse M, Schepp RM, Mollers M, Meijer CJ, Berbers GA, van der Klis FR. 2013. Characteristics of HPV-specific antibody responses induced by infection and vaccination: cross-reactivity, neutralizing activity, avidity and IgG subclasses. PLoS One 8:e74797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borysiewicz LK, Fiander A, Nimako M, Man S, Wilkinson GW, Westmoreland D, Evans AS, Adams M, Stacey SN, Boursnell ME, Rutherford E, Hickling JK, Inglis SC. 1996. A recombinant vaccinia virus encoding human papillomavirus types 16 and 18, E6 and E7 proteins as immunotherapy for cervical cancer. Lancet 347:1523–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brun JL, Dalstein V, Leveque J, Mathevet P, Raulic P, Baldauf JJ, Scholl S, Huynh B, Douvier S, Riethmuller D, Clavel C, Birembaut P, Calenda V, Baudin M, Bory JP. 2011. Regression of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with TG4001 targeted immunotherapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 204:169.e1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daayana S, Elkord E, Winters U, Pawlita M, Roden R, Stern PL, Kitchener HC. 2010. Phase II trial of imiquimod and HPV therapeutic vaccination in patients with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Cancer 102:1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson EJ, Faulkner RL, Sehr P, Pawlita M, Smyth LJ, Burt DJ, Tomlinson AE, Hickling J, Kitchener HC, Stern PL. 2004. Effect of TA-CIN (HPV 16 L2E6E7) booster immunisation in vulval intraepithelial neoplasia patients previously vaccinated with TA-HPV (vaccinia virus encoding HPV 16/18 E6E7). Vaccine 22:2722–2729. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frazer IH, Quinn M, Nicklin JL, Tan J, Perrin LC, Ng P, O'Connor VM, White O, Wendt N, Martin J, Crowley JM, Edwards SJ, McKenzie AW, Mitchell SV, Maher DW, Pearse MJ, Basser RL. 2004. Phase 1 study of HPV16-specific immunotherapy with E6E7 fusion protein and ISCOMATRIX adjuvant in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Vaccine 23:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenter GG, Welters MJ, Valentijn AR, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, Vloon AP, Essahsah F, Fathers LM, Offringa R, Drijfhout JW, Wafelman AR, Oostendorp J, Fleuren GJ, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ. 2009. Vaccination against HPV-16 oncoproteins for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med 361:1838–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klencke B, Matijevic M, Urban RG, Lathey JL, Hedley ML, Berry M, Thatcher J, Weinberg V, Wilson J, Darragh T, Jay N, Da Costa M, Palefsky JM. 2002. Encapsulated plasmid DNA treatment for human papillomavirus 16-associated anal dysplasia: a phase I study of ZYC101. Clin Cancer Res 8:1028–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muderspach L, Wilczynski S, Roman L, Bade L, Felix J, Small LA, Kast WM, Fascio G, Marty V, Weber J. 2000. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus (HPV) peptide vaccine for women with high-grade cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia who are HPV 16 positive. Clin Cancer Res 6:3406–3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheets EE, Urban RG, Crum CP, Hedley ML, Politch JA, Gold MA, Muderspach LI, Cole GA, Crowley-Nowick PA. 2003. Immunotherapy of human cervical high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with microparticle-delivered human papillomavirus 16 E7 plasmid DNA. Am J Obstet Gynecol 188:916–926. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trimble CL, Peng S, Kos F, Gravitt P, Viscidi R, Sugar E, Pardoll D, Wu TC. 2009. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus DNA vaccine for HPV16+ cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3. Clin Cancer Res 15:361–367. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Hernandez E, Gonzalez-Sanchez JL, Andrade-Manzano A, Contreras ML, Padilla S, Guzman CC, Jimenez R, Reyes L, Morosoli G, Verde ML, Rosales R. 2006. Regression of papilloma high-grade lesions (CIN 2 and CIN 3) is stimulated by therapeutic vaccination with MVA E2 recombinant vaccine. Cancer Gene Ther 13:592–597. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santin AD, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Bossini B, Roman JJ, Cannon MJ, Bignotti E, Cane S, Pecorelli S. 2003. Induction of tumor-specific cytotoxicity in tumor infiltrating lymphocytes by HPV16 and HPV18 E7-pulsed autologous dendritic cells in patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol 89:271–280. doi: 10.1016/S0090-8258(03)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santin AD, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Zanolini A, Ravaggi A, Siegel ER, Roman JJ, Pecorelli S, Cannon MJ. 2008. Human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 E7-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination of stage IB or IIA cervical cancer patients: a phase I escalating-dose trial. J Virol 82:1968–1979. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02343-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia F, Petry KU, Muderspach L, Gold MA, Braly P, Crum CP, Magill M, Silverman M, Urban RG, Hedley ML, Beach KJ. 2004. ZYC101a for treatment of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 103:317–326. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000110246.93627.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieminen P, Harper DM, Einstein MH, Garcia F, Donders G, Huh W, Wright TC, Stoler M, Ferenczy A, Rutman O, Shikhman A, Leung M, Clinch B, Calleja E. 2012. Efficacy and safety of RO5217990 treatment in patients with high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3), p 206 28th Int Papillomavirus Conf Abstr Book Clin Sci. 28th IPV Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 30 November to 6 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenfield WW, Stratton S, Myrick R, Vaughn R, Donnalley L, Coleman H, Mercado M, Moerman-Herzog A, Spencer H, Andrews-Collins N, Hitt W, Low G, Manning N, McKelvey S, Smith D, Smith M, Phillips A, Quick C, Jeffus S, Hutcins L, Nakagawa M. A phase I dose-escalation clinical trial of a peptide-based human papillomavirus therapeutic vaccine with Candida skin test reagent as a novel vaccine adjuvant for treating women with biopsy-proven cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3. Oncoimmunology, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. 2004. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim KH, Dishongh R, Santin AD, Cannon MJ, Bellone S, Nakagawa M. 2006. Recognition of a cervical cancer derived tumor cell line by a human papillomavirus type 16 E6 52-61-specific CD8 T cell clone. Cancer Immun 6:9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Greenfield WW, Coleman HN, James LE, Nakagawa M. 2012. Use of interferon-gamma enzyme-linked immunospot assay to characterize novel T-cell epitopes of human papillomavirus. J Vis Exp 2012:3657. doi: 10.3791/3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Moscicki AB, Tsang L, Brockman A, Nakagawa M. 2008. Memory T cells specific for novel human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E6 epitopes in women whose HPV16 infection has become undetectable. Clin Vaccine Immunol 15:937–945. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00404-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman HA, Wang X, Greenfield WW, Nakagawa M. 2014. A human papillomavirus type 16 E6 52-62 CD4 T-cell epitope restricted by the HLA-DR11 molecule described in an epitope hotspot. MOJ Immunology 1:00018. doi: 10.15406/moji.2014.01.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Hende M, Redeker A, Kwappenberg KM, Franken KL, Drijfhout JW, Oostendorp J, Valentijn AR, Fathers LM, Welters MJ, Melief CJ, Kenter GG, van der Burg SH, Offringa R. 2010. Evaluation of immunological cross-reactivity between clade A9 high-risk human papillomavirus types on the basis of E6-specific CD4+ memory T cell responses. J Infect Dis 202:1200–1211. doi: 10.1086/656367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ribas A, Timmerman JM, Butterfield LH, Economou JS. 2003. Determinant spreading and tumor responses after peptide-based cancer immunotherapy. Trends Immunol 24:58–61. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)00029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Getts DR, Chastain EM, Terry RL, Miller SD. 2013. Virus infection, antiviral immunity, and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev 255:197–209. doi: 10.1111/imr.12091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brossart P, Wirths S, Stuhler G, Reichardt VL, Kanz L, Brugger W. 2000. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vivo after vaccinations with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. Blood 96:3102–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, Amarnani SN, Vu HT, Oseguera D, Wang HJ, Elashoff RM, McBride WH, Mukherji B, Cochran AJ, Glaspy JA, Economou JS. 2003. Determinant spreading associated with clinical response in dendritic cell-based immunotherapy for malignant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 9:998–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jonuleit H, Giesecke-Tuettenberg A, Tuting T, Thurner-Schuler B, Stuge TB, Paragnik L, Kandemir A, Lee PP, Schuler G, Knop J, Enk AH. 2001. A comparison of two types of dendritic cell as adjuvants for the induction of melanoma-specific T-cell responses in humans following intranodal injection. Int J Cancer 93:243–251. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lally KM, Mocellin S, Ohnmacht GA, Nielsen MB, Bettinotti M, Panelli MC, Monsurro V, Marincola FM. 2001. Unmasking cryptic epitopes after loss of immunodominant tumor antigen expression through epitope spreading. Int J Cancer 93:841–847. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ranieri E, Kierstead LS, Zarour H, Kirkwood JM, Lotze MT, Whiteside T, Storkus WJ. 2000. Dendritic cell/peptide cancer vaccines: clinical responsiveness and epitope spreading. Immunol Invest 29:121–125. doi: 10.3109/08820130009062294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inderberg-Suso EM, Trachsel S, Lislerud K, Rasmussen AM, Gaudernack G. 2012. Widespread CD4+ T-cell reactivity to novel hTERT epitopes following vaccination of cancer patients with a single hTERT peptide GV1001. Oncoimmunology 1:670–686. doi: 10.4161/onci.20426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clifton MM, Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Kincannon J, Horn TD. 2003. Immunotherapy for recalcitrant warts in children using intralesional mumps or Candida antigens. Pediatr Dermatol 20:268–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horn TD, Johnson SM, Helm RM, Roberson PK. 2005. Intralesional immunotherapy of warts with mumps, Candida, and Trichophyton skin test antigens: a single-blinded, randomized, and controlled trial. Arch Dermatol 141:589–594. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson SM, Horn TD. 2004. Intralesional immunotherapy for warts using a combination of skin test antigens: a safe and effective therapy. J Drugs Dermatol 3:263–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Horn TD. 2001. Intralesional injection of mumps or Candida skin test antigens: a novel immunotherapy for warts. Arch Dermatol 137:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim KH, Horn TD, Pharis J, Kincannon J, Jones R, O'Bryan K, Myers J, Nakagawa M. 2010. Phase 1 clinical trial of intralesional injection of Candida antigen for the treatment of warts. Arch Dermatol 146:1431–1433. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maronn M, Salm C, Lyon V, Galbraith S. 2008. One-year experience with candida antigen immunotherapy for warts and molluscum. Pediatr Dermatol 25:189–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips RC, Ruhl TS, Pfenninger JL, Garber MR. 2000. Treatment of warts with Candida antigen injection. Arch Dermatol 136:1274–1275. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esch RE, Buckley CE III. 1988. A novel Candida albicans skin test antigen: efficacy and safety in man. J Biol Stand 16:33–43. doi: 10.1016/0092-1157(88)90027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nakagawa M, Coleman HN, Wang X, Daniels J, Sikes J, Nagarajan UM. 2014. IL-12 secretion by Langerhans cells stimulated with Candida skin test reagent is mediated by dectin-1 in some healthy individuals. Cytokine 65:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X, Coleman HN, Nagarajan U, Spencer HJ, Nakagawa M. 2013. Candida skin test reagent as a novel adjuvant for a human papillomavirus peptide-based therapeutic vaccine. Vaccine 31:5806–5813. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eassa BI, Abou-Bakr AA, El-Khalawany MA. 2011. Intradermal injection of PPD as a novel approach of immunotherapy in anogenital warts in pregnant women. Dermatol Ther 24:137–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piersma SJ, Welters MJ, van der Hulst JM, Kloth JN, Kwappenberg KM, Trimbos BJ, Melief CJ, Hellebrekers BW, Fleuren GJ, Kenter GG, Offringa R, van der Burg SH. 2008. Human papilloma virus specific T cells infiltrating cervical cancer and draining lymph nodes show remarkably frequent use of HLA-DQ and -DP as a restriction element. Int J Cancer 122:486–494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallagher KM, Man S. 2007. Identification of HLA-DR1- and HLA-DR15-restricted human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) and HPV18 E6 epitopes recognized by CD4+ T cells from healthy young women. J Gen Virol 88:1470–1478. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Burg SH, Ressing ME, Kwappenberg KM, de Jong A, Straathof K, de Jong J, Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, Franken KL, Ottenhoff TH, Fleuren GJ, Kenter G, Melief CJ, Offringa R. 2001. Natural T-helper immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E7-derived peptide epitopes in patients with HPV16-positive cervical lesions: identification of 3 human leukocyte antigen class II-restricted epitopes. Int J Cancer 91:612–618. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, Santin AD, Bellone S, Gupta S, Nakagawa M. 2009. A novel CD4 T-cell epitope described from one of the cervical cancer patients vaccinated with HPV 16 or 18 E7-pulsed dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 58:301–308. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0525-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okubo M, Saito M, Inoku H, Hirata R, Yanagisawa M, Takeda S, Kinoshita K, Maeda H. 2004. Analysis of HLA-DRB1*0901-binding HPV-16 E7 helper T cell epitope. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 30:120–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2003.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peng S, Trimble C, Wu L, Pardoll D, Roden R, Hung CF, Wu TC. 2007. HLA-DQB1*02-restricted HPV-16 E7 peptide-specific CD4+ T-cell immune responses correlate with regression of HPV-16-associated high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Clin Cancer Res 13:2479–2487. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Gillam TM, Moscicki AB. 2007. HLA class I binding promiscuity of the CD8 T-cell epitopes of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein. J Virol 81:1412–1423. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ressing ME, Sette A, Brandt RM, Ruppert J, Wentworth PA, Hartman M, Oseroff C, Grey HM, Melief CJ, Kast WM. 1995. Human CTL epitopes encoded by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 identified through in vivo and in vitro immunogenicity studies of HLA-A*0201-binding peptides. J Immunol 154:5934–5943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Moscicki AB. 2004. Different methods of identifying new antigenic epitopes of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 proteins. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11:889–896. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.5.889-896.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bourgault Villada I, Beneton N, Bony C, Connan F, Monsonego J, Bianchi A, Saiag P, Levy JP, Guillet JG, Choppin J. 2000. Identification in humans of HPV-16 E6 and E7 protein epitopes recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes in association with HLA-B18 and determination of the HLA-B18-specific binding motif. Eur J Immunol 30:2281–2289. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oerke S, Hohn H, Zehbe I, Pilch H, Schicketanz KH, Hitzler WE, Neukirch C, Freitag K, Maeurer MJ. 2005. Naturally processed and HLA-B8-presented HPV16 E7 epitope recognized by T cells from patients with cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 114:766–778. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keskin DB, Reinhold B, Lee SY, Zhang G, Lank S, O'Connor DH, Berkowitz RS, Brusic V, Kim SJ, Reinherz EL. 2011. Direct identification of an HPV-16 tumor antigen from cervical cancer biopsy specimens. Front Immunol 2:75. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jang S, Kim YT, Chung HW, Lee KR, Lim JB, Lee K. 2012. Identification of novel immunogenic human leukocyte antigen-A 2402-binding epitopes of human papillomavirus type 16 E7 for immunotherapy against human cervical cancer. Cancer 118:2173–2183. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]